Archive for the 'Movie theatres' Category

Side by side by side: Quick catchups

David Lynch in the documentary Side by Side.

DB here:

Some developments related to recent posts we’ve done!

On digital cinema: Cineaste magazine has published a wide-ranging “Critical Symposium on the Changing Face of Motion Picture Exhibition” in its most recent issue. It gathers in-depth reflections from Grover Crisp, the Ferroni Brigade, Scott Foundas, Bruce Goldstein, Haden Guest, Ned Hinkle, J. Hoberman, James Quandt, D. N. Rodowick, and Jonathan Rosenbaum. I add some comments too. A preview is here, but the responses are available only in the print edition. That edition also includes two signature Cineaste interviews, this time with Kirby Dick and Eyal Sivan, along with another symposium of great interest, devoted to film editors’ response to the rise of digital postproduction. As regular readers know, the series I composed on digital projection, Pandora’s Digital Box, has been revised and turned into an e-book.

On digital cinema: Cineaste magazine has published a wide-ranging “Critical Symposium on the Changing Face of Motion Picture Exhibition” in its most recent issue. It gathers in-depth reflections from Grover Crisp, the Ferroni Brigade, Scott Foundas, Bruce Goldstein, Haden Guest, Ned Hinkle, J. Hoberman, James Quandt, D. N. Rodowick, and Jonathan Rosenbaum. I add some comments too. A preview is here, but the responses are available only in the print edition. That edition also includes two signature Cineaste interviews, this time with Kirby Dick and Eyal Sivan, along with another symposium of great interest, devoted to film editors’ response to the rise of digital postproduction. As regular readers know, the series I composed on digital projection, Pandora’s Digital Box, has been revised and turned into an e-book.

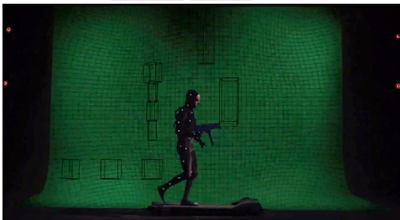

As for digital production, that’s the center of the new documentary film by Christopher Kinneally called Side by Side. It has played several festivals and is now available on Pay Per View via Tribeca. I think it’s a balanced, lucid introduction to the pros and cons of shooting digitally, as well as a helpful historical overview of the development of cameras and capture systems. It includes interviews with Scorsese, Lynch, Cameron, Fincher, and many other directors, along with a wide selection of editors and cinematographers. (DP Geoff Boyle adds some especially salty comments.) Side by Side is especially strong on post-production; how often do you get comments from Digital Colorists? There’s a little bit about exhibition too. Keanu Reeves makes a well-informed and unobtrusive interviewer. In all, the film would be a very good teaching tool in introductory courses. Kinneally discusses the project at Filmmaker.

I was a little surprised by the popularity of my entry on Cinerama, written in response to Flicker Alley’s magnificent release of This Is Cinerama on Blu-ray. Now there’s a podcast by David Strohmaier, the moving force behind reviving interest in the format. See The Commentary Track. Speaking of Cinerama, Kristin and I enjoyed our visit to Seattle’s Cinerama Theatre, where we saw The Master in 70mm. The theatre has been magnificently restored to its 1960s glory, Populuxe decor and all. Occasionally three-panel Cinerama films are screened there. And I should mention that while I was yearning from afar, the Cinerama Dome in Los Angeles held a festival earlier in the fall.

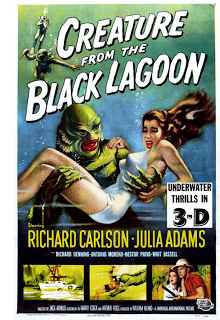

LIke Cinerama, classic 3-D holds perennial fascination, especially for baby boomers like me. I was lucky enough to see the digital restoration of the stereoscopic version of Dial M for Murder at the Toronto International Film Festival, and I wrote about it here. Bob Furmanek, expert in the format, provided an in-depth discussion of it on his site, 3-D Film Archive. Now Bob and Greg Kintz have added an equally intense backgrounder on The Creature from the Black Lagoon. As Bob writes to me: “Only 48 more Golden Age titles to go!”

LIke Cinerama, classic 3-D holds perennial fascination, especially for baby boomers like me. I was lucky enough to see the digital restoration of the stereoscopic version of Dial M for Murder at the Toronto International Film Festival, and I wrote about it here. Bob Furmanek, expert in the format, provided an in-depth discussion of it on his site, 3-D Film Archive. Now Bob and Greg Kintz have added an equally intense backgrounder on The Creature from the Black Lagoon. As Bob writes to me: “Only 48 more Golden Age titles to go!”

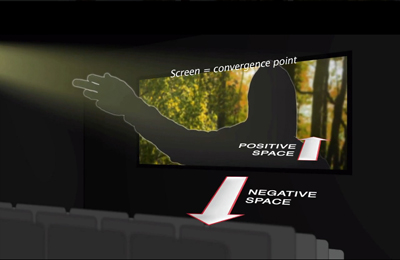

Now that Dial M is available in a 3-D Blu-ray disc, I think it’s worth mentioning that this is something of a milestone for film analysis. When I was first studying 3-D in the early 1980s, it was almost impossible to see vintage films in the format. Although archives held copies, those were typically flat versions. Even if the archive had both the A and B films, they would have been very difficult to screen. Worse, it would have been impossible to study 3-D shooting using the major tool at my disposal, the 35mm flatbed viewer. Now, viewers with 3-D TVs and 3-D players, can study Dial M and Creature shot by shot, even freezing frames to examine exactly how the shots are designed. This isn’t usually mentioned as a benefit of the new technology, but digital restoration and displays let us examine movies in 3-D in unprecedented detail.

In July I reviewed the local fracas over our old picture palace, the Orpheum. Things were quiet over the summer, but now it’s all up for grabs again. The promised foreclosure is in the offing, followed by interim management from the team that handles Lollapalooza and Austin City Limits. The Wisconsin State Journal‘s Steve Elbow brings us the news here and here.

Finally, the video essay on constructive editing in our previous entry has attracted some compliments, for which we’re grateful. Its discussion of the Kuleshov effect has led some to ask us whether the several videos on YouTube are authentic footage of Kuleshov’s experiments. Alas, they are not, but Kristin and I don’t know their provenance. However, in Oksana Bulgakowa’s documentary on the Kuleshov effect, available on YouTube, there are some fragments of the surviving footage, starting at 4:28. Oksana has also helped complete the experiment by inserting a substitute for a missing shot. In addition, I’m reminded by Joe McBride and Katharine Spring of Hitchcock’s famous explanation of the Kuleshov effect, available on the DVD, A Talk with Hitchcock. An excerpt from that is posted on YouTube, probably illegally.

P.S. 11 November 2012: Jay Rath of Isthmus presents another, more optimistic account of the past and future of the Orpheum.

Inside Seattle’s Cinerama Theatre.

Digital projection, there and here

Galeries Cinéma banner, Brussels, 2012.

DB here:

The Cinéma Arenberg, in the splendid Galerie de la Reine, has long been a mainstay of Brussels film culture. Since 1939, the lovely Art Deco theatre was what we Americans call an art-house. Over the years Kristin and I visited the city, the Arenberg’s autumn and spring schedules featured recent releases, but every summer the programmers plunged into plucky repertory programs. While the multiplexes ran Hollywood blockbusters, the Arenberg provided 90 or so classics and little-known releases under the rubric of Écran Total. It was here, for example, that I saw von Trier’s The Kingdom and resaw Vanishing Point. Four years ago I left a little note about the three titles I watched during my last day in town: India Song, Serpico, and Darjeeling Limited. That trio gives you a sense of how varied and interesting the programming was.

The Arenberg closed down at the end of 2011, but the cinema has reopened under new management as Galeries Cinéma. It didn’t sponsor an Écran Total season this year. Instead it offered brand-new releases on its three screens, along with some children’s programs.

Most notable for me this time was Leos Carax’s Holy Motors. Whatever you’ve heard about this film is probably accurate. I found it an exhilarating, frustrating, and continuously provocative descent into Surrealist role-playing. It’s a tour of cinema genres and an anthology of bits of other movies, from Marey to Franju, and not forgetting Carax’s own. Especially evocative were the poetic fusions, such as the way that the body stocking Oscar dons for digital motion-capture evokes both ninja outfits and the leotards of Feuillade’s Vampires. Carax films Oscar’s SPFX exercise in a way that connects Muybridge to video games and recalls the exuberantly spasmodic scene in Mauvais Sang in which Denis Lavant races madly down the street to the accompaniment of David Bowie’s “Modern Love.”

Whether you find Holy Motors infuriating or beguiling, you won’t forget it.

Exquisitely shot on digital capture, Carax’s film was given crisp, bright digital projection at the Galeries. And speaking of digital projection. . . .

The new issue of Film History, devoted to digital technology’s impact on filmmaking and film culture, includes Lisa Dombrowski’s article “Not If, But When and How: Digital Comes to the American Art House.” It’s a very fine survey of all the issues facing the art-film community at this moment. Lisa reviews the major technological and financing conditions before going into depth on a case study of three art theatres in Miami. The author of a very good book on Samuel Fuller, Lisa knows how to tie together industrial and aesthetic issues skilfully.

Another young scholar, this one at the Free University of Brussels, has concentrated on the digital transition in Europe. Since 2005 Sophie De Vinck has been studying how the conversion of theatres fits into European film policy. The result was her 2011 thesis, “Revolutionary Road? Looking back at the position of the European film sector and the results of European-level film support in view of their digital future.” The thesis, running to a whopping 769 pages, is an immense resource, and not just for people interested in digital cinema. Sophie surveys the history of national and international support of the Western European film industry, from production through exhibition, and she provides both a broad context and very specific analysis.

Part of her argument is that the “diversity” aimed at by subsidized filmmaking hasn’t been matched by diversity in audiences. But digitization offers a new chance to show films outside the dominant forms of commercial cinema and perhaps attracted new sectors of the public. “Every innovation usually brings with it possibilities for new or smaller sector players to strengthen their competitive position.” Her examination of how digital conversion affects small and art-house venues provides a complement to Lisa’s research.

I wish I’d known about Sophie’s thesis when I was writing the blogs that became Pandora’s Digital Box, but at least I can signal her work now. Best news of all: Sophie has generously made “Revolutionary Road?” available under a Creative Commons license here as a pdf. Full of valuable statistics and well-honed observations, her work helps us understand how the contemporary European film industry has survived and sometimes flourished over the last fifty years.

Cinema Arenberg, Brussels, 2008. The original design of the curved doorway and neon sign was restored in 2005-2006.

The indispensable site Cinema Treasures has a brief entry on the history of the Cinéma Arenberg/ Galeries. More extensive information can be found in Isabel Biver’s luxurious survey, Cinémas de Bruxelles: Portraits et destins, which I wrote about in an earlier entry.

P.S. 1 August 2012: I just learned from Gabrielle Claes that Giovanna Fossati’s book on digital restoration in film archives, From Grain to Pixel, is now available for free in pdf form here. It’s well worth reading.

Orpheum descending

State Street, Madison, Wisconsin, 1927.

DB:

When it comes to film culture, Wisconsin yields to no one in weird-assery. I’ve chronicled Mad City Movie Mania on other occasions (here and here), and a current flap has just added to the annals of the addled.

It revolves around Madison’s Orpheum Theatre, a 1927 movie palace that has gone through many incarnations. In recent years it’s become mainly a music venue, but it was also fitted out with a restaurant and still showed the occasional art movie. Until it was shut down last month.

The problem is that after several years of confusion, feuding, moving money around, petty spite, and general dodginess, nobody knows exactly who owns the Orpheum. Is the owner Henry Doane, local restauranteur, who for years was publicly considered the purchaser? Is it Eric Fleming, Doane partner who became anything but silent? Is it Gus Paras, wealthy landlord and restauranteur, who bid a couple of million for it at auction last month? What of the woman who acquired Fleming’s share of the building? And the shadowy figure who made off with a plastic bag holding $175,000—how does he fit in?

“I’ve never done anything to deserve the negative treatment that I’ve been getting. I’m very compromising. I’m willing to do whatever it takes to make things work—as long as it’s profitable.” Eric Fleming

“I’ve gone through every kind of humiliation known to mankind, so I’m kind of immune to it at this point.” By 2007 the partnership had gone so sour that Doane keyed Fleming’s car in broad daylight.

Please visit the story by Steven Elbow at the Capital Times for all the details. My account will be drawing on Elbow’s patient sleuthing, but I also want to recall the glorious, not to mention the inglorious, days of this old house.

Marbles

Orpheum Theatre, 1927. Photo by Angus B. McVicar. Collection, Wisconsin Historical Society.

Designed by Rapp and Rapp, premiere theatre architects, the New Orpheum opened in 1927. (It was initially called that because it superseded the Orpheum, a vaudeville house in another part of town, which was soon renamed the Garrick and specialized in live theatre.) The New Orpheum’s lavish French Renaissance foyer swept up to a staircase leading to the balcony. The auditorium held over 2400 seats, making it the biggest theatre in town until the slightly larger Capitol was built across the street a year later, also by Rapp and Rapp.

The New Orpheum (hereafter, the Orpheum) was one of those picture palaces that aimed to elevate the filmgoing experience while also being a good community citizen. It had a corps of ushers, a smoking lounge, and a reputation for punctilious service. The theatre sponsored community events too. When the local newspaper launched a marbles tournament, the Orpheum held a screening for 2000 kids.

The kids came early and jammed the State street side of the New Orpheum, so it was necessary to call extra policemen to handle the traffic. Once inside the theatre they yelled and applauded the two comedy features which were shown for them, and practically jumped out of their seats during the showing of “Why Sailors Go Wrong.”

Six months before the 1929 stock market crash, the Orpheum was reportedly selling 20,000-25,000 tickets per week, in a town of about 55,000 souls.

An RKO town

View from the Orpheum stage, Halloween, 1930. Photo by Angus B. McVicar. Collection, Wisconsin Historical Society.

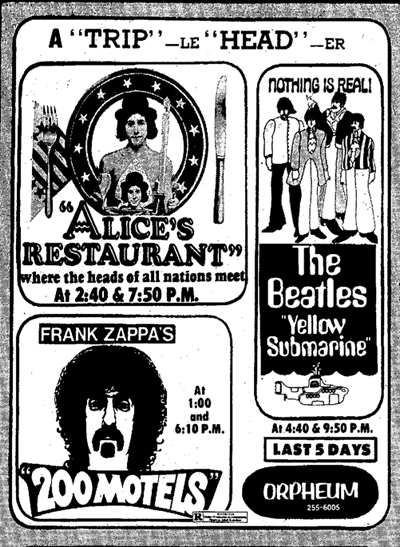

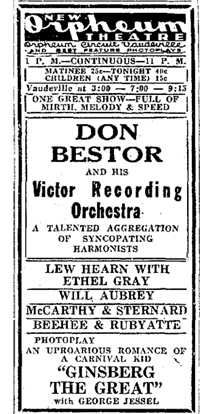

The New Orpheum and the Capitol weren’t in competition, since the Keith-Albee vaudeville circuit owned both. Both houses showed movies, but they seem to have been secondary at the Orpheum. Sometimes Orpheum ads from the late 1920s don’t even mention the titles of what’s playing. (This ad on the right is from 1928.) When talkies came in and the circuit became part of Radio-Keith-Orpheum, films became the central attraction, with live performances as filler. A 1930 kids’ party at the theatre shows the banner flying, “These Madison Boys and Girls Are on their Way to an RKO Theatre.”

The New Orpheum and the Capitol weren’t in competition, since the Keith-Albee vaudeville circuit owned both. Both houses showed movies, but they seem to have been secondary at the Orpheum. Sometimes Orpheum ads from the late 1920s don’t even mention the titles of what’s playing. (This ad on the right is from 1928.) When talkies came in and the circuit became part of Radio-Keith-Orpheum, films became the central attraction, with live performances as filler. A 1930 kids’ party at the theatre shows the banner flying, “These Madison Boys and Girls Are on their Way to an RKO Theatre.”

Despite the Great Depression, RKO moved quickly to monopolize the Madison movie scene. In 1931, the Parkway (capacity 1100) was acquired by the chain, and soon afterward RKO cut a deal with the Fox Film Corporation to take over the Strand (1400 seats). The swap permitted Fox to dominate Milwaukee in exchange for making Madison an RKO town for first-run films. Of course, in good oligopolistic fashion the RKO theatres showed films from all the studios, as did the second-run houses.

I’ve been unable to determine at what point RKO lost control of its Madison screens. [But see the P. S. below.] Presumably it was after the 1948 divorcement decrees severed Hollywood studios from control of theatres. At some point the Milwaukee entrepreneur Dean Fitzgerald acquired seven local houses, including the Orpheum, under the rubric of the Madison Twentieth Century Theater Corporation.

In 1969, a second screen was carved out of the backstage area of the Orpheum and the minuscule theatre that resulted was called the Stage Door. The contrast with the imposing classic house was startling: the Stage Door was almost certainly the worst theatre in town. Then it declined even more. By the end, with its spidery movable chairs and dank atmosphere, it was reminiscent of the storefront theatres of the nickelodeon era, except that they were surely more comfortable.

Less than heavy traffic

Capital Times advertisement, September 1973.

When Kristin and I came to Madison in 1973, we saw a sort of Sargasso Sea of old movie houses. The Majestic, a decrepit vaudeville house built on a plan as cockeyed as an Escher drawing, was showing X-rated fare, kung-fu, and double-bill repertory. It became a Landmark calendar house. A neighborhood house, the Atwood (aka the Eastwood and the Cinema), built in 1930, screened porn and kiddie shows , though not together. The Esquire also offered sex: arty (The Story of O) or not (Dr. Feelgood, with Harry Reems). The mammoth Strand was still functioning as a first-run house; Star Wars played there for months. The Middleton (seating 500 or so) was designed as a Quonset hut in 1946, and was said to have been built in a week. By our day it was playing second run. The Capitol, where I saw The Exorcist, was still operating too. Every year one theatre or another seemed to run the endlessly popular Eastwood Dollars trilogy.

The mall cinemas were emerging as single-screeners or duplexes. They got the premiere first-run pictures like The Sting, often leaving the downtown houses with lesser items. The most obvious options were counterculture movies and sexploitation.

The Orpheum went along. “Entertainment for the Entire Family!” trumpeted a 1965 Orpheum ad, but by 1969 there were revivals of Bullitt and Bonnie and Clyde. Sometimes classier items like The Godfather would show up in second run, but Orpheum fare in the early seventies was more likely to be Heavy Traffic, Enter the Dragon, The Filthiest Show in Town, revivals of headflix (see above), and a double-bill of Russ Meyer’s Vixen and Up! This was the period when the movie page of the papers included ads for This Is Heaven Sauna Massage, The Rising Sun Counseling Clinic (Adults Only), Photographic Arts Do It Yourself Nude Photography (Camera and Film Supplied), Ms. Brews Lounge (Nude Dancing Daily), and The Dangle strip club.

One by one the theatres were closed or converted to other uses. The Capitol became part of an arts complex. The Orpheum remained the only more or less intact movie house from the old days. By 1998, Dean Fitzgerald was ready to sell it.

One by one the theatres were closed or converted to other uses. The Capitol became part of an arts complex. The Orpheum remained the only more or less intact movie house from the old days. By 1998, Dean Fitzgerald was ready to sell it.

Two forces were contending for the property. As part of a plan to revitalize the downtown area, the Madison Idea Foundation proposed putting in an IMAX facility. But preservationists objected that an IMAX setup would wreck the layout of the house. By contrast, restaurant owner Henry Doane (right) favored restoration. He proposed to rehabilitate the old place respectfully and use it for art films, film festivals, and live music. He also wanted to install an upscale café and bar.

Doane won the City Council’s approval and in 1999 he purchased the Orpheum. Throughout the 2000s, thanks to some clever programmers, it played remarkably eclectic fare, from Arnaud Depleschin ‘s A Christmas Tale to Matthew Barney’s Cremaster cycle (running two weeks, no less). In addition, Doane’s plan to revive the Orpheum as a live music venue, with booze, was finding some success. The grand house that had hosted Gene Krupa, Frank Sinatra, Bob Marley, and Journey now had popular indie bands. When local critic Rob Thomas drew up his list of ten-best shows for the decade, Orpheum concerts took five places. Most memorably, Bela Fleck and the Flecktones played to a packed house the night after the World Trade Tower attacks, highlighted by a version of “God Bless America.”

Drinks plus dining plus music kept the Orpheum doors open, but by the late 2000s the place was obviously not flourishing. There were rumors that distributors, long unpaid, were withholding films. The place was becoming disheveled, with seats broken, that stratospheric ceiling ominously peeling, and the sound system a fog of distortion.

Worse, even though most Madisonians had an affection for the old house, nobody much went there to watch a film. Things had started promisingly: Doane’s introduction to the movie business was the blistering summer of Star Wars: Episode I—The Phantom Menace and The Blair Witch Project. But that was an atypical season. During the 2000s, most of the biggest audiences showed up during the Wisconsin Film Festival. It was indeed thrilling to see the place packed out for classics like A Hard Day’s Night (introduced by Roger Ebert) and imports like The Foul King and Wilbur Wants to Kill Himself (both shown in the presence of the directors).

At some point, accommodations were made to favor the concerts: front rows were ripped out to provide dance space.

It became a wretched place to watch movies. Lobby dance parties during screenings could drown out the soundtrack. District 13 was projected within a rectangle framed by a scaffolding erected for an upcoming show. As the decade wore on, you might go to the Orpheum for music, but you didn’t go for the films.

Orpheum vs. Orpheum

Now we know a bit more about what happened behind the scenes in the 2000s. At some point Doane split ownership of the Orpheum Theatre Co. of Madison 50-50 with Eric Fleming, a real-estate and restaurant operator.

Fleming (right) is the sort of fellow who gets called “colorful.” He first made it into the Madison press when he opened Crave, a self-consciously hip restaurant noted for its martinis. “People come here to be out and get a little dressed up,” he told one reporter. “Kind of like a ‘Sex and the City’ place.” Maybe a little too much so: A year later Fleming was charged with disorderly conduct for pouring a drink over a Crave customer and groping a female patron. In December 2008, after an altercation that started in the restaurant, one customer was killed on the street by another in the presence of a Crave bouncer.

Fleming (right) is the sort of fellow who gets called “colorful.” He first made it into the Madison press when he opened Crave, a self-consciously hip restaurant noted for its martinis. “People come here to be out and get a little dressed up,” he told one reporter. “Kind of like a ‘Sex and the City’ place.” Maybe a little too much so: A year later Fleming was charged with disorderly conduct for pouring a drink over a Crave customer and groping a female patron. In December 2008, after an altercation that started in the restaurant, one customer was killed on the street by another in the presence of a Crave bouncer.

Fleming’s business style is traced in Elbow’s article. After Fleming became co-owner of the Orpheum, a busted real-estate investment required him to pay creditors $1.5 million. Seeking to dislodge Doane, he created a new company, Orpheum of Madison, claiming that entity as the functioning business arm. He folded that into a package of assets he transferred to Ms. Olesya Kuzmenko for $175,000. “This is what I do for a living,” Fleming explains in Elbow’s article. “I create things and I sell them.”

Who is Kuzmenko, who wound up with a mammoth downtown theatre for the price of a small house on the outskirts of town? She is believed to be Fleming’s girlfriend, but beyond that little is known. She is listed on a license application as President, Vice-President, Secretary, Treasurer, Director, and sole stockholder in Orpheum of Madison. A few years before, Fleming had sold Crave to Christina Bishop, his secretary and girlfriend at the time, under the rubric of a new company Evarc (Crave spelled backward).

There were some curious incidents over these years. There were three fires at the Orpheum, at least two considered by the police to be arson. So far no arrests have been made in the cases. There was also reportedly a break-in, during which a computer was stolen. Perhaps the strangest incident involves the fate of Kuzmenko’s payment. Elbow’s article reports Fleming’s account:

He withdrew the $175,000 he got from Kuzmenko in $100 bills from his bank account, put the cash in a plastic bag and handed it over to a guy identified in court records as Marcus DaMarko, and never saw it again.

“I loaned somebody money,” says Fleming. “I loaned him some money to invest in something. I haven’t talked to him since so I don’t have the money currently.”

So, a reporter asks, you were taken?

“Essentially.”

One more for the road

Because of these maneuvers, Fleming has been running the Orpheum for over a year without input from Doane. The newest issue involves alcohol.

Wisconsin, you must understand, has a frenzied drinking culture. We lead the nation in binge drinking, drinkers per capita, heavy drinkers per capita, and drunk driving. Madison’s main downtown artery, State Street, is packed with bars and restaurants, and the UW’s reputation as a party school attracts an endless supply of youths eager to get wasted. Consequently, what state law calls “alcohol beverages” have been central to the revival of the Orpheum. To establish the lobby restaurant (above) Doane needed to serve beer, wine, and spirits. And Fleming’s cash flow in recent years has been boosted by numerous weddings, which demand booze.

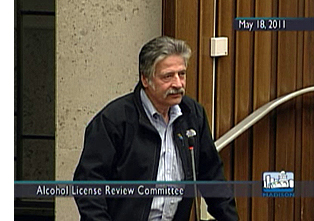

But over the years, the Orpheum’s state vendor’s permit and its liquor license have become problematic. Just during the fall of 2006, the venue under Fleming’s management accumulated some 200 points of alcohol-related violations, and there was a demand that its license be suspended. Across the spring months of 2011, things became more dramatic.

In a series of appeals to the Alcohol License Review Committee of the Common Council, Fleming began to press for the Orpheum’s liquor license to be transferred to his company, Orpheum of Madison. He assured the ALRC that Doane’s original company, Orpheum Theatre Co. of Madison, would be evicted from the premises. Doane replied he knew nothing about this, and indeed he was not evicted. Moreover, he argued that Fleming was making purchases for his own company but billing their original one. And Fleming, he claimed, had changed the door locks. The ALRC, declining to step into the middle of the feud, decided to let Doane’s original company hold the license until ownership was clarified.

Auction fever

That fracas took place a year ago, but things really got going this spring. While Doane was suing Fleming to regain control of the building, the Orpheum faced foreclosure because of unpaid bills. In April it went on the auction block.

Enter Gus Paras (right), once Fleming friend and now Fleming foe. “He sued me and cost me a lot of money,” Paras explained. “The other thing is I watched people he screwed so bad he put them on their knees.”

Enter Gus Paras (right), once Fleming friend and now Fleming foe. “He sued me and cost me a lot of money,” Paras explained. “The other thing is I watched people he screwed so bad he put them on their knees.”

Gus Paras had had many dealings with Fleming when both sought to buy property in the area. Now Paras wanted the Orpheum as well. But when the property went to auction, along with the 300 block that had also been part of the Fleming/ Kuzmenko package, Olesya Kuzmenko showed up and began bidding against Paras. In a scene reminiscent of the auction in North By Northwest, she bid the price for the Orpheum up to $1.9 million, but Paras won it for $2.25 million. She bid again on the 300 block properties, but Paras bid her up and then folded, leaving her stuck with her $2.25 million bid. But she couldn’t make the down payment, so the court gave both the Orpheum and the 300 block to Paras for $1.9 million each. However, as of this writing, the sale has not yet been consummated. A court will need to determine who actually owns the building.

In the meantime new alcohol problems resurfaced. Doane requested that the Orpheum’s state seller’s permit not be reactivated. It expired. But the Orpheum continued to sell booze. For a time it seemed that every drink poured since April 2011 had been in violation. A June 2012 story explained:

[Assistant City Attorney Jennifer] Zilavy said the Orpheum should not have served alcohol at concerts and other events. She isn’t sure if the city will pursue civil charges, which could result in a $1,000 fine for each infraction, or refer the matter for criminal charges, which could result in a fine of up to $10,000 or nine months in jail per offense.

As a result, last month the Common Council of the city declined to renew the Orpheum’s liquor license. When the police tried to serve notice of non-renewal, they were unable to rouse anyone. “It is locked up, lights out, nobody there,” reported the officer. Now, however, it seems that Fleming managed to re-activate the license fairly soon after Doane deactivated it, so it’s unclear how long, if at all, the Orpheum was serving drinks illegally.

The city later discovered that Fleming, nothing if not tenacious, was at some point granted a state seller’s permit for his new company. But as of early July the sort-of-partners remained at loggerheads. Doane’s company had a liquor license but no seller’s permit. Fleming’s company now has a seller’s permit but no liquor license. And Doane’s company’s liquor license expired last Saturday. The Madison Common Council has sent the matter to the ALRC for a public hearing. possibly as soon as next week.

I wish I could answer every question that’s come up. Who is Mr. DaMarko, and what became of the 1750 $100 bills? If Paras finally acquires the building, what status does Fleming’s operation have with respect to it? What about Doane’s stake in the theatre he originally bought?

One thing seems certain: If the old place resumes operations, it will be as a venue for weddings and live music, with a bar and perhaps a café. As movies evicted vaudeville from the Orpheum in the 1930s, so now live performance has replaced movies. The drama and comedy have moved off the screen into the streets, the Common Council, and the halls of justice.

Steven Elbow follows up his main story here. If anything develops, he will probably report on it in his blog.

The Orpheum website reflects the chaotic state of its circumstances. Videos of the ALRC hearings, from which my three portraits of the protagonists are taken, may be streamed here and here. In late June, Eric Fleming conducted a brief video tour of the Orpheum’s restorations. The most recent application from Kuzmenko’s company requests that the liquor license begin on 1 July 2012 and end on 30 June 2012. Will the fun never stop?

Some accounts date the Orpheum from 1926, but it opened in March 1927. (See, for example, “New Orpheum’s First Birthday Cake,” The Capital Times, 3 April 1928, 3.) To view more magnificent Orpheum photos from the Wisconsin Historical Society collection, go here. The color shot of the Lobby Restaurant is from the Onion. (The Onion originated–where else?–in Madison.) The color shot of the missing front rows is from the 2010 Wisconsin Film Festival. For a sense of what a wedding looks like in the Orpheum, go to Valo Photography.

Wisconsin’s mad flight from sobriety is documented in the Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel‘s award-winning series. As far as I know, nothing much has changed since that 2008 survey.

This has been my Year of Living Exhibitionistically; see the Pandora posts and the e-book for accounts of different movie theatres. Older entries are here and here.

P.S. 15 July 2012: Douglas Gomery writes that RKO probably lost its grip on the Orpheum and other theatres much earlier than I speculated:

The Film Daily Yearbook of 1931 lists RKO holdings in Wisconsin: Madison, the Capitol & Orpheum; Milwaukee, the Riverside; and Racine, the Downtown (literally). In 1932 RKO goes into bankruptcy, and all its Wisconsin holdings disappear from FDY. My guess is that the Orpheum and other houses became locally owned.

Douglas wrote the definitive book on American exhibition, Shared Pleasures, and I thank him for the correction.

P.P.S. 16 July: My original post indicated that Kuzmenko won the Orpheum temporarily before she proved unable to make the down payment. Steve Elbow corrected my claim on this: what she acquired at auction was actually the 300 block property, which had been folded with the Orpheum into the overall property Fleming sold her for $175,000. Gus Paras bid successfully on the Orpheum itself.

The blog has been revised to reflect another piece of information Steve provided me: that Fleming may have reactivated the Orpheum’s liquor license quite soon after Doane deactivated it. Thanks to Steve for these corrections.

P.P.P.S. 27 May 2013: A query from Laura Ursin has led me to correct the date in the caption of the top photo, which I had dated from 1938.

The Orpheum Theatre under construction, 1926. Photo by Angus B. McVicar. Collection, Wisconsin Historical Society.

The Gearheads

Mourning.

DB here:

At the Wisconsin Film Festival I saw the best film I’ve seen over the last six months. I can’t really say much about it, but I’ll do what I can. My remarks make most sense, I think, if I embark on a pretty long detour.

The frame-rate shuffle

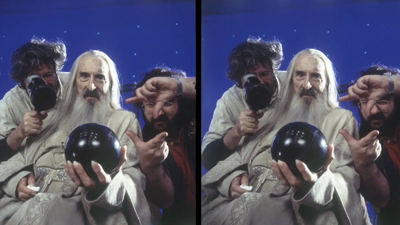

3D still photographs by Peter Jackson taken during the filming of the Lord of the Rings trilogy.

In the wake of April’s convention of the National Association of Theater Owners, the biggest press tumult surrounded Peter Jackson’s ten-minute demo from The Hobbit. Fulfilling what James Cameron had called for at the 2011 NATO confab, Jackson has been shooting at 48 frames per second, and the demo was screened at that rate. Cameron and Jackson are concerned that there’s too much image judder and strobing in digital cinema, especially 3D. They propose a higher frame rate to smooth things out.

Opinion on the Hobbit footage was divided. Some theatre owners and operators were happy with it, but others were uneasy. The higher frame rate tends to eliminate motion blur and create a sharpness that recalls, for some viewers, the brittle look of HD sports broadcasts. “It looked to me like a behind-the-scenes featurette,” said one.

Jackson, who has been preparing for this initiative on his Facebook page, defended his decision. He maintains that audiences will adapt to it, just as his production team has. Many exhibitors seem to have dismissed the new initiative as too expensive, particularly at a time when many are still paying off the digital conversion. But the Regal Entertainment Group, the largest cinema chain in the US, announced plans to outfit up to 2700 screens so that The Hobbit can be screened at 48 fps. It now seems possible that The Hobbit may be shown in no fewer than six formats: 2D, 3D, and Imax, and in each there will be both 24 fps and 48 fps presentations.

Not being present to watch the footage, I have to withhold judgment about how it looks. I haven’t though, withheld my opinion about how Cameron and Jackson, along with George Lucas, have used their roles as superstar directors to prod exhibitors to adopt expensive new technology. They acted as the figureheads for the switch to digital in 2005, using 3D as the incentive for exhibitors to convert. A few years later, after proposing 3D television, Cameron upped the ante by urging higher frame rates for film. Jackson has joined him by actually making a film at 48 fps. Cameron has said he prefers 60 fps, which may mean that the goal posts get shifted again when Avatar 2 or something else comes along.

You can go to my earlier post for more thoughts on their tactics. My book on the digital conversion, due out on this site in a few days, offers a fuller account. In the meantime, I’m going to try to understand this frame-rate fracas in a wider historical context.

The palette

Cinema technology has been surprisingly stable, as befits its status as the last surviving nineteenth-century engine of popular entertainment. The dimensions of the film strip, the rate of shooting and showing, and other fundamental factors have altered relatively little. The coming of sound and then the replacement of nitrate-based film by acetate are perhaps the biggest alterations in the basic technology. Below this macro-level, though, innovation has been constant.

From the 1920s through the 1960s, most of the change came in the production sector. The adoption of panchromatic film stock; color processes, principally Technicolor and the monopack systems like Agfacolor and Eastman Color; the development of various lighting units (carbon-arc, incandescent, Xenon); the shift from optical sound recording and reproduction to magnetic processes; the emergence of different sorts of camera support (varieties of tripod, dollies, and cranes, along with handheld devices)—all of these shaped how movies were made but had relatively little effect on how they were shown.

Some 1950s innovations launched in the production sector, notably widescreen cinema, stereophonic sound, and 3D, reshaped exhibition more drastically, because they came at a moment when theatres were anxious to lure back their clientele. Other revampings of exhibition, like wide-gauge film (65mm/70mm) and Cinerama, were never intended to be the universal standard. They were designed for a distribution system that included roadshow exhibition. Dedicated screens showcased big films like The King and I and Lawrence of Arabia for long, well-upholstered runs before the film hit the neighborhoods and the suburbs.

Producers innovate and exhibitors hesitate. Exhibitors must be cautious and conservative; they risk revamping their venue at great cost only to find that the new technology isn’t catching on. The roadshow system repaid exhibitors well, until it collapsed in response to the rise of saturation booking in the 1970s. For similar conservative reasons, exhibitors looked askance at the digital sound reproduction technologies that emerged from the 1970s through the 1990s. At one point, a house had to accommodate four different sound systems, some of them subject to periodic upgrades.

When technologies emerge in the production sector, they mostly promise to enlarge the filmmaker’s palette. A 1950s film could be made black-and-white or color, deep-focus or soft-focus, with arc or incandescents, flat or anamorphic, and so on.

In practice, of course, not everything was possible on every project. Budgets, as ever, limited options, and many directors and DPs disliked shooting in color or CinemaScope but were obliged to do so. And there were some trade-offs. Filmmakers of the 1930s could not shoot on orthochromatic stock, and after the mid-1950s, it was hard to make a film destined for the classic 1.37 Academy ratio. Still, there were few absolutely forced choices, and many directors explored different options from project to project.

The prospect of an enhanced palette is in fact one reason that some filmmakers embraced new technologies. Sergei Eisenstein (who trained as an engineer) was eager to try out sound, color, and even television because they expanded creative choice. Orson Welles saw in the RKO effects department, which had pioneered sophisticated optical-printer work, a way to create images that couldn’t be generated in the camera. As is now widely known, many of Citizen Kane’s most famous “deep-focus” shots were achieved through special effects. Similarly, Stanley Kubrick renewed the power of his images through his eager adoption of new technologies, including long lenses for Paths of Glory, the handheld camera in Dr. Strangelove, faster lenses for Barry Lyndon, and the Steadicam for The Shining. These filmmakers wanted to multiply options, not foreclose them.

Share our fantasy

The changes that Cameron and Jackson propose are more sweeping. Now that digital projection is an accomplished fact, there will be backward pressure to create a wholly digital workflow. Filmmakers who want to shoot on 35mm will be reminded that they will eventually be fiddling with a digital intermediate, and that the final version will be digital, not film-based. A selling point of digital cinema to the creative community was the promise of complete control over the film’s look and sound, so that the audience gets exactly what the filmmaker envisioned. To assure that integrity, the director will have to shoot and finish the project on digital. That will take away an entire dimension of choice—specifically, shooting on film.

The pressure to shoot 3D adds to this. Martin Scorsese and Ang Lee showed up at the same NATO convention to praise the format. Now films that aren’t tentpole items can be made in 3D, they agreed. According to Variety, Scorsese claimed that “2D projection [sic] will eventually go the way of black-and-white—used primarily as a stylistic choice—as auds will soon acclimate to depth even in indie films.” This sounds like a widening-of-the-palette defense, as does his reaction to new frame rates. “You can do anything you want [in post-production] with that image at that level of clarity, can’t you?”

In contrast to Scorsese’s offhand pluralism, Cameron, Jackson, and their confrère Lucas may be creating a scorched-earth policy. Their conception of cinema, I would say, is now largely that of the Gearhead. Their notion of artistry has become quite mechanical, in that they see progress to depend almost wholly on improved hardware (and software).

They represent three mini-generations of Hollywood techno-lover: Lucas, who began in animation; Cameron, who started as a model-builder; and Jackson, the 1980s fanboy who played with King Kong action figures. They are directors who treat cinema as a delivery system for stories grounded in genre conventions. Fantasy is their touchstone, and realism of any sort bears only on how vividly we perceive the images, not what the films show or say or suggest.

Back in 1999, Lucas noted frankly that film was becoming a form of painting, “unfixing the image.”

You have news footage, you have documentary footage—which are supposedly realistic images—and then you have movies, which are completely fantasy images. There’s nothing in a movie that’s true or real—ever . . . . The people in the movie are actors playing parts. The characters are not real. The sets are not real. If you go behind that door you’ll see there’s no building—it’s just a big flat piece of wood. Nothing is real. Not one little tiny minutia of detail is real.

The Hollywood cinema was then putting fantasy and special effects at the center of its aesthetic, and Lucas understood that every film—action picture, romantic comedy, even dramas—would rely on special effects to a new extent.

Here’s Cameron saying the same thing in defending 3D in 2008.

Godard got it exactly backwards. Cinema is not truth 24 times a second, it is lies 24 times a second. Actors are pretending to be people they’re not, in situations and settings which are completely illusory. Day for night, dry for wet, Vancouver for New York, potato shavings for snow. The building is a thin-walled set, the sunlight is a Xenon, and the traffic noise is supplied by the sound designers. It’s all illusion, but the prize goes to those who make the fantasy the most real, the most visceral, the most involving. This sensation of truthfulness is vastly enhanced by the stereoscopic illusion.

It’s hard to believe that Lucas and Cameron don’t know the long tradition of debate in the arts about realism. Realism can be considered a question of subject matter, plot plausibility, random detail, psychological revelation, and many other things; it isn’t just about trompe l’oeil illusion. Moreover, documentary and experimental filmmakers have suggested that cinema can capture moments of unplanned truth. And André Bazin and others have argued that even when presenting fictional tales, photographic cinema gives us unique access to some essential qualities of phenomenal reality. For Bazin, even an awkwardly shot scene could preserve the sensuous surface of things with a conviction that no painterly manipulation can equal—not perfection but brute facticity. Instead, Lucas and Cameron offer a Frank Frazetta notion of realism: glistening, overripe, academically correct rendering of things we’ve seen many times before.

Turnstile dynamics

NATO’s 2005 ShoWest convention: Lucas, Robert Zemeckis, Randal Keiser, Robert Rodriguez, Cameron.

I see a valid place for a cinema of splendor and spectacle, especially in certain genres. There’s nothing wrong with seeking new methods of pictorial representation, as Spielberg did in Jurassic Park, a genuine triumph of veridical realism. Nor am I trashing Lucas and Cameron wholesale; I admire their early films a fair amount. But they’re forcing their conception of cinema on all filmmakers.

Am I being unfair? I don’t think so. When directors say that digital or 3D or 48 fps is the future of cinema, they’re implying wholesale conversion is in the offing. Although Scorsese says that 2D or another frame rate will remain an option, Cameron and Jackson aren’t quite so open-handed. Because they’re convinced that the result is much more immersive, and immersion is always good, the technology should suit every kind of movie. Cameron again:

It is intuitive to the film industry that this immersive quality is perfect for action, fantasy, and animation. What’s less obvious is that the enhanced sense of presence and realism works in all types of scenes, even intimate dramatic moments.

Both directors usually add that they’re not insisting that every film is suited to the new bells and whistles, that it has to suit the plot and so on—the usual boilerplate about the primacy of “story.” “Stereo [imagery] is just another color to paint with,” says Cameron.

But they sound as if not having 3D or 48 fps puts the movie at a disadvantage. Cameron in 2008:

Every time I watch a movie lately, from 300 to Atonement, I think how wonderful it would have been if shot in 3D.

Jackson in 2011:

You get used to this new look [48 fps] very quickly. . . Other film experiences look a little primitive. I saw a new movie in the cinema on Sunday and I kept getting distracted by the juddery panning and blurring. We’re getting spoilt! . . . There’s no doubt in my mind that we’re headed toward movies being shot and projected at higher frame rates.

As happened before, the pronouncements of the directors mesh well with the initiative of the manufacturers. Back in 2005, Cameron, Lucas, Jackson, Robert Rodriguez, and Bob Zemeckis took to the NATO stage to help sell the Digital Cinema Initiatives program to skeptical exhibitors. Their support (and the box-office numbers of the 3D Chicken Little) aided the projector manufacturers Christie, Barco, NEC, and Sony in rolling out units. The number of digital screens in the US and Canada jumped from ninety in 2004 to over 300 at the end of 2005.

This year, with about two-thirds of all US screens fully converted, Christie circulated a promotional leaflet tied to Jackson’s demo. A few years ago, the future was all about 3D, but now, the text states flatly, “The future of cinema is all about high frame rates.” The cards are on the table.

At just 24 FPS, fast panning and sweeping camera movements that are a critical part of any blockbuster are severely limited by the visual artifacts that would result. . . .

The “Soap Opera Effect” has been derisively used to describe film purist perceptions of the cool, sterile visuals they say is [sic] brought on by digital.

But the success of Hollywood, Bollywood and big-budget filmmakers around the world has little to do with moody art-house films. The biggest blockbusters are usually about immersive experiences and escapism—big, vibrant, high-action motion pictures.

The HFR system, then, aims to spiff up franchises and tentpoles, and all other filmmaking must be dragged along and adjust. Although Jackson says he has heard no plans to charge more for 48 fps shows, Christie thinks we would pay for this treat:

Beyond the simple turnstile dynamics of “must-see” movies, a new, higher standard of movie-going should support premium pricing. Managed right, hotly-anticipated 3D HFR should empower ticket up-charges.

By all signs, the churn won’t stop. “Every three months you’re behind,” says Ang Lee. “We’re guinea pigs.” David S. Cohen, technology writer for Variety, believes that 48 fps is a transitional technology and that 60 fps will win out (“but not soon”). He adds: “Bizzers in both TV and movies are going to be making creative and financial decisions about HFR for years—maybe forever.”

Lucas and Cameron, and then Jackson, grasped that if cinema technology went wholly digital, it would change in fundamental ways. It would turn a medium into a platform, like a computer operating system. The most basic technology of showing a movie would become subject to rapid, radical, ceaseless remaking. It would demand versions, upgrades, patches, fixes, tweaks, and new software and hardware indefinitely.

I’m not sure that NATO’s members have fully realized this. They went into the deal lured by the chance to raise ticket prices and thus offset flat or slumping admission numbers. But attendance is still stagnant, even with the occasional stupendous successes like Avatar and The Avengers. Interestingly, AMC, one of the Big Three circuits that invested heavily in digital projection, is reportedly in talks to sell out to Chinese investors, and other chains are on the auction block. The studios are proceeding with VOD plans that may thin theatrical attendance even more.

Meanwhile, exhibitors face a long future of payouts. When cinema goes IT, as Steve Jobs might put it, we should expect a big bag of pain.

And now for something completely different

I saw Morteza Farshbaf’s Mourning (Soog) on a so-so DigiBeta copy at the Wisconsin Film Festival. This Iranian feature was shot on some godforsaken digital format, certainly nothing that Cameron and Company would approve. For all I know, its camera movements may have strobed unacceptably. I didn’t care.

Cameron et al. claim to worship the god of Story, but no film they’ve made has this subtle a grasp of narrative. Mourning gives us a plot so full of twists—in terms of what happens and how we learn about it—that I can’t summarize even the basic situation without subtracting some of your pleasure. A man and a woman are driving a little boy through a landscape. That’s about all I can tell you.

The film critics at Christie would consider it a moody art-house film. It’s also simple, suspenseful, and surprising, even shocking. It is formally inventive, emotionally poignant, and respectful of its characters and its audience. It is gentle but also unflinching. It’s the closest thing to Chekhov I’ve seen onscreen in a long time.

Was I immersed? Yes, but not in the way Cameron et al. define that state. I was trying to figure out what had already happened, what was happening at the moment, and what might happen next. And maybe I wasn’t seeing things “realistically,” in the 3D sense, but I was seeing something that captured the world we live in—our surroundings (and their stubborn physicality) and our relations to others. That world was also poetically heightened through the most straightforward means: camera placement, lighting, cutting, sound design. The film was, in other words, working in ways that we have always considered central to cinema’s creative mission.

Mourning is part of the fine Global Lens program of circulating features. Here’s a schedule of where and when films in the program are playing. Ask your local festival or art house to book Mourning, or try to see it when it’s available online or on disc. It’s even worth an upcharge.

Lucas’s remarks on realism come from “Return of the Jedi,” an interview with Don Shay in Cinefex no. 78 (July 1999), 18. Figures on the adoption of digital cinema are taken from the report, “Digital Cinema Roll-Out Begins,” Screen Digest (April 2006), 110. A detailed video explaining Hobbit production methods is here, as part of the video diaries on Jackson’s Facebook page. For more from a veteran, see “‘The Hobbit’: Douglas Trumbull on the 48 Frames debate.”

After writing this, I found that Devin Faraci of Badass Digest has a vigorously critical entry on the footage and even calls Jackson and Cameron “gearhead directors.” So I can’t claim originality, but it’s nice to know I have a badass ally.

Thanks to Jim Cortada, author of the forthcoming Digital Flood and Co-Director of the Irvington Way Institute, for explaining IT matters to me.

P.S. 11 May: Christopher Nolan, still embracing film-as-film, claims he’s no gearhead.