Archive for the 'Narrative strategies' Category

Un-Marry me a little: MARRIAGE STORY and LITTLE WOMEN

Little Women (2019).

DB here:

For a while The Blog conducted an annual ritual of analyzing storytelling techniques in year-end releases. I wrote entries from early in 2016, in 2017, and in 2018. Last year I muffed it, largely because of time spent revising our Christopher Nolan book. (Yes, we’re also looking forward to Tenet, especially after that hellah trailer.)

This time I’m trying an alternative. Instead of surveying a range of releases, I’ll focus on two that I think encapsulate some robust variants on familiar narrative strategies. Those strategies include choice of protagonist, linearity versus nonlinearity in time, and manipulation of viewpoint. While I’m concentrating on Marriage Story and Little Women, I’ll draw out some comparisons with other films.

Many spoilers follow, but of course you’ve probably seen all the new films. Except maybe Cats.

Protagonists, dual and dueling

Human nature is not given to a protagonist/antagonist three-act structure. Human nature is just one damn thing after another in which the only thing that matters is what went on today because yesterday is gone. And that is contrary to a lot of the business that we’re in, which makes sure that everybody understands the story by page 30 and is involved in the conflict.

You’re plotting a film. What sort of options do you face? A basic choice involves protagonists.

You might build the film around one character who pursues a cluster of goals. Examples this season would include Dark Waters, Motherless Brooklyn, Uncut Gems, and Harriet. The protagonist can have helpers, and will certainly have adversaries, but her or his initiatives, decisions, and responses propel the action. In addition, we’re usually attached to the protagonist’s point of view, which limits us to what she or he knows. Judicious widening of the horizon often takes place to enhance tension. In Uncut Gems we’re briefly attached to Arno’s thugs when they’re tailing Howard, and the climax crosscuts Howard in his office with Julia placing his big bet.

You could center the action on two characters, giving us a dual-protagonist plot. Here the goals may be shared or at least compatible. In The Aeronauts, a lady balloonist and a male meteorologist cooperate, with frictions, to break ascension records, while Ford v. Ferrari unites two men working together to win at Le Mans.

More rarely, a dual-protagonist plot can shift the protagonist in the course of the action. Good examples are Red River (1948) and The Killers (1946). I’d argue that Don Corleone functions as protagonist in the early sections of The Godfather (1972), while Michael takes up that role later. Similarly, Waves initially concentrates on Tyler, but he largely drops out of the plot and his sister Emily drives the film’s second half.

Alternatively, the plot can present two protagonists in competition. This season we’ve had The Current War, centering on the struggle between Edison and Morgan to transmit electrical power. The narrational weight is largely with Edison, but I think Morgan is characterized enough and we’re attached to his viewpoint frequently enough to present a counterweight. Morgan isn’t simply an antagonist but rather what Kristin calls a parallel protagonist, like Salieri in Amadeus or Captain Ramius in The Hunt for Red October. As these examples indicate, parallel protagonists, although they’re trying to figure out each one’s aims and stratagems, often become fascinated with each other and recognize their affinities.

Paired protagonists are common in romantic comedies, which often consist of friction between the couple (due to clashing goals) but end in harmony and union. What’s striking about Marriage Story is that here the end, not the start, of a romantic alliance is treated through the dual-protagonist strategy. Charlie and Nicole struggle over the terms of their divorce, particularly the handling of custody of their son Henry. Unlike Kramer vs. Kramer (1979), which is organized chiefly around the husband’s viewpoint, this gives weight to both spouses.

Director Noah Baumbach achieves this balance through a cunning parallel block construction. The film opens with two montages of roughly equal running time. One surveys Nicole’s habits and accomplishments with Charlie’s voice-over praising her. (“She’s my favorite actress.”) Then we get a montage illustrating what Nicole loves about Charlie, with other incidents stitched together by her voice-over. Both montages weave in scenes of Nicole in rehearsal while Charlie, the director, makes suggestions.

Baumbach has compared these montages to an overture in musical theatre. The film’s score sets out themes associated with each protagonist, and the quirks and routines that rush by establish important motifs, like haircutting, Monopoly games, and Henry’s urge to sleep with his parents. With the he said/she said duality, the montages prepare us for the film’s strategy of parallelism, a compare-and-contrast attitude.

The montages are revealed as visualizations of two memoirs the couple have written for a mediator.

They’re planning to divorce, and he’s asked them to recall what they loved about each other. Charlie is willing to share his notes with Nicole, but Nicole won’t show hers. This hints that he’s more reluctant to separate than she is, planting a question about why she seems determined to pursue the divorce.

Just as important, we’ve been given privileged access to both characters’ minds, and this sort of alternating omniscience will proceed throughout the film. There won’t be any more plunges this deep into subjectivity, but we’ll always know more than either does, because after they separate we’ll be attached to one or the other in large stretches.

For a time, though, we’re with both. In the mediator’s office, and then during the play’s performance, in the bar with the troupe after the show, and in the family apartment, they interact as a couple. (True, Charlie sleeps on the sofa.) But once Nicole moves to California, the first block of action ends and we are attached to her and Henry as she launches her new project, a TV pilot.

Not until Charlie comes to visit Nicole, her mother, and her sister does the narration bring him back. There he’s officially served the divorce papers. This scene launches a discreet viewpoint pivot from her to him. The family cuddle ends when Henry banishes Charlie from bed, foreshadowing how marginal his father will be to him from now on.

The film’s next block attaches us to Charlie as he seeks out a lawyer, takes Henry on outings, and clashes with Nicole about how to celebrate Halloween. The couple wind up giving Henry two trick-or-treating trips, in different costumes, which reiterates the duplex structure of action we’ve been presented with since the start.

The alternation between Nicole and Charlie’s viewpoints quickens as their negotiations get more fraught. Their first legal meeting ends with Charlie’s losing faith in his easygoing attorney. The next meeting is an escalating confrontation between Charlie’s new hard-charging lawyer and Nicole’s equally tough Nora. In the courtroom exchange, the he said/she said pattern becomes vicious as each lawyer weaponizes minor incidents from scenes we’ve seen to cast shame on the opposing side.

The nastiness of the custody battle comes to a crisis in a ten-minute duologue in Charlie’s apartment, an all-out fight between Nicole and Charlie. They run through a repertoire of reactions, from assurance of mutual admiration to declarations of annoyance, unhappiness, frustration, and complaints. By the end they’re screaming insults. Charlie rages and then, as if aware of how monstrous he’s being, collapses sobbing at Nicole’s feet.

Most classically constructed films follow the pattern Kristin identified back when. The plot consists of a setup, a complicating action redefining the setup, a development section consisting largely of delay and backstory, and a climax that resolves the situation. An epilogue asserts a stable, if changed state of affairs. The four main parts are roughly equal in running time, with the climax tending to be a bit shorter and the epilogue being only a few minutes.

Up to a point, Marriage Story conforms to this architecture. The first thirty minutes set up the split in the family before focusing on Nicole’s new life in California. Both Charlie and Nicole had hoped to separate amicably, with no need for lawyers. But thirty minutes in Nicole hires Nora and sets in motion a more severe legal battle than the couple had expected. The complicating action is triggered by serving Charlie the divorce papers.

There’s no turning back, and the new situation centers on figuring out how to handle access to Henry. Charlie wants Henry to spend time in New York (“We’re a New York family”) but Nicole wants him with her, and as he was born in California the law inclines to her side. Hence the triple thrust of the Charlie block: visiting lawyers, trying to keep his Broadway production on track, and winning some loyalty from Henry.

The development section consists of characterizing stretches (Nicole indulges in a quick sexual encounter) and delays: the unsatisfactory first lawyer session, a power outage at Nicole’s house, and the courtroom showdown. What happens next, though, seems to me quite original.

Between theatre and TV

To determine custody, both Nicole and Charlie must let an evaluator visit to observe each one’s treatment of Henry. In a more ordinary film, this stretch would initiate the climax. The visit from the evaluator would furnish a deadline for determining how custody would be handled. Then the film’s peak could be the vicious, trembling argument between Charlie and Nicole. This would be the explosion that reveals both their love and the impossibility of their staying together.

From this angle, Charlie’s guilt-ridden collapse would be the resolution–his realization of how he stunted Nicole’s life. A courtroom finale settling the terms of custody (a little more for Nicole than Charlie) would fill out the climax and lead to an epilogue, perhaps on the courthouse steps.

Excuse me for rewriting the film. I do it to show that Baumbach’s script does something daring. The big argument comes before the evaluator’s testing. After that brutal clash, we see Nicole rehearsing her answers in Nora’s office. Moreover, the blundering efforts of Charlie to convince the stiff evaluator he’s a good father play out in a lengthy comic scene with some gory sight gags.

A certain amount of suspense remains, I think, but the final cascade of gags works against the emotional pitch of the couple’s quarrel. Baumbach has, in effect, risked using an anticlimax to round out the normal climax section of the film. It also serves as a good-natured punishment for Charlie’s self-centeredness.

The same daring informs an unusually lengthy epilogue. It’s built out of the sort of modules we’ve seen already. Nicole and her friends and family celebrate her divorce with a party, while Charlie mopes around Manhattan and morosely salutes his play’s closing with his troupe in a bar. We might stop there, but Baumbach again does something original (though highly motivated). Charlie, now relocated for a teaching gig in LA, comes to pick up Henry and discovers the boy reading the note about Charlie that Nicole had prepared for the mediator session.

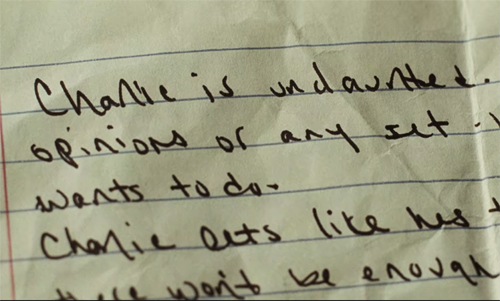

Not only does it reveal the feelings she had suppressed during the session, but the fact that she kept it shows she still harbors affection for that part of her life. Other films surprise us in the epilogue (Citizen Kane, for instance), but Baumbach’s use of the memoir in the film’s final moments remains a pretty bold, and moving, choice. This stretched and packed epilogue shows Charlie how much Nicole loved him, while also suggesting things that contributed to stifling her. Lines like “He’s very competitive” and “He loves being a dad” have a new impact now that we’ve seen his battle for his son.

In telling this story, Baumbach exploits a larger strategy of what theatre people call continuous exposition. Instead of giving the necessary backstory in a lump at the beginning or middle, major information is sprinkled through the ongoing plot. We’re familiar with this device in films that trigger fragmentary flashbacks, filling in backstory bit by bit. Baumbach goes with a more “theatrical” strategy using dialogue to invoke things that happened before the first scenes..

One of the major instances involves Nicole, who breaks down in an embrace with Nora, sobbing that Charlie slept with his assistant. Coming half an hour into the movie, it explains Nicole’s bitterness in the mediation session, as well as her larger reappraisal of her life with Charlie. At other points we learn of big events, like Nicole’s show taking off and Charlie’s long-term settling in LA, in casual conversation, not in extended scenes.

Crucially, in their climactic quarrel, Charlie justifies his affair by accusing Nicole of withholding sex for a year. We can’t appraise the truth of this, but it at least fills in a motive that more conventional exposition would have put into the setup. Resisting the temptation to supply flashbacks for all these revelations, Baumbach trusts our memory. That way the new data can color our ongoing understanding of the characters. The opening montages were generous but one-sided, chunks of incomplete exposition that suppressed important motives and behavior.

Continuous exposition is associated with Ibsen and playwrights who followed, but the theatrical patron hovering over the film is Stephen Sondheim. Greta Gerwig’s Lady Bird had used Sondheim as a touchstone for ambitious high-school players, but the parallel structure of Marriage Story makes more explicit references, this time to Sondheim’s Company. Nicole’s party features her and her mother and sister performing “You Could Drive a Person Crazy,” a saucy song about dumping a weak man. Soon in the bar Charlie is singing the yearning “Being Alive.”

Maybe a little on the nose (like the movie’s title), these citations seem true to the tastes of these show-biz mavens, while suggesting that at least some of Manhattan clings to Nicole in her exile.

Another parallel reminds us of a perennial Hollywood motif. Nicole began her career in a raunchy teen movie but thanks to Charlie’s stage shows she became a respected performer. Yet to establish her own identity more fully she agrees to shoot a TV pilot. Marriage Story positions itself between theatre (a little pretentious, but nobly struggling) and TV (dumb and superficial, but high-tech and well-financed). Worse, TV literally defaces Nicole.

Theatre, TV: what about film?

In this story about show-biz LA, movies and references to them are sparse. (I didn’t spot any.) So maybe we should take this film itself as standing in for righteous cinema, rather than the teenpic trash Nicole was in. Perhaps Marriage Story offers itself as its own example of the subtlety and risk-taking that cinema can embody. Even when streaming on Netflix.

Muses in the family

The family saga is one Hollywood genre that doesn’t get enough respect. We tend nowadays to celebrate the tough, not tender side of studio cinema. The cult of noir, the abundance of hard-edged action pictures, and the idolatry that trails Tarantino all tend to make us prefer force to gentleness. When families gather, we expect big trouble, if not outright murder (Knives Out). We decry weepies of any sort, and family sagas are often felt to be soft, schmaltzy, womanish. A male friend tells me that Little Women is “a movie about hugs.” When NPR devotes a whole show to it, panelists ponder how to convince men to see it. No wonder the family film has migrated to daytime cable TV.

Yet the family saga is one of the nicest things American cinema does. Two of our greatest masterpieces, How Green Was My Valley (1941) and Meet Me in St. Louis (1944), are prime examples. The Forties were rich in such efforts, including Forever and a Day (1943), Life with Father (1947), I Remember Mama (1948), The Human Comedy (1943), and Since You Went Away (1944). We ought to recognize as well the strength of later entries like The Joy Luck Club (1993), How to Make an American Quilt (1995), and Soul Food (1997), all trying out some of the fresh approaches to storytelling that were emerging in the 1990s.

And the sentiments informing domestic sagas seep into other genres. The Fast and Furious team, we’re told, come to be a family, as do the Avengers. The coming-of-age story, that perennial of indie cinema, inherits the aura of cozy warmth that is central to the family saga. I’d add one of my favorites, We Bought a Zoo (2011), which isn’t really a saga but does radiate a comparable warmth.

Although there are probably earlier examples (I think of Vidor’s 1924 Wine of Youth), it seems likely that the 1933 MGM production of Little Women furnished an important template. The four March sisters, each drawn to a different art form, are a model for the musically gifted sisters in the fine Four Daughters (1938).

And surely the fact that Katrin in I Remember Mama chronicles the family’s daily lives owes a lot to the example of Jo March, aspiring novelist.

The family saga poses at least three creative problems for the filmmaker. Since each family member is likely to confront personal problems (romance, finance, school, job) how do you weave and weight multiple storylines? How do you provide conflict to propel the action? And, since the “saga” comparison suggests development over years or even generations, how do you handle long spans of time cinematically?

Greta Gerwig handles all these problems adroitly in her version of Little Women. I’m going to concentrate on the film, but I’m aware that some of the narrative strategies are taken from Louisa May Alcott’s original novel. But much of what’s ingenious about Gerwig’s adaptation is of her own devising.

Start with storylines. In most such films, the trick is to create a group but then produce a scale of emphasis running from minor figures to the most important one typically, the “first among equals.” In How Green, that is Huw, also our narrator; in Meet Me in St. Louis, it’s Esther. But the doings of other characters shape the family’s destiny and the decisions made by the spotlighted figure. So the activities intertwine.

In Little Women, characters shape one another’s development. Jo, the first among equals, is nonconformist and self-reliant. Yet she needs steering–from Friedrich, the professor who tries to turn her away from sensation fiction, and more importantly from Beth, who in her sickness urges her to write “our story.” They give her the strength to persist and trust her sense of what her writing can be.

On the romance front, Jo’s rejection of Laurie’s proposal of marriage opens the field for sister Amy, who has already supplanted Jo in the role of amanuensis to Aunt March. When Jo, out of loneliness, decides to welcome Laurie’s offer, it’s too late: he’s married to Amy. The tangled alliances of melodrama get tightly bound in the family saga.

The other sisters contribute to the causal weave of the plot, with Meg’s decision to abandon the stage reinforcing Jo’s stubborn attachment to her art. More generally, the fates of the sisters dramatize the tension between creative impulse and the social demands of domesticity. Meg wants a family more than fame. Amy, the indifferent painter, can hope only for a good marriage (the same prospect Aunt March makes explicit to Jo).

In family sagas, the siblings are put in parallel. Huw’s brothers leave the household, but he loyally stays, and Rose, the mature sister, has more trouble attracting men than the vivacious Esther. Here, Jo’s kindred spirit is Beth the pianist, whose playing gives solace to Mr. Laurence in his grief. But illness keeps Beth from fulfilling herself either as artist or grown woman. As for Marmee, we’re allowed to catch a glint of Jo’s defiance behind the older woman’s warmth when she confesses that she’s angry every day.

Jo’s main contrast is with Amy. Amy has done nasty things, but she accepts the burden, laid down by Aunt March, of marrying for money, not love, in order to benefit her loved ones. She does this even though, as she reveals in a key scene, she has always loved Laurie and has always felt herself overshadowed by Jo. (Those revelations are also suggested as what leads Laurie to fall in love with her, and not simply as a substitute for Jo.) Even the various suitors get ranged along comparative dimensions of class, strength of will, and temperament.

The need to provide a dense social milieu also creates parallels–here, in terms of good deeds. The Marches are lower middle-class, living on a parson’s income, but they share their Christmas dinner with a more deprived family. The primary family is constantly compared to the wealthy Laurences, who are generous and good-hearted. Even Aunt March, who married well and embraced hardheaded principles, wills her mansion to Jo. The contrast with the flinty publishing house and the imperious Dashwood is softened when we learn, surprise, that he has a batch of daughters himself.

What about conflict in the family saga? There’s often an external threat–predatory capitalism in How Green Was My Valley, the war in The Human Comedy–but not always a personified antagonist. Often these films have no straightforward villains. Parental error can move the plot, as when in Meet Me in St. Louis Alonzo Smith announces that he’s taking a job in New York. And crises are created by misunderstandings or happenstance, most commonly illness. Somebody almost always gets hurt (here, Meg’s twisted ankle, Amy’s plunge through the ice) or sick (Beth’s scarlet fever).

By and large, the conflicts come through romance and sibling rivalry. In Little Women, Meg loves John only somewhat more than she loves fine clothes, so their impoverished marriage nags at her heart. Amy, enraged at not going to the theatre, burns Jo’s manuscripts. Jo responds with hatred–until Amy falls through the ice and needs rescuing. Amy later considers marrying a rich nonentity, and instead acknowledges her long love for Laurie–who in turn loves Jo. As in most melodramas, we know more than any one character, so we watch as characters’ hopes rise against forces they don’t yet realize.

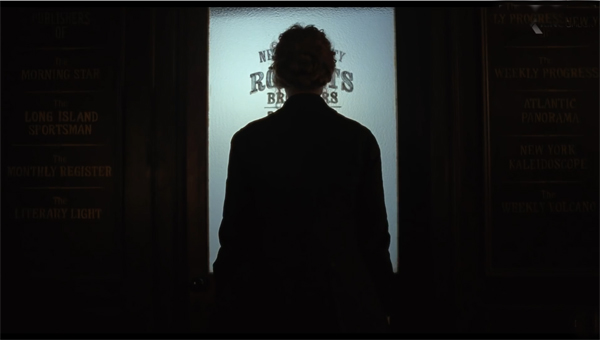

Even without a clear-cut antagonist, the family members can have goals. The March girls start out as aspiring artists, and stretches of the plot are devoted to them developing their abilities. As their goals change, swerving two of them to marriage and maternity, Jo keeps striving toward what we see her doing in the film’s very first scene: selling her stories. Her burning desire to write is a major through-line, and it encounters obstacles of many sorts, from the harrumphing Dashwood to the destruction of her manuscripts by Amy. And even Jo, as we’ve seen, recasts her goals: in offering solace to the dying Beth, she will write “all about us.”

That means writing about the family as it changes over time. Our third narrative problem, in other words.

“If I were a girl in a book, this would all be so easy”

Marriage Story‘s avoidance of flashbacks makes it unusual nowadays. It’s hard to find a movie without at least a few flashbacks. As mysteries, Motherless Brooklyn and Knives Out resort to them to replay scenes with new information. Other films make time shifts basic to their architecture. The Aeronauts uses flashbacks to supply the backstory to an unfolding crisis situation, while Hustlers switches between a contemporary interview and stages in the career of the woman questioned.

The Irishman goes for deeper embedding. The overall frame shows elderly Frank Sheeran in the care facility; the next frame is Frank’s trip with Russell Bufalino and their wives to upstate New York, where Frank will kill Hoffa. That trip in turn flashes back to the central story of Frank’s career with the mob. I try to show in Reinventing Hollywood that this sort of Russian-doll structure comes to be a major option in American film during the 1940s.

In Little Women, the years of change in the March family are given through alternating blocks. We start in the present, with Jo in New York struggling to get published. She’s summoned back to Concord because Beth is ill. Meg is living in poverty with husband John, and Amy is in Paris with Aunt March. For about eleven minutes, crosscutting carries us among the sisters.

This block of exposition is followed by a title, “7 Years Earlier,” that sets up the time oscillations we’ll get for the rest of the film. In chronological order we follow the sisters growing up. Chunks of scenes from the past, shifting viewpoint among several characters, alternate with briefer scenes of the ongoing present showing Jo’s settling back into the family. Sometimes the cuts break the blocks into smaller, interlocking bits, as when we shuttle quickly between Beth’s childhood illness and her death one year later.

Why split a linear story into two intercut strands? Flashbacks often create a specific sort of anticipation: Not just What will happen next? but What caused the outcome I already more or less know? In the first ten minutes we learn that Laurie proposed to Jo and she refused him; that Amy, not Jo, became Aunt March’s traveling companion; that Meg married John, the impoverished tutor. We’ll witness the development of all these turning points, and more. We must watch the rise and fall of characters’ hopes, knowing they will be dashed. But we also know, from Jo’s initial visit to the publishing house, that she will gain some success. This time-jumping gives us another level of omniscience, one that lets us savor the details of emotional scenes whose outcomes we roughly know. We’re in the theatre, after all, to enjoy the rapture of pathos.

Instead of tagging each time shift with a date, Gerwig expects us to keep track of the double-entry storylines. She assists us by making story motifs visual hooks between past and present. Silk for a dress, a key, Jo seen writing at a window–these link scenes but also carry dramatic weight in the ongoing action. Other echoes are longer-range. We’re invited to remember contrasting dance scenes (tavern, ballroom, porch), scorched dresses, and piano pieces.

Eventually the past scenes catch up with the present. The fusion comes with the burial of Beth and one more clutch of flashbacks, to Meg’s wedding. I take this as the end of the development section. “Childhood is over,” Jo says. Back in the present, Jo vows to abandon writing.

Now the present-time action dominates the climax. Grieving for Beth, distraught at Meg’s leaving the household, and crushed by the marriage of Laurie and Amy, Jo burns her manuscripts–except for the stories she wrote for Beth. She starts to assemble them and write more.

After a glimpse of Dashwood refusing the manuscript, we see Friedrich come to visit the Marches on his way to California. After he’s left for the station, the family claims that Jo obviously loves him.

At this point, in her most daring creative choice, Gerwig retains the crosscutting technique in a way that seems to continue the present/past alternation. Dashwood’s daughters have urged him to publish Jo’s manuscript. In New York, in a scene that rhymes with the opening passage, Jo negotiates with Dashwood.

Their conversation is intercut with views of Jo rushing to the station to catch Friedrich and ask him to stay.

The epilogue consists of more alternations. We see Jo watching Little Women being printed, crosscut with a party at the school Jo has founded in Aunt March’s mansion. There John, Friedrich, and Laurie can be glimpsed as Meg and Amy teach children the arts they had practiced. The celebration ends with a birthday cake presented to Marmee.

But there’s another way to take the final minutes. The alternation isn’t tracking two points in time–Jo’s rush to Friedrich and a later session with Dashwood–but rather a split between fiction and reality.

We’re coaxed to take scene of Jo’s pursuit of Friedrich as representing not her own action but the changes that Dashwood demands in Jo’s novel. “Who does she marry?” he asks, explaining that a book sells only if there’s a marriage. Jo reluctantly agrees. “I suppose marriage has always been an economic proposition, even in fiction.” Cut to Jo racing to the station. After the shots of her embracing Friedrich under an umbrella, we’re back in the office. Dashwood suggests the chapter title, “Under the Umbrella,” and Jo agrees. But in turn she makes demands: “You keep your five hundred dollars and I’ll keep the copyright. . . . I want to own my own book.”

We’ve assumed throughout that Jo’s book is highly autobiographical, but we’ve taken what we see and hear as actual events, the living source of a literary text. Instead, the crosscut climax allows a parallel reality to burst forth, a road not taken. The epilogue yields another ambivalent passage of crosscutting. The school party might be veridical; certainly the family would likely gather for Marmee’s birthday. But the scene could as well serve as the fictional epilogue in Jo’s book (as it does in the Alcott original).

The true epilogue of Jo’s story would then be the moment when she sees her book printed, action that’s crosscut with the celebration. Jo gets the first copy. In the last shot, pleasure, apprehension, and determination play across her features. And she’s framed in a window, an approximate reverse shot to the image that opened the film (see image at the top of this section).

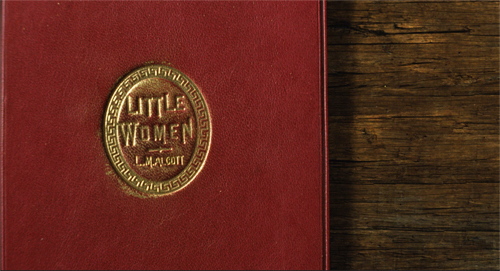

From the start Gerwig has shrewdly foreshadowed the turn to fiction by presenting the film’s title, after Jo has made her first sale, not as an inscription on the screen but as the physical book itself. That book is signed by L. M. Alcott. The apparently identical volume that comes off the printing press at the end bears the name J. L. March. Gerwig has let Jo appropriate Alcott’s story.

By giving us a double-voiced ending, Gerwig does something quite bold. Little Women becomes something of a “what-if” movie, positing two paths for her heroine. Alcott’s Jo had given up a literary career, whereas Gerwig’s Jo finds one by writing her own life and adding an optional ending. We’re free to think that Jo and Friedrich married and the family became a harmonious whole, as in Alcott’s book. A happy ending, we might say, for those who want one. But this film about hugs ends with the heroine hugging not a husband but her novel.

Unmarried in life, Jo can marry in fiction, and Gerwig can have it both ways. Narrative lets you do things like that.

I haven’t been able to do justice to the intriguing choices made in other films of the season. I appreciate, for instance, the nonlinearity in Kasi Lemmons’ Harriet, where the interruptions of present-time action offer Harriet’s premonitions of future scenes. This sort of “prophetic” flashforward is rare; usually such passages are presented as omniscient narration, not assigned to characters. But the device does establish Harriet as a sensitive, almost angelic figure, and suggests that her quest to guide slaves to freedom is sustained not just by faith but by holiness.

Still, looking in a little depth at just two major films can make us aware of several choices available to filmmakers at this point in history. As Wölfflin said, “Not everything is possible at all times.” But film researchers can usefully trace the flexible menu of options that filmmakers work with, and film viewers come to master.

Gerwig has kindly made available a version of the screenplay, which I discovered only after I wrote this. (Thanks, Kristin.) The notations for the final sequences are pretty interesting. The most wide-ranging discussion I’ve seen of the ending, with plenty of links, is the conversation between Marissa Martinelli and Heather Schwedel in Slate. Among several perceptive reviews, I’d single out the one in Time by Stephanie Zacharek and Richard Brody’s review in The New Yorker.

I can’t help but think how central crosscutting, that technique pioneered by early filmmakers, is to both of these films. Techniques endure because they open up a lot of expressive possibilities.

Kristin elaborates on arguments for four-part plot structure in Storytelling in the New Hollywood: Understanding Classical Narrative Technique. Extended examples on this site are here and here. I discuss family sagas of the 1940s, along with flashbacks, protagonists, and other narrative techniques in Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling. On 1990s revival of these techniques, see The Way Hollywood Tells It: Story and Style in Modern Movies.

Marriage Story (2019). Is this why the film includes few standing two-shots of Nicole and Charlie?

Attachment anxieties at the Vancouver International Film Festival

DB and KT, front row center, at the screening of The Lighthouse. Photo by Shelly “Sales Agent Cinema” Kraicer.

DB here:

Storytelling cinema depends on characters, and our relations to them. At the level of individual scenes, we can be more or less restricted to what they experience; we can know as much as they do, or more, or less. Across a film, the filmmaker can attach us consistently to one or two characters, or instead roam freely among many viewpoints. And within a scene, the filmmaker’s choice of camera placement can put us “with” one character or another.

In other words, narrative cinema 101. But it’s worth remembering that these are forced choices. As a filmmaker, you can have restricted or unrestricted access to characters, but at every moment you have to choose one or the other. How objective or subjective will you make your presentation? Will you limit your camera setups or go for ubiquity–that tendency to give us shots divorced from the immediate situation? Examples are a drone-delivered image above a city, or that sudden high or low angle that calls our attention to a detail the characters may have missed.

Three films at the Vancouver Film Festival presented a nice menu of attachment options–ways in which we can be tied to our protagonist. All are well worth your attention, so without getting too much into spoilers, I’ll use them as an occasion to study how these forced choices are handled creatively.

The party’s over

Take as a midrange example The Realm (El Reino, 2018), a Spanish political thriller directed by Rodrigo Sorogoyen. Manuel López Vidal is a brisk, no-nonsense functionary enjoying the good life thanks to the corruption of his party. He and his colleagues, the Amadeus Group, meet regularly over expensive meals to plan their schemes of influence-peddling and money laundering. They tease their fastidious accountant about his meticulous ledgers, but those records will become important to Manuel when one colleague leaks incriminating audio tapes of Manuel’s dealmaking. There’s an orgy of document shredding, damage control among the party’s top brass, and the growing likelihood that Manuel will go to jail.

The screenplay restricts nearly all the action to Manuel. This method is established at the start, when a long tracking shot follows him from the beach as he strides into an Amadeus lunch. Thereafter, we’re with him as he learns of the danger he’s in and mounts one tactic after another to save himself. At a couple of moments the camera lingers on his colleagues’ reactions after he’s left the scene, but on the whole we’re firmly attached to him. Some virtuoso long takes, including a ten-minute shot that follows Manuel’s frantic search for the ledgers, virtually fetishize our adhesion to the protagonist.

By and large, the presentation doesn’t delve into his mind. The throbbing techno score conveys his growing panic as he strides from one confrontation to another, but we get no voice-overs, or flashbacks, or mental imagery. And we don’t see Manuel confide his plans to others (although he seems to have told his wife some of them offscreen). This degree of objectivity allows more suspense, as his schemes to save himself unfold in the moment. We must figure out why he’s bracing one colleague, or bursting into a friend’s home in the course of a teenage party. His manic resourcefulness is all the more impressive when he keeps dodging new problems, often revising his plan on the fly.

It’s no easy feat to maintain tension across two hours, especially when we’re asked to invest our sympathy in a corrupt politician, but The Realm manages it. It’s achieved partly through the trim, crisp performance of Antonio de la Torre but also through plot and style: the refusal of omniscient narration (say, showing us the police or party officials tracking him) and a mild degree of camera ubiquity that accentuates the character’s plight, whether in a meeting or all alone.

The Realm is a good example of how manipulating character attachment can strongly engage the audience. We know just enough to understand Manuel’s crisis, but without access to his mind, each scene can yield a surprise when he comes up with a new survival stratagem.

A lot from a little

I hadn’t really considered the Dardennes brothers “minimalist” filmmakers, but seeing Young Ahmed brought home to me how strictly they’ve limited their cinematic palette. Given their emphasis on actors and faces, you might think they rely on the sort of “intensified continuity” on display in modern film and television. Yet they’re far more purist than that, and they take objective presentation further than does Sorogoyen.

They seldom use long shots, let alone establishing shots: a scene starts in medias res with character action, shot from quite close. Filming in handheld long takes, they avoid shot/reverse-shot cutting, either panning between participants in a dialogue or simply framing them in tight two-shots.

The Dardennes minimize camera ubiquity. Not for them the picturesque, distant shots that The Realm sometimes provides. In a car carrying two passengers, the camera isn’t lashed to the hood or filming alongside; it’s in the back seat.

True, cutting yields some ubiquity. When Ahmed’s teacher pursues him through a classroom, she runs ahead of us but then, in the next shot, she catches up with him as he’s about to leave the building.

Like most cuts, it’s an instantaneous change of position that a real observer couldn’t execute. Still, this frame-edge cut creates simple continuity, driven by dramatic necessity and barely noticeable. The cut is softened by a staging that neatly settles into a standard over-the-shoulder setup.

Apparently uninterested in pictorial composition, these filmmakers simply center their subjects in undistinguished framings. No shot becomes strikingly lit or framed. There’s no nondiegetic music, and the soundtrack is subdued; of all modern filmmakers, they benefit least from surround channels.

As in The Realm, the Dardennes’ minimalist approach works well in tying us to the protagonist, while also denying us direct access to his mind. Ahmed, an adolescent in Liège, has given up video games for fundamentalist Islam. Convinced by his imam that his classroom teacher has become an apostate, he decides to take action against her.

His plans emerge wholly through his actions. Without benefits of voice-over, subjective sequences, or flashbacks, we must infer how he will respond to the demands of the Qu’ran as he has been taught to understand it.

The Dardennes’ objectivity doesn’t make the plot hard to follow. A dozen minutes into the film, the premises are clear, the main characters (Ahmed’s mother, his imam, his teacher) are delineated, and Ahmed’s motivation is established. At the half-hour point, his mission is launched. Apart from the ellipsis I mentioned, everything that follows stems from the dramatic premises. And however horrifying Amed’s plans may be, the wistful, pursed-mouth young actor Idir Ben Addi is mesmerically angelic. His glasses make him look adorable.

The style also keeps everything clear. The texture is close to that of documentary filmmaking, but of course the Dardennes’ films are scripted and staged. There’s a high degree of artifice in their apparently artless method. As in the more flamboyant Birdman, their long takes catch every reaction and gesture with great precision.

We always see what we need to see at just the right moment. When something is suppressed–here, the result of a violent knife attack–it’s not an accident (as if the camera were in the wrong spot) but rather the result of our attachment to Ahmed and a clever narrative ellipsis. We could have had a cut like the one in the school, but we remain with Ahmed, and in fact know a bit less than he does about the result of the violence.

All of which is not to deny the originality of Young Ahmed. All the Dardennes films seem modest, but they are, within their limits, quite ambitious in using dramatic psychology to probe social problems. Throughout, I think, we are asked to reflect on how firmly Ahmed believes in his version of Islam. Is it a transitory teen obsession or is he on his way to becoming a dogmatic martyr? We watch his behavior, his encounters with farm life and a young girl, for any signs that his lonely, taciturn demeanor will crack. In other words, this is a suspense film–one based less on the threat of violence (which is there, to be sure) than on how a boy who hasn’t fully formed his character will define himself.

Not such light housekeeping

Both The Realm and Young Ahmed are, to varying degrees, objective in their presentation. We must judge characters by what they do and say. Something very different is going on in Robert Eggers’ The Lighthouse. It too adheres largely to one character, but a battery of cinematic techniques, including camera ubiquity, works to plunge us into the man’s mind.

Although the film is a two-hander, it doesn’t balance viewpoints. Thomas Wake, an experienced lighthouse supervisor, arrives at his post with the novice Ephraim Winslow. Almost immediately we are attached to Winslow, who’s assigned grimy menial duties while Wake tends the beacon. Wake tells Winslow that his previous assistant went mad from the weeks of isolation, and very quickly Winslow struggles against the bleak, craggy island they’re on.

We’re prepared for an assault on your senses by the opening, when a ship roars out of the fog toward us. Thereafter, Wake subjects Winslow to a punishing routine of cleaning the cistern, heaving coal into the boiler, and scrubbing floors, while nightly meals with the nattering old salt are just as hard to bear. Winslow’s misery is rendered in vivid, expressionist terms. The deafening fog horns, thunderclaps, and boiler blasts are reinforced by stark, ominous black-and-white imagery. (The film was shot on 35mm film.) Winslow seems trapped in a world of raging elements and gigantic machines.

Eggers builds our affinity with Winslow through classic techniques. He watches Wake at the beacon from a distance; we get optical point-of-view shots of discoveries (real? imagined?) that start to unhinge him.

All the drudgery and pain, punctuated by Wake’s continual harangues and farts, lead Winslow into fantasies and hallucinations. His deterioration is rendered in shock cuts and distended compositions reminiscent of Welles’ Mr. Arkadin or German’s Hard to Be a God. Some will compare the film’s over-the-top climax to that of Aronofsky’s Mother!, but The Lighthouse, with its rapid montage and Gothic chiaroscuro, harks back to silent cinema. The fact that it’s shot in the 1:1.17 ratio favored by early sound film gives it an archaic feel as well. The dialogue, a late title informs us, is drawn from nineteenth-century sources, including Melville and Sarah Orne Jewett.

The Lighthouse has a cadence typical of modern horror films, but Kristin points out that it’s an expressionistic Kammerspiel too–a subjectively tinted drama setting very few characters in a constrained locale. Eggers shows that you can renew a genre’s appeals by reviving imagery from a classic period of film history. When you do it, you’ll still have to make fundamental choices about viewpoint and camera placement. They come with the territory.

We thank Alan Franey, PoChu Auyeung, Jenny Lee Craig, Mikaela Joy Asfour, and their colleagues at VIFF for all their kind assistance. Thanks as well to Bob Davis and Shelly Kraicer for invigorating conversations about movies.

For more on classic Kammerspiel films go here and here.

The Lighthouse (2019).

Telling the big story: Network narratives at Venice 2019

The Laundromat (2019).

DB here:

Every now and then I wonder whether network narratives, to revert to the term I coined a while back, have faded from the scene. Although there are some examples earlier in film history, that storytelling model had a sustained burst after Altman popularized it in Nashville (1975). Other filmmakers took it up, especially in the 1990s (Before the Rain, Exotica, Go, Pulp Fiction, etc.) and the 2000s (Babel, Dog Days, Love Actually). I don’t seem to see so many nowadays, and the almost universal loathing greeting Life Itself (2018) might seem to indicate that a tale relying on remote connections and unexpected convergences had run its course.

Surprising, then, to see three items at Venice that rely to a degree on the network narrative format. Each is based on a nonfiction book aiming to reveal the dynamics of a large-scale process. In each film, process becomes a framework for personal stories and converging fates.

Wasps in the Caribbean

Olivier Assayas’s Wasp Network isn’t as far-reaching as the title implies. It concentrates on two couples and one individual caught up in 1990s spying. When René Gonzales, a pilot, defects to Florida, he seems to be seeking freedom and a new life working with Cuban exiles to destabilize Castro’s regime. Branded a traitor, he leaves behind a wife and daughter who must bear social opprobrium. Actually, he is a Cuban agent, part of the “Wasp Network” that will infiltrate the anti-Castro forces.

Another exile, Juan Pablo Roque, works with the Network, but he is also leading a double life–one quite different from René’s. Just as René’s sacrifice wrecks his relation with his family, the headstrong Juan Pablo jeopardizes his relation to his lover Ana Margarita. Both men are linked to Gerardo Hernandez, who coordinates the Network.

As in most spy stories, we’re led to discover double agents and surprise alliances, as well as the conventional emphasis on the personal cost of espionage. As the film goes along, that emphasis becomes stronger; scenes tracing the tactics of the anti-Castro forces (such as invading Cuban airspace to drop leaflets) give way to long confrontations between couples and the efforts of Rene’s wife Olga to unite with him in the US.

Because network plots need to fan out across many characters, filmmakers often break up the linearity of time. In Wasp Network, the reunion of the two major defectors, Juan Pablo and René, is followed by a passionate scene of Olga being defeated by Cuban bureaucracy. Abruptly the plot skips back four years to introduce Gerardo, and his career as a double agent is summarized. A montage, complete with a narrator’s voice-over, links the three men in the years 1990-1992. Then, back in the present, Gerardo meets with Olga to reveal that René is a patriot, not a traitor.

Visually, the film is surprisingly ordinary, I thought, sort of standard TV. If you like over-the-shoulder shot/reverse shot, there’s plenty here for you.

Assayas garnishes his reverse angles with alternating push-ins, a technique that has become a bit hackneyed since John McTiernan’s skillful use of it.

The film compels some interest by virtue of its origins. Based on the FBI case against the “Cuban Five” and the book The Last Soldiers of the Cold War, it employs vintage broadcast news coverage cut in for expository purposes. I had known almost nothing of this historical episode, and thanks to the cooperation of Cuban authorities Assayas benefits from showing a story we Americans seldom see. Still, by concentrating on only a few characters and having them played by Édgar Ramírez, Penélope Cruz, and Gael García Bernal, whose presence demands extensive scenes, the larger dynamic of the Wasp Network fades into the background. Despite its title, maybe it’s only a borderline case of a network narrative.

Coke ZeroZeroZero

ZeroZeroZero is also based on journalistic reportage, in this case Roberto Saviano’s book of the same title. (An earlier Saviano true-crime investigation is the source of the 2008 film Gomorrah, another network narrative.) The subtitle of his book–Look at Cocaine and All You See Is Powder. Look Through Cocaine and You See the World–suggests the vast ambition of his project. From the book Sky, CanalPlus, and Amazon Prime have developed an eight-part series to be broadcast and streamed in 2020.

Since I’m not the world’s biggest TV consumer, I wasn’t interested until I read the presskit, which promises something sweeping.

The series follows the journey of a cocaine shipment from the moment a powerful cartel of Italian criminals decides to buy it until the cargo is delivered and paid for. Through its characters’ stories, the series explains the mechanisms by which the illegal economy becomes part of the legal economy and how both are linked to a ruthless logic of power and control affecting people’s lives and relationships.

The prospect of following a coke-packed container as it passes through various hands appealed to me. I enjoy circulating-object plots like Winchester 73 and The Red Violin, as well as those 1920s Soviet Constructivist “biographies of things” (such as Ilya Ehrenberg’s Life of the Automobile).

ZeroZeroZero, though, isn’t quite that sort of thing. Judging by the first and second episodes, the only ones screened at Venice, this will be more conventional. The plot shifts among dramas within groups of stakeholders in the shipment. We see the power struggle in an Italian crime family, with a son aiming to usurp his grandfather. There’s another family drama in New Orleans, where a ruthless shipping-company owner insists, against his son’s and daughter’s resistance, on booking the cargo. In Mexico, a corrupt special forces sergeant works behind the scenes to assure that the shipment will not be disturbed.

The narration cuts among these storylines until, at the end of episode 2, the cargo embarks on the seas. Doubtless the remaining episodes will ramify into other story lines, but I’d expect at least the Italian and American ones to be on tap throughout–if only to maintain the interest of streamers’ European and US audiences.

The film was directed and co-written by Stefano Sollima, who has done several TV dramas as well as the feature film Sicario–Day of the Soldado. ZeroZeroZero certainly had a higher-gloss look than Wasp Network, with dramatic lighting and elaborate action scenes. One of these, a police attack on the big meeting of the stakeholders, is replayed from different character viewpoints in the two episodes. Like Wasp Network, ZeroZeroZero amplifies its expanding network through time-shifting, and this attack is revealed to be a node, a point of convergence among the three main groups of characters. Given current TV’s fascination with scrambled time schemes, I’d expect other nodes and replays to emerge in the course of the series.

Capitals of capital

Eisenstein planned to make a film of Marx’s Capital. He would have used his montage editing methods to survey an economic system–without benefit of individualized protagonists. In The Laundromat Stephen Soderbergh has tried to do something akin to this, but like most filmmakers he’s obliged to personalize his drama (as he did in Traffic and Contagion). Soderbergh has compared the film to Dr. Strangelove, largely because of the need to make a devastating situation entertaining. But I think his film recalls Strangelove as well in its emphasis on villains who get caught up in the insanely complicated system they create.

Mossack Fonseca was a law firm in Panama that specialized in tax evasion. It registered over 300,000 companies, many of which were shell entities that enabled money laundering and fraud. The firm had subsidiaries in the Bahamas, Hong Kong, Switzerland, and other countries. In 2016, German investigative journalists published 11.5 million internal documents known as the Panama Papers, mostly centering on Mossack Fonseca. As the journalists explain:

Clients can buy an anonymous company for as little as USD 1,000. However, at this price it is just an empty shell. For an extra fee, Mossack Fonseca provides a sham director and, if desired, conceals the company’s true shareholder. The result is an offshore company whose true purpose and ownership structure is indecipherable from the outside.

Despite its vast scale, the firm represented at most ten percent of the global market of offshore finagling.

Tax havens and shell companies are more or less legal. What brought down the company was the breach of confidentiality. In addition, the possibility of fraud hovered over the big names revealed as beneficiaries. Politicians throughout Europe and China were named, as were filmmakers Jackie Chan and Pedro Almodóvar. International villains associated with Bashar al-Assad and Vladimir Putin moved money through Mossack Fonseca; a Russian cellist had holdings of $2 billion. After the leaks, the rich couldn’t trust Mossack Fonseca to keep their secrets.

Building on Jake Bernstein’s book Secrecy World, Soderbergh and screenwriter Scott Z. Burns have concocted a sweeping tale of how the rich are very, very, very different from you and me. But in scale, the network they’re surveying dwarfs the Wasps and the voyage of a coke shipment. How do you convey the vastness of an alternative financial system?

The film’s pop-Brechtian mode of presentation will earn comparisons to The Big Short, but here instead of one-off celebrity tutors (Margot Robbie, Anthony Bourdain) we get the chattering rogues themselves, Jürgen Mossack (Gary Oldman) and Ramón Fonseca (Antonio Banderas). Their to-camera accounts of “fairy tales that actually happened” settle into a block construction, five chapters “based on actual secrets.”

The first chapter title, “The Meek Are Screwed,” provides an emblematic case of how the little people are connected with this network of virtual money. Chief among those Meek is Ellen Martin (Meryl Streep), whose husband Joe is drowned when a tour boat capsizes.

Hoping to have her grief assuaged by an insurance settlement, she learns that one isn’t forthcoming because the boat company bought a worthless policy from a shell company. The film’s first two chapters follow her efforts to find someone responsible. She finally tracks down a fraudster named Boncamper, a Mossack Fonseca figurehead who has grown rich (and accumulated two families) simply by signing thousands of documents.

Having shown how the shell-company shuffle affects ordinary folks, the film moves on to the high and mighty. One chapter traces the backstory of the company, another shows how an extraordinarily rich family uses the system to one-up each other, and a final chapter depicts murder among the Chinese plutocracy. The fourth block, illustrating the lesson of “Bribery 101,” is especially juicy in showing a father using bearer bonds to force his daughter to keep silent about his extramarital affair. As Marx and Eisenstein would expect, economic relations seep into personal ones. Bribery is all in the family.

The Laundromat’s breezy, self-righteous impresarios cast a comic tone over everything. Even the murder doesn’t seem awful, considering the victim’s own corruption. Only at the end does indignation emerge in a twist. Ellen, almost forgotten for the last half-hour, reappears in a new guise and takes over the narration from the villains. An agitprop ending reminds us that the capital of money laundering may well be the US, where Nevada, Wyoming, and above all Delaware play a role comparable to the Caribbean. Soderbergh and Burns (who confess to having offshore stashes themselves) end by firmly snagging their American audience in the colossal spiderwebs of global capital.

Nearly every narrative involves a social network of some size, even if it’s only a family. The most thoroughgoing network plots provide us roughly equal attachments to many viewpoints. The film demotes individual protagonists, in favor of revealing x degrees of separation among several individuals. Wasp Network, ZeroZeroZero, and The Laundromat don’t have the complexity of the network narratives of earlier years, but they serve to remind us that the network schema can be tweaked to suit the needs of particular creative projects.

Thanks to Paolo Baratta and Alberto Barbera for another fine festival, and to Peter Cowie for his invitation to participate in the College Cinema program. We also appreciate the kind assistance of Michela Lazzarin and Jasna Zoranovich for helping us before and during our stay.

For more on network narratives, see Chapter 7, “Mutual Friends and Chronologies of Chance,” in Poetics of Cinema. Jeff Smith considers Once Upon a Time . . . in Hollywood as a network narrative, and earlier entries (such as here and here) develop the idea as well.

To go beyond our Venice 2019 blogs, check out our Instagram page.

ZeroZeroZero (2020).

Cornell Woolrich: The overstrained imagination goes to the movies

DB here:

Can a storyteller be maladroit in using his or her medium and still be worth reading? Can a novelist with a clumsy style be a “good writer”? I’ve posed this question before on this site, and developed an argument about it at length in our book on Christopher Nolan.

Here’s a test case. These are real sentences from books by a novelist many consider one of the great crime/mystery writers of all time.

The knob felt cold and glibly elusive under his touch.

His face was an unbaked cruller of rage.

La Bruja lidded her eyes acquiescently.

I began treacherously touching up my hair via the mirror.

I crawled up onto the seat by means of my hands.

She could feel her chest beginning to constrict with infuriation.

This time the man got up off the bench, taking Quinn’s hand on his shoulder along with him.

Smoke suddenly speared from her nostrils in two malevolent columns. She looked like Satan. She looked like someone it was good to stay away from.

I was probably just a blurred bottle-green offside to her retinas.

“Made it,” Joan Bristol exhaled relievedly.

Seconds went by in packages of sixty.

The foaming laces that cascaded down her were transparent as haze against the light bearing directly on her from the room at her back. Her silhouette was that of a biped.

These passages, and many more like them, were published in books issued by major houses and still in print today. Can anything redeem them?

I’m currently trying to write a book on principles of popular narrative, with a focus on genres of crime and mystery. The project stems from arguments in Reinventing Hollywood and The Way Hollywood Tells It, but I wanted to broaden my inquiry to include theatre and literature as well. One section is about crime writers of the 1940s and 1950s. So naturally I had to include the widely renowned Cornell Woolrich.

Despite his struggles with syntax and word choice, Woolrich has been a perennial source of popular storytelling. Nearly all the novels were brought to the screen soon after publication, and radio versions of the books and short stories were plentiful. By the 2010s his work had inspired over a hundred movies and television shows (directed by, among others, Hitchcock, Truffaut, Fassbinder, and Jacques Tourneur).

That research has led me two further questions. Are there aspects of his work that counterbalance howlers like those above? And what might have led to those stylistic problems? Readers looking for more direct and detailed studies of film versions of his work can go to Francis M. Nevins’ exhaustive biography and Thomas C. Renzi’s careful consideration of adaptations. (And my studies of The Chase, if you want.) Meanwhile, tackling the questions that interest me, I’ll touch on aspects of cinema a little bit. File this blog under Questions of Narrative Across Media.

Breathless reading

Cornell Woolrich is usually treated as an author with a uniquely haunting voice. Alcoholic and homosexual, he lived for decades in a hotel with his mother. After she died, he lost a leg to untreated gangrene. He dedicated one book to the typewriter on which he pounded out pulp stories and thriller novels, the most famous of them published in the years 1940-1948. His tales of suspense cultivated a hothouse morbidity. At his limit, Woolrich projects a paranoid vision of life without hope and death without dignity.

Cornell Woolrich is usually treated as an author with a uniquely haunting voice. Alcoholic and homosexual, he lived for decades in a hotel with his mother. After she died, he lost a leg to untreated gangrene. He dedicated one book to the typewriter on which he pounded out pulp stories and thriller novels, the most famous of them published in the years 1940-1948. His tales of suspense cultivated a hothouse morbidity. At his limit, Woolrich projects a paranoid vision of life without hope and death without dignity.

Despite his distinctive sensibility, Woolrich epitomizes some broader narrative strategies of his time. Like all popular writers, he inherited situations, techniques, and themes. To present a bleak, aching world of precarious love and doomed lives, he twisted those conventions into eccentric shapes that added to the Variorum of 1940s mystery storytelling.

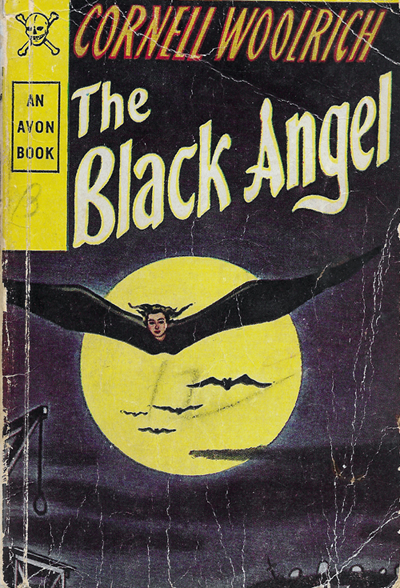

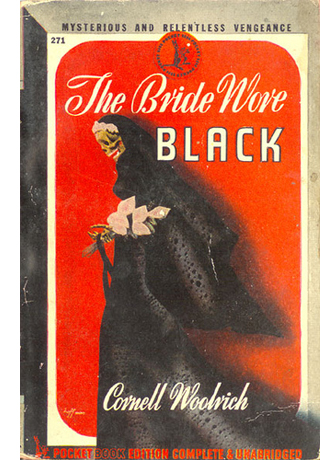

For him, one bout of amnesia isn’t enough, so The Black Curtain (1941) doubles it: the hero, already having forgotten his previous identity, is clobbered by some falling bricks and now can’t remember who he just was. The prototypical serial killer of the 1940s is a man, but The Bride Wore Black (1940) lets a woman stalk her victims. Most thriller novelists are content to put one woman in jeopardy per book, but Black Alibi (1942) lines up six. Alternatively, when a woman tries to save her husband from the chair by investigating four suspects, she’s plunged into danger every time she meets one (The Black Angel, 1943).

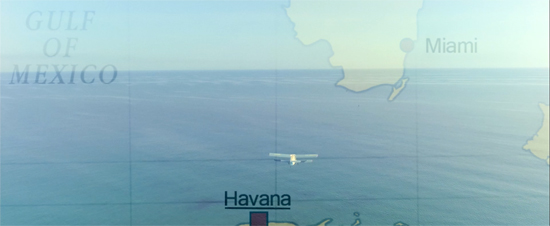

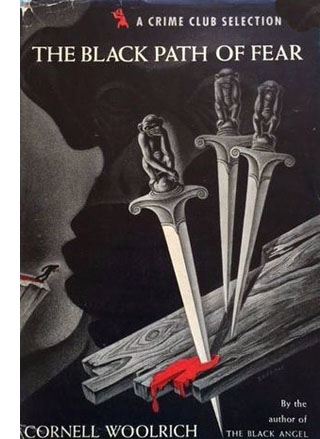

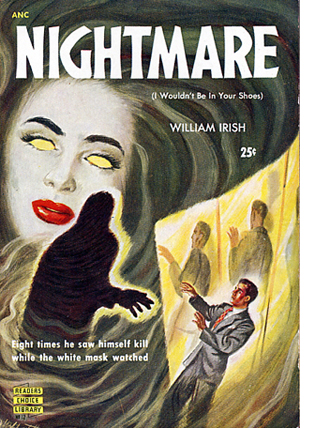

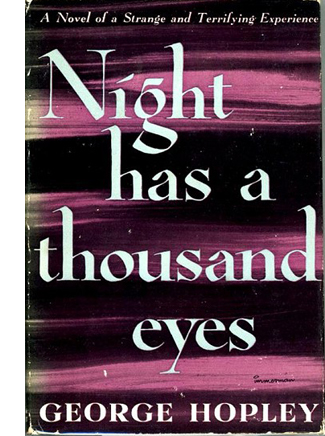

Woolrich’s plots flout police procedure (his cops are exceptionally willing to help suspects), and the authorities often flounder. Suspense thrillers usually invoke the supernatural only to dispel it, but in Night Has a Thousand Eyes (1945) the authorities fail to save a life because one old man really can predict the future. Not that amateur sleuths fare much better. The unheroic hero of The Black Path of Fear (1945) could hardly be more ineffective; he has to be rescued by the Havana police.

Sometimes the straining for originality snaps. Critics have long pointed out improbabilities and contradictions in the plots. Woolrich’s most devoted chronicler, Francis M. Nevins, warns of “chaotic ambiguities.” The chronology of Rendezvous in Black (1948) is impossible, while the climactic revelation of I Married a Dead Man (1948) is arguably incoherent. Convenient coincidences abound. Add to this a hypertrophied style that in every book slips into unabashed weirdness. (See above.)

Both the plot problems and the vagaries of language can partly be attributed to the rush of Woolrich’s production, his transport while hammering at his Remington Portable. Pulp author Steve Fisher recalled: “Sitting in that hotel room he wrote at night—continuing through until morning, or whenever the story was finally completed. He did not revise, polish, and I suspect did not even read the story over once it was committed to paper.” Although Woolrich was grateful to editors who corrected his hundreds of errors in spelling and punctuation, he apparently resisted efforts to touch up his prose. When an editor suggested a change to a single paragraph, he replied, “I knew you wouldn’t like it,” and left the publisher forever.

Both the plot problems and the vagaries of language can partly be attributed to the rush of Woolrich’s production, his transport while hammering at his Remington Portable. Pulp author Steve Fisher recalled: “Sitting in that hotel room he wrote at night—continuing through until morning, or whenever the story was finally completed. He did not revise, polish, and I suspect did not even read the story over once it was committed to paper.” Although Woolrich was grateful to editors who corrected his hundreds of errors in spelling and punctuation, he apparently resisted efforts to touch up his prose. When an editor suggested a change to a single paragraph, he replied, “I knew you wouldn’t like it,” and left the publisher forever.

Admiring readers excuse the faults by testifying that Woolrich’s evocation of tension keeps the pages turning. “Headlong suspense created by total, unrelieved anxiety,” noted Jacques Barzun. “Breathless reading is the sole pleasure.” Raymond Chandler called him the “best idea man” among his peers, but admitted, “You have to read him fast and not analyze too much; he’s too feverish.”

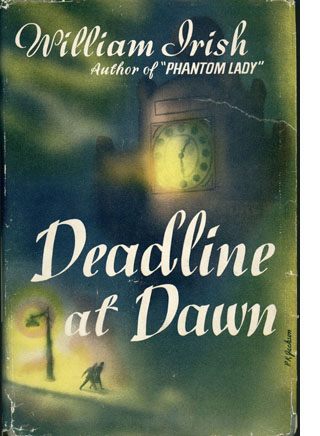

What keeps us reading? For one thing, the outré story situations. A couple hurrying to leave New York must clear the man of murder before the bus leaves (Deadline at Dawn, 1945). A killer stalks a city, but it’s not a human: it’s (apparently) a black jaguar escaped from a sideshow (Black Alibi). A mail-order bride seems unacquainted with things she wrote in her letters (Waltz into Darkness, 1947). Most famously, a man laid up in his apartment thinks he sees traces of a killing through a window across the courtyard (“Rear Window,” 1942).

Outrages to plausibility carry their own allure. What, we ask, might come of these wild mishaps? A train crash kills a husband and his pregnant wife. In the melée an abandoned woman, also pregnant, is mistaken for her and welcomed by the husband’s family. Conveniently, the in-laws have never seen the wife (I Married a Dead Man, 1948) A man accused of murder has an alibi, to be provided by a woman he met in a bar and took to a show. Trouble is, she’s vanished. All the witnesses deny she existed (Phantom Lady, 1942).

The development of the action also presents intriguing reversals. The man gulled by the fake mail-order bride falls in love with her. People who claim not to have seen the phantom lady wind up dead. The woman trying to exonerate her husband falls in love with the real killer and dreams about him even after he has killed himself.

The game is afoot

Woolrich’s novels tend to rely on two basic plot patterns, both based on the hunt. In one, amateurs try to solve a crime and move from suspect to suspect. Our viewpoint is mostly tied to the investigators. In the other pattern, a serial killer stalks a string of victims, and here Woolrich is more innovative. Normally, the serial-killer plot either concentrates on the killer’s viewpoint, as in the novels Hangover Square (1941) and In a Lonely Place (1947), or concentrates on the investigators, as in Ellery Queen’s Cat of Many Tails (1949). A few constantly bounce the spotlight among all the parties—killer, victims, and investigators—as in Fritz Lang’s film M (1931) and Philip MacDonald’s novel X v. Rex (1933).

Woolrich by contrast emphasizes the victims’ viewpoints. The killer might appear only at the beginning and end (Rendezvous in Black) or get introduced at intervals in brief, objective scenes (The Bride Wore Black). Less space is devoted to the investigators, although they gain prominence as the crimes pile up. Woolrich puts his energies into building waves of suspense as one target after the other confronts death.

The shooting-gallery structure enables Woolrich to fulfill Mitchell Wilson’s demand that the thriller devotes its energies to showing what fear feels like. The 1940s interest in intense subjectivity of narration helps out here, and Woolrich sustains it in detailed description of victims’ reactions. In Black Alibi, Teresa is being stalked by an unseen figure.

The shooting-gallery structure enables Woolrich to fulfill Mitchell Wilson’s demand that the thriller devotes its energies to showing what fear feels like. The 1940s interest in intense subjectivity of narration helps out here, and Woolrich sustains it in detailed description of victims’ reactions. In Black Alibi, Teresa is being stalked by an unseen figure.

Something else now assailed her, again from without herself, but of a different sensory plane than hearing this time. A prickly sensation of being watched steadily from behind, of something coming stealthily but continuously after her, spread slowly like a contraction of the pores, first over the back of her neck, then up and down the entire length of her spine. She couldn’t shake it off, quell it. She knew eyes were upon her, something was treading with measured intent in her wake.

This passage is part of a ten-page account of the woman’s wary progress through a night street, rendered wholly from her viewpoint.

Woolrich’s other basic plot pattern, the investigation of a murder, plays up the role of fear as well. His amateur detectives, lacking official firepower, are constantly facing danger from the suspects they track.

Fright was like an icy gush of water flooding over them, as from burst pipe or water-main; like a numbing tide rapidly welling up over them from below. [Deadline at Dawn]

In both of his favored plot schemes, the plunges into characters’ minds and bodies help fill out a full-length novel. If you play down other lines of action (professional police investigation, killer’s mental life), you need to dwell on the reactions of the victims or amateur detectives.

Yet this very emphasis is one source of the stylistic howlers. In expanding his suspense scenes, Woolrich’s prose sometimes fails him. Needing to spin out lots of words evoking an ominous atmosphere, he’s tempted to pileups like this:

And the path that had led me to it through the night had been so black and so full of fear, and downgrade all the way, lower and lower, until at last it had arrived at this bottomless abyss, than which there was nothing lower. [The Black Path of Fear]

Such rodomontade carries the 1940s emphasis on subjectivity to paroxysmic limits.

He recruits other techniques of popular storytelling. They keep his action moving forward through time and plunging inward into the unfolding scenes. And some can help mask story problems.

By hinging his story around a search for a killer or a victim, Woolrich’s plots tend create a string of one-on-one encounters. Rather than disguising the episodic quality of these, he sharpens them by breaking the action into distinct blocks. Those blocks are presented as a checklist agenda, Woolrich’s equivalent to the closed circle of suspects we find in the classic weekend-house-party detective story.

The Black Angel is a simple instance.

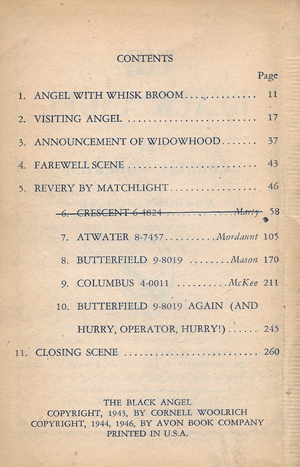

After an initial cluster of five chapters presenting Kirk Murray sentenced to death, we follow Kirk’s wife Alberta as she seeks the true killer. Her efforts are given in five parallel chapters, each indented and tagged with a telephone number. One that Alberta finds scratched out in an address book is presented just that way in the chapter title: “Crescent 6-4824.” Because at the climax she returns to one of the four suspects, another title gets recycled: “Butterfield 9-8019 Again (And Hurry, Operator, Hurry!).”

A more complicated example of modularity is The Bride Wore Black. It’s broken into five parts, each titled with the name of a victim. Each part contains three sections.

“The Woman” shows the vengeful bride launching a new false identity. The part’s second section, titled with the victim’s name, shows how the murder is accomplished. A third section offering “Post-Mortem” on the victim consists of documents and conversations among the police. Viewpoints are rigidly channeled as well. Each “Woman” section is handled in objective description, while each victim section presents the targeted man as the center of consciousness. The book could be mapped out on a spreadsheet.

The modular layout and rigorous moving-spotlight narration risk choppiness, yielding something like a set of short stories. But the tidy exoskeleton can make the plot seem rigorously organized, even while it masks problems of time and causality. And the very arbitrariness of the pattern creates a sort of meta-curiosity. Like the teasing tables of contents in 1920s and 1930s detective fiction, a Wooolrich checklist of suspects or victims makes us aware of a larger rhythm. How will this pattern be filled out?

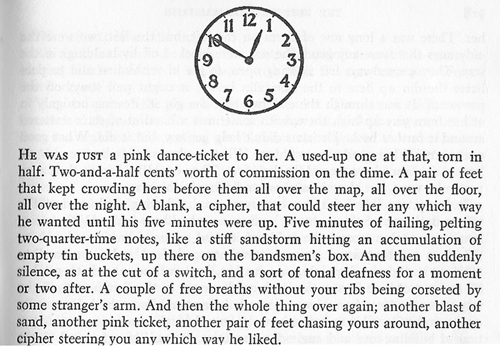

An overarching unity is provided as well by the demands of a deadline (another Hollywood-friendly feature). Thanks to this classic device, Woolrich can use time tags to trigger anticipation and yield a sense of shape. Long before the husband in Phantom Lady gets accused of the crime, the first chapter bears the title, “The Hundred and Fiftieth Day before the Execution,” effectively dooming him from the start. Deadline at Dawn replaces chapter titles with illustrated clock faces to impose a strict structure.

An overarching unity is provided as well by the demands of a deadline (another Hollywood-friendly feature). Thanks to this classic device, Woolrich can use time tags to trigger anticipation and yield a sense of shape. Long before the husband in Phantom Lady gets accused of the crime, the first chapter bears the title, “The Hundred and Fiftieth Day before the Execution,” effectively dooming him from the start. Deadline at Dawn replaces chapter titles with illustrated clock faces to impose a strict structure.

Facing a ticking clock wedded to a clear-cut pattern, we become sensitive to variations among the modules. The victim-centered chapters of The Bride contrast the personalities and private lives of the male victims, along with Julie’s resourceful methods of murder, and the last chapter breaks the three-part format by inserting a flashback dramatizing the fatal wedding. Rendezvous in Black revives the shooting-gallery structure of Black Angel and The Bride, adding a schedule that sets each murder on May 31st of different years. Within this regularity (“The First Rendezvous,” etc.), viewpoints multiply gradually so that the interplay of characters’ range of knowledge becomes richer.

The modular structure shows up in milder ways. Black Alibi tags its chapters with victims’ names and concentrates on one woman’s terror at a time, with each chapter concluding with an exchange among investigators. Deadline at Dawn and Phantom Lady alternate scenes between two characters embarked on parallel investigations. Night Has a Thousand Eyes, in some ways the most ambitious of the books, embeds the checklist within the police investigation. As teams of cops trace parallel leads, their efforts are crosscut with the target under threat, waiting with his daughter and a cop.

A simpler, more poignant, rhyme-and-variations effect is supplied by a prologue and epilogue in I Married a Dead Man. The prologue’s first-person narration, set off from the central chapters’ third-person narration, finishes: “We’ve lost. That’s all I know. We’ve lost, we’ve lost.” An epilogue rewrites the prologue and yields closure: “We’ve lost. That’s all I know. And now the game is through.” In such ways, Woolrich brings the overt compositional symmetry of both “serious literature” and the puzzle-driven detective story into the thriller.

Sweating the small stuff

Henry James, 1913; Cornell Woolrich, ca. 1927.

By the 1920s, ambitious Anglo-American writers in both popular genres and “advanced” literature had fallen under the sway of a new model of the novel. Henry James had argued that if the novel was to be a true art form, it needed more compositional rigor, a patterned architectural solidity. He also advocated for a self-conscious control of viewpoint and a greater commitment to concrete presentation of action. (“Dramatize, dramatize!”) A little later, Joseph Conrad’s books had demonstrated the power of shifting viewpoints and multiple narrators, as well as an emphasis on the power of sight.

Popular writers of the nineteenth century, notably Dickens and Wilkie Collins, had already made use of some of these techniques, as did more highbrow efforts, like Robert Browning’s verse novel The Ring and the Book (1868-1869). But in the wake of James and Conrad, tastemakers erected these principles into strict norms for well-made novels. These precepts were set out explicitly in Percy Lubbock’s The Craft of Fiction (1922), and they were picked up in popular writing manuals as well.

Many mainstream fiction writers (and dramatists) took up the techniques promoted by the James-Conrad-Lubbock tradition. Middlebrow novels employed block construction, played with multiple viewpoints, and included an explicit “exoskeleton” of labeled parts pointing up a self-conscious architecture. Joseph Hergesheimer’s Java Head (1919) spreads nine characters’ viewpoints across ten parallel chapters. Detective fiction wasn’t immune to the new methods. Conrad’s exploration of optical viewpoint has a contemporary counterpart in the Chestertonian grandeur of the mystery story “The Hammer of God” (1910). Father Brown is standing at the top of a church.

Immediately beneath and about them the lines of the Gothic building lunged outwards into the void with a sickening swiftness akin to suicide. . . . When they saw [the church] from below, it sprang like a fountain at the stars; and when they saw it, as now, from above, it poured like a cataract into a voiceless pit.

The writers of High Modernism revised the James-Conrad-Lubbock norms, pushing toward more difficult manipulations of time, viewpoint, and subjective states. Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury assigns different narrational voices to its four-block layout, but these make the story world and the time scheme opaque. (Even if you master the stream-of-consciousness technique, you still have to figure out that one character is called by two names and two characters have the same name.)