Archive for the 'National cinemas: France' Category

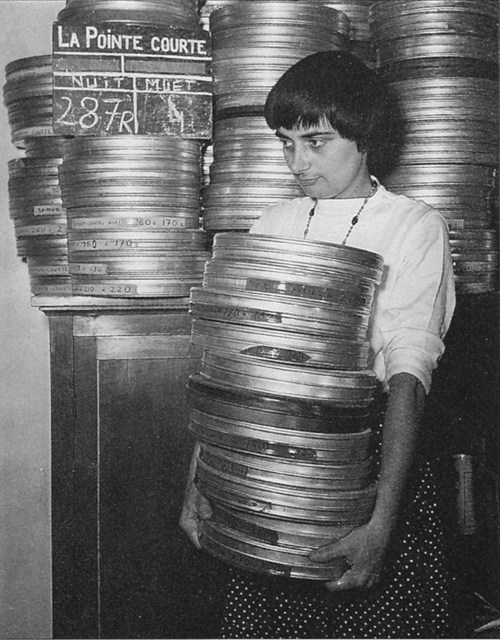

Still Agnès

Self-portrait by Agnès Varda.

DB here:

Sixty years ago, a twentysomething photographer released a film shot in an out-of-the-way French fishing village. Coming right after Rossellini’s Voyage to Italy and Fellini’s La Strada (both 1954), the result announced something new in cinema. Like those other works, it looked forward to the French Nouvelle Vague and the cinematic modernism of Antonioni, Bergman, and a host of other filmmakers.

But the status of Agnès Varda’s La Pointe Courte (1955) became apparent only with the most distant hindsight. It didn’t win big attention on the festival circuit, in the international market, or in the pages of highbrow film magazines. Denied a commercial release, La Pointe Courte circulated mostly in French ciné-clubs. In the early 1980s, when I saw it at the Brussels Cinematek, it was still a rarity.

Thirty years after La Pointe Courte, Varda’s career reached a new level. Vagabond (Sans toi ni loi, 1985), widely recognized as her masterpiece, remains one of the great achievements of that modern cinema she helped create. And she hasn’t exactly been idle since. There have been many films both long and short, including a biopic of her husband Jacques Demy in Jacquot de Nantes (1991) and the picaresque The Gleaners and I (2000); the fascinating autobiography Varda par Agnès (1994); and over the last decade a series of installations in museums around the world. She started as a photographer, became a cinéaste, and is now a plasticienne, a maker of painting and sculpture.

She is eighty-seven years old.

Agnès V., not B.

Our colleague Kelley Conway has just published an authoritative consideration of the work of this shrewd, unpredictable survivor. Reading Kelley’s book reminded me of that encounter with La Pointe Courte.

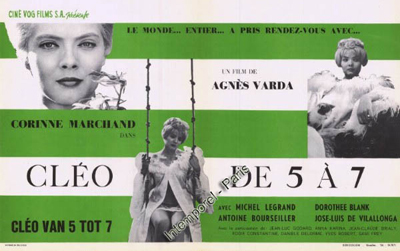

I had known Varda’s more famous works: Cléo from 5 to 7 (1961), screened at my college film society as the project of a New-Wave fellow-traveler; Le Bonheur (1965), which might be called Jules et Jim revisé et corrigé; One Sings the Other Doesn’t (1977), which got circulation among other feminist films of the period. These didn’t prepare me for La Pointe Courte’s daring mix of realism and minimalism. Varda wanted, she said, to make a film that was the equivalent of a difficult book, and for me she succeeded.

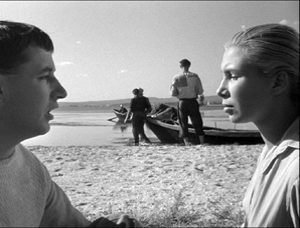

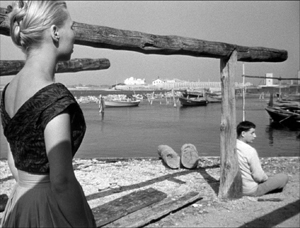

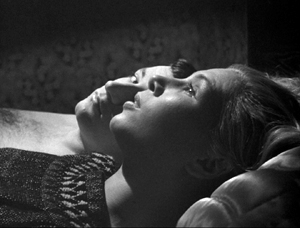

The film alternates sunny images of local life—fishing, net-mending, washing-up, a festival—with episodes in which a Parisian couple drift through the village, oddly detached from the life around them. The everyday scenes are shot in documentary style, but with a casual rigor suggesting Cartier-Bresson. Meanwhile, the couple talk in stylized compositions that could only remind me of L’Avventura.

No wonder Picasso was Varda’s favorite painter: she splits up the couple’s faces with cubistic zeal.

The disjunction between the actuality of a location and the abstraction of the couple’s anomie-riddled duet, often heard only as voice-over commentary, looks forward to Hiroshima mon amour. (No wonder: Resnais edited the film.) I barely understood the French, but the film gripped me. It was of great historical interest, and it had its own stubborn vivacity. When Kristin and I planned the first edition of Film History: An Introduction (1994) I made sure it got in. In that year, forty years after it was made, La Pointe Courte was released on VHS.

Things change. Varda is now regarded as a living treasure of world cinema, preserved in excellent Criterion DVD editions, available for streaming on Hulu, and wrapped up in a vast cube, Tout(e) Varda (20 features, 16 shorts). Whatever she does in the future, we can at least take a long-distance measure of her accomplishments.

The dream of many writers on a single director is to cover it all: appreciative study of the films, background on how the films came to be, assessment of their immediate impact and long-range influence. But this breadth of understanding is very hard to achieve. Where are the documents? How do you get the filmmaker to talk?

Kelley has done it. Her book combines film analysis, historical research, and information drawn from Varda’s archives. Kelley can tell us how the films came to be, what Varda wanted to accomplish, and how they were received. To top it off, there’s a new interview with Agnès herself.

Crossing landscapes

Les Demoiselles ont eu 25 ans (1993): Varda and Deneuve.

With a brisk practicality echoing that of her subject, Kelley has focused her lens tightly. You can’t quarrel with her choices: La Pointe Courte, the early short documentaries, Cléo, Vagabond, The Gleaners, two installations, and The Beaches of Agnès (2008). Her plan of attack is straightforward: scrutinize the film, then work backward to the conditions of production and forward to the film’s reception.The analyses are models of attention to story and style, images and sounds. Kelley pins down what intrigued me about the acting in La Pointe Courte, showing its debt to Brechtian distancing (a big influence on Varda). She goes on to connect the performances to the experiments in “flat” performance we find in Tati and Bresson at the same period. Kelley shows how many of Varda’s artistic strategies, such as whimsical puns and a love of digression, go back to her early documentaries.

In a sense, Varda has never ceased to be a documentarist, since all her films depend on a process of research, exploration, and a personal viewpoint characteristic of the roving photographer. The book includes fresh information on two of Varda’s major multimedia installations, obviously born of her interest in found materials, gags, and unexpected juxtapositions. For one, Varda covered the gallery floor with 1500 pounds of potatoes and played the role of “Lady Potato.” Another exhibition included a reference to the grave of her beloved cat Zgougou. As described by Kelley, these installations are less narcissistic than they might seem, because Varda’s work has always been personal, derived from her perceptions of her subject. Even The Gleaners, which is at one level a denunciation of a society built on waste and inequality, is refracted through the filmmaker’s sense of aging. And though Mona in Vagabond is ferociously solitary, we meet her through Varda’s welcoming voice-over: “It seems to me she came from the sea.”

In a sense, Varda has never ceased to be a documentarist, since all her films depend on a process of research, exploration, and a personal viewpoint characteristic of the roving photographer. The book includes fresh information on two of Varda’s major multimedia installations, obviously born of her interest in found materials, gags, and unexpected juxtapositions. For one, Varda covered the gallery floor with 1500 pounds of potatoes and played the role of “Lady Potato.” Another exhibition included a reference to the grave of her beloved cat Zgougou. As described by Kelley, these installations are less narcissistic than they might seem, because Varda’s work has always been personal, derived from her perceptions of her subject. Even The Gleaners, which is at one level a denunciation of a society built on waste and inequality, is refracted through the filmmaker’s sense of aging. And though Mona in Vagabond is ferociously solitary, we meet her through Varda’s welcoming voice-over: “It seems to me she came from the sea.”

Another legacy of documentary: Kelley points up how even the fiction films spring from an attention to the specifics of a locale. “Part of Varda’s journey is regularly exploring a chosen region at length, waiting for ideas, emotions, and images to emerge.” That region might be a single Parisian street (L’Opéra-Mouffe, 1958; Daguerréotypes, 1975) or the fourteenth arrondissement (Cleo from 5 to 7). Like La Pointe Courte, Cleo is the story of a walk, this time purportedly played out in actual duration as a beautiful pop singer awaits the results of a test for cancer. Mona, in Vagabond, is another wanderer, and the wintry bleakness of southern France is as central to the action as whatever psychology we can find in her or the people she meets. The Gleaners and I searches out people who stalk the landscape and live off what they can scavenge. With modern cinema from Bicycle Thieves onward, Dwight Macdonald once noted, “The talkies have become the walkies,” but Varda has always embedded her footloose protagonists in the particulars of place.

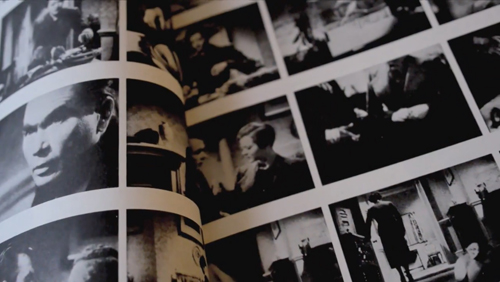

Varda’s personal archive has given Kelley the opportunity to document the director’s creative process. The scripts are sometimes scrapbooks, with texts and images jostling one another. (Kelley offers an example in a 2011 blog entry.) The arrival of digital tools reinforced and expanded Varda’s method of free assembly. Out of a database of images, Varda erected the scaffolding of The Beaches of Agnès before starting her screenplay. She wrote, shot, and edited the whole thing in a nonlinear fashion. During the final stages, two editors worked busily in separate rooms. “I went from one to the other. On one side was Sète and Los Angeles, in the other room was Belgium and Paris.”

As for exhibition, crucial to Varda’s early films was a distinctive French institution. Varda had created her company to make shorts, but when La Pointe Courte grew to 80 minutes, it could not be distributed under those auspices without new investment. As a result, it found its main audience in the network of ciné-clubs that had grown up after World War II. That network became activated to the maximum during the release of Cleo from 5 to 7. One of the side benefits of Kelley’s book is its explanation of the power that the ciné-club scene had achieved by the early 1960s.

Brandishing the slogan “Develop Film Taste, Introduce Masterpieces, Educate the Public,” an astonishing five hundred clubs with over two hundred thousand members showed thousands of films in the year that Cleo was released. Varda took advantage of this situation to promote her film, but Kelley goes beyond the simple marketing issue to point out that the clubs bolstered spectators’ appreciation of New Wave films. She draws on audience comments to show that the organizers guided audiences to talk about form, style, theme, and historical context. The clubs helped create the “demanding viewer” described by Alain Resnais: a viewer eager for challenging films that could bear comparison to advanced works in traditional arts.

Varda’s later films were absorbed into the mainstream commercial distribution/exhibition infrastructure, and Kelley is painstaking in plotting critical response to them. Near the book’s close, she traces how another institution shaped Varda’s work: the museum. Kelley shows how the emerging importance of installation art encouraged filmmakers like Varda and Chris Marker to create multimedia exhibits that were natural continuations of their poetic-essayistic documentaries. The installations seem to have encouraged Varda to take up the autobiographical compilation mode that yielded The Beaches of Agnès.

There is much more in Agnès Varda than I can summarize, but I hope I’ve piqued your interest. For any lover of Varda, Kelley’s book is a must, and even casual viewers will learn things that will drive them to the films. Reading it led me to think about how Varda’s lack of cinephile culture (she emphasizes that she knew nothing of film when she started) allowed her to respond to stories more directly than did the Bad Boys of the Cahiers, who saw everything through a mesh of hundreds of other movies. I was also prodded to think of her as quite an innovator in narrative. She has given us the parallel structure of La Pointe Courte, the fantastic science-fiction plot of Les Créatures, the isoceles love triangle of Le Bonheur, the dual-protagonist structure of One Sings, and the network narrative of Vagabond, with Mona as a circulating object a bit like Bresson’s Balthazar.

From the delightful interview with Lady Potato herself, I allow myself just one spoiler:

KC: You seem to start your projects with considerable preparation but you also have a flair for improvisation. Do you see it that way also?

AV: Yes and no. Or no and yes, depending.

An earlier entry discusses a Kelley talk on La Point Courte. I discuss some ambiguous narrative cues in Vagabond in my updated “Art Cinema” essay in Poetics of Cinema, 166-169.

This has been a good publishing year for our colleagues at Wisconsin–Madison. Lea Jacobs’ book on filmic rhythm came out last winter; go here for our observations.

Il Cinema Ritrovato: The advantages of leaving home

Kristin here-

David and I are in Bologna for Il Cinema Ritrovato. Once again there is an overwhelming choice of films on offer, demanding a patient acceptance of the fact that one cannot possibly see anything close to everything one wishes. Careful planning can only do so much.

If there is anything I have learned from the films in the first half of the festival, it is that one should not leave home. In the earliest surviving Mizoguchi Kenji film, The Song of Home (1925), a talented but impoverished young man accepts the idea that staying in his village is best for both himself and Japan.

Nearly thirty years later, Girls in the Orchard (dir. Yamamoto Kajiro, 1953), the heroine must choose between going to Okinawa with her fiancé or marrying a man who can help her maintain her family’s traditional pear farm. Naturally, she makes the right choice.

The heroine of Ousmane Sembène’s first feature, the pioneering Senegalese film La noire de … (aka Black Girl, 1966) leaves her home country for France and the better life she dreams of, only to find herself virtually imprisoned working as a maid in Antibes.

The lesson is clear, and yet those of us who have ventured from around the world to Bologna are all the better for it.

Color blooms in Bologna

Color films have always featured on the program at Bologna, but this year various processes are on display in more threads than usual. While the past three festivals have offered a lengthy retrospective of early Japanese found films, this year’s it’s early Japanese color films. There are vintage Technicolor prints in one series, restored color from the silent era in several threads, and eye-poppers like Cover Girl among the restorations being shown off by various archives and labs.

The first screening on the opening afternoon of June 27 was The Thief of Bagdad–not the Fairbanks silent but the 1940 British version co-directed by Ludwig Berger, Michael Powell, and Tim Whelan. I must have been one of the few in the vast Arlecchino theatre who had never seen it, even in a faded 16mm print. Some were there to recapture the fond memories of their youth.

As a “vintage” print, it had an odd history. This was not a vintage re-release print, as some of us expected. It stemmed from the 1990s chemical restoration which was subsequently digitally scanned. The images looked like the Technicolor films of my youth (not quite the 1940s, but at least the 1950s). It was a relatively early film using the three-strip Tech process, which had really only reached its ideal form in Hollywood as recently as 1939, with The Wizard of Oz and Gone with the Wind.

This print had the eccentricities of the three-strip process. Some shots had poor registration, with red and green rims around the characters, while others were in perfect alignment. The matte lines for the numerous fantastical effects (flying horse, giant jinn, flying carpet) were very obvious, and the color changed suddenly for every dissolve. The print was probably not a bad indication of what audiences would have seen at the time.

The design certainly took advantage of the color process, with numerous false-perspective sets and costumes carefully arranged to show off the range of bright hues that Technicolor could achieve (above).

As for the film itself, it is extremely charming without being one of the masterpieces of the era. It suffers from having a bland pair of actors as Ahmad and the princess who loves him, and Sabu is perhaps a trifle too irrepressible as the titular thief, Abu. Miles Malleson, the comic character actor who co-scripted the film, steals the show as a Sultan so obsessed with elaborate mechanical toys that he trades his daughter to the villainous Jaffar (Conrad Veidt, acting rings around much of the cast) for the flying horse. It was an epic in its day and perhaps helped give rise to the many Technicolor fantasies of the 1950s.

A different sort of range was shown off in a program of silent films restored by the EYE Filmmuseum of the Netherlands. These included hand coloring, as in a 1915 short documentary preserved under its English title, Dutch Types, primarily consisting of shots of villages and schoolchildren.

A 1913 Italian film La falsa strada (dir. Roberto Danesi) was a tinted print. It starts off with a familiar situation of an opera singer giving up the stage to live a quiet life on her rich husband’s country estate. One might expect a young lover to rescue her from her boredom, but instead her very lively show-business friends from the city visit and cause the husband to be jealous of the singer’s apparent preference for their company over his. Unfortunately the final reel was missing.

Even more incomplete was Una notte a Calcutta (dir. Mario Caserini, 1918, right). Only a couple of scenes totaling eleven minutes survive, but they show off the talents of diva Lyda Borelli and suggest that the settings and costumes for this otherwise lost film were impressive.

The emphasis on color promises to continue next year, as with the hints dropped concerning further early Japanese color films to come on a second program.

The auteur of the year

Following a long-established tradition, the festival includes a retrospective of a Hollywood director, Leo McCarey. Having seen quite a few of the films on offer, I haven’t followed this thread faithfully. I fondly remembered Ruggles of Red Gap (1935) from a single 16mm viewing many years ago, though, and decided to watch it. I was glad I did. For a start, it was a mint 35mm print and a joy to watch. Moreover, I had remembered Charles Laughton’s performance as hopelessly mannered and eccentric. This time I caught many of the subtle gestures and glances that he used to convey the thoughts of a character who, at least in the early scenes, speaks little and then only very formally. The supporting cast is ideal for the witty script that condenses the overly long original novel.

McCarey got his start by directing two-reelers with some of the best second-tier slapstick comics of the 1920s, including Charlie Chase, Max Davidson, and Mabel Normand. One program of three showed off each in turn. The Uneasy Three (1925) casts Chase as an aspiring burglar invading a society party with two partners-in-crime sneaking in by impersonating a trio of classical musicians. Don’t Tell Everything (1927) has Max Davidson marrying a wealthy widow, only to have his obnoxious freckled son (Spec O’Donnell, as always) worm his way into the household by disguising himself as a surprisingly convincing maid. Finally, Should Men Walk Home? (1927) teams Creighton Hale and Mabel Normand in another stealing-a-brooch-from-a-society-party plot. Normand gives a late, great performance. (Imdb lists this as her penultimate role.)

The World Cinema Project restores another three

I always try to see the latest films restored by the World Cinema Project, which aims to save important movies made in countries that do not have the archives or resources to protect them. This year the films were La noire de …, Sembène’s first feature, Ahmed El Maanouni’s Moroccan film, Alyam Alyam (aka Oh the Days, 1978), and Lino Broca’s Insiang (the Philippines, 1976).

La noire de … deals with the post-colonialist effects of French rule in Senegal, with the heroine Diouana (below) eager to visit the France of her dreams. Once there, she is never allowed to leave the apartment of the French couple who has employed her; they told her she was to care for their children, but she is relegated to household tasks.

Our friend Peter Rist recalled seeing this film with a color sequence, but this was not included in the restoration. The informative panel introduction to the film, led by Cecilia Cenciarelli of Project, revealed that a sequence showing Diouana’s arrival in Marseilles was shot in color. The idea was to show the heroine’s hopeful view of her new country, contrasting with the black and white of the rest of her film as that hope dissipates. Cenciarelli said that there is no clear evidence that Sembène intended this color scene to be part of the final film. If it survives, it would make a valuable supplement to a future home-video release.

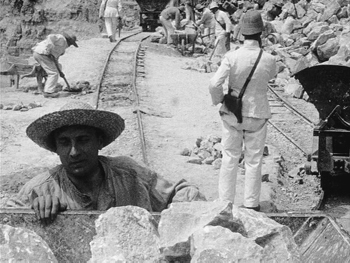

Going from Ruggles of Red Gap to Insiang was an experience in contrasts of the sort one often has here. Insiang is the film’s heroine, a laundress living in a Manila slum. The film was shot in a poverty-stricken area and incorporates many candid shots of children playing in mud and puddles. Much of the action involves shiftless young men who drink and gossip as the women around them do most of the work (above). Against this reality-based milieu, Brocka sets an extremely melodramatic story of Insiang and her mother competing for the affections of the same wastrel. One suspects that Brocka was trying to make his grim film palatable to a broader audience, but the film was a financial failure.

Maanouni took a very different approach for Alyam Alyam. There is a minimal plot about a young peasant earning money to travel to France or the Netherlands for work. This character and his mother and grandfather,  who strenuously object to be his perceived desertion of them, appear at intervals through the film. Most of the scenes, however, are poetic views of village life, evoking both the back-breaking labor of the countryside and the beauty of its traditions.

who strenuously object to be his perceived desertion of them, appear at intervals through the film. Most of the scenes, however, are poetic views of village life, evoking both the back-breaking labor of the countryside and the beauty of its traditions.

In introducing the film, Maanouni said that he wanted to question why Morocco cannot provide the opportunity and incentive to keep young people from leaving. By emphasizing a lyrical depiction of the countryside and the impossibility of earning anything but a subsistence wage, he makes vivid the sad waste of the nation’s potential–a problem that has persisted for decades since the film was made.

The unending march of restoration

The one theme that persists from festival to festival is the thread of re-discovered and restored films. The screenings and, increasingly, the panels and lectures on archival methods, reminds us of how expensive and difficult this process is and how much work goes on each year.

The main film I have seen so far among the restorations is Julien Duvivier’s little-known 1939 film, La fin du jour. (A restoration of his more famous Le belle equipe, 1936, was also shown this year.) It’s the story of a group of actors living in a chateau supported by private charities and dedicated to taking care of aging thespians. They play out their individual dramas against the backdrop of a threatened bankruptcy of the home and a dispersal of its inhabitants to various government hospitals across the country.

There are three primary stories. Cabrissade (Michel Simon) maintains his claim to dramatic fame despite having been only an understudy, and that to a star who never missed a performance. Now entering the home and disturbing its equilibrium is Saint-Clair (Louis Jouvet), an unrepentant seducer and liar. Marny (the less famous but excellent Victor Francen) is a successful actor depressed over his wife’s death, perhaps by suicide, after she ran away with Saint-Clair.

There are numerous small plotlines played out by skilled character actors of the era. The ensemble is interwoven in an impressive example of the “Cinema of Quality,” here practiced by scriptwriter Charles Spaak in collaboration with Duvivier. The tale briefly becomes maudlin toward the end but overall is a touching and often funny depiction of old age among a group particularly reluctant to face that time of life.

In the second half of Il Cinema Ritrovato, I’m concentrating on a small retrospective of Iranian cinema of the 1960s and 1970s, as well as a long-awaited restoration of Satyajit Ray’s Apu Trilogy.

David’s book Figures Traced in Light discusses how The Song of Home displays Mizoguchi’s early mastery of Hollywood-style staging and cutting, before he went on to try considerably different techniques.

Thanks to Manfred Polak for a correction regarding La noire de … His blog entry on the film is here.

La noire de… (Ousmane Sembène, 1966).

TRUFFAUT/HITCHCOCK, HITCHCOCK/TRUFFAUT, and the Big Reveal

Photo by Philippe Halsman.

I’m going through a Hitchcockian period; every week I go and see again two or three of those films of his that have been reissued; there’s no doubt at all, he’s the greatest, the most complete, the most illuminating, the most beautiful, the most powerful, the most experimental and the luckiest; he’s been touched by a kind of grace.

François Truffaut, letter, 1961

DB here:

In June of 1962, François Truffaut wrote to Alfred Hitchcock proposing a lengthy interview. Hitchcock agreed, and Truffaut materialized in Los Angeles in August, with his translator and collaborator Helen Scott. After six days of discussion, Truffaut had accumulated, he claimed, fifty hours of tape. Over the next four years the tapes were transcribed, the book was edited, and extra sessions were recorded to cover the films Hitchcock made in the meantime. The result was published in France in late 1966 and a year later in an English translation.

Energetic scholars have recently discovered that the finished book bears signs of massive cutting, compression, and recasting of the conversation. It seems that Hitchcock approved something like the final version, but on this director we want everything. Eventually we will want a complete transcription, but with some tapes still missing, that isn’t possible for now. But we do have some tapes, and just as important, we have the book known in English as Truffaut/Hitchcock.

What Truffaut called his “Hitchbook” is now the subject of fascinating documentary by Kent Jones. Premiered at Cannes, Hitchcock/Truffaut was so successful that an extra screening was scheduled to meet the demand. Why so much interest? Of course, Hitchcock remains a filmmaker known to everyone. But we should also recognize that the Hitchbook was one of the most important books on film ever published.

Popular material treated with intelligence

Alfred Hitchcock, who is a remarkably intelligent man, formed the habit early—right from the start of his career in England—of predicting each aspect of his films. All his life he has worked to make his own tastes coincide with the public’s, emphasizing humor in his English period and suspense in his American period. This dosage of humor and suspense has made Hitchcock one of the most commercial directors in the world. . . . It is the strict demands he makes on himself and on his art that have made him a great director.

François Truffaut, review of Rear Window, 1954

The film’ s title is an impudent reversal: “Hitchcock/Truffaut” puts first things first, a dialogue between a master and his adoring admirer.

At first glance, this is a clips-plus-talking-heads doc. But that impression doesn’t do it justice. For one thing, many of the clips are fresh ones, drawn from rarely shown Hitchcock films. These tease us with their unfamiliarity, like a gallery of less-known pictures flanking a hall of masterpieces.

Moreover, the film’s perspective is far more sophisticated than what we usually find in the genre. Hitchcock/Truffaut respects its viewers enough to summon up suggestive and subtle links between sequences, between image and commentary. Often there’s no title marring the images, so they stand out with a hallucinatory purity. Often a clip starts to play before the commentary kicks in, all the better to let the imagery strike us in its integrity; only then do we get the connection to what came before. The extracts are the prime movers, with the text snapping into place to catch up.

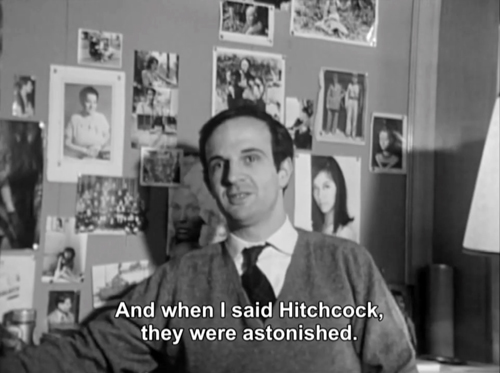

The speed and precision of Hitchcock’s movies are paralleled by the swift opening of Jones’s film, which introduces the main themes. As shots from Sabotage are intercut with the book’s flipping pages, we hear a chorus of voices. These belong to our talking heads, and the heads are full of ideas. Remarkably, all the commenters are film directors. It’s a top-tier lineup, of Movie Brats (Scorsese, Schrader, Bogdanovich) and younger talents David Fincher, James Gray, Wes Anderson, and Richard Linklater. From overseas come Kurosawa Kiyoshi, Olivier Assayas, and Arnaud Desplechin. There are no academic experts, no journalists or friends or family. Everything, we quickly learn, is going to be about cinema as art, craft, and vocation.

Immediately, as if reenacting Family Plot, the film shows how two paths crossed. A quick summary of each man’s career leads to that six-day week in 1962, overseen by the beaming Helen Scott, and our film launches itself into the depths.

We learn of Hitchcock’s urge to outwit the audience, and his thoughts on plausibility. He reviews matters of technique, from image size to the expansion of time. How do you handle actors? How do you give your film a shape? About halfway through, the questions go bigger, and the Cahiers concerns preside. Is M. Hitchcock a Catholic artist? (He gives his answer off-mike.) Is his work haunted by guilt, even Original Sin? (“Yes,” he murmurs.) Don’t the plots enact a transfer of guilt? Don’t they exhibit the logic of dreams?

At one level, Hitchcock/Truffaut is a fine introduction to the issues in French film writing about the Master, articulated most fully by Desplechin. But the Americans bring in plenty of insights as well. Fincher and Scorsese track changing acting styles of the 1940s and hint at the problems those caused for Hitchcock. Schrader notes the recurring fetish-objects (keys, handcuffs) and points out that Vera Miles (Hitchcock’s choice for Vertigo) could never have carried off Kim Novak’s painfully sluttish turn.

Two extended sequences are devoted to Vertigo and Psycho. These allow Jones and his co-screenwriter Serge Toubiana to knot together all the major themes. Vertigo encapsulates the dream elements, and through careful editing Hitchcock/Truffaut turns Hitchcock’s interview remarks into a commentary track under key sequences. Meanwhile, the filmmakers riff freely on what we see. What about Judy’s story? asks Fincher. Scorsese finds “a sense of loss and melancholy.” Judy’s stepping out of the bathroom yields what Gray calls “the single greatest moment in the history of movies.”

But Vertigo wasn’t a huge success, especially for a filmmaker who aimed at arousing the mass audience. The movie that exemplified “pure film,” Hitchcock says, was Psycho. Again our filmmakers are powerfully eloquent about its creative choices (pacing, framing, point-of-view) and, above all, its devastating shocks. It was, says Bogdanovich, “the first time that going to the movies was dangerous.” Psycho’s stupendous popularity, Truffaut remarks in the last edition of the book, made it the capstone of the Master’s career. “I am convinced that Hitchcock was not satisfied with any of the films he made after Psycho.”

Many reviewers of Hitchcock/Truffaut have fastened on moments in the interviews when Hitchcock expressed doubt. Should he have veered off from controlling the “rising shape” of every story? Should he have been “more experimental”? Should he have paid more attention to character rather than situation?

Such questions were raised in Truffaut’s 1983 addendum, but I’m not convinced they’re valid. They presume that plot is less valuable than character, and that thriller plots are somehow intrinsically thinner than other kinds. Truffaut offered the best defense of the power of a gripping intrigue when he suggested that a disciplined format didn’t make things shallow. He suggested that following Hitchcock’s example could be fruitful.

Don’t tell me that it would be inferior or vulgar. Just think of Shadow of a Doubt and Uncle Charlie’s thoughts: the world is a pigsty, and honest people like bankers and widows detest the purity of virgins. It’s all there, but inserted into a framework that keeps you on the edge of your seat.

Hitchcock put it another way: A good film, he remarked, consists of “popular material treated with intelligence.” And that intelligence can take chances. Shadow of a Doubt, Lifeboat, Rope, Rear Window, Psycho, and Family Plot are among Hollywood’s great experiments.

The Figure in the carpet

Storyboard image for Psycho.

My initial aim in undertaking [Truffaut/Hitchcock] was not to make the best-seller list, but to influence and shake up the smug attitudes of the New York critics.

François Truffaut, letter, 1967

Truffaut/Hitchcock had been out for a year when I got my copy in December 1968. Why did I wait? No paperback edition, and the hardback cost a princely $10. That’s about $70 in today’s currency.

That sturdy copy has followed me around ever since, and now, nearly fifty years later, I still find it stimulating. I can’t think of another book on the cinema that has had its influence. Let me count some ways.

It changed tastes. Truffaut tells us that he decided to do the book when he learned that American critics considered Hitchcock as merely a popular entertainer. Not all reviewers needed convincing, though. Robert Sklar found it “likely to become a classic book on the art of the film. . . . No book before this one has made a better case for Hitchcock’s genius or for the French ‘author’ theory of film directorship.”

In the pages of the New York Times, Bosley Crowther had long treated Hitchcock as a talented purveyor of suspense who sometimes gave good value (Rear Window, To Catch a Thief, Vertigo) but who too often favored wildly implausible plots (Strangers on a Train) and “slow buildups to sudden shocks that are old-fashioned melodramatics” (Psycho). Yet the Times granted Truffaut/Hitchcock two admiring reviews. One by Eliot Fremont-Smith declared that Hitchcock had turned out “a surprising number of perfect or nearly perfect movies.” Arthur Knight praised Truffaut’s careful preparation for the encounter and celebrated Hitchcock’s almost unique control over his projects. His films were at once technically adept, emotionally exciting, and bristling with what Truffaut called “moral dilemmas.”

In the pages of the New York Times, Bosley Crowther had long treated Hitchcock as a talented purveyor of suspense who sometimes gave good value (Rear Window, To Catch a Thief, Vertigo) but who too often favored wildly implausible plots (Strangers on a Train) and “slow buildups to sudden shocks that are old-fashioned melodramatics” (Psycho). Yet the Times granted Truffaut/Hitchcock two admiring reviews. One by Eliot Fremont-Smith declared that Hitchcock had turned out “a surprising number of perfect or nearly perfect movies.” Arthur Knight praised Truffaut’s careful preparation for the encounter and celebrated Hitchcock’s almost unique control over his projects. His films were at once technically adept, emotionally exciting, and bristling with what Truffaut called “moral dilemmas.”

As Sklar indicates, Truffaut/Hitchcock gave aid and comfort to auteurists. If you wanted to make a case for creative artistry in Hollywood, Hitchcock was the logical point man—a cinematic virtuoso and a director whose films were instantly recognizable. Andrew Sarris’s first Village Voice review set the tone: Psycho indicated that “the French have been right all along.” The English critics of Movie followed with vigorous analytical essays, while Robin Wood’s probing thematic study Hitchcock’s Films (1965) may have helped establish an audience for Truffaut’s book. Truffaut predicted in 1983 that “By the end of the century, there will be as many books written about him as there are now about Marcel Proust.” The prophecy may well have been fulfilled, and in a new century the literature seems to be swelling even faster.

The book affected tastes in another way, I think. It appeared when French filmmaking enjoyed great prominence in America. Unlike what happened in later decades, in the 1960s and early 1970s we could see virtually everything being made by Truffaut, Varda, Chabrol, Demy, Resnais, Bresson, Rohmer, Melville, and other major filmmakers; Godard sometimes gave us three a year. There were middlebrow hits too, like Sundays and Cybèle (1962) and A Man and a Woman (1966). It seems hard to believe now, but in 1966-1967, twelve numbers of Cahiers du cinéma were published in a handsome English-language edition. Just as important, the year 1967 brought America not only Truffaut’s book but Hugh Gray’s translation of Bazin’s What Is Cinema?

For years afterward, France set the tone for both arthouse distribution and serious cinephilia. Importers brought us La Cage aux Folles, Tous les matins du monde, Amélie, Ma vie en rose, and other vessels of Gallic charm and profundity. Journalists and programmers stalked through French festivals searching for the next big auteurs. Later, academics learned about semiology, neo-Marxism, and Lacanian psychoanalysis from their Parisian counterparts. To this day, critics beg their editors to send them to Cannes and academics beg presses to consider another book on Deleuze. The Hitchbook helped establish France as the home of adventurous thinking about cinema.

Master and disciple

I’d like everyone who makes films to be able to learn something from it, and also everyone whose dream it is to become a filmmaker.

François Truffaut, letter, 1962

It influenced filmmakers. Jones’ documentary highlights the Hitchbook’s enduring power for generations of directors. Wes Anderson says that his copy has fallen to tatters; Fincher read his dad’s over and over, marveling at how the layout of images made the editing patterns apparent. For the young Gray it was “a window into the world of cinema.” The book, says Scorsese, gave courage to a generation: “We became radicalized.” It showed that he and his cohort “could go ahead.”

The book’s impact came from its insider aspects. As Schrader points out, we already had many books about the art of cinema, but Hitchcock shared secrets of craft. How did he get particular effects, like Foreign Correspondent’s plane crash, with the ocean bursting straight into the cockpit? Hitchcock had views on what made film art (montage, mostly) but he also knew, as Fincher puts it, what made it fun. The flagrant virtuosity which Hitch’s detractors attacked was a powerful stimulant for 1960s filmmakers. The chef has taken us into the kitchen and revealed his recipes.

Take camera placement. Many of today’s moviemakers and TV directors are fairly indifferent to the niceties of framing. Scorsese crisply shows how important the high angle is in Hitchcock’s work. You can read it thematically (God looking down) but it’s also elegantly functional. In Topaz, Scorsese points out, the camera’s deviation from the straight-on view is unsettling, and it accentuates the defector’s eye movements. An unexpected, queasily close high-angle is practically a Hitchcock signature, as here from The Man Who Knew Too Much and North by Northwest.

Beyond their craft, Hitchcock films yielded a personal vision of the world. That vision wasn’t a matter of messages articulated in clunky dialogue (vide Stanley Kramer). Hitch’s personality soaked into the very textures of his plots, his characterizations, and above all his attitude toward the story and the audience. The Cahiers critics had found individual expression in the Hollywood studio product, and Hitchcock’s world revealed some fairly sordid corners.

He was obsessed with looking, duplicity, doubles, and hidden identities. Some of his characters, such as Uncle Charlie in Shadow of a Doubt and John Brandon in Rope, are suave sociopaths. In Notorious, the putative hero is a cynical bully, while the Nazi he’s stalking is a gentle and charming husband. A detective obsessed with a woman manages to kill her twice; a husband who wishes his wife dead gets what he wanted. The plots pass harsh judgment on momentary slips, like looking out your back window, listening politely to a loopy train passenger, or placing imaginary racetrack bets. If Ben Jonson lifted sardonic misanthropy to the level of art, why couldn’t Hitchcock?

It’s as if the Movie Brats and those who followed were scoping out the realities of the business they were entering. I think they took hope from a man who made a great deal of money working with stars, flummoxing producers (Selznick in particular), embracing new technologies (sound, widescreen, even 3D), and managing to put an idiosyncratic spin on forced-march projects. It’s easier to reconcile the one-for-them-and-one-for-me dynamic when you remember what Hitch made of assignments like Rebecca, Dial M for Murder, and (even) Topaz. By letting Hitchcock explain the commercial pressures he faced, and the ways he found to dodge or work within them, Truffaut must have given young filmmakers a conviction that they could do personal work in the industry.

Pictures that work hard

The interest of the book will lie in the fact that it will describe in a very meticulous fashion one of the greatest and most complete careers in the cinema and, at the same time, constitute a very precise study of the intellectual and mental, but also physical and material, “fabrication” of films.

Francois Truffaut, letter, 1962

It influenced film criticism too. For one thing, it confirmed the interview as a legitimate critical tool.

Truffaut didn’t invent the cinephiliac director interview, of course. Cahiers and Movie undertook interrogations of directors; Pauline Kael notably mocked Movie for asking Minnelli about a crane shot. But after the revelations of Truffaut/Hitchcock, people who wanted to put movies down couldn’t automatically assume that directors were inarticulate. Yes, they’d recycle their favorite stories, usually mythical; yes, they knew ways to dodge the hard questions; but get them going on craft and you stood a chance of learning something. The god of cinema dwelled among the details, and Hitchcock spread out details with solemn largesse.

Sarris had displayed some of the possibilities in his Interviews with Film Directors (1967 again!). But that book republished interviews already out there. Truffaut’s through-composed marathon showed the power of the interview format as an analytical probe. Today, nobody would think of writing about a filmmaker without consulting published interviews—or better yet, trying to wangle a fresh one. The book-length interview has become a genre, as in the X-on-X series from Faber and Faber and, more lavishly, Matt Zoller Seitz’s books on Wes Anderson.

Furthermore, despite Truffaut’s insistence on Hitchcock’s commitment to “pure cinema,” the book gave new credence to a quasi-literary approach to film criticism. Truffaut repackaged the Cahiers thematic interpretations of Hitchcock. A film’s true meanings were elusive; they had to be unearthed. Films could now be read. Once we could find Catholic guilt in Strangers on a Train and an omniscient, perhaps bemused deity in a high angle, why not extend the strategy to other filmmakers? It seems to me that Truffaut/Hitchcock was a major step toward our apparently endless efforts to find hidden meanings in popular filmmaking.

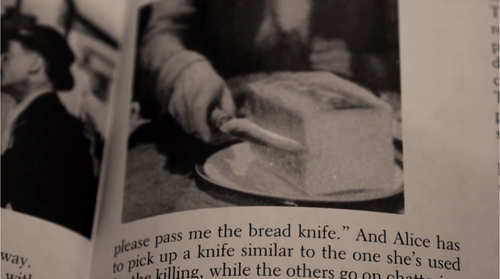

To his credit, Truffaut understood that such reading had to be very close. He needed pictures. His correspondence details his demand that the illustrations “correspond exactly to Hitchcock’s own comments on the film.” Truffaut shrugged off any worries about permissions. Film books of the day, when they included pictures, used production stills—photos taken on the set, which seldom corresponded to what was on the screen. Truffaut used some production stills, but he took pride in packing in genuine frame enlargements, actual images from film prints. I can think of only one earlier author who systematically deployed actual frames to illustrate points of technique: Sergei Eisenstein, in The Film Sense (1943) and Film Form (1949).

To his credit, Truffaut understood that such reading had to be very close. He needed pictures. His correspondence details his demand that the illustrations “correspond exactly to Hitchcock’s own comments on the film.” Truffaut shrugged off any worries about permissions. Film books of the day, when they included pictures, used production stills—photos taken on the set, which seldom corresponded to what was on the screen. Truffaut used some production stills, but he took pride in packing in genuine frame enlargements, actual images from film prints. I can think of only one earlier author who systematically deployed actual frames to illustrate points of technique: Sergei Eisenstein, in The Film Sense (1943) and Film Form (1949).

Today, when hundreds of websites run clips and framegrabs, we need to remember just how bold and tenacious Truffaut was. He borrowed 35mm prints from studio archives and spent three days in London making stills from the British titles not available in France. He could then provide meticulous shot-by-shot presentations of sequences—central to proving the artistry of a man who put editing at the center of film art. The original French edition flaunted its production values, slugging frames from the Psycho shower sequence across front and back cover.

Once Truffaut made such displays thinkable, film criticism could become more analytical. Enterprising writers got hold of prints, projected them incessantly or studied them on editing machines. Most notable was Raymond Bellour, whose 1969 analysis of The Birds (below) pushed analysis to an unprecedented degree of exactitude.

Throughout the 1970s, film critics became more adept at this shot-by-shot study. It was one hallmark of my generation of academic film writers, especially in dissertations. That group included Ted Perry at Iowa (in a dissertation on L’Eclisse, 1968) and NYU scholars Fred Camper, Paul Arthur, and Vlada Petrić. P. Adams Sitney’s trailblazing Visionary Film (1974) brought this sort of scrutiny to the avant-garde tradition. I followed the same line in my 1973 monograph on La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc and in my 1975 dissertation on 1920s French cinema.

Throughout the 1970s, film critics became more adept at this shot-by-shot study. It was one hallmark of my generation of academic film writers, especially in dissertations. That group included Ted Perry at Iowa (in a dissertation on L’Eclisse, 1968) and NYU scholars Fred Camper, Paul Arthur, and Vlada Petrić. P. Adams Sitney’s trailblazing Visionary Film (1974) brought this sort of scrutiny to the avant-garde tradition. I followed the same line in my 1973 monograph on La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc and in my 1975 dissertation on 1920s French cinema.

French scholars were following Bellour’s lead, and a significant school of textual analysts emerged. The BFI magazine Screen opened up similar avenues with Stephen Heath’s 1975 analysis of Touch of Evil. A few teachers started to incorporate frame enlargements as slides for lecture courses. Kristin and I did, while inserting frame enlargements into our publications. We may have been the first to publish a film aesthetics textbook, Film Art (1979), relying on actual shots, not production stills.

Studying films shot by shot was difficult, requiring 16mm or 35mm prints and machinery like analysis projectors and flatbed viewers. To document the shots, you had to take frame enlargements with a bellows and a still camera. By the time videotape and laserdiscs came along, intensive study was far easier. Not until we got DVD technology, though, was it simple to make decent frame grabs to illustrate critical pieces.

Now everybody does what Truffaut did. But let’s remember that we analysts, along with nimble video essayists like Seitz, Kevin B. Lee, and Tony Zhou, owe a debt to Truffaut’s obstinate insistence that “quoting” a film, even partially, allows us to understand it more deeply.

Looking in his direction

This book on Hitchcock is merely a pretext for self-instruction.

François Truffaut, letter 1962

Given Truffaut’s deep admiration for the Master of Suspense, we’ve long assumed that he tried to learn from him. Like Hitchcock, he cared very much about evoking a response from his audience, and he sought as well to master the disciplined technique that could create precise effects. As early as The 400 Blows, he had Hitchcock in mind, as he confessed in the interview.

The recent availability of the 1962 tapes enabled Hitchcock scholar Sidney Gottlieb, in an article teasingly titled “Hitchcock on Truffaut,” to explore portions of the conversation in which Hitchcock comments on a key passage in Truffaut’s film. Truffaut tells Hitchcock of the moment when Antoine Doinel and his schoolmate, playing hooky, catch his mother kissing her lover on the street. Antoine rushes off and she guiltily turns away, telling her lover that her son has recognized her. Hitchcock, who apparently hasn’t seen the film, asks about Truffaut’s intention and tries to visualize the scene.

Jones’ film smoothly incorporates the sequence, letting the men’s voice-over discussion provide a gloss. The passage allows us to pinpoint some important aspects of Hitchcock’s discipline.

Truffaut is shooting on location, with a camera that’s often very far from the action. We see the boys walking right to left in an extreme long shot, and then we cut to another extreme long shot, in which Antoine’s mother and the lover are embracing by a Métro entrance. They are centered, but there’s a great deal of city life in this frame as well, so one can easily miss them. Even if we notice the couple, we can’t clearly recognize the woman as the mother.

In order to make clear what’s happening at the Métro entrance, Truffaut gives us two further shots of the couple. The first conveys only the act of kissing; we can’t really identify the characters. The second shot reveals that the woman is Antoine’s mother.

Truffaut indicates to Hitchcock that he was short of footage, but there’s also the problem of shooting on location. Truffaut could have cut directly from the extreme long-shot to reveal the mother (that is, from my second shot to my fourth). But that would have been rather disjunctive, and without the railing in the third shot we wouldn’t know the characters’ orientation very clearly. The shot of the railing indicates that we’re roughly opposite to the angle taken in the extreme long shot. Still, the whole series—three shots needed to establish that the mother has a lover and is kissing him—is somewhat uneconomical.

Having given us important information about the mother’s affair, Hitchcock might have made us wait longer, raising suspense about whether Antoine would discover the illicit couple. Instead Truffaut cuts immediately to a panning shot of Antoine and his pal passing and looking more or less to the camera. That’s followed by a shot of the mother seeing Antoine and turning abruptly away. The boys also turn away and hurry off.

We’re in the familiar territory of constructive editing and the Kuleshov effect. There’s no establishing shot that includes all the dramatic elements. Similarity of locale, the exchange of glances, continuity of sound effects, and the concept (they see each other) knit the shots together.

Again, though, there’s a certain roughness to the effect. The second shot of the mother looking into the camera seems to be roughly Antoine’s point of view, but that camera setup has already been given us as an “objective” shot of her kissing her partner. Apart from the eyeline, there isn’t any marker of the second one as subjective—such as a sidelong camera movement that might correspond to Antoine’s walking viewpoint. POV shots can be slippery in classical filmmaking, so it’s not exactly an error, but Truffaut gave up the chance for a more nuanced variant.

The couple’s placement remains a little vague in this shot too, again because there’s no railing to orient us. If the mother is more or less blocked by her lover (her back is to the railing), her later glance at Antoine must fall quite far down the sidewalk on her left. But when he passes he’s further up the sidewalk, on her right. Yet he’s supposedly looking more or less directly at her.

Put it another way. In the physical terms given by earlier shots, the lover’s back would hide the mother from Antoine until he was quite far down the sidewalk on her left. He’d have to turn back to see her. Yet the boy seems to be looking at her from a position more or less opposite her, in effect “through” the lover’s back.

Plainly we get the point of the scene. But there’s a certain roughness to the presentation. That may be why Truffaut felt he needed the return to the railing setup to show the mother turning away, followed by an explicit underscoring of what just happened through dialogue.

Hitchcock, a little sadly: “I would’ve hoped that there was nothing spoken.”

Truffaut admitted to Hitchcock that he didn’t have enough footage and was forced to intercut the shots too much. “In the cutting room it was absurd. . . . It was less good than if I’d thought it out beforehand. Then I would have had a variety [of shots].”

In the interview Hitchcock goes on to remake the sequence at one remove. He suggests that we could start with Antoine walking and markedly seeing the mother. Then we see her turn, “looking in his direction.” The boy turns away, then she turns away. Simple and straightforward.

To get a concrete example, consider how Hitch directed a scene of one person catching another by surprise. In Stage Fright, the blackmailing maid Nellie Goode has come to the garden party to squeeze more money from Eve Gill. Hitchcock shows us that Nellie is present and then shows Eve and Ordinary Smith approaching unawares in a distant shot—more or less from Nellie’s optical standpoint.

Thus the shot of the person seen is anchored in relation to the person seeing. After a reverse angle on Nellie, with the long-shot scale more or less matching its mate, we get a shot of Eve noticing Nellie.

We have another piece of constructive editing, but we scarcely notice the absence of a master shot. The geography is crystal clear, not least because of the marked eyeline. And now, as in Truffaut’s scene, an objective framing becomes subjective. We get a parallel series of shots, one setup showing Nellie advancing, the other a tight framing just on Eve, who halts Nellie by signaling with her eyes and mouth. On the couple, the framing has gone from long-shot to two-shot to single.

When Nellie stops, puzzled, Eve launches her plan to send Smith off to her girlfriends. Eve leaves, Smith follows, and we’re back to Nellie watching in annoyance.

Bare-bones though it is, this sequence is more complicated than Truffaut’s, because the third party, Ordinary Smith, mustn’t be allowed to notice Nellie. We take it for granted that the mother’s lover doesn’t recognize Antoine, but Eve must actively distract Smith. Moreover, there is dialogue running throughout this action, as Smith chatters away to charm Eve. So we have the familiar Hitchcock technique of playing banal dialogue in counterpoint to suspenseful imagery.

Everything that happens—Nellie waiting in ambush, the exchange of looks, the fluttering expressions on Eve’s face, the policeman’s obtuseness—is rendered fully. The functional precision of this simple passage shows why Hitchcock liked shooting in the studio. He could control all his angles, eyelines, and shot scales exactly. Truffaut had to make do with what he could grab on a very busy location. Still, as he points out, he compensated somewhat by the very tightly controlled scene later in 400 Blows, when Antoine’s parents come to school. There the closed conditions of the classroom allowed a sharper articulation of glances and camera angles. It’s no set-piece, but it’s a tidier piece of work, somewhat Hitchcockian.

The Truffaut thriller

Mississippi Mermaid (La Sirène du Mississippi).

I have adapted too many novels, especially American novels. Oddly enough, it has become quite clear that (with the exception of Jules et Jim) my intentions have been better understood when I have filmed such original screenplays as Les 400 Coups, Baisers voles, L’Enfant sauvage, and La Nuit américain than when having filmed Irish and Goodis.

François Truffaut, letter, 1974

Mystery novels were popular in France well before World War II, and films prefiguring the tone of noir cinema, such as Pépé le Moko and Le jour se lève, began to appear in the late 1930s. The Nazi occupation, by shutting off American films, stimulated the French industry, which during the war produced some important films of crime and suspense. Over the same years Simenon, who wrote both detective stories and psychological thrillers, became a respected literary figure. But it was not until the postwar period that the roman noir became a major literary trend. That was partly due to new publishing initiatives like the Série Noire collection (established 1945), which translated a great many American and English crime writers, and the Fleuve Noir series (1949), which cultivated French authors. Within this lively milieu, the team of Boileau and Narcejac achieved fame with novels that became the sources for Les diaboliques and Vertigo.

The burst of translations of American authors in the 1940s and 1950s paralleled the postwar flood of US films, including films noirs. Truffaut, like his Nouvelle Vague friends, grew up reading crime fiction and watching Hollywood thrillers. He was fourteen years old when Double Indemnity was released in Paris, and twenty-two when Rear Window was. Over those same years crime writers like Cornell Woolrich and David Goodis were being translated in French editions. Writing of Woolrich, whom he knew under the pseudonym William Irish, Truffaut recalled:

The burst of translations of American authors in the 1940s and 1950s paralleled the postwar flood of US films, including films noirs. Truffaut, like his Nouvelle Vague friends, grew up reading crime fiction and watching Hollywood thrillers. He was fourteen years old when Double Indemnity was released in Paris, and twenty-two when Rear Window was. Over those same years crime writers like Cornell Woolrich and David Goodis were being translated in French editions. Writing of Woolrich, whom he knew under the pseudonym William Irish, Truffaut recalled:

The cinephiles of my generation knew Irish before they had read a single line of his, because many of his novels and short stories were the basis of the bizarre and fascinating films of the forties and fifties, such as Jacques Tourneur’s The Leopard Man, Robert Siodmak’s Phantom Lady, Roy William Neil’s Black Angel, John Farrow’s Night Has a Thousand Eyes, Ted Tetzlaff’s The Window, and especially one of the best if not the best Hitchcock film, Rear Window.

Truffaut came to admire the novels’ authors for their modesty, their professionalism, and their ability to create, behind a pulp surface, “free works” that opened onto sadness, dream worlds, and lost memories.

No wonder, then, that when the young directors sought to make films of wide popular appeal, they turned to noir. If you wanted to generate emotion in a wide audience and to tackle a project that posed formal and technical challenges, some version of the thriller seemed a promising way to go. Claude Chabrol, co-author of a book on Hitchcock, built his career on suspense films, sometimes adapted from English-language authors. More notoriously, Jean-Luc Godard’s Made in USA was an unrecognizable rendering of a crook novel by the great Donald Westlake. As late as 1986 Godard undertook to adapt a James Hadley Chase novel for French television.

Truffaut turned to American thrillers when he wanted a change of pace from his dramas. Naturally the spirit of Hitchcock hovered over such projects. By looking at some problems he faced, we can get another angle on what he learned, or did not learn, from the Master.

As Truffaut became more wedded to shooting in studio conditions, he might have handled scenes with a degree of Stage Fright precision. But he had a predilection for lengthy takes, with fairly open horizontal staging covered in simple, lateral camera movements. Often shooting in anamorphic widescreen, something Hitchcock never did, Truffaut needed to fill up the horizontal expanse, Fluid panning and tracking from a fair distance seemed a good solution. But that meant sacrificing Hitchcock’s urge to build scenes out of details, tight shots of facial expression or close-ups of significant props.

If Truffaut needs a detail, he may accentuate it with an abrupt close-up. In The Bride Wore Black, Julie Kohler wants to be alone with her victim. When the victim’s friend brings her a drink, she dumps it into a flower pot, signaling that he should take off.

Much later, the friend casually waters his own African violet. (Did he inherit his dead friend’s plant?) The gesture reminds him of where he’s seen the woman before. The cut-in detail functions as a sort of flashback for us.

The example indicates Truffaut’s inclination to use close-ups of faces and objects to punctuate the master shot—a more traditional and conservative choice than Hitchcock’s urge to build an entire scene out of bits.

Truffaut confronted larger narrative problems in the thriller genre. One involves the protagonist. In the classic thriller, as opposed to the detective story, the protagonist is either the criminal, the victim, or a bystander drawn into the intrigue (as in Rear Window). And typically our range of knowledge roughly corresponds to that of the protagonist.

In Truffaut’s first thriller, Shoot the Piano Player, he adheres fairly closely to the standpoint of the protagonist, as presented in the source novel, David Goodis’ Down There (1956). Likewise, Mississippi Mermaid attaches us to Louis Mahé, a plantation owner who has married a woman whom he knows only from letters. He eventually discovers that she’s an impostor and a hardened criminal. Like its source, the Cornell Woolrich novel Waltz into Darkness (1947), the film restricts us quite closely to Mahé’s range of knowledge. At only one point do we leave Mahé and follow his business partner, who glimpses the wife quarreling violently with another man. Nothing much comes of this, but we are alerted to her possible treachery.

Another Woolrich novel, The Bride Wore Black (1940), has a bolder structure. The protagonist is the woman bent on revenge who kills five men, one by one. The viewpoint shifts from victim to victim. After the first killing we know, as the men don’t, that this woman who enters their lives is a murderer, so the suspense comes in wondering whether they’ll escape. Each section of the book concentrating on a victim ends with a chapter devoted to the policeman who is trying to make sense of these apparently random deaths. He becomes a secondary protagonist.

By contrast, Truffaut makes the policeman merely a walk-on (although a friend of two victims, the plant-waterer seen above, plays a minor investigative role). Instead Truffaut attaches us to Julie more strongly, so that we follow her from crime to crime. As she calculates ways to enter each man’s life, the emphasis falls on how she plays to each one’s fantasies. While early victims are given privileged scenes apart from Julie, as the film goes along we are bound more closely to her. Truffaut’s belief in overpowering love traces how she dedicates her life to avenging her dead husband.

By contrast, Truffaut makes the policeman merely a walk-on (although a friend of two victims, the plant-waterer seen above, plays a minor investigative role). Instead Truffaut attaches us to Julie more strongly, so that we follow her from crime to crime. As she calculates ways to enter each man’s life, the emphasis falls on how she plays to each one’s fantasies. While early victims are given privileged scenes apart from Julie, as the film goes along we are bound more closely to her. Truffaut’s belief in overpowering love traces how she dedicates her life to avenging her dead husband.

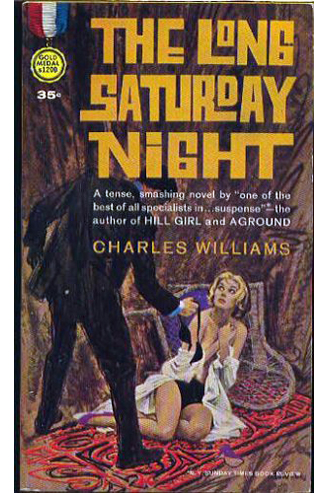

Another gender shift is followed in Vivement, Dimanche! (Confidentially Yours; “Can’t Wait for Sunday!”). Charles Williams’ novel, The Long Saturday Night (1962), is told in the first person by a man hunted by the police for a pair of murders. We’re attached to him as he flees, investigates on his own, and hides out in his real estate office. At certain points he sends his secretary out to do some snooping, and she plays a critical role in trapping the real killer. But clearly the accused man functions as protagonist.

In adapting the book, Truffaut turns his lover, Fanny Ardent, into a detective. She will risk her life for the man she silently adores: “an ordinary woman, a valiant secretary, determined to prove her boss’s innocence.” As a result, early portions of the film show the trap closing around the self-centered, quarrelsome Vercel. Once he gets immobilized hiding in his office, our attachment shifts to Barbara, the resourceful secretary, and we follow her investigation. The structure is a bit like that of Phantom Lady, in which a woman tries to find evidence to clear her imprisoned lover. Eventually Vercel and Barbara learn to work together. The situation echoes those American mystery-comedies like The Ex-Mrs. Bradford (1936) and Fast Company (1938), centering on a married couple who solve a crime in tandem. Here, though, the grudging cooperation creates the romance.

The selection of a film’s protagonist and center of consciousness impinges on a second problem that’s worth considering. A thriller, while not having the structure of the classic detective tale, may harbor some mysteries. That is, the reader/viewer is not given some key information about past or offstage events. At some point that information must be presented, so the question is: When?

Timing the Big Reveal

Vertigo.

Like the detective story, the thriller often saves the Big Reveal for the end. Hitchcock employed this in The 39 Steps, Spellbound, and Stage Fright. But Hitchcock plays with the Big Reveal. Shadow of a Doubt doesn’t fully confirm Uncle Charlie’s guilt until Young Charlie realizes it, about halfway through the film. Creating the Big Reveal through a switch in attached viewpoint helps him here, as Young Charlie has become the protagonist. In Frenzy, the killer’s identity is revealed to us thirty minutes in, so that we can feel suspense as he approaches other victims and as the innocent man seems more likely to be charged.

Boldest of all, however, is the Big Reveal in Vertigo. The original novel saved it for the very end, but Hitchcock made a daring choice. After nearly 100 minutes of being attached to Scottie Ferguson, we get a scene fully 30 minutes before the end that suddenly gives us access to what another character knows. A flashback, guided by Judy’s anxious look to the camera, clears up the entire situation. On the tape, Hitchcock says:

What will Stewart say when he finds that this is one and the same woman? This is your main thought. In addition, you have this added value. You watch the woman resisting being changed back. . . . Now you have a woman who realizes this is a man who’s practically unmasking her.

The wider range of knowledge not only enhances suspense but makes Scottie a more pitiable figure, as we realize that his weaknesses have been exploited. The fact that Judy writes the letter to explain it also measures the extent of her love for him and her shame at participating in the murder scheme. Narrationally, the film dispels mystery to heighten suspense and the romantic drama—as well as the “sex-psychological side,” as Hitch calls it, evoking necrophilia.

In their conversation Hitchcock and Truffaut often turned to issues about when to reveal backstory, and Truffaut took some of the lessons to heart. He uses the option playfully in Vivement, Dimanche! in two misleading ellipses. At one point we see Vercel going back to his house at night, and then we cut to Barbara in her theatre rehearsal. Next morning in the office, Vercel tells her his wife is dead, and we get a flashback that replays his arrival home but prolongs it to include his discovery of her corpse. Later, when Barbara discovers the secret panel in the lawyer’s office, we again cut away to a new scene, and only later does her flashback explain what she discovered. Since the lawyer is obviously the killer (as isn’t true in the book), I take these as narrational filigree aiming to keep us engaged.

Vivement, Dimanche! saves its Big Reveal for the end, as does its source. In Shoot the Piano Player, the long flashback to Charlie’s concert career that takes up the middle stretch likewise corresponds to a centrally placed flashback in Goodis’ novel. Mississippi Mermaid makes Marion’s confession the fulcrum of the film; in choosing to join her on the run, Mahé becomes a criminal himself. Woolrich’s novel has the same structure, making the mystery component occupy the first half and the suspense-pursuit component dominate the second.

Something closer to the Vertigo gambit takes place in Truffaut’s handling of The Bride Wore Black. In the original novel, Woolrich postpones revealing Julie’s motive until the very end of the book. The trauma impelling her is the murder of her husband as they were leaving the wedding ceremony. Through dramatic irony, in her confrontation with the cop, she learns that her interpretation of that event was mistaken. The men she killed were innocent. Her fiancé, whom she revered, was a petty criminal shot by other crooks.

By making Julie the protagonist, however, the film puts a greater stress on the thwarted love that turns to righteous violence. (Julie’s name, Kohler, suggests colère, wrath.) Truffaut enhances this element of passion-beyond-limits through a choice about exposition. Instead of saving the Big Reveal for the end, he exposes Julie’s motive in two steps. As her second victim dies, we get a brief flashback to the wedding at which her husband is shot. This encourages us to start to sympathize with her vengeance campaign.

At the film’s midpoint, when Julie traps her third victim, there’s a full flashback to the wedding, and we learn what led to the husband’s death. No rival gangsters are involved. Five irresponsible men playing with a rifle have robbed Julie of happiness. Now, thirty-five minutes into the film, we understand Julie’s motive and can sympathize as she proceeds to use the men’s vanities against them. In a finale wholly devised for the film, she is resolutely unchastised and manages to polish off her last victim in prison. Unlike Woolrich’s bride in black, who regrets her tragic error, Truffaut’s avenging angel has remained pitiless to the bloody end.

The revelation of Julie’s motive doesn’t have the force of Judy’s flashback in Vertigo, which breaks very abruptly from our lengthy attachment to Scottie. But as in Hitchcock’s film, a Big Reveal before the climax expands our awareness of the dramatic forces at work and increases our sympathy for the protagonist.

Truffaut will never be as experimental as Hitchcock; as Andrew Sarris once remarked, between form and vitality Truffaut chooses vitality. And I think he has a tendency to sabotage his thriller elements. He provides a quasi-optimistic ending to Mississippi Mermaid and he reveals, in Baisers volés, that an apparent stalker nurtures a pure love. I once argued that this is Truffaut’s “Renoirian” side, letting him break noir formulas in favor of something more poignant. Still, I think that in his quiet way he absorbed some lessons of the Master.

Kent Jones’ film opens up the Hitchcock—Truffaut relationship in fresh ways, and it stirs us to follow up the ideas that intrigue us. It’s the most stimulating film about a director that I’ve ever seen, teaching you about not just Hitchcock but cinema in general. Just as interviews can illuminate the films we love, so can documentaries, if they blend admiration with analysis. Popular material, yes, and treated with intelligence.

Thanks to Kent for sharing Hitchcock/Truffaut with me, to Kelley Conway for help with a French translation, and to Lea Jacobs and Kristin for identifying the plants.

A bold vertical cover design made the Hitchbook universally known as Truffaut/Hitchcock, but the title is, strictly speaking, “Hitchcock by François Truffaut, with the collaboration of Helen Scott” (Simon and Schuster, 1966). The revised edition, with the same title, came out in 1983. Truffaut’s comments about Hitchcock’s morale after Psycho are on p. 328 there.

The broadcast version of the interviews is online at slashfilm. The portion discussing the 400 Blows scene is in Part 22, starting around 11:30; the material on Vertigo is in Part 21, starting at 17:28. For an in-depth report on differences between the tapes and the book, see Janet Bergstrom, “Lost in Translation? Listening to the Hitchcock—Truffaut Interview,” in Thomas Leitch and Leland Poague, A Companion to Alfred Hitchcock (Wiley Blackwell, 2014), 386-404.

Quotations from Truffaut’s letters come from François Truffaut, Correspondence 1945-1984, ed. Gilles Jacob and Claude de Givray, trans. Gilbert Adair (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1989), 192, 218, 311, 426. The Rear Window review is in The Films in My Life, trans. Leonard Mayhew (Simon and Schuster, 1975), 77. Truffaut’s intentions about Vivement, Dimanche! are discussed in Antoine de Baecque and Serge Toubiana, Truffaut: A Biography (Knopf, 1999), 373. The letter in which he talks about changing American critics’ minds is mentioned here as well, on p. 194.

The reviews I’ve quoted are Robert Sklar, “Two Masters of Cinema,” The Reporter (8 February 1968), 48; Eliot Fremont-Smith, “Dial H for Suspense,” New York Times (11 December 1967), 45; and Arthur Knight, “With the Master,” New York Times (17 December 1967), 6, 27. In a nuanced review, Leo Braudy charged that Truffaut’s concern with technique diverted him from analyzing the films’ more disturbing aspects (“Hitchcock, Truffaut, and the Irresponsible Audience,” Film Quarterly 21, 4 (Summer 1968), 21-27). Jones’ film, thanks to his script and his commenters, happily goes in that direction.

Raymond Bellour’s “System of a Fragment (on The Birds)” is available in a revised version in The Analysis of Film, ed. Constance Penley (Indiana University Press, 2000), 28-67. He pays tribute to Truffaut’s “great book of interviews” with Hitchcock and recalls that Truffaut helped him prepare his analysis by providing a shot breakdown based on the release print.

Sidney Gottlieb, “Hitchcock on Truffaut,” Film Quarterly 66, 4 (Summer 2013), 10-22 considers the two Hitchcockian scenes in 400 Blows in detail. The portions I’ve quoted are available in Sid’s other version of the piece, “Hitchcock on Truffaut,” in Hitchcock on Hitchcock 2 (University of California Press, 2015), 134-136. My quotation about handling popular material with intelligence comes from the same volume, in the 1930 essay “Making Murder!,” 166.

Truffaut’s comments about inserting serious concerns in a thriller framework come from a 1962 Cahiers interview in which he imagines Chabrol’s Bonnes femmes as done by Hitchcock (“The Shop-Girl Vanishes”). In the same interview Truffaut confesses that he modeled Shoot the Piano Player too closely on Goodis’s novel and regrets including the flashback. See “Interview with François Truffaut (second extract),” in Peter Graham, ed., The New Wave (Doubleday, 1968), 94-95, 108. Truffaut discusses American thriller writers in “Les Espadrilles de William Irish,” in Le Plaisir des yeux (Cahiers du cinéma, 1987), 133-137. I take Sarris’s remark about form and vitality from “François Truffaut,” in Interviews with Film Directors (Bobbs-Merrill, 1967), 447.

There’s a fair amount about Hitchcock on this site; you could start here. The high angle in North by Northwest is discussed in Chapter 4 of our Film Art: An Introduction, where we point out that Hitchcock makes a joke of it. (Van Damm suggests that silencing Eve is a matter “best disposed of from a great height.”) For a discussion of how Hitchcock’s work relates to 1940s American suspense fiction, see the web essay, “Murder Culture.” As usual, Mike Grost’s encyclopedic survey of crime and mystery fiction is a powerful resource; see in particular his discussion of “the Woolrich school.”

Psycho; Vivement, Dimanche!

A legendary film returns from the realm of the lost

Kristin here-

Nearly two years ago, when Flicker Alley released its wonderful collection of French films made by the Russian-emigré production company Albatros in the 1920s, I wrote, “Now, if Flicker Alley will manage to release its long-rumored project, Albatros’s 1923 serial, La Maison du mystère, starring Mosjoukine, we will all be doubly grateful.” That release arrived yesterday.

For decades, La Maison du mystère remained one of the fabled lost films of the silent era. It was an enormous popular success upon its release in 1923, and critics praised it as well. Even Louis Delluc, who highmindedly promoted cinema as a realistic, restrained art, grudgingly said of it, “La Maison du mystère is a serial. They are a necessity. So be it. This one is intelligent, sober, frank, genuinely human.”

Watching the film today, “sober” seems an odd term. Despite its many arty moments, the film presents a conventionally melodramatic story, with Mosjoukine playing a struggling factory owner betrayed by a villainous “friend” who is secretly in love with his wife. He is falsely accused of murder, presumed dead after an escape from hard labor, and operates under various disguises. Blackmail, flashy escapes, a suicide pact, and flagrant coincidences all play roles. Yet in contrast to the fantastical ones of Louis Feuillade from the 1910s, the ones we are most familiar with today, Le Maison du mystère paid more attention to characterization and moved at a less breakneck pace. (Feuillade had moved into this sort of dialogue-centered melodrama himself in the 1920s, as in Les Deux Gamines, 1921, but these films are rarely watched today.)