Archive for the 'National cinemas: China' Category

Three from Palm Springs

Four Nights with Anna.

DB here:

Three high points from the Palm Springs International Film Festival. Soon Kristin will offer some entries.

Four Nights with Anna is a GOFAM—a Good Old-Fashioned Art Movie. Set in a muddy Polish town, it follows a loner as he stalks a zaftig nurse. Leon watches her from around corners, studies her through her apartment window, and eventually sneaks sleeping powder into her sugar jar. This puts her out soundly enough to allow him to break into her apartment and watch her at close quarters.

My synopsis, like most retellings of this spare movie, not only spoils the experience but fundamentally changes it. Instead of laying out the premises explicitly, the film’s narration supplies them in tantalizing, equivocal doses. Skolimowski follows the great tradition of distributed exposition, so that we get context only after seeing something that can cut many ways. Early we see Leon buying an axe; soon he fishes a severed hand out of a sack and tosses it into a furnace. Is he a serial killer? No. After a while we learn that he’s the disposal officer for the hospital crematorium. Retrospectively fitting together these data provides a classic art-film pleasure, the equivalent of the curiosity-arousing clue sequences in a mainstream mystery.

The same goes for the ambiguous inserts that suggest a police interrogation. Only halfway through the film do these snippets become lengthy and explicit enough for us to place them in the story’s time sequence. Just as the Nouveau Roman of Robbe-Grillet owed a great deal to the classic detective story, the European art cinema tradition has drawn heavily on the investigation plot, from Les mauvais rencontres (1955) to The Spider’s Stratagem (1970). The premises of the thriller surface as well. The central conceit of Four Nights and of Kim Ki-duk’s 3-Iron, of a stranger who quietly and obsessively prowls around homes, was also explored in Patricia Highsmith’s 1962 novel Cry of the Owl, but not with Skolimowski’s playful indeterminacy about who and what and why.

The trick, then, is in the telling. By accreting details that cohere gradually, Skolimowski’s film not only engages curiosity and suspense, but also allows room for wayward, if dark humor. Leon’s quaking abasement leads to embarrassment, pratfalls, and comically strenuous efforts to melt into his surroundings. Objects take on a precise life, as Leon crushes his grandmother’s sleeping pills to powder and uses plastic silverware to fish a fallen ring from cracks in the floor. We never see Anna apart from Leon; she’s either in the same locale or glimpsed in precisely composed shots of her at her window. The exact, constrained handling of optical point-of-view owes a lot to Rear Window, but Jimmy Stewart never went so far as to install a new window to enhance his peeping.

In its diffuse exposition, its teasing inserts, and its gradually unfolding implications, a GOFAM also asks us to appreciate unresolved uncertainties. During the Q & A, Skolimowski remarked that he liked “to play with a little ambiguity . . . to leave it for the audience to interpret.” The locale? Indefinite, he says. The time period? Deliberately left vague. The mysterious final shot? “A third ambiguity.” For the man who made the kinetic Identification Marks: None (1964), Walkover (1965), Barrier (1966), and Le Départ (1967), film is something of a sporting proposition. It’s good to see him back in the game.

By contrast, The Shaft by Zhang Chi is a NFAAM, a Newfangled Asian Art Movie. That means minimalism. Single-shot scenes are captured by a distant, stable camera. Characters mutely go about their business, or just stand there. Pivotal plot moments take place outside the frame or between two static scenes. Any dramatic climaxes and grand passions are muffled or simply sufffocated.

The proximate sources of this Asian minimalism are probably the late 1980s films of Hou Hsiao-hsien. A European predecessor of the style, I think, is Fassbinder’s Katzelmacher (1969), but its most famous early instance would be Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman (1975).

Such a quiet style poses a problem: How to show plot changes and character development without lengthy dialogue? A common solution is to repeat setups in ways that diagram changes in character relationships. Have a young man pedal his bike up to his girlfriend and offer her a ride. Later as their relationship cools, show him in a similar framing riding callously past her.

Or show the couple wordlessly visiting a lake, but after they break up, show the girl standing there alone.

Tableaus can be used to parallel couples. Each pair meet near the village railroad trestle, but the compositions distinguish the couples.

Likewise, the shots showing the central family eating in front of the TV can be recalled through variation. The number of people at the table and their identities can change over the course of time.

The Shaft puts such conventions to solid use. In a rural Chinese town, young people face the choice of going to work in the mine or moving to Beijing. The film is built out of three stories, centering on a daughter, then her brother, and finally their father. At the end, the eventual revelation of what happened to the family’s mother throws the preceding love stories into sharper relief.

Once the innovators have mastered a style through dint of effort, others can glide down the learning curve and pick it up quickly. But then they should try to add something new. Today the rudiments of the minimalist style are comparatively easy to acquire. To go beyond those, you need something else—a more elaborate play with pictorial variations, or more ingenious staging (the Hou solution), or a gift for adjusting to the contours of landscape (the Jia Zhang-ke alternative). The Shaft is well-carpentered. It is measured and poignant (especially in its final story), and it concludes with a stunning trio of shots. Its very modesty, though, suggests the conventions of NFAAM need some renewal, even some shaking up.

Shaking things up is what Kurosawa Kiyoshi’s Tokyo Sonata is all about. A salaryman is downsized, but he can’t bear to tell his family. He pretends to go off to work while he actually tries to find a new job, any job. In the meantime, his sons display more ambition and courage in their limited worlds, than he does, while the mother tries to defuse the emerging tensions.

For an hour or so, this story is engrossing on naturalistic terms, alternating comedy and pathos. It might continue in a vein of gentle realism characteristic of that perennial Japanese genre, the shomin-geki, ending with everyone’s stoic reconciliation to the vagaries of life. But the director of Cure and Charisma will go along with this formula only up to a point. Why not break the form? You can argue that the simple purity of The Shaft plays too cautiously; once you’ve figured out how things will probably unfold, who cares to see the rest? A smooth cup is lovely, but a cracked one possesses its own enigmatic appeal.

So Kurosawa careens his homely tale into grotesque territory. The tone and plot logic that he’s cultivated so carefully are fractured by some violent emotions, implausible coincidences, and unexpected twists. Granted, his technique remains unruffled.Kurosawa follows Japanese traditions of enclosing faces in apertures and arranging people in gridwork patterns that still leave room for natural movement. The beginning of the story’s wild detour is discreetly signaled by a variant of the film’s first shot. But the composure of the handling makes the challenge to our expectations all the more disruptive.

I shouldn’t say much more, except to note that I meant the word fracture to suggest that the film mends its bones eventually. The final moments are taken up with a delicate performance of Debussy’s Clair de lune. Neither GOFAM nor NFAAM, risk-taking and in the end quite moving, Tokyo Sonata attests to the unpredictable innovativeness of Japanese filmmaking.

I may add other thoughts to Kristin’s upcoming dispatch, but for now I just note that Palm Springs is the only festival I know that uses Béla Tarr soundtrack cuts for pre-show music.

Tokyo Sonata.

Goodbye to Hong Kong for another year

My Heart Is That Eternal Rose.

DB here, yet again:

Back nearly a week from Hong Kong, I’ve been swamped by backlog and made logy by jetlag. But I wanted to offer last-minute notes from this year’s film festival. I won’t comment on the films that disappointed me or that weren’t in finished form. Instead, upbeat reports, some pictures, and a trio of DVD delights.

On the big screen

Little Cop (1989) starring and directed by Eric Tsang, was part of the festival’s tribute to him. It’s a silly but ingratiating item that anticipates Stephen Chiau’s mo lei tau nonsense comedy. The opening credits are burned onto Tsang’s pudgy body, and thereafter a series of episodes takes him to the anti-prostitution squad (cue the condom jokes) and then the drugs detail. There are engaging gags around a funeral, with a song in praise of death set to the Colonel Bogey march, and lots of intrigue with a master criminal who can steal other people’s faces. Needless to say, since this is Hong Kong, we get many food gags too. Eric called in his bets and got a flurry of walk-ons from top stars like Andy Lau and Maggie Cheung. The only tedious stretch is the last scene, an uninspired clone of Steve Martin’s Absent-Minded Waiter routine. Otherwise, good dirty fun.

Paranoid Park (2007) seemed to me Gus van Sant’s best film in a long time, after the somewhat arid exercises of Gerry and Last Days. Here he’s got a genuine, gripping story that he can render in his detached but lyrical style. The shot of Alex in the shower is particularly gorgeous, and the tracking shot of his tormented walk through town is enhanced by swarms of subvocal recriminations that spurt out from all three channels. My friend J. J. Murphy has provided further commentary on his blog here and here.

If movies about moviemaking risk narcissism, movies about film school must be narcissism squared. The Early Years: Erik Nietzsche Part 1 (2007) centers on a young filmmaker who is transparently Lars von Trier. In-jokes about Danish film culture pile up, and the plot takes almost every easy way out, but Jakob Thuesen keeps the proceedings moving briskly enough. The caricatures are fun, although I think the all-night frenzy of film school life is better captured in Yanagimachi Mitsuo’s Who’s Camus Anyway?

A real revelation: And the Spring Comes (2007, above), by Gu Changwei. A somewhat homely woman with a crystalline singing voice imagines herself headed straight for the Beijing opera. Instead, broken love affairs and unwillingness to lower her ambitions keep her sequestered teaching music in a small town. A tough but touching melodrama rendered in a tactful style, with female lead Jiang Wenlei willing to be unsympathetic.

Many art movies can seem inert in their storytelling—over-under-dramatized, we might say. Carlos Reygados’s Silent Light (2007) escapes this trap. Slow and static, it is suffused with a stark calm that gives gravity to a love affair between a stolid farmer and a woman who runs a café. Planimetric compositions are used imaginatively, and the soundtrack makes daring use of offscreen noises. As an old Dreyer fan, however, I have to worry about the film’s relation to Ordet. Dreyer’s film isn’t exactly ripped off or cited, but it floats behind this one like a spectre before materializing at the climax, perhaps in overbearing fashion. Ordet, suffused with religious debate, earns its miraculous finale, while Silent Light, for all its austerity, is a film of the flesh, and its spiritual coda seems to me somewhat forced. But I’m willing to be convinced otherwise.

Because another guest didn’t appear, I was asked to introduce programs of films by or related to Maya Deren. I enjoyed the chance to see them again, and to reread her writings in the excellent collection Essential Deren. Her work remains stimulating—especially Meshes of the Afternoon and Ritual in Transfigured Time. Her writings blend a stringent formalism, echoing Rudolf Arnheim‘s views of cinematic specificity, and a fascination with myth and non-Western cultures. The boys’ Trance movies (Fragment of Seeking, The Cage, The Potted Psalm) are of historical interest, but hers remain lively. I was happy to see how many young people stayed after the screenings to discuss films that are sixty years old.

On the small screen

In my shopping, I discovered three fine movies on DVD.

*Do Over, a Taiwanese network narrative I liked in Vancouver back in 2006, now available with English subtitles in a so-so transfer (good color and contrast, blurry frame-by-frame pickup). A strong debut film from Cheng Yu-chieh.

*My Heart Is That Eternal Rose, an important 1989 Hong Kong film by New-Wave talent Patrick Tam. This mix of romance and crime stars Kenny Bee, Joey Wang, and a shockingly young Tony Leung Chiu-wai, and Christopher Doyle is listed as one of two cinematographers. The film’s daring stylization marks it as belonging to Hong Kong’s late-80s burst of creativity, and many moments look forward to the luxuriant melancholy of Wong Kar-wai. Clearly Tam (who edited Days of Being Wild and Ashes of Time) was an important influence on Wong. For a long time, I had access to My Heart only on an ugly pan-and-scan laserdisc, but now a widescreen transfer of a worn but bright print offers a considerable improvement. It’s far from perfect, with somewhat slurred movement, but better than nothing.

*Play while You Play, usually known as Cheerful Wind (1981), is Hou Hsiao-hsien’s second film, a romantic drama about a blind man and a somewhat self-indulgent television producer. It’s one of his three commercial “musicals,” and seldom seen, let alone discussed. I think that stylistically these films lay the groundwork for his Taiwanese New Wave films from The Sandwich Man onward. (Go here for more.)

I don’t enjoy this quite as much as his first film, Cute Girl, or his third, The Green, Green Grass of Home, which seems to me nearly a masterpiece. Still, there are lovely moments in Cheerful Wind, including the music montages and a surprisingly offhand ending. Hou films almost casually in the open air, letting passersby drift in and out of the frame (above). The disc, from something called Hoker Records, claims on its package to be 4:3, but it actually preserves the 2.35 format. Unfortunately, it does so through letterboxing, yielding only so-so resolution. No English subtitles. Rumor has it that the irresistable Cute Girl is available in a similar package.

In the point-and-shoot LCD

Four of the brains behind the festival: Ivy Ho, Bede Chang, Li Cheuk-to, and Albert Lee.

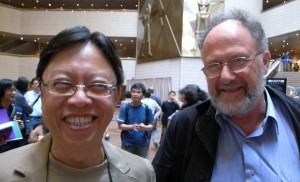

Shan Ding, man of all work at Milkyway Image, and the magisterial Peter Greenaway.

Mrs. Johnnie To, Johnnie To, Amy Lau, and Lau Ching-wan, who normally eats nicely.

Joanna Lee, translator extraordinaire and music facilitator to the world.

Jupiter Wong, ace photographer, and Bela Tarr after the enthusiastic reception of The Man from London. My takes on Tarr are here and here and here.

Peter Chan, whose Warlords just won a slew of prizes at the Hong Kong Film Awards.

Jacob Wong, Festival programmer, and Raymond Phathanavirangoon, lately of Fortissimo. I praised Raymond’s presskits last year.

Shu Kei and Michael Campi, just before the premiere of Coffee or Tea, which Shu Kei directed with Kwan Man-hin.

Tourist snap no. 1: Wherever you turn in Wanchai, there’s something interesting to see. Even air conditioners start to look like public sculpture.

Tourist snaps 2 and 3: I often took the Wanchai ferry to screenings on Kowloon.

Tourist snap 4: Coming back late from a screening on the Kowloon side, I would walk past the old clock tower.

. . . A walk fortified by a late-night sample of the Sweet Dynasty’s almond and walnut soup.

In all, as I said at the start of my 3 1/2 weeks here: This will always be the place.

News from the fragrant harbor

DB here:

For those of you who have had problems connecting with this site: Sorry! Our server was down for a couple of days. Ironically, I was one of the last to climb on. Hence the slight delay in this posting from the Hong Kong International Film Festival.

Whither Hong Kong film?

The Warlords.

Local cinema is still in the doldrums. As in most countries, Hollywood rules the box office. Production has dropped to about 50 releases last year, and the quality of what I’ve seen over the last week isn’t on the whole strong.

I’m told by a film professional who follows things closely that critics feel that 12-15 local films from 2007 are worth seeing and about 5 are actually good. Those five are Ann Hui’s The Postmodern Life of My Aunt, Derek Yee’s Protégé, Johnnie To’s Mad Detective, Yau Na-hoi’s Eye in the Sky, and Peter Chan’s The Warlords. It’s significant, my friend indicates, that almost never before has the same clutch of films been nominated for best picture, best screenplay, and best director at the Hong Kong Film Awards. (The awards will be given on 13 April.) “The falling industry has reached a plateau,” she remarks.

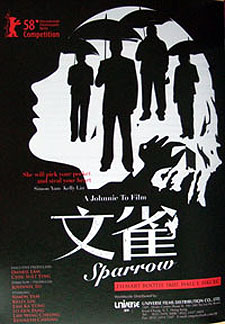

My sense is that Hong Kong cinema is sustained, however minimally, on three levels. As usual, there are the program pictures, chiefly urban action films and romantic comedies and dramas. These come and go, using local singers and TV stars, and allow theatres to keep their doors open. More creative are the films from local auteurs, principally Johnnie To Kei-fung. (Should I count Wong Kar-wai as a local filmmaker any more?) To’s Milkyway company turns out several worthy items per year, most directed by To. As I indicate in an earlier post, The Sparrow is their upcoming release; it’s also the best Hong Kong movie I’ve seen so far on my trip.

A third category includes the increasingly important China coproductions, nearly always military costume dramas. The emblematic shot: Mighty warriors on mighty steeds galloping toward the camera in a telephoto framing. Add spears, swords, shields, and slow-motion to taste.

The Warlords is the prime instance from last year, but it was preceded by The Myth (2005) and A Battle of Wits (2006). The genre was made popular by Mainland movies like Zhang Yimou’s overdecorated epics, and it has already furnished us two spring releases, An Empress and the Warriors (yes, you read that right) and The Three Kingdoms: Resurrection of the Dragon. Both are straightforward tales of military struggle, centering on loyalty and honor, with relatively little of the palace intrigue that usually furnishes plot motivation.

An Empress, starring Donnie Yen, Leon Lai, and Kelly Chen, is pretty thin going, with overhasty fight scenes and Bumpicam coverage. The only engaging element, apart from the porcupine armor on display in the ads, is the fact that Leon plays a warrior who has retired from the world. He has for obscure reasons turned his patch of the forest into a launching pad for a hot-air balloon. Still, when ninja-like invaders assault his rickety scaffolding, we get a fairly effective action scene that carries a little of the impact of director Ching Siu-tung’s best movies.

An Empress, starring Donnie Yen, Leon Lai, and Kelly Chen, is pretty thin going, with overhasty fight scenes and Bumpicam coverage. The only engaging element, apart from the porcupine armor on display in the ads, is the fact that Leon plays a warrior who has retired from the world. He has for obscure reasons turned his patch of the forest into a launching pad for a hot-air balloon. Still, when ninja-like invaders assault his rickety scaffolding, we get a fairly effective action scene that carries a little of the impact of director Ching Siu-tung’s best movies.

The Three Kingdoms, a Korean-China coproduction directed by Hong Kong’s Daniel Lee, is a somewhat more impressive item. The plot traces the rise of a general (Andy Lau), aided by his mentor (Sammo Hung), and their confrontation with a rival general, whose cause is taken over by his daughter (Maggie Q). There is little characterization; everything hinges on honor, retribution, and service to one’s superior. A tranquil interlude with Andy’s love interest, a shadow puppeteer, is quickly forgotten in the rush to combat. The musical score channels Morricone, and as in Empress, it employs thunderous drumbeats, chanting male choruses, and a keening soprano. Inevitably, we also sense the influence of Wong Kar-wai in the meditative voice-over and the fight scenes (choreographed by Sammo) that recall Ashes of Time in their slurring and spasmodic rhythms.

Are such films really desired by Asian audiences, let alone Western ones? The jury is still out. Thanks to shooting in China and the diffusion of CGI technology, such genre pieces can be made for much less than Hollywood would spend. Three Kingdoms came in at less than US$20 million, which is twice the budget purportedly spent on Empress. But international sales of the genre are spotty, and audience uptake isn’t overwhelming. Somebody will have to tweak the formula creatively. Will it be John Woo, with Red Cliff? Odds are against it, but I’d like to be surprised.

Incorrigibly optimistic, I’m still looking forward to Ann Hui’s newest film, The Way We Are, premiering tonight, and Coffee or Tea, the collaboration of veteran director Shu Kei and his student Mandrew Kwan Man-hin. That’s the closing film of the festival.

Films briefly noted

Kabei–Our Mother.

Other festival highlights for me:

Please Vote for Me! A primary school in Wuhan is introduced to democracy when the teacher decides that the monitor will be elected by the class. There ensues a struggle all too reminiscent of U.S. political campaigns. We have sound bites, applause lines, political operatives (here, overzealous parents), scurrilous charges, personal attacks, and outright bribery. The collision of human nature and democratic ideals make this a charming and thoughtful movie. I can’t imagine anyone not enjoying it, if only for its reminder of how humiliation feels when you’re nine years old.

Observando al cielo. Jeanne Liotta’s ode to astronomical phenomena, at once scientific demonstration and lyrical tribute to the swiveling of the heavens. Visit her website here.

Observando al cielo. Jeanne Liotta’s ode to astronomical phenomena, at once scientific demonstration and lyrical tribute to the swiveling of the heavens. Visit her website here.

Mauerpark. From the Austrian collective Stadtmusik, Tati-goes-Betacam. A long shot of a snow-covered park is at first puzzling, then amusing, then engrossing.

Alexandra. I nearly always like Sokurov. Yes, the films can be a little overbearing, but they have a certain weirdness that keeps them from pretentiousness. Here he gives us another story of family love. An old lady visits her grandson, who’s soldiering in the Caucasus. She rides in a tank, watches men clean their weapons, and putters doggedly about the bivouac. No big emotional climaxes, unless you count her encounters with other old ladies, who have set up a market selling shoes and cigarettes, and the moment when her soldier tenderly braids her hair.

Alexandra. I nearly always like Sokurov. Yes, the films can be a little overbearing, but they have a certain weirdness that keeps them from pretentiousness. Here he gives us another story of family love. An old lady visits her grandson, who’s soldiering in the Caucasus. She rides in a tank, watches men clean their weapons, and putters doggedly about the bivouac. No big emotional climaxes, unless you count her encounters with other old ladies, who have set up a market selling shoes and cigarettes, and the moment when her soldier tenderly braids her hair.

The weirdness comes in the color values–sometimes blinding orange, sometimes bilious green reminiscent of Sovcolor—and in a murmuring soundtrack that blends machine whirs and conversation with barely discernible swoops of orchestral and vocal music. (Since Galina Vishnevskaya plays the old lady, are these fragments from her performances?) Nobody makes soundtracks quite like Sokurov; even an unadorned shot can take on urgency through the drifting whispers our ears struggle to make out.

Jim Hoberman has a discerning review here.

Elegy of Life. Rostropovich. Vishnevskaya. Also a pleasure to listen to, but much more straightforward. A documentary tribute to the great cellist/ conductor and the singer. Since I’m interested in Russian music and cultural politics, this was an unadorned pleasure. To hear Rostropovich compare Prokofiev the classicist with Shostakovich the Mahlerian was especially worthwhile.

Kabei—Our Mother. Yamada Yoji received a lifetime tribute at the Asian Film Awards. Having directed over seventy movies, including the long-running Tora-san series, he’s usually discussed in terms of sheer productivity. But his calm, grave period films Twilight Samurai (2002), Hidden Blade (2004), and Love and Honor (2006) have reminded people that he’s a fine director too. A man of restraint, he never shoots handheld, he seldom moves the camera, and he uses close-ups as high points, not default values. His sobriety makes the 1.85 ratio look as cleanly fitted to the human body as the 1.33 one is. “The last classical director,” Mike Walsh called Yamada after the screening, and it’s hard to disagree.

Kabei was for me the high point of the festival so far. It’s 1940, and a Tokyo intellectual is arrested for “thought crimes.” As he endures prison, his wife and two daughters struggle to make ends meet, with the help of Yamazaki, a loyal student. An epilogue reminds us of the now-elderly mother’s devotion to her husband.

That’s about it, but the poise of the performances and the simplicity of the presentation make this like a film from the era it portrays. I wish I had a DVD to illustrate the craftsmanship that Yamada brings to the very first shot, which unhurriedly introduces the family while the mother simply hangs out wash on the line. I wish I could show you how the moment that a badminton birdie lands on a rooftop pivots from comedy to sadness. I wish I could replicate the composition that hides a weeping Yamazaki from us—a shot that actually makes the audience burst into laughter. Who else would have the film’s biggest star, Tadanobu Asano, keep his back to us for an entire scene?

But maybe it’s better I don’t give such things away. Best to say: Despite all the other movies you see, Kabei shows one way that cinema can still be.

Finally, as antidote to my somewhat depressing diagnosis of the state of HK film, two items. First, the reception for Sylvia Chang‘s Run, Papa, Run showed off her lively charm. Here Sylvia, in black, is flanked by her stars, Yuhan Liu, Rene Liu, Lewis Koo, and Nora Miao, who played in Bruce Lee pictures.

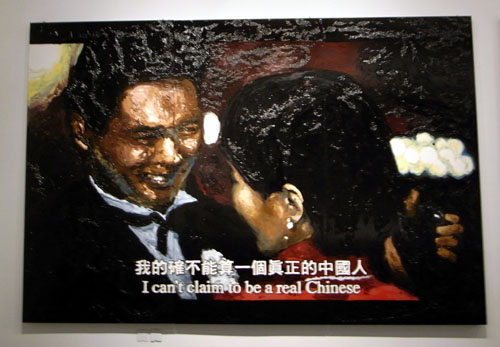

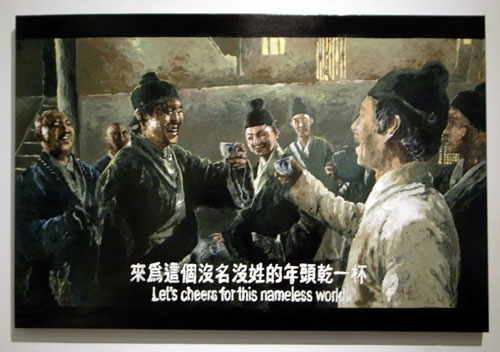

Second, in the entertaining exhibit Made in Hong Kong at the art museum, you will find the work of Chow Chun-fai, whose output includes large, glossy enamel images taken from movies, complete with letterboxing and subtitles (typically about Chinese/ Hong Kong identity). The blocky figures seem both chunkily monumental and somewhat decaying. One of Chow’s huge pictures, derived from Love in a Fallen City, surmounts this blog entry. Below is another, based on King Hu’s Dragon Inn.

More to come in a few days, including, I hope, thoughts on Maya Deren and an interview about sound design in Milkyway movies.

PS later on 27 March: I’ve just discovered a remarkable array of comments on Alexandra in this Criterion thread. John Cope‘s discussion is particularly admirable.

THE place

“For us, Hong Kong will always be the place.”

Chuck Norris, The Octagon (1980)

DB here:

Hong Kong’s Entertainment Expo, including the Hong Kong International Film Festival, the Asian Film Finance Forum, and the Hong Kong Filmart, runs for nearly a month, and it has drawn me back to the fragrant harbor. For refreshers, you can visit last year’s posts here.

Biz

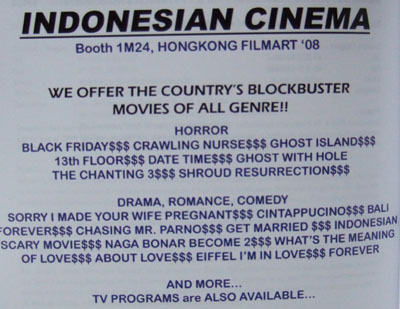

The Filmart has become Asia’s biggest spring media event, with hundreds of companies crowding into a pavilion of the Convention Centre. Here people traffic in movies and TV shows, buying and selling distribution rights, seeking funds for production and partners in movie ventures. I wandered through it last year, and you can track this year’s activities at Variety’s site here.

The last figures I saw indicate that the world pumps out about 4800 features each year. Coming to a market like Filmart, you get to peek below the waterline and see the iceberg that’s underneath.

There are, for instance, the bulk genre items from secondary, or tertiary, producing countries.

There are the films that seem somewhat derivative.

Then there’s the vehicle with the midrange star that just might make it to late-night cable.

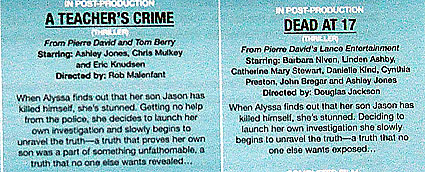

Finally, there are the films that acknowledge themselves to be identical. These descriptions come from Imagination Worldwide’s catalogue ad.

By contrast Filmart mounted a respectful display devoted to Edward Yang, who died last summer. Edward made idiosyncratic, powerful films that would, even today, be very hard to sell at a market. He was a skilled cartoonist, and the display includes some of his perky storyboards and a self-portrait.

The Asian Film Awards, which I covered last year, started things off with a midsize bang Monday night.

The full results can be found here. I was pleased that Secret Sunshine, quite a good film, won three top awards (film, director, actress). Milkyway, a favorite company of mine, garnered a couple of prizes, and The Sun Also Rises, one of my favorites from last year, did pick up the Production Design prize.

Some Big Stars were visible at both the show and the after-party. Heartthrob Tadanabu Asano arrives.

Lee Kang-sheng and Tsai Ming-liang mingle before the awards.

Marco Muller, Director of the Venice Film Festival, at the after-party.

I got to talk briefly with one of my heroes, Hou Hsiao-hsien.

And of course Tony Leung Chiu-wai, emblem of the Entertainment Expo and winner of the Best Actor Award (Lust, Caution), was everywhere, and always looking good.

Within 36 or so hours, I saw quite a lot of movies. With friends Paisley Livingston and Mette Hjort and their kids I caught Enchanted, which pleased me with its schmaltzy cleverness. As part of the Festival, I re-watched on 35mm two movies I’d seen and commented upon last year: Jiang Wen’s The Sun Also Rises and the Tsui/ Lam/ To Triangle. These were shown at the shock-and-awe auditorium of a new cinema in a spanking new mall, Elements. The seats vibrate at the lowest frequencies, creating what is marketed as “4-D.”

At Filmart I saw the Luc Besson production Taken, another satisfying dose of formulaic filmmaking. Altogether different was Manuel de Oliveira’s Christopher Columbus, The Enigma. The title suits this apparently slight film about a historian’s earnest pursuit of Portugal’s influence on North American history. Haunting images of 1940s Manhattan swathed in fog, along with touching scenes of Mr. and Mrs. Oliveira visiting historic sites, linger.

Two films struck me as excellent. Gao Qunshun’s Old Fish (2008) centers on a simple idea. Somebody is planting bombs throughout Harbin, and an aging police officer is the only person remotely qualified to dismantle them. Over a leisurely half hour, we’re introduced to Old Fish, his wife, and his colleagues. Then the first bomb is found, and the suspense kicks in. The apparently clumsy codger, who in an early scene fumbles a World War II grenade, summons up wiliness and delicacy when he has to defuse the mysterious packages.

Two films struck me as excellent. Gao Qunshun’s Old Fish (2008) centers on a simple idea. Somebody is planting bombs throughout Harbin, and an aging police officer is the only person remotely qualified to dismantle them. Over a leisurely half hour, we’re introduced to Old Fish, his wife, and his colleagues. Then the first bomb is found, and the suspense kicks in. The apparently clumsy codger, who in an early scene fumbles a World War II grenade, summons up wiliness and delicacy when he has to defuse the mysterious packages.

I don’t think I’ve ever seen more tension-filled sequences of this sort. The film made me realize that in any bomb-disposal scene, when close-ups of a sweating face and a knifeblade hovering over a wire are followed by an extreme long-shot of the scene—that’s when we expect an explosion. Conventionally, the long shot announces the bang. But here, Gao gives us the long shot, and we have to wait, and wait some more. When the explosion does come, it is genuinely surprising.

Shot by shot and sound by sound, this is a very well-crafted, humane film. If anybody tells you that “foreign films” are digressive and boring, show them Old Fish.

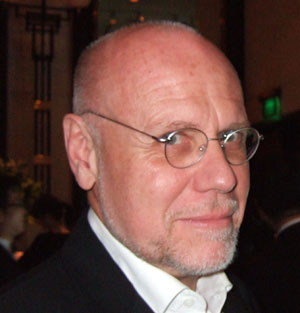

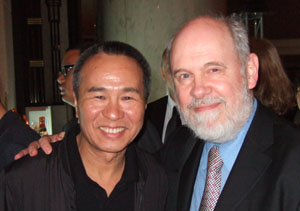

Just as fine, but more unclassifiable, was Johnnie To Kei-fung’s The Sparrow (2008), premiered at Berlin. A gang of pickpockets led by Simon Yam is beguiled by a mysterious lady on the run (Kelly Lin), and their schemes start to fall apart. As often with To, the conception of the film is slim, but the execution is rich. There are the games and competitions, the symmetries and repetitions, the offhand motifs (here, cigarettes, cigars, and pipes), the geometrical and arithmetical plot mechanics. Johnnie To has become perhaps the world’s most unpretentiously, unapologetically formalist director.

It’s a procession of twists and set-pieces. There are the funny one-off shots, like the two grifters with symmetrically broken legs and the gang flashing the razor blades they hide in their mouths. Some sequences are unpredictable miniatures, like the scenes that show how many camera angles you can find in an elevator car, even with a fishtank squeezed in. There’s also a delirious bit with a lipstick-stained cigarette.

Other set-pieces unfold more majestically. There’s a sweeping crane shot of the gang vacuuming up wallets of passersby, and an elaborate theft of a pendant during massage therapy. The climax is an exuberant pocket-picking competition with all contestants stalking through a downpour, their umbrellas forcing them to work with only one hand.

The Sparrow is at once a loving tribute to old Hong Kong island (Simon’s hobby is black-and-white photography), an unpredictable genre piece, and an exercise in light-fingered filmmaking. Like Old Fish, it offers lessons to Hollywood directors, if they have the wit to learn them.

Bits

At Filmart, Fred Ambroisine multitasks, taking cellphone calls and shooting docu footage at the same time.

Deng said “To get rich is glorious,” and now Mao agrees.

And in the spanking new, gargantuan mall known simply as Elements, an entire room is devoted to one essential Element.

More to come, soon I hope, from The Place.