Archive for the 'National cinemas: Eastern Europe' Category

Wisconsin Film Festival 2021: Here and there

Calamity: A Childhood of Martha Jane Cannary (2020).

Kristin here:

Last time I wrote about three Middle Eastern films. Now I’m writing about three films that are all over the map and presented in no particular order. Such are the pleasures of film festivals, including the Wisconsin Film Festival, which wraps up Thursday, May 20. At 11:59 pm, all the films will be taken offline and we can all look forward to next year’s festival–with luck, back on the big screens of Madison.

The Village House (2019, India)

Achal Mishra’s first feature is a slow, entrancing, nostalgic love letter to his parents’ sprawling villa. The film is broken into three parts, set in 1998, 2010, and 2019. There is no real storyline, apart from the inevitable dissolution of the large extended family that inhabits the house in the first part. There is little dramatic conflict, either. Instead Mishra films everyday activities: men playing card games and teasing each other, women perpetually cooking or caring for a new baby, boys lured away from a game of hide-and-seek to go pick mangoes. It’s the sort of ideal of capturing the quiet poetry of life that the Neorealists never quite achieved.

Mishra admits to being strongly influenced by Ozu and Hou Hsiao-hsien (in his podcast discussion with programmer Jim Healy), and it shows, though there is never overt imitation. The camera never moves, and there are nearly as many shots of empty locales as those with people present. Idle conversations are lingered over in long takes.

Mishra also mentions Wes Anderson, and there certainly are quite a few planimetric shots in the film (above). The three time periods are also set off from each other by different aspect ratios: nearly square for 1998 (also above), widescreen for 2010 (second frame below), and full anamorphic widescreen for 2019. The purpose of these contrasting framings are quite different from Anderson’s in The Grand Budapest Hotel, where the the shots imitate the film ratios of the historic periods that the story moves among.

The narrow rectangle of the 1998 scenes suggests the crowded bustle of the house. From side to side it’s full of food (yet again above) and people in many shots.

We don’t get much of a sense of the geography of the house, just that it’s full of rooms where ordinary things are going on. We also probably have some trouble figuring out who all the characters are (especially since the jumps forward in time have different people playing them). Still, there’s always something to look at and listen to.

By 2010, the house is aging and the village offers fewer opportunities. One of the sons can’t find a job and wants to sell a plot of land to get money to start a pharmacy. Perhaps the biggest drama in the film comes when an older man tries to talk him out of it. The mundane is still present, though, as one brief scene consists of one character telling another, “The toilet door needs repair, and the kitchen door is jammed.” This casual-sounded remark turns out to be a hint of things to come.

The village still offers traditional festivals, but the sense of community has become less idyllic.

Slowly, however, the family members leave, culminating in the wordless departure of the old grandmother at the end of the 2010 scene.

The final third opens into full widescreen, with more extensive views of the house, empty or nearly so. These don’t give us a much better sense of its geography, but definitely a sense of its desertion by all by an elderly caretaker and some intrusive goats.

The renovation of the house starts at this point, though we are not shown what it eventually came to look like.

The Village House is available to stream anywhere in the USA until the end of the festival.

Calamity: A Childhood of Martha Jane Cannary (2020, France)

Rémi Chayé’s film won the Cristal for a Feature Film (top feature) at the Annecy International Animation Film Festival for 2020, and it’s easy to see why. Done with hand-drawn images, it has a look all its own. The unblended areas of color create a simple but beautiful set of images (top and above).

The story is aimed primarily at children. It tells an imagined tale of the childhood of Calamity Jane (about which very little biographical information survives), who gains skills and self-confidence when her widowed father is injured during a wagon-train journey west. It’s a woke story for the modern age, as young Marsha endures bullying from the guide’s son and ridicule over her tomboyish clothes and behavior.

Some of her achievements are bit over-the-top, but there’s a tall-tale aspect to the narrative–as is emphasized by scenes in which characters boast of their own acts of bravery around the campfire. It’s entertaining enough, but adults will probably be more impressed by the visuals.

The film is in French with subtitles. I would say that any child not old enough to read subtitles would probably be scared by some of the bullying, violence, and near disasters that occur, though older kids could probably handle them pretty well, given that all ends happily.

Calamity is also available nationwide for the duration of the festival.

Fear (2020, Bulgaria)

I went into Ivaylo Hristov’s Fear knowing little about it except that it deals with a middle-aged Bulgarian widow who captures a lone African refugee. At first she is afraid and suspicious of him but gradually, of course, comes to feel sympathy and even friendship for him. Something of a cliché in this day and age, I thought.

It turned out to be far more complex than a warmhearted tale of a bigot changing her ways. For a start, it’s a throwback to the more cynical of the black comedies of the Czech New Wave, with a similar kind of humor directed against the local authorities, primarily the border patrol and the mayor. They are required by law to feed and house refugees coming across the border before sending them onto the next facility. Most people crossing the Bulgarian border are on their way to Germany. Bamba, whose family have been killed in an unnamed African country, is going there, as are a small, hapless group of Afghans rounded up by the border patrol.

That patrol is mocked, as in the absurd line-up by height in the image at the bottom. They are completely unprepared to accommodate the Afghans, herding them first into the closed local school and later into the open-sided apartments in an abandoned construction site. These are not, however, the bumbling but largely harmless officers of The Firemen’s Ball. Underneath the gags, they are racist, ignorant bullies, roughing up the completely passive Afghans during the round-up. A chillingly funny interview of the officer in charge by a local TV reporter goes on in the foreground, with her repeatedly asking if the Afghans are armed and violent. When he replies that he’s never caught one with weapons or met any resistance, she begs for an anecdote of a time when the patrol was threatened. Again he says there wasn’t one, and she turns to the camera, triumphantly announcing that her audience has witnessed the dangers of letting refugees across the border.

The main story starts quietly by characterizing our heroine, Svetlana, as fearful. She has just lost her teaching job, and we learn that she goes regularly to the cemetery to talk with her dead husband. She lives alone in the country and sleeps with a hunting knife under her pillow. Jobless and not having received her last pay, she goes hunting and runs across Bamba on a forest path. Terrified, she marches him at gunpoint to the border-patrol office, which is deserted because of the mission to capture the Afghans. She tries the Mayor (above), but is told to deal with him herself.

On the first night she ties him up in the yard but eventually allows him to sleep in a locked room on an air mattress. Gradually she becomes more hospitable, to the point where the villagers begin to gossip about her, doing the things that people shocked by interracial couples do–killing Svetlana’s dog and tossing rocks through the window.

In between such episodes Svetlana and Bamba talk to each other, he in perfect British-accented English and she in Bulgarian. We learn a lot about both, but they learn little about each other and can only convey ideas like “I want to wash your clothes” with hand gestures. Nevertheless gradually trust and even warmth are established.

One could argue that Bamba is a bit too close to being a Magic Negro. Not only does he speak perfect English, but he’s a medical doctor. He’s patient and polite and does his share of the chores around the house once Svetlana lets him in. Still, it’s hard to imagine a plausible plot in which a less respectable-looking, working-class black man could win her over in the same way. Plus he is an engaging character, and he makes the dour Svetlana turn into one, so we are unlikely to complain.

The film is shot in impressive black-and-white anamorphic widescreen. There is one spectacular shot that’s quite breathtaking. It’s a drone image, starting on a simple sea view, moving backward through an open-sided room in the building under construction, and continuing on and on to reveal an immense, rambling, unfinished complex.

Did some entrepreneur envision turning the town into a seaside resort and lose funding partway through? We never know, but it provides an odd contrast with the poverty of many of the residents of a seemingly failing town. The only connection to the plot is that the Afghans spend a miserable time trying to live there until the border patrol gives up and trucks them further into the country in search of a place that can deal with them.

Fear turned out to be one of my favorite films of the festival, alongside Sun Children. It’s available for streaming only in Wisconsin through tomorrow.

The Festival’s Film Guide page links you to free trailers, podcasts, and Q&A sessions for many of the films.

Thanks as ever to the untiring efforts of Kelley Conway, Ben Reiser, Jim Healy, Mike King, Pauline Lampert, and all their many colleagues, plus the University and the donors and sponsors that make this event possible.

Fear (2020)

Vancouver: Continuing our world tour

Eyimofe (2020)

Kristin here:

Turning back from documentaries to international art cinema, I’m recommending three films, two from Eastern Europe and one from Nigeria.

Servants (2020)

Ivan Ostrochovsky, an established Slovak producer of documentaries, whose first feature Goat (2015) was successful on the festival circuit, has followed it up with a second. Servants showed in the Encounters program at Berlin and earned enthusiastic reviews (Variety, Screen Daily).

The film opens with a flashforward as a body is dumped on a dark country road–a scene that will later be replayed when we have more information as to who the victim is. Suddenly a title, “143 days earlier,” appears, and the plot focuses on two beginning seminary students, Juraj and Michal. Briefly we seem to following their personal stories, but their introduction to the seminary routine serves largely as exposition for us. Signs of Communist repression of Catholicism begin to surface. A defiant note anonymously posted leads to a confiscation of all the students’ typewriters (above) in a search for clues as to its author.

The organization behind the repression is an actual historical agency, “Pacem in Terris,” which spied on and controlled the Catholic Church, from 1971 to the early 1980s. (The film is set in 1980.) Its goal was to seek out any signs of political activity, i.e., rebellion, among the clergy and seminarians. Juraj and eventually Michal join a small clandestine group of students working against Pacem in Terris. They become the targets of a ruthless agent, “Doctor Ivan,” (seen at the right below). He is the man responsible for the body-dumping in the opening.

Servants, impressively shot in black-and-white, has been called a film noir, and it certainly has all the sinister tone, the chiaroscuro lighting, and the ill-fated heroes of that genre, mixed with the trappings of art cinema.

Ivanovsky demonstrates how much suspense and dread can be packed into a mere eighty minutes.

On the Quiet (2019)

Another short feature that packs a lot of drama into its 81 minutes is Hungarian director Zoltán Negy’s first feature, On the Quiet. It deals with the touchy subject of alleged sexual abuse of a minor. The film’s smart script, co-written by Negy, is credited as having been developed at the “My First Script Workshop” of the Zagreb Film Festival. As I have suggested elsewhere, such workshops run by festivals have come to play a major role in making such sophisticated storytelling possible.

The main strength of the script is how it maintains an utterly balanced ambiguity about the allegations at its core. The beginning introduces the protagonist, Dávid, first violinist in a student orchestra in a prestigious music school. The teacher-conductor, Mr. Frigyes, employs eccentric techniques with the players. When Dávid fails to perform his solo part adequately in rehearsal, Frigyes tells the other students to gather round to massage his shoulders. This apparently helps him improve.

Soon Frigyes is giving private lessons to 14-year-old Nóri, a pretty, inexperienced but talented cellist. The first lesson we witness has him relaxing her by having them toss a ball back and forth. He touches her elbow and shoulder to adjust her posture. That is all that we witness. Yet soon Nóri complains to Dávid that the teacher has done “weird” things to her, but she won’t specify except to say they were “intimate.” Disturbed by this, Dávid gives her his phone to secretly record a lesson with Frigyes. The resulting dialogue could equally be the teacher directing the girl’s cello technique or instructions about sexual caresses. Dávid’s girlfriend points out to him that Frigyes uses his touchy-feely approach with all the students, but he persists in trying to discover the truth.

The situation escalates as Dávid informs a female counselor, who interviews Nóri and her mother. The girl denies that anything untoward happened. Still, the gossip spreads and the situation eventually threatens Frigyes’s position at the school. Did he abuse the girl? Did he simply not realize how his hands-on guidance could make the girl uncomfortable? Is she naively over-reacting to teaching methods that don’t seem to bother the other students?

I have seen one review that simply declares that the teacher is a perverted abuser, but the film seems far more subtle to me. Without ever implying that Nóri’s complaints should be dismissed, the film explores the effects of the spreading rumor on all those involved. It does show that no real investigation of the claims, which would be the logical way to proceed, ever takes place. In short, it is a careful presentation of its sensitive subject.

The film is well directed, though far from flashy. It does have the occasional striking shot, as when Dávid ponders the situation one evening (above) or sits talking with Nóri on a playground merry-go-round in an overhead shot (see bottom) that hides their expressions and suggests his confusion.

An interview with Negy about the film suggests that he is a thoughtful as well as a promising director–and one with three more film scripts underway.

Eyimofe (2020)

From the early 1990s, Nigeria has built up a thriving production of low-budget, DIY and professional films. At first distributed on VHS tape and then on digital disk, these have had enormous success at home and among the African diaspora. Kunle Afolayan formed a company that commanded government support and product placement to finance October 1 (2014), which played at film festivals, mostly within Africa. More recently, Kemi Adetiba’s The Wedding Party (2016) premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival, and Kathryn Fasegha’s 2 Weeks in Lagos premiered at the 2019 Cannes festival, where it was somewhat overshadowed by Mati Diop’s Atlantics, playing in competition.

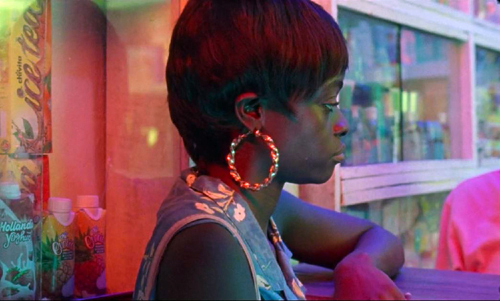

Now comes Eyimofe (This Is My Desire, in English, but much of the coverage on the internet uses the Yoruba title). It is directed by twins crediting themselves as Arie and Chuko, though their family name is Esiri. They have created an formally and stylistically impressive film that gives fascinating insights into the society of the sprawling conurbation of Lagos, an area with an estimated population of 21 million.

Arie Esiri studied Screenwriting and Directing at Columbia University’s School of the Arts, while Chuko Esiri earned an MFA, also in Screenwriting and Directing, from New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts. They wisely shot Eyimofe on 35mm, and the lush visuals exploit the bright colors of Sub-Saharan African clothing (see top of entry) and furnishings. Cinematographer Arseni Khachaturan adds bright colored light, especially at night and in shops, to create a gorgeous look (above and below).

The plot is split into two parts via titles: “Spain” and “Italy.” In each part, the main character is struggling to migrate. Mofe, an electrician, is gradually collecting the documents and money he needs for his move to Spain, where he will adopt the name Sanchez. Rosa, working both as a beautician and cocktail waitress, has similar aspirations to relocate to Italy, taking her younger sister Grace along. Both protagonists must scrape up money to pay for the passport, visa, fake letters promising employment, and other expenses. There are many complications, including a death in Mofe’s family and an unexpected revelation of the lengths to which Rosa and Grace will go to secure their passage.

The two stories are largely separate. There are moments when the characters pass each other briefly, and Grace even chats with Mofe at a little repair stand he sets up. Yet none of these chance encounters involves any causal connections between the two plots.

Early in the film Mofe visits an open-air “office” where a man who specializes in getting passports and visas–for a hefty fee (see top, where Mofe is on the right). In the background we glimpse a woman getting a passport photo taken against a white cloth. Late, near the beginning of the “Italy” section, we meet Rosa, having her passport photo taken in front of a similar backdrop (below). She’s in a different passport shop, however, suggesting that such informal establishments, vital for aspiring emigrants to cut through the red tape and delays of government procedures, are common in Lagos. It’s also the first of several parallels between her story and that of Mofe, clearly intended to suggest how common such struggles to leave for Europe are.

Unlike Mofe, Rosa aspires to a fun, modern social life, buying fancy clothes while sleeping with her landlord (who happens to be Mofe’s landlord as well) and then starting an affair with a wealthy Lebanese-American businessman. Her nightlife offers the occasion for flashy images, including the positively Godardian composition of her in a car with her friends (at the top of this section). As with Mofe, an unexpected death helps derail her plans, and we learn just how far she and Grace had been willing to go in their hopes for a better life abroad.

Eyimofe is a powerful film and well worth seeking out at a festival or on streaming. It’s having its UK premiere at the London Film Festival, which starts tomorrow. For a brief discussion by the directors about the film’s background, financing, and festival life, listen to this BBC radio interview. For a detailed description of the film’s success during its screenings during the Berlin festival from a Nigerian point of view, see here.

As a remarkably rich and successful festival draws toward its end, special thanks to Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, Jane Harrison, Curtis Woloschuk, and their colleagues for their help during it.

On the Quiet (2019).

Venice 2018: A dazzling second feature

Kristin here:

In my first report from the Venice International Film Festival, I described the excitement of seeing three excellent and quite varied films right in a row, at consecutive early-morning press screenings: First Man, Roma, and The Ballad of Buster Scruggs. We had to wait a whole two days before seeing what may be the masterpiece of this year’s festival–this year’s Zama, as it were.

I’m sure virtually everyone who attended the press/industry screening of László Nemes’s Sunset was wondering whether it would live up to his first feature, Son of Saul (2015), which won, among other prizes, the Oscar for Best Foreign Language film. It’s one of the more deserving winners of that prize in recent memory.

The narration famously concentrates fiercely on the central character, a Hungarian Jew forced to work in a death camp helping to kill and dispose of fellow Jews. The camera follows him from behind or circles to show his face, and keeps most of the horrors occurring around him dimly visible, in the background and on the periphery of the shots, usually out of focus. Mark Kermode praised the technique as a brilliant solution to the problem of not showing those horrors but seeing them reflected in one man’s attention and expressions. We so much admired this rigorous technique that we incorporated Son of Saul into the new fourth edition of Film History: An Introduction.

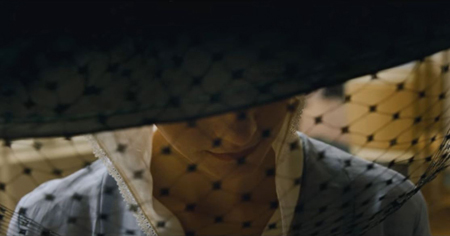

My suspicion is that many present at that first screening of Sunset in Venice were wondering if Nemes could do anything beyond similarly following a single character around, restricting our point of view in a dazzling exhibition of camera choreography centered on a single intense performance. Well, Sunset is based almost entirely on the camera following (below and top) or weaving around the central character, Írisz Leiter, or framing her face in medium close-ups and close-ups.

There are a many of these “nape-of-the-neck” framings, as we might call them, with only Írisz in focus–and not always her. Again, the point of view is highly restricted to what she sees, hears, and knows. She is present in virtually every shot, or revealed to be nearby. The apparent point of view shot into which the character steps is occasionally used in Hollywood and elsewhere, but here it becomes an insistent technique.

I suspect further that, seeing virtually the same device being used again, reviewers dismissed Sunset as a far less original work than Son of Saul. It helped that the latter was a tale of the holocaust and fairly simple to follow.

In my opinion, Nemes has done something extraordinary. He has taken the same basic approach but turned it to an entirely different use. Now the restricted point of view functions to slowly dole out clues in a complicated double mystery plot. The result is complex, tantalizing, and absorbing.

Sunset is difficult to compare with other films or artworks, since it so very original. It is thoroughly modern art cinema. (Nemes worked as an assistant director to Béla Tarr, though neither of his features reflects any direct influence of Tarr.) It also, however, has something of the air of Feuillade serials. Fantômas was made in 1913, the same year in which Sunset‘s action takes place. Sunset deals with an anarchist gang, and at one point Írisz disguises herself as a man and escapes captivity through an upper-story window. There’s also a considerable streak of Grand Guignol (the theatre that was then building to its height of popularity between the two world wars), with actual and attempted rapes, rumors of a grisly murder, and torch-lit attacks by the anarchist gang.

At least two reviewers have mentioned Mullholland Drive as a comparison point. I don’t think the two films have much in common, apart from their pleasantly puzzling aspects. It’s interesting, though, that reviewers grasped at such a comparison as a way of trying to convey the nature of a very unusual film.

In fact, Nemes has said that Blue Velvet was one of his inspirations. That actually makes far more sense to me, with an innocent gradually witnessing unimaginable cruelties.

What just happened?

The film depends heavily on our gradually getting clues and information as Írisz does, and to avoid spoilers I’m going to be vague describing the plot.

The heroine is the daughter of two founders and owners of Leiter’s, a high-fashion hat shop in Budapest. Orphaned, she has learned hat-making in Trieste and returns to Budapest, aspiring to work in the shop and regain what little connection she can with her parents’ heritage. Her application for a job there opens the film, but she is turned down by the current owner of Leiter’s, Mr Brill.

She soon learns that she apparently has a brother, hitherto unknown to her, who has committed a heinous murder five years earlier. While trying to track down the truth about him, she begins to suspect that Brill may be involved in equally hideous crimes. She spends most of the film wandering about looking for clues and trying to make sense of them.

Sunset is not as puzzling or opaque or illogical as reviewers seem to think. One reviewer refers to it as “befuddling,” which it certainly is not, if one pays careful attention. Lee Marshall, one of those who evoked Mullholland Drive, complains that:

Sunset begins to crumble, to offer itself up to scorn and absurdity, once we start asking questions like “Doesn’t Irisz have regular work hours?” or “How come she always manages to get a lift in a coach just when she needs one?”

In fact there is nothing mysterious about either point. The film makes it quite clear that Írisz is not hired by Brill, even though she offers to work for free. She has no “regular work hours” because she has no job. Brill offers to let her sleep in the Leiters’ rundown house where the store’s milliners live, but he clearly is trying to control her attempts at investigating the dual mysteries. He assigns her tasks to keep her busy, but Zelma, the store’s manager and possibly Brill’s mistress, pointedly tells her when giving her a little task to do, “It doesn’t mean you’re hired.” Another task that he assigns her ends up having to be executed by the other milliners, as Írisz constantly defies Brill by leaving the store and dorm at every opportunity. When Leiter and Zelma tells her not to leave without permission, she inevitably and defiantly departs on another investigative foray. Brill’s description of her as stubborn is a considerable understatement.

As for coaches, Írisz’s brother seems to control an anarchist gang consisting largely of coachmen, some of them with motives to drive Írisz to various destinations. Brill uses his coach to fetch her back to the store and as a setting for lecturing her about not defying him by trying to find her crazed, violent brother. Coaches become another way to try and control her movements.

Such mechanics of the plot are consistently motivated, whether we catch the motivation or not. The script is extraordinarily unified and tight, despite its complexity.

After two viewings, I was glad to discover that I had understood the basic plot on my initial one, although many subtle points were filled in.

Clues–but to what?

The narrative is structured through a chain of clues, which we learn only as Írisz does. Írisz is told something–initially, that she has a brother Kálmán. She tries to follow up that clue but is thwarted for a time. Eventually, wandering about or while accompanying the milliners of the shop to various celebrations of the store’s 30th anniversary, she bumps into people who provide her with new clues. Coincidental meetings and overheard conversations are rife here, but as David has pointed out, that’s how narratives work. If there’s one tradition that Sunset doesn’t belong to, it’s realism.

The other tradition it doesn’t belong to, of course, is classical filmmaking. In a Hollywood film, one clue would lead the protagonist to another and that to another, building the chain that resolves the mystery. The action would move steadily, even when obstacles that thwart the protagonist must be overcome, creating suspense. In Sunset, a clue may intrigue the heroine, but she finds no way to follow up on it. There is a frustrating pause another clue crops up. The sense of progression is thus sporadic and somewhat random, rather than linear and strictly causal.

The overarching ambiguities of the plot arise from the fact that Írisz frequently receives contradictory clues and is unable to decide whether Kálmán and Brill are heroes or villains. At one stage Írisz thinks her brother is a sadistic murderer, but later she begins to suspect he is a hero–and still later she again believes him to be a monster. A similar series of reversals happens with Brill. Thus we may conclude that we understand where the narrative development is headed, only to have our expectations reversed. It also takes quite a long time before we realize that the Kálmán Leiter mystery and the Brill mystery are connected, at which point we must rethink them both.

In a few cases we must even infer a clue that Írisz has been given in the interval between scenes. I must admit that on first viewing I was puzzled as to how Írisz finds where a key player in past action, Fanni, lives. Seeing it again, I realized that the scene where Írisz asks Andor, a young servant at Leiter’s, where she can find Fanni ends with Andor asking eagerly, “Can you make him come back?” He’s referring to Kálmán, whom Andor secretly idolizes. A cut begins a new scene with Írisz approaching the building where she finds Fanni. When she again sees Andor in the following scene, he asks, “Did you find the girl?” Thus it is clear that Írisz told Andor she would try to bring Kálmán back, as she may intend to at this point, and that he gave her the address. It’s not easy to grasp moments like this on the fly, but it’s far from impossible.

The decision to restrict our state of knowledge so thoroughly to that of Írisz, pushing the story to the edge of comprehensibility, was deliberate. In an interview Nemes, he says, “We had an overall strategy: the viewer should go into the labyrinth of the story with the protagonist, in order fo feel the disorientation and defencelessness the protagonist experiences. This subjective aspect is what connects ‘Sunset’ with ‘Son of Saul.'”

Rory O’Connor, writing on The Film Stage, caught the labyrinthine spirit of the film better than have the other reviewers I have read. He realized and accepted that one must re-watch the film in order to appreciate its complexities:

Sunset is a film awash with such delicious ambiguities, almost to the point of damaging its basic cogency at times (not least in simple geographical terms). That said, however disorientated I became while watching Sunset, I never grew frustrated. I did, however, begin to backtrack and second-guess myself just a little, which somewhat diminished the experience (and from speaking to other critics, I was not the only one). Yet the ambiguous will always face such early criticisms–just look at Mullholand Dr.–and I not only plan on seeing Sunset again; I will relish the challenge.

This is exactly what great art films can do: make us relish the challenge.

Seeing and yet not seeing

The film is easy to relish, given its original, systematic stylistic elements.

The cinematography has been widely admired, even by those who otherwise dislike the film. The long takes with the camera moving smoothly along with Írisz through crowded streets or circuitous interiors are virtuoso shots, justifying the use of consistently handheld camera as few films have done.

Beyond that, though, the tactic of throwing most planes of the scene out of focus is used in nearly every shot, so that we are forced intensely to concentrate on Írisz. This way we actually see even less than Irisz does, but we are not distracted from the dogged obstinacy and reckless courage of her quest.

The minute control of planes of action is masterly (above and below).

Throwing certain planes out of focus can become a motif (if one watches closely enough). Zelma is often seen out of focus in the backgrounds of scenes. In the frame at the top of this entry, she escorts Írisz to meet with Brill in the opening scene, when Írisz is applying for a job at Leiter’s. Zelma hovers in the middle ground in the frame at the top of the this section; in the frame just above, she’s in the distance, greeting the royalty from Vienna. She is seen for the last time disappearing into a soft, distorting view (bottom of the entry), going to either a posh job attending royalty or a grim fate. As usual, we have no way of knowing which, though we may suspect. The composition hauntingly recalls the early shot of her escorting Írisz, at the top.

I spotted only one shot where Írisz is wholly absent, late in the film, and that is a single tracking movement in the street inserted between two scenes. Nothing is in focus. By following Írisz we may not see everything, but without her we see even less.

Interestingly, Nemes and the cinematographer, Mátyás Erdély, originally intended to try and find an approach quite different from that of Son of Saul:

When we finished ‘Son of Saul’ and began to talk about ‘Sunset,’ we definitely wanted to do something that was very different. For example, if the aspect ratio was 1:1.37 in ‘Son of Saul,’ then it should be anamorphic 1:2.39 in ‘Sunset’; if ‘Son of Saul’ was to be photographed with a handheld camera, then let’s use the dolly for ‘Sunset.’ We made a mood test film, but the camera was in my hands already for the second shot. We realised that the kind of approach that László likes and that matches ‘Sunset’ requires that the camera be hand-held. We decided in advance that there would be dolly and anamorphic, however, in vain–in the end, it was 1:1.85 and a hand-held camera.

The film was shot in 35mm, with the final shot that constitutes the epilogue being set apart by filming on 65mm. Some release prints are available on film, and that’s what we saw in Venice. It was one of only two films shown on 35mm (the other being Vox Lux). See it on film if you possibly can. It’s gorgeous.

I unfortunately haven’t seen Son of Saul on the big screen, but Sunset is clearly a very different sort of film, much more epic in scale. It had a considerably bigger budget and is an historical piece about a beautiful, crowded city. The central set, Leiter’s Hat Store, depicts the luxurious goods that the upper classes and even royalty purchase. The filmmakers built Leiter’s in a vacant lot in a small street in Budapest’s Palace District, behind the National Museum. That way characters could exit the store and be followed by the camera into the bustling street lined with buildings that existed in 1913. As László Rajk, the production designer, says,

The space of ‘Son of Saul’ is an enclosed universe, the strict but also intimate world of the concentration camp. ‘Sunset,’ on the other hand, takes place in an open world, with all the sounds and noises of a big city. This means that in this film we–sound designer and production designer alike–had to create a completely different, open and noisy universe which reflects much less intimacy.

The amazing thing is that the designer took all this trouble and expense even though the lack of focus meant that most of the surroundings, both the built hat store and the real streets, would usually be only dimly visible to the audience. As Rajk adds, however, “those who played–and practically lived–their parts within [the store’s] walls had to believe every single second that they were in the year 1913, in Budapest, at its most elegant hat store full of secrets.”

We do occasionally see the store’s interior in focus, as in this, one of the two true point-of-view shots I spotted in the film:

Still, I would be hard put to figure out that layout of Leiter’s Hat Store or guess where the house where Írisz and the other milliners live is in relation to it.

If there’s one thing that reveals the vast difference between Son of Saul and Sunset, it’s that in the former we dread to see the offscreen, out-of-focus, peripheral things that are happening. In the latter, we yearn for a view of the crowded streets of Budapest and the splendid decor of Leiter’s Hat Shop. We are frustrated, channeled into watching Írisz but having a constant sense of the city which we glimpse occasionally in focus and more frequently in an evocative haze.

I look forward to relishing a third viewing.

As always, thanks to Paolo Baratta, Alberto Barbera, Peter Cowie, Michela Lazzarin, and all their colleagues for their warm welcome to this year’s Biennale.

Many thanks also to Michael Barker and Allison Mackie of Sony Pictures Classics for their help in preparation of this entry.

My quotations come from the interviews with the filmmakers in Hungarian Film Magazine (Autumn 2018), pp. 10, 11, 16, 17, 21. Nearly all of this issue is devoted to revealing interviews with the director, star, cinematographer, set designer, costume designers, and sound designer. In Venice, this issue was provided to the press, and it is available in its entirety online here.

Some photos from our Venice jaunt are on our Instagram page.

Camera connections: RED on FilmStruck: A guest post by Jeff Smith

Red (1994).

Jeff Smith here:

The Criterion Channel’s new installment in our Observations on Film Art series on FilmStruck presents me talking about Krszystof Kieslowski’s late masterpiece, Three Colors: Red (1994).

In the film’s final scene, chance and fate combine to bring a couple together. My comments trace how a cluster of cinematographic techniques has indicated the couple’s connectedness long before they become aware of one another. Red explores one of the director’s favorite themes: the ways that characters can be linked by mysterious, unspoken emotional bonds transcending the bounds of time and space.

Today I go into a little more depth regarding Kieslowski’s use of cinematography. Since there are spoilers, you may want to watch the film, on FilmStruck or some other platform, before going on.

Three colors, many meanings

Blue (1993).

Kieslowski made Red after Blue (1993) and White (1994). Although all were well received by critics, Red was the most celebrated. It won the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival and was nominated for three Oscars, including Best Cinematography and Best Director.

The widespread acclaim for Red proved to be bittersweet; Kieslowski died just two weeks before the Academy Awards ceremony took place. Although the director’s untimely passing might have given his film a boost in Oscar voting, Red ended up being overshadowed by other more high-profile nominees. Forrest Gump took home six awards, including Best Picture, Best Actor, and Best Director. Pulp Fiction topped Red for Best Original Screenplay. And the conventionally pretty imagery of Legends of the Fall aced out Piotr Sobocinski’s much more innovative work for Best Cinematography.

The basic conceit of the Three Colors trilogy derives from the nationalist ideals associated with the French tricolor: freedom, equality, and brotherhood. Kieslowski himself downplayed the significance of the tricolor by claiming that the films’ “Frenchness” was largely a result of the film’s financing. In interviews, Kieslowski claimed that the three colors of the trilogy could just as easily have been red, yellow, and brown if the money for the films had come from East Germany rather than France.

Still, even as Kieslowski himself made light of the films’ connection to French values, his comments can seem a bit coy. While the films continue Kieslowski’s longstanding interest in chance, fate, and parallel lives, each entry also offers an idiosyncratic take on the particular ideal associated with its respective color.

In Blue, Julie, the young wife of a composer, is devastated by the deaths of her husband and daughter in a tragic car accident. Forced to start anew after the loss of her family, Julie learns that her husband was not the man she thought she knew. In the midst of tragedy, the combination of grief and new knowledge paradoxically affords Julie a revitalized sense of existential freedom. With everything she had once cared about now gone, Julie relinquishes her roles as wife and mother, and her life takes unexpected paths as a result.

Deep sadness is not usually a trait that we associate with liberté. But Kieslowski’s surprising treatment of this theme is reminiscent of the famous line from Bob Dylan’s “Like a Rolling Stone” that states, “When you ain’t got nothing, you got nothing to lose.” Reduced to nothing, Julie finds new love and new purpose.

In a similar vein, White explores the idea of equality in rather unusual and unexpected way. One might expect Kieslowski film’s to be about political equality given his home country’s long struggle to achieve independence. Yet Kieslowski instead offers a dark comedy of betrayal and revenge.

The film explores the power dynamics of marriage by focusing on a young couple living in Paris. Dominique seeks a divorce from her husband Karol Karol, a Polish immigrant working as a Parisian hairdresser. The divorce leaves Karol impoverished. He is forced to go back to his native Poland where he plots revenge. White then takes an almost Hitchcockian turn as Karol fakes his own death but leaves evidence that incriminates Dominique. When Dominique is convicted for murder, Karol is finally able to “balance the scales” in his relationship. But the film’s haunting conclusion leaves Karol’s future with Dominique completely in doubt. In a distant POV shot, Karol gazes at his ex-wife through the window of her prison cell.

They exchange sad smiles, realizing that they still share an emotional bond despite their earlier duplicities.

He ain’t heavy, he’s my brother(hood)

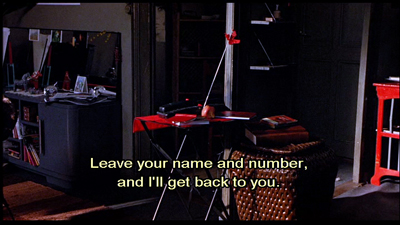

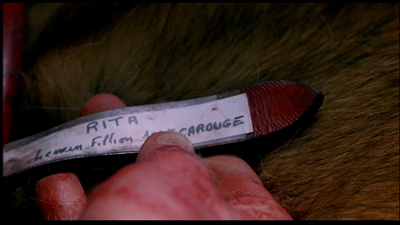

Kieslowski’s take on brotherhood (fraternité)in Red proves to be equally askew. The film’s central plotline concerns Valentine, a young model and student living in Zurich. She is brought by circumstance into the personal orbit of Joseph Kern, a cynical retired judge. Valentine has accidentally injured Kern’s dog, Rita, and seeks him out to see what she should do. Upon learning of the accident, Kern replies with indifference. Shocked by his apathy, Valentine asks Kern whether he would react any differently if it was his daughter who was run over.

Later Valentine returns to Kern after he sends money to pay for the dog’s veterinary care. During this visit, she discovers that the judge is using a radio to monitor the phone calls of his neighbors. Once again, Valentine rebukes Kern, this time for invading the privacy of others.

Chastened by Valentine’s disapproval, Kern begins to reform. He voluntarily confesses his spying to both his neighbors and police. He also accepts Valentine’s invitation to attend a fashion show in which she is a model. Under Valentine’s influence, Kern rejoins life, coming out of his isolation and resuming normal human interactions.

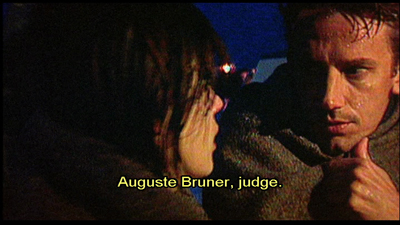

Red features a subplot involving a younger judge, Auguste, who is betrayed by his girlfriend, Karin. While the professions of the two men, Kern and Auguste, provide a simple story parallel, Kieslowski pushes this idea further than most other directors would. In fact, Kieslowski introduces so many similarities between the two characters that Auguste seems to be simply a younger version of Kern.

For example, the manner in which Auguste learns that Karin is cheating on him is remarkably similar to Kern’s account of his own wife’s infidelity. Moreover, Auguste owns a dog that he later appears to abandon much as Kern seems to give up on Rita after Valentine injures her. Both characters share a physical proximity to the other’s female counterpart. That is, Auguste lives near Valentine just as Kern lives near Karin. Lastly, Kern and Auguste both stop their cars at an intersection dominated by Valentine’s image on a huge billboard.

In a more telling parallel, Auguste describes an odd coincidence that occurs as he is walking to the site of his law exam. Auguste accidentally drops his book, and the book falls open to a page that contains information that later appears as a question on the exam. Later, after the fashion show, Kern describes an identical situation when he was a young man. Although Kern and Auguste never meet, viewers are further encouraged to recognize these similarities based on the physical resemblance of Jean Pierre Lorit to Jean-Louis Trintignant.

Instead of exploring brotherhood through more familiar conceits, like family, friends, or community, Red treats it as a metaphysical concept. In Red, brotherhood is an unseen force that binds people together, often in ways of which they are unaware. More importantly, though Kieslowski develops this idea through a story that is riddled with similarities, parallelisms, and synchronicities. And these apply not just to our two male protagonists, but also to the film’s central couple, Auguste and Valentine.

How do you represent destiny?

You’re a filmmaker. The story you’re telling is about a couple that spends much of the movie separate from one another. Perhaps they don’t meet until late in the film, maybe not until its final scene. How do you communicate to the audience that these two people are destined to be together? Over the years, filmmakers have utilized a wide range of techniques and devices to solve this problem.

In some early musicals, filmmakers created parallel scenes featuring each character to foreshadow their later romance, as in Ernst Lubitsch’s The Love Parade. First, the caddish Count Alfred talks with his valet and sings “Paris, Stay the Same.” Then Queen Louise talks with her courtiers and sings “Dream Lover.”

More recently, filmmakers include certain plot details to suggest that the characters are meant to be together. In Sleepless in Seattle, Annie believes herself to be reenacting scenes from the Cary Grant-Deborah Kerr weepie, An Affair to Remember. Annie takes each of these uncanny experiences as signs that the radio caller named Sleepless in Seattle is her true soul mate.

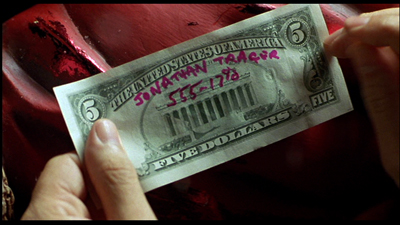

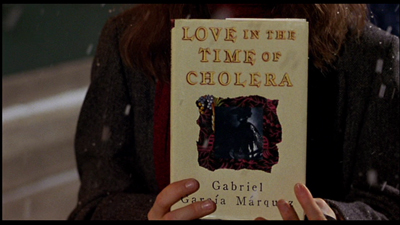

In Serendipity, John and Sarah meet in the film’s first scene. They separate, but they send personal tokens into the world inscribed with their names and phone numbers: a $5 bill and a copy of Love in the Time of Cholera. If these items return to their lives, it will be a sign that the couple will reunite.

In other cases, a filmmaker might use the formal properties of the medium to hint at the character’s destiny. In Turn Left, Turn Right, Johnnie To uses color and composition to anticipate the couple’s fateful encounter late in the film.

In Red, Kieslowski relies on a similar cluster of devices to suggest the workings of chance and fate for Valentine and Auguste. Like the films mentioned above, the director foreshadows the fate of his characters through a number of odd coincidences. At one point in the film, Valentine voices her hopes that her boyfriend, Michel, will call when the phone suddenly rings. Similarly, during one of Valentine’s visits to Kern’s home, they eavesdrop on Auguste and Karin discussing their plans for the evening. Auguste decides to flip a coin to determine whether he will sit home studying or will join Karin for an evening of bowling. As Kern and Valentine listen to this conversation, the judge also flips a coin, which comes up with the same result reported by Auguste.

Later in a visit to a music shop, Valentine listens to an album of music by the composer Van den Budenmayer. Unbeknownst to her, Auguste and Karin listen to the same album just a few feet away. (Taste in music seems to link all four of these characters, as we see this same Van den Budenmayer record in Kern’s home.)

Although these parallels provide a narrative basis for Kieslowski’s theme of connectedness, they are strengthened by his stylistic choices. Four particular techniques emerge as the most salient: the use of color, framing, deep staging, and camera movement. Of these, camera movement is the most important.

Oh, telephone line, please give me a sign

The use of camera movement to suggest the couple’s connectedness is established in the film’s first sequence, which follows a phone call’s path through a communication network that links England to Switzerland. Red begins with a medium close-up of a man dialing a telephone.

Although we don’y realize it at this early point in the film, in retrospect, we can surmise from the framed photograph of Valentine and the copy of The Economist sitting on the desk that this is Valentine’s boyfriend, Michel, who is working in England.

As we hear the number being dialed, the camera follows the phone line down to the socket in the wall. The next shot of the sequence traces the phone’s electromagnetic signal as it feeds into a major trunk line for thousands of other phone customers. The camera begins to spin as it moves forward through these wires. The resulting image is a welter of color and movement.

In the next shot, the camera continues to move forward rapidly, following the signal as it passes through the underwater cables buried beneath the English Channel. Here again, we might easily miss the significance of this shot since it comes so early in the film. Yet it plays an important role by foreshadowing the location of the tragic ferry accident that concludes the film.

The camera dips into, then out of the water, and reverses course, now tracking rapidly backward. It seems to pass through several red brackets that arch over the phone company’s transatlantic cables. The next two shots chase the signal as it travels in the phone lines of an apartment complex. By now, the camera is moving so fast that the lateral tracking movement is seen as a blur of light and metal. The next shot shows the camera spinning wildly. The camera then swishes past a telephone switchboard until it finally stops on a single flashing red light.

For a director not especially known for stylistic flourishes, this opening camera movement is a real corker. Yet its significance goes beyond extravagance. It previews the way Kieslowski will use camera movement to underscore the characters’ physical proximity to one another. It also foreshadows the many missed connections Valentine and Auguste will experience before finally meeting one another at the end of the film.

Morning routines, broken glasses, and fortuitous falls

Later camera movements creating physical connections are more staid than this bravura opening sequence. But they do establish a pattern that carries through the remainder of the film.

The next scene begins with a shot of Auguste gathering his books and preparing to take his dog for a walk. The camera follows Auguste and his dog as they cross the street, but drifts away from them, craning up past the red awning of Chez Joseph to introduce our protagonist, Valentine. The camera reframes Valentine as she moves about her apartment engaged in a phone conversation, confessing her loneliness as she prepares to leave for a photo shoot.

When Valentine mentions the weather, the camera tracks toward an open window, allowing us a glimpse of Auguste in the distance, returning to the entrance of his building. By blocking and framing the scene in this way, Kieslowski cleverly creates a bookend effect. It begins and ends by underlining the characters’ proximity to one another, suggesting a strange synchronicity to their actions in the process.

As the film goes on, Kieslowski encourages the viewer to notice the way that Valentine and Auguste’s paths continually cross, even as they remain largely ignorant of one another’s presence.

Consider the scene in which Valentine wins a jackpot playing the slot machine. Kieslowski begins the scene with a shot of Valentine exiting her car. The camera tracks slightly to the left to reframe Valentine as she walks to the entrance of Chez Joseph. Valentine buys a newspaper, and as she begins to read the front page, a figure steps in front of her holding a carton of Marlboro cigarettes.

The figure passes through the frame so quickly that it’s only in the subsequent shot that we realize it was Auguste, seen here entering his apartment with his dog. After Auguste has exited the frame, the camera racks focus at the same time that it pans left and tilts down to reveal the slot machine. We then see a close-up of Valentine’s hand as it enters the frame and pulls the handle downward. In this instance, Kieslowski’s framing makes us work harder to see the connectedness of the characters. Auguste is framed so that we only see his torso. Valentine is framed so that we only see her hand.

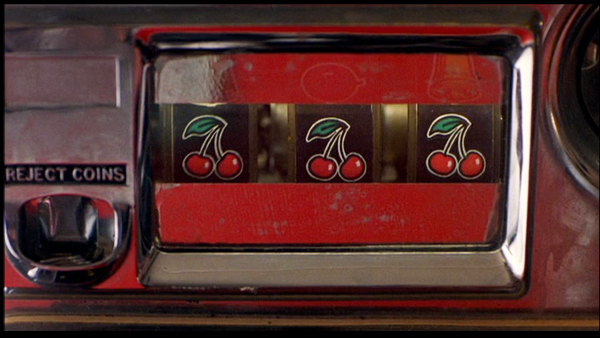

Later in the film, Auguste is unable to contact his girlfriend and drives off in a panic. He makes a hasty U-turn, framed through the window of Chez Joseph. As the red Jeep pulls away, the camera tracks right to follow it, but then continues its movement toward the slot machine, revealing three cherries that earlier produced Valentine’s jackpot.

The owner of Chez Joseph had told Valentine the three cherries were a bad omen. It will prove to be true as well for her counterpart, Auguste.

Another example of the couple’s connectedness occurs in the brief scene at the bowling alley. After a couple of shots that establish the setting and Valentine’s presence within it, Kieslowski cuts to a shot of Valentine rolling her second ball of the frame. The camera is positioned in the space behind the seating area in the alley.

From this initial set-up, the camera then tracks left past several other bowlers and stops on a close-up of a broken beer glass, a lit cigarette, and a crumpled package of Marlboros. The camera cranes up slightly on these objects, lingering briefly to enable the viewer to grasp their significance. Here again, Kieslowski has opted for a slightly elliptical way to suggest Auguste’s presence, which was presaged by the phone conversation overheard by Kern. The broken beer glass and lit cigarette suggest that Karin never showed up for their date, and further that Auguste left the alley in a huff.

Perhaps the most interesting camera movement in Red occurs in the scene in which Kern and Valentine meet after her fashion show. Kern explains that when he was a young man, he used to sit in the balcony in that same auditorium. On one occasion, he dropped a book and it fell several feet to the floor below, but opened to a section that is covered on the law exam he was about to take. (Recall that the same thing happens to Auguste as he crosses the street.)

Kieslowski could simply have Kern recount his story, but instead the director treats the moment much more dynamically. The camera traces the path of the book’s fall. The camera starts at a high angle looking down at Kern and Valentine near the stage, and ends at a low angle looking up at them.

Through a simple camera movement, Kieslowski has reinforced another of the film’s major themes: the interpenetration of the past with the present.

The unbearable redness of Being

As I’ve already suggested, camera movement seems to be the most important device for conveying Kieslowski’s central themes. It’s a vivid way to physically embody the unseen connections that link Valentine and Auguste together before their coincidental meeting after the ferry accident.

Still, camera movement is not the only technique to carry such significance. Color also proves important, especially since the film’s title prompts particular attention to it.

Toward the start of the film, Kieslowski seems to tease us with all of the red things that appear in the frame as in the shots of Valentine’s apartment and the ballet studio.

Yet he was also careful to point out that red is not even the dominant color in the film’s palette. Working with the film’s production designer, Kieslowski opted to emphasize browns and blacks, in part because the colors are associated with the world of courtrooms and legalese that connect Kern with Auguste.

Yet, even as an accenting color, red still draws the eye toward it. One reason for this is Kieslowski’s restricted palette, which features very little green and almost no blue. Red pops out because it is often the only bright color within the mise en scene, which mostly features more neutral earth tones.

Because red is conventionally associated with things like love, passion, anger, and danger, we might be tempted to match those meanings to the film’s story. And there are some moments in Red where such color symbolism seems like a possibility. Consider, for instance, the insert of Valentine’s bloodstained hand checking Rita’s tag.

Yet, for every one of these moments, there are a dozen others where the color seems to have no such correlation. Why, for instance, would we ascribe passion or anger to Chez Joseph’s awning or to the three cherries on the slot machine?

Since the color is present in almost every scene, one would be hard-pressed to find any coherent pattern based on such traditional associations.

Instead, like camera movement, red seems to function as a visual metaphor for the film’s off-kilter treatment of brotherhood. Indeed, Kieslowski anticipates Auguste and Valentine’s eventual coupling by consistently linking them to red props and decor. Auguste has his red jeep, which we see several times throughout the film. He also is shown toting cartons of Marlboro cigarettes, which are identifiable through the brand’s signature color.

Valentine, on the other hand, is frequently shown with red colored clothing and textiles. When Valentine takes Rita out for a walk, she wears a red sweater and carries a red leash. She sleeps with a red shirt that serves as a substitute for her absent boyfriend, Michel. During a photo shoot, Valentine poses against a vibrant red backdrop. Lastly, Valentine is shown in several different settings where the décor is dominated by red, such as the ballet studio, the bowling alley, and the auditorium where the fashion show takes place.

Viewed in this respect, color in Red functions as a classic instance of an intrinsic norm. By rejecting more conventional extrinsic meanings associated with the color, Kieslowski instead treats red as something that develops more localized significance. Given his longstanding interest in the workings of chance, fate, and destiny, it should not surprise anyone that red objects, costumes, and settings come to symbolize these larger cosmic forces.

The Breath of Life

The color red is also prominent in Valentine’s “breath of life “ billboard ad. The ad is shown at least six times in the film, and its recurrence will play an important role in preparing for the film’s climax.

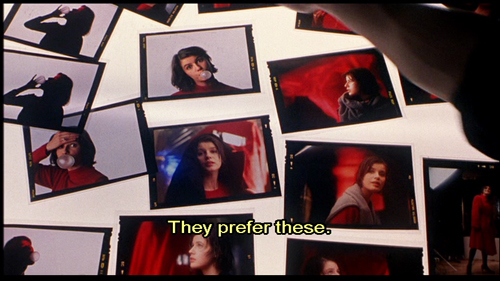

We first see the ad in production during Valentine’s photo shoot. She is posed in profile, and her mood seems playful. She blows a bubble with her gum, presumably using the product featured in the campaign. The photographer asks Valentine to remove the gum from her mouth and to tie her sweater around her neck. He then instructs her, “Be sad. Sadder. Think of something awful.” By asking Valentine to imagine tragedy, the photographer is able to get the image he wants.

We see the resulting photograph a few scenes later amongst a pile of other snapshots from the session. Jacques, the photographer, calls our attention to it by indicating that the shot likely will be used in the campaign.

The billboard itself is later shown on two separate occasions. We first see it looming over the traffic intersection where Auguste’s red jeep is stopped.

We see the same image again when Kern drives to Valentine’s fashion show.

It appears again just before the film’s climax in a brief shot showing workmen taking the billboard down.

One might assume that Kieslowski has put a cap on the “breath of life” visual motif. But he revives it one final time, albeit in a way that inverts much of its earlier significance in the film’s plot. Red’s climactic scene begins with Kern walking outside to retrieve his newspaper. On his way back, he glances at the headline, which notes that hundreds of people are dead in a ferry accident on the English Channel.

Kern then turns on his television to learn the latest news of this tragedy. A reporter states that there were only seven survivors of the accident. In a rather tongue-in-cheek gesture, six of the seven survivors happen to be characters from the Three Colors trilogy. We first see a shot of Julie Vignon, who is described by the reporter as a composer’s widow.

This is followed by shots of Karol Karol and his wife Dominique.

Next comes a shot of Olivier Benoît, a family friend who had become Julie’s lover in Blue.

Finally, we see a shot of the two Swiss survivors, Auguste and Valentine.

For the first time in the film, the two characters are shown looking at one another. The television image freezes on Valentine and Auguste.

The camera slowly zooms in on the image on the television to get a closer view of Valentine. When the zoom ends, the video image is eerily similar to the “breath of life” billboard.

The gray blanket has taken the place of Valentine’s sweater and the red windbreaker of a rescue worker replaces the red cloth backdrop of the ad. But Valentine’s facial expression and pose approximate that in the ad.

The video image, however, seems to reverse many of the advertisement’s earlier associations. During the shoot, Valentine only pretends to be sad. Her expression and pose are commodified, used to sell chewing gum to punters taken in by the image’s sensuous visual appeal. In contrast, the video image of Valentine’s rescue captures her genuine response to tragedy. Valentine’s look expresses a sense of shock and surprise that she survived when so many of her fellow passengers died. Moreover, the gloss of the billboard advertisement has been replaced by the roughhewn look and “on the fly” reality of video reportage.

From this shot, Kieslowski cuts to an enigmatic medium close-up of Kern, who stares into the morning sunlight through his window.

The shot seems to pose more questions about the story than it answers. Is Kern merely relieved by the news that Valentine has survived? Or is there something deeper behind his rueful smile? Does Kern feel responsible for Valentine’s situation? After all, he recommended that she take the ferry rather than fly and asks to examine Valentine’s ticket in their last meeting together.

For some critics, the shot adds a Shakespearean wrinkle to Kieslowski’s film. For these critics, this shot suggests that Kern, like Prospero in The Tempest, has conjured the storm out of thin air in order to satisfy his psychological desires.

Whether or not we see this moment as a reference to The Tempest, it seems clear that Kern has uncannily anticipated Valentine’s fateful encounter with Auguste throughout the film. Consider the following:

- Kern predicts Karin’s breakup with Auguste. He also claims that, despite Auguste’s declaration of love for Karin, that Auguste has not yet met the right woman. This language is echoed later when Kern describes his own despair after learning of his wife’s affair. The Judge says to Valentine, “Perhaps you are the woman I never met.”

- Earlier in the film, Valentine says she is thinking of cancelling her trip to England because of her brother Marc’s legal troubles. Kern insists that she keep her travel plans saying it is her “destiny.”

- Kern acknowledges that he crossed the English Channel as a younger man in pursuit of his wife and her lover, Hans Holbling. His quest came to naught, however, when he learned that his wife died in an accident. Both the trip and his wife’s fate prefigure the ferry tragedy that ends the film.

- Kern describes a dream he has of Valentine as an older woman. Kern’s account of the dream prophesies that Valentine will meet a man and that the couple will grow old together.

All of these things seem to foreshadow Auguste’s fortuitous meeting with Valentine in the aftermath of the accident. Since Kern is, at least in some indirect way, responsible for the couple’s meeting, he has given Valentine a gift in addition to the pear brandy that the two previously enjoyed together. In Auguste, he has given Valentine a younger version of himself.

At its heart, Red is an existential mystery. When Valentine and Auguste meet at the end, their union seems less like coincidence and more like the outcome of divine intervention. Yet, in retrospect, Kieslowski has carefully prepared us for this moment by using color and camera movement not only to underscore their physical proximity, but their many missed connections.

In exploring the French value of fraternité, Kieslowski’s unusual treatment of the subject emphasizes the invisible forces that bind people together even as they elude our conscious grasp. Although Kieslowski likely didn’t intend Red to be a valedictory film, it is a fitting testament to his larger oeuvre as a director. In a story suffused with grief and regret, Red’s final scene suggests that love and hope can bloom in even the most bleak situations.

Thanks as usual to the Criterion team, particularly Peter Becker and Kim Hendrickson, for their support. Kristin, David, and I are very happy to be involved with their FilmStruck activities.

For more on Krzysztof Kieslowski’s films, see Annette Insdorf’s Double Lives, Second Chances: The Cinema of Krzysztof Kieslowski, Joseph G. Kickasola’s The Films of Krzysztof Kieslowski: The Liminal Image, and Marek Haltof’s The Cinema of Krzysztof Kieslowski: Variations on Destiny and Chance. Two collections of interviews with Kieslowski have been published: Kieslowski on Kieslowski and Krzysztof Kieslowski: Interviews. For a concise overview of the films in the Three Colors trilogy, see Geoff Andrews’ monograph in the BFI modern classics series.

An earlier entry considers the ways that film stories rely on chance and coincidence, with Serendipity as a central example.