Archive for the 'National cinemas: China' Category

Vancouver 2018: Crime waves

Burning (2018).

DB:

It’s striking how many stories depend on crimes. Genre movies do, of course, but so do art films (The Conformist, Blow-Up) and many of those in between (Run Lola Run, Memento, Nocturnal Animals). The crime might be in the future (as in heist films ), the ongoing present (many thrillers), or the distant past (dramas revealing buried family secrets).

Crime yields narrative dividends. It permits storytellers to probe unusual psychological states and complex moral choices (as in novels like Crime and Punishment, The Stranger). You can build curiosity about past transgressions, suspense about whether a crime will be revealed, and surprise when bad deeds surface. Crime has an affinity with another appeal: mystery. Not all mysteries involve crimes (e.g., perhaps The Turn of the Screw), and not all crime stories depend on mystery (e.g., many gangster movies). Still, crime laced with mystery creates a powerful brew, as Dickens, Wilkie Collins, John le Carré, and detective writers have shown.

We ought, then, to expect that a film festival will offer a panorama of criminal activity. Venice did last year and this, and so did the latest edition of the Vancouver International Film Festival. Some movies were straightforward thrillers, some introduced crime obliquely. In one the question of whether a crime was committed at all led–yes–to a full-fledged murder.

Smells like teen spirit

Diary of My Mind.

Start with the package of four Swiss TV episodes from the series Shock Wave. Produced by Lionel Baier, these dramas were based on real cases–some fairly distant, others more recent, all involving teenagers. The episodes offer an anthology of options on how to trace the progress of a crime.

In Sirius a rural cult prepares for a mass suicide in expectation they’ll be resurrected on an extraterrestrial realm. The film focuses largely on Hugo, a teenager turned over to the cult by his parents. Director Frédéric Mermoud gives the group’s suicide preparations a solemnity that contrasts sharply with the food-fight that they indulge in the night before. Similarly, The Valley presents a tense account of a young car thief pursued by the police. Locking us to his consciousness and a linear time scheme, director Jean-Stéphane Bron summons up a good deal of suspense around the boy’s prospects of survival in increasingly unfriendly mountain terrain.

Sirius and The Valley give us straightforward chronology, but First Name Mathieu, Baier’s directorial contribution, offers something else. A serial killer is raping and murdering young men, but one of his victims, Mathieu, manages to escape. The film’s narration is split. Mathieu struggles to readjust to life at home and at school, while the police try to coax a firm identification from him. This action is punctuated by flashback glimpses of the traumatic crime. The result explores the parents’ uncertainty about how restore the routines of normal life, the police inspector’s unwillingness to press Mathieu too hard, and the boy’s self-consciousness and guilt as the target of the town’s morbid curiosity.

This insistence on the aftereffects of a crime dominates Diary of My Mind, Ursula Meier’s contribution to the series. This too uses flashbacks, mostly to the moments right after a high-school boy kills his mother and father. But there’s no whodunit factor; we know that Ben is guilty. The question is why. Ben’s diary seems to offer a decisive clue (“I must kill them”), but just as important, the magistrate thinks, is his creative writing under the tutelage of Madame Fontanel, played by the axiomatic Fanny Ardent. Because she encouraged her students to expose their authentic feelings, Ben’s hatred of his father had surfaced in his classroom work. Perfectly normal for a young man, she assures the magistrate. No, he asserts: a warning you ignored. The shock waves that engulf onlookers after a crime, the suggestion that art can be both therapeutic and dangerous, the question of a teacher’s duty to both her pupils and the society outside the classroom–Diary of My Mind raises these and other themes in a compact, engaging tale.

Last hurrah of (movie) chivalry

Chinese director Jia Zhangke is no stranger to criminal matters. His films have dwelt on street hustles, botched bank robberies, and hoodlums at many ranks. Ash Is Purest White is a gangster saga, tracing how a tough woman, Qiao, survives across the years 2001-2018. Initially the mistress of boss Bin, Qiao rescues him from a violent beatdown using his pistol. She takes the blame for owning a firearm. Getting out of prison, Qiao tracks down the now-weakened Bin, who has taken up with another woman.

Ash Is Purest White tackles a familiar schema, the fall of a gang leader, from the unusual perspective of the woman beside him, who turns out to be stronger than he is. Most of the film is filtered through her experience, and along with her we learn of Bin’s decline and betrayal, along with his integration into the corrupt and bureaucratic capitalism of twenty-first century China. The second half of the film shows Qiao forced to survive outside the gang’s milieu. A funny scene plays out one of her scams: picking a prosperous man at random, she announces that her sister, implicitly his mistress, is pregnant. Just as important, Qiao’s adventures allow Jia to survey current mainland fads and follies, including belief in UFO visits.

Among those follies, Bin suggests, is a trust in mass-media images. As Ozu’s crime films (Walk Cheerfully, Dragnet Girl) suggested that 1930s Japanese street punks imitated Warner Bros. gangsters, so Jia’s mainland hoods model themselves on the romantic heroes of Hong Kong cinema. They raptly watch videos of Tragic Hero (1987) and cavort to the sound of Sally Yeh’s mournful theme from The Killer (1989). They derive their sense of the jianghu--that landscape of mountains and rivers that was the backdrop of ancient chivalry–not from lore or even martial-arts novels but from the violent underworld shown on TV screens.

Bin’s decline is portrayed as abandoning those ideals of righteousness and self-sacrifice flamboyantly dramatized in the movies. But Qiao clings to the imaginary jianghu to the end. She explains to him that everything she did was for their old code, but as for him: “You’re no longer in the jianghu. You wouldn’t understand.” You can respect his pragmatism and admire her tenacity, but he’s still a feeble figure, and she’s left running a seedy mahjongg joint–one much less glamorous than the club she swanned through at the film’s start. Appropriately for someone who got her idea of heroism from videos, we last see her as a speckled figure on a CCTV monitor.

From dailiness to darkness

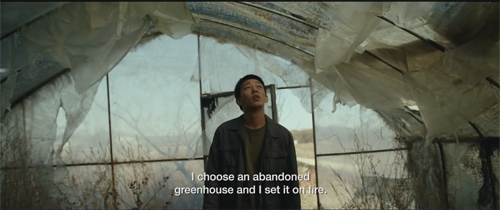

Burning.

Often the crime in question is presented explicitly, but two films leave it to us to imagine what shadowy doings could have led to what we see. In Manta Ray, by Phuttiphong “Pom” Aroonpheng, we get the familiar motif of swapped identity. A Thai fisherman finds a wounded man in the forest and nurses him back to health. The victim is a mute Rohinga whom the fisherman names Thongchai. They share a home and the occasional dance and swim, even a DIY disco.

But who attacked Thongchai in the forest, and why? And what is the connection to the unearthly gunman who paces through the forest, bedecked in pulsating Christmas bulbs? And what makes the foliage teem with gems glowing in the murk? Somewhere, there has been a crime.

Manta Ray accumulates its impact gradually, with the scenes of the men’s routines giving way to mystery when the fisherman vanishes and Thongchai (named by the fisherman for a Thai pop singer) is trailed by a ninja-like figure clad in a red cagoule. A disappearance and a reappearance (of the fisherman’s wife) punctuate moody scenes of trees and sea. The opacity of the action makes a political point: offscreen, Thais brutally hunt down the refugee Rohingas. But the critique of anti-immigrant brutality is intensified by the lustrous cinematography (Aroonpheng was a top DP). You can feel the texture of the planks in the cabin and the sharp edges of the gems that fingers root out of the forest floor. This is probably the most tactile movie I saw at VIFF.

Then there was Lee Chang-dong’s Burning. Lee started his career strong and has stayed that way. The slowly paced, Kitanoesque gangster story Green Fish (1997) and Peppermint Candy (1999), with its reverse-order chronology, both achieved local popularity and established him as a fixture on the festival circuit. Oasis (2002), a daring romance of a disabled couple, won a special prize at Venice. Secret Sunshine (2007) brought Lee even more widespread fame. Like the episodes of Shock Waves, it dealt with the aftereffects of a horrific crime. Virtually everyone I know who saw the film remembers most vividly a particular scene: the heroine, having converted to Christianity and at last ready to forgive the perpetrator, visits him in prison. It’s one of the most nakedly blasphemous scenes I’ve ever seen, carried off with a shocking calm. Crime–this time, a gang rape–is also at the center of Poetry (2010), with another mother facing familial tragedy.

Most of these plots, particularly Poetry, are rather busy, but Burning is more stripped down (though not short). Lee Dong-su maintains the shabby family farm while his father is in jail awaiting trial. In town Dong-su meets Haemi, a former classmate now running sidewalk giveaways.

She lures him into her life by asking him to feed her cat while she’s in Africa, but before she leaves they start an affair. But he seldom breaks into a smile, favoring a puckered-lip passivity. After their coupling, we get his POV on a blank wall.

This turns out to be the first of many disquieting passages. Between bouts of tending livestock, feeding Haemi’s cat, and masturbating to her picture, Dong-su gets mysterious phone calls with no one on the line. He meets Haemi at the airport only to discover that she’s formed a friendship (or more?) with the suave Ben, whose gentle courtesy makes Dong-su feel an even bigger bumpkin. Soon the three are hanging out together, but at parties Dong-su can only stare at Ben’s yuppie friends. Dong-su, who wants to be a writer, is a fan of Faulkner, but Ben compares himself to the Great Gatsby.

After a long night of relaxing at the farm, with the men watching Haemi dance topless, she disappears. A black frame, a dream of a burning greenhouse, and Dong-su is left alone halfway through the movie. What happened to Haemi? And why does Ben say he enjoys torching greenhouses? Dong-su turns detective,

Lee is a master of pacing, and the deliberateness of the film delicately turns a romantic drama into a critique of entitled lifestyles and then into a psychological thriller. We are locked to Dong-su’s consciousness except for a couple of telltale shots of Ben calmly studying his rival from afar. We get Vertigo-like sequences of Dong-su trailing Ben and probing for clues and perhaps having more dreams. At the same time, Dong-su starts writing, as if Haemi’s disappearance has inspired him, but he finds more violent ways to release his simmering bewilderment.

After only one viewing, I didn’t find Burning as devastating a film as Secret Sunshine or Poetry, but I’d gladly watch it again and probably I’d see more in it. Lee manages to sustain over two and a half hours a plot centering on three, then two principal characters. He has earned the right to soberly take us into the mundane rhythm of a loner’s life and then shatter that through an encounter with two enigmatic figures who may be playing mind games. As with Manta Ray, we have to infer some of the action behind the scenes, but that just shows that in cinema, classic or modern, crime can pay.

Thanks as ever to the tireless staff of the Vancouver International Film Festival, above all Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, Shelly Kraicer, Maggie Lee, and Jenny Lee Craig for their help in our visit.

Snapshots of festival activities are on our Instagram page.

Japadog, a Vancouver landmark.

Vancouver 2018: Landscapes, real and imagined

Shoplifters (Kore-eda, 2018).

DB here:

We’ve been attending the Vancouver International Film Festival since 2004. (The entries are tagged here.) It’s provided us many of our happiest viewing experiences, and this year is proving just as exciting. In particular, the festival’s long commitment to new films from Asia hasn’t flagged. Thanks to programmers Shelly Kraicer and Maggie Lee there has been plenty to showcase trends in Hong Kong, China, Taiwan, South Korea, and other lands. We won’t, unfortunately, be here for Hong Sangsoo’s Grass, but here are interim reflections on four items that we’ve seen in our first days.

Families, fraught and fragile

Shoplifters.

Girls Always Happy is a quiet but ingratiating first feature from Yang Ming Ming. Mother and daughter are both writers, and they struggle to live together in harmony while hoping for a legacy from Grandfather and for some resolution in their love lives. Yang says that she based the film on her own life, which rings true when you consider the range of emotions that well up. The two women tease each other, insult each other, ravenously devour meals together, shop partly to annoy sales staff, and sometimes burst out in screams. Reconciliations may be temporary but are still heartfelt.

With the two of them jammed together in a hutong, a neighborhood of cramped old ground-floor apartments, their jousts take on an intensity captured by Yang’s exceptionally tight framings and rapid cutting. Yang storyboarded the entire film, which allowed her quite precise control of composition and focus.

The relentless close-ups allow both psychological intimacy and subtle performances, as well as comparison of eating styles. Trips outside—Wu on her scooter or in her lover’s modern apartment, the mother at a hair salon—provide a respite from what’s essentially a series of escalating two-handed combats. The final shot is a lengthy take that carries our heroines forward into their city. Yang explained in the Q & A that after a film full of fast cutting and lots of talk she decided to end with the sort of long take Chinese filmmakers favor. In this context, with a canny use of a bus’s rearview mirror, the shot becomes an exhilarating, floating passage into the Beijing night.

Girls Always Happy came to VIFF garlanded with awards, including prizes from both the Berlinale and the Hong Kong Film Festival. Even more honored was the latest by Kore-eda Hirozaku, The Shoplifters, which won the Palme d’Or at Cannes. It’s another of his family dramas (we’ve discussed Still Walking, I Wish, Like Father, Like Son, Our Little Sister, and After the Storm), but here the notion of family is given an uncanny twist at the end.

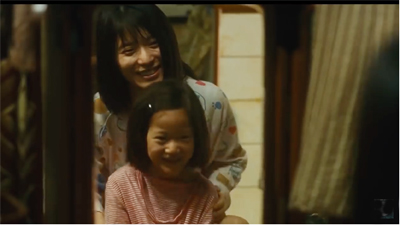

Each member, as per Kore-eda’s habit, is given a specific, respectful delineation. There’s the happy-go-lucky Osamu, a day laborer who both coddles the boy Shota and leads him into petty crime. There’s the maternal Nobuyo who works at a dry-cleaning facility and pilfers what she finds in pockets. Twentysomething Aki works at a sex club flashing her breasts and bottom at men crouched behind one-way mirrors. Grandma keeps the group going with her pension, her pachinko-playing, and some secret sources of income. Into this household comes Yuri, an abused child brought home like an abandoned cat.

Like Tsai Ming-liang’s more somber Rain Dogs, this is a film about people on the margins. The kids don’t go to school; Shota teaches Yuri the tricks of shoplifting, while Aki warms to a sex-club client. As in Girls Always Happy, interiors are sharply distinguished from exteriors, but not by close framings and shifting focus. Instead, master shots fill the frame with the detritus of seven people jammed in together. (See shot above.)

In a film so concentrated on characterization, we naturally get the sort of privileged moments that Kore-eda excels in. Osamu pauses in his construction work to stand looking around an unfinished apartment—a modest one, but a home he can never have. The young kids collect cicadas. Aki cradles a lonely punter in her lap. Nobuyo consoles Yuri by comparing the girl’s scars to burns Nobuyo has accumulated from ironing clothes. Grandma, watching her charges play on the beach, pours sand to cover the age spots on her legs. The ensemble comes together in moments of shared joy at the seaside or watching the fireworks at the Sumida River festival.

But these moments don’t prepare us for the unsettling revelations about the characters’ pasts that we get in the last half hour. Even here, though, the details of behavior remain indelible. One astonishing shot turns a cinematic staple—a woman trying to wipe away tears—into a tour de force of facial performance by Ando Sakura.

The Shoplifters reminded me of Ozu’s Passing Fancy and Inn in Tokyo, obliquely but sharply condemning the economic conditions that push people into wayward lives. It’s a gently subversive film about people flung together resourcefully trying to survive and find happiness by flouting the comfortable norms of middle-class morality.

Time out of mind

A Land Imagined.

Lush Reeds, by Yang Yishu, has plenty of the long takes that Girls Always Happy avoids. In nearly abstract framings, newspaper reporter Xiayin moves through minimalist offices and country lanes, bleak apartments and dense foliage.

As in many postwar films, drama sometimes becomes subordinate to the walks taken by the protagonist into an overwhelming, mysterious environment.

Against the wishes of her politically cautious editor Xiayin inquires into complaints of rural pollution. At the same time, she’s pregnant and is growing distant from her fairly cold husband. Her visit to the countryside becomes a threatening experience that brings to light parallels between the death of a villager and the apparent suicide of a fellow reporter.

The film is less linear than I suggest. Yang breaks up the story into midsize chunks and sets them out of order, so that some images–a little girl who meets Xiayin in the village, a shoe on a riverbank, the rescue of a suitcase from a rubbish depot–could fit into one time frame or another. Yang is even so bold as to run the title credit again midway through the film, suggesting that what follows might be backstory, or imagination, or an alternative film, or something in between.

A similar ambiguity pervades A Land Imagined (2018), another prize-winner (Golden Leopard, Locarno). It centers on a migrant worker Wang working at a Singapore site devoted to extending the coastline with sand dredged up or brought from other countries. Wang has disappeared, and the investigating cop Lok soon learns that Wang’s Bengali friend Ajit has vanished as well. A flashback takes us into the backstory, showing Wang spendiing his nights at a cybercafé and getting harassed by a troll who invades his videogame screen. Wang also begins a chaste affair with the tough gamine Mindy who oversees the game parlor. Eventually the flashback turns into a parallel, dreamlike narrative, with Ajit by turns dead and alive and Lok reenacting scenes involving Wang.

Director Yeo Siew Hua has given this noirish tale an appropriately lustrous treatment, with saturated long shots of black derricks looming against a red sky or sunk in sickly orange murk. Lyrical slow-motion musical interludes enhance the dreamlike ambience, and there’s a post-Wong-Kar-wai freedom of camera placement in the candy-colored cybercafé.

In his comments after the screening, Yeo spoke of trying to provide a counter-image to “the postcard, Crazy Rich Asians” depiction of Singapore. The shifting time frames and uncertain stretches of subjectivity are connected, for Yeo, with a sleeplessness suffered not only by the main characters but also by the population at large. The “land imagined” isn’t only the sand that expands the contours of the shoreline but also the hallucination of a hypermodern city state built on the labor of workers who can conveniently go missing.

Thanks as ever to the tireless staff of the Vancouver International Film Festival, above all Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, Shelly Kraicer, Maggie Lee, and Jenny Lee Craig for their help in our visit.

Snapshots of festival activities are on our Instagram page.

Girls Always Happy.

Friendly books, books by friends

Moses and Aaron (1974).

DB here:

When the stack of books by friends threatens to topple off my filing cabinet, I know it’s time to flag them for you. I can’t claim to have read every word in them, but (a) we know the authors are trustworthy and scintillating; (b) what I’ve read, I like; (c) the subjects hold immense interest. Then there’s (d): Many are suitable seasonal gifts for the cinephiles in your life (which can include you).

Happy birthday, SMPTE

Starting off in 1916 as the Transactions of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers, this peerless record of American moving-image technology has gone through many changes of name and format. It’s now The SMPTE Motion Imaging Journal. Its back issues have been a treasure house for scholars studying the history of movie technology, and it has outdone itself for its 100th Anniversary Issue, published in August.

Starting off in 1916 as the Transactions of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers, this peerless record of American moving-image technology has gone through many changes of name and format. It’s now The SMPTE Motion Imaging Journal. Its back issues have been a treasure house for scholars studying the history of movie technology, and it has outdone itself for its 100th Anniversary Issue, published in August.

It includes survey articles on the history of film formats, cameras and lenses, recording and storage, workflows, displays, archiving, multichannel sound, and television and video. There’s even an overview of closed-captioning. The issue costs $125 for non-SMPTE members, and it’s worth it. Many libraries subscribe to the journal as well.

A highlight is John Belton’s magisterial “The Last 100 Years of Motion Imaging,” which includes twenty-two pages of dense timelines of innovations in film, TV, and video. They stretch back beyond 1916, to 1904 and the transmission of images by telegraph. John’s article is provocative, suggesting that we might think of digital cinema as returning to film’s origins in handmade images for optical toys.

Lucas predicted that digital postproduction brought film closer to painting, and for more and more filmmakers that prediction is coming true. I was startled to learn that 80% of Gone Girl was digitally enhanced after shooting.

Yes, sir, that’s our BB

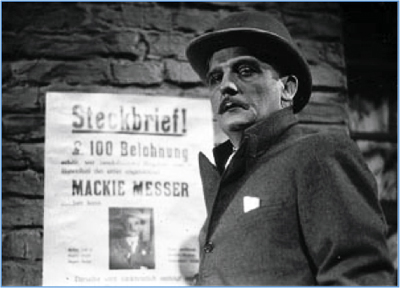

Die 3 Groschen-Oper (1931, G. W. Pabst).

During the 1970s, Bertolt Brecht’s name was everywhere in film studies. He epitomized what an alternative, oppositional, or subversive cinema ought to be. Cinema, even more powerfully than theatre, was a machine for producing illusions. So in his name critics objected to happy endings, plots that tidied up reality, characters with whom we ought to identify, messages that masked the real nature of bourgeois society. Films made all these things seem part of the natural order of things.

The Brechtian antidote was, as people used to say, to “remind people they were watching a film.” This was done by rejecting what he called the Aristotelian model and replacing it with the “alienation effect”: a panoply of distancing devices like intertitles, characters addressing the camera, actors confessing they were actors, and a display of the means of cinematic production (including shots of the camera shooting the scene).

The promise was that once viewers were banished from the imaginary world of the film they would exercise their intellects and coolly appraise not only the fiction machine but its ideological underpinnings. Godard was the chief cinematic surrogate for Brecht, and La Chinoise (1967) became the big prototype of Brechtian cinema—unless you preferred the more austere version incarnated in Straub/Huillet’s Chronicle of Anna Magdalena Bach (1967) and their adaptation of Othon (1969). The ideas spread fast, helped by the user-friendly Brechtianism of Tout va bien (1972).

The promise was that once viewers were banished from the imaginary world of the film they would exercise their intellects and coolly appraise not only the fiction machine but its ideological underpinnings. Godard was the chief cinematic surrogate for Brecht, and La Chinoise (1967) became the big prototype of Brechtian cinema—unless you preferred the more austere version incarnated in Straub/Huillet’s Chronicle of Anna Magdalena Bach (1967) and their adaptation of Othon (1969). The ideas spread fast, helped by the user-friendly Brechtianism of Tout va bien (1972).

Brecht became part of Theory. In French literary and theatrical culture of the 1950s, his ideas on staging and performance had claimed the attention of Roland Barthes and other Parisian intellectuals. Godard was alert to the trend early, it seems; he had fun in Contempt (Le mépris, 1963) citing the two BB’s (the other was Brigitte Bardot, bébé), and letting Lang quote a poem by his old collaborator and antagonist. By the time Anglo-American film theorists were ready for semiotics, Brecht was offering support. Didn’t his anti-illusionism chime well with the belief that all sign systems were arbitrary and culturally relative?

My summary is too simple, but then so were many borrowings. Soon enough any highly artificial cinematic presentation might be called “Brechtian,” though usually minus the politics. In the academic realm, Murray Smith’s book Engaging Characters (1995) pointed out crucial weaknesses in the anti-illusionist, anti-empathy account. By then, the certified techniques were becoming part of mainstream cinema. Thereafter, we had Tarantino’s section titles and plenty of movies breaking the fourth wall. Brecht might have enjoyed the irony of using the to-camera confessions of The Wolf of Wall Street (2013) bent to support cynical swindling. Isn’t The Big Short (2015) a sort of Hollywoodized lehrstück (“learning play”)?

Brecht’s writings should be read and studied by every humanist and certainly everybody interested in film. They’re clear, blunt, and often sarcastic.

This beloved “human interest” of theirs, this How (usually dignified by the word “eternal,” like some indelible dye) applied to the Othellos (my wife belongs to me!), the Hamlets (better sleep on it!), the Macbeths (I’m destined for higher things!), etc.

Now Marc Silberman, our colleague here at Madison, has completed a trio of books that make the master’s work available. Bertolt Brecht on Film and Radio includes essays, scripts, and the Threepenny Opera lawsuit brief. There’s also Brecht on Performance and a complete revision of that trusty black-and-yellow volume dear to many grad students: Brecht on Theatre. The latter two collections Marc worked on with collaborators. All are indispensible to a cinephile’s education. As Brecht imagined a bold political version of music he called misuc; can we imagine a cenima?

From BB to S/H

Speaking of Straub and Huillet, every decade or so somebody comes out with a book about them. This time we have to thank the admirable Ted Fendt, in the twenty-sixth volume in the series sponsored by the Austrian Film Museum (as well as the Goethe Institute and Synema). Like the Hou Hsiao-hsien volume (reviewed here), Jean-Marie Straub & Danièle Huillet is fat and full of ideas and information.

There are interviews, tributes from filmmakers (Gianvito, Farocki, Gorin), and Fendt’s account of distribution and reception of their films in the Anglophone world. This last includes charming facsimile correspondence, with one Huillet letter pockmarked by faulty typewritten o’s. As you’d expect, she is objecting to making a 16mm print of Moses and Aaron (1974) from the 35. (“No, definitively.”)

There are interviews, tributes from filmmakers (Gianvito, Farocki, Gorin), and Fendt’s account of distribution and reception of their films in the Anglophone world. This last includes charming facsimile correspondence, with one Huillet letter pockmarked by faulty typewritten o’s. As you’d expect, she is objecting to making a 16mm print of Moses and Aaron (1974) from the 35. (“No, definitively.”)

Starting things off is a lively and comprehensive survey of the duo’s careers by Claudia Pummer, with welcome emphasis on production circumstances and directorial strategies. The book wraps with a detailed thirty-page filmography and a substantial bibliography.

My thoughts about S/H are tied up with their earliest work, when I first learned of them. So I loved, and still love, Not Reconciled (1965) and The Chronicle of Anna Magdalena Bach. I also have a fondness for Moses and Aaron, Class Relations (1983), From Today until Tomorrow (1996), and Sicilia! (1998). I find others out of my reach, and several others I haven’t yet seen. People I respect find all their work stimulating, so I suspect it’s really a matter of gaps in my taste.

Whether you like them or not, they’re of tremendous historical importance. Without them, Jim Jarmusch and Béla Tarr, and of course Pedro Costa and Lav Diaz, would not have accomplished what they have. And especially in December 2016, we ought to find their unyielding ferocity inspiring. Remember them on Dreyer: “Any society that would not let him make his Jesus film is not worth a frog’s fart.” Brecht would have approved.

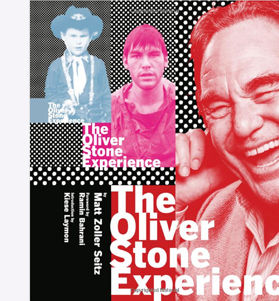

Stone’d

To the minimalism of Straub and Huillet we can counterpoint the maximalism of Oliver Stone, the most aggressive tabloid American director since Samuel Fuller (although Rococo-period Tony Scott gives him some competition). After two books on Wes Anderson, Matt Zoller Seitz has brought us a booklike slab as impossible as the man’s films. Can you pick it up? Just barely. Can you read it? Well, probably not on your lap; better have a table nearby. Does its design mirror the maniacal scattershot energy of films like JFK (1991), Natural Born Killers (1994), and U-Turn (1997)? Watch the title propel itself off the cover.

The Oliver Stone Experience is basically a long interview, sandwiched in among luxurious photos, script extracts, correspondence, and the sort of insider memorabilia that Matt has a genius for finding. We get not only pictures of Stone with family and friends, on the set, and relaxing; there are bubblegum cards from the 40s, collages of posters and filming notes, maps, footnotes, and shards of texts slicing in from every which way. Newspapers, ads, and production documents are scissored into the format, including a Bob Dole letter fundraising on the basis of the naughtiness of Natural Born Killers. Beautiful frame enlargements pay homage to the split-diopter framings of Born on the Fourth of July (1989) and the shadow of the 9/11 plane sliding up a facade in World Trade Center (2006). When Stone had second thoughts about things he’d said, Matt had the good idea of redacting the interview like a CIA file scoured with thick black lines.

The Oliver Stone Experience is basically a long interview, sandwiched in among luxurious photos, script extracts, correspondence, and the sort of insider memorabilia that Matt has a genius for finding. We get not only pictures of Stone with family and friends, on the set, and relaxing; there are bubblegum cards from the 40s, collages of posters and filming notes, maps, footnotes, and shards of texts slicing in from every which way. Newspapers, ads, and production documents are scissored into the format, including a Bob Dole letter fundraising on the basis of the naughtiness of Natural Born Killers. Beautiful frame enlargements pay homage to the split-diopter framings of Born on the Fourth of July (1989) and the shadow of the 9/11 plane sliding up a facade in World Trade Center (2006). When Stone had second thoughts about things he’d said, Matt had the good idea of redacting the interview like a CIA file scoured with thick black lines.

The whole thing comes at you in a headlong rush. Amid the pictorial churn and several essays by other deft hands, we plunge into and out of that stellar interview, mixing biography and filmmaking nuts-and-bolts. Matt gets deep into technical matters, such as Stone’s penchant for rough-hewn editing, as well as raising some big ideas about myth and autobiography. There are occasional quarrels between interviewer and interviewee. Out of the blue we get remarks like “Alexander was not only bisexual, he was trisexual,” which was not redacted.

The book’s very excess helps make the case for Stone’s idiosyncratic vision. Matt’s connecting essays, along with the vast visual archive he’s scavenged and mashed up, made me want to rethink my attitude toward this overweening, sometimes crass, sometimes inspired filmmaker. He now seems a quintessential 80s-90s figure, as much a part of the era as Reagan, Bush, and Clinton. Stone emerges as a resourceful defender of The Oliver Stone Experience, articulating a radical political critique with gonzo verve.

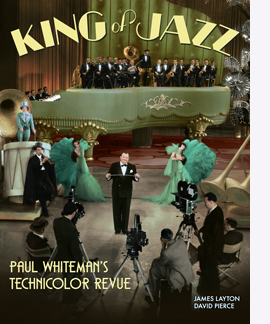

Rhapsody in white

If lifting the Book of Stone doesn’t suffice for exercise, try another weighty and sumptuous item, King of Jazz: Paul Whiteman’s Technicolor Revue, by James Layton and David Pierce. Last spring the Museum of Modern Art premiered one of the most ravishing restorations I’ve ever seen, a digital version of King of Jazz (1930).

If lifting the Book of Stone doesn’t suffice for exercise, try another weighty and sumptuous item, King of Jazz: Paul Whiteman’s Technicolor Revue, by James Layton and David Pierce. Last spring the Museum of Modern Art premiered one of the most ravishing restorations I’ve ever seen, a digital version of King of Jazz (1930).

This period piece is in its own way as wild as an Oliver Stone movie. From its opening cartoon of Paul himself as a Great White Hunter bagging a lion, it’s a virtually self-parodying account of how a black musical tradition got netted, trussed up, and caged for the swaying delectation of white audiences. (No need to mention the irony of the name of our King.)

Along the way we have some straight-up songs (including some by Bing Crosby) spread among extravagant dance numbers. The Universal crane gets a workout as well. The music is infectious, the performers sweating to please, and the restoration–coming, I hope, to your screen soon–finally shows what two-color Technicolor could do. This is the definitive version of a film too often known in cut versions with shabby visuals and sound.

The book is an in-depth contextualization of the film, the studio, and the tradition of musical revues, both on stage and in film. It records the production and reception, with rich documentation throughout. The story of assembling the restoration is there too, and it’s a saga in itself. David is one of the moving spirits behind the online Media History Digital Library and its gateway Lantern. James is Manager of the Celeste Bartos Film Preservation Center at the Museum of Modern Art. Their collaboration has given us both a lush picture book and a serious, always enjoyable piece of scholarship. Their book proves the value of crowdsourcing: funded by online subscription, it was self-published. In this and much else, it can be a model for film historians pursuing questions that commercial and university presses might find too specialized. The result is a model of ambitious research, writing, and publishing.

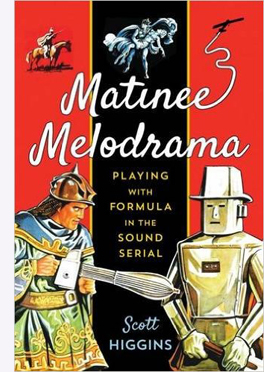

Visiting Radio Ranch

Gene Autry in The Phantom Empire (1935).

For about thirty years I’ve been arguing that one fruitful research program in film studies involves what I call a poetics of cinema: the study of how, under particular historical conditions, films are made to achieve certain effects. This program coaxes the researcher to analyze form and style, study changing norms of production and reception, and consider how filmmakers work in their institutions and creative communities, with special focus on craft routines, work methods, and tacit theories about the ways to make a movie.

A sturdy example of this approach has appeared from Scott Higgins. His Matinee Melodrama fulfills the promise of its subtitle: Playing with Formula in the Sound Serial. Scott has closely examined this widely despised genre, plunging into the 200 “chapterplays” produced in America between 1930 and 1956. They offer bald and bold display of the rudiments of action-based storytelling: “If Hitchcock built cathedrals of suspense from fine brickwork of intersecting subjectivities and formal manipulations, sound serials used Tinkertoys.”

A sturdy example of this approach has appeared from Scott Higgins. His Matinee Melodrama fulfills the promise of its subtitle: Playing with Formula in the Sound Serial. Scott has closely examined this widely despised genre, plunging into the 200 “chapterplays” produced in America between 1930 and 1956. They offer bald and bold display of the rudiments of action-based storytelling: “If Hitchcock built cathedrals of suspense from fine brickwork of intersecting subjectivities and formal manipulations, sound serials used Tinkertoys.”

Scott traces production practices and conventions, focusing in particular on two dimensions. First, to a surprising degree, serials rely on the conventions of classic stage melodrama, such as coincidence and more or less gratuitous spectacle. Second, the serials are playful, even knowing. Like video games, they invite viewers to imagine preposterous narrative possibilities, not only in the imagination but also on the playground, where kids could mimic what they saw Flash Gordon or Gene Autry do.

Matinee Melodrama investigates the implications of these dimensions for narrative architecture, visual style, and the film and television of our day. Scott closes with analysis of the James Bond series, the self-conscious mimicking of serial conventions in the Indiana Jones blockbusters, and the Bourne saga, and he shows how they amp up the older conventions. “Like the contemporary action film generally, the Bourne movies participate in a cinematic practice vigorously constituted by studio-era serials. That is, they blend melodrama with forceful articulations of physical procedure in scenes of pursuit, entrapment and confrontation.”

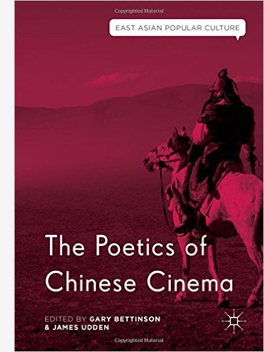

Poetics, frank or stealthy

The Red Detachment of Women (1971).

Scott’s book acknowledges the poetics research program, and so, even more explicitly, does a new collection edited by Gary Bettinson and James Udden. The Poetics of Chinese Cinema gathers several essays that usefully test and stretch that frame of reference.

One standard challenge to the poetics approach is: How do you handle social, cultural, and political factors that impinge on film? I think the best way to answer this is to treat these factors as causal influences on a film’s production and reception. More specifically, in the production process, what we now call memes function as materials—subjects, themes, stereotypes, and common ideas circulating in the culture or the filmmaking institution. In the reception process, they provide conceptual structures that viewers can use in making their own sense of the films that they’re given. And such materials will necessarily include other art forms; films are constantly adapting and borrowing from literature, drama, and other media.

Both of these possibilities are vigorously explored in several essays in The Poetics of Chinese Cinema. For instance, Emilie Yueh-yu Yeh traces how Taiwanese and Japanese cultural materials are reworked by Hou Hsiao-hsien in his Ozu homage Café Lumière (2003). Peter Rist, a long-time student of Chinese painting, shows how Chen Kaige deploys cinematic means to revise landscape traditions to create a “Contemplative Modernism.” Victor Fan shows how the Hong Kong classic In the Face of Demolition (1960) adapts and revises a mode of narration already established in Cantonese theatre. In a clever piece called “Can Poetics Break Bricks?” Song Hwee Lim considers how digital technology feeds into a poetics of spectacle, specifically around slow-motion techniques that were emerging in pre-digital filmmaking.

Both of these possibilities are vigorously explored in several essays in The Poetics of Chinese Cinema. For instance, Emilie Yueh-yu Yeh traces how Taiwanese and Japanese cultural materials are reworked by Hou Hsiao-hsien in his Ozu homage Café Lumière (2003). Peter Rist, a long-time student of Chinese painting, shows how Chen Kaige deploys cinematic means to revise landscape traditions to create a “Contemplative Modernism.” Victor Fan shows how the Hong Kong classic In the Face of Demolition (1960) adapts and revises a mode of narration already established in Cantonese theatre. In a clever piece called “Can Poetics Break Bricks?” Song Hwee Lim considers how digital technology feeds into a poetics of spectacle, specifically around slow-motion techniques that were emerging in pre-digital filmmaking.

Tradition is a key concept in poetics, and the editors explore important ones in their own contributions. Gary Bettinson studies the emergence of Hong Kong puzzle films in works like Mad Detective (2007) and Wu Xia (2011). Are they simple imitation of Hollywood, or are they doing something different? Gary shows them to have complicated ties to local traditions of storytelling. Jim Udden focuses more on stylistics in his account of Fei Mu’s 1948 classic Spring in a Small Town, remade by Tian Zhuangzhuang in 2002. By examining staging, cutting, and voice-over, Jim shows that the earlier film is in many ways more “modern” than it’s usually thought and is somewhat more experimental than the remake.

It might seem that the “model” operas and plays of the Cultural Revolution, epitomized in The Red Detachment of Women (1971) would resist an aesthetic analysis; they’re determined, top-down fashion, by strict canons of political messaging. But Chris Berry’s contribution shows that they’re amenable to close analysis too. Like Soviet Socialist Realism, they may be programmatic in meaning, but not in every choice about framing, performance, cutting, and music. Indeed, the fact that people both inside and outside China (me included) still find them pleasurable probably owes something to their “Red Poetics.” And in true Hong Kong fashion, many filmmakers in that territory plundered those soundtracks with shameless, drop-the-needle panache.

I should probably add that I have an essay in this collection too. It’s called “Five Lessons from Stealth Poetics,” and it surveys things I’ve learned from studying cinema of the “three Chinas”: Hong Kong, Taiwan, and the Mainland. What attracted me were the films themselves, but in exploring them I was obliged to nuance and stretch the poetics approach. Readers of this blog know the trick: in talking about particular movies, I also try to show the virtues of the approach I favor. In other words, stealth poetics.

This is a good moment to pay tribute to Alexander Horwath, moving into his final nine or so months of directing the Austrian Film Museum. He has been a major figure in European film culture, through his inspired programming and leadership in publishing the books and DVDs issued by the Museum. We’re very grateful for all he has done for us and for film historians around the world.

P.S. 11 December 2016: Thanks to Mike Grost for a title correction and John Belton for a name correction!

King of Jazz (1930).

Genre ≠ Generic

The Shape of Night (Nakamuro Noboru, 1964).

DB here:

I didn’t plan it that way, but it turns out that a great many films I saw at this year’s Hong Kong International Film Festival would have to be categorized as genre pictures. Not, admittedly, Shu Kei’s episode of Beautiful 2014, which interweaves flashbacks and erotic reveries in a purely poetic fashion. And not Tsai Ming-liang’s “sequel” to Walker (2012, made for HKIFF), called, whimsically, Journey to the West. Here again, Lee Kang-sheng, robed as a Buddhist monk, steps slowly through landscapes, some so vast or opaque that you must play a sort of Where’s-Waldo game to find him. (You have plenty of time: there are only 14 shots in 53 minutes.)

But there were plenty of other films that counted as genre exercises. Yet they mixed their familiar features with local flavors and fresh treatment, reminding me that conventions can always be quickened by imaginative film artists.

Keeping the peace, in pieces

Black Coal, Thin Ice (2014).

Take, for instance, The Shape of Night, a 1966 street-crime movie from Shochiku, directed by Nakamura Noburo. Nakamura was the subject of a small retrospective at Tokyo’s FilmEx last year, and this item certainly makes one want to see more of his work. A more or less innocent girl falls in love with a yakuza, who forces her to become a prostitute. In abrupt, sometimes very brief flashbacks, she tells her life to a client who wants to rescue her. The film makes characteristically Japanese use of bold widescreen compositions, disjointed close-ups, and mixed voice-overs from her and the men in her life. In retrospect, everything we’ve seen has been seen in other movies, but Nakamura’s handling kept me continually gripped and often surprised.

Or take That Demon Within, a Hong Kong cop film that premiered at the festival’s close. Dante Lam has made several solid urban action pictures, especially Jiang Hu: The Triad Zone (2000), Beast Stalker (2008), Fire of Conscience (2010), and The Stool Pigeon (2010). They’re characterized by wild visuals and exceptionally brutal violence, and That Demon Within fits smoothly into his style. The new wrinkle is that a boy traumatized by the sight of police violence himself becomes a cop. He’s then haunted by the image of the cop from his past, while he’s also caught up in a search for a take-no-prisoners robber.

His hallucinations and disorientation are rendered through nearly every damn trick in the book, from upside-down shots and blurry color and focus to voices bouncing around the multichannel mix.

There are dreams, too (seems like almost every new film I saw had a dream sequence), and scenes under hypnosis, and men bursting into flame, and action sequences that are visceral in their shock value. I thought the movie careened out of control pretty early, and its nihilism wasn’t redeemed by an epilogue that assured us that this possessed policeman was, at moments, friendly and helpful. In this case, the storytelling innovations generated some confusion about exactly how the hero’s breakdown infused what was happening around him.

More consistent, largely because it didn’t try for the subjectivity of Lam’s film, was the Chinese cop movie Black Coal, Thin Ice. My friend Mike Walsh of Australia pointed out that the mainland cinema’s bleak realism seems to be starting to blend with traditional genre material. Director Diao Yinan explained, “My aim was not only to investigate a mystery and find out the truth about the people involved, but also to create a true representation of our new reality.” The opening crosscuts the grubby detail of bloody parcels churning through coal conveyors with a couple entwined in a final copulation before breaking off their relationship.

The mystery revolves around body parts that are showing up in coal shipments around one region. After a startling shootout in a hairdressing salon, the case remains unsolved for several years. The surviving detective, a shabby drunk, returns to track down the culprit, but in the meantime he runs into a frosty femme fatale. “He killed,” she says, “every man who loved me.” Needless to say, the detective falls for her too, especially after ice-skating with her. Diao’s film reminds us that you can create a neo-noir in two ways: By taking a mystery and dirtying it up, or taking concrete reality and probing the mysteries lurking in it.

There were even two Westerns. Another mainland movie, No Man’s Land, was unexpectedly savage coming from the director of the super-slick satires Crazy Stone (2006) and Crazy Racer (2009). Now Ning Hao has given us a bleakly farcical, Road-Warrior account of life on the Chinese prairie.

A wealthy lawyer brought out to the wasteland to negotiate a criminal case becomes embroiled in primal passions involving men with very large guns, very large trucks, impassive faces, and almost no sense of humor. It’s a black comedy of escalating payback (involving spitting and pissing), and it exudes sheer masculine nastiness. Completed four years ago, it found release only after extensive reshoots demanded by censors. Yet even in its milder state it remains true to the spirit of Sergio Leone’s jaunty grimness, bleached in umber sand and light.

Itching to see a Kurdish feminist political Western? You’ll find Hiner Saleem’s My Sweet Pepperland welcome. A tough policeman (= sheriff) is dispatched to a remote village in Kurdistan to keep order (= clean up the town). A young teacher (= schoolmarm) leaves her oppressive family to teach there as well. A warlord (= town boss) and his minions (= paid killers) have terrorized the locals, while marauding female guerillas (= outlaws) bring their fight into town.

These time-honored conventions shape a story of stubborn courage taking on complacent viciousness. In key scenes, our sheriff faces down big, hairy, scary killers.

USA frontier conventions, it turns out, work pretty well in a Muslim society too. The Hollywood Western’s continued embodiment of American values transfers easily to the former Iraq. “Our weapons are our honor,” the chief thug says, in a line that resonates through our history right up to now. Yet things we take for granted bring modern change to the wasteland. The sheriff assigns himself to the village in order to escape an arranged marriage, as the woman he finds there has done. She is vilified by both the locals and her male relatives, who would prefer death (hers) to dishonor (theirs). In the process, both he and she become heroic in a righteous, old-fashioned way.

A killer proposes a compromise while sneakily drawing his pistol. The cop shoots him and remarks: “I don’t do compromise.” Neither does My Sweet Pepperland.

Gangs of New York, and elsewhere

The Dreadnaught (1966).

From March to May, the Hong Kong Film Archive has been running a series, “Ways of the Underworld: Hong Kong Gangster Film as Genre.” It’s packed with classics (The Teahouse, To Be No. 1, City on Fire, Infernal Affairs) as well as several rarities (Absolute Monarch, Bald-Headed Betty, Lonely 15). I managed to catch three titles, all previously unknown to me.

The Dreadnaught (1966) has a familiar premise. Two orphan boys indulge in petty theft after the war. One, Chow, is caught but gets adopted by a policeman. He turns out a solid young citizen. Lee, the boy who escapes, grows up to be a triad. When the two re-meet, Lee is attracted to Chow’s stepsister. Some years later, Chow is now a cop and vows to smash Lee’s gang. After a struggle with his conscience, Lee agrees to help.

The film’s main attraction is the shamelessly flashy performance of Patrick Tse Yin. Tse would make his fame in the following year in Lung Kong’s Story of a Discharged Prisoner, famous as a primary source for A Better Tomorrow. With his sidelong smile, his endlessly waving cigarette, and the dark glasses he wears at all times, Tse in The Dreadnaught looks forward to Chow Yun-fat’s charismatic role as Mark in Woo’s masterpiece.

Another icon of the period is Alan Tang Kwong-wing. He played in over 100 films, mostly romances and triad dramas made in Taiwan. Westerners probably know him best as the producer of Wong Kar-wai’s first two features, As Tears Go By and Days of Being Wild. Wong had worked as a screenwriter for Tang. Onscreen, Tang had a suave, polished presence marked by his perfect coiffure; he was known as the Alain Delon of Hong Kong. His company, Wing-Scope, specialized in mob films during the late 1970s and early 1980s.

New York Chinatown (1982) shows Tang as a young hood whose ambitions to dominate the neighborhood are blocked by a rival gang. Eventually the police decide to let the two gangs decimate each other. This leads to an enjoyable, all-out showdown involving surprisingly heavy armaments. Shot quickly on location (passersby sometimes glance into the lens), the movie gives a rawer sense of street life than you get from most Hollywood films. There’s also a scene in which Tang, apparently attending Columbia part time, corrects a history professor lecturing on Western imperialism in China. Although the film circulates on cheap DVD in 1.33 format, it’s a widescreen production, and it was a pleasure to watch a fine 35mm print at the Archive.

The biggest revelation of the series for me was Tradition (1955), a Mandarin release. This is considered one of the earliest pure gangster films in local cinema. It’s a fascinating plot about a boy raised by a triad kingpin in the 1930s. When the godfather dies, the young Xiang is given power over the gang and the master’s household. Trying to be faithful to the old man’s principles, Xiang finds himself unable to control his master’s widow and daughter, who are led astray by the widow’s worldly, greedy sister. At the same time, Xiang must ally with other triads to smuggle aid to the forces fighting the invading Japanese. He is torn between devotion to tradition and the need to adapt to modern materialism and the impending world war.

Tradition is redolent of film noir, not only in the sister-in-law’s fatal ways (she seduces the old master’s weak son) but also in the film’s flashback construction. Tracking back from a ticking clock, the movie begins with Xiang meeting the master’s daughter after his gang has been decimated in a shootout. The film skips back to Xiang’s childhood and takes us up through the main action before a final bloody confrontation with police and the corrupt family members. At the end, the camera tracks up to the clock, closing off the whole action.

Tradition is redolent of film noir, not only in the sister-in-law’s fatal ways (she seduces the old master’s weak son) but also in the film’s flashback construction. Tracking back from a ticking clock, the movie begins with Xiang meeting the master’s daughter after his gang has been decimated in a shootout. The film skips back to Xiang’s childhood and takes us up through the main action before a final bloody confrontation with police and the corrupt family members. At the end, the camera tracks up to the clock, closing off the whole action.

Even more tightly buckled up are director Tang Huang’s obsessive hooks between scenes. A final line of dialogue is answered or echoed by the first line of the next scene; a closing door or character gesture links sequences in the manner of Lang’s M. Most daringly, when sister San starts to light a cigarette in one scene, we cut to her puffing on it in a tight close-up—a gesture that takes place in a new scene hours later. This and other admittedly gimmicky links look forward to Resnais’s elliptical matches on action in Muriel.

Fortunately for us, the Archive has published Always in the Dark: A Study of Hong Kong Gangster Films. Edited and partly written by Po Fung, it is an excellent collection of essays and interviews. It is in Chinese, but it includes a CD-ROM version in English. It’s available from the Archive’s Publications office.

Behind the scenes at Milkyway

Johnnie To and a recalcitrant crane during the shooting of Romancing in Thin Air.

Sometimes a genre film becomes a prestige picture. This happened, in spades, with The Grandmaster. If awards matter, Wong Kar-wai’s film has become the official best Asian film of 2013. I missed the Asian Film Awards in Macau (was watching early Farhadi films), but the event was a virtual sweep: seven top awards for The Grandmaster, including Best Picture and Best Director. After I got back home, the Hong Kong Film Awards gave the picture a staggering twelve prizes, everything from Best Picture to Best Sound.

Unhappily, nothing in either contest went to the other outstanding Hong Kong film I saw last year, Johnnie To Kei-fung’s Drug War. It lacked the obvious ambitions and surface sheen of Wong’s film. Many probably took it as merely a solid, efficient genre picture. I believe it’s an innovative and subtle piece of storytelling, as I tried to show here.

Mr. To presses on, as prolific as usual. He has finished shooting a sequel to Don’t Go Breaking My Heart, a rom-com that found success in the Mainland, and he’s currently filming a more unusual project in Canton. More on that shortly.

During the festival only one recent To/Milkway film was screened, The Blind Detective (I wrote about that here). But Ferris Lin, a young director from the Academy for Performing Arts, presented a very informative documentary feature on To and his Milkyway company. Boundless takes us behind the scenes on several productions, particularly Life without Principle, Romancing in Thin Air, and Drug War. It also incorporates interviews with To, his collaborators, and critics like Shu Kei.

Sitting at the monitor with his cigar, To may seem distant, but actually he is wholly engaged. We see him help push a crane out of the mud and shout commands to his staff. To confesses that he may scold too much, but the dedicated cooperation he gets confirms his demands. The team gives its all, as we learn when they explain the tension ruling the three days of rehearsal for the sequence-shot at the start of Breaking News. For The Mission, made at the time of Milkyway’s biggest slump, the actors supplied their own cars and costumes.

To remains a complete professional who has perfected his craft, albeit in the Hong Kong tradition of “just do it.” He doesn’t rely on storyboards or even shot-lists, only outlines of the action, and he adjusts to the demands of the locations. The Mission had no script, but the entire story and shot layout were in his head. For Exiled, he didn’t even have that much and simply began thinking when he stepped onto the set each day. It’s hard to believe that precise shot design and sly dramatic undercurrents can emerge from such an apparently unplanned approach. In its recording of To’s unique creative process, Boundless provides a vivid portrait of one of the world’s finest contemporary directors.

To continues to challenge himself. He is currently trying something else again, shooting a musical wholly in the studio. Its source, the 2009 play Design for Living, was written by and for the timeless Sylvia Chang Ai-chia. It won success in Hong Kong, Taiwan, and the Mainland. In the film Sylvia is joined by Chow Yun-fat, thus reuniting the stars of To’s 1989 breakout film All About Ah-Long. The project also indulges the director’s long-felt admiration for Jacques Demy. There is no 2014 film I’m looking forward to more keenly.

Special thanks to Shu Kei and Ferris Lin of the Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts. Thanks as well to Li Cheuk-to, Roger Garcia, and Crystal Yau, as well as all the staff and interns of HKIFF, and to Winnie Fu of the Hong Kong Film Archive.

Journey to the West (Tsai Ming-liang, 2014).