Archive for the 'Narrative strategies' Category

Everything new is old again: Stories from 2017

Silence.

DB here:

This is a sequel to an entry posted a year ago. Like many sequels, it replays the ending of the original.

I don’t want to leave the impression that as I’m watching new release a little homunculus historian in my skull is busily plotting schema and revision, norm and variation. I get as soaked up in a movie as anybody, I think. But at moments during the screening, I do try to notice the film’s narrative strategies. Later, when I’m thinking about the movie and going over my notes (yes, I take notes), affinities strike me. By studying film history, most recently Hollywood in the 40s, I try to see continuities and changes in storytelling strategies. These make me appreciate how our filmmakers creatively rework conventions that have rich, surprising histories.

Parts of those histories are traced in the book that came out in the fall, Reinventing Hollywood. Some of my blog entries have already served to back up one point I tried to make there: that contemporary filmmakers are still relying on the storytelling techniques that crystallized in American studio films of the 1940s.

Relying on here means not only utilizing but also, sometimes, recasting. In keeping with earlier entries (including one from the year before last), I want to explore some films from 2017. These show that the process of schema and revision creates a tradition. Hollywood is constantly recycling, and sometimes revitalizing, Hollywood.

Of course here be spoilers.

Back to basics

The Big Sick.

The US films I’ll be considering all adhere to canons of classical Hollywood construction. Some of these are laid out in the third chapter of Reinventing.

Classically constructed films have goal-oriented protagonists who encounter obstacles, usually in the form of other characters. The goals are often double, involving both romantic fulfillment and achievement in some other sphere. (Somewhere Godard says that love and work are the only things that matter. Hollywood often thinks so too.) Alternatively, the goal might be prodding someone else to action (Three Billboards outside Ebbing, Missouri). Often there’s a clash between the goals, as when work tugs the protagonist away from love (La La Land).

The plot is typically laid out in large-scale parts. A setup is followed by a complicating action that redefines character goals. In Downsizing, once Paul has gotten small, he has to reconceive his goals in the face of his wife’s last-minute defection from their plan. There follows a development section that delays goal achievement through characterization episodes, backstory, subplots, parallels, setbacks, digressions, twists, and new obstacles. That marvelous slab of show-biz schmaltz, The Greatest Showman, relies for its development on a potential love triangle and a secondary couple’s romantic intrigue.

There follows a deadline-driven climax that resolves the action and an epilogue (sometimes called the tag) that celebrates the stable state achieved and perhaps wraps up a motif or two. The Greatest Showman presents Barnum’s success in creating a genuine circus and reconciling with his family. The tag shows a big production number, with the subplot resolved (Carlyle embracing Anne) and the motif of swirling points of light—initiated in Barnum’s spinning Dreams gadget—washing over the final spectacle and his daughter’s ballet performance.

Classical narration—what’s usually called point of view—typically attaches us to the main characters. But not absolutely: we’re usually given access to things they don’t know, mostly for the sake of arousing curiosity and suspense. And throughout, the film is bound together through recurring motifs that reveal character (and character change) or significant plot information. Think of the roles Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2 assigns to “Brandy, You’re a Fine Girl,” Pac-Man, David Hasselhoff, and that “unspoken thing.”

Or take The Big Sick, a semi-serious romantic comedy. Kumail’s initial goal is success in standup comedy, but he also falls in love with Emily. His Pakistani-American family constitutes the main antagonist, as his mother and father want him to go to law school and submit to an arranged marriage. He hasn’t told his family about Emily, which precipitates the couple’s big quarrel: “I can’t lose my family.” Kumail’s goal shifts when Emily is stricken by a mysterious disease. In the development section , as she lies in a coma, he gets to know her parents, and a tense sympathy develops between them. The crisis comes when Kumail confesses his true goals to his parents, they disown him, and Emily’s disease hits a life-threatening phase.

In the climax portion, Emily revives and breaks off with him, his parents grudgingly accept his move to New York, and he mounts a somewhat successful one-man show there. The film is tightly tied to Kumail’s range of knowledge, so we’re surprised when he is—as when Emily’s parents decide to move her to another hospital, and when Emily pops up in his New York audience, ready to reconcile with him.

The Big Sick exploits many comic motifs: the parade of would-be fiancées Kumail’s mother invites to dinner, the photos he keeps of them (which ignite Emily’s jealousy), the repeated sit-downs he has with his family, the dumb catchphrases deployed by other comics, and especially Emily’s “Woo-hoo!” heckling, which eventually attests to the rekindling of their love.

The power of classical plotting is shown in its ability to spotlight a Pakistani-American protagonist, an Islamic family demanding that a son adhere to tradition, and the pathos of parents facing the death of a daughter. But that ability to flexibly absorb new subjects and themes and emotional registers has kept the classical template going for about a century.

Time travel

Wonder Woman.

One of the hallmarks of Forties cinema, I argue in Reinventing’s second chapter, is a eagerness to explore what flashbacks can do. Flashbacks were already well-established, but a more pervasive acceptance of nonlinear storytelling, so familiar to us now, became firmly part of Hollywood sound cinema in this period.

One-off flashbacks are so common now we don’t particularly notice them. In The Big Sick, when Kumail visits Emily’s apartment with her parents, he peeks into her closet, and we get glimpses of her wearing the outfits earlier in the film. In this case, flashbacks function as memories. At the climax of Guardians 2, Quill flashes back to moments of listening to music with his mother. Similarly, in Get Out, Chris recalls his childhood TV viewing and, at the climax, he remembers earlier moments at the Armitage garden party when he asks, “Why black people?”

Flashbacks usually aren’t pure representations of memory, though. They often include information that the character doesn’t or couldn’t know. In fact many flashbacks are addressed simply to us, coming “from the film” rather than from a character’s mind. These may remind us of things already seen, or fill in gaps, or plant hints about things that will develop.

So, for instance, in Logan Lucky, when Logan says, “I know how to move the money,” we get a flashback to him studying the pneumatic pipes that feature in the heist plan.

He’s not necessarily recalling the moment; the filmic narration seems merely to be tipping us the wink. At the climax, other “external” flashbacks plug gaps we didn’t notice earlier. These reveal some aspects of the heist we weren’t aware of, such as the extra bags of money carried off.

1940s filmmakers also explored how flashbacks could be “architectonic,” how they could inform the overall shape of the movie. Here the flashback rearranges story order to build up curiosity and suspense, and it may come from purely from the narration or be motivated as character memory.

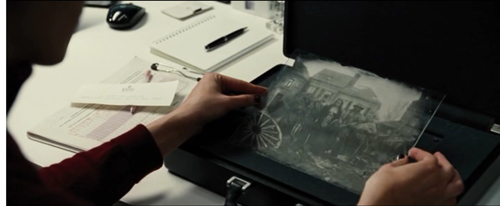

One large-scale pattern is the extensive embedded flashback, as in How Green Was My Valley, I Remember Mama, and innumerable biopics. Wonder Woman gives us a framed inset of this sort, when a modern-day Diana opens the chest harboring the World War I photo. That scene segues to the past. The origin story and war episodes are ultimately closed off by a return to the present, and a reminder of a motif—Steve’s watch (which, in one of the film’s jokes, stands in for something more private). The purpose of this is to provide what I call in the book “hindsight bias.” While building curiosity about the past, the opening primes us to expect certain things to have been inevitable (such as chance meetings).

Another common framing strategy begins at the climax and then a long flashback lays out the conditions that led up to it. A reliable source tells me that Pitch Perfect 3 does this, starting with an explosion followed by a title announcing that the action began three weeks earlier. In films like this, there may be no closing frame; the internal action of the flashback catches up, perhaps via a replay, with what we saw at the outset, and the film proceeds to the resolution and epilogue. The somewhat phantasmic opening number of The Greatest Showman comes to fruition during the finale.

To and fro

Loving Vincent.

Sustained blocks like this are fairly rare nowadays, I think. More common, as in the Forties, is an alternation of past and present. The main examples in Reinventing Hollywood include Passage to Marseille, The Locket, Lydia, Kitty Foyle, and Sorry, Wrong Number. Again, though, these are motivated as memories, while current examples tend to be more “objective.”

A simple instance is Film Stars Don’t Die in Liverpool. Here clusters of events in 1981 alternate with incidents in 1979: Gloria Grahame returns to her young lover, and we flash back to their earlier affair. Neither protagonist is firmly established as recalling the 1919 events. Another feature of 1940s flashbacks, the replay from different viewpoints, comes in here as well. The couple’s crucial quarrel in New York is shown first from Peter’s perspective, and later from Gloria’s. He suspects her of infidelity, but we learn that her secret involves her cancer. As often happens, our restriction to the protagonist is modified by knowledge he doesn’t gain at the moment.

The alternation of past and present is given a more geometrical neatness in Wonderstruck. In maniacally precise parallels, Rose in 1927 runs away to Manhattan to find her mother, while in 1977 Ben runs there to find his father.

The parallels are reinforced by a host of motifs: wolves, movie references, the asteroid in the Museum of Natural History, a bookmark, and so on. The linear chronology gets straightened out, and the gaps filled, by an integrative flashback played out among miniatures and cutouts adapted to the scale model of Manhattan. The dovetailing flashbacks create a sense of cosmic design; in many films, convergences like these can suggest destiny.

For modern audiences, Citizen Kane is the prototypical flashback film of the 1940s, and its investigation structure, while not completely original, was hugely influential. I was surprised to see Kane’s schema revived this year in Loving Vincent. Once the postman has given Armand his mission, to take Vincent’s last letter to brother Theo, we embark on an inquiry into Vincent’s life and death. It’s refracted through the testimony of many who knew him during his sojourn in Arles. Armand’s goal gets recast when he learns of Theo’s death, but in the course of his travels he comes to understand how Vincent’s kindness and art touched many lives.

As in several Forties films, Loving Vincent’s past scenes jumbled out of chronological order, so we must piece together the story Armand gradually discloses. And there’s the driving force of mystery, a distinctive thrust in many Forties genres, for reasons I talk about in one chapter of Reinventing. Very modern, and not so much like the 1940s, is the brief, fragmentary quality of the flashbacks; I counted thirty-six of them.

The boldest experiment in nonlinear time I saw this year was Dunkirk. The film juxtaposes timelines consuming a week or so, a day, and an hour, and then aligns them in unexpected ways. In this staggered array, the distinction between flashbacks and flashforwards loses its force. Any cut may constitute a jump ahead of the moment just shown, or a jump back to an earlier incident. Christopher Nolan has acknowledged the influence of 1940s cinema on his thinking about time schemes, and here he explores yet again how crosscutting different lines of action can stretch or condense story duration.

Their eyes and ears

Get Out.

Like flashbacks, subjectively tinted storytelling has a long cinematic lineage. Silent films displayed dreams, visions, anticipations, and deformations of mind and eye. Those devices mostly dropped out of 1930s American cinema, which was to some extent more “objective” and “theatrical” in its mode of presentation. Subjectivity came roaring back in the Forties, which is why Reinventing Hollywood devotes two chapters and several other passages to various techniques that go beneath the surface.

Memory-based flashbacks are common options today, but the inward plunge can take other forms. For most of its length, Get Out restricts us to Chris’s range of knowledge, and it relies on optical POV in many stretches. Through his eyes we see Mrs. Armitage staring at him while stirring the tea.

More complex is his view of Georgina at the upper window. That’s followed by a shot going beyond his range of knowledge: she’s looking not at him but herself.

We take a deeper dive into Chris’s mind under hypnosis. The boy Chris sinks into a stellar cavity and becomes Chris staring at Mrs. Armitage as if she were appearing on the TV screen. The shift dramatizes his guilt at his mother’s death and his susceptibility to this Bad Mom figure.

Once Chris becomes a prisoner, the narrational range widens again to show Rod’s efforts to rescue him, along with the family’s plans for him. But the film tightly realigns us with Chris at the climax, so that the attacks from Rose, Jeremy, and others come as surprises.

Chris, a photographer, channels his experience through vision, though the hypnotism scene blends sounds from the present with the rain drizzling in the past. Subjectivity goes more fully sonic in Baby Driver, about a whey-faced lad who lives in the auditory ether.

Edgar Wright, now exercising straight the percussive dashboard details he parodied in Hot Fuzz, punches up the visual exhilaration of Baby’s rubber-shredding takeoffs and getaway 180s. He locks us into Baby’s auditory world as well. We’re almost completely attached to Baby, learning what he learns when he learns it. Notably, the robberies are rendered from his perspective, including optical POV shots as he waits in the getaway car.

Again, fragmentary flashbacks replay his mother’s death and the childhood damage to his hearing. We even get a fantasy, with Baby imagining his escape with Debora in black and white.

What’s just as subjective, though, is the music Baby incessantly cues up on his iPod. Blocking out the shriek of his tinnitus, it provides a soundtrack to his life—danceable tunes as he bops down the street, ballads when he flirts and falls in love with Debora, and pulsing rock during robberies (what the psycho Bats calls, “a score for a score”). Through volume and texture, Wright suggests that we hear the music as Baby does; only the loudest environmental sounds poke through. Sometimes, when he pulls out one earbud, the volume drops. His growing attachment to Debora is signaled by his dialing up a song using her name and sharing his precious buds.

Some scenes are handled objectively, as we witness the gang’s conversations in front of Baby. He can read lips, though, and he can keep the iPod cranked up. So a little bit of Baby’s custom soundtrack leaks in for us underneath others’ dialogue. At other times, the score takes over to become nondiegetic accompaniment, as when gunshots in a firefight land on the off-beats of “Tequila.”

As you’d expect, the music comments on the action throughout (“Never ever gonna give you up” when Baby defends Debora from Buddy) and supplies motifs. Queen’s “Brighton Rock,” Baby’s favorite heist accompaniment, briefly enables him to bond with Buddy.

A song about a couple’s devotion reminds us that both thieves are loyal to their women.

Momentary sound changes are rendered through our protagonist’s viewpoint. Wright lets us hear the whine of Baby’s tinnitus as Bats taps his ear. When Buddy blasts his pistols alongside Baby’s head, we suffer his hearing loss and the distorted voices that wobble through it.

Such streams of auditory perception occasionally emerged in early talkies (e.g., Gance’s Beethoven). Those experiments got normalized in 1940s manipulations of sound perspective in different environments. More fancily, in A Double Life (1947), party chatter subsides when the hero covers his ears, and in Pickup (1951), the gradually deafening protagonist hears high-pitched noises. Wright extends these one-off devices to the texture of an entire film.

Confidants

The Keys of the Kingdom (1945).

Large-scale and small-scale, the heritage of the 1940s seems to be everywhere. Many of the flashbacks and fantasies I mentioned already are primed by a track-in to a character’s face, just as in classic studio pictures. There’s also block construction, either unsignaled as in the Wonder Woman and Greatest Showman cases, or signaled, as in the date-stamping in the early alternations of Film Stars Don’t Die in Liverpool. We also get explicit chaptering, as in The Meyerowitz Stories (New and Selected) and Norman: The Moderate Rise and Tragic Fall of a New York Fixer.

Voice-overs come along with flashbacks, as a way of guiding the audience to understand the time shifts. In the Forties, as I discuss in the book’s sixth chapter, voice-overs became more flexible and fluid. Sometimes they were external, issued from an all-knowing commentator (Naked City and other police procedurals). Sometimes they were sonic equivalents for letters and diaries, letting us in on what characters were writing. Deeper intimacy could come from voice-overs serving as inner monologues, the voice of a character’s mind. These, like flashbacks, are associated with film noir, but also like flashbacks they actually emerge in many genres–as they do today.

The voice-over can be perfunctory, as in All the Money in the World. Young Paul Getty, kidnapped in the opening reel, has a couple passages confiding in us, but he’s not heard from again. Moreover, his explanation of his grandfather’s rise to power (during the inevitable flashbacks) could have been supplied in other ways. Paul baldly tells us that we need to know all this to understand what follows (who’s he talking to?). He admits that he’s an expository shortcut. This is why voice-over is sometimes considered lazy storytelling.

It doesn’t have to be. Take Martin Scorsese’s Silence. In subject and strategy it reminded me of The Keys of the Kingdom (1945), which dramatizes the diary of a young missionary to China. Via this novelistic device, we get flashbacks to his youth and his years of service. We get as well the reaction of the skeptical priest whose voice reads the journal. This fairly straightforward schema is in effect revised by Scorsese and co-screenwriter Jay Cocks, who create a floating dialogue among voice-overs.

After initial exposition via an old letter from Father Ferreira, which is recited in his voice, two young priests set out for Japan. They hope to maintain the clandestine Christian community there, and they want as well to discover if Ferreira has truly renounced his faith . The bulk of their grim adventures is commented on through the voice-over of one of them, Father Sebastião Rodrigues. At first he’s vocalizing a letter, which he calls a report, summing up the struggles of the Jesuit mission and their encounters with Christian villagers. In the course of his report, we also get an embedded flashback narrated by Kichijiro, their guide and a sporadically lapsed believer himself.

But at a crucial moment, Father Sebastião’s report ceases to be such and turns into an inner monologue. Seeing a Christian village devastated by the shogun’s forces, he asks, “What have I done for Christ?”

Soon his voice presents a kind of stream of consciousness–praying for the villagers as they walk off in captivity, thanking God when he has a vision of Jesus on his prison wall. His inner voice urges his colleague Father Garupe, severely tortured, to apostatize.

In last stretch of the film, new voices are heard. There’s Jesus, perhaps filtered through Sebastião’s mind (subjectivity again), and then, more objectively, there’s an account from the Dutch trader Albrecht. He drily reports that Sebastião apostatized and followed Ferreira in leading a Japanese life. Albrecht’s narration is interrupted by a dialogue between Sebastião and Jesus, capped by the priest’s blurting out: “It was in the silence that I heard your voice.” Albrecht’s voice-over concludes the film, with his final claim that the priest was “lost to God” belied by the closing image.

From the 1940s onward, voice-over has been a rich resource–describing settings and external behavior, judging other characters’ motives, giving us access to the deepest thoughts of the speaker. I try to show these capacities at work in a fairly ordinary film, The Miniver Story, but for our time, the soundtrack of Silence is another vivid demo. In the juxtaposition of different voices, it achieves some of the density of a novel, and by the end we better understand the initial words and emotions of Father Ferreira, the priest whose apostasy launches the plot.

Passed-along voice-over gets a bigger workout in Dee Rees’s Mudbound. The original novel is somewhat like As I Lay Dying; its sections set various characters’ voices side by side, shifting viewpoint as each takes up a portion of the tale. Constant commentary and perfect alignment with a character’s range of knowledge are hard to sustain in cinema, so what we have onscreen are objectively presented scenes accompanied by an occasional voice-over. Still, it’s a rare option. If Silence gradually opens its voice-over horizons near the film’s end, Mudbound introduces polyphony from the start. Six characters share their thoughts and feelings in alternation, providing backstory and deepening our access to their reactions.

As in Silence, there’s a pattern to the voice-overs. The bulk of the film is an embedded flashback, triggered by the McAllen brothers setting out to bury their father and encountering the Jackson family riding by.

The intersection of two families sets up not only the flashback episodes but the floating voice-overs. As the visuals anchor us initially to the white family, the first voice-overs issue from Laura, the wife of Henry McAllen, and from Henry’s brother Jamie. In the flashback stretch, as America enters World War II, the voice-overs shift to the Jacksons, the father Hap and the mother Florence. The plot proceeds to add the voices of Henry and the Jacksons’ oldest son Ronsel. All the characters narrate the action in the past tense, as if recalling it from a distance in time, but no listener is ever specified–a common feature of voice-overs in the 1940s and afterward.

During the film’s second half, the development and climax sections, the voice-overs nearly vanish. For over an hour, we hear only Laura and Florence, and only once apiece. Jamie and Ronsel, both disaffected returning vets, don’t confide in us during their growing friendship or during the persecution of Ronsel by the local white men. The women are left to provide a sporadic chorus.

At the end, however, a spurt of brief commentaries give the men their inner voices back. We return to the present and see Hap Jackson help the McAllen men bury their father (the inciter of KKK violence against Ronsel). The epilogue features brief comments from Ronsel, Jamie, and Hap, and not the women. Ronsel gets the last word. Ironically, because of the KKK savagery, this narrator has become mute.

Again, I felt a current film’s kinship to those I studied for the book. Mudbound traces the rural home front, the military experiences of a white man and a black one, and the veterans’ problems of adjustment upon returning home. These elements hark back to some of the powerful films of the 1940s, including Home of the Brave and The Best Years of Our Lives. The sympathetic portrait of African-American families isn’t unprecedented either, as seen in Intruder in the Dust and Lost Boundaries. Mudbound‘s passed-along narration, like the ones we find in other modern films, constitute contemporary revisions of the shifting voice-overs we get in Citizen Kane and All About Eve.

Career women careening

Molly’s Game.

Molly’s Game and I, Tonya offer good wrapup examples of many of these strategies, with some unreliability thrown in.

As you’d expect in a film by Aaron Sorkin, the flashback organization of Molly’s Game is fairly complicated. Just as The Social Network intercut two arrays of flashbacks triggered by two legal inquiries, the new film scrambles together crucial moments in Molly’s childhood , scenes of her current legal troubles, and sequences showing her rise to become the Poker Princess, the arranger of high-stakes games. The film gains a bit of the structural symmetry of Wonder Woman by beginning and ending with a childhood defeat that Molly rises above.

The flashbacks are stitched together by Molly’s voice-over. A filmmaker who recruits a narrating voice has to choose. Do you show the narrating situation? Or do you leave it unspecified? In this last instance, the narration might be wholly internal, a mental summing up of events, or it might feel like a confidence shared with an intimate, even though we’re shown no listeners. In Molly’s Game, her bare-it-all confession might seem to be simply her unspoken thoughts, but at one point it’s suggested that what we’re getting is her book’s version of her life.

Molly’s attorney Charlie is reading her memoir while he researches her case, and he asks her about a passage we saw in a flashback: her boss chews her out for bringing him “poor people’s bagels.” The attorney suggests that nobody uses that phrase, and that probably the boss used a racial slur that she suppressed in the book. This throws a little bit into question the reliability of Molly’s flashback, while also hinting at something we learn later: she sanitized the book to spare the reputations of the high rollers she serviced.

I, Tonya takes another option. Again there are disordered flashbacks and bursts of subjectivity tied together by the voice track. Whereas Molly is the sole speaker in her film, though, Tonya shares the soundtrack with other characters, in the manner of Mudbound. But these commentaries aren’t private musings. They’re the self-justifying testimony of people talking to a documentary camera. (Even though these sequences are said to be occurring forty years after the earliest events, the format is an anachronistic 4:3–presumably to help us keep the time frames distinct.

Once you get characters in conflict recounting past events, you have the possibility of disparate stories. Forties filmmakers exploited this in Thru Different Eyes and a certain Hitchcock film too famous to mention. Tonya says explicitly that there are different versions of the truth. A brief scene shows her battering Nancy Kerrigan, and a more complicated one occurs in a tale recounted by her husband Jeff. She fires a shotgun at him and turns to the camera saying, “I never did this”–before briskly ejecting a shell.

The comic possibilities of to-camera address on display here were exploited in My Life with Caroline, Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House, and other 1940s films. Then the momentary breaking of the fourth wall was reserved for the frame story and kept separate from the embedded flashbacks. But I, Tonya‘s revision is easy to understand as a zany equivalent for her verbalized denial. Given the defiant way she brandishes the gun, we’re permitted to doubt her denial–which means that the film is refusing to settle the matter. The possibility that the overall filmic narration could be unreliable was rehearsed occasionally in the Forties, perhaps most vividly in Mildred Pierce (analyzed here, sampled here).

Other paths

Foxtrot.

The 1940s were important for other national cinemas too. The book’s last chapter suggests that filmmakers in Britain, France, Mexico, and other countries engaged in similar narrative explorations–sometimes in imitation of America, sometimes on their own. I go on to suggest that eventually non-Hollywood narrative models came to international attention, and still later those affected American cinema.

Italian Neorealism was a prime source of alternatives. A good example of its long-term impact, I think, is The Florida Project, which embraces a slice-of-life pattern. Once you’re committed to episodic plotting, you need to organize the incidents coherently. Sean Baker follows European and US indie precedent in tracing a rhythm of daily routines that change in sync with the characters’ relationships. So Halley’s quarrel with her friend Ashley means that Moonee can no longer claim leftover food from the diner, which helps push Halley toward prostitution, which leads to the intervention of child welfare authorities.

The drama arises less from crisply defined goals than from circumstances that alter life routines. In addition, like many Neorealist films and others in this vein afterward, the poignancy gets sharpened by the presence of children caught up in adults’ bad choices.

The Florida Project presents many actions elliptically, leaving us to infer what has happened offscreen. (I think, for instance, that it’s motel manager Bobby Hicks who contacts the authorities, but I don’t think it’s made explicit.) Moving to films made outside the US, Michael Haneke’s Happy End takes ellipsis even further.

Haneke uses the strategy of delayed and distributed exposition. He presents some apparently casual events at the outset, then gradually reveals what’s actually going on, all the while tracing out ultimate consequences. Instead of presenting a clear-cut chain of causes and effects, he asks us to fill in unspoken plans, offscreen actions, and hidden motives. Haneke has specialized in suggesting how vague forces can disturb rich, smug families and their shady schemes. His mystery-driven narrational tactics suit Happy End as well as Code inconnu and Caché.

I speculate in Reinventing Hollywood that the European art cinema’s story-based mysteries and narrational uncertainties owe something to 1940s American films. So too perhaps does the use of block construction, which emerged in overseas portmanteau films of the postwar era (e.g., Dead of Night, Le Plaisir, The Gold of Naples). Samuel Maoz’s Foxtrot is a striking example of block construction.

His Lebanon (2009) took POV restriction to a limit by confining its action to a military tank in the heat of battle. (This tactic has Forties precedents as well, as Lifeboat and Rope remind us.) Foxtrot operates differently. Broken into three parts, it looks at a single situation–a young soldier’s duties at a checkpoint–through shifts in time and viewpoint. The opening shot, at first enigmatic, gets specified in an epilogue that recasts all that went before. Maoz also incorporates monotonous routines into his plot, the better to throw a single shocking incident into relief.

So classical construction isn’t the only option available. But other choices have histories as well. As viewers we learn these alternative stoytelling traditions, and we use that knowledge to make sense of new examples. No less than the Hollywood model, these other formal strategies engage us through familiar pattern and unexpected novelty, schema and revision.

I don’t mean to obsess over this 1940s thing. Our current films owe debts to silent cinema and to other eras too. It’s just that I continue to be fascinated by finding repetitions and variants of storytelling strategies that got consolidated in the period I was studying. Denounce them as formulaic if you want, but I prefer to think that these and other recent films illustrate, in fine grain, the continuity and sometimes the vitality of a major cinematic tradition.

Maybe this is my hook to an entry for the start of 2019?

Many thanks to Michael Barker of Sony Pictures Classics for help on this entry.

On the four-part structure of classical films see Kristin’s 2008 entry and my essay “Anatomy of the Action Picture.” Today’s entry deploys the analytical categories trotted out at length in this essay and more briefly in this discussion of The Wolf of Wall Street.

Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2.

Patchwork imagination: Lee Kwangkuk’s framed and frayed stories

Romance Joe (2011).

DB here:

Seeing Hong Sangsoo’s The Day a Pig Fell in the Well at the 1997 Hong Kong Film Festival didn’t convince me that he was a major talent. That happened two years later, when I saw The Power of Kangwon Province at the same event, and again at Cinédécouvertes in Brussels. At Hong Kong, and again at Brussels, I saw The Virgin Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors (2001). In those days, Hong made a movie every year or two, like your ordinary director.

I was impressed. I included Kangwon Province as an example of modern South Korean cinema in our second edition of Film History: An Introduction (published 2002), and it’s still there in our upcoming fourth edition. A year earlier, I had brought Hong to our Wisconsin Film Festival for what I think might have been his first retrospective–if three films count as a retrospective. And I drew on a scene from The Virgin as an example of subtle ensemble performance in Figures Traced in Light (2005). And I contributed an essay to Huh Moonyung’s anthology Hong Sangsoo (Kofic/Seoul Selection, 2007).

I was impressed. I included Kangwon Province as an example of modern South Korean cinema in our second edition of Film History: An Introduction (published 2002), and it’s still there in our upcoming fourth edition. A year earlier, I had brought Hong to our Wisconsin Film Festival for what I think might have been his first retrospective–if three films count as a retrospective. And I drew on a scene from The Virgin as an example of subtle ensemble performance in Figures Traced in Light (2005). And I contributed an essay to Huh Moonyung’s anthology Hong Sangsoo (Kofic/Seoul Selection, 2007).

My apologies for playing an egocentric cinephile game. Boasting aside, though, I want to express genuine satisfaction at Hong’s sustained creativity. He has become prolific but not stale; every film offers the viewer and the filmmaker himself fresh challenges. What attracts me is his simplicity of means and the way he devises narrative games that make satiric points (usually about male vanity) without seeming mannered or precious.

He has gotten ever-greater recognition, as evidenced by the current Film Comment cover story, Dan Sullivan’s perceptive appreciation of his three (!) 2017 releases. Even more startling is a real high-culture breakthrough. In its print editions over the years, The New York Review of Books has resolutely ignored Kiarostami, Kitano, Wong Kar-wai, and Hou Hsiao-hsien, to pick some exceptional directors who hit their strides in the 1990s. But the 7 December NYRB boasts Phillip Lopate’s wide-ranging essay introducing Hong to its readership.

So he’s one of those overnight successes who took twenty years. Moreover, it’s gratifying to see that recently this body of work has had some influence, most apparent for me in the work of Lee Kwangkuk. Today I want to offer some notes on an intriguing, quietly ambitious filmmaker working in the shadow of Hong.

Two shorts

Hard to Say.

Lee learned on the job, assisting on Hong’s Tale of Cinema (2005), Woman on the Beach (2006), Like You Know It All (2009), and Hahaha (2010). His films have the crystalline cinematography and color design of Hong’s, and he has learned how to make movies that consist largely of two-person dialogues, shot in long, poised takes punctuated at just the right moment by a close-up. He has cast several actors who have appeared in his mentor’s films.

As with Hong, Lee’s characters tend to be artists: filmmakers in Romance Joe (2011), actors in A Matter of Interpretation (2014), and novelists in A Tiger in Winter (2017). They have romantic liaisons, but they also spend inordinate stretches of time wandering streets, hanging out, and drinking immense amounts of soju. And like Hong, Lee has experimented with storytelling formats.

Most obviously, there are embedded stories. Early and late Hong explored a modular narrative, broken into two or three blocks, with story lines splitting or converging. At first blush, Lee developed this in a more traditional direction, inserting stories within stories, Russian-doll fashion. His two favored forms of this are the flashback and the dream.

We get both in the short Hard to Say (2012). In a playground, a young woman declares her love for a young man, who puts her off, suggesting he’s been attracted to another woman, a guitarist. “You can imagine all you want,” he says, but he’s not going to be her boyfriend.

Saddened, the woman finds a guitar abandoned in the woods, and starts to listen to it. Cut to the boy, who’s now searching for the singer who played a song he loves. (Are we in a flashback?) He finds the young woman of the first scene, but as a different character, a poised and meditative guitarist. She tells him, via a flashback, how her father forbade her to learn the guitar, so she learned to play it in her imagination, in shadow strums and plucks.

When she finally got an instrument, she found she could play it perfectly. After her tale ends, she asks him to hug her.

Abruptly we’re back on the playground, where the original young woman is waking up from sleep. Now the boy is interested in her and offers to walk her home. The guitarist’s claim for the power of imagination is vindicated.

The fact that we’re not sure where the girl’s dream begins is conventional, but also characteristic of the way that Lee frays the boundaries of his embedded stories. And the fact that the boy has fallen in love with the girl while in her dream shows the porousness of the subjective stretch that’s embedded. Hard to Say provides a miniature example of how Lee’s characteristic plot structure prompts us to see stories within stories, and then refuses to keep them sealed tight. Early in a film, we might be led to expect a solidly implanted flashback, but soon the whole frame is revealed as less objective than we might think.

The transforming power of the imagination is given a more somber treatment in another short, Soju and Ice Cream (2016). A young woman fruitlessly selling insurance policies meets an old woman who asks her to fetch some ice cream in exchange for a basket of soju bottles. In one bottle our heroine finds a slip of paper, a sort of reformation vow written by the woman: “Do not give up. Make a plan. Stop drinking. Keep smiling.” Suddenly, in what appears to be a flashback, we’re watching the old woman write the note, in an apartment tagged with Post-its. She gets a phone call from her landlord evicting her.

The old woman casually blows into a bottle she’s just drained and, as if by magic, the girl hears and feels the breath.

Now able to listen to the old lady’s phone call, she discovers that the woman’s daughter treats her as harshly as she has treated her own mother.

The girl bursts in on the old woman–in the past? in her mind?–and pours her resentment of her mother into a criticism of the old lady for taking loved ones for granted.

Back at the ice-cream stall, she snaps out of her reverie to discover that the bottles are gone and the old woman is long dead. This touch of the fantastic has given her the chance to empathize with her mother and, in a long coda, to implore her sister to heal the family wounds. Here imagination yields not wish fulfillment, as in Hard to Say, but the recovery of duty and devotion.

Dream on

A Matter of Interpretation.

A Matter of Interpretation tackles dream narratives on a bigger scale. Yeon-shin, an actress, stalks out of a brutally awful avant-garde play because, among other problems, there is no audience. As she wanders the city, she recalls breaking up with her boyfriend a year or so ago. Now, on another bench, Yeon-shin meets a detective who claims to be able to interpret dreams. So she tells her dream of attempting suicide in a car halted in a field of goldenrod.

But a thumping from the trunk interrupts her, and she finds a man tied and gagged there. He’s the detective who had asked her about the very dream he’s now in. In a flashback he explains he found himself in the car, contemplating suicide, before she arrived.

We’re left with a dream that contains a flashback, as in Hard to Say. But it’s not a veridical one, since the man finds the pill bottle empty and Yeon-shin finds it full. So it’s a dream within a dream? Moreover, her dream features a character whom the dreamer did not know…until she recounted the dream. We’re entitled to take what we see as a version of what Yeon-shin told the detective, I suppose, with him plugged into the role that some faceless man played in the original dream. Or maybe she’s just fibbing. Or maybe what we’re seeing is a free elaboration of the situation, a startling variant without any source in her mind. The uncertainty, of course, is the point.

In any case, the detective interprets Yeon-shin’s dream as being about her dumping her ex, with the recurring car symbolizing her career failure. And now he explains his skill as a dream interpreter through a flashback to his caring for his ill sister, and her recounting a dream about a customer.

As the film goes on, we get to meet Yeon-shin’s boyfriend, Woo-yeon, through a string of flashbacks framed by her telling. Later in the day, he winds up on the bench with the detective, who probes one of his dreams–in which, again, the car and the detective appear.

Back in reality, in a string of precise repetitions, Woo-yeon follows Yeon-shin’s wanderings through the streets. And that night, exhausted and depressed, she has another dream that brings Woo-yeon back into her life.

Like Hard to Say, A Matter of Interpretation offers some legible time shifts–conventional framing situations for flashbacks–in order to give the imaginary scenes escape hatches, as the detective slips into the dreams recounted by the lovers. By the end, we’ve been prepared for their paths to cross, not least because Yeon-shin’s final dream presents a reconciliation she seems to yearn for.

Telling it backwards and sideways

There aren’t any dreams per se in Romance Joe, but it’s no less committed to the zigzag contours of the imagination. The plot presents several different time schemes (although some may be fictitious), and they don’t stay neatly separate. Again, there’s a benevolent contamination of one zone by another.

A young filmmaker has disappeared. His parents come to his friend Dam Seo to investigate.

Again, what seems to be a tidy flashback shows Dam meeting with the son, who rants that he’s run out of stories.

In a standard film, we’d return to Dam Seo and the parents for more discussion. Instead we’re now in a village, where a third filmmaker, director Lee, is dumped by his producer and ordered to conjure up a story pronto. Lounging in the hotel, Lee is brought coffee by a waitress who admires one of his films, A Good Guy, for its “critical approach to narrative.” Pleased, Lee asks her to stay the night, and she agrees, for money. He reminds him, she says, of another director who visited the town, the man she calls Romance Joe.

Joe, it turns out, is the missing, unnamed director the parents are worried about; but it’s not at all clear that Dam Seo is narrating this encounter of Lee and Rei-ji. How could he know about them? His flashback simply bleeds into a new set of scenes with these other characters.

Rei-ji tells of Joe’s coming to town, and in flashback we see him wandering the streets, then checking into a hotel and trying to write. Despondent, he starts to slash his wrist. That scene is interrupted by a flashback to Joe as a teenager finding a young woman, Cho-hee, with slashed wrists in a forest. He takes her to the hospital. At this point, the flashback-within-a-flashback ends. Rei-ji, delivering coffee, finds the bleeding Joe and hurries away.

Here, about thirty minutes in, we finally return to the initial situation of Dam Seo talking to the parents about their missing son. The father is dismissive: “All these kids today wasting their lives on film.” But the mother is sympathetic to Dam Seo and asks about his work. He says he’s working on a story, and he tries it out on them. This launches what can only be called a hypothetical sequence, about a boy visiting a town in search of his missing mother. But soon enough the boy encounters Rei-ji, the coffee-girl/hooker.

And the boy’s tale frays further when it’s interrupted by a scene of Cho-hee in the forest, starting to slash her wrists and then being discovered by the teenage Joe. There’s crosstalk among what ought to be distinct realms–Dam Seo’s script versus Cho-hee’s reality, one speaker’s story versus another’s.

The rest of the film will intercut these story lines, with some peculiar interferences. Rei-ji tells Lee of meeting Joe, who says he has no more stories and is tired of them. But after spending the night with her he tells (or seems to tell) the story of himself as a teenager, and his love for Cho-hee. The stories intersect unexpectedly, with the vagabond boy revealed to be present when Rei-ji discovers Joe’s suicide attempt. Again, though, the boy is initially presented as purely fictitious, a character in Dam Seo’s uncompleted screenplay. A similar disconnected connection involves the name “Romance Joe.” It’s the nickname Rei-ji gives the anonymous director she meets, but much later in Cho-hee’s story, it’s the title of the film Joe as a student is making in Seoul. By canons of plausibility, Rei-ji could know nothing of this.

All this is hard to visualize in my prose, but I think you can see how the firm outlines of flashback episodes or embedded tales become hazy. By the end, two filmmakers want to film this tangled tale. Director Lee sees that it could become a thriller. Joe, encouraged to tell his own story by Rei-ji, seems to be rejuvenated and wants to revisit the forest of his childhood. Yet it’s not clear that either will make the movie–especially after we hear Rei-ji confide to another waitress that you just have to tell your clients what they want to hear. (So is her story about Romance Joe’s writer’s block calculated to mend Lee’s own?) The film’s final image, harking back to an Alice in Wonderland motif, suggests that the whole patchwork of stories might be pure fabulation.

Far from being a simple imitator of Hong, Lee has taken some of his experiments in fresh directions. Some of these involve abstract form, others style; his shots tend to be prettier, and he’s more likely to break a scene into reverse angles. Other differences lie in the emotional tint of the film. Hong’s films are usually comedies, however mordant. Lee’s films have a grimmer tone. Although Hard to Say is light-hearted, Soju and Ice Cream, revealing family breakup, job insecurity, and alcoholism, modulates into tearful frustration. The comic suicide attempts of A Matter of Interpretation are balanced by the melancholy prospect of aborted artistic careers and disrupted love affairs. When Jeon-shin sees the detective again in the final stretches of the film, he ignores her; their momentary friendship is over.

Romance Joe offers something grimmer than Hong’s comedy of bad manners. At the core of the story action is the sad tale of Cho-hee, scorned by her classmates, oppressed by her parents, and desperate to flee town. After her wrist-cutting episode, she and the young Joe flee to Seoul for a night, but in confusion he abandons her. She too returns home, only to leave again when she becomes pregnant (by whom?). She becomes a Seoul prostitute. Through a chance meeting Cho-hee finds that her life has become a source for Joe’s student film. She seems cheered by this, but we never see her fully grown. Joe must confront not only his feeble career but his long-ago failure to honor his promise to Cho-hee: “I’ll always protect you.” Like her and Rei-ji he bears the stigmata of a botched suicide.

This somber tone has wholly taken over Lee’s recent A Tiger in Winter. Thoroughly linear in construction, with no embedded tales, it probes an unhappy couple: a failed novelist living on the margins and his alcoholic former girlfriend, who’s found success but now suffers writer’s block. It’s a chronicle of yuppie pathos and pain in chilly urban landscapes, where we find anomie and temps morts and, again, suicide.

“In Romance Joe,” Lee remarks, “I was focused on someone that was committing suicide because they didn’t have a story any more, and in A Matter of Interpretation she didn’t have an audience any more.” In A Tiger in Winter, the characters have run out of stories and audiences. Clearly, for Hong, your prospects are bleak when you can’t summon up the redeeming power of imagination.

Thanks to Lee Kwangkuk and Tony Rayns for help in preparing this entry. Romance Joe was once available on South Korean DVD, but apparently no longer. The only Lee Kwangkuk film currently on video, as far as I know, is Soju and Ice Cream, part of an omnibus film for the Korean Human Rights Commission. Lee’s oeuvre is a real opportunity for an ambitious streaming service.

My quotation from Lee comes from an easternkicks interview. Our entries on Hong Sangsoo are here. One of them is a 2012 first impression of Romance Joe. On embedded stories in general, there’s this.

Hard to Say (2012).

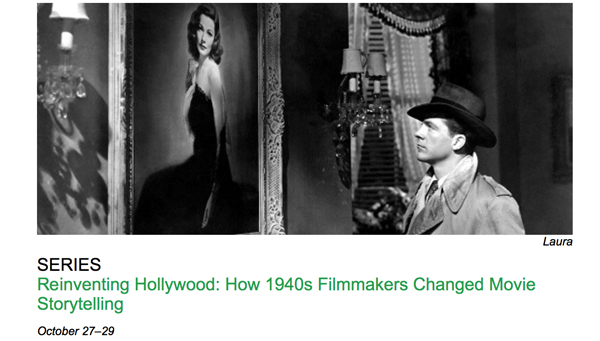

REINVENTING HOLLYWOOD comes to Astoria

DB here:

Next weekend Astoria’s wonderful Museum of the Moving Image is sponsoring a series of films keyed to my book Reinventing Hollywood. The program consists of Laura on Friday, A Letter to Three Wives and Unfaithfully Yours on Saturday, and Our Town and Portrait of Jennie on Sunday. Here’s the schedule.

I’ll be giving a talk before Three Wives and will hang around for conversation and book-signing afterward. If you’re in the vicinity, why not come by? Note: Four of the five screenings command 35mm prints! If you’ve only seen Our Town in the horrendous public-domain video versions, you’re in for a treat, because it looks (and sounds) superb in 35. Then again, there’s that tidal-wave ending to Portrait of Jennie, a force of nature on the big screen.

Looking better than when he made it?

Beyond Glory (1948). Production still.

Actually, this entire clutch of classics is pretty fair sampling of the audacity of the period, an age when narrative delirium was welcomed. Of course a lot of A pictures were stodgy, but there were an unusual number of both popular hits and less-successful items that are engagingly experimental.

The book, as Tony Rayns remarked in his Sight & Sound review, ventures beyond the classics. I cover all the films in the MoMI program, but a lot of space is devoted to minor movies too, a fair number of B films and plenty of “nervous A’s.” Those nervous A’s–films trying to get by on less-known stars, unfamiliar source material, or just a strange premise–provided me with lots of examples.

A friend who likes Reinventing Hollywood said that it was too bad I had to spend so much time on obscure and second-rate movies. It’s true that in viewing I slogged through quite a few dogs. Most weren’t illuminating, but some were, and I slid them into the manuscript, even if the reader was unlikely to have heard of them.

But two factors pop up here. First, I wanted to show just how pervasive the newly popular storytelling techniques were. That meant considering items outside the canon. When you think of complicated flashback films, you don’t think of Beyond Glory (1948) and Backfire (1949), though they may be the most intricate time-shuffling movies of the period. If you arrange the past-time events in the order we see them, Beyond Glory gives us 10-9-8-1-4-3-5-6-7-2. In Backfire, the order of presentation is 3-5-2-4-1-6-7.

These show a very 40s development: By then, such time schemes were becoming commonplace. Moreover, the fact that these two films come at the end of the decade is itself of interest. Was there a kind of arms race to tell stories in ever more elaborate ways?

Looking at the less-known items can also yield a sense of the limits of innovation. Sometimes these movies went too far. One critic noted of Beyond Glory that it “moved slowly and confusingly through a great many flashbacks.” As for Backfire, even the director Vincent Sherman had qualms:

That picture had an involved story, with flashback-within-flashback, and I hated it. The interesting thing is that not long ago I saw the film, and it looked better than when I made it.

Sherman’s last remark is indeed interesting. Today, after the really fragmentary flashback constructions we find in films from the 1990s onward, films like these (and The Locket and Passage to Marseille) don’t look as ornery. Any day now you may hear from a Tarantino fan that Backfire is a masterpiece.

More broadly there’s an issue of method, and it’s controversial. I suspended matters of quality to an unusual degree. Of course the book talks a lot about bona fide classics. I praise films by Preminger, Ford, Hitchcock, Welles, Mankiewicz, Sturges, et al. But I stubbornly persist in believing that we can best understand their accomplishments in the context of the broader burst of storytelling strategies that swept through the 1940s.

True, great writers and directors provided some of the energy for that burst, but they didn’t work alone. I think, for instance, we appreciate It’s a Wonderful Life better if we know about conventions of voice-over narration, angelic intervention, and flashback construction that had already crystallized when Capra and his screenwriters gave them a new spin.

A lot of researchers suspend questions of value in order to bring to light other factors. Scholars studying gender, race, and ethnicity consider films of all levels of quality representing women or African Americans or Jewish culture. Students of genre often find that lesser-known Westerns or musicals shed light on certain conventions. Even failures can be instructive.

Reinventing Hollywood pursues a similar method but on an area of creativity less commonly considered: narrative. The book tries to trace both common and offbeat strategies of plot construction and narration–at a period when innovation in those domains was rewarded. In some instances, we get striking innovations more or less by accident.

In sum, I was more interested in reconstructing the major and minor storytelling options of the period than in picking out masterpieces. Going into the kitchen to watch the menu being devised, you might say, rather than savoring a few consummate meals. That meant bulk viewing, which yielded a bulky book (but a good bargain at the price).

Some day it would be fun to mount a series of intriguing second-tier items I ran into. They’ll never be classics, but they do shed light on my research questions. Apart from completists, there are fans who would enjoy seeing things that are elusive on video and never make it to repertory screens or archive retrospectives. The problem then, as for me, was finding prints….

Thanks to David Schwartz and his colleagues for arranging this event at MoMI.

Backfire (1949).

REINVENTING HOLLYWOOD: Out of the past

Cover Girl (1944).

DB here:

I just got my first copy of Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling. I’m always scared to look at a published piece because I expect my eye to light on (a) a misprint; or (b) a sentence of unusual clumsiness or simplemindedness. Other writers have told me they have similar qualms. But I did look, and on this fat volume: so far, so good. It even has black, slightly corrugated endpapers, like the paper inside a box of chocolates.

This was a personal project for me, for reasons I’ve sketched elsewhere on this site. I grew up watching 1940s films on TV and have always had a fondness for what James Naremore has called “the beating heart of Hollywood.” In my teen years, watching Welles and Hitchcock movies along with B films and minor musicals fed my interest in studio cinema.

When I started teaching in the 1970s, I was keen to catch up with all those nifty movies sitting comfortably in our Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research. My classes screened His Girl Friday (in a pirate copy) and Meet Me in St. Louis and Possessed and The Locket and White Heat and The Ministry of Fear and many more. Students working with me studied Gothics, war films, and I Remember Mama. It was then I started to realize just how creative this period was.

One piece of boilerplate for the book puts it more melodramatically.

In the 1940s American movies changed. Flashbacks began to be used in outrageous, unpredictable ways. Viewers were plunged into characters’ memories, dreams, and hallucinations. Some films didn’t have protagonists. Others centered on anti-heroes or psychopaths. Women might be on the verge of madness, and neurotic heroes were lurching into violent confrontations.

Films were exploring parallel universes and supernatural dimensions. Characters switched bodies or intuited the future. Combining many of these ingredients, there emerged a new genre—the psychological thriller, populated by murderous spouses and witnesses who became targets of violence.

If this sounds like our cinema of today, that’s because it is. In Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling, David Bordwell examines for the first time the range and depth of the 1940s trends. Those trends crystallized into traditions. The Christopher Nolans and Quentin Tarantinos of today owe an immense debt to the dynamic, occasionally delirious narrative experiments of the 1940s.

Bordwell shows that the booming movie market at the start of the Forties allowed ambitious writers and directors to push narrative boundaries. He traces how Orson Welles, Preston Sturges, Alfred Hitchcock, Otto Preminger, and dozens of lesser-known creators built models of intricate plotting and psychological complexity.

Those experiments are usually credited to the influence of Citizen Kane, but Bordwell shows that the experimental impulse had begun in the late 1930s, in radio, fiction, and theatre before migrating to cinema. And even with the late 1940s recession in the industry, the momentum for innovation could not be stopped. Some of the boldest films of the era came in the late forties and early fifties, when filmmakers sought to outdo their peers.

Through in-depth analysis of films both famous and virtually unknown, from Our Town and All About Eve to Swell Guy and The Guilt of Janet Ames, Bordwell analyzes the era’s unique ambitious and its legacy for future filmmakers.

Today I’d like to give you some background on the book and flag a new page on this site you might find of interest. (If you can’t wait, you have permission to go there now.)

Questions, questions

Kitty Foyle (1940).

Reinventing Hollywood turned my enthusiasm for the 1940s into a set of questions.

The enthusiasm was based on a hunch that Hollywood cinema between 1939 and 1952 saw a burst of innovative storytelling. The innovations weren’t utterly new, but they differed from what was seen in the 1930s by virtue of their range, number, and complexity. The more I looked, the more I realized that the Forties recaptured the narrative range and fluidity of silent cinema, extending and nuancing it with sound. In essence, a new set of norms emerged, forged by many filmmakers.

Several questions followed. How to describe those innovations? How to chart their range and variations? How to analyze their effects—on the sort of stories told, on how viewers understood them? How did the innovations alter genres, or create new ones? How might we explain the rise and expansion of these new norms? And finally, what sort of legacy did this process of changing conventions leave to the filmmakers that followed? In all, how did various trends coalesce into a tradition?

This plan, ridiculously ambitious, at least has the virtue of originality. Most books about the 1940s concentrate on major figures—stars, producers, directors, the Hollywood Ten. Other books explain how studios or censorship or labor disputes worked. Others focus on genres such as the musical or the melodrama or the combat film. A popular option is devoted to that not-quite-a-genre film noir. These are all worthy subjects. And there’s no shortage of books seeing 40s film as a reflection of wartime or postwar America, or the geopolitics of the Cold War.

Studying narrative norms cuts across many of these common perspectives. Individuals matter, particularly ambitious screenwriters, producers, and directors striving to tell stories in unusual ways. But institutions matter too, as studio culture and writers’ associations prized a degree of originality in plotting or point of view. And narrative devices cut across genres to a considerable degree. Although flashbacks have come to be associated with film noir, they actually appear in all genres, and take on different roles accordingly.

So, 621 films later, my project has become an effort to contribute to a history of film form—the various storytelling methods that filmmakers have developed in different times and places. (In other words, a poetics of cinema.) In effect, I’m asking that the kind of appreciation people show for genres, actors, and auteurs be stretched to narrative strategies as well.

Darryl F. Zanuck, with his shrewd narrative instinct, gave me my epigraph.

It is not enough just to tell an interesting story. Half the battle depends on how you tell the story. As a matter of fact, the most important half depends on how you tell the story.

The book in between

Daisy Kenyon (1947).

The project blended in with earlier work I’d done, particularly in The Classical Hollywood Cinema and The Way Hollywood Tells It. In a sense, Reinventing Hollywood is a bridge between those two books.

CHC, written with Kristin and Janet Staiger, traced continuity and change in the studio storytelling tradition from its inception to 1960. It analyzed how conventions of story, style, and work practices were established and maintained over the decades. The Way Hollywood Tells It suggested that after 1960, the broad conventions remained in place but were modified in particular ways.

In passing, I suggested that innovations of “contemporary Hollywood” owed a lot to experiments launched in the 1940s. The new book tries to pay off that IOU. Reinventing Hollywood asks how, within the broad conventions of classical Hollywood, particular innovations could emerge in the boom-and-bust 1940s. Many standard devices of our films today, from voice-over and fragmentary flashbacks to block construction and tricks with point of view, can be traced back to the Forties, when they were consolidated and refined.

The two earlier books also considered film technique—staging, shooting, editing, and the like. Reinventing Hollywood doesn’t tackle visual style, for two reasons. It would have doubled the book’s length, and I’ve said my say on 40s style in other work. Style shapes story, of course, and I’ve tried to take this factor into account. But I concentrate on the principles of story world, plot construction, and narration—the three dimensions of narrative I’ve outlined elsewhere.

None of these books is auteurist in basic orientation, but they aren’t anti-auteurist either. Surveying techniques in a systematic way helps call attention to adepts, middling talents, and innovators. In Reinventing, I think the interludes on Mankiewicz, Sturges, Welles, and Hitchcock show how skillful filmmakers mobilized emerging conventions in powerful ways. In effect, we reconstruct a menu of options to sense the values in picking and mixing them. For example, Citizen Kane‘s investigation plot, adorned with a dying message and a bevy of flashbacks, was a vigorous synthesis of devices that were circulating through film and other media in the late 1930s. The boldness of the effort made it influential on what followed. We get a better sense of directors’ (and writers’ and producers’) idiosyncratic strengths when we know the norms they’re working with, and sometimes against.

Reinventing Hollywood, running nearly 600 pages, makes The Rhapsodes look scrawny. But it isn’t the behemoth that CHC is. CHC could give this book noogies.

The big and the small

The Bishop’s Wife (1947).

It was hard to discuss broad trends and still probe particular cases in detail. So the chapters move from generalities to specifics in steps. Some films are merely mentioned, others described briefly, others considered at greater length, and some analyzed in depth. After a conceptual introduction and a historical panorama of Hollywood as a creative community (Chapter 1), there are chapters on flashbacks, plot construction, woven versus chaptered plots, manipulation of viewpoint, voice-over, character subjectivity, psychoanalytic plots, realism and fantasy, mystery plots, and self-conscious artifice. The conclusion looks at the impact of the period on later filmmakers.

I try to go beyond obvious observations to study the mechanics of familiar devices. So I come up with terms and concepts to pick out finer-grained tactics: the breadcrumb trail that sets up many flashbacks, block construction, hooks, switcheroos, and the like.

The chapters on particular techniques are broken by “interludes” devoted to particular movies or moviemakers. Some of these interludes involve well-known films and figures, but others look at obscure items. (Yes, The Chase is involved.) Even the treatment of Big Names tries to offer something original, as when I argue that Hitchcock and Welles pushed 40s innovations very far and sustained them throughout their later careers.

Here’s the table of contents, with small annotations

Introduction: The Way Hollywood Told It

Chapter 1: The Frenzy of Five Fat Years (Hollywood as an ecosystem)

Interlude: Spring 1940: Lessons from Our Town

Chapter 2: Time and Time Again (flashbacks)

Interlude: Kitty and Lydia, Julia and Nancy

Chapter 3: Plots: The Menu (conventions of plot structure)

Interlude: Schema and Revision, between Rounds

Chapter 4: Slices, Strands, and Chunks (alternative structural options)

Interlude: Mankiewicz: Modularity and Polyphony

Chapter 5: What They Didn’t Know Was (managing narrative information)

Interlude: Identity Thieves and Tangled Networks

Chapter 6: Voices out of the Dark (voice-over)

Interlude: Remaking Middlebrow Modernism

Chapter 7: Into the Depths (subjectivity)

Chapter 8: Call It Psychology (psychoanalytic films)

Interlude: Innovation by Misadventure

Chapter 9: From the Naked City to Bedford Falls (realism, fantasy, and in-between)

Chapter 10: I Love a Mystery (thrillers and mystery-based plotting)

Interlude: Sturges, or Showing the Puppet Strings

Chapter 11: Artifice in Excelsis (self-conscious display of conventions)

Interlude: Hitchcock and Welles: The Lessons of the Masters

Conclusion: The Way Hollywood Keeps Telling It (legacy of the 1940s)

To keep things specific, I’ve prepared eleven film clips keyed to particular analyses. Just playing the clips might give you a sense of the book’s range. They’re also fun in their own right.

No zeitgeists, please

Blues in the Night (1941).

Two last points. One bears on preferred explanations. How do we explain why cinematic innovation burst out at this particular time? Again, the book tries to pursue an uncommon path.

Many writers look to a zeitgeist—the anxieties of war, the anxieties of postwar adjustment, the anxieties of the anti-Communist crusade, any anxiety you can imagine. Instead I try to look for institutional factors shaping the films’ norms. Centrally, there are the conditions of the film industry, with its rich interplay of personnel and story materials shuttling all over the place. There are also the cinematic traditions themselves, such as plots depending on amnesia. Particularly important are the adjacent arts, including theatre, radio, and popular fiction. All these sources get modified by a process of schema and revision—borrowing something already out there but warping it to new ends. In short, instead of looking for remote causes in the broader society, I try to locate more proximate ones within the filmmaking community and the turmoil of popular culture.

Someone might argue that this just pushes the problem back a step. Don’t social anxieties surface in all these media? To this I’d argue, as I did here and here, that those anxieties are very hard to identify. Not all anxieties or concerns will be shared by a populace (viz. our current political situation). And we can’t establish a strong causal connection between them and the products of popular media—especially since media are indeed mediated, by tastemakers, gatekeepers, and the institutions that produce popular culture.

For the period I’m concerned with, James Agee noted the role of mediators in his complaints aimed at the film-as-dream sociologists of the period:

It seems a grave mistake to take [movies] as evidence as definitive, as from-the-public, as if 40 million people had actually dreamed them. Take the far simpler case of advertising art. The American family, as shown therein, is not only not The Family; it isn’t even what the American people imagines as The family. It is A’s guess at that, subject to the guesswork of his boss, which is subject in turn to the guesswork of the client. At best, a queer, interesting, possible approximation, but certainly never definitive. In movies many more people take part in the guesswork, but not enough to represent a population: and many more accidents and irrelevant rules and laws deflect and distort the image.

A movie does not grow out of The People; it is imposed on the people— as careful as possible a guess as to what they want. Moreover, the relative popularity or failure of a picture, though it means something, does not at all necessarily mean it has made a dream come true. It means, usually, just that something has been successfully imposed.

Instead of social reflection, we should expect refraction. Decision-makers opportunistically grab memes and commonplaces (the unhappy housewife, the juvenile delinquent, the returning vet) in hopes they can make something appealing out of them. They absorb those into familiar (narrative) forms. We get, then, not a “vertical” or top-down flow of social anxieties into artworks, but a “horizontal” ecosystem, a dynamic of exchange and transformation. The creators copy one another, obeying local norms while also resetting boundaries. This process includes selective assimilation of ideas thrown up by the culture, and it gets amplified by network effects, as sticky ideas themselves get copied. In other words, ideology doesn’t turn on the camera. The final film is always mediated by humans working in institutions, and both the people and the institution have many agendas.

A second point follows. Working on this book brought home to me how much film owes to other media. In a way, Forties cinema became more “novelistic” because it sought to assimilate techniques of split viewpoints, replays, inner monologue, and subjective response characteristic not so much of modernism (those were old hat by the 1940s) but of popular fiction and what we might call “middlebrow modernism.” A Letter to Three Wives (1948) attaches itself in turn to three women, each with memories of the past, with that trio interrupted by a never-seen fourth woman mockingly narrating the tale. It’s a cinematic treatment of the shifting viewpoints and personified narrative voices to be found in the nineteenth-century novel (Dickens, Collins, James) and later in genre fiction, not least in mystery tales. (It’s also a modification of the source novel.)

But you could also argue, as André Bazin did, that the 1940s saw a new “theatricalization” of cinema, with self-conscious adaptations that stressed stage conventions like the single-setting action. And of course radio supplied important prototypes for acoustic texture and first-person voice-over. Each of these devices wasn’t simply ported over to film; moving images and recorded sound gave literary, theatrical, and radio-based techniques new expressive possibilities. And all depended on the churn of people working side by side to innovate within familiar norms.

Every author discovers or remembers too late those things that should have been mentioned. Doug Holm reminded me of the dream narrative of Sh! The Octopus (1937). Jim Naremore pointed out that Rex Stout had already done my work for me in Too Many Women (1947, year of my birth), when Archie reports, “It was a wonderful movie . . . Only two people in it have amnesia.” On a different pathway, I’d love to do more research on moguls’ screening rooms as a condition of influence. (They could borrow films from rival studios without charge.) Julien Duvivier is a minor hero of my book, but only after the book was submitted did I see his L’Affaire Maurizius (1954), a perfect extension of 1940s storytelling to a French milieu.

And just recently I found a nice confirmation of the unexpected byways of the ecosystem. According to the author, the figure of the “psycho-neurotic” returning soldier was at first mandated by government policy but then twisted by ambitious screenwriters into tales of civilian madmen. The article has the enviable title: “That Psycho Story Swing Is No Cycle; It’s Now an Obsession.” If you buy the book, please write that into the endnotes.

And for the third time, feel free to visit the clips page!

I owe a lot to several people who saw this book through publication. Foremost are my editor at the University of Chicago Press, Rodney Powell, and his colleagues Melinda Kennedy and Kelly Finefrock-Creed. Then too there is Bob Davis, who supplied the book’s jacket photograph; Kait Fyfe, who prepared the clips for posting; and web tsarina Meg Hamel who set up the clips page. My other debts are recorded in the acknowledgments, but of course I must mention Kristin who had the hardest job of all. She had to put up with the author.

My Agee quotation comes from “Notes on Movies and Reviewing to Jean Kintner for Museum of Modern Art Round Table (1949),” in James Agee, Complete Film Criticism: Reviews, Essays, and Manuscripts, ed. Charles Maland (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2017), 975. I’m indebted to Chuck for sharing this with me. Chuck’s discussion of Agee on our site is well worth a read.

Many entries on this site are dedicated to 1940s Hollywood. See the relevant category. “Murder Culture” has been revised as a chapter in the book. On 1940s visual style, see Chapter 27 of The Classical Hollywood Cinema, Chapter 6 of On the History of Film Style, and entries under 1940s Hollywood. There’s also the web essay on William Cameron Menzies. My most detailed arguments against social reflection and zeitgeists in historical explanations comes in the title essay in Poetics of Cinema, pp. 30-32.

Although the Amazon page offering Reinventing Hollywood says copies aren’t available until October, it seems that copies are shipping now from Chicago’s webpage. Amazon offers no discount on the title. (See P.S.) It’s currently available only in hardcover, with a paperback planned for the distant future.

P.S. 27 Sept 2017: Actually, Amazon is now discounting Reinventing Hollywood; it’s $30.77, as opposed to the $40 list price.

P.P.S. 13 October: Amazon’s prices on the thing have been fluctuating wildly. See this entry. Those wild and crazy algorithms!

Our Town (1940).