Archive for the 'Narrative strategies' Category

Vancouver 2018: Crime waves

Burning (2018).

DB:

It’s striking how many stories depend on crimes. Genre movies do, of course, but so do art films (The Conformist, Blow-Up) and many of those in between (Run Lola Run, Memento, Nocturnal Animals). The crime might be in the future (as in heist films ), the ongoing present (many thrillers), or the distant past (dramas revealing buried family secrets).

Crime yields narrative dividends. It permits storytellers to probe unusual psychological states and complex moral choices (as in novels like Crime and Punishment, The Stranger). You can build curiosity about past transgressions, suspense about whether a crime will be revealed, and surprise when bad deeds surface. Crime has an affinity with another appeal: mystery. Not all mysteries involve crimes (e.g., perhaps The Turn of the Screw), and not all crime stories depend on mystery (e.g., many gangster movies). Still, crime laced with mystery creates a powerful brew, as Dickens, Wilkie Collins, John le Carré, and detective writers have shown.

We ought, then, to expect that a film festival will offer a panorama of criminal activity. Venice did last year and this, and so did the latest edition of the Vancouver International Film Festival. Some movies were straightforward thrillers, some introduced crime obliquely. In one the question of whether a crime was committed at all led–yes–to a full-fledged murder.

Smells like teen spirit

Diary of My Mind.

Start with the package of four Swiss TV episodes from the series Shock Wave. Produced by Lionel Baier, these dramas were based on real cases–some fairly distant, others more recent, all involving teenagers. The episodes offer an anthology of options on how to trace the progress of a crime.

In Sirius a rural cult prepares for a mass suicide in expectation they’ll be resurrected on an extraterrestrial realm. The film focuses largely on Hugo, a teenager turned over to the cult by his parents. Director Frédéric Mermoud gives the group’s suicide preparations a solemnity that contrasts sharply with the food-fight that they indulge in the night before. Similarly, The Valley presents a tense account of a young car thief pursued by the police. Locking us to his consciousness and a linear time scheme, director Jean-Stéphane Bron summons up a good deal of suspense around the boy’s prospects of survival in increasingly unfriendly mountain terrain.

Sirius and The Valley give us straightforward chronology, but First Name Mathieu, Baier’s directorial contribution, offers something else. A serial killer is raping and murdering young men, but one of his victims, Mathieu, manages to escape. The film’s narration is split. Mathieu struggles to readjust to life at home and at school, while the police try to coax a firm identification from him. This action is punctuated by flashback glimpses of the traumatic crime. The result explores the parents’ uncertainty about how restore the routines of normal life, the police inspector’s unwillingness to press Mathieu too hard, and the boy’s self-consciousness and guilt as the target of the town’s morbid curiosity.

This insistence on the aftereffects of a crime dominates Diary of My Mind, Ursula Meier’s contribution to the series. This too uses flashbacks, mostly to the moments right after a high-school boy kills his mother and father. But there’s no whodunit factor; we know that Ben is guilty. The question is why. Ben’s diary seems to offer a decisive clue (“I must kill them”), but just as important, the magistrate thinks, is his creative writing under the tutelage of Madame Fontanel, played by the axiomatic Fanny Ardent. Because she encouraged her students to expose their authentic feelings, Ben’s hatred of his father had surfaced in his classroom work. Perfectly normal for a young man, she assures the magistrate. No, he asserts: a warning you ignored. The shock waves that engulf onlookers after a crime, the suggestion that art can be both therapeutic and dangerous, the question of a teacher’s duty to both her pupils and the society outside the classroom–Diary of My Mind raises these and other themes in a compact, engaging tale.

Last hurrah of (movie) chivalry

Chinese director Jia Zhangke is no stranger to criminal matters. His films have dwelt on street hustles, botched bank robberies, and hoodlums at many ranks. Ash Is Purest White is a gangster saga, tracing how a tough woman, Qiao, survives across the years 2001-2018. Initially the mistress of boss Bin, Qiao rescues him from a violent beatdown using his pistol. She takes the blame for owning a firearm. Getting out of prison, Qiao tracks down the now-weakened Bin, who has taken up with another woman.

Ash Is Purest White tackles a familiar schema, the fall of a gang leader, from the unusual perspective of the woman beside him, who turns out to be stronger than he is. Most of the film is filtered through her experience, and along with her we learn of Bin’s decline and betrayal, along with his integration into the corrupt and bureaucratic capitalism of twenty-first century China. The second half of the film shows Qiao forced to survive outside the gang’s milieu. A funny scene plays out one of her scams: picking a prosperous man at random, she announces that her sister, implicitly his mistress, is pregnant. Just as important, Qiao’s adventures allow Jia to survey current mainland fads and follies, including belief in UFO visits.

Among those follies, Bin suggests, is a trust in mass-media images. As Ozu’s crime films (Walk Cheerfully, Dragnet Girl) suggested that 1930s Japanese street punks imitated Warner Bros. gangsters, so Jia’s mainland hoods model themselves on the romantic heroes of Hong Kong cinema. They raptly watch videos of Tragic Hero (1987) and cavort to the sound of Sally Yeh’s mournful theme from The Killer (1989). They derive their sense of the jianghu--that landscape of mountains and rivers that was the backdrop of ancient chivalry–not from lore or even martial-arts novels but from the violent underworld shown on TV screens.

Bin’s decline is portrayed as abandoning those ideals of righteousness and self-sacrifice flamboyantly dramatized in the movies. But Qiao clings to the imaginary jianghu to the end. She explains to him that everything she did was for their old code, but as for him: “You’re no longer in the jianghu. You wouldn’t understand.” You can respect his pragmatism and admire her tenacity, but he’s still a feeble figure, and she’s left running a seedy mahjongg joint–one much less glamorous than the club she swanned through at the film’s start. Appropriately for someone who got her idea of heroism from videos, we last see her as a speckled figure on a CCTV monitor.

From dailiness to darkness

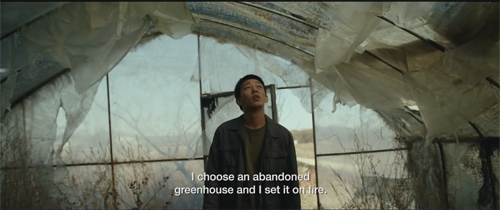

Burning.

Often the crime in question is presented explicitly, but two films leave it to us to imagine what shadowy doings could have led to what we see. In Manta Ray, by Phuttiphong “Pom” Aroonpheng, we get the familiar motif of swapped identity. A Thai fisherman finds a wounded man in the forest and nurses him back to health. The victim is a mute Rohinga whom the fisherman names Thongchai. They share a home and the occasional dance and swim, even a DIY disco.

But who attacked Thongchai in the forest, and why? And what is the connection to the unearthly gunman who paces through the forest, bedecked in pulsating Christmas bulbs? And what makes the foliage teem with gems glowing in the murk? Somewhere, there has been a crime.

Manta Ray accumulates its impact gradually, with the scenes of the men’s routines giving way to mystery when the fisherman vanishes and Thongchai (named by the fisherman for a Thai pop singer) is trailed by a ninja-like figure clad in a red cagoule. A disappearance and a reappearance (of the fisherman’s wife) punctuate moody scenes of trees and sea. The opacity of the action makes a political point: offscreen, Thais brutally hunt down the refugee Rohingas. But the critique of anti-immigrant brutality is intensified by the lustrous cinematography (Aroonpheng was a top DP). You can feel the texture of the planks in the cabin and the sharp edges of the gems that fingers root out of the forest floor. This is probably the most tactile movie I saw at VIFF.

Then there was Lee Chang-dong’s Burning. Lee started his career strong and has stayed that way. The slowly paced, Kitanoesque gangster story Green Fish (1997) and Peppermint Candy (1999), with its reverse-order chronology, both achieved local popularity and established him as a fixture on the festival circuit. Oasis (2002), a daring romance of a disabled couple, won a special prize at Venice. Secret Sunshine (2007) brought Lee even more widespread fame. Like the episodes of Shock Waves, it dealt with the aftereffects of a horrific crime. Virtually everyone I know who saw the film remembers most vividly a particular scene: the heroine, having converted to Christianity and at last ready to forgive the perpetrator, visits him in prison. It’s one of the most nakedly blasphemous scenes I’ve ever seen, carried off with a shocking calm. Crime–this time, a gang rape–is also at the center of Poetry (2010), with another mother facing familial tragedy.

Most of these plots, particularly Poetry, are rather busy, but Burning is more stripped down (though not short). Lee Dong-su maintains the shabby family farm while his father is in jail awaiting trial. In town Dong-su meets Haemi, a former classmate now running sidewalk giveaways.

She lures him into her life by asking him to feed her cat while she’s in Africa, but before she leaves they start an affair. But he seldom breaks into a smile, favoring a puckered-lip passivity. After their coupling, we get his POV on a blank wall.

This turns out to be the first of many disquieting passages. Between bouts of tending livestock, feeding Haemi’s cat, and masturbating to her picture, Dong-su gets mysterious phone calls with no one on the line. He meets Haemi at the airport only to discover that she’s formed a friendship (or more?) with the suave Ben, whose gentle courtesy makes Dong-su feel an even bigger bumpkin. Soon the three are hanging out together, but at parties Dong-su can only stare at Ben’s yuppie friends. Dong-su, who wants to be a writer, is a fan of Faulkner, but Ben compares himself to the Great Gatsby.

After a long night of relaxing at the farm, with the men watching Haemi dance topless, she disappears. A black frame, a dream of a burning greenhouse, and Dong-su is left alone halfway through the movie. What happened to Haemi? And why does Ben say he enjoys torching greenhouses? Dong-su turns detective,

Lee is a master of pacing, and the deliberateness of the film delicately turns a romantic drama into a critique of entitled lifestyles and then into a psychological thriller. We are locked to Dong-su’s consciousness except for a couple of telltale shots of Ben calmly studying his rival from afar. We get Vertigo-like sequences of Dong-su trailing Ben and probing for clues and perhaps having more dreams. At the same time, Dong-su starts writing, as if Haemi’s disappearance has inspired him, but he finds more violent ways to release his simmering bewilderment.

After only one viewing, I didn’t find Burning as devastating a film as Secret Sunshine or Poetry, but I’d gladly watch it again and probably I’d see more in it. Lee manages to sustain over two and a half hours a plot centering on three, then two principal characters. He has earned the right to soberly take us into the mundane rhythm of a loner’s life and then shatter that through an encounter with two enigmatic figures who may be playing mind games. As with Manta Ray, we have to infer some of the action behind the scenes, but that just shows that in cinema, classic or modern, crime can pay.

Thanks as ever to the tireless staff of the Vancouver International Film Festival, above all Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, Shelly Kraicer, Maggie Lee, and Jenny Lee Craig for their help in our visit.

Snapshots of festival activities are on our Instagram page.

Japadog, a Vancouver landmark.

On the Criterion Channel: Five reasons why HIROSHIMA MON AMOUR still matters

Often this scandalous or honorable story, this beautiful or ugly one, will be told you the next day or the next month, sometimes in fragments. There is nothing that is of a piece in this world, everything is a mosaic.

Balzac, Une fille d’Ève

DB here:

We’re not big fans of listicles. Our only effort in this direction is our annual review of the 10 best movies of 90 years ago. But now we have my Criterion Channel installment devoted to Hiroshima mon amour. (There’s a sample here.) The installment is focused on the film’s use of editing. That topic does allow me to touch on wider matters of storytelling and theme, but I found myself struggling to squeeze in all I wanted to say. So. . . .

If you haven’t seen the film, both this and the Criterion Channel segment will teem with spoilers. Now I’ll give a plot synopsis, but the shocks in the film’s early stretches are probably softened if you know the story’s premises. So if you haven’t seen the film yet, you’re advised to stop reading now.

Hiroshima mon amour, the 1959 feature film directed by documentarist Alain Resnais, tells the story of a brief sexual affair between an unnamed man and woman. She has come to Hiroshima to make a film about the effects of the US nuclear bombing of the city in 1945. Her plane is scheduled to leave the following day, but he asks her to stay longer in Japan. As a result, what drama there is becomes psychological—pressured by her deadline, but complicated by her memories.

After their first night of lovemaking, she tries to break with him, but in the course of the day he pursues her and they meet at intervals. They go to his house for another bout of lovemaking, to a bar called the Tea Room, to the train station, and back to her hotel, where the film began. In the course of their affair, she recalls and recounts her wartime romance with a German soldier stationed in her city of Nevers. At the liberation, he was shot by a sniper. The townsfolk punished her by cropping her hair and confining her in a cellar.

In a gesture characteristic of ambitious cinema of the period, we don’t definitely learn that the woman decides to leave. The final scene, suggesting that she will always think of the man as Hiroshima, does imply that they’re parting. More important, in the course of their affair she has realized that her memories of her first love are fading, and she fears that makes her deeply disloyal to him. Worse, she feels that she’s already forgetting her Japanese lover. The passage of time and the waning of emotion come to feel like a betrayal.

Hiroshima is one of the most important films ever made, summing up many tendencies of modern cinema but also indicating new directions for later filmmakers. Its implications and possibilities radiate out in several directions, like the spidery silhouette (in negative?) under the opening credits. So a listicle format seems, for once, justified.

(1) The opening

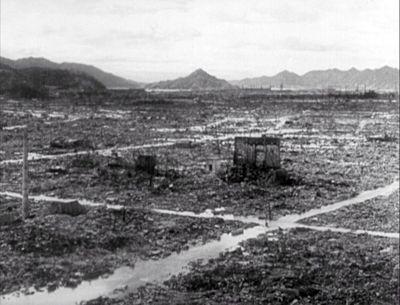

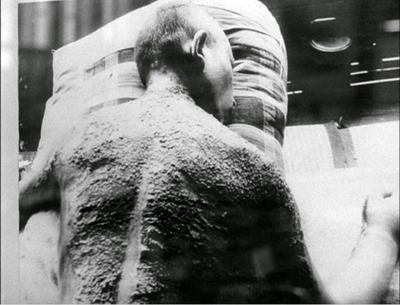

Two bodies, from the waist up, are locked in an embrace. The faces aren’t visible. At first, the bodies are powdered with dust but as the images dissolve into one another, the limbs are glittering and then oily with sweat.

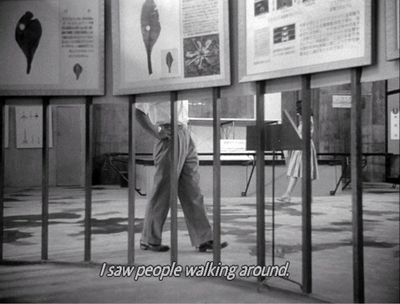

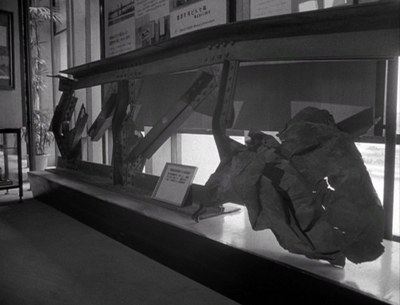

These images give way to documentary-style shots of Hiroshima, both in the present and in newsreel footage. We see modern architecture, a hospital, museum exhibits, city streets, a cheerful lady bus conductor, victims of the nuclear blast, and even restaged scenes of the bombing’s aftermath, taken from fiction films.

Over all the footage float a male voice and a female voice: “You saw nothing in Hiroshima–nothing.” “I saw it all…” She describes what can be seen and understood, while he contradicts her. We return intermittently to their bodies. The sequence concludes with her voice: “I met you here.”

Thus ends one of the most daring sequences in film history, a dense thirteen minutes of imagery, music, and dialogue. I think it’s hard for us today to grasp just how jolting this opening felt in 1959. Ten years after its premiere, when I first saw it (and without much foreknowledge), I was overwhelmed. For me, and I think for many others, cinema wasn’t quite the same after this.

For one thing, there’s the sex. Although it’s portrayed abstractly, the voluptuous skin tones and clutching, twisting arms are powerfully erotic–and poetic. The oily skin might be considered realistic, but the dust particles can’t be justified as anything but metaphorical, perhaps nuclear fallout or the ashes of a city in flames. (Is this like the embracing couples discovered in Pompeii by the heroine of Voyage to Italy?) Later the sexual angle will become more socially specified; it’s an “interracial” coupling, involving a French woman with a Japanese man. An entire “social problem” movie could be made about this situation, which this film takes utterly for granted.

Then there’s the juxtaposition of this stylized intercourse with the bombing of Hiroshima–and naked bodies very different from the ones we see in bed. We’re given smooth tracking shots through a hospital and a museum. In some of his documentaries Resnais had presented locales in solemn, slightly disquieting traveling shots, mimicking a tourist-eye view into a library (Toute la mémoire du monde, 1956) or a concentration camp (Nuit et brouillard/ Night and Fog, 1956). Here, similar traveling shots are more or less anchored to the unseen woman reporting on her impressions.

I say more or less because, in a slippage characteristic of the film, sometimes the camera height is lower than an adult’s eye level, as in the second shot above. And often the camera is withdrawing along the line of the museum exhibits, as if looking backward.

Already the imagery is rendered a little detached from a human perspective. More generally, by suppressing the woman’s face and eliminating diegetic sound, the shots for all their concreteness seem unreal, as if pulled up from memory or imagination.

When the shots segue to found footage (“I saw the newsreels”) and then to strident reenactments, those too seem less historical records or blatant fictionalizing than part of a phantasmagoric vision.

Maps and twisted relics, faces and stones, kitsch and authentic suffering are all put on the same plane, with a disturbing neutrality.

Perhaps this is the tragedy of Hiroshima as absorbed by a consciousness unequal to it. But what consciousness could comprehend it? Night and Fog openly proposed that our minds couldn’t grasp the enormity of the Holocaust. Not that this was a counsel of despair; our very helplessness was a warning to remain vigilant against the next glimpse we might get of human monstrousness. Here another voice challenges the limits of our sympathetic imagination: “You saw nothing.”

What about the opening’s soundtrack? Plaintive piano music, Debussy-ish, passes to strings and woodwinds–slow and brooding, but sometimes disarmingly bouncy. Nothing could be farther from the Mahleresque scores of Hollywood cinema or most documentaries than this chamber-music intimacy. The score pulls a bit away from the images, we might say, seldom emphasizing them even at their most horrific.

In his documentaries, Resnais had pioneered a lyrical, somewhat dry voice-over quite different from the conventional nudging or hectoring Voice-of-God commentary. Like the tracking shots, though, this vocal technique takes on a new effect in a fictional cinema. For one thing, when and where is the conversation occurring? Not evidently during the lovemaking. Before? After? Maybe never? Is it a sort of telepathic exchange, expressing the essence of her tourist-level days in the city and then his assured sense that such an experience blinded her to the real Hiroshima? Interestingly, we’ll learn that he wasn’t in Hiroshima during the attack. So perhaps he, like the narrator of Night and Fog, is warning her against premature confidence in understanding any historical event on this scale.

The woman’s voice dominates the soundtrack, meditating on her lover and her surroundings. Again, it might be a monologue addressed to the man at some point, but thanks to rushing shots through Hiroshima streets, it equates his body with his city. This motif will culminate at the climax, when she compresses her memories of 1944 down to landscapes in Nevers and she decides to give her lover a name: Hiroshima.

Since the mid-1940s, André Bazin had argued that the future lay with long take-filming that respected the continuum of reality–the continuum that Soviet filmmakers had freely splintered in order to make rhetorical and poetic points. Yet with this overture, Hiroshima revived and revamped the Soviet tradition of montage-based moviemaking. The sequence averages a little more than six seconds per shot, a rate seldom seen in European fictional film of the 1950s. The result somewhat recalls the free editing of Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera, but it anchors the visual disjunctions in psychology and a personal drama yet to be specified.

Bazin had worried that by chopping the world into little fragments, editing by its nature ruled out ambiguity of expression. Yet here was a film that showed, as avant-garde filmmakers had done, that montage could generate poetic ambiguity. Editing patterns could create analogies and associations. The spatter on a rock could evoke the scars on a victim’s head, and the dusted couple of the opening could become ghostly doubles of a victim of radiation.

One could even intercut staged footage and documentary material without hiding the filmmaker’s artifice (as Citizen Kane does with the faked footage in “News on the March”). Free montage and collage-like mixing of documentary and fiction would be hallmarks of 1960s and 1970s films by Alexander Kluge, Dušan Makavejev, and of course Jean-Luc Godard.

Something similar happened with the soundtrack. Detached, unemphatic scores would become part of the repertoire of modern cinema, as would floating voice-overs. Films like Chungking Express and Wings of Desire, to say nothing of the work of (again) Godard, would show the expressive power of voices cut free from story time and space. Montage, as Eisenstein prophesied juxtaposed not only image to image but image to sound.

No later passage of Hiroshima mon amour is as aggressively disorienting as this overture. It’s as if Psycho started with the shower sequence. This opening not only introduces a lot of cinematic and thematic material. It also seeks to sensitize us to images and sounds, as a poem at the start of a novel might sensitize us to language. My discussion of editing in the Criterion installment points out that most of the ensuing film is cut in a pretty orthodox way, respecting the rules of continuity construction. But the sheer disjunctiveness of this prologue prepares us to notice whatever abruptness and juxtapositions do arrive. Assailed by this opening, at once jagged and eerily smooth, we’re set to register some even finer-grained shifts in time and sequence to come.

(2) Flashbacks that aren’t flashbacks

Hiroshima’s script by Marguerite Duras was, Resnais claimed, based on “parallel editing” that would link wartime France and contemporary Japan. But Resnais insisted that this editing didn’t create flashbacks.

Here is another movie, one that Resnais and Duras didn’t make. A French woman visiting Hiroshima on a film shoot turns tourist. She then meets a Japanese man and they have sex. Next day she avoids him, but he pursues her and eventually she agrees to spend the evening with him. In a bar we get the big reveal: the woman explains her wartime love affair and the punishment that drove her out of Nevers. Her past episodes are given in large blocks, perhaps one long flashback. The plot concludes with the man and the woman forced to choose their future.

We’ve already seen that the woman’s tourist-eye view has been fragmented, scrambled, and stylized in the opening montage. We might be tempted to call those images flashbacks, were they not so firmly part of an overall collage including purely documentary material. But once the story proper begins, we, or at least I, am inclined to call the bursts of images from 1944 Nevers flashbacks–brief ones, but flashbacks.

I say this because I take the primary purpose of a flashback is to present story material out of chronological order. A secondary purpose, not always in force, is to represent a character’s memories. Some films, especially after Pulp Fiction, rearrange story order without appeal to character memory. In classical studio cinema, though, flashbacks are usually motivated by a character recalling or recounting an event that she remembers. More often than not the scenes we see in the past aren’t restricted to what she witnesses or even knows about. Memory provides a rationale for the main purpose–revealing action in the past.

But there’s a contrary line of thought that says that a character’s memory ought not to count as a flashback because memories exist in the present. Arthur Miller took this line with respect to the time-shifts in his play Death of a Salesman, as I discuss in Reinventing Hollywood. Resnais, it turns out, felt the same way. For him, the fragments of the past that interrupt the present-time scenes of Hiroshima exist in the present because they’re being remembered. He wrote to Duras during shooting: “The past won’t be expressed by true flashbacks, but will be felt to be present throughout.” In 1968 he reiterated: “In Hiroshima there is not a second’s worth of flashbacks.”

There’s no point in quibbling about terms, but we should note that Resnais thought his interruptive images of the past were capturing something important about how memory works. Memory is fragmentary and jumbled, not operating in the big chronological blocks given us in 1940s Hollywood flashbacks. When asked by his producer if Citizen Kane hadn’t already shifted chronology, Resnais replied: “Yes, but with me, it’s all disordered.”

Moreover, memory is abrupt and fragmentary: Resnais uses cuts, not dissolves, to deliver his memory images. The first instance in the film has become a locus classicus. The woman sees her Japanese lover’s hand twitch, and that leads to another hand, a quick pan to a dead man being kissed, and then the Japanese lover again. This time-shift is literally a flash, lasting only a few frames.

And to insist that memory operates in the present moment, Resnais uses present-time diegetic noise–a train whistle in the scene above, a pop tune on a jukebox later–providing something that literature can’t: the absolutely simultaneous presence of now and then.

Again, Resnais brings into sound cinema narrative strategies that had emerged in silent film. Gance in La Roue, Fredrikh Ermler in Fragments of an Empire, and others had provided rapid-fire memory montages. In most commercial sound cinema, this sort of mental imagery was largely confined to one-off sequences depicting dreams, hallucinations, or mental illness. Resnais and Duras boldly made an entire film in which recollected moments unexpectedly erupt into present-tense action.

Again, though, the filmmakers introduce ambiguity. It’s hard to plausibly assign some of the “memories” of Nevers to the female protagonist. Bare landscapes and abrupt tracking shots of empty streets seem more like Eliot’s “objective correlative,” more oblique representations of feelings, than traces of what the woman has witnessed. Even the invasive images from the past aren’t free of the uncertainties that hover over the opening sequence. This strategy of hovering between subjectivity and “authorial commentary” would become central to 1960s art cinema–perhaps most obviously in Red Desert, where the unrealistic color can be taken as both an expression of the protagonist’s alienation or a more detached, stylized presentation of a modern wasteland.

(3) Talkies and walkies

Griping about Antonioni’s longueurs, Dwight Macdonald remarked that “the talkies have become the walkies.” His complaint captures something important. From Bicycle Thieves through La Strada and L’Avventura up to Linklater’s Before/After trilogy, the idea of building a plot around two characters’ more or less mundane traipsing became a salient option for filmmakers who wanted to stray from classical narrative organization.

But settling down in one place to talk became important too. Serious European cinema often featured dialogue scenes of a length that would have been discouraged in American cinema. Play adaptations like Sjöberg’s Miss Julie (1951) naturally featured such protracted conversations, but so did works by Bergman such as Waiting Women (1952), Wild Strawberries (1957), and Brink of Life (1958). Having revived silent-film montage in Hiroshima‘s early stretches, Resnais and Duras makes peace with their contemporaries in the second part by settling their characters down for two good chats broken by a long stroll.

It all starts when the man declares, after a second bout of lovemaking, that they have sixteen hours to kill before her departure. By Hollywood standards, this period should be handled with dramatic crises leading to the deadline. Instead, we get a quick montage of the city at dusk (with figures unnaturally still, as if rehearsing for walk-on parts in Last Year at Marienbad) and the two of them at a table in the Tea Room bar.

It’s in this lengthy scene that the woman’s memories become most coherent for us and the man. What was private in earlier parts of the film–flashes like the hand on the bed–become externalized in her confession. Again, though, we get Resnais’s version of “disorder.” For one thing, her Nevers story isn’t given in a block, but rather as a burst of fragments. After their second lovemaking, she had already begun to tell her lover about her affair with the German, and the editing was rather choppy: six alternations of past and present in about seven minutes. Now at the Tea Room she’s more explicit about his fate and her punishment. Over twenty-four minutes, the action alternates between Hiroshima and Nevers seventeen times. Often a single shot breaks into her confession.

For another thing, the incidents remembered tumble out of order. Glimpses of her imprisoned in a basement are followed by her ritual haircutting before being sent there. Image and sound fall out of true: we see her pedaling to Paris, we hear her telling us what she read in the newspapers upon arriving. We need to integrate what she’s recounting now with what she’s recalled earlier.

By the time the couple leave the Tea Room, we have a fairly coherent account of the woman’s Nevers trauma. In our alternative film, we’d now have a climax in which she decides to leave Hiroshima or stay. Instead, she and the man separate. She returns to her hotel, washes her face, accuses herself of betraying her German lover with the Japanese, and. . . wanders back outside.

She returns to the Tea Room, now closed. The plot’s irresolution is prolonged. Her lover materializes, as if summoned by her voice-over. The woman, now distraught, tells him she’ll stay. Immediately she tells him to leave. He says he could never leave her. Then he leaves her.

What follows is a string of further evasions and encounters, almost a suite of variations on how a couple can seek to connect and avoid connecting. The film becomes a walkie. Resnais planned the street scenes, he explained in a letter to Duras, by listening to a tape of her reading the commentary and blocking the actors’ movements with wooden dolls.

The woman moves down the street, trailed by her lover. He follows her to a train station, and then to a bar called–you must remember this–Casablanca. She eludes him by letting a slick stranger join her for a drink. The night goes on. Dawn arrives.

In the course of these stop-and-start ramblings, memories return, but images of her lover dwindle, to be replaced by those of Nevers; he has faded into the landscape. As I indicated, these might as well be narrational commentary rather than her memories, with the film’s overarching form juxtaposing the French city with the Japanese one in ways she doesn’t yet grasp.

Now you know why people say art movies seem never to end: They tease us with closure and then deny it. Extended talk scenes and walk scenes, however realistic they may seem in contrast with busy Hollywood plots, are also conventions of this mode of filmmaking. It’s up to the filmmakers to shape them to their immediate purposes.

(4) At the limit

In a plot centered on action–goals, blockages, clashes among characters, struggles to accomplish some feat–you typically have a clear-cut climax and resolution. The protagonist either succeeds or fails. But when you deny that sort of arc, you have to find other ways to inject drama. In Hiroshima, we have a classic instance of the undecided protagonist, who can’t settle on a goal and so drifts from situation to situation, each one of which dramatizes a facet of her character, or of her indecision.

Sooner or later, the plot has to stop, so if there’s no decisive way to end the action, how do you conclude? The most favored option, borrowed from serious literature, involves what literary theorist Horst Ruthrof calls a “boundary situation.” Instead of creating a resolution by what the protagonist accomplishes, the plot confronts the character with something that forces a reevaluation of his or her life. The drama is psychological, not physical; the resolution involves insight, not action of the normal sort. As Ruthrof puts it, the character “in a flash of insight become[s] aware of meaningful as against meaningless existence.” The boundary situation is existential, consisting of “a final vision or revelation, rejection of false moral premises, and the gain of a state of authenticity.”

James Joyce called such bursts of recognition “epiphanies,” and he employed them in his Dubliners short stories. Ruthrof argues persuasively that they can be found throughout modern European literature, from Flaubert and Tolstoy to Conrad and Thomas Mann. In Narration in the Fiction Film, I proposed that many films in the European tradition had recourse to boundary-situation plots. Guido’s acceptance of all the contradictions of his life in 8 ½ and Isak Borg’s reconciliation with his past in Wild Strawberries are fairly clear examples.

Instances of boundary situations are central to two Marguerite Duras novels of the period. The Square (1955) consists of routine encounters on a park bench between an unnamed man and woman. They talk at length each time, and the climax comes when the man declares suddenly, “I’m a coward.” Moderato Cantabile (1956) is set in a cafe, and the conversations are broken by time shifts to piano lessons and a party. Again we get laconic exchanges between a man and woman who don’t know each other, culminating in confession and tears. (“I wish you were dead.”/ “I am.”) Resnais said that he wanted to work with Duras after reading Moderato Cantabile.

In Hiroshima, what, finally, provides closure for the plot? Not the woman’s decision to stay or not; we never know what she chooses. Instead, her affair has forced her to psychological crisis. She realizes that her memories of her first love are partial and impermanent. This shocks her as an act of disloyalty. And she feels that she’s already forgetting her Japanese lover. The passage of time and the waning of emotion come to feel like a betrayal.

The film’s climax is a personal epiphany, not a clear-cut showdown. The woman has come to accept that her past and present are ephemeral, that even the memories she’s making now–of the lover whose skin she adores–will wane. What remains? The late sequences that take her wandering through his city cement the relation between his body and the town: her voice-over repeats the exultant incantation that opened the film, but now we hear it over shots of neon signs and empty streets. So she can name the man: “Hiroshima.” And although we have never had privileged access to his mind, the fact that he rejoiced in hearing her story of her past, in being the only person she had told of it, he may well have achieved a similar epiphany. He reciprocates, calling her “Nevers. Nevers in France.”

This is of course just one interpretation. Whatever thematic implications a critic constructs from the film, though, I think that those will depend on acknowledging the transformative boundary situation that functions as a climax. The woman’s confrontation with the man and the city has forced her to a self-recognition, putting her life in a new light.

Cinema of character rather than plot, we sometimes call it. I’d rather say it’s a particular breed of plot, one that replaces achievement of external goals with achievement of partial, tentative, but still life-transforming insight. A different dramaturgy for a different tradition.

(5) Consolidating innovations

Voyage to Italy; La Pointe Courte.

Hiroshima mon amour changed the way movies told their stories, not least because it revised some trends that had emerged in two other European films of the 1950s.

One was Roberto Rossellini’s Voyage to Italy (released late 1954). Despite featuring two major American stars, Ingrid Bergman and George Sanders, it was far from an ordinary Hollywood picture. It pushed further that conception of “plotless,” anecdotal narrative on display in Neorealist films like Paisá and Umberto D. The center of the tale is a couple whose marriage is quietly dying. Having inherited a villa in Naples, the characters must decide to sell it. But instead of building a conflict out of this goal, the film fills itself with episodes of the husband’s philandering and the wife’s touring of the region. It settles its plot by an epiphany in which man and wife are mysteriously reconciled.

Voyage to Italy, wrote Jacques Rivette, “opens a breach. . . . All cinema, on pain of death, must pass through it.” “The story is loose, free, full of breaks,” said Eric Rohmer, “and yet nothing could be further from the amateur. I confess my incapacity to define adequately the merits of a style so new that it defies all definition.” Rivette again: “Here is our cinema, those of us who in our turn are preparing to make films (did I tell you, it may be soon).”

The Cahiers du cinéma critics weren’t so eager to welcome Agnès Varda’s La Pointe Courte (1956). A married couple drifts through a fishing village, and their meditations on their life together are woven into documentary recording of the locals’ work and relaxation. André Bazin championed the film, but others in the Cahiers team were cool, objecting to the stylized photography and performances. The fact that it was made by a woman probably didn’t help. Against Varda’s wishes Cahiers ran a photo of her as a martyred angel, and it’s hard not to see it as mockery, especially since the caption revels in Henri Agel’s “wicked manhandling” of the film in his review.

Because La Pointe Courte was produced by a company registered to make only short films, it couldn’t achieve commercial distribution and so circulated mostly to ciné-clubs. But most reviews were praising, and today it’s recognized as a bold anticipation of the Nouvelle Vague.

Among those films that La Pointe Courte anticipates is Hiroshima. Resnais, was editor on La Pointe Courte. He initially resisted the job, telling Varda: “Your explorations are too close to mine,” but he wound up working for free.

Three films about couples, then, rendered in a strikingly episodic way. All use long walks and extended talks. All three display a dual structure as well. Rossellini intercuts the activities of husband and wife. Varda, influenced by the parallel structure of Faulkner’s novel Wild Palms, alternates scenes of village life with the couple’s wanderings. And as we’ve seen, Resnais asked Varda to build Hiroshima upon an editing strategy that set the past against the present.

There are probably other antecedents of the film (Resnais was reminded of Il Grido when cutting La Pointe Courte), but I hope I’ve said enough to indicate how Resnais recasts an emerging tradition of ambitious European cinema. He goes beyond it in all the ways I’ve mentioned and more I haven’t, but like all art works it owes part of its power to its reworking of techniques it inherits.

We could list more reasons that this film endures, certainly. Not least: Its unforgettably enigmatic title. Even that offers us ambiguous fragments, in something like an abrupt cut. “Hiroshima mon amour” might suggest “I love the city of Hiroshima.” But there’s no punctuation, no comma or dash that would equate the two terms. Instead, we might take it as a splice. It might be a contrast: “Hiroshima” versus “my love, the German soldier.” But then, since the Japanese comes to stand in for the German, the title would equate “Hiroshima” to him. This would be consistent with the final dialogue: “Hiroshima, that’s your name.” The film’s very title implies the ambivalent juxtapositions that Resnais will build up through cutting.

Thanks as ever to Peter Becker, Kim Hendrickson, Grant Delin, and their colleagues at Criterion for making this installment. Thanks as well to old friend Erik Gunneson and to Kelley Conway for discussion of Resnais and Varda. Our entire Criterion Channel series is here.

Bazin’s worries that montage lacked ambiguity are set forth in various essays in What Is Cinema? vol. I, ed. and trans. Hugh Gray (University of California Press, 1967), particularly “The Evolution of the Language of Cinema,” 36.

Resnais’s comments about Hiroshima‘s avoidance of flashbacks are quoted in Jean-Louis Leutrat, Hiroshima mon amour, 2nd ed. (Armand Colin, 2006), p. 84. He describes his film’s “disorder” in conversation with Anatole Dauman, quoted in Jacques Gerber, Souvenir-Écran: Anatole Dauman, Argos Films (Pompidou, 1989), 86-87. He mentions his use of puppets to plan his staging in a letter reprinted in Tu n’as rien vu à Hiroshima, ed. Marie-Christine de Navacelle (Gallimard, 2009), 66. This lovely edition shouldn’t be confused with Tu n’as rien vu à Hiroshima!, ed. Raymond Ravar (Brussels: Institut de Sociologie, Université Libre de Bruxelles, 1962). This remarkable volume is a detailed book-length analysis of the film and includes interviews with Resnais.

Horst Ruthrof’s discussion of boundary situations appears in The Reader’s Construction of Narrative (Routledge, 1981), 101-108.

See Cahiers du cinéma: The 1950s: Neo-Realism, Hollywood, New Wave, ed. Jim Hillier (Harvard University Press, 1985), 192-208, for Rivette and Rohmer on Voyage to Italy. The macho mockery of Varda occurs in Cahiers no. 56 (February 1956), 29. For a comprehensive discussion of La Pointe Courte, see Kelley Conway, Agnès Varda (University of Illinois Press, 2015), 9-26. We consider Kelley’s book and Varda’s film here

In Narration in the Fiction Film, I argue that the ambiguous interplay of objective realism, subjective projection, and external narrational commentary is a major strategy of “modernist” cinema or “art cinema.” That argument is sketched in an earlier essay available here, with an update. See also the blog entry, “How to watch an art movie, reel 1.”

I played awhile with the idea that the floating voice-overs in the opening sequence might have been Duras’s efforts to capture what Nathalie Sarraute described as sous-conversation, the unarticulated subtexts that shape what we actually say. The historical timing fits, as Sarraute’s essay positing the possibility, “Conversation and sous-conversation,” appeared in early 1956. (See Sarraute, The Age of Suspicion: Essays on the Novel, trans. Maria Jolas, Braziller, 1963). But I’m not fully convinced of a direct debt. More generally, though, Sarraute’s insistence that the contemporary novel must replace external action with dialogue that hints at internal states seems in accord with the way Duras and Resnais conceived Hiroshima. Maybe here the image track does duty for Sarraute’s “subterranean conversation”? And perhaps the idea of sous-conversation is more relevant to Duras’s own films, particularly the masterpiece India Song (1975).

Hiroshima mon amour.

Is there a blog in this class? 2018

24 Frames (2017)

Kristin here:

David and I started this blog way back in 2006 largely as a way to offer teachers who use Film Art: An Introduction supplementary material that might tie in with the book. It immediately became something more informal, as we wrote about topics that interested us and events in our lives, like campus visits by filmmakers and festivals we attended. Few of the entries actually relate explicitly to the content of Film Art, and yet many of them might be relevant.

Every year shortly before the autumn semester begins, we offer this list of suggestions of posts that might be useful in classes, either as assignments or recommendations. Those who aren’t teaching or being taught might find the following round-up a handy way of catching up with entries they might have missed. After all, we are pushing 900 posts, and despite our excellent search engine and many categories of tags, a little guidance through this flood of texts and images might be useful to some.

This list starts after last August’s post. For past lists, see 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, and 2017.

This year for the first time I’ll be including the video pieces that our collaborator Jeff Smith and we have since November, 2016, been posting monthly on the Criterion Channel of the streaming service FilmStruck. In them we briefly discuss (most run around 10 to 14 minutes) topics relating to movies streaming on FilmStruck. For teachers whose school subscribes to FilmStruck there is the possibility of showing them in classes. The series of videos is also called “Observations on Film Art,” because it was in a way conceived as an extension of this blog, though it’s more closely keyed to topics discussed in Film Art. As of now there are 21 videos available, with more in the can. I won’t put in a link for each individual entry, but you can find a complete index of our videos here. Since I didn’t include our early entries in my 2017 round-up, I’ll do so here.

As always, I’ll go chapter by chapter, with a few items at the end that don’t fit in but might be useful.

[July 21, 2019: In late November, 2018, the Filmstruck streaming service ceased operation. On April 8, 2019, it was replaced by The Criterion Channel, the streaming service of The Criterion Collection. All the Filmstruck videos listed below appear, with the same titles and numbers, in the “Observations on Film Art” series on the new service. Teachers are welcome to stream these for their classes with a subscription.]

Chapter 3 Narrative Form

David writes on the persistence of classical Hollywood storytelling in contemporary films: “Everything new is old again: Stories from 2017.”

In FilmStruck #5, I look at the effects of using a child as one of the main point-of-view figures in Victor Erice’s masterpiece: “The Spirit of the Beehive–A Child’s Point of View”

In FilmStruck #13, I deal with “Flashbacks in The Phantom Carriage.”

FilmStruck #14 features David discussing classical narrative structure in “Girl Shy—Harold Lloyd Meets Classical Hollywood.” His blog entry, “The Boy’s life: Harold Lloyd’s GIRL SHY on the Criterion Channel” elaborates on Lloyd’s move from simple slapstick into classical filmmaking in his early features. (It could also be used in relation to acting in Chapter 4.)

In FilmStruck #17, David examines “Narrative Symmetry in Chungking Express.”

Chapter 4 The Shot: Mise-en-Scene

In choosing films for our FilmStruck videos, we try occasionally to highlight little-known titles that deserve a lot more attention. In FilmStruck #16 I looks at the unusual lighting in Raymond Bernard’s early 1930s classic: “The Darkness of War in Wooden Crosses.”

FilmStruck #3: Abbas Kiarostami is noted for his expressive use of landscapes. I examine that aspect of his style in Where Is My Friend’s Home? and The Taste of Cherry: “Abbas Kiarostami–The Character of Landscape, the Landscape of Character.”

Teachers often request more on acting. Performances are difficult to analyze, but being able to use multiple clips helps lot. David has taken advantage of that three times so far.

In FilmStruck #4, “The Restrain of L’avventura,” he looks at how staging helps create the enigmatic quality of Antonionni’s narrative.

In FilmStruck #7, I deal with Renoir’s complex orchestration of action in depth: “Staging in The Rules of the Game.”

FilmStruck #10, features David on details of acting: “Performance in Brute Force.”

In Filmstruck #18, David analyses performance style: “Staging and Performance in Ivan the Terrible Part II.” He expands on it in “Eisenstein makes a scene: IVAN THE TERRIBLE Part 2 on the Criterion Channel.”

FilmStruck #19, by me, examines the narrative functions of “Color Motifs in Black Narcissus.”

Chapter 5 The Shot: Cinematography

A basic function of cinematography is framing–choosing a camera setup, deciding what to include or exclude from the shot. David discusses Lubitsch’s cunning play with framing in Rosita and Lady Windermere’s Fan in “Lubitsch redoes Lubitsch.”

In FilmStruck #6, Jeff shows how cinematography creates parallelism: “Camera Movement in Three Colors: Red.”

In FilmStruck 21 Jeff looks at a very different use of the camera: “The Restless Cinematography of Breaking the Waves.”

Chapter 6 The Relation of Shot to Shot: Editing

David on multiple-camera shooting and its effects on editing in an early Frank Capra sound film: “The quietest talkie: THE DONOVAN AFFAIR (1929).”

In Filmstruck #2, David discusses Kurosawa’s fast cutting in “Quicker Than the Eye—Editing in Sanjuro Sugata.”

In FilmStruck #20 Jeff lays out “Continuity Editing in The Devil and Daniel Webster.” He follows up on it with a blog entry: “FilmStruck goes to THE DEVIL”,

Chapter 7 Sound in the Cinema

In 2017, we were lucky enough to see the premiere of the restored print of Ernst Lubitsch’s Rosita (1923) at the Venice International Film Festival in 2017. My entry “Lubitsch and Pickford, finally together again,” gives some sense of the complexities of reconstructing the original musical score for the film.

In FilmStruck #1, Jeff Smith discusses “Musical Motifs in Foreign Correspondent.”

Filmstruck #8 features Jeff explaining Chabrol’s use of “Offscreen Sound in La cérémonie.”

In FilmStruck #11, I discuss Fritz Lang’s extraordinary facility with the new sound technology in his first talkie: “Mastering a New Medium—Sound in M.”

Chapter 8 Summary: Style and Film Form

David analyzes narrative patterning and lighting Casablanca in “You must remember this, even though I sort of didn’t.”

In FilmStruck #10, Jeff examines how Fassbender’s style helps accentuate social divisions: “The Stripped-Down Style of Ali Fear Eats the Soul.”

Chapter 9 Film Genres

David tackles a subset of the crime genre in “One last big job: How heist movies tell their stories.”

He also discusses a subset of the thriller genre in “The eyewitness plot and the drama of doubt.”

FilmStruck #9 has David exploring Chaplin’s departures from the conventions of his familiar comedies of the past to get serious in Monsieur Verdoux: “Chaplin’s Comedy of Murders.” He followed up with a blog entry, “MONSIEUR VERDOUX: Lethal Lothario.”

In Filmstruck entry #15, “Genre Play in The Player,” Jeff discusses the conventions of two genres, the crime thriller and movies about Hollywood filmmaking, in Robert Altman’s film. He elaborates on his analysis in his blog entry, “Who got played?”

Chapter 10 Documentary, Experimental, and Animated Films

I analyse Bill Morrison’s documentary on the history of Dawson City, where a cache of lost silent films was discovered, in “Bill Morrison’s lyrical tale of loss, destruction and (sometimes) recovery.”

David takes a close look at Abbas Kiarostami’s experimental final film in “Barely moving pictures: Kiarostami’s 24 FRAMES.”

Chapter 11 Film Criticism: Sample Analyses

We blogged from the Venice International Film Festival last year, offering analyses of some of the films we saw. These are much shorter than the ones in Chapter 11, but they show how even a brief report (of the type students might be assigned to write) can go beyond description and quick evaluation.

The first entry deals with the world premieres of The Shape of Water and Three Billboards outside Ebbing, Missouri and is based on single viewings. The second was based on two viewings of Argentine director Lucretia Martel’s marvelous and complex Zama. The third covers films by three major Asian directors: Kore-eda Hirokazu, John Woo, and Takeshi Kitano.

Chapter 12 Historical Changes in Film Art: Conventions and Choices, Traditions and Trends

My usual list of the ten best films of 90 years ago deals with great classics from 1927, some famous, some not so much so.

David discusses stylistic conventions and inventions in some rare 1910s American films in “Something familiar, something peculiar, something for everyone: The 1910s tonight.”

I give a rundown on the restoration of a silent Hollywood classic long available only in a truncated version: The Lost World (1925).

In teaching modern Hollywood and especially superhero blockbusters like Thor Ragnarok, my “Taika Waititi: The very model of a modern movie-maker” might prove useful.

Etc.

If you’re planning to show a film by Damien Chazelle in your class, for whatever chapter, David provides a run-down of his career and comments on his feature films in “New colors to sing: Damien Chazelle on films and filmmaking.” This complements entries from last year on La La Land: “How LA LA LAND is made” and “Singin’ in the sun,” a guest post featuring discussion by Kelley Conway, Eric Dienstfrey, and Amanda McQueen.

Our blog is not just of use for Film Art, of course. It contains a lot about film history that could be useful in teaching with our other textbook. In particular, this past year saw the publication of David’s Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Hollywood Storytelling. His entry “REINVENTING HOLLYWOOD: Out of the past” discusses how it was written, and several entries, recent and older, bear on the book’s arguments. See the category “1940s Hollywood.”

Finally, we don’t deal with Virtual Reality artworks in Film Art, but if you include it in your class or are just interested in the subject, our entry “Venice 2017: Sensory Saturday; or what puts the Virtual in VR” might be of interest. It reports on four VR pieces shown at the Venice International Film Festival, the first major film festival to include VR and award prizes.

Monsieur Verdoux (1947)

The eyewitness plot and the drama of doubt

Looking is as important in movies as talking is in in plays. Thanks to optical point-of-view shots (POV) and reaction-shot cutting, you can create a powerful drama without words.

Everybody knows this, but sometimes it’s good to be reminded. (I did that here long ago.) Now I have another occasion to explore this terrain. But first: How I spent my summer vacation.

After Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato, I went to the annual Summer Film College in Antwerp. (Instagram images here.) I’ve missed a couple of sessions (the last entry is from 2015), but this year I returned for another dynamite program. There were three threads. Adrian Martin and Cristina Álvarez López mounted a spirited defense of Brian De Palma’s achievement. Tom Paulus, Ruben Demasure, and Richard Misek gave lectures on Eric Rohmer films. I brought up the rear with four lectures on other topics. As ever, it was a feast of enjoyable cinema and cinema talk, starting at 9:30 AM and running till 11 PM or so. The schedule is here.

After Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato, I went to the annual Summer Film College in Antwerp. (Instagram images here.) I’ve missed a couple of sessions (the last entry is from 2015), but this year I returned for another dynamite program. There were three threads. Adrian Martin and Cristina Álvarez López mounted a spirited defense of Brian De Palma’s achievement. Tom Paulus, Ruben Demasure, and Richard Misek gave lectures on Eric Rohmer films. I brought up the rear with four lectures on other topics. As ever, it was a feast of enjoyable cinema and cinema talk, starting at 9:30 AM and running till 11 PM or so. The schedule is here.

Because I was fussing with my own lectures, I missed the Rohmer events, unfortunately. I did catch all the De Palma lectures and some of the films. Cristina and Adrian offered powerful analyses of De Palma’s characteristic vision and style. I especially appreciated the chance to watch Carlito’s Way again (script by friend of the blog David Koepp) and to see on the big screen BDP’s last film Passion, which looked fine. I confess to preferring some of his contract movies (Mission: Impossible, The Untouchables, Snake Eyes) to some of his more personal projects, but he takes chances, which is a good thing.

Two of my lectures had ties to my book Reinventing Hollywood. “The Archaeology of Citizen Kane” (should probably have been called “An Archaeology…) pulled together things touched on in blogs, topics discussed at greater length in books, and things I’ve stumbled on more recently. Maybe I can float the newer bits and pieces here some time.

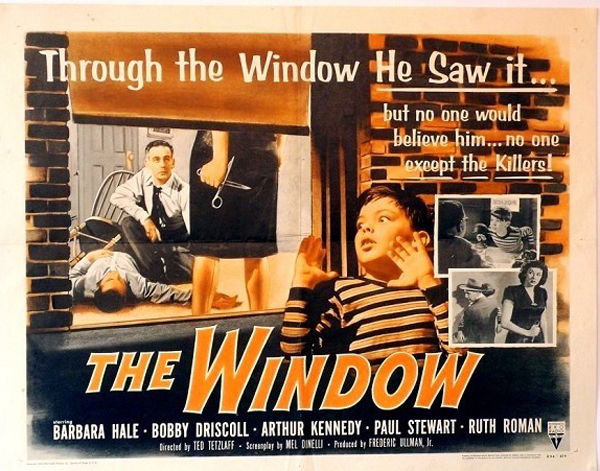

The other lecture took off from my book’s discussion of the emergence of the domestic thriller in the 1940s. We screened The Window (1949), a film that I hadn’t studied closely before. If you can see or resee it before reading on, you might want to do that. But the spoilers don’t come up for a while, and I’ll warn you when they’re impending.

Exploring the how

It is to the thriller that the American cinema owes the best of its inspirations.

Eric Rohmer

One strand of argument in Reinventing Hollywood goes like this.

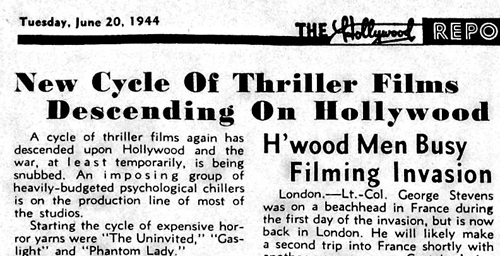

During the 1930s Hollywood filmmakers mostly concentrated on adapting their storytelling traditions to sync sound and to new genres (the musical, the gangster film). By 1939 or so, those problems were largely solved. As a result, some ambitious filmmakers returned to narrative techniques that were fairly common in the silent era but had become rare in talkies. Those techniques–nonlinear plots, subjectivity, plays with viewpoint and overarching narration–were refined and expanded, thanks to sound technology and quite self-conscious efforts to create more complex viewing experiences.

Wuthering Heights, Our Town, Citizen Kane, How Green Was My Valley, Lydia, The Magnificent Ambersons, Laura, Mildred Pierce, I Remember Mama, Unfaithfully Yours, A Letter to Three Wives, and a host of B pictures and melodramas and war films and mystery stories and even musicals (Lady in the Dark) and romantic comedies (The Affairs of Susan)–all these and more attest to new efforts to tell stories in oblique, arresting ways. They seem to have taken to heart a remark from Darryl F. Zanuck (right). It forms the epigraph of my book:

Wuthering Heights, Our Town, Citizen Kane, How Green Was My Valley, Lydia, The Magnificent Ambersons, Laura, Mildred Pierce, I Remember Mama, Unfaithfully Yours, A Letter to Three Wives, and a host of B pictures and melodramas and war films and mystery stories and even musicals (Lady in the Dark) and romantic comedies (The Affairs of Susan)–all these and more attest to new efforts to tell stories in oblique, arresting ways. They seem to have taken to heart a remark from Darryl F. Zanuck (right). It forms the epigraph of my book:

It is not enough just to tell an interesting story. Half the battle depends on how you tell the story. As a matter of fact, the most important half depends on how you tell the story.

Put it another way. Very approximately, we might say that most 1930s pictures are “theatrical”–not just in being derived from plays (though many were) but in telling their stories through objective, external behavior. We infer characters’ inner lives from the way they talk and move, the way they respond to each other in situ. And the plot thrusts itself ever forward, chronologically, toward the big scenes that will tie together the strands of developing action. In this respect, even the stories derived from novels depend on this external, linear presentation.

In contrast, a lot of 1940s films are “novelistic” in shaping their plots through layers of time, in summoning a character or an omniscient voice to narrate the action, and in plunging us into the mental life of the characters through dreams, hallucinations, and bits of memory, both visual and auditory. We get to know characters a bit more subjectively, as they report their feelings in voice-over, or we grasp action through what they see and hear.

The distinction isn’t absolute. Some of these “novelistic” techniques were being applied on the stage as well, as a minor tradition from the 1910s on. I just want to signal, in a sketchy way, Hollywood’s 1940s turn toward more complex forms of subjectivity, time, and perspective–the sort of thing that became central for novelists in the wake of Henry James and Joseph Conrad.

In tandem with this greater formal ambition comes what we might call “thickening” of the film’s texture. Partly it’s seen in a fresh opennness to chiaroscuro lighting for a greater range of genres, to a willingness to pick unusual angles (high or low) and accentuate cuts. The thickening comes in characterization too, when we get tangled motives and enigmatic protagonists (not just Kane and Lydia but the triangles of Daisy Kenyon or The Woman on the Beach). There’s also a new sensitivity to audiovisual motifs that seem to decorate the core action–the stripey blinds of film noir but also symbolic objects (the snowstorm paperweights in Kane and Kitty Foyle, the locket in The Locket, the looming portraits and mirrors that seem to be everywhere). Add in greater weight put on density and details of staging, enhanced by recurring compositions, as I discuss in an earlier entry.

One genre that comes into its own at the period relies heavily on the new awareness of Zanuck’s how. That’s the psychological thriller.

I’ve written at length about this characteristic 1940s genre (see the codicil below), so I’ll just recap. The 1930s and 1940s saw big changes in mystery literature generally. The white-gloved sleuth in the Holmes/Poirot/Wimsey vein met a rival in the hard-boiled detective. Just as important was the growing popularity of psychological thrillers set in familiar surroundings. The sources were many, going back to Wilkie Collins’ “sensation fiction” and leading to the influential works by Patrick Hamilton (Rope, Hangover Square, Gaslight). In the same years, the domestic thriller came to concentrate on women in peril, a format popularized by Mary Roberts Rinehart and brought to a pitch by Daphne du Maurier. The impulse was continued by many ingenious women novelists, notably Elizabeth Sanxay Holding and Margaret Millar. The domestic thriller was a mainstay of popular fiction, radio, and the theatre of the period, so naturally it made its way into cinema.

Literary thrillers play ingenious games with the conventions of the post-Jamesian novel. We get geometrically arrayed viewpoints (Vera Caspary’s Laura, Chris Massie’s The Green Circle) and fluid time shifts (John Franklin Bardin’s Devil Take the Blue-Tail Fly). There are jolting switches of first-person narration (Kenneth Fearing’s The Big Clock), sometimes accessing dead characters (Fearing’s Dagger of the Mind). There are swirling plunges into what might be purely imaginary realms (Joel Townsley Rogers’ The Red Right Hand).

Ben Hecht remarked that mystery novels “are ingenious because they have to be.” Formal play, even trickery, is central to the genre, and misleading the reader is as important in a thriller as in a more orthodox detective story. No wonder that the genre suited filmmakers’ new eagerness to experiment with storytelling strategies.

Vision, danger, and the unreliable eyewitness

What does a thriller need in order to be thrilling? For one thing, central characters must be in mortal jeopardy. The protagonist is likely to be a target of impending violence. One variant is to build a plot around an attack on one victim, but to continue by centering on an investigator or witness to the first crime who becomes the new target. In Ministry of Fear, our hero brushes up against an espionage ring. While he pursues clues, the spies try to eliminate him.

Accordingly, the cinematic narration intensifies the situation of the character in peril. A tight restriction of knowledge to one character, as in Suspicion, builds curiosity and suspense as we wait for the unseen forces’ next move. Alternatively, a “moving-spotlight” narration can build the same qualities. In Notorious, we’re aware before Alicia is that Sebastian and his mother are poisoning her. Even “neutral” passages can mask story information through judiciously skipping over key events, as happens in the opening of Mildred Pierce.

Using point-of-view techniques to present the threats to the protagonist brought forth a distinctive 1940s cycle of eyewitness plots. Here the initial crime is seen, more or less, by a third party, and this act is displayed through optical POV devices. There typically follows a drama of doubt, as the eyewitness tries to convince people in authority that the crime has been committed. Part of the doubt arises from an interesting convention: the eyewitness is usually characterized as unreliable in some way. Sooner or later the perpetrator of the crime learns of the eyewitness and targets him or her for elimination. The cat-and-mouse game that ensues is usually resolved by the rescue of the witness.

The earliest 1940s plot of this type I’ve found isn’t a film, but rather Cornell Woolrich’s story “It Had to Be Murder,” published in Dime Detective in 1942. (It later became Hitchcock’s Rear Window. But see the codicil for earlier Woolrich examples.) The earliest film example from the period may be Universal’s Lady on a Train (1945), from an unpublished story by Leslie Charteris.

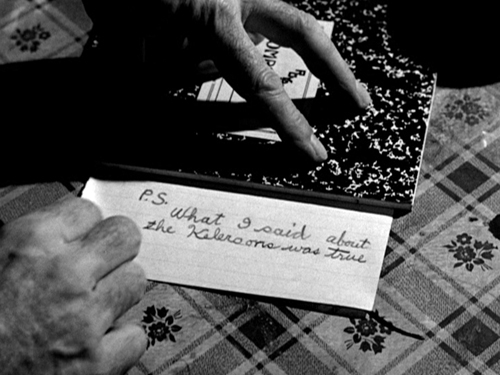

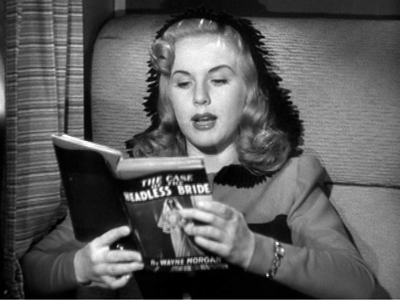

The opening signals that this will be a murder-she-said comedy. Nicki Collins is traveling from San Francisco to New York and reading aloud, in a state of tension, The Case of the Headless Bride (a dig at the Perry Mason series?). As the train pauses in its approach to Grand Central she comes to a climactic passage: “Somehow she forced her eyes to turn to the window. What horror she expected to see…” Nicki looks up from her book to see a quarrel in an apartment. One man lowers the curtain and bludgeons the other, and as Nicki reacts in surprise, the train moves on.

The over-the-shoulder framings don’t exactly mimic Nicki’s optical viewpoint, but they do attach us to her act of looking. Reverse-angle cuts show us her reactions. Her recital of the novel’s prose establishes her suggestibility and an overactive imagination. These qualities fulfill, in a screwball-comedy register, the convention of the witness’s potential unreliability. We know her perception is accurate, but her scatterbrained chatter justifies the skepticism of everybody she approaches. As the plot unrolls, her efforts to solve the mystery make her the killer’s new target.

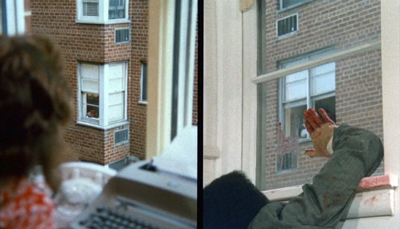

More serious in tone was Lucille Fletcher’s radio drama, “The Thing in the Window” from 1946. In the same year, Cornell Woolrich rang a new change on the “Rear Window” theme with the short story “The Boy Who Cried Wolf,” and Twentieth Century–Fox released Shock. In this thriller an anxious wife waits in a hotel room for her husband, who has been away at war for years. Elaine Jordan’s instability is indicated by a dream in which she stumbles down a long corridor toward an enormous door that she struggles to open.

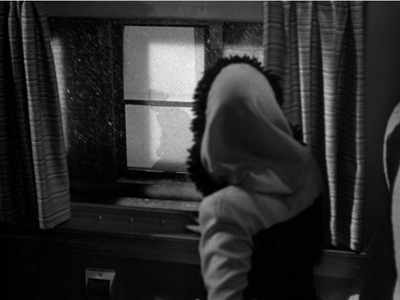

Awakening, Elaine nervously goes to the window in time to see a quarrel in an adjacent room. She watches as a man kills his wife.

Now she’s pushed over the edge. As bad luck would have it, the killer is a psychiatrist. When he learns that Elaine saw him, he takes charge of her case. He spirits her away to his private sanitarium, where he’ll keep her imprisoned with the help of his nurse-paramour.

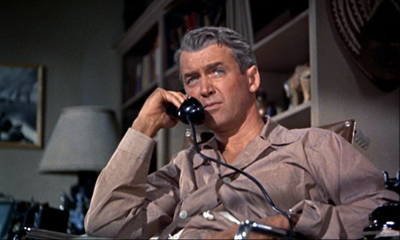

I was surprised to learn of this eyewitness-thriller cycle because the prototype of this plot was for me, and maybe you too, was a later film, Rear Window (1954). Again, the protagonist believes he’s seen a crime, though here it’s the circumstances around it rather than the act itself. Accordingly a great deal of the plot is taken up with the drama of doubt, as the chairbound Jeff investigates as best he can. He spies on his neighbor and recruits the help of his girlfriend Lisa and his police detective pal.

Hitchcock, coming from the spatial-confinement dramas Rope and Dial M for Murder, followed the Woolrich story in making his protagonist unable to leave his apartment. Following Woolrich’s astonishingly abstract descriptions of the protagonist’s views, Hitchcock made optical POV the basis of Jeff”s inquiry. By turning Woolrich’s protagonist into a photojournalist, he enhanced the premise through use of Jeff’s telephoto lenses.

Woolrich and Hitchcock’s reliance on spatial confinement worked to the advantage of the unreliable-witness convention. How much could you really see from that window? Jeff can’t check on the background information his cop friend reports. Besides, Jeff is bored and susceptible to conclusion-jumping. “Right now I’d welcome trouble.”

Hitchcock, who kept an eye on his competitors, doubtless was aware of The Window (1949), an earlier entry in the cycle. Derived from Woolrich’s “Boy Who Cried Wolf,” this RKO film has some intriguing things to teach us about the mechanics of thrillers and about the 1940s look and feel.

Spoilers follow.

At the window, and outside it

On a hot summer night, the boy Tommy Woodry is sleeping on a tenement fire escape one floor above his family’s apartment. He awakes to see Mr. and Mrs. Kellerson murder a sailor they have robbbed. Next morning Tommy tries to report the crime to his parents and then the police, but no one will believe him because he’s long been telling fantastic tales. A family emergency leaves him alone in the apartment, and the Kellersons lure him out. After nearly being killed by them, he flees to a tumbledown building nearby. There he evades Mr. Kellerson, who falls to his death. With Tommy’s parents and the police now believing him, he’s rescued from his perch on a precarious rafter.

Woolrich’s original story confines us strictly to Tommy’s range of knowledge, but in the interest of suspense screenwriter Mel Dinelli uses moving-spotlight narration. When Tommy flees the fire escape, for instance, we follow the efforts of the Kellersons to rid themselves of the body. This becomes important to show how difficult it will be for Tommy to prove his story. There’s also a moment during their coverup when the camera lingers on Mrs. Kellerson, both in profile and from the back, as if she were hesitating about going along with the plan.

This shot prepares for the climax, when as her husband is about to shove Tommy off the fire escape, she blocks his gesture and allows Tommy to escape across the rooftops.

Likewise, Woolrich’s story simply reports that the young hero waited at the police station for the result of Detective Ross’s visit to the Kellersons. The film’s narration attaches us to Ross and creates a scene of considerable suspense when we wonder if Ross will discover any clues to the murder. And whereas in the story Tommy must worry about how Kellerson will get to him, through crosscutting between Kellerson in the kitchen and Tommy locked in his room we know everything that’s happening. This permits a wry passage of suspense in which Kellerson toys with Tommy by letting him think he’s retrieving the door’s key.

In contrast to the moving-spotlight approach, though, crucial passages are rendered with a limited range of knowledge. Optically subjective shots come to the fore here, as when Tommy witnesses the murder.

It seems likely that Hitchcock’s early American films heightened filmmakers’ awareness of subjective optical techniques, and here director Ted Tetzlaff puts them to good use. The script I’ve seen for The Window doesn’t indicate such pure POV shots, instead opting for something like what we get in Lady on a Train. “CAMERA is ON the pillow back of Tommy, so that we see his head in the f.g and the window in the b.g.” There is a shot matching these directions, but it’s surrounded by the straight POV imagery framed by Tommy’s frightened stare.

The decision by Tetzlaff and his colleagues to rely on optical POV is confirmed when, during Ross’s visit, he spots a stain on the floor.

Is this a bloodstain that will put Ross on the scent? Crucially, we haven’t seen the lethal scissors leave a trace. Kellerson explains the stain as coming from a leak in the ceiling. Obediently Ross looks up and, to prolong the suspense, so does Mrs. Kellerson, apparently as apprehensive as we are. That extra shot of her nicely delays the reveal: there is a leak above them.

In tune with the tendency to thicken the narrative texture, this POV dynamic reappears at other moments. Tommy sees his parents leave, and the reverse angle reveals that the Kellersons see them too, and so they know that Tommy is now unguarded.

At the climax in the abandoned tenement, Tommy spots his father and the policeman outside. He shouts to get their attention, but they can’t hear.

But Kellerman does hear Tommy and uses the sound to stalk him.

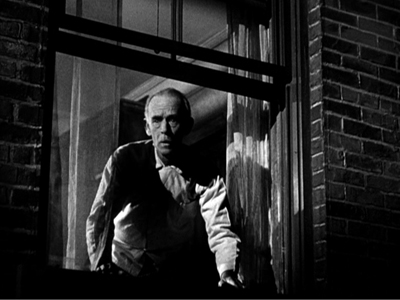

1940s stylistic thickening includes the use of audiovisual motifs that impose a distinctive look on the film. So a movie called The Window begins, after a couple of establishing shots of Manhattan street life, with a shot of a window.

This one has no special importance in the plot, but it announces the image that will recur throughout the movie. By shooting ordinary scenes through window frames, Tetzlaff reminds us that the locals live partly through those windows and the fire escapes outside.

Naturally enough, Kellerson plans to kill Tommy by having him tumble from the fire escape outside the window.

The film’s key image reappears at the end, when after Kellerson’s fall a new crop of witnesses take to their windows.

Another motif is the vertical link between the two apartments, given in looming shots of the staircase (a common piece of iconography in 1940s cinema) and in cutting that links Tommy’s bedroom to the Kellersons above him. He listens to their footsteps through his ceiling.

The next layer up, the rooftop, serves as a route from the families’ building to the abandoned one, and eventually the chase will play out there.

Vertical space more generally is important at the very start of the film. During Tommy’s mock ambush of his playmates, we look down over his shoulder. At the very end, Kellerson has trapped Tommy on the broken rafter.

The rooftop and rafter become part of another pattern, the circular one that rules the plot. Woolrich’s original story doesn’t feature the opening we have, showing Tommy in the abandoned tenement pretending to snipe at the other boys. Nor does the shooting script I’ve seen. Starting the film there establishes the locale of the climactic chase, while creating parallel scenes of Tommy hiding. We even get to see the broken rafter early on, when Tommy is prowling around his playmates.

The result is a pleasing, somewhat shocking symmetry of action: Tommy pretends to kill somebody at the start, and he succeeds in killing someone at the end.

The film offers a cluster of images that are recycled with variations, amplifying the basic story action through patterns of space and visual design.

The thickening of texture isn’t only pictorial. The drama of doubt involves a questioning of parental wisdom. Tommy’s mother actually endangers her boy by asking him to apologize to Mrs. Kellerson. More central is a testing of the father’s faith in his son. Tommy’s dilemma is to tell the truth even though he’ll be disbelieved by all the figures of social authority. The father’s increasingly desperate efforts to change Tommy’s story are revealed in Arthur Kennedy’s delicate portrayal of exasperation–at first gentle, then severe and nearly abusive.

Ed Woodry fails in his duty. The adults aren’t capable of protecting the child. A conventional plot would’ve had Ed redeem himself by rescuing his son, but the film we have leaves the killing to Tommy. It’s a grim condemnation of the people supposed to protect him.

Another convention, it seems, of the eyewitness film involves punishing the peeper. In Lady on a Train, Nicki has to brave a spooky house and risk death. Elaine of Shock suffers in the mental institution, and in Rear Window Jeff eventually falls from the very window that was his interface with the courtyard. Tommy, who acknowledges his inclination to tell whoppers, is subjected to a final burst of peril. After Kellerson has plunged to his death, Tommy is left in mid-air and he must jump to the firemen’s waiting net. In the epilogue, he announces that he’s learned his lesson, not least because of several brushes with death.

Revising the rules

The 1940s eyewitness cycle laid out some options for future thrillers. Rear Window, as we’ve seen, crystallizes the plot premise in rather pure form, and interestingly that was copied almost immediately in the Hong Kong film Rear Window (Hou chuang, 1955). Some passages are straight mimicry, albeit on a much smaller budget.

Thereafter, the eyewitness premise resurfaced, notably in Sisters (1973, with split screen) and with another child protagonist in The Client (1994).

In recent decades filmmakers have revised the premise in ways typical of post-Pulp-Fiction Hollywood. Vantage Point (2008) multiplies the eyewitnesses and uses replays to conceal and eventually reveal information. The Girl on the Train (2016), streamlining the multiple-viewpoint structure of the novel, alternates plotlines centered on three women. The novel and the film recast the eyewitness schema by making the eyewitness unable to recall exactly what she saw, thanks to an alcoholic blackout. (It’s a cousin to our old 1940s friend amnesia). This uncertainty raises the possibility that the eyewitness is actually the killer.