Archive for the 'Movie theatres' Category

Has 3D already failed? The sequel, part 2: RealDsgusted

Kristin here–

For part 1, see here.

Darn those quickie conversions!

In past years, 3D proselytizer Jeffrey Katzenberg, head of Dreamworks Animation, has complained about the slow progress of the conversation of theaters to digital and 3D projection. By September, 2010, faced with a growing backlash against the technology, he was more concerned about the conversion of films shot in 2D to 3D. The 3D Hollywood in Hi Def site reported:

Jeffrey Katzenberg opened the 3D Entertainment Summit with his usual provocative verbal flare [sic], defending 3D successes against the recent growing tide of critics claiming it is already dying — “It seems there are some in Hollywood who are determined to seize defeat from the jaws of victory. Six of the top 10 movies this year are 3D; I guess we have to have 10 of 10.” — and lambasting filmmakers and studios who convert movies to 3D after they are produced in 2D, calling them “downright ugly” and claiming they are endangering the technology that is single-handedly responsible for the industry’s growth in the past year.

On the whole the media were hardly sympathetic, perhaps because Katzenberg has been largely responsible for making 3D–including those 3D-ized films–so profitable. Patrick Goldstein of the Los Angeles Times called his speech a “desperation plea” and gleefully linked to several anti-3D articles, including some of the ones I’ve linked to in this and last week’s entries.

What Katzenberg didn’t point out was that some of the six films in the top ten were the same retrofitted ones that he was attacking: Clash of the Titans and The Last Airbender. Alice in Wonderland was shot in 2D, but planned with the knowledge that it would be converted to 3D. (Gulliver’s Travels had not yet demonstrated that retrofitted 3D doesn’t always make for big domestic BO.)

Yet about a month later, in an interview with the New York Times, the other most influential figure in the push toward 3D, James Cameron, was discussing converting a film released in 1997 and not planned with 3D in mind: Titanic. (He plans to release it for the 100th anniversary of the ship’s 1912 sinking.) For Cameron, conversion is a problem when it is done hastily and carelessly. Of the retrofitting of Clash of the Titans he remarked, “It was just being applied like a layer, purely for profit motive.”

One problem with converting a 2D film to 3D comes from the fact that the process is far from an exact science (or art). Cameron commented on his search for a company to handle Titanic:

These conversions are so painstaking to complete correctly, Mr. Cameron said, because “there’s no magic-wand software solution for this.”

He added: “It really boils down to a human, in the loop, sitting and watching a screen, saying, ‘O.K., this guy is closer than that guy, this table is in front of that chair.’ ”

For his 3-D “Titanic” rerelease, Mr. Cameron said he had approached seven companies about working on the film, testing each by asking it to convert about a minute of movie footage before he chose the best two or three efforts.

“All seven of the vendors came back with a different idea of where they thought things were, spatially,” he said. “So it’s very subjective.”

He also points out that studios will inevitably search their vaults for films to convert.

How does 3D conversion work? An invaluable issue of Screen International, “European 3D Special 2010,” explains in terms reasonably comprehensible to the lay person:

While each company goes about it slightly differently, the requirements are broadly the same: the creation of a second identical version (to obtain a second eye view) and the isolation of foreground from background elements by rotoscoping, adding depth and then painting or animating in the gaps. “When you move an image in this way to create two views, the biggest problem is filling in and cleaning up the area left behind,” says Vision3 post-production supervisor Angus Cameron. (From “Conversion: 2D to 3D,” p. 9)

(This issue, by the way, shows that studios doing conversion are popping up in Europe as well as in the U.S.)

As Cameron’s statements and this description suggest, the process is a painstaking, lengthy one. Many in the industry praised Warner Bros.’ decision not to release Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows Part l in a 3D conversion. The studio cited insufficient time before the release date as its reason. Cameron remarked, “You can’t do conversion as part of a postproduction process on a big movie, because no one is willing to insert the two or three or four months necessary to do it well.” (Of course, some foes of 3D may have suspected that the real reason for Deathly Hallows I being released only in 2D may have been that WB saw the declining share of the box office going to 3D and decided it just wasn’t worth it.)

Graham Clark, the head of stereography for the Stereo D company, claims that the conversion process can be done well as long as enough time is allotted for it:

“The main thing is this is an artistic process,” he said of conversion. “Composing things in 3D space is every bit as artistic as composing things in 2D space.” […]

“Because there are so many factors that go into deciding how to compose a shot, you need interaction with the producer, director, cinematographer—so you are not, at the eleventh hour changing things,” he said. “Also, visual effects studios are used to handing off [VFX elements] at the eleventh hour. Conversion is new in the film pipeline, and people aren’t used to having to hand stuff off earlier.”

Clark points out some of the ways that conversion could be used to enhance a film. If a 3D camera can’t be fitted into a certain space, a shot can be done in 2D and converted. If after a scene is shot the filmmakers want to shift the spatial relations of elements within it, they can do so—eventually, at any rate, since the techniques for doing that are still being developed. As Clark points out, films shot in 3D usually have some shots that are converted. Even Avatar included some. (See Carolyn Giardina’s “The art of the 3D conversion,” The Hollywood Reporter, October 29, 2010, pp. 6, 87. The same article, retitled “Expert: The Biggest Challenge in 3D Conversion,” is available here for subscribers.)

Given that most effects-heavy films these days face a major crunch to make their release dates and have to employ multiple effects houses to do the job, a quality 3D conversion can only add to the headache. Not to mention more work for the conscientious director and cinematographer who have to sit in on the decision-making to prevent the quality of their work from being diminished.

All in all, it looks as though 3D will not die out completely. But will there come a time when every screen in the world’s major markets will have the capacity to show 3D films? That was Katzenberg and Cameron’s original ideal, or so they said. Others had the same vision. Katzenberg has committed Dreamworks Animation to making only 3D films. Does he plan eventually to eliminate 2D prints altogether? Cameron claimed he would do that with Avatar, but he had to give in on that one.

Maybe Katzenberg and Cameron would object that they didn’t mean that literally every screen would be 3D. Yet advocates for 3D often compare it to sound or color or widescreen, all processes which did fully penetrate theatrical exhibition. In major markets sound took about three years (though places like Japan and Russia still made a few silent films into the mid-1930s). Widescreen took about six years. The most apt comparison is perhaps color, which didn’t become really viable until the mid-1930s; it remained somewhat rare into the 1940s and didn’t really become dominant until the late 1960s. But in our era of fast-moving technology, perhaps three decades from now 3D, at least in its current form, requiring glasses, will be a dead technology.

In my first entry on 3D, I mentioned that not very many producers or directors have been proselytizing for the process nearly as much as Katzenberg and Cameron have. Lucas is converting the Star Wars series, but he doesn’t promote the process with the fervor he once devoted to digital cinematography and projection and Dolby sound. Spielberg’s first 3D film, The Adventures of Tintin: The Secret of the Unicorn, is coming out in December, but he’s not making the round of the trade fairs singing the praises of the process. The same is true of Scorsese and his 3D debut, Hugo Cabret, also coming in December.

Peter Jackson and Guillermo del Toro had originally stated that The Hobbit would be 2D, so as to keep a unified look alongside the Lord of the Rings trilogy. But when Warner Bros. finally greenlit the film in October of last year, the press release included the news that the two parts will be shot in 3D. Peter Jackson is a big booster of the Red brand digital cameras (used on The Lovely Bones and District 9), and he enthused briefly in the Red press release about using the new Epic 3D model for The Hobbit. His Weta Digital facility did most of the effects for Avatar. Still, he’s not out on the stump, urging theaters to convert and warning filmmakers not to retrofit their films, and many fans wonder whether Warner Bros. left him any choice in the matter of using 3D. (Vague statements have been made about the trilogy being released in 3D eventually, but there’s no firm news about that.)

Of course, assuming 3D is here to stay, there will always be bad conversions because there are bad instances of anything. There are shoddy-looking 2D movies and always have been. Still, the studios didn’t charge extra for them. There are and will be movies originally shot in 3D that are bad. People will have to pay extra for them, too, at least in the near future. Somehow, paying that premium 3D price seems to make people more indignant about bad movies than paying the regular price does. Studios are not likely to heed Katzenberg’s plea that they not crank out cheap 3D-izations. If such sloppy jobs as Clash of the Titans continue to come out and sour people on paying premiums, the studios may have to lower those premiums until they just cover the extra costs of production and of the glasses. If 3D ceases to generate any significant extra profit, will the studios bother with it?

Or will they take the more sensible approach that I mentioned at the beginning of the first part of this entry, settling for multiplexes converting two or three screens for 3D capacity and showing either special-event films like Avatar or cheap genre films like Piranha 3D? Part of that approach would include continuing to make 2D prints of films. There are quite a few viewers who would prefer that option.

At least one studio chief agrees. Last summer Home Media Magazine‘s article on Toy Story 3 reported: “Disney CEO Bob Iger, in a recent financial call, cautioned flooding the market in 3D releases, opting instead that earmarked titles in the format should be done strategically, and not as an afterthought.”

Before moving on to vociferous 3D opponents, I’ll mention a couple of intriguing, possibly significant things that I’ve noticed that may indicate a short life (or possibly a marginalized long life) for 3D.

First, on January 10, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences announced its scientific and technical awards. (Those are the ones that are given out at a separate ceremony and are given a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it acknowledgment during the Oscar ceremony.) These awards are often given for developments that occurred years earlier. On the other hand, major innovations tend to get honored fairly soon. The two technical awards given for special-effects programs for The Lord of the Rings were given in 2004, the same year that The Return of the King swept the Oscars.

This year’s awards include none relating to 3D. (For Variety subscribers, the complete list is here; so far they don’t seem to be listed on the Academy’s website.) Instead, they relate to such inventions as a new winch for flying heavy props like cars, a new suspended-camera mount, systems for queuing special effects for rendering, a method for facial-expression capture, and an innovative way of using bounce lighting in computer animation. Maybe it’s not significant, but it may give a clue as to the professional motion-picture technicians’ view of 3D.

Second, this past summer David and I were able to attend a trade demonstration at a local theater. The Technicolor firm had innovated a 3D add-on lens for 35mm projectors. Technicolor had seven Hollywood studios signed on, agreeing to provide analog 3D prints formatted in the system. (13 of the 19 films released in 3D in 2010, beginning with How to Train Your Dragon, were available on 35mm 3D prints.) The main appeal of the system was that distributors don’t buy it; they rent it by the year. The special silver screen needed for the technology would cost around $4000 to $6000 to install (and could be used for some digital 3D systems, including RealD), and the lens would be rented at $2000 per 3D film exhibited, with a maximum of $12,000 per year. In contrast, a digital 3D conversion costs at least $75,000 per house.

Some small-town exhibitors from the surrounding area were obviously intrigued. They couldn’t afford to convert to digital/3D, but this offered a cheaper option. Nobody mentioned it during the demo, but the other obvious implication seemed to be, if you just rent your equipment, you won’t lose out if the 3D craze fizzles out. The firm anticipated having over 500 systems installed in the U.S. by the end of 2010. (For a case of a theater in Decatur, Illinois that canceled its deal with Technicolor, see here; the management failed to understand that one has to charge higher admission for 3D tickets because the print rental fees and 3D system cost more, and the projectionist keeps referring to the 3D lens as a “camera.” On the whole, one can’t feel that in this case the Technicolor system itself was to blame. The 25 equipped screens out of the 150 in the Bow Tie Cinemas chain in California presumably have fared better.)

[Added later the same day: Skip Huston, who run Huston’s Avon Theater 3 in Decatur, tells me that the reporter was the one who called the lens a “camera.” (Knowing what it is to be misquoted by a reporter, I can well believe it.) The owners tried to avoid raising ticket prices for their customers, but that just doesn’t work with 3D. Mr. Huston’s theater is a mom-and-pop establishment competing with two Carmike multiplexes. Those wishing to avoid 3D have the option of 100% 2D at the Avon.]

Naysayers galore

The more I see of the process, the more I think of it as a way to charge extra for a dim picture.

Roger’s remark sums up the two beefs people have with 3D. Not surprisingly, when 3D was a novelty and only major films had it, people were willing to pay extra. Now that any multiplex will be likely to have one or two screens devoted to 3D movies at any given time, the premium has begun to seem onerous. And yes, the glasses do cut out a noticeable part of the light coming from the screen.

According to a report by PricewaterhouseCoopers (quoted in The Hollywood Reporter), “a $5 premium per ticket is too much to expect audiences to pay for 3D. That survey indicated that 77% of Americans will not pay a premium of more than $4.” In terms of the industry’s attitude, the report adds, “Many people are over-excited by it. The danger is that industry players risk killing a golden goose by overselling and, in some cases,  overpricing the 3D experience—and by providing too much mediocre content that doesn’t do justice to the technology.”

overpricing the 3D experience—and by providing too much mediocre content that doesn’t do justice to the technology.”

Putting aside the high price, there are those who actively dislike the process. Others admit that there are a few films that justify the use of 3D but that most films using the process released so far have been attempts on the parts of the studio to jack up the ticket prices. If these people are entertainment journalists, they use the forum of their reviews or columns to air their complaints. If they are ticket-buying audience members, they search out the 2D screens or stay home. Some of them blog about their complaints, others write letters to the editor, and others carp about 3D around the water cooler.

Roger Ebert probably has the highest profile of the anti-3D naysayers, as least among the general public. In an article in Newsweek (May 10), he laid out his objections:

3-D is a waste of a perfectly good dimension. Hollywood’s current crazy stampede toward it is suicidal. It adds nothing essential to the moviegoing experience. For some, it is an annoying distraction. For others, it creates nausea and headaches. It is driven largely to sell expensive projection equipment and add a $5 to $7.50 surcharge on already expensive movie tickets. Its image is noticeably darker than standard 2-D. It is unsuitable for grown-up films of any seriousness. It limits the freedom of directors to make films as they choose. For moviegoers in the PG-13 and R ranges, it only rarely provides an experience worth paying a premium for.

Roger goes through each of these reasons in more detail. He writes with conviction, and the studios would be wrong to think that he stands alone. I wonder how many other websites have linked to the online version of the essay. I see it quoted and linked a lot, even eight months after it appeared.

Movie City News critic David Poland, also far from being a fan of 3-D, recently posted an entry called “Will 2011 Be A 3D Car Wreck?” He assesses many of the roughly 30 3D films announced for this year. As he points out, similar films will be competing with each other during the key release seasons, as with Scorsese’s Hugo Cabret, the third in the “Chipmunks” franchise, and Spielberg’s Tintin movie, which are coming out within a short period. He concludes:

But the problem remains… 3D is a tool, not an answer. The problem that I expect next December, for instance, will be a parade of high quality films of a similar tone all piled up in on month. Same with the load of animation in November. And whichever films pay the price – and some films will – it won’t be 3D’s fault, but rather, overloading the marketplace. The franchises are franchises and the product that isn’t franchise will need to be sold smartly and heavily… just as in a world without any 3D at all.

This is an interesting variant on the view of 3D as a symptom of the film industry’s problems. Often popular commentaries link 3D mainly to the loss of audiences to TV, video games, and other new media sources of entertainment. But Poland sees the problem as more related to the increasing dependence on franchises and big event films. When other methods of luring patrons into theaters fails (Johnny Depp and Angelina Jolie together for the first time!), 3D remains a lure–except when it doesn’t, as with Gulliver’s Travels.

These days Entertainment Weekly seems to be mounting a campaign against 3D. Lisa Schwarzbaum makes no bones about her increasing disenchantment with the format. About a quarter of the prose in her December 15 review of The Chronicles of Narnia:Voyage of the Dawn Treader (C rating) is devoted to it:

And that includes the option of watching The Voyage of the Dawn Treader in undistinguished, unnecessary 3-D. I’m more and more frustrated these days by movies that sell the 3-D movie experience as a kind of turbo-charged event, yet the greatest extra we see through plastic movie-theater goggles is the ”dimensionality” of a sword or a boot or the imaginary fur on a CGI  mouse. I’m confounded by the fact that, aside from the Pevensie siblings and their nicely obnoxious cousin, absolutely everything and everyone aboard the Dawn Treader looks one-dimensional, no matter how closely I peer through special specs.

mouse. I’m confounded by the fact that, aside from the Pevensie siblings and their nicely obnoxious cousin, absolutely everything and everyone aboard the Dawn Treader looks one-dimensional, no matter how closely I peer through special specs.

It’s not just that one film, either. Schwarzbaum called Tangled (B rating) “Disney’s new (yet not quite novel), musical (yet not quite memorable), 3-D (yet so what) animated retelling of the Grimm brothers’ Rapunzel.” Of The Green Hornet (C-), she remarked, “In a last-minute tweak, the production has also been meaninglessly 3-d-ified–never mind that there’s nothing whatsoever 3-D-ish going on. Maybe those clumsy 3-D glasses are meant to let moviegoers mimic the superhero mask-wearing experience? At any rate, they let moviegoers pay more for a ticket.”

OK, she’s one critic. But note EW‘s back-page “Bullseye,” which shows what one or more people on the staff think of as recent hits and misses in the sphere of popular culture. For the week of November 11, , there was an arrow fairly close to the center with the caption: “Good news for 2012: Batman gets a title (The Dark Knight Rises). Better news for 2012: He won’t be rising in 3-D.” For the year-end Bullseye from the undated last issue of 2010, an arrow on the outer rim had a distinctly unsympathetic caption (see above). The January 21 issue places an arrow near the outer ring, labeled “All that talk of making The Great Gatsby in 3-D.”

Lest anyone think that EW has some hidden agenda in knocking 3D, we should note that the magazine belongs to Time Warner, whose Warner Bros. studio is deeply invested in the success of the format.

There’s also a great deal of anecdotal material about how parents are tired of paying multiple 3D surcharges when taking a whole family—and tired of finding that the kids won’t wear the glasses through the whole show. Dorothy Pomerantz is one parent with a soapbox from which to state her case, in the form of her “The Biz Blog” for Forbes. On July 13 she wrote:

We went to an 11 a.m. showing (for matinee prices) of Despicable Me and it cost us $41 for a family of four. If we had decided to see the film in 3-D, it would have cost us $55 for tickets alone. In my mind, that’s too much money.

For one thing, my kids are scared of the 3-D effects and wiggle so much in their seats it’s hard to tell if they’re seeing the image clearly at all (and my daughter has a very hard time wearing the glasses over her normal glasses for 90 minutes at a time). I find the glasses sit very uncomfortably on my face and that the movie image is often dim. For some reason my husband doesn’t see the 3-D well and ends up with a horrible headache.

People seem to think that children’s animation is ideal for 3D—but if a lot of young children don’t like the glasses or can’t keep them on, maybe that’s not true. (The image above right is not a warning against such problems but a promotional item for watching 3D Blu-ray on PlayStation 3. Apparently children will be seen and be heard.)

Apart from journalists, ticket-buyers are complaining. Back to EW, where the January 14 edition’s letters page (p. 10) had this from Courtney Holcomb of Grand Prairie, Texas:

I’ve read many articles discussing the trend that Avatar started … yet most of them miss a simple point. The film was available in both 3-D and standard formats. The customer had to decide “Do I want to see it in 3-D or not?” More recent 3-D movies have changed the question to “Is it worth it to see the movie in 3-D?” Many of the ones on the “Bad!” end of your “Ranking 3-D Movies” chart might have done better if the standard version had been available as well.

Actually the chart (see left) was by quality, not income, but Ms Holcomb’s point could apply to box-office hits and disasters alike. People who had no access to 2D versions of any film on the list might have decided to go. A friend of mine told me he didn’t see The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, despite wanting to, because it was only showing in 3D.

On the same letters page, Stephen Wohlleb of Sayville, New York, wrote:

While studio execs scurry to push out any film they can in 3-D, they must keep in mind that 3-D should be used to enhance the story, not replace it. The “other Avatar,” The Last Airbender, was so poorly received because story still comes first; 3-D does not a film make.

I have not ventured too far into the depths of chat rooms and comments on the internet for the purpose of writing this blog, but of course, there one can find vociferous pro and con statements on 3D.

I have a friend with vision problems and frequent headaches, and she actually finds the 3D glasses improve her viewing of films. That doesn’t seem to be common, though. Mostly the headaches and the kids-having-trouble-with-glasses complaints seem to be shared by many.

Industry commentators don’t seem to mention the novelty effect of 3D much any more. Surely they never really thought that audiences will be dazzled forever. I think we reached the ho-hum point some time last year. I’ve mentioned that people began to resent the $3+ price hikes and to pick and choose more carefully among 3D releases, wanting the movie to be good enough to warrant paying more. But others perhaps decided 3D in general wasn’t worth it and that they would rather see a film the old fashioned way, seeing a flat image undimmed by glasses.

For me it was Toy Story 3. In 2009, David and I saw Up in 3D and enjoyed it. But we enjoyed it because it was another great Pixar film. As I said in my 2009 entry, I have remembered the film in 2D. We went to Toy Story 3 in 2D and enjoyed it. I have yet to see a film in both 3D and 2D to make a comparison, but my suspicion is that I would usually prefer the 2D version. I suppose the basic problem is that if the 3D is used for flashy depth effects with things flying out at the audience, it becomes too distracting and obtrusive. But if it’s used simply to make, say, jungle plants look closer to the viewer than Carl and Russell, then it’s unobtrusive—and hence not very interesting. Given that we have other mental tools besides binocular vision for grasping the spatial relations in an image, the jungle plants look closer in 2D as well.

A final thought on disaffected audiences. Currently there is a sector of the moviegoing public that loves 3D, will pay extra to see almost anything in 3D, and hopes the process expands. That part of the public is probably as big as it’s going to get. (Yes, new kids will grow up, but others will mature out of their adolescent obsessions with such things.) In the U.S. at any rate, right now there aren’t a lot of people suddenly discovering the joys of this wonderful new format. (It’s really just getting going in the major Asian markets.) But the proportion of the getting fed up by the process’ drawbacks—its higher cost, the growing numbers of mediocre and bad films in 3D, the glasses—is probably growing.

Just in time for inclusion in this entry, Roger has posted a new article, “Why 3D doesn’t work and never will. Case closed.” It includes a letter from Walter Murch, who is about as well-respected an expert on film technology as you could find. The letter explains how 3D systems work in ways that are contrary to the ways that our eyes and brains actually function. He deals with strobing, the convergence/focus issue (“So 3D films require us to focus at one distance and converge at another.” That’s where people’s headaches come from in watching 3D movies.) Murch concludes: “So: dark, small, stroby, headache inducing, alienating. And expensive. The question is: how long will it take people to realize and get fed up?”

Perhaps not very long. I was expecting that in the wake of last week’s post I would receive indignant email and get flamed on message boards. So far I have seen no indignation. One thread on imdb that linked to the entry led to about ten comments, all expressing dislike of or indifference to 3D. Of course, that entry was on the “advantages of 3D” (such as they are) for the industry. Maybe this one will rouse more ire.

A 3D film even a naysayer can love

There’s one 3D film that even 3D disparagers eagerly want to see: Werner Herzog’s Cave of Forgotten Dreams. It’s the one where Herzog got exclusive access to film in the Chauvet cave, which contains one of the largest and oldest sets of prehistoric paintings. I would love to see the cave, but it isn’t open to the public. So naturally I would love to see Herzog’s film. (He’s not exactly a bad filmmaker, either, whatever the topic). It seems the perfect use for 3D: showing people exciting places they will never get to see on their own. I could imagine a similar film being made in the tomb of Sety I in the Valley of the Kings, a very deep tomb full of paintings considered among the best that survive from ancient Egypt. It will almost certainly never be open to the public either.

IFC acquired the film at the Toronto International Film Festival in September. They don’t seem to be trying to publicize it very much. No announcement on their site of when it’s going to be released, and the Google link to the official trailer comes up with a “Page not found.” I had to go to The Documentary Blog to find out that the release date is March 25, but the author had no information about how many theaters would get it in 3D. I should think IFC would make more of a big deal about this film as a real “event” movie. Maybe they will, closer to the release date. With operas and sporting events playing in multiplexes, I would think that there’s a considerable audience for 3D films that bring special events to a far-flung audience. Every kid whose imagine was kindled by learning about prehistoric cave paintings in school, every art lover, plus every cinephile, would attend Cave of Forgotten Dreams if it came to a theater near them.

Has 3D Already Failed? The sequel, part one: RealDlighted

Kristin here–

On August 28, 2009, I posted an entry called “Has 3-D Already Failed?” As I wrote then, my title was deliberately provocative. It depended on which of two yardsticks you measured success by:

1. If you’re Jeffrey Katzenberg and want every theater in the world now showing 35mm films to convert to digital 3-D, then the answer is probably yes. That goal is unlikely to be met within the next few decades, by which time the equipment now being installed will almost certainly have been replaced by something else.

2. It also seems possible that the powers that be will decide that 3-D has reached a saturation point, or nearly so. 3-D films are now a regular but very minority product in Hollywood. They justify their existence by bringing in more at the box-office than do 2-D versions of the same films. Maybe the films that wouldn’t really benefit from 3-D, like Julie & Julia, will continue to be made in 2-D. 3-D is an add-on to a digital projector, so theaters can remove it to show 2-D films. Or a multiplex might reserve two or three of its theaters for 3-D and use the rest for traditional screenings.

If the second, more modest goal is the one many Hollywood studios are aiming at, then no, 3-D hasn’t failed. But as for 3-D being the one technology that will “save” the movies from competition from games, iTunes, and TV, I remain skeptical.

So, nearly 17 months later, where do we stand? There has been a considerable increase in the number of screens with 3D projection systems, from 4,400 in May 2010 to 8,770 in early December. That’s out of roughly 38,000. This growth presumably came in response to the huge success of Avatar and Alice in Wonderland. Anne Thompson’s “Year-End Box Office Wrap 2010” quotes Don Harris, Paramount’s executive vice-president of distribution: “There are more screens, so a theater can now handle anywhere from two to three 3-D films at one time.” By year’s end, there were roughly 13,000 3D-equipped screens outside the North American market. The number of 3D films per year has grown from 2 in 2008 to 11 in 2009 to 22 in 2010 to an announced 30+ for this year.

Thompson also points out two other important strengths of 3D films: they sell a lot of tickets abroad, often earning three times as much as in the North American market, and they have led to theatrical income is “again the leading film revenue stream.” Of course, that’s partly due to the drop in DVD sales.

Yet for some the bloom seems to be off the rose. Low-budget exploitation films in 3D, films shot in 2D and converted for 3D release, filmgoer impatience with ticket surcharges and clunky glasses, and a general decline in the novelty value of 3D have all combined to leave its future still in doubt.

Before going more deeply into those problems, though, let’s look at the box-office successes, or apparent successes, of 3D films in 2010.

3D props up the box office

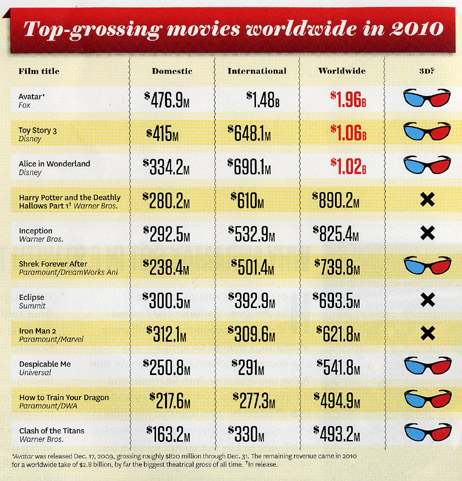

This week’s print version of The Hollywood Reporter heralds 2010 as “The year that was saved by 3D.” (For subscribers, the article is online, though it lacks the charts.) As Pamela McClintock, author of this excellent article, points out, “Of the top 20 films at the domestic box office, 11 were 3D titles (out of a total of 22 major 3D releases). Why the fat grosses? On average, a 3D title can expect to make 30 percent more because of the 30 percent upcharge for a 3D ticket.” (The accompanying chart, below, covers only the top 11 titles.)

(I will step in here and point out something that never seems to get mentioned in coverage of 3D, which is that part of that fee goes to pay for the glasses.)

Moreover, overseas markets, which have been making up an increasing portion of most big films’ worldwide grosses, are adding 3D screens like crazy. “The U.K., China, Russia, Japan, France, Germany, China and Russia in particular have seen a surge in digital-theater installations.” Given that the U.S. is still making more 3D films than most of these countries, Hollywood is getting a generous slice of that box-office income. Some films thought to be disappointments in the States did well worldwide, such as Clash of the Titans, with $493.2 million, and The Last Airbender, with $318.9 million.

Of course, there have been underperformers: Cats and Dogs: the Revenge of Kitty Galore, The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, and Gulliver’s Travels, most notably. McClintock points out, “It’s almost certain that Deathly Hallows would have jumped the $1 billion mark worldwide had it been released in 3D, but Warners didn’t want to tarnish the franchise.” As it is, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows Part 1 has grossed $937,257,461 worldwide and is still in distribution.

Another thing that McClintock points out that most commentators ignore is that making a film in 3D adds to its budget, on average about $20 million for a two-hour feature. The alternative practice of shooting a film in 2D and then converting it to 3D is common. That costs about $100,000 or more a minute, or about $12 million for a two-hour film. (James Cameron, who ought to know, says a quality job would be $15 million or more.) For a movie that grosses in the hundreds of millions, that’s pretty small, but it’s not insignificant for a more modest film.

Let’s think about that for a moment. Jeffrey Katzenberg and James Cameron may still expect that all films will someday be made in 3D. But, to take one example I’ve seen people use in recent months, do we really think The Kids Are All Right would be enhanced by 3D? Even if some people do, the film cost only around $4 million to make and grossed a little under $30 million worldwide. Would $20 million spent on 3D cause it to gross over $50 million to make up the difference?*

Or does it?

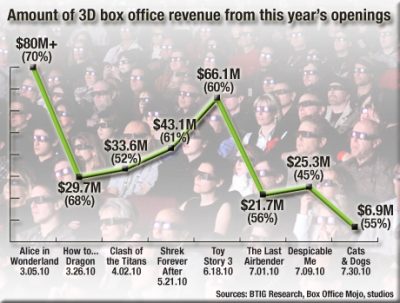

Despite the fact that 3D brought in higher grosses for the more successful films in that format last year, some experts are pointing to a decline in revenues over the year. In July of last year, Daniel Frankel published a widely cited chart called “The Rise & Fall of 3D” on The Wrap showing that since the release of Avatar the previous December, the proportion of the opening weekend box-office for major films coming from 3D screenings had declined:

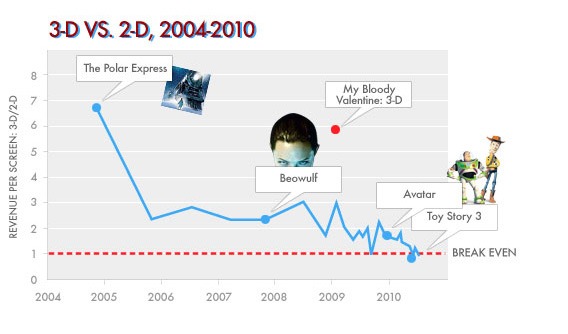

Then in August Slate posted a more detailed study by Daniel Engber bluntly entitled “Is 3-D Dead in the Water?” Engber took issue with Frankel’s chart saying that it did not reflect problems with a shortage of 3D screens available during the release of these films. But Engber didn’t disagree that 3D’s share of a film’s income has been falling. Quite the contrary, he thought it the decline was even greater. Taking a different approach that basically compares per-screen averages for 3D and 2D screening of the same film, he came up with a new chart:

The chart below—created with enormous help from Slate designer Holly Allen—shows the ratio of 3-D revenue to 2-D revenue, on a per-screen basis, for almost every major three-dimensional release going back to the beginning of the current revival.

Here’s the simplest way to interpret this graph: 3-D has been getting less and less profitable, relative to 2-D, over the past five years. It’s an ominous, downward trend that started long before Avatar and Alice in Wonderland and continued after. (The red dotted line represents a break-even point, where screenings in 3-D and 2-D theaters make exactly the same amount of money.)

(I can’t go into the details here, but Engber presents additional charts and information; it’s a must-read for anyone interested in 3D, pro or con.)

Last year the big complaint from Katzenberg and other 3D purveyors was that there weren’t enough theaters to screen all the films that were coming out in that format. Katzenberg is still not satisfied with the rate at which theaters are converting screens to 3D, but maybe exhibitors have realized that there is not as much future in it as they had been led to believe. Given that most multiplexes have two, three, or even four screens capable of showing 3D films, the rate of conversion is likely to slow, if it hasn’t already.

Toy Story 3‘s release seems to have marked the point where some industry analysts began to notice the downward trend in 3D revenues in comparison to 2D. Its opening offers an insight into whether the drop is real or just an apparent effect of too many 3D films vying for too few screens, as is so often claimed. Media financial analyst Richard Greenfield pointed out that the film’s percentage of revenue from 3D screens was 1% less than with Shrek Forever After (released May 21). Toy Story 3 had made 60% of its opening weekend box office on 3D screens, while Shrek Forever After (released May 21) had made 61% and Alice in Wonderland (March 5) had made 70%.

1% may not sound like a lot, but Toy Story 3 was released on the largest number of 3D screens of any film to that date. In that case, it could not be claimed that the drop resulted from too many 3D films jostling for screens. On the contrary, one would expect a rise.

Not only that, but Engber points out that the 2D versions of Toy Story 3 actually outperformed the 3D ones:

Then we come to the weekend of June 18, 2010, when Toy Story 3 opened in more than 4,000 theaters around the country. It was a huge weekend for the Pixar film—one of the biggest of all time, in fact, with more than $110 million in total revenue, and $66 million from 3-D. Yet a close look at the numbers shows something else: On average, Toy Story 3 pulled in $27,000 for every theater showing the movie in 3-D, and $28,000 for every one that showed it flat. In other words, the net effect of showing Woody, Buzz, and friends in full stereo depth was negative 5 percent. The format was losing money.

One could posit, of course, that the 2D screenings simply benefited from the overflow from sold-out 3D screenings. People who wanted to see the film in 3D had to settle. But that still doesn’t explain the drop in comparison to earlier films given the fact that Toy Story 3 opened on the largest number of 3D screens. At least two tickets to the film in 2D were sold to people who had the option of going to a 3D screening: David and me.

Engber goes on to consider some explanations for the decline, some of the same basic ones I’ll discuss here. He concludes that the situation is dire for 3D: “For mainstream movies that can be viewed in either format, the added benefit of screening in three dimensions is trending toward zero.”

Is 3D TV competing with theatrical or hurting it?

There seems to be an assumption that pop culture is headed toward a time when new media in general are delivered in 3D. The assumption is that 3D television will help boost sales of movies on DVD and Blu-ray. Maybe, but the sales of 3D TVs have been reported as lower than expected. According to a revealing article in Variety, Samsung projected that it would sell 3 million units in 2010 and sold less than 2 million: “According to several electronics makers, the biz will be concerned if the negativity continues six months from now.” Screen Digest’s year-end summary of 3D TV’s prospects (“After one year of 3D in the home,” December 2010 issue) points out that not only do 3D sets cost half again as much as 2D ones, but they are also mostly 44” or over, larger than most people can afford even in 2D sets.

That’s not the only cost holding back sales of sets. According to Variety: “The main reasons for holding out have been the pricey pairs of active-shutter glasses (sold for around $150 or more) that can be cumbersome to wear, easy to break and require batteries that run out. At the same time, there hasn’t been much 3D content to watch on the new sets.”

Sets with these active-shutter glasses come with one pair included. The things are bulky and require batteries. New 3D TV models are in the pipeline, some that work with lighter polarized glasses costing more like $20, with  four pairs included. As Bob Mayson president of consumer electronics for RealD (a major 3D theatrical supplier) told Variety, “You won’t have a Super Bowl party with active eyewear. With passive eyewear [i.e, those polarized glasses] you can buy a bag of glasses from Costco and be in business.”

four pairs included. As Bob Mayson president of consumer electronics for RealD (a major 3D theatrical supplier) told Variety, “You won’t have a Super Bowl party with active eyewear. With passive eyewear [i.e, those polarized glasses] you can buy a bag of glasses from Costco and be in business.”

Maybe guys who sit around drinking beer and watching the Super Bowl will get used to seeing each other wearing plastic glasses. Still, I have long been of the opinion that until 3D technology reaches a point where the glasses are unnecessary, the format can’t be universally viable. Toshiba and Sony have prototypes of such sets at technology fairs, but they reportedly won’t reach consumers for three to five years. I’m curious to know what the 3D effect will look like if you’re not sitting at exactly the right spot in front of the screen. From what I’ve read, you have to be positioned not only in front but also close. An excellent article in Wired summing up the obstacles to watching 3D on TV says the depth effect is limited to about four feet. In fact, there already are monitors for 3D without glasses (mainly available in Japan); they’re used mainly to display ads in stores. But in October Toshiba showed off two models intended for the home (left). The monitors are 12″ and 20″ and the optimum viewing distance is 90 cm for the larger monitor; that’s about three feet. They can project 3D to nine points in the room, but it sounds downright impossible for that many people to perch at precise points, all about a yard from the screen. Bigger versions will no doubt follow.

More content is coming for 3D TV, but again according to Variety, many content-providers are

focused on high-profile fare like sports and concerts, because as long as 3D TV requires glasses, it will only be used for event programming, not casual viewing. It may be tough to broadcast the Super Bowl in full 3D, outside of relying on a conversion, however, given that too many seats in the stadium would have to be removed for the 3D cameras. Networks could use robotic and remote-controlled 3D cameras but those are still too new of technologies to rely on yet.

Screen Digest ‘s year-end summary of 3D TV focuses on other obstacles, primarily the lack of content:

As recently as early September 2010 two thirds of the 21 3D BD [Blu-ray Disc] titles confirmed for US release in 2010 were tired to exclusive bundling deals with 3D hardware, leaving only seven available for purchase in store. By November, the total 3D BD slate had increased to 37 titles, 25 of which had been confirmed for retail sale by the year end. Furthermore, many of the biggest titles (including Avatar, the Shrek franchise, Monsters v Aliens, Ice Age 3) were still tied into exclusive bundles. By comparison, at the end of Blu-ray’s first year of availability (2006) 135 titles had been released on the format in the U.S.

I’m sure the brand partnerships between the TV makers and the studios have saved a lot in advertising, but it’s hard to imagine investing in a new technology when every time you want a popular film title, you have to buy a TV set to go with it. No doubt the availability of films to buy will increase, but the introductory approach seems a strange way to go about fostering interest in 3D movies on TV.

The Screen Digest article makes another interesting point. Initially, “3D in the home was conceived first and foremost as an attempt to mirror the revenues proven in the cinema—a 20 per cent premium over 2D features.” But much 3D TV content is also surprisingly like 2D TV content: “Ten percent of the cinema features have been dance or music, with a further four per cent including live sports and opera. This suggests an appetite for content that has traditionally been better suited to live television transmission than physical or cinematic tradition.” That further suggests that in the long run, people may be keener on 3D TV than on theatrical films in 3D—just the opposite of the studios’ hopes as they went in for 3D.

Beyond film and TV content, there is also the likelihood that 3D video-game playing through the large monitor will take up some of the time spent in front of the appliance. There’s also the fact that streaming or downloading 3D films requires far more bandwidth than 2D movies, though methods of compression are being developed.

The Screen Digest author predicts that by the end of 2014, 25% of American homes will have 3D TV. The question remains: What will people be watching?

Next week: Part two: RealDsgusted

*No doubt some cost-cutting is possible. Still, Tsui Hark’s Flying Swords of Dragon Inn (announced for a 2011 release), shot with the relatively inexpensive Red 3D digital camera, is budgeted at approximately $35 million. The difference between that and his usual cost per film could easily include $15-20 million for 3D. See Filmsmash for information and numerous photos derived from Chinese sites; the latter include images of the camera and of shooting in front of a green screen.

By Sam Spratt at Gizmodo

The buddy system

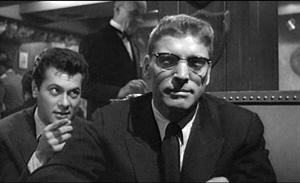

Sweet Smell of Success.

DB here:

Many of our friends write books, and what are friends for if not occasionally to promote each other’s books? Here’s an armload of titles, most of them recently published. They’re so good that even if the authors weren’t our friends and colleagues, I’d still recommend them.

James Naremore has made major contributions to film studies since his fine monograph on Psycho, published way back in 1973. That book remains one of the most sensitive analyses of this much-discussed movie. Now he has another monograph, on the stealth classic Sweet Smell of Success. When I was coming up, Alexander Mackendrick wasn’t much appreciated, and this movie slipped under the radar. More recently it has emerged as one of the model films of the 1950s, and not just for James Wong Howe’s spectacular location cinematography. It’s a very brutal story, with Tony Curtis playing against type as venal press agent Sidney Falco and Burt Lancaster as J. J. Hunsecker, a monstrously vindictive newspaper columnist.

Jim’s book provides a scene-by-scene commentary but also more general analysis of production circumstances and directorial technique. An enlightening instance is what Mackendrick called “the ricochet”—when character A talks to character B but is aiming at character C. This allows the filmmaker great flexibility in framing and cutting, often showing C’s reactions while we hear the dialogue offscreen. In the shots surmounting this blog, Sidney is needling J. J. by asking the Senator if he approves of capital punishment. Jim’s book joins his work on Welles, Kubrick, and film noir as part of a subtle reassessment of American postwar cinema.

With the current revival of interest in André Bazin’s film theory, it’s fruitful to look again at the “classical” theoretical tradition in which he participated. “Classical” here refers to the very long period before the emergence of semiotic and psychoanalytic theories of cinema in the 1960s. The newer theories have somewhat beclouded our recognition of how imaginative and wide-ranging the old folks were. In Doubting Vision: Film and the Revelationist Tradition, Malcolm Turvey scrutinizes four thinkers who saw film as having the power to show us things beyond (or above, or below) surface reality. In the spirit of analytic philosophy, Turvey carefully lays out the positions of Béla Balázs, Jean Epstein, Siegfried Kracauer, and Dziga Vertov before asking whether their claims hold up.

With the current revival of interest in André Bazin’s film theory, it’s fruitful to look again at the “classical” theoretical tradition in which he participated. “Classical” here refers to the very long period before the emergence of semiotic and psychoanalytic theories of cinema in the 1960s. The newer theories have somewhat beclouded our recognition of how imaginative and wide-ranging the old folks were. In Doubting Vision: Film and the Revelationist Tradition, Malcolm Turvey scrutinizes four thinkers who saw film as having the power to show us things beyond (or above, or below) surface reality. In the spirit of analytic philosophy, Turvey carefully lays out the positions of Béla Balázs, Jean Epstein, Siegfried Kracauer, and Dziga Vertov before asking whether their claims hold up.

I’m not giving much away by revealing that Malcolm thinks the revelationist tendency has its problems. But his purpose isn’t simply to reject the position. He treats it as an instance of what he calls “visual skepticism,” the idea that we ought to treat our ordinary intake of the world as something suspect. This idea, Malcolm argues, is central to modernism in the visual arts. He extends his critique of visual skepticism to more recent theorists as well, notably Gilles Deleuze, and he shows how his own ideas apply to films by Hitchcock, Brakhage, and other directors. Malcolm’s book is a model of theoretical clarity and probity, and a stimulating read as well.

Skepticism of another sort is central to Carl Plantinga’s Rhetoric and Representation in Nonfiction Film. One result of semiotic theory was to question whether a film could ever adequately represent reality. If a movie is only an assembly, however complex, of conventional signs, it can’t give us access to something out there. Even a documentary, some theorists argued, had no privileged access to the real world, let alone to general truths. “Every film is a fiction film” was a refrain often heard at the time. Carl tackles this assumption head-on by carefully arguing that just because a documentary is selective, or biased, or rhetorical, that doesn’t mean that it can’t affirm true propositions about our social lives.

Like Malcolm, Carl brings a philosopher’s training in conceptual analysis to debates about the ultimate objectivity of any documentary. In adopting a position of “critical realism” opposed to skepticism, Carl examines the realistic status of images and sounds, the way documentaries are structured, and filmmakers’ use of technique. He shows, convincingly to my mind, that a documentary may offer an opinion and still be objective and reliable to a significant degree. Carl’s 1997 book went out of print before it could be published in paperback. He has enterprisingly reissued it as a print-on-demand volume, and it’s available here.

To take film theory in another direction, there’s Evolution, Literature, and Film, edited by Brian Boyd, Joseph Carroll, and Jonathan Gottschall. As a wider audience has become aware of the power of neo-Darwinian thinking, more and more scholars have been arguing that evolutionary theory can shed light on aesthetics. The most visible effort recently is Denis Dutton’s The Art Instinct.

To take film theory in another direction, there’s Evolution, Literature, and Film, edited by Brian Boyd, Joseph Carroll, and Jonathan Gottschall. As a wider audience has become aware of the power of neo-Darwinian thinking, more and more scholars have been arguing that evolutionary theory can shed light on aesthetics. The most visible effort recently is Denis Dutton’s The Art Instinct.

For some years Brian, Joe, and Jonathan have been in the forefront of this trend, with many books and articles to their credit. Their anthology pulls together broad essays on biology, evolutionary psychology, and cultural evolution before turning to art as a whole and then focusing on literature and cinema. There are also pieces displaying evolutionary interpretations of particular works, and a finale that provides examples of quantitative studies of genre, gender variation, and sexuality, including an article called “Slash Fiction and Human Mating Psychology.”

Among the film contributors are other friends like Joe Anderson, a pioneer in this domain with his 1996 book The Reality of Illusion, and Murray Smith, who provides an acute piece called “Darwin and the Directors: Film, Emotion, and the Face in the Age of Evolution.” There are also essays of mine, drawn from Poetics of Cinema. In all, this book presents a persuasive case for an empirical, broadly naturalistic approach to the arts.

By the way, the same team is involved with an annual, The Evolutionary Review, edited by Alice Andrews and Joe Carroll. Its first issue offers articles on Facebook, musical chills, women as erotic objects in film, and Art Spigelman’s In the Shadow of No Towers (by Brian Boyd).

Some books emerge from conferences, and Tom Paulus and Rob King’s Slapstick Comedy is a good instance. Based on “(Another) Slapstick Symposium,” held at the Royal Film Archive of Belgium in 2006, the anthology brings together a host of experts who look back at madcap comedy in American silent film. There are essays on particular creators—Griffith, Sennett, Fatty, and Chaplin, inevitably—as well as pieces on slapstick parodies of other movies and the genre’s relation to modernity, also inevitably. Tom Gunning offers a fine analysis of Lloyd’s Get Out and Get Under (1920), concentrating on a complex string of gags around an automobile. The collection gathers work by some of the outstanding scholars of silent film while also, of course, making you want to see these crazy movies again.

You also want to see all the movies lovingly evoked by Gary Giddins in Warning Shadows: Home Alone with Classic Cinema. As indicated in another blog entry, I find Giddins one of the best appreciative critics we’ve ever had. Any essay, indeed almost any sentence, cries out to be quoted. Here he is on Edward G. Robinson:

You also want to see all the movies lovingly evoked by Gary Giddins in Warning Shadows: Home Alone with Classic Cinema. As indicated in another blog entry, I find Giddins one of the best appreciative critics we’ve ever had. Any essay, indeed almost any sentence, cries out to be quoted. Here he is on Edward G. Robinson:

His round, thick-lipped, putty face could brighten like paternal sunshine or shut down in implacable contempt or stall with crafty desperation or pontificate with ingenuous wisdom; his short, stumpy, erect frame could sport a tailor-made as smartly as Cary Grant.

Some of the pieces in Giddins’ latest collection were designed to accompany DVDs, but they will outlast this evaporation-prone genre. Other reviews come from the New York Sun, which gave him freedom to mix and match his subjects: Young Mr. Lincoln and Lust for Life (both biopics), Lady and the Tramp and Miyazaki movies. The collection opens with Giddins’ thoughts on how changes in film exhibition, from nickelodeons to digital screens, have altered our relationship with the movies. This isn’t just nostalgia, because his survey allows him to celebrate the power of DVD to exhume forgotten titles. The standards for a film classic, he notes, “are gentler and more flexible” than those in appraising other arts. “The passing decades are a boon to the appreciation of stylistic nuance that gives certain melodramas and genre pieces the heft of individuality.”

Who was Segundo de Chomón? In the 1970s, I kept finding that films I thought were by Méliès turned out to bear this mysterious signature. You imagine a man in a cape and a floppy hat. Photographs show someone a little less operatic, but with a superb mustache. Today he’s far from a mystery, although many of his movies can’t be fully identified. Several scholars have followed his trail, none more thoroughly than Joan M. Minguet Batllori in Segundo de Chomón: The Cinema of Fascination.

Chomón started as a cinema man-of-all-work in Barcelona, translating film titles, distributing copies, and producing films for Pathé. After moving to Paris in 1905, he continued working for the company and established his fame with trick films. He returned to Barcelona to create a production company, but that failed. On he went to Italy, where he specialized in visual effects, most famously for Cabiria (1914).

In his Parisian Pathé years, he was in charge of all the studio’s trick films, which included not only stop-motion, superimpositions, and other effects but also marionettes and animation. Joan argues that he was a prime exponent of the “cinema of attractions,” Tom Gunning’s term for that early mode of filmmaking which aims to startle and enchant the audience. A famous instance is Kiriki, acrobats japonais (1907), which shows gravity-defying stunts.

Chomón accomplished this by shooting from straight down, filming the performers on the floor. They had to simulate leaps and flips as they rolled along each other’s bodies, and then they had to slip perfectly into position. This English edition of Joan’s book on Chomón, full of information and providing a “provisional filmography” along with many pages of gorgeous color images, will be available soon here.

We recently noted the anniversary of our book on classic studio cinema, a 1985 project in which we bypassed talking about exhibition. That part of the industry has been a scholarly growth area in the years since, and one of the newest yields is Epics, Spectacles, and Blockbusters: A Hollywood History, by Sheldon Hall and Steve Neale. It’s a chronological account of Big Movies, from the earliest features to the digital era, and it concentrates on how such films have been marketed and shown. It explains how exhibition changed across the decades, and how we got the phenomenon of the “roadshow” movie, the film shown selectively (only certain cities), at intervals (perhaps only one matinee and one evening screening), and at more or less fixed prices. My middle-aged readers will remember roadshow releases like The Sound of Music (1965), although there were many before and even a few since.

We recently noted the anniversary of our book on classic studio cinema, a 1985 project in which we bypassed talking about exhibition. That part of the industry has been a scholarly growth area in the years since, and one of the newest yields is Epics, Spectacles, and Blockbusters: A Hollywood History, by Sheldon Hall and Steve Neale. It’s a chronological account of Big Movies, from the earliest features to the digital era, and it concentrates on how such films have been marketed and shown. It explains how exhibition changed across the decades, and how we got the phenomenon of the “roadshow” movie, the film shown selectively (only certain cities), at intervals (perhaps only one matinee and one evening screening), and at more or less fixed prices. My middle-aged readers will remember roadshow releases like The Sound of Music (1965), although there were many before and even a few since.

Sheldon and Steve trace in unprecedented detail the cycles of blockbusters that have run throughout American cinema. In the process they refreshingly redefine the very idea. We don’t usually think of The Best Years of Our Lives as a Big Movie, but it runs three hours and was considered a “special” production, comparable to the more obvious sprawl of Duel in the Sun. The authors bring the story up to date by considering today’s event movies as a “Cinema of Spectacular Situations.” Yes, that category includes comic-book films, Inception, and, of course, the 3D sagas that may finally be wearing out their welcome. (My editorializing, not theirs.)

Japanese cinema is endlessly fascinating in all its eras; I’d argue that in toto it’s one of the three greatest national cinemas in film history. The postwar period is exceptionally interesting because of the American occupation (1945-1951) and its effects on Japanese film culture. This period has already provoked one of the best books we have on Japanese cinema, Kyoko Hirano’s Mr. Smith Goes to Tokyo, and it finds a worthy accompaniment in Hiroshi Kitamura’s Screening Enlightenment: Hollywood and the Cultural Reconstruction of Defeated Japan. Kyoko focused on how US policy shaped domestic filmmaking, while Hiroshi asks how the Occupation helped American studios penetrate the local market.

Over six hundred Hollywood movies poured into Japan during the period, and Hiroshi traces how local tastemakers as well as U.S. policymakers drew audiences to them. Young Japanese learned about the Academy Awards, assembled in movie-study clubs to discuss what they were seeing, and were urged to consider even a gangster tale like Cry of the City (1950) as demonstrating the humanistic side of democracy. A center of this activity was Eiga no tomo (“Friends of the Movies”), a magazine that went beyond entertainment news and tried to reshape the tastes of young people. In sharp prose and vivid evidence, Hiroshi captures the ways in which American cinema promised to help heal a devastated country.

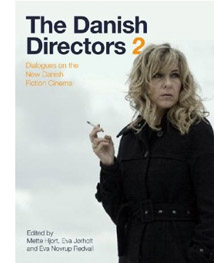

The Danish Directors, by Mette Hjort and Ib Bondebjerg, has become a standard companion to the most successful “small cinema” on the European scene. Now it has a successor in The Danish Directors 2: Dialogues on the New Danish Fictional Cinema, edited by Mette, Eva Jorholt, and Eva Novrup Redvall. Once again, we get lengthy, in-depth interviews covering the value of film education, the vagaries of funding, and filmmakers’ creative decision-making. Lone Scherfig, Christoffer Boe, Per Fly, Paprika Steen, and many other major figures are included. (Disclosure: The editors were kind enough to dedicate the book to me.)

The Danish Directors, by Mette Hjort and Ib Bondebjerg, has become a standard companion to the most successful “small cinema” on the European scene. Now it has a successor in The Danish Directors 2: Dialogues on the New Danish Fictional Cinema, edited by Mette, Eva Jorholt, and Eva Novrup Redvall. Once again, we get lengthy, in-depth interviews covering the value of film education, the vagaries of funding, and filmmakers’ creative decision-making. Lone Scherfig, Christoffer Boe, Per Fly, Paprika Steen, and many other major figures are included. (Disclosure: The editors were kind enough to dedicate the book to me.)

While the first volume is a rich storehouse of information on Danish film in “the Dogma era,” the newest volume shows how directors (some of whom made Dogma projects) have gone beyond it. In preparing 1:1, a film about Danes and Arab immigrants living in a housing project, Annette K. Olesen had a full script but concealed it from the non-professional cast. After getting the performers comfortable with ordinary situations, she began staging scenes while encouraging improvisation. Screenwriter Kim Fupz Aakeson incorporated the improvised material into revisions of the script.

By contrast, the prolific director-screenwriter Anders Thomas Jensen (Adam’s Apples, The Green Butchers), relies on strong structure, with lean expositions and sharply defined climaxes. He appreciates clean filming technique too.

It’s easy to make something that’s ugly and handheld, but you have to take telling stories with images seriously. You have to take the language of film seriously. Many Danish directors have started doing this in recent years and it’s wonderful, because there was a time when everything looked Dogma-like and I found myself thinking, “It’s got to stop now.”

To those who think that Danish cinema is at risk of becoming a cinema of cozy liberal reassurance, this collection offers many salutary signs. Every director speaks of the need to keep innovating, to push ahead provocatively. Simon Staho, whose Day and Night seems to me one of the most adventurous Danish films of recent years, aims at utter purity: “My task is to figure out how to add as little as possible to the black screen. The damned problem is that you have to add image and sound!”

What makes all these books exciting to me is a willingness to test ideas–sometimes very general ones–about cinema and the wider world by examining film as a distinctive art form. Even the most conceptual books on this week’s shelf are firmly rooted in the particular choices that creators make and the concrete ways that viewers respond.

Next stop: Vancouver International Film Festival. Whoopee!

Day and Night.

It takes all kinds

Kristin here—

How many directors are there whose bad reviews just make you more eager to see their new films? I’m not at Cannes and haven’t seen Jean-Luc Godard’s Film socialisme. But I’ve read some negative reviews, mainly those by Roger Ebert and Todd McCarthy. Now I’m really hoping that Film socialisme shows up at the Vancouver International Film Festival this year. (Please, Mr. Franey? I promise to blog about it.)

As you can tell from my writings, I’m no pointy-headed intellectual who won’t watch anything without subtitles. I love much of Godard’s work and have analyzed two films from early in what a lot of people see as his late, obscurantist period (Tout va bien and Sauve qui peut (la vie) in Breaking the Glass Armor). But I also love popular cinema. If I made a top-ten-films list for 1982, both Mad Max II (aka The Road Warrior) and Passion (left and below) would be on it.

Of course, those are old films by most people’s standards. Godard’s films have gotten much more opaque since I wrote those essays. I wouldn’t dare to write about King Lear or Hélas pour moi. That’s partly because I don’t speak French, though a French friend of ours has assured us that that doesn’t help much. Here Godard thwarts the non-French-speaker further by not translating the dialogue. Variety‘s Jordan Mintzer describes the subtitles that appear in the film: “To add fuel to the fire, the English subtitles of “Film Socialism” do not perform their normal duties: Rather than translating the dialogue, they’re works of art in themselves, truncating or abstracting what’s spoken onscreen into the helmer’s infamous word assemblies (for example, “Do you want my opinion?” becomes “Aids Tools,” while a discussion about history and race is transformed into “German Jew Black”).” Mintzer’s review provides a long description of the film; he mentions how baffling it is but doesn’t offer any real value judgments on it. Like other reviews, though, it piques my interest in the film.

Since Godard has increasingly moved into video essays, I’ve not kept as close track of him. But I always look forward to seeing his occasional new features on the big screen. The man has a mysterious knack for making beautiful images out of the mundane. How could a shot of a distant airplane leaving a jet-trail across a blue sky be dramatic? Godard manages it in the first shot of Passion. (I won’t show a frame from that shot, since it depends on the passage of time for its effect.) His soundtracks are dense and playful. Every few years the man cobbles together an incomprehensible plot based on rather tired political ideas and turns out something so visually striking that it might as well be an experimental film. I’m willing to watch and listen hard without assuming that I’m obliged to strain to find a message. McCarthy comments, “More personally, I have become increasingly convinced that this is not a man whose views on anything do I want to take seriously. […]” Did we take his views all that seriously back when he was a Maoist? I didn’t, but La Chinoise is a terrific film.

That’s not my point, though. As Ebert’s and McCarthy’s reviews both mention there are devotees of Godard who will most likely enjoy and defend Film socialisme. Ebert: “I have not the slightest doubt it will all be explained by some of his defenders, or should I say disciples.” McCarthy says that Godard is one of an “ivory tower group whose work regularly turns up at festivals, is received with enthusiasm by the usual suspects and then is promptly ignored by everyone other than an easily identifiable inner circle of European and American acolytes.” (McCarthy’s review is entitled “Band of Insiders.”)

I’m not sure what’s wrong with being devoted to Godard, even to the point of defending films that may be obscure or even maddening. I personally haven’t enjoyed his more recent theatrical releases like Forever Mozart and Éloge pour l’amour as much as his earlier work, but they’re still better than most Hollywood, independent, and foreign art-house films. The man is pushing 80 and not likely to change, so live and let us acolytes live.

Not coming to a theater remotely near you

I’m not here to defend Godard—not yet, anyway. But on May 19, Roger posted an essay calling for more “Real Movies” to be made, essentially narratives based on psychologically intriguing characters in situations with which we can empathize. He doesn’t say so, but I suspect this idea was inspired in part by his reaction to Film socialisme. His examples of real movies are some of the films he’s enjoyed this year at Cannes. I haven’t seen those, either, but I’ve read enough of Roger’s writings and been to Ebertfest often enough to know he loves U. S. indie films like Frozen River and Goodbye Solo. Excellent films with fascinating characters, but they and most of the foreign-language films that get released in the U.S. play mostly at festivals and in art-houses, both of which tend to be confined to cities and college towns. I’m sure that such character-driven films would be more likely than Film socialisme to get booked into art-houses, but they wouldn’t wean Hollywood from its tentpole ways.

Even the films that play festivals and arouse great emotion and admiration in the audiences will seldom break through into the mainstream. There simply aren’t enough of those art-houses.

As with many of Roger’s posts, “A Campaign for Real Movies” has aroused comments from people complaining about the lack of an art-house within driving distance of where they live. Jeremy Chapman remarked:

But Roger, if they did that (“Real Movies”), then I’d return to the cinema. And those in charge of the movie industry have proven again and again that they don’t wish to see me there. They’d rather show regurgitated nonsense to people so desperate for some distraction from their lives that they’ll go even though they know that they’re watching rubbish.

If any of these films you mention play nearby, then I shall see them. But they won’t. Instead I’ll have the option of Avatar II or some remake of a movie that was quite good enough (or not) the first time it was made. I love the movies, but I’m so over the movie industry (at least in the US).

Talking to regulars at Ebertfest, one hears time and again that some of them journey across several states to have a quick, intense immersion in films that haven’t played near their homes. Similarly, many who post comments on Roger’s essays refer to having been limited to seeing indie and foreign films on DVDs or downloads from Netflix.

I completely sympathize with that problem. Even with Sundance’s six-screen multiplex and the University of Wisconsin’s Cinematheque series and Wisconsin Film Festival, most of the movies David and I see at events like Vancouver or Hong Kong don’t play here. Sundance has to book pop films on some of its screens to allow them to bring art films to the others. Right now Iron Man 2 and Sex in the City 2 are playing there, alongside The Secret in Their Eyes and Letters to Juliet. If that’s what it takes to keep the place going, then so be it.

I completely sympathize with that problem. Even with Sundance’s six-screen multiplex and the University of Wisconsin’s Cinematheque series and Wisconsin Film Festival, most of the movies David and I see at events like Vancouver or Hong Kong don’t play here. Sundance has to book pop films on some of its screens to allow them to bring art films to the others. Right now Iron Man 2 and Sex in the City 2 are playing there, alongside The Secret in Their Eyes and Letters to Juliet. If that’s what it takes to keep the place going, then so be it.

However much people decry the crassness of Hollywood—and there’s plenty of it to go around—or denounce audiences who only go to the latest CGI spectacle, the simple fact is that the market rules. Indeed, if there were a truly free market, we probably would see far fewer indie and foreign-language films. Film festivals are supported largely by sponsors, and the films they show are often wholly or partially subsidized by national governments. The festival circuit has long since become the primary market for a range of films that otherwise never reach audiences.

That may sound terrible to some, but consider the other arts. Some presses only publish books they hope will be best-sellers, while poetry and other specialist literature is relegated to small presses whose output doesn’t show up in Barnes & Noble. That’s very unlikely to change. Amazon and other online sales have been a shot in the arm for small presses, just as Netflix has made it far easier for people to see films they probably would not otherwise have access to. (Our plumber told me the other day that he had been watching a bunch of recent German films downloaded from Netflix. Well, that’s Madison, as we say; high educational level per capita. But most people have the same option, if they wish.)

Art-houses are scarce in small cities and towns, but such places are not likely to have opera houses either, or galleries with shows of major modern artists, or bookstores which offer 125,000 titles. (As I recall, that’s what Borders claimed to have when it first opened in Madison. Now they seem to be working on that many varieties of coffee.) Opera or ballet lovers are used to traveling to cities where they can see productions, and serious Wagner buffs aim to make the pilgrimage to Bayreuth at least once in their lives.

David and I are lucky. It’s vital to our work to keep up on world cinema, so now and then we travel to festivals and wallow in movies for a week or two. Quite a few civilians plan their vacations around such events, too. We’ve run into people in Vancouver who say they save up days off and take them during the festival. Naturally not everyone can do that, but not everybody can see the current Matisse exhibition in Chicago (closes June 20) or the recent lauded production of Shostakovich’s eccentric opera The Nose at the Metropolitan. I really wish I had seen The Nose, but I don’t really expect the production to play the Overture Center here.

To some people, film festivals might sound like rare events that inevitably take place far away, like the south of France. Those are the festivals that lure in the stars and get widespread coverage. But there are thousands of lesser-known festivals around the world, dedicated to every genre and length and nationality of cinema. For those who like to see old movies on the big screen, Italy offers two such festivals, Le Giornate del Cinema Muto (silent cinema) and Il Cinema Ritrovato (restored prints and retrospectives from nearly the entire span of cinema history; this year’s schedule should be posted soon). Last month in Los Angeles, Turner Classic Movies successfully launched its own festival of, yes, the classics. Ebertfest itself began with the laudable goal of bringing undeservedly overlooked films to small-city audiences, specifically Urbana-Champaign, Illinois. It was and is a great idea, and it would be wonderful if more towns in “fly-over country” had such festivals.

The films we don’t see

Usually when someone calls for more support of independent or foreign films, there seems to be an implicit assumption that all those films are deserving of support, invariably more so than Hollywood crowd-pleasers. If a filmmaker wants to make a film, he or she should be able to, right? But proportionately, there must be as many bad indie films as bad Hollywood films. Maybe more, because there are always lots of first-time filmmakers willing to max out their credit cards or put pressure on friends and relatives to “invest” in their project. There’s also far less of a barrier to entry, especially in the age of DYI technology.

True, the indie films we see seem better. By the time most of us see an indie film in an art cinema, it has been through a pitiless winnowing process. Sundance and other festivals reject all but a relatively small number of submitted films. A small number of those get picked up by a significant distributor. A small number of those are successful enough in the New York and LA markets to get booked into the art-house circuit and reach places like Madison. Yes, some worthy films get far less exposure than they deserve. But many more films that would give indies a bad name mercifully get relegated to direct-to-DVD, late-night cable, or worse. On the other hand, most mainstream films, no matter how dire their quality, get released to theaters. Their budgets are just too big to allow their producers to quietly slip them into the vault and forget about them.