Archive for the 'National cinemas: China' Category

Wantons and wontons

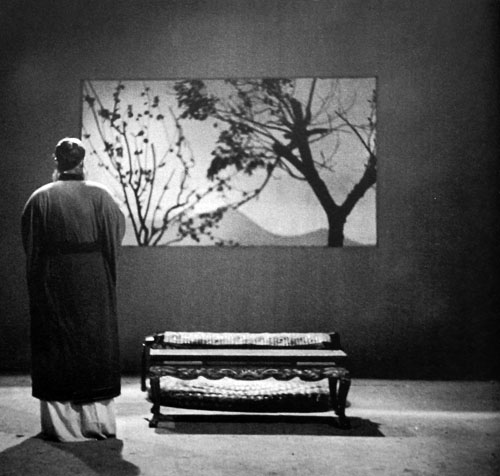

Oxhide II.

DB here, with more from the Vancouver film fest:

Two of the more innovative films I saw evoked film history—one explicitly, the other obliquely. Raya Martin’s Independencia is part of a planned series devoted to the history of the Philippines, told from the bottom up. In this first installment, villagers flee into the jungle to hide from the American “liberation” of their islands. The film centers on a mother and son who, joined by a woman the son finds, create a new family. After years, the son and the woman have a child, but their new life is threatened by the encroachment of the invaders.

What sets Independencia apart is Martin’s effort to create the look and feel of a 1930s fiction feature. He shot the movie wholly in a studio, and the evidently faked backdrops are counterbalanced by gorgeously controlled lighting effects, and even dashes of color. Since virtually no Filipino films survive from this period, Martin gives us less a pastiche than a possibility, a sort of hypothetical archival film. The fact that the film makes aggressive use of Dolby sound, especially during a tremendous storm sequence, only adds to the sense of history being reimagined for today.

More traditional, at first glance, is Puccini and the Girl, a historical drama by Paolo Benenuti and Paolo Baroni. Facts of the case: In 1909, a maid in Puccini’s Tuscan villa, accused of being his concubine, committed suicide. But an autopsy revealed that she was a virgin.

The film’s reconstruction of what happened behind the scenes, tracing the veins of jealousy and deceit running through the household, relies on recent research into the tragedy.

At the same time, we have an homage to silent cinema. In most scenes we hear no dialogue: actors whisper at a distance from us, or simply conduct themselves without speaking. What words we do hear are recited pro forma (the Mass) or sung (in a waterside tavern, or in nondiegetic accompaniment). There is only one line of conversation, and that is given greater saliency by being a cry from the heart.

So we’re largely confronted with a silent film, accompanied by music and sound effects. To add to the estranging effect, characters communicate chiefly through letters and telegrams—exactly as in the films of the period. We hear the letters’ text read aloud, but the sense of stately compositions propelled by written commentary, distinctive features of 1910s cinema, remains. An unwitting homage, perhaps, but one that pleased this fan of classic tableau cinema.

Independencia was part of the Dragons and Tigers thread, one of the hallmarks of the Vancouver event. Year after year it gives an unequaled view of current Asian cinema. This year’s program, assembled by Tony Rayns and Shelly Kraicer, was at least as fine as ever. Eight films compete for the $10,000 prize given to first or second features. The winning film, Eighteen by Jang Kun-jae, centered on the familiar situation of teenage lovers separated by parents and school pressures. I didn’t see all the competitors, but my own favorite was Chris Chong’s Karaoke, a Malaysian story of a young man coming to terms with his mother’s decision to sell her karaoke bar. The first ten minutes are quite creative, disorienting the audience through complicated sound mixing, while the boy’s community, devoted to the production of palm oil, is presented with a documentary directness.

Outside the competition, I saw several Asian films of consequence. I’ve already discussed Yang Heng’s Sun Spots and Bong Joon-ho’s Mother. Ho Yuhang’s At the End of Daybreak marks a shift from his lyrical first feature, Rain Dogs, which I reviewed at Vancouver in 2006. A plot situation close to that of Eighteen is treated in much darker tones. A young man falls in love with a high-school girl, but he’s driven to murder by her growing indifference to him. The familiar elements of furtive sex, drinking parties, and demands from the girl’s family for reparations are given a noirish treatent. Ho’s admiration for American crime novels shows in his increasingly bleak handling of the affair. Here the femme fatale is a high-school girl, and the entrapped male’s revenge is complicated by an unexpected erection.

Also under the influence of classic crime films was Yang Ik-June’s Breathless from Korea (right). It shows a brutal debt collector coming to terms with his childhood. Under a harsh surface realism, the film has the contours of the familiar redemption of a hard case, including the decision to reform that comes a tad too late. (Whenever a crook vows that this will be the last time he pulls a job, wait for the ironic retribution.) I thought that the character parallels (two scenes of murdered mothers) were somewhat too neat, but the director plays the anti-hero with conviction and deadpan humor, and Kim Kkobbi supplies an exhilarating turn as the tough high-school girl who becomes his companion.

Also under the influence of classic crime films was Yang Ik-June’s Breathless from Korea (right). It shows a brutal debt collector coming to terms with his childhood. Under a harsh surface realism, the film has the contours of the familiar redemption of a hard case, including the decision to reform that comes a tad too late. (Whenever a crook vows that this will be the last time he pulls a job, wait for the ironic retribution.) I thought that the character parallels (two scenes of murdered mothers) were somewhat too neat, but the director plays the anti-hero with conviction and deadpan humor, and Kim Kkobbi supplies an exhilarating turn as the tough high-school girl who becomes his companion.

Bong Joon-ho has been something of a leitmotif on this site lately, with my comments on Influenza and Mother. Under the rubric “Bong Joon-Ho & Co.,” Dragons and Tigers screened a collection of shorts paying tribute to the Korean Academy of Film Arts. Most were from the 2000s, but Kim Eui-suk’s Chang-soo Gets the Job, dated from 1984. Focusing on a gang of teenage purse snatchers, Kim’s film was a little rough technically, but it built its story deftly. The quality of the rest was quite strong, with the grisly and wacky Anatomy Class (2000, Zung So-yun) being a high point. Meanwhile, Bong’s Incoherence (1994) shows that his urge to deflate official hypocrisy, seen in Memories of Murder and The Host, was already present in his student days.

My admiration for Hirokazu Kore-eda runs high, as I indicated in my discussion of Still Walking at last year’s VIFF. But Air Doll, while full of vagrant pleasures, left me unsatisfied. The Kafkaesque premise, derived from a manga, is that an inflatable saucy-French-maid dolly comes to life, endowed with speech and movement but retaining her seams and air valve (both of which will figure in the plot). Her sad-sack owner doesn’t notice the transformation, but while he’s at work, she takes a job at a video store and wanders the city.

The aim, I think, is to defamiliarize ordinary city life by seeing it through Nazomi’s eyes. The fact that a sex effigy is the most innocent character in the movie is part of the point. Makeup, money, and fashion start to seem extensions of sad, solitary eroticism, and the line between mainstream movies and porn gets blurred. But all the thematic elements didn’t blend very well, and at moments, as during the music montages showing people’s desperate loneliness, I worried that for once Kore-eda had slipped into conventional sentimentality. The tone also shifts, with a climax that revises the big scene of In the Realm of the Senses. Kore-eda deserves credit for his unflagging effort to try something fresh with every project, but here, it seemed to me, that the film was defeated by an overcute conceit and underdeveloped execution.

The most exciting Asian film I saw at VIFF was Liu Jiayin’s Oxhide II. Her first feature, Oxhide, was screened at Vancouver in 2005. (Full disclosure: I was on the jury that awarded that film the D & T prize.) This one seemed to me even better.

To say that this 132-minute film is about a family making dumplings is accurate but misleading. To add that the action consumes only nine shots makes it sound like an arid exercise. In fact, it’s a consistently warm, engaging—I don’t hesitate to say entertaining—film that is also a demonstration of how a simple form, patiently pursued, can yield unpredictable rewards.

In the first Oxhide, we saw the comedy and tensions of Liu’s life with her parents, who run a leatherwork shop. By the time she shot part two, they had already lost their business, but the sequel presupposes that the shop is still going, albeit coming to a critical point. So there’s a quasi-documentary aspect, as the family’s financial strains, discussed cryptically at various points, hover over the mundane process of wonton cookery. Yet although everything looks spontaneous, it was all completely staged—written out in detail, rehearsed over months, reworked in test footage, and eventually played out in “real time.”

And in real space. The first shot, which consumes twenty minutes, shows Liu’s father pummeling a hide in his vise and eventually clearing the table for serious food preparation.

Actually, the film’s subject is that table. On its surface, a meal is prepared; around it, the family gathers; we even see what happens underneath. We watch father and mother chop scallions, mince pork, twist and yank dough, pinch the dumpling wrappers around the filling. We watch the daughter try to match her parents’ dexterity. This is a movie about housework as handiwork, and family routines and frictions.

For minutes on end, we see only hands and arms; Liu’s 2.35 frame often chops off faces. Liu employed a construction-paper mask to create the CinemaScope format within HD video. Why the wide frame? Most filmmakers use it for expansive spectacle, she remarks; but “I wanted to see less.” And the horizontal stretch further emphasizes the table.

As if this weren’t rigorous enough, Liu has filmed the table from a strictly patterned arc of camera positions, dividing the space into 45-degree segments. These unfold in a clockwise sequence around the table. What could seem an arbitrary structural gimmick is justified by the fact that each setup proves ideally suited to each stage of the process. When father and mother team up to start the meal, the angle gives us two centers of interest. And Liu feels free to “spoil” her mathematical structure by varying the height and angle of her camera. Plates, bowls, and an articulated lamp become massive outcroppings in this micro-landscape.

Oxhide II is unpretentiously inventive, quietly virtuosic. Evidently it took a Chinese filmmaker (whose day job is writing TV dramas) to blend domestic life with the rigor of Structural Film. Liu displays the fine-grained resources yielded by several cinema techniques, from framing and staging to lighting and sound. The finished dumplings get constantly rearranged on the cutting board. Each family member has a different technique for pulling off bits of dough, and each gesture yields its own distinctive snap.

I had to think, almost with pity, of all those US indie filmmakers who believe they have to cultivate CGI and slacker acting, to seduce investors and strain for outrageous sex and edgy violence. Liu made this no-budget, low-key masterpiece over years in a single room, and with her parents. That’s a new definition of cool.

Liu promises us another installment. In the meantime, every festival that’s serious about the art of cinema should pledge to show Oxhide II.

Puccini and the Girl.

PS 12 October: Thanks to Matthew Flanagan for correcting an embarrassing typo.

PS 15 October: Thanks to Ben Slater for correcting yet another one!

Revenge of the ROW

Sun Spots.

DB here:

Watching Congress on C-SPAN makes you realize that the dead outnumber the living. Likewise, going to a film festival like Vancouver’s drives home to you how many movies there are out there. The world produces about 5000 features per year. No more than fifteen per cent of those come from the United States. That leaves about 4300 from what Hollywood execs apparently, and disparagingly, call ROW—the Rest Of the World. And hundreds of those 4300 are fighting for spots at the film festivals that have sprung up around the globe. Hence the rise of the programmer, today’s art-film gatekeeper and tastemaker.

To be a programmer you must be knowledgeable, traveled, and well-networked. You have to be steeped in contemporary film, you have to make your way to obscure places, and you have to know the right people—filmmakers, producers, sales agents, critics you can trust. Hence the power of a festival like Vancouver’s. It has superb programmers like Tony Rayns, Shelly Kraicer, Mark Peranson, Terry McEvoy, Stephanie Damgaard, Tom Charity, Sandy Gow, Tammy Bannister, and their colleagues.

You could mount a perfectly respectable event by cherry-picking other festivals’ lineups, but Vancouver mixes current international hits with genuine discoveries. Vancouver’s recognized specialties, like new Asian film, documentary, and Canadian features, nicely counterbalance their obligation to bring to the community the latest in top-drawer films of all sorts. A user-friendly festival in an exceptionally welcoming and picturesque city, Vancouver remains a magnet for us and hundreds of other cinephiles. This is my fifth visit, and Kristin and I commented online in 2006 (start here), 2007 (start here), and 2008 (start here).

This year’s Vancouver doesn’t lack big-name attractions. Keeping up their dedication to Manoel de Oliveira (a ripe 100-plus years old), the programmers have brought us Eccentricities of a Blond Hair Girl, a sixty-minute package of pure pleasure. At first it seems a redo of Obscure Object of Desire. A man on a train recounts his frustrated efforts to marry a gorgeous young woman he glimpses at a window. But it turns out that this is an adaptation of a short story by Eça de Quieró, and things develop in very different directions than in Buñuel’s film. Oliveira’s characteristically chaste framings and sumptuous décor are enlivened by some errant formal devices that it would be a shame to divulge.

Okay, I’ll mention one because it kicks in from the start. On the train, Ricardo decides to tell his story to the woman sitting next to him. But while listening she usually looks straight into the camera. And every time she replies to his remarks, instead of turning to look at him, she delivers her lines directly to us. Ricardo looks at her, or sometimes just glances around as speakers do, but during her lines, the camera acts as a relay between her and him. You never quite get used to this strange displacement of dialogue, and it helps make Ricardo’s tale of archaic courtly love as subtly unnerving as the revelation that seals the couples’ fate. Whippersnapper directors a third Oliveira’s age would not dare so much.

Another much-awaited title was Bong Joon-ho’s Mother, and the hopes I expressed in the previous entry weren’t disappointed. A mentally handicapped boy is accused of murder, and his mother leaps into action to find the killer. As in Bong’s earlier Memories of Murder, a mystery intrigue ramifies into the lives of disparate characters, so that we’re skittering between physical clues (a golf club, inscribed golf balls, a strangely positioned corpse) and psychological ones, with bits of behavior serving to suggest multiple motives. Each character continues to surprise us—in particular, the sneering wastrel who takes advantage of the son. Driving the plot and passing through a spectrum of emotional changes, of course, is the title character. There’s no shortage of movies called Mother (though we’re told this one should properly be translated as Mother/Murder), but veteran actress Kim Hye-ja as the indefatigable guardian of her boy is as memorable as Pudovkin’s and Naruse’s protagonists.

Bong’s compact compositions are always at the service of his storytelling. I couldn’t see any fat on the scenes. His fluent pacing squeezes suspense and surprise out of each plot convolution. While the mother talks to her boy in jail, the lawyer stands at a distance from them, and, slightly out of focus, checks his watch. Instantly we know that he’s uninterested in the case. But Bong also knows how to linger. One of the most memorable slow dissolves I’ve seen in recent years counterposes mother and son, sleeping alongside each other off-center, against a horrific discovery tucked against the other edge of the anamorphic frame.

Mother has plot to spare; it could loan some to Sun Spots. What hath Hou wrought? I thought during the first few minutes of this exercise in Asian minimalism. This relentlessly dedramatized tale of a fugitive triad who meets a sulky girl in the countryside is determined to deny us any significant action, intense emotion, or old-fashioned enjoyment. Long shots, some very distant; thirty-one single-take scenes; impassive actors smoking, staring, turning from the camera, and generally hanging out: We have been here before. After twenty years of masterpieces by Hou, Kore-eda (Maboroshi), and Jia Zhangke (Platform), this style risks mannerism.

Eventually, though, I shifted gears and came to respect the movie. First, the landscapes are ravishing, worthy of a James Benning film. (8 ½ x 11, in which narrative gestures are swallowed up in immense spaces, wouldn’t be an irrelevant comparison.) Second, many compositions develop in unpredictable ways, and you’re given enough time to scan the frame for clues to what has happened before we join the scene. You’re obliged to notice handbags, cellphones, fishing poles, and cigarette butts strewn across the visual field. Third, director Yang Heng has exploited one powerful advantage of HD video: razor-sharp depth of field. This allows him to integrate distant hills and streams into the action. You see everything sharp and fresh, even actions hundreds of yards away. The final nine-minute shot forms a kind of climax of spatial acuity. A couple, trailed by a solitary figure, drift away from us into a grove of trees, and they remain visible as patches of white and black for an achingly long time before finally disappearing. Here “vanishing point” takes on its full meaning. Unthinkable on DVD, Sun Spots lives fully on the big screen, and one has to respect Yang’s single-minded commitment to making an anecdotal plot into something austere and sensuous.

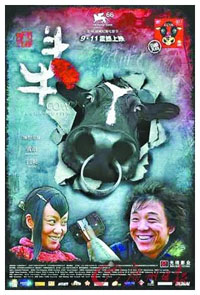

Sun Spots was a world premiere, and it illustrates just how committed Vancouver is to continuous discovery. Also in the revelations category is Guan Hu’s Cow, which takes us into the territory so successfully covered by Jiang Wen’s Devils on the Doorstep. (2000). The Chinese countryside is under siege from the Japanese, and survival is the name of the game. A village comes into possession of a huge European heifer and revels in her apparently boundless supply of milk. But the Japanese army has other ideas, and it’s up to the fumbling but plucky farmer Niu Er to protect the cow while evading the enemy. Cow is currently filling Chinese theatres, and the poster suggests a light-hearted adventure, but actually the comedy comes in a rather violent context. If told chronologically, the plot would turn steadily dark, so Guan adroitly uses flashbacks to keep offsetting horror with humor. Once more, popular cinema shows itself able to handle emotional extremes with a steady hand.

Sun Spots was a world premiere, and it illustrates just how committed Vancouver is to continuous discovery. Also in the revelations category is Guan Hu’s Cow, which takes us into the territory so successfully covered by Jiang Wen’s Devils on the Doorstep. (2000). The Chinese countryside is under siege from the Japanese, and survival is the name of the game. A village comes into possession of a huge European heifer and revels in her apparently boundless supply of milk. But the Japanese army has other ideas, and it’s up to the fumbling but plucky farmer Niu Er to protect the cow while evading the enemy. Cow is currently filling Chinese theatres, and the poster suggests a light-hearted adventure, but actually the comedy comes in a rather violent context. If told chronologically, the plot would turn steadily dark, so Guan adroitly uses flashbacks to keep offsetting horror with humor. Once more, popular cinema shows itself able to handle emotional extremes with a steady hand.

Kristin and I have already seen plenty of other films we want to commend to you, but hitting four screenings a day hasn’t left us a lot of time to blog. Still, we’re determined to bring you more comments on this wondrous festival’s offerings.

Cow.

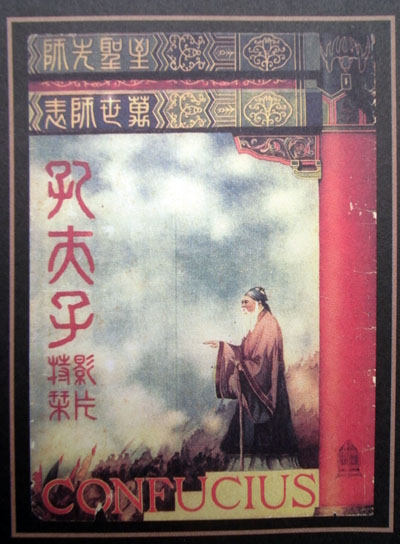

Confucius reborn

DB, in Hong Kong:

Fei Mu is a little-known name in the West, but on the evidence of even a few films, it’s clear that this mainland Chinese filmmaker was one of the finest working anywhere during the 1930s and 1940s. His best-known film, Spring in a Small Town (1948), was considered in the Maoist era an overliterary piece of sympathy for the bourgeoisie. Now things have changed. Many specialists today consider Spring in a Small Town the best Chinese film of all time. It’s an extraordinary work, anticipating Antonioni in its slow unfolding of an erotic situation, treated with a mixture of sympathy and austerity. It’s a great pity that the film isn’t available on good and subtitled DVD copies, though a digitally restored print was made in 2005.

Fei Mu is a little-known name in the West, but on the evidence of even a few films, it’s clear that this mainland Chinese filmmaker was one of the finest working anywhere during the 1930s and 1940s. His best-known film, Spring in a Small Town (1948), was considered in the Maoist era an overliterary piece of sympathy for the bourgeoisie. Now things have changed. Many specialists today consider Spring in a Small Town the best Chinese film of all time. It’s an extraordinary work, anticipating Antonioni in its slow unfolding of an erotic situation, treated with a mixture of sympathy and austerity. It’s a great pity that the film isn’t available on good and subtitled DVD copies, though a digitally restored print was made in 2005.

Two other Fei Mu films I’ve seen show the variety and flexibility of his craft. Onstage, Backstage (1936) is a drama of theatre life, and its fluid figure movement in depth recalls Renoir. Very different is the expressionistic allegory Nightmares in Spring Chamber (1937), an episode in the portmanteau film called Lianhua Symphony. Fei presents the Japanese invasion of China as the pursuit of an innocent girl through dark sets by a leering, frock-coated Japanese. Other surviving Fei works, such as Blood on Wolf Mountain (1936), are also held in high regard. After Mao’s revolution, Fei Mu moved to Hong Kong, where he died at the age of 45. He directed no films in the Crown Colony.

All this makes the discovery of a print of Confucius (1940) an event of capital importance. An anonymous individual donated a print to the Hong Kong Film Archive, which spent years restoring it in collaboration with L’Immagine Ritrovata of Bologna. In the donated print of Confucius, some portions of the soundtrack had liquefied, so some stretches are silent, and there are about nine minutes of fragments that have yet to be integrated.

At the premiere, a very useful booklet on the film’s restoration was given out, and moving introductory speeches were presented by Barbara Fei Ming-yee, the director’s daughter, and Serena Jin, daughter of the producer Jin Xinmin. The screening added electronic subtitles that not only translated the dialogue but identified each speaker—a helpful gesture for a film with many characters and a tangled intrigue.

I can’t comment on it as a representation of Confucius’ thought and life, although experts tell us that it is quite different from the elevated, almost sanctified portrayals that were known before. The plot dramatizes the ineffectuality of the sage’s ideals of civic virtue by showing how power players of his era ignored or undercut his teachings. Scenes from Confucius’ life alternate with scenes of political and military strategy, as warlords and statesmen debate tactics and, not incidentally, calculate how to eliminate Confucius. As Confucius migrates across China, he is unable to halt the continuous warfare among various factions. His disciples leave or die. Just before his death he has only his grandson to care for him. “A great educator, thinker, and philosopher,” Fei Mu writes in an essay, “Confucius was doomed a victim of the politics of his time.”

The film is slow-moving and hieratic. Some of the fragments show bits of violence, but the film as a whole relies on dialogue. Although some scenes unfold in natural exteriors, Fei Mu often employs theatrical tableaus, complete with painted landscapes; occasionally the actors cast shadows on the backdrops. The cutting is often axial, simply enlarging a chunk of space as actors declaim their dialogue. The nearly square Movietone frame enhances the symmetry of the compositions, which often feature a window or some other aperture.

Knowing the fluid style of Fei’s 1930s films, we can only regard this rigid, rather ceremonial look as a deliberate artistic choice. In this respect, the film recalls Eisenstein’s Alexander Nevsky and Mizoguchi’s Genroku Chushingura, films of that era aiming to treat a weighty historical subject with solemnity. In Confucius, Fei seems to have been rethinking the relation of cinema to theatre, a quest that preoccupied other directors of the period and that remains important today. Wong Ain-ling’s essay in the booklet aptly notes Rohmer’s Perceval le Gallois as a more recent parallel, and the film likewise has some of the feel of the Straub/ Huillet version of Von heute auf morgen (1997). As often happens, Fei Mu feels like a modern filmmaker.

Confucius was shown across China in 1940 and 1941, and a reedited version was released in 1948. Fei Mu was so upset by the new cut that he took out a newspaper ad denouncing it. Wong Ain-ling, who prepared the documentation for the festival presentation, and Sam Ho, the Archive Programmer, have concluded that this print is likely to have been the re-release version. Sam told me that the archive staff would be spending the next year researching how to integrate the fragments and supply a sense of the original’s design. The Archive is planning to screen that restoration at next year’s festival. Whatever the experts come up with, surely this is a discovery that will be discussed and enjoyed for many years.

Jackhammers, parties, and markets

DB here:

No matter how often you see this Ur-touristic view, it’s still spellbinding. Yes, I’m back at the Fragrant Harbor for the annual festival, front-loaded with Filmart, the film market. My 2008 report starts here, and the 2007 one starts here. Plenty of entries for those years; I’m not sure I’ll be able to roll out so many this time, but we’ll see.

Start with the first impressions. Massive building projects and new traffic-flow strategies have made the tip of the Kowloon peninsula even more pedestrian-unfriendly than last year. Grim underground passages take you in loops away from your destination. No more direct routes anywhere, it seems, and construction projects I’ve watched for years continue to be unfinished. From the twenty-first story of my hotel I can hear a jackhammer at street level.

A striking case: My hotel is rather close to a multiplex in West Kowloon, located in an upscale mall called Elements. (More on Elements in a later communiqué.) But around this trendy spot stretches a vast vacant lot.

Again, there’s a lot of pedestrian control, including barriers to keep you from crossing the street. Still, it’s not hard to find places where enterprising passersby, perhaps armed with blades, have broken on through to the other side.

Moreover, the Star Ferry to Wanchai still offers a pleasantly sustained ride and the usual spectacular views, even in the rain and mist that have enveloped my first days here.

Wanchai is the location of Filmart, set up in the Convention Centre, the mammoth swooping building seen at the top and bottom of this entry. As usual, Filmart was stuffed with seminars, screenings, and dealmaking, as well as the Asian Film Awards.

The opening of Filmart included a party, where you could find Chris Doyle, accompanied by a beer, rubbing shoulders with Stefan Borsos, editor of the German magazine CineAsia.

The party got stranger. This year’s festival logo is a dude in black tie with a black starburst head and a hollow look around the eyes. I thought he was only a graphic design until Karen Mok brought him onstage.

He seems a saucy fellow, at least judging from his hand gesture here.

Filmart opened with a screening of Derek Yee‘s new film Shinjuku Incident. Before the show, Yee, on left, lined up with his cast. You can recognize at least one of the ensemble, grinning as usual.

In the following days, I saw several good movies: More on them in the next post in a day or so. I also attended some sessions devoted to technology and marketing. The effects company Digital Magic sponsored a demonstration of various digital formats, of which the Red system seemed to me the best. Digital Magic also gave out cute Viewmaster-like toys promoting their work.

I learned things from this session and the one sponsored by Salon Films, but the main live event I hit was the Hong Kong Film New Action Forum, a day-long series of sessions about the future of Chinese film. The first item was a brief discussion moderated by director Gordon Chan (Beast Cop, Painted Skin; left). Two experts discussed the current status of CEPA, the Closer Economic Partnership Arrangement that allows Hong Kong productions to count as mainland ones for purposes of financing and distribution. Across the last few years, half or more of the top-grossing pictures, such as the Zhang Yimou costume epics and Peter Chan’s Warlords, have been CEPA-enabled coproductions. Other countries, such as Singapore, Japan, and Korea, are investing in such projects.

I learned things from this session and the one sponsored by Salon Films, but the main live event I hit was the Hong Kong Film New Action Forum, a day-long series of sessions about the future of Chinese film. The first item was a brief discussion moderated by director Gordon Chan (Beast Cop, Painted Skin; left). Two experts discussed the current status of CEPA, the Closer Economic Partnership Arrangement that allows Hong Kong productions to count as mainland ones for purposes of financing and distribution. Across the last few years, half or more of the top-grossing pictures, such as the Zhang Yimou costume epics and Peter Chan’s Warlords, have been CEPA-enabled coproductions. Other countries, such as Singapore, Japan, and Korea, are investing in such projects.

The other session I attended was more high-profile. Philip Chan, screenwriter and former cop, moderated a discussion among John Woo, Oliver Stone, Andrew Lau Wai-keung, and Feng Xiaogang. The Chinese directors talked about the market. Stone talked about creativity. This division of labor reminded me of what Bernard Shaw supposedly told a Hollywood producer: “The problem is that you are only interested in art, and I am only interested in money.”

Woo took the floor with a long discussion of making Red Cliff. He made the usual point about wanting to wed Chinese stories to Hollywood production values. Some other items:

Woo took the floor with a long discussion of making Red Cliff. He made the usual point about wanting to wed Chinese stories to Hollywood production values. Some other items:

*He built the project to have marketing appeal, designed both for Asian and western consumption. For instance, strong women appeal to female viewers in all countries. He claimed that one reason that Red Cliff broke attendance records in Japan was the support of women audiences.

*Woo also wanted to bring audiences in Hong Kong and China back to local films, away from Hollywood imports. Viewers, he claims, are bored with Hollywood’s formulas and want something fresh and authentic. But local audiences are getting tired of Chinese blockbusters too, so in Red Cliff Woo introduced humor along with Hollywood-level production values.

*He suggested that before making Red Cliff he had considered retiring. Now he’s planning more projects.

Lau and Feng likewise took up practical considerations. Lau said that filmmakers must go where the market leads. He suggested there was a period when Hong Kong filmmakers went to Hollywood, but now that route is risky. At the moment, the market is the Mainland, not the West. He was not rueful about his own experience in Hollywood (with The Flock), but he treated it as a chance to learn “a different set of rules. Every place has its own rules.” He also spoke of the unexpected success of Infernal Affairs, a “back-to-the-wall” effort that seemed risky in the market decline of the 2000s. No one expected the film to be so successful; the actors cut their asking prices to be in it.

Feng Xiaogang, Mainland director of Cell Phone and A World without Thieves, lived up to his reputation for stirring things up. Announcing that Hong Kong people “consider the Mainland a four-letter word,” he rattled off an account of the current PRC market. Feng indicated that a $20 million film can presently break even in the domestic market. This prospect interested me, because such benefits are rare in the history of movies. As film students know, the US used its big domestic market as a base to launch vast overseas distribution.

Box-office income is growing fast, but there aren’t enough screens. He claimed that there were about 4000 in the country, an absurdly small number for such a populous country. (Probably this figure counts only modern screens, not old or temporary ones.) The key, Feng suggested, was capitalizing the building of still more screens, especially in the 350 “small” cities. The government will subsidize theatre construction to some extent.

If 1000 more screens are added, Feng speculated that in five years the annual box-office receipts could hit 30 billion RMB. That’s about $4.5 billion, somewhat less than half of the 2007 US box-office take—but twice as much as the income in Japan for the same year. China is developing into a prepossessing market.

Finally, Oliver Stone confessed his love of Asian films, singling out their “iconic imagery” (Crouching Tiger, even Woo’s Face/Off) and lyricism (Ozu, Wong Kar-wai). His advice: Don’t withdraw from engagement with the West and “Make films that pop their eyeballs out.”

Finally, Oliver Stone confessed his love of Asian films, singling out their “iconic imagery” (Crouching Tiger, even Woo’s Face/Off) and lyricism (Ozu, Wong Kar-wai). His advice: Don’t withdraw from engagement with the West and “Make films that pop their eyeballs out.”

One theme I took away was the way in which regionalism continues to rule the Asian industries, a topic I raised in Planet Hong Kong and in late chapters of Film History: An Introduction. Who needs Western markets if the PRC market continues to swell and if other territories in the area hold up their end of financing, distribution, and the occasional regional hit? As far as mass-market cinema is concerned, we may be moving toward a bipolar world, with North America at one pole and Asia at the other. For an excellent, fact-filled analysis of the implications of this trend toward regionalism, see Darrell William Davis and Emilie Yueh-yu Yeh’s brand-new study, East Asian Screen Industries.

Soon, very soon, we go to the movies.

Screen Digest offers some slightly older statistics on the Mainland market here. For more recent information on Chinese exhibition in a worldwide context, see “Exhibition Breaks Revenue Record,” Screen Digest (September 2008), 274. The number of screens cited here is far greater, perhaps because it counts all the rural, unmodernized, or temporary venues. Karen Chu of the Hollywood Reporter sums up the New Action Forum event here.

Hong Kong Convention Centre.