Archive for the 'National cinemas: France' Category

The ten best films of … 1932

Shanghai Express.

Kristin here–

The year draws to a close, and the internet abounds with lists by professional critics, educated fans, and clueless people proffering opinions on the ten best films of 2022. David and I avoid this custom, but fifteen years ago I stumbled into a habit of listing the ten best films of ninety years ago. Such films have by now stood the test of time, and they have one enormous advantage: no one is speculating about many Oscar nominations each will get.

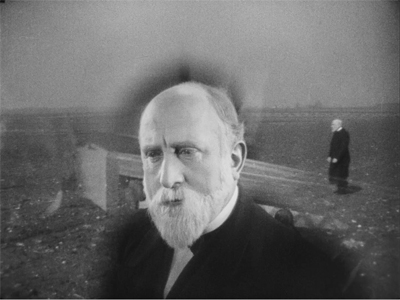

Back in the day, only two of the films on my list got nominated at all, and those two collected a total of three Oscars. (For a hint at one winner, see the image at the top. He will feature prominently in this year’s list.)

These ten films are of course my own choices, and for those who disagree, they are quite welcome to make their own lists.

As usual, my list is a mix of very familiar titles and some not so familiar ones. My hope is to call attention to unfamiliar films that are well worth a look. Actually this year nine of the films should be familiar to any serious film student or fan, but the tenth is a masterpiece that deserves to be rescued from obscurity.

Most historians seem to agree that 1932 was the year when Hollywood emerged from the difficult transition to sound and made polished movies that regained the fluidity of cinematography, staging, and editing that had been lost to some extent. In The Classical Hollywood Cinema, Janet Staiger, David, and I proposed that the transitional period lasted from 1928 to 1931.

The same was not internationally true, however. My list contains one silent film, since the Japanese industry went through a considerably longer transition. No wonder that half of this year’s list atypically consists of Hollywood movies.

Previous entries can be found here: 1917, 1918, 1919, 1920, 1921, 1922, 1923, 1924, 1925, 1926, 1927, 1928, 1929, 1930, and 1931.

As usual, I’ll try to point readers toward the best available Blu-rays or DVDs. Those who prefer streaming should be able to find these titles for themselves. David and I prefer discs, at least for important films. With the decline of access t0 35mm and 16mm prints, studying films closely has become more dependent on discs (which also still have better quality images than streaming). Eventually, with streaming the only option obtaining frame grabs of the sort that illustrate these entries, close film analysis will become extremely difficult.

Hooray for Hollywood!

Trouble in Paradise

Ernst Lubitsch is one of the best-loved of film directors, both within the film industry and among cinephiles. I was lucky enough to be invited to teach a one-month summer course at the University of Stockholm on any topic related to silent cinema. I jumped at the chance to follow up on a vaguely planned project on Lubitsch, specifically a comparison of his German and American silent films. The course became a book, Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood, now out of print but available through open access.

Trouble in Paradise is widely considered his best film, though I would say that at least Lady Windermere’s Fan and The Shop around the Corner are equal to it and others are not far behind.

The witty script is a model of sophisticated humor, and the casting is perfect. Herbert Marshall for a change got to play the suave hero, a dazzlingly expert crook who teams up romantically with Miriam Hopkins, his match as a wily pickpocket. In this 82-minute film, their hilarious courtship in a Venice hotel runs for a remarkable 17 minutes as they top each other in stealing things from each other, with her returning his watch and his flaunting her garter:

It doesn’t seem a minute too long. Essence of Lubitsch.

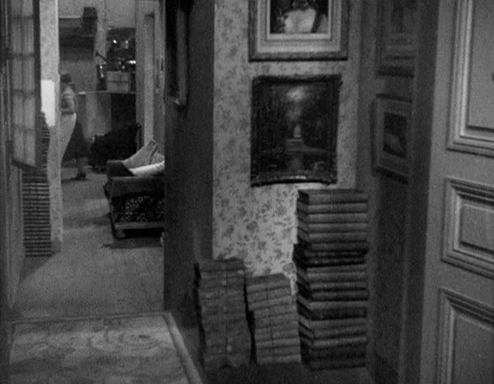

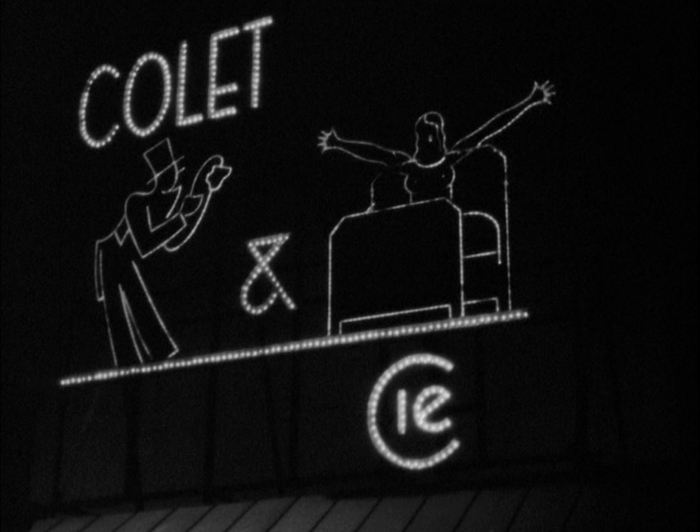

Kay Francis provides the potential trouble that threatens their idyllic life of thievery; she’s a beyond-wealthy owner of perfumery Colet & Cie. (see bottom)–so wealthy that she doesn’t really mind that her “secretary” may be a famous criminal worming his way into her confidence. Charles Ruggles and especially Edward Everett Horton provide hilarity as hopeless suitors wooing Madame Colet.

The comedy is played out in shining art-deco sets (above), lit with perfect three-point Hollywood lighting. As I demonstrate in my book, Lubitsch moved effortlessly from being the master of German silent film style to being the master of Hollywood style. It shows in every aspect of Trouble in Paradise.

The Criterion Collection DVD is still available.

Shanghai Express

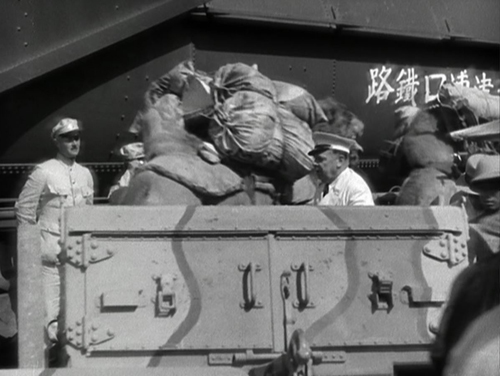

The Josef von Sternberg/Marlene Dietrich teaming. The Blue Angel, featured on my list in 1930. The pair famously made a series of Hollywood films together, all built around the glamor of Dietrich. For me, the best of the bunch is Shanghai Express. It has a stronger script than the others, being set on a train traveling from Beijing to Shanghai during the Chinese Civil War (which had started in 1927). The device of a group on a journey lends the film both unity and suspense. It’s basically a thriller with a romance included. There are more characters than in some of the other Dietrich films, the typical bunch of eccentrics for such journey-plots lending interest, humor, and pathos along the way. Dietrich’s character is strong and likeable. She pursues the man she loves, but on her own terms while he stands around cluelessly keeping his upper lip stiff.

Then there are the incredible visuals. The set design is even more dense than usual for a von Sternberg film. The train windows, both exterior (top) and interior (above) are used brilliantly, and the rebel headquarters where the group is trapped for much of the second half has hanging gauze and stairways that create a complete contrast with the train scenes.

And the Oscar mentioned above went to … Lee Garmes, whose five films in 1932 also included Scarface (see below). Apart from his photography of the settings, he shows off with with other dazzling moments, including an extraordinary tracking shot following an official along the crowded platform for nearly the entire length of the train.

Needless to say, the glamor shots of Dietrich are among the most beautiful ever (Garmes also shot Morocco and Dishonored).

In general, the train station scenes are spectacular and give a remarkable sense of authenticity. Speaking of which, all the extras and minor characters seem to be played by Chinese, or at least Asian people. Anna May Wong has a prominent role as Hui Fei. Whether casting Warner Oland as the rebel leader Henry Chang would count today as “whitewashing” is up for debate. He was born in Sweden but claimed some Mongolian ancestry (so far unproven).

The Criterion Collection has the set of six Dietrich/von Sternberg films on Blu-ray and DVD. (My frames were pulled from an old TCM DVD pairing the film with Dishonored. TCM now offers Shanghai Express by itself on DVD or Blu-ray.)

A Farewell to Arms

The second Oscar-winner of the three mentioned above was Charles Lang, for his cinematography of A Farewell to Arms. (The film also won the third Oscar, for sound recording.)

Frank Borzage has been a staple of these ten-best lists, with Lazybones (1925), 7th Heaven (1927), and Lucky Star (1929). This may be his final appearance in these year-end lists, with growing competition internationally.

A Farewell to Arms adapts Hemingway’s novel of World War I. Gary Cooper plays Frederic, an ambulance medic who spends his spare time drinking and visiting brothels with his friend, Italian Dr. Rinaldi (Adophe Menjou). He meets Catherine, a nurse, at a party, and they fall immediately in love, succumbing to passion under the assumption that war’s uncertainties may not give them another chance. Becoming pregnant, Catherine departs for Switzerland to have the baby, but her letters to Frederic and his to her, are returned to sender. Frederic risks a firing squad by deserting and desperately trying to find her.

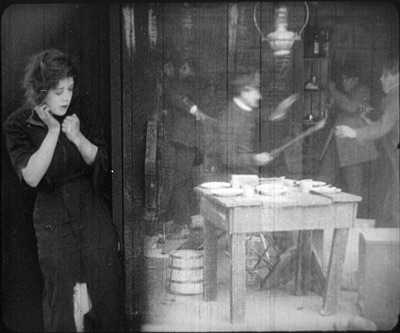

Like Trouble in Paradise and other 1932 films, A Farewell to Arms benefited from the fact that the self-censorship Hollywood studios instituted under the Production Code (aka the “Hays code”) in 1933 was not yet in force. The result is a grittier and more honest look at life in wartime than would be possible in later years. Apart from the quite restrained brothel scene (above), there is considerable emphasis on the forbidden unwed motherhood rife among the nurses Catherine works with.

The two stars make a convincing romantic couple of the kind Borzage had become famous for, and the cinematography is lovely. Lang, too, was an expert at creating glamorous images.

Amazon would very much like you to watch the film for free with ads or with a subscription to Paramount+ or with a free Fandor trial or by paying $2.99. Once you scroll past those enticements, you can find Kino Classics release of a Blu-ray or DVD in a remastered version by George Eastman House. It seems a bit overly dark to me, but maybe the original nitrate copy was, too.

Scarface

I have to admit that gangster films are not my favorites. Still, there are outstanding films in the genre, as the presence of von Sternberg’s Underworld on my 1927 list indicates. The early 1930s established the genre solidly, and Scarface stands out among the other classics examples of the time. I have not seen the two other such classics still commonly watched, Public Enemy or Little Caesar, for a very long time, but I recall not being very impressed.

Scarface marks Howard Hawks’s first appearance on one of my lists. It’s not up to his greatest films of the 1930s, Twentieth Century and Only Angels Have Wings (and some would say Bringing Up Baby).

One thing that makes Scarface stand out for me is its considerable use of humor, which seems unusual for a gangster film. Paul Muni, so dignified in his prestigious bio-pics of this same period, lets go and struts with aggressive arrogance, lets go in fits of rage, and makes Tony Camonte a figure of fun with his accent (“That’s putty nice”) and flaunted ignorance. When the woman he’s trying to impress and seduce remarks sarcastically that his clothes are gaudy, he delightedly takes it as a compliment.

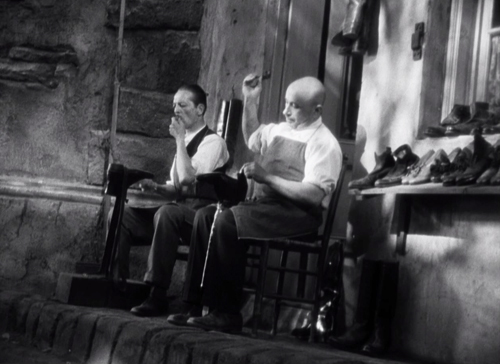

The comic relief flirts with slapstick in the figure of Camonte’s “secretary,” who is illiterate, inept, and downright stupid. According to the AFI Catalog, his character name is Angelo, though Camonte addresses him as Dope. There’s a running gag of him being unable to get basic information from callers. At one point during a raging gunfight in a restaurant, he struggles to hear a caller’s name, unaware that a tank behind him has been pierced and is dousing him.

The film also has its visual pleasures. It was one of five films, along with Shanghai Express, that Lee Garmes lensed in 1932. The cinematography is appropriately less glamorous than in Shanghai Express, but it’s dark and occasionally beautiful, as in the hospital-invasion scene at the top of this section.

Many films of the early 1930s start off with an impressive moving-camera shot, presumably to show off before settling down into scenes with standard continuity cutting. Scarface has quite an impressive opening, with a plan sequence leading up to the first act of violence.

It begins with a low angle of a streetlight going out, and then tilts down and tracks rightward past a milk delivery cart and a sign that establishes the locale.

Continuing rightward, it reaches a tired janitor who removes a sign informing us that a stag party had been held there the night before. The camera tracks rights as he starts to clean up.

The camera follows through the wall and continues as he tackles the job in a room festooned with streamers–possibly an homage to the big party scene in Underworld. One artifact of the party that he finds is a brassiere that has lost its owner.

As he pauses, the camera leaves him to pan right and track in on a gang boss and two of his men talking about a potential danger from a rival gangster. He declares that he doesn’t want war and is satisfied with the money he’s making.

The men stand, and the boss promises an even bigger party in a week. Thus for a gangster, he seems a decent sort, not willing to stir up violence against those seeking to invade his territory.

The men leave, and the camera follows the boss across the room and into a phone booth. He starts to make a call.

The camera glides past him and away off to the right, where it picks up a menacing shadow in the next room.

It follows the silhouette as the unknown man walks toward the corridor where the phone booth is. Silhouetted against a translucent window, he pulls a gun, fires it, polishes it with a handkerchief, and throws it on the floor. (This sort of offscreen or partially offscreen treatment allows the violence to be less explicit, a ploy that continues throughout the film.)

As the killer disappears, the camera tracks back to the left, revealing the boss’s body. The janitor enters, sees it, takes off his work clothes, and tosses them in the phone booth.

The scene ends with a pan left to follow the janitor as he hurriedly moves through the mess and leaves.

My frames were pulled from the Universal Cinema Classics DVD, a release which has since come out on Blu-ray. (Amazon still has the same edition on VHS!)

Love Me Tonight

So many of the early 1930s musicals were stagey. The review musicals were series of numbers without a connective narrative (convenient because they could be popular abroad without dubbing or subtitling) or backstage musicals where a “put on a show” premise also led to numbers on a stage. But with the growing freedom of the camera and editing, the musical could become something more.

Love Me Tonight feels like a wildly enthusiastic celebration of that new freedom. The story is a modern Ruritanian romance. A Parisian tailor, played by Maurice Chevalier, travels to a country chateau to collect money owed him by a client, who is a member of the aristocracy. While on his way, Maurice bumps into the debtor’s sister, Princess Jeanette, and falls in love with her without realizing who she is. Once at the chateau, he is mistaken for a Baron and proceeds to charm the Princess’ entire family and gain her love–until his lowly birth is discovered. Throughout, the dialogue is witty and the music and songs, by Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart.

Much of the high spirits of the film arise from the fact that the songs are not sung by one or two people in a single locale. Instead, the music starts out in this limited way but passes along to other characters, spreading infectiously through a household or across a countryside. The process begins on a morning in Paris, as the city wakes up and goes to work. Gradually the rhythmic sounds of various activities build up to a symphony made of sound effects: a woman’s broom against a pavement or two cobblers’ hammers striking in counterpoint.

The first actual music when a man getting married that day picks up his formal outfit and Maurice sings about his work in “Isn’t It Romantic?” The groom goes out singing it, and it passes to a taxi-driver and then his fare–who happens to be a composer. Cut to a train, where he hums the music and writes it down (top of section), overheard by a group of soldiers; cut to a field where they march along singing it, and so on, until we reach the chateau and are introduced to the Princess, also bursting into “Isn’t It Romantic?”

Upon meeting Jeanette, Maurice woos her by singing “Mimi” to her. Here it’s a straightforward solo, though one that is filmed in an unusual fashion with Maurice singing and Jeanette reacting in shot/reverse shot directly into the camera.

Once at the chateau, Maurice apparently sings the infectious “Mimi” for the family and guests since there is a montage moving among them as they all cheerfully warble the song in their respective rooms. The same thing happens still later, when Maurice’s low birth is discovered; the song “The Son of a Gun Is Nothing but a Tailor,” similarly spreads throughout the building, including to the servants, who show a snobbery equal to that of their masters. Who can resist lyrics like those sung by a washerwoman?

Down upon my hand and knees/Washing out his BVDs/Is a job that hardly please me./If I had known I would have tore/The buttons off his panties for/The son of a gun is nothing but a tailor!

Overall one gets a sense that music and singing are irrepressible and ripple outward from the soloists to infect everyone within hearing distance.

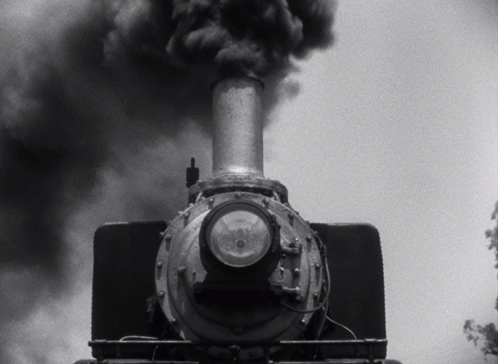

Of course once Maurice has been thrown out, Jeanette decides to defy her family and races after his train on horseback. Mamoulian throws in some Soviet-style compositions as she heroically stands on the tracks and forces the train to stop.

Apart from its infectious style and music, Love Me Tonight has a wonderful cast, with Charles Butterworth as Jeanette’s wimpy but titled suitor, Charles Ruggles as the debtor son, Myna Loy as the man-hungry younger sister, and C. Aubrey Smith as the curmudgeonly father who becomes downright jolly under Maurice’s influence. Sheer entertainment.

Love Me Tonight is available from Kino Lorber on DVD or Blu-ray.

Hooray for the Rest of the World!

Vampyr

Two masters of cinema made vampire films a decade apart. I dealt with Murnau’s Nosferatu in the 1922 entry.

The two films could hardly be more different from each other. Murnau’s film was a plagiarized version of Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel, Dracula. He followed the original very loosely, cutting out most of the characters, including Van Helsing and hence the entire lengthy investigation process. Dreyer may well have known Murnau’s film, but it is hard to detect any influence or inspiration apart from the use of a book as exposition. The Universal version starring Bela Legosi was still in production when Dreyer finished shooting Vampyr. Instead, Dreyer drew even more loosely from the collection of horror-fantasy series short stories by Sheridan Le Fanu, published as In a Glass Darkly (1872).

Dreyer seems to have taken a few ideas from the stories, but does not use the narratives associated with those ideas. The notion of a female vampire is probably derived from one of the stories, “Carmilla,” though Le Fanu’s vampire is young and beautiful, while Dreyer’s is an elderly woman, Marguerite Chopin. The collection of stories is presented as having been case studies collected by a Dr. Hesselius, a researcher of the arcane. Allan Gray may be inspired by Hesselius, though he does no evident research and reacts in fear in most cases where he encounters anything strange and grotesque. Gray’s dream of being trapped in a coffin and carried off to be buried comes from “The Room in the Dragon Volant.”

On the whole, though, one of the most striking things about Vampyr is how little it adheres to the conventions of the vampire tale. It is not told as a collection of documents, as are Le Fanu’s stories (“Carmilla”is told in first person by Laura, the heroine and victim of the vampire) and Dracula (a collection of documentation by gathered by several characters). As in Nosferatu, a book is included to help present the “rules” of vampire stories, but the book is not written by Gray. It is given to him by the old Chatelain. The premises that vampires must travel in coffins full of dirt or will be killed if exposed to sunlight, so important in Nosferatu, are ignored here. Actually, the intention seems to be that Chopin is active mainly at night, but since the entire film was shot in murky daylight, it’s difficult to to tell night from day. Vampires also tend to be of noble birth, and we usually find out something about their family history. Chopin seems to be a local woman who somehow became a vampire.

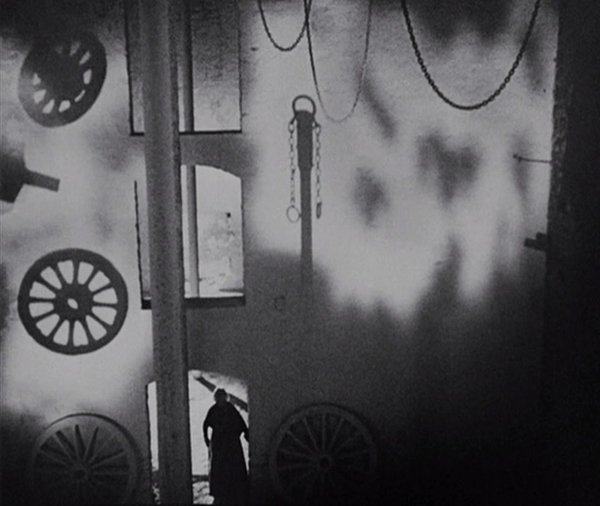

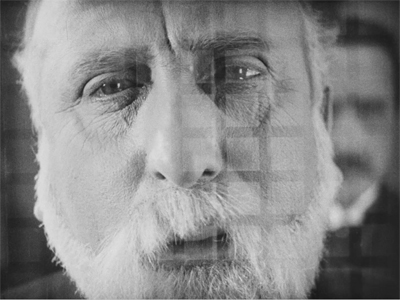

To create a creepy atmosphere, Dreyer has Gray wander about observing menacing, unnatural, or unexplained phenomena in the neighborhood of the village of Courtempierre. These are not phenomena conventional to vampire stories, so they seem as mysterious to us as to Gray. Much of what Gray observes is never explains. Gray sees numerous shadows and reflections of beings who are not visible. He follows the shadow of a peg-leg man until it finally rejoins the soldier who should be casting it. Most vampires live in crumbling Gothic castles, but Chopin seems to have made her headquarters in a dilapidated factory of some sort. (Dreyer chose a deserted plaster factory whose white walls would show off the shadows cast on them.) Her main minions, a sinister doctor and the one-legged military man apparently do whatever they do there, waiting to do her bidding. As the images above and on the right below show, Dreyer creates a mysterious air to the building through the circles and curves of large gears, wheels, and hanging chains.

Beyond such motifs, there are the actors’ unpredictable exits and entrances into the frame during camera movement and the eerie offscreen sounds that hint at something disturbing happening nearby. David has analyzed all this in detail in his book, The Films of Carl-Theodor Dreyer (out of print but available from second-hand book dealers).

For the ending, Dreyer draws upon the convention of a stake through the heart as the way to kill a vampire. It isn’t Gray that figures this out. A remarkably passive protagonist, he sits dreaming of being buried alive while the old servant, initially a minor character, reads the Chatelain’s book, gathers the needed equipment, and initiates the task of the staking of the vampire in her grave.

The 1998 restored version of the film is available from The Criterion Collection on DVD or Blu-ray, with a particularly good set of supplements. These include a visual essay by Danish expert Caspar Tybjerg that deals in more detail with the influences of previous vampire literature and films on Dreyer’s work; I have drawn upon it for some of the information above. Vampyr also streams on The Criterion Channel, accompanied by some of these supplements as well as a video essay by David, “Vampyr: The Genre Film as Experimental Film.”

Boudu Saved from Drowning

Jean Renoir entered this list in 1931 with La Chienne. Although a grim melodrama for the most part, the film provides put-upon accountant Maurice Legrand with a happy ending as he leaves home and becomes a jovial tramp.

Boudu, the self-centered, careless tramp at the center of this film, is presumably not Legrand, despite being played by the same actor, Michael Simon, and Boudu Saved from Drowning is not a sequel. It almost could be, but this time the genre is comedy.

The opening sets Boudu up as an unusual tramp. He is not begging, and when a little girl offers him a small bill, he asks what it is for. “To buy bread,” she replies. Soon Boudu does beg by opening a car door for a rich man, and when the man can’t find any money in his pockets to tip him, Boudu hands him the small bill “To buy bread” and walks away.

Unexpectedly, Boudu jumps into the river in a suicide attempt. Lestingois, a prosperous bookseller whose shop and apartment are across the street, witnesses this and rushes out to dive in and save Boudu. He succeeds, receiving praise from the onlookers as a bourgeois who would take this trouble for a mere tramp. Lestingois is fascinated and amused by this “perfect tramp” and takes him in, offering him dry clothes, food, and a sofa to sleep on for the night, much to the disgust of his wife.

Boudu’s antics delight Lestingois, who treats him somewhat like a pet dog (top of section). He also gives Boudu a lottery ticket, which predictably will become a vital plot device later on. The tramp, however, disrupts the routine of the household–in particular sleeping in a spot that prevents Lestingois from making his nightly visits to the maid Anne-Marie.

Boudu lingers on, seeing this cushy home as a good setup; he tries to fit in by shaving his bushy beard and trying to dress respectably. He is utterly uncouth, however, shining his shoes on the wife’s bedspread, and knocking things off shelves, and causing a flood by leaving water running in the kitchen. Lestingois ultimately gets fed up with him–but in the nick of time Boudu wins the lottery and the attitude of the household changes. Anne-Marie, who supposedly loves Lestingois, suddenly becomes engaged to him.

On the wedding day, however, as the happy couple are in a rowboat on the river, Boudu upsets the boat and floats away to resume his old life as a tramp.

Stylistically the film is distinctly Renoirian. He shot his exteriors in Paris streets and parks, seemingly concealing the camera in some cases. A telephoto lens captures Boudu wandering along the bookstalls on the banks of the Seine, with the other people presumably ignoring him as a real tramp.

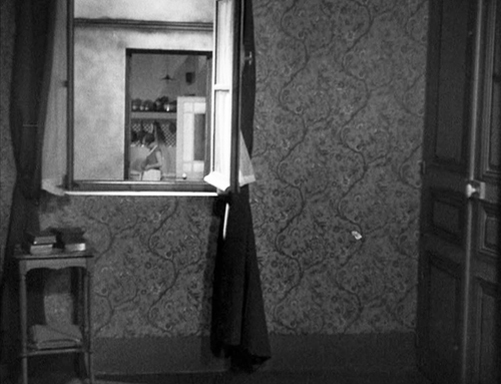

In a modest way, Renoir used the sort of roving camera movement that he would later develop into a major feature his late-1930s masterpieces. One scene starts with Lestingois and his wife eating a meal along with Boudu, seen from a distance down a hallway. As Anne Marie finishes serving, she exits left, and the camera moves left into the next room, where she is glimpsed walking toward the kitchen. It continues moving and stops briefly as Anna Marie enters the kitchen and puts down her tray. As she comes forward to the kitchen window, the camera tracks closer to the foreground window and stops, still at a distance as she talks with an unseen neighbor.

Boudu Saved from Drowning is available on DVD from The Criterion Collection and streams on The Criterion Channel (along with some supplements).

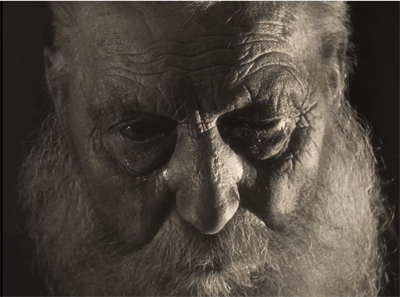

Wooden Crosses

Raymond Bernard’s Wooden Crosses is this year’s masterpiece unknown to most modern viewers, and I cannot recommend it highly enough. I discovered the film through The Criterion Channel. David and I were relatively early in our “Observations on Film Art” series of supplements–early enough that the service was still called Filmstruck. In picking a film for a video essay, I thought it would be helpful to choose titles that were obscure but very much worth calling attention to.

One such film on the Criteron list was Wooden Crosses. I was dubious about it, since my only association with Bernard’s work was the 1924 historical epic, The Miracle of the Wolves, which I had seen back in my post-graduate days and found pretty turgid. Nevertheless, I gave Wooden Crosses a try and was bowled over by it. My video essay, “The Darkness of War in Wooden Crosses,” became number 16 and is available to subscribers.

In some ways Wooden Crosses is France’s great anti-war film of the early 1930s, following Hollywood’s All Quiet on the Western Front and Germany’s Westfront 1918, both of which were in my top ten for 1930. For me, it’s the best of the three.

The film begins with stock footage of Parisian crowds cheering the young men signing up to fight and marching off to war. Like The Big Parade, it introduces the war from well behind the lines, as new recruits arrive at a farmyard where the more experienced troops are billeted. The action takes place shortly after the Battle of the Marne in autumn of 1914; it was won by the French, but did not succeed in achieving ultimate victory. In Wooden Crosses, the experienced men scoff at the recruits for having arrived too late to experience any fighting.

Their optimistic assessment proves wrong, and the group is ordered to march to the front-line trenches. The result is an impressive sequence shot at night as the group goes through open areas, woods, and finally ends neck-deep in the trenches looking out across no man’s land in the darkness. As my video-essay title suggests, there is a considerable amount of night footage in the film. One point I make in that essay is that the epic footage in the film made an impression in Hollywood:

In 1935, the head of the newly merged 20th Century-Fox studio, Darryl Zanuck, bought the North American rights for Bernard’s film. He didn’t intend to release it theatrically. Instead, he realized that the spectacular battle footage was beyond anything that the studio could afford, and he wanted to reuse it.

The film it was to be used in was Howard Hawks’s The Road to Glory, released in 1936. Hawks, however, wasn’t just keen to use the battle footage. Like me, he seems to have admired the many night scenes. He said of Wooden Crosses that it had “Some fabulous film in it, marvelous scenes of great masses of people moving up to the front and through trenches—wonderful night stuff.”

The group of soldiers are quickly and marvelously characterized, notably by Charles Vanel as the group’s quiet, sensible Corporal and Gabriel Gabrio (Javert in Bernard’s Les Misérables) as the sarcastic, boastful Sulphart–a key source of comic relief in the film. Graduallynew volunteer Gilbert Demachy emerges as our main point-of-view character, though the others are kept prominent. There is a suspenseful series of scenes as they hear the sounds of German sappers tunneling below their dugout to lay mines. They are ordered to stay put, as there is plenty of time before the explosions, but as we discover, this is an example of a common motif in these films: the incompetence of the leadership.

One of the film’s most impressive aspects is the epic recreation of battle scenes. There’s no stock footage here, and there are shots over vast areas of no man’s land with explosions going off among the actors.

The climactic battle goes on and on–ten days, as repeated superimposed titles inform us–and conveys the relentlessness of the struggle that the group undergoes.

The battle ends in a long, tense scene, ironically set in a cemetery where many of the graves have been blasted open. These substitute for trenches as the men hunker down under German attack.

As with some of the other films on this year’s list, the cinematography of Wooden Crosses is extraordinary. It was shot by Jules Kruger, who had worked with major French Impressionist directors, notably Marcel L’Herbier on L’Argent and Abel Gance’s Napoléon, the latter of which no doubt gave him considerable experience with epic battle scenes. His most famous films after Wooden Crosses were La belle équipe and Pépé le Moko.

The Criterion Collection did a great service by releasing Wooden Crosses paired with Bernard’s Les Misérables in their Eclipse series. It also streams permanently on The Criterion Channel along with my video essay linked above. (New Year’s resolution: watch more Bernard films. I should give The Miracle of the Wolves another chance and set aside plenty of time to watch Les Misérables, a three-feature serial adaptation of the novel that clocks in at 281 minutes.)

I Was Born, But …

Yasujiro Ozu makes his third appearance in a row on these lists (see here and here for the first two). If I were to live to 102 and if I were still posting these lists, his last film would be on the 2052 list. That’s unlikely, but even so, he will probably be the director most represented on these lists as long as this series continues. I am still pondering whether to give him three spots on the 2023 list or just group his three masterpieces from that year as tied for a single spot.

I Was Born, But … was the first of Ozu’s silent films to become available in the West, and it is still probably the best known. So many of his early films are lost, but this may be the one where he achieved the perfect balance of humor and poignancy that characterizes so many of his best films.

Ozu is known for creating stories centered around the stages of life, often expressed as seasons in their titles, such as Late Spring‘s focusing on a daughter pushing the limits of marriageable age to care for her elderly father. His surviving early films often dealt with students or recent graduates struggling as “salarymen” in the job market of the Depression. In this film for the first time he shows the woes of the salaryman largely from the viewpoint of his children. Many of Ozu’s films are based on relations between parents and children young or grown. Those that dealt with young children were among his masterpieces: Passing Fancy, The Only Son, There Was a Father, Record of a Tenement Gentleman, and Ohayu.

The salaryman films deal with the difficulties of getting jobs, competing with colleagues, and surviving on meager wages. I Was Born, But … adds the problem of the subservience and even humiliation a salaryman sometimes undergoes and how it affects his family.

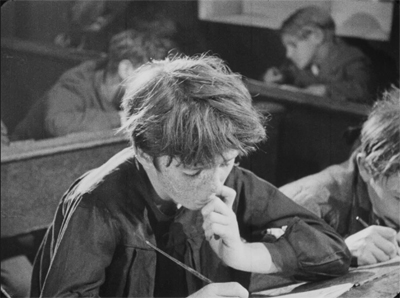

The story unfolds in parts that to some extent echo each other. Early in the film the two sons are bullied at school by the son of their father’s boss. They manage to defeat the bully and in a show of bravado boast that their father is the best in the world.

Later the family is invited to a gathering at the home of Yoshii’s boss, who shows some home movies of his employees showing off for the camera. These include Yoshii making faces and playing the fool, obviously at his boss’s insistence. The sons’ delight in seeing their father on the screen fades as they realize that their father has been humiliated and is not the great man they boasted about. Implicitly, Yoshii is being bullied as well but must submit in order to please his boss.

In an angry confrontation with their father, the sons accuse him of having proved himself not to be the man they had looked up to. The confrontation ends in their refusal to eat or speak to their parents. The parents admit to each other that their life is disappointing and not one they would wish for their children. The quarrel soon ends, with the boys accepting that their father is not the greatest.

As with That Night’s Wife (1930), Ozu is already using some of the techniques that would be part of his style for his entire career. For example, there is a transition between scenes that uses graphic values and objects in a series of images that do not behave like ordinary establishing shots.

I Was Born, But … is available in another DVD set in The Criterion Collection’s Eclipse series, “Silent Ozu: Three Family Comedies.” The other two are the charming Tokyo Chorus and the wonderful Passing Fancy (which will definitely appear on next year’s top ten). Along with a slew of other Ozu films, it also streams on The Channel. Many of you know David’s book, Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema; it’s long out of print but available through open access on the Center for Japanese Studies Publications site (with the frames from the color films in color!).

Kuhle Wampe or Who Owns the World?

Slatan Dudow’s Kuhle Wampe, scripted by Bertolt Brecht, was a bold pro-Communist film made in the year before the Nazis swept into power.

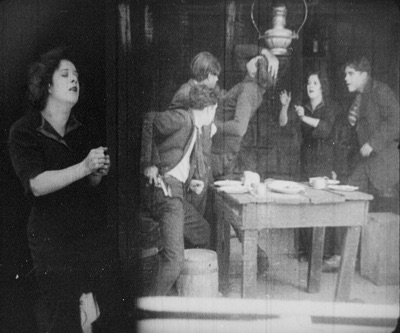

Kuhle Wampe, named for the workers’ camp in which much of it is set, starts with the dire situation for the working class in Depression Germany. A typical family is singled out, with the son returning home after one of many fruitless searches for work (below). His parents blame him for his failure to find work in a society where unemployment is rampant. Their anger drives him to suicide. A neighbor woman remarks resignedly to the camera, “One fewer unemployed.”

The boy’s sister Anni becomes one of the main characters. Another is Fritz, her boyfriend, a leader in the labor protests in a local factory. When Anni becomes pregnant, the pair split up but eventually reunite when her family is evicted and moves into the tent city of the title, run by a Communist group (above). Communism is portrayed as a solution to the problems presented earlier. A lengthy sequence at a Communist youth sports festival emphasizes the happy life on offer by the Party. In the final scene, directed by Brecht himself, Anni and Fritz have an argument about the world’s financial dilemma with some middle-class passengers.

In 1933, Brecht fled the country, eventually ending up in Hollywood, and Dudow was expelled from Germany, only returning after the war to help found the Communist-run East German film industry.

As far as I can tell, the only DVDs or Blu-ray discs available in the US are imports and may not play on encoded machines. (It’s not even on YouTube!) For those with region-free players, the BFI’s release in either format seems to be best source.

Trouble in Paradise.

Wisconsin Film Festival 2022: A return to the theaters

Hit the Road (2021).

KT here:

The Wisconsin Film Festival ended last week. This was the first in-person festival after one cancelled (2020) and one presented through streaming (2021). Given David’s health situation, I was not able to attend many films, but here are some of the highlights that I caught.

Wisconsinite David Koepp visited the festival, bringing two films he scripted, Kimi (Steven Soderbergh, 2022) and Death Becomes Her (Robert Zemeckis, 1992), as well as one that inspired the former, Sorry, Wrong Number (Anatole Litvak, 1948). David and I had already seen Kimi on streaming, but I jumped at the chance to see it on the big screen. The sell-out crowd was utterly enthralled throughout, and David K. charmed them during an all-too-short Q&A session. I won’t say anything more about it, since David B. has blogged about it. I did enjoy two Middle Eastern films and the new Claire Denis. (Not the one about to be in competition at Cannes. The woman is certainly cranking them out.

Amira (2021)

In 2017, the Wisconsin Film Festival showed Mohamed Diab’s extraordinary Clash (2016), an epic restaging of the 2013 riots that brought down the Muslim Brotherhood government, all observed by a group of prisoners in a police paddy-wagon. I was excited to see that this year’s festival included Diab’s next film, Amira.

The new film is quite different from Clash. While that showed a cross-section of Cairo participants in the riots or simply bystanders swept up by the police, Amira centers on a personal drama of an extended family living in an unidentified occupied Palestinian area of Israel. (The film was shot in Jordan, so local landmarks would be no help in figuring out exactly where the family lives.) Amira’s parents have never consummated their marriage, since the husband, Nawar, is imprisoned for life, and his wife Warda became pregnant through semen smuggled out of the prison. Amira is officially the daughter of Nawar’s brother, but she is fiercely devoted to Nawar, going through elaborate security procedures to visit him in prison.

The plot gets going when it is revealed that Nawar has a genetic abnormality that rendered him sterile from birth. The close-knit family descends into vicious arguments and accusations, with Warda being suspected of infidelity, the men on both sides of the family indignantly refusing to take DNA tests, and Amira concocting wild schemes to protect both her parents and ultimately take revenge on the person deemed guilty of bringing disgrace on the family.

Despite the impressive shot of Amira and her boyfriend against the city (above, a cropped image from the widescreen film), the film opts for crowded interiors most of the time–though not as limited as the paddy-wagon of Clash. Small apartments, narrow alleyways, and above all the visits to the prison create a claustrophobic atmosphere where nature and the bustle of society in the city are largely eliminated.

The prison scenes involve extended shot/reverse-shot conversations between Nawar and his family members through a glass barrier.

Shot with telephoto lenses, the scenes use shallow focus to concentrate our attention on the central characters. At the same time, though, reflections and planes of action out of focus create a sense of cramped space and similar conversations going on in a cramped room. Here Nawar suggests that he and Warda have a second child, since an opportunity to smuggle out some of his semen again. Amira’s delight at the idea and Warda’s doubtful expression set up the disastrous revelation to come: that Nawar cannot in fact be Amira’s father.

Checking Diab’s filmography on IMDb, I was surprised to learn that he is the main director on the current Marvel streaming series, Moon Knight. I had been completely ignoring this show, since I have little to no interest in the MCU. I did notice some comments by Egyptological friends on Facebook that the hieroglyphic texts were authentic (an important chapter from the so-called Book of the Dead), as attested by actual Egyptologists. One reviewer commented, “Hollywood has had a problem with how Egypt is represented in both film and TV. ‘Moon Knight’ has done a superb job with episode three, showing Egypt as an actual modern civilization as opposed to a barren wasteland of only sand with a yellow tinted filter over it.” He does not seem to have noticed that this might be due to the fact that an actual Egyptian director was chosen.

I suppose this is not terribly surprising, since for years there has been a trend toward Hollywood producers suddenly elevating talented foreign and indie directors into the ranks of makers of big franchise films. Taika Waititi went from What We Do in the Shadows and Boy to Thor: Ragnarok and Chloe Zhao from Nomadland to Eternals. (I list a considerable number of similar leaps from the festival scene to the world of blockbusters in my entry on Waititi’s rise to international fame.) Still, Diab seems a strange choice. Maybe Clash was sufficient demonstration that he could do epic scenes of violence. I suppose I shall have to give Moon Knight a look.

Hit the Road (2021)

For years now we’ve been blogging about Panahi films (click on Directors: Panahi in the Categories at the right). Now we have another, but it’s not by Jafar. Panah Panahi is his son, and this is his feature debut. Panah began by making shorts, worked as a set photographer, and later as an editor, most notably on his father’s latest feature, Three Faces.

Hit the Road (the Farsi title is more literally translated as “Dirt Road”) reminded me more of the films of Abbas Kiarostami than of the elder Panahi. Jafar worked as an assistant director on Kiarostami’s Through the Olive Trees (1994). Panah was only ten years old at that point, having been born in 1984, the year of Kiarostami’s early feature documentary, First Graders. The New Iranian Cinema came to world prominence later in the 1980s and into the 1990s. Jafar moved into directing features in 1995 with The White Balloon.

Growing up, Panah must have become familiar with the now-classic films of Kiarostami and Mohsen Makhmalbaf, as well as those of his father in the years before the latter’s arrest in 2010.

Hit the Road is reminiscent of the “child quest” films of the early years of the movement. In this case, though, the child in question is not the center of the plot, even though the rambunctious kid steals every scene he’s in. He’s accompanying his parents and older son on a road trip that occupies the entire length of the film. The older son is as quiet as his brother is noisy, but it gradually comes out that he is heading for a spot where he will join others being smuggled out of the country in search of better lives. The parents keep this a secret from the little boy, fearing that he will blurt out something that will draw attention to their goal.

The film is a skillful blend of suspense on that account, of a poignant if quarrelsome love among the family, and a good deal of comedy supplied by the little boy. Amid all the raucous exchanges there are quiet moments, as when during a rest stop the unnamed mother nags her older son about smoking too much while sharing a cigarette with him and asking what his favorite movie is. By this point we suspect that she fears that she will never see him again once they reach the border. (Richard Brody’s insightful review captures this mixture of tones.)

Unlike Amira, Hit the Road is shot entirely out of doors, and often in beautiful, bleak Iranian landscapes (top of entry and below).

At times the family’s SUV climbs hills in shots that recall those of Kiarostami’s films,especially And Life Goes On and The Taste of Cherries, as in the frame at the top of this section. (The literal translation of the Farsi title, Jaddah Khaki, is “Dirt Road.”)

The film has been critically acclaimed and successful on the festival circuit, winner Best Film at the London and Mar del Plata festivals. It seems likely that we will now have two Panahis to report on from future festivals.

Avec amour et acharnement (aka Fire, 2022)

I found Denis’s latest a frustrating and puzzling film for almost its entire length. It reminded me of a similar experience I had with Pablo Larraín’s Ema at the 2019 Venice International Film Festival. I described my initial reaction to that film at the time: “While watching it, I could not discern much of a plot or even a coherent character study.”

Denis’s film, shown outside France under the rather baffling title Fire, starts out innocently enough with a scene of lovers, played by Juliette Binoche and Vincent Lindon, enjoying a blissful, solitary, wordless swim in the ocean. This sets up the “amour” part of the original title. Surprisingly enough, this idyllic sequence, the most visually attractive of the film (above and at the bottom of the entry) was shot during the pandemic on a phone with just the two actors, the director, and the cinematographer present.

Sara and Jean are long-time lovers, and their happiness together continues as they return to their Parisian flat. Soon, however, Sara’s previous lover, François, re-enters their life. He has asked Jean, who has in the past been in prison for some unspecified crime, probably financial, to join him in a athletic scouting agency. Coincidentally, Sara has spotted François in the street, an encounter that seemingly stirs up her old passion for him. She mentions the encounter to Jean, but treats it as a minor thing, expressing pleasure that Jean has been given an opportunity to go into business with his old friend.

From that point the film becomes largely a series of increasingly fraught arguments, as Sara seems to pledge her devotion to both men while resenting the jealousy that they both increasingly feel. All three are revealed to be unpleasant characters acting unwisely, and I, at least, wondered what the point of it all was. The plot seemed to be the classic love triangle, with the question being which man Sara should end up with and whether she will make the right decision–and the issue seeming not to make a great deal of difference for the viewer.

I don’t want to say any more about the plot, since the point of it is to figure out at the very end what Denis had been up to all along. I realized that she was undercutting our expecations about the very clichés that she had presented to us. Apparently I was right. In an interview with Denis, Joseph Cronk mentions that “In an interview in the press notes for the film, you mentioned that the film’s simplicity was ‘a way of foiling clichés.'” Indeed. I’m not sure that many people in the audience with whom I saw the film got the point. I heard some grumbling among the spectators as we left the theater.

It is rather odd to make a film where the audience can “enjoy” it only in retrospect.

I should add that the title Fire does not help a bit.I don’t know who came up with it, but it’s misleading. As Denis has pointed out in interviews, there is no equivalent word to acharnement in English. In the interview mentioned above, Cronk suggests that “With Love and Fury” might be a better title. Denis responds:

No, archarnement doesn’t mean fury. There’s no direct translation, but it means something–from our body, something from your flesh. A sort of tension in the flesh. Fury is something different than acharnement. When I tried translating Avec amour et acharnement, I found no English word I liked that could convey what acharnement means. But Stuart [Staples, the composer] had written the song “Both Sides of the Blade,” and I thought this would be the perfect English title.”

Actually I don’t think “Both Sides of the Blade” would give the spectator much of a clue as to what’s going on in the film. Keeping in mind Denis’s explanation of the French title, however, would.

The quotations from Joseph Cronk’s interview appear in the latest issue of cinema scope, #90 (July 31, 2022), “Not on the Lips: Claire Denis on Avec amour et acharnement.”

Thanks as always to Jim Healy, Ben Reiser, Mike King, and all the staff and volunteers of the Wisconsin Film Festival.

Avec amour et acharnement (aka Fire).

When the image ruled: Julien Duvivier in the silent era

Maman colibri (Mother Hummingbird, 1930).

DB here:

Rewind the tape of film history. What if cinema had been invented as a perfect audiovisual medium, with images exactly synchronized with sound? What would the evolution of film form and style have been like?

Actually, Edison and other early inventors wanted sound to accompany the picture. Technical obstacles to sync sound initially proved too strong, and the fact that the public approved of the silent image led to a delay in fulfilling what André Bazin called “the myth of total cinema.”

It’s long been felt that this delay was a good thing for the artistic development of the medium. Perfect image/sound coordination would have led filmmakers to a line of least resistance, a simple reliance on recording what was taking place in front of the camera. The absence of dialogue forced filmmakers to develop techniques of visual storytelling. “The time of the image,” thundered Abel Gance, “has come!”

Some film techniques were borrowed from theatre and painting, but others became identified closely with the moving image. Techniques such as camera movement, analytical cutting, and rhythmic crosscutting, have analogs in other arts but remain distinctly “cinematic” (chiefly because of cinema’s ability to control duration). During the 1910s and 1920s, filmmakers refined pictorial narrative in ways that couldn’t have been foreseen earlier, and avant-garde movements showed that the new medium had remarkable abstract and non-narrative possibilities as well.

Because of all this, it seemed that sync sound came along just when the silent cinema had reached an expressive peak. By then, people knew the powers of the moving image, and so could integrate sound with it to create an audiovisual art form.

I think there’s a lot to be said for this viewpoint, though it was often used as a cudgel to beat early talkies as “uncinematic.” There’s no denying that many filmmakers who made outstanding silent films, from Hitchcock, Lang, and Ford to Lubitsch, Eisenstein, and Renoir, managed to retain pictorial richness while relying on the unique contributions sound could make. In a teaching exercise, Eisenstein asked students to plan the filming of the assassination of Julius Caesar as a silent film, and then go back and reconceive it as a sound film. That way, the new synthesis could exploit the strengths of both ingredients.

Julien Duvivier’s silent films are good examples of the push toward maximal expressivity by means of visuals. He accepted the coming of sound, even welcoming color and depth, but by then he had already accepted the 1920s urge toward an overwhelming pictorial experience. At one level, he saw the need for spectacle–either shooting on striking locations, employing masses of actors, or creating flamboyant studio sets. At another level, the visual storytelling could be more inward-turning. How could moving images illuminate the thoughts and feelings of characters, the access to minds given through language in prose fiction and on stage? We can see in Duvivier’s late silent work a pressure in both directions: a love of eye-smiting locations either found or fabricated, and an urge to plunge into characters’ minds at every moment.

Julien Duvivier’s silent films are good examples of the push toward maximal expressivity by means of visuals. He accepted the coming of sound, even welcoming color and depth, but by then he had already accepted the 1920s urge toward an overwhelming pictorial experience. At one level, he saw the need for spectacle–either shooting on striking locations, employing masses of actors, or creating flamboyant studio sets. At another level, the visual storytelling could be more inward-turning. How could moving images illuminate the thoughts and feelings of characters, the access to minds given through language in prose fiction and on stage? We can see in Duvivier’s late silent work a pressure in both directions: a love of eye-smiting locations either found or fabricated, and an urge to plunge into characters’ minds at every moment.

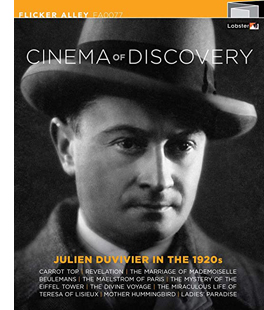

These revelations come courtesy of Flicker Alley’s massive collection of nine of his late 1920s features, all beautifully restored by the dedicated team at Lobster Films. Poil de Carotte (1926), the earliest item in the box, shows a filmmaker utterly in command of the resources of the “mature silent cinema.”

Most of the films between that and Au bonheur des dames (1930) have been largely unknown and forgotten, and their revelation here is unlikely to add another masterpiece to his career log. But they’re very impressive for revealing the diversity and ambitions of mainstream French cinema of the 1920s. Moreover, Duvivier was prepared to carry a commitment to pictorial storytelling to striking extremes.

Eye candy, natural and artificial

Duvivier’s first film, Halcedama (1919; not in this collection), a French “Western,” made extensive use of the rugged terrain of the Corrèze region, “the savage heart of France,” according to a title. Extreme long shots (akin to those in Feuillade’s Tih Minh) let mountains and valleys dwarf the characters. The 1920s films tend to be melodramas, but they too exploit locations with expansive production values.

Before moving to cosmopolitan scenes, Le Tourbillon de Paris (1928)’s opening scenes give off a palpable sense of cold in their bleak display of a man struggling through the snow in Tignes, in the French Alps. The same regional realism is present in La Divine Croisière (1929), shot on location in several coastal cities.

L’Agonie de Jérusalem: Revelation (1927) tells of an anarchist who rejects bourgeois comforts, including “paternal power,” and agitates for world revolution. When he’s blinded, he returns to the family home in Jerusalem. There he undergoes a conversion through identifying with Christ’s suffering and is miraculously cured. Duvivier took the production to Jerusalem, and the film features impressive scenes of the area, including the Wailing Wall and the Garden of Gethsemane.

For Maman Colibri (1930), Duvivier’s heroine, a woman who leaves her husband for a soldier young enough to be her son, follows him to his post in Algeria. The film exploits both desert landscapes and the sumptuous gardens of the Villa Arthur in Algiers. Closer to home, but still carrying the whiff of the picturesque, was Le Mariage de Mlle Beulemans (1927), a comedy about rivalry between brewers. The film begins with a montage of Belgian cities and their landmarks, culminating in a documentary montage of Brussels. The film is bookended by a double wedding at the city’s splendid Grand Place.

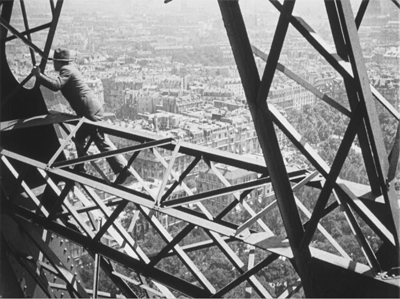

Probably the location shooting that will most attract a viewer today is the climactic sequence of Duvivier’s parody of Feuillade serials, Le Mystère de la Tour Eiffel (1927). It consists of a long chase up the girders of the tower, with actors scrambling after one another in vertigo-inducing shots.

As with Tih Minh, you have to marvel at the acrobatic skill and sheer guts of the performers.

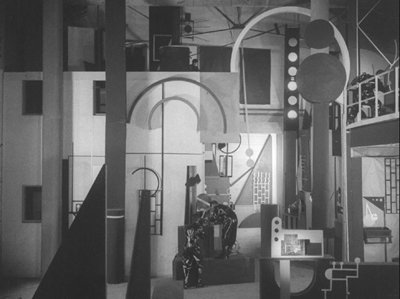

Duvivier also took advantage of the resources of well-endowed French studios, which had yielded impressive set design in Gance’s Napoleon (1927), L’Herbier’s L’Argent (1928), and Dreyer’s Passion de Jeanne d’Arc (1928). Le Tourbillon de Paris, tracing the return of a stage diva to the city she loves, shows her reentry into the haute monde in a huge nightclub scene. This is later matched by her triumph in before a theatre audience.

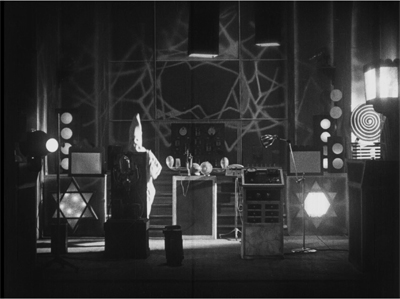

More stylized sets, in a comic vein, characterize the Antenna gang in Mystère de la Tour Eiffel. They use , the Tower to transmit coded messages to their agents. The gang headquarters may be a down-market parody of Léger’s modernist sets of L’Herbier’s L’Inhumaine (1924).

Probably the most famous achievement of Duvivier’s set design is the staggering department-store set in Au Bonheur des Dames, Zola’s story of big business crushing local shops. Sweeping tracking and crane shots enhance the scale of Au Bonheur des Dames, modeled on the Galeries Lafayette (where a few shots were taken as well). The film contrasts the vista of the main shopping area with the cramped store of the fabric merchant Baudu.

The same difference emerges in the broad layout of the office of store’s boss Mouret and Baudu’s pinched apartment, built as a complete set of rooms.

Yet the sets can be less ostentatious and still powerfully functional. The simple, geometric grids and figure placements of the investiture scene in La Vie miraculeuse de Thérèse Martin (1929) gather force through their precise articulation of the stages of the heroine’s acceptance into the sisterhood.

In this twenty-minute sequence, details of gesture and position exude respect for the rigors of ritual and the sincerity of the girl. Duvivier’s calm precision reminds me of scenes in Bresson’s Anges du péché. At the same time, the impersonality of the ceremony is heightened by cutaways to Thérèse’s father, at once pious and regretful; with her novitiate, he will die alone. For him, Duvivier adds Impressionist flourishes to emphasize that the grille shuts him off from her.

Such scenes create a sort of “intimate spectacle” that goes beyond sheer scale.

In a fine crowd scene in La Divine Croisière, Duvivier deploys expressive detail within a mass of people. The predatory capitalist Kerjean has ordered a defective ship to sail, and the townsfolk fear that it has been lost. Simone, a courageous young woman, calls a meeting in which she asks them to cease mourning and set out to look for the sailors. In a brief montage reminiscent of the cream-separator sequence in Eisenstein’s Old and New, close-ups show the villagers gathering hope under Simone’s visionary appeal.

With this sort of intimacy, however, we move close to the second pictorial strategy that characterizes Duvivier and many of his peers: picturing the workings of the mind.

Getting inside

Kristin has pointed out that the 1910s were an era when many filmmakers wanted to go beyond simply creating a coherent story by adding expressive dimensions to the action. Many American films of the period try to illustrate characters’ thoughts, chiefly through flashbacks. There were more elaborate experiments as well, with attempts to portray dreams, hallucinations, and even alternative courses of action. (Some examples here.) In The Gangsters and the Girl (1914), a young woman imagines two consequences of a robbery.

Halcedama had, like many other French films, incorporated simple subjective techniques like these. The looming figure of the protagonist’s dead father interrupts several scenes, and one scene multiplies the presence of the man the protagonist has come to kill.

The early 1920s saw French filmmakers eagerly exploring other resources. Duvivier’s films are much of their time in their inclusion of wide-angle shots with big foregrounds, a great range of camera angles, freely moving camerawork (including crane shots), heavy use of superimposition and dissolves, and a multiplication of cuts, often very fast-paced.

Abel Gance’s La Roue (1922) and Jean Epstein’s Coeur fidèle (1923) crystallized these possibilities, and other filmmakers felt free to flaunt pictorial display. Many of these devices were put in the service of enhanced subjectivity.

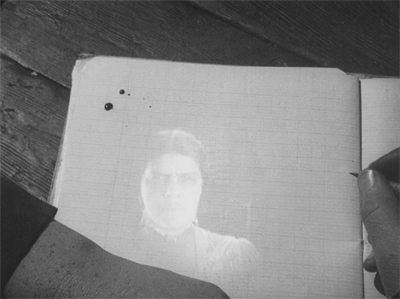

In scene after scene, Duvivier dwells on the moment by plunging into characters’ reactions to the scene, given not through dialogue but through imagery. One of his favorite devices is the superimposition–not as a single item, as in The Gangsters and the Girl, but as a flurry of images melting into one another, suggesting a stream of consciousness. In L’Agonie de Jérusalem, Alice recalls the childhood she shared with Jean, as images rolling along a road.

The heroine of Le Tourbillon de Paris is dazzled by the array of jewels and dresses her husband offers her, and the heroine of Maman Colibri is captivated by her dance partner.

Poil de Carotte is a virtual anthology of ways of conveying mental states. This tale of child abuse probes the fear and despair François feels by being trapped in a family full of hate. The opening uses superimpositions of family members to show how it’s painful for him to write an essay about them.

His cruel mother haunts his dreams, and her attacks on him are given in distorted imagery.

As he rigs up a noose with which to hang himself, we get a rapid montage, in superimposition, of memories of ill treatment.

Nearly every film is packed with these inserted passages, which seek to deepen the drama without use of intertitles. Today they look old-fashioned, even though our films continue to use them. Back then they may have become a bit tiresome. Serge Bromberg’s text for the Flicker Alley booklet quotes a 1930 review:

Why does Julien Duvivier sometimes insist on techniques that seem obsolete today? Overprints [superimpositions] and special lenses no longer surprise us.

When they work best, I think, it’s because they find fresh material that allows them to unexpectedly expand the moment of a scene. For example, François’s father is not so much cruel as indifferent to the boy. His gradual realization that the mother is working the boy like a dog is given two ways. First, a multiple-image shot shows several versions of his son busy in the garden.

Then a series of dissolves following the father’s advance to the camera shows the sheaves now sprung up in profusion–all as a result of the boy’s labor.

Still, Duvivier was able to probe minds without such devices. The village meeting in La Divine Croisière, mentioned above, is an example. So too is a little bit of byplay in Le Mariage de Mlle Beulemans.

Albert, a Parisian, is working in a Brussels brewery and has fallen in love with the boss’s daughter Suzanne. He leaves a corsage on her desk while she’s out. Seraphin, her shady fiancé, has found it there and, when she returns, offers it to her as his own gift. When Albert returns and finds her wearing it, he assumes that he’s won her affection–until he realizes Seraphin’s ploy. Duvivier could have played this out in a series of superimpositions in which Albert imagines her finding it, thinking of him, and wearing it for his sake. Instead, it’s left to the actors in a simple two-shot.

Albert sees her caress the corsage and he’s pleased. But then she says Seraphin gave it to her. There’s no dialogue title. She turns her head to the left to indicate he’s outside.

Albert starts to claim credit, but thinks the better of it and turns away. She notices and asks if he gave it to her.

He doesn’t admit it, but she realizes the truth.

As she ponders Seraphin’s deceit, Albert understands. He approaches, but she wards him off, still believing she must marry her fiancé.

Admittedly, this little pas de deux takes place after a dialogue in which Albert imagines all the slights he’s suffered as an outsider to the company, and before a lyrical passage in which he conjures up finding a flower in a lake. Duvivier couldn’t resist expanding the situation through his usual means. But the understated playing of the pair, without any verbal explanation, shows that he didn’t always need flashy visualizations to evoke characters’ changing reactions to a situation.

Duvivier remained active until his death in 1967, racking up an astonishing seventy-one features. There are plenty I have yet to see, but I’ll just signal some landmarks. Although he has remained most famous for his two Poetic Realist achievements, La Belle équipe (1936) and Pépé le Moko (1937), his accomplishments were more wide-ranging. Allô Berlin? Ici Paris! (1932) is a charming early sound comedy, and Un Carnet de bal (1937) and La Fin du jour (1939) won acclaim around the world. In Reinventing Hollywood I called attention to his significant American work: Lydia (1941), Tales of Manhattan (1942), and Flesh and Fantasy (1943). His powerful Simenon adaptation Panique (1946) is admirable, as are the lighter-hearted Sous le ciel de Paris (1951) and La Fête à Henriette (1952). Marie-Octobre (1959) is an interesting experiment in the three unities. And his later policiers have their supporters, especially Voici les temps des assassins (1956). Attacked by the Nouvelle Vague as a fossilized academic, he has reemerged as a robust example of the enduring force of French film tradition. The Lobster/Flicker Alley box confirms him as a sturdy storyteller and an ambitious pictorialist.

Halcedama is available on the Cinémathèque Française website, among many other discoveries. Gance’s broadside, “Le Temps de l’image est venu!” is in L’Art cinématographique II, ed. Léon Pierre-Quint, Abel Gance, Lionel Landry, and Germaine Dulac (Paris: Félix Alcan, 1927), 83-102. It is available in an Arno Press reprint (New York, 1970).

The best book on French silent film is Richard Abel’s magnificent, encyclopedic French Cinema: The First Wave, 1915-1929. A very complete account of Impressionist cinema is in Noureddine Ghali, L’Avant-garde Cinématographique en France dans les années vingt: Idées, conceptions, théories (Paris: Experimental, 1995). Kristin’s argument about the 1910s is set forth in “The International Exploration of Cinematic Expressivity,” in Film and the First World War, ed. Karel Dibbets and Bert Hogenkamp (Amsterdam University Press, 1995), 65-85.

Kristin picked Au Bonheur des dames as one of the best films of 1930. I discuss Lydia in a Criterion Channel installment, teased here. French Impressionism has remained a powerful, if usually indirect, influence on modern directors–for example, Scorsese.

Le Mariage de Mlle Beulemans (1927).

Thrills and melodrama from the 1910s

Filibus: The Mysterious Air Pirate (1915).

DB here:

Two new DVD releases remind us how 1910s filmmakers, unconstrained by realism, used the newish medium of film as a vehicle of charming, sometimes silly fantasy. One is the virtually unknown 1915 Italian feature Filibus: The Mysterious Air Pirate; the other is the famous but little-seen 1919 serial adventure Tih-Minh, by Louis Feuillade. The Filibus disc also contains a 1916 Italian feature Signori giurati… (“Gentlemen of the Jury,” here The Jury Decided). None seems to me a masterwork, but all are enjoyable and have something to teach us about the almost mad ambitions of an era discovering the power of long-form cinematic storytelling.

Lady with an airship

One thread over the life of this blog has been my nagging claim that the 1910s have not been widely recognized as the lively, innovative years they were. Yes, there was Griffith and Chaplin, but after that people tend to move on to rhapsodize about the glories of 1920s Europe and Hollywood. Of course many viewers appreciate the early work of Mary Pickford, William S. Hart, Buster Keaton, and Doug Fairbanks, and there are fans of great European directors like Sjöström and Feuillade, but even these luminaries are chiefly known for only a film or two.

Many scholars have labored loyally to bring to light major figures like Lois Weber and Albert Capellani, but these revelations remain niche tastes. Kristin and I have done our bit on the blog, in many entries and in the video lecture “How Motion Pictures Became the Movies.” That suggests that today’s film industries, film culture, and artistic options have their sources in this era that, in retrospect, teems with creative possibilities.

The sheer imaginative variety of this output is brought home to me virtually every time I go back to see something recently discovered. My extended stay at the Library of Congress Kluge Center back in early 2016 was a smack on my head. In America, while filmmakers were elaborating the “continuity” system of storytelling (still with us), they were also pursuing side paths and fresh possibilities. (To check, start with “Anybody but Griffith” and move to later entries.) My discoveries complemented my years of visiting European archives to investigate both major auteurs and little-known films. (See the category “tableau staging.”) Now these releases, courtesy of Gaumont (Tih-Minh) and the cooperative efforts of Amsterdam’s Eye Filmmuseum, Milestone Film and Video, and Kino Lorber (Filibus) offer some new angles on the period.

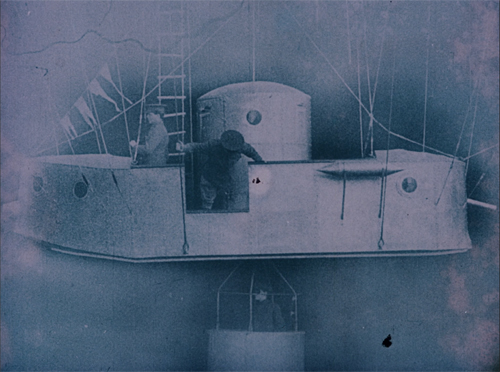

Filibus centers on a supervillain who, unlike Fantômas or Dr. Gar el-Hama, is a woman. Like them, she’s a master of disguise, appearing as a genteel lady but also a suave gentleman and a sleek masked marauder. She steals jewelry through the usual methods: casing a household, sizing up the spoils, and confounding the authorities. What sets her apart is that she travels in a midsize airship that allows her to move swiftly from place to place and lower herself in a gondola to the numerous balconies that give access to the treasures.

She’s also adept at outsmarting the detective Kutt-Hendy. Exploiting the current public fascination with pseudo-scientific detection, the film shows her capturing his fingerprints on a rubber glove, and then leaving them at the scene of the crime. But she has old-fashioned tools as well, including a mysterious knockout scent.

Capably if unspectacularly directed by Mario Roncoroni, the scenes are mounted in straightforward ways for the period. Cutting, as you’d expect, consists largely of linking scenes or occasionally enlarging a detail we need to see, such as a camera inside the eye of a cat statue.

Within dialogues, simple axial cuts give us access to actors’ expressions. Sometimes Rondoroni moves a figure closer to the camera without motivation, simply to show us things more clearly, before the figure then retreats a couple of steps.

This is an anachronistic device, common in much earlier films. Most directors of the period motivated such movements by having something in the foreground that would draw the actor nearer to the camera.

The preposterousness of it all is well-recognized by everyone concerned, I think. The most impressive set, a parlor boasting Egyptomania galore along with the supposedly ancient but highly inauthentic cat sculpture, gets a good workout during the crime and the investigation. What remains, though, is Filibus’ unique transport system that allows her to bypass all the driving down roads and clambering up building facades we get in Feuillade. A blimp and a basket do the trick, leaving Filibus to sail off to her next conquest.

The film was noted as over-the-top in its own day. One critic wrote: “Great drama of adventure? Say rather a great cinematic mess of adventures. . . .” Evidently the tackiness of the special effects was evident as well. But we’re lucky to have it as one more document of the sometimes overstrained efforts to pack fresh sensations into the still-emerging format of the feature film.

Opium and murder

Signori giorati… is more orthodox and, I think, more satisfying as a story. A classic salon melodrama with plenty of diva posturing, it shows the decadence of the very rich brought to account. The adventuress Julienne (originally Lina) Santiago has seduced Dr. Nancey into setting up a plush opium parlor. Every night, the rich come to the “House of Forgetfulnesss,” where Julienne and the doctor blithely pick their pockets. When the police get interested, Julienne betrays Nancey and bolts, later to take up with one of their clients, the Marquis de Vallier. He resolves to marry her and brings her home to meet his daughter Helène (Valeria Creti, aka Falibus) and her husband. A deadly intrigue begins.

Signori giorati… shows the pluralism of visual expression of the period. While depth staging isn’t much developed here, the vast opium-den set carries the action far into the distance, where Julienne, masked, awaits the Marquis (above). Later, lurking in the reeds, Julienne stalks Helène’s husband.

Courtroom scenes in 1910s films are surprisingly varied, and director Giuseppe Giusti offers an unusual array of angles on the action.

A split-frame flashback illustrates courtroom testimony.

None of these moments is extraordinary for the period, but they nicely exemplify visual strategies becoming normalized in European cinema. Likewise, the somewhat awkward linkage between the first section around the opium den and the second on the Vallier estate show the need to tighten up the overall arc of the narrative–a problem European films would face for some years.

An unusual feature of the disc is the inclusion of five short films from the Amsterdam premiere of Filibus in 1918. This was made possible by the Eye Filmuseum’s splendid collection of early films from around the world shown in the Netherlands by the distributor Jean DeSmet. There’s also a brief short giving background to that collection.

From Vietnam to the Riviera

Tih-Minh (1919) followed in the wake of Louis Feuillade’s successful serials Fantômas (1913-1914), Les Vampires (1915-1916), Judex (1917), and La Nouvelle mission de Judex (1918). Released in installments from February to April 1919, Tih-Minh followed an important Feuillade feature, Vendémiaire, released in January. Throughout the same years Feuillade signed dozens of shorter comedies and dramas. Not only was he an efficient director on a scale we can hardly imagine today, but he had a powerful incentive: Gaumont gave its top directors a percentage of a film’s revenues, and Feuillade’s salary made him wealthy.

The plot revolves around a treasure supposedly hidden in Indochina. But where? A Sanskrit book contains notes, in code, about its whereabouts. The explorer Jacques d’Athys has unwittingly acquired it during his last expedition. Learning this, former German spies Kistna the “Asiatic” and Dr. Gilson recruit the hapless Marquis Dolores (above) and target Jacques’ villa in Nice. Jacques has also brought back the delicate young woman Tih-Minh (also above), daughter of a French colonist murdered, it’s revealed, by Gilson (né Marx!). The complications around the coded message lead the gang to a series of raids on the household, usually involving efforts to kidnap Tih-Minh. The efforts are resisted by our heroes–Jacques, his loyal servant Placide, the maid Rosette, and the British diplomat Sir Francis Gray.

Tih-Minh has an essentially comic structure. Unlike Fantômas and the Vampires, this gang can’t catch a break. Nearly every attempt they make, involving poisons, amnesia serum, hypnosis, and accomplices smuggled into the household, is thwarted, quickly or eventually. The ineptitude of Kistna’s gang is nearly matched by the passivity of Jacques’ team. They seem to wait around for the next assault, and when they prepare a trap, it usually fails. Only Placide, consistently suspicious, mounts countermeasures. Just when you wonder whether Nice has a police force, Jacques announces they can handle things best themselves.

Tih-Minh, a favorite of mine over the years, cracked a bit on this go-round. For the first time I found the opening installments dilatory and meandering. Feuillade is counting on our enjoying the company of these comfortably rich people and their rounds of coffee breaks, walks on the estate, and flower-picking in dazzling sunlight. And it is a kind of Bower of Bliss, which will eventually host three weddings.

Unlike the earlier serials, where he relies on composition in depth, here he favors lateral layouts. It’s as if the speed of the production pressed him toward lining up characters talking to one another in long-shot and medium-shot. Yet as I wrote about here, he varies the placement of heads in graceful waves.

These framings look forward to his later work’s “long-take” setups, broken only by dialogue titles.

The pacing and flashy visual invention pick up considerably in the later installments, when Feuillade hurls his cast through the magnificent landscapes of the Riviera. During the war, Gaumont moved substantial portions of production to the Victorine studios in Nice. Installing himself there in 1918, Feuillade takes advantage of everything in the neighborhood. You can sense his delight in finding ways to use the ocean front, rocky terrain, gorges, mountain crags, decrepit hilltop castles, luxurious estates, and hotel rooftops.

Pursuits across these forbidding spaces are a powerful attraction in their own right, and the second half of the film does not disappoint. For some shots the camera seems a mile away from the tiny human figures.

The actors accordingly give their all. Placide’s physical comedy is matched by his willingness to be beaten up, dropped from a great height, or folded up into a trunk lashed to an automobile roof. Flung into the ocean, he laughs it off.

Heroes and villains alike are willing to clamber around scaffolding and window ledges and crawl down the face of a mountain.

Mary Harald as Tih-Minh, apparently a wilting flower, seems game for anything as well.

We’re so used to stunt doubles for action scenes that we forget that long ago actors were athletes.

The vertiginous spaces and the bravado of the performers come to a climax when the chase moves to a zipline carrying rock from a quarry down into a valley. The villains dive into one of the gondolas and ride off to infinity. Undaunted, our heroes follow.

These shots, a rebuke to the cheesiness of Falibus‘ special effects, are alone worth the price of a DVD. And you thought Preminger treated actors roughly?

One more aspect of this release makes it a must-have for admirers of early film. It is one of the finest digital transfers of a silent film to disc that I have ever seen. Derived from a pristine negative, it is a perfect illustration of what 1910s cinema looked like at its best. (Thankfully, it is not tinted. Tinted versions often smudge original photographic detail.) We always knew that there was more on a 35mm orthochromatic film than we could see. Now we see it.

Gaumont’s disc of Tih-Minh is coded for all regions and contains optional English subtitles. Unless a US distributor picks it up, it will be available only at places like Fnac and Amazon.fr. University libraries and film departments should be able to get copies easily. Beware the bootleg version of the Belgian print (the source for the restoration’s intertitles) offered on eBay and elsewhere.