Archive for the 'National cinemas: Denmark' Category

An appetite for artifice

Offscreen (Christoffer Boe)

DB here (no, not above):

Catching up with several of the fall’s films, I was struck by how often they played quite self-consciously with the overall shape of their plots. Here are some examples.

Network narratives. This is the label I applied in The Way Hollywood Tells It to those films highlighting several protagonists inhabiting distinct, but intermingling, story lines. In Poetics of Cinema, I have an essay examining the conventions of this format. Several films I saw this fall continued this tradition.

*Bobby used the familiar device of gathering everyone in a single spot–a hotel–within a short time frame and interweaving personal stories with a fateful climax. I thought the film was fairly clumsy, but I was still moved. In 1964 I filmed RFK when he stumped our town for the presidential nomination, and in college, though leaning toward Gene McCarthy I thought Bobby was the only candidate who could beat the Republicans. “Dump the Hump!” (Hubert Humphrey) was the rallying cry.) His assassination, during the same year Martin Luther King was killed, was very traumatic to young idealists. Estevez’s film becomes most powerful, I think, by simply replaying footage and speeches, reminding us that there was once a rich politician who talked incessantly about helping the poor. Just as Stone’s JFK positioned Jack as the man who could have averted the Vietnam War, Bobby makes RFK the anti-Bush.

*Fast Food Nation was for me a more satisfying use of the network narrative format. Here the time scheme is more diffuse because Linklater is tracing a large-scale process, the burger from the hoof to the Happy Meal. By starting with the middle-management character (Greg Kinnear) and then easing us into the harsh working life facing Mexican illegals, the film builds sympathy for the immigrants. Gradually, the illegals’ stories take over, and the social conscience of one of the burger chain’s teenage workers is ignited.

The plotting makes some thoughtful moves. A more literal approach would have shown us the meat-processing plant’s killing floor early, as part of the step-by-step process. But here the shocking material isn’t presented until the very climax of the film, as the fate to which the immigrant working woman must submit. Likewise, the film drops the Kinnear character about halfway through, a ploy that conceals from us how he’ll act on his new knowledge. Will he blow the whistle on the plant, and endanger his job? A European film might have left his whole line of action open, but Linklater adheres to the tendency of American films to resolve a plotline one way or another. He does it, however, in an epilogue which leaves us with a sharpened sense of the acute problems of the system.

*The Uchoten Hotel (aka Suite Dreams, Japan, 2006). In the vein of Tampopo and Shall We Dance?, Mitani Koki offers gentle humor mixed with satiric social observation. Confusion reigns at the Avanti Hotel on New Year’s Eve, as a philandering professor, a corrupt Senator, low-end showbiz types, and the hotel staff become embroiled in one another’s lives. Lively long takes display subtle staging, and there’s a ventriloquist’s duck. A tribute to Grand Hotel, Billy Wilder, and Jacques Tati, this good-hearted survey of human aspirations was the most uncynical movie I saw all year.

Many critics seem to feel that the network format is tired out. At indieWire, Nick Schager calls for “a moratorium on second-rate Nashville-style ensemble pieces that seem increasingly to be the province of every Tom, Dick, and Emilio.” The key words are “second-rate”: Like any storytelling pattern, the network option can be used well or badly. Linklater and Mitani use it with flair.

The point I’d stress is that although the network model can claim to be a realistic device (in our world, our projects commingle), it’s almost always presented through a series of conventions–traffic accidents, people brushing past each other, narration that holds back information about the characters’ relationships, and so on. We recognize these as part of the artifice in this tradition of storytelling.

Broken Timelines. During his DVD commentary for Basic, John McTiernan uses this phrase to explain the film’s flashbacks and replays. In the terms we use in Film Art, the linear story action is scrambled or rearranged in the plot that that the film presents to us.

Screenwriters used to urge novices to avoid breaking up the timeline, but in the 1940s through the mid-1950s, films began to play around with story order. Citizen Kane (1941) probably encouraged the flashback form, as did film noir’s emphasis on mystery and crime detection. Siodmak’s fine The Killers offers a prototype. (I discuss its plot maneuvers in Narration in the Fiction Film.)

We don’t lack for flashbacks in contemporary films, but things are getting complicated. Today a film may open with a quite mystifying sequence, before backtracking to acquaint us with the situation. In itself, this isn’t very unusual, since flashback-based films have often opened at a point of crisis and then taken us back to the beginning of the action. The Big Clock and Written on the Wind are instances. The new wrinkle is to actually replay the opening situation or just the images from it in a new context.

*The Fountain by Darren Aronofsky offers one example. Using three time layers, it can keep replaying the opening portions in ways that recontextualize the material we saw at first. In its out-of-this-world realm, as well as its suggestion that the story is in some sense being written as we see it, it reminded me of Slaughterhouse-Five (1972)–another indication that these innovations aren’t brand new.

*Another instance: The opening image of Christoffer Boe’s Offscreen (2006), with a bloody Nicolas Bro in close-up advancing to the camera, gets explained only at the grisly climax.

*The recontextualizing replay isn’t an avant-garde device. Tony Scott’s well-done thriller Déjà Vu uses it in the context of a time-travel plot. It replays the opening sequence in a way that suggests both a branching or alternative future and a deeper understanding of what we saw initially. A similar pattern is found in Flags of Our Fathers, in which we reinterpret the opening differently now that we know the characters more fully. I suppose that Pulp Fiction‘s opening became a powerful influence on this formal choice.

When an action is replayed, it can be shown from different characters’ perspectives. Again, this was explored a lot in the 1940s, as in Mildred Pierce (a replay of the opening) and Crossfire (a replay of the crucial incident). The device is on display in The Killing and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance as well. Kurosawa’s Rashomon made the technique more ambiguous, by not confirming which version of events is accurate. The same idea guides the money exchange in Tarantino’s Jackie Brown, which we discuss in the new edition of Film Art.

*The broken timeline of Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada uses multiple points of attachment mildly, in the murder scene. The replays are more significant and fragmentary in The Prestige. More films in this vein are in preparation, including Vantage Point, which shows an assassination attempt on a US president as seen from five characters’ points of view, “unfolding in 15-minute increments.”

Companion films. Back in the 1960s, Fox announced that it wanted to make Tora! Tora! Tora! with two directors, one Japanese and one American. My friends and I indulged in a game: Whom should they pick? (I favored Ozu and Samuel Fuller.) As you probably know, Kurosawa’s collaboration came to naught (though he did shoot some footage, discussed by Richard Fleischer in his book and his DVD commentary on the film). Fukasaku Kinji and evidently some other directors contributed to the Japan-based footage.

Now, instead of one film with two directors, Clint Eastwood gave us two complementary films from a single hand. I haven’t yet seen Letters from Iwo Jima, but the very idea of showing the same battle from opposite sides in two movies acknowledges a level of artifice.

The French got here first, I think. Marguerite Duras made a companion film to her mesmerizing India Song (on right) called Son nom de Venise dans Calcutta desert. Son nom had exactly the same soundtrack as India Song but a wholly different image track–only landscapes around the site of action, empty (as I recall) of all human presence. A comparable instance is the alternate-worlds pairing by Alain Resnais, Smoking/ No Smoking, adapted from a cylce of Alan Ayckbourn plays.

The French got here first, I think. Marguerite Duras made a companion film to her mesmerizing India Song (on right) called Son nom de Venise dans Calcutta desert. Son nom had exactly the same soundtrack as India Song but a wholly different image track–only landscapes around the site of action, empty (as I recall) of all human presence. A comparable instance is the alternate-worlds pairing by Alain Resnais, Smoking/ No Smoking, adapted from a cylce of Alan Ayckbourn plays.

The companion-film concept seems to be expanding. Red Road, directed by Andrea Arnold, is launching a series of films to based in Scotland and all featuring the same group of characters, but filmed by different directors. The characters are conceived by filmmakers Lone Scherfig (Wilbur Wants to Kill Himself) and Anders Thomas Jensen (Brothers). In a way, a sort of episodic-television idea applied to feature films.

What’s behind this? Why are today’s movies using such self-conscious artifice in their plotting? Is form the new content, the way gray is the new black?

Complex storytelling can be found in a lot of other media today. It’s common to point to Hill Street Blues and later TV shows as reinforcing tendencies toward network narratives in film. Jason Mittell discusses the tendency in Velvet Light Trap no. 58. His article “Narrative Complexity in Contemporary American Television” (available here), makes the case that shows like 24, Arrested Development, Buffy, Malcolm in the Middle, and so on have offered viewers ways “to be actively engaged in the story and successfully surprised through the storytelling’s manipulations”–a good way to describe some of the strategies I’ve been sketching.

In graphic novels and comic art we’re seeing the same tendencies. Daniel Clowes and Chris Ware manipulate time and space in virtuoso ways, as does the highly formalized movement known as OuBaPo. You can check out an American version of OuBaPo in Matt Madden’s 99 Ways to Tell a Story.

In graphic novels and comic art we’re seeing the same tendencies. Daniel Clowes and Chris Ware manipulate time and space in virtuoso ways, as does the highly formalized movement known as OuBaPo. You can check out an American version of OuBaPo in Matt Madden’s 99 Ways to Tell a Story.

In Everything Bad Is Good for You, Steven Johnson argues that people are just getting smarter, and so popular culture is pitched at a more sophisticated level. But quite complex artifice can be found in mass media of earlier eras. As I mention in The Way, we can find backward-told stories in popular fiction long before Memento, and Grand Hotel is an early prototype of the network narrative. Our ancestors weren’t necessarily dumber than we are, and popular art has long harbored experimental impulses.

I’d hypothesize some other causes. Regardless of IQ, more members of the audience have been to college today than in early eras. More of the creators have studied modern art and literature and are ready to borrow experimental devices they’ve encountered in other media. This process has a familiar ring. American filmmaking has often renewed itself by absorbing all manner of experiment, from German Expressionism (for 1930s horror films) to serial music (for 1950s psychological dramas). Usually, I feel compelled to add, the experimental devices are absorbed into existing forms, like classical script structure, genres, or stylistic principles.

I suspect as well that the new genre hierarchy that emerged in the last couple of decades cranked up the artifice level. The rise of science fiction, mystery, fantasy, horror, and comic-book movies probably encouraged clever juggling with story order, point of view, and states of knowledge. So did the rise of indie cinema, which needs narrative innovation to set itself apart from the mainstream. Again, Pulp Fiction fuses the two strands: an indie neo-noir that attracted attention through its bold manipulation of story/ plot relations.

At the same time, filmmakers in other countries have been eager to push the boundaries. Many of the broken-timeline devices have their sources in art cinema of the 1950s and 1960s. Younger European directors like Boe and Tom Tykwer (Run Lola Run) have revived this adventurous attitude toward storytelling, putting them somewhat in sync with American directors. Asian experimentalists like Wong Kar-wai and Hou Hsiao-hsien continue to exercise a comparable influence.

We need to think more about where this impulse toward innovation comes from and how it shows itself, but it seems likely that the flourishing trade in self-conscious storytelling will be with us for some time yet. Hollywood cinema has long been self-consciously, almost fussily formal, and it has a vast appetite for artifice.

Another pebble in your shoe

DB here:

“Life is a Dogme film. It’s hard to hear, but the words are still important.” This is one of the many in-jokes peppering Lars von Trier’s The Boss of It All, his newest feature. I watched it while preparing an essay for the Danish Film Institute, which superbly promotes Danish cinema to the world. But I wasn’t ready for what I saw.

It’s a comedy, of course, with a classic bait-and-switch premise. For shadowy motives, a corporate lawyer entices an idle actor to pretend to be the superboss whom the IT staff has never met. Unfortunately, through emails to the staff, the lawyer has constructed a persona for the boss–in fact, several personae, a different one for every worker. Our actor must play many parts before finally, in a series of reversals, he gets to “find” the real character.

In tone, the film is as mixed as most von Trier works, hovering between sympathy for idealistic underdogs and a sour realization that they will always be victims. It reminded me somewhat of Kaurismaki and the Fassbinder of Fox and His Friends. But the film is a breezy piece of work; nothing really serious faces his innocent here. There’s a lively satire of the corporate world, mocking management catchphrases du jour (not outsourcing, we’re told, but offshoring) and touchy-feely hugging. The hostile incomprehension between Denmark and Iceland provides some good gags too. Von Trier also pokes fun at actors, perhaps invoking his well-publicized feuding with divas like Kidman and Björk. Our hero/loser Kristoffer is a sort of Method man, but he learns that he gets the best results through shameless sentiment.

Here the words are important–it’s a very talky movie–but so are the pictures. Shot in 16mm in available light, The Boss breaks with von Trier’s normal commitment to handheld camerawork. Except for some interpolated crane shots outside the office building, the camera never moves, not even panning. But the image is constantly being refreshed through incessant cutting (there are over 1500 shots). The film boasts more jump cuts than Breathless or Matchstick Men, and each one creates a bump. There’s very little sound overlap between shots–the ambient noise usually drops out for a fraction of a second–and there are often visual mismatches, so (as in The Idiots), nearly every cut feels like an ellipsis. A film, von Trier has said, should be as irritating as a pebble in your shoe, and his abrasive tempo gives his comedy an anxious edge.

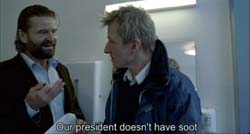

Then there are the very peculiar framings. Here’s a string of three brief shots from the first scene, with continuous dialogue (in gappy duration). The lawyer is trying to persuade the actor to perform as the boss.

(Yes, these are three separate shots, not three stages of one wobbly shot.)

These cuts break the so-called 30-degree rule, which mandates that if you’re cutting to different angles on the same subject, your second angle should vary by at least 30 degrees from the first. In addition, the later off-center compositions seem gratuitous; why not just sustain the first shot, since the next two hardly vary from it? Sometimes you get results like this.

It turns out that there is method to the madness, although the method, granted, is a bit mad. You can read about Automavision here, if you want to know in advance why the movie looks this way. But if you want to be as startled as I was, refrain. Let’s just say that von Trier’s famous 100-camera technique of Dancer in the Dark has been repurposed in a pretty unexpected way. And don’t believe what he says about surrendering to chance; the cuts are often very careful.

Whether you do your homework in advance or not, you’ll probably enjoy The Boss of It All. After my criticisms of editing in The Departed (which made me seem to be raining on the Scorsese parade) and my comments about classical principles of coverage, I’m happy to report on a film which offers something new and strange. The vivacious Danish film culture makes a space for von Trier to set up creative obstructions, for both himself and his viewers.

Postscript: Since I wrote this, von Trier announced that he’s added more tricks to his bag. Turns out that The Boss of It All employs Lookey, a game that challenges the viewers to spot objects that don’t belong in a scene. “For the casual observer it’s just a glitch or mistake,” he says, “but for the initiated it’s a riddle to be solved.” The purpose is to keep viewers alert and active. Film’s great flaw, he claims, is that “it’s a one-way medium with a passive audience.” Lookey, however whimsical, fits well with the agitating effects of the cut and sound dropouts.

The first viewer in Denmark to identify all the Lookeys correctly wins a cash prize and a chance to be an extra in von Trier’s next film.

PPS: Thanks to Vicki Synott of the Danish Film Institute.

PPPS 28 December: I just discovered a frisky website devoted to Nordic filmmaking, where Mirja Julia Minjares has gathered some interesting quotes from von Trier and his sound recordist Ad Stoop. Von Trier says that the computer program also selects for sound gain and filter. Adds Stoop: “When a computer program chooses the settings for the sound and cinematography between each shot, every edit gets underlined in the finished film.”

PPPS 31 December: Check perceptual psychologist Tim Smith’s blog for more insights into von Trier’s games with continuity editing.

–dB

Great Danes in the morning

This morning I received my author’s copies of a superb book published by the Danish Film Institute, 100 Years of Nordisk Film. Nordisk was one of the world’s top producing and distributing companies in the 1900s and 1910s, and it continues today. This volume, edited by Lispeth Richter Larsen and Dan Nissen, is now the fullest account in English of this extraordinary firm.

There are essays by top scholars like Isak Thorsen, Marguerite Engberg, Stephan Michael Schroder, Niels Jorgen Dinnesen, Edvin Kau, Thomas Christensen, Casper Tybjerg, Ib Bondebjerg, and Peter Schelpern, and the illustrations are eye-popping. I contribute an essay on the aesthetics of Nordisk’s 1910s films, and my stills came out beautifully.

Many of the silent films discussed are available on DVD from the Institute, and they are extraordinary. If you want a sample, try the Asta Nielsen or Benjamin Christensen collection. These are amazing movies, and the Christensens offer remarkably inventive uses of cutting, lighting, and camera movement–very unusual for their day.

I don’t yet find a source for ordering the book online, but it will probably be available soon from the Institute’s bookstore. Danish cinema is one of the most exciting national cinemas in Europe right now; for coverage, have a look at their new homepage.

Addendum to an earlier post: Industry sage and entertaining skeptic David Poland of The Hot Button calls foul on Gladwell’s New Yorker piece on the Epagogix software–you know, the one purporting to predict hit movies. Thanks to Sean Weitner of Flak Magazine (itself highly recommended).