Archive for the 'National cinemas: China' Category

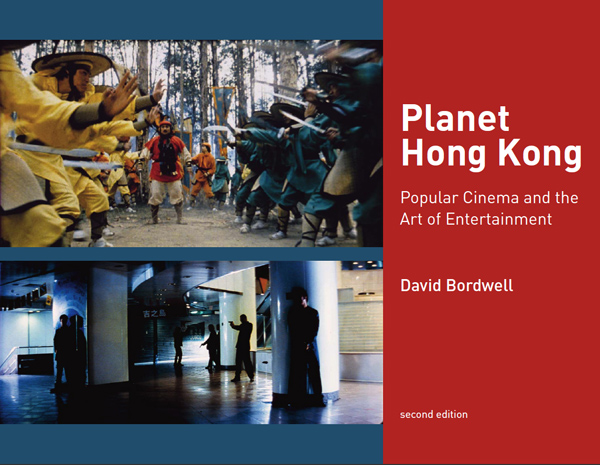

PLANET HONG KONG now in cyberspace

DB here:

Planet Hong Kong, in a second edition, is now available as a pdf file. It can be ordered on this page, which gives more information about the new version and reprints the 2000 Preface. I take this opportunity to thank Meg Hamel, who edited and designed the book and put it online.

As a sort of celebration, for a short while I’ll run a daily string of entries about Hong Kong cinema. These go beyond the book in dealing with things I didn’t have a chance to raise in the text. This is the first one. The second, a quick overview of the decline of the industry, is here. The third, on principles of HK action cinema, is here. The fourth, a photo portfolio of HK stars, is here. The following ones deal with western fandom, some Hong Kong directors, and final reflections on film festivals and a list of other intriguing movies. Thanks to Kristin for stepping aside and postponing her entry on 3D.

± 25 classics: A cheat sheet

Rouge (1988).

I have an aversion to list-making (some day I’ll explain), but I’m often asked to recommend Hong Kong movies to people wanting a quick start. So I’m launching this suite of daily entries around Planet Hong Kong by charting some widely recognized high points in this effervescent cinema.

Some items are important for their historical influence, some for their intrinsic quality, some for both. I’m restricting myself to the years after 1960, although there are several influential and powerful films before that (e.g., In the Face of Demolition, 1953). Still, if you want a fair sample of this cinema’s output you must sample these more or less official classics. If the bug bites, you can supplement them with other items that I’ll mention in passing here and in the days to come. Several of these films are discussed in more detail in the book, and most are available on DVD.

The Wild, Wild Rose (1960): Cathay (to use its shortest name) was one of the two major companies of the 1960s and in this brassy show-business drama Grace Chang (Ge Lan) had her defining role as the Carmen of the nightclub scene. Another Grace Chang classic is Mambo Girl (1957), and you can get a sense of the gorgeous star culture of Cathay by seeing her and other top actresses in Sun, Moon, and Star (1961), sort of a Hong Kong Gone with the Wind.

The Love Eterne (1963, above): This adaptation of the “plum-blossom” opera was given lavish treatment by the Shaw Brothers studio, the major studio of the period. Li Han-hsiang’s spectacle of colorful costumes, big studio sets, and gender masquerade won several awards and helped establish Hong Kong films across Asian markets. Li went on to make many other sumptuous costume pictures, as I discuss briefly here and in subsequent entries. This web essay focuses on Shaws’ anamorphic output.

Come Drink with Me (1966): The first Shaw entry in its new martial arts cycle, pioneered by King Hu. In an inn various characters in disguise meet and bluff one another; eventually the woman warrior Golden Swallow takes on all comers. Strictly speaking, King Hu’s other films belong to Taiwanese cinema, but he is one of the greatest of all Chinese directors, so you will naturally want to see Dragon Gate Inn (1967), The Fate of Lee Khan (1973), The Valiant Ones (1975), and his official masterpiece, A Touch of Zen (1971). I give him a fair amount of space in Planet Hong Kong because of his historical importance and his innovations in the aesthetics of action. I talk a little about those innovations here.

Golden Swallow (1968): Shaws’ dominant director from the late 1960s onward, Chang Cheh specialized in films of “staunch masculinity,” martial arts pictures that replaced the female-centered romances and opera films. Golden Swallow shows the woman warrior, the nominal protagonist, muscled aside by a typical brooding Chang hero—Jimmy Wang Yu, acting as if he still nursed a grudge from being The One-Armed Swordsman (1967). Later Chang developed the masculine pairing of Ti Lung and David Chiang Da-wei (Blood Brothers, 1973) and the brawny teamwork of what came to be known in the West as the Five Venoms (as in Invincible Shaolin, 1978).

Fist of Fury (1972): Child star Bruce Lee came home from Hollywood, and his first kung-fu film, The Big Boss (1971), was a sensation. The most influential star in all Hong Kong cinema, Lee stands at the center of his classics; the plots, staging, and shooting simply set off his glowering charisma. Fist of Fury provides a string of archetypal scenes: he wipes the floor of a dojo with its students and master, he kicks to splinters a sign barring Chinese from a park, and he ends his life by hurling himself, shouting, into a hail of bullets. Remade as the no less enjoyable Fist of Legend (1994) with Jet Li.

The House of 72 Tenants (1973): The success of Shaw Brothers’ export-driven Mandarin-language product led to a decline in films made in Cantonese, the local language. (Hong Kong audiences heard Bruce Lee dubbed into Mandarin.) 72 Tenants, based on a popular play, brought back Cantonese cinema in a crowd-pleasing guise. Under the direction of veteran Chor Yuen, the crisscrossed stories of neighbors became an enduring reference point for local cinema—cited again last Lunar New Year in 72 Tenants of Prosperity.

The Private Eyes (1976): Another victory for Cantonese vernacular cinema. The Hui brothers, popular from television, brought their episodic sight-gag comedy to the big screen and were among the biggest stars of the 1970s. There are many classic scenes, including Michael and Sam’s sleight of hand with candies, a shark attack in a kitchen, and a bout of chicken aerobics—plus a weird contagion of neck braces. See also Security Unlimited (1981) and, for fairly daring mockery of Beijing, The Front Page (1990).

The 36th Chamber of Shaolin (1978). As his employer Shaw Studios was fading from the scene, Lau Kar-leung (aka Liu Chia-liang) created in nearly twenty films a virtual encyclopedia of the kung-fu tradition. Any choice among the films is arbitrary (I’ll mention more in a future entry), but let this exuberant display of color, movement, and emotion stand as an outstanding accomplishment. A young man burning with rebellion enters the Shaolin monastery. Through persistence and discipline he achieves the highest distinction and returns to his home town to fight the Manchu oppressors. Featuring the director’s brother Gordon Lau Kar-fai and Lo Lieh, both martial-arts icons.

Young Master (1980): Jackie Chan’s comic kung-fu caught fire in Snake in the Eagle’s Shadow (1978) and Drunken Master (1978). Young Master is a prime instance of his rubbery energy and bottomless masochism. It benefits from extended byplay with Yuen Biao, splendid jumper, and Shek Kin, patriarch of the Hong Kong martial arts movie. Soon Jackie would show both ambition and directorial prowess in Project A (1983), his leap into big budgets and pan-Asian superstardom.

Aces Go Places (1982): The most successful franchise in Hong Kong history was launched by this jaunty action comedy, stuffed with pratfalls and high-tech chases. The buffoonery was carried off by an unruffled Sam Hui Koon-kit and a sprightly Sylvia Chang Ai-chia, not to mention the robots. Any film is improved by robots.

Boat People (1982): Ann Hui On-wah, a practitioner of serious drama for over thirty years, established her reputation in world cinema with this poignant story about a photographer’s discovery of children cast out by war. Her earlier film about Vietnamese refugees, Story of Woo Viet (1981), gave TV actor Chow Yun-fat his first major film role. Another characteristic Hui work is Song of the Exile (1990).

Zu: Warriors of the Magic Mountain (1983) Which early film by Tsui Hark to choose? The Butterfly Murders (1979) looks forward to his recent Detective Dee; the hectic We’re Going to Eat You (1980) suggests Romero turned loose in China; many critics pick Dangerous Encounter—First Kind (1980), a rough-edged Buñuelian indictment of class differences. With Zu, however, Tsui showed his resolve to update classic genres, in this case the Cantonese swordplay fantasy, using modern technique and special effects—a trend that has continued right up to the recent Storm Warriors (2010). Go here for more thoughts on Tsui.

Police Story (1985): Possibly Jackie Chan’s directorial masterpiece. A rip-roaring auto chase through a hillside shantytown, capped by a runaway bus, would be the climax of any other movie, but here it’s just for openers. The film ends with a fight in a shopping mall that, for precision and visceral impact, deserves to be ranked with the great sequences in film history. More on this scene here.

Peking Opera Blues (1986): The woman warrior’s shining hour, complete with the obligatory cross-dressing. Tsui Hark moves toward historical action/ adventure in a breathless movie that showcases three great beauties: Brigitte Lin Ching-hsia, Sally Yeh, and Cherie Chung Cho-hung.

A Better Tomorrow (1986): The film that defined a generation and cemented Chow Yun-fat’s star stature. John Woo came out of Taiwanese exile to make a film that revived the Chang Cheh spirit of brotherhood, made even more romantically doomed by the idea that Hong Kong was living on borrowed time.

Rouge (1988): A courtesan’s ghost revisits contemporary Hong Kong and finds that no one else is willing to die for love—not even the man who pledged to join her in death. Stanley Kwan Kam-pang’s delicate yet straightforward handling of the plot, refusing all special effects, gives an extra poignancy. Others would suggest Kwan’s Centre Stage (aka Actress, 1992), a biographical study of the great film star Ruan Lingyu.

The Killer (1989): The Chow/ Woo collaboration that brought them to the attention of the West. Often imitated, at home and abroad, the original retains its bold lyricism and outlandish emotion: crime and punishment as (mostly male) melodrama, accompanied by cadenzas of annihilation. To be supplemented by A Better Tomorrow II (1987), Bullet in the Head (1990), and Hard Boiled (1992), all of which brought awed fanboys to their knees.

God of Gamblers (1989): A financial triumph for bad-boy producer/director Wong Jing and the definitive gaming movie for a town that loves a bet. Shamelessly cheesy in its plot mechanisms, surprisingly elegant in its direction, the movie yanks us from laughter to pathos. Plus Chow Yun-fat in a tuxedo. To be seen alongside Stephen Chow Sing-chi’s parody All for the Winner (1990).

Days of Being Wild (1990). Wong Kar-wai’s breakthrough film about young people adrift in the early 1960s. A dazzling array of stars (Leslie Cheung Kwok-wing, Maggie Cheung Man-yuk, Andy Lau Tak-wah, et al.) creates a languid movie about the magnetic pull of selfish passion. For many local critics, the most important film of the last thirty years. I discuss a rare alternate version of the film here.

Once Upon a Time in China (1991): Tsui Hark doing Movie Brat revisionism again, this time with the Southern Chinese folk hero Wong Fei-hong. This flamboyant exercise in fervent nationalism ushered Mainland wushu champion Jet Li onto the world stage. If Bruce Lee radiated a cocky sexual energy, this film helped establish Li’s star image as a shy and chaste warrior.

Chungking Express (1994)/ Ashes of Time (1994): A coin-flip. The first showed that Wong Kar-wai could make a movie fast, cheap, and charming. The second showed that a swordplay film could be drenched in romantic longing. Both bristled with audacious storytelling tactics. Chungking spliced two stories together (prefigured in the way characters bump into each other), while Ashes zigzagged and spiraled in time, refusing plot certainties but offering a hypnotic reverie instead. Western critics and fans, notably one Q. Tarantino, sat up and noticed. PHK devotes an entire section to Chungking; go here for more on Ashes of Time.

The Mission (1999): Johnnie To Kei-fung’s stealth classic. Made on a shoestring, shot in less than three weeks (without a developed script), filled with great character actors, this ascetic polar has some of the subtlest plot twists in Hong Kong film. If Kitano Takeshi in his prime had made a Hong Kong film, it might look like this. Of course the mall shootout has become a classic.

Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000): This US-Hong Kong-Taiwan project showed that the world was ready for the wuxia pian, or film of heroic chivalry. CTHD became the top-grossing foreign-language film in U. S. history. The versatile Ang Lee centered the drama on two couples, one young and one older, and their life in the jianghu–that virtual, larger-than-life world of forests and rivers that tests warriors’ righteousness. Lee’s film prodded Zhang Yimou to make the artier Hero (2003), first in a procession of historical dramas that helped revive the Mainland film industry.

In the Mood for Love (2000): Julia Roberts’ favorite movie, I’m told. Revisiting the period and perhaps some of the characters of Days of Being Wild, Wong Kar-wai evokes muffled yearning through averted glances, hidden faces, radiant costumes, and a typically spine-tingling soundtrack. This Cannes prizewinner was given a sequel, 2046 (2004), that is harsher but no less romantic in its commitment to cherishing the past.

Infernal Affairs trilogy (2002-2003): A deliberate effort to break away from the hell-for-leather action film, the IA trio showed that Hong Kong filmmakers could construct a taut, restrained crime plot. The first installment is a compact, efficient suspense exercise, the second a wide-ranging exploration of betrayal, and the third a fairly daring experiment in time-shifting and subjectivity. Many recent crime films have taken their cues from the trilogy’s huge box-office success. Portions were remade as The Departed, and for once it was the Hollywood movie that was overblown (not least the contribution of Mr. Nicholson). I set down some thoughts on the two versions here and here.

Kung Fu Hustle (2004): Stephen Chow purists may consider it a case of comedic elephantiasis, but this big-budget extravaganza is historically significant for winning worldwide distribution and big box-office. Kung Fu Hustle is also packed with engaging CGI-enhanced gags, on every scale from tenement demolition to cobra-smooching. One of the funniest scenes will encourage you not to use the phrase “hair on fire.” The even more inventive Shaolin Soccer (2001) was Chow’s previous step toward making movies at once China-friendly and globally marketable; not for nothing is his company called The Star Overseas.

Later this week I’ll offer a list of other Hong Kong films that I think are worth attention. (So wait until you’ve seen all my picks before writing me to point out titles I’ve omitted here!) And somewhere I’ll try to wedge in some outstanding sequences. This is nothing if not a cinema of rousing set-pieces.

Nearly all the films I mention are available on DVD, with European and American editions usually being of superior quality to Hong Kong editions. Many of the filmmakers mentioned are discussed in other entries on our site; check the Directors category on the right.

In 2005, Chinese critics assembled a list of the 103 best films from the PRC, Taiwan, and Hong Kong. That list can be found here.

PS 3 Feb: Another list of top Chinese films, tilted somewhat toward Taiwan, is here.

A Better Tomorrow (1986).

Vancouver: Final freeze-frames

DB here:

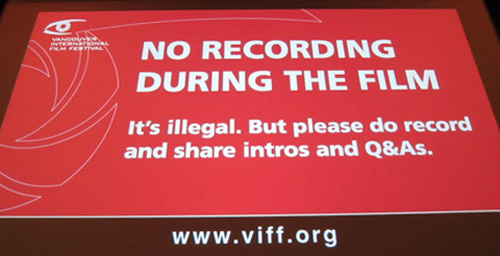

This slide, which appeared briefly before every screening at the Vancouver International Film Festival, epitomizes one of the event’s virtues: quiet sanity. Of course we must discourage people from recording the movie. But just as surely, we want people to photograph the filmmakers and record their comments and get the word out. Spreading the news benefits everybody, particularly the filmmakers.

Indeed, the whole VIFF clambake is run as efficiently as anyone can imagine. Want to get into a film? Very likely you will. A movie is getting buzz? Likely as not, extra screenings will be mounted. Annoyed by mobile devices in the throngs around you? House managers firmly ask people to shut them off. Now. Yet there’s nothing aggressive here. This is a city in which the buses preface the flashing notice “Out of Service” with an apologetic “Sorry.” A Manhattan bus would say, “You’re outta luck, pal.”

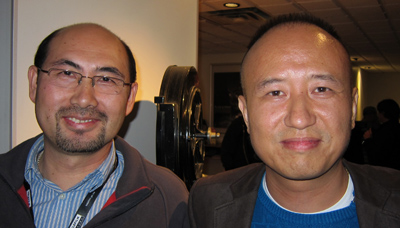

Now that Kristin and I are back, we know whom to thank: the organizers, the programmers, the office staff, and the inexhaustibly cheerful volunteers (700 strong). Below are Alan Franey, Festival Director, and PoChu AuYeung, Program Manager and Senior Programmer.

Come down for breakfast and you’re likely to run into Foreign Guest Coordinator Theresa Ho and Hospitality Suite Manager Eunhee Cha Brown. Dreyfus is usually not far away.

Then there’s the multi-talented Lillooet Fox, Food and Beverage Coordinator, waffle wrangler, and music supervisor for Amazon Falls, playing in the festival.

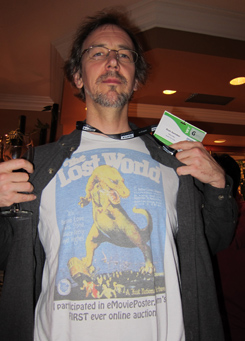

Ever notice how film people are always “on,” always subtly copping stances and looks from movies? Shelly Kraicer, Dragons & Tigers programmer, does his dressed-down version of Lars von Trier.

Speaking of T-shirts, nothing beats telling a story with your thorax. Consider Sean Axmaker (Parallax View) and Robert Koehler (Anaheim International Film Festival) and Raymond Phathanavirangoon (Hong Kong International Film Festival).

At happy hour, the waffles vanish and adult beverages come into their own. VIFF programmer and editor of Cinema Scope Mark Peranson hoists one with Variety critic (and University of Wisconsin alum) Rob Nelson.

Of course everyone mingles with filmmakers. Freddie Wong, director of The Drunkard, is reunited with Bérénice Reynaud, Cal Arts professor and author of a book on City of Sadness.

Tony Rayns, veteran Dragons and Tigers programmer, is flanked by Bong Joon-ho on the left, Denis Côté (Curling) across the table, and Mark Peranson on the right. Geoff Gardner and Jack Vermee are in the distance. Again, the cinephiles pay homage to a shot, in this case from Hong Sangsoo’s Oki’s Movie.

Jim Udden, another Badger and Professor at Gettysburg College (and author of a book on Hou Hsiao-hsien), talks Taiwanese film with director David Verbeek (R U There?).

Trustworthy translator Alex Fu and director Zhu Wen (Thomas Mao).

Takahashi Nazuki and Abe Saori celebrate after their screening of Icarus Under the Sun.

Meanwhile, Geoff Gardner (watch for his VIFF coverage in Urban Cinefile) finds that a rival venue has conjured up a star from another era.

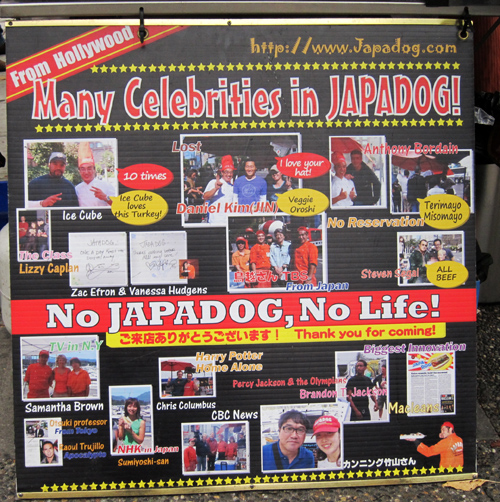

And although we left Vancouver all too soon, we’ll always have Japadog. Not everything in Vancouver is quiet sanity, but even the nuttiness is quite easygoing.

I recommend no. 4, Spicy Cheese Terimayo.

Seduced by structure

Mysteries of Lisbon.

DB here:

If you’re hungry to learn about the ways films can tell stories, a festival provides a feast. A huge array of narrative strategies is spread out for your delectation. You won’t like every movie you see, but thinking about the mechanics of each one can deepen your experience of it, as well as your appreciation for just how wide cinema’s resources can be. You also get to see how more unusual approaches to storytelling are often imaginative revisions of more traditional strategies.

We can usefully think about narrative from three angles. We can study the story world that a film conjures up: the characters, places, and actions we encounter. We can analyze plot structure, the distinct parts that are put together sequentially. They might be scenes or sequences or larger-scale parts, like the Hollywood screenwriters’ “acts.” We can also analyze narration, the patterned, moment-by-moment process of presenting the story world and the plot structure. Think of a narrative as like a building. The building’s furnishings correspond to the story world, and the architectural design of the building, plan and elevation, is like plot structure. Our real-time pathway through the building, from the front doorway into its depths, corresponds to narration.

The Vancouver International Film Festival that Kristin and I have been visiting offers a banquet of storytelling devices—some quite traditional, some fairly fresh. I’ll just survey some aspects of structure that I found intriguing.

The longest distance between points

The Chinese blockbuster Aftershock, centering on the 1976 earthquake that struck Tangshan, has earned some complaints about weepiness and jokes about “Afterschlock.” Perhaps melodrama makes many critics uncomfortable. They seem more at home with comedy and noirish crime stories, perhaps because the emotions stirred by these are bracketed by a degree of intellectual distance. But tell a story about a happy family split apart by a catastrophe; show a mother forced to choose between saving her son and saving her daughter; show that the girl miraculously escapes death; present her raised by a pair of new parents; and dwell on the fact that her mother, living elsewhere, expects never to see her again—do all this, and you court mockery.

Well, mockery from everybody except the hundreds of thousands of people who have always enjoyed these situations. Aftershock is now the biggest box-office success in Chinese film history (presumably using today’s currency standards). Whatever the film owes to Chinese traditions, it is easily understandable in a Western context. Stories based on pseudo-orphans, separated siblings, and parents forced to give up children have long been sure-fire. Les Deux orphelines, an 1874 play, is one strong prototype. This pathetic tale of two sisters torn apart in post-revolutionary Paris was adapted by many directors, including Griffith (Orphans of the Storm, 1921). Feuillade developed similar motifs in Les Deux gamines (1921), L’Orpheline (1921), and Parisette (1922). A mother’s loss of her children through accident or social oppression is another stock situation, seen in sublime form in Mizoguchi’s Sansho the Bailiff. The obligation to pick a child to save is at the core of Sophie’s Choice, a more highbrow melodrama. Likewise, the discovery of unexpected kinship forms the climax of many stories, from Oedipus Rex to Twelfth Night and beyond.

You may call these conventions hackneyed, but it would be better to call them tried and true—proven effective by centuries of deployment, counting on emotions aroused by ties of love and blood. Such situations would be good candidates for narrative universals, which can be reshaped by local cultural pressures.

The premise of a fragmented family bears chiefly on the story world. The filmmaker still must choose how to structure the plot. For Aftershock, director Feng Xiaogang and his collaborators settled on the time-honored route: parallel stories across the years, shown by means of crosscutting. After the quake, scenes of the mother and son alternate with scenes showing the girl’s rescue and her life with her adopted parents, both soldiers in the People’s Liberation Army. For about the first sixty minutes, the segments are rather long, but after that shorter scenes from each plot line are intercut. The son moves off to a separate life, but his success as an entrepreneur is given short shrift. The plot concentrates on the daughter’s college career, her sometimes stormy relation with her foster parents, and her unexpected pregnancy. In the meantime, the mother survives, turning aside a kindly suitor in order to preserve her faithfulness to the husband who saved her life.

Narrationally, the alternation between the separated characters gives us superior knowledge. We know, as the mother and brother do not, that the daughter survives; we also know that she nurses a bitter memory of hearing her mother choose the rescue of her brother. Likewise, we know that the mother has tormented herself for decades over her forced choice. Thus the recriminations that will burst out after they rediscover one another will require some healing, which is provided in the plot’s last phase. Melodrama depends on mistakes, and they must be corrected. In a telling image of two sets of schoolbooks (not previously shown to us), we and the daughter realize that over the years the mother has been thinking of her as if she were still alive.

The dual structure can also tease us with suspense. At the hour mark, we learn that both the brother and the daughter are in Hangzhou, without each other’s knowledge. The brother even encounters the foster father. It’s the sort of coincidence that leads us to expect a reunion. Coincidences, I mentioned in an earlier entry, are fascinating narrative devices, and here the fortuitous convergence doesn’t actually pay off. But it does prepare us for the genuine reunion that will take place an hour or so later, when an earthquake hits Sichuan in 2008.

There’s a lot more to be said about Aftershock; I was struck by the fact that the children are left in the collapsing apartment because the parents have sneaked off to have sex in the husband’s truck. (So is the whole arc of suffering the punishment for a little carnality?) But just sticking with structure, we find that a cluster of ancient plot devices, fed into the established technique of crosscutting, can still find purchase in a contemporary film. In films like Aftershock, as in Hollywood’s romantic comedies and horror films and historical adventures, very old narrative conventions live on. Suitably spruced up with CGI, they still provide pleasure.

Sometimes, however, you get the sense that filmmakers in other cultures are borrowing conventions of recent Western films. This seems the case in City of Life from the United Arab Emirates. Faisal is a spoiled playboy who spends his nights with his pal Khalfan, a fistfight-prone club-hopper. Natalia is a Romanian flight attendant who gets romantically involved with an advertising man. Basu is a taxidriver with an uncanny resemblance to a Bollywood star, and so he tries to supplement his earnings by appearing in a nightclub. As all of them move through Dubai, their lives intertwine.

We have, in short, what I’ve called a network narrative. Mostly the plot lines are juxtaposed through crosscutting, but sometimes the characters in one line of action encounter those in another. Faisal is at a club on the same night as Natalia is there, with her boyfriend and her roommate. Objects circulate as well. Natalia pays Basu for a cab ride, and Basu preserves her €20 note until he has hit rock bottom. At the midpoint, an ad campaign links Natalia’s boyfriend, Faisal’s father, and Basu’s job. Many of the conventions of the “small world” network format are included, with one character remarking that Dubai is a small city. Our old friend the traffic accident (shot and cut with exceptional vividness) plays a crucial role. A refuse collector threads through the plot, turning up at unexpected times and providing an ironic coda.

Director Ali F. Mostafa mobilizes a lot of contemporary techniques, including fast motion and rapid cutting (3.6 seconds average shot length). The editing sometimes extends the crosscutting principle by flipping back and forth between two successive scenes, creating little flashforwards. For instance, when the adman Guy phones Natalia to introduce himself, we cut to them talking in a bar and then back to her listening to his sweet talk.

The anticipatory cuts lead us to expect that Guy is calling to ask her out, and Natalia will accept. This sort of cross-stitching can be found in The Godfather and other films of the late 1960s and early 1970s, and it has shown up sporadically since, but it’s rare enough to still look modern.

In cinema, network narratives can occasionally be found before the 1990s, but they’ve become far more common. I count nearly 150 films of the last twenty years employing the structure. In literature, of course, such plots go back quite far, and they formed the basis of nineteenth-century novels by the likes of Balzac, Dickens, Zola, and George Eliot. Television soap operas and ensemble series like Hill Street Blues showed that modern media’s long-form formats fit well with network storytelling. So cinema has caught up, adjusting the template to feature-length plots. City of Life shows that artists from emerging filmmaking nations can use this structure to enter a festival circuit dominated by Western norms of construction. At the same time, those artists can tailor this structure to their own ends—in this case, it seems to me, presenting Dubai as a city of emigrants ruled by a feckless leisure class.

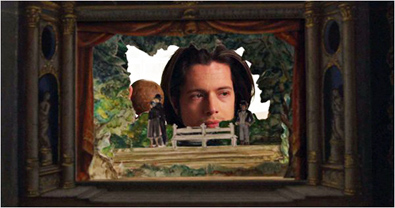

The theatre of memory

What happens, though, when conventions of sprawling nineteenth-century novels aren’t squeezed so drastically into the usual feature length? I had a chance to find out from Vancouver’s screening of Raul Ruiz’s four-and-a-half-hour Mysteries of Lisbon. Based on an 1854 novel by Camilo Castelo Branco, a fictioneer as prolific as Ruiz himself, the film doesn’t trim off the exfoliating plot lines that we enjoy in three-deckers from the period. This being a Ruiz film, there is as well a tangible pleasure in the artifice of storytelling. The film acknowledges that all the handy coincidences, buried pasts, multiple identities, and revelations of kinship are there for our delectation.

Orphans again: João is being raised in a church school, but he has no idea of his parentage. Early on, kindly Father Dimis tells him that his mother is Angela, the countess of Santa Barbara, but her brutal husband is not his father. We are soon embarked on the extended flashback that traces the doomed love affair that results in the birth of the young hero, now named Pedro. In the course of that tale, we meet two more suspicious characters, the gypsy Salino Cabra and the hired assassin Heliodoros.

This recounted history is only the first of a cascade of flashbacks, issuing from several characters, and these gradually show deep connections among persons tied to Pedro’s past. Secondary characters in one story become protagonists of another. The young hero is gradually displaced as the center of the action by war, secret romances, rivalries, duels, and infidelities. Like Pasolini in his Trilogy of Life, Ruiz is happiest when opening up a plot detour that will eventually become a new main road.

By the end, our young hero has become something of a nullity, an empty center around which aristocratic ecstasies and follies have swirled. He’s something like the Dubai of City of Hope: a point of intersection of many fates. He’s also a passive observer of scale-model dramas played out on his toy theatre stage. His voice-over narration has enwrapped the whole film, and our last glimpse of him is as merely a narrator. Pedro seems finally to realize that his entire existence has served simply to gather other people in a tangle of doomed passions.

Mysteries of Lisbon has a rich, high-thread-count look, but it’s not your usual prestige costume drama. The long takes cling to characters as they flirt their way across a ballroom, and the camera slips through walls in the manner of old-fashioned cinema. There are the usual Ruiz flourishes of hallucinatory deep focus (achieved through split-focus diopters), characters floating rather than walking, and the occasional peculiar angle. But the film remains calm and lustrous, culminating in a slow tread into pure light.

Mysteries of Lisbon has a rich, high-thread-count look, but it’s not your usual prestige costume drama. The long takes cling to characters as they flirt their way across a ballroom, and the camera slips through walls in the manner of old-fashioned cinema. There are the usual Ruiz flourishes of hallucinatory deep focus (achieved through split-focus diopters), characters floating rather than walking, and the occasional peculiar angle. But the film remains calm and lustrous, culminating in a slow tread into pure light.

Ruiz’s appetite for narrative is almost gluttonous; he supposedly wrote over a hundred plays in six years, and he’s made about as many films. He once told me that he thought that Postmodernism was simply a revival of the Baroque in modern dress. From Mysteries of Lisbon, it’s clear that he sees in many older narrative traditions affinities with our tastes today. Network narratives? They’ve been done, and maybe better, centuries ago. Follow the lacy tendrils of classic family-origins plots, and you’ll find a pattern as intricate as anything in Short Cuts or Pulp Fiction. More story ahead: there’s a six-hour television version.

Rumination on ruination

Ruiz understands that modernist narrative techniques, including unreliable narrators and fancy time-switches, depend upon a long tradition in at least two ways. First, very often the tradition got there first; scholars like Meir Sternberg and Robert Alter have demonstrated complex plays with chronology and point of view in the Bible and the Greek classics. Secondly, unusual plot structures may ring unexpected variations on more conventional ones. Case in point: reversed plot sequence.

Again, this seems to be something of a modern trend. The locus classicus appears to be Harold Pinter’s 1978 play Betrayal, in which, scene by scene, the plot proceeds in reverse chronology. This was filmed in 1983 and gave birth to a famous Seinfeld episode. As you know, Memento, Irreversible, and other recent films have taken up reverse-chronology plotting. Actually, however, there are several earlier instances, notably the 1934 Kaufman and Hart play Merrily We Roll Along (turned into a musical by Stephen Sondheim) and W. R. Burnett’s 1934 novel, Goodbye to the Past. Other examples, some going back quite far, are listed here.

Rumination, a film by Xu Ruotao in the Dragons & Tigers young directors competition at Vancouver, turns the structure to political ends. Reduced to the bare bones, the film shows a teacher, his wife, and their son caught up in the Chinese Cultural Revolution. The father falls in with a gang of Red Guard youths rampaging through the countryside. The son trails the gang at a distance and occasionally interferes with their acts of violence. These story events are arranged in blocks, with each cluster of scenes associated with a specific year. The blocks proceed backward in time, from 1976 to 1966. After a prologue, the film shows scenes of the waning of the Revolution; before the epilogue, we get a stalwart young man announcing the Revolution’s birth.

The scenes are fairly episodic and independent, so I didn’t detect the backwards structure for quite a while. But my uncertainty had another source. Xu introduces each year’s scenes with a date that is, except for one instance, not the year of the actions shown. In fact, while the segments move in reverse order, the years’ designations move in chronological order.

The opening 1976 section is labeled 1966, the 1975 section is labeled 1967, and so on up to the end, with the 1966 action designated as 1976. So we see the father’s reunion with his wife, a moment of clumsy embrace, long before he decides to leave home. As you’d expect, there’s one year in which the action and the tag coincide, 1971, and that is the only one built out of photos and film clips from the period. The year is privileged, Xu explains, because that was the year of the mysterious plane-crash death of Lin Biao, a military hero and Cultural Revolution leader who was accused of plotting Mao’s assassination.

In my viewing, the misleading dates helped conceal the reverse chronology. Confronted with so many discrete episodes of unidentified characters sprinting through the countryside, beating passersby and stealing chickens, I took the default option and assumed that the segments were chronological. Moreover, the film’s scenes play out almost entirely in overcast landscapes and decrepit factories, a landscape in which I couldn’t detect any indications of change from year to year. Watching Ruination a second time, I saw the reversal more clearly, but I also thought that some segments tease us into thinking along chronological lines. An early scene shows the father getting up in the morning (a conventional way to start a plot), saluting Chairman Mao’s statue, and reading from the Little Red Book. Yet this scene is set in 1975, after the father has returned to his wife from his Red Guard period.

Moreover, there’s some evidence that the son actually matures across the film, even though the scenes show him objectively getting younger. By the end of the plot (the earliest moment in story time) he seems to have transformed himself into a strapping young Red Guard. Supporting this construal is the fact that in the Q & A after the showing, Xu mentioned that one influence on his film’s design was The Curious Case of Benjamin Button!

Xu explained that the tragedy of the Cultural Revolution could not be comprehended through normal storytelling techniques. I suspect that viewers familiar with the relevant events and the film’s slogans, iconography, and oblique citations (even to Godard) could follow the backwards sequencing. But I suspect that those viewers would need a sense of the historical chronology to grasp the 3-2-1 order of the plot. It seems to me that Xu, known until now as a painter, has shown how an innovative approach to plot structure relies on conventional responses even as it thwarts them.

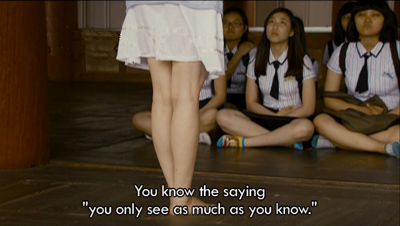

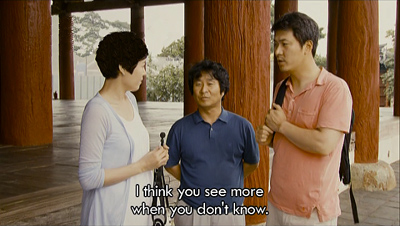

Hahaha indeed

Hong Sangsoo has been one of the leading experimenters with narrative in today’s Asian cinema. My two favorites, The Power of Kangwon Province (1998) and The Virgin Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors (2000) have engaged the viewer in playful puzzlement about how story lines can collide or slip sideways, how our memory of earlier scenes’ action can be tested and found faulty. I haven’t been deeply engaged by his recent forays into more straightforward drama/comedy, such as The Woman on the Beach (2006), but his two latest features, both from this year and both on display in Vancouver, completely satisfied my hunger for intriguing plot structures.

It’s an unspoken convention of recounted-flashback tales that even though the events are told by A, B learns everything that we do—everything, that is, that we can see or hear in the flashback. But Hahaha decouples the verbal recounting from the visual presentation. Here listener B definitely does not grasp what we witness happening onscreen in the tale as told.

Hahaha is a parallel-protagonist tale. Two pals meet for some drinking before one, Munkyung, leaves South Korea for Canada. Through a series of flashbacks, they regale each other with their recent adventures, mostly amorous. The plot is structured as two alternating streams, crosscutting one man’s tale with the other’s and usually returning to the framing situation of their drinking bout. But because we can see what each one recounts, we come to realize that both stories are populated by the same people, notably the tempting female tour guide Seongok. And those people have their own relationships, which we must piece together out of the glimpses we get in each man’s tale.

Neither Munkyung nor his pal Jungshik has a clue that they are part of a fairly tight circle. The result, as usual with Hong, is a comedy of ironic misunderstanding and the puncturing of male pretension. Hahaha can also be seen as his response to the rise of network narratives. Characters in such a film don’t usually realize the larger mosaic they’re part of; the intersecting lives in City of Life transform one another unwittingly. Normally that lack of awareness isn’t the main point of the film. Here it is, and it’s wrung for classic humor at the protagonists’ expense.

In Oki’s Movie, Hong gives us another fractured plot, but now in the form of four short films. They center on three characters: Song, a film director turned professor; his student Jingu; and Oki, the woman both men are interested in. The raggedy credits of each short suggest handmade movies, but what we see in each one is the polished style familiar from Hong himself, including his current interest in abrupt zooms.

The four-part structure is far from transparent. It might be taken as a series of episodes from the trio’s lives. The first film, “Specters of the New World,” which presents Jingu as a professor himself, would have to take place in the present, and the following three would then be presenting flashbacks to the Jingu-Oki-Song triangle. In that case, the first segment would prove that Jingu did not wind up with Oki, as he’s married to another woman.

Perhaps, though, all four films are free hypothetical variations on the central situation. I’m not sure that we can easily arrange the events in the second, third, and fourth episodes chronologically. The films could be presenting successive groups of events, or events scattered across a single time span and then selectively gathered around one of the central characters. The first episode is largely organized around Jingu’s range of knowledge; the second is confined to professor Song; and the third is explicitly presented as Oki’s own thoughts. Earlier Hong films have offered us contrasting, even incompatible plots built out of a core group of characters. Oki’s Movie may be using the framing conceit of student films (none of which is plausible as a student film) to give us a suite of variants on the love triangle.

The idea of ambiguous variation is made explicit in the final mini-film, “Oki’s Movie.” It’s a sustained exercise in—yes, again—crosscutting. This episode alternates two excursions to Mount Acha, one with each man. Shot by shot, we see different courtship styles and we hear her differing reactions to her two lovers. Was she dating both men at once? When did the two excursions take place? Which one occurred first? As these questions are juggled, we get a rapid checklist of Oki’s attitudes, in voice-over, toward both these minor-key losers.

In both Hahaha and Oki’s Movie, Hong takes what’s offered by tradition—in this case, the romantic comedy and the conventions of flashbacks, crosscutting, and restricted narration—and creates a fresh structure. The play of novelty and norm is engrossing in itself, apart from the vagaries of the drama. Our appetite for narrative will always be whetted when directors find ways to whip up something new out of familiar ingredients.

For more on the three dimensions of film narrative, as well as discussion of the principles of network construction, see my Poetics of Cinema. There’s more discussion of flashbacks in film in this entry. On early narrative structure, see Meir Sternberg’s Poetics of Biblical Narrative and Robert Alter’s Art of Biblical Narrative, as well as Sternberg’s discussion of The Odyssey in Expositional Modes and Temporal Ordering in Fiction. For a sharp-eyed consideration of Oki’s Movie, see Andrew Tracy’s review at Cinema Scope.

Oki’s Movie.

The Dragons & Tigers’ late-night roar

Thomas Mao.

DB here:

First, the news flash: Tonight was the awards ceremony for the Dragons & Tigers competition for young filmmakers here at Vancouver. A jury doesn’t get more distinguished: it consisted of (left to right) Jia Zhang-ke, Denis Côté, and Bong Joon-ho.

They awarded two special mentions, one to Phan Dang Di’s Don’t Be Afraid, Bi! (from Vietnam) and to Xu Ruotang’s Rumination (China). On the last-named, check the still at the end of this entry.

The grand prize went to the Japanese film Good Morning to the World!, by Hirohara Satoru.

More details here. Congratulations to the winners!

Beginners’ luck

My Film and My Story.

Vancouver is unusually hospitable to shorts and features by newcomers. Two of this year’s D & T offerings illustrate how talent, unlike youth, is not wasted on the young.

A cinémathèque featuring classic films is about to reopen, and the manager has hired some twentysomethings to help her get things into shape. The result a network narrative: romantic rivalries, coming-of-sexual-age crises, the race to set up the screening space, and even a ghost story are woven together as the big day approaches. The film is split into eight chapters, each given an emblematic movie title. Two petty thieves interview for a job under the aegis of “Stranger than Paradise,” and an apparent love triangle is christened “Jules and Jim.” The cinephilia shapes the plots too, as when one boy gets the courage to kiss another after watching Happy Together.

My Film and My Story was a group project of students at the Art and Design School of Konkuk University in Seoul. Their professor proposed that each student write a script about the opening of the cinematheque, and the results were integrated into a single feature-length story. There were seven student directors, one per episode; a producer contributed an extra chapter. Most directors were on the set all the time, making suggestions and trying to fit bits together. (“We fought a lot.”) The remarkable visual consistency—smooth cutting, tight framing, and well-modulated lighting—came from the single director of photography. As the title suggests, some of the tales are based on incidents in the lives of its makers.

The film, presented in Vancouver by two of the directors, Hong Youjin and Kim Taeho, is a lively charmer, with plenty of comedy and pathos. The characters are quickly introduced, and there are nice touches of movie-nut satire. One girl with big spectacles saves all her ticket stubs, takes notes on every movie (I can identify), and is annoyed when a boy drapes his leg over the seat in front of him. The episodes make tactful use of digital techniques, particularly in one shot that fuses past and present through the classic color/ black-and-white disparity.

My Film and My Story wasn’t in the official young-film competition, but Icarus Under the Sun was. For once the ragged style of handheld video justifies itself in a tale of a girl who quits school and heads for Tokyo to work in a seedy mahjong parlor. Haruo rooms with a flighty roommate and her boyfriend, but becomes more attached to the workers in the parlor and the owner, a nearly blind, taciturn man for whom she conceives an almost daughterly affection.

The plot barely rises above anecdote, but it’s continually engaging through its focus on the performance of Abe Saori, one of the two directors. Haruo explains that she is “addicted to walking,” and some of the best scenes involve conversations during late-night wanderings in the bitter cold.

Starting out fairly choppy, the narration accumulates weight and breadth as Haruo becomes engaged in her work. The shots throughout are held rather long, but about halfway through, the scenes start to be built out of exceptionally long takes. When another worker, the boy Aran, takes sick, Haruo calls on him and we get an almost suspenseful treatment of her arrival in his apartment, with him lying almost motionless in a heap in the foreground.

The shot lasts almost four minutes as she comes forward to talk with him. Their subsequent conversation is filmed in a tight, leisurely shot as they eat burgers and explain their backgrounds—virtually the only exposition we get about Haruo’s troubled past.

The dingy look of many scenes carries a documentary conviction that a more polished work would not. And the rough texture is actually the product of patient care. Abe and her codirector Takahashi Nazuki explained that they spent ten months in shooting and two to three months in editing. But it’s no mere technical exercise either, since Abe calls it both a fictional film and a documentary about her experiences. Like her protagonist she spurned conventional schooling and went to Tokyo to live on her own. Rooming with Takahashi, she decided to make the film “to know certain shadows” in her life. Icarus Under the Sun is actually the duo’s second film, and they have already finished a third, the more technically slick Soft-Boiled Egg (Hanjuku tamago.). Another thing about young directors: They have energy.

Expecting

Takashi Miike’s 13 Assassins is not what you might expect. Unlike your typical Miike item, this one throws no curves. It is an old-fashioned, butt-stomping, gut-slashing swordplay movie, with swagger to spare. Adapted from a 1963 film, it’s Seven Samurai plus six, with explosives.

True, there’s a Miike signature moment early on that shows what Lord Noritsugu has done to a woman’s body in his quest for piquant entertainment. But this horrifying scene serves a very traditional purpose: To prove to swordmaster Shinzaemon Shimada (and us) that Noritsugu has failed his duty as a leader and must be assassinated. He isn’t merely brutal. He lives an aesthetic of exquisite savagery. He has turned droit de seigneur into performance art. A massacre, he says with a fetching smile, is fun. He is a handsome monster. We can hardly wait to watch him die—preferably like a dog, in the mud, in agony.

Thereafter all that we want from a chambara flows forth in abundance. Unsurprisingly, the plot is framed by the man-out-of-time motif. Noritsugu’s depraved tastes show that the samurai tradition and the Shogunate government have become decadent. This might be a warrior’s last chance to die nobly—but for what? What deserves a man’s loyalty? Hard times have convinced Shinzaemon that the samurai class must ultimately serve the people. But his old rival Hanbei, Noritsugu’s right-hand man, clings to the notion that the samurai serves his master, unswervingly. Hanbei goes to his death committed to traditional duty. But his commitment is proved unworthy when his lord has a little fun with his severed head.

Miike faced a choice. He could have provided each warrior a vivid backstory, differentiating and humanizing each one as Kurosawa did. Instead, given a two-hour running time, he concentrates on strategy: How can a baker’s dozen of fighters defeat Noritsugu’s troops, which will eventually swell to 200? The solution is to maneuver Noritsugu’s men into a village filled with traps that will give the assassins some advantages—surprise, rooftop ambushes, and a deployment of livestock as ordnance. Things are enlivened by a feral hunter, mocking the samurai code while wielding a mean slingshot. After supplying a sketch of each of the thirteen assassins, Miike spends his energy on action. The muddy, gory battle at the climax lasts forty-plus minutes, and is worth every penny of your admission. Magnet, the genre arm of Magnolia, has picked up 13 Assassins for early 2011 release, and you should start thanking them already.

If Miike surprises by doing something normal, Zhu Wen’s Thomas Mao really does keep you guessing. It’s a pleasure to see a movie in which you can’t imagine what will come next.

At first, things seem to go by the numbers. To a remote Chinese farm comes the artist Thomas, to stay a short while and do some drawing. His wizened host Mao provides bed (after the geese are shooed out) and board (mostly corn on the cob). The trouble is that Thomas speaks no Chinese and Mao speaks no English. Every interchange is a pas de deux of misunderstanding. Thomas generously gives Mao some money. Mao refuses—not, as Thomas thinks, because he’s too proud but because Mao considers the amount insultingly small.

So we seem to have the small-scale cross-cultural comedy, making amusing points about people’s petty differences. Then the ghosts arrive.

At least, they might be ghosts. A phantom swordsman and swordswoman float around Mao’s farm and do battle, ultimately slashing off each other’s arms before disappearing, never to return.

There are aliens too, invading Mao’s cabin with pop-concert glow sticks. They’re totally unexpected, like the warriors, and their visit is even more transitory.

Eventually Thomas leaves, and the film starts over. The second part offers a sort of crazy-mirror image of what we’ve seen so far. Artist becomes model, model becomes artist, dog becomes Doggy. If you like the double-track story of Syndromes and a Century, you’ll probably like Thomas Mao, which is less rigorous but more funny. (The very title is part of the joke.) Zhu, who has reveled in comic byplay in Seafood and South of the Clouds, gives us that rare thing, a movie that is whimsical without being precious. You learn about contemporary Chinese painting in the bargain.

More whimsy, also not overbearing: When Liu Jiayin told me last spring that she was making a movie about a plastic fish, I didn’t know what to expect. The answer comes in the short film 607. Here the ballet of family hands seen in Liu’s Oxhide II becomes more playful. 607 is part of a promotional series of shorts by independent filmmakers, and it’s sponsored by a Beijing hotel, The Opposite House.

Mr. Fish, wielded by Liu’s father, swims around the tub, occasionally flirting with a mushroom provided by her mother. Eventually Mr. Fish is tempted by a hook (the curled finger of Liu herself). Will he fall for it? In all, you have to admire the coordination of three people shifting smoothly offscreen around the tub, each person’s hands sliding out of one part of the frame and popping in somewhere else—somewhere, I need hardly say, fairly unexpected.

PS 9 October: This entry has been corrected from its initial appearance. There I had written that Liu Jiayin’s 607 is one of three films she is making for the series commissioned by The Opposite House. Actually, the entire series consists of three films made by independent filmmakers. 607 is one of those and is complete in itself. Thanks to Shelly Kraicer for the correction.

Rumination.