Archive for the 'Narrative strategies' Category

Edgy color, trial testimony, and the world in unison: More movies at Ritrovato

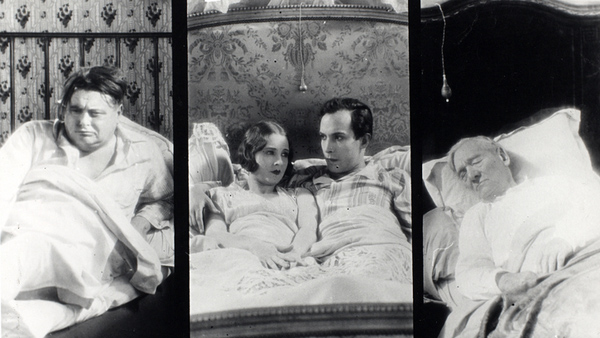

The Woman under Oath (1919).

DB here:

Hard to keep up. Herewith, some highlights as Cinema Ritrovato, the Cannes of classic cinema, winds down.

Grease, still the word

Patricia Birch was a dancer with Martha Graham and Agnes De Mille. She went on to participate in West Side Story and to choreograph The Wild Party (1975) and both stage and film versions of A Little Night Music (1973, 1977). What brought her to Bologna was the restored version of Grease (1978). She choreographed that on both stage and screen, and she talked about it at a stimulating panel with Ehsan Khoshbakht and her son Peter Becker, of Criterion Films.

I had thought that Grease followed the vogue for boomer high-school nostalgia triggered by American Graffiti (1973), but it was actually ahead of that. The original Chicago version, reportedly raunchier than the New York version, premiered in 1971. It opened on Broadway in 1972 and ran until 1980. The film modified the stage show and added some songs.

Ms. Birch was a font of information about how she conceived the numbers. She says she thinks of dance as “timed behavior,” not set steps but patterns of motion. This idea allows her to choreograph actors who didn’t have dance training but who could “move well.” Peter ran a clip showing a passage of cascading hallway mischief that was as rhythmic as a dance number. This was one of several group-action scenes that Ms. Birch coordinated.

The Grease ensemble was huge, and Ms Birch organized it in a quasi-military way. There was a core of twenty proficient dancers, ten male-female couples. They supervised and coached the less skilled performers. For “We Go Together,” set in a carnival, each couple found business and steps for thirty other dancers.

“We Go Together” was the sort of big showstopper she called “Paramount numbers.” There were also the smaller-scaled “semi-Paramount numbers” and the intimate, character-driven “Internal numbers.” Ms Birch pointed out how the Paramounts built their power on unison steps and, eventually, massive kicklines. “People like to see the world in unison. Gets ’em every time.”

I learned a lot from Patricia Birch’s spirited discussion. Watch for a version of the panel to show up online.

Cutting edges

Film curator Olaf Müller set a new Ritrovato record: the shortest retrospective to date. Three films running less than twenty minutes introduced us to the oeuvre of Franz Schömbs.

Schömbs was a painter who became, according to Olaf, “probably the only avant-garde filmmaker of 1950s West Germany.” He started in the thirties by mounting paintings in rows, inviting viewers to walk along and sense the changes among them. After the war Schömbs tried to revive the experimentation of the Weimar period, principally through abstract films rich in color and design.

The films on the program were dense. Opuscula (1946-1952) consists of patches of color that slide to and fro “on top” of one another thanks to panning and tilting movements. The superimpositions create some striking visual hallucinations, as when blocks of white refuse to change color while other forms around them do. Die Geburt des Lichts (“The Birth of Light,” 1957, above), my favorite, transposes that constant movement to the patches of color themselves. These patches, as crisp as paper cutouts, have thrusting edges that keep slicing into the mates around them. Apparently Schömbs achieved the effect by applying paint to layers of glass and adjusting them frame by frame. Den Eisamen Allen (“To All the Lonely Ones,” 1962) uses what seemed to me traveling mattes, again enlivened by rich color.

Once more, Bologna proves a showcase for films that would otherwise go missing from film history.

Trial, with error

The courtroom drama was a mainstay of early twentieth-century theatre, but in 1915, playwright Elmer Rice gave it a twist. On Trial presented a murder trial by dramatizing the witnesses’ testimony in flashbacks. Rice offered another innovation as well: his flashbacks are non-chronological, starting with the most recent incident and reserving the climax for the earliest piece of action. Using the courtroom drama to play with time and viewpoint became a staple of American theatre and cinema.

Popular culture is a teeming mass of copies and near-copies–the switcheroo principle–so it didn’t take long for other storytellers to vary and complicate the trial format. One of the neatest examples was on display in Bologna. In the John Stahl silent drama The Woman under Oath (1919), flashbacks replay key actions according to what different witnesses know. We get no fewer than five flashbacks, some presenting incidents leading up to the crime, others recounting the murder itself. The later ones fill gaps in the earlier ones and culminate in a full, accurate version of the killing.

Proving once more that 1910s cinema can be pretty intricate, the same pieces of action get redeployed in different witnesses’ testimony. Sometimes the camera setups are varied to differentiate the versions.

At other moments, nearly identical framings mislead us by concealing important information. The young man accused of the murder is shown near the victim in three pieces of testimony, with the first two instances being essentially identical but the last presentation providing different information. (To avoid a spoiler, I don’t show the portion of the third shot that yields that information.)

The Woman under Oath shows a sophisticated understanding of how framing can conceal information without our being aware of it. And in retrospect what seems a colossal coincidence during the first presentation of the killing turns out to be a perfectly motivated key to the solution.

Switcheroos on the trial-testimony format showed up in other Ritrovato films. By 1928, the idea of conflicting testimony enacted in “lying” flashbacks was conventional enough to be parodied in René Clair’s Les Deux timides (“Two Timid Souls”). Here the disparities are wildly comic, accentuated by split-screen and freeze frame. Albert Valentin’s La Vie de Plaisir (1944), made under the German occupation of France, is an elegant social comedy pitting a couple against one another in divorce court. The spiteful witnesses offer testimony damning the husband only to get refuted in replays that reveal extra information. Throughout world cinema, the flashback trial film seems to have been one way oblique narrative strategies were made understandable for a wide audience.

Thanks as ever to Guy Borlée for assistance, and to the Ritrovato programmers for supplying so many treats. Thanks also to Kelley Conway for discussion of the courtroom movies. We should also be grateful to the BFI for providing Bologna with the copy of The Woman under Oath.

One rough precedent for Rice’s play is Browning’s verse novel The Ring and the Book (1868-1869). The lingering awareness of Rice’s play is evident in Variety‘s review of The Woman under Oath, which the critic labeled “a sort of ‘On Trial’ affair” (20 June 1919, 52). In the same year there was an interesting parallel in the flashback testimony in Dreyer’s The President (1919).

You can find more about the switcheroo premise in my Reinventing Hollywood, which also discusses the trial format. For more on flashbacks see this entry. A series of entries on complex 1910s cinema start with this one.

P.S. 3 July 2018: Thanks to Peter Becker for a correction.

Les Deux timides (1928).

The classical Hollywood whatzis

Black Panther.

DB here:

In the academic world, there are conferences and conventions. Conventions tend to be humongous jamborees associated with professional groups like the Modern Language Association and the American Historical Association. They feature panels, workshops, plenary events, book displays, hundreds of papers, and meetings of subgroups–boards, caucuses, and the like. Also sexual liaisons, I’m told. If you want to feel like you belong to a corporation, go to a convention.

Conferences tend to be smaller and focused on single topics. Sometimes speakers are solicited through a call for papers, and sometimes the speakers are invited (the result might be called symposia). I think conferences are more exciting, liaisons aside. Some of the best experiences of my life have been get-togethers like “Imagination and the Adapted Mind: The Prehistory and Future of Poetry, Fiction, and Related Arts” (1999, University of California–Santa Barbara).

Last month, Kat Spring and Philippa Gates of Wilfred Laurier University added another to my list of favorite conferences. “Classical Hollywood Studies in the 21st Century,” which I announced in the run-up to it, was a wonderful gathering of scholars working on American studio cinema from a variety of angles.

Waterloo mon amour

Scott Higgins talks Minnelli.

We heard about production, distribution, marketing and publicity practices, censorship, and fandoms. Mark Glancy analyzed the trade-paper and fan-mag positioning of the Cary Grant/ Randolph Scott household (♥ + ♥?), while Will Scheibel studied discourse around the sad fate of Gene Tierney. Through both close analysis and probing of primary documents, several papers treated racial and gender representation: Charlene Regester on Double Indemnity, Philippa on portrayals of Chinatown, Barry Grant on race in science fiction, Ryan Jay Friedman on African American musical numbers. There was consideration of style and narrative as well, as in Chris Cagle’s case for distinguishing baroque and mannered styles within “1940s Hollywood formalism” and in Stefan Brandt’s tracing of thematic affinities between Finding Dory and The Grapes of Wrath.

I was glad to see the industry and its affiliated institutions get so much attention. Paul Monticone proposed a cultural approach to the MPPDA, while Tom Schatz traced industry developments in the New Hollywood and after. At the level of reception, Peter Decherney traced how digital tools can measure fan engagement with Star Wars. And John Belton, pioneer of detailed technological history, shared a Bazinian take on digital cinema.

Little-appreciated creative workers got to share the spotlight, in Helen Hanson’s paper on Lela Simone (music supervisor for the Freed unit) and Cristina Lane’s study of the career of Joan Harrison, Hitchcock’s “work wife.” Kay Kalinak revealed how composers swiped from themselves, as Tiomkin did in his score for The Big Sky. And there were lots of surprises, as with Shelley Stamp’s revelation of how film noir was sold to female audiences, Adrienne McLean’s account of stars’ running, or at least signing, advice columns, and Kirsten Moana Thompson’s dissection of the unique paint mixtures used in Disney animation.

It wasn’t musty, either. Things were light and friendly, with serious topics treated without pomp. Blair Davis’s obsessive search for science-fiction elements in serials and B films of the 1930s and 1940s, Steven Cohan’s zesty admiration for the “backstudio” picture, Kyle Edwards taking Torchy Blaine (and her budgets) straight, Dan Goldmark’s affectionate dissection of Pixar’s use of memory, and Liz Clarke’s enthusiasm for heroines of World War I films–all showed that classical filmmaking can be studied with both admiration and rigor. Not to mention Richard Maltby’s patented wry wit. (“David, you know I’ve always been a vulgar Marxist.”)

I have to signal my pride in witnessing how many of the participants were affiliated with our program. Tino Balio on MGM, Scott Higgins on Minnelli’s staging, Lisa Dombrowski on late Altman, Charlie Keil (with Denise McKenna) on Hollywood as a “social cluster,” Eric Hoyt (doyen of Lantern) on trade papers, Mary Huelsbeck on archival resources, Vince Bohlinger on US censorship of Soviet films, Maria Belodubrovskaya on Stalinist movie plots, Brad Schauer on Universal’s acting school, Kat Spring on how the trade papers conceived the musical, Patrick Keating on using the video-essay form to analyze lighting–all showed how you can pack a lot of ideas and information into 18 minutes. I was elated to see the learning and energy these several generations of Wisconsinites displayed.

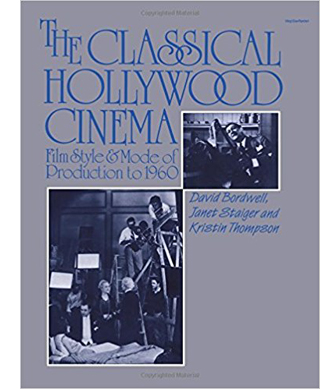

The authors of The Classical Hollywood Cinema got in their licks. Janet Staiger talked about current screenwriting practices, highlighting the role of gatekeepers (agents, script analysts) and the need for vivid writing that can indulge in flourishes–“movies on the page.” Kristin drew on her Frodo Franchise project to show the problems, but also the advantages, of researching an event while it’s happening.

As for me, I got to give the keynote lecture. It was an intimidating situation, but it did allow me to make the case for analyzing films in relation to norms. Since the conference, I’ve thought more about the idea of Hollywood “classicism” and how we might analyze changes in it.

Not exactly classical, but sweet

Janet Staiger and Kristin Thompson, on a research trip to Washington DC 1979.

Now, some thirty-three years since we wrote The Classical Hollywood Cinema, we all know a lot more. There’s scarcely a paragraph of my chapters I wouldn’t change, and much of the research I and others have done since would correct, nuance, and deepen their claims. (I think Janet’s and Kristin’s contributions survive better than mine.)

What did we three do? I’d say we sought to provide a comprehensive description and explanation of narrative and cinematic techniques in the studio years. We traced ties between craft conditions and production decisions on the one hand and the resulting film on the other. We argued that studio division of labor allowed not only reliable production but a standard menu of artistic options. Going beyond the individual filmmaker, we traced how adjacent institutions–not just the studio but professional associations, supply firms, trade papers, and the like–worked to define and maintain the style. We also suggested reading the professional literature rhetorically, seeing industry discourse as a way for individuals and organizations to set agendas and crystallize preferred solutions to problems. We tried to show how technological innovations like color and widescreen cinema took particular turns because of this matrix of activities. And we began the project of treating Hollywood filmmaking as a flexible but bounded set of norms of style and story.

What did we three do? I’d say we sought to provide a comprehensive description and explanation of narrative and cinematic techniques in the studio years. We traced ties between craft conditions and production decisions on the one hand and the resulting film on the other. We argued that studio division of labor allowed not only reliable production but a standard menu of artistic options. Going beyond the individual filmmaker, we traced how adjacent institutions–not just the studio but professional associations, supply firms, trade papers, and the like–worked to define and maintain the style. We also suggested reading the professional literature rhetorically, seeing industry discourse as a way for individuals and organizations to set agendas and crystallize preferred solutions to problems. We tried to show how technological innovations like color and widescreen cinema took particular turns because of this matrix of activities. And we began the project of treating Hollywood filmmaking as a flexible but bounded set of norms of style and story.

The book received both praise and criticism. With the passage of time some issues have become clearer, and some critiques have, as far as I can tell, lost some force. For instance:

The term. Why call it “classical”? Humanists love to debate terminology. But we pointed out in the book that we inherited the term from French commentators, as far back as the 1920s, and from more recent academic circles. Nothing hangs on the name, actually. We could call it “standard” style or “mainstream” style or X style, and the descriptive claims we make about it will hold good. As I indicate in the book, the “classical” label suggests an effort toward coherent, unified storytelling–at least in comparison with the more episodic narratives we find in other traditions. (In Planet Hong Kong I reflect on more episodic approaches.)

The focus on production. Why not talk about distribution, exhibition, or reception? (A) It would require a much bigger book. (B) Production and its affiliated institutions are the most pertinent and proximate causal factors in shaping the films as we have them. (C) It’s not clear that conditions further along the chain have many consequences for the way the movies behave. (D) You can’t talk about everything. (E) All of the above.

The term, again. By calling Hollywood storytelling and style “classical,” don’t you ignore its ties to modern culture? This view, advanced most fully by Miriam Hansen, suggests that the causal factors we trace aren’t broad enough; we don’t consider the rise of urban culture and its associated patterns of behavior and experience. The modern city purportedly alters people’s perception and rhythms of life, and these shape the way films are made. Hollywood’s aesthetic is better conceived as “vernacular modernism.” I’ve responded to this line of argument in On the History of Film Style, where I argue that the position has an equivocal conception of urban experience and how perception works. Moreover, these critics haven’t shown how the cultural forces they invoke have shaped the narrative strategies and fine-grained stylistic features we analyze. The urban experience would have to have a sort of feedback effect on the filmmakers (given the proximity of production, as above). What’s the causal story to be told here? There’s also a problem of delayed timing: the modern city, choked with traffic and distracting displays, antedates the 1910s, when the Hollywood style crystallizes. On the whole, the modernity position seems to me to rely on analogies, not causation.

A rage for disorder. How unified are these films, really? Critics sometimes point to musicals, action movies, noirs, comedies, and other films that seem narratively disjointed. We argued that classical construction was a goal, not always achieved, but even genres that seemed to favor loose plotting put their films together fairly tightly. In addition, principles of both surface structure (dialogue hooks, continuity cutting) and plot structure (goal orientation, deadlines, appointments, etc.) bind the action in most feature-length pictures. In more recent years, analyses by Kristin in Storytelling in the New Hollywood and by me in The Way Hollywood Tells It and Reinventing Hollywood, along with some entries on this site, have, I think, convinced people just how carefully sculpted a classical film can be. Fights, chases, and escapes aren’t mere spectacle; they advance the story by creating new obstacles or revealing betrayals or killing off the hero’s best friend. I have, though, come to accept coincidence as being more important than screenwriting gurus have claimed. Yet even here, coincidence is absorbed into a pattern of cause-and-effect and motivation that isn’t willy-nilly. In short: Where you find planting and foreshadowing, you’ll find “classical” unity.

The neglect of auteurs. Why treat the output of hacks and mediocrities as on the same level as the work of the great filmmakers? Andrew Sarris promoted the idea of writing American film history as the accretion of the “personal visions” of directors. And historians of other arts routinely conceived of history as a succession of exemplary works produced by exceptional creators. But we were asking different questions. We sought to understand a tradition as a whole, and to explain its emergence and longevity. That’s an effort of value in its own right. Moreover, an auteurist could benefit from knowing relevant norms, because then one could pinpoint the distinctiveness of individual filmmakers. Throughout his work, Sarris occasionally signaled when a director made an uncommon choice of camera setup or cutting, and this gesture presupposes a norm in the background.

The schlock of the new. By stopping your survey in 1960, don’t you assume that a post-classical cinema came next–one less concerned with goal-directed plots and “invisible” style? We argued that the industrial conditions for the studios faltered around 1960, but the creative and labor practices (division of labor, hierarchy of control, etc.) continued into the present. We thought that classically constructed films dominated output afterward (Jaws, The Godfather, The Exorcist). Not that there aren’t changes. We suggested that many of the changes detectable in the more unusual “New Hollywood” films of the 197os are traceable to the influence of European art cinema; those principles of construction were blended with genres and stylistic patterns characteristic of the studio tradition. (Since then, other researchers have found this to be the case.) In addition, there are many post-1960 films which are “hyperclassical.” Back to the Future, Jerry Maguire, Die Hard, Hannah and Her Sisters, and others are “more classical than they have to be,” with intricate patterns of motifs and plotting–packed, we might say, with classical features. The same goes for many films we’ve discussed in our blog entries since 2006.

The monolith (no, not 2001). So the classical style never changes, is always in force, can’t go away? Ridiculously monolithic! Actually, we argued that classical filmmaking does change, but within boundaries. I invoked Leonard Meyer’s notion of “trended change,” in which

change takes place within a limiting set of preconditions, but the potential inherent in the established relationships may be realized in a number of different ways and the order of the realization may be variable. Change is successive and gradual, but not necessarily sequential; and its rate and extent are variable, depending more upon external circumstances than upon internal preconditions.

This seems to me to capture change in the studio tradition. Hollywood films can have 400 or 2000 shots, they can be told chronologically or not, they can have single protagonists or multiple protagonists, and there will be a lot of variety at any moment. But they will still tend to obey canons of classical staging, camerawork, cutting, sound work, and dramaturgy. And those changes are, as Meyer suggests, not generated from within the style, as a necessary unfolding like the growth of an organism. The variations are created by external circumstances such as budget constraints, production trends, influential models, new tools, fashion, competition among filmmakers, and the like. I’d make the analogy to the well-made play, which has survived as a model of plotting for nearly two centuries, but has allowed for a huge variety of manifestations, from Ibsen to Doubt and beyond. Perhaps perspective painting and Western tonal music, both robust traditions, would also exhibit trended change within history.

In the book, I tried to analyze levels of change by a three-tier model that still seems valid, though perhaps too abstract. Coming back from Waterloo, I began to see a way to specify a little more the kinds of change we can track, at least in terms of narrative construction. Maybe this effort will also help us understand why we think the “classical” system changes more than it does.

Black Panther in three dimensions

Narrative theorists often distinguish between “story” and “discourse.” There’s the causal-chronological string of events, and there’s the way they’re presented in the text we have. There are other terms for the distinction (story/plot, fabula/syuzhet), and they aren’t completely congruent. In an essay reprinted here I propose that we can better think of narratives as having three dimensions: the story world, the structure of the plot, and the narration.

Start with narration. Why? Because it’s the flow of information we encounter moment by moment, given to us through all the resources of the medium. Black Panther begins with a visual representation of how vibranium created the nation of Wakanda, while we hear on the soundtrack a father recounting the tale to his son. (Here the film’s narration is given as both pictorial and voice-over.)

In an earlier version of this entry, I said that it was T’Chaka speaking to T’Challa. But Fiona Pleasance wrote to point out that the voice is actually that of T’Chaka’s brother N’Jobu telling his son N’Jadaka, who will grow up to be Killmonger. They’re living in exile, which motivates the need to rehearse the nation’s origins.

The narration isn’t only giving exposition about Wakanda’s history. It’s establishing a hierarchy of knowledge, in which the father is presented as knowing more than his son. This is important for a later revelation of what aspects of the past are suppressed. And flashbacks and other narrational choices will further channel the flow of information. Soon after the prologue, we jump back to 1992, when T’Chaka learned of N’Jobu’s affiliation with arms dealer Klaue.

With or without voice-over, the regulated flow of story information will continue throughout the movie. Out of this narration we build a story world. We’re cued to construct characters, to register their roles and attitudes and feelings, to sense their hopes and fears. We also construct the story’s physical world, with its geography and furnishings and rules. Very quickly, for instance, we understand that Wakanda is a land of utopian technology but ruled by ancient tribal lore and rites. Through redundant information we learn of T’Challa’s family and friends, past conflicts among characters, and the threats to Wakanda.

Okay, so we have narration that coaxes us into co-creating a story world. What’s left for my third dimension, plot structure? Kristin convinced me that it’s another level of construction, one that organizes the story world into a comprehensible pattern that can in turn be transmitted via narration. She argues that classical films often have four large-scale parts (not three acts), each typically running about half an hour. Those parts focus the action in the story world around the characters’ goals.

In the Setup, running about half an hour, we meet the main characters and learn their goals. In the Complicating Action, another half hour more or less, the goals get redefined as a result of new obstacles. Then comes the Development, which is largely a holding pattern. Here we get backstory, character portrayal, fantasies and flashbacks, the upgrading of secondary characters, and elaboration of motifs. At the end of the Development, a crisis develops; at this point we know nearly everything we need to know and can concentrate on the outcome. Now comes the Climax, usually with a deadline pressing on the action. At the end, with the action largely resolved, there’s an epilogue (or “tag”) that celebrates the final state of things.

This anatomy of plot structure echoes the classic screenplay manuals up to a point. The Setup corresponds to Act I, the Climax to Act III. The Complicating Action and the Development in effect split the second act. But Kristin’s layout is more precise, I think, because she shows that goals and obstacles change between the first and second part. She also points up the more or less arbitrary delays and detours that prolong the action in her third part, the Development. This “desert of the Second Act,” as screenwriters call it, can now be seen as doing its own distinctive narrative work, not least prolonging suspense.

This structure didn’t have to have such sharply defined segments. Why can’t the setup be an hour, dawdling over introducing the protagonist’s goals? Why not cut out the Development, if it’s mostly delay? The Hollywood tradition has created this distinctive, tight form as one solution to the problem of organizing an appealing narrative at feature length.

Take Black Panther again. The Setup charges T’Challa, newly made king, with responding to Klaue’s theft of a precious Wakandian tool made of vibranium. (Screenplay gurus sometimes call this the “inciting incident.”) At the 35-minute mark T’Challa, Okole, and Nakia set out on a mission to retrieve the artifact. At sixty-one minutes, the midpoint, the goals need revising. Klaue is dead, the Wakandans’ ally Ross is severely wounded, and the real antagonist is revealed: the fierce fighter Erik, aka Killmonger.

The Development provides important backstory involving T’Challa’s uncle’s child N’Jadaka (more flashbacks, including replays of the 1992 scene presented in the Setup–revealing the child Erik as on the scene). T’Challa’s allies flee from Killmonger, who prepares to use the precious vibranium to make weapons for world insurrection. T’Challa, near death, has been rescued by his rival the Jabari chieftain Baku. All pretty typical Development, moving the hero toward his “darkest moment” and facing him with a deadline.

The Climax, which tends to be the shortest section in most films, starts at about 99:00. It’s a gigantic battle scene, involving air combat, ground fighting, and the confrontation of T’Challa and Killmonger–all crosscut for maximum suspense. After the resolution, we get a tag showing a montage of life returning to normal, T’Challa kissing Nakia, and another visit to the 1992 world when T’Challa comes calling in a space ship.

The film has the characteristic double plotline, a romance line of action (will T’Challa and Nakia reunite?) and one centering on a project (keeping vibranium out of the wrong hands). Major developments are carefully foreshadowed. The paternal voice-over establishes the Jabari tribe’s isolation, and Baku’s crucial role is planted when he challenges T’Challa to mortal combat. Later Baku will save the young king. Kristin also points out the importance of motifs in tightening classical structure. Here we get recurring lines (“”I never freeze”/ “Did he freeze?”), the lip that identifies a Wakandan, the importance of border patrols, and the ring that reveals Erik as kin to T’Challa. Parallel scenes–two waterfall fights, two burial ceremonies with attendant ephiphanies, two street strolls of T’Challa and Nakia–measure significant dramatic differences.

Despite being an installment in a much bigger saga, Black Panther is a solid example of classical construction. (I don’t have to explain how it obeys the rules of continuity staging and editing, do I?) A hundred years after the Hollywood storytelling system settled in, it’s still shaping the movies coming out each Friday.

Main attraction: Worldmaking

Why have so many smart people thought that studio storytelling changed drastically after 1960, or 1945, or 1977? I think it was because trended change was happening along two of these three dimensions.

Narrationally, there were trends toward innovation. I argue in Reinventing Hollywood that 1940s filmmakers consolidated narrative devices that had appeared piecemeal in the silent and early sound eras. Those strategies–flashbacks, voice-overs, subjective sequences, self-conscious artifice, mystery plotting–gained a new prominence and were explored with unprecedented ingenuity. The 1990s was another period of experimentation, reworking all those techniques and more, such as network narratives and forking-path plotting. These suggested to sensitive critics that something new was up. For me, they show the versatility of the classical system, its ability to explore what Meyer calls its “preconditions.”

One broad narrational change I’d now emphasize is the tendency to be more elliptical. The opening of Black Panther doesn’t show us N’Jobu speaking to his son. This misled me, and perhaps some others. Executive producer Nate Moore explained:

“We landed on N’Jobu telling the story to his son, which wasn’t our first choice, but ultimately felt really satisfying,” said Moore. “Hopefully on repeat viewings you go, ‘Oh that’s who I was listening to, OK that’s cool.'”

A film in earlier periods would have shown us the speaker and listener, but we’ve so “overlearned” the convention of a tale told by an elder to a child that we need only one set of cues, on the soundtrack. Still, the uncertainty about the speakers–we haven’t met any of the characters yet–offers less redundancy than is traditional. I’m reminded of the old man’s voice-over that opens The Road Warrior; only at the very end do we learn his identity.

The elliptical prologue exemplifies what’s perhaps the most common change in narrational strategies across history. A lot of new practices, such as the substitution of straight cuts for dissolves and fades between scenes, involve this sort of reduction in redundancy. It’s possible because Hollywood films are traditionally quite repetitious in doling out story information, as is indicated by the infamous Rule of Three. (Once for the smart people, once for the average people, and once for Slow Joe in the Back Row.) Still, as is typical of trended change, not every film must adopt an elliptical technique. Black Panther‘s beginning could easily have shown us father and son talking, without any sense of being old-fashioned.

The suppression of the prologue’s speakers not only puts the emphasis on the tale but adds a bonus for repeat viewings. This is the sort of “thickening” of classical style I analyzed in The Way Hollywood Tells It. I proposed there that making the films available on video formats enabled fans to hunt for fine points and Easter Eggs. Nate Moore’s comments seem to presuppose this sort of fan-driven recidivism. Such sneaky bits for insiders weren’t unknown in earlier periods (I talk about some here and here and here), but the ability to scan and pause DVDs made such games more common.

The bigger changes across Hollywood history, and the ones that constantly impress observers, spring from the movies’ story worlds. The popularity of fantasy and science fiction is, from this standpoint, an extreme instance of the most common way that the tradition refreshes itself. Most of the novelty of Hollywood, I think now, involves worldmaking, big or small. Find new milieus, new characters, new situations. Create conflicted protagonists–fallible, vulnerable, torn by indecision. Turn the heterosexual romance into a gay one. Build your plot around an ensemble (Grand Hotel, Nashville). Take the heist formula and feminize it (Ocean’s 8). And on and on.

Repopulating the story world has another advantage: it yields a new range of thematic implications and thus invites interpretation. Get Out, a film we discussed a bit at the conference, calls on both specific horror-film conventions (the mad scientist, the innocent victim lured to a corrupt community) and broader classical conventions (a double plotline, a restricted viewpoint for suspense and surprise, 1940s dream states, a last-minute rescue). What made the film intriguing and controversial was turning the white bourgeoisie into modern plantation seigneurs re-enslaving African Americans. This refashioning introduces thematic material that can provoke public discussion.

You can call this endless remaking of story worlds unimaginative. But the variorum impulse, this combinatorial cascade of materials and techniques, seems typical of popular art. Art makers take familiar schemas and rework them in novel ways. I’m not exactly saying that everything is a remix, but everything does start from a point of departure in some tradition. Even Cubist painters needed the work of Cézanne and the genre of the still life in order to contrive their innovations.

Moreover, we’re far more sensitive to the story world than the other dimensions of narrative. We’re interested in other persons (or person-like agents, such as Dory), so naturally we’re quick to register the new people, places, and things that a movie prompts us to co-create. Narration and plot structure, although they have immense impact on us, are far less visible. So it’s not surprising that the most imaginatively gripping novelty in mainstream narrative film involves the creation of fresh agents and arenas for story action.

Compared with the story worlds, Kristin’s four-part-plus-epilogue template is far less noticeable. Yet it is a stable and enduring dimension of Hollywood storytelling. Given characters with goals, the narrative structure squeezes those into a sturdy and quietly familiar mold of rising action, delayed action, and culminating action. The strictness of the form, with its well-timed turning points and echoing motifs, seems as reliable as the conventions of narration. It’s a stubborn, persistent feature that testifies to the continuing power of the classical model of narrative.

I can’t claim to have fathomed all the principles of classical storytelling and style. Still, I think we’ve made progress in understanding the engineering, so to speak, of one major cinematic tradition. And it doesn’t exist in splendid isolation. Hollywood’s continuity editing system provided a lingua franca of popular cinema worldwide, and Hollywood narrative structure and narration has been borrowed, wholesale or piecemeal, in other national traditions. Filmmakers, having found a bundle of principles that are understandable and pleasurable to wide audiences, have clung to them for a very long time. Call it classicism or whatever, it’s real and strong and it works pretty well and I bet it’s not going away any time soon.

Thanks to Kat and Philippa for inviting us to their splendid conference. I believe that a book will collect the papers given there; when that happens, we’ll alert you.

More thoughts on our book can be found at “The Classical Hollywood Cinema twenty-five years along.”

The ideas in this entry stem from the books mentioned above, from Poetics of Cinema, and from several other items on our site. If you’re curious, you can look at Kristin’s explanation of the four-part structure and two pieces where I develop her template in relation to the action movie and in relation to traditional act structure. For application to some recent films, see this entry from 2016 , this one from 2017, and this one from last January. An analysis of The Wolf of Wall Street illustrates the three dimensions of film narrative.

P.S. 15 June: Fiona Pleasance, who corrected my attribution of the prologue’s voice-over, helpfully adds:

It could therefore be argued that not seeing the speakers is a weakness of the film, leading as it does to such confusion.

Personally I believe that, narratively, it does make more sense for the speaker to be N’Jobu. Growing up in Wakanda, as T’Challa does, we can assume he would learn about his country’s past by osmosis, without the need for his father to reiterate it. Such stories become much more important for exiles like N’Jobu and his son.

I believe this does not negate the idea of the father knowing more than the son, which is also addressed in Killmonger’s vision after taking the heart-shaped herb, when he confronts the image of his father, just as T’Challa has done. Also, Killmonger at one point refers to hearing his father tell “fairy stories” about Wakanda, which he came to believe were just that. (Or words to that effect. I’m working entirely from memory; I can’t check as the DVD hasn’t been released in Germany yet!).

Thanks to Fiona for writing! If other readers have further thoughts, they should correspond.

Some of the Badger brigade: Brad Schauer, Vince Bohlinger, Masha Belodubrovskaya, Lisa Dombrowski, Patrick Keating, and Lisa Jasinski.

Wisconsin Film Festival: Confined to quarters

12 Days (2017).

DB here:

I try to watch any film at two levels. First, I want to engage with it, opening myself up to the experience it offers. Second, I try to think about how the film is made, why it’s made this way, and what those practices and principles can teach me about the possibilities of the medium. That second level of response, not easy to sustain in the thick of projection, comes from my research interests, something spelled out as the “poetics of cinema.”

Most critics, particularly those reviewing films on a daily basis, don’t have the time or inclination to reflect on that second level. I’m lucky to have the leisure to mull over what this or that film can suggest about film in general. When a new release points me toward something I think is intriguing, I’ll go back and watch it again. I saw Zama three times last year, and Dunkirk five times. After three viewings and getting the Blu-ray, I think I’m ready to write about Phantom Thread fairly soon.

Several films at the festival set me thinking. Vanishing Point (1971), which I hadn’t seen in a long time, confirmed my idea in Reinventing Hollywood that 1940s narrative strategies resurfaced in the 1970s. (Whew.) We get a crisis structure motivating a flashback, which itself embeds further flashbacks, everything tricked out with plenty of road rage.

Philippe Garrel’s Lover for a Day (L’Amant d’un jour, 2017) reminded me of how important coincidence is in narrative, particularly the accidental discovery of an important item of narrative information. You know, like coming home just as somebody’s about to commit suicide. Or discovering on your way to the WC that your lover’s having sex with someone else. I began to wonder if the episodic nature of art films, which are built more on routines than on sharply articulated goals, gets away with such handy accidents by suggesting that with so many characters drifting around, they’re bound to intersect occasionally. Realism once more becomes an alibi for artifice.

And I was happy to see American Animals (2018), an amateur-heist movie that uses my friend the flashback in a way that cunningly misleads us. I will say no more, except to refer you to other reflections on caper movies, and to express my hope that Ocean’s 8 will offer some fresh twists too.

All of these films employ what we might call omniscient point of view. The film’s narration shifts us among many characters in many places and times. Herewith, though, some thoughts on two films that tie us down.

Elbow room

The Guilty (2018).

One of cinema’s great powers is its ability to shift locales in the blink of an eye. Unlike proscenium theatre, bound to drawing rooms or perspective streets, a film can carry us from place to place instantly. Novels can do this too, of course, and so can certain theatre traditions, such as Shakespeare’s wooden O. But cinematic crosscutting swiftly from one line of action to another and back again is such a powerful tool that many theorists identified it as part of the inherent language of cinema. The medium seemed wired for camera ubiquity.

At certain periods, though, filmmakers kept to single spaces. Early cinema’s one-shot films locked us to a single view, and in the 1910s, long scenes would play out in salons and parlors. Even after the arrival of crosscutting and other editing strategies, some filmmakers embraced the kammerspiel, or “chamber play” aesthetic popularized in Germany. Lupu Pick’s Sylvester (1924), Dreyer’s Master of the House (1925), and other silent films built drama out of micro-actions in tight spaces. Later Hitchcock took this premise to an extreme in Lifeboat (1944), Rope (1948), Rear Window (1954), and to some extent in Dial M for Murder (1954). Rossellini’s Human Voice (1948) is another instance which, like Rope and Dial M, was based on a play.

The confined-space option reemerges every few years. Put aside Warhol’s psychodramas, so well analyzed by J. J. Murphy in his book The Black Hole of the Camera. Most of Tape (2001), Panic Room (2002), Phone Booth (2002), Locke (2013), and Room (2015) follow this formal option. Two striking films from our festival show that this strategy still holds a fascination for directors. They know that spatial concentration can shape the audience’s experience in unique ways.

In The Guilty director Director Gustav Möller ties us to Asger, a Danish policeman assigned to answering calls on an emergency line. A woman caller tells him she’s been kidnapped, and he tries to locate her while also giving her advice on how to protect herself. In the meantime, he summons police units to track the car she’s in and to investigate the household she’s left behind. In the course of this, we come to understand that he’s grappling with his own problems. He’s about to go before a judge for an action he committed on duty, and his partner is going to testify about it. The whole action takes place in more or less real duration, in eighty-some minutes of one night.

The Slender Thread (1965) similarly includes longish stretches confined to a suicide-hotline agency, but it supplies flashbacks that take us into the caller’s past. Here, we stay in place with Asger. By confining us to what he hears, and what little he sees on his GPS screen, the narration obliges us to make inferences that seem reasonable but that turn out to be invalid. I can’t say more without giving away the twists, but it’s worth mentioning how keeping major action offscreen enables the film to summon up the Big Three: curiosity (about the past), suspense (about the future), and surprise (about our mistaken assumptions).

The Guilty is a sturdy thriller, and it certainly works on its own terms. While restricting us to a character, it doesn’t plunge–as many films would have been tempted to do–into his mind, by means of flashbacks or fantasies. These would have “opened out” the film, but lost the laconic objectivity of the action we get.

The film coaxed me to reflect on how the reliance on the conversational situation allowed for a certain looseness at the level of pictorial style. Once we’re tethered to Asger at his workstation, not a lot hangs on choices about camera placement or shot scale. As long as his face, gestures, and body behavior are apparent, niceties of framing count for less. His reaction can be signaled adequately from many angles. He’s so stone-faced that even a 3/4 view from the rear suffices.

In other words, I can’t see that the situation is submitted to a stylistic pattern that would add another dose of rigor to the filmic texture. The style, I think, works to adjust our attention in the moment, in the manner of what I’ve called “intensified continuity,” rather than building longer arcs of pictorial interest. While the plot constraints are strict, the visual style seems less so.

What would be a way to make pictorial style more active? Well, the obvious cases are Hitchcock’s long takes in Rope and optical point-of-view in Rear Window. (And, I’d suggest, his use of 3D in Dial M.) Dreyer did something similar in The Master of the House, in which editing patterns activate a range of props and bits of setting. Films like these benefit from including several characters onscreen, providing details of setting and building up spatial “rules” that channel our vision. Or think of Kiarostami’s auto trips (I almost said “car-merspiel”), which limit camera setups pretty stringently. Ditto Panahi’s ways of stretching the notion of “house arrest” in This Is Not a Film (2011), Closed Curtain (2013), and Taxi (2015)–films that tantalize us with the possibility of glimpsing the world outside.

Möller chose, with good reason, to rivet our attention on two basic elements: the calls and Asger’s responses. The cop’s interactions with others in the office are minimal, and there’s almost no play with props or setting, apart from a moment when Asger decisively snaps down the windowblinds. Our attachment breaks off only at the end, at the conventional moment when the protagonist turns from the camera and walks away.

The tight concentration enhances both plot action and character revelation, and we’re obliged to listen more closely than we do in most movies. Along the way, blinks and eye-shifts and finger-tapping become major events. Still, The Guilty reminded me that every choice cuts off others, forces new choices, sets up constraints–and new opportunities. Film art is full of trade-offs.

12 Day wonder

12 Days (2017).

A more “dialectical” approach to confined space is on display in Raymond Depardon’s documentary 12 Days (2017), probably the most emotionally wrenching film I saw at our fest. The situation is a similar to that in his Délits flagrants (1994), which recorded police interrogations of suspects. The official procedure captured here is a hearing, mandated within twelve days of a patient’s being involuntarily committed to a psychiatric hospital. A judge reviews the case to determine whether the patient should be set free.

Sessions with ten patients take us along a spectrum of disturbance, from a woman believing herself persecuted in her office to a man whose inner voices commanded him to stab a stranger. The last petitioner, a woman sufficiently aware of her illness to admit that she can’t care for her baby, makes a lucid case for being allowed to visit the child occasionally.

All these encounters are shot in a simple but strict fashion. In three reverse-shot setups, we see the petitioner, the judge, and a wider view of the petitioner and the lawyer who states the case.

This neutral approach, far less free-ranging and nerve-wracking than the shots in The Guilty, doesn’t try to amp up the suspense with cut-ins or zooms or pans. It throws all the emphasis on the interchange. Call it Premingerian, if you must.

Sandwiched in between these inquiries are shots of the hospital itself. We’re still confined, in that we never leave the grounds, but these let us breathe a little. Sometimes these interludes are simply quiet tracking shots down empty corridors; sometimes we hear wails and cries behind locked doors; sometimes we see the patients in a rest area, smoking or pacing or simply staring.

By respectfully observing the surroundings, Depardon lets us into a bit of the texture of the patients’ lives and makes us understand that this hospital, while apparently not very oppressive, is still far away from freedom.

Confronting 12 Days we on the outside are forced to balance compassion with prudence. Should a calm, polite man who believes he beatified his father by killing him be allowed free access to our world? Most of the patients we see are remanded for further treatment, but one leaves the judge ambivalent, to the point that we aren’t told of the final decision. We’re left to reflect that to become wholly human, we must confront madness in our midst. As the opening quotation from Foucault has it: “The path from man to true man passes through the madman.”

Thanks as usual to our Wisconsin Film Festival programmers: Ben Reiser, Jim Healy, Mike King, Matt St John, and Ella Quainton. Thanks as well to Tim Hunter for giving us access to Vanishing Point. In all, it was a swell event. See you there next year?

12 Days reminded me that one of the less-known examples of early Direct Cinema was Mario Rispoli’s Regard sur la folie (1962), which presents afflicted patients and their caregivers with a surprising lack of sensationalism.

We’ve written a fair amount about site-specific narratives. I discuss the crystallization of the trend in Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling, and I consider its recent revival in The Way Hollywood Tells It: Story and Style in Modern Movies. On the blog, we’ve discussed Panic Room, Dial M for Murder, The Master of the House, This Is Not a Film, Closed Curtain, and the Kammerspielfilm. And on coincidence, you can drop by here.

12 Days.

Who got played? A guest post by Jeff Smith on THE PLAYER

The Player (1992).

Jeff Smith, our collaborator on Film Art: An Introduction just recorded an installment of our Observations on Film Art series for the Criterion Channel on FilmStruck. Here’s a supplement to that. –DB

In my installment, focusing on genre play in The Player, I discuss Robert Altman’s film in relation to two important traditions in Hollywood cinema: crime thrillers and films about filmmaking. As anyone who knows Altman’s other films would expect, The Player toys with the conventions of both genres in a number of different ways.

As I note in the video, The Player was received as something of a comeback film for Altman. It augured a resurgence in the director’s career that ultimately produced such late masterpieces as Short Cuts and Gosford Park.

Today, I sketch out some additional ideas about The Player’s use of genre conventions. I hope to shed light on some other connections to the crime thriller that I didn’t discuss in the video. I also hope to show just how unusual the film is in this context. Spoilers ahead, not only for The Player but for the novel and film of The Ax.

Will the real Griffin Mill please stand up?

In Reinventing Hollywood, David notes that there are usually four sorts of characters involved in a crime thriller plot: victims, lawbreakers, forces of justice, and more or less innocent bystanders. Filmmakers customarily organize the film’s narration around one or more of these character roles. Typically, a cascade of further choices flows from this initial decision about whose perspective forms the focal point of the story.

In The Player, much of the narration is restricted to the knowledge of the protagonist, Griffin Mill. The film includes a few scenes where Griffin is not present, like the one where the studio’s management awaits his arrival at a meeting. That, in itself, is not unusual. Many thrillers, like Chinatown or The Ghost Writer, employ similar tactics. What is slightly unusual is the fact Griffin takes on two of the typical character roles in the crime thriller as both victim and lawbreaker.

Griffin is a suit, and as a studio functionary he doesn’t immediately engender audience sympathy. Our first glimpse of Griffin shows him listening to pitch sessions. His questions to the people proposing new film projects are glib and capricious, representing the worst aspects of Hollywood commercialism.

Yet The Player does marshall some sympathy for Griffin as the victim of a stalker. Every time Griffin finds a postcard in his mail or on his car, it reminds us that he might be in mortal danger. After the stalker plants a venomous rattlesnake in Griffin’s passenger seat, we can’t believe the threats are empty.

Any sympathy that Griffin garners as a result of this psychological warfare is mollified, though, when the victim becomes victimizer. As Griffin later explains to June, his job is to tell people “no” more than a thousand times each year. Griffin believes that one of these rejections is the reason for the threatening postcards he receives. But he tragically miscalculates in targeting aspiring screenwriter David Kahane as the likely suspect.

Griffin contrives a meeting with Kahane at a Pasadena movie theater, and having bumped into him, tries to make amends. Yet Kahane recognizes that he is being pimped. This leads to a shouting match in a parking lot with Kahane threatening to ruin Griffin’s reputation. And when Kahane accidentally knocks Griffin over with his car door, Griffin reacts with rage, grabbing the screenwriter’s head and banging it repeatedly against the lot’s concrete surface. Although it seems clear that Griffin was acting on impulse, he’s nonetheless crossed a line that separates victims from perpetrators.

More importantly, Griffin’s violent action complicates the viewer’s allegiance to him. Altman establishes a dramatic context in which the motivations for Griffin’s crime seem completely understandable. Yet whatever sympathies viewers might have for Griffin are muddled by his creepy romantic interest in Kahane’s girlfriend; his cruel treatment of Bonnie, his current partner; and the general smarminess he exudes as a successful but shallow executive. Crime thrillers often ask audiences to sympathize with heels. There’s nothing that Griffin does that is inherently evil, but there’s nothing to really like. It’s less about his crime and more about his slime.

Griffin’s passage from victim to lawbreaker also alters the typical thriller plot. At the start of the film, Griffin himself functions as the investigative agent, trying desperately to figure out who is threatening him. Once Griffin becomes a suspect himself, though, that line of action halts, and the Pasadena police’s investigation of Kahane’s death springs up in its place.

This shift in the direction of the plot doesn’t really change the film’s pattern of narration. We remain as ignorant of the police’s activities as Griffin is. What does change are the stakes of the narrative. Instead of eliciting curiosity and suspense about Griffin’s stalker, we now wonder whether he’ll ever be brought to justice for Kahane’s death. Despite its strong connections and frequent allusions to crime fiction, The Player is not so much a whodunit as it is a will-he-get-away-with-it.

They smile in your face, all the time they want to take your place….

Besides blurring the boundaries between Griffin’s role as both victim and lawbreaker, The Player falls into a specific subgenre of crime fiction: the corporate thriller. Since, the corporate thriller is mostly defined by its setting, it blends pretty easily with the typical thriller plots and characters.

Like the spy thriller, the corporate thriller can focus on protagonists engaged in industrial espionage, as we see in Duplicity, Demon Lover, or Paycheck. Christopher Nolan’s Inception blends the plot mechanics of these corporate espionage thrillers with science fiction tropes to provide a narrative frame, but then embeds elements of the heist film within it.

Like the political thriller, the corporate thriller might also focus on the backroom deals and machinations that enable the protagonist to move up the company ladder. A film like Disclosure is a paradigm case. But even romantic comedies or prestige dramas can borrow elements from it. (Think Working Girl and Glengarry Glen Ross.)

More commonly, though, corporate thrillers feature elements drawn from the crime thriller. The roots of this approach to the genre stretch back a long way and can be found in both literary and cinematic antecedents. Some plots, for example, follow investigations that expose corporate malfeasance. Others focus on murders committed within a corporate environment, as in Dorothy Sayers’s novel Murder Must Advertise and Kenneth Fearing’s novel (and film) The Big Clock and in more modern instances like Michael Crichton’s Rising Sun and John Grisham’s The Firm. Other corporate crime thrillers, like Bret Easton Ellis’s American Psycho (below) and Cindy Sherman’s Office Killer, involve serial murders in white-collar environments.

The corporate crime thriller enables writers and filmmakers to explore thematic parallels between the acts of brutality and violence committed by individuals and the cutthroat tactics employed by business institutions. The plots of many gangster films center on rival mobs battling for competitive dominance in black market trades. Such conflicts often seem like a logical extension of the laissez-faire principles that undergird capitalism. Corporate crime thrillers tread similar thematic territory. They sometimes suggest that the personality traits that make for good business executives and titans of industry are the same ones that produce sociopaths and serial killers.

The Player presents the familiar corporate-thriller rivalry, as Griffin works behind the scenes to outmaneuver Larry Levy. For example, Griffin momentarily ponders using Larry’s admission that he attends Alcoholics Anonymous meetings as a way of embarrassing him within the company. Larry quickly undercuts this strategy, though, when he states that he just goes to the meetings because they are a great place to network.

Even more telling is Griffin’s efforts to saddle Larry with a loser project, Habeas Corpus. Midway through The Player, Griffin makes a deal with Andy Civella and Tom Oakley at a Los Angeles restaurant. The next day, he convinces his boss to greenlight the project with Larry as producer, knowing that Tom will likely prove difficult to work with and that his plan to use unknown actors has disaster written all over it. Larry, though, has the last laugh when we get a sneak peek of Habeas Corpus at film’s end. Not only does it have big stars in Julia Roberts and Bruce Willis. It also has the kind of happy ending that the pretentious Tom claimed was too Hollywood when he pitched the project. It turns out Tom cares more about the results of preview screenings than he does the purity of his artistic vision.

Not surprisingly, Altman doesn’t give us a wholly straightforward version of the corporate thriller. In a reflexive and ironic touch, Griffin’s successful ascent to studio boss seems to be secured by the same mysterious stalker who’d been taunting him at the start of the film. In a phone call, the stalker pitches Griffin the plot of the film we’ve just been watching, using his knowledge of Griffin’s crime to leverage his project into development. Here we see Altman slightly reframing the genre’s thesis about the relationship between crime and business. Griffin’s pact with his blackmailing stalker is simply a mildly illicit version of the sorts of quid pro quo arrangements upon which thousands of business deals are made.

If Griffin’s efforts to forestall a rival evoke the political thriller, then his killing of screenwriter David Kahane connects The Player to the corporate crime thriller. Once again, Altman deviates from some of the conventions. The crime doesn’t take place inside a corporate setting, as in Rising Sun and Murder Must Advertise. Griffin kills Kahane in the very public space of a Pasadena parking lot, with film noir overtones.

Similarly, Griffin’s victim is not a colleague, co-worker, subordinate, or client. Rather, Kahane is someone with whom Griffin has had minimal contact, a name plucked almost randomly from a directory of screenwriters in order to jog Griffin’s memory. Consequently, Griffin’s motives for confronting Kahane seem quite different from the culprits in other corporate crime thrillers. More often than not, the murderers in these other stories fear job loss or try to silence others in an effort to cover up some smaller crime or bungled action. Griffin’s actions with Kahane spring from fear about threats to his physical well-being, not from threats to his continued employment. (The latter is Larry’s role.)

Some of The Player’s deviations from more conventional corporate crime thrillers come into relief if we compare it to Donald Westlake’s novel The Ax, a purer example of the genre. The Ax tells the story of Burke Devore, a production line manager recently downsized out of his job at a paper company. Still unemployed after eighteen months, Burke creates a phony job advertisement, and then begins to kill off the seven applicants he believes have the same qualifications he does. His plan is to eliminate all of the other unemployed middle managers in the paper business so that his resumé will land at the top of the pile when a new factory opens in his area.

Some of The Player’s deviations from more conventional corporate crime thrillers come into relief if we compare it to Donald Westlake’s novel The Ax, a purer example of the genre. The Ax tells the story of Burke Devore, a production line manager recently downsized out of his job at a paper company. Still unemployed after eighteen months, Burke creates a phony job advertisement, and then begins to kill off the seven applicants he believes have the same qualifications he does. His plan is to eliminate all of the other unemployed middle managers in the paper business so that his resumé will land at the top of the pile when a new factory opens in his area.

Like Altman, Westlake has some fun with his central conceit. Just as The Player includes faux film clips and rushes as a means of satirizing Hollywood production practices, The Ax incorporates fictional resumes that tweak jobseekers’ business-speak. What makes Westlake’s social criticism in The Ax so resonant, though, is the utter banality of Burke’s ambitions. He doesn’t aspire to the garish lifestyle we see displayed by Tony Montana or Jordan Belfort in Scarface and The Wolf of Wall Street respectively. Instead Burke just wants to return to his modest middle-class lifestyle and to the dignity that a decent job afforded him. Serial murder just seems like the simplest way to achieve that.

As this comparison suggests, one of the things that makes The Player somewhat unusual as a corporate crime thriller is its play with character motivation and point of view. Facing threats and intimidation, Griffin looks more like the target of a crime than a perpetrator. In corporate thrillers, the lawbreaker is more likely to be somewhere in the middle of the corporate ladder, like Burke, than at the top of it. Moreover, although his actions are motivated by a strange combination of both vanity and insecurity, Griffin more or less stumbles into the crime he commits rather than coolly plotting it the way Burke does.

Despite these differences, The Player and The Ax share an important feature that markedly deviates from the crime thriller as a whole. Both Griffin and Burke get away with it. The plots of most crime thrillers resolve in ways that balance the scales of justice. The bad guys are usually either arrested or killed after climactic confrontations with law enforcement. But this doesn’t always happen. Burke, Patrick Bateman in American Psycho, and Dorine in Office Killer escape punishment. Even though Jordan Belfort is arrested in The Wolf of Wall Street, he gets a slap on the wrist for his crimes.

Perhaps this aspect of the corporate crime thriller reflects the cynicism and amorality that pervades the genre. After all, if your belief is that most corporations get away with murder in a figurative sense, then it’s not hard to accept this idea when it occurs in fictional contexts in a literal sense.

Still, in the case of The Player, the Pasadena police’s failure to prove their case against Griffin Mill may reflect a meshing of both authorial and generic tendencies. When Griffin embraces June in the stylized happy ending of The Player, it quite deliberately parallels the tacked on happy ending of Habeas Corpus we’ve seen just moments earlier. The dialogue Griffin exchanges with June amplifies the similarity between these scenes. When June asks, “What took you so long?”, Griffin responds, “Traffic was a bitch.” These are the exact same lines exchanged by Julia Roberts and Bruce Willis in Habeas Corpus. By allowing Griffin to get away with it, The Player’s “up” ending sharpens Altman’s critique of Hollywood convention, and allows him to subvert the kinds of mainstream genre filmmaking he’s long detested.

Both allusive and elusive: Comparing The Player to Hollywood Story

One of the other topics I discuss in my video essay on The Player is the way the film pays homage to various aspects of Hollywood tradition. Much of this is bound up with its satire of commercial filmmaking. But it also strengthens the film’s relation to the crime thriller. Throughout The Player, Altman makes reference to Hollywood’s past in multiple ways. Celebrity cameos, film posters, and production stills populate the mise-en-scene. The characters also frequently mention older film titles in dialogue.

Perhaps the most interesting allusion in The Player involves a poster of Hollywood Story that hangs in Griffin’s office. The latter is a 1951 film noir directed by William Castle, who later became famous for his use of outrageous gimmicks in the production and promotion of horror films. For The Tingler, Castle supervised the installation of devices that would vibrate theater seats, anticipating today’s 4DX Theater Experience in places like Los Angeles, New York, Seattle, and Orlando.

Hollywood Story dramatizes the efforts of film producer Larry O’Brien to develop a project around the unsolved murder of silent film director Franklin Ferrara. O’Brien hires one of Ferrara’s old scenarists to write the script. He also develops a close relationship with Sally Rousseau, the daughter of one of Ferrara’s biggest stars. Once the project is announced, O’Brien finds himself the target of an assassin’s bullet. He surmises that his assailant is trying to prevent the case from being reopened. And as Sally reminds O’Brien, he doesn’t have an ending to his movie is he can’t determine the killer’s identity. O’Brien, thus, sets out to solve the crime, bringing closure to one of the biggest scandals in Hollywood’s history. Hollywood Story offers an even better synthesis of The Player’s mixture of industry exposé and crime film story beats. O’Brien’s lone wolf investigation is treated as being a necessary stage of project development.

If the Franklin Ferrara story sounds vaguely familiar to you, well….it should. Hollywood Story offers a fictionalized account of the unsolved murder of William Desmond Taylor, who was shot to death in his bungalow in the wee hours of a February night in 1922. (David blogged about the crime here.) The subsequent investigation of Taylor’s death ensnared some of the industry’s biggest stars of the period. Mabel Normand’s reputation was tainted by her association with Taylor and by reports of drug use. She took a brief hiatus from filmmaking because of the scandal, but never completely recovered from it. Normand later died of tuberculosis in 1930 at the tender age of 37.

As a fictionalized account of a notorious unsolved crime, Hollywood Story anticipates more modern thrillers that provide speculative solutions to real-life murders. Zodiac and The Black Dahlia are prime examples, as are any number of Jack the Ripper films. Hollywood Story’s approach was not unprecedented. James M. Cain based Double Indemnity on the Ruth Snyder case that was fodder for New York tabloids in the late 1920s. That said, Taylor’s death lingered for decades in popular memory in a way that the Snyder case did not.

What are we to make of The Player’s citation of Hollywood Story? On the one hand, viewers might well notice the almost immediate parallel of our “film execs in jeopardy” storylines. Just as Griffin is stalked by an unknown assailant, so, too, is Larry the target of a shadowy aggressor. Moreover, Hollywood Story, along with Sunset Boulevard, might well be an inspiration of one of The Player’s most interesting features: its intermingling of real life stars with fictional characters. Hollywood Story includes cameos by Joel McCrea and several noted performers of the silent era, such as William Farnum, Francis X. Bushman, and Betty Blythe (below). The Player pushes this aspect of Hollywood Story to extremes, containing plentiful cameos by Cher, Jack Lemmon, Burt Reynolds, Lily Tomlin, Susan Sarandon, and other A-listers.

In several other respects, though, The Player seems like an inversion of Hollywood Story with Griffin emerging as a more venal counterpart to the latter’s crusading producer, Larry. In Hollywood Story, Larry’s investigation actually produces results. This strongly contrasts with Griffin’s guesswork, which, as the result of a tragic mistake, leads to David Kahane’s death in a Pasadena parking lot. In Hollywood Story, Larry’s blossoming romance with Sally furnishes the standard double plotline commonly found in classical cinema. In The Player, though, Griffin’s interest in June seems genuinely sleazy. It also exacerbates the Pasadena police’s doubts about Griffin’s alibi, making him their prime suspect. Finally, the revelation of screenwriter Vincent St. Clair as Franklin Ferrara’s killer provides closure both to Larry’s script and to Hollywood Story itself. In contrast, none of the crimes presented in The Player are really solved. Griffin is blackmailed into greenlighting a project during the film’s epilogue, but the audience never learns the identity of the mysterious stalker. Similarly, although the Pasadena police believe that Griffin is guilty of murder, the botched lineup ensures that he will go free and that David Kahane’s death will remain an unsolved crime. In an odd way, The Player returns to the narrative roots of Hollywood Story. The fate of Kahane, our aspiring screenwriter, seems destined to mirror that of poor William Desmond Taylor, our successful silent film director.

A thriller with no thrills

I’ve sketched out a number of different ways in which The Player relates to the basic conventions of the crime thriller, but all of this is ultimately, in the parlance of the genre, a red herring. This is because The Player is that rare bird: a crime film that engenders relatively little curiosity about its solution and even less suspense about the fate of its protagonist.

This is largely because Robert Altman mostly uses crime film conventions as scaffolding for the things that really interest him: quirky characters, digressive dialogue, and a loose, improvisatory feel to the film’s performances. At its heart, The Player is a comedy that draws upon crime film conventions in much the way Altman’s adaptation of Raymond Chandler’s The Long Goodbye does.

Compare, for example, each film’s tweaking of the genre’s standard interrogation scenes. In The Long Goodbye, Detective Farmer’s tough questioning of Philip Marlowe is punctured by the latter’s goofy responses. At one point, Marlowe uses the ink from his fingerprinting procedure like it was the “eye black” used by an athlete. Later, he smears the ink all over his face and sings “Swanee” in a mocking homage to Al Jolson in blackface. Similarly, in The Player, the Pasadena police’s interrogation of Griffin is disrupted by Detective Avery’s disarming exchange with her partner about tampons, her mangled pronunciation of “Gudmundstottir,” and her dialogue with Paul about Todd Browning’s Freaks.

The Player has many ingredients characteristic of crime films: a dead body, an investigation, a shady suspect, and a campaign of stalking and extortion. Yet, by the time Altman’s film reaches its ironic and deeply reflexive conclusion, viewers might well conclude that they are the ones who just got played.

Thanks as usual to Peter Becker, Kim Hendrickson, Grant Delin, and all their Criterion colleagues. A list of our Observations on Film Art series is here.

For more on Robert Altman’s career, see Patrick McGilligan’s excellent biography, Robert Altman: Jumping Off the Cliff. There are also several books featuring interviews with the iconoclastic director. These include David Sterritt’s Robert Altman: Interviews, Mitchell Zuckoff’s Robert Altman: The Oral Biography, and David Thompson’s Altman on Altman.

Those interested in learning more about crime fiction should consult Martin Rubin’s Thrillers, Charles Derry’s The Suspense Thriller: Films in the Shadow of Alfred Hitchcock, John Scaggs’s Crime Fiction, Richard Bradford’s Crime Fiction: A Very Short Introduction, and Martin Priestman’s The Cambridge Companion to Crime Fiction.

Hollywood Story (1951).