Archive for the 'National cinemas: Denmark' Category

Bon Cinéma! (miaou optional)

The Sorceror and the White Snake.

DB here:

For days, debates about the new Sight and Sound Poll have been saturating the Net ecosystem. The reach of the Web allowed editor Nick James to launch what may be a month-long striptease. (Well played, sir.) And likely you, reader, were weighing lists of masterworks.

But not me. I was watching Japanese space warriors blasting phosphorescent aliens to bits. I saw an amiable cannibal provide gory inspiration for a creatively blocked painter. I saw Dutch layabouts in mullets who made sponging off the system a death sport while calling each other “homo” and kut. I saw an ode to women’s armpit hair, moments of man-on-mule lust, and sexy female snake-demons writhing their way through two movies.

No candidates for the 2022 S & S poll here, but all in all, pretty diverting.

No hecklers, please

Montréal’s annual FanTasia is a three-week tribute to the world’s genre cinema. You get horror, SF, fantasy, martial arts, crime, and tasteless comedy. These movies are bloody, horrifying, outrageous, and hilarious. Nothing says entertainment quite like a wholesome family, complete with babe in arms, being plowed down by a delivery truck.

The name packs in a lot. I think it was first called FantAsia, as befit its early emphasis on Far Eastern imports, but the newer version shifts a little more emphasis to “fan,” which captures the tenor of the audience. Old folks worry that that the young avoid subtitled cinema. They should visit FanTasia, where teens and twentysomethings are happily watching movies from Iceland, Vietnam, Japan, Denmark, Hong Kong, South Korea, Thailand, and Holland. The brains behind this festival know what the kids want.

Don’t confuse this with Camp or Hecklevision. The multititudes come not to mock but admire. I suppose that’s partly because for decades smart genre pictures have woven moments of self-mockery into their texture, so as to mesh with that knowing, ironic attitude that characterizes our consumption of much popular culture. A closed loop: Genre connoisseurs make these movies, and other connoisseurs applaud them. Once you learn that Inglourious Basterds, Shaun of the Dead, Perfect Blue, Killer Joe, and Visitor Q have had premieres of one sort or another here, you get it: This is head-banging, but strictly quality head-banging.

The proof came with DJ XL5 Italian Zappin’ Party. This two-hour mélange of b-movie trailers and clips is a FanTasia tradition, having been preceded by Mexican and Bollywood editions. This year’s brew mixed snippets from fairly famous movies with glimpses of little-known items like Zorro contra Maciste, Spasmo, and The Three Fantastic Supermen. But the result isn’t exactly Camp, and it doesn’t attempt to mimic the media spew we see in Joe Dante’s Movie Orgy. Instead, typical trailers and scenes are tidily arranged in genres–peplum, spaghetti Westerns, giallo, and so on–and left to run at considerable length. Often the clips point up a recurring gesture or bit of iconography (decapitation, musclemen manhandling boulders). It’s less like zapping, more like an otaku assembling clips on a disc or in a file and inviting us over for an evening. Cheesy as many of these items are, we’re invited to appreciate the unpredictable energy of cinema that strives to shock.

The FanTasia tribe has its customs. At each screening, as the lights go down, you hear meowing, sometimes answered by barks or growls. One film started with bleating and clucking on the soundtrack, and this triggered a felicitous barnyard call-and-response; talk about surround sound. Nobody could explain to me the logic behind this FanTasia tradition–like streaking in the 70s, does it mean anything?–but its discreet silliness, perhaps distinctively Canadian, won me over. By the end I was joining in with a cracked miaou of my own. Yet once the movie starts, utter respect rules. Attentive silence is broken by appreciative laughter and whoops at those moments fans call OTT.

The festival’s ambitions are matched by the venues: raked Concordia University auditoriums with enormous screens and sound systems that envelop you. I sat in my favorite spot and didn’t regret it. Both film and digital projection looked sharp and bright. The staff get the audience in and out with dispatch, and everybody I met behaved with courtesy and good humor. Filmmaker Q & As are energetic and pointed. The movies are wild and sometimes abrasive, but the packaging is a model of civilized cine-festivity.

Never gonna grow up

You Are the Apple of My Eye.

The festival made its name with Asian popular cinema, and this year’s schedule didn’t disappoint. I could attend only the last week of screenings, so I missed some of the biggest titles, such as Peter Chan’s Wuxia, to be released in some markets as Dragon (innovative titling, eh? As we say in Canada.) But I did catch several entries.

You Are the Apple of My Eye, a Taiwanese rom-com, provides the now-standard mix of adolescent loutishness, romantic longing, and comic-book special effects. It starts with a twentysomething setting out for a wedding, and through flashbacks and voice-over, we learn of his high-school pranks and his surly affection for a charming girl in his class.

There’s always something touching about a gang of pals going their separate ways after school (viz., American Graffiti), so the film becomes more melancholy as the kids graduate and pass on to college and jobs; the only one who finds worldly success is a girl largely ignored by everyone. The plot shambles along, expecting us to be curious about whether the hero gets the girl he can’t quite learn to woo. The wedding culminates in a gag I found both clever and touching, a prolonged kiss–but not between the bride and our protagonist. And the motif of the ink-stained shirt, shown at beginning and end in a way that suggests a blue-bleeding heart, shows sophisticated sentiment.

School relationships are also character-defining in South Korean comedies, but their impact is more sub rosa in Love Fiction. Joo-wol is blocked after his first novel and is glumly working as a bartender. Attracted to a mysterious young woman, he pours all his literary talent into a Werther/ Cyrano effort to woo her. He even rhapsodizes about, and to, her armpit hair. Once they become a couple, however, he starts to write a murder thriller with her as a femme fatale. But his fiction leads him to investigate Hee-jin’s past, with disturbing results.

I thought this somewhat overlong movie tried to keep too many balls in the air–sequences dramatizing Joo-wol’s detective serial, flashbacks to his childhood, rumors about his girlfriend’s college sex life, and an excursion to Alaska. Again, though, it’s somewhat saved by a feel-good ending featuring Joo-wol’s friends in a scruffy band performing a karaoke video (above). As so often in the genre, stirring music redeems a meandering plot.

You Are the Apple and Love Fiction center on young men who grow up painfully, bruising others in the process, but Vulgaria keeps us firmly planted in adolescence. Pang Ho-cheung, who has done interesting work in You Shoot, I Shoot (a hitman hires a filmmaker to document his killings) and other projects, gives us what is being packaged as Hong Kong’s dirtiest comedy ever. Reliable sources report that no film has ever before contained such filthy Cantonese. It’s not quite as raunchy as it’s billed, though, and it has a predictably soft center.

You Are the Apple and Love Fiction center on young men who grow up painfully, bruising others in the process, but Vulgaria keeps us firmly planted in adolescence. Pang Ho-cheung, who has done interesting work in You Shoot, I Shoot (a hitman hires a filmmaker to document his killings) and other projects, gives us what is being packaged as Hong Kong’s dirtiest comedy ever. Reliable sources report that no film has ever before contained such filthy Cantonese. It’s not quite as raunchy as it’s billed, though, and it has a predictably soft center.

Chapman To plays a bottom-feeding movie producer who is drafted by a triad investor to make a sequel to the classic Confessions of a Concubine. The investor also insists on casting. He demands a part for the mule with which he seems to have an intensely physical relationship, and more centrally a role for Yum Yum Shaw, a decrepit beauty whom he remembers from the old days. Producer To agrees to all this while trying to keep the love of the daughter he shares with his divorced wife, and to continue a romance with a starlet with quality fellatio stylings. (Her secret weapon is Pop Rocks.) After an engaging setup, the plot gets thrown out of joint in typical Hong Kong fashion. To is knocked into a coma and recovers only to find the film finished and the patron displeased, not least because the director has redone the script with references to Al-Quaeda.

Not bad for a film shot in twelve days and made up as they went along. Still, I think that Pang made a capital mistake in not letting us see any of this bungled project. In particular, he set up the expectation that Yum Yum’s now sagging and plasticine face would be pasted on the starlet’s voluptuous body, and even cheap and clumsy CGI would have added to the fun. In any event, Vulgaria gets off some good-natured satire on the film industry in its financing crisis, and it provides many naughty laughs, not least in the sound effects that continue under the final credits.

Vulgarity was also the watchword in the Dutch comedy New Kids Turbo (2010). I was unaware of the TV comedy team New Kids, but their brand of politically incorrect slapstick is a little edgier than what we’d find in Hollywood. The aforementioned family-flattening gag and a passage in which policemen are amusingly shot probably wouldn’t make it past the producer notes in America.

Vulgarity was also the watchword in the Dutch comedy New Kids Turbo (2010). I was unaware of the TV comedy team New Kids, but their brand of politically incorrect slapstick is a little edgier than what we’d find in Hollywood. The aforementioned family-flattening gag and a passage in which policemen are amusingly shot probably wouldn’t make it past the producer notes in America.

Funny in small doses, this Five Stooges comedy of stupidity and aggression seemed to me to grow thin as it tried for more scale: the posse of dumb spongers refusing to pay for anything purportedly sets a model for the rest of Holland and calls forth repression from the authorities. I did learn that the planimetric framing on display in Napoleon Dynamite and Wes Anderson movies has become one default for harebrained humor in other countries. Or is it just an easier way to shoot groups of people?

Wuxia, fancy, plain, and very fancy

Painted Skin: The Resurrection.

Action cinema is a mainstay of FanTasia, and I caught several instances. Space Battleship Yamato is a live-action remake of the final installment in the anime series. As befits its origins, this version is rather classically directed, with prolonged medium shots and depth staging, as well as a soft texture that came through nicely on the 35mm print. It’s pure space-opera stuff, with a patriarchal captain passing authority to the young hothead and the emergence of romance between the hothead and the loyal young woman cadet. She turns out to be the secret source of energy that will turn the parched Earth into a green land again, but not without sacrifice in the long-established Japanese tradition.

To a large extent, the popular Chinese films of today are recycling tales and styles established by Hong Kong film in the 1980s and 1990s. Ching Siu-tung signed some of the best fantasy action films of those years (e.g., Duel to the Death, A Chinese Ghost Story, The East Is Red). Borrowing heavily from Tsui Hark’s 1993 Green Snake, The Sorceror and the White Snake offers your basic tale of the yearning and vengefulness of a woman-turned-demon. The main plot centers on White Snake, who falls in love with a herbalist and tries to pass for human. But Jet Li, looking like he’s suffered a few too many punches over the last three decades, is an abbot searching for demons to capture and imprison in his monastery. In a symmetrical subplot, the abbot’s young assistant turns into a bat demon but gains a friendship with White Snake’s counterpart Green Snake. When Li shows the herbalist his wife’s true nature, he breaks the marriage and unleashes White Snake’s fury.

Cue the video-game special effects for whirlwinds, floods, exploding temples, and soaring leaps. The airy effortlessness of all this comic-book spectacle made me yearn for the days of wirework; at least then gravitational heft limited the actors’ aerobatics. And cue a romantically inflated ending that pulls the couple apart to the tune of a duet sung by the pop-singer players on screen. A graceful, sinuous introduction of the two heroines (see the frame up top) and some interesting cutting in dialogue scenes (e.g., various scales of two-shots breaking up lines) couldn’t wipe away my sense that this has all been better done before–not least by Ching himself.

I did get my wire-work wish in Reign of Assassins, a pan-Asian project drawing on HK, PRC, Taiwanese, and Korean talent. Here Michelle Yeoh is given more to do than Jet Li was as the Sorceror. This film is engagingly old-fashioned, avoiding CGI for the most part and scaling the action to the everyday and the earth, not the sky. Michelle foreswears her past as an outlaw, undergoes the equivalent of plastic surgery, and tries to start fresh with a humble husband. But her old team’s search for the monk Bodhi’s corpse brings her back into action. In a plot twist reminiscent of the Shaw Bros. era, the husband reveals himself to be not all that she thought.

The fights are ingeniously staged by veteran Stephen Tung, but many are presented in that abrupt, disorienting framing and cutting that seems de rigueur these days. Taiwanese director Su Chao-pin is credited with story and direction, though a title on this print claimed the “co-director” to be John Woo, who was also a producer. On the whole, I respected Reign of Assassins more than I liked it. But nearly everybody thinks better of it than I do, as witness Justin Chang’s Variety review, the Hong Kong Movie Database reviews, and the customary detailed appraisal provided by Derek Elley in Film Business Asia. So maybe I should see it again.

The most elegant wuxia exercise I saw was Painted Skin: The Resurrection, fresh from its premiere at the Shanghai Film Festival (and in superb 35mm). King Hu made a version of the original tale in 1993, but this project has little relation to that, and only a tenuous one to the 2008 Hong Kong Painted Skin. That was a confused enterprise whose only redeeming feature seemed to me to be Donnie Yen. This installment more or less abandons the plot material of the 2008 film, while keeping many of the performers. It’s a solid, confident achievement, blending pathos, romance, and fantasy with an unhurried restraint largely missing from The Sorcerer and the White Snake.

Like that film, there’s a double plot centering on two female demons. A fox demon offers to swap her body for that of a disfigured princess, while in a minor-key subplot a bird demon develops affection for a demon hunter. Director Wuershan, fresh off his success with The Butcher, the Chef, and the Swordsman (2010), treats both the magic scenes and the erotic encounters with a grave warmth that elevates them above the genre standard. If you can have dignified eye candy, this movie offers it: sumptuous costumes and sets, striking but not go-for-broke special effects, combats that discreetly exploit the stammering ramping effects of 300. But the oscillating relations of the two central woman, tracing rivalry, complicity, envy, and loss, remain firmly at the action’s center.

Hong Kong filmmakers developed these mythic formulas in the 1980s and 1990s, when such “feudal” and “superstitious” subjects were forbidden on mainland screens. The slick assurance with which new mainland filmmakers have mastered this material suggests that in the new liberalization of the mainland market, they now own this genre. Painted Skin: The Resurrection has quickly become the biggest box-office hit in PRC history.

Crossovers

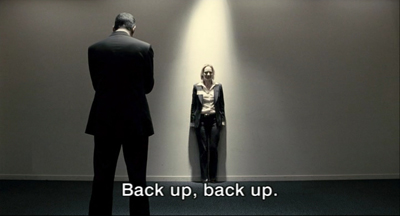

Carré blanc.

Everyone has noticed that genre pictures are getting artier, or art films are getting more genre-fied. Crossover efforts can yield strong results, as shown by movies as different as Let the Right One In and Drive. The title Eddie the Sleepwalking Cannibal would seem to signal B-movie giggles and gasps, but it turns out to be a tight, restrained study of the sadism driving artistic creativity….and a certain number of giggles and gasps.

A painter in a career slump, and following an unspecified “accident,” accepts a teaching post in a Canadian art school in hopes of calming down. He takes in a mentally deficient young man who grabs and eats animals while he’s sleepwalking, or sometimes sleeprunning.  When you learn that the painter’s neighbor is an obnoxious oaf with a perpetually barking dog, you begin to think that Eddie will be the painter’s means of securing peace and quiet. Actually, Eddie’s depredations unlock the painter’s creativity, inspiring a new burst of excellent work. Thereafter, he’ll need to keep Eddie on the prowl.

When you learn that the painter’s neighbor is an obnoxious oaf with a perpetually barking dog, you begin to think that Eddie will be the painter’s means of securing peace and quiet. Actually, Eddie’s depredations unlock the painter’s creativity, inspiring a new burst of excellent work. Thereafter, he’ll need to keep Eddie on the prowl.

The film balances gore, comedy, pathos, and satire of the art world. When the painter realizes that the young woman he’s slept with is a good sculptor, his efforts to deflate her using CritiqueSpeak reveal that his apparent humility covers an angry competitiveness. Eddie isn’t exactly Henry James on the creative process, I admit, but it’s not A Bucket of Blood either. The movie looks very trim and polished, with excellent sound work; I regret only the tendency to treat every dialogue scene in a fusillade of tight close-ups, which leads to a fairly unvarying pace. There’s a reason Coen brothers cut fairly slowly and stay far back; this sort of queasy deadpan tension benefits from steadiness and silence.

The screening of Carré blanc was preceded by La Jetée, as a tribute to Chris Marker. It was completely appropriate. For one thing, La Jetée hinges on one of the paradoxes of time travel: Can a man witness his own death? This sort of mind-bending was amusingly dealt with in Aleksey Fedorchenko’s “Chrono Eye,” one of three shorts in the portmanteau movie The Fourth Dimension. A scientist clamps a camera to his head and tries to tune himself to the future or the past, with the results transmitted to a beat-up TV receiver. The film makes clever use of the fallen-camera convention, and it ends with a rejection of past and future in the name of a vivacious present.

La Jetée was prophetic in another way. Before Marker’s film, most science fiction movies, from Metropolis and Things to Come to The Time Machine, used fanciful sets to conjure up the future. But Marker realized that one could film today’s cities in ways that suggested that the future was already here. This opened up a rich vein of exploration in Alphaville, THX 1138, Le Dernière combat, and their successors. And if you haven’t noticed: That future-tense present is always bleak, totalitarian, and something to escape from.

No wonder, then, that Carré blanc becomes an arty dystopian fable about a boy and girl brought up in a totally administered society. Philippe’s mother commits suicide so that he can be taken into an orphanage. There he will be turned into “a normal monster,” thus assuring his survival. Grown-up, he’s a high-level bureaucrat administering childish tests that his victims never seem to pass. But his marriage to Marie is withering. They can’t have a child, and she spends her days wandering the city. Eventually things come to a crisis and the couple must decide whether to stay or try to flee.

The plot is pretty formulaic and some of the absurd touches seem forced (the national sport is croquet). But the pictorial handling engages your interest from the start. Call it “1984 meets Red Desert,” except that there’s not much red here: bronze, black, and amber dominate. Simple techniques, like lighting that hollows out people’s faces to the point of blankness, become very evocative.

As in Alphaville, actual locations are made sinister by the dry public-address announcements saturating the soundtrack. The vast net stretched outside the couple’s apartment complex recalls the harrowing images of suicide-prevention nets at Chinese factory complexes. What a pleasure to see a movie designed shot by shot; the fixed camera yields one startling composition after another. Familiar as the story and themes are, the style grows organically from them. Carré blanc was the most impressive piece of atmospheric cinema I saw in my FanTasia visit.

So why was I here?

To see the movies. To catch up with old friends like Peter Rist and King Wei-chun and to make new ones. To present a talk on the Hong Kong action tradition. And to get an award for “Career Excellence.” Say hello to my lee’l (actually not so lee’l) frien’.

I’m very grateful to the coordinators of FanTasia for inviting me and honoring me with this magnificent award. It was an unforgettable week.

In addition to all this, FanTasia held an avant-premiere of the exhilarating ParaNorman (below). After I’ve seen it again, preferably with Kristin, I hope to write about it here.

Jason Seaver has blogged loyally about the festival on a daily basis. Liz Ferguson has a series of articles in the Montreal Gazette. A short interview with me appears on the FanTasia YouTube channel. Juan Llamas Rodriguez offers a two-part commentary on it starting here.

P. S. 11 August 2012: Daniel Kasman of MUBI has provided a link to Chris Marker’s little-known site Gorgomancy, which includes viewing copies of some of his little-known films.

P. P. S. 13 August 2012: Marc Lamothe–film director, co-director of FanTasia, and creator of DJ XL5’s Italian Dance Party–writes to explain the origin of the meowing.

Besides my national genre cinema tribute, every year since 2004 I’ve edited a short film program for FanTasia. It’s constructed the same way the Italian zappin’ was. I put static between films and include old vintage videos, ads and obscure film trailer in between films to simulate an evening of zappin’. This brings an energy and rhythm to short film presentations.

In 2008, I had a screening entitled DJ XL5’s DJ XL5’s Hellzapoppin Zappin’ Party. The program was constructed in 2 parts, with each part on a 60-min beta tape. Both part one and two contained episodes of Simon Tofield’s Simon’s Cat. To switch from beta one to beta two meant some 30 seconds of blackness and silence in the room. As Simon’s Cat made a strong and loving impression on the crowd, during the short intermission for chaning from tape 1 to 2 some people started meowing to break the silence. That made the others laugh and signaled their affection for the character.

This inside joke spilled over into more serious film presentations and has became a staple of our audience. Here’s the film responsible for the phenomena: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w0ffwDYo00Q.

Thanks to Marc for the information, and for a fine festival. Thanks also for his kind words about our work; he read the second edition of Film Art back in the early 1980s!

Time for a quick one: A miscellany from friends

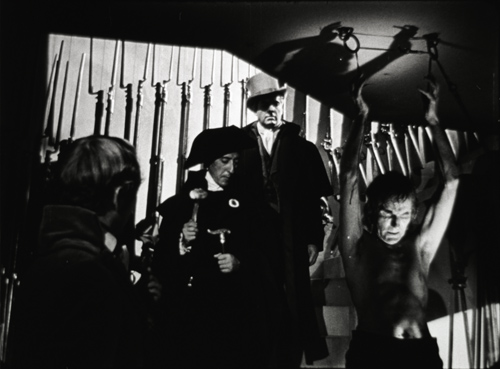

The Black Book (aka Reign of Terror).

DB here, catching up with books, videos, and events:

David Cairns has written a lively appreciation of William Cameron Menzies for the March/ April issue of The Believer. The essay bristles with rapid-fire aperçus, such as the suggestion that the great, demented Kings Row is something like the Twin Peaks of its day. David is particularly good at plotting the extent to which Menzies dominated the work of his directors. Directors without a visual style of their own, he points out, were easy for Menzies to overwhelm, but those with an already-developed signature could assimilate his contributions, as Hitchcock did in Foreign Correspondent.

David Cairns has written a lively appreciation of William Cameron Menzies for the March/ April issue of The Believer. The essay bristles with rapid-fire aperçus, such as the suggestion that the great, demented Kings Row is something like the Twin Peaks of its day. David is particularly good at plotting the extent to which Menzies dominated the work of his directors. Directors without a visual style of their own, he points out, were easy for Menzies to overwhelm, but those with an already-developed signature could assimilate his contributions, as Hitchcock did in Foreign Correspondent.

In The Black Book (aka Reign of Terror) Menzies found soul mates in two other aggressive pictorialists, Anthony Mann and John Alton, the team becoming “a crazy triangle,” eager to indulge in “thrusting gargoyle faces in fish-eye distortion, clutching shadows, and funky, teetering compositons.” Bob Cummings never looked so bizarre, before or since. I didn’t talk about this wild movie in my online Menzies material here and here because I had such poor illustrations from it. Now things have changed, and a decent, or perhaps rather indecent, sample of the film’s delirium (above) can serve to back David’s point.

David’s “Dreams of a Creative Begetter” is one of several film-related pieces in this issue of The Believer. The issue includes a DVD of the seminal People on Sunday (Menschen am Sonntag, 1930), which gathered the talents of Billy Wilder, Curt Siodmak, Robert Siodmak, Edgar G. Ulmer, Fred Zinnemann, and Rochus Gliese. A helpful introductory essay is at the Believer site.

Speaking of David’s writing, don’t miss his superb shot-by-shot analysis of a key scene in Gilda at his Shadowplay site, an obligatory stop for all cinephiles.

Seldom does a monograph on a single film probe so deeply as Mette Hjort’s new book on Lone Scherfig’s Italian for Beginners. It’s easy to take this movie as Dogme Lite, since compared to the earliest, rather harrowing Dogme efforts, it’s an ingratiating romantic comedy-drama. Mette does justice to this side of Scherfig’s film, but she also shows that it’s an exercise in moral seriousness. Reconstructing the production process, she conducts in-depth analysis of performance and technique. She is sensitive to actors’ moments, such as simply laying down a knife and fork; aware that these gestures are developed through improvisation, she is able to trace how each character is built up through details.

In her books and articles on the Dogme school Mette has shown that its innovations go beyond the vaunted technical “rules.” She always addresses them, of course; here she provides an illuminating typology of ways the rules have been followed or dodged. But she also stresses, as most writers don’t, that Dogme films engage with matters of political importance. For example, she has shown that The Idiots’ controversial display of “spazzing” triggered an important debate about Danish attitudes toward the disabled. In her new book Mette indicates that Scherfig’s efforts to endow her characters with the dignity to be found in everyday life offers viewers a chance “to re-connect with one of their culture’s most powerful moral commitments.” Mette talks about the project in this video.

David Gordon Green directs Your Highness; Justin Lin signs his third Fast & Furious movie. With indie filmmakers eagerly joining the tentpole and franchise business, the whole phenomenon seems due for a rethink. This makes Michael Z. Newman’s Indie: An American Film Culture all the more necessary. Although I can’t be unbiased, because I served as Michael’s advisor on the dissertation that became the book, I think that any reader would find the result a fresh and vigorous exploration of the achievements of the Sundance/ Miramax generation.

David Gordon Green directs Your Highness; Justin Lin signs his third Fast & Furious movie. With indie filmmakers eagerly joining the tentpole and franchise business, the whole phenomenon seems due for a rethink. This makes Michael Z. Newman’s Indie: An American Film Culture all the more necessary. Although I can’t be unbiased, because I served as Michael’s advisor on the dissertation that became the book, I think that any reader would find the result a fresh and vigorous exploration of the achievements of the Sundance/ Miramax generation.

Michael starts by looking closely at the audiences and marketing. He suggests that viewers engage with the films through particular viewing habits (e.g., “Characters are emblems”). He then shows how these habits were nourished and refined by distributors, promotion, and film festivals. The next two sections of the book consider what we might take to be the two poles of indie difference from Hollywood: greater realism, and more self-conscious artifice. The central chapters analyze realism in relation to “character-centered” filmmaking in the Indie trend. Michael turns a critical eye on characterization in films as different as Walking and Talking, Lost in Translation, and Welcome to the Dollhouse. The third batch of chapters considers the trend’s other major appeal, the sort of play with style and form we get in the Coens, Tarantino, Nolan, and others.

Michael shows how character-driven realism and gamelike artifice mesh well with the mandates of distribution and reception—how, in effect, “originality” becomes something that can be calculated and branded. The book concludes with thoughts on the evolution of the trend, comparing Happiness with Juno and raising the inevitable question: How artistically independent is independent film? Newman leaves us pondering: “Indie cinema has become Hollywood’s most prominent alternative to itself.”

One of the hallmarks of the Wisconsin program in film studies is its nuanced refusal of the art/ commerce duality that supposedly rules filmmaking. From many angles, researchers here have shown that creative impulses and business mandates mix in complicated ways, and the results are often fascinating. Indie is one example of this sort of research project, and so is another dissertation-become-book, Christopher Sieving’s Soul Searching: Black-Themed Cinema from the March on Washington to the Rise of Blaxploitation. (Again, I was involved, serving on the committee chaired by Tino Balio.)

One of the hallmarks of the Wisconsin program in film studies is its nuanced refusal of the art/ commerce duality that supposedly rules filmmaking. From many angles, researchers here have shown that creative impulses and business mandates mix in complicated ways, and the results are often fascinating. Indie is one example of this sort of research project, and so is another dissertation-become-book, Christopher Sieving’s Soul Searching: Black-Themed Cinema from the March on Washington to the Rise of Blaxploitation. (Again, I was involved, serving on the committee chaired by Tino Balio.)

Chris concentrates on 1960s black-themed films from A Raisin in the Sun onward, because he wants to trace how filmmakers tried out a variety of ways to represent and comment on black life. It was a transitional era, but as he puts it “because of the insights they reveal about the periods that bracket them, transitional periods are among the most fascinating and significant in all of film history.”

For Chris, Gone Are the Days (1963), The Cool World (1964), Uptight (1968), The Landlord (1970), and the unproduced Confessions of Nat Turner provide case studies of alternatives to what became the crime-and-comedy product of blaxploitation. Why did decision-makers believe that black-themed films would sell broadly enough to repay investment? What choices and compromises were necessary to “universalize” material (for white viewers) while also retaining “authentic” blackness? Or was it better simply aim the films at white liberals?

Chris tackles such questions through a painstaking study of the film industry’s efforts to find, or create, an audience for films that took great risks. Written with verve (on the screen handling of the Black Panthers, Chris talks about Hollywood’s “Black Power outage”), Soul Searching revives films that are all but forgotten and shows how their efforts to create one variety of independent cinema failed for particular social and industrial reasons.

Someone I’ve been meaning to spotlight for a while: Frédéric Ambroisine is a multitalented critic, filmmaker, stuntman, and collector based in Paris. One of his careers is making supplements for French DVD releases of Hong Kong films, both classic and current. If you have even a smattering of French, you can follow his supplements with ease. He gets precious interviews with screen legends like Kara Hui Ying-hung and Ku Feng (below), master villain of the great New One-Armed Swordsman.

The videos from Wild Side often include Fred’s featurettes. You can follow Fred’s activities at actionqueens.com and alivenotdead. Much of the material in both places is in English.

Finally, if you’re in Los Angeles this week, why not visit the celebration of Orphan Films playing at UCLA 13 and 14 May? While I was in New York in February, I met NYU’s Dan Streible, moving spirit of the Orphan Films movement. Dan and his colleagues work with archives, collectors, and filmmakers to save films that fall through the cracks, digging up everything from home movies to news clips and experimental cinema. Dan curated a program of orphans at our local festival earlier this spring. At UCLA he will be a guest for screenings and discussions of many orphan titles, including the mysterious Madison Newsreel (Madison, Maine alas, not Wisconsin). Go here for Sean Savage’s discussion of the orphan oddity that has become a cult movie, and here for background on Northeast Historic Film, which found the footage.

PS: Speaking of friends, I should thank the solicitous people who wrote me during my recent illness. I appreciate your get-well notes, and I’m happy to report that I’m on the mend.

“World’s Youngest Acrobat” (Hearst Metrotone/ Fox Movietone 1929). From Orphans 7: A Film Symposium.

The buddy system

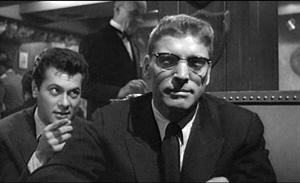

Sweet Smell of Success.

DB here:

Many of our friends write books, and what are friends for if not occasionally to promote each other’s books? Here’s an armload of titles, most of them recently published. They’re so good that even if the authors weren’t our friends and colleagues, I’d still recommend them.

James Naremore has made major contributions to film studies since his fine monograph on Psycho, published way back in 1973. That book remains one of the most sensitive analyses of this much-discussed movie. Now he has another monograph, on the stealth classic Sweet Smell of Success. When I was coming up, Alexander Mackendrick wasn’t much appreciated, and this movie slipped under the radar. More recently it has emerged as one of the model films of the 1950s, and not just for James Wong Howe’s spectacular location cinematography. It’s a very brutal story, with Tony Curtis playing against type as venal press agent Sidney Falco and Burt Lancaster as J. J. Hunsecker, a monstrously vindictive newspaper columnist.

Jim’s book provides a scene-by-scene commentary but also more general analysis of production circumstances and directorial technique. An enlightening instance is what Mackendrick called “the ricochet”—when character A talks to character B but is aiming at character C. This allows the filmmaker great flexibility in framing and cutting, often showing C’s reactions while we hear the dialogue offscreen. In the shots surmounting this blog, Sidney is needling J. J. by asking the Senator if he approves of capital punishment. Jim’s book joins his work on Welles, Kubrick, and film noir as part of a subtle reassessment of American postwar cinema.

With the current revival of interest in André Bazin’s film theory, it’s fruitful to look again at the “classical” theoretical tradition in which he participated. “Classical” here refers to the very long period before the emergence of semiotic and psychoanalytic theories of cinema in the 1960s. The newer theories have somewhat beclouded our recognition of how imaginative and wide-ranging the old folks were. In Doubting Vision: Film and the Revelationist Tradition, Malcolm Turvey scrutinizes four thinkers who saw film as having the power to show us things beyond (or above, or below) surface reality. In the spirit of analytic philosophy, Turvey carefully lays out the positions of Béla Balázs, Jean Epstein, Siegfried Kracauer, and Dziga Vertov before asking whether their claims hold up.

With the current revival of interest in André Bazin’s film theory, it’s fruitful to look again at the “classical” theoretical tradition in which he participated. “Classical” here refers to the very long period before the emergence of semiotic and psychoanalytic theories of cinema in the 1960s. The newer theories have somewhat beclouded our recognition of how imaginative and wide-ranging the old folks were. In Doubting Vision: Film and the Revelationist Tradition, Malcolm Turvey scrutinizes four thinkers who saw film as having the power to show us things beyond (or above, or below) surface reality. In the spirit of analytic philosophy, Turvey carefully lays out the positions of Béla Balázs, Jean Epstein, Siegfried Kracauer, and Dziga Vertov before asking whether their claims hold up.

I’m not giving much away by revealing that Malcolm thinks the revelationist tendency has its problems. But his purpose isn’t simply to reject the position. He treats it as an instance of what he calls “visual skepticism,” the idea that we ought to treat our ordinary intake of the world as something suspect. This idea, Malcolm argues, is central to modernism in the visual arts. He extends his critique of visual skepticism to more recent theorists as well, notably Gilles Deleuze, and he shows how his own ideas apply to films by Hitchcock, Brakhage, and other directors. Malcolm’s book is a model of theoretical clarity and probity, and a stimulating read as well.

Skepticism of another sort is central to Carl Plantinga’s Rhetoric and Representation in Nonfiction Film. One result of semiotic theory was to question whether a film could ever adequately represent reality. If a movie is only an assembly, however complex, of conventional signs, it can’t give us access to something out there. Even a documentary, some theorists argued, had no privileged access to the real world, let alone to general truths. “Every film is a fiction film” was a refrain often heard at the time. Carl tackles this assumption head-on by carefully arguing that just because a documentary is selective, or biased, or rhetorical, that doesn’t mean that it can’t affirm true propositions about our social lives.

Like Malcolm, Carl brings a philosopher’s training in conceptual analysis to debates about the ultimate objectivity of any documentary. In adopting a position of “critical realism” opposed to skepticism, Carl examines the realistic status of images and sounds, the way documentaries are structured, and filmmakers’ use of technique. He shows, convincingly to my mind, that a documentary may offer an opinion and still be objective and reliable to a significant degree. Carl’s 1997 book went out of print before it could be published in paperback. He has enterprisingly reissued it as a print-on-demand volume, and it’s available here.

To take film theory in another direction, there’s Evolution, Literature, and Film, edited by Brian Boyd, Joseph Carroll, and Jonathan Gottschall. As a wider audience has become aware of the power of neo-Darwinian thinking, more and more scholars have been arguing that evolutionary theory can shed light on aesthetics. The most visible effort recently is Denis Dutton’s The Art Instinct.

To take film theory in another direction, there’s Evolution, Literature, and Film, edited by Brian Boyd, Joseph Carroll, and Jonathan Gottschall. As a wider audience has become aware of the power of neo-Darwinian thinking, more and more scholars have been arguing that evolutionary theory can shed light on aesthetics. The most visible effort recently is Denis Dutton’s The Art Instinct.

For some years Brian, Joe, and Jonathan have been in the forefront of this trend, with many books and articles to their credit. Their anthology pulls together broad essays on biology, evolutionary psychology, and cultural evolution before turning to art as a whole and then focusing on literature and cinema. There are also pieces displaying evolutionary interpretations of particular works, and a finale that provides examples of quantitative studies of genre, gender variation, and sexuality, including an article called “Slash Fiction and Human Mating Psychology.”

Among the film contributors are other friends like Joe Anderson, a pioneer in this domain with his 1996 book The Reality of Illusion, and Murray Smith, who provides an acute piece called “Darwin and the Directors: Film, Emotion, and the Face in the Age of Evolution.” There are also essays of mine, drawn from Poetics of Cinema. In all, this book presents a persuasive case for an empirical, broadly naturalistic approach to the arts.

By the way, the same team is involved with an annual, The Evolutionary Review, edited by Alice Andrews and Joe Carroll. Its first issue offers articles on Facebook, musical chills, women as erotic objects in film, and Art Spigelman’s In the Shadow of No Towers (by Brian Boyd).

Some books emerge from conferences, and Tom Paulus and Rob King’s Slapstick Comedy is a good instance. Based on “(Another) Slapstick Symposium,” held at the Royal Film Archive of Belgium in 2006, the anthology brings together a host of experts who look back at madcap comedy in American silent film. There are essays on particular creators—Griffith, Sennett, Fatty, and Chaplin, inevitably—as well as pieces on slapstick parodies of other movies and the genre’s relation to modernity, also inevitably. Tom Gunning offers a fine analysis of Lloyd’s Get Out and Get Under (1920), concentrating on a complex string of gags around an automobile. The collection gathers work by some of the outstanding scholars of silent film while also, of course, making you want to see these crazy movies again.

You also want to see all the movies lovingly evoked by Gary Giddins in Warning Shadows: Home Alone with Classic Cinema. As indicated in another blog entry, I find Giddins one of the best appreciative critics we’ve ever had. Any essay, indeed almost any sentence, cries out to be quoted. Here he is on Edward G. Robinson:

You also want to see all the movies lovingly evoked by Gary Giddins in Warning Shadows: Home Alone with Classic Cinema. As indicated in another blog entry, I find Giddins one of the best appreciative critics we’ve ever had. Any essay, indeed almost any sentence, cries out to be quoted. Here he is on Edward G. Robinson:

His round, thick-lipped, putty face could brighten like paternal sunshine or shut down in implacable contempt or stall with crafty desperation or pontificate with ingenuous wisdom; his short, stumpy, erect frame could sport a tailor-made as smartly as Cary Grant.

Some of the pieces in Giddins’ latest collection were designed to accompany DVDs, but they will outlast this evaporation-prone genre. Other reviews come from the New York Sun, which gave him freedom to mix and match his subjects: Young Mr. Lincoln and Lust for Life (both biopics), Lady and the Tramp and Miyazaki movies. The collection opens with Giddins’ thoughts on how changes in film exhibition, from nickelodeons to digital screens, have altered our relationship with the movies. This isn’t just nostalgia, because his survey allows him to celebrate the power of DVD to exhume forgotten titles. The standards for a film classic, he notes, “are gentler and more flexible” than those in appraising other arts. “The passing decades are a boon to the appreciation of stylistic nuance that gives certain melodramas and genre pieces the heft of individuality.”

Who was Segundo de Chomón? In the 1970s, I kept finding that films I thought were by Méliès turned out to bear this mysterious signature. You imagine a man in a cape and a floppy hat. Photographs show someone a little less operatic, but with a superb mustache. Today he’s far from a mystery, although many of his movies can’t be fully identified. Several scholars have followed his trail, none more thoroughly than Joan M. Minguet Batllori in Segundo de Chomón: The Cinema of Fascination.

Chomón started as a cinema man-of-all-work in Barcelona, translating film titles, distributing copies, and producing films for Pathé. After moving to Paris in 1905, he continued working for the company and established his fame with trick films. He returned to Barcelona to create a production company, but that failed. On he went to Italy, where he specialized in visual effects, most famously for Cabiria (1914).

In his Parisian Pathé years, he was in charge of all the studio’s trick films, which included not only stop-motion, superimpositions, and other effects but also marionettes and animation. Joan argues that he was a prime exponent of the “cinema of attractions,” Tom Gunning’s term for that early mode of filmmaking which aims to startle and enchant the audience. A famous instance is Kiriki, acrobats japonais (1907), which shows gravity-defying stunts.

Chomón accomplished this by shooting from straight down, filming the performers on the floor. They had to simulate leaps and flips as they rolled along each other’s bodies, and then they had to slip perfectly into position. This English edition of Joan’s book on Chomón, full of information and providing a “provisional filmography” along with many pages of gorgeous color images, will be available soon here.

We recently noted the anniversary of our book on classic studio cinema, a 1985 project in which we bypassed talking about exhibition. That part of the industry has been a scholarly growth area in the years since, and one of the newest yields is Epics, Spectacles, and Blockbusters: A Hollywood History, by Sheldon Hall and Steve Neale. It’s a chronological account of Big Movies, from the earliest features to the digital era, and it concentrates on how such films have been marketed and shown. It explains how exhibition changed across the decades, and how we got the phenomenon of the “roadshow” movie, the film shown selectively (only certain cities), at intervals (perhaps only one matinee and one evening screening), and at more or less fixed prices. My middle-aged readers will remember roadshow releases like The Sound of Music (1965), although there were many before and even a few since.

We recently noted the anniversary of our book on classic studio cinema, a 1985 project in which we bypassed talking about exhibition. That part of the industry has been a scholarly growth area in the years since, and one of the newest yields is Epics, Spectacles, and Blockbusters: A Hollywood History, by Sheldon Hall and Steve Neale. It’s a chronological account of Big Movies, from the earliest features to the digital era, and it concentrates on how such films have been marketed and shown. It explains how exhibition changed across the decades, and how we got the phenomenon of the “roadshow” movie, the film shown selectively (only certain cities), at intervals (perhaps only one matinee and one evening screening), and at more or less fixed prices. My middle-aged readers will remember roadshow releases like The Sound of Music (1965), although there were many before and even a few since.

Sheldon and Steve trace in unprecedented detail the cycles of blockbusters that have run throughout American cinema. In the process they refreshingly redefine the very idea. We don’t usually think of The Best Years of Our Lives as a Big Movie, but it runs three hours and was considered a “special” production, comparable to the more obvious sprawl of Duel in the Sun. The authors bring the story up to date by considering today’s event movies as a “Cinema of Spectacular Situations.” Yes, that category includes comic-book films, Inception, and, of course, the 3D sagas that may finally be wearing out their welcome. (My editorializing, not theirs.)

Japanese cinema is endlessly fascinating in all its eras; I’d argue that in toto it’s one of the three greatest national cinemas in film history. The postwar period is exceptionally interesting because of the American occupation (1945-1951) and its effects on Japanese film culture. This period has already provoked one of the best books we have on Japanese cinema, Kyoko Hirano’s Mr. Smith Goes to Tokyo, and it finds a worthy accompaniment in Hiroshi Kitamura’s Screening Enlightenment: Hollywood and the Cultural Reconstruction of Defeated Japan. Kyoko focused on how US policy shaped domestic filmmaking, while Hiroshi asks how the Occupation helped American studios penetrate the local market.

Over six hundred Hollywood movies poured into Japan during the period, and Hiroshi traces how local tastemakers as well as U.S. policymakers drew audiences to them. Young Japanese learned about the Academy Awards, assembled in movie-study clubs to discuss what they were seeing, and were urged to consider even a gangster tale like Cry of the City (1950) as demonstrating the humanistic side of democracy. A center of this activity was Eiga no tomo (“Friends of the Movies”), a magazine that went beyond entertainment news and tried to reshape the tastes of young people. In sharp prose and vivid evidence, Hiroshi captures the ways in which American cinema promised to help heal a devastated country.

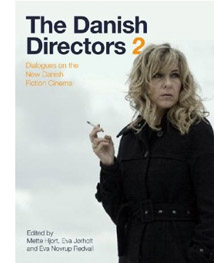

The Danish Directors, by Mette Hjort and Ib Bondebjerg, has become a standard companion to the most successful “small cinema” on the European scene. Now it has a successor in The Danish Directors 2: Dialogues on the New Danish Fictional Cinema, edited by Mette, Eva Jorholt, and Eva Novrup Redvall. Once again, we get lengthy, in-depth interviews covering the value of film education, the vagaries of funding, and filmmakers’ creative decision-making. Lone Scherfig, Christoffer Boe, Per Fly, Paprika Steen, and many other major figures are included. (Disclosure: The editors were kind enough to dedicate the book to me.)

The Danish Directors, by Mette Hjort and Ib Bondebjerg, has become a standard companion to the most successful “small cinema” on the European scene. Now it has a successor in The Danish Directors 2: Dialogues on the New Danish Fictional Cinema, edited by Mette, Eva Jorholt, and Eva Novrup Redvall. Once again, we get lengthy, in-depth interviews covering the value of film education, the vagaries of funding, and filmmakers’ creative decision-making. Lone Scherfig, Christoffer Boe, Per Fly, Paprika Steen, and many other major figures are included. (Disclosure: The editors were kind enough to dedicate the book to me.)

While the first volume is a rich storehouse of information on Danish film in “the Dogma era,” the newest volume shows how directors (some of whom made Dogma projects) have gone beyond it. In preparing 1:1, a film about Danes and Arab immigrants living in a housing project, Annette K. Olesen had a full script but concealed it from the non-professional cast. After getting the performers comfortable with ordinary situations, she began staging scenes while encouraging improvisation. Screenwriter Kim Fupz Aakeson incorporated the improvised material into revisions of the script.

By contrast, the prolific director-screenwriter Anders Thomas Jensen (Adam’s Apples, The Green Butchers), relies on strong structure, with lean expositions and sharply defined climaxes. He appreciates clean filming technique too.

It’s easy to make something that’s ugly and handheld, but you have to take telling stories with images seriously. You have to take the language of film seriously. Many Danish directors have started doing this in recent years and it’s wonderful, because there was a time when everything looked Dogma-like and I found myself thinking, “It’s got to stop now.”

To those who think that Danish cinema is at risk of becoming a cinema of cozy liberal reassurance, this collection offers many salutary signs. Every director speaks of the need to keep innovating, to push ahead provocatively. Simon Staho, whose Day and Night seems to me one of the most adventurous Danish films of recent years, aims at utter purity: “My task is to figure out how to add as little as possible to the black screen. The damned problem is that you have to add image and sound!”

What makes all these books exciting to me is a willingness to test ideas–sometimes very general ones–about cinema and the wider world by examining film as a distinctive art form. Even the most conceptual books on this week’s shelf are firmly rooted in the particular choices that creators make and the concrete ways that viewers respond.

Next stop: Vancouver International Film Festival. Whoopee!

Day and Night.

Dreyer re-reconsidered

The President (1920).

DB here:

I was late to the feast, but my contribution to the Dreyer site is now up, thanks to Lisbeth Richter Larsen‘s quick work. You can read it here.

Danish cinema was the first national cinema I studied, and Dreyer was my point of entry. I went to Copenhagen in 1970 to see his films for a little book I wrote in the Movie/ Studio Vista series. The manuscript was finished but never published because the series ceased. Good thing for me. I’d be embarrassed today if that book was still floating out there.

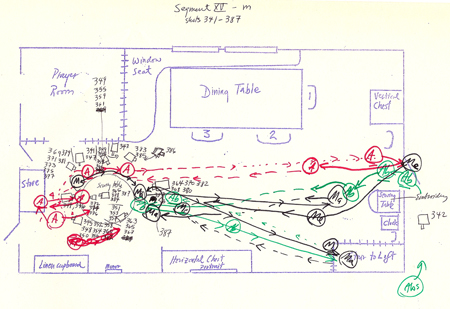

Kristin and I went back to Copenhagen in 1976 to re-watch the Dreyer oeuvre, and I saw the films with new eyes. I had learned a lot more about film analysis and film history, so I was able to see different things in his movies. Now obsessed with how films construct space and time, I drew up elaborate and clumsy plans of actor blocking, camera setups, and camera movements.

What? You don’t recognize this as a string of shots from Day of Wrath? I even notated actor movements offscreen (with dotted lines).

The result of all this fussbudgetry was a 1981 book on Dreyer. I think that some of the ideas there still hold up. But as I learned more about film history in the 1990s, I came to believe that some of my conclusions were off-base.

In particular, my treatment of Gertrud as a radical, deliberately “empty” film seemed tenuous. Influenced by minimalist cinema of the 1970s, especially that of Straub and Huillet (huge admirers of Dreyer), I pushed the case that at the end of his life Dreyer dared to make a movie that was by all ordinary standards simply boring.

Steadier heads tried to talk me out of it, but I clung to the idea. What can I say? I was young and stubborn.

As I studied more cinema of the 1910s, I began to see Dreyer’s career, and particularly his silent films, as tied in complicated ways to other films of that period–not least Danish cinema. For, as I’ve sketched here, Danish cinema of the 1910s was one of the richest traditions of “tableau” staging in Europe. I was able to put my ideas about the Danes’ achievements into clearer form in the last chapter of On the History of Film Style and in an invited essay on the Nordisk company published in a collection at the Danish Film Institute.

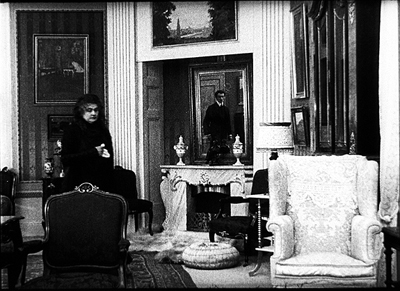

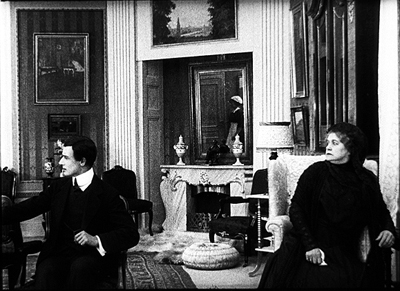

Like their peers in other countries, the Danes often stuffed their shots with furniture and props, in a riot of patterns and textures. Here is an example from Den Frelsende Film (The Woman Tempted Me, 1916). It survives only in fragments, but those fragments are in fine shape.

In addition, the Danes developed elaborate lighting patterns and complex, somewhat Gothic special effects. You can see these options in Ekspressens Mysterium (Alone with the Devil, 1914) and Doktor Voluntas (1915).

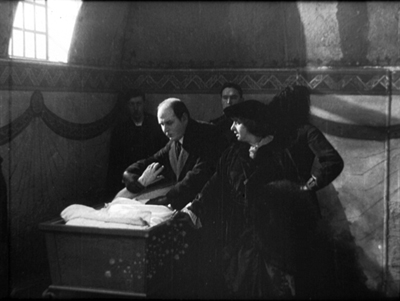

Above all there was the intricate staging in depth, often using mirrors. Here’s a seldom-seen example. In Under Blinkfyrets Straaler (Under the Lighthouse Beam, 1913), the father has died, and his wife and son meet in the parlor. A mirror catches them entering, in phases.

The mirror shows Hugo entering the room by moving straight and forward, but when he gets into the shot he comes in somewhat diagonally from the left.

After a moment of sitting in silence, mother and son turn as a maid enters. They look off left, but because we’ve seen Hugo enter in the mirror, we look to the center and see her reflection as she shuts the door.

The maid brings the widow a letter from her other son, Robert. Hugo, fretful, departs and in the mirror we see him look back at his mother.

Or does he? The angle of his glance makes sense compositionally: In reflection Hugo seems to be meeting his mother’s eyes, left to right. But in my first frame, he advanced into the room by looking straight ahead. If he looked straight into the room again now, he’d be looking more or less at us, not at his mother. So I suspect that in my last frame, the actor is actually not looking directly at the actress but off at an angle. He has been directed to this position to allow the mirror to create an artificial, but highly readable, image.

The novice Dreyer, I realized, didn’t indulge in such tableau trickery. His first two films, The President (made in 1918) and Leaves from Satan’s Book (made in 1919), are quite different from the norms that ruled his local cinema. By the time he came to directing, he was more oriented toward analytical editing and fairly flat staging than were the old guard. In this regard he was closer to a younger group of filmmakers emerging at the same time in other countries: Gance, Lang, Murnau, Joe May, and many others, along with Americans like Ford, Walsh, et al. So my newest take is that Dreyer is part of a generation of directors moving toward an editing-driven cinema and away from the tableau style. This idea in turn helped me see Gertrud in a more convincing light.

If you want the argument in full, you can check it on the Dreyer site. The lesson for me is twofold. (A) Dreyer is inexhaustible. (B) The more you learn about cinema (and about life), the more you can see in films that you think you have already understood.

The only book in English surveying the cinema of Dreyer’s elders is Ron Mottram’s indispensable The Danish Cinema before Dreyer (Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow, 1988). It doesn’t consider the dual traditions of staging and editing, but it offers a very thorough history of studios, directors, and genres, and mentions some stylistic patterns. The article I referred to is “Nordisk and the Tableau Aesthetic” in Lisbeth Richter Larsen and Dan Nissen, eds., 100 Years of Nordisk Film (Copenhagen: Danish Film Institute, 2006), 80-95. This gorgeous book can be ordered from the DFI shop;I’ll be adding my essay here some time this summer.

For more on the tableau tradition, go to other blog entries here and here and here and here. On the emergence of continuity editing, chiefly in the US, try here and here and here. More detailed treatments are in The Classical Hollywood Cinema, On the History of Film Style, and Figures Traced in Light: On Cinematic Staging.

I’m grateful as ever to Marguerite Engberg, Dan Nissen, Thomas Christensen, and Mikael Brae for their help in my research on Danish silent film.

PS 16 June: Jonathan Rosenbaum has republished on his site his detailed and engrossing 1985 study of Gertrud, which includes discussion of the play from which Dreyer adapted his film. Thanks to Jonathan for making his essay available.

The President (1920).