Archive for the 'Movie theatres' Category

Pandora’s digital box: Harmony

DB here:

I had thought I was finished with my series on digital projection that started back in December. That was before a late-night trawl of the Internets brought the JEM Theatre to my attention. Sometimes reality has a taste for a dramatic story, and this was one I couldn’t resist.

So I went to Harmony.

All in the families

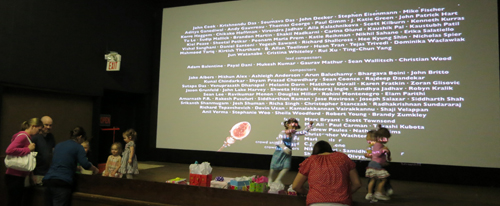

A birthday party at the JEM Theatre.

For decades exhibiting movies has been a family business. Many regional chains were founded by fathers and brothers and staffed by sons, daughters, and in-laws. The Midwest’s Marcus chain of 700 screens originated in 1935 with grandfather Ben and is run by son Stephen and grandson Gregory. More modestly, Smitty’s Cinema, a nine-screen movies-and-eats circuit in Maine and New Hampshire, was the brainchild of three brothers.

The smaller the venue, the more likely you’ll find a family in charge. The Goetz Theatre of Monroe, Wisconsin, which I profiled earlier, has been in the family from the start. The single-screen Cozy in Wadena, Minnesota, has been run by the Quincers since 1923, with the founder’s great-grandson in charge today. Dirk and Jeri Reinauer have the Sunset Theatre in Connell, Washington. Tom and Barbara Budjanek, who bought Pennsylvania’s Ambridge Family theatre in 1967, are still running it in 2012.

Families pass theatres to each other. The venerable Roxy in Forsyth, Montana, was bought by a couple in 1967. They sold it to their projectionists, one of whom kept it going with his wife. (The theatre went digital in 2010, just in time for its eightieth birthday.) From 1947 to 1959 the Wayne Theatre in Bicknell, Utah, was operated by a husband and wife. Another couple bought it and ran it until 1994, when they sold it to a third husband and wife. A fourth family acquired it in 2008.

The record for husbands and wives running a single-screener might be held by the little town of Harmony, Minnesota. The JEM Theatre on the main street, closed in 1947, was reopened by Bob and Hazel Johnson in 1961. They ran it for twenty-five years. It passed through the hands of five more couples before Michelle and Paul Haugerud acquired it in 2002.

Paul and Michelle met in San Francisco, where Michelle was working for Bear Stearns and Paul had served in the Navy. In 1994 they moved to Harmony to be near Paul’s family. There they raised six children while Paul started a paint and drywall business and Michelle began a career in Web design. “When we bought the theatre,” Paul explained, “we knew it was gonna make no money. We knew it was gonna be basically like doing community service.”

To an extent that people living in cities and suburbs may not appreciate, the JEM has held a central place in the life of the town. By 2011, digital conversion threatened to end that.

Harmony, not far from Prosper

With a population of about a thousand, Harmony sits in farm country close to the Iowa border. As Prairie Home Companion reminds us every week, people of Norwegian descent are found all over Minnesota. What you may not know is that certain areas are also home to Amish communities. Waves of migration made Harmony a center of Minnesota’s Amish culture. Local businesses serve the five hundred households in the town, and tourism brings in some income too. One of the big attractions is Niagara cave, containing fossils pre-dating the dinosaurs. There’s also a major biking trail and a fall foliage tour.

The JEM was named, supposedly, for the first letter in the names of the original owner’s three children (but see the PS below). It helped knit the town together, and under the Haugeruds it became a unique institution.

They made a solid team, with Paul’s expertise in carpentry and engine repair matched by Michelle’s money-management skills. Paul, with no previous theatre experience, learned to thread up the platter projector. “The first few weeks, I would literally sit there with sweat rolling down my face as I pushed the start button. I’d be so nervous I did something wrong.” Paul introduced screenings with announcements and jokes. The Haugeruds knew most of their patrons, but at every screening there were fresh faces from nearby towns in Minnesota, Iowa, and Wisconsin.

The JEM screened only on weekends, once each day at 7:30. Paul’s and Michelle’s day jobs made any other schedule impossible. During football season, Fridays brought in few teenagers, but Saturdays were better and Sundays were quite good. Overall, the 200-seat house averaged around 55 each night. On snowy nights, a few souls still braved the Minnesota winter to come see a movie.

The Haugeruds ran the JEM as a family business. There was no paid staff. The Haugerud kids sold tickets and snacks and helped with cleanup. Friends and volunteers came out as well. Michelle made the pre-show video slides of ads for local businesses. Even with low overhead, the theatre barely broke even. All tickets were $3. “We’ve always kept prices low,” Michelle explained, “so families that are financially hardshipped can still get their kids out of the house.”

Most of the JEM’s programs were subruns—movies that had opened nationally two or three weeks before. To avoid courier service costs, Michelle and Paul would make midnight drives to pick up prints from other towns. “I’d call and they’d just be breaking down their print from their last show on Thursday,” she says. “I’d say, ‘I’ll be there in fifteen minutes,’ and at midnight I’d go get the print for Paul to make up on Friday.”

Snack concessions are the core of every theatre’s income, but even here Paul and Michelle offered deals. They priced their candy at a dollar and a big tub of popcorn at four bucks. Soda was sold in plastic bottles, to allow for recycling and to keep costs down. Instead of getting concession items from theatre suppliers, Michelle bought them in bulk at Sam’s Club.

The JEM popcorn developed a following. High schoolers came to pop and bag it for football games. Paul and Michelle encouraged people to bring their own buckets to be filled with corn at a fixed price; some people showed up with shopping bags. The Amish didn’t come to the films, of course, but on some days you could see a horse and carriage lingering outside while the driver was buying a supply of popcorn.

The Haugeruds were generous with free passes as well. Over the years, they have donated hundreds of free passes to help local organizations raise money. At other times, Michelle realized, passes are a good form of marketing. “Give out one, and three more people will come along to pay.”

The JEM wasn’t just for movies. Youth groups held meetings there. Many local kids had their birthday parties there, accompanied by a movie or a videogame. The Haugerud daughters had slumber parties in the auditorium; after a movie, they settled down, if that’s the right word for a slumber party, in sleeping bags down front and in the aisles.

Many in Harmony believed that the JEM brought business to town. Julie Barrett, owner of the Village Square Restaurant across the street (and famous for her daily pies) said, “When people go to the movie, they stop at the Kwik Trip, our hardware store is open until 6:30, so you know they might try to kill two birds with one stone when they come to town.”

Over the situation hovered the fate facing every small town—the hollowing out of the center by the big-box stores down the road. Pull off any interstate highway, and you’ll see that the main streets of small towns have turned into empty storefronts, municipal offices, or struggling boutiques. When the JEM faced the need to go digital, Paul was concerned. “If we take one more thing away it’s going to hurt the community. I’m scared to death that main street is going to look like Harmony in the 1980’s when I was growing up. It was pretty bare.”

Single-screeners

Tonja Lawler selling tickets, Michelle Haugerud selling concessions.

The major distributors and the National Association of Theatre Owners now seem to take for granted that thousands of screens will close over the next few years. Some will fail to convert; others will struggle to pay for the conversion but still fold up. What are the likeliest victims? Those at the bottom of the food chain, the single screens and the “miniplexes” holding between two and seven screens.

These two categories account for over half of all exhibition sites in the US. But they amount to only a small slice of the total number of screens, which is what matters. And the number of small houses is shrinking. During the bankruptcy convulsions of the 1999-2001 period, circuits shed hundreds of screens. Since 2007, the total number of U. S. screens has remained fairly constant, but multiplex and megaplex installations have swollen by 2000 screens. Smaller facilities have lost about the same number—by going out of business.

Hollywood, people like to say, doesn’t want to leave money on the table. But more and more the long tail is a waste of resources. Why bother to prepare and ship a DCP to a theatre that yields a box-office take of less than $300 per day? Many decision-makers among the major distributors would be just as happy to let people in small towns wait a couple of months and catch the film on VOD or disc (rented from a gas station, since the video stores are gone too). As long as the megaplexes publicize the must-see movies, people will know what to buy or rent or stream. If you live in the countryside and you really feel the urge to catch the latest hit, get in your car or pickup and drive an hour to a ‘plex. No vehicle? Too young to drive? Wait for the video.

While digital projection allowed the major distributors to consolidate their power, it also offered a way to streamline and downsize exhibition. The 1600 American single-screen venues are especially vulnerable. For the industry, it seems, any part of film culture that preserves some history or takes root in a community is simply a nuisance. Michelle Haugerud puts it simply. “They don’t care if we go out of business.”

A digital jug

In late spring of 2011 Paul and Michelle decided to try to go digital. A new projection system and sound processor would cost $75,000. “We’ve tried to run it by ourselves and keep it independently owned, but it’s gotten to the point now where we’re looking for some help,” Paul said in July. “It was a difficult decision to ask for the community’s help,” Michelle wrote on her website. “We never wanted to ask for support, but we knew the public deserved to know why we may have to go out of business.”

In late spring of 2011 Paul and Michelle decided to try to go digital. A new projection system and sound processor would cost $75,000. “We’ve tried to run it by ourselves and keep it independently owned, but it’s gotten to the point now where we’re looking for some help,” Paul said in July. “It was a difficult decision to ask for the community’s help,” Michelle wrote on her website. “We never wanted to ask for support, but we knew the public deserved to know why we may have to go out of business.”

They began a fundraising drive. A young patron named Kirsten Mock decorated an old red juice jug for donations and put it on the candy counter. Paul and Michelle set up a designated savings account with a local lawyer’s name attached to make sure people understood that any donations would go only to the projector. A list was kept of all who put their names on donations, and the money would be refunded if the target sum weren’t reached.

The problem was that the JEM, privately owned and operated, wasn’t a nonprofit. Donations were not tax-deductible, and local government agencies couldn’t normally supply grants or other aid. During 4 July celebrations, however, a “Harmony Goes Hollywood” event featured a room in the Historical Society set up with an old projector and theatre seats, with clippings and photos showing the JEM over the years.

A local woman tipped Twin Cities media to the campaign. It was good timing: The US press was starting to notice the nationwide digital conversion. News outlets and TV stations covered the JEM’s crisis. Minnesota Public Radio picked up the story.

By fall, when the campaign had raised about $7200 locally, Paul and Michelle found a nearly new projector for $55,000. They managed to borrow the $48,000 they needed from a local bank. By shouldering the loan themselves, they showed the public that they were committed, and this gesture boosted donations.

As a result, on 11 November, the JEM screened its first movie on the Digital Cinema Package format, Dolphin Tale. On that weekend Paul thanked Kirsten for kicking off the fundraising and gave her a lifetime pass to the JEM. For the older crowd there was Football Monday, when Paul and Michelle projected a Vikings-Packers game. They couldn’t charge admission, but they sold tickets for drawings of prizes donated by local businesses.

Even though they had the equipment, Paul and Michelle still needed to pay for it. Later in November, the Trust for a Better Harmony stepped in to help. Enabled by a generous gift from Ms. Gladys Evenrud, the Trust and a Minnesota agency for community development arranged for a flexible loan package. As a result, the JEM now needed only $28,000, to be paid from community donation. The loan sparked still more offerings to the projection bank account.

New decisions

Paul Haugerud, son Peter (in overalls), and local boys tour the JEM booth.

On 13 January of this year, Paul died.

Commander of the local American Legion, he was cremated with military honors. He left behind Michelle, his six children, his parents, four brothers, and two grandchildren. The town grieved. “There’s nothing he wouldn’t do to help someone else,” a friend said.

Michelle remembers weeks going by in a blur. Friends brought over way too much food. “I had to freeze a lot of it.” She decided she simply had to move forward. She had a full-time job and had Peter, Julia, and Sierra at home, but she would keep running the JEM.

In February, a fundraiser was held at Wheelers Bar & Grill. The event had been planned before Paul’s death, but now it gained a new urgency and poignancy. Wheelers is named for its big roller rink, where Paul had helped out often. Across the day Wheelers held a silent auction and some bean-bag and darts tournaments. Those, along with food, drink, and music, raised an astonishing $16,000. That, plus the balance in the digital account, yielded enough to pay off the bank note for the projector. There have been more fundraising events, including a pancake breakfast. Michelle will soon pay the rest of the money owed. Any funds left over will be used for upgrades. Michelle is considering 3D conversion in a year or two.

Saturday night at the movies

Things have happened so quickly that Michelle hasn’t had time to thank everyone fully on her website, but she adds in a note to me:

It is so overwhelming to think of how the entire community and beyond has come together to make this all happen. I know that even though I am now the owner/ operator of the JEM, this theatre will be here for generations to come. I have had so many thanking me for staying in business. I know this is part due to the conversion and part due to Paul’s passing. I am very grateful for Paul’s family and my friends for being there helping me through all this.

Last Saturday, The Hunger Games drew a robust crowd, mostly groups of boys, groups of girls, and families, with a few elders sprinkled in. Nearly everybody bought concessions. Many carried in buckets for popcorn. The ticket booth was decorated with Easter rabbits and a Darth Vader helmet.

Upstairs, I saw a little room off the projection booth with a porthole. It was Michelle’s and Paul’s “private screening room,” she explained. They would watch the show from an old car seat there.

On the sidewalk outside, Girl Scouts were selling cookies. In the tiny lobby, dozens of construction-paper stars were pinned up, each bearing the name of someone who donated money. Above the booth was hung a framed lobby card for It’s a Wonderful Life.

Thanks to Michelle Haugerud for all her cooperation and enthusiasm. Her informative JEM website starts here. The page devoted to the digital upgrade traces the fundraising process and records her gratitude to the community. , On the same page, scroll down to see a video of Paul running the last 35mm show. Michelle supplied the photo of Paul and Peter above. Many of my quotations come from news stories that are linked on the JEM site.

Statistics on the number of theatres and screens in the US come from the annual reports of the Motion Picture Association of America and from The NATO Encyclopedia of Exhibition. Patrick Corcoran of NATO kindly supplied me with further information.

During my time in Harmony, I couldn’t get access to much material about the JEM in the old days. According to The Film Daily Year Book, the original JEM Theatre (sometimes called the Gem) opened in the mid-1930s. It burned down in 1940. The building next door was renovated as the New JEM, which opened in September of that year. A plain-spoken house of 325 seats, it had fluorescent lighting, satin curtains, three layers of acoustic tile, and a big furnace for the cold months. Its estimated cost was $18,000. For the premiere, a four-page color brochure was printed and sent to 3000 homes in the area. The publication was “made possible thru the whole-hearted cooperation of the businessmen of Harmony who fully realize the value and convenience of this modern, good-looking theatre.” This information comes from “Harmony, Minnesota, Salutes New Jem Theatre, S. E. Minnesota’s Finest Showplace!” The Harmony News, flyer dated September 1940.

Three years later the JEM closed and became a bowling alley. It sat vacant from 1947 to 1961, when Bob and Hazel Johnson reopened it. For a fuller chronology, go to Michelle’s page on JEM history.

Michelle Haugerud and daughter Julia, 24 March 2012.

PS 1 April 2012 Marilyn Bratager writes with this correction about the source of the JEM’s name.

Relatives of mine were the original owners: Joseph Milford Rostvold and his wife, Emma. The J was for Joseph Sr. and Jr., the E for Emma and their daughter Elizabeth, and the M for the senior Joseph’s middle name, Milford, which was the name he was known by. There was a third child, Richard, but they didn’t use his initial as they didn’t want the theatre to be called JERM. 🙂

Thanks to Marilyn for the information!

Pandora’s digital box: Notes on NOCs

A video-wall display in the Christie Network Operations Center, Cypress, California.

DB here:

You’re in a multiplex. The pre-show attractions are large, loud promotions for TV shows, pop music, and star careers, interspersed with ads for men’s cologne and local pet-grooming facilities. Then comes the theatre chain itself telling you to hush up, turn off anything that emits light or sound, take your feet off the seats in front of you, and buy some popcorn. Next comes a barrage of trailers. Sooner or later the movie starts.

If you look back at the projection booth, will you see another human being? Not necessarily. It’s possible that everything that happens in your theatre is automated.

Now imagine another space, a large room with ranks of work stations. A couple of dozen people sit before their monitors, facing a video wall. From a room like this in Omaha, Nebraska, or in Cypress, California, or in Liège, Belgium, or in Shenzhen, China, these workers can remotely track thousands of theatre screens, including yours. It’s another consequence of the emergence of digital projection in our movie theatres.

Command and control

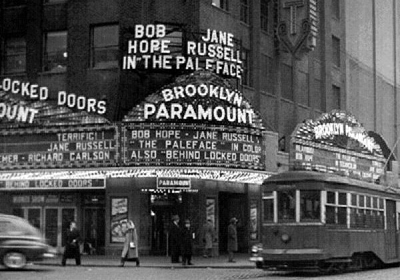

Brooklyn Paramount Theatre, 1948, from the splendor that is Cinema Treasures.

One of the many lessons you learn from Douglas Gomery’s magisterial history of the Hollywood studio system is straightforward. For about a hundred years, film producers and distributors have sought to control exhibition.

The advantages are obvious. Controlling exhibition keeps competitors off screens, it yields more or less assured revenues, and it allows vast economies of scale. If you can count on 2000-4000 screens playing your movie, as is common for Hollywood releases today, you can budget your production accordingly.

From the 1920s through the 1940s, studio control was quite direct. The Big Five companies (Paramount, Loew’s/MGM, 20th Century-Fox, Warner Bros., and RKO) wholly or partially owned hundreds of theatres, and these served as display cases for their product. Because no studio could supply all its theatre chains with films, studios shared their screens with their peers and kept other companies’ films out. “Here,” Gomery writes, “was a collusive oligopoly (control by a few) that operated as an almost pure monopoly.”

The studios didn’t own most of America’s theatres, just the most profitable ones. The thousands of independent houses and chains were subjected to studio control in more indirect ways. The studios forced the independents to book films in batches (“blocks”). To get prime releases, the exhibitors had to take weaker titles. Likewise, the independents had to bid for upcoming releases without being able to see them.

The structure of the market was another strategy of control. Adolph Zukor pioneered the system of runs, zones, and clearances. If people wanted to see a new release immediately, they had to pay top dollar at a first-run theatre. After a certain interval, the clearance, the movie would play a second run theatre in another territory at a lower price, and so on down the food chain of movie houses.

Technology was another strategy of control. The 35mm film standard wasn’t proprietary, but the sound systems that the studios adopted in the late 1920s were. Of the dozens of systems, only two became standardized: Western Electric and RCA. In a process similar to what’s happening today, theatres were forced to install one system or the other. The thousands of screens that couldn’t afford the new technology went dark.

This system worked to the Big Five’s benefit until 1948, when the Supreme Court declared Hollywood’s vertical integration monopolistic. The studios chose the wisest way to break up, given the slump in admissions: They divested themselves of their theatres and concentrated on production and distribution. (The process took several years in some cases, and there often remained close unofficial ties between the Majors and their former circuits.) In addition, block-booking and blind bidding were outlawed, so some market factors became more favorable to exhibitors.

The postwar studios occasionally tried to remake exhibition through new technology. CinemaScope, designed by 20th Century-Fox, sought to become the industry standard for widescreen presentation. Although there was considerable take-up, it had competition from other systems (notably Paramount’s VistaVision) and exhibitors were able to wring concessions from Fox. Centrally, exhibitors were reluctant to install magnetic stereo playback, and so Fox had to compromise by producing prints that could play on optical sound systems as well. Similarly, while various 70mm formats were tried, none became obligatory for exhibitors, since films released in 70 were also released in 35, if only in later runs.

Of course Hollywood still had a desirable product and could charge dearly for it, so stiff contracts for revenue returns gave studios considerable power. In the 1970s, the Majors (which no longer included RKO and had expanded to include Disney, Columbia, and Universal) found another way to use market dynamics to control exhibition. To publicize Jaws (1975), Universal launched massive television advertising and avoided the “platforming” or “exclusive engagement” practice. Studio chief Lew Wasserman opted for “saturation booking,” releasing Jaws on over 400 screens simultaneously. A month later it expanded to over 600.

The growth of the blockbuster, nurtured by Star Wars, Superman, and other huge hits, encouraged theatre chains to build multiplexes. The distributors could then blanket screens with their product. Exhibitors could realize economies of scale by holding over some movies for months while rotating regular releases through other screens.

With the arrival of cable, satellite transmission, and home video, studios were able to maintain tiers of price discrimination. The theatrical opening became the loss-leader, making less revenues but establishing buzz for the ancillary market. Theatrical runs were shortened considerably, but the “windows” of video distribution became the equivalent of second- and later runs. A movie becomes available on Pay Per View, then VOD and/or DVD, then premium cable, and so on. The windows’ length and ordering have changed over the years, but throughout, by carving up the market by price discrimination the studios continued to rule exhibition patterns.

My account makes recent history too neat, with studios apparently steamrollering unprotesting exhibitors. In fact, exhibitors have responded to some pressures by dragging their feet or pushing back. Better sound systems took some years to penetrate the market. Some big theatres refused to play Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace because of onerous terms, including a minimum guarantee and a commitment to a lengthy run in a ‘plex’s biggest auditorium. More recently, studios’ efforts to shorten windows and release films sooner on DVD or on VOD have sparked resistance.

Studios have periodically tried to become vertically integrated again. There were some attempts in the 1980s to run theatre circuits, but only Viacom has found success owning both Paramount and the National Amusements chain. Today, technology is providing a more effective lever–or rather a crowbar. Digital projection furnishes the most thoroughgoing opportunity for studio control over exhibition since the coming of sound, and perhaps since the days when the Majors owned movie houses.

NOC, NOC, who’s there?

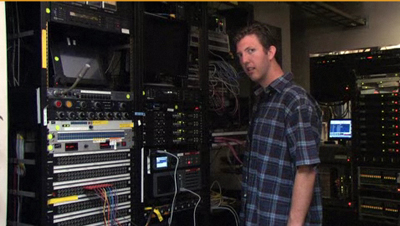

Christie Network Operations Center, Cypress, California.

My first entry in this series considered the power of setting standards, something Hollywood has been good at for decades. In 2005 the Majors established the technical specifications for the Digital Cinema Initiatives. As has happened throughout history, they had the input from the powerful manufacturers, service companies, and professional associations, like the SMPTE and the American Society of Cinematographers.

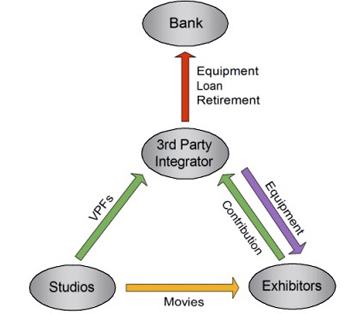

Once the standards were set, the projection and service suppliers could move forward with appropriate equipment. The conversion is expensive, so exhibitors have been offered the option of signing up for a Virtual Print Fee. This is a partial subsidy from the major companies that is passed through an “integrator,” a third-party company that attends to acquiring the equipment, installing it, and monitoring payback.

A decade ago, over a dozen significant US theatre chains filed for bankruptcy protection, so costs are constantly on exhibitors’ minds. Digital projection offered multiplex operators the opportunity to cut staff. Screening film prints is somewhat technical, and it relies on mechanical skills that are growing rare. So anything the manager can do to simplify running the show is welcome. Movies on digital files filled the bill. A film projectionist, represented by what was once one of the more powerful unions around, is expensive. Teenage labor is not.

Digital works for the fresh-faced novice. Once the film comes in on a hard drive, it’s not terribly hard to set up a show. Disney has made a couple of remarkable instructional films (here and here) for the new projector operator Jimmy, who wears the requisite Bob & Ted apparel.

In the old days, Walt would have given us a cartoon, and Goofy would have been the star.

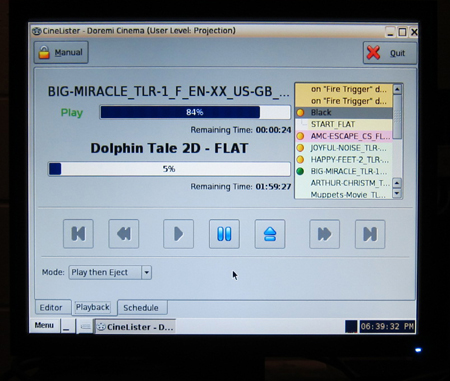

Jimmy loads the movies, and he or the manager sets up the programs. Once the features, the trailers, and the ads are on the servers or the library system, the theatre manager can program every screen. From a computer in the manager’s office, or almost anywhere, he or she can build each auditorium’s playlist by dragging and dropping. If the arrangements with the distributor permit, the files can be migrated from screen to screen.

Even under these conditions, though, you need minimal maintenance. Projector lamps must be changed, for instance. The installers or a local expert can supply routine maintenance, but sometimes there are problems. An encrypted file can’t be opened, or it’s corrupted, or the show mysteriously stops. Very likely Jimmy, even consulting his manual, can’t fix the problem.

Enter the NOC.

Network Operations Centers, also known as Data Centers, are part of broader Information Technology management. They’re used whenever a business or government agency has a network that needs 24/7 monitoring. All Fortune 1000 companies have NOCs, and probably have mirror backups of them scattered around the world. NOCs coordinate railway systems, military systems, banking, and police and fire departments. Amazon has a NOC in Seattle, Wal-Mart has one in Bentonville, Arkansas, and AT&T has a monstrous one in Bedminster, New Jersey (below).

There’s a nice gallery of NOCs here.

Don’t confuse NOCs with call centers or help lines. NOCs are handling and storing vast streams of data from computers, cameras, and other inputs. The goal is keeping track of things pertinent to the business or agency. But of course even large staffs can’t do this simply by eyeballing the flood of data. Instead, the software is set to notice anomalies and to call them to the attention of the humans. So if a police camera outside a Tube stop in London picks up a pattern of unusual activity, say three men running purposefully toward a woman, that information is pulled out of the stream and sent to an operator for inspection.

Once film theatres became digital, they acquired the ability to connect to NOCs via the Web. An owner who funded the purchase of the DCI-compliant equipment might well choose to pay a NOC to provide oversight and help. Exhibitors who sign up for a Virtual Print Fee program are required to sign up for a NOC. NOC services may be supplied by the equipment manufacturer (Sony, Christie’s, Barco, GDC et al.) or by the installer, such as Ballantyne Strong (Omaha) or Film-Tech Cinema Systems (Plano, Texas). An integrator may also offer NOC services, as Cinedigm does in the US and XDC does in Europe.

By the standards of giants like AT&T, a theatre-monitoring NOC tends to be fairly small, as my pictures indicate. Still, the purpose is the same. Each projector/ server combination and theatre-management system (essentially a master server) is connected via the internet to the NOC. The NOC monitors the state of the system, so that, for instance, it can keep track of lamp life, parts conditions, net connectivity, and the like. The software can send alerts to the theatre management for upcoming maintenance and can do troubleshooting. It’s also trained to notice problems—glitches in playback, lights going on, dropped subtitles, or whatever. Anomalies are called to the attention of the specialists at the work stations.

The projector manufacturer Christie’s initiated one of the first NOCs in 2003, and it now monitors over 3700 digital screens across the US and Canada. From its California facility it “manages the configuration of systems, provides help-desk services to customer staff, and access to local technicians with local parts to provide on-site repair and support.” The Shenzhen center maintained by GDC, a server company, monitors ten thousand screens. Most NOCs don’t plan programming or chase down encryption keys from distributors, but the NOC maintained by Film-Tech will perform these services as well. It will even power up and down the auditorium. With the Film-Tech system in place, says the company’s brochure, “The projection booth can literally operate for months without anyone ever entering it.”

The show must go on, if remotely

The projection area of the Studio Movie Grill City Centre, Houston, announced as the world’s first completely automated booth.

Now Jimmy and his manager have substantial support, but in turn they’ve shared a lot of information with the NOC. In order to collect the Virtual Print Fee, the exhibitor must play the studio’s film on a contractual basis—for a certain period, a certain number of times per day, and so on.

In earlier times, a dodgy exhibitor might run a film more frequently than was reported back to the distributor, with the exhibitor pocketing the difference. Or an exhibitor might trim shows of a poorly performing title, substituting something more popular and depriving the weak film of playing slots and box-office payback. In the pre-digital days, distributors sent out “checkers,” staff disguised as ordinary moviegoers, to see that theatres were running films according to the booking.

Now the projector/server mating provides real-time screening information to the NOC, and that flows to the distributor. Says an executive at a firm supplying NOC services:

All of the NOCs notify the studios about the performance of the systems. Uptime is critical or VPFs will not be paid. Exhibitors cannot miss more than a certain number of allotted shows and still receive their checks. . . . All NOCs provide the studios with access to the playback logs to ensure the movies booked are actually played.

According to the same source, some NOC systems monitor the use of the equipment outside normal shows. “Some of the traditional NOCs go so far as to ensure the equipment is not used for anything else, and the theatre will be back-charged for the use of that equipment.”

At a minimum, then, the performance information forces the exhibitor to abide by the booking contract. But it also means that even with full knowledge on the part of both exhibitor and distributor, the advantage lies with the distributor.

For example, if an exhibitor wants to play a film from outside the Majors, even if that film is available on a DCI-compliant file, that distributor has to pay a VPF. From the standpoint of the studios and the supply companies, he who pays the piper calls the tune: A DCI-compliant projector shouldn’t be used by free riders who didn’t participate in the DCI. Why should the Big Six establish the standard and fund the purchase and installation of the gear in order to play a competitor’s film? If the exhibitor dares to proceed without the VPF and uses the equipment to show unauthorized product, that information flows back to the NOC.

Consider as well the practice of “splitting.” Smaller theatres and art houses often adopt the multiplex tactic of offering many titles, but for them that entails showing two or more films on the same screen in a given day. Often splitting is done with the advance permission of the distributor, but sometimes it’s done ad hoc and reported after the fact (unlike the dodgy practice of show-shuffling I mentioned above). But VPF conditions may forbid splitting altogether. And if the exhibitor is obliged to do it, as when one movie file fails to run and another must replace it, the NOC will flag it.

Distributors allow a certain leeway for quality checks, running a film at odd hours to make sure it plays properly. Still, the NOC is tuned to those anomalies too. One exhibitor remarks, “If I’m demoing a movie, they may not know it’s a demo. They might wonder why I played a movie at 9:30 AM.”

In a highly automated environment, things can proceed blindly. There’s a story (not apocryphal, I think) about an early automated theatre system here in Madison, Wisconsin. During the 1970s, a snowstorm paralyzed the town, but someone at a theatre had left the system on. Even though the theatre was closed (and no one could get to it), the show went on: lights up, lights down, curtain parts, film runs, film halts, lights up, film rewinds….

More vaguely, some exhibitors worry about the NOC as a policing or surveillance operation. No one can object to a mechanism that enforces contracts, but film screenings have long had a certain fluidity, especially in the art-house realm. On-the-fly compromises and flexible arrangements emerged from negotiations among managers, programmers, bookers, and distribution staff. People knew one another and made allowances for specific circumstances. When so much of scheduling and operation is transferred to servers, playlists, and NOCs, human contact is likely to wane. The projectionist isn’t the only ghost haunting the multiplex.

Anyone who has ordered something with a credit card online has already submitted to the oversight of a NOC. But when your livelihood depends on smoothly functioning film screenings, you could be understandably apprehensive about turning your business over to unknown others in unknown places. Hacking, malware, and human error are spectres hovering over all of IT. As one theatre owner told me: “[The NOC] could shut off every theatre at one time and in the process send a little message, like the Jolly Roger in Independence Day when the guys bugged the mother ship.”

The studios innovated technology and had the power to set standards and restructure the flow of product. The multiplex exhibitors wanted to cut costs and simplify presentation. This meshing of interests allowed Hollywood studios to control exhibition to a new degree. Who wants to own theatres anyway? They entangle you in mortgages and real estate crises, and they have the awkward habit of going into bankruptcy. In addition, the Majors could win over local exhibitors by upcharging for 3D and by supplying ad packages that generate more income. Today if you control the files, the encryption, and the network, you control the show.

What’s left for the managers? Well, there’s selling popcorn.

This is the seventh in a series of entries on the conversion to digital projection in cinemas.

Thanks to Douglas Gomery, whose work on the American film industry has guided my thinking for the years going back to our teaching together at Madison in 1973. The place to start is his superb book The Hollywood Studio System: A History, which is complemented by his Shared Pleasures: A History of Movie Presentation in the United States. I’m grateful as well to those exhibitors and service specialists willing to share information with me, as well as to Jenn Jennings, who is making a film about the digital transition, and Jim Cortada of IBM and the Irvington Way Institute.

The Film-Tech Forum is an informative chatroom concerning projection and general film matters. Examples of NOCs in action have been provided in videos by Christie and XDC. In the latter, and true to European sophistication, our fashion-challenged Jimmy is replaced by a woman with bangs and a discreet nose ring. Yet like you and me, she likes a snack.

Pandora’s digital box: The last 35 picture show

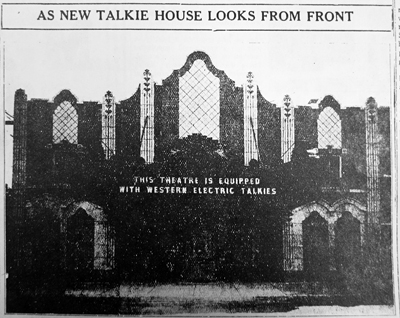

The Goetz and Goetz Junior Theatres, Monroe, Wisconsin, 1936.

DB here:

Eighty years ago the Goetz Theatre of Monroe, Wisconsin opened its doors. Last Sunday it screened the last 35mm prints it will ever show. On Tuesday, it became a digital cinema.

I sometimes find myself wishing I had been alive and sentient when exhibitors migrated from storefronts to dedicated venues in the 1910s, when they wired silent-movie venues for talkies (late 1920s-early 1930s), or when they converted to widescreen in the early 1950s. (For this last change, I was around but not sentient.) Think of all I could have learned about the stuff I study at a long remove now. Today I’m living through another time of technological upheaval, so I’m trying to catch up with it.

There are about 39,000 screens operating in the US, and about half are controlled by five major chains: Regal Entertainment Group, AMC Entertainment, Cinemark, Carmike, and Rave. Most of the screens are in population centers and are housed in multiplexes, which introduced economies of scale to the exhibition sector. Those economies make it relatively easy for the big chains to convert to digital. As a follow-up to my post on digital conversion at a local AMC multiplex (here), I wondered how the process affects a small-town exhibitor. After all, thousands of screens across the country belong to regional circuits or are mom-and-pop operations.

So I went to Monroe.

Local boys make good

Wisconsin is more than cheese and beer, but both have shaped the history of Monroe. The town grew in the 1890s with an influx of German-speaking Swiss immigrants, like those who founded the much smaller New Glarus. In the middle of farming country, Monroe became a center of signature Wisconsin commerce. It had the Joseph Huber Brewing Company, founded as the Bissinger brewery around 1845. It’s the home of the Berghoff line and other tasty beers. In 1926 an enterprising UW graduate modernized the town’s cheese industry by creating the Swiss Colony, a mail-order firm that offered cheese, sausage, and baked goods. The Swiss Colony still employs several thousand Monroe citizens and now holds a considerable portfolio of other brands.

While many small towns are shrinking, Monroe has had a steady population of about 10,000 since 1980. It’s a very pretty place, with a well-preserved town square centering on a towering Romanesque county courthouse. Elsewhere are some well-wrought Victorian homes. The town’s Swiss heritage is preserved in several restaurants, social clubs like Turner Hall, and civic events, notably the Cheese Days celebration.

Monroe had a succession of movie houses. Before 1920 there were the Nickelodeon, the Star, the Crystal, and the Lyric. Several of these were managed or owned by Leon Goetz, an early traveling film entrepreneur. He had run films in tent shows and town halls before settling in Monroe. In 1916 he opened the Monroe, the first movie house he built from scratch.

Leon Goetz was a risk-loving man. To build a 500-seat film theatre in a town with about 4500 people reflects not only the growing popularity of movies but a conviction that the business had a future. In addition, the many farms and little towns around would supply customers; Monroe is the county seat of Green County, so people came here to transact business as well as to shop. Then as now, the nearest competitors to a Monroe theatre were over twenty miles away.

Leon Goetz was a risk-loving man. To build a 500-seat film theatre in a town with about 4500 people reflects not only the growing popularity of movies but a conviction that the business had a future. In addition, the many farms and little towns around would supply customers; Monroe is the county seat of Green County, so people came here to transact business as well as to shop. Then as now, the nearest competitors to a Monroe theatre were over twenty miles away.

With his brother Chester as partner, Leon owned or managed other theatres in the area, including ones in Beloit and Janesville. The brothers’ biggest triumph, however, was building the Goetz Theatre. Opening on 2 September 1931, it was of semi-Moorish design, with faux balconies and moody cloud-and-star lighting on the ceiling. Light brown brick and darker brown terracotta inlays finished the outside. The lobby was forty feet high, with a gold finish and many trappings and fixtures.

Some unexpected innovations included seats equipped with earphones for the hard of hearing. The screen was 20 feet wide and fifteen feet tall. Accounts of the size range from 800 to 1000 seats. In all, the Goetz was said to have cost $125,000.

The Monroe had presented sound films using a system of Leon’s devising, but the Goetz was a step up, as the editors of the Monroe Evening Times indicated:

It should raise inestimably the respect with which talkies are looked upon locally and attract many persons who heretofore did not care to see pictures under the conditions in which they were shown.

The Goetz has run ever since. It’s said to be the oldest continuous family-operated movie house in the Midwest.

Leon retired to Florida but Chester stayed in the business, opening the Goetz Junior on Christmas day, 1936. It was “ultra modern,” as it advertised itself, with the Western Electric Mirrophonic sound system and using streamlined design elements, like glass brick. Holding only 275 seats, it sometimes showed films not screened at the Goetz across the street, but other times it would screen the same films–sometimes on the same night, with reels rushed back and forth.

Soon Chester had competition from the Chalet, a 500-seat house around the corner. According to local memory, Chester cut ticket prices and then bought the floundering Chalet as a third Goetz house. Chester’s sons Robert and Nathan joined the business. Under Robert’s leadership, their company built the Sky-Vu Drive-in in 1954, and it too has been running without interruption every summer.

The postwar decline in movie attendance may have hit the family’s circuit. The Chalet and the Goetz Junior closed. In the 1980s and 1990s two screens were added at the Goetz, but unlike most old theatres that went multi-screen, the venue wasn’t split up. The new houses were converted from adjacent retail spaces. Visit the Goetz today and you’ll see the original auditorium. There are fewer seats, but it’s still enormous, as you can see from the front.

The third generation

Robert “Duke” Goetz. Behind him, counterclockwise, pictures of Conrad Goetz, Nathan as a child, Robert as a child, young Chester, and John. In the center, Chester Goetz.

For many years the downtown theatre and the Sky-Vu have been managed by Robert “Duke” Goetz, Robert’s son. He has a masters degree in landscape architecture from Harvard, but he’s been running the family business. He does everything from programming the movies and designing the website to wrench-and-hammer work on the place. He’s worked on heating, carpentry, and acoustic matters. Talk with him and you’ll hear about the tough times small-town exhibitors have faced over the last two decades. I learned as well some pressures on exhibition that I never thought about.

Duke Goetz has a commitment to showmanship and quality of presentation. The Goetz website has old-fashioned razzle-dazzle, including neon colors. (Chester liked bright colors in his houses.) On another page of the site you’ll see this:

Last Friday I saw Duke tell a gaggle of teenagers to shut off their cell phones, and he watched to make sure they did. The same pursuit of a good movie experience shows in Duke’s special attention to sound. Convinced that DTS is the best sound system for his venues, he has outfitted his smaller auditoriums with hard-hitting speaker systems. He installed tip-back seats, stadium seating in one house, and one belt-driven projector for steadier images.

Despite the commitment to quality, and programming that brings in family fare matched to local tastes, business has been rocky. Duke recalls some high points: 1993, when Jurassic Park did spectacularly at both the Goetz and the Sky-Vu; 1998, when Titanic brought in as many as a thousand viewers a night; and 2002, his best year in recent memory. That year was an exceptional spike for the industry as a whole, with estimated admissions of 1.57 billion, so just about anything less looks like a decline. Kristin talks about this effect here.

Duke’s business stayed flat but solid until 2007, when both the drive-in and the downtown screen began to slump. Business flattened out at a lower level through 2011. The only bright spot this year was Twilight: Breaking Dawn; the midnight premiere drew about 150 customers, mostly high-schoolers.

A good night at all three indoor screens is 300-350 tickets, but the Sky-Vu can reliably draw many more. Duke recalls one evening when the drive-in had over 1100 customers and sold 114 handmade pizzas. Today, even with competition from another local drive-in, the Sky-Vu’s summer schedule bolsters the bottom line significantly.

Why the falling off in recent times? I had expected the standard macro-explanations: the internet, video games, etc. But Duke’s main rival, he believes, is sports. In a town like Monroe, high school sports are central to community life, so Friday night football and basketball games draw not only teens but parents. With the rise of women’s athletics, the middle and high schools schedule plenty of games across the weekend. Add in the fact that televised football in the fall breaks up Saturday (the UW Badgers) and Sunday afternoons (the Packers), and you have a client base that isn’t focused so much on movies. Even the Christmas-New Year corridor, normally a brisk business period, is likely not to help much this time. The New Year starts on a weekend, so that the Packers’ final game on Sunday and the Badgers in the Rose Bowl on holiday Monday will compete with Duke’s screenings.

After three tough years, Duke looks at things realistically. He hires part-time staff to project, sell concessions, and keep an eye on the house, so he’s his only full-time employee. He adds: “I have not been paid since August 2010.” Digital, he admits, is chancy in this business climate. “But without digital, I’m gone.”

Duke goes digital

Duke Goetz saw his first digital screening around 2000 at a convention of the National Association of Theatre Owners (NATO). What attracted him was the edge-to-edge screen brightness. Judging by what I saw on Friday (from down front), the 1.85 image in 35mm at the Goetz is quite sharp, but Duke had long been unhappy with the inevitable falling-off of light toward the edges of any film display. The tendency is exaggerated in anamorphic (2.40) films, which have become more common. And the bigger the screen, the greater the tendency toward a hot spot in the center. In addition, Duke liked the punchier color in digital.

So he was intrigued. “I’d have loved to have done it ten years ago.” But then there was still debate about trustworthy delivery systems (the Net? satellite?) and the cost was astronomical, about $125,000 per projector. Last summer, though, it became clear that the digital wave was cresting, and time was running out for 35mm film. Also running out were the plans for the Virtual Print Fee, whereby the studios partially subsidize the cost of a theatre’s changeover.

This fall Duke took the plunge, arranging for three new NEC projectors from companies and installers he’s known for years. His final analog shows were last weekend. On Monday all houses were closed. By Tuesday night, the Goetz was running a digital copy of New Year’s Eve, which it had run in 35mm only a couple days before. By this coming weekend, all the digital screens are expected to be in action. Duke isn’t going with 3D, partly because he can’t justify the upcharge and partly because he’s not convinced it attracts enough extra business.

I was there for the Friday night 35 shows, and I re-visited on Tuesday. The whole changeover was less dramatic than I expected. In two of the houses, the old projectors were simply moved aside and the new ones sat stolidly in their place.

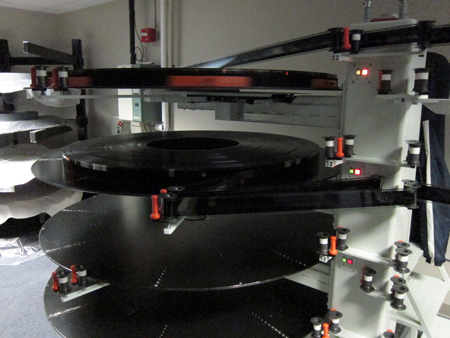

The gigantic platters were stacked in the hallway.

Reels, rewinds, and splicers sat in corners. All of the 35mm projectors were relatively new, but now one is now in the lobby as a historical artifact.

Duke thinks that digital will be even better for the Sky-Vu. The big screen is a problem for dimness and edge-to-edge brightness, but it should respond well to a digital beam. An indoor screen is porous to allow sound through, but that means that some light is lost. A drive-in screen is solid and should reflect light better. The brilliance of the digital illumination should also help counter chronic drive-in problems like fog, ambient light, moonlit nights, and some flaws on the screen.

The Goetz attendance flattening is part of a larger trend. The box office of 2011 has been weak, and for several years the total domestic admissions have hovered between 1.3 and 1.5 billion. Box office takings are up chiefly because of raised ticket prices, particularly for 3D and Imax. Professional predictors are suggesting that this year’s ticket sales will end up about the same as last year’s.

It would be easy for us cinephiles to bemoan what happened between Sunday and Tuesday in Monroe, Wisconsin. We celebrate the look and feel of film, and we’d like to see old picture palaces become temples dedicated to 35mm. But we don’t pay the shipping and heating bills for those houses; we don’t dicker with bookers who won’t let us have prints when we need them. We like the idea of film surviving, but the practical people who actually deal with exhibition day by day can’t afford to satisfy our tastes.

And we purists would doubtless be scandalized at what film prints looked like when they made their way to the Goetz in the old days, six months or more after release. The Goetz Junior opened with Eddie Cantor’s Strike Me Pink nearly a year after it premiered in Manhattan. In April 1956 the Chalet was running a 1951 Roy Rogers movie. Take a time machine back to the 30s or 40s or 50s and you’ll probably watch a choppy, scratchy print. In comparison digital starts to look pretty good.

I’d like to see Duke succeed. Monroe’s theatre reminds me of the single screen of my childhood, Schine’s Elmwood in Penn Yan, New York. That theatre is long gone, so part of me hopes that somewhere a local movie house can still bring in the community–whether it’s showing film, 2K, Blu-ray, or vanilla DVD. When I was a boy, I wouldn’t have cared how those images got on the screen. In a town like Monroe, the theatre, and the neighborly spirit it represents, is as important as the emulsion. One item of evidence is my 1936 photo up top, taken from the Goetz website. Down past the Hollywood Inn, which I wish I could visit now, maybe you can make out the Goetz marquee: TODAY 2 BIG FEATURES IN GERMAN.

Duke closed out his 35mm shows on the worst weekend exhibitors had seen since fall 2008. Will digital bring Monroe area customers back? Once people realize that they will get high-quality presentation in their home town, perhaps they won’t drive half an hour to Freeport or an hour to Madison. But best not to prophesy. Duke realizes he’s taking the same sort of risk that Leon and Chester took when they built the Goetz at a price of what would be $1.7 million today. “My motto,” he says, “is go digital or die.”

This is the second in a series of entries on the conversion of filmmaking, distribution, and exhibition to digital formats.

Leon Goetz is also credited with producing at least two films, Ten Nights in a Bar Room (1931) and The Call of the Rockies (1931).

I thank Duke Goetz and Mrs. Robert Goetz for talking with me about the past and present of the family business. Other information comes from volumes of The Film Daily Yearbook and issues of The Monroe Evening Times of 1 September 1931; 23 December 1956; 22 October 1981; and 15 May 2001. Also very helpful was Pictorial History of Monroe, Wisconsin, ed. Matthew L. Figi (Green County Historical Society, 2006), supplemented by some discussion with Matt. Thanks also to the staff of the Monroe Public Library.

For better versions of the picture at the top of this entry and the frontal view further down, along with other high-quality images, go to the historical page of the Goetz Theatres site. A chronology of the Goetz Theatres is on this page, and some shots inside the booths at the Goetz 2 and 3 are here.

P.S. 15 December: Thanks again to Matt Figli, who spotted some inaccuracies in my account of Monroe’s history. They have been corrected.

P.P.S. 28 December: Katjusa Cisar’s story in The Monroe Times today brings us more information on the Goetz, both past and present.

Pandora’s digital box: In the multiplex

Advertisement for NEC digital projectors, Variety July 2005.

ELECTRONIC CINEMA IN THE WINGS

Not only will [HDTV] usher in a new era of dramatically enhanced sharper-picture, improved color, wide-screen, stereophonic home TV, but HDTV will give rise to what’s already being called “electronic cinema”—high-definition video used to make 35mm quality theatrical feature films.–Variety, January 1982

FAROUDJA TOUTS VIDEO FOR BIGSCREEN

Faroudja and Videac seek to demonstrate that today’s technology makes it quite possible to display video images in a theatrical environment of a quality that can stand comparison with 35mm film. —Variety, June 1989

DIGITAL TECH POINTS TO PIX’ FUTURE

In the midst of a digital revolution that is embracing television, cable, and telephones, the movies certainly aren’t immune. Appearing soon in a theater near you will likely not be film at all but a digital projection that looks like the real thing. —Variety, May 1992

DIGITAL CINEMA HOVERS ON HI-TECH HORIZON

“I really do think at least a couple of the major players are pretty close.”–Variety, June 1995

WHEN PRINTS WILL NO LONGER BE KING

While the eventual replacement of 35mm projectors by video systems was seen as an inevitability—and a welcome one, at that—most agreed it was still far in the future. But after seeing six state-of-the-art systems beam images onto a 40-foot-long screen at the United Artists Denver Pavilions complex, many attendees agreed that the future is already upon us. — Variety, January 1999

Aug. 15, 2004: Using his computer keyboard and mouse, the president of top U.S. theater chain Regal/ Loews-AMC books the upcoming weekend’s films into his circuit’s theaters.

As he clicks on the titles (“Austin Powers 4: You Only Shag Twice,” “The Matrix III,” and MGM’s long-awaited “Supernova”) the films begin downloading via satellite to the circuit’s digital megaplexes around the globe. —Variety, August 1999

DIGITAL CINEMA’S PICTURE STARTS TO FADE

A few years ago, cinema operators were open-minded, but not any more. Now it’s clear that the first-generation digital projectors—brand-spanking-new equipment installed in 116 screens worldwide, out of an estimated 108,000 cinema screens globally—is rapidly becoming obsolete. — Variety Deal Memo, July 2002

AT LONG LAST, DIGITAL THEATERS

Finally. Digital cinema is here. No, really. . . . The conversion of of 35,000 US screens to digital projection can begin in earnest.

. . . . All six “Star Wars” films will be converted for 3-D re-release, perhaps as soon as 2007. —Variety, July 2005

DB here:

Reading things like this over the last couple of decades, I smiled patronizingly. The shift to digital, hyped from the start, sounded both inevitable and impossible. Even the ad for NEC at the top didn’t faze me. I’ve seen braggadocio before.

In my smugness I forgot that most broad changes take a long time to be consummated. Historian Jim Cortada writes that a new technology may wait as long as forty years before an industry decides to adopt it. I should have remembered that in cinema many hardware changes, such as color movies, took a surprisingly long time to become dominant.

Now everybody has woken up. We realize that we’ve crossed a threshold. Henceforth digital projection will be the norm.

Some numbers back up the impression. In December 2000 the world had 30 commercial digital cinema screens. In 2005 it had 848. At the end of 2010 it had 36,103—about thirty per cent of the total 123,067 screens. In North America, the jump was dramatic, from about 330 d-screens at the end of 2005 to over 16,000 at the end of 2010.

This year has iced the cake. In the UK, 80 % of releases were digital. At Cannes there were a great many digital screenings, even of films shot in 35mm. In Belgium the two major theatre chains, Kinepolis and UGC, went wholly digital. In Norway all 420 commercial screens were converted, partly because the government funded the changeover. Closer to home, the dominant chain in our region, Marcus Cinemas, went digital and fired its projectionists—ironically, just before Labor Day. My local theatres are junking their 35mm equipment. Roger Ebert recently posted a letter from Twentieth Century Fox announcing that “within a year or two” it won’t be sending out film prints.

Given all this, the newest predictions don’t look as Pollyannaish as the ones I listed up top. “Some time in 2013,” says a spokesman for the National Association of Theatre Owners, “all the [U. S.] screens will be digital.” Next year, half the screens in the world are likely to be. By 2015, predicts IHS Screen Digest, film-based projection will be defunct in commercial cinemas.

I’m not smirking now. Digital cinema is here.

The booth

“Here,” of course, is a place still in transition. I saw that back in September when I paid a visit to my local, an AMC multiplex in Fitchburg, Wisconsin. Its projection booth, a vast tunnel running almost the breadth of the building, reflected the changes in progress. Several 35mm projectors were still humming away, pulling the film from one big platter to another. There were some digital projectors too, one being the Sony SRX-R320.

You’ll notice the two lens housings on the right, suited to 3-D. Using these lenses for screening 2D films is a bone of contention in the current controversy about digital projection. (See the codicil for this entry.)

There was one Christie digital projector, run both from a computer and a touch-screen.

The heart of the system is the Digital Cinema Package (DCP), shown above. It’s a cute item, a little taller and skinnier than a trade paperback. It comes in a bright red carrying case padded with pink foam. Essentially, it’s a hard drive containing files for the image, sound, and subtitles, as well as files for playback, security, and encryption. The film is compressed; an hour-long movie at the maximum rate would take up about 115GB on a DCP. Trailers and specialized content, like Met Opera shows, come on their own DCPs.

The DCP files have to be opened, with password keys supplied by the distributor. The files are then loaded into either a projector or a server in the booth. Loading can take several hours. A projector like the Sony can hold half a dozen or more features. Since the projectors are essentially big computers, the features, trailers, ads, and the like have to be arranged in a playlist, accessed by either a touchscreen, a laptop, or both.

The fear of piracy has kept back one early aim of the digital cinema revolution: Delivery of content via satellite or the Net. These are apparently too vulnerable to hacking or crashing. So the DCP is delivered the old-fashioned way, by courier services like UPS and FedEx. The decryption keys are sent by email or by a much older technology: the telephone. Often exhibitors and projectionists—sorry, Mr. or Ms. Screen Management System—has to phone somebody to learn the codes to tap in.

Turning points before the tipping point

The digital switchover seems sudden, but like most historical change there’s a story to tell about it. The digital changeover in movie houses was delayed by many factors, but the problems were solved, as usually happens when there’s money to be made and people are in the grip of the next big thing.

Here are four factors that, to my mind now, made the difference. They didn’t crop up in neat sequence, but they developed in an intertwined fashion before gathering in a knot in the last year or two.

1. The setting of standards

Standards are of immense value to the film industry. It’s to everybody’s interest to have movies run at the same rate, but if you think you can improve on 24 frames per second (sometimes 25 in Europe), you will have a long climb. (Doug Trumbull and Dean Goodhill have found this in arguing for higher frame rates.) Technological change in Hollywood consists chiefly of the Majors cooperating with each other to mutual benefit, while setting up barriers to entry that exclude outsiders.

For the most part, standards in film have been set not by trade associations or government agencies but by the major players: the technology suppliers and the studios. Innovations in sound, picture, color, and widescreen tended not to come from within the filmmaking companies but from outside firms and lone inventors, eventually to be accepted by the majors. Only then do the trade associations and other institutions get into the act.

The standards are often in flux, constantly adjusted to practical concerns. What, for instance, is the CinemaScope aspect ratio? Designed originally to be 2.66:1, twice as wide as the 1.33 format, it went to 2.55 and then to 2.35, partly because of Twentieth Century-Fox’s responses to the market. Later that standard was modified again, to 2.40. The Society of Motion Picture Engineers, which has historically tried to stabilize the technical standards, often played catch-up, refining or revising standards that were already common practice on the ground.

The real momentum for standardization comes when the American film studios, as an oligopoly, decide to throw their weight behind an innovation. This is what happened with the DVD and the Blu-ray disc (and may happen with higher frame rates for digital). Once the decision-makers have surveyed the range of options out there, usually offered by very big technology companies, there ensues a process of negotiation, testing, and horse-trading before a standard is arrived at. And even then the standards might be pretty flexible.

For digital projection, the oligopoly’s concerted effort began in 2002, when the six major studios formed a joint venture, the Digital Cinema Initiatives, LLC. As the studios in the 1920s had recruited the American Society of Cinematographers to test incandescent lighting systems, so they now had the ASC create material for testing digital projectors. The DCI also hired universities and private agencies to test the systems. Some interim documents proposed requirements, and the full set of specifications was issued in July 2005. This 161-page document has been revised, but it remains the bedrock for any manufacturer, theatre chain, or projectionist (defined in the text as part of the “Screen Management System. . . the human interface for the Digital Cinema System”).

![]() The original document, available here, is a mind-boggler for anybody not familiar with the engineering of digital systems. It specifies image qualities, audio characteristics, metadata, encryption, and security parameters. Here’s a sample from the nineteen tasks assigned to the Security Manager (SM)—again, not a person but a program:

The original document, available here, is a mind-boggler for anybody not familiar with the engineering of digital systems. It specifies image qualities, audio characteristics, metadata, encryption, and security parameters. Here’s a sample from the nineteen tasks assigned to the Security Manager (SM)—again, not a person but a program:

Secure Processing Block behavior and suite implementations shall permit the SM to prevent or terminate playback upon the occurrence of a suite SPB substitution or addition since the previous suite authentication and/or ITM status query. The SMs shall respond to such a change by immediately purging all content and link encryption keys, terminating and re-establishing: a) TLS sessions (and reauthenticating the suite), and b) suite playability conditions (KDM prerequisites, SPB queries and key loads). “Prepsuite” command(s) shall be issued per (9) prior to the next playback.

This is a far cry from what projectionists and theatre managers have traditionally known how to do. The opacity of the DCI specs may have the effect of disempowering traditional film workers and shifting their responsibility to the maintenance manager working for the manufacturer or some other third party. In any case, as had happened with sound and widescreen systems, the American film companies set the standards for the world.

The publication of the DCI report led to the exuberance in my last quotation at the start. With this in place, surely digital cinema had arrived in 2005 (along with the imminent release of all six installments of Star Wars in 3D). Yet a report last March found that most projectors currently in use weren’t fully DCI compliant; Sony and other companies came up with fully compliant equipment only this year. So thousands of projection systems were in operation outside the DCI standard, working under the rubric of “interoperability.” As usual in the film industry, practical demands outpaced standardization. 2011’s new lines of projectors from major providers are DCI compliant, which should attract exhibitors who were hanging back to see how all this got sorted out.

2. Convergence of hardware

A key condition laid down by the DCI was a requirement that digital exhibition be 2K or 4K resolution. That eliminated some systems outright, notably the unsatisfactory 1.3K format that had had some take-up in the US and had proliferated in foreign markets such as India (and are still flourishing there under the name of “e-cinema”). 1.3K systems were in the majority until 2005.

For 2K or 4K projection, Texas Instruments had already developed its Digital Light Processing system, consisting of thousands of microscopic mirrors, and this was adopted by three major manufacturers: Christie, Barco, and NEC. Sony developed its own system using modified LCD technology, claiming that only that can do justice to 4K projection. These four companies dominate the digital theatre market. All were producing machines in numerous models by the end of the 2000s.

China and Russia, both growing markets, proved particularly important, as their newly built theatres skipped 35mm altogether. The expanding markets gave the companies vast quantities of business; Christie reported that over 600 sites in Asia installed its projectors in 2009, while Barco claimed that it had 80 % of all installed screens in China. In Russia, of the 297 new screens added in 2010, 256 were digital. This surge from the periphery gave impetus to the US changeover as well, as brisk sales permitted the manufacturers to refine their systems and hatch new models.

3. The Virtual Print Fee

Historically, exhibition has been the most conservative wing of the film business. The theatre owner has the most to lose if a new technology fails to catch on. It was theatre chains’ reluctance to install magnetic-stereo sound systems that led Twentieth Century-Fox to redefine CinemaScope to 2.35, lopping off some picture area to make room for an optical soundtrack that would play on existing projectors.

It’s expensive to retool a movie house for digital conversion. Each projector can run up to $100,000, and you need a server as well. In addition, the costs of maintenance are higher for digital; theatre owners initially claimed that they’d need up to $10,000 annually per auditorium.

It’s expensive to retool a movie house for digital conversion. Each projector can run up to $100,000, and you need a server as well. In addition, the costs of maintenance are higher for digital; theatre owners initially claimed that they’d need up to $10,000 annually per auditorium.

The big three theatre chains in the US—AMC, Regal Entertainment, and Cinemark—control about 20,000 of the country’s 39,500 screens, and they were reluctant to embrace a technology that could cost them a couple of billion or more. If these dominant exhibitors wouldn’t jump in, no smaller circuits would convert. Moreover, the studios preferred a quick conversion. Distributing both 35mm and digital versions was costlier than either one alone.

The solution was the Virtual Print Fee. Five studios agreed to help the big three finance the cost of conversion, to the tune of $1 billion. The VPF is a subsidy paid by the distributor. Under one common arrangement, it’s collected by an intermediary, known as a third-party integrator; the dominant integrators in the US have been DCIP and Cinedigm. The integrator loans the digital equipment to the theatre. For each booking the exhibitor makes, the film’s distributor gives a sum to the integrator (negotiable, but said in 2005 to be $1000 or so). But the VFP doesn’t cover the entire cost; the exhibitor has to chip in. Eventually the equipment is paid off and belongs to the exhibitor. (The accompanying diagram is taken from the informative site hosted by MKPE Consulting LLC.)

To speed up wide installation, most VPFs were set to expire at the end of 2012, although some are likely to be renewed or extended. Recently, Christie’s has initiated a VPF program aimed at independent exhibitors. Europe and Asia have VPFs and integrator go-betweens as well.

Most observers credit the VPF policy as a principal cause of speedier digital conversion, but there was another factor at work.

4. The killer app, 3D

The studios’ concerted offer of a Virtual Print Fee occurred in October of 2008, just as the world economy was heading down the drain. Credit was tight, and the rate of digital conversion was slowing. 3D came along at the right moment. Exhibitors learned that there was a line-up of big 3D films for 2009, all from the studios offering the VPF. A theatre that wasn’t set up for digital couldn’t play these titles.

Chicken Little (2005) showed the way, and in the following years a few films gave other promising results (Monster House, 2006; Meet the Robinsons, 2007). Concert films, especially Hannah Montana (2008), helped too. But Monsters vs. Aliens (2009), which played Imax houses as well as normal 3D ones, was a turning point: it grossed nearly $60 million in the US over its first weekend, more than half coming from 3D screens. The studios stepped up their production of 3D titles, from five in 2008 to eleven for 2009 and over twenty in 2010. Exhibitors saw that they could charge between $2 and $5 more for a 3D ticket, and this boost could help defray the costs of converting to digital presentation. Avatar seemed to seal the deal; it became the top-grossing film of all time (in absolute, not relative dollars), and after 47 days, over 80% of its $2.075 billion gross had come from 3D screenings.

This year sees over thirty 3D releases. Kristin has pointed out that the calculations of 3D’s value to the box-office may be off-base. Still, the 3D initiative worked as a wedge prying open reluctant multiplexes. There are now over 22,000 3D screens worldwide, and in 2010, they yielded $6.1 billion in grosses–more than twice the 2009 figure. Hollywood should give Jeffrey Katzenberg (right) a medal for his insistence that this format was the wave of the future. Even if it’s not that, it was the Trojan Horse for digital projection.

This year sees over thirty 3D releases. Kristin has pointed out that the calculations of 3D’s value to the box-office may be off-base. Still, the 3D initiative worked as a wedge prying open reluctant multiplexes. There are now over 22,000 3D screens worldwide, and in 2010, they yielded $6.1 billion in grosses–more than twice the 2009 figure. Hollywood should give Jeffrey Katzenberg (right) a medal for his insistence that this format was the wave of the future. Even if it’s not that, it was the Trojan Horse for digital projection.

I haven’t touched on other forces working in favor of digital theatres. Exhibitors were surely happy to embrace an automated system that would allow them to dismiss expensive unionized workers. Digital projection also opened up the possibility of using a venue for “alternative content”–pop concerts, opera broadcasts, sports events, and business meetings with snazzy presentations. Distributors gained as well. Besides saving money on prints and shipping—the public rationale for the switch—distributors could now monitor the number of screenings at any venue. A DCP-wrapped feature is set for only a certain number of runs. To extend the number of screenings, the exhibitor needs a new key code. This prevents off-hours screenings, a common practice of old-school projectionists. In addition, distributors suspected projectionists of video-recording prints or bicycling them for overnight telecine copying. (After Web 2.0, however, prime sources of bootleg copies have been workers in the industry itself.)

The past regained

Historians shouldn’t predict. I succumb sometimes, but I always regret it later.

Even professional predictors shouldn’t predict, as we see from a 2002 Credit Suisse First Boston report on digital cinema. That document declared that Eastman Kodak was the technological “winner” and would benefit from its “sensible business plan.” The report added that Kodak’s film business should face “minimal deterioration” from digital cinema. They valued Kodak’s Entertainment Imaging branch at $2 billion. Today Kodak’s entire company is valued at $900 million and its stock trades at $1.10 per share, down from the $30s in 2002.

So, no predictions from me. But warnings and worries? Yes, quite a few. Next time I’ll share some concerns about festivals, repertory cinemas, arthouses, colleges and community centers who depend on 35mm prints—especially older titles, our link to the history of the medium. Eventually we’ll get to archives, the repository of said history. I hope as well to offer some general thoughts about the redefinition of “film” in the high-def era.

In the meantime, let’s remember what was.

Alongside the 35mm and digital houses at the AMC Star Fitchburg 18 stands a very good Imax facility. If the digital gear shows us the present and future, I had the feeling that the monstrous Imax 3D projector, devouring two huge reels of 70mm film at the same time, was the world’s last movie machine.

Two fat ribbons, destined to intersect for an instant, whir past you, zigzagging around rollers, turning the room into a web of film. A pair of images snap into the gate. Each is sprayed with a puff of air. You must keep the film and lens clean; even a speck of dust looks like Rodan on the Imax screen.

Holding 35mm film in your hand is a pleasure, but 70mm is almost menacing. Even with 35mm, you need a loupe to see detail, but 70mm just boldly shows you everything, bright and crystalline.

The intimidating image suits the hardware that runs it. In the Imax 3D film projector, you see that mixture of enormity and delicacy, thrusting energy and exquisite precision, that characterized mass printing, tool-and-dye, and the rest of good old US industry since the nineteenth century. The whole contraption looks like a giant doing needlepoint. Yes, the sound system is digital, but you couldn’t find a more stubbornly old-fashioned way to display pictures—themselves big, palpable, and gorgeous. It puts you in mind of sledgehammers and nuts: All this just to show a movie? By all means.

This is the first of a series of entries reflecting on digital cinema.