Archive for the 'National cinemas: France' Category

JCC

The Milky Way (La Voie lactée, 1969)

DB here, writing from a gray Brussels:

All the problems of a film are in the script.

When a film is made, the screenplay disappears.

When you consider what a scene needs to express, ask: How can the actor act it?

When you’re writing a scene, try to act it out yourself.

Rather than letting dialogue explain the action, let the action explain the dialogue.

It will always be possible to make films. Don’t forget to make cinema.

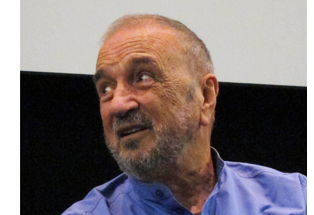

These and other epigrammatic insights flowed easily from Jean-Claude Carrière during his visit to the Cinematek of Belgium and the annual conference of the Screenwriting Research Network. I hope to devote a later blog to other attractions of this stimulating get-together. For now, a brief tribute to the volcanic charm of the legend known as JCC.

JCC entered cinema under the aegis of Jacques Tati. Tati wanted someone to turn M. Hulot’s Holiday and Mon Oncle into novels, and the very young writer seemed the right candidate. But Tati quickly learned that JCC didn’t know how a film was made. So he assigned Pierre Etaix and the editor Suzan Baron to tutor the lad in the ways of cinema. First lesson: Go through M. Hulot on a flatbed viewer, examining the script line by line while watching shot by shot. As a result, JCC says, he began to understand “the film that you don’t see.”

In the course of his career, JCC has written novels, plays, essays, screenplays, even a scenario for a graphic novel. In the process he became one of the most distinguished and respected screenwriters of the last fifty years. His most famous collaborations were probably with Buñuel, from Belle de Jour (1967) to the master’s last film, That Obscure Object of Desire (1977). He worked with Etaix (The Suitor, 1962), Forman (Taking Off, 1971), Schlöndorff (The Tin Drum, 1979), Godard (Every Man for Himself, 1980), Wajda (Danton, 1983), Oshima (Max mon amour, 1986), Kaufman (The Unbearable Lightness of Being, 1988), Peter Brook (The Mahabarata, 1989), Malle (Milou en Mai, 1990), and Haneke (The White Ribbon, 2007). He has also become known for his work on major French costume pictures and adaptations, such as Cyrano de Bergerac (1990) and The Horseman on the Roof (1995), as well as work with younger directors, including Wayne Wang (Chinese Box, 1997) and Jonathan Glazer (Birth, 2005). His TV scripts are numberless.

Directors both young and old come to him for the unique forms of collaboration that he offers. Instead of going off to write the screenplay, JCC meets frequently with the director. (Sometimes the director stays in his house.) He might ask the director to write the script for him, and they go over the result. Through these methods, JCC tries to help the director “find the film that he wants to make.” But his methods are flexible, tailored to the director’s temperament. When he was working with Buñuel, the men met daily to tell each other their dreams, some of which wound up in The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (1972). Similarly, JCC prefers to meet with the actors before production, letting them try out the parts so that he can revise things for each one’s habits of speaking. For Cyrano, Depardieu read the entire play aloud, taking all the parts, and then listened to it over and over on cassettes to refine his interpretation.

Brussels gave JCC a busy twenty-four hours. In conversation with the critic Louis Danvers he introduced a Cinematek screening of The Milky Way. He gave a keynote address for the Screenplay Network conference, and he participated in a panel discussion with members of the Flemish Screenwriters Guild at the film school RITS. These sessions ranged freely over his career and his conceptions of filmmaking. He believes that there is a language of film that sets it apart from other arts. That language is grounded in the play of meaning and emotion that comes from putting one shot after another.

He explained the point through an example that seems at first to be a restatement of the classic Kuleshov effect. In Shot 1, a man in his apartment looks out the window. Shot 2: The street. A woman is walking with another man. We’ll assume that our man is seeing them. Shot 3: Our man reacts.

But contrary to Kuleshov’s dictum, his facial expression should not be neutral. In fact, his expression tells us how to understand the scene. If the man looks upset, we surmise that he’s jealous. If he’s benevolent, we assume that the woman is a friend, his daughter—or a flirt. The filmmaker needs not only techniques like framing and cutting, but also the performances of actors.

Now cut to the woman in her bedroom brushing her hair. We need to make sure the audience understands that it’s the same woman, so maybe we have to go back and add a shot to the earlier scene, a closer view of her in the street. This constant flow and readjustment of images is based on guiding the spectator discreetly but firmly through the action. The audience isn’t aware of this “secret film,” but it governs everything the viewer thinks and feels.

For this reason, the young screenwriter needs to learn everything about how a film is made. When JCC was acting in The Wedding Ring (1971), a film starring Anna Karina, he learned that simply getting up from a couch can be a complicated matter. When he stood up spontaneously, dipping forward to lift his body, the cinematographer had to correct him: It looked awkward on film. JCC learned that he had to stand up in an unnatural way, with his feet spaced and his back rigid, so that it looked smooth on film. The screenwriter must know that even the smallest moment of action, easy to write in the comfort of a study or a café, is subject to the contingencies of production.

For this reason, the young screenwriter needs to learn everything about how a film is made. When JCC was acting in The Wedding Ring (1971), a film starring Anna Karina, he learned that simply getting up from a couch can be a complicated matter. When he stood up spontaneously, dipping forward to lift his body, the cinematographer had to correct him: It looked awkward on film. JCC learned that he had to stand up in an unnatural way, with his feet spaced and his back rigid, so that it looked smooth on film. The screenwriter must know that even the smallest moment of action, easy to write in the comfort of a study or a café, is subject to the contingencies of production.

Where to get ideas for films? From the classics, of course. (“Balzac is the greatest screenwriter—every character is vivid.”) But above all you must observe reality. Tati taught JCC to sit vigilantly in a café. Study everyone who passes. Notice details. Imagine the person as a character in a story. Give him or her some motivations. What you must do is “find the fiction in the reality.” When JCC presided over the French film school La FEMIS, he promoted an exercise that required students to move out into a public space, like a market, and come back with stories about the people they saw. JCC praised Tati’s genius for spinning gags and situations out of passing life—“as if God had created the world so that it could furnish a film by Jacques Tati.”

JCC must be one of the few screenwriters who doesn’t gripe about his work being changed in its final incarnation onscreen. He sees the screenplay as ephemeral, the chrysalis for the butterfly. Once you accept the fact that your text must be sloughed off on its way to becoming cinema, you can take joy in your work. For young people, JCC advised the same relaxed, exploratory attitude. Conceive of yourself as a writer, able to move across media. The venues for your writing are constantly changing, so be prepared to write for television as well as film, to write comics and documentaries and plays. Above all, “Don’t despair of the future of cinema. It’s wide open.”

Jean-Claude Carrière turns eighty next week.

The best introduction to Carrière’s career and ideas that I know is his book The Secret Language of Film (Faber, 1995). Some of this text overlaps with Exercice du scénario (FEMIS, 1990), coauthored with Pascal Bonitzer. That book is worth reading too, but it hasn’t to my knowledge found English translation. An illuminating interview is here.

P.S. 11 September 2011: Thanks to Jonathan Rosenbaum for correcting an error in JCC’s filmography, which I’ve rectified above. Jonathan also remarks:

I assume that you know, by the way, that Carrière appears in a scene of Certified Copy, playing something similar to the “wise old guru” role played by the Turkish taxidermist in Taste of Cherry and the doctor in The Wind Will Carry Us.

I did know and should have worked it in!

P.P.S 22 September 2011: A panel discussion with Jean-Claude Carrière held during the conference is available here. Although the site is in Dutch, the discussion is in English. Thanks to Ronald Geerts for the information.

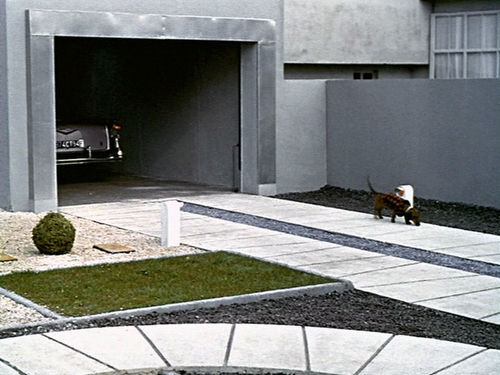

Mon Oncle (1958). “I followed Tati more or less everywhere, usually with Etaix, attending projections followed by long anxious discussions. (‘Can we clearly see the dog’s tail go past the electric eye that shuts the garage door? Yes? Clearly? You’re sure people will see it?’)

Looking different today?

Johan (1921).

DB here:

Earlier this month Manohla Dargis wrote a New York Times article on how we watch, or should watch, films that some audiences consider slow and boring. She suggested that appreciating such films requires us to cultivate fresh ways of seeing. Her article and my interests coincide on this matter, so I wrote an entry developing some ideas about viewing strategies and skills. This piece also, happily, brought new readers to Tim Smith’s experiment in tracking viewers’ scanning of a scene in There Will Be Blood.

Today I explore another angle on the problem of how to watch movies that aren’t the normal fare. But this time what’s abnormal for us was once normal for everybody. I look at the pictorial possibilities that emerged in the 1910s. Those possibilities are of interest if we want to fully understand film history, but they offer some mysteries as well. If viewing movies involves skills, did people a century ago have the ones we have? Or did they employ different viewing habits, ones that we have to learn?

Editing, your imaginary friend

I write from my annual research trip to the Royal Film Archive of Belgium, now known as the Cinematek. For some years, I’ve been looking into feature filmmaking of the 1910s. On every visit I’ve found rich material, movies off the beaten path that give me a sense of the immense creativity of that early period. (See the bottom of this post for links.) The official classics of these years, by Chaplin and Griffith and Fairbanks and Bauer and Gance and Sjõström and Feuillade, remain remarkable, and Kristin’s latest entry makes a case that Alberto Capellani belongs among this heroic company. But you can also find extraordinary moments in ordinary movies. Even the most banal film has something to teach me about what choices faced the era’s filmmakers.

One of those teachable elements involves the ways in which directors guide our attention. We know that editing serves to shift our attention from one part of a scene to another, but so does judicious staging. This is one of the great lessons of the cinema of the 1910s. Watching films from that period convinced me that the craftsmanship of Anderson in There Will Be Blood, and of other directors reliant on long-take ensemble staging, has deep roots in filmmaking tradition. But the golden age of cinematic staging was relatively brief, and it was eclipsed by an approach based largely on editing. That approach is, essentially, still with us.

Let’s start by appreciating the technique that became most prominent. By the late 1910s, Hollywood filmmakers had more or less perfected what we’ve come to call the classic continuity editing system. The camera could penetrate the most intimate exchange, breaking it up into intelligible bits. Here, in a minor Metro film called False Evidence (1919), Madelon tries to persuade her father that she, not her boyfriend, is responsible for a crime.

After giving us father and daughter close together in profile, the camera has somehow squirmed in between them, showing each one in a tight 3/4 view. Or rather, the cutting has forced the staging to pull the characters a bit apart so that each one can have a frame to him- or herself. Spatial plausibility gives way to dramatic urgency; what we care about are clear views of their emotional responses. As long as the spatial relations remain clear, they can be just approximately consistent.

For a little more finesse, we can look–as usual–to Rio Jim. William S. Hart’s films are among the most visually elegant and ambitious of this period, and even his less-known items seldom disappoint. John Petticoats (1919) gives us “Hardwood” John Haynes, a rough-edged logger who finds he has inherited a New Orleans dressmaking shop. His comic introduction to the place, in the company of a new friend he’s made, uses editing to tease us. The two gents come in, with John bewildered by a feminine world he’s never known. They pause before a model sashaying on the stage, and when she pauses, she’s blocked by the Judge’s body.

We’re left without the revelation of her appearance, but when her dresser comes forward to peel off her wrap, we cut, in effect, “through” the Judge to get a clear view of the disrobing. The blocked shot teased us, but the cut pays us off.

Now that the model bares a lot more than before, the biggest tease begins. How will John react? The answer is given in the next shot, a nearly 180-degree shift from the earlier framing of the men that incorporates a mirror in the background to keep the model onscreen.

Thanks to a cut, action and reaction are given in the same shot–in fact in the same zone of the frame, the center.

A pass, a pat, a squeeze

Fabiola (1918).

Many European directors were moving in the same direction as Lambert Hillyer in John Petticoats. Although they might not use as many shots or as many different angles as their American counterparts, they were confidently breaking their scenes up into closer views, often through axial cuts that take us straight into or out of the action, along the lens axis.

Take Enrico Guazzoni’s Fabiola (1918), henceforth known to me as Fabulosa. Normally I consider the Roman oppression of Christianity one of the least fertile topics for a good movie, but Fabiola proves me wrong. For one thing, the title names a rather unpleasant woman who barely figures in the action until the climax. For another, Guazzoni proves an adept filmmaker. I was struck by those immense sets that distinguish the Italian costume drama, the dazzling lighting (see above), and the skilful editing.

Our introduction to Fabiola comes as she sits disdainfully in her household, attended by servants. After a long shot showing off the set, an axial cut takes us closer to her.

She turns as her tardy servant Sira comes in. Having stretched her elegant neck, Fabiola tips her head forward slightly, in a bob of disdain.

Another axial cut takes us still closer to her. And in a few frames her gesture, at once haughty and angry, is repeated. (The streak across the first image below is the splice, so this is the very first frame of the next shot.)

This, I think, is no mistake. The matches on action elsewhere in the film are quite precise, and indeed earlier Italian films have shown that directors used this device skilfully. Guazzoni wanted to stress Fabiola’s head movement, and he used the same tactic, the overlapped action match, that some Americans would use and that many Soviet directors drew on later. This slight accentuation of Fabiola’s gesture is a vivid way to introduce the character, caught in a characteristically scowling moment. Very soon, in a fit of pique she’ll jab Sira with a hatpin.

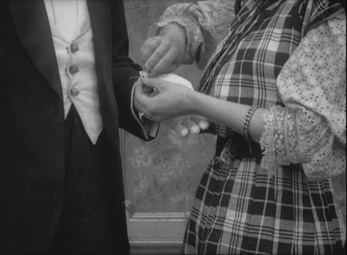

On the whole, keeping the setups close to the camera axis is the default value in Fabiola. For the Americans, though, cutting made the camera almost ubiquitous. A year after John Petticoats, O’Malley of the Mounted (1920), lets Lambert Hillyer again resort to intelligible shifts of setups. O’Malley, played by Hart, has gone undercover to track a killer. Posing as a robber, he has joined an outlaw gang, but they’ve discovered he’s betrayed them and plan to hang him at sunup. He’s lashed to a tree and guarded by his enemy, the brutal Big Judson. But Rose Lanier, who has drifted along with the gang, is going to help O’Malley escape. The cutting will show us exactly how she does it, and why.

Rose interposes herself between Big and O’Malley, chatting up the thug. A cut of about 180 degrees takes us to the opposite side of the tree and shows her slipping a knife toward O’Malley’s hand. We’re so familiar with this sort of insert that we’re likely to forget that once it was fresh.

O’Malley starts, then shifts his gaze toward Big.

Then comes a simple, remarkable shot. Rose slips the knife to O’Malley. Then she pats his hand. Then she gives it a squeeze.

Mystery and charm of the American cinema, as Godard would say: a single cut-in of hands can give us a lot. First there’s the narrative information (I’m passing you the knife), then Rose’s expression of support (Good luck!), capped by a burst of affection (I love you). The whole thing takes less time than I’ve used to tell it. Surely this ability to invest plot-driven detail shots with heartfelt emotion helped American cinema conquer the world. I’m tempted to say that we could sum up of the power of Hollywood, in its laconic prime, with that formula: the pass, the pat, the squeeze.

This shot is as compact in its expression as the previous one. It’s impossible to capture here all the emotions that flit across O’Malley’s face: hope of eluding death, realization that Rose loves him, anxiety that surviving will make him choose between love and duty. Rose’s brother is the killer he’s been tracking, and in a perversely honorable way O’Malley had looked forward to being hanged. That would have spared him arresting the boy. Now he must live, enforce the law, and lose the woman who has saved him.

I saw some European films that absorbed such continuity tactics quite deeply. Above all, Mauritz Stiller’s Song of the Scarlet Flower (Sangen om den Eldroda Blomman, 1919) and Johan (1921) relied heavily on analytical editing in the American fashion, including angled shot/ reverse shot. As in Fabiola, some of the discontinuous cuts have their own logic. I wish I had time to explore those Stiller films in more detail–particularly their use of turbulent rivers as dynamic plot elements, not mere landscapes. Maybe in some future entry….

Four-quadrant style

Before they adopted the analytical editing characteristic of American cinema, directors were still able to guide our attention. The so-called “tableau” style, about which I’ve waxed enthusiastic on this site before, became a rich tradition in the 1910s. Editing within the scene is minimized. (Apparently most European directors didn’t consider it a creative option in its own right until later in the decade.) The drama is carried by performance and ensemble staging. Relying on movement, acting, and composition, the director controls where we look and when we look at it

To take a straightforward example, consider the rather ordinary melodrama Le Calvaire de Mignon (Mignon’s Calvary, 1917). The scheming and dissolute Dénis de Kerouan wants to wreak misery on his brother Robert. While Robert is out of the country, Dénis hires a forger to fabricate a letter indicating that Robert has a mistress. Dénis leaves the letter on the desk for Robert’s wife to find.

Dénis has exited through the central entryway, and into the empty study comes Robert’s wife. She discovers the letter.

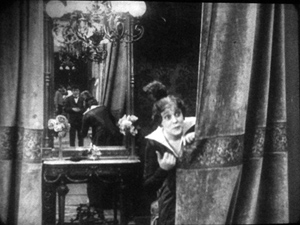

She moves to the left foreground and starts examining it. At this point Dénis’ face peeps out from behind the central curtain. The director makes it easy for us to notice him because nothing else is happening in the set, and Denis’ face is rather close to the wife’s. It’s almost as if he’s looking over her shoulder.

Once we register Dénis’ presence, the director can proceed to balance the shot. All that empty real estate on the right of the frame asks to be filled, and that’s what happens.

When the wife reads the damning letter, she collapses rightward into the chair, just as Dénis rushes forward to take charge of the situation.

This move exemplifies the staging technique known as the Cross, which motivates the switching of characters’ positions in the frame.

Simple as it is, this portion of the prologue of Le Calvaire de Mignon shows how, without cutting, a director can steer us to one or another zone of the shot through such cues as faces, centering, proximity to points of emphasis, and movement. Something similar happens in one, more striking moment of another fairly unexceptional movie from the period.

Nobody will claim Der Stoltz der Firma (The Boss of the Firm, 1914) is a masterpiece, or its director Carl Wilhelm is a master. It’s one of the many comedies in which Ernst Lubitsch starred before becoming a director. Here he’s Siegismund, a bumbling young provincial with more aspirations than abilities, who simply lucks into marrying the boss’s daughter. On the way to the happy ending, he wins the patronage of a fashion designer, Lilly, whose husband finds her flirtation with the young parvenu none too innocent.

Wilhelm’s use of the tableau approach isn’t especially dynamic in most of the film, but there’s one flashy scene. Wilhelm gets us to watch a very small, tight area of the frame and then gently swings our attention to a wider swath of action. As usual, everything depends on a sort of task-commitment on our part: Watch what’s likely to forward or enrich the ongoing narrative.

Lilly lures Siegismund into a changing room, with the composition showing him reflected in a mirror behind her. This sets up an item of setting that will be central to the scene.

Once inside, he coyly presents her with a flower and they draw close together. Since we tend to concentrate on faces, the small area encompassing their two profiles is likely to draw our attention. Nonetheless, the shot is notably unbalanced, as if anticipating something coming in from the right side.

Abruptly Siegismund and Lilly draw apart, and the space between them, in the mirror, is filled by the face of Lilly’s husband, coming through the curtain.

I’d bet that a Tim Smith experiment would find that nearly every spectator is already watching this small zone in the upper left quadrant of the shot. Faces, especially frontally positioned ones, command our notice, and thanks to the mirror we here have three of them. Moreover, movement is an attention-getter too, and all three faces are in motion. Mr. Maas’s face, in fact, gets notably bigger and clearer. His wrathful expression is another reason to watch him.

The husband’s body enters to fill the frame, then presses into the center of the shot, blotting out Lilly as he faces down Siegismund.

Now the director controls the speed of our gaze quite precisely. Maas slowly rotates, forcing Siegismund to swing from left to right, as if he were attached to the bigger man by a rod. This yields, again, that nice sense of refreshing the frame that we always get from a Cross.

Siegismund collapses into the lower right of the frame, flinching from the fight that’s about to start. Lilly soon shoves aside her husband’s chastisement and melodramatically tells him to leave. “We’re divorcing!” the following intertitle says.

Mr. Maas takes it in stride, shrugging and spreading his arms. He leaves, and thanks to the helpful mirror we can see him chortling as he glances back and passes through the curtain.

If we hadn’t already noticed Siegismund cowering behind Lilly in the lower right quadrant, we will now. Lilly angrily flounces to our left (the Cross again). Siegismund rises to explain he hadn’t meant to cause a rift in the marriage.

We’re back to something like the initial setup, but now with Siegismund centered, the couple further apart, and a less unbalanced frame. The drama, which now consists of Lilly inviting him to tea tomorrow, can proceed from here.

A different way of seeing?

Tom Tom the Piper’s Son (1905).

We’ve become used to editing-driven storytelling, and I’m convinced that we can learn to notice the staging niceties of the tableau alternative. But what if early filmmakers explored some other ways of looking that are far more unfamiliar to us today?

Noël Burch, in his 1990 book Life to Those Shadows, argued that in the first dozen years or so of cinema, movies solicited viewing skills that we lack today. He suggested that early filmmakers often refused to center figures and crammed their frames with so much activity that to our eyes the shots look confused and disorganized. In Tom, Tom, the Piper’s Son (1905), Burch notes, the bustle of the fair, the reliance on an extreme long shot, and the absence of any cutting make the central event, Tom’s swiping of the pig, difficult to catch. In the frame surmounting this section, Tom is making off with the pig in an area just right of center, but the antics of the clown and the response of the crowd may well distract us from the main action.

The result, says Burch, is a mode of filmmaking that demanded

a topographical reading by the spectator, a reading that could gather signs from all corners of the screen in their quasi-simultaneity, often without very clear or distinctive indices immediately appearing to hierarchise them, to bring to the fore “what counts,” to relegate to the background “what doesn’t count” (p. 154).

Later developments linearized this field of competing attractions, creating a smooth narrative flow “harnessing the spectator’s eye.” Among these developments were the presence of a lecturer at many screenings (telling people what to watch) and, of course, the growth of the continuity editing system. But Burch suggests that the “primitive mode” hung on until about 1914.

A famous example is a shot from Griffith’s Musketeers of Pig Alley (1912). The gangster has lured the Little Lady (Lillian Gish) into a back room and distracts her with a photograph while he tries to dope her drink, in a precursor of date-rape drugging. But the Snapper Kid, another gangster, has been keeping an eye on her and follows. As the gangster starts to pour the drug out, the Kid’s entry is presaged by a whiff of cigarette smoke.

At the crucial moment, we have three things to notice: the Little Lady’s obliviousness, the gangster’s pouring the drug, and the full entrance of the Snapper Kid.

Today’s director would likely resort to editing that shows the doping, then the Kid arriving, then the doping again, and leaving us to infer a vague sense that they’re happening at the same time. Griffith’s choice gives us genuine simultaneity, but at a cost. Two cues compete for our attention: central composition for the drink, major motion on the edge for the Kid’s entry. In my experience, viewers tend to notice the appearance of the Kid, but to miss the business with the drink. (Another passage for Tim Smith to test!) By today’s standards, Griffith has failed as a director, but Burch’s view suggests that 1912 viewers, more sensitive to “all-over” composition, could have registered both actions, perhaps by rapidly scanning back and forth.

During my trip I found a fascinating example of this issue, as well as an apt counterexample. Both involve daggers.

In Maman Poupée (1919), a remarkable Italian film directed by Carmine Gallone, a devoted, somewhat infantile wife learns of her husband’s affair with a society woman. Susetta confronts the mistress and begs her to break off the affair. The woman laughs in her face. What happens next is given in several shots, mostly through axial cuts.

The linear editing, as Burch indicates, lays everything out for us step by step. The close-ups accentuate what is important at each moment: Susetta seizing the dagger, stabbing her rival, and–in a remarkably modern-looking extreme close-up–registering her horror at what she has done.

Two years before, Marcel Simon, the (Belgian!) director of Calvaire de Mignon, handled a similar situation rather differently. The diabolical Dénis, whom we met earlier, has succeeded in destroying his brother’s life. It remains only for him to force Robert’s niece Mignon to marry the Algerian Emir Kalid. Kalid is at first humble, beseeching Mignon to become his bride, but then he gets rough. We might note already that Mignon, while fairly near the camera, hovers close to the left frame edge.

In their tussle, Mignon snatches something from Kalid’s waistband and flings him far away to the right.

What’s up? Mignon has grabbed the Emir’s dagger and stands poised with it pressed to her heart. But we haven’t been able to see that dagger very clearly (no cut-in close-up here, as in Maman Poupée) and she’s returned to her position far off-center. It’s likely that a viewer today wouldn’t understand that she’s holding the men at bay by threatening suicide. Would a 1917 viewer be as uncertain? Would the situation, plus her posture and the men’s hesitation, be enough to get the point across?

Moreover, this moment goes by very quickly. Scarcely has Mignon struck her pose when her true love, René, bursts in behind her–frontal, fairly centered, and moving fast. Meanwhile, Dénis is sneaking up on her, hugging the left frame. Mignon makes a break for René, dropping the still almost indiscernible dagger.

While Mignon and Rene embrace in the right rear doorway, blocked from our view by Kalid, Dénis stoops over. It’s a timely adjustment, giving us full view of the benevolent Le Maire sweeping into the room.

As the two men confront one another–the climax of the scene–director Simon has the effrontery to let Dénis steal the show. He picks up the dagger, which now can be seen more or less plainly, weighs it in his hand, and looks out for a brief, pondering moment.

We seem to have a late example of the Snapper Kid Effect, in which important actions compete for our attention. Is it clumsy direction to perch Mignon on the frame edge as René rushes in, and to let Dénis recover the dagger while we’re supposed to concentrate on the face-off between the two powerful men? Or would audiences have tracked all the strands of action and enjoyed their simultaneity?

On this site and elsewhere, I’ve assumed that directors in the 1910s structured their compositions for what Charles Barr calls “gradation of emphasis,” a fluid pattern of primary and secondary points of attention. I’ve argued as well that Burch exaggerates the decentered, nonlinear compositions of even the earliest years. Many of the films staged by Lumière cameramen are designed cogently, and so are many films from the 1900s. (Tom, Tom might be the exception rather than the norm.) Yet every so often, you get a later case, like Musketeers of Pig Alley or Le Calvaire de Mignon, that suggests that some viewers might have been more adept at tracking simultaneous events than we are.

A still broader question remains. Let’s assume that people were able to follow and enjoy films in the tableau style, even when that style pushed toward illegibility. What enabled people to adapt, and so quickly, to continuity-based movies? Some scholars and filmmakers argue that continuity editing achieved its power and worldwide acceptance because it mimics our natural mode of perception. At any moment, we’re concentrating on just a small portion of our surroundings, and this is like what editing does for us in a scene. On the other side, Burch and others would argue that continuity filmmaking is only one style among others, with no special purchase on our normal proclivities. On this view, classical continuity’s apparent naturalness hides all the artifice that goes into it, and this concealment makes its work somewhat insidious. I’ve offered some thoughts on this problem elsewhere, but I bet I tackle it again on this site some time.

In any case, we need to study films that seem odd or difficult, whether they’re recent or from the distant past. We’re guaranteed to find some striking and unpredictable things that provoke us into thinking. That’s one of the pleasures of exploring the history of film as an art.

For earlier studies of the tableau style on this site, see this entry on Bauer, this one on 1913 films, this one on Feuillade, and this one on Danish classics. This entry discusses the emergence of Hollywood-style continuity, and this one explores the exemplary editing in William S. Hart films. I go into more detail in two books, On the History of Film Style (chapters four and six) and Figures Traced in Light (chapter two) and in the essay, “Convention, Construction, and Cinematic Vision” in Poetics of Cinema. The last-named piece tries to stake out a middle position on the “naturalness” of continuity editing. Kristin has analyzed Alberto Capellani’s films as instances of the tableau trend, last year here and just last week here. She also weighs in on the debate about whether viewers of his time were better prepared to grasp the action than we are. More generally, Capellani’s career exemplifies the major and swift stylistic changes of the 1910s. When he went to America, he became pretty adept at the emerging continuity style, as the Nazimova vehicle The Red Lantern (1919) indicates. Of course that’s got some striking single images too.

The Red Lantern (1919).

If it’s Tuesday, this must be Belgium, if it’s July

The entrance to the Brussels Cinematek screening rooms. No cellphones, no drinks, and above all no frites.

DB here:

As every year, I’m spending time in Brussels doing research at the Royal Film Archive, and as usual every two years, I’m preparing to go to the Flemish Film Foundation’s Summer Film College, this time in Antwerp. My stay was timed, also as usual, to the Cinédécouvertes festival sponsored by the Cinematek.

Cinédécouvertes is a partly a festival of festivals, gathering most of its titles from Venice, Rotterdam, Berlin, and Cannes. It’s a good way for me to catch up with several top-flight films unlikely to come to the US, or at least any time soon. (See the links at the bottom of this entry for my earlier observations.) In screening only films that have not been bought for Belgian distribution, Cinédécouvertes’ record shows a keen talent-spotter’s eye. Just in the last ten years, its winners have included Japón, Oasis, Shara, Tropical Malady, Day Night Day Night, How I Ended This Summer, and Police, Adjective. The year 2000 was remarkable, with prizes given to four films: Miike’s Audition, Im’s Chunhyang, Kurosawa’s Barren Illusion, and Tarr’s Werckmeister Harmonies. My affection for this modest but robust festival goes back to the 1980s; it introduced me to films by Hou, Kitano, and Kiarostami when they were genuine cine-discoveries.

This year Bruno Dumont’s Hors Satan took the L’Age d’or prize, the one reserved for films that seek to disturb us in the vein of Buñuel’s classic. That prize consists of 5000 euros given to the filmmaker. The two other awards aim to support local distribution of the best work. The Austrian entry Atmen (Breathing) by Karl Markovics and Alejandro Landes’ Porfirio, set in Colombia, won the prizes. If either is picked up for Belgian release, the distributor will receive 10,000 euros to help cover costs. Shouldn’t other festivals imitate this strategy for getting films onto screens?

My lecture preparations for Antwerp kept me away from many festival offerings, but I did see two of the prizewinners. Atmen and Hors Satan reminded me that a lot of European art films, despite their reputation for being slow, have a crisp, laconic style. Abrupt cuts open and end scenes, while an unexpected close-up can accentuate a moment. This sort of precision meshes with other conventions of this tradition: delayed exposition, long scenes without dialogue or music, routines that structure the plot, and a demand that we let things unfold at a rhythm different from that of the goal-driven Hollywood cinema. Early on, the scruffy idler of Hors Satan shoots down a man while the vaguely punkish girl with him doesn’t bat an eye. What registers is the bare, brute act, no more and no less.

Eventually we’ll learn some causes and reasons, but in this mode of cinema, a gesture is given heft by coming out of nowhere, without benefit of much preparation. What we can count on is the repetition of a routine, such as the man’s praying or his receiving a piece of bread each day from an (initially) unseen donor. Sooner or later, something will emerge–a pattern of activity, if not a straightforward plot.

Similarly, we know almost nothing about the young man who gets dressed at the start of Atmen. Only gradually will his routines reveal his work-release from a juvenile prison and his growing awareness of his responsibility for the crime that put him there. In this unvarnished tale, which sends young Vogler to work assisting a mortician, we get nothing like the mixture of humor and poignancy we find in Takita’s Departures. Everything here is cool, even curt, with each shot providing a bit of action that we have to fit into the personality lurking behind Vogler’s guardedly blank expression.

That personality becomes clear, in a rather conventional way, when Vogler sets out to find the mother who abandoned him. Things are much more opaque in Hors Satan, in which miracles and near-miracles are performed with a grimy physicality suited to provincial life lived among marshes and rocky hillsides. If Atmen pulls into focus as a fairly clear-cut psychological drama, Dumont’s film tries for something grander and less committed to personality. It seems to me to aim for a sense of flinty, rough-hewn holiness that is beyond conventional piety. In The Tree of Life, faith bathes the lovely faithful in a glow–hell, it can make them levitate–but here faith, if that’s what’s involved, is irredeemably coarse, even ugly. (Hors Satan reminded Cinédécouvertes judge Charles Tatum of Abel Ferrara.) Like Atmen, though, Hors Satan gets to its destination through a storytelling technique that we can trace back to neorealism and its respect for dawdling exposition and the undramatic singular detail. Some cinematic traditions are endlessly fertile.

Earnest Goes to Summer Movie Camp

The Last of the Mohicans (1920).

This year’s July film college is woven of three strands. One is called “Masterpieces in Context,” and it includes films by De Sica, Ford, Flaherty, and others. The primary strand is devoted to film and the visual arts, and given my interests it looks exciting. Steven Jacobs will present lectures related to his new book, Framing Pictures, to be published during our event. Steven will survey a range of relationships between cinema and painting, including films about artists (e.g., Caravaggio) and scenes set in museums. Wouter Hessels, the incoming Director of the Cinematek, will discuss work by André Delvaux and other Belgian filmmakers. Lisa Colpaert will talk on “Noir Portraits.” And Tom Paulus will survey instances of the influence of painting and photography on directors’ visual style, ranging from Tourneur to Tarkovsky. Films include The Last of the Mohicans (1920), Spirit of the Beehive (1973), and Arsenal (1929). I’ll throw in my $.02 with a lecture called “Seeking and Seeing: Lessons from E. H. Gombrich,” which hopes to show how Gombrich’s approach to art history can help us study film history.

My main contribution, though, is to a third strand called “Dark Passages: Storytelling in 1940s Hollywood.” Through screenings of Suspicion (1941), Daisy Kenyon (1947), Laura (1944), A Letter to Three Wives (1948), and six other movies, I’ll survey some narrative innovations of this remarkable era. Our main attractions are A pictures, but I’ve pulled some clips and stills from B’s, which are no less intriguing in their flashbacks, dreams, hallucinations, splits in point-of-view, and treatments of mystery and suspense.

I’m still working on the talks, but what’s emerging is one unorthodox premise. As an experiment in counterfactual history, let’s pretend that World War II hadn’t happened. Would the storytelling choices (as opposed to the subjects, themes, and iconography) be that much different?In other words, if Pearl Harbor hadn’t been attacked, would we not have Double Indemnity (1944) or The Strange Affair of Uncle Harry (1945)? Only after playing with this outrageous possibility do I find that, as often happens, Sarris got there first: “The most interesting films of the forties were completely unrelated to the War and the Peace that followed.” Sheer overstatement, but back-pedal a little, and I think you find something intriguing.

Some lectures are in English, some in Dutch. All screenings are 35mm, with live accompaniment for the silent films. There will also be an excursion to Antwerp’s gorgeous, widely praised new museum, the MAS. It’s open until 11 on weeknights and until midnight on weekends, an admirable idea. I’ll be sure to take photos of the skull-mosaic terrace.

More on the summer film school after I’ve done it. In the meantime, coming up blog-wise: ideas about how people might have watched movies a hundred or so years ago.

I first explained my research in the film archive here. For previous years’ notes on the Cinematek’s annual festival, you can go to the category here. On the Cinephile Summer Camp, here is the report on the 2007 gathering and here’s the one on 2009. Sarris’ scandalous claim (yes, I too thought about The Best Years of Our Lives, They Were Expendable, Ministry of Fear, etc. etc.) is in the introductory essay, “Toward a Theory of Film History,” in his classic book The American Cinema (New York: Dutton, 1968), 25.

I especially believe the “with all present” part. This is apparently the table to get at Au Vieux St. Martin, Brussels. In reflection is Nicola Mazzanti of the Royal Film Archive.

Capellani trionfante

Quatre-vingt-treize (1914)

Kristin here:

The early films of Albert Capellani are probably the most significant of all the discoveries of the Hundred Years Ago series.

Mariann Lewinsky

During the recent Il Cinema Ritrovato, I was somewhat surprised at the relatively small audiences for the programs that included films by Albert Capellani. Those films formed the second half of a large Capellani retrospective that began during the 2010 festival. Last year’s program was a revelation to me, and this year’s only confirmed my sense that here is a truly major discovery from the period before World War I. No doubt the addition of a fourth venue and the appeal of the Boris Barnet and early Howard Hawks retrospectives drew some attendees away.

As I wrote in my first Capellani entry, his significance has only slowly become apparent over several of the festivals. Initially his films were few and scattered through the annual “Cento Anni Fa” seasons of movies made one hundred years earlier. (The first “Cento Anni Fa” program in 2003 was curated by Tom Gunning; those since have been curated by Mariann Lewinsky.)

My first entry was handicapped by the fact that almost none of the films was available on DVD, and few of them had ever been accessible for researchers to view in archives–Germinal being the main exception. For illustrations, I mostly resorted to online versions of a few of the films, mediocre in visual quality and covered with bugs and time read-outs. The situation has changed enormously in the intervening year. Many more films have been restored; many of the archival notes at the beginning of this year’s prints were dated 2011. Moreover, in May Pathé brought out the Coffret Albert Capellani, a four-disc set with seven of the best-preserved films of 1906, as well as L’Assomoir and three major features from 1913 and 1914. Filling in the gaps to a considerable extent is the Albert Capellani: Un Cinema di Grandeur disc, from the Cineteca di Bologna, released just in time for the festival; it contains twelve films from 1905 to 1911. Between them these releases contain 23 films, plus some fragments. (The contents are more extensive than it might appear, since the three features alone add up to about seven hours.) Booklets accompanying the DVDs provide much up-to-date information on Capellani. It’s hard to think of an early filmmaker whose work has gone from such scarcity to such abundance in a single year. Once again, a driving force behind this dramatic improvement has been Mariann, working with La Fondation Jerôme-Seydoux-Pathé and the archives that provided print material.

I have taken advantage of this new availability to return to my earlier entry and add illustrations to descriptions of such important films as L’Arlésienne and L’Épouvante, which I could only summarize verbally when I first wrote it. This entry takes up where that one left off, with comments on several of the newly revealed films, or in one case, a new version.

For a list of all the Capellani films so far shown at Bologna and their availability on DVD, see the end of this entry.

An artist of the 19th Century meets a new art form

Those festival guests who missed the Capellani films missed, in my opinion, the rewriting of early film history. He is not simply another important silent filmmaker to be placed in the pantheon. Film by film, this year and last, I kept comparing what I was watching with what D. W. Griffith had made that same year. In each case, Capellani’s film seemed more sophisticated, more engaging, and more polished. Overall Capellani may not have been a better director than Griffith, but for the period of the French films, I believe it would not be exaggerating to say that he was: L’Arlésienne (1908) compared with anything Griffith did that year or L’Assomoir (1909) versus The Lonely Villa or even The Country Doctor. Capellani’s L’Épouvante (1911) was shown again this year; I had to shake my head in amazement that it was made the same year as another woman-in-danger film, The Lonedale Operator. Nothing in Griffith’s pre-war career comes close to Les Misérables or Germinal.

Both Griffith and Capellani came from the theatre, though the French director had already had a much more successful career there than had the American. Both had a strong bent toward melodrama and historical epics. But their styles developed along different lines. Undoubtedly Griffith’s pioneering work in editing sets him apart; Capellani never ventured far in that area. Capellani’s strengths were in the tableau style, with lengthy takes and intricately staged action. (For David’s thoughts on the tableau style, see here and here.) Rather, his strengths were in his elaborate staging of scenes, whether with one actor or a crowd. Perhaps because of his theatrical success, from early on Pathé must have given him generous budgets, for his settings are more opulent than Griffith’s, and he frequently went on location to the spectacular and picturesque landscapes and buildings of France. For example, he could simply take his team into old streets in Paris and create a more realistic impression of the city in the French Revolutionary era than Griffith could manage with the sets of Orphans of the Storm eight years later. (See left, Le Chevalier de Maison-Rouge, 1914; note how close Capellani places the camera to the wall at the left, exaggerating at once the sense of depth and of narrowness.)

There is no doubt that in the long run, Griffith’s editing-based approach won out and helped establish the norms that remain with us to this day. It has been all too easy to trace the history of cinema as, at least implicitly, a history of innovations in editing. The great directors were those who fit into that specific history. Although Griffith never entirely mastered the classical Hollywood style the way Allan Dwan or Rex Ingram or Maurice Tourneur did, the continuity editing system undoubtedly grew in part out of techniques he popularized. In an historiographic approach based on editing, those who did not contribute to its development are likely to be passed over. Capellani uses every technique but editing with great artistry, and hence his films may be easy to dismiss as theatrical or old-fashioned. Moreover, many of them are based on 19th-Century classics, especially by Zola and Dumas, even when they deal with an older period, notably the French Revolution in his last two surviving French features, Le Chevalier de Maison-Rouge and Quatre-Vingt-Treize.

Yes, as Mariann wrote in last year’s catalogue, “Capellani’s profile made him the target of a film historical trend–now long discredited–which criticised ‘the theatrical’ and promoted ‘the filmic.’ This is perhaps why he was so underestimated.” I am not sure that the contrast between theatrical and filmic cinema has entirely disappeared even today, but if we assume that all film techniques are equal, we can better appreciate Capellani in the context of his era.

I admit that, to a film historian or buff who learned early cinema from seeing Griffith and Chaplin and perhaps Hart and Feuillade, Capellani’s films may at first take some getting used to before their virtues become apparent. A feeling for Victorian narrative art, both written and visual, would help. At first, the acting might seem histrionic, and there are probably few, if any other directors’ films that so well preserve the stage conventions of the previous century. But for the most part, the acting in Capellani’s films is quite brilliant. The lack of editing might be a hurdle for some. Capellani also entirely avoided dialogue titles, and the expository titles are few. Characters are constantly writing and reading letters, which substitute for intertitles. It’s a convention one must simply accept, and it forces the viewer to concentrate fiercely on the actors’ faces and gestures, which carry the narrative information. For me, all this simply adds up to gripping filmmaking.

Take L’Assomoir, the earliest undeniable masterpiece from among the films so far shown at Bologna (though L’Homme aux gants blancs and L’Arlésienne come close). It is full of lengthy takes with intricate choreography. In all his films, Capellani clearly gave precise movements and business to each actor present, no matter how insignificant, and their faces, stances, and gestures, often fairly broad, make up for the almost entire lack of cut-ins. Take the scene where Gervaise and her new fiancé Copeau celebrate their engagement in an open-air café, with the proceedings interrupted at intervals by Gervaise’s former lover Lantier and the vengeful Virginie, with whom Lantier has taken up. The scene is done in a single two-minute shot, with the fluid action moving forward and back, in and out.

The ten frames below show phases of the action:

(1) Lantier in the foreground and Virginie in the middle ground watch the engagement party guests arrive. (2) Virginie speaks to Gervaise as Copeau comes forward.

(3) The guests begin to dance, with an organ-grinder coming in from the right. (4) The dancers move out left, and Copeau and Virginie begin to dance.

(5) They move out left with the organ-grinder, leaving Gervaise alone. (6) A comic friend who is continually eating comes back in to speak to Gervaise and then leaves.

(7) Lantier comes in from the right and starts bullying Gervaise. (8) Another friend comes in and drives him away out right.

(9) The dancers and organ-grinder return, with Virginie still dancing with Copeau. (10) The scene ends as Gervaise sits disconsolately while Virginie moves to Lantier and the pair watch Gervaise menacingly from the extreme right edge of the frame.

Similarly complex scenes, notably a celebration of Gervaise’s birthday, follow, culminating in a final shot that runs 6:45 minutes, out of a 35:46 minute film! (There is a pair of titles in Flemish and French that interrupt the shot early on, but the take was clearly continuous, and the titles seem likely to have been added by the exhibitor in whose collection the sole known surviving print was discovered.)

As Mariann also points out, one can find “filmic” elements in Capellani, including “the sheer photographic beauty of exterior shots, which is not to be found in the work of any of his contemporaries.” The frame at the top of this entry, made in 1914, is striking enough. (Mont St. Michel appears only in this fashion, as a tiny shape in the backgrounds of a few shots to establish that the characters have landed on the Normandy coast, but otherwise does not figure in the film.) But I suspect few would guess that the shot illustrated at the bottom was made as early as 1906.

The temptation is to go on and on about Germinal and make a long entry even longer. But Germinal has been the most familiar of Capellani’s films, and I mentioned some writings on it in my first entry. I’ll just make a few remarks about it here.

First, Capellani does a remarkably good job of capturing the naturalism of the Zola novel, as the first frame below suggests. Second, the scenes in the mine convincingly convey a sense of cramped working spaces, despite the need to shoot on sets (second frame below).

The film also makes highly effective use of the giant slag heaps behind the coal fields, placing them in the backgrounds of shots in various locales:

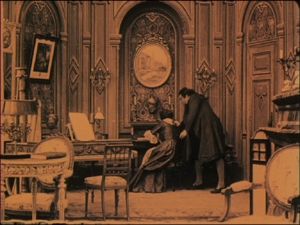

Clearly the resemblance of these neatly squared-off heaps to pyramids did not escape Capellani. (Compare the Red Pyramid at Dashur, above.) I think he intended this to be noticed and to be part of a motif linked to the decor of the mine owner’s study:

Like many rich men in the movies of this era, the owner is characterized as a collector of antiquities and of modern statuary with ancient motifs. (One film shown this year, I forget which, showed a rich man buying such pieces.) A case in the hallway beyond the study presumably houses his real ancient pieces, while his desk sports a small modern statue of a samurai, and the mantelpiece holds a modern Egyptianizing bust of a woman. Capellani was probably intentionally comparing the mine owner to a pharaoh and his workers to the “slaves” who built the pyramids. (This was the view of the time, though the pyramids were in fact built with paid labor.) Such a conceptual use of motifs again marks the sophistication Capellani’s films had reached by the “anna mirabilis” of 1913.

A major step forward since last year is the fact that we now have a reasonably complete print of L’Homme aux gants blancs. As it demonstrates, Capellani can cut in on those rare occasions when it’s necessary (first frame below). Here we need to see the detail of the seamstress fixing a loose button on the new gloves, not just for its own sake but because those gloves will later be lost, found by a thief, and deliberately dropped beside the body of a woman whom the thief kills. The seamstress’ identification of the repaired glove leads to the arrest of the wrong man. In the final shot (second below), the devil-may-care thief, witnessing the arrest, enjoys the irony by holding the door open for a police inspector and handing him his dropped cane. The ending is grim, since the paddy-wagon departs, leaving us to assume that the wrong man will be punished.

I can’t mention all the films shown this year, but two I particularly enjoyed were La Bohème (1911) and Le Signalement (1912), neither of which I can illustrate.

Firstly, this year Capellani’s brother Paul, whom we have seen in smaller roles in previous years, emerged as a fine actor, with perhaps his best work being as Rodolphe in La Bohème. (He played the same role opposite Alice Brady in Capellani’s American feature based on the same story, La Vie de Bohème, in 1916; there the more restrained acting style favored in the U.S. by that point makes his performance less dynamic and affecting.) The familiar tale is compressed but movingly told.

Le Signalement (“The Description”) in some ways echoes the remarkable dramatic twist of the previous year’s L’Épouvante. There a burglar ends by gaining our sympathy, and the suspense during the later part of the film centers not around the frightened heroine but around whether the terrified man will fall to his death. The heroine’s compassion makes for a moving resolution. In Le Signalement, Capellani raises the stakes. A shoemaker and his daughter (granddaughter?) Jeanette, played by the excellent child actor Maria Fromet, live in a French village. The police circulate a flyer describing a child murderer who has escaped from a nearby insane asylum. While delivering some boots, the cobbler is lured to linger in a tavern, and the murderer comes to the house. In characteristic fashion, Capellani lets most of the length of the killer’s time in the house play out in a single take into depth; the camera faces diagonally across the room toward the open door, the only place where help might appear.

When the escapee arrives, Jeannette innocently invites him in and offers him some food, including a dangerous-looking knife to cut a piece of pie. Tempted to kill and yet overwhelmed by the child’s kindness, the man sits and eats. Capellani ups the ante when Jeannette lifts a crying baby, whose presence we had not previously noticed, out of a basket to comfort it, even handing it to the man to rock. During all this we are left in suspense as to whether he will give in to his murderous obsession or resist it. At last the pair hear the police outside, and Jeannette realizes that her visitor is the killer–yet she helps him to escape out the window. Again we are torn, not wanting the child’s generous gesture to be thwarted and yet not wanting a child murderer to run loose! The plot solves the dilemma in a neat and dramatic fashion. Overall, like L’Homme aux gants blanc and L’Épouvante, Le Signalement packs conflicting emotions into a single reel.

Such density of narration is one characteristic of Capellani’s work. As Mariann wrote in the program last year: “Capellani’s speciality as a director is the broad scope of his narratives, connecting different locations and characters, which invests even short films with grandeur and space, to such an extent that the film lengths, given in either metres or minutes, often seem unbelievable. What? Can L’Épouvante really only be 11 minutes long? And Pauvre mère and Mortelle Idylle only 6 minutes each?”

Two final French features

Apparently Capellani made eight films in 1914, but as far as I know, only two survive. Both happen to deal with the French Revolution, and both are based on 19th-Century novels: Le Chevalier de Maison-Rouge (Dumas) and Quatre-Vingt-Treize (Hugo).

Last year I suggested that Le Chevalier might be a bit of a let-down after the heights of Les Misérables and Germinal. But it would be hard to match Germinal, and I have to admit that upon seeing Le Chevalier again on DVD, it kind of grew on me. The main problem, I think, is that Capellani doesn’t take much trouble to give the characters traits and make them sympathetic. They seem more like game pieces in service to the plot. But as always the staging and acting are marvelous, and both locations and sets, as I suggested above, give a vivid sense of revolutionary Paris.

Oddly, though, for the first time there are signs that Capellani is being influenced by cinematic trends of the day and is trying to expand his style in a somewhat tentative way. Clearly, like so many filmmakers, he has seen Cabiria and been impressed by its lumbering tracking shots. The tribunal near the end where the young lovers, Maurice and Geneviève, are condemned uses such a tracking movement well, pulling out from the lovers and the court to include the crowd that welcomes the death sentences:

In a few scenes Capellani also explores offscreen space in a way that I haven’t seen in his other films. Most dramatically, when Maurice sneaks up to the house where he hopes to see Geneviève, he appears small in the distance, disappears out the bottom of the high-angle framing, and suddenly reappears very close in the foreground, having somehow climbed up to a window:

In one scene Capellani even cuts in for a closer view and a different angle during a letter-writing scene. It’s a bit clumsy, with a mismatch on the man’s position–though not one that is worse than many attempted matches in European cinema of the 1910s:

The cut-in isn’t really necessary, though, and one would expect Capellani not to use it. This is one of the few moments in all the films shown where briefly Capellani seems truly old-fashioned, catching up with a technique that had already been in use for a few years. Here I wish he had stuck to his accustomed long shots, for it’s a sign of things to come. The next year Capellani would be working in the U.S. and making a smooth transition into continuity editing.

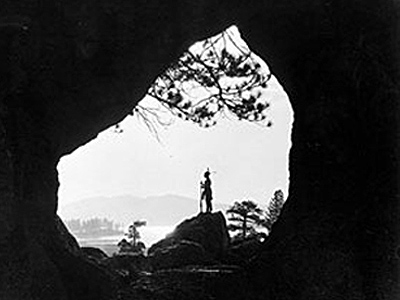

Capellani’s last film in France was Quatre-Vingt-Treize. With the outbreak of World War I, the subject matter, French fighting against French during the Revolution, was considered too provocative in a fervently patriotic context, and the film was banned. Capellani did not finish it but went immediately to the U.S. After the war, it was completed by his fellow theatre/film director André Antoine and finally released in 1921. There is no sign of any of the footage being by a different hand or done at a later time. It appears that Antoine simply edited the footage, perhaps to a script or shot list from the director, since the result on the screen is pure Capellani. It eschews the mild experiments of Le Chevalier and returns to a concentration on acting and a wonderful use of locations. At one point, in a single take, a troupe of Revolutionary soldiers marches past in a woodland setting. After they exit, there is a brief pause, and a man rises up from behind the foreground rocks in the path, signaling. Suddenly counter-revolutionary soldiers pop up all over the frame from the undergrowth and follow their foes stealthily in a seemingly unending stream:

In this film the characters are assigned more traits than in Le Chevalier, and the result, even at 165 minutes, is a rattling good tale.

(I mentioned that Capellani avoided dialogue intertitles. This films has some, but it may be that Antoine added those on his own.)

Despite dealing with the same historical period, the two films say nothing about Capellani’s politics, since in Quatre-Vingt-Treize the sympathies are clearly with the Revolutionaries, and in Le Chevalier, they lie with the group, including the title character, who are plotting to rescue Marie Antoinette from prison.

The American period

Given Capellani’s expertise in and long use of the tableau style of filmmaking, it is remarkable how easily he adapted to Hollywood. Only a few of his films from the early years in Hollywood survive, and His La Vie de Bohème (1916), a pleasant, well-made film, is not nearly as lively and absorbing as the French version, La Bohème (1912). I enjoyed the other features shown, Camille (1915, starring Clara Kimball Young) and The Virtuous Model (1919, starring Dolores Cassinelli), but I couldn’t help missing the French Capellani. It is hard to imagine how his career would have developed had he stayed in France. Perhaps, like Victor Sjöström and Ernst Lubitsch, he could have waited until after the war to move smoothly from the tableau style to adopt continuity editing. Perhaps, like them, he could have remained one of the top filmmakers of the silent period. (He returned from Hollywood to France after directing the 1922 Marion Davies vehicle The Young Diana. He did not direct again and died in 1931.) Good though the Hollywood features are, however, for me they inspire none of the sense of discovery and excitement that the films of the 1908 to 1914 period do.

Wishful thinking

By the 2011 festival, most of the known Capellani films have been restored. Some have improved before our eyes. In 2008 and again in 2010, the older restoration of L’homme aux gants blancs (1908) was shown. The newer, more complete restoration combines images derived from a 35mm print and a 28 mm one. A new restoration of Germinal with toning based on original color indications was shown this year.

There were also some fragments, which were saved for the seventh and final program in the series, “Borders and Blind Dates (A Workshop).” There is a version of Le Belle et la bête, for example, that is badly deteriorated, even within most of the footage retained by the restorers. What little remains suggests that the film must have been quite charming; the fragment is included among the extras on the Cineteca di Bologna DVD. There were also some films that were considered as possible Capellanis. According to the booklet accompanying the same DVD, Capellani is thought to have made anywhere from 70 to 80 films from 1905 to 1912. The number is uncertain, due to problems of attribution. Of these, about half survive, less than a third of them from the 1910-1912 period.

La loi du pardon, a 1906 melodrama of the type Capellani frequently made, is listed in the festival catalogue as “Ferdinand Zecca? Albert Capellani?” It could be Capellani, but to me most of his films of the 1906-07 years, though excellent, are not distinctive enough to be attributed to him without any documentation. Manon Lescaut (1912 or 1914; it is listed as both in the program on pages 128 and 129) was more tantalizing. An adaptation from a classic French novel, made by Pathe’s prestigious S.C.A.G.L. unit, would seem exactly Capellani’s sort of project. The first scene, set in an open-air café, seemed plausible as his work, but the rest of the film has little or nothing of his style about it. Instead there is a lack of long-held, intricately staged shots, one completely unnecessary cut-in, and too many old-fashioned painted sets. Compared to the location work in Germinal or just about any of the big films from the immediate pre-war years, these looked crude. Plus, as Caspar Tyberg pointed out to me, the action was staged more quickly than one would expect from Capellani, who often lets situations develop gradually, with many details in the gestures and facial expressions. There are some of his films in archives but apparently as yet unrestored. (According to the booklet accompanying the Coffret Albert Capellani, the Cinémathèque Française has a negative of a 1909 version of Manon Lescaut.) Otherwise I fear we must count on future discoveries in the archives for more Capellani films. Surely some will be forthcoming, now that archivists are aware of the importance of this newly revealed master. “Cento Anni Fa” will move on into 1912, 1913, and 1914, and perhaps the Capellani retrospective will resurface occasionally.

With the end of the main retrospective, however, it is safe to say that from now on anyone who claims to know early film history will need to be familiar with Capellani’s work. If you live outside Europe and don’t already have a multi-region DVD player, this might be the time to invest in one. It would be worth it just to see these new DVDs.

Capellani films shown at Bologna and their availability on DVD

Symbols used in the list:

* A film on the Coffret Albert Capellani, (La Cinémathèque Française, La Fondation Jérôme Seydoux-Pathé), Pathé, two four discs with booklet, Region 2 Pal. 36-page booklet in French. There is a bare-bones filmography, with titles and dates, on page 35, but this no doubt will be revised as research continues.

** A film on Albert Capellani: Un Cinema di Grandeur 1905-1911 (La Fondation Jérôme Seydoux-Pathé, the Cineteca Bologna) Il Cinema Ritrovato, 1 disc with booklet, Region 2 Pal. Intertitles in various languages; optional subtitles in Italian, French, and English. 55-page booklet in Italian, French, and English.

+ The titles I would most like to see on a future DVD!

In last year’s entry, I expressed the hope that some films from previous years could be repeated. Whether or not that hope influenced the programming, some were.

[Added July 19: Mariann tells me that she is now convinced that La Loi du pardon is genuinely a Capellani film. I find that quite plausible.]

2005

*Le Chemineau (1905)

2006

**La Fille du sonneur (1906)

2007

*Les Deux soeurs (1907)

*Le Pied de mouton (1907)

**Amour d’esclave (1907)

2008

Don Juan (1908)

La Vestale (1908)

*Mortelle idylle (1908)

Corso tragique (1908)

Samson (1908)

**L’Homme aux gants blancs (1908)

Marie Stuart (1908)

2009

*L’Assomoir (1909)

**La Mort du Duc d’Enghien (1909)

2010

Dans l’Hellade (1909)

**Le Pain des petits oiseaux (1911)

*La Fille du sonneur (1906) (Repeated from 2006)

Notre-Dame de Paris (1911)

+Les Miserables (1912)

**Le Chemineau (1905) (Repeated from 2005)

*La Femme du lutteur (1906)

**L’Arlésienne (1908)

Eternal amour (1914)

**L’homme au gants blancs (1908) (Repeated from 2008)

**L’Épouvante (1911)

*Pauvre mère (1906)

**L’Intrigante (1910-11)

La Mariée du château maudit (1910)

**Cendrillon ou la pantoufle merveilleuse (1907)

Samson (1908) (Repeated from 2008)

*Le Chevalier de Maison-Rouge (1914)

*Drame passionel (1906)

**Le Pied de mouton (1907) (Repeated from 2007)

**La Mort du Duc d’Enghien (1909) (Repeated from 2009)

La Fin de Robespierre (1912)

+La Glu (1913)

The Red Lantern (USA, 1919)

*Mortelle idylle (1906)

+L’Évade des Tuileries (1910)

2011

La Belle au bois dormant (1908)

Le Courrier de Lyon ou l’attaque de la malle poste (1911)

+La Bohème (1912)

La Vie de Bohème (USA, 1916)

*Quatre-vingt-treize (1914, released 1921)

**[Amour d’esclave (1907) Not shown for lack of time]

+Le Signalement (1912)

*L’Âge du Coeur (1906)

**Les Deux soeur (1907) (Repeated from 2007)

Camille (USA, 1915)

*Germinal (1913)

**L’Homme aux gants blancs (1908, more complete restoration)

Le Visiteur (1911)

Marie Stuart (1908) (Repeated from 2008)

Le Luthier de Crémone (1909)

The Feast of Life (USA, 1916)

**La Belle et la bête (1908, fragment) In “Extras” on DVD

Foulard magique (1908, fragment)

Béatrix Cenci (1909, incomplete)

**La Loi du pardon (1909) By Capellani or Ferdinand Zecca

La Legend de Polichinelle (1907)

[August 13, 2012: Roland-François Lack has recently added a post on Capellani on his website, The Cine-Tourist. He gives an extraordinarily detailed run-down of the Parisian (and Vincennes) locales used by Capellani (such as the one below), with many frames from the films and both current and vintage photos of the places, as well as a few maps and some engravings and other graphics. Well worth a look!]

La Fille du sonneur (1906)