Archive for the 'National cinemas: Eastern Europe' Category

Wisconsin Film Festival: Cutting to the chase, and away from it

Nocturama (2016).

DB here:

Despite my recent jab at D. W. Griffith, I gladly give him credit for making crosscutting a central technique of narrative cinema. Using editing to switch our attention from one story line to another is a fundamental resource of moviemaking everywhere.

Crosscutting is most apparent in those passages of quickly alternating shots that build tension during chases and last-minute rescues. That’s a prototype of what we credit Griffith with consolidating. But crosscutting is used outside such climactic stretches. Hollywood silent features often crosscut story lines throughout the film, without pressure of a deadline and without much happening in some lines of action. It seems to be a way that filmmakers found to keep the audience aware of many story strands.

Crosscutting is a cinematic version of a very old narrative strategy, that of alternating presentation. Once you have several story lines, you can switch among them. Homer does this in the Odyssey, interweaving Ulysses’ wanderings, Telemachus’ efforts to find him, and Penelope’s holding off the suitors.

Homer initially handles these lines in large blocks, in separate “books.” After attaching us to Telemachus in Books 1-4, Homer shifts us to Ulysses for a long stretch. Such interlacing can be found in medieval narrative too, and of course it dominates modern novels, with chapters shifting among action lines and character viewpoints.

Crosscutting large chunks can give way to shorter bursts. Ulysses’ travels occupy several books, but as he approaches Ithaca, Homer interrupts Book 15 to switch back and forth between him and Telemachus, also headed for home. In cinema, this sort of accelerated crosscutting, often driven by a deadline, has become identified with Griffith’s The Lonely Villa (1909), A Girl and Her Trust (1912), and other Biograph shorts. He lifts the principle of crosscutting to a vast scale in his features. The Birth of a Nation (1915) alternates North and South, home front and battlefront, carpetbaggers and Klansmen in a novelistic fresco.

Crosscutting usually implies some degree of simultaneity. While Telemachus searches for his father, Ulysses leaves Calypso and the suitors run riot in the palace. The notion of actions taking place at more or less the same moment is especially important in chases and last-minute rescues.

As a plot reaches its climax, there can be a sort of site-specific crosscutting too. Once Ulysses and Telemachus have joined forces to slaughter the suitors, Homer’s narration sometimes switches among areas of the fight, as in the battle scenes of the Iliad. While father and son hold off the suitors in the main hall, two servants capture one suitor in a storeroom. We recognize this technique of adjacent alternation when novels and films gather all the major characters in one spot for the climax and shuttles among them.

Crosscutting remains a basic filmmaking tool for most movies on our screens. Where would the Fast and Furious franchise be without it? But some contemporary filmmakers have made fresh uses of the technique. In Inglorious Basterds, Tarantino adopts the big-segment option, alternating lengthy blocks of action before using faster crosscutting when characters converge at the climax. Christopher Nolan has experimented with various tactics, including crosscutting different phases of the same action (Following) and crosscutting among embedded segments, dreams within dreams (Inception).

So there are still lots of options out there to be explored. Just look at some films shown at our Wisconsin Film Festival. Beware, though, of light and heavy spoilers.

Attachment plus anxiety

Frantz (2016).

At one end of the spectrum: Must you always use crosscutting? Wigilia, a charming short feature by Graham Drysdale, suggests not.

It’s built on two Christmas eves a year apart. In the first, a Polish refugee who cleans house for a brusque businessman is alone for the holiday and in his apartment prepares the traditional holiday meal—not for herself but for her absent family. She’s interrupted by the businessman’s vaguely hippy brother, and the two learn about each other as they share the meal. In the second evening, after the businessman has left the apartment to his brother, she returns and they bond more intensely.

Apart from an inserted dream sequence, we stay within the apartment. This concentration derives from the production circumstances; Graham explains that he was given a chance to make the film in short order, and to keep it manageable he came up with the idea of limiting the locale. He shot 53 minutes of footage in five days in the apartment, then did the two final scenes in two days. The narrowly focused drama, with many lines improvised, has no need for the free-roaming tactics we associate with crosscutting.

Crosscutting tends to give us a fairly unrestricted range of knowledge; often we know more than any one character. In The Girl and Her Trust, the telegraph operator holding off the robbers can’t be sure that her boyfriend is rushing to her rescue, and he can’t know how close the robbers are to seizing her. Alternatively, when we’re mostly restricted to one character, we don’t find a great deal of crosscutting.

That’s the case in François Ozon’s Frantz, a remake of Lubitsch’s Broken Lullaby (1932), also shown at WFF. Anna’s fiancé Frantz has been killed in the Great War. Out of sympathy his parents have taken her in and treat her as a daughter. But when she sees Adrien, a melancholy Frenchman, haunting Frantz’s grave, she gets curious. Most of the ensuing film is restricted to what Anna learns,

Adrien visits the family. Flashbacks lead us to think he’s what he hesitantly claims to be: a friend of Frantz from prewar Paris. But he has been pressed to tell the parents what they wished to hear. Adrien actually came to the village to beg their forgiveness for killing Frantz on the battlefield, where they met for the first time. Although we surely have reservations about the sad, apprehensive young man, we don’t learn the truth until Anna does, at about the midpoint of the film’s running time. By this time she has fallen in love with him.

There is some alternation of viewpoint in the film. A few scenes attach us to Adrien during his stay in the village, chiefly when he confronts bitter locals who still consider France their enemy. Still, these scenes don’t give us much direct information about the true backstory. And after Adrien has left and Anna has sought to keep the parents in the dark about the past, we remain attached to her. No crosscutting shows us Adrien’s return to France and his life there. As a result, we’re able to feel curiosity and suspense when Anna decides to track him down. The revelation of his civilian life raises a set of unexpected conflicts.

Both Wigilia and Frantz show that avoiding crosscutting can be a powerful way to keep our attention fastened on characters, the better to let their words and behaviors, as well as their inner lives, get primary emphasis. Crosscutting yields a panorama, while refraining from it can aid portraiture.

Crosscutting as usual

The Student (2016).

More toward the center of the spectrum lies ordinary crosscutting, the alternation among scenes that provide a broad perspective on the action. In Arturo Ripstein’s Western Time to Die (1965), the plot alternates between scenes featuring the returning convict Juan Sayago and episodes showing the reactions of different townsfolk—chiefly the sons of the man he killed. We also learn of efforts from women in the town to prevent the sons from taking revenge. This “moving-spotlight” narration isn’t perfectly omniscient, though. The plot gradually fills in information about what led up to Sayago’s crime, while revealing that the sons’ mission would amount to avenging a dishonorable father.

A similar sequence-by-sequence approach is seen in The Student, aka The Disciple, a Russian film by Kirill Serebrennikov. A fanatical teenager has become the scourge of the classroom, barraging teachers and pupils with Bible quotations and denunciations of bikinis. His mixed-up fundamentalism, which leads him at one point to challenge evolution by donning a gorilla outfit, is unpredictable and a pure power trip, Biblical bullying.

His mother can’t manage him, the administrators are reluctant to take stern action, and the school priest sees him as a potential recruit to the clergy. Only one teacher, Elena, challenges him with a mix of humor and sympathy. But to combat his increasingly wild behaviors, which include making himself a full-size cross which he can stretch out on, she too sinks into Scripture. She hopes to quote the Bible back at him and dislodge his dogmatism, but she too becomes obsessed and estranges herself from her boyfriend. Meanwhile, Venya gets his one true disciple, a limping underdog, and his campaign against homosexuality, science, and secularism turns violent.

A good part of the narration locks us in to Venya’s Dostoyevskian ferocity, thanks to a restless use of the “free camera” in lengthy following shots. (The film has only about 150 shots in 113 minutes.) But we do range more widely to get a broader view. The moving spotlight shows the mother’s frantic consultations with school officials, and Elena’s clashes with them, as well as with her boyfriend. Still, the climactic scene, which assembles all but one of the characters in a single meeting, has no need of a broader view. Like Wigilia, The Student draws its final power from drilling down into a confrontation around a table.

Gaps and folds in time

Killing Ground (2016).

Griffith rang many changes on his last-minute-rescue template, and one of the most startling occurs in Death’s Marathon (1913). A dissolute husband, bored with his life, decides to commit suicide and notifies his wife by phone. She calls the family friend, who races to prevent the death. Surprise: He’s too late.

A hundred-plus years later, crosscutting builds and then deflates suspense in the Romanian film Dogs, by Bogdan Mirica. There are two protagonists: Roman, a city fellow who has inherited his grandfather’s idle farm, and Hogas, the police chief. Both face off against sadistic hoodlum Samir and his thugs. A human foot has popped up (literally, in the first shot), and Hogas tries to trace its owner, while Roman decides how to dispose of the farm. Samir explores other possibilities, none very savory.

At first we’re restricted to Roman, who is frightened by distant lights and gunshots out on the property, and Hogas, who doggedly pursues his investigation. The alternation between them keeps Samir offscreen for some time. When he surfaces in a suspenseful drinking bout with Roman, and when Roman’s girlfriend comes to pay a visit, the threats start building.

The climax starts out as pure Griffith. Mirica crosscuts Roman’s drive back to rescue his girlfriend, Hogas’ pain-ridden walk to the farmhouse, and Samir’s ominous approach to the isolated woman. Interestingly, the pace of the cutting doesn’t much accelerate in these last moments; there isn’t a lot of alternation, and the emphasis is on prolonged actions (Hogas’ trudging pace, interrupted by coughing up blood, and Samir’s laconic dialogue with the girlfriend).

By the time Hogas arrives, he finds he’s too late. The conventional mystery and suspense of the first stretch are undercut by showing us only the eerie aftermath of a violent climax. Art-cinema norms can de-dramatize crosscutting, but the maneuver remain a revision of what Griffith tried for in 1913.

Three years after Death’s Marathon, Griffith showed the possibility of crosscutting radically different time frames. Intolerance (1916) interweaves four historical epochs while using crosscutting within each one as well. Since then, crosscutting has sometimes been used to juxtapose past and present (The Godfather Part II, The Hours), or alternative futures (Sliding Doors), or a real story and a fictional one (Full Frontal). Interestingly, Griffith is a bit more daring than these directors. These films usually alternate sequences or entire blocks. At first Intolerance does that too, using titles to mark the shift among its four eras. But as the film reaches its climax, Griffith cuts freely from one period to another. These shot-to-shot time shifts, jumping centuries in the burst of a cut, remain an audacious formal discovery.

In all these examples, we’re cued to realize when we move to another period. But Killing Ground, a grueling Australian thriller by Damien Power, doesn’t announce its time-shifting. It exploits our default assumption that crosscutting implies more or less simultaneous action.

At first Killing Ground does give us rough simultaneity, alternating between the yuppie couple, Ian and his fiancée-to-be-Sam, and a pair of gun-loving locals. But then the couple make camp near another family’s tent.

Through careful use of eyeline matches and other continuity cues, the narration welds together actions that are actually taking place at different times. The family’s evening meal and their foray into the woods happen well before Ian and Sam arrive, but the cutting implies that the two groups are living side by side.

Like Griffith, at moments Power shifts between the two periods on a shot-by-shot basis. Small disparities, like a baby bonnet and the placement of the campers’ vehicles, accumulate. By the time Ian follows one of the psychopaths into the woods, we realize that earlier events have been salted through the present-time action, the better to delay revealing the family’s fate. From then on, orthodox crosscutting takes over as Ian runs for help and Sam tries to hold the rampaging peckerwoods at bay.

The kids aren’t alright

At the distant end of the spectrum, how about building a whole movie out of full-blown crosscutting? A sustained example at WFF was Bertrand Bonello’s Nocturama. (Major spoilers ahead.)

For the first fifty minutes or so, we follow nine young people silently threading their way through Paris. They ride the Métro, pace along the street, pair up, separate, crisscross, and assemble at four sites—a line of parked cars, an office building, a Ministry, a statue of Joan of Arc. They’re setting bombs.

We can identify them only through their looks and behaviors. David and Sarah touch fingers fleetingly on a train. We learn from flashbacks that Samir and Sabrina are sister and brother, and their friend is the younger African Mika, all presumably from emigrant families. Flashbacks also show them meeting to plan their action and, once set on course, dance the night away.

There’s an unexpected shooting, but the bombs go off more or less as planned. The group assembles in an upscale department store to meet another confederate, the security guard Omar who will host them overnight. This brief “nodal” moment of unification melts away. Crosscutting follows them as they wander from floor to floor in a parallel to their passages through Paris.

The first section merges the art cinema’s best friend, the prolonged walk, with a thriller-based suspense: we don’t really know what they’re up to until we see a pistol at around 18 minutes and bomb materials somewhat later. The threads knot when we see a quick montage of the bombs.

This fine-grained crosscutting looks ahead to the fragmentary handling of the action in the department store, where the moving spotlight shifts rapidly as the conspirators disperse, assemble in pairs or trios, and disperse again.

Crosscutting is the principal way filmmakers imply simultaneous action, but a lesser option, often favored by Brian De Palma, is the split screen. Bonello uses this device to show the result of the bombings. The shot looks forward to the quiet surveillance-camera display in the security office as the police prowl the shopping aisles. We see the kids moving from quadrant to quadrant, with an occasional flare marking a nearly soundless kill.

The terrorists’ motives are barely sketched, and they’re a cross-section of middle-class and working-class kids. Some are unemployed, others have low-end jobs, while others are on track for professional careers. A flashback shows several, perhaps meeting for the first time, while waiting for job interviews. The film’s second large part paints them as victims of consumer lust as they try on upscale fashions and make-up, but the point isn’t hammered home. To some extent they’re just killing time in what they think is a safe house.

Nocturama‘s crosscut climax balances, in more condensed form, the first section, as the conspirators are discovered by the police. At one point, an innocent who has come upon them by accident gets more emphasis than the gang members. His final moments are replayed through multiple viewpoints, as if the stranger’s fate drives home to them what death looks like up close. Soon enough each one will know exactly.

It might seem the height of film nerdery to join up films seen at a festival through their different uses of one technique. But is it any more of a strain than those journalistic accounts of how a batch of festival choices reflects The Way We Live Now? Every Berlin or Cannes or Toronto seems to bring forth think pieces looking for a common thread among radically different films, hoping to find today’s social mood in movies begun perhaps years before? Like most zeitgeist readings, they’re pretty easy to whip up.

But technical choices are more concrete than hints of the mood of the moment. Moreover, if you’re interested in cinema as an art, it can be enlightening to reveal the variety of creative options that are still available. The art may not progress, but our understanding of it can. And it’s heartening to find filmmakers refreshing traditional techniques to give us powerful experiences.

Just as important, studying how our contemporaries find new possibilities in something as old as crosscutting can encourage ambitious filmmakers today. The menu is open-ended. There’s always something new, and rewarding, to be done.

We had a wonderful time at this year’s Wisconsin Film Festival. Thanks to all the people and institutions involved, and especially the programmers Jim Healy, Mike King, and Ben Reiser. Each year it just gets better.

Wigilia is currently streaming on Amazon. Nocturama has just gotten a US distributor, the enterprising Grasshopper Film.

Good discussions of interlaced plotting in medieval tales are William W. Ryding, Structure in Medieval Narrative (Mouton, 1971) and Carol J. Clover, The Medieval Saga (Cornell University Press, 1982). Yes, it’s Carol “Final Girl” Clover.

For Tarantino’s use of block construction and time-bending, go here. We discuss Nolan’s penchant for crosscutting in this entry and that one, and at greater length in our e-book on his work.

Refutations of the death of cinema, courtesy the VIFF

Maliglutit (Searchers)

Kristin here:

About three weeks ago David pointed out that the “death of cinema” being bewailed by many critics and pundits was based largely on the disappointments of the summer of Hollywood blockbusters. Taking a larger perspective, the cinema looks to be thriving. Herewith some further evidence as we continue to enjoy the rich schedule of screenings at the Vancouver International Film Festival. Some of these films are good, some very good, some perhaps great and destined to be watched for decades to come.

Maliglutit (Searchers)

In 2001 the first Inuit-made feature film, Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner won the Golden Camera at Cannes. Admirers of it, among whom we count ourselves, have wondered whether there would ever be a follow-up. Since Antanarjuat, director Zacharias Kunuk has had an active career in documentaries. Now, however, he has returned with a second fiction feature, Maliglutit (Searchers).

The title proclaims the film’s inspiration: John Ford’s The Searchers. Kunuk wanted to make a western, but one “made entirely the Inuit way.”

From the start, I resolved to anchor the production in my home community of Igloolik. It was important to get the faces right. I brought on Natar Ungalaaq, who played the lead in “Atanarjuat – The Fast Runner,” as co‐director to work with the actors preparing their performances and to mentor a new generation of Inuit filmmakers. Our cast and crew included regular collaborators, but also a number of new people in training.

Igloolik is a small island in the Northwestern Passages, far to the north in Canada. It’s population is about 2000. An extraordinary place for such important films to come from.

Maliglutit can hardly be said to be a remake of Ford’s film. Its borrowing from The Searchers is solely the kidnap plot. The hero is Kuanana, whose wife and daughter are carried off on dogsleds by four members of a neighboring tribe, led by Kupak. Kuanana and his son give chase. Unlike in The Searchers, there is no conflict between the older and younger men. Unlike Ethan Edwards, who is revealed to be hunting down the tribe who kidnapped Debbie in order to perform a sort of honor-killing, Kuanana simply wants the women back. The psychological complexities of The Searchers are replaced by a focus on the details of Inuit life in 1913 (an era in which firearms were starting to replace traditional weapons, above) and the frightening beauty of the bleak late-winter landscapes through which the chase progresses. The two women resist and seek to escape during the entire chase, and they play an active role in the climactic rescue.

Although virtually all of the crew were also local Inuits, producer and cinematographer Jonathan Frantz, was a crucial figure. He created epic images of the harsh, snowy landscapes during the chase (see top), often shot in the early morning light of March.

Maliglutit seems to have no distributor. Watch for it in other festivals and eventually on home video–though the scale of the compositions really demands a big, big screen.

From a textbook to an upheaval

If women directors are still struggling to establish themselves in Hollywood, they are much in evidence here at Vancouver. Films from a wide variety of countries were helmed by women, including Mia Hansen-Løve (or Mia Hansen Love as she is billed here), who won the Silver Bear award for best director at the Berlin International Film Festival and the Bucharest International Film Festival. (See here for an interview with the director shortly after the Berlin premiere.)

Her Things to Come (L’avenir) well demonstrates her mastery of traditional, skillful filmmaking. Her camera is locked down rather than restlessly roaming, with simple reframes to follow actors’ movements. The compositions are impeccable, the editing clearly planned in advance, and the story told in an unobtrusive, clear fashion.

I found the film appealing partly because it presents that rare thing, a plausible depiction of the life of an academic. The heroine, Nathalie, played in another star turn by Isabelle Huppert, teaches philosophy in a Parisian high school. Her students are obviously sophisticated kids, and she finds fulfillment in her work. Her husband is an intellectual, and they have two children. Her life seems ideal and her future certain. In the course of the film, however, she suffers a series of setbacks.

Amusingly, these are initially signaled by a meeting with editors at the publishing house that has brought out her textbook and will be publishing a collection of essays aimed at classroom use. The editors cheerfully show her some garish designs intended to boost sales. Her husband announces that he’s leaving her for another woman, her mother needs to be institutionalized, and she loses her job.

The future is suddenly turned upside down, and the film depicts Nathalie’s efforts to maintain her usual cool, in-control demeanor while seeking a new path in life. Although the film is quite sympathetic to her, there is considerable humor as well. Entertaining, thought-provoking, and visually lovely.

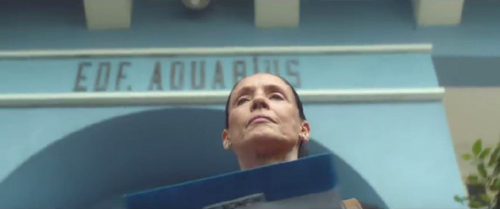

The aging of Aquarius

I was very impressed by Kleber Mendonça Filho’s Neighboring Sounds, shown at the 2012 VIFF. I have been hoping to see another of his films, and this year the festival presented Aquarius. I can’t say that it was quite as exciting as the earlier film, but it is an admirable and entertaining achievement nonetheless.

Again Filho sets his story in his native city of Recife and again the story revolves around predatory real-estate developers building high-rise residences by buying up and bulldozing beautiful old neighborhoods. The earlier film wove together stories of several families living in such a neighborhood, threatened both by criminals and by the encroachment of modern, soulless towers. Aquarius focuses instead on one wealthy dweller in an otherwise empty apartment building, Aquarius.

The one holdout is Clara, a beautiful, wealthy retired music critic in her 60s, who endures various attempts to drive her to sell her apartment. The unscrupulous developers stage a “party” in the empty apartment above her–an orgy and apparent porn shoot. They burn the resulting filthy mattresses in the communal courtyard. They try to catch her in a legal technicality when she has the façade of the building painted, and things only escalate from there.

The film’s effectiveness depends to a considerable extent upon the riveting central performance by Sonia Braga, best known to English-speaking audiences from her lead role in Dona Flore and Her Two Husbands and Kiss of the Spider Woman. A cancer survivor (as demonstrated by Braga when she bares an apparently real mastectomy scar), Clara commands complete sympathy as she fearlessly stands up to her devious persecutors. Despite her wealth, she is friends with her housekeeper and well aware that a short way down the beach across from her apartment, there is a poor neighborhood even more threatened by the developers than hers is.

As in Neighboring Sounds, Filho includes shots of the nearby high-rise blocks looming over the beautiful older buildings. In my earlier entry, linked above, I quoted an interview where the director said, “Architecture gone wrong is a nuisance, but extremely photogenic.” Here the “wrong” architecture is bland, and the older buildings are photogenic.

Aquarius will begin a New York theatrical run on October 21. (Thanks to Erik Luers for the link!)

A poet for, if not of, the people

Another Latin American film shown at the 2012 VIFF that I wrote about favorably was Pablo Larrain’s No. Now he follows up with Neruda. Here we have another film about a poet, in this case the Nobel-prize-winning Chilean author Pablo Neruda. The film follows the dramatic events in 1948 when Neruda’s Communist activities led to a warrant being issued for his arrest. After living in hiding for some months he fled through a mountain pass near Maihue Lake (above) into Argentina and from there to France.

Not surprisingly, many scenes center around Neruda, played powerfully by Luis Gnecco, an actor more typically associated with comedies. (He played the Ricky Gervais/Steve Carrell role in the Chilean version of The Office.) Equally prominent, however, is the police detective who relentlessly pursues Neruda, Óscar Peluchonneau (Gael García Bernal).

Peluchonneau is at once a real detective, a figure fascinated by his quarry, and perhaps a figment of Neruda’s imagination. In a crucial scene, Peluchonnaeau interrogates Neruda’s endless patient and faithful wife (marvelously portrayed by Mercedes Morán; see bottom), and she informs him that he is a mere supporting character invented by her husband. This seems improbable, since Peluchonneau has important causal effects in the narrative, and indeed, his narrating voice continues throughout the film, filtering much of the story information to us. Still, he plays out his supporting role until the end.

I was startled to discover that he and Neruda are parallel protagonists. My Storytelling in the New Hollywood (1999) took Amadeus, Desperately Seeking Susan, and The Hunt for Red October as examples of this fairly rare category. Parallel protagonists largely play out their roles independently, but they are aware of each other and fascinated with each other. One may feel inferior and yearn to be like the other. In Neruda, Peluchonneau is clearly fascinated by Neruda and wishes to be like him. He is, however, far less clever and talented. (Jay Weissberg’s Variety review compares him to Inspector Clouseau.) The ending leaves his status as a character quite ambiguous. It’s nice to know that this unusual option is used in art cinema as well as Hollywood films.

There is a distinct touch of magical realism about Neruda, one that fits in well with the art cinema’s departure from mainstream commercial cinema. It does leave you puzzled in a satisfying way.

Quarrels and cabbage rolls

Don’t ask me what the title Sieranevada means. I have no idea what it has to do with anything that happens in Cristi Puiu’s latest feature. If I had to choose a single favorite from the films I’ve seen so far at the festival, it would be a hard choice between Sieranevada and A Quiet Passion. I have to say, though, that Sieranevada is much funnier, though it took me longer than it should have to figure out that it’s a comedy. Watching the lengthy opening shot, which largely involves the main character’s car being double parked and blocking a DHL truck, I did quickly realize that I was seeing a terrific film.

It is something of a network narrative, based on the familiar situation of a family gathering that exposes long-simmering problems and tensions. (Other examples are Altman’s The Wedding and Vinterberg’s The Celebration.) If we had to pick a central character, it would probably be the medical professional Lary, because we enter and leave the central space when he does, we learn the most about him, and we react much as he does to the amusing twists of action. Still, other family members carry a good deal of the film’s running time, and by the end we observe him with a cooler detachment when his own secrets are revealed.

The main locale is the apartment where Lary’s large family is commemorating his father’s recent death. The apartment has several rooms, all of which are fairly small for the number of people milling about. It’s evidently a set, but one which conveys an entirely convincing sense of seeing an actual cramped apartment.

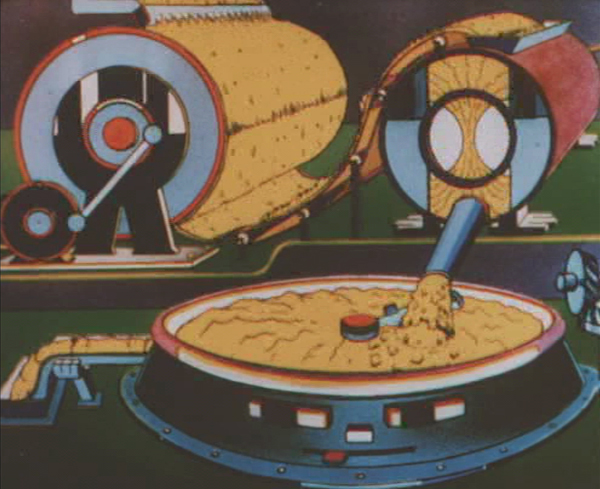

The party is planned to culminate in a substantial dinner. We see the women of the family cooking, setting the long table, inexplicably taking away the unused dishes and utensils, and assembling plates of food wrapped in plastic (above), to be distributed to the neighbors. Few films have made food look so unappetizing. Mainly, though, these people bicker. The party portion of this 173-minute film occupies about 150 minutes, shot in nearly continuous time.

Puiu handles the whole thing in a virtuoso staging of multiple actions going on in different rooms, with the camera often only glimpsing what one group is doing before a door is closed and the camera moves on to catch another group in a another space. Often the camera pans with one character only to change direction as it catches sight of another, as if it continuously seeks out the most interesting bits of action in this densely populated space. Characters air their obsessions: one cousin is a 9/11 conspiracy believer, and an old lady in a white fur hat upsets the others by touting the accomplishments of the Communist past. We hear grievances too, as when the widow’s sister accuses her husband of carrying on an affair with a neighbor.

Scripting the dialogue for this dense weaves of conversations was a considerable accomplishment. Puiu extracts further comedy by putting so much emphasis on the food and then delaying the actual meal for almost the entire duration of the party. First a priest who must perform a memorial ceremony fails to show up, and then a suit which will feature in another ceremony needs emergency alteration when it turns out to be several sizes too large for the hapless young man who must wear it.

In all, despite its three-hour length, Sieranevada is continually entertaining and an extraordinarily assured piece of filmmaking.

U. S. releases: IFC and Sundance Selects have announced Things to Come for 2 December, while Neruda is scheduled to be released for December 16 from The Orchard.

Aquarius was originally expected to be Brazil’s nomination for the best foreign film Oscar, but political controversy has scotched that. There seems to be no prospect of an American theatrical release. Look for it at other festivals and on streaming. So far, Sieranevada seems not to have secured U. S. distribution, but if it does materialize, seek it out in any way you can. It is Romania’s candidate for this year’s foreign-language Academy Award. It would be a well-deserved miracle if it even made it onto the final list of five.

More recent American examples of parallel-protagonist film are Julie & Julia, discussed here, and Public Enemies and Inglourious Basterds, considered here. The first entry also considers an older example, Enchantment (1948).

Neruda (2016).

TONI ERDMANN, GRADUATION: Mediums, well-done

Graduation (Cristian Mungiu, 2016).

DB here:

More from this year’s Vancouver Film Fest, abundant as ever (over 200 features, over 300 films in all).

Comedy, Chaplin supposedly said, is life in long-shot, while tragedy is life in close-up. This is questionable on its face, but put that aside. What about medium shots? Maybe they’re either comic or tragic? Or maybe just neutral? Any shot framing the body from, say, the waist up to the head is the workhorse of most film traditions, and it’s ready to be recruited for almost any purpose.

I was led to think about this handy tool when watching two strong and enjoyable films, Cristian Mungiu’s Graduation and Maren Ade’s Tony Erdmann. Both directors made some similar artistic choices, such as that slightly swaying handheld framing that seems de rigueur in many films nowadays–the “free camera,” as the Danes call it. But the two films show different ways of exploiting the medium-shot of people talking. The differences, I think, depend on both genre factors and one crucially diverging choice.

Screwball comedy with a German accent

Toni Erdmann updates screwball comedy: a mischievous madcap disrupts the staid life of an uptight character s/he loves. In classic Hollywood the madcap might be a wild woman (Bringing Up Baby) or a free-spirited man (Holiday), with romantic union the result. The variation here is that the madcap is a father. Winfried tries through pranks and impersonation to loosen up his rigid daughter Ines, who’s striving to be a cool corporate barracuda.

The plot is a series of encounters in Ines’ high-stress professional life. Her rounds of meetings and cocktail parties are constantly invaded by the bulky Winfried. Sometimes he’s his unkempt self (often adorned with splayed monster teeth), sometimes he’s a fake businessman/diplomat named Toni Erdmann. When father shows up, she’s mortified. She resorts to the classic strategies of the screwball target: flight, pretending not to know him, and desperately going along with the masquerade in hope that it will pass. Finally Winfried breaks down her defenses, and we get the obligatory scenes when the by-the-book character finally lets loose (here, through a heartfelt song and later by a creative effort at party hostessing).

The premise of screwball is a bit of a Jonsonian power trip. We’re asked to sympathize with people who have enough leisure and money to punk everyone around them. The cruelty of the put-on, with trusting characters gulled by free spirits, is built into the genre. In Toni Erdmann we have to be ready to accept not only the deflation of a CEO, which is always fun, but also the terrorization of working stiffs like delivery men and mechanics. To the film’s credit, there is a moment when Winfried learns the price that others must pay for a retiree’s cute mischief. Along the way is some sharp satire on corporate predation and its fashions in “coaching” and “team-building.”

All this is played out in good old medium shots. And those in turn are embedded in good old shot/ reverse-shot.

Toni Erdmann relies on shot/reverse-shot technique primarily, I think, because of the need to show reaction shots. A good part of comedy is reaction, and camera ubiquity allows us to watch the gag and the payoff in a tick-tock editing rhythm. Ade can time people’s responses to Winfried’s sinister leer in ways that maximize the laugh.

Shot/ reverse-shot has of course long been a mainstay of classical Hollywood continuity style, partly because it mimics the flow of turn-taking in conversation. Like side-participants in a real-life situation, we shift our attention from speaker to speaker, thanks to the cuts.

Over-the-shoulder framings help anchor us in the space of the scene, so we always know where we are.

Assisting that sense of stability is the so-called 180-degree system of staging, shooting, and cutting. This keeps all the eyelines, postures, and backgrounds fairly consistent. At several points, though, Ade’s reverse angles “break the line,” shifting us across the axis of action. This creates what’s been called “200-degree-plus” staging and shooting.

Fortunately, our pragmatic sense of who’s talking to (or looking at) whom overrides the slight jump. The shift can be smoothed if there’s a strong cue–as here, when Winfried turns his head from the courier on his doorstep.

When you have several characters present, and you’re willing to break the 180-degree line in your reverse shots, you can cheat positions from shot to shot in remarkable ways. A cut can magically delete a character for the sake of emphasizing another one’s reaction.

For example, at a fancy party, Winfried-as-Toni approaches a woman and claims he works at the German embassy. The first shot favors the woman, her friend, and a nervous Ines, who tries to pull Toni away.

But when we cut to a reverse of Toni, Ines is no longer beside the blonde woman.

She has been shifted to the left–in fact, moved completely offscreen–in order to supply a clear view of Toni. His sharp glance to the left confirms her position.

Cheating shot/ reverse-shot positions is a common tactic of classic continuity filmmaking, and Ade uses it freely. The more characters who crowd in, the more chance to cheat them. In some shots during the big party, Ines is close beside her boyfriend as her boss greets Toni. But in the 180-degree reverse angles the couple gets spread out, with the man pushed offscreen entirely, before a new setup brings them back–and deletes the boss.

It’s remarkable how little we notice these shot-to-shot disparities as long as positions are grossly consistent, and as long as we’re given other things to pay attention to. (Dan Levin has studied filmic “change blindness” experimentally.)

Throughout, Ade’s cutting and camera placement help us enjoy, moment by moment, the shocked, bewildered, and bemused responses to Winfried/Toni’s campaign to humanize Ines.

The case of the missing reverse shot

Change the genre from comedy to drama, though, and minimize editing, and you get something else. You get, for instance, Graduation (Bacalaureat).

Mungiu traces a few tense days in the life of Romeo, a provincial doctor living in a bleak housing flat. His daughter is promised a scholarship if she does brilliant exams, but before she can take the first test she’s assaulted and the trauma threatens to wreck her performance. To protect her, Romeo uses his network of friends to arrange for favorable grades. The scheme precipitates crises with the daughter, her boyfriend, Romeo’s wife, his mistress, and a mysterious attacker.

The film is essentially a set of two-handed dialogues, tracing how the pressure on Romeo builds from day to day and hour to hour. These encounters are filmed mostly in medium shots, as in Toni Erdmann, but with one essential difference. The shots are long takes, and they’re kept fairly stationary—that is, no circling or panning of the camera. Handling some scenes in just a single shot, Mungiu often avoids the shot/reverse-shot cutting we see in Ade’s film.

This choice might seem akin to the virtuoso long takes of Iñárritu in Birdman. But as I tried to show back when, Iñárritu’s long takes actually mimic the patterns and effects of shot/reverse-shot editing. In Birdman, we’re denied nothing because the moving camera always picks up the reaction that would normally be captured in a reverse-angle cut. By contrast, Mungiu doesn’t give us the long-take equivalent of continuity editing; he denies us reaction shots quite stringently.

In The Graduation, characters tend to interact in in lengthy profiled two-shots, not 3/4 reverse angles.

This framing gives us some access to the characters’ emotions. It’s worth mentioning, though, that profile shots aren’t strongly informative about a person’s facial expression. A frown or a smile is more “readable” in the 3/4 framing favored by reverse-angle cuts.

More remarkable, though, are those passages in which Mungiu simply denies us access to Romeo’s facial expressions by pivoting him away from us and denying a reverse shot.

Actors have turned their backs to the audience for a long time in both theatre and film, usually to enhance a gesture, to call attention to another actor, or to delay the revelation of the face. But since the reverse-angle cut is such an ingrained convention, we count on camera ubiquity; we expect to see everything. When characters have their backs to the camera, and the director doesn’t cut to an angle that reveals their reactions, this choice can have powerful narrative effects. It can make the character’s psychology more opaque and mysterious. It can also build suspense as we wait for some clues (in words or gestures) to the character’s response.

The withheld reverse angle, within longish takes, was a prominent tactic in Antonioni’s 1960s style, as in L’Avventura.

Mungiu isn’t quite so flagrant, favoring 3/4 rear view like the over-the-shoulder view of orthodox shot/reverse shots. This will do duty for orthodox POV cutting: We see what Romeo sees but not exactly through his eyes.

The result is to attach us to the protagonist but not in a deeply subjective way, as Hitchcock might with intense optical POV shots. These shots might suggest a perceptual subjectivity–we see what Romeo sees, more or less–we don’t know how he’s reacting. Sometimes, as when he and a colleague inspect an X-ray, we get almost no sense of the reaction, or what they’re reacting to.

In addition, Romeo is a fairly phlegmatic man anyhow; he’s hard to read even facing front.

His failed ambitions and troubled relation to his wife, as well as the mess he’s making of the exam scheme, seem to have given him a fixed, furrowed anxiety. I doubt that even Toni Erdmann could make him smile.

Still, most directors would probably have filmed Romeo driving his daughter to school, from an angle in front of the car, shooting through the windshield. And most directors would have revealed something of his response when, as his scheme unravels, the school principal orders him not to contact him again or come near his house.

Even more striking, at a climactic moment, he’s questioned by two policemen. I don’t have an illustration for you, but we’re perched over his shoulder and watch the two cops–not unsympathetic–explain to him at length the punishment likely headed toward him. We get no chance to see whether his facade cracks even a little. But observing him so often as a solid lump in the foreground or on the edge of the shot gives him, I think, a sort of obdurate resistance that suggests he will resist what’s coming. In these grim circumstances, stubborn stolidity gains a heroic quality.

Other characters, notably his wife and daughter, get framed in ways that allow us to track their emotions. It seems somewhat ironic that the sunniest, most straightforward and untroubled faces we see are those of the class lined up for the graduation picture.

No surprises here. The head-and-shoulders shot gets a lot of its impact from its coordination with other stylistic choices: the decision to cut (or not to cut), the selection of the angle (frontal, or from behind), and the overall tone of the film (grim or light-hearted). There are no general rules. Contra Chaplin, the close-up can be comic, as in Harold Lloyd. The long-shot can be tragic, as in Hou Hsiao-hsien or Edward Yang or Theo Angelopoulos. As with these shot scales, the workhorse medium shot is coordinated with other techniques to achieve its results in different contexts.

Thanks to Michael Barker of Sony Pictures Classics and Greg Compton of Sony Pictures Entertainment for their generous help in preparing this entry. Toni Erdmann is scheduled for U. S. release by Sony for 25 December. Graduation is distributed by IFC in the Sundance Selects collection; no U. S. release date yet announced.

I discuss the blend of cinematic convention and social intelligence elicited by shot/reverse-shot techniques in the essay “Convention, Construction, and Cinematic Vision,” in Poetics of Cinema, 57-82. On the quick information pickup involved in certain facial views, see Vicki Bruce, Tim Valentine, and Alan Baddeley, “The Basis of the 3/4 View Advantage in Face Recognition,” Applied Cognitive Psychology 1 (1987): 109–10; and Robert H. Logie, Alan D. Baddeley, and Muriel M. Woodhead, “Face Recognition, Pose, and Ecological Validity,” Applied Cognitive Psychology 1 (1987): 53–69.

On the 200-degree-plus style in modern film and television, see The Way Hollywood Tells It, 177-179. On change blindness, an earlier blog entry is here. Another entry bearing on the matter, also VIFF-inspired, is “Where did the two-shot go? Here.”

The laconic rear-view shot became a common tactic of modernist cinema. For other examples, you can see this entry on Béla Tarr. But Mizoguchi got there quite a bit earlier.

Toni Erdmann (Maren Ade, 2016).

DVDs and Blu-rays for your letter to Santa

The Cure (1917)

Kristin here:

One occasional feature of our blog has been to point out new releases on DVD and Blu-ray, especially of titles that haven’t gotten much publicity. Some of these are easily available at major sources like Amazon, while others have to be ordered directly from their publishers, often abroad. But if you have a multi-standard player, don’t hold back. Ordering from abroad isn’t as intimidating as it might seem. Many sites have English-language sales pages.

We’ve done a lot of these entries by now. You can find them through the DVD category in the list at the right, but I thought it might be useful to give links to all of them here, with brief indications of what each deals with. Some of the DVDs are probably out of print by now, but in this era of eBay and third-party sellers, one can usually track down such things. Then I’ll give a rundown on some recent releases.

The first was Dispatch from the Land of the Long White Cloud, written when David and I were fellows at the University of Auckland in May, 2007. I discussed some of the DVDs of New Zealand films that I had found in stores there. Some are famous, some obscure.

2008 was either a great year for DVDs or we just had more time to deal with them. On January 18, I posted Tracking down Aardman creatures, a guide to the classic animated films of Nick Park, Peter Lord, and their colleagues at Aardman. At the time it was probably the most complete information one could get on these films. Of course, Aardman has gone on to make other films and TV series, but this was the studio’s golden age. On February 1, I described with two boxed sets dealing with early sound films in All singing! All dancing! All teaching! As the title implies, these are a boon to film teachers, as well as buffs and researchers. In Coming attractions, plus a retrospect (June 6), David discussed the release of Robert Reinert’s very peculiar silent film, Nerven, and in Summer show and tell (July 28, 2008), he briefly dealt with a miscellaneous set of DVDs and books that we discovered during our annual visit to Il Cinema Ritrovato and other destinations. On December 10, in Preserving two masters, I discussed the restored version of Lubitsch’s Das Weib des Pharao (which at that point wasn’t out on DVD) and a Walter Ruttmann set.

2009 was a pretty good year, too. On February 18, I wrote about the Flicker Alley release of Abel Gance’s influential classic La roue, including historical background on the film, in An old-fashioned, sentimental avant-garde film. David took the occasion of of a new Criterion boxed set to summarize the work of the fine Japanese director Shimizu Hiroshi (May 9). On May 21, in Forgotten but not gone: more archival gems on DVD, I described two major boxed sets, one of Lotte Reiniger’s lovely but seldom-seen fairy-tale shorts, and one of early Belgian avant-garde cinema–and yes, the early Belgian avant-garde cinema includes some important titles. On August 2, David again caught up with the mixed batch of DVDs and books picked up in Europe over the summer or sitting in the stack of mail upon his return, in Picks from the pile. Finally, on November 9 I discussed the British release of Dreyer’s Vampyr with a very worth-while commentary track by Guillermo del Toro, who said, among other things, “I am not Carl Dreyer, and I should shut up.”

In February of 2010, I wrote DVDs for these long winter evenings, dealing with three sets with the work of three crucial filmmakers: Georges Méliès, Ernst Lubitsch (most of the German features), and Dziga Vertov. In October, it was More revelations of film history on DVD: a documentary on Veit Harlan, a new series of Soviet silent films, and the Flicker Alley set of Chaplin’s Keystone films. (For the follow-up, see below.) On November 28, Silents nights: DVD stocking-stuffers for those long winter evenings covered little-known Norwegian and Danish silents, a rare Expressionist film, Ford’s The Iron Horse, hilarious Max Davidson comedies, and the Kalem company.

For some reason it was a full year before we posted more DVD coverage in our second Christmas-gift-themed entry, Classics on DVD and Blu-ray, in time for a fröliche Weihnachten! (November 29, 2012). It probably took us that long to get through all the discs we picked up in Bologna and elsewhere. The title reflects the heavily German coverage: early Asta Nielsen films, Pabst’s first feature, the release of Das Weib des Pharao on DVD and Blu-ray, as well as the 1939 Hollywood version of The Mikado.

Earlier this year, on June 20, we posted our most recent DVD/Blu-ray entry, Recovered, discovered, and restored: DVDs, Blu-rays, and a book. It deals with a burst of releases of Norwegian silent films, a new entry in the “American Treasures” archive series, and some American films, famous and obscure.

Now more DVDs are piling up, and the time seems ripe for a third set of holiday-present suggestions, to give or hope to receive.

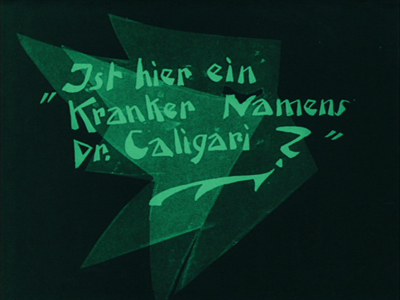

Caligari, restored at last

In our survey of the ten best films of 1920, I mentioned that Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari was one of the films that lured me into film studies during my undergraduate days. I know it very well. I was tempted to go to one of the screenings of the recent restoration this year at Il Cinema Ritrovato, but it was opposite other films I had never seen before, so I passed it up. Luckily now Kino Lorber has brought that restoration out on DVD and Blu-ray (sold separately).

The negative of Caligari does not survive in its entirety, but the restoration has taken the usual steps to fill it in and provide authentic tinting. The information comes from titles at the beginning of the DVD print:

The 4K restoration was created by the Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung in Wiesbaden from the original camera negative held at the Bundesarchiv-Filmarchiv in Berlin. The first reel of the camera negative is missing and was completed from different prints. Jump cuts and missing frames in 67 shots were completed by different prints.

A German distribution print is not existing. Basis for the colours were two nitrate prints from Latin America, which represent the earliest surviving prints. They are today at the Filmmuseum Düsseldorf and the Cineteca di Bologna.

The intertitles were resumed from the flashtitles in the camera negative and a 16mm print from 1935 from the Deutsche Kinematek-Museum für Film und Fernsehen in Berlin.

The digital image restoration was carried out by L’Immagine Ritrovata-Film Convservation and Restoration in Bologna.

The images are definitely clearer, with more detail visible than in prints I have seen before, and the film runs more smoothly. An inauthentic intertitle has been removed. In most prints, when the grumpy town clerk hears that Caligari wants a permit to exhibit a somnabulist, he calls him a “Fakir” and turns him over to his underlings to deal with. That title is now gone, and it’s clear that Caligari is annoyed at the man’s disdainful attitude rather than a specific insult. The intertitles have their original jagged, Expressionistic graphic design (see above) rather than the plain backgrounds used in many prints hitherto available.

There are optional English subtitles. The modernist musical track fits well with the film.

The supplements include a short essay which I provided and a documentary, Caligari: How Horror Came to the Cinema. The restoration is also available from Eureka! in the United Kingdom, with a different set of supplements and with DVD and Blu-ray sold together.

Flooded by flickers

If you want a lot of good laughs and have 1005 minutes to spare, Flicker Alley’s “The Mack Sennett Collection Volume One” offers 50 restored shorts which Sennett acted in, wrote, directed, and/or produced. (This 3-disc set is available only on Blu-ray.)

The films are presented in chronological order, starting with a 1909 comic short directed by D. W. Griffith at American Biograph and starring Sennett, The Curtain Pole. Two comedies directed by Sennett at American Biograph follow. In 1912 he founded Keystone, represented starting with The Water Nymph (1912) and ending with A Lover’s Lost Control (1915). In 1915 Sennett became one of the three points in the Triangle Film Corporation, along with co-founders Griffith and Thomas Ince. Keystone continued operating as Triangle Keystone, and films from that production unit from 1915 to 1917 are included. At that point Sennett went independent as Mack Sennett Comedies, making mainly two-reelers, beginning in this collection with Hearts and Flowers (1919) and running to The Fatal Glass of Beer (1933). See here for a complete list of titles. Each of the three discs contains a group of films as well as a set of bonuses at the end.

Sennett built a team of excellent comedians, including at various points Ben Turpin, Chester Conklin, Charlie Chaplin, Ford Sterling, Wallace Beery, Louise Fazenda, Mabel Normand, and others. The action typically moves at a breakneck pace, and the editing is similarly fast. Being able to go back and watch some of these routines again, perhaps in slow motion, is ideal for making sure you catch every throw-away gag.

A Clever Dummy shows off the dexterity of the cross-eyed Turpin. Two inventors build a mechanical dummy, modeling “him” on the janitor played by Turpin. At first the dummy is a rather cheap-looking fake, but Turpin plays him in some scenes and the janitor in others. Then he decides to masquerade as the dummy, and his antics persuade some vaudeville agents to buy him for their show (left below). Once in the theater, he defies a stagehand’s (Conklin) efforts to make him stand quietly (right):

Savor these a few at a time, and you’ll have entertainment for months to come.

Of course, some of that 1005-minute total comes in the bonuses. There are newsreel and television appearances by Sennett, including “This Is Your Life, Mack Sennett” (1954) and a half-hour radio appearance on the Texaco Star Theater in 1939.

Back in 2007, we posted an entry called Happy Birthday, Classical Cinema!, where we explained how the guidelines and techniques that came to underpin what we now call classical Hollywood cinema came together in 1917. At the end we offered a list of the ten best films of that year, and thus inadvertently our annual ninety-year celebration, “The ten best films of …” came into being. On it were two Charlie Chaplin films, The Immigrant and Easy Street.

They were both made during the third phase of Chaplin’s career, when he had left Keystone and gone first to Essanay and then to Mutual. Those who find the pathos in many of Chaplin’s films from the 1920s onward might plausibly consider his Mutual period to be the height of his career. The twelve films are not all equally brilliant, however. One watches Chaplin developing a better sense of story-telling to go with the slapstick. The Rink comes across as two one-reelers stitched together. In the first half having Charlie does a fairly conventional waiter schtick, but when he visits a rink on his lunch-hour, the films moves into high gear as he performs a dazzling set of moves on skates:

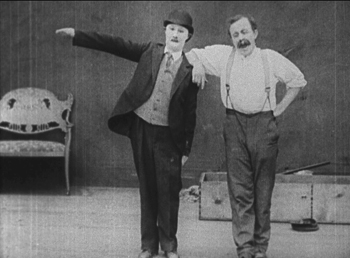

Other films show Chaplin learning to make a sustained, tight story built of non-stop gags, none more skillfully than The Cure. An alcoholic forced into a sanatorium evades all attempts to make him shape up while charmingly defending the heroine from an offensive, gout-ridden villain (see top, where all involved briefly strike a pose).

Flicker Alley has released a steelbox commemorative set of five discs, two Blu-ray and three DVD, to celebrate the centenary of Chaplin’s first appearance as the Little Tramp–though of course that appearance had been made at Keystone.

For a list of film titles and bonus features, see here.

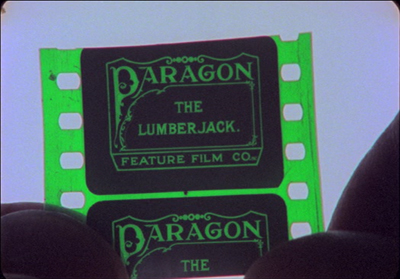

If these sets contain some of the most famous films and performers of their day, another recent Flicker Alley release, We’re in the Movies: Palace of Silents & Itinerant Filmmaking, turns to some of forgotten and obscure offerings of the silent era: films made in small towns by independent regional producers, using local citizens for their casts. Earlier this year, David wrote about Wheat and Tares, a 1915 film made in his home town by the Penn Yan Film Corporation. That’s not one of the locally made films included in We’re in the Movies, but this two-disc set (both DVD and Blu-ray) does contain The Lumberjack, a short film made in Wausau, Wisconsin and discovered in the early 1980s by Stephen Schaller, then a graduate student in film studies here at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Schaller didn’t just discover the film. He created a lovely, poignant documentary, When You wore a Tulip and I Wore a Big Red Rose (1983), about the making of the film and the history of the one print and how it survived. He tracked down and interviewed several elderly people who had been involved with its making. These included Florence Gilbert Evans, the only surviving cast member, and relatives and friends of others “actors.” At intervals throughout the film, he interviews Louise Elster, who had accompanied silent films on piano in local theaters. She provides a lively commentary on such accompaniments and plays examples as skillfully as she must have done in the day. (Modern-day silent-film accompanists might find many tips from this documentary.)

The only problem with the film is that no identifying titles are superimposed to tell us who these people are, and often their names are not mentioned in the interview excerpts included. One has to struggle at times to figure out who the speakers are and what they had to do with The Lumberjack. Names are only given in the final credits, and even then their connections to the film are not specified. Still, the story of the film’s making comes together clearly enough.

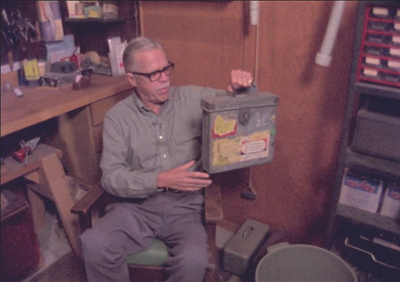

Schaller reenacts the finding of the film itself in a scene with Robert S. Hagge. Hagge, who apparently worked at the Grand Theater, where the sole print resided until 1946, when he took it to his home:

The poignancy of The Lumberjack‘s history emerges gradually as we get to know those involved and their histories. One of the producers was accidentally killed during a quarry explosion staged for the film. Settings shown in the movie are compared with the current appearances of the same places, with some beautiful old buildings preserved and others replaced by bland modern structures. There is a hint that the making of the film created an excitement that transformed the lives of the Wausau citizens involved. When You Wore a Tulip and I Wore a Big Red Rose illustrates the power of even the most modest of films and the inevitable losses caused by the passage of time.

The set also includes a 2010 documentary, Palace of Silents: The Silent Movie Theater in Los Angeles, devoted to a theater built in 1942 and dedicated for over 68 years to showing silent films. The rest of the contents are The Lumberjack and other early local films.

These films strike me as an excellent way of intriguing students and film fans about the silent era of the movies.

Oktoberfest as seen through the movies

I was somewhat surprised to see the new two-DVD set in the Filmmuseum München series: Oktoberfest München 1910-1980. It’s an interesting approach, gathering together the surviving films about a single annual event, Munich’s famous Oktoberfest. As the accompanying booklet points out, the Oktoberfest was a venue where early traveling exhibitors set up their tents to show movies, though little documentation of these shows survives. No one knows when the first films about or set at the festival were made. The earliest one to survive is from 1910.

Oktoberfest was and is more than beer-drinking. There are parades, rides, and various fairground activities as well.

To many film historians, one of the attractions of this collection will be a film starring the comedian Karl Valentin, Valentin auf der Festwiese. The nominal plot involves Valentin taking his wife to the festival while planning to meet his mistress there and sneak away. This story gets shunted aside for most of the film’s length, however, as the couple wander through various sideshow tents. We see their grotesque reflections in a fun-house mirror (above), and the camera perches in a ferris-wheel seat to record the long-delayed confrontation of wife and mistress.

One curiosity of the set is a 3D film from 1954, Plastischer Wies’n-Bummel. The analglyph 3D glasses (red and cyan) required for the effect are included in the set. I found it something of an effort to resolve the 3D in many shots, but there are some dramatic depth effects involving balloons and some fairground swings that work quite well:

The booklet is in German, English, and French, and there are optional subtitles in English and French. The DVD set can be ordered online here.

Making a list, Czeching it twice

When we were in Prague this summer, Michal Bregant, head of the National Film Archive, gave us some books and DVDs related to early Czech animation.

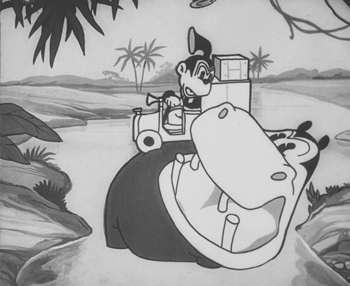

One was a catalog published by the archive, Czech Animated Film I 1920-1945 (2012, bilingual in Czech and English), with a short historical introduction and descriptions of all the known films of the period. It relates to a two-DVD set, Český animovaný film 1925-1945 (Czech animated film). This delightful collection contains 30 shorts and has optional English subtitles. Some of the cartoons are outright imitations of American series of the day, such as Hannibal in the Virgin Forest (1932), clearly inspired by early sound cartoons from Disney and Warner Bros.:

There are also two early György Pál (later aka George Pal) cartoons. Many of the shorts, though, are advertisements. As in other countries where major filmmakerss like Len Lye were doing inventive work for ads, Czech animators came up with some amazing images. Margarine never looked as good as in Irena and Karel Dodal’s 1937 Gasparcolour short for the Sana brand, The Unforgettable Poster (see bottom).

The Dodals were the most important Czech animators of this era, as is shown in a well-illustrated biography, The Dodals: Pioneers of Czech Animated Film, by Eva Strusková (published by the National Film Archive in 2013). It’s in English and comes with a DVD. (There is some overlap between its contents and those of the two-disc set.)

Both are musts for animation experts and fans. The Dodals is available from Amazon. The DVD set won as “Best Re-discovery 2012/13” at the Il Cinema Ritrovato awards last year. It and the catalog can be ordered directly from the National Film Archive website or from a specialized cinema shop in Prague, Terry Posters (this link takes you to the English-language version of the site).

The Unforgettable Poster (1937)