Archive for the 'Narrative strategies' Category

Politics and subjectivity: MEMORIES OF UNDERDEVELOPMENT on the Criterion Channel

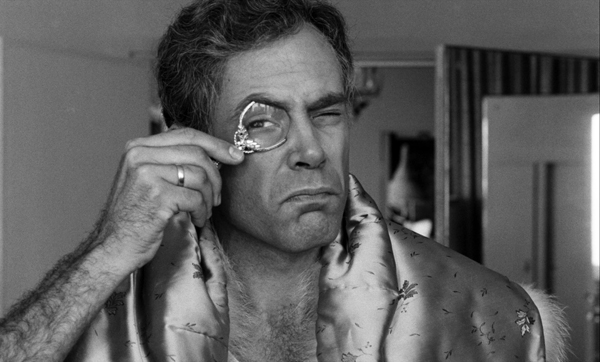

Memories of Underdevelopment (1968).

Jeff Smith here:

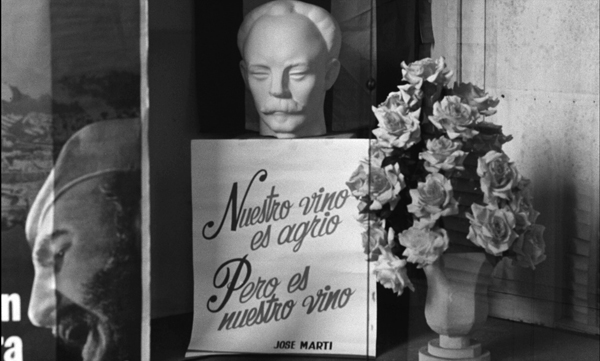

Early last week, the Criterion Channel posted the latest in our series of “Observations on Film Art.” It was my turn at the plate with a video essay on Tomás Gutiérrez Alea’s Memories of Underdevelopment. The film has long been a personal favorite due to its formal and political complexity. If the aphorism “the personal is political” rings true for you, then you owe it yourself to watch Memories of Underdevelopment. It is a post-revolutionary culture’s most fully realized depictions of the survival of apre-revolutionary mentality.

A Third Way for Third Cinema

Hour of the Furnaces (1968).

“Toward a Third Cinema,” the 1969 manifesto written by filmmakers Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getino, remains an important touchstone in the history of global film culture. It captures the militant spirit that characterized post-colonial activism in the late sixties and early seventies. At one point, Solanas and Getino describe the camera as an “inexhaustible expropriator of image-weapons” and the projector as a “gun that can shoot 24 frames per second…” (For the record, that less than a quarter of the speed of an M134 MInigun, which fires at a rate of 100 rounds per second.)

As advocates for the vital role guerrilla filmmaking could play in anti-imperialist struggles, Solanas and Gettino explicitly opposed “third cinema” to more established modes of film production. Of course, the big enemy was Hollywood. It represented a form of commercial cinema that was inextricably linked to the ideology of American capitalism.

More surprisingly, though, Solanas and Getino also condemned European art cinema and its attendant emphasis on individual personal expression. Although art cinema represented a step forward in terms of its attempt to create a non-standard language, it remained “trapped inside the fortress” in Jean-Luc Godard’s words. For Solanas and Getino, the French New Wave and Brazil’s Cinema Novo opened up new aesthetic possibilities. They offered the brio and rebelliousness of youth, yet fit neatly into established commercial distribution networks as the “angry wing” of a capitalist, bourgeois society.

Solanas and Getino practiced what they preached, however. Their ambitious 4-hour agit-prop documentary The Hour of the Furnaces remains a prototype of third cinema practice. The film is a collage of contrasting images and sounds. These juxtapositions often involve the kinds of associational editing and montage principles that Soviet directors like Dziga Vertov and Sergei Eisenstein used in their work. At one point, Solanas and Gettino intercut cattle and sheep being slaughtered on the killing floor of a meatpacking plant with ads for various products originating in Western capitalist societies. (See below and above.)

The comparison was about as subtle as the sledgehammer used to kill the cattle. But the message was clear. The global success of American products, like Chevrolets, depended upon the violent suppression of “underdeveloped” populations.

Memories of Underdevelopment’s critique of post-colonialism is no less incisive, but it’s much less didactic. At first blush, Alea’s film seems to be the kind of European-influenced art cinema that Solanas and Getino explicitly reject. Indeed, Alea even self-consciously gestures toward this tradition through his explicit citation of French New Wave films, like Hiroshima Mon Amour. These allusions are reminiscent of the kinds of cinematic quotations that Godard and Francois Truffaut embedded in their own films.

Moreover, Alea also creates the kind of depth of narration in Memories of Underdevelopment that became strongly associated with art cinema’s emphasis on subjective realism. Throughout the film, Sergio’s thoughts and feelings on the current state of Cuba are given to us via voiceover narration. Many of Sergio’s observations function as ongoing commentary on the symptoms of “underdevelopment” that define contemporary Cuban society. For instance, over shots of downtown shops and boutiques, Sergio notes that Havana is often called the “Paris of the Caribbean.”

Such a descriptor seems a double-edged sword. The comparison to Paris is a way of praising the vibrancy of Havana’s cultural life, its bookstores, museums, cinemas, and modern department stores. Yet the qualification “…of the Caribbean” highlights its isolation from true taste-makers and fashionistas in New York, London, and Paris. For anyone who doesn’t live there, Havana is, at best, a playground for rich tourists from Europe and America.

As a member of the Cuban intelligentsia, Sergio often seems an unusually perceptive social critic. Yet Alea’s creation of such a strong alignment with Sergio seems designed to test the viewer’s moral and political allegiance. As a repository of pre-revolutionary attitudes, Alea’s characterization of Sergio encourages us to ask why Havana should aspire to be Paris in the first place. In a society that seeks to eliminate class distinction, why would one strive for such elitism no matter how rich and storied its culture may be?

In employing a device that often fosters sympathetic engagement with characters, is Alea just as “trapped inside the fortress” as French New Wave directors are? Actually, Alea also seems determined to turn the purpose of character alignment on its head.

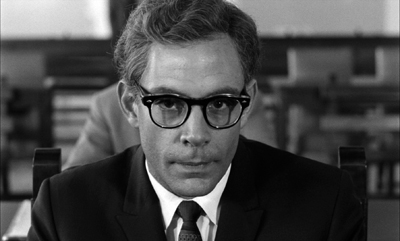

As an intellectual, Sergio possesses a great understanding of Cuba’s relation to the rest of the world, but he seems determined to ask the wrong questions about its future. Therein lies the character’s great tragedy. As novelist Edmundo Desnoes observes, “His irony, his intelligence, is a defense mechanism which prevents him from being involved in the reality.” There is no place outside the palace gates for those like Sergio. Yet in probing his place “inside the fortress” Alea also shows how it rots from within.

By turning the camera’s gaze inward, Alea navigates a path between the agit-prop documentary of Solanas and Getino and the formal adventurousness of an art cinema director like Chile’s Raúl Ruiz. He set out to examine the vestiges of bourgeois thinking in Castro’s Cuba, using Sergio as a “litmus test” for Cuban audience’s political sensibilities. If you find yourself sympathizing with Sergio, seeing him as a victim of the revolution…. Well, then you better check yourself before you wreck yourself. In posing such a challenge, Alea pulls off a pretty neat trick. He manages to create a “third way” in third cinema by merging the polemical aims of agit-prop with devices and formal structures of the art film.

The Portrait of the Artist as a Young Cad

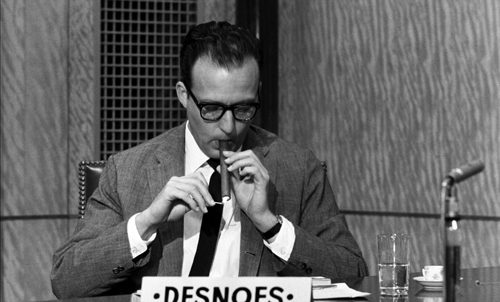

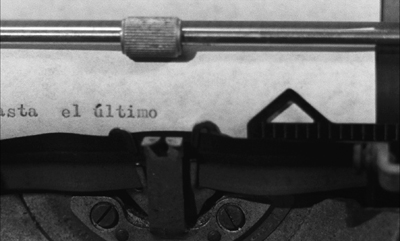

In a gesture that displays both self-consciousness and hubris, Edmundo Desnoes, the author of the novel that served as the source of the film, cast his hero as a writer. Although Alea changed much of Desnoes’ original story, this one small detail was something he preserved in his adaptation of the book. Indeed, just after Sergio has said goodbye to his wife and parents at the airport, we see him sitting at a typewriter. The sentence he writes – “All those who have loved and fucked me over up to the last moment have already gone.” – indicates both his anger in the moment and that his writing has more than a trace of autobiography.

Sergio’s status as a writer encourages the viewer to see him as a surrogate for both Desnoes and Alea. This possibility is even reinforced in a scene where Sergio attends a roundtable discussion of “Literature and Underdevelopment” where Desnoes is featured as one of the panelists.

If Sergio truly is a surrogate for the filmmakers, then Alea shows some real guts in centering his film on an alter ego that is both politically reactionary and sexually predatory.

It is a mark of the film’s complexity that Sergio has certain very attractive traits even though he emerges as a thoroughly unlikeable cad. He is smart, cultured, and good-looking, for example. But he is also passive, cynical, and snobbish.

The dimension of Memories of Underdevelopment, however, that most clearly reveals Sergio’s corruption and moral rot involves his various relationships with women. Alea develops this idea throughout the film in terms of a Pygmalion motif: Sergio seeks to remake his romantic partners in the image of his first love, a German girl named Hanna.

In flashbacks, we learn that Sergio taught his first wife how to talk and dress, how to approximate a downmarket version of European elegance. Similarly, when Sergio initiates a romance with Elena, we see him taking her to bookstores and museums, trying to instill in her some appreciation for art and literature.

Sergios’ European ideals even pervade his sexual fantasies. After looking at an image of Botticelli’s Venus, Sergio imagines his housekeeper, Noemi, lying naked on his bed in a similar pose.

Similarly, when Noemi describes her Christian baptism to Sergio, he imagines it in images that seem culled from a hack romance novel. They embrace in a swoon, with their eyes locked, all wet clinging fabric and raging hormones.

Shot in slow motion, the episode is also accompanied by Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons, a concert piece so familiar to most audiences that its inclusion borders on cliché.

It would be one thing, however, if Sergio’s sexual peccadilloes remained in the realm of harmless fantasy. More often than not, Alea depicts Sergio’s relations with women as episodes of exploitation and mental cruelty. A flashback to Sergio’s adolescence implies that the psychological roots of this misogyny lies in his first sexual experience as he and a school chum visit a brothel.

The transactional nature of the encounter is replicated in Sergio’s relationships later in life. After Sergio splits with Hanna, he marries Laura and is given a cushy job in the family business. He also lures Elena up to his penthouse with the promise of his ex-wife’s old clothes. In each instance, Sergio’s sexual or romantic relations with women are based on some notion of recompense: cold hard cash with the prostitute, the reward of a job with his wife, and haute couture with Elena, his new conquest.

As before, the exploitative undertones of Sergio’s relationships with women are reinforced by the film’s style. Sergio’s initial meeting with Elena is handled in a series of long tracking shots representing his optical point of view.

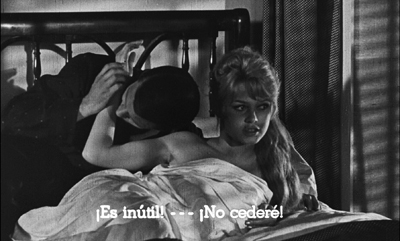

With his creepy pickup line, Sergio seems more of a stalker than a paramour. The troubling implications of this first encounter become more explicit midway through the film when Sergio literally chases Elena around his bedroom. The narrative rhyme with the earlier scene is made evident in Alea’s mobile long take, which once again represents Sergio’s visual perspective. Elena flirts coquettishly, sticking out her tongue at the camera.

But her discomfort in the situation becomes evident in her attempts to rebuff Sergio’s advances. Like the film’s use of voice-over, the moving pov shots spatially align the viewer with Alea’s unlikeable protagonist even as it implicates the audience in his victimization of Elena.

Later, when Sergio is put on trial for sexually assaulting Elena, he becomes the object of the camera’s unrelenting look along with the other petitioners. Here Alea uses a variant of the previous style. The longish takes remain. But where the previous shots used movement to suggest Sergio’s brazen advances toward Elena, the camera’s stasis within the courtroom reflects the perspective of the tribunal hearing the case. Alea cuts quite freely around the space. Still, he always returns to static close-ups of Sergio, Elena, her mother, her father, and her brother as they respond to the questions of offscreen interlocutors.

The scene proves to be the biggest challenge to the viewer’s allegiance with Sergio. He affects the demeanor of someone wrongfully accused. Yet, although the act itself is elided, Elena’s protestations beforehand and her tears afterward suggest that Sergio is probably guilty of the crimes for which he is accused. His voice-over, however, reveals his resentment toward the entire proceedings. The matter of his guilt or innocence is immaterial. What truly angers Sergio is the fact that someone of his lofty station endures treatment more suited to a common crook. He claims that he would never have faced charges during the Batista era. Sergio blames his ordeal on Cuba’s new political landscape. The judgment of his actions is more a matter of proletarian revenge rather than anything he has done.

It is easy to imagine some viewers feeling a pang of sympathy for Sergio. Jurisprudence often includes the presumption of innocence and Alea’s handling of the incident with Elena is ambiguous enough to have certain doubts. Moreover, Sergio has been impoverished by the government’s seizure of his property, something that makes his anger at Elena and her family seem more reasonable.

But what is especially striking in Sergio’s voice-over is the sense of entitlement he displays based on his previous social position. Alea seems to count on the fact that Cuban audiences in 1968 will recognize Sergio’s condescension as a symptom of pre-revolutionary ideology. His previous wealth, his education and culture, his status as an artist all sanction his satisfaction of his desires, even if that means taking the virginity of an 18-year old girl. In his characterization of Sergio, Alea not only reflects the broader influence of the French New Wave. He also revives a classic character type of French literature and cinema: the Parisian roué.

Mr. Schwitters Meets Mr. Alea: Mixing Modalities in Memories

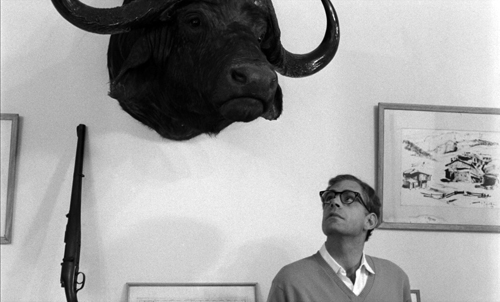

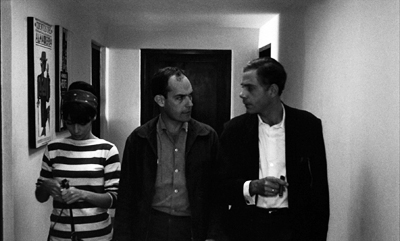

The most oft-quoted line in Memories of Underdevelopment is not something said by Sergio, Elena, or even Sergio’s brusque friend, Pablo. Instead it is uttered by Alea in a director cameo. He appears in a scene where Elena performs in a screen test at ICAIC, Cuba’s central institute of film production. Alea (center, below) shows Sergio and Elena some of his work in progress, saying, “It’s a collage. A bit of this and a bit of that.”

Most critics have noted both the self-consciousness of the moment and its layers of meaning. The footage that Alea screens is made up of scenes cut out by Cuban censors under the Batista regime. It offers a fairly dismal portrait of Cuban film history as something mostly comprised of titles imported from other colonial empires, like the Brigitte Bardot vehicle Une parisienne. This is precisely the kind of cinematic legacy that Alea and other Third Cinema directors set out to counter.

Alea’s description of his film as a collage also has been interpreted as a clue as to how one should view Memories of Underdevelopment itself. More specifically, his comment captures some sense of the film’s complex visual texture, its mix of still photographs, television clips, newspaper headlines, and even comic strip panels.

It also describes the way Alea embeds documentary footage within his portrait of Sergio as a disaffected intellectual. To some extent, this strategy is simply a continuation of Alea’s digressive approach to narration. These interpolated documentary passages fit a larger scheme that also shows fragments of Sergio’s consciousness in fleeting fantasy images and elliptical flashback sequences. Yet these segments of Memories of Underdevelopment also sharpen its political edge. In effect, Alea injects the agit-prop spirit of The Hours of the Furnaces into his “second cinema” character study.

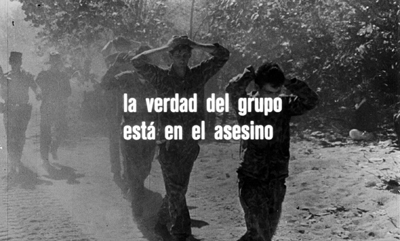

Consider the segment entitled “The Truth of the Group is in the Murderer.”

It is motivated as Sergio’s description to Pablo of the book he is currently reading. But it uses photographs and newsreel footage to explore the aftermath of the Bay of Pigs invasion and the system of political repression and torture that existed under Batista. The title hints at the larger ideological point of the sequence, namely that the regime’s institutional framework served as a means of displacing and shifting criminal culpability away from its individual members. As a member of the bourgeoisie, Sergio is implicated in this dialectical arrangement between the individual and the group insofar as each part of it gives meaning to the whole.

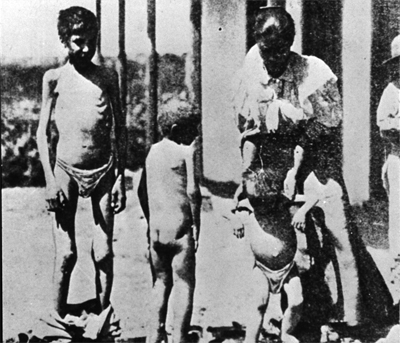

In a scene where Pablo gets his car ready for inventory, Sergio’s mind begins to wander. Alea then cuts to a series of still photos depicting hunger and starvation in Latin America.

In his voiceover, Sergio notes that the death toll from malnutrition exceeds the combat deaths of World War II. The sequence suggests Sergio’s insight into the problems of underdevelopment under capitalism. Alea’s imagery poignantly illustrates the disproportionate impact of such deprivations on society’s most vulnerable members, its children. This mini-documentary in Memories pointedly rebukes the colonialist regimes still present in Latin America by highlighting the cruel effects of such economic exploitation by First World powers.

Similar sequences pop up in the episode labelled, “A Tropical Adventure.” The title refers to Sergio and Elena’s visit to Ernest Hemingway’s former home in Havana, which had been turned into a museum.

A series of photos shows Hemingway’s involvement in Spanish politics, particularly the civil war of the 1930s. A second series of photos depicts Hemingway’s relationship with his longtime servant Rene Villarreal. In his voiceover, Sergio hints that their master-servant relationship captured some of the vagaries of American imperialism. Sergio concludes that Hemingway must have been unbearable.

Sergio’s voice-over during these sequences offers one of the clearest statements of his character’s dualism. He conveys sympathy with Villarreal as a fellow Cuban and recognizes that Hemingway’s paternalism is itself an expression of colonialist ideology. Yet Sergio also seems to identify with Hemingway’s social position given his elite status as a rentier and aspiring writer. His trenchant observations about Hemingway’s relationship with his servant is an unwitting acknowledgement of how easily he could slip into the shoes of the great American author and adventurer.

In the battle for Sergio’s soul the “great white hunter” wins out as we see him hiding from Elena until she just gives up and walks away. Sergio’s condescending treatment of Elena is merely the flip side of the imperialist dialectic expressed by “the faithful servant and the great Lord. The colonialist and Gunga Din.”

Memories’ political sophistication largely derives from Alea’s sensitive treatment of his protagonist’s inner conflict. As a remnant of a previous historical moment, Sergio’s jaundiced perspective suggests that life under the Castro regime has simply substituted a new set of problems for life under the Batista regime. Indeed, for many viewers circa 1968, Alea’s look back at the era between the Bay of Pigs and the Cuban missile crisis might seem an endorsement of his hero’s nihilism and fatalism. Such was the case for several U.S. film critics who Alea disparaged later, claiming that their identification with Sergio caused them to mistakenly privilege the depiction of the artist’s self-interest over the needs of Revolution.

As Alea wrote more than a decade after Memories of Underdevelopment was released, “In Cuba, the Revolution is in power. This means that the conditions of struggle have changed.” Sergio’s struggle to find his place within post-Revolutionary Cuba becomes a metaphor for struggle itself. It is easy to celebrate the moment of triumph when a nation overthrows its oppressors. But a society’s problems don’t just disappear when you have regime change. Memories is the rare film that confronts the challenges faced in the aftermath of any revolution. It takes a hard look at the difficulties in remaking both a society and culture caught in the shadows of two global superpowers: the US and the USSR. In Alea himself put it:

It is to the spectator that the film should reveal the symptoms of possible contradictions and incongruities between good revolutionary intentions – in the abstract – and a spontaneous and unconscious adherence to certain – concrete – values belonging to bourgeois ideology.

Sergio simply becomes the vehicle through which Cuban audiences were encouraged to consciously grasp their own contradictions.

Alea’s insights here attest to his remarkable achievement in Memories of Underdevelopment. By exploring Cuba’s travails after Castro’s seizure of power, Alea knew that First World audiences might misinterpret the film. They might even use Memories to affirm their own imperialist identity. Yet this was not a design flaw. Instead, the film’s vulnerability would also turn out to be its greatest strength among domestic Cuban audiences. Alea’s use of cinematic devices to convey subjectivity imparts a simple but powerful lesson: the Revolution may be over, but revolutionary struggle never ends.

Thanks to Kim Hendrickson, Grant Delin, Peter Becker, and the whole Criterion team for their superb work. Also thanks to our colleague Erik Gunneson.

The text of “Toward a Third Cinema” is widely available on the Internet, as here.

The most useful resource for information on Memories of Underdevelopment remains the volume in Rutgers Films in Print series. The book contains a reproduction of the continuity script, a reprint of Edmund Desnoes’ original novella, contemporaneous reviews, and Alea’s own reflections on the film some twelve years after it was released.

The film was rereleased in 2018 after undergoing a 4k restoration. Reviews can be found here, here, here, and here. An interview with director Tomas Gutiérrez Alea can be found here. An excellent overview of Alea’s career in its entirety can be found here.

Here’s a complete listing of our Observations series on the Criterion Channel. Our installment on Hiroshima mon amour provides an intriguing comparison to this entry.

Memories of Underdevelopment (1968).

Wisconsin Film Festival: Four for the road

Suzanne Simonin, La religieuse de Denis Diderot (1966).

The Wisconsin Film Festival is over, and already we’re looking forward to the next one. In the meantime, here are our last thoughts on some films that impressed us.

Kristin here:

Dürrenmatt in Dakar

Hyenas (1992).

Senegalese director Djibril Diop Mambéty is known mostly for his two feature films, Touki Bouki (“The Hyena’s Journey,” 1973) and Hyenas (1992), and less so for a handful of shorts. Though unable to direct for long stretches of time, Mambéty, who died of cancer in 1998, has been well-served by preservationists. In 2013, Touki Bouki was released by the Criterion Collection in a box set of restorations by Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Project. Now the Cinémathèque Suisse has sponsored a 4K restoration of Hyenas. As the echoes in the two titles suggests, Hyenas was intended to be the second film in a thematic trilogy about the corruption of ordinary people by greed. The third film, Malaika, was planned, but Mambéty’s early death intervened.

Hyenas is based on Swiss playwright Friedrich Dürrenmatt’s dark 1956 comedy, Der Besuch der alten Dame, known in English as The Visit. The film follows the story of the original fairly closely, at least in the play’s first two acts.

The action is set in the village of Colobane (Mambéty’s hometown, where Touki Bouki was also set). The village has fallen on hard economic times, and the genial local shopkeeper, Dramaan, helps keep the place going by extending credit to his regular customers. City officials announce the imminent arrival of Linguère Ramatou, a Colobane woman who left the village and has become extremely wealthy. Dramaan, who had courted Ramatou in their youth, is delegated to greet and butter her up (above). She, however, accuses him of having impregnated her and refused to confess to being her baby’s father. Forced to go abroad, she became a prostitute, was severely maimed in a plane crash, and ended up rich. (How is never explained). Now she promises the villagers great financial aid if they will agree to kill Dramaan.

Although the mayor indignantly refuses, Dramaan soon notices that his fellow citizens are buying luxurious goods that they should not be able to afford. He futilely tries to get local officials to protect him from assassination. All this is played for bitter comedy by an engaging cast of non-professionals. The thematic point is made clear, especially when Mambéty intercuts a pack of hyenas lurking in the nearby brush with a mob of locals who prevent Dramaan from fleeing the town.

It helps to know something about the setting, which would be familiar to Senegalese audiences. The film gives the impression that Colobane is a remote country village. In fact it is a small arrondissement of greater Dakar, a major port on the west coast of Senegal. In a lengthy overview of the director’s life, including an interview with Mambéty shortly before his death, N. Frank Ukadike explains:

The Colobane of Hyènes is a sad reminder of the economic disintegration, corruption, and consumer culture that has enveloped Africa since the 1960s. “We have sold our souls too cheaply,” Mambéty once said. “We are done for if we have traded our souls for money. That is why childhood is my last refuge.” But what remains of Colobane is not the magical childhood Mambéty pines for. In the last shot of Hyènes, a bulldozer erases the village from the face of the earth. A Senegalese viewer, one writer has claimed, “would know what rose in its place: the real-life Colobane, a notorious thieves’ market on the edge of Dakar.”

The last shot is startling, as it reveals for the first time (at least to non-Senegalese viewers) that Colobane is located right up against a city. Possibly in Mambéty’s childhood it was a village later absorbed by the spread of Dakar. It’s not clear from the film when the action is taking place, although Ukadike suggests that it must be in the 1960s or later. The implication of the final shot is that the corruption of the villagers is as much an urban problem as a rural one–if not more so.

The restoration has resulted in vibrantly colorful images that emphasize the indigenous costumes, particularly of Ramatou and her entourage (see bottom). Metrograph is releasing the film theatrically in the US, and with luck a Blu-ray will eventually make it more widely available.

David here:

Anomalies in the space-time continuum

Vultures (2018).

Almost from the start, popular moviemaking has played tricks with linear time and space. Edwin S. Porter’s Life of an American Fireman (1903) contains both a dream and editing that replays key actions from two viewpoints. The more developed silent cinema explored flashbacks, subjective viewpoints, and other strategies. By the 1940s, filmmakers around the world were trying these tricks in sound movies, all seeking to enhance curiosity or suspense or surprise.

Most of the movies that play with space and time resolve the uncertainties clearly. The opening of Mildred Pierce skips over important moments without telling us, but by the end a flashback fills them in. This sort of gamesmanship has remained a permanent resource of mainstream cinema, especially in genres that rely on crime and mystery. Think of Pulp Fiction or Memento or The Usual Suspects, or more recently Identity, Side Effects, or the many heist movies that conceal crucial parts of the plan.

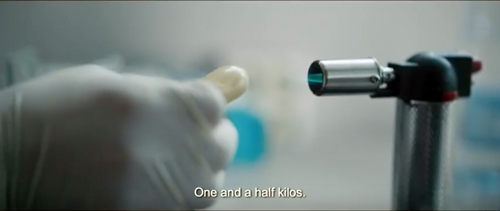

Börkur Sigpórsson’s debut feature Vultures is a good example of a conventional crime film made more intriguing by the way it’s told. The basic story is formulaic. An Icelandic real-estate developer needs to replace money he’s embezzled, and so sets up a drug-smuggling deal. He enlists his ex-con brother Atli to help the mule, a Serbian woman named Zonia, get through airport security. After that, Zonia has to be sequestered until she evacuates the pellets of cocaine she’s swallowed. In the meantime, Lena the policewoman gets on the trail. The whole scheme falls apart when Zonia collapses and Atli starts to take pity on her, while Erik decides to get the pellets by any means necessary.

This straightforward arc of action is presented in fragments that jump among time frames. Before the credits, we see Zonia hesitantly gulping down the pellets, getting sick on the flight into Reykjavík, and hiding in a toilet. She’s frightened when she hears a knock on the door.

Flash back to follow Atli and Erik planning the smuggling scheme. Then, via brief replays, we’re back with Zonia swallowing the pellets, Zonia on the plane (with Atli now revealed as a fellow passenger), and Zonia bolting to the toilet. He’s the one knocking on the door.

This sort of back-and-fill pattern sharpens our interest by delaying the revelation of who’s knocking on the door, while also filling us in on the brothers’ scheme. The interpolation also allots some sympathy to Atli. In the flashback he’s shown visiting his drug-devastated mother and trying to reassure his wife that he’s going to be providing for her and his son. Soon we see him distracting the airport police so that Zonia can pass through freely. The deal seems to have come off. All they have to do is retrieve the pellets.

Abruptly we skip far ahead in time to reveal a bit of the end of the story. I won’t provide a spoiler, but let’s just say that whatever certainty we gain about the outcome is provisional and partial. Still, with this small anchor in Now, the narration doubles back again through a long flashback that traces the unraveling of Erik’s scheme.

As often happens with flashback construction, the time-shifting in Vultures has a double impact. It teases us with hints about what will happen, and it forces us to concentrate on how and why it happens. (Something similar is at work in Duvivier’s Lydia, which I analyze in this month’s “Observations on Film Art” installment on the Criterion Channel.) Told more linearly, Vultures wouldn’t have been so engaging, I think. Nor would it have so sharply focused our concern about the characters’ decisions. And that crucial glimpse of the future allows us to hope that Zonia’s fate isn’t what it would have seemed to be if her story had been presented in 1-2-3 order. As usual, the how of storytelling is as important as the what.

During the 1950s, films not only fractured their action in challenging ways but also refused to resolve all the questions that were raised. We might not fully understand everything that happened. This strategic ambiguity has been central to what’s sometimes called “art cinema,” and is nicely showcased in Pause, another debut feature. If Vultures plays hob with the crime movie, Cypriot director Tonia Mishiali gives us a jagged domestic drama, a diary of a going-mad housewife.

Elpida is falling apart. The darkly comic opening scene, with a doctor ticking off a virtually endless list of her ailments, portrays her as enervated and beaten-down. How she got that way becomes clear. Her husband Costas shovels in food in angry silence. He watches soccer on their main TV, while she has to watch her violent crime videos with headphones. He comes and goes as he pleases; she steals time to attend a painting class or have coffee with a neighbor. When he decides to sell her car without further discussion, and when a young contractor comes to repaint their apartment house, Elpida dares to imagine life without the lout she married.

Imagine is the key word. From her drab routines we pass without warning into fantasies of resistance, escape, and payback. At first, the visual narration makes clear that these acts of rebellion are wholly in her mind. As the film goes along, however, the boundary gets fuzzy. Is the breezy workman making a pass at her, or is she just wishing for it? Is she really drugging Costas’ coffee? And is murder in the offing?

The cinematography won’t tell us. Like Vultures, Pause presents its story through a now-standard blend of planimetric framings and a “free-camera” handheld style that suggests nervous urgency. The fantasies are treated through both techniques.

A woman’s domestic discontents, projected through fantasy, has been a mainstay of cinema since at least Germaine Dulac’s Smiling Madame Beudet (1923). Here, Mishiali’s careful pacing of Elpida’s household chores establishes a solid rhythm that’s broken by the imaginary moments. Like many modern films, the drama builds up by immersing us in the characters’ routines and then disturbing them with sudden outbursts. Yet the climax is remarkably quiet, further teasing us about what may or may not have happened. In any case, by the end, Elpida may be liberated. Yet her final laughter, echoing through the end credits, doesn’t feel especially jubilant.

Get thee from a nunnery

Suzanne Simonin, La religieuse de Denis Diderot was Jacques Rivette’s second feature. In 1962 he submitted a screenplay to censorship authorities but was told that if the film were made it would probably be banned. After another try in 1963, a third version was cautiously accepted, with the warning that it might well be forbidden to viewers under 18.

Shooting began in September of 1965. Catholic groups immediately objected. After a public outcry, in which Godard called on Minister of Culture André Malraux to intervene, there was a screening at the 1966 Cannes Film Festival. The film wasn’t released in France until July of 1967. Usually known as La religieuse (The Nun), it’s gone largely unseen in America. We were lucky to screen the sparkling 4K version that Rialto is now distributing.

The story is set in the years 1757-1760. Suzanne, illegitimate daughter of a prominent household, is parked in a convent, like many women who had no other life chances. Her first Mother Superior, who treats her with affection, dies and is succeeded by a harsh younger woman. Suzanne loves God but resists the rigid discipline. She’s beaten and starved, denied access to her Bible, and believed to be possessed.

She’s rescued by church officials and a kindly lawyer, who oversee her transfer to a very different convent. That’s run by a sexy, permissive Mother Superior who seems anxious to bed our heroine. Suzanne finds the license of her new home as disquieting as the asceticism of the old one. In the end, she escapes with a priest who abandons his vows. Soon she’s on her own in a grimy secular milieu.

No wonder the French church was outraged. True, Diderot’s novel was a classic, and Rivette had already mounted the story as a play. But on film the revelation of ecclesiastical corruption was vivid and shocking, and the presence of New Wave star Anna Karina gave it undeniable prestige. Popularity, too: It attracted more than 2.9 million spectators, making it the ninth most successful release of the year. (Films by Godard, Rohmer, Bresson, Bergman, and Chabrol drew fewer than half a million.) Rivette’s first feature, Paris nous appartient (1961) had drawn only about 29,000. As often happens, creating a scandal proved good for business.

Seen today, La religieuse is hard to imagine as a mass-audience hit. Rivette presents his inflammatory plot with a calm austerity. The dominant colors, at least for the first seventy minutes or so, are shades of beige, brown, white, and black. Shot in very long takes, usually at a distance from the action, the scenes are confined largely to chapels, corridors, and sparsely furnished rooms. La religieuse exemplifies what one wing of Cahiers du cinéma called “classical” direction. As a critic, Rivette admired Hawks, Preminger, Rossellini, the American Lang, and late Dreyer for their sober, unemphatic staging of performances. In place of flashy angles and aggressive cutting, mise-en-scène should center on expressive bodies and faces captured from a respectful distance.

In a 1974 interview, Rivette explained that his most proximate influence was Mizoguchi Kenji–a director who made the restrained, long-take scene central to his style. While most scenes in La religieuse are cut up a little, Rivette seldom moves nearer than medium-shot distance. He uses close-ups with the same parsimony that Mizoguchi displays. Most directors would have cut in to a closer view of Suzanne when, kneeling, she’s asked to pray to Jesus, but Rivette obstinately makes her gesture part of a nearly two-minute shot.

This might seem a stagy approach, especially if you remember Rivette’s interest in varieties of theatre. But like other Cahiers critics, he believed that “classical” filmmaking harbored qualities that also kept cinema “modern,” on the aesthetic and moral edge.

In the abrupt editing of the long takes in Dreyer’s Gertrud (1964), Rivette found a revival of the powers of montage. Dreyer didn’t hesitate to interrupt moving shots. Rivette felt that the film exploited “tantalizing cuts, deliberately disturbing, which mean that the spectator is made to wonder where Gertrud ‘went’; well, she went in the splice.”

In La religieuse, most cuts within scenes are axial, not reverse angles, and they often mismatch action in ways that break the flow of the long takes.

At other moments, Rivette’s editing subjects his distant shots to ellipses that recall Godard’s jump-cuts and Resnais’ experiments in Muriel. We get space-time anomalies more abrasive than those in Vultures and Pause.

Suzanne is in her cell, fretfully pacing. She pauses and, thanks to a cut, seems to look at herself at prayer.

She drifts to her needlework, and suddenly a cut takes her back to the other side of the room.

While she looks in the mirror, the camera backs up and, continuing over a cut, arcs to the right to reveal that she’s already flung herself onto her bed.

Where did Suzanne go? Well, she went in the splices.

It’s wonderful to have this quietly astonishing film available again. The ever-reliable Kino Lorber is bringing out a Blu-ray edition next month, with commentary by Nick Pinkerton, a critical essay by Dennis Lim, and a new documentary about the production. Don’t you want one? I bet you do.

Thanks as usual to the coordinators of our film festival–Jim Healy, Ben Reiser, Mike King, and Zach Zahos–as well as their colleagues and the hordes of cheerful volunteers who kept everything running smoothly.

The information about Colobane from N. Frank Ukadike is from his article on California Newsreel. For a trailer of the restored Hyenas, see here.

The information on La Religieuse‘s censorship struggles comes from Jean-Michel Frodon, L’Âge moderne du cinéma français: De la Nouvelle Vague à nos jours (Flammarion, 1995), 149-151. Rivette’s comments on Mizoguchi’s influence are in this Film Comment interview from 1974. His remarks on Gertrud are part of a 1969 Cahiers du cinéma panel discussion, “Montage,” translated in Rivette: Texts and Interviews, ed. Jonathan Rosenbaum (British Film Institute, 1977), 86-87. The conversation is available online at DVDBeaver. I derived attendance figures from Simon Simsi, Ciné-Passions: 7e art et industrie de 1945 à 2000 (Dixit/CNC, 2000), 46-47.

What’s an axial cut? Glad you asked. Kurosawa uses them (here too), as does Eisenstein and his Soviet peers and French avant-gardists. Silent cinema has plenty, but so do the films of Wes Anderson and John McTiernan. And The Simpsons, often.

Our first full day of the festival opened with a screening of Ozu’s Good Morning (Ohayo), selected by guest Phil Johnston, and the final show a week later presented Jackie Chan’s Police Story. (The first is already available in a Criterion disc, the second is coming soon.) Now that’s what I call a film festival.

Hyenas (1992).

Balancing three protagonists in THE FAVOURITE

Kristin here:

Given the current year-round feverish speculation about the Oscars, it was perhaps inevitable that the campaign for performer-awards nominees for the three leading ladies of The Favourite was what drew attention to their relative prominence in the film. As Gold Derby (the website subtitled “Predict Hollywood Races”) said during the lead-up to the announcement of the nominees, “The film inspired a lot of debate in the early days of the Oscar derby as to what categories the film would campaign its three actresses [for].” Ultimately it was decided to place Olivia Colman in Best Actress and Emma Stone and Rachel Weisz in Best Supporting Actress. (For those who are interested, this story gives a detailed run-down of those occasions on which two or even three performers from the same film were nominated opposite each other in the same category.)

Esquire was one among many media outlets stating the same opinion: “Yes, Emma Stone and Rachel Weisz are both leading players in The Favourite, and yes, it’s probably category fraud that they were submitted in the supporting category to bolster Olivia Colman’s chances to win Best Actress. It is what is, and we must live with the fact that these two will get the nomination.” Indeed, that was what happened.

Stone and Weisz showed good grace in reacting to the studio’s decision–wise even without the benefit of hindsight–to campaign for Colman as the sole best-actress nominee. They did not, however, suggest that she was the sole protagonist of the film. In an interview with The Hollywood Reporter, Weisz remarked, “I think Fox Searchlight was quite brave to make a film with three really complicated female protagonists. It’s doesn’t happen every day, sadly.” Every year The Hollywood Reporter interviews prominent but anonymous Academy members about their opinions and preferences in the main categories. This year an unknown director complained of the best-actress race, “I don’t understand what [Olivia Colman’s] doing in this category, or what the other two [Emma Stone and Rachel Weisz] are doing in supporting–all three should be the same.” The notion that the three roles were roughly equal in importance was expressed widely during awards season. Google “The Favourite” and “three protagonists,” and many hits will show up in the trade and popular-press coverage.

This notion of three protagonists intrigued me. I believe that the structures of many classical narrative films depend to a considerable extent on how many protagonists they have, what those protagonists’ goals are, and what sorts of obstacles they encounter along the way–often obstacles that lead or force them to change their goals. I based my book, Storytelling in the New Hollywood (1999), partly on that idea. For close analysis I chose four exemplary films with single protagonists (Tootsie, Back to the Future,, The Silence of the Lambs, and Groundhog Day), three with parallel protagonists (Desperately Seeking Susan, Amadeus, and The Hunt for Red October), and three with multiple protagonists (Parenthood, Alien, and Hannah and Her Sisters).

Single protagonists are the commonest, and their obstacles are typically generated by single antagonists. Multiple protagonists are somewhat less so. They tend to break into at least two types. There are shooting-gallery plots like Alien, in which the protagonist is the one who, predictably or not, survives the gradual killing-off of the other main characters. Then there’s the network-of-relations plot, like Parenthood and Hannah, in which separate plotlines are acted out, with the protagonist of each related by blood or friendship to the protagonists of the others. More difficult to pull off is the multiple-protagonist plot where the characters are linked by an abstract idea and have minimal or tenuous relationships to each other–Love Actually being a masterfully woven example. (Would that it had existed when I wrote my book!)

The parallel-protagonist plot is relatively rare. I’m not talking about a film with two main characters who are closely linked and sharing the same goal. The buddy-film, most obviously two partner cops as in the Lethal Weapon films, is a common embodiment of this goal, as is the romance where the couple are in love from early on but face obstacles posed by others, as in You Only Live Once.

Parallel protagonists are not initially linked but pursue separate goals that usually bring them together. This might involve a romance conducted from afar, as in Sleepless in Seattle. One character may know the other and seek to be more like him or her, as in Desperately Seeking Susan and The Hunt for Red October. In those two cases, the main characters end by succeeding as they come together and become friends. (Hair would be another example I could have used.) In Amadeus, on the other hand, Salieri fails in his desperate attempt to replace Mozart in public favor and to essentially become him by stealing his Requiem and passing it off as his own.

The triple-protagonist plot

I never considered the category of triple protagonists, simply assuming they would belong within the multiple-protagonist films. Perhaps they do, but The Favourite raises the possibility that such films have a distinctive dynamic, somewhat akin to the parallel-protagonist plot but more complex, or at least more complicated.

Balancing two protagonists who have more-or-less equal stature in the plot is probably not much more difficult than the other types of classical plots. I think that’s largely because these two main characters can come together by the end and become the romantic couple or the buddies who could easily have been the main figures in a dual-protagonist film. Three protagonists, however, are very difficult to balance without one or two of them becoming mere supporting players by the end.

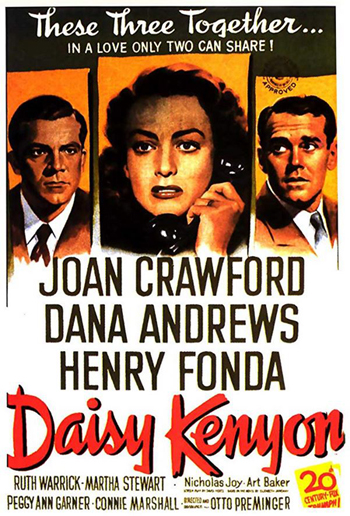

Across the history of classical filmmaking, there are probably a fair number of examples of such a balance being achieved. It’s not easy to think of more than a few, though. The first one that came to my mind is Otto Preminger’s underappreciated Daisy Kenyon (1947). In it Daisy is the mistress of a prosperous married lawyer, Dan, who refuses to divorce his wife and marry her. She meets a genial but traumatized war veteran, Peter, and marries him, but when her initial lover finally files for divorce, she is torn between the two. More about Daisy Kenyon later, the point here being that a triple-protagonist plot is not out-of-bounds for Hollywood and that two people struggling to win a third’s favors is an obvious situation to use in such a film.

The first half of The Favourite displays the long-established relationships between Queen Anne and Sarah. Sarah is stern and commanding with Anne, even cruel at times, and she runs political affairs in the Queen’s place. It is also clear, however, that the two love each other and that Anne, with her various physical and mental frailties, heavily depends on her friend. This half also traces the rise of unfairly impoverished Abigail, Sarah’s cousin. She ingratiates herself with Anne by helping nurse her gout and providing sympathy and deference; she even induces the semi-invalid Anne to dance.

Up to this point we are cued to sympathize with Abigail. She has been the innocent victim of misfortune and is treated cruelly once she arrives at court and Sarah hires her as a scullery maid. The midway turning point, as I take it, happens in the scene where Abigail shoots a pigeon and the blood spurts onto Sarah’s face. Immediately after this a servant arrives to say that the Queen is calling for Abigail rather than Sarah. Abigail is implied to have tipped the balance toward her being accepted as Anne’s favorite.

After this point, we suddenly start to see Abigail’s conniving side, and the pendulum swings as we grasp that Sarah has been displaced in the Queen’s affections through Abigail’s lies about her. In this second half, we are led to recall that Sarah, dominating though she is with Anne, truly loves her and is far more qualified to help run the state than frivolous Abigail is. By the end, all three have managed to make each other and themselves miserable, though Sarah still has her husband and manages to take exile abroad in her stride. None of them emerges as the most important character.

One might argue that Abigail functions as a conventional antagonist. After all, she drugs Sarah’s tea, nearly causing her death–and showing no compunction about it. Yet she, too, is pitiable. Her father gambled her away into marriage with a stranger, and early in the film she is bullied by the other servants. Sarah has her unlikable side and at one point attempts to blackmail Anne by threatening to make public the Queen’s love letters to her–an act that finally drives Anne to reject her. Before that rejection, however, Sarah burn the letters instead, confirming her inability to betray queen and country.

In a review on tello Films Karen Frost writes,“While Stone may receive a modicum more screen time than the other two, this movie really has three protagonists, all of whom are compelling in their own way.” I suspect a lot of spectators, including me, share this impression that Abigail is onscreen or heard from offscreen marginally more than Anne or Sarah. That said, it’s very difficult to measure the presence of each character, given how short the scenes are and how often the women come and go from the rooms where the main action is occurring. And does a scene like the one at the top of this section, where Anne and Sarah converse while Abigail stands mutely in the distance, give equal weight to all three? Perhaps, in that we are here conscious of the latter’s simmering resentment.

In a comparable scene, Abigail is pushing the Queen in a wheelchair. Anne becomes upset and tries to stagger back to her room. We follow her and concentrate on her struggle and emotions for some time before Abigail appears again with the chair. Should we consider this one scene between the two, or actually three scenes, with the two together, then Anne alone, and then the two together again? Even within scenes where two or three of the women are present, weighing their relative prominence in the scene presents difficulties.

The casting is crucial in such a film, since the relative prominence of the actors tends to affect our judgment of their characters’ importance. Rachel Weisz and Emma Stone were both Oscar-winning stars before The Favourite‘s release. Olivia Colman was not well-known in the US, but she had had a long and prominent career on television and occasional films in the UK, The Favourite‘s country of origin. Certainly as Anne she gains the audience’s sympathy early on and becomes plausible as a protagonist alongside the other two.

Scenes and twists

I decided that rather than attempt to clock screen time, I would count how many scenes each character had alone, how many involved two of them, and how many showed all three together. When I say “alone,” I mean only one of the three women is present, though often she is interacting with the main male characters, Lord Treasurer James Godolphin, Leader of the Opposition Robert Harley, and Baron Masham. Given the many very short scenes, the intercutting, the presence of the characters in the backgrounds when the others are emphasized, and the brief intrusion of a character into a scene that overall emphasizes one or two of the other women, my breakdown into segments can’t be precise.

I’ve compared the numbers of scenes devoted to the various combinations of characters in the first and second halves of the film, given the reversed situations of Sarah and Abigail in those large-scale sections.

First, the characters alone:

Anne has only 1 solo scene in the first half/3 in the second. (Total 4)

Sarah is alone 2 times in the first half/8 in the second. (Total 10)

Abigail is alone 7 times in the first half/9 in the second (Total 16)

Abigail’s larger number of scenes apart from the other two women occur largely because she is duplicitous and her situation changes drastically. Anne and Sarah behave straightforwardly, the former because she is too addled to be capable of deception and the latter because she is fundamentally honest, if sometimes brutally so.

Abigail’s duplicity must be revealed gradually. This is done to a considerable extent through two important relationships that help reveal that she is not the sweet young thing that we may have initially taken her to be. In the first half, Harley tries to bully her into acting as a spy in Anne’s bedchamber, passing on to him the political tactics and decisions of the Queen and Sarah. At first it is not clear that Abigail will comply. She also has aggressively flirtatious scenes with Masham. Initially she seems to be Harley’s victim and genuinely attracted to Masham, if in a rather eccentric fashion. Almost immediately after the midway turning point, however, Abigail passes secret information to Harley for the first time. Later, after Anne permits her to marry Masham, it is revealed that Abigail’s primary motive was to restore her lost social standing.

Scenes with Queen Anne with one or the other or both other women:

Anne with Sarah: 6 times in the first half/7 in the second (Total 13)

Anne with Abigail: 3 times in the first half/10 in the second (Total 13)

Anne with both: 6 times in the first half/5 in the second (Total 11)

Here the balance among the three protagonists becomes apparent. Whether intentionally or not, the scriptwriters gave Sarah and Abigail the same number of scenes alone with the queen. Abigail’s access to the Queen is naturally considerably greater in the second half of the film, as she gains her status as the favorite. Surprisingly, though, Sarah’s scenes with Anne are balanced between the two halves. I take this to reflect the Sarah’s determination not to be defeated and also the lingering friendship and genuine love that the two have shared since childhood. If we are to realize by the end that Anne has made a dreadful mistake by rejecting Sarah and sending her into exile, we must be reminded at intervals of how vital Sarah had been in helping Anne run the affairs of state.

The fact that Anne’s scenes with both other women are balanced between the two halves functions to allow us to continue comparing the behavior of both women toward the Queen. We slowly grasp Abigail’s perfidy and Sarah’s prickly steadfastness. The latter is made particularly poignant in Anne’s and Sarah’s final conversation, which takes place through the closed doorway of Anne’s room and ends with Anne rejecting her old friend, despite apologies and pleading.

Queen Anne is in a total of 41 scenes, Sarah in 44, and Abigail in 50, which does suggest that the latter has more screen time overall. The reason for this is probably not that she is more important, but that Sarah and Anne have an established, loving relationship at the beginning, which is easy to set up. Abigail must claw her way up from the scullery to the Queen’s bedroom, which takes more time to accomplish.

The screen time, however, is not the key factor. The film’s impact on the spectator depends to a considerable degree on our struggle to figure out which, if any, if these characters we might identify or sympathize with. There are such frequent shifts of tone and of what we know about each of them that our expectations are systematically undermined in the course of the plot.

In an interview on Deadline Hollywood, Tony McNamara, one of the scriptwriters, describes the effects of having three protagonists:

I thought it would be hard, but it was actually kind of liberating to have three, because it just gave you more options and places to go. Often, an action in a script has a reaction, but just one antagonist and protagonist. But because it’s three protagonists, there was always this cascading effect, and there were more twists. It was fun to have options, [though] there was work to do, making sure that the three were in balance, throughout.

Twists the film has in abundance. Our attitudes toward the characters change time and again. The scene in which Sarah starts letter after letter to Anne, trying to regain her favor, encapsulates all three women’s mercurial behavior. Her openings range from violent resentment (“I dreamt I stabbed you in the eye”) to fondness (“My dearest Mrs Morley”–her pet name for the Queen). The latter is the one she sends, but Abigail consigns it to the fire, finally making any reconciliation between her rival and the Queen impossible.

The ending, with its superimpositions of Anne’s rabbits over the faces of her and Abigail has been criticized as a failure to provide a satisfactory conclusion to the tale of the three protagonists. I’m not sure it is a failure of invention. Abigail’s insinuation of herself into the Queen’s favor began when she noticed the rabbits in the royal bedroom and elicited Anne’s tale of the loss of all seventeen babies she had had, with the rabbits acting as substitutes for them. Abigail had expressed an apparently deep sympathy, but in the final scene Anne sees Abigail capriciously and cruelly press her foot down on one of the rabbits. All illusions that her new favorite has loved her better than Sarah had vanish at this point, if they had not already. The two are portrayed as trapped in a relationship based on grief over unthinkable loss on the part of one and hypocritical manipulation by the other.

Preminger’s balancing act

Daisy Kenyon differs vastly from The Favourite, to be sure. Still, it’s a romantic triangle situation, and the woman who must decide between her two suitors is indecisive up until just before the ending. Dan and Peter are equally plausible as a final choice. Both have faults. Dan is content to carry on his adulterous affair with Daisy indefinitely, and Peter spies rather creepily on her after meeting her, secretly following her to a movie theater so that he can “accidentally” meet her when she comes out. Both clearly are in love with her.

Preminger also managed to cast three stars of more-or-less equal stature. Andrews had gone from supporting roles to the lead in Laura (1944) and was just coming off the success of The Best Years of Our Lives (1946). Fonda had had both leading and supporting roles since the mid-1930s and starred in such films as Young Mr. Lincoln (1939), The Grapes of Wrath (1940), The Lady Eve (1941), and My Darling Clementine (1946). There is no Ralph Bellamy, the obvious Other Man, here.

There’s another resemblance to The Favourite, in that the man Daisy ultimately chooses then says something that creates a final twist–indeed, it’s the last line of the film. He reveals that not all is as we assumed, and we may be left wondering if, like Queen Anne, Daisy may regret her choice.

Another obvious triple-protagonist film is Ernst Lubitsch’s Design for Living (1933), which once again presents a romantic triangle centering on a heroine who is understandably indecisive in choosing between Gary Cooper (George) and Fredric March (Tom). She moves in with both with an agreement that they will avoid sex. She succumbs to George’s charms when Tom is away and to Tom’s when George is away, and when jealousy between the two men breaks out, marries her rich but boring boss (Edward Everett Horton). The pre-Code ending sees Gilda back with Tom and George in an arrangement that seems no more likely to remain sexless than the first one had.

Again the casting makes the two male protagonists seem equal. March and Cooper were both rising stars at the time, with March fresh off an Oscar win for Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1932). Cooper had achieved prominence with The Virginian (1929) and followed up with Morocco (1930) and A Farewell to Arms (1932).

This is not to say that all three-protagonist films have this triangle plot with an indecisive woman as the pivot. No doubt there are all sorts of other ways to balance three lead roles. Nor is it to say that three-protagonist films are so common and distinctive as to make me go back and revise Storytelling in the New Hollywood. Still, it’s interesting to see this kind of variant played on more familiar plot structures and to study how filmmakers can go about maintaining the necessary delicate balance.

David has an analysis of Daisy Kenyon‘s narrative maneuvers in Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling.

Daisy Kenyon (1947).

Reliable narrators? Telling tales on Trump

DB here:

Ten years ago on this blogsite, I wrote about the emerging meme treating political races as a struggle among “competing narratives.” I decided to take the notion literally and applied some principles of narrative analysis to the 2008 campaign biographies of John McCain and Barack Obama. You can read the results here.

Four years later, I tried to do the same thing with the Obama/Romney race. In both postings, I studied the candidates’ storytelling styles, their efforts at characterization, and the plot structures they presented. I didn’t try to repeat the effort in 2016, because the prospect of working through Trump’s Great Again: How to Fix Crippled America (2016) or Hillary Clinton’s Hard Choices (2014) seemed like eating sawdust.

But my sensitivity feelers are twitching again because this year we’re awash in more pop narratology. By now references to The Narrative or The Alternative Narrative have become taken for granted. (As in: “Mr. Soros has been elevated by Mr. Trump and his allies to even greater prominence in the narrative they have constructed for the closing weeks of the 2018 midterm elections.”) What’s emerging is another notion swiped from the analyst’s toolkit: the Unreliable Narrator.

Wayne Booth, in The Rhetoric of Fiction (1961) appears to have invented the term. It’s become very common; Google lists over 629,000 mentions. Its meaning seems self-evident, but it can still be misunderstood. Some writers seem to think that any first-person narrator is inherently unreliable. Everybody is biased, right? But Booth intended the term to refer to narrators, first-person or not, that cunningly mislead us through such tactics as ellipsis, equivocation, faulty judgment, and outright lying. In film we encounter unreliable narration very often, as in the opening of Mildred Pierce (1945) or the initial voice-over in Confidence (2003).

Booth and the critics who followed him have shown the idea to be a useful tool of literary analysis. And now it’s become politicized. An NPR opinion piece is called “President Donald Trump, Unreliable Narrator” and compares Trump’s Twitter feed to the deluded and deceitful narration of Nabokov’s Pale Fire.

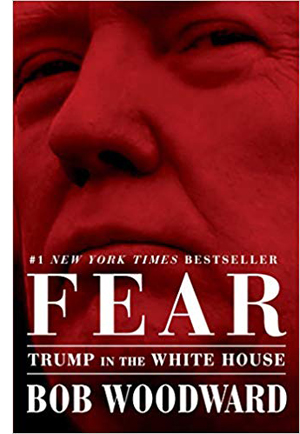

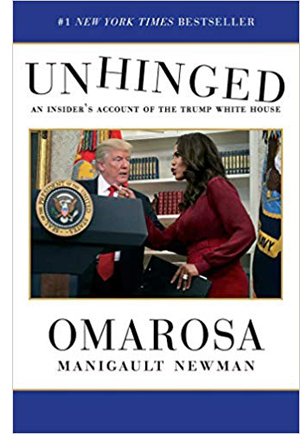

The issue of unreliability has come to the fore in three of the biggest-selling accounts of our monstrous presidential regime: Bob Woodward’s Fear: Trump in the White House, Michael Wolff’s Fire and Fury: Inside the Trump White House, and Omarosa Manigault Newman’s Unhinged: An Insider’s Account of the Trump White House.

I’ll consider them as narratives, while warning you, as before, that I’m not very concerned with tracking down their factual accuracy. That’s an important task, but I want simply to study what Booth might call the rhetoric of nonfiction. By looking at each book’s plot structure (yes, they have plots) and narration, I want to understand how narrative analysis can help us better understand what counts as “reliability.” Fortunately for my purposes, the books nicely illustrate three different models of storytelling.

Truth’s gold standard: Washington’s Recording Angel

Many mainstream reviewers seem to have assumed that Woodward’s book wins the reliability award. The Washington Post review, written by a member of Harvard’s English department, notes:

His utter devotion to “just the facts” digging and his compulsively thorough interviews, preserved on tape for this book, make him a reliable narrator. In an age of “alternative facts” and corrosive tweets about “fake news,” Woodward is truth’s gold standard.

What makes Woodward seem so reliable? Partly it’s his research method. Publicly available sources and on-the-record interviews are cited in endnotes, but the real meat comes from “deep background,” an arrangement in which the subject willingly supplies information with the promise that she or he will not be identified. We trust that what Woodward tells us is based on what his sources told him, although of course we then have to trust what they said.

This aspect of reliability requires us to accept Woodward-the-narrator as a figure of scrupulous probity. He does everything he can to sustain this sense. He doesn’t even rely on his memory to report what he said on television.

Two days before the election, November 6, I appeared on Fox News Sunday with Chris Wallace. The discussion turned to the possibility that Trump could win.

According to the transcript, I said on the show….(44).

This appeal to personal trust is enhanced by a ruthless simplicity of style. Woodward writes short sentences, short paragraphs, and short chapters. The gray, graceless prose, adorned with times and dates like a Dragnet episode, seems to guarantee neutrality. Here are two complete paragraphs.

At about 9 p.m. Monday, November 27, more than four months after Priebus left the White House, the president reached him on his cell phone. They talked for 10 minutes (287).

In a meeting in January 2018, Navarro, Ross, Cohn and Porter gathered in the Oval Office. After months of arguing about tariffs from entrenched positions, debates had become heated and sharp (334).

My Word for Mac program lists these passages as readable at the 8.8 grade level. This is narrative transparency par excellence, flat and factual and a little clichéd (entrenched positions, heated debates). The irrelevant realistic detail (a conversation lasts 10 minutes, not 9 or 11) adds to the sense of verisimilitude. Even venturing into mental terrain is done guardedly.

Trump seemed not to remember his own decision because he did not ask about it. He had no list–in his mind or anywhere else–of tasks to complete (233).

Trump seems, to an unknown observer, to forget his decisions. The following claim about his list-less mind becomes not a plunge into his psyche but a commonsense inference based on his work habits.

Woodward enhances trust by building the story out of scores of conversation scenes. Each of the 42 chapters consists of several incidents, presented with minimal intervention by the narrating voice. It’s as if a tape recorder is playing history back for us.

This strategy can produce powerful scenes. I won’t soon forget the lengthy efforts of John Dowd, Trump’s attorney, to rehearse his client testifying before Mueller. Over four pages, Trump reveals himself incapable of sticking to the point or telling the truth. In desperation (“Don’t testify. It’s either that or an orange jump suit”), Dowd goes to Bob Mueller and instructs his colleague Jay Sekulow to reenact highlights of the president™’s audition. After Sekulow executes a torrent of rambling, contradictory replies (“a perfect Trump”), Dowd brays, “Gotcha!” and explains that his client obviously can’t be dragged in. This Brechtian skit leaves Mueller largely unmoved.

Occasionally the objective surface is broken by the thoughts of selected participants. When this happens, Woodward’s reported conversations flow along like a pulp novel or a sitcom screenplay. Steve Bannon calls on Paul Manafort in Trump Tower.

Manafort’s place was beautiful. Kathleen Manafort, his wife, an attorney who was in her 60s but looked to Bannon like she was in her 40s, was wearing white and lounging like Joan Collins, the actress from the show Dynasty. . . .

[Manafort shows Bannon a draft of a New York Times story.]

“Twelve million fucking dollars in cash out of the Ukraine!” Bannon virtually shouted.

“What?” Mrs. Manfort said, bolting upright.

“Nothing, honey,” Manafort said. “Nothing.”

“When is this coming out?” Bannon asked.

“It may go up tonight.”

“Does Trump know anything about this?”

Manafort said no.

“How long have you known about this?”

Two months, Manafort said, when the Times started investigating.

Bannon read about 10 paragraphs in. It was a kill shot. It was over for Manafort (21).

This works by creating a POV character. It’s not Woodward but Bannon, ex-Hollywood bottom-feeder, who seems to be making the Joan Collins connection while talking/thinking like a second-tier hitman in Get Shorty.

Still, turbocharging other encounters in this way might seem a risky strategy. How is the reporter to gain our credence? How is he able to produce for our delectation pages of exact dialogue? Who remembers conversations so exactly? And how has Woodward reconciled the witnesses’ different recollections? “Deep background” supplies the material, but how much has Washington’s Recording Angel shaped the disparate stories he’s heard?

Still, turbocharging other encounters in this way might seem a risky strategy. How is the reporter to gain our credence? How is he able to produce for our delectation pages of exact dialogue? Who remembers conversations so exactly? And how has Woodward reconciled the witnesses’ different recollections? “Deep background” supplies the material, but how much has Washington’s Recording Angel shaped the disparate stories he’s heard?

Henry James, reacting against the loquacious authorial-voice narrators of Dickens and Thackeray, argued that the novelist could learn from the playwright. A play doesn’t include a chatty narrator; the characters are on their own. “Dramatize it, dramatize it!” Roll out the novel’s action in “discriminated occasions,” concrete scenes that reveal the characters’ traits and desires through behavior–gestures, looks, speech. This presentation is subtler and more realistic than a commenting narrator’s explications. The reader has to work a little more to judge what she sees and hears, just as we do in real life. And there’s more artistry in implying the undercurrent of motives than in letting a godlike narrator state them baldly.

The admonition to dramatize went along with another Jamesian premise, that of limited viewpoint. Restrict what the reader knows to a “center of consciousness,” a single intelligence who registers the action played out. That viewpoint might be sustained for an entire story or novel, or it might be confined to a single chapter, with another chapter taking up another character’s perspective. Again, realism is enhanced (this is how we see the world, through a single mind), but so is artistry. There’s a skill to arranging your plot so as to let its implications register gradually on a character. (Especially when, as in “In the Cage” or What Maisie Knew, there are severe limits on the character’s knowledge.) Now the story would be about how characters try to understand and judge situations, and how their inferences shape their reactions.

James’s ideas were developed and formularized in Percy Lubbock’s The Craft of Fiction (1921), and they became commonplace in modern writing. We are so used to them that going back to read the classic nineteenth-century novels brings us up short: long paragraphs of authorial commentary can seem forbidding. Elmore Leonard’s laconic crime sagas epitomize the modern taste: “Try to leave out the parts that readers tend to skip.”

Bob Woodward is no James or Dutch Leonard, but he builds Fear out of “discriminated occasions” presented as dramatic clashes among characters. He also occasionally filters those scenes through the reactions of participants, as in the Bannon scene above. By following broad mandates of twentieth-century literary technique, Woodward gains the reliability of a unified fiction.

As in a novel, readers of Fear tap into several minds–not just Bannon’s and Dowd’s, as above, but those of other major players like Gary Cohn, Reince Priebus, James Clapper, and Rob Porter. The arc of the book, most of which covers the period from August 2016 to March 2018, surveys their activities planning policy and responding to Trump’s mischief and Mueller’s investigation. There seems little doubt that these gentlemen, all eventual exiles from the Trump White House, were the prime sources of Woodward’s narrative. As if in payback, our author breaks the impersonal surface to offer a mildly approving comment about them.

At the very start, amid a lump of exposition, Gary Cohn’s impressive credentials and bold initiative are spotlighted.

In early September 2017, in the eighth month of the Trump presidency, Gary Cohn, the former president of Goldman Sachs and the president’s top economic adviser in the White House, moved cautiously toward the Resolute Desk in the Oval Office (xvii).

Cohn is swiping a disastrous letter that would terminate a free-trade agreement with South Korea. By burying it in a file, he keeps the chief executive from signing it, and Cohn trusts (correctly) that his boss will just forget. “I stole it off his desk,” he explains. “. . . . Got to protect the country.”

Cohn’s surreptitious heroism is abetted by Rob Porter, staff secretary and Trump gatekeeper. This “6-foot-4, rail-thin” Mormon “ordinarily tried to remain an honest broker who facilitated the discussion” (335). Porter weaves through the narrative, and we get his muted reactions to meetings. A scandal thrusts him out the door, but Woodward treats the alleged wife-beater with bland gentility.

Porter quickly concluded it would be best for all–his former spouses, his family and close friends, the White House and himself–to resign. He wanted to focus on repairing relationships and healing (336).

Woodward inserts this into a studiously tame account of the allegations and Porter’s public reply, but there is a difference between writing this passage and writing: “He said he wanted to focus on…” Woodward’s phrasing tacitly aligns us with Porter. And who can condemn someone who likes “relationships and healing”?

Woodward is sometimes characterized as working in the space between journalism and history. I suggest that his techniques are borrowed from fiction as well. He uses the tactics of post-Jamesian literary narrative to dramatize his plot, to attach us to privileged centers of consciousness, and to secure our trust. Fear reads like a summer beach page-turner because, in its construction, it is.

Exaggerating the exaggerations

Cagle Cartoons, via The Brooklyn Eagle.

Michael Wolff, by contrast, is untrustworthy, according to many reviews. This one in The Atlantic is widely quoted online, perhaps because its author is Adam Kirsch, himself a novelist.

If Michael Wolff is writing fiction in Fire and Fury, this is the kind of fiction he is writing. Indeed, at the very beginning of the book, in an author’s note, Wolff declares himself an unreliable narrator: “Many of the accounts of what has happened in the Trump White House are in conflict with one another; many, in Trumpian fashion, are baldly untrue. Those conflicts, and that looseness with the truth, if not with reality itself, are an elemental thread of the book,” he writes. The traditional promise of the journalist is to find the single, fundamental truth obscured by all the partial, biased accounts he elicits. But Wolff explicitly declines to make that promise; he offers not the story but a whole chorus of stories.

But in the passage quoted, Wolff doesn’t actually claim to be unreliable. He isn’t asserting that his book is endlessly juggling incompatible accounts. Kirsch neglects to quote the sentences that follow the passage he picked out:

Sometimes I have let the players offer their versions, in turn allowing the reader to judge them. In other instances I have, through a consistency in accounts and through sources I have come to trust, settled on a version of events I believe to be true (xii).

So no less than Woodward, Wolff is committed to finding out the truth. But he admits, as Woodward never does, that constructing an accurate account, in the face of disparities and incomplete information, can’t always be done. Some conclusions can be fairly well-founded, while others must be tentative and still others must be suspended. For example, Wolff borrows from Franklin Foer a set of possible reasons that Trump cozies up to Putin. Wolff offers what evidence he can for each hypothesis, but doesn’t rule any out, and he suggests that many may be at work at the same time.

In sum, Woodward’s story world is transparent, Wolff’s intermittently opaque, but both grant that there’s something out there to be seen. This isn’t what Kirsch calls “a perfectly Postmodern White House book.” More like Citizen Kane or The Thin Blue Line, I guess, than Last Year at Marienbad.

Just as Woodward’s narrative relies on our trust in him as the ultimate fair-minded chronicler, Wolff trades on his reputation as a somewhat sensationalistic media commentator. The author of a scathing biography of Rupert Murdoch, he’s often spoken of as a “columnist” rather than a journalist–a slight I take as a way of dismissing him. But he explains that he got access to this shambolic White House in a way that the orthodox press couldn’t. He just walked in and sat around and drifted into offices to listen to what people said.

Wolff claims, as Woodward does, to have nabbed these leakers’ comments on tape. So those who valorize Woodward’s meticulous recording ought to equally prize Wolff’s efforts. I expect, though, that Wolff’s reputation and his more gonzo enterprise cast doubt on his reporting. Yet despite a few minor errors of fact widely reported in the reviews, nobody has to my knowledge shown fatal shortcomings in Wolff’s account. It corresponds closely to that of Woodward, and it shows a degree of skepticism, analysis, and brutal humor which the the staid Woodward never displays.

Wolff’s time span is tighter than Woodward’s, running from Election Day (8 November 2016) through August 2017, with an epilogue in October. Woodward’s episodic vignettes trace White House activities chronologically and topically; chapters are devoted to Russian hacking, Middle Eastern initiatives, tariffs, and the like. Although the chapters are untitled, you can practically see the labels on Woodward’s file drawers. Fire and Fury works in larger chunks: half the number of chapters, tagged with titles indicating either a specific time frame (the transition, “Day One”) or a topic or, in many cases, a player (“McMaster and Scaramucci”).