Archive for the 'National cinemas: Australia' Category

Rotterdam surprises

Mitra (2021)

Kristin here:

On Saturday morning (8:30 am our time), the International Film Festival Rotterdam will be screening its annual Surprise Film. We’re naturally curious to learn what it is. But Rotterdam comes so early in the year that often we go into its other offerings knowing almost nothing about them. Here are two of the very pleasant surprises from recent days.

Iranian cinema from the Netherlands

Kaweh Modiri, the director of Mitra, was born in Iran but has lived in the Netherlands since he was six years old. Still, he remains concerned with Iranian issues and clearly has been influenced by the flourishing Iranian art cinema of recent decades.

Asghar Farhadi’s success in international festivals and territories has been the most influential instance recently, at least outside of Iran. His plots are often built around conflicts, not between good and bad people, but behind people who clash because of cross-purposes. Late revelations and tortured discussions lead to reconciliations that are not the happy endings of Hollywood films but instead are resigned agreements to admit mistakes and make compromises.

Mitra is such a film, but it is based around more politically based conflicts than Farhadi has used–ones that have life and death consequences for those involved.

The film moves between two settings and eras: Tehran in 1981-82, the years shortly after the ouster of the Shah, and the Netherlands in 2019, the fortieth anniversary of that revolution. The opening is set in 1982, when the heroine, Haleh, receives an abrupt, unexpected telephone calls announcing that her daughter Mitra has been executed. We move then to 2019, when Haleh, now an academic in the Netherlands, addresses a conference on “The Islamic Revolution at Forty.” Soon she is visited by members of “The Organization,” a group aimed at bringing down the current government of Iran. They tell Haleh that Leyla, whose betrayal of Mitra caused her death, has arrived with her daughter in the Netherlands. She goes under the name Sale, having appealed for refuge status. The Organization wants Haleh’s confirmation that Sale is indeed Leyla.

The rest of the plot centers around a shifting relationship, as Haleh vows revenge on Leyla. Her goal is complicated by the fact that she has never actually seen Leyla, having only heard her voice. Nevertheless, she calls Sale and is convinced that she recognizes the woman’s voice, even after nearly forty years. Once they meet, however, Haleh seemingly bonds with Sale and her endearing daughter Nilu. Indeed, Haleh’s attraction to Nilu hints at her possible acceptance of Sale as a substitute daughter and Nilu as a granddaughter.

Interspersed with this story are flashbacks to the younger Haleh’s 1981 experiences, when Mitra, who has joined the resistance in Iran, is still alive. Scenes like a clandestine meeting with Mitra at a crowded market emphasize Haleh’s love for her daughter (top of section).

Modiri expertly lures us into sympathizing with all the characters involved. To the end we remain uncertain as to whether Sale, who after some doubts accepts Haleh as a friend and even as a substitute mother in a new land, is actually the treacherous Leyla. Even if she is, is it worth ruining young Nilu’s life to turn Sale in to the ruthless Organization?

Supporting all this is Haleh’s relationship with her brother Mohsen, who at first seems a somewhat comic, eccentric sidekick but is later revealed to be suffering the effects of torture and lengthy imprisonment in Iran. His exchanges with Haleh initially seem like sibling bickering, but he becomes the moral compass that holds her together as she pursues revenge (see top).

Mitra starts out seeming to be a conventional revenge story, but its moral and personal shifts and surprises lead to a moving and not-quite-resolved ending.

The film has had its world premiere at the IFFR and is due for a May 20 release in the Netherlands. I hope it plays other festivals and travels further, because it is a definite contribution to the continuation of world interest in Iranian cinema. Like other such Iranian films, it had to be made elsewhere (the scenes set in Iran were shot in Jordan), but it carries forward what we have loved about Iranian films.

An Australian surveillance-cam thriller

Jonathan Ogilvie’s Lone Wolf (2021) adopts the new convention of creating a story based largely on surveillance and cell-phone footage. In a frame story Kylie, a Special Crimes Sergeant, bursts into the office of an unnamed Police Commissioner and demands that he watch a video she has secretly compiled from a mass of such footage.

The inner story is seemingly set more-or-less in the present day, but it’s a slightly alternative world in which surveillance has become even more pervasive than it already is. The read-outs in the images reveal that cameras are spying on the characters from such household devices as TVs and smoke detectors. One of these is, ironically, in a bathroom where Winnie sneaks the occasional cigarette by an open window (above). How Kylie gets access to all of these is never explained, and the premise is implausible–especially in scenes built around extensive, undamaged footage which she has somehow managed to extract from a phone that has been through a bomb explosion.

If one stifles such doubts, however, the tale Kylie’s film tells is an absorbing one, full of twists and turns. It centers on Conrad and Winnie, a couple who run a book/video-rental/sex shop and do occasional jobs for underground political groups. They are not the most appealing characters, but they gain our sympathy through their devotion to Winnie’s charming little brother Stevie, who has Down’s Syndrome and an insatiable curiosity about the world.

Australia is soon to host a G20 meeting, and a man from a radical group asks Conrad to set up a “victimless atrocity” in the form of a bomb explosion in a deserted area. At first Conrad refuses, but when offered a large sum, he gives in. Despite the grimness of this plot thread, there is quite a bit of humor in the film, provided by Stevie and by a group of Conrad’s misfit friends who gather to play cards above the shop. The combination of found footage also creates occasionally amusing moments, as when the film-within-a-film includes an instructional YouTube-style video that Stevie has posted or poor-quality footage from an old security camera in the shop that Winnie and Conrad think has been turned off (bottom).

The consequences of the bomb plot introduce a grim twist, but the return to the frame story creates a more gratifying one as Kylie reveals why she has pressed her video upon the Commissioner.

While Rotterdam provided Lone Wolf‘s world premiere, it has a distributor in Australia, though its August, 2020 release was postponed by the pandemic. Ogilvie hopes it will have wide theatrical play after a possible in-person premiere at the Melbourne International Film Festival this coming August.

Again, thanks to Gerwin Tamsma, Monika Hyatt, Frédérique Nijman, and their colleagues at the International Film Festival Rotterdam for allowing us to discover these surprises!

Lone Wolf (2021)

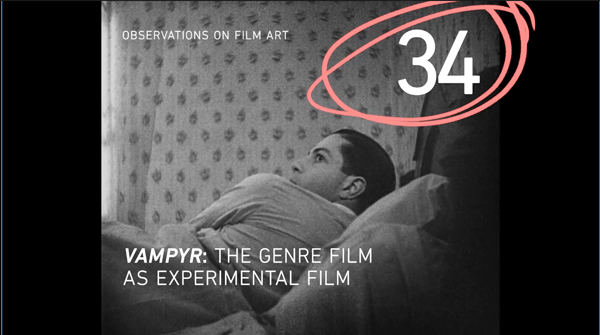

VAMPYR and more on the Criterion Channel

DB here:

Busy times! I’ve gone back to teaching this semester, and we’re revising Film History: An Introduction. So we’ve been kept from posting as often as we’d like. For the moment just let me signal the newest additions to our Observations series on the Criterion Channel.

In recent installments, Kristin offers an analysis of how film technique suppresses and reveals story points in Jane Campion’s An Angel at My Table. A free extract is here.

Jeff Smith traces how mise-en-scene techniques, especially settings, yield feminist implications in Gillian Armstrong’s My Brilliant Career. Sample it here.

This month, as you see above, I’ve offered a consideration of Vampyr as an experimental film. Again, you can see a clip.

Thanks to the people who’ve told us they enjoy our offerings, now running for nearly three years, longer than Joanie Loves Chachi. Thanks as well as to the group that makes it possible: Peter Becker, Kim Hendrickson, Grant Delin, Erik Gunneson, and the rest of the team in Madison and Manhattan.

With the Channel sponsoring an ambitious seventeen-film Burt Lancaster series, you might check out this entry on Brute Force.

Torino tour of world cinema

Synonymes (2019).

Kristin here:

After visiting museums on the one free day we allowed ourselves in Turin before the festival began, we launched into viewing films from around the world. Here are three of the best we’ve seen, to add to the ones David has discussed.

Synonymes (France/Israel/German, dir. Navad Lapid)

Israeli director Navad Lapid has become a familiar figure for us as we have visited past festivals in Vancouver. We blogged about his Policeman in 2011 and The Kindergarten Teacher in 2014. His latest film raises his profile considerably, having won the Golden Bear at Berlin and had its North American premiere at Toronto. (Ozon’s By the Grace of God, which we blogged about from Vancouver, won the Silver Bear.)

Synonymes started with an abrupt chase, with the camera bouncing about as it follows our hero, Yoav, as he dashes through the streets of Paris (above). I was worried that this loose style of shooting would dominate, but Lapid has something more disciplined involved. The unfastened camera is usually used for exteriors, while interiors are made up of static shots.

He arrives at a large empty flat that someone has loaned him, where the heat has apparently been turned off. He proceeds to take a cold shower, and, having neglected to lock the door, he finds his backpack and sleeping bag stolen. He is left naked with no possessions whatsoever. A wealthy young couple from downstairs rescue him from hypothermia and become fascinated with him, taking him in briefly. Émile gives him money, as well as clothes. He holds up a long series of colorful shirts, which he himself apparently never wears, judging from his own muted wardrobe.

Lapid matches these colors to the decor, especially the distinctive, bright mustard-hued overcoat that Yoav wears through much of the film. The coat makes him easy to spot and marks him as an outsider among the more conventionally dressed Parisians around him (see top).

We soon learn that he is fleeing from his oppressive life in Israel and wants to become a Frenchman as soon as possible, refusing to speak anything but French despite his elementary grasp of the language. (The title comes from his habit, when wandering around alone, of muttering a series of words with similar meanings.)

There’s not much of a goal operating here, apart from Yoav’s increasingly strained efforts to turn himself into a Frenchman and abandon the violence inculcated into him by his time in the Israeli army. His one conventional job is as a security guard at the Israeli consulate. His violent outbursts and willfully eccentric behavior increase as the film goes along.

The rather episodic film revolves around the driven performance of Tom Mercier, an Israeli theater student who knew no French and, remarkably, is making his film debut here.

Kino Lorber has released Synonymes (as Synonyms )in North America. For a plot summary and a list of theaters where it has played and will be playing into January of next year, see the company’s webpage.

True History of the Kelly Gang (Australia, dir. Justin Kurzel)

Bushranger films, of which True History of the Kelly Gang is one, are more or less the Australian version of American westerns. The tale of Ned Kelly and his gang is almost a mini-genre in itself, going back to what is claimed to be the world’s first feature film, The Story of the Kelly Gang (1906, dir. Charles Tait, partially surviving).

Justin Kurzel adopts a fresh take on the familiar Kelly tale, which is as much myth as fact. He based his film on Peter Carey’s novel of the same name, which won the Booker Prize and many other awards. By adding “True” to his title, Carey both acknowledged the fact that he was embroidering the national legend as much as adhering to the facts.

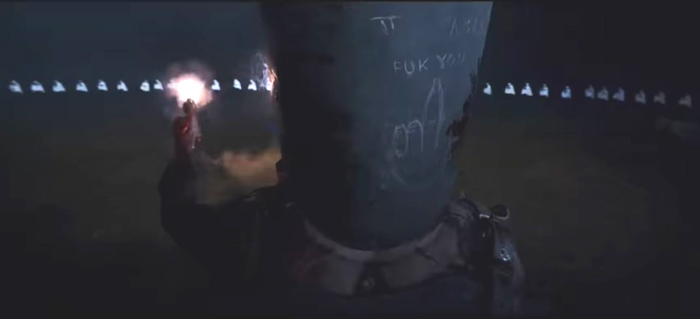

Kurzel does the same. A title appears on the screen: “Nothing you are about to see is true.” All of the words besides “true” fade out, and the rest of the film’s title fades in beside it. Those of us not steeped in Australian history and culture will not be able to fill in the inauthentic parts, but it doesn’t really matter. It’s a gripping story nonetheless.

The film opens when Ned is a boy, living with his mother Ellen and siblings in a bleak part of the bush consisting mainly of stubby dead trees (above). Although an honest lad to start with, he is drawn into the family’s long-time opposition to the local constabulary and military forces. Despite her fierce love for her family, Ellen sells him into apprenticeship to a putative merchant and herder (played with not quite too much gusto by Russell Crowe). The man turns out to be a highway robber, and Ned is reluctantly pushed toward a life of crime.

The film follows the novel in using a voiceover narration by Ned, reading from a diary purporting to be for his young daughter after his inevitable demise. (In fact the figures of the wife Mary and the daughter are part of the tale’s embellishment.) Indeed, we are nearly always in his presence and are led to sympathize with him because almost everyone around him except Mary exploits him.

The film is visually impressive, including some shots that leave one wondering how they were accomplished. At intervals there are fast drone shots above the sea of dead trees as Kelly and others ride horses through the landscape. One shot at night features an immense pool of light from above that moves smoothly with the horseman, keeping him visible as the stark gray trees appear from and disappear into the inky surroundings.

The climactic shootout between Kelly’s gang of four men in home-made armor and a large posse approaching from the distant background provides an unforgettable image. The last man standing, Kelly himself, back to camera, fires at a line advancing figures. They appear spread across the screen as tiny white figures–looking distinctly like Ku Klux Klan men in full garb. (See bottom.)

True Story of the Kelly Gang contains considerable strong profanity and violence, which would seem to warrant a risky hard-R rating in the US. Nevertheless, just before the film’s world premiere at Toronto, IFC acquired the North American rights to the film for a reported seven-figure sum, bidding against three other distributors. IFC will evidently release it in 2020. (The first trailer has just been posted on Youtube, but there is currently no mention of the film on the IFC website.)

Noura’s Dream (Tunisia/France/Qatar, dir. Hinde Boujemaa)

Increasingly female directors working in Middle Eastern and North African countries are gaining a foothold in the international film market. Recent notable films have been Saudi director Haifa Al Mansoor’s The Perfect Candidate in competition at Venice and Nadine Labacki’s Lebanese film Capernaum, Jury Prize winner at Cannes in 2018.

Tunisian director Hinde Bujemaa’s Noura’s Dream centers on a woman with three children who is awaiting an imminent divorce from her incarcerated husband, Jamel, so that she can marry her lover, a car-repairman, Lassaad. Meanwhile she is working in a laundry to enhance her government checks and support her family (above).

Though Tunisia is somewhat more liberal than other Muslim countries, Noura still faces traditional prejudices. In the opening scene, an official tries to talk her out of the divorce for the sake of her children–as if living with an abusive criminal for a father is more desirable than having a kinder stepfather.

Jamel is released unexpectedly early, and Noura must live with him for the few days until the divorce is final. She pretends to be considering staying with him, despite the fact that he returns to his criminal activities and abuses his family, at one point throwing them out of the house (above). As Bujemma points out in a Variety interview, however, Jamel is not all bad, not taking the option of betraying to the police Noura’s adultery with Lassaad, still a criminal act in Tunisia.

In a way Noura’s Dream seems to reflect the considerable impact that Asghar Farhadi’s Oscar-winning films have had on other directors in the region. The situation of an impending divorce recalls A Separation, yet Farhadi’s films tend to have quiet, “everyone has his reasons” plot arcs with twist revelations and moral ambituities. Here, telling such a story and eager to display the biases against women in Tunisian society. Bujemma takes a more melodramatic approach. Jamel is an unrepentant criminal and Noura is a brave, determined woman struggling to separate herself and her children from him. Lassaad is a decent fellow nevertheless ultimately driven to reject her when she shows no signs of leaving Jamel.

It’s a film that effectively builds up considerable sympathy for Noura, played by prominent Middle-Eastern star Hind Sabri, and withholds hope, or possible hope, until the last shot.

Noura’s Dream has played several festivals, including Toronto, London, and now Torino and has releases in Europe and its native country, but there is so far no North American distributor.

The Horror Thread

As David mentioned in our previous post, the Torino Film Festival includes a retrospective program each year. This time it was horror films, from Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari to Roy Ward Baker’s Dr Jekyll & Sister Hyde (1971, UK). I fit some of these into my schedule in between the new films.

There were 35mm prints of I Walked with a Zombie (1943, Jacques Tourneur), The Masque of the Red Death (1964, Roger Corman) and The Devil Doll (1936, Todd Browning), among the films I saw. The DCPs of The Body Snatcher (1945, Robert Wise) and The Innocents (1961, Jack Clayton), the latter shown immediately after the former, offered two gorgeous examples of black-and-white cinematography. In all the retrospective included 36 films, many of them probably being viewed by Italian attendees for the first time in their original languages, rather than dubbed versions.

We wish to thank Jim Healy, Emanuela Martini, Giaime Alonge, Silvia Saitta, Lucrezia Viti, Helleana Grussu, and all their colleagues for their kind help with our visit.

For more Torino images, visit our Instagram page.

True Story of the Kelly Gang (2019).

Wisconsin Film Festival: Cutting to the chase, and away from it

Nocturama (2016).

DB here:

Despite my recent jab at D. W. Griffith, I gladly give him credit for making crosscutting a central technique of narrative cinema. Using editing to switch our attention from one story line to another is a fundamental resource of moviemaking everywhere.

Crosscutting is most apparent in those passages of quickly alternating shots that build tension during chases and last-minute rescues. That’s a prototype of what we credit Griffith with consolidating. But crosscutting is used outside such climactic stretches. Hollywood silent features often crosscut story lines throughout the film, without pressure of a deadline and without much happening in some lines of action. It seems to be a way that filmmakers found to keep the audience aware of many story strands.

Crosscutting is a cinematic version of a very old narrative strategy, that of alternating presentation. Once you have several story lines, you can switch among them. Homer does this in the Odyssey, interweaving Ulysses’ wanderings, Telemachus’ efforts to find him, and Penelope’s holding off the suitors.

Homer initially handles these lines in large blocks, in separate “books.” After attaching us to Telemachus in Books 1-4, Homer shifts us to Ulysses for a long stretch. Such interlacing can be found in medieval narrative too, and of course it dominates modern novels, with chapters shifting among action lines and character viewpoints.

Crosscutting large chunks can give way to shorter bursts. Ulysses’ travels occupy several books, but as he approaches Ithaca, Homer interrupts Book 15 to switch back and forth between him and Telemachus, also headed for home. In cinema, this sort of accelerated crosscutting, often driven by a deadline, has become identified with Griffith’s The Lonely Villa (1909), A Girl and Her Trust (1912), and other Biograph shorts. He lifts the principle of crosscutting to a vast scale in his features. The Birth of a Nation (1915) alternates North and South, home front and battlefront, carpetbaggers and Klansmen in a novelistic fresco.

Crosscutting usually implies some degree of simultaneity. While Telemachus searches for his father, Ulysses leaves Calypso and the suitors run riot in the palace. The notion of actions taking place at more or less the same moment is especially important in chases and last-minute rescues.

As a plot reaches its climax, there can be a sort of site-specific crosscutting too. Once Ulysses and Telemachus have joined forces to slaughter the suitors, Homer’s narration sometimes switches among areas of the fight, as in the battle scenes of the Iliad. While father and son hold off the suitors in the main hall, two servants capture one suitor in a storeroom. We recognize this technique of adjacent alternation when novels and films gather all the major characters in one spot for the climax and shuttles among them.

Crosscutting remains a basic filmmaking tool for most movies on our screens. Where would the Fast and Furious franchise be without it? But some contemporary filmmakers have made fresh uses of the technique. In Inglorious Basterds, Tarantino adopts the big-segment option, alternating lengthy blocks of action before using faster crosscutting when characters converge at the climax. Christopher Nolan has experimented with various tactics, including crosscutting different phases of the same action (Following) and crosscutting among embedded segments, dreams within dreams (Inception).

So there are still lots of options out there to be explored. Just look at some films shown at our Wisconsin Film Festival. Beware, though, of light and heavy spoilers.

Attachment plus anxiety

Frantz (2016).

At one end of the spectrum: Must you always use crosscutting? Wigilia, a charming short feature by Graham Drysdale, suggests not.

It’s built on two Christmas eves a year apart. In the first, a Polish refugee who cleans house for a brusque businessman is alone for the holiday and in his apartment prepares the traditional holiday meal—not for herself but for her absent family. She’s interrupted by the businessman’s vaguely hippy brother, and the two learn about each other as they share the meal. In the second evening, after the businessman has left the apartment to his brother, she returns and they bond more intensely.

Apart from an inserted dream sequence, we stay within the apartment. This concentration derives from the production circumstances; Graham explains that he was given a chance to make the film in short order, and to keep it manageable he came up with the idea of limiting the locale. He shot 53 minutes of footage in five days in the apartment, then did the two final scenes in two days. The narrowly focused drama, with many lines improvised, has no need for the free-roaming tactics we associate with crosscutting.

Crosscutting tends to give us a fairly unrestricted range of knowledge; often we know more than any one character. In The Girl and Her Trust, the telegraph operator holding off the robbers can’t be sure that her boyfriend is rushing to her rescue, and he can’t know how close the robbers are to seizing her. Alternatively, when we’re mostly restricted to one character, we don’t find a great deal of crosscutting.

That’s the case in François Ozon’s Frantz, a remake of Lubitsch’s Broken Lullaby (1932), also shown at WFF. Anna’s fiancé Frantz has been killed in the Great War. Out of sympathy his parents have taken her in and treat her as a daughter. But when she sees Adrien, a melancholy Frenchman, haunting Frantz’s grave, she gets curious. Most of the ensuing film is restricted to what Anna learns,

Adrien visits the family. Flashbacks lead us to think he’s what he hesitantly claims to be: a friend of Frantz from prewar Paris. But he has been pressed to tell the parents what they wished to hear. Adrien actually came to the village to beg their forgiveness for killing Frantz on the battlefield, where they met for the first time. Although we surely have reservations about the sad, apprehensive young man, we don’t learn the truth until Anna does, at about the midpoint of the film’s running time. By this time she has fallen in love with him.

There is some alternation of viewpoint in the film. A few scenes attach us to Adrien during his stay in the village, chiefly when he confronts bitter locals who still consider France their enemy. Still, these scenes don’t give us much direct information about the true backstory. And after Adrien has left and Anna has sought to keep the parents in the dark about the past, we remain attached to her. No crosscutting shows us Adrien’s return to France and his life there. As a result, we’re able to feel curiosity and suspense when Anna decides to track him down. The revelation of his civilian life raises a set of unexpected conflicts.

Both Wigilia and Frantz show that avoiding crosscutting can be a powerful way to keep our attention fastened on characters, the better to let their words and behaviors, as well as their inner lives, get primary emphasis. Crosscutting yields a panorama, while refraining from it can aid portraiture.

Crosscutting as usual

The Student (2016).

More toward the center of the spectrum lies ordinary crosscutting, the alternation among scenes that provide a broad perspective on the action. In Arturo Ripstein’s Western Time to Die (1965), the plot alternates between scenes featuring the returning convict Juan Sayago and episodes showing the reactions of different townsfolk—chiefly the sons of the man he killed. We also learn of efforts from women in the town to prevent the sons from taking revenge. This “moving-spotlight” narration isn’t perfectly omniscient, though. The plot gradually fills in information about what led up to Sayago’s crime, while revealing that the sons’ mission would amount to avenging a dishonorable father.

A similar sequence-by-sequence approach is seen in The Student, aka The Disciple, a Russian film by Kirill Serebrennikov. A fanatical teenager has become the scourge of the classroom, barraging teachers and pupils with Bible quotations and denunciations of bikinis. His mixed-up fundamentalism, which leads him at one point to challenge evolution by donning a gorilla outfit, is unpredictable and a pure power trip, Biblical bullying.

His mother can’t manage him, the administrators are reluctant to take stern action, and the school priest sees him as a potential recruit to the clergy. Only one teacher, Elena, challenges him with a mix of humor and sympathy. But to combat his increasingly wild behaviors, which include making himself a full-size cross which he can stretch out on, she too sinks into Scripture. She hopes to quote the Bible back at him and dislodge his dogmatism, but she too becomes obsessed and estranges herself from her boyfriend. Meanwhile, Venya gets his one true disciple, a limping underdog, and his campaign against homosexuality, science, and secularism turns violent.

A good part of the narration locks us in to Venya’s Dostoyevskian ferocity, thanks to a restless use of the “free camera” in lengthy following shots. (The film has only about 150 shots in 113 minutes.) But we do range more widely to get a broader view. The moving spotlight shows the mother’s frantic consultations with school officials, and Elena’s clashes with them, as well as with her boyfriend. Still, the climactic scene, which assembles all but one of the characters in a single meeting, has no need of a broader view. Like Wigilia, The Student draws its final power from drilling down into a confrontation around a table.

Gaps and folds in time

Killing Ground (2016).

Griffith rang many changes on his last-minute-rescue template, and one of the most startling occurs in Death’s Marathon (1913). A dissolute husband, bored with his life, decides to commit suicide and notifies his wife by phone. She calls the family friend, who races to prevent the death. Surprise: He’s too late.

A hundred-plus years later, crosscutting builds and then deflates suspense in the Romanian film Dogs, by Bogdan Mirica. There are two protagonists: Roman, a city fellow who has inherited his grandfather’s idle farm, and Hogas, the police chief. Both face off against sadistic hoodlum Samir and his thugs. A human foot has popped up (literally, in the first shot), and Hogas tries to trace its owner, while Roman decides how to dispose of the farm. Samir explores other possibilities, none very savory.

At first we’re restricted to Roman, who is frightened by distant lights and gunshots out on the property, and Hogas, who doggedly pursues his investigation. The alternation between them keeps Samir offscreen for some time. When he surfaces in a suspenseful drinking bout with Roman, and when Roman’s girlfriend comes to pay a visit, the threats start building.

The climax starts out as pure Griffith. Mirica crosscuts Roman’s drive back to rescue his girlfriend, Hogas’ pain-ridden walk to the farmhouse, and Samir’s ominous approach to the isolated woman. Interestingly, the pace of the cutting doesn’t much accelerate in these last moments; there isn’t a lot of alternation, and the emphasis is on prolonged actions (Hogas’ trudging pace, interrupted by coughing up blood, and Samir’s laconic dialogue with the girlfriend).

By the time Hogas arrives, he finds he’s too late. The conventional mystery and suspense of the first stretch are undercut by showing us only the eerie aftermath of a violent climax. Art-cinema norms can de-dramatize crosscutting, but the maneuver remain a revision of what Griffith tried for in 1913.

Three years after Death’s Marathon, Griffith showed the possibility of crosscutting radically different time frames. Intolerance (1916) interweaves four historical epochs while using crosscutting within each one as well. Since then, crosscutting has sometimes been used to juxtapose past and present (The Godfather Part II, The Hours), or alternative futures (Sliding Doors), or a real story and a fictional one (Full Frontal). Interestingly, Griffith is a bit more daring than these directors. These films usually alternate sequences or entire blocks. At first Intolerance does that too, using titles to mark the shift among its four eras. But as the film reaches its climax, Griffith cuts freely from one period to another. These shot-to-shot time shifts, jumping centuries in the burst of a cut, remain an audacious formal discovery.

In all these examples, we’re cued to realize when we move to another period. But Killing Ground, a grueling Australian thriller by Damien Power, doesn’t announce its time-shifting. It exploits our default assumption that crosscutting implies more or less simultaneous action.

At first Killing Ground does give us rough simultaneity, alternating between the yuppie couple, Ian and his fiancée-to-be-Sam, and a pair of gun-loving locals. But then the couple make camp near another family’s tent.

Through careful use of eyeline matches and other continuity cues, the narration welds together actions that are actually taking place at different times. The family’s evening meal and their foray into the woods happen well before Ian and Sam arrive, but the cutting implies that the two groups are living side by side.

Like Griffith, at moments Power shifts between the two periods on a shot-by-shot basis. Small disparities, like a baby bonnet and the placement of the campers’ vehicles, accumulate. By the time Ian follows one of the psychopaths into the woods, we realize that earlier events have been salted through the present-time action, the better to delay revealing the family’s fate. From then on, orthodox crosscutting takes over as Ian runs for help and Sam tries to hold the rampaging peckerwoods at bay.

The kids aren’t alright

At the distant end of the spectrum, how about building a whole movie out of full-blown crosscutting? A sustained example at WFF was Bertrand Bonello’s Nocturama. (Major spoilers ahead.)

For the first fifty minutes or so, we follow nine young people silently threading their way through Paris. They ride the Métro, pace along the street, pair up, separate, crisscross, and assemble at four sites—a line of parked cars, an office building, a Ministry, a statue of Joan of Arc. They’re setting bombs.

We can identify them only through their looks and behaviors. David and Sarah touch fingers fleetingly on a train. We learn from flashbacks that Samir and Sabrina are sister and brother, and their friend is the younger African Mika, all presumably from emigrant families. Flashbacks also show them meeting to plan their action and, once set on course, dance the night away.

There’s an unexpected shooting, but the bombs go off more or less as planned. The group assembles in an upscale department store to meet another confederate, the security guard Omar who will host them overnight. This brief “nodal” moment of unification melts away. Crosscutting follows them as they wander from floor to floor in a parallel to their passages through Paris.

The first section merges the art cinema’s best friend, the prolonged walk, with a thriller-based suspense: we don’t really know what they’re up to until we see a pistol at around 18 minutes and bomb materials somewhat later. The threads knot when we see a quick montage of the bombs.

This fine-grained crosscutting looks ahead to the fragmentary handling of the action in the department store, where the moving spotlight shifts rapidly as the conspirators disperse, assemble in pairs or trios, and disperse again.

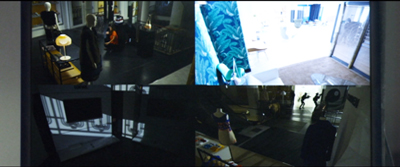

Crosscutting is the principal way filmmakers imply simultaneous action, but a lesser option, often favored by Brian De Palma, is the split screen. Bonello uses this device to show the result of the bombings. The shot looks forward to the quiet surveillance-camera display in the security office as the police prowl the shopping aisles. We see the kids moving from quadrant to quadrant, with an occasional flare marking a nearly soundless kill.

The terrorists’ motives are barely sketched, and they’re a cross-section of middle-class and working-class kids. Some are unemployed, others have low-end jobs, while others are on track for professional careers. A flashback shows several, perhaps meeting for the first time, while waiting for job interviews. The film’s second large part paints them as victims of consumer lust as they try on upscale fashions and make-up, but the point isn’t hammered home. To some extent they’re just killing time in what they think is a safe house.

Nocturama‘s crosscut climax balances, in more condensed form, the first section, as the conspirators are discovered by the police. At one point, an innocent who has come upon them by accident gets more emphasis than the gang members. His final moments are replayed through multiple viewpoints, as if the stranger’s fate drives home to them what death looks like up close. Soon enough each one will know exactly.

It might seem the height of film nerdery to join up films seen at a festival through their different uses of one technique. But is it any more of a strain than those journalistic accounts of how a batch of festival choices reflects The Way We Live Now? Every Berlin or Cannes or Toronto seems to bring forth think pieces looking for a common thread among radically different films, hoping to find today’s social mood in movies begun perhaps years before? Like most zeitgeist readings, they’re pretty easy to whip up.

But technical choices are more concrete than hints of the mood of the moment. Moreover, if you’re interested in cinema as an art, it can be enlightening to reveal the variety of creative options that are still available. The art may not progress, but our understanding of it can. And it’s heartening to find filmmakers refreshing traditional techniques to give us powerful experiences.

Just as important, studying how our contemporaries find new possibilities in something as old as crosscutting can encourage ambitious filmmakers today. The menu is open-ended. There’s always something new, and rewarding, to be done.

We had a wonderful time at this year’s Wisconsin Film Festival. Thanks to all the people and institutions involved, and especially the programmers Jim Healy, Mike King, and Ben Reiser. Each year it just gets better.

Wigilia is currently streaming on Amazon. Nocturama has just gotten a US distributor, the enterprising Grasshopper Film.

Good discussions of interlaced plotting in medieval tales are William W. Ryding, Structure in Medieval Narrative (Mouton, 1971) and Carol J. Clover, The Medieval Saga (Cornell University Press, 1982). Yes, it’s Carol “Final Girl” Clover.

For Tarantino’s use of block construction and time-bending, go here. We discuss Nolan’s penchant for crosscutting in this entry and that one, and at greater length in our e-book on his work.