Archive for the 'National cinemas: Austria' Category

Vancouver 2018: Panorama of the Rest of the World, the sequel

Seder-Masochism (2018)

Kristin here:

The Vancouver International Film Festival is over, but we still have films to talk about. Here are four, and David and I will probably post another blog apiece. Between Venice and Vancouver, we have seen a lot of great and very good films recently. Once again, the claims of the death of cinema are robustly refuted.

Dogman (Matteo Garrone, 2018)

Garrone is best known outside Italy for his 2008 film Gomorrah. While that film was about gangs and organized crime in Naples, Dogman centers around a shifting relationship between a meek-mannered dog/boarder/groomer who has fallen in with a volatile, enormous local thug.

The title emphasizes the honest side of Marcello’s life, and we see some comic scenes of him with dogs. Soon, however, it is revealed that he sells cocaine on the side and sometimes acts as a getaway driver for thefts committed by the monstrous ex-boxer, Simoncino. Eventually he even takes the fall for a robbery and spends a year in jail in Simoncino’s place.

We’re clearly intended to side with this sad sack. After one house robbery, Simoncino’s partner reveals that he put a dog in the freezer to keep it quiet. Marcello sneaks back in and, a suspenseful and remarkable scene, attempts to revive the frost-covered animal. He also dotes on his daughter and seemingly pursues his criminal activities in order to be able to take her on “adventures,” including scuba-diving.

Despite this sympathetic side, however, Marcello never seems to consider giving up crime; he’s mainly interested in getting his fair share of Simoncino’s ill-gotten gains. Although the film is continually entertaining and suspenseful, its ending is somewhat disappointing. We are left knowing what Marcello’s probably fate will be, but we have little sense of his attitude toward what has happened.

Marcello Fonte, looking like a rather emaciated version of the comic Toto, won the Best Actor prize at the Cannes Film Festival.

Magnolia has the US rights and plans to release Dogman in 2019.

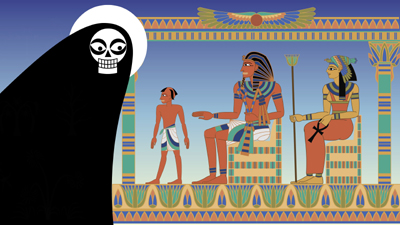

Seder-Masochism (Nina Paley, 2018)

Seder-Masochism is the only US film I’ll be writing about from Vancouver. (We tend to skip US films here, since we assume we can see them in the US.) Paley’s not part of the Hollywood establishment or even the mainstream indie scene. It’s not easy to see her wonderful animated films on the big screen, but their bright colors and imaginative graphics deserve to be shown that way.

Seder-Masochism is Paley’s second feature, after Sita Sings the Blues (2008). She does all the animation herself, holed up, as she puts it, like a hermit with her computer. She also avoids the standard distribution methods for indie films, because she’s an opponent of copyright for artworks. She provides open access to her films, initially at festivals and then online. (For more on this, see my transcript of a Q&A I helped run when Sita played at Ebertfest in 2008.)

Seder-Masochism is Paley’s second feature, after Sita Sings the Blues (2008). She does all the animation herself, holed up, as she puts it, like a hermit with her computer. She also avoids the standard distribution methods for indie films, because she’s an opponent of copyright for artworks. She provides open access to her films, initially at festivals and then online. (For more on this, see my transcript of a Q&A I helped run when Sita played at Ebertfest in 2008.)

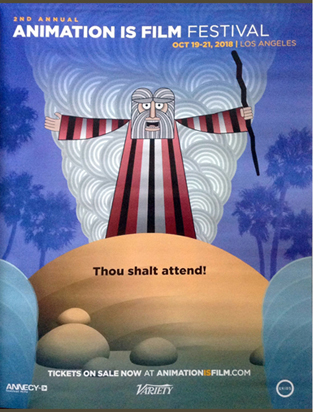

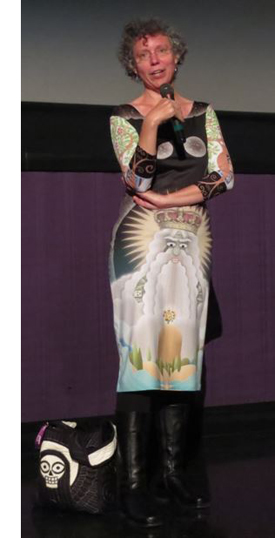

I should say that no one should assume from the title that this film is grim and/or anti-Jewish. On the contrary, it’s a witty exploration of the Exodus myth and its historical links to the decline of early goddess worship in favor of all-powerful male gods in monothesism. The framing situation is a conversation between Paley and her father conducted shortly before his death, with Paley as a small goat and her father as God (see top).

I should say that no one should assume from the title that this film is grim and/or anti-Jewish. On the contrary, it’s a witty exploration of the Exodus myth and its historical links to the decline of early goddess worship in favor of all-powerful male gods in monothesism. The framing situation is a conversation between Paley and her father conducted shortly before his death, with Paley as a small goat and her father as God (see top).

This conversation is a mix of humor and serious points about Judaic traditions and particularly the celebration of Passover. The story of Moses and the Exodus is rendered in much the same way she treated the tale of Sita and Rama from the Hindu epic, the Ramayana–with musical numbers. Moses is introduced with “Moses Supposes,” from Singin’ in the Rain, and, inevitably, there is a “Go Down, Moses” episode. Unlike Sita, where blues songs were used throughout, the musical pieces in Seder are wide-ranging, culminating in a brilliant three-minute summary of the history of the territory which is now Israel, done to “This Land is Mine,” the song written to the theme of Otto Preminger’s Exodus. (The sequence, as well as several other excerpts from Seder are available on YouTube.)

The sequences set in ancient Egypt are generally accurate. I was amused by the fact that the animal and bird hieroglyphs in the background inscriptions moved rhythmically during the musical numbers, and the Hathor heads on the sistrums sang along. Using Hathor, the cow goddess, as the golden calf was an inspiration.

Seder-Masochism got the most enthusiastic applause I heard at the festival, partly because the filmmaker was present (in her custom Seder dress). There were Sita fans in the audience, and one Jewish lady asked how she could get a copy to show her 12-year-old daughter. Paley replied that the film will continue to play festivals and probably be available on the fim’s website for download in the spring.

In the meantime, watch for it at festivals–or let the organizers know that you want to see it on their schedule. We were happily surprised to see a full-page ad for the Los Angeles Animation Is Film Festival (October 19-21) in the current Variety (above left) and illustrated by an image derived from the film. You may find others.

Styx (Wolfgang Fischer, 2018)

I was surprised to discover that so far Austrian director Wolfgang Fischer’s Styx has not been picked up by a North American distributor. It seems like the sort of film to appeal strongly to audiences. It’s protagonist is a strong, ultra-competent woman, it has a riveting plot full of suspenseful situations, and it deals with the immigrant crisis facing Europe.

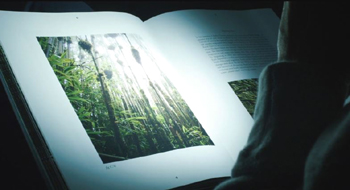

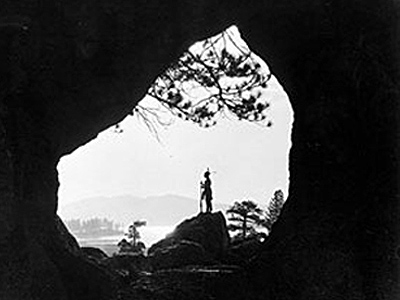

A long portion of the film contains no real dialogue. The opening sequence occurs at the scene of a traffic accident where the heroine, Rike, is established as a doctor as she heads the team treating the victim. Cut to her provisioning her yacht for a solo trip. A lovely shot of a compass “walking” its way down a map establishes her route and distant goal: Ascension Island (see bottom). Her departure reveals that her starting point is Gibraltar (above). From that point, we watch Rike expertly dealing with her vessel, enjoying the solitude of the ocean, and reading about Darwin’s activities on Ascension.

Apart from a few overheard commands during the initial emergency scene, there is no dialogue until Rike makes radio contact with a nearby commercial vessel which warns of a serious storm approaching. A tense scene of her struggle to deal with the storm at night creates the first major suspense of the film. From her arrival in an ambulance in the opening sequence, actress Susanne Wolff is present in every scene, and as an experienced sailor she was able to handle the yacht and do without a stunt double.

Rike comes through the storm without difficulty, but a leaky vessel crowded with African immigrants striving to get to Europe is visible in the distance. Ordered by a coast-guard official not to interfere, she uneasily waits for a sign of a rescue vehicle that still has not shown up after hours of waiting. One teen-aged boy manages to swim from the derelict ship, and he complicates her situation considerably. The dilemma remains: try and take the rest of the refugees on board her small yacht or wait for the promised rescue.

The remainder of the film generates unrelieved suspense as Rike debates what to do and Kingsley begs her to rescue his sister, still abroad the sinking boat. A non-actor discovered in a school in Nairobi, Gedion Oduor Weseka is convincing and touching as the desperate boy.

Nearly all of Styx was shot at sea, with Fischer’s small crew mounting their camera hanging off the sides of the boat and scrambling to keep out of sight during filming. No special effects were used for the storm and other ocean scenes. At intervals some impressive extreme long shots from overhead, presumably taken by drones, emphasize the yacht’s isolation in the vastness of the sea.

The film is riveting from beginning to end. I recommend it, though at least for North America, festival screenings are probably the main places where it can be seen. Perhaps it will eventually be available on streaming services. In some European countries, it will probably be released theatrically.

Transit (Christian Petzold, 2018)

The central premise of Transit resembles that of Casablanca. A group of émigrés are desperately awaiting the letters of transit that will allow them to flee fascist Europe for North America. In this case they’re in Marseille rather than Casablanca, and the plot focuses on one rather ordinary, non-heroic man–or so he seems. Our protagonist is Georg, a Jew lingering in Paris as the authorities arrest fugitives. The authorities are working for a fascist regime, though Nazis are never mentioned specifically.

Moreover, the settings and costumes are mainly modern. Early on Georg flees a round-up through allies covered with spray-painted graffiti (below), and the vehicles in the streets are all contemporary models. Petzold’s avoidance of period mise-en-scene sets up a strange, somewhat surrealist world, but it also invites us to consider the parallel with current social problems.

By chance Georg gains possession of the manuscripts and papers of Weidel, a well-known author who has met a bloody end in a cheap hotel room. Fleeing to Marseilles with a wounded fellow Jew who dies along the way, Georg visits the Mexican consulate and is mistaken for Weidel, whose transit papers for him and his estranged wife have been approved. Naturally Georg accepts the error. While waiting for the papers to come through, he befriends his dead friend’s widow and her son, immigrants to Europe from the Maghreb, and by chance encounters and falls in love with Weidel’s wife (who does not realize her husband is dead), hoping to use the two letters of transit to escape to a new life with her.

Between the inexplicable modern settings and costumes and the extraordinary coincidence of this meeting, the film is far from being realistic. It reminded me of the late films of Manoel de Oliveira (see our earlier reports on Doomed Love, Eccentricities of a Blonde-Haired Girl, The Strange Case of Angelica, and Gebo and the Shadow), with touches of Bresson in the situation and the acting, particularly of Franz Rogowski as Georg. But Petzold is not simply imitating these and other directors. Transit is a remarkable, original film, one of the best we saw at Vancouver.

Transit has been acquired for US distribution by Music Box for an early 2019 release. Definitely keep an eye open for a screening near you, most likely in festivals and large-city art houses and perhaps eventually on streaming..

Thanks as ever to the tireless staff of the Vancouver International Film Festival, above all Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, Shelly Kraicer, Maggie Lee, and Jenny Lee Craig for their help in our visit.

Snapshots of festival activities are on our Instagram page.

Styx (2018).

HKIFF: Firebirds soar and MOTHER returns

Firebird Young Cinema Award winners and jury members, Hong Kong International Film Festival, 2014. For photos of all winners and jurors, go here.

DB here:

As my Hong Kong trip nears its end, I realize I’ve been too busy to blog properly. So when the wobbly net connections in my hotel permit, I’ll offer some quick entries on things I’ve seen and done.

Prizing movies

First, the big news. The festival hosts several annual awards. There are prizes from SIGNIS, the World Catholic Association for Communication, and FIPRESCI, the International Federation of Film Critics. The festival has established its own prizes as well: for best documentary, best short film, and for young filmmakers. The complete list of winners is here.

The jury for the Firebird Young Cinema Competition consisted of Bong Joon-ho, Karena Lam Ka Yan, Christopher Lambert, and me. We faced some hard choices, but we finally settled on three winners.

Special Mention went to Forma, by Ayumi Sakamoto. It’s a slow-burning thriller shot in mostly distant long takes and displaying a backward-looping time scheme that makes you rethink the first half. It also displays one virtue of video production: its crucial scene consists of a single shot, only apparently haphazardly composed, that lasts over 22 minutes!

We gave the Jury Prize to Tsuto Tetsuichiro’s Tale of Iya. It’s an extraordinarily ambitious film shot in 35mm Scope in a great variety of locales and weather conditions. It’s about the rigors of rural life, the need for ecological understanding, and a young woman’s growing awareness of her duties to her past. Some scenes recalled the great Japanese widescreen films of the 1950s and 1960s.

The top prize, the Firebird Award, went to Macondo, a very assured job of storytelling from Sudabeh Mortezai. The plot concerns Chechen refugees in Vienna struggling to get asylum status. At the film’s center is the remarkable performance of Ramasan Minkailov as a shrewd boy who has lost his father in the Chechin war. It’s a coming-of-age film, I suppose, but it also touches on issues of responsibility and loyalty without moralizing.

Serving on the jury was a treat for me, and I learned a lot from talking with my fellow jurors. Karena is famous for her roles in July Rhapsody and Inner Senses. More recently she has published Voyages, a remarkable book of Polaroid photographs. Christopher, as both actor and producer, has several new projects, including Electric Slide, coming to Tribeca. Joon-ho’s Snowpiercer will be released on 27 June in the US; after prolonged wrangling with Harvey Weinstein, this will be the director’s cut. The release will be limited, but it will pass to VOD thereafter.

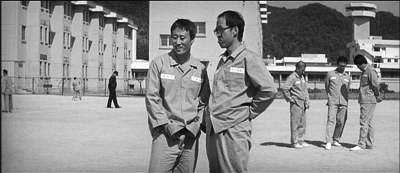

Black and white is the new black

While finishing Snowpiercer, Bong took on a pretty intriguing side project. He told his cinematographer, Hong Kyung-pyo, that he’d always wanted to make a black-and-white film but that no producers would finance one nowadays. Hong suggested that they remake Mother (2009) in black-and-white. So during postproduction on the big film, they used spare days to redo the color data from the older one. It wasn’t simply a matter of hitting a button. They performed color correction shot by shot so as to control the exact degree of tonality and contrast.

The result, already released on Blu-ray in South Korea and world-premiered at Mar del Plata, had its Asian premiere here in Hong Kong. It is exactly the same film, but without full color. Punning aside, it really does become more of a film noir–harsher, bleaker, and more somber.

The original film has a fairly muted palette, with lots of grays, beiges, soft blues, and earthy browns. In black and white you lose the nicely distinguished grayish-blues of a shot like this. (My monochrome frames are rough approximations derived from Photoshopping the color DVD; I don’t yet have the Blu-ray.)

At the same time, the performances seem more highlighted in the new version. Bong noted that certain colors, such as the green on the golf course, were a little opulent in the original. In the new version they don’t overwhelm the characters, and the abstract elements of the composition become a bit more apparent.

Bong also observed that some viewers have said that the characters’ eyes—pure black—are more prominent in black and white. I had never thought about it, but in old films the actors’ gazes do seem more gripping. At times, the mother’s face becomes more haunted, and haunting.

Just as striking, a clue (I’d hate to call it a red herring) depends on a crimson smear on a golf club. Rendered in black-and-white it becomes even more ambivalent.

Bong said in the Q & A that the project satisfied an urge he discovered while watching Nosferatu at an archive screening without any music. “It was a very purified experience.” He wondered if he could go back to “a very pure state of film, like a salmon swimming upstream.” Yet the new version still harbors one visual surprise.

The monochroming of Mother seems to me a rewarding experiment; I look forward to comparing the two versions and seeing how each can suggest different sides of a scene or summon up different expressive qualities. At the moment, I prefer the black-and-white version, and Bong suggested that he was starting to do the same. After Nebraska and Mother, maybe filmmakers will rediscover what black-and-white can do—and producers and audiences will let them.

Forma (2013).

If it’s Tuesday, this must be Belgium, if it’s July

The entrance to the Brussels Cinematek screening rooms. No cellphones, no drinks, and above all no frites.

DB here:

As every year, I’m spending time in Brussels doing research at the Royal Film Archive, and as usual every two years, I’m preparing to go to the Flemish Film Foundation’s Summer Film College, this time in Antwerp. My stay was timed, also as usual, to the Cinédécouvertes festival sponsored by the Cinematek.

Cinédécouvertes is a partly a festival of festivals, gathering most of its titles from Venice, Rotterdam, Berlin, and Cannes. It’s a good way for me to catch up with several top-flight films unlikely to come to the US, or at least any time soon. (See the links at the bottom of this entry for my earlier observations.) In screening only films that have not been bought for Belgian distribution, Cinédécouvertes’ record shows a keen talent-spotter’s eye. Just in the last ten years, its winners have included Japón, Oasis, Shara, Tropical Malady, Day Night Day Night, How I Ended This Summer, and Police, Adjective. The year 2000 was remarkable, with prizes given to four films: Miike’s Audition, Im’s Chunhyang, Kurosawa’s Barren Illusion, and Tarr’s Werckmeister Harmonies. My affection for this modest but robust festival goes back to the 1980s; it introduced me to films by Hou, Kitano, and Kiarostami when they were genuine cine-discoveries.

This year Bruno Dumont’s Hors Satan took the L’Age d’or prize, the one reserved for films that seek to disturb us in the vein of Buñuel’s classic. That prize consists of 5000 euros given to the filmmaker. The two other awards aim to support local distribution of the best work. The Austrian entry Atmen (Breathing) by Karl Markovics and Alejandro Landes’ Porfirio, set in Colombia, won the prizes. If either is picked up for Belgian release, the distributor will receive 10,000 euros to help cover costs. Shouldn’t other festivals imitate this strategy for getting films onto screens?

My lecture preparations for Antwerp kept me away from many festival offerings, but I did see two of the prizewinners. Atmen and Hors Satan reminded me that a lot of European art films, despite their reputation for being slow, have a crisp, laconic style. Abrupt cuts open and end scenes, while an unexpected close-up can accentuate a moment. This sort of precision meshes with other conventions of this tradition: delayed exposition, long scenes without dialogue or music, routines that structure the plot, and a demand that we let things unfold at a rhythm different from that of the goal-driven Hollywood cinema. Early on, the scruffy idler of Hors Satan shoots down a man while the vaguely punkish girl with him doesn’t bat an eye. What registers is the bare, brute act, no more and no less.

Eventually we’ll learn some causes and reasons, but in this mode of cinema, a gesture is given heft by coming out of nowhere, without benefit of much preparation. What we can count on is the repetition of a routine, such as the man’s praying or his receiving a piece of bread each day from an (initially) unseen donor. Sooner or later, something will emerge–a pattern of activity, if not a straightforward plot.

Similarly, we know almost nothing about the young man who gets dressed at the start of Atmen. Only gradually will his routines reveal his work-release from a juvenile prison and his growing awareness of his responsibility for the crime that put him there. In this unvarnished tale, which sends young Vogler to work assisting a mortician, we get nothing like the mixture of humor and poignancy we find in Takita’s Departures. Everything here is cool, even curt, with each shot providing a bit of action that we have to fit into the personality lurking behind Vogler’s guardedly blank expression.

That personality becomes clear, in a rather conventional way, when Vogler sets out to find the mother who abandoned him. Things are much more opaque in Hors Satan, in which miracles and near-miracles are performed with a grimy physicality suited to provincial life lived among marshes and rocky hillsides. If Atmen pulls into focus as a fairly clear-cut psychological drama, Dumont’s film tries for something grander and less committed to personality. It seems to me to aim for a sense of flinty, rough-hewn holiness that is beyond conventional piety. In The Tree of Life, faith bathes the lovely faithful in a glow–hell, it can make them levitate–but here faith, if that’s what’s involved, is irredeemably coarse, even ugly. (Hors Satan reminded Cinédécouvertes judge Charles Tatum of Abel Ferrara.) Like Atmen, though, Hors Satan gets to its destination through a storytelling technique that we can trace back to neorealism and its respect for dawdling exposition and the undramatic singular detail. Some cinematic traditions are endlessly fertile.

Earnest Goes to Summer Movie Camp

The Last of the Mohicans (1920).

This year’s July film college is woven of three strands. One is called “Masterpieces in Context,” and it includes films by De Sica, Ford, Flaherty, and others. The primary strand is devoted to film and the visual arts, and given my interests it looks exciting. Steven Jacobs will present lectures related to his new book, Framing Pictures, to be published during our event. Steven will survey a range of relationships between cinema and painting, including films about artists (e.g., Caravaggio) and scenes set in museums. Wouter Hessels, the incoming Director of the Cinematek, will discuss work by André Delvaux and other Belgian filmmakers. Lisa Colpaert will talk on “Noir Portraits.” And Tom Paulus will survey instances of the influence of painting and photography on directors’ visual style, ranging from Tourneur to Tarkovsky. Films include The Last of the Mohicans (1920), Spirit of the Beehive (1973), and Arsenal (1929). I’ll throw in my $.02 with a lecture called “Seeking and Seeing: Lessons from E. H. Gombrich,” which hopes to show how Gombrich’s approach to art history can help us study film history.

My main contribution, though, is to a third strand called “Dark Passages: Storytelling in 1940s Hollywood.” Through screenings of Suspicion (1941), Daisy Kenyon (1947), Laura (1944), A Letter to Three Wives (1948), and six other movies, I’ll survey some narrative innovations of this remarkable era. Our main attractions are A pictures, but I’ve pulled some clips and stills from B’s, which are no less intriguing in their flashbacks, dreams, hallucinations, splits in point-of-view, and treatments of mystery and suspense.

I’m still working on the talks, but what’s emerging is one unorthodox premise. As an experiment in counterfactual history, let’s pretend that World War II hadn’t happened. Would the storytelling choices (as opposed to the subjects, themes, and iconography) be that much different?In other words, if Pearl Harbor hadn’t been attacked, would we not have Double Indemnity (1944) or The Strange Affair of Uncle Harry (1945)? Only after playing with this outrageous possibility do I find that, as often happens, Sarris got there first: “The most interesting films of the forties were completely unrelated to the War and the Peace that followed.” Sheer overstatement, but back-pedal a little, and I think you find something intriguing.

Some lectures are in English, some in Dutch. All screenings are 35mm, with live accompaniment for the silent films. There will also be an excursion to Antwerp’s gorgeous, widely praised new museum, the MAS. It’s open until 11 on weeknights and until midnight on weekends, an admirable idea. I’ll be sure to take photos of the skull-mosaic terrace.

More on the summer film school after I’ve done it. In the meantime, coming up blog-wise: ideas about how people might have watched movies a hundred or so years ago.

I first explained my research in the film archive here. For previous years’ notes on the Cinematek’s annual festival, you can go to the category here. On the Cinephile Summer Camp, here is the report on the 2007 gathering and here’s the one on 2009. Sarris’ scandalous claim (yes, I too thought about The Best Years of Our Lives, They Were Expendable, Ministry of Fear, etc. etc.) is in the introductory essay, “Toward a Theory of Film History,” in his classic book The American Cinema (New York: Dutton, 1968), 25.

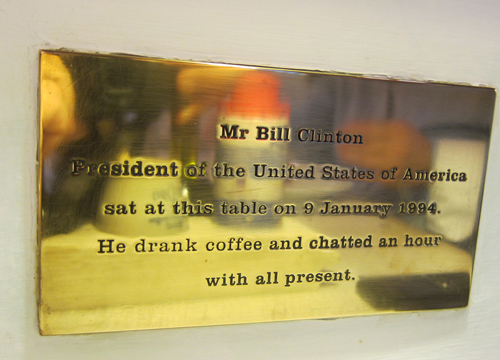

I especially believe the “with all present” part. This is apparently the table to get at Au Vieux St. Martin, Brussels. In reflection is Nicola Mazzanti of the Royal Film Archive.