Archive for the 'National cinemas: Central America' Category

Wrapping up the ROW

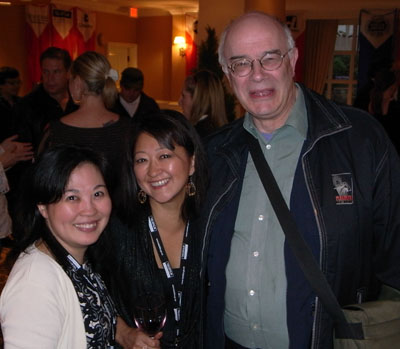

Paparazzi swarm over the nominees for the Dragons and Tigers Award at the Vancouver International Film Festival.

Kristin here:

Some final films from VIFF

So far Central American countries have produced fewer films than their neighbors to the north and south. So I couldn’t pass up The Wind and the Water, the first fiction feature made in Panama. Made by a collective of fifteen young indigenous people from the Kuna Yala archipelego under the leadership of MIT graduate and first-time director Vero Bollow, it’s a tale of threats to the paradisiacal island by developers who want to build a giant hotel there. It also reflects temptations for young people to desert their traditional lives on the islands for the attractions of nearby Panama City.

The contrast between the islands emerges through a simple tale. Machi, a young man from the islands, goes to the city for schooling and finds it grim and threatening. Rosy, a transplanted native who grew up there, aspires to be a model.

She returns to the islands for her grandfather’s funeral. Confronted with crude latrines and fish-head stews, she is initially miserable but gradually falls under the spell of the area’s beauty. Meanwhile her father works for the group planning to move the islands’ population to a new suburb and build their resort.

The plot is based loosely on that population’s vigorous efforts—successful so far—to fend off efforts of outsiders to gain control of the islands. I was reminded while watching it of the many classic documentaries of the 1930s and 1940s, like Song of Ceylon, shot by Americans and Europeans in exotic locales. For decades film scholars deplored the fact that the people who formed the subjects of such films were being portrayed by outsiders. The Wind and the Water, though a fiction film, has a strongly documentary thread running through it, but this time it is the local population making a film about their own situation.

Bollow (right), who initially left MIT to live in Panama and bring digital technology to indigenous people, wrote the script along with the fifteen team members. She attended Vancouver and answered questions, but members of the team will be traveling with the film to other festivals.

Bollow (right), who initially left MIT to live in Panama and bring digital technology to indigenous people, wrote the script along with the fifteen team members. She attended Vancouver and answered questions, but members of the team will be traveling with the film to other festivals.

In some ways, Ozcan Alper’s debut feature, Autumn, is a classic art-house film. Yusuf, a student radical, is released after ten years in prison because he has a fatal lung disease. He returns to his home. He returns to his rural home in the eastern Turkish mountains and settles in with his widowed mother, keeping his illness secret. He tutors a local boy in math and perhaps falls in love with a melancholy prostitute struggling to support her child.

Many of the scenes consist of the hero lying or sitting in the yard, contemplating the surrounding mountains as autumn slowly changes them. David found the lack of dramatic action and the slow pace of the scenes to be overly familiar conventions of art cinema. No doubt the hero’s goals are de-dramatized, as when he promises a bicycle to the student should he succeed in mother or when very late in the film he decides to help the prostitute. There is one central motif that becomes overly emphatic. When Yusuf first notices the prostitute, she is buying a Russian novel; they simultaneously sit alone watching the same broadcast of Uncle Vanya; eventually she tells Yusuf that he’s like a character out of Russian literature. The film’s tone successfully suggests this comparison without our needing to have it made explicit.

To me, the success of the film arises from the director’s integration of the landscape into the story. The prominence of the rugged landscape and the care with which the story is linked to the fall of leaves and the creeping of snow down the mountainsides lifts this above standard art-house fare. In this case, the fading of the year, beautifully brought into a central role by the cinematography, becomes linked more subtly to the hero’s plight.

Kill Daddy Goodnight, an Austrian film by veteran director Michael Glawogger, starts with a promising premise. The protagonist Ratz hates his father, a cold and critical government minister, and creates a videogame, “Kill Daddy Goodnight,” to wreak a fantasy revenge. Summoned by Mimi, a friend with whom he may or may not be in love, he abruptly flies to New York. She wants him to renovate the basement hideaway of her grandfather, a fugitive Nazi war criminal. Initially revolted, over the course of his work he comes to like the old man. Ratz also manages to find a sleazy internet entrepreneur willing to offer “Kill Daddy Goodnight” on his website, where it becomes an immediate success. Interspersed with this plot are scenes of an unidentified man (below) recording testimony against and visiting his childhood friend, who had worked for the Nazis during the war and killed his father.

So far, so good. But the film’s already complex plot is overburdened by strong hints of Ratz’s incestuous desire for his sister, a thread that comes to little. Mimi’s motivations are confusing, and it’s hard to sympathize with any of the characters. Perhaps that was the intention, but my sense was that the two intriguing plotlines, which could have fit neatly together, were diffused by distractions and uncertainties.

I didn’t get to many documentaries, but being a lover of Vivaldi’s vocal music, I had to see Argippo Resurrected. It’s the fascinating tale of how Czech conductor and musicologist Ondrej Macek ingeniously tracked down the lost 1730 opera, which had originally been composed for Prague. He then staged the piece in one of the two perfectly preserved court theaters of the era, the Castle Theatre at Cesky Krumlov, two hours outside of Prague, near the Austrian border.

The other is at Drottningholm, outside Stockholm, where in 1999 David and I had the privilege of seeing The Garden, a new opera about Linnaeus. (It was the first premiere at the theater since it was sealed in the 18th century.) The original candles have prudently been replaced by electric replicas of one candlepower each, flickering realistically. The Cesky Krumlov theater still uses real candles to light both the stage and the musicians’ stands. I guess this says something about fire codes in Eastern Europe. I for one would be happy to risk it in order to have a thoroughly authentic experience, especially if a Vivaldi opera was playing.

It’s a complicated story to fit into 62 minutes. Director Dan Krames took a clever and effective approach, starting backwards. He shows the theater first, with its wooden framework, sets, and stage machinery. He then goes on to introduce some of the musicians and singers, in the process explaining the concept of authentic performance style to those who may not be familiar with it. We also get to see some short excerpts from rehearsals, so that we come to know the opera a little. Only then does Krames proceed to the tale of Macek’s search for the original manuscript and his laborious piecing-together of the individual arias. Macek makes an engaging subject, though he is so self-deprecating about his discovery that the film has to include another musicologist to explain just how extraordinary the accomplishment was.

Finally Macek takes us on a tour of Venice, showing the few surviving places associated with Vivaldi, whose life is little documented. Along the way, there are further excerpts from rehearsal for the production shown, featuring a collection of excellent singers. Krames told me that Argippo Resurrected should be released on DVD in about a year. In the meantime, a live recording of Macek’s production is available as a 2-CD set.

Some final photos

Film festivals aren’t just for watching movies, of course. They’re for seeing old friends, meeting new ones, and sharing meals—including the festival’s wonderful hand-made waffles—to talk about what we’ve seen. As usual, David had his camera in hand nearly all the time, as the accompanying images show.

Theresa Ho, Eunhee Cha, and Tony Rayns: Three key players in the Vancouver Festival.

Chris Chong (director of Karaoke) and Liu Jiayin (Oxhide II).

Bob Davis, of American Cinematographer, and Noel Vera, Critic after Dark.

Canadian corner: Lisa Roosen-Runge, Shelly Kraicer, and Peter Rist.

Get your Terimayo, Oroshi, and Okonomi here: Japadog, a Vancouver Institution.