Archive for the 'National cinemas: China' Category

DIY dumplings

DB here in Madison, homebound from pneumonia, pining for Kristin and Ebertfest in Illinois:

The energetic Kevin Lee (when does he sleep?) has prepared a very nice video essay on Liu Jiayin’s Oxhide II at Moving Image Source.

The text is based partly on my blog entry on the movie from 2009. Kevin’s is something of an experimental piece, because it presents extracts from the entry in different voices and languages. I wasn’t able to narrate it because I’ve lost my voice, but the readers did better than I could have. Thanks to Evan Davis and Yuqian Yan, as well as the translators involved.

You can buy Liu’s first two Oxhide films on DVD at dGenerate Films, along with other important recent Chinese titles. Every university film department, and every serious lover of cinema, needs to own these movies. Liu shows what you can do with very few means but a lot of imagination. And Oxhide III is in the works.

And don’t forget to visit the videos of introductions and Q & A’s from this year’s Ebertfest here. Some are streaming, some are archived, all are interesting. As I typed this, Paul Fierlinger was talking about the background to My Dog Tulip.

Arthouse suspense, in big and small doses

Le Quattro Volte.

DB here:

As happened last year, I had to flee Hong Kong for medical reasons. Beset by a wracking cough, I took off three days early and upon returning to Madison wound up in hospital. Current diagnosis: pneumonia. Duration of stay: six nights and counting. A drag. But I’m lucky: no disorderly orderlies, no homicidal doctors injecting me with mind-control drugs (“You will watch only Brett Ratner films for the rest of your life. Sleep, sleep…”). I’m taken care of by expert, calm, and good-natured people. Expect no less from the best city for men’s health and care.

So I’ve been tardy in writing this final HK blog. I just wanted to talk about two extraordinary films I saw in my final days and bring up a scrap of news for followers of Chinese film.

First, the news. Liu Jiayin, of Oxhide fame, was in Hong Kong briefly to accept an Asian Film Financing Forum award for her screenplay Clean and Bright. The other winner was Li Ruijun, for his project Where Is My Home? Liu was about to visit the US for screenings at Redcat, under the sponsorship of the tireless Bérénice Reynaud, and at Cinema Pacific in Portland. I had a chance to talk briefly with her just before she departed.

First, the news. Liu Jiayin, of Oxhide fame, was in Hong Kong briefly to accept an Asian Film Financing Forum award for her screenplay Clean and Bright. The other winner was Li Ruijun, for his project Where Is My Home? Liu was about to visit the US for screenings at Redcat, under the sponsorship of the tireless Bérénice Reynaud, and at Cinema Pacific in Portland. I had a chance to talk briefly with her just before she departed.

Regular readers of this blog know my admiration for Liu’s two Oxhide films. The good news is that she is at work on Oxhide III. She wouldn’t say much about it, except that she is still reworking the script, but it sounded quite far along. In addition, she hopes to shoot Clean and Bright, a more orthodox film about a family, fairly soon as well. Oxhide IV is also planned, with the series running up to perhaps eight installments.

For more on Oxhide, including purchase information for the DVD, check Kevin Lee’s dGenerate Films website.

Leaving us hanging

Too often we think of suspense as specific to certain genres, but it’s actually a fundamental resource of all storytelling. Creating expectations about an upcoming event, sharpening them, and delaying their fulfillment–all these strategies are basic, I think, to narrative experience in general. Although some plots emphasize suspense more than others, even most “character-centered” tales wouldn’t engage us without a dose of it.

True, sometimes there’s a sort of bait-and-switch, as when suspense is conjured up but eventually dissolved. Sooner or later we realize Godot isn’t going to show up, or that Anna in L’Avventura is likely not to be found. In those cases, suspense has led us to another terrain, usually thematic, in which we’re invited to consider something more significant than learning the outcome of events. (Sometimes, though, snuffing out suspense is just a sign of slack, or Slacker, storytelling.)

Suspense is usually associated with popular plotting, so many people expect Serious Films to be lacking in suspense. Which makes it all the more interesting that Iran, one of the most-favored nations on the festival circuit, has made something of a specialty of suspenseful art movies.

We don’t recognize often enough that Kiarostami’s early films are often structured as suspenseful quests, from the boy’s attempt to return his schoolmate’s notebook in Where Is the Friend’s Home? to the final shot of Through the Olive Trees. His scripts for other directors convey this quality even more clearly. The Key is almost Griffithian in showing how a four-year-old boy struggles to rescue his younger brother when they’re locked in a kitchen with a gas leak. The Journey (Safar) is positively Ruth Rendellian: A headstrong middle-class father leaving Tehran with his family forces another car off the road and flees the scene. Instead of resting at a summer retreat, he returns obsessively to the place of the accident to check the progress of the investigation: Will he give himself away? And it isn’t just Kiarostami. Look at the suspense structure in Makhmalbaf’s Moment of Innocence, or Reza Mir-Karimi’s The Child and the Soldier, or Panahi’s The Circle.

What gives Iranian suspense films their weight is partly the fact that they don’t rely so much on the old standbys (chases, stalkings, cliffhanging rescues) but rather on psychological maneuvers, carried out largely through dialogue. Characters in these movies tend to talk a lot, pushing their concerns forward with a stubbornness that we seldom see in other national cinemas. People stick up for themselves, and the suspense comes from a clash of testimonies, pleas, and self-justifications. But it also comes from a moral dimension. My earlier examples depend on our assessing what we ought to happen (the hero of the Journey should be punished) versus what we might want to happen (he should escape). Add a dash of mystery, as we have in Through the Olive Trees (what is Tehereh thinking?) and A Taste of Cherry (what is the job Mr. Badi is hiring for?), and you have artistically ambitious filmmaking that exploits some very traditional resources of the art form.

These resources were on display in Asgar Farhadi’s earlier About Elly, which I praised in these pages two years ago. Nader and Simin, A Separation has a comparable power to seize and hold our interest. A wife fails to get a divorce and leaves the household, which includes not only her husband Nader but his Alzheimer’s-addled father and their daughter Termeh. Without Simin to care for his father, Nader hires Razieh, a working-class woman who must bring her little girl with her. Soon the job overwhelms Razieh and, for reasons not disclosed till later, she goes missing. Nader and Termeh find the old man tied to the bed, unconscious.

For this early stretch of the film, the helper Razieh trembles on the verge of hysteria, and only later do we learn why. When she returns to the apartment, she confronts Nader’s wrath, which leads to yet another turning point, but one whose significance we realize only later. To complicate matters, Razieh’s hot-headed husband becomes furious with everyone. As in About Elly, a great deal turns on what characters know at one precise moment, and our memory of when they learned something can be as elusive as theirs. And as in Henry James’ novels, much of the action is registered through the reactions of onlookers, notably the pensive daughter Termeh (below), who turns out in the final scene to be as important as any other figure in the film.

The suspense builds on many levels: the progress of the divorce, the decline of the old man, the court case that involves Razieh’s place in the household (did she steal money?), and above all the responsibility for a death. Some of these lines of action are shown resolved; a crucial one remains suspended. And that does, as often happens, oblige us to think more broadly about the film’s treatment of parent/ child relationships. We are left with an exceptionally rich film, one reflecting on class differences, religious ones, and the effects of adult problems on the children around them. Suspense not only feeds our hunger for story; it can also tease us to moral reflection, and Nader and Simin does just that.

No suspense?

How much can you purge suspense from a movie? And if you play it down, what do you put in its place to hold our interest?

One answer to these questions comes in Michelangelo Frammartino’s Le Quattro Volte. It is one of those sedate observational pieces that covers a year in the life of a village, with not much discernible dialogue but lots of lovely landscape shots. It has a cyclical rather than linear structure, beginning and ending with smoldering wood turned into charcoal–itself a metaphor for the inevitable transmutations that govern plants, animals, and men. We follow an old goatherd who eventually dies; his goats pay homage by climbing precariously to his tiny home and occupying it. A young goat is born soon after the old man’s death. The townsfolk erect an enormous Christmas tree, which at the end of the holiday is chopped down into bits, which will in turn becomes charcoal. If Nader and Simin exists largely in medium-shot, here the extreme long-shot dominates. There are no psychological interactions or dramatic issues of the sort we find in Fahradi’s films. In the rustic spirit of Rouquier’s Farrebique, we get the sheer successiveness of things, the fact that life is one damned, or placid, moment after another.

So suspense can be replaced by sheer consecutiveness, but the task then becomes to make things interesting. Frammartino does so through careful framing, evocative sound, and crisp storytelling technique. The goats pick their way up to the old man’s hillside apartment; they jostle around inside; cut to a shot of the old man’s head as he lies dead; cut to the church, with people filing out as the bell tolls. In addition , you can find suspense at more micro-levels, working not at the level of plot action as a whole but rather within and across particular scenes. After the goatherd’s death, we see another kid born: this is familiar, even clichéd, the rhythm of nature. We follow the kid’s efforts to assimilate to the herd. But as winter comes, the kid strays off, becomes isolated, and ends up lost and shivering. We must assume that he dies. So much for the great cycle of life.

At a still more microscopic level comes the shot that everyone remembers from Le Quattro Volte. It’s so salient that critics who seldom notice imagery can’t help but mention it. I won’t describe it in detail, so as not spoil the surprises, but suffice it to say that it involves a church procession, some intransigent goats, a pickup truck, and a resourceful dog. Reminiscent of Tati or Suleiman, this long shot depends on ratcheting up our expectations about how several converging events might develop, onscreen or off, and then fulfilling those expectations in startling ways. We might call the result spatial suspense: How will this composition-in-time finally resolve itself?

We should, then, never underestimate the power of suspense, even in those films which might seem to forswear it. Melodrama or pastoral, any genre can find a way to excite us by asking what can come next.

Catching up: By leaving Hong Kong early I missed the second screening of The Turin Horse; my first impressions are here. Since I wrote that, I learned that Cinema Scope has published Robert Koehler’s sensitive appreciation of the film and his enlightening interview with the cinematographer Fred Kelemen.

Nader and Sinin, A Separation.

Observations on Filmart (This is not a typo)

A modest display at Filmart, Hong Kong Convention Centre.

DB here, channeling an apparently apocryphal Soupy Sales line:

Kids, what starts with f and ends in art? No, not that. It’s Filmart, the annual trade gathering that kicks off the Hong Kong Film Festival. Add a space and a capital, and you have the main title of one of our books. Sometimes accidental cross-promotion can work out pretty well, as you see above.

Seriously, though, Filmart is a wonderful event. It includes an opening ceremony to launch the festival, the Asian financing forum known as HAF, the Asian Film Awards (covered a bit here), and a teeming meet-and-greet that sponsors panels, lunches, and hundreds of booths that allow media buyers and sellers to get together. I’ve covered Filmart in 2007, 2008, 2009, and 2010. Here are some comments and images from last week’s edition.

The shebang started with the ceremony introducing some of the opening films and their stars. Here the Filmart’s official hostess, Miriam Yeung, is about to go onstage to greet the audience.

And here at the ceremony are the three stars of Don’t Go Breaking My Heart, Gao Yuanyuan, Daniel Wu, and Louis Koo.

Ho Yuhang’s clever neo-noir Open Verdict was a highlight of the shorts collection Quattro Hong Kong 2. Here he is with his star, the radiant Kara Wai Ying-hung, Shaw Brothers action queen and star of both Open Verdict and Ho’s earlier feature Daybreak.

Filmart’s main business takes place in a vast hall, with companies’ displays lined up in rows and along aisles. Most firms have fairly modest stalls, but others are flamboyant, like these big boys for Mei Ah and Universe, two long-established Hong Kong production/ distribution companies.

But the place isn’t so big that you can’t run into old friends, like Margaret Pu (far right) and her colleagues Jack Lee and Dan Zhu from the Shanghai Film Festival.

More movers and shakers: Patrick Frater, CEO of Film Business Asia, and Peggy Chiao, producer (Trigram Films) and doyenne of Taiwanese New Cinema.

At Filmart one can always find some unclassifiable items, as witness the project pictured at the very end of this entry.

New Action on the Mainland

Most panels ran opposite film screenings, so I usually plumped for the movies. But I did attend an intriguing session on “Beyond Box Office: China: The World’s Largest Developing Market.” Sponsored by the Hong Kong Film New Action committee and moderated by Shanghai media executive Bill Zhang Ming, the panel included many Chinese figures and the American Ted Perkins, who has worked for both Warners and Universal and is now serving as executive VP of production for IDG China Media.

Some of the themes discussed echo things I talked about in the added chapters of Planet Hong Kong, but I garnered some new information as well.

*Several panelists pointed out that the stupendous growth in the Chinese box office, over 50% each year, demands that many new cinemas be built. The major cities have now got a good supply of screens, but now the third- and fourth-tier cities need to have more screens. Some commentators spoke of a “new five-year plan” aiming to upgrade and increase the nation’s screens.

*As in America and other countries, a few films typically garner the lion’s share of receipts; one panelist estimated that 80% of income stems from 20% of the films. For the foreseeable future, the big films, from China or the US, will drive the market.

*The growth of the market is even more remarkable given the comparatively small audience (around 20 million, one panelist surmised). Average ticket price is 32 renminbi, or about US$4.88.

*Hong Kong remains essential to the mainland market but also vulnerable. Films with local stars and directors can succeed, and Hong Kong is a key site for financing and packaging projects. But purely local films will remain low-budget items; the bigger films will be mainland co-productions, with some PRC talent and scenery on the screen.

*The popular audience, according to screenwriter-producer Qi Hai, is driven by female tastes: date movies are chosen by the woman, and family films are picked by mothers.

*Ted Perkins pointed out that although recent growth is good for all players, in any film industry there are always more funds in production than can be recouped overall. There will be winners and losers, especially if there’s an overabundance of production, as there currently is on the mainland. Although about 500 films were produced last year, more than half did not find theatrical release or screen in the best cinemas. (Panelists’ estimates of unseen or underseen titles varied from 250 to 400.) Marcus Lim provides a comparable set of figures.

*Some panelists opined that the market lacks directors and stars who are likely to provide success. One panelist estimated that only half a dozen directors have strong track records, and only one star, Ge You, can guarantee an audience.

*Most panelists agreed that 3D was not viable for most films, but in China the new format can help the business in an unusual way. Historically, most mainlanders couldn’t afford going to films, so they aren’t in the habit of attending theatres. They watch films on video or on the Net. Curiosity about 3D may attract new cinemagoers, “educating” spectators to the pleasures of seeing movies on the big screen.

*Most big countries have a well-structured pattern of “windows,” whereby a film moves from the theatre to video, cable, and online. But in China, the expansion of screens is occurring simultaneously with the growth of online distribution, with the danger of piracy. The Chinese will have to come to grips with decisions about pricing and more stable windows.

Seldom do we have a chance to realize that we’re witnessing a historic change in the global film industry. The rise of China is such an event, and film historians should be watching the unfolding process closely.

Changing the film ecology

The Jockey Club Cine Academy, formed last summer, is an educational enterprise guided by the HKIFF Society and funded by the Hong Kong Jockey Club Charities Trust. It’s a three-year program aiming to increase film literacy among young people. The Academy held a major event during Filmart, a nearly three-hour master class with Jia Zhangke, director of Platform, The World, Still Life, and most recently I Wish I Knew. High school students made up a large part of the audience.

Researcher and editor Wong Ain-ling (above, with Jia) interviewed him about his career and then opened things up for questions. Here are a few points Jia made.

*His recent turn toward documentary filmmaking isn’t a new development for him. When he was starting out, documentaries were the most dynamic part of the PRC film scene. Although the films captured aspects of contemporary life ignored by mainstream movies, they were seldom watched by audiences. So the question for Jia became: “How to change our film ecology?”

He has used a documentary project to spark a fiction feature. In Public (2001) became a draft for Unknown Pleasures. Jia enjoyed eliminating dialogue and narration from his documentaries, relying on peoples’ faces and situations to convey ideas. Critics complained that documentarists couldn’t tell stories, but he wanted mainland audiences to learn to find the latent emotions in the scenes, the “poetic” side of realistic cinema.

*His early films incorporated popular music, including Taiwanese tunes sung by Teresa Teng. Why? During the 1980s and 1990s, mounted loudspeakers broadcast a lot of Mandarin pop songs, making this music just part of a city’s ambience. This was something he exploited in his first feature, Xiao Wu.

*Jia had arguments with censors on his first three features, and those films weren’t widely seen. But in 2004, the censorship system changed, mostly for the better. Yet distributors still block films shot on video from being shown in cinemas, creating what Jia called a “technical censorship.”

*The reports are true: He is making a martial arts film with Johnnie To’s Milkyway firm. Jia wants to examine the imperial system in the period around 1900. He would like to follow it with another historical film, this one about Hong Kong in 1949, centering on two characters, a Communist and a KMT Nationalist.

Like Hong Kong itself, Filmart has a pulsating energy and offers an overwhelming array of choices: you can watch movies, attend events, and just gawk. You must run to keep up. That’s as it should be.

For more coverage of industry doings at Filmart, see Liz Shackleton’s rundown at Screen International (may be proprietary). Another story in Screen International mulls over the prospect that China could fairly soon become the world’s biggest market. See as well several items at Film Business Asia, particularly Stephen Cremin’s article on Chinese coproductions. For our takes on some Jia Zhangke films, you can go to this category.

PS 31 March (HK time): I should have mentioned what the New Action panel did not: Piracy. The LA Times has a good recent article on DVD bootlegging in the PRC, raising the crucial factor I’ve heard mentioned as well: the role of the People’s Liberation Army.

Bullets from the East

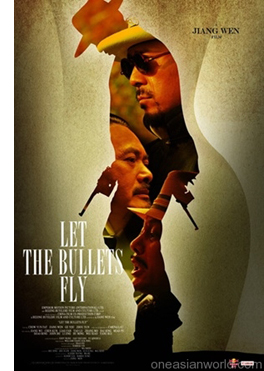

Chow Yun-fat, Jiang Wen, and Ge You in Let the Bullets Fly (2010).

DB here:

It’s mid-March, so it must be the first of a string of entries from the Hong Kong International Film Festival, a place I’ve visited regularly since 1995.

This year, the Boy Scout hotel was too full to take me, so I’ve wound up in the YMCA on Salisbury Road. If you want glimpses of the neighborhood, just watch Peter Greenaway’s Pillow Book. It’s as if he ventured only a few blocks from his hotel. (Unlikely to have been my Y; more likely he based himself at the far tonier Peninsula alongside.)

The Japanese quake, tsunami, and nuclear meltdowns are much on local people’s minds. Some people are worried that the light rains punctuating every day are carrying radiation, but so far there doesn’t seem any danger. I had planned to stop over in Tokyo on my way here, but after the quake struck I changed my flights. The good news is that the friends in Tokyo and Nagoya I’d planned to visit are safe.

Let the Bullets Fly, China’s biggest locally produced box-office hit to date was playing in a cycle of screenings devoted to major candidates for the Asian Film Awards, to be given Monday night. It was screened in the Grand cinema complex with Shaw Sound, which makes your seat vibrate in sync with the lower frequencies. This enhances any movie, I suppose. The Grand is located in Elements, a hypermall that has lost none of its weirdness. (The mazelike structure has four zones, Earth, Air, Fire, and Water.) I was pleased to note that the Grease Trap Room is still doing its duty.

Let the Bullets Fly, China’s biggest locally produced box-office hit to date was playing in a cycle of screenings devoted to major candidates for the Asian Film Awards, to be given Monday night. It was screened in the Grand cinema complex with Shaw Sound, which makes your seat vibrate in sync with the lower frequencies. This enhances any movie, I suppose. The Grand is located in Elements, a hypermall that has lost none of its weirdness. (The mazelike structure has four zones, Earth, Air, Fire, and Water.) I was pleased to note that the Grease Trap Room is still doing its duty.

Actor-turned-director Jiang Wen is one of the PRC’s most ambitious and intelligent directors. I’ve admired his In the Heat of the Sun (1994) and Devils on the Doorstep (2000, to be shown in its long version during the festival). Our blog files contain my impressions of his sumptuous, somewhat mystifying The Sun Also Rises (2007). But that film was a huge financial failure, and it’s generally agreed that he needed a hit. He provided it in Let the Bullets Fly.

This wild, cynical Eastern Western is set, the opening title tells us, in 1920 when warlords ruled great stretches of China. By choosing this pre-Communist era, Jiang is free to parade all manner of duplicity, amorality, and aggression, while still suggesting a modicum of revolutionary sensibility at the end. Pocky Zhang leads a band of marauders who capture a conman, Ma, and his wife. Ma’s swindle of choice is bribing officials to appoint him governor of a remote area and then squeezing taxes out of the locals before fleeing to his next target.

Captured, Ma pretends to be merely an advisor to the real governor, whom he claims was killed during the raid. Bandit Zhang decides to try his hand at governing and so brings his gang, along with Ma and his wife, to claim the post at Goose Town. There he butts heads with the local gang leader Huang Silang. The bulk of the plot presents an escalating series of comic and violent encounters between bandit-as-governor and warlord-as-godfather. Things come to a head when Huang offers Pocky Zhang a huge sum of silver to kill the biggest threat to his rule, none other than Pocky Zhang himself.

The beginning evokes Duck You Sucker, plunging us into Pocky’s raid on a steam train carriage (pulled by horses). As his gang races along with the carriage, we get the tone of lilting swagger that opened The Sun Also Rises. Very fast cutting, rushing tracking shots, and a bouncy musical score climax in Pocky’s adroit use of a flying axe to derail the carriage and send it flipping majestically into the river. Soon the bravado action gives way to games of deceit and disguise. Ma saves his skin by pretending to be his aide Tang. Pocky assumes the identity of the governor, while Huang has an identical double he will use as a decoy. Everybody suspects, rightly, that everybody else is lying. Even Pocky Zhang isn’t really pock-faced. (An alternate translation calls him Scarface Zhang. But he isn’t scarfaced either.)

The game is played out in fusillades of banter that are, my Chinese friends assure me, packed with gags and wordplay. Maybe it should be called Let the Bullshit Fly. Characters rattle out brief lines or single words in a thrumming rhythm that is underscored by frantic back-and-forth cutting: cinematic stichomythia. Overall, the film’s average shot length is about two seconds.

Let the Bullets Fly is a showcase for action scenes, dizzying dialogue, clever running gags (the bird-whistles that Zhang’s gang uses to communicate), and perhaps above all star performances. Three popular male actors dominate the proceedings, leaving poor Carina Lau as Ma’s wife little to do but look seductive and die early on. Ge You as Ma is querulous but cunning. Ma’s death, buried in a mountain of silver currency, balances exaggerated imagery and gory gags with a gentler humor as he tries to utter some last words. Chow Yun-fat hams it up agreeably in a dual role, as gangster Huang and his hapless, nattering double.

Central of course is Jiang himself as Pocky Zhang, a crack shot and an utterly confident, resourceful leader who spares a little time to eye the ladies. Director supremo Feng Xiaogang shows up in the prologue playing the unfortunate counselor Tang. His drowning in the train carriage carries a peculiar extra-filmic resonance: by the end of its run, Bullets broke the box-office record set by Feng’s Aftershock earlier in the year.

More generally, the film shows how filmmakers on the mainland are broadening and fine-tuning popular genres. Having mastered the costume epic, they have branched out, winning audiences with modernized comedies and relationship romances (e.g., Feng’s recent If You Are the One films). So why not Westerns too? After all, the genre has been transplanted to Italy, Germany, Spain, and even, some would say, Russia and India. Hong Kong’s Peace Hotel and South Korea’s The Good, the Bad, and the Weird showed that frontier conventions could be adapted for Asian audiences. Let the Bullets Fly seems to me not up to Jiang’s best work, and on one viewing, I found it occasionally monotonous and mechanical. Still, it should underwrite his more ambitious projects and encourage other directors to try their hands at a format that seems inexhaustible.

Thanks to Athena Tsui and Li Cheuk-to for sharing ideas over dim sum, and Shelly Kraicer for further clarification of names. For informative reviews of Bullets, see Ross Chen’s entry at lovehkfilm.com; James Marsh’s at twitchfilm; and Derek Elley’s commentary at Film Business Asia. This PRC review, in English, faults Jiang for his “unduly high opinion of himself.”

Speaking of Hong Kong: In case you didn’t know, the second, digital edition of my book Planet Hong Kong: Popular Cinema and the Art of Entertainment, is available here. Brace yourself for reports on my shameless efforts to hawk this item as the festival proceeds.

PS 21 March: Thanks to Luo Jin for a name and date correction.

A point of pilgrimage for every Hong Kong-addled cinephile: Chungking Mansions, on Nathan Road. You can see bamboo scaffolding on the left side.