Archive for the 'National cinemas: Denmark' Category

Invasion of the Brainiacs II

DB here:

What gives movies the power to arouse emotions in audiences? How is it that films can convey abstract meanings, or trigger visceral responses? How is it that viewers can follow even fairly complex stories on the screen?

General questions like this fall into the domain of film theory. It’s an area of inquiry that divides people. Some filmmakers consider it beside the point, or simply an intellectual game, or a destructive urge to dissect what is best left mysterious. Many readers consider it academic bluffing, another proof of Shaw’s aphorism that all professions are conspiracies against the laity.

These complaints aren’t quite fair. Early film theorists like Hugo Münsterberg, Rudolf Arnheim, André Bazin, and Lev Kuleshov wrote clearly and often gracefully. Even Sergei Eisenstein, probably the most obscure of the major pre-1960 theorists, can be read with comparative ease. Moreover, generations of filmmakers have been influenced by these theorists; indeed, some of these writers, like Kuleshov and Eisenstein, were filmmakers themselves.

But those day are gone, someone may say. Does contemporary film theory, bred in the hothouse of universities and fertilized by High Theory in the humanities, have any relevance to filmmakers and ordinary viewers? I think that at least one theoretical trend does, if readers are willing to follow an argument pitched beyond comments on this or that movie.

That is, film theory isn’t film criticism. Its major aim is more general and systematic. A theoretical book or essay tries to answer a question about the nature, functions, and uses of cinema—perhaps not all cinema, but at least a large stretch of it, say documentary or mainstream fiction or animation or a national film output. Particular films come into the argument as examples or bodies of evidence for more general points.

In about three weeks, about fifty people will gather at the University of Copenhagen to do some film theory together. It’s the annual meeting of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image. I talked about the group last year (here and here) in the runup to our Madison event.

The sort of theorizing we’ll do, for all its variety, is in my view the most exciting and promising on the horizon just now. It’s also understandable by anyone interested in puzzles of cinematic expression, and it has powerful implications for creative media practice.

We’ll also be in Copenhagen for Midsummer Night, which is always pleasant. Go here for the lovely song that thousands of Danes will try to sing, despite terminal drunkenness. No real witches burned, however.

Concordance and convergence

But back to topic: Puzzles of cinematic expression, I said. What puzzles? Well, films are understood. Remarkably often, they achieve effects that their creators aimed for. Michael Moore gets his message across; Judd Apatow makes us laugh; a Hitchcock thriller keeps us in suspense. What enables movies to reliably achieve such regularity of response?

It’s not enough to say: Moore hammers home his points, Apatow creates funny situations, Hitchcock puts the woman in danger. Any useful explanation subsumes a single case to a more general law or tendency. So a worthwhile explanation for these cinematic experiences would appeal to more basic features of artworks, cultural activities, or our minds. We can pick up on Moore’s message because we know how to make inferences within certain contexts. We can laugh at a joke because we understand the tacit rules of humor. We recognize a suspenseful situation because… well, there are several suggestions.

This sort of question is largely overlooked by theorists of Cultural Studies, another area of contemporary media studies. They typically emphasize difference and divergence, highlighting the varying, even conflicting ways that audiences or critics interpret a film.

Studying how viewers appropriate a film differently is an important enterprise, but so is studying convergence. Arguably, studying convergence has priority, since the splits and variations often emerge against a background of common reactions. A libertarian can interpret Die Hard as a paean to individual initiative, while a neo-Marxist can interpret it as a skirmish in the class war, but both agree that John and Holly love each other, that her coworker is a weasel, and that in the end John McClane’s defeat of Hans Gruber counts as worthwhile. Both viewers may feel a surge of satisfaction when McClane, told by a terrorist he should have shot sooner, blasts the man and adds, “Thanks for the advice.” What enables two ideologically opposed viewers to agree on so much?

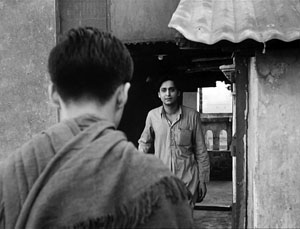

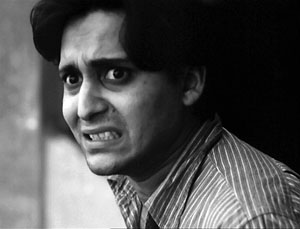

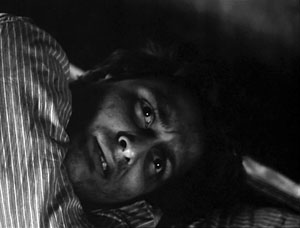

Films aren’t just understood in common; they arouse remarkably similar emotions across cultures. This is a truism, but it’s been too often sidestepped by post-1960 film theory. Who, watching The World of Apu, doesn’t feel sympathy and pity for the hero when he learns of the sudden death of his beloved wife? Perhaps we even register a measure of his despair in the face of this brutal turn of events.

We can follow a suite of emotions flitting across Apu’s face. I doubt that words are adequate to capture them.

Are these facial expressions signs that we read, like the instructions printed on a prescription bottle? Surely something deeper is involved in responding to them—for want of a better word, fellow-feeling. Indians’ marriage customs and attitudes toward death may be quite different from those of viewers in other countries, but that fact doesn’t suppress a burst of spontaneous sympathy toward the film’s hero. We are different, but we also share a lot.

The puzzle of convergence was put on the agenda quite explicitly by theorists of semiotics. Back in the 1960s, they argued that film consisted of more or less arbitrary signs and codes. Christian Metz, the most prominent semiotician, was partly concerned with how codes are “read” in concert by many viewers. Today, I suppose, most proponents of Cultural Studies subscribe to some version of the codes idea, but now the concept is used to emphasize incompatibilities. So many codes are in play, each one inflected by aspects of identity (gender, race, class, ethnicity, etc.), that commonality of response is rare or not worth examining.

A complete theoretical account, if we ever have one, would presumably have to reckon with both differences and regularities. The dynamic of convergence and divergence is a central part of one arena of film studies that has, for better or worse, been called cognitivism.

Sampling

Gathering for Uri Hasson‘s keynote lecture, SCSMI 2008.

The cognitive approach to media remains a pretty broad one, and the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image hosts a plurality of approaches at its annual meetings. SCSMI has become home to media aesthetes, empirical researchers, and philosophers in the analytic tradition who are interested in interrogating the concepts used by the other two groups. Last year’s gathering, at our campus here in Madison, created a lively dialogue among these interests.

For instance, some of us Film Studies geeks wonder why people so consistently ignore mismatched cuts. Dan Levin’s ingenious experiments on “change blindness” provide a hilarious rejoinder. In one study conducted with Dan Simons, a stooge asks directions of an innocent passerby. As they’re talking, a pair of bravos carry a plank between them, and another confederate is substituted for the first one.

You guessed it. Most subjects don’t notice that the person they’re talking to has changed into somebody else! So how can we worry about mismatched details in cuts? Actually, Dan’s research isn’t just deflationary. It helps spell out particular conditions under which change blindness can occur.

Another stimulating talk was offered by Jason Mittell. He asked how long-running prime-time TV serials can solve the problem of memory. In this week’s episode what strategies are available to recall the most relevant action of earlier episodes? How can previous action be presented without boring faithful fans? Jason, who has a new book on American TV and culture out this spring, went beyond describing the strategies. He suggested how they can become a new source of formal innovation, as in the Death of the Week in Six Feet Under.

Sermin Ildirar of Istanbul University presented the results of a study on adults living in a village in South Turkey. These viewers were older, ca. 50-75, and—here’s the interesting part—had never seen films or TV shows. To what extent would they understand “film grammar,” the conventions of continuity editing and point-of-view, that people with greater media experience grasp intuitively? To facilitate comprehension, the researchers made film clips featuring familiar surroundings.

The results were intriguingly mixed. Some techniques, such as shots that overlapped space, were understood as presenting coherent locales. But most viewers didn’t grasp shot/ reverse-shot combinations as a social exchange. They simply saw the person in each shot as an isolated figure.

The discussion, as you may expect, was lively, concerning the extent to which a story situation had been present, the need to cue a conversation, and the like. I found it a sharp, provocative piece of research. Stephan Schwan, who worked with Sermin and Markus Huff, has become a central figure studying how the basic conventions of cutting and framing might be built up on the basis of real-world knowledge, and both he and Sermin are back at SCSMI this year.

Stephan Schwan, Thomas Schick, Markus Huff, and Sermin Ildirar, with Johannes Riis in the background; SCSMI 2008.

There were plenty of other stimulating papers: Tim Smith’s usual enlightening work on points of attention within the frame, Johannes Riis on agency and characterization, Paisley Livingston on what can count as fictional in a film, Patrick Keating on implications for emotion of alternative theories of screenplay structure, Margarethe Bruun Vaage on fiction and empathy, and on and on.

One of the best things about this gathering was that the ideas were sharply defined and presented in vivid, concrete prose. I can’t imagine that ordinary film fans wouldn’t have found something to enjoy, and of course many of these matters lie at the heart of what filmmakers are trying to achieve. Indeed, some filmmakers regularly give papers at our conventions. The much-sought link between theory and practice is being made, again and again, in the arena of the SCSMI.

Last year I came to believe that this research program was hitting its stride. My hunch is confirmed by this year’s gathering in Copenhagen. The department of media studies there has long been a leader in this realm. You can download a Word version of the schedule here.

Lest you think that the conference participants don’t talk much about particular movies, I should add that there’s one film we’ll definitely be talking about this time around. Our Copenhagen hosts have arranged for a screening of von Trier’s Antichrist.

Next time: Going deeper into cognitivism, and three recent explorations.

Malcolm Turvey makes a point to Trevor Ponech and Richard Allen, SCSMI 2008.

Kristin and I have talked about pictorial universals elsewhere on this site. See her blog entry on eyeline matching in ancient Egyptian art, and my comments on “representational relativism” here.

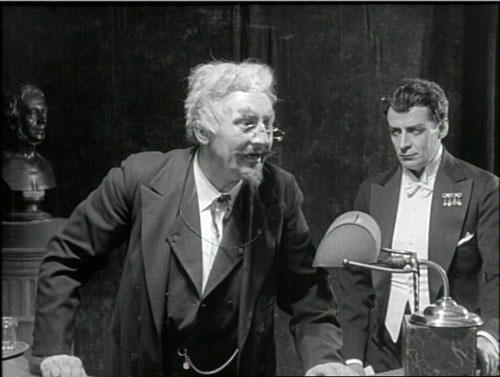

Images at the top of this entry are taken from the Danish film Himmelskibet (The Space Ship, aka A Trip to Mars, 1918).

Danes not dour, can do drollery

DB here:

With our new edition of Film History: An Introduction in the final phases of production, we’re pretty busy. But I still hope to post an entry on Ashes of Time Redux later this week. I’ve got some pretty pictures, at least.

In the meantime, if you know the films of Carl Dreyer, you must look at this mini-movie. It was created by Henrik Fuglsang, the Danish Film Institute archivist at work on a massive website devoted to Dreyer.

Have patience and let it load fully; the holiday cheer is worth it. Thanks to Casper Tybjerg for sending me the link.

The Danes once more

After the Wedding.

Can’t stop bloggin’ about those blonde, smørrebrød-loving Nordics. Why?

Well, there’s news. First, two Danish films have been nominated for Academy Awards. Susanne Bier’s After the Wedding (I talk a bit about it here) is up for best foreign-language film, and Søren Pilmark’s Helmer and Son is nominated for best short. You can read more at the Danish Film Institute site, and stock up on Carlsberg or Tuborg to cheer them on Oscar night.

Second, the new English-language issue of the Danish Film Institute’s magazine Film is online here, as a pdf. It’s a must for von Trier fanatics, with lots on The Boss of It All. I also have an essay in it (pp. 16-19).

Third, Thomas Christensen, a Boss of It All at the Danish Film Archive and a graduate of our UW film program, alerted me to YouTube video from a Danish band, Phonovectra. It swipes—sorry, appropriates—Dreyer’s classic short film They Caught the Ferry.

My Danish December

Easy Skanking (aka Fidibus).

DB here:

I’d intended to post this at the end of the year, but I fell behind. So in place of the New Year’s entry Kristin and I had hoped to write, we’ll just say: Best wishes for 2007!

And now the blog….

I haven’t bothered to draw up a list of best films of 2006, for lots of reasons. Some acute objections to the very idea of best-films lists are aptly summarized by Andy Horbal, and I find them convincing. But there have been practical concerns too.

My December movie-watching was dominated by 2004-2006 Danish films, in preparation for an essay. I think I couldn’t have spent my time better. Instead of being disappointed with critics’ official hits from the US, I was repeatedly excited by ingenious, moving, and enjoyable films….most of which I wouldn’t have known about otherwise.

First, some background.

Historically, it seems, the three greatest national cinemas are those of the US, Japan, and France. Their pervasive influence and their accomplishments in film art, film industry, and film culture make them consistently important in every era, from 1895 to the present.

But a lot of other national cinemas are important too, and I confess a fondness for those less salient ones, what Mette Hjort calls, without disparagement, cinemas of small nations. It’s partly because my academic life has been bound up with not only the Big 3 but a littler 3: Belgium, Hong Kong, and Denmark.

Denmark was the first foreign country I ever visited; I went there in 1970, just before starting graduate school, to do research on Carl Dreyer. I was received so hospitably by Ib Monty, Karen Jones, Marguerite Engberg, and others at the Danish Film Archive, that I came to believe that I could continue to do academic work on cinema.

Over the last 36 years, I’ve felt a kinship with Danish film culture. It has admirable directors like Dreyer and Benjamin Christensen, of course, but also without a lot of fuss the Danes keenly support artistic cinema in a commercial context. I’ve come to respect their open, unpretentious approach to filmmaking and film viewing. I’ve also made many strong friendships with Danish archivists and professors.

The Danish Film Institute not only helps fund most of the 15-20 titles theatrically released every year. It also proselytizes very actively for those films, helping them get festival slots and theatrical releases overseas.(Several Danish items will be screened at Sundance this month.)

The DFI’s job has gotten easier since the arrival of Dogme 95, which galvanized filmmakers around the world and made Danish film the flagship of Scandinavian cinema. Here is Norwegian director Aksel Hennie: “The effect of Dogme on my generation has been immense. More than anything else, it is the Dogme attitude, the ‘anybody can make movies’ idea. As a first time director with no formal training from a small European country, that was very inspiring.”

In 2002, Vicki Synnott of the DFI asked me to write an essay about post-Dogme Danish films for their publication Film, which appears in English in spring, summer, and fall. I reviewed about thirty titles, only a few of which I’d already seen. The result, “A Strong Sense of Narrative Desire,” can be downloaded here.

In 2005, Vicki asked me for a more up-to-date piece, and she sent me another passel of films to watch. Hence my December movie marathon, and the essay, which I’ve just submitted. After polishing, it will be published in print and will be available online.

I thought that a good way to start the new year would be to talk about the most intriguing and enjoyable films I saw. Most are little-known outside the festival circuit, and very few are as yet available on DVD. But all are well worth your time. So call it my Best Danish Films I Saw at the End of 2006 list.

Thrillers

The King’s Game (2005) offers journalistic-political intrigue in the vein of All the President’s Men. Efficiently directed and plotted, with some earned surprises, it also features those doyens of Danish acting, Anders W. Berthelsen (Mifune) and Søren Pilmark.

Murk (2005) shows off again the estimable talents of screenwriter (sometime director) Anders Thomas Jensen. A little implausible in the third act, but excellent suspense and fine performances from the ubiquitous Nicolas Bro and Nicolaj Lie Kaas.

Flies on the Wall (2005): Another political thriller, this one for the digital age. A documentary filmmaker (Trine Dyrholm, another fixture of modern Danish film) is commissioned to make a film promoting a political party. She finds a scandal instead. Director Åke Sandgren creates a dizzying montage of footage from the hidden cameras she plants among the offices and in her motel. At a certain point, though, we realize that some of the footage comes from cameras spying on her.

I plan to write more about this rather dazzling movie in another essay.

Ambulance (2005): The idea is worthy of Larry Cohen. A botched bank robbery forces the thieves to hijack an ambulance to make their getaway…with an attendant and a critically ill patient still inside. Unfolding in more or less real duration, the film barrels along breathlessly but still pauses for moments of character revelation and disputes about moral choices.

Pusher III (2005): Even grimmer than the first two installments, but completely gripping in its portrayal of a man whom we should consider utterly degenerate. Nicolas Winding Refn makes the milieu of The Departed look like a ten-year-old’s birthday party. There’s also an intriguing documentary, Gambler (2006) about the financial pressures that forced Refn to make the two final Pusher films.

Comedies

Clash of Egos (2006): A high-concept satire of the film industry by, once more, Anders Thomas Jensen. Through a legal settlement, working-class Tonny gets a chance to oversee a pretentious movie director’s next project.

Lotto (2006): Danish comedies often have a moral issue at their center, one that’s usually more subtly developed than the morality of Hollywood films. Here the situation is: If you and your workmates pooled to buy a lottery ticket and it won….should you tell them? Another fine Pilmark performance, this time in mild-mannered mode.

Easy Skanking (2006; illustration up top). Originally titled Fidibus, which refers to somebody serving as a gofer for a drug dealer. This is a lively venture into Pulp Fiction and Trainspotting territory, but with a sweeter tone and a happy ending. Rudy Køhnke, Denmark’s answer to the young George Clooney, works for the fearsome pusher Paten, but falls in love with Paten’s mistress. You can check out trailers here and here.

Adam’s Apples (2004): A little older, but I had to include it just because it’s one of my favorite films of recent years. Written and directed by Jensen, it tells of a daffily upbeat priest’s efforts to reform convicts, including the skinhead Adam of the title. Tough and warm-hearted at the same time. Mads Mikkelsen, now famous thanks to Casino Royale, plays the priest, with Ulrich Thomsen of Flickering Lights as the edgy miscreant.

Dramas/ Melodramas

Susanne Bier’s After the Wedding (script by Jensen) has already received plenty of praise. It’s another poised, sensitive study of love and family in the vein of Open Hearts (2002), but with a more socially engaged dimension. The protagonist, played by Mikkelsen, has transformed himself from a dissolute vagabond into a worker in an orphanage in India, but his past returns to threaten his redemption. If American critics had seen this film, or if it had been distributed in the US, it would have appeared on many ten-best lists.

1:1: Annette K. Olesen’s tale of the racial tensions surrounding an attack on a teenager. As often in Danish films, psychological drama is balanced by a consideration of social context. The opening credits play out against blueprints and documentary footage detailing the construction of the housing development that forms the center of the action.

Prague (2006): Christoffer, a hard-working businessman, comes to Prague to claim the body of his father, whom he never really knew. His stay leads to a crisis in his past, as he learns his father’s secrets, and one in his present, as he and his wife face the breakdown of their marriage. A severe, engaging film with some of the tang of mid-period Antonioni, starring Mikkelson and Stine Stengade.

A Soap (2006): Pernille Fischer Christensen’s debut has already racked up festival prizes. The action unfolds wholly in an apartment building, where Charlotte (Trine Dyrholm, another fixture of modern Danish film) and the transvestite Veronica (David Dencik) strike up a relationship. Almodovarish, but more subdued (Danes aren’t Spaniards, after all).

How We Get Rid of the Others (2007): In the near future, Copenhagen creates laws that eliminate all citizens who take more from society than they give. A dark, 1984ish vision that satirizes how communitarian social policies can turn tyrannical.

Unclassifiable

The Boss of It All (2006): I’ve already discussed this here, and have recently added a couple of updates. Surely one of the most artistically daring films of the year. Funny too.

Day and Night

Bang Bang Orangutang (2005): Simon Staho is virtually unknown in the US, but his previous feature Day and Night (2004) takes minimalist cinema in a new direction. Perhaps inspired by Kiarostami’s Ten (2002), Staho pushes the camera/car conceit toward more classical staging and shooting. His followup, Bang Bang, opens up a bit more–now the camera occasionally leaves the car–but Staho goes on to create new formal constraints. The story? A heartless businessman sinks to the bottom of society and out of touch with reality.

Offscreen (2006): After the Neoromanticism of Reconstruction (2003) and Allegro (2005), Boe, in collaboration with Nicolas Bro, creates a more-or-less fictitious diary film. Bro becomes obsessed with recording his life on video, and that leads him to horrific violence. An absorbing exercise in first-person cinema, with viewpoints multiplied (as in Flies on the Wall) thanks to mini-cams.

I hope to write more on these formally adventurous films. (I did: here and here, both for the DFI.)

Watching these films over several weeks, I was even more convinced that today’s cinema encompasses far more than even the most pluralistic ten-best lists can allow. Lists are helpful for some purposes, but our time is better spent seeking out unusual movies, listed or unlisted.