Archive for the 'Movie theatres' Category

Picks from the pile

Or rather, two piles. One stack of consumer durables that I brought home from seven weeks in what we Americans call Yurrp, and another stack of things that came while I was gone.

DVDs of course stand out. Apart from items scooped up in Bologna, here are a few highlights. Some are quite old, some very recent, but all were new to me.

The Magnificent Ambersons, on a Region 2 disc from Montparnasse, in cooperation with Cahiers du cinéma. The squarish box houses a slim booklet, a remastered copy, and bonus documents: interviews with Bill Krohn and Jean Douchet, and a 51-minute conversation between Welles and Bogdanovich. Plus the original trailer.

Engineer Prite’s Project, Kuleshov’s first film from 1918. It’s from Absolut Medien in collaboration with Hyperkino, which we wrote about last year. German subtitles only. Comes with a 54-minute documentary by Semyon Raitburt on the Kuleshov effect.

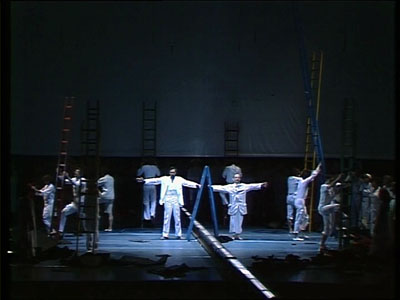

Another German release, but with English subs: Finally, the 1983 Stuttgart production of Philip Glass and Constance de Jong’s gorgeous Satyagraha. For once PoMo staging enhances the story. In the hammering opening of the second act, the mocking laughter of the South African whites comes from a vast row of beer swillers. The pre-HD imagery is a little soft, but my ancient Beta off-air copy can finally be laid to rest. From Arthaus Musik.

Absolut Medien also gives us The New Babylon, one of the greatest but least-known Soviet Montage films. The original Shostakovich score has been used, and the German reconstruction has English subtitles. Apparently a UK edition is on the way. The film is hard to cope with digitally: Lots of fog, smoke, and steam; diffuse photography; shots with significant action in out-of-focus planes. Still, it’s a big improvement on the bargain French edition in circulation. Tom Paulus, a real gentleman, surrendered the last copy in Bruges to me.

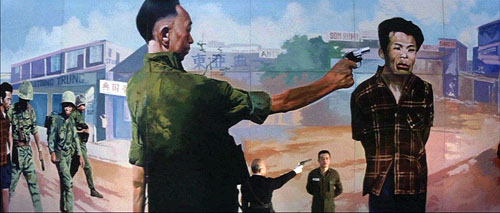

The venturesome French company Carlotta has launched an Oshima collection, though it doesn’t seem to appear on the Carlotta website! I found three must-have items at Fnac: A Treatise on Japanese Bawdy Songs, Japanese Summer: Double Suicide, and best of all Three Resurrected Drunkards. The last is a bizarre masterpiece mixing a boy band up with the Vietnam war and Japanese discrimination against Koreans. About 40 minutes in, Oshima provides the most anxiety-provoking reel change in cinema. All Region 2.

Now for some books and journals:

James Udden, one of my last dissertators before I retired, has written the first book-length study of Hou Hsiao-hsien in English. No Man an Island: The Cinema of Hou Hsiao-hsien puts Hou firmly in the context of Taiwanese film history and culture. It offers some provocative suggestions, particularly in arguing that it’s misleading to consider Hou an essentially Chinese director. Jim, who lived in Taiwan and speaks Mandarin, spent many years watching Chinese films from all eras, and he balances this breadth with close study of each Hou film. From Hong Kong University Press.

James Udden, one of my last dissertators before I retired, has written the first book-length study of Hou Hsiao-hsien in English. No Man an Island: The Cinema of Hou Hsiao-hsien puts Hou firmly in the context of Taiwanese film history and culture. It offers some provocative suggestions, particularly in arguing that it’s misleading to consider Hou an essentially Chinese director. Jim, who lived in Taiwan and speaks Mandarin, spent many years watching Chinese films from all eras, and he balances this breadth with close study of each Hou film. From Hong Kong University Press.

Eva Laass has just published a wide-ranging study of current narrative strategies in Broken Taboos, Subjective Truths: Forms and Functions of Unreliable Narration in Contemporary American Cinema. She examines Forrest Gump, Thank You for Smoking, Natural Born Killers, Fight Club, and other works in the light of several questions. What different forms of narrative unreliability can be distinguished? Why have unreliably narrated films become so popular in recent years? Which needs do they meet in American culture? Although available from Amazon.de, the book is in English.

I met Steven Jacobs, a brilliant young art historian with wide-ranging expertise, at the Bruges Zomerfilmcollege some years ago. This year he gave me a copy of his 2007 book, The Wrong House: The Architecture of Alfred Hitchcock. Drawing on research in production documents, it’s a careful and imaginative analysis of the master’s use of interior spaces, including discussion of his “staircase complex.” Steven has even reconstructed floor plans for some movies. He is interviewed about the book, in Dutch, here.

For Paolo Gioli admirers, the forty-fifth Pesaro festival catalogue should be welcome. A retrospective of Gioli films is accompanied by essays, an extensive interview with Giacomo Daniele Fragapane, and a detailed, annotated filmography. Everything is bilingual Italian/ English. You can download the catalogue as a pdf here. I hope to post my contribution, with some extra frames, on this site in the next month or so.

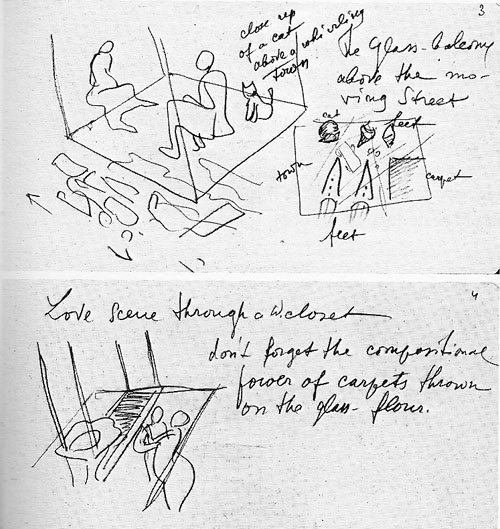

One of Eisenstein’s most ambitious projects was The Glass House (1927-1930). Inspired by skyscrapers, he envisaged a movie set in a high-rise apartment building of the future, with transparent walls and ceilings. He savored the idea of juxtaposing action in different layers (akin to the sequence in M. Giffard’s apartment in Tati’s Play Time). Some of the results can be seen surmounting this entry: a cat curled above a moving street, intertwined lovers seen through a bathroom floor. Another sketch shows a dying woman in the foreground and elevators carrying oblivious people past her.

The bold project is documented in a lovely French volume edited by Alexandre Laumonier and translated by Valérie Pozner and Michail Maiatsky. Glass House contains diary extracts, working notes, and sketches, all thoroughly annotated by François Albera. In a synoptic essay, Albera discusses the role of architecture in Eisenstein’s thinking.

Everyone seems to be talking about the roles of film festivals these days, and a current roundup of opinion can be found in the Cologne-based magazine Schnitt. The magazine is published in German, but for the festival symposium in issue 54, the editors provide English versions of essays by Marco Müller (Venice), Cameron Bailey (Toronto), and many other festmachers. Some radical ideas floating around here, including the suggestion by Lars Henrik Gass (Oberhausen) that subsidies for national film industries, and their festivals, may have to end. (His essay is available in English here.)

Everyone seems to be talking about the roles of film festivals these days, and a current roundup of opinion can be found in the Cologne-based magazine Schnitt. The magazine is published in German, but for the festival symposium in issue 54, the editors provide English versions of essays by Marco Müller (Venice), Cameron Bailey (Toronto), and many other festmachers. Some radical ideas floating around here, including the suggestion by Lars Henrik Gass (Oberhausen) that subsidies for national film industries, and their festivals, may have to end. (His essay is available in English here.)

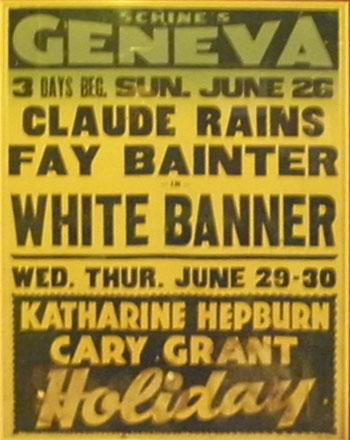

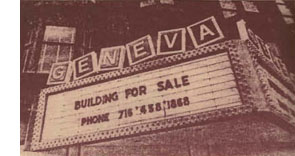

In the wake of my homage to the Geneva Theatre/ Smith Opera House, Karen Colizzi Noonan kindly sent me some issues of Marquee, the journal of the Theatre Historical Society of America. Marquee is going strong after forty years, and it remains a lavish production, with big stills and in-depth research. The Society, which is currently updating the standard source book Great American Movie Theaters, holds an annual meeting that includes theatre tours. If you’re at all interested in American film history, you should visit the Society’s website.

There were other items on the two piles, but I have to go. My eyes and ears have some work to do. I’ll leave you with the most unexpected development, film-book-wise, I have encountered upon my return.

Three Resurrected Drunkards.

Books, an essential part of any stimulus plan

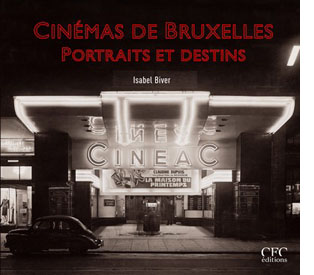

The Pathé Palace theatre, Brussels, designed by Paul Hamesse.

DB here:

Some shamefully brief notes on new publications. Disclaimer: All are by friends. Modified disclaimer: I have excellent taste in friends.

You call me reductive like that’s a bad thing

It’s easy to see why we might tell each other factual stories. We have an appetite for information, and knowing more stuff helps us cope with the social and natural world. We can also imagine why people tell fictitious stories that we think are true. Liars want to gain power by creating false beliefs in others. But now comes the puzzle. Why do we spend so much of our time telling one another stories that neither side believes?

Brian Boyd’s On the Origin of Stories: Evolution, Cognition, and Fiction (Harvard University Press) is the first comprehensive study of how the evolution of humans as a social, adaptively flexible species has shaped our propensity for fictional narrative. The book is a real blockbuster, making use of a huge range of findings in the social and biological sciences. Brian paints a plausible picture, I believe, of the sources of storytelling. Along the way he shows how two specimens of fiction, The Odyssey and Horton Hears a Who, exemplify the richness and value of make-believe stories.

Brian Boyd’s On the Origin of Stories: Evolution, Cognition, and Fiction (Harvard University Press) is the first comprehensive study of how the evolution of humans as a social, adaptively flexible species has shaped our propensity for fictional narrative. The book is a real blockbuster, making use of a huge range of findings in the social and biological sciences. Brian paints a plausible picture, I believe, of the sources of storytelling. Along the way he shows how two specimens of fiction, The Odyssey and Horton Hears a Who, exemplify the richness and value of make-believe stories.

The standard objection to an evolutionary approach to art is that it’s reductive. It supposedly robs an individual artwork of its unique flavor, or it boils art-making down to something it isn’t, something blindly biological. Art is supposed to be really, really special. We want it to be far removed from primate hierarchies, mating behavior, or gossip. For a typical criticism along these lines, see this review of Denis Dutton’s The Art Instinct. Brian has already adroitly responded to this sort of complaint here. See also Joseph Carroll’s examination of reductivism on his site.

It seems to me that all worthwhile explanations are reductive in some way. They simplify and idealize the phenomenon (usually known as “messy reality”) by highlighting certain causes and functions. This doesn’t make such explanations inherently wrong, since some questions can be plausibly answered in such terms. For example, often the literary theorist is asking questions about regularities, those patterns that emerge across a variety of texts. That question already indicates that the researcher isn’t trying to capture reality in all its cacophony. (For me, it’s all about the questions.)

Literary humanists sometimes talk as if they want explanations to be as complex as the thing being explained. But that would be like asking for the map to be as detailed as the territory. In fact, however, humanists tacitly recognize that explanations can’t capture every twitch and bump of the phenomenon. Consider some types of explanations that are common in the humanities: Culture made this happen. Race/ class/ gender / all the above caused that. Whatever the usefulness of these constructs, it’s hard to claim that they’re not “reductive”—that is to say, selective, idealized, and more abstract than the movie or novel being examined. Likewise, when people decry evolutionary aesthetics for its “universalist” impulse, I want to ask: Don’t many academics take culture or the social construction of gender to be universals?

I want to write more about Brian’s remarkable book when I talk about our annual convention of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image. For now, I’ll just quote Steven Pinker’s praise for On the Origin of Stories: “This is an insightful, erudite, and thoroughly original work. Aside from illuminating the human love of fiction, it proves that consilience between the humanities and sciences can enrich both fields of knowledge.”

Faded beauties of Belgium

In its day, Brussels played host to some fabulous picture palaces. Now after years of research Isabel Biver has given us a deluxe book, Cinémas de Bruxelles: Portraits et destins. It’s the most comprehensive volume I know on any city’s cinemas.

Isabel glides backward from contemporary multiplexes and tiny repertory houses to the grandeur of the picture palaces. The Eldorado was a blend of Art Deco style and quasi-African motifs sculpted in stucco. King Albert graced the opening in 1933. There was the Variétés, a multi-purpose house built in 1937. It had rotating stages, air conditioning, and space for nearly 2000 souls (cut back to a thousand when Cinerama was installed). It was, Isabel claims, the first movie house in the world to be lit entirely by neon.

Isabel glides backward from contemporary multiplexes and tiny repertory houses to the grandeur of the picture palaces. The Eldorado was a blend of Art Deco style and quasi-African motifs sculpted in stucco. King Albert graced the opening in 1933. There was the Variétés, a multi-purpose house built in 1937. It had rotating stages, air conditioning, and space for nearly 2000 souls (cut back to a thousand when Cinerama was installed). It was, Isabel claims, the first movie house in the world to be lit entirely by neon.

Then there was the Pathé Palace, shown at the top of this entry. Dating back to 1913, it boasted 2500 places and included cafes and even a garden. This imposing Art Nouveau building was designed by Paul Hamesse, probably the city’s most inspired theatre architect. Hamesse also created the Agora Palace, which opened in 1922. Huge (nearly 3000 seats), the Agora was one of the most luxurious film theatres in Europe.

And we can’t forget the Métropole, the very incarnation of the modern style. Sinuous in its Art Deco lines, it packed in 3000 viewers. When it opened in 1932, it attracted nearly 53,000 spectators during its first week. The neon on the Métropole’s façade lit up the night, and its two-tiered glassed-in mezzanine became as much a spectacle as the films inside. See the still at the bottom of this earlier entry of mine. A ghost of its former self still sits on the Rue Neuve. Local historians consider the failure to preserve the Métropole a scandal in the city’s architectural history.

Cinémas de Bruxelles is a model presentation of local theatres. Not only does it trace the history of the major houses, but it includes a glossary of terms, a large bibliography, and an index of all theatres, both central and suburban. Needless to say, it is gorgeously illustrated. Whether or not you read French, I think you would enjoy this book, for it evokes an age we’re all nostalgic for, even if we didn’t live through it.

A TV interview with Isabel in French is here, with glimpses of what remains of the Métropole. She also gives guided tours of the remaining cinemas in the city center and in the neighborhoods. More information here.

A guy named Joe

Tropical Malady.

It’s seldom that a young filmmaker gets a hefty book devoted to him. Apichatpong Weerasethakul (aka Joe) will turn forty next year. He comes from Thailand, not a country adept at negotiating world film culture, and he is known chiefly for only four features. Yet he has become one of the most admired filmmakers on the festival circuit. His films are apparently very simple, usually built on parallel narratives. They have a relaxed tempo, exploiting long takes, often shot from a fixed vantage point, and scenes whose story points emerge very gradually. Joe’s movies tease your imagination while captivating your eyes. Each one could earn the title of his first feature: Mysterious Object at Noon.

It’s appropriate, then, that the tireless Austrian Film Museum has published a lavish collection of critical studies. Edited by James Quandt, the anthology arrives along with a massive retrospective of the director’s work, which includes many short documentaries and occasional pieces.

It’s appropriate, then, that the tireless Austrian Film Museum has published a lavish collection of critical studies. Edited by James Quandt, the anthology arrives along with a massive retrospective of the director’s work, which includes many short documentaries and occasional pieces.

James’ introductory essay, as evocative and eloquent as usual, is virtually a monograph, discussing all the features in depth. Alongside it are discerning essays by other old hands. Tony Rayns offers his usual incisive observations, focusing largely on Joe’s short films and the recurring imagery of hospitals, while Benedict Anderson surveys the Thai reception of Tropical Malady. Karen Newman offers precious information and judgments about Joe’s installations. The director himself signs several essays and participates in interviews and exchanges. Even Tilda Swinton has something to say.

I remember when Mysterious Object at Noon played the Brussels festival Cinédécouvertes in 2000. I was baffled. Joe’s movies taught me to watch them, and finally with Syndromes and a Century I got in sync. Its austere lyricism, off-center humor, and patiently unfolding echoes win me over every time I see it. (You can search this blogsite for several mentions, but JJ Murphy has a fuller appreciation of Syndromes here.) Thanks to Alexander Horwath and his colleagues for making this wonderful anthology, decked out with color stills and rich bibliography and filmography, available to us—and in English.

Zap goes the Chazen

Zap, Snarf, Subvert, Young Lust, Tits & Clits, Air Pirates Funnies, Slow Death Funnies, Feds ‘n’ Heads, Corn Fed Comics, Dope Comix, Cocaine Comix, Corporate Crime Comics: The names define the era. The sixties didn’t end until the mid-1970s, and these outrageous cartoon books really came into their own after the election of Nixon in 1968.

On 2 May, the Chazen Museum on our campus launches its exhibition, Underground Classics: The Transformation of Comics into Comix, 1963-1990. A whirlwind of events, including films and lectures, will revolve around galleries full of imagery from the demented pens of Kim Deitch, Aline Kominsky Crumb, Trina Robbins, Gilbert Shelton, Robert Crumb, Bill Griffith, and many other cartoonists.

The show was originated by Jim Danky, a scholar of public media from our State Historical Society, and Denis Kitchen, comic artist and the publisher of Kitchen Sink Press here in Wisconsin. Jim has long argued for the archival value of minority and subcultural publications. He started our Center for Print Culture and has been an advocate for gathering print materials by and for children, women, and ethnic minorities. He virtually created the area of “alternative library journalism”—collecting obscure publications from all zones of the political spectrum. I recall his satisfaction in telling me that he had managed to acquire a collection of The War Is Now!, the radical Catholic newsletter published by Hutton Gibson, father of Mel.

The show was originated by Jim Danky, a scholar of public media from our State Historical Society, and Denis Kitchen, comic artist and the publisher of Kitchen Sink Press here in Wisconsin. Jim has long argued for the archival value of minority and subcultural publications. He started our Center for Print Culture and has been an advocate for gathering print materials by and for children, women, and ethnic minorities. He virtually created the area of “alternative library journalism”—collecting obscure publications from all zones of the political spectrum. I recall his satisfaction in telling me that he had managed to acquire a collection of The War Is Now!, the radical Catholic newsletter published by Hutton Gibson, father of Mel.

For some years Jim has been telling me about his efforts to mount the comix show. It’s no small matter to collect this elusive material and then persuade a museum to show it. Not too many galleries feature talking penises, Jesus visiting a faculty party, or Mickey and Minnie robbed at gunpoint by a dope dealer. Maybe we forget, in the age of the Web and The Onion, just how scabrous these things looked forty years ago. Actually, they still look scabrous. They also look pretty funny, and they’re often well-drawn. As a historical codicil, the exhibition includes 1980s images from artists extending the tradition, such as Drew Friedman and Charles Burns.

The show runs until 12 July 2009. If you can’t get to town, there’s the splendid catalogue. It includes essays by Jim and Denis, Jay Lynch, Patrick Rosenkranz, Trina Robbins, and Paul Buhle. There are free screenings of Fritz the Cat and Crumb at our Cinematheque. And you can read an interview with Jim about the show here.

Remember our motto: Lotsa pictures, lotsa fun.

Up next: Days and nights at Ebertfest.

The Eldorado Cinema, Brussels, designed by Marcel Chabot.

A tale of 2–make that 1 and 1/3–screens

DB here:

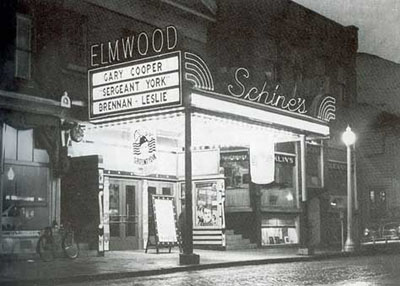

Last week family affairs took me back to my home area, the Finger Lakes region of New York State. About ten miles from our farm lies the village of Penn Yan (short for Pennsylvania Yankees). When I was growing up there in the 1950s and 1960s, Penn Yan boasted about 3500 people—enough to support one movie theatre. That theatre, the Elmwood on Elm Street, was where I saw most of the movies I didn’t see on TV.

The Elmwood was my introduction to film. When my parents went to town, I was embedded with hundreds of other kids in Saturday afternoon matinees of Tarzan and Lone Ranger movies. On Friday nights, I might catch June Allyson, Donald O’Connor, or Martin and Lewis. When I got older I saw Lawrence of Arabia and From Russia with Love. The Elmwood showed a fair number of art films in the 1960s, including The Servant, The L-Shaped Room, and even 8 ½ (dubbed, I think).

Built in the early 1920s, the Elmwood was acquired by the Schine brothers in 1936. Some towns in our area had two or three Schine theatres. Schine Amusements penetrated Auburn, Bath, Canandaigua, Corning, Cortland, Glens Falls, Gloversville (where it all started), Hamilton, Herkimer, Lockport, Massena, Oneonta, Oswego, Perry, Rochester, Salamanca, Seneca Falls, Syracuse (four houses), Tupper, and Watertown. Clearly, they were leaving the major cities to the big boys. The firm also owned venues in Kentucky and Ohio (none in Cleveland or Cincinnati, but three in Bucyrus). By snapping up screens in the sticks, Meyer and Louie Schine wound up holding nearly a hundred screens in their prime.

Although the brothers went for the smaller markets, they didn’t forget the amenities. They contracted some of the top theatre architects, notably John Eberson, a fantasist with eclectic tastes. The Elmwood didn’t benefit much from the Schines’ largesse as far as I can tell, but it was a sturdy place, with 838 seats, or one for every four people in town.

The Elmwood passed out of the Schines’ hands and eventually closed in the early 1970s. For awhile it was an indoor tennis court. The village offices now sit on the site. (Photo: Darlene Bordwell.)

But Penn Yan still has three screens, which I discovered when my sister Diane Verma and I went to Ken Kwapis’ He’s Just Not That Into You. It’s a network narrative like Kwapis’ earlier Sexual Life, and like that (and his Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants) it has some affecting and clever moments. There’s also a nice handling of shot/ reverse-shot when characters are turned away from each other. Mainly, though, I went to see the town’s multiplex, the Lake Street Plaza Theatres.

Converted from an exercise club, the LSP houses three screens in a bare-bones design typical of many multiplexes.

A young man, whose father owned the complex, sold the tickets and ran the projectors. A young woman handled the concession stand. Both were friendly and talkative. Diane and I, two of four people in the house, left happy, although the sugar in the Dots may have helped raise our mood.

Earlier that day, Diane, my other sister Darlene, and I were driving around our childhood haunts. The towns here are hollowed out by the big-box stores and the recession. Mall parking lots are full, but the main streets are desolate and many storefronts are empty.

Yet in another lake town we came across a surprise. At first I was puzzled. How could the Geneva Theatre have been replaced by a much older and more dignified building, the Smith Opera House?

The door was ajar.

Inside Bruce Purdy, the Technical Director and professional magician, and Sharon Barnes were preparing for a children’s play. They kindly led us on an exploration of this half-hidden jewel. It may have assumed its old name, but the building has regained the delirious splendor that was the Geneva in its heyday.

The Smith Opera House was built in 1894. To its stage came Sousa, Bill Bojangles Robinson, Ellen Terry, and traveling shows mounted by Belasco. The vaudeville programs started including short films during the 1910s, and the Smith was one of thirteen venues in which Edison screened his experiments in talking pictures. The Birth of a Nation played there. Soon the theatre became a movie house, called initially the Strand. It wasn’t the only film theatre in town, and by the late 1920s it had competition. The nearby Regent had already become a picture palace, with about 1000 seats; it screened its first sound picture, John Ford’s Four Sons, in 1928 (presumably in a music-plus-effects version).

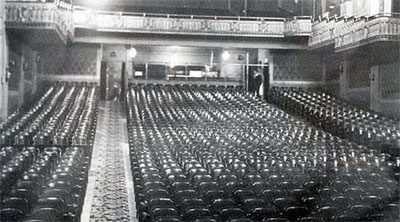

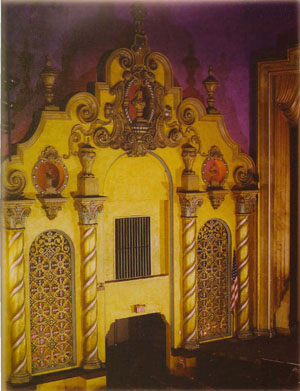

Enter, on cue, the Schines. They bought the Smith, and after playing burlesque there for some months, they decided to revamp it as a picture palace. The process took several years. The interior was stripped; opera seats were sold for a dollar each. What emerged was an “atmospheric,” with the dome displaying shifting clouds that would slowly clear to reveal twinkling stars. The architecture was a fanciful mix of Art Deco, Baroque, Art Nouveau, and Moorish influence. The premise was that you were in a courtyard under the heavens, surrounded by facades of buildings that were implausible but vaguely familiar in their exoticism.

With over 1800 seats, the Geneva Movie Theatre was advertised as the largest movie house in central New York. The first film to play there was Keaton’s Parlor, Bedroom, and Bath in March 1931. The manager, Mr. Gerald Fowler, stayed in charge until 1965.

I didn’t go to the Geneva as often as the Elmwood. Not until I got my Learner’s Permit (a life-changing event to country youth) was I able to drive to Geneva on my own. At the Geneva I saw Mary Poppins, What’s New, Pussycat?, and the CinemaScope version of How the West Was Won. I have no memories of the décor, but by all accounts it was decaying.

Like the Elmwood, the Geneva was closed in the 1970s. Today it looks spanking new. It hosts musical acts (Ani DeFranco is coming up), local and touring stage productions, and on weekends films, “mostly foreign and arthouse,” as Bruce Purdy explained. When we were there the theatre was running a package of Academy Award Best-Picture nominees.

My sisters and I first paused in the lobby, with its fine hanging lamps.

Inside, the auditorium area is of course very impressive, flanked by facades with corkscrew columns.

Along the balcony are vaguely ziggurat wall designs.

Just in case there was too much empty space, architect Victor Rigamount added some escutcheons.

In the projection booth, Bruce showed us the Brenkograph, a marvelous old gadget for projecting lantern slides in dissolving views. The Brenkograph provided the milky clouds cast onto the ceiling: light was pumped through a swirling oil mixture.

In 1946, the year before I was born, US movie attendance reached its peak of about 82 million weekly. The industry had receipts of nearly $1.6 billion. It must have looked like filmgoing would never fall off. But it did, and fast. Enjoying Peter Pan, Moby Dick, and Davy Crockett, I was living through the first major decline in the film industry. By the time I left for college in 1965, weekly US attendance had dropped to 20 million, where it would hover for nearly three decades. Hollywood’s annual box-office receipts were then $927 million (about $657 million in 1947 dollars). In the course of my eighteen years the country had lost 5,000 screens and about 50,000 theatre jobs.

I wish I could go back to see how these old theatres looked then. I wish I could photograph them, inside and out. I wish that I could return to the Elmwood in June 1954 to ask Mr. Norman Williams (unmarried) about the new screen, said to be twenty feet high and 35 feet long—redesigned, of course, for CinemaScope. He was planning to add stereophonic sound, which would, the newspaper story explains, “create the illusion that the sound travels with the movement of actors or objects across the screen.” But until the new system arrived, Mr. Williams said, only Warner Bros’ CinemaScope pictures would be run, because they didn’t require stereo. You mean movies like A Star Is Born and Rebel without a Cause? What wouldn’t I give to see those in their original form, from the front row.

I wish I could go back to see how these old theatres looked then. I wish I could photograph them, inside and out. I wish that I could return to the Elmwood in June 1954 to ask Mr. Norman Williams (unmarried) about the new screen, said to be twenty feet high and 35 feet long—redesigned, of course, for CinemaScope. He was planning to add stereophonic sound, which would, the newspaper story explains, “create the illusion that the sound travels with the movement of actors or objects across the screen.” But until the new system arrived, Mr. Williams said, only Warner Bros’ CinemaScope pictures would be run, because they didn’t require stereo. You mean movies like A Star Is Born and Rebel without a Cause? What wouldn’t I give to see those in their original form, from the front row.

Just before I left the area in 1965, I could have quizzed the managers and staff about the old days. After the war, had they suspected what was coming? What was it like to watch your livelihood shrivel year by year? I didn’t know enough to ask. I didn’t understand what had happened.

In the meantime, we haven’t lost everything. On one screen of the Lake Shore Plaza, you could have seen Watchmen on opening weekend. The projection is very good.

My general information about theatres and attendance is culled from back volumes of The Film Daily Yearbook. The Schine family entered history in another way; see here. Information about CinemaScope at the Elmwood comes from the Penn Yan Chronicle-Express of 10 June 1954, p. 1. My account of the Geneva Theatre is largely derived from two publications, The Smith Opera House (Geneva: n.d.) and Charles McNally’s The Revels in Hand: The First Century of the Smith Opera House, October 1894-October 1994 (Geneva: Finger Lakes Regional Arts Council, 1995). Both are available at the theatre; for contact information go here. The Elmwood photos come from wetlandspy. Check out Darlene’s photo page too.

For a panoramic study of American movie exhibition, see Douglas Gomery’s Shared Pleasures: A History of Movie Presentation in the United States. The first time I met Doug, he asked where I was from. I said Penn Yan. He nodded. “Okay, so you went to a Schine theatre.” The man knows his stuff.

Thanks to Bruce Purdy and Sharon Barnes for their hospitality. And thanks to Ryan Kelly for asking me to clarify the situation with Four Sons.