Archive for the 'Movie theatres' Category

Down in front! Notes from the Raccoon Lodge

O Brother, Where Art Thou?

There is one hypothesis that I find interesting because it is so minimal, yet sufficient. This is that nobody cares where he sits, as long as it’s not in the very front.

—Thomas Schelling, 1978

DB here:

Where do you like to sit in a movie theatre? If you’re like most people, you sit fairly far back, maybe all the way in the back row.

Sitting in the rear is the default for public gatherings, it seems. Thomas Schelling famously offered seven hypotheses about why people don’t fill up the front of an auditorium as fast as they fill up the back. His reflections were occasioned by his giving a lecture to 800 people, none of whom would sit in the first dozen rows. I know the feeling, though on a smaller scale. Seeing all your audience huddled so far away, you suspect you have cooties.

Schelling didn’t, so far as I can tell, offer a definitive answer, and his charitable reflections on people’s motives don’t keep me from finding the migration to the rear disquieting. In lectures, those distant auditors send off an air of foreboding. They seem poised to flee at the moment the talk reveals its fully catastrophic dimensions.

There’s a debate about whether students who sit in the rear get worse grades than those who sit close. (See below.) Speaking from experience, I’d be inclined to say that professors tend to give better grades to students sitting close because those distant, blurred ranks tend to give off an aura of desperate yearning to be anywhere but there. The folks up front at least seem to be trying to be part of things. The back-row brigade have not learned the great lesson of social life: Feign interest.

As this lead-in suggests, I’m a front-zone sitter. But that predilection comes at a cost.

Rebel without a Cause.

For lectures I always try to get a front-row seat, close to the speaker if possible, or centered if there’s to be a big visual presentation. This vantage point is great. If there’s flop sweat, you see it. If not, you get to enjoy consummate performance up close. I’ve sat in the front row for fine speakers like Chomsky, Pinker, and Bruner (to stay just with the Boston brain trust).

When a filmmaker does a Q & A, the front row is a must: you get a good chance at an autograph. The only time I regretted my prime front seat for a live event was for a concert—a John Zorn one. Within five minutes I expected my eardrums to bleed. After that overture I don’t think I heard anything else.

I saw back-row bias in the movies demonstrated dramatically in Madrid, where Tom Gunning and I went to a movie together. I forget the name of the theatre, but the film was Welcome to Veraz (1991), a Euroduction featuring, inevitably, Richard Bohringer and, less predictably, Kirk Douglas. Once we got inside, we found that our tickets were for specific seats. The cashier had assigned us, and all other patrons, to the same row—in the back, naturally. The absurdity of a dozen of us sitting side by side in a vast theatre was lost on the staff. Tom and I moved to the front, but everybody else piously stayed in the same pew.

You can study a less extreme case in graphic form in those remaining venues, mostly European and Asian, that still ask you to choose your seat on a chart. A glance shows you that everyone has piled into retreat mode, leaving lots of nice seats for you. Problem is, those overhead diagrams of the venue aren’t to scale, and so you don’t really know how close you are to the screen when you’re picking your seat.

When you were little, you didn’t mind sitting up by the screen. You sometimes fought to do it. But as we age, we seem to gravitate toward the rear. We’re even told that we should sit a prescribed distance back, usually the dead center of the auditorium. A distance of 2-3 times the screen height is a common recommendation. But Kristin and I are front-zone people. Speaking for myself, I like scanning the frame in great saccadic sweeps and even sometimes turning my head to follow the action. CinemaScope and Cinerama give your eyeballs a real workout.

I know that most people find this sheer madness. When the picture comes looming up, you do feel a little disconcerted and overwhelmed. But I find that I adapt in a minute or two. Even the keystoned angle isn’t a problem, partly because of our old friend perceptual constancy.

Note that I said front-zone. Not every theatre favors front-row sitting. Kristin and I once went to a screening of An Autumn Afternoon in a tiny Parisian house, one of those that seem to have been carved out of a loading dock. We sat in the front row, but that was a mistake. We could put our feet up against the wall housing the screen, and we reckon we watched the movie at something like a 45-degree angle.

Something a little more peculiar happened when we went to a Fan Preview of Scott Pilgrim vs. the World. Firmly ensconced front and center, we were packed in by comic geeks, nerds, dorks, wonks and other damned souls, all determined to enjoy this movie. So we had the strange experience of hearing a line of dialogue and then, because its eloquence had a rich bouquet, hearing yelps of appreciation rolling back behind us, as row after row (a) heard it, (b) laughed, and (c) did an instant commentary on it. I can’t judge this movie objectively to this day.

So sometimes the front row isn’t ideal. Through experience, we know our local venues and favorite festival sites. In some theatres, such as most of our local Sundance screens, we sit 2-5 rows back, with C being a common choice. Still, the ticket seller usually does a double take and reminds us where the screen is. Then we get a shrug and something on the order of “Well, you won’t be crowded down there.”

Bologna Cinema Ritrovato 2008: Olaf Möller, Jonathan Rosenbaum, Don Crafton, Haden Guest, Kristin Thompson.

But in many venues the front row is perfect. Sitting there is hard-core moviegoing. I started aiming for it about forty years ago, when I began taking notes on every film I saw. If you sit too far back, how can you see your pad? You can’t be one of those idiots brandishing a lightbulb pen (even though I have some of those). The screen casts a little light that makes scribbling easier.

But even those who don’t write notes see the advantage of the front row. Nobody’s head looms in front of you. You’re less disturbed by latecomers. You have more leg room, and it’s easier to stretch out for a snooze. And should you wish to leave, the front row is the only one that lets you sneak out easily from any seat.

That last advantage, I should mention, can lead to trouble. Once at VIFF I was firmly planted in the front row, nose in book, as the auditorium filled. But I began to realize that these didn’t seem to be my tribe. There were more beards, nicer clothes, better hygiene, more sensitive faces. The place filled, and someone came forward to thank the sponsors for bringing a film about the efforts to save remote wetlands. I was in the wrong auditorium. To glares and mocking comments I slunk out in search of some obscure art movie I’ve forgotten.

Like everything else you do, front-row sitting sends a message. What message? For one thing, that signal of interest I mentioned in my classroom example. Somehow the front-row sitter seems to be more engaged, more eager to be swept up in the magic. You probably know the urban legend that the Cahiers du cinéma writers sat devoutly in the front row at Langlois’ Cinémathèque. We belong to a noble tradition, and we flaunt it. Chevaliers of cinéphilie, we risk eyestrain, neckache, back pain, and leg cramps for the art of cinema, or so we like to think.

Speaking of the Cinémathèque, back in 1970 I went to the Chaillot venue for a screening of Liebelei, to be attended by Luise Ullrich, one of the principal players. The place was full, but I had nabbed a nice spot up front. Before the film started, though, a Cinémathèque functionary started going along the front row asking every patron there a question. Everyone asked said no. I couldn’t hear the question at a distance, and perhaps might not have understood it if I had. So when the staff member came to me, I scarcely let him finish before declining. If non was good enough for other front-row denizens, it was good enough for me.

After the lights came down, Henri Langlois stepped onstage with Mme Ulrich. After a brief introduction, they descended. Only then did two people on the aisle surrender their seats for them. Then I realized all the French guys sharing the front row with me wouldn’t give up their seats even for the guest and the boss of it all. You see why I say front-row people are hard-core?

Le Pied qui étreint 1: Le Micro bafouilleur sans fil (1916).

I must report, however, that front-row sitting sends other signals too. Theatres in film archives have their regulars, and these folks, like me, believe that there’s only one good seat in any theatre, and they must occupy it. Fortunately, they mostly don’t agree on what that seat is. I’m always befuddled when the first person in the queue makes a dive for a seat far back and in the corner.

Alas, though, so many regulars have aimed at my target that every cinematheque has a coterie of front-row fans. And they’re perceived as, well, strange. I remember going to London’s National Film Theatre during a visit and getting in early enough to nab a prime front seat. Many regulars shuffled in to join me, and one seemed a bit miffed after the rank had filled. My neighbor told me apologetically that I was sitting in his friend’s seat. Of course I moved. Local loyalists have privileges. On another occasion a BFI staff member said that she worried that one of her friends might become “one of those sad front-row people at the NFT.” They didn’t seem unusually unhappy to me, but then they wouldn’t, for I am one of them.

My strangest contretemps with a front-row devotee came during a visit to the Munich archive. They were running Get Carter and I was the first entrant. I secured my front-row center post and settled down to read. (Front-row people show up early enough to finish substantial portions of Dostoevsky novels before the lights go down.) Suddenly an aged German lady, fortunately not Luise Ullrich, stood before me.

Seeing I was reading a book in English, she said, “Pardon me, you’re in my seat.”

I looked around and saw that we were the only people in the theatre.

“I always sit here,” she said. “I come every night.”

Nerdesse oblige. I relocated to the seat behind her. Moved by my gallantry, she twisted around to talk with me. I asked if she really came every night.

“Well, not every night. Not if they’re showing a Jap movie.” She looked severe. “I don’t like Japs.”

Comments about disloyalty to old friends leaped to my tongue, but I kept quiet.

Soon Get Carter started. The old bat immediately fell asleep.

She slept through the whole movie. I wanted to knock her upside the head. When I left, she was still out, snoring in my seat.

There are other drawbacks to the avant-garde spot in the movie theatre. Most people are bothered by handheld shots and 3D if they sit close, but I don’t find myself affected. Granted, I probably miss some of the surround-sound effects, which are apparently designed for a sweet spot far behind my territory. If it’s any compensation, the left/ right channels are really vivid for me.

The biggest drawback, though, is that you don’t have eyes in the back of your head. During Q & A sessions, you can’t track the conversation without twisting around in your seat. So I sit there as if I were listening to the radio. Worse, sitting close can render you oblivious to things going on behind you. If a fistfight broke out in that heavily populated rear section, you’d be in a poor position to watch it. Occasionally being in the front row makes me miss an outburst that was probably pretty entertaining but leaves me feeling like the guy in Pompeii who wondered why everybody was running past him just before a couple of tons of ash buried him.

A Drunkard’s Reformation (1909).

On the obliviousness scale, my most memorable front-row experience came during another overseas festival. A visiting actress of consequence had directed some feature-length films, and the festival had arranged a screening of one. This entailed setting up a video projector and preparing, far in advance, electronic subtitles in the local language. When the director saw me planted in the pole position she said, “You shouldn’t sit so close. This movie is like Dancer in the Dark.”

No problem, I assured her; I’d seen that from the front row too.

No one joined me in the front. But there was a sizeable audience. Once people had settled down, her introduction explained five things, each one adding to a litany of doom.

(1) She played the protagonist.

(2) The film was improvised.

(3) It was shot handheld.

(4) The actors were her friends.

(5) It was a satire on the superficiality of Los Angeles life.

She wished us a good screening and said she’d see us afterward for a discussion.

The film was as dire as I’d feared. When the lights came up I noticed that nobody was setting up the microphone on stage. I turned around. The technicians were putting away the projection equipment. I was the only viewer who’d hung on to the end. Needless to say, there was no auteur and no Q & A.

Despite all the drawbacks of front-zone sitting, I feel vindicated by a recent revelation. A review quotes James Wolcott’s acount of Pauline Kael’s preferred viewing station.

We take up mortar position in the back row. Pauline nearly always sits in the back, often right beneath the projectionist’s portholes, flanked by fellow critics on her squad. . . . (The auteurists — those ardent members of Andrew Sarris’s Raccoon Lodge — tended to huddle closer to the screen, as if to meld mind and image into a blissful, shimmering mirage of Kim Novak with her lips parted.)

I rest my case.

Thomas Schelling’s reflections on lecture-hall seating open his classic Micromotives and Macrobehavior. Among his more entertaining speculations on why people sit in the back is this one:

A fourth possibility is that everybody likes to watch the audience come in, as people do at weddings.

For some research on whether students sitting up front get higher grades, go here (abstracts only) and here. Jonathan Cohen provides a nice analysis of the research on perceptual constancy here. 3D has rekindled debates about where to sit; for one exchange among cinematographers, go here.

Le Pied qui étreint is discussed in more detail here.

Joe Dante at University of Wisconsin–Madison, November 2011. Photo by Jeff Kuykendall. For more on Dante’s visit, go to this earlier entry and to Jeff’s coverage here.

PS 23 January 2012: Please note that another couple likes to sit in the front row (from here).

As the summer winds down, is 3D doing the same?

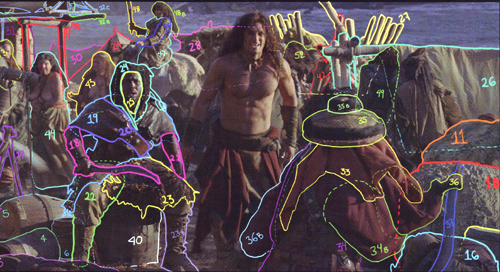

Something to do with 2D to 3D conversion for Conan the Barbarian. (See 3DLiveFlix)

Kristin here:

Just over a month ago I posted “Do not forget to return your 3D glasses,” an entry suggesting that on average theatres were making less money from 3D versions of films than 2D versions. I made two basic points. First, claims that films were making, say, 60% or 45% of their box-office gross from 3D showings were inaccurate. Only the extra fee charged at 3D screenings was for 3D; the rest was for the film as such. By that logic, something closer to around 10% was actually being earned by 3D (assuming people who went to see a film in 3D would probably see it in 2D if necessary.)

Second, my point was that if a film’s box-office percentage from 3D screenings was lower than the percentage of theaters in which it was being shown in 3D, then the exhibitors in those theaters were making less money than exhibitors showing the film in 2D. For most films that have come out this summer, starting in May, the percentage has been distinctly lower.

Wasn’t this supposed to be the summer of 3D?

With the summer movie season drawing to a close, I thought I would summarize some recent developments. These tend to suggest that the decline in the popularity of 3D in the U.S. market has continued. Indeed, a recognition of that decline has started to have an impact on the effort within the industry to pressure theaters into showing films in 3D.

During August I noticed for the first time that trade-paper and online sources are becoming more explicit about saying that 3D is no longer as big a draw as it used to be. Reporting on August 13, the day after the release of Final Destination 5, Variety stated, “Though roughly 89% of its screens are in 3D, and 217 are in Imax, ‘Destination’ isn’t expected to see much of a boost from the format given waning interest in 3D. Optimistic B.O. pundits have the film topping out at $21 million through Sunday.”

In fact, Final Destination 5 grossed over $24 million. That was, however, the lowest opening-weekend gross of the franchise. It made about 75% of its gross from 3D screenings, which occupied 80% of locations. That’s better than most 3D films of the summer in proportion of income to screens, but still not great. Its comparatively good performance in 3D suggests that genres like horror still tend to draw the spectators most interested in 3D. Final Destination 5 came in third after two non-3D films, Rise of the Planet of the Apes and The Help, both of which did much better than expected.

The weekend’s other 3D film, Glee the 3D Concert Movie, did so badly that the trades didn’t bother to report its percentages of 3D screens in proportion to income. Its box-office gross put it at #11 on the chart, earning less than $3000 per screen.

The following weekend, August 19-21, saw Rise of the Planet of the Apes and The Help switch slots on the chart, with The Help becoming the first film since January to rise from a #2 opening to the #1 rank—a position it held this past weekend as well, experiencing a low 28% drop despite East Coast theatre closings due to the hurricane.

That same weekend saw three 3D films do lackluster business. Of those, Spy Kids: All the Time in the World did the best, coming in at number 3. About 44% of its income came from 3D, which fits into the 45% level typical of 3D films this summer. Interestingly, though, only 41% of the locations where the film was shown had it in 3D. Variety’s report on Saturday remarked, “The summer’s new norm is to make about 45% of grosses off 3D screens, though that figure could be even lower this weekend with so many pics vying for 3D play and so many of ‘Spy Kids’ engagements opting for 2D.”

There are two implications here. First, if fewer theaters show a film in 3D, the ones that do will make more money, since those moviegoers interested in seeing a film in 3D will converge on that smaller number of theaters. There apparently are not enough such moviegoers to justify having 60% or more of theaters showing 3D. Second, given that four 3D films were debuting that same weekend, theater owners opted to show the film aimed at young children in 2D. We know that there have been complaints that children don’t like wearing the glasses and that parents don’t like shelling out extra fees to take a whole family to a 3D screening. The strategy worked, which again suggests that genres aimed at teenagers might provide the home for 3D, if it survives long-term.

Don’t worry, that includes the whole family. (Just kidding! It’s actually a ticket to last year’s “OnHollywood” trade summit, where 3D was discussed.)

But the teenage-targeting assumption didn’t work out well for the two other 3D debuts of that weekend. Conan the Barbarian showed in 3D in 71% of its locations, but only 61% of its gross came from those locations. The figures were almost identical for Fright Night. Perhaps the two films split the teenage audience, to the detriment of both. Glee fell off 69.4% in its second weekend, to an average of less than $1000 per screen.

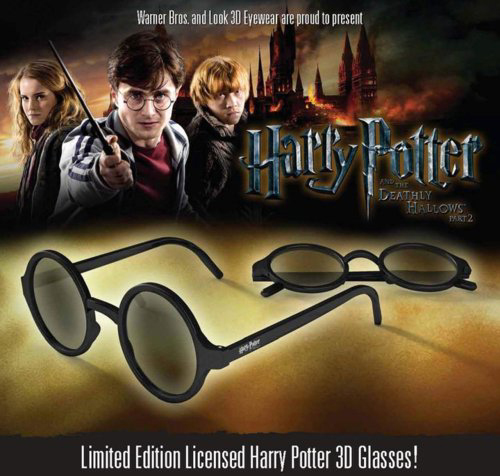

The weekend of August 19-21 saw six 3D films in the top 11. (I list 11 rather than 10 because the 11th was the summer’s most successful film and a 3D item, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows Part 2.) The 11 were, in order (3D films in bold): The Help; The Rise of the Planet of the Apes; Spy Kids: All the Time in the World; Conan the Barbarian; The Smurfs; Fright Night; Final Destination 5; 30 Minutes or Less; One Day; Crazy, Stupid, Love; and Harry Potter. Of those six films, only two, Harry Potter and The Smurfs, made it to number one—for only one week each, remarkably.

Still doing well abroad

The big Hollywood studios continue to defend 3D as a financial strategy, since films made with the process continue to clean up in most foreign territories. Even though the percentage of 3D box-office income has fallen to a fairly consistent 45% (apart from the occasional genre film), it still provides about 60-70% of the international gross. (Unfortunately percentages of theaters showing 3D films aren’t given in such reports.)

Variety’s Andrew Stewart helps explain how some foreign markets encourage 3D viewing:

To some degree, the divergence can be chalked up to a matter of preference — some cultures just like 3D more than others for reasons that can’t be quantified, and big-budget f/x spectacles continue to draw big auds overseas — but there are also some subtle differences in local pricing models that provide insight to studios and exhibitors eager to see 3D pay off on its promise of enhanced B.O. takings.

Some notable factors: Many international markets temper 3D upcharges with discount play periods. China has half-price Tuesdays. In Germany, “Cinema Day” brings a steep midweek price drop to matinees. And some territories even charge less for 3D pics that have shorter running times. In many countries, premium ticket prices for 3D are further mitigated because moviegoers are encouraged to buy their own reusable glasses.

[…]

Some Japanese exhibs ease 3D ticket prices by charging less to those who bring their own glasses. Dolby controls most of the Japanese 3D market, and in March, the company started offering reusable 3D glasses for $12 per pair. In Europe, RealD sells its reusable glasses at concession stands or the ticket window for about E1, saving auds the repeated expense.

But if theaters attract customers by giving discounts or waiving fees for those who bring their own glasses, how long can the high proportionate income from 3D hold up? Sales of glasses benefit the technology companies, not the theater or studios, and eventually the market will be largely saturated.

So far 3D is holding up well in most foreign markets, but there is one exception. In Spain, where the 3D premium averages a whopping 37%, Transformers earned 49% of its national gross from 3D, Pirates of the Caribbean 41%, and The Smurfs 39%. Variety blames the sag on 22% unemployment and “rampant piracy.” But unemployment and piracy aren’t unique to Spain by any means.

And foreign markets got into 3D exhibition a bit later than North America did. There’s nothing to say that ticket premiums and the decline in the novelty value of 3D won’t start affecting international exhibition eventually.

A certain lack of confidence

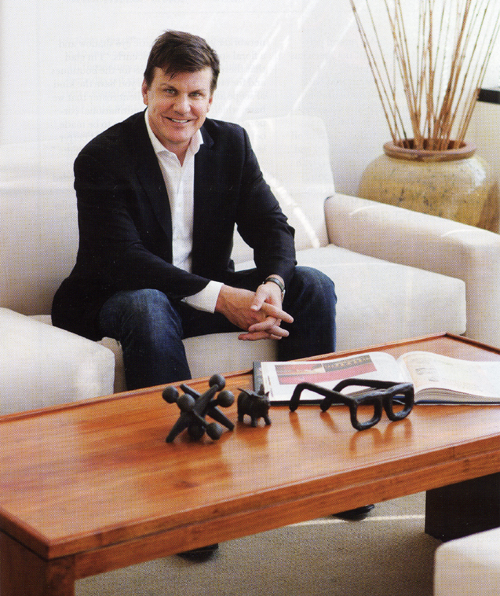

The August 12 edition of The Hollywood Reporter revealed that RealD’s “stock has plunged 60 percent since reaching a 52-week high in June as U.S. audiences seem to tire of the format.” Now that’s serious. Two weeks later, in the August 26 edition, a smiling Michael Lewis, the firm’s CEO (below), was given a two-page spread with an interview where he explained why he thought Wall Street was overreacting. (These references are to the print edition; online they’re behind a pay wall.)

Clearly, it was an overreaction. We had record earnings. We’re a relatively new company, and as time goes on we’ll prove the model. It doesn’t really matter if a film does 40 percent or 50 percent; we just believe this is a transformative event like the Internet and the personal computer. All visual displays are going to get better, and we’re really well positioned. Over time, Wall Street will figure that out.

That’s a remarkable claim. Many of us might say, “I don’t know how I got along before computers” or “before the Internet.” How many people would really say “I can’t imagine what we did before 3D came along”? This is hardly a transformative event on a scale even vaguely close to those two technologies. I can easily get along without seeing a film in 3D, but I would never go back to an era when endnotes didn’t rearrange themselves automatically  when you moved or added a reference in your text. Think, too, how profoundly computers and Internet have affected the world financially, and then compare that with the impact of 3D.

when you moved or added a reference in your text. Think, too, how profoundly computers and Internet have affected the world financially, and then compare that with the impact of 3D.

Lewis also seems disingenuous when he claims that whether a film does 40% or 50% of its business in 3D “doesn’t really matter.” It certainly matters to the local multiplex owner who sees more people going into an auditorium showing a movie in 2D than another auditorium showing it in 3D. It matters to the distributor who gets a cut of the take and to the studio that gets the remainder–and had to pay extra to begin with to make the film in 3D.

He may be right, though, that Wall Street overreacted. The interview includes some impressive figures. RealD controls roughly 85% market share of the domestic 3D box office. (Apart from selling its projection systems, special screens, and glasses to theaters, RealD gets a licensing fee averaging fifty cents for every ticket sold.) Within the U.S., it has 10,300 screens in 2,500 locations; abroad, the number is 7,200 screens in 2,300 locations. The firm’s 2011 fiscal-year revenue was $246.1 million, up 64% from the previous year. Its fiscal-year 2011 gross profit was $67.7 million, up 633%. This is flashy–though such growth came during the post-Avatar era when theaters which had missed out on the film’s bonanza were buying 3D equipment at a good clip, and more 3D films were in the pipeline. (Lewis says 2011 will see forty 3D films released.) If theater conversion is nearing saturation point and 2D screenings are outdrawing 3D ones, though, this summer may mark the end of the expansion for companies like RealD.

Lewis doesn’t exactly win me over either with his notions of what to do with 3D. He’d like to convert Singin’ in the Rain into 3D. That and The Love Bug. You know, the great classics. Plus he has a rather peculiar idea of Avatar‘s place in film history. Asked what Cameron’s film did for the business of 3D, Lewis responded: “It legitimized it. It was the Citizen Kane of our medium. After Avatar, I finally didn’t have to go into a meeting and explain why this was going to be important for our industry. The numbers spoke for themselves.” No doubt Avatar‘s phenomenal box-office success made exhibitors who had not yet installed 3D equipment keen to do so. But Kane was in fact not a financially successful film. No one could say of it, “After Kane, I didn’t have to go into a meeting and explain why deep focus was going to be important for our industry. The numbers spoke for themselves.” Both films are undoubtedly historically important, but there’s really very little comparable about them.

Auteurs to the rescue?

Speaking of legitimacy, Lewis is looking forward to the releases of Martin Scorsese’s Hugo in November and Ridley Scott’s Prometheus next year. On August 12, the Wall Street Journal ran a long story by Michelle Kung on how a trio of Movie Brats are about to reveal their first 3D films. Hugo is scheduled for November 23, Steven Spielberg’s The Adventures of Tintin for December 23, and Francis Ford Coppola’s Twixt premieres in September at the Toronto Film Festival.

Spielberg’s popularity among a broad range of audiences remains intact, though whether Belgian import Tintin can win American spectators’ hearts remains to be seen. Whether Scorsese and Coppola, beloved of audiences of my generation, will prove the final boost that 3D needs is up for grabs. Coppola seems a particularly unlikely auteur to pin one’s hopes on. Twixt, a low-budget horror film, has only five minutes of 3D footage, and it has yet to find an American distributor. According to Anne Thompson’s blog, the director “first showed the film to distributors in Los Angeles Wednesday night [i.e., August 24]. Unless he gets a rich offer, Coppola will likely four-wall the film himself; he’s looking to sell video rights.” Today’s Variety reports that Pathé has picked up Twixt for “international sales and distribution in France.” That doesn’t seem to settle the question of a U.S. release.

A more likely shot in the arm for 3D would seem to be Peter Jackson’s Hobbit film, being shot even as I type. It should appeal to teenage 3D buffs and just about everyone else. But the first part is not due out until December, 2012. I suspect that the degree to which 3D will penetrate the theatrical market will be known by then.

The article quotes Jeffrey Katzenberg, who years ago claimed that every screen would eventually be converted to 3D, as saying “You now have some of the greatest filmmakers in the world stepping into the format to tell their stories.” Scorsese has gamely stepped up to the plate, commenting that if 3D had been around when he made Mean Streets or Taxi Driver or Raging Bull, “those stories would have fit in perfectly in 3-D.” It’s a bizarre thought, but maybe he’s serious.

Kung provides some interesting figures. It’s difficult to get a sense of how many people are opting to see 3D films in their 2D versions. Usually the comparison is made in terms of box-office gross rather than number of tickets. But the author says that 57% of people who saw the final Harry Potter film this summer opted for 2D, which seems a pretty significant figure. She also notes the falling stocks of RealD and other 3D firms:

“Consumers are pushing back,” says Richard Greenfield, an analyst at brokerage firm BTIG. “They’re tired of 3-D, both from a price perspective and from a physical-comfort perspective.” He adds that consumers have come to a key realization: A bad film in 3-D is still a bad film.”

Kung says that about 30 new 3D films are due for release next year. If Lewis’ figure of 40 for 2011 is accurate, that means a notable drop in planned 3D productions for the short term. Possibly it’s a temporary one, but perhaps studios are beginning to think that the extra returns from their share of those ticket premiums aren’t worth the cost and effort. If 57% of Harry Potter‘s audience opted for 2D, then perhaps an increasing number of theater owners are refusing to book 3D films from the distributors.

That figure of 30 releases doesn’t include the announced 3D conversions of Titanic and the Star Wars series, which may or may not be ready for release next year. The rumors of such conversions for these and other popular items like the Lord of the Rings film have been circulating, but precious little information on how, when, and where these will eventually reach theaters has been forthcoming.

As I’ve said in my previous posts on 3D, I don’t see any reason why the format would necessarily disappear. Once the match of number of 3D screens and number of moviegoers who want to see 3D movies reaches a reasonable balance–which at this point seems to mean a significant number of current 3D screens reverting to 2D–both formats will make money and 3D will continue, especially for blockbusters and teenage-oriented genre films. But the idea that studio and company executives can simply dictate that the entire public should embrace what is, after all, a relatively superficial technology added onto an already stable and successful product seems overweening and implausible. This summer’s movies have seemingly reflected the public’s more realistic attitude.

And now, enough of 3D. Unless something dramatic happens between now and when Hugo comes out, I shall hold off writing on the subject until we see what happens during the holiday season, when the format faces its next big test.

P.S. August 31: The Fandor blog has a post by Alejandro Adams, a filmmaker who manages a multiplex in northern California. He reports that until recently, studios demanded that all 3D films be shown only in 3D, no matter how many screens were available. Adams reports that this summer: “We’d just opened Captain America ‘over/under,’ meaning that we were offering two 2D shows and three 3D shows in a single auditorium. This was the first time any studio had allowed us to restrict the number of 3D shows. When I checked the grosses after opening day, I was alarmed. We sold twice as many tickets for 2D as 3D. As we’d never booked a 2D engagement of any film available in 3D, I’d never seen this disparity up close. The fact that we were permitted to over/under Captain America in 3D and 2D is itself a distressing development—are the studios suddenly willing to admit they didn’t hit the jackpot with the 3D craze? Are they going to start phasing out 3D so soon after we went to the trouble and expense of making our projectors and screens compliant with their demands?”

Adams calls this a “distressing development,” being a fan of 3D, both for his own and his children’s enjoyment. If my hunch turns out to be correct, they will still have the 3D option, but others will have access to 2D screenings.

RealD’s Michael Lewis. Hmm, those glasses do look a bit clunky. (Photo by Peden + Munk)

Despoiling the movies

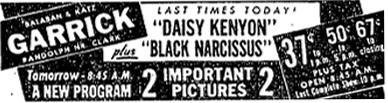

The Denton Record-Chronicle (28 December 1947).

DB here:

The last line of Otto Preminger’s Daisy Kenyon is “When it comes to modern combat tactics, you’re both babies compared to me.” If you haven’t seen the film, does knowing that ruin it for you? Suppose I went further and identified the character who spoke the line, or the immediate circumstances, or the action leading up to it? Would knowing these things ruin your pleasure? Or would it give you a different sort of pleasure?

Who doesn’t come to Casablanca knowing about “Here’s looking at you, kid,” or “Play it, Sam,” or “Round up the usual suspects”? You likely saw the ending of King Kong in compilation films before you saw the whole movie, yet you probably still watch it with enjoyment. I saw Potemkin’s Odessa Steps sequence many times, on an 8mm reel I bought as a kid, before I saw the whole movie. I still enjoy Potemkin, possibly more than many who see it for the first time. Yet people complain about trailers that tell too much, and critics who give plot twists away. Accordingly, it’s been a convention of fan and Net writing that if you’re going to give away major story information, you alert readers with the word “spoiler.”

Surely people want to know something about a film’s story. Viewers clamored for the most basic information about Super 8. And evidently many moviegoers would feel less disgruntled about The Tree of Life if they had known in advance a little bit more about what they would encounter. It seems we want to know about the story’s basic situation, but not too much about how things develop. Say: bits from the first half-hour or so, up to the beginning of the Second Act (or what Kristin calls the Complicating Action). Beyond that, we want things kept quiet. Above all: Don’t tell the how things turn out in the end.

I’ve been driven to think again about spoilers after Jonah Lehrer reported on an experiment with literary texts. On the whole, readers in the study reported enjoying a short story somewhat more if they knew the ending in advance. Jim Emerson has provided his characteristically stimulating commentary on this finding, and his readers, surely among the most reflective in the online film community, have supplemented his thoughts.

This discussion overlaps with a question I raised a while back on this site. How can we feel suspense if we know a story’s outcome? One standard answer, which would apply to spoilers too, is that even with foreknowledge, we’re interested in how that turn of events comes about. This possibility is invoked by some of Jim’s readers, and it seems plausible, especially if one is a connoisseur of storytelling. How, we ask, does the narrative engineer this or that twist?

My further proposal in the blog entry was that our mind’s intake of narratives is modular in some respects. Part of us reacts as if we were encountering the events fresh, without knowledge of what is coming up. The analogy was to standing on a balcony overhanging a precipice. You know that you cannot fall, but when you imagine yourself falling, you feel a twinge of fear all the same.

The same might be true of consuming a narrative. One of our mental systems, fast but fairly dumb, reacts to things as they come, while secure knowledge hovers more distantly in the background. I suggested as well that the way that something is presented–say, with fast cutting or sweeping music–can override our knowledge and kindle a basic, more visceral response.

Today’s entry tackles the matter of foreknowledge from a different angle. It’s worth remembering that many people who went to the movies in the 1920s through the 1950s willingly subjected themselves to spoilers.

This is where we came in?

Chicago Daily Tribune (4 January 1948).

While the American studios developed their storytelling strategies in the 1920s and 1930s, movie exhibition became a big business. In 1935, eighty million Americans went to the movies every week. The historical high point was 1946-1948, when annual attendance hit 4.7 billion. But how did all those people see the movies? More specifically, did they watch them from start to finish?

We’re so used to showing up at a definite time for a screening that it’s hard to imagine a period when many viewers would simply drop in to what were called “continuous admissions” or “continuous performances.” In major cities, the film programs, complete with newsreels, cartoons, trailers, other shorts, and even a second feature, would run steadily with only brief intermissions. You could drop in any time.

When the houses filled up, prospective viewers would have to wait in line outside or in the lobby until someone left. Then an usher would show the next patron to the empty seat. Meyer Levin’s novel The Old Bunch describes a group of friends waiting forty-five minutes before just getting into the lobby of a Chicago theatre in the 1920s.

Some of the viewers would depart during the main or second feature. Naturally, the patrons admitted in medias res would see the end of a movie before they caught up with the beginning, perhaps some hours later. Hence the phrase, “This is where we came in,” meaning, “Now we’ve seen the whole picture and can leave.”

After Kristin, Janet Staiger, and I wrote The Classical Hollywood Cinema, a few readers asked why we hadn’t talked about continuous admissions. The practice would seem to explain a lot about the redundancy of Hollywood storytelling. Hyperexplicit exposition, the Rule of Three (say everything important thrice), and the habit characters have of reminding us of their relations to each other (“Gee! You’re the swellest sister a guy ever had!”)—all this would seem to be aimed at a viewer who might well have come in halfway through and need orienting to basic plot premises.

We knew about continuous performances, of course, but we didn’t discuss them because we could find no evidence that filmmakers took these conditions into account when designing their stories. In reading Hollywood screenplay manuals, technical journals, and the like, I didn’t find anyone commenting on the exhibition practice. My colleague Lea Jacobs, who has scanned Variety very comprehensively for the 1920s and 1930s, can recall no mentions of it affecting production policies.

When you think about it, screenwriters and directors couldn’t really do much to bring a latecomer up to date. You can’t keep reiterating story premises and recapitulating all that went before, and still move the plot forward. Better to tell the story straightforwardly and assume, as a default, that under ideal circumstances people would see the whole film from scene one onward. The same assumption governs TV writing, despite viewers’ channel surfing and foreplay with the remote.

Still, during the Golden Age of Hollywood a significant population consumed movies knowing how the story turned out before they saw the beginning. Ask people of my generation or older, and you’ll usually hear: “Oh, we went whenever we wanted. We never tried to find the showtimes.” My childhood moviegoing memories are dim, but I recall being dropped off at the Elmwood Theatre by my parents when they went to town. I’d go in during the movie (I do recall The Sad Sack, 1957) and watch until my mother or father fetched me out. It’s very likely that adults drifted in at odd times as well.

There’s harder evidence that some people preferred convenience to coherence. In 1950 Twentieth Century-Fox announced that All About Eve (1950) would be screened only in “scheduled performances.” No one would be seated after the film began. Premiering at Manhattan’s Roxy Theatre, Eve ran for a week under the new policy. It failed. People hadn’t heard about the new rules, showed up late, and weren’t admitted. The results were angry lines outside and empty seats within. The practice was halted and Eve screened in continuous performance. The Hollywood Reporter attributed the failure to “the public’s deeply ingrained habit of going to a movie show at any desired hour, when most convenient or on impulse.”

In other words, many people were encountering what we call spoilers all the time, and it didn’t seem to bother them. So you wonder: Is watching a movie straight through, as we mostly do today, a newer, more “disciplined” mode of consumption?

It’s showtime

Daisy Kenyon.

It’s obvious that the custom of just dropping in didn’t guarantee a nonlinear movie experience. With a double-bill house, even if you dropped in arbitrarily, you would see one feature or the other in a single gulp. And assuming a three-hour program and a 90- or 95-minute A picture, your odds of walking in during the shorts or the B film were about fifty-fifty.

But were people obliged to drop in willy-nilly? Could they have seen the movie straight through if they wanted to?

There’s considerable evidence that parts of the audience did want to see the movies in linear fashion.Consider the early attenders. And many cinemas filled up quickly just before the show started. Coming in when the theatre opened seems a fairly clear indication of wanting a linear experience. True, early attenders would probably have to sit through a newsreel, trailers, and other shorts, but many people enjoyed those too. Further, since double-bill houses screened the A picture first, knowing that custom could guide your decision about when to come in.

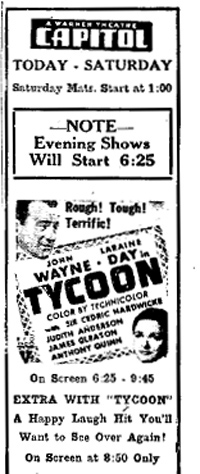

Could patrons have gained specific information about when the movies were screening? There’s a widespread belief that theatres didn’t publicize showtimes. But that’s not the case.

First, the box office almost always posted a schedule breaking down the program. Sometimes cardboard clocks with movable hands indicated showtimes. Patrons might see the schedule when they arrived, or while passing the theatre during the day. Knowing the schedule, you didn’t have to go straight in. If you bought your ticket while the feature was running, you could linger in the lobby. Probably some viewers were reluctant to enter if the feature they wanted to see was just ending.

Second, there were newspaper advertisements. This evidence is varied and intriguing, full of unexpected quirks. First, I took a look at late 1940s ads for the Elmwood, my hometown venue. These ads are mostly bare-bones. They list the movies, all double features, with three changes a week (films played Friday-Saturday, Sunday-Monday, and Tuesday-Thursday). The theatre doesn’t supply its phone number, probably because many families in our area didn’t have phones until the late 1950s. Showtimes are seldom mentioned. Doubtless townfolks knew by local custom what the showtimes were, and there was no need to advertise it in newspapers or handbills (which were still around in the 1950s). One September 1949 item specifies opening and closing hours:

Matinees Daily 2:00

Evenings 7:00 to 11:30

Sundays and Holidays Continuous 2:00 to 11:30

Knowing these hours of operation, people who wanted to see the movies straight through could show up at 2:00 or 7:00.

Knowing these hours of operation, people who wanted to see the movies straight through could show up at 2:00 or 7:00.

But some ads in other towns get a little more specific. “2 COMPLETE SHOWS 9:30 & 12 MIDNITE,” blares the Colonia of Norwich, New York in 1947. This indicates the starting times for the newsreel, cartoon, and ads, which all preceded the main feature. But since many theatres began their screening at 6:00, the accompanying ad from the Capitol, of Dunkirk, New York in 1948 seems to be saying that after all the shorts and ads, Tycoon hits the screen at 6:25. That movie ran a little over two hours, so there was time for filler leading up to the Happy Laugh Hit (presumably a revival). More unequivocal is the ad for Daisy Kenyon at the very top of this entry, which specifies when the feature starts. Again, the theatre probably opened at 1:00 and brought in the evening crowd at 7:00. That left fifteen minutes or so for pre-show material, including the color cartoon and “Global News”.

In short, some newspaper ads tell us only the theatre’s operating hours, while others specify showtimes. This sort of variation goes far back. The Olean (New York) Evening Herald advertised the Strand Theatre as “showing continuously 1 to 11 daily,” with no showtimes mentioned. On the same page we find specific starting times listed for a rival theatre’s showings of Fairbanks’Mark of Zorro (1921).

For special occasions, the scheduling could be quite exact. If you happened to be in Middletown, New York, on New Year’s Eve of 1947, you could welcome in “Kid 1948” at a gala show starting at 7:00 and ending “some time in 1948.” But not just “some time”: The State’s plan has a military precision.

Daisy Kenyon at 7:00 – 9:29 – 12:01

Comedy “Skooper Dooper” at 8:38 – 11:08

Terrytoon Cartoon “Silver Streak” at 9:12 – 11:42

Community Sing at 9:19 – 11:49

Latest Pathe News at 8:56 – 11:26

The ad goes on:

No seats reserved – No waiting in line. Come any time from 6:30 until 11:20 and see a complete show—Stay as long as you like! Come in one year—Leave the next!

The rival Goshen Theatre likewise provided a detailed schedule of its New Year’s Eve attractions, an astonishing four features plus cartoons. The show, broken into 9 “units,” started at 7:00 and ended at 1:00 in the morning, concluding with an “Exit March.” Why don’t movie theatres have exit marches any more?

Apart from ads specifying showtimes, we can glean other hints that at least some viewers preferred to know when to arrive to catch a film from the beginning. Some newspapers published lists of starting times. The New York Evening Post printed an extensive “Movie Clock” covering over eighty theatres. A Schenectady paper did the same thing under the rubric “Showing Today. What the Theatres Are Advertising.” You can find a similar feature in papers from Portland and Council Bluffs. Movie houses were often a small-town newspaper’s biggest and most reliable advertising source, so many editors were ready to oblige theatre managers.

Movie ads also sometimes included the theatre’s phone number, so people could call to check showtimes. Access to telephones was still spotty then; recall that the infamous Gallup Poll of 1948 misjudged Dewey’s chance for victory, partly by relying on phone surveys. But by 1945 there were about 16 million residential phones for a population of 140 million, so the middle-class people sought by exhibitors, then as now, might well be able to call up the movie house.

That is, in fact, what Daisy Kenyon does at one point in her movie. Having decided to go out with her girlfriend, she checks the phone number of the theatre she wants to visit and starts to call to check on showtimes. (She’s interrupted by a call from the mysterious Peter Lapham.) The scene seems to model one set of urban filmgoing habits.

Historian Douglas Gomery reminds us that there were many different sorts of theatres–first-run and subsequent-run, big downtown houses and neighborhood venues, rural ones, art houses, and so on. I’ve tried to capture some of this variety in my exploratory sample, but there are many fine-grained differences. Moreover, roadshow pictures often played to strict schedules, selling tickets for specific performances, and people adjusted their schedules to that regime for Gone with the Wind and other blockbusters. Perhaps the All About Eve fiasco came from people thinking this new film, in black-and-white and offered at regular admission prices, was not an event film like the usual roadshow attraction.

In all, it’s hard to generalize about viewing patterns. But it seems fair to say that in many circumstances viewers could, if they wanted, avoid seeing a movie’s ending before the beginning.

Which means that, then as now, we find different viewing styles. Today we have the Planners, who Tivo their cable television offerings, and the Grazers, who hop from channel to channel and watch in medias res. (We also have the Gleaners, who sample items at their leisure via the net. But there doesn’t seem to be an equivalent option in classic theatrical film viewing.) Several of Jim Emerson’s cinephile readers point out that they appreciate spoiler alerts in a web review because they want the choice between knowing and not knowing. It seems that in many circumstances movie houses offered 1940s viewers that same option.

Exhibition history is far from my specialty, so I’d welcome information from researchers who’ve studied this question more systematically. In the meantime, I’m grateful to Kristin, Ben Brewster, Lea Jacobs, Vance Kepley, Betty Kepley, John Huntington, and Virginia Wright Wexman for discussion with me. A special thanks to Douglas Gomery, who shared detailed information in emails and phone conversations.

For a comprehensive history, see Douglas Gomery, Shared Pleasures: A History of Movie Presentation in the United States (University of Wisconsin Press, 1992). See also Gregory A. Waller, Moviegoing in America: A Sourcebook in the History of Film Exhibition (Wiley-Blackwell, 2001) and Going to the Movies: Hollywood and the Social Experience of Cinema (University of Exeter Press, 2007), ed. Richard Maltby, Melvyn Stokes, and Robert C. Allen. Allen has mounted a beautiful online archive devoted to moviegoing in North Carolina.

A useful older source, though not focused on the 1940s, is Frank H. Ricketson, Jr., The Management of Motion Picture Theatres (McGraw-Hill, 1938). Ricketson advocates three hours as a maximum program time.

The motion picture theatre has a constant drop-in trade, and the patron who catches the feature after it has started does not want to sit through a seemingly endless program to see the part that he has missed. The tendency today is to present shows that are too long (p. 121).

It’s possible that as an employee of Fox Theatres, Ricketson was pushing the then-common industry view that double features were undesirable. Fewer films on the bill allowed more turnover during the day and favored the higher-profit A pictures.

Information about All About Eve‘s “scheduled performance” policy comes from the American Film Institute Catalog. See also “Business on ‘Eve’ at Roxy Jumps After Scheduled Showings Cut,” Boxoffice (28 October 1950), 50, available here. Linda Williams argues that Psycho‘s exhibition policy helped create the custom of consuming a movie straight through. See her “Discipline and Distraction: Psycho, Visual Culture, and Postmodern Cinema,” in “Culture” and the Problem of Disciplines, ed. John Carlos Rowe (Columbia University Press, 1998).

My analogy to standing on a precipice comes from Noël Carroll’s The Philosophy of Horror.

Two final points I couldn’t squeeze in elsewhere. First, to a large extent, spoilers are a function of different sorts of movie talk. In daily conversation, we’re reluctant to tell too much to friends who haven’t yet seen the film. Journalistic film reviewers seek not to reveal the ending, of course, but they’re also obliged to write about many scenes in an oblique way. (“After a string of preposterous coincidences…”) Net writers seem to model their comments on conversation and professional reviews, although some rascals delight in telling innocent readers everything that happens. We might call them spoilersports.

By contrast, academic writing assumes that the reader has seen the film, or is willing to let details be divulged for the sake of some larger point. Occasionally bloggers adhere to this standard. Readers of J. J. Murphy’s blog know that he doesn’t refrain from synposizing a plot to give depth to an analysis. I’ve done the same thing here on many occasions, but sometimes I feel the need to signal spoilers, particularly for current releases or films that depend on big twists. For some reason, I think that older films are fair game for full-blown discussion, even though many of our readers are less likely to have seen Enchantment than Source Code.

Second point, pure digression: In 1947, Richard Hull published Last First, a mystery novel dedicated “to those who habitually read the last chapter first.” The opening chapter does provide the story’s ending, but as you’d expect there’s a trick. The chapter is written so obliquely that you can’t really tell who is doing what to whom. At least I can’t.

P. S. 18 May 2012: Two more items that I’ve run across relevant to the this-is-where-we-came-in problem. First, this dialogue exchange from Ellery Queen’s serial-killer novel of 1949, Cat of Many Tails. The murder victim, one investigator says, “left for a neighborhood movie. Around nine o’clock.” The other asks, “Pretty late?” The reply: “She went just for the main feature.” This suggests that in Manhattan, it wouldn’t be impossible to know when the main feature played for the last time–either from the newspaper, from a phone call, or just from custom.

It seems that indeed late shows of the A picture were common. A 1939 Variety article, “‘Bad’ Scheduling Squawk” (27 December 1939, 5, 47) indicates that often the “No. 1 film” was put on at awkward hours, and viewers objected. “Too often, it is declared, a customer will call the theatre, only to learn the film he or she wants to see goes on at a time that interferes with dinner, or it’s on the last show, so late that getting out would be around midnight or thereabouts. Result, under theory, is that the customer doesn’t go at all.” Again, we find some evidence that the public could find out when a movie played by phoning, and that at least some patrons cared enough to see the picture through from the start. This piece from 1939 suggests that these options were available at least in some towns throughout the 1940s. Presumably, this practice was prominent in theatres not controlled by the studios, since the B picture was a flat-rate rental but the No. 1 feature was a percentage booking. The more tickets you could sell for the B, the bigger the exhibitor’s share of receipts.

P.S. 21 May 2012: The Wisconsin Project never sleeps. Alert Ph. D. researcher Andrea Comiskey sends me 1939 ads from the Olympia in Portsmouth, New Hampshire and the Fox in Billings, Montana. Both lists start times for both features, A and B, with the Fox including the start times for cartoons and newsreels too. The heading is, bluntly, “When to Come Today.” As per the above addendum, the Fox runs the A picture last, and quite late (around 10 PM).

P.P.S. 1 February 2021: Ran across this in John O’Hara’s novel Butterfield 8 (1935):

“What are we up to this afternoon?”

“Oh, whatever you like,” she said.

“I want to see ‘The Public Enemy.'”

“Oh, divine. James Cagney.”

“Oh, you like James Cagney?”

“Adore him.”

“Why?” he said.

“Oh, he’s so attractive. So tough. Why–I just thought of something.”

“What?”

“He’s–I hope you don’t mind this–but he’s a little like you.”

“Uh. Well, I’ll phone and see what time the main picture goes on.”

“Why?”

“Well, I’ve seen it and you haven’t, and I don’t want you to see the ending first.”

“Oh, I don’t mind.”

“I’ll remind you of that after you’ve seen the picture.”

Daisy Kenyon. Daisy and her friend, tracked by Peter and watched by a waiter, have apparently gone to a revival house–and one not playing pictures from Fox, the studio behind Daisy.

Do not forget to return your 3D glasses

(Yours for $11 in theaters equipped with RealD systems, but you don’t get the pouch they came in at the opening midnight screenings)

Kristin here:

As 3D really took hold in the wake of the release of Avatar in December 2009, we got used to hearing that roughly 60% of a blockbuster’s income came from 3D. This summer the figure has hovered around 40%. Both figures are highly misleading. How much does 3D really bring in?

Yes, 40% of the total amount for almost all big 3D films this summer was for tickets sold for 3D screenings. But looked at another, more realistic way, 3D films as such made far less than that for their makers and the theaters that showed them.

That’s because a lot of the people buying tickets to see a film in 3D probably would have gone to see it if it had been strictly 2D. That, is, 3D itself is probably not luring in many new viewers. If every person buying a 3D ticket would refuse to see the film in 2D, then, yes, the figure would be 40%. I’m sure a small percentage of people are lured to see a given title only because it is in 3D. There’s no way to know how many, however, so let’s stick to the facts we do know.

The basic fact is that the money brought in by a film made in 3D only amounts to the supplement paid by the spectator beyond what he or she would have paid if the film were in 2D. Let’s assume that the supplement is $3 and that a 3D admission costs $12 and a 2D one $9. Let’s also assume for the sake of argument that everyone who saw the film in 3D for $12 would pay $9 to see the same film if it were only available in 2D. (In reality, there’s also evidence that 3D keeps some people away from a film altogether if they don’t have access to 2D screenings. I’ll assume these two groups, the 3D enthusiasts and the 2D hold-outs, cancel each other out.) Removing the $3 supplement takes away 25% of the ticket price. So what the 3D process as such really adds to the box-office total is 10% (that’s 25% of 40%). To put it another way, $9 of the $12 for the ticket is just for the film qua film, the rest is for its being in 3D.

In addition, the costs for the glasses and any extra labor they entail have to come out of that $3. I don’t know what such costs are, so I’ll leave those expenses out of the calculations.

Consider the opening weekend of Captain America, which grossed $65.7 million, 40% of which came from theaters equipped with 3D. But it’s really 10% by my reasoning, so it’s not $26.3 million that 3D generated, but $6.57 million. Assuming further that it costs about $30 million to make a film in 3D or convert it to 3D in post-production, Captain America would have to run in the U.S. market for around four weeks with no decline in attendance to break even on 3D. But most films decline on their second weekend, unless they open in more theaters or have terrific word of mouth. Even The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring, which had lots of repeat business, declined 19% on its second weekend.

Of course, the popularity of 3D films is holding up better abroad than in the domestic market–so far. Still, we have to remember that only about half of the worldwide box-office receipts make their way back to the studios. That seems to imply that a film would have to gross $600 million internationally to break even on the addition of costs for 3D. ($300 million going to the studios, roughly 10% of which is paid for by 3D supplements=$30 million.) Some films do gross that much. Pirates of the Caribbean: On Stranger Tides, Transformers: Dark of the Moon, the final Harry Potter installment have passed that mark this year. It’s not common, though.

Naturally if a film takes in as much as 60% of its box-office from 3D screens, as Transformers: Dark of the Moon did, 15% of the costs of 3D will be paid for by the process.

How consistent is the trend?

Let’s look at the major 3D films out so far this year in terms of percentages of gross vs. percentages of theaters:

Film: Release Date (% of BO from 3D / % of locations showing 3D)

Green Hornet: January 14 (69% / 75%)

Gnomeo and Juliet: February 11 (58% / 60%)

Rio: April 15 ( 58% / 68%)

Thor: May 6 (60% / 69%)

Pirates of the Caribbean: 4: May 20 (46% / 66%)

Kung Fu Panda: 2 May 26 (45% / 69%)

Green Lantern: June 17 (45% / 71%)

Cars 2: June 24 (37% / 61%)

Transformers: Dark of the Moon: 3 July (60% / 70%)

Captain America: July 22 (40% / 68%)

Opening weekend only : Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part 2: July 15 (68% / 71%)

[Added July 31: The opening weekend for The Smurfs followed a similar pattern. The July 29 release made 45% of its gross from 3D engagements; 60% of its venues showed 3D. As Box Office Mojo points out, on the same weekend in 2009, G-Force made 56% of its opening-weekend gross in 3D, which showed in only 43% of theaters.]

(Granted, there is a problem with such figures. The percentage of locations showing 3D is based on theaters, not screens. Any multiplex showing 3D counts as 1, even though it may have 3 screens showing 3D and 2 showing 2D. Whether those two 2D screens would be credited to the venues showing 3D or 2D is not stated. Unfortunately, the way box-office figures are reported, there is no way to calculate by numbers of screens. We’ll do what we can with what we’ve got. In addition, venues without 3D tend to be one- or two-screen theaters in small towns. That 2D now brings in more than half the gross income for most 3D films is all the more impressive.)

Now for the list of films. There are interesting patterns here. First, the drop in 3D percentages came at about the time when the summer-movie season began, and with one exception is has proven surprisingly consistent, hovering in the 40-45% range. Second, the greater the gap between the percentage of income and the percentage of theaters, the less well 3D would presumably be performing for each release. Thus although Transformers: Dark of the Moon brought in a higher percentage of 3D income, it performed proportionately no better than, say, Rio. Third, as long as the percentage of income is less than the percentage of theaters, it should be the case that the average per theater for 2D showings should be higher than those for 3D—which is true for every film.

More theaters, fewer tickets

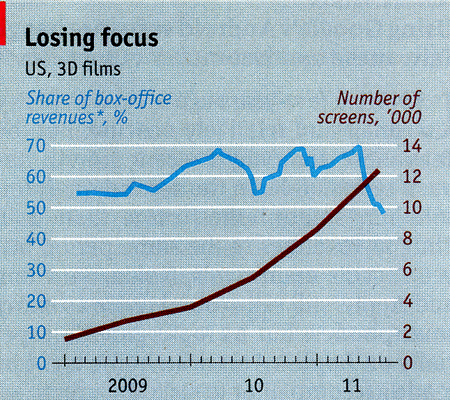

The decline in 3D’s contribution to film grosses has come despite the fact that the number of screens in the U.S. equipped to show 3D has gone up roughly six-fold since the beginning of 2009: from under 2,000 to over 12,000. Take a look at this graph from The Economist (derived from information supplied by BTIG Research and Screen Digest). The point where the lines cross is May, 2011:

Kvetching about 3D as a process and as a method of purse-gouging has declined somewhat, or at least that’s my impression. It’s not gone, though. Take a look at Mark Harris’ smart piece, “Honk If You’re Sick of 3-D!” in the June 24 Entertainment Weekly. Justin Chang’s Variety review of Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part 2, while generally very favorable, concludes: “D[irector of].p.[hotography] Eduardo Serra’s brooding, beautiful work gains little, however, from the underwhelming stereoscopic conversion; this is the first Potter film to be released entirely in 3D as well as 2D, and on this count, at least, one can be grateful that it will be the last.” “The “entirely in 3D” phrase refers to earlier episodes which have had a few scenes in 3D.)

Kvetching about 3D as a process and as a method of purse-gouging has declined somewhat, or at least that’s my impression. It’s not gone, though. Take a look at Mark Harris’ smart piece, “Honk If You’re Sick of 3-D!” in the June 24 Entertainment Weekly. Justin Chang’s Variety review of Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part 2, while generally very favorable, concludes: “D[irector of].p.[hotography] Eduardo Serra’s brooding, beautiful work gains little, however, from the underwhelming stereoscopic conversion; this is the first Potter film to be released entirely in 3D as well as 2D, and on this count, at least, one can be grateful that it will be the last.” “The “entirely in 3D” phrase refers to earlier episodes which have had a few scenes in 3D.)

There was also the controversy back in late May over whether 3D lenses, which notoriously cast dim images of 3D films, were being left on movie projectors for 2D screenings, thereby dimming the light getting to the screen for them as well. I don’t have the space to trace that discussion, but you can read about it in the original Boston Globe article, Roger Ebert’s indignant follow-up, and an expert projectionist’s assessment of the situation. Here the problems were being discussed largely in relation to 2D screenings.

But for quite some time now the larger 3D-equals-dim-images notion got wide coverage, and the topic had featured in many articles and postings critical of 3D. All that must have had some impact. In June Variety announced that for Transformers: Dark of the Moon Paramount would take “the unprecedented step of releasing a special digital print aimed at delivering almost twice the brightness of standard 3D projection.” These special prints, however, only went to about 2,000 theaters, those with RealD systems. But would prospective ticket purchasers know which cinemas had these prints? As Variety pointed out, “Exhibs may want to avoid planting the notion that some 3D screens are better than others when there’s no price distinction between the screens.” Given that it’s almost impossible these days to call a movie theater and ask a question, I doubt whether many moviegoers who attended Transformers knew which version they saw. Paramount’s move was obviously a desirable one, but it can’t account for the relatively high percentage of the film’s 3D income. (The New York Times also covered Michael Bay’s and Paramount’s efforts to promote screen brightness for the film.)

All in all, evidence seems to show that many theater owners are losing business by showing 3D films. Of Captain America’s total gross income, 40% came from the theaters showing 3D, which amounted to 68% of all venues (2511 locations out of 3715). Flip the figures, and the 32% of the theaters showing the film in 2D brought in 60% of the gross. On average, if you were an exhibitor playing the film, you made more money if you showed it in 2D. A lot more. Even not being able to charge $3 extra.

Box Office Mojo’s report on Captain America‘s first weekend confirmed that attendance was not dropping for the film as a whole, but that a greater proportion of people were opting for 2D: “While the gross difference was a sliver, Captain had eight percent greater estimated attendance than Thor, which received more bolstering from 3D (and had IMAX): Captain‘s 3D share was 40 percent at 2,511 3D locations, compared to Thor‘s 60 percent at 2,737.

Industry spokespeople are putting a good face on all this. Rob Moore, vice-chairman of Paramount, seized upon Transformers: Dark of the Moon’s 60% 3D opening-weekend share to boost the format to Variety: “‘There are so many 3D releases, audiences now are going to pick and choose which films to see in 3D,’ Moore said, before adding that the format has become a tool more for event filmmaking. ‘If the 3D is good, audiences are going to pay for it.'” But of course, most theater-goers don’t know whether the 3D is good until they have already paid for it. They go for other reasons, whether star, director, or genre. Or maybe it’s what their date or friends or family want to see. If it has those factors and it’s in 3D, it might seem worth the extra $3.

The opening weekend for Deathly Hallows might tend to confirm Moore’s claim, but the 3D share of the gross was still slightly below the percentage of 3D theaters, if not by much, and included an unusually large number of Imax locations (274)–which charge an even larger fee for 3D. Given the fans’ frenzy to see Deathly Hallows on its first weekend, they probably bought tickets for whichever screening they could, not much swayed by whether they would be seeing it in 3D or 2D.

Another point before I move on. Consider The Hangover Part II: $80 million dollars announced budget, $562.9 million worldwide gross and still in distribution. No 3D.

Anti-3D sentiment

Some people just don’t like 3D, supplement or no supplement. I went to some of the early releases to keep up with developments in the industry. It’s part of my job, after all. But after I got a sense of what it was like, I gave it up. I think the last 3D film I saw, apart from Werner Herzog’s wonderful Cave of Forgotten Dreams in February, was Avatar in December, 2009, and the one before that Up, in the summer of that year. I just saw Cars 2 the other day, 2D and on 35mm film, a treat that we must savor before release prints on film disappear over the next few years. By the way, Cave of Forgotten Dreams is the only exception to my new avoid-3D rule, and it also happens, proportionate to its budget, to be the most successful 3D film so far this year.

I’ve seen the two Pixar films made since Up only in 2D, and I don’t miss the 3D at all—despite the fact that Pixar’s films are probably the best that have been made during the latest vogue for 3D. Cars 2 naturally had quite a few shots with depth in the set design and staging. It occurred to me when I saw them that I actually might be getting a stronger sense of depth watching them in 2D than in 3D. The human mind has all sorts of ways of reading depth cues in a flat image. 3D tends to exploit only one of them, binocularity, which I suspect minimizes the others. I have no scientific evidence for that, just my own impression formed while watching the film.

I’m far from alone in avoiding 3D. The other day I participated in an online exchange on the subject. Sean Axmaker, contributor to the Parallax View website, wrote on his Facebook page that he had just seen Deathly Hallows 2 on film, in 2D and added, “I’d see “Captain America” here too, but it’s only in 3D and I just don’t see the need to see it with an extra pair of glasses on.”

The issue of studios and theaters switching entirely from 35mm release prints to digital projection would require a whole additional entry. But in late May Variety ran a long story, “Studios must revisit d-cinema,” with people from within the industry recounting dismal experience viewing both 3D and 2D films with digital projection. One 3D system cuts fully half the light from the projector. Cinematographer Roger Bailey is quoted: “It’s unbelievable that in an age when we think we have unbelievable technology, and the studios are talking about eliminating 35mm film prints in the next 18 months, that they haven’t begun to sort out the problems that have been caused by digital projection.”

The Economist ended its recent article, the one that contained the above graph, on a sour note:

Richard Gelfond, the boss of IMAX, reckons customers have become picky. “People used to see something just because it was in 3D,” he says. Now they ask how much pleasure the glasses will add. The explosive “Transformers 3” did well in 3D; perhaps the 2D version was not sufficiently headache-inducing. The key to three-dimensional projects, then, is to put out hugely popular films with extraordinary special effects. Easy.

Speaking of headaches, a small study conducted at the University of California-Berkeley seems to indicate that 3D glasses can cause eyestrain and discomfort. For those who want the full scientific text, it’s here. For a brief summary, go here. The main point is that the eyes naturally try to focus on the screen (the focal distance). The vergence point is where the imaginary lines going out from the 2 slightly separated 3D lenses come together. If it’s in front of or “behind” the screen, eyestrain can occur, since one is trying to focus on two different planes in depth simultaneously. The problem turns out to be worse the further you sit from the screen.

I myself have not noticed eyestrain or headaches caused by watching 3D movies with the current generation of glasses. I could imagine that since eyestrain is cumulative, those who watch large doses of television or spend hours at a 3D gaming console would have greater problems with the glasses.

Whether we want it or not

Business types seem to think people want 3D inserted into their lives. Note the 3D Webcam, pictured at the bottom. The accompanying text says, “The Minoru 3D Dual lens web camera is still at proof of concept stage atm but it can create stereoscopic 3D video which needs those cool blue and red 3D glasses to view.” (Note: “atm” means “at the moment,” not “go withdraw some money to buy one.”) I also ran across the 3D drawing pad pictured below left. It is available from the Perpetual Kid website, which explains: “Each page is a stereographic background for your writing or drawing. Put on these ultra cool (come on…you know you look good in them!) 3D specs and see your lines float above the page!” Why do people promoting such things seem to think that we can be convinced these glasses are cool?

Right now there’s a big push to sell 3D mobile phones and other handheld gadgets. On July 25, Roger Cheng posted a skeptical article on the subject of the Thrill 4G model, by LG:

Right now there’s a big push to sell 3D mobile phones and other handheld gadgets. On July 25, Roger Cheng posted a skeptical article on the subject of the Thrill 4G model, by LG:

But it’s unclear if consumers are ready to grab hold of it yet.

3D is the latest feature to be crammed in the increasingly Swiss Army-knife-like smartphone. Like with televisions, the feature is getting aggressive marketing support. But despite the marketing campaigns, the feature has been little more than a gimmick. And like 3D televisions, there’s been tepid interest.

“3D is just one of an onslaught of features that end up on a phone even if people don’t ask for it,” said Maribel Lopez, an analyst at Lopez Research.

Sam Biddell over on Gizmodo, did not hold back in commenting on the HTC Evo 3D phone:

The EVO 3D is the first phone to ever literally hurt my face. The 4.3-inch 3D screen’s glasses-free, of course, which means it uses the same auto-stereoscopic method as the Nintendo 3DS. Well, not the same—the 3DS is a joy to use and view, while looking at 3D stuff on the Evo felt like I was having my eyes gouged out, Oedipus-style. It gave me a headache. I wanted to look away. And for what? A 3D effect that just isn’t very good. To pull off a 3D picture of video that has any ‘pop’ whatsoever, you need to use framing so contrived as to render the whole thing pointless.

This, mind you, despite the fact that you don’t need glasses to see a 3D image on phones.

What’s next for theatrical 3d?

In my original “Has 3D already failed?” I wrote that it

depends on how one defines success. If you’re Jeffrey Katzenberg and want every theater in the world now showing 35mm films to convert to digital 3-D, then the answer is probably yes. That goal is unlikely to be met within the next few decades, by which time the equipment now being installed will almost certainly have been replaced by something else […] But it also seems possible that the powers that be will decide that 3-D has reached a saturation point, or nearly so. 3-D films are now a regular but very minority product in Hollywood. They justify their existence by bringing in more at the box-office than do 2-D versions of the same films. Maybe the films that wouldn’t really benefit from 3-D, like Julie & Julia, will continue to be made in 2-D. 3-D is an add-on to a digital projector, so theaters can remove it to show 2-D films. Or a multiplex might reserve two or three of its theaters for 3-D and use the rest for traditional screenings.

If for the rest of this year blockbuster films continue to bring in 40% of their gross revenues in 3D-equipped venues and those venues continue to be around 70% of the total locales, then I would think that the saturation point I mentioned has been exceeded. Some theater owners might decide that they could make more money with less hassle by showing 2D. That would drive 3D devotees to the reduced number of 3D houses, making their revenue go up. Which in turn would presumably make some of the exhibitors who had given up 3D go back to it, and the balancing act would continue until the precise saturation point is finally attained. But at this point, adding more 3D screens to a multiplex or converting a mom-and-pop theater in a small town would probably just worsen the problem. I think what I predicted is coming true, that multiplexes will reserve a small number of their screens for 3D and keep the rest flat. Maybe the studios will decide that $30 million is not a great investment.

The more important news is that digital projection will continue to spread. Some theaters have installed it already to save costs. Wanting to play 3D films (which mostly can only be shown digitally) has undoubtedly been a factor in exhibitors’ purchases of digital projectors, but it will probably become less so now. The studios, however, want to give up 35mm release prints, which cost a lot for both lab work and shipping. They’ll pressure the theaters until it finally happens.

Stifel Nicolaus analyst Ben Mogil downgraded box-office projections for the second half of the year and lowered his target for the company’s stock price to $27, from $32. His report came a week after similar predictions were made by Merriman Capital. The stock was trading at $25.33 late Monday.

“We believe that estimates for IMAX for [second half 2011] are too optimistic given that the [fourth quarter 2011] slate has three kids’ films, a genre which this year has seen considerably lower 3D share this year compared to last,” Mogil wrote.