Archive for the 'National cinemas: France' Category

More cinema Bolognese

Josette Andriot, decked out for Protéa.

Kristin here, with more from Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna:

When one thinks of female masters of disguise and action in the silent cinema, Musidora as Irma Vep in Feuillade’s Les Vampyrs probably springs first to mind. But for the historian, hovering always in the background was the legendary film by Victorin-Hippolyte Jasset, Protéa (1913), with Josette Andriot in the lead role. We knew the film mainly from a frequently reproduced image of the heroine in a black outfit, one of many she wears in the film.

Andriot was unconventionally beautiful, with dark hair and eyes and strong rather than delicate features. She was a genuine athlete, hired initially by Jasset for her riding ability, though he later exploited her acrobatic abilities in chases and scrambles around buildings.

Andriot was unconventionally beautiful, with dark hair and eyes and strong rather than delicate features. She was a genuine athlete, hired initially by Jasset for her riding ability, though he later exploited her acrobatic abilities in chases and scrambles around buildings.

Protéa has now been restored, though there is still missing footage. The heroine’s partner is Lucien Bataille, looking rather like a particularly devious James Cagney in the role of L’Anguille (“The Eel”), whose quick-change abilities and athleticism match hers. The thin, episodic plot revolves around a classic Macguffin, a treaty between two imaginary, vaguely Eastern European countries. The pair must acquire the document and hold onto it through one danger after another, outnumbered and chased all the while by a ruthless gang of spies for the other side.

I was startled by how modern the film seemed. Critics today tend to claim, inaccurately, that big action films throw some big thrill at the audience every few minutes. Protéa really does. The underlying purpose of the plot is to have the two leads escape from one sticky situation and change disguises, only to land immediately in another sticky situation. It’s essentially a serial boiled down into a feature.

The term “cinema of attractions” was originally coined by Tom Gunning to describe very early films that depended on novelties rather than narratives. These days, many academics apply the phrase to almost any film, old or new, boasting a lot of action and big special effects. But I’m tempted to use it of Protéa anyway. Jasset usually doesn’t keep Protéa and L’Anguille in any one disguise or situation long enough to exploit the initial premise. One moment she’s pretending to be a man; next thing we know, she’s an elegant partygoer and L’Anguille is a servant. The basic problem is that whenever the characters get into trouble, they don’t rise to the occasion by exploiting their current roles more cleverly. They just flee and assume a new disguise to try again. As a result most of the individual episodes remain unmemorable.

One exception is a sustained sequence showing the couple as traveling animal trainers. At one point they crawl into the cage and play with a real lion, and they stay in these disguises long enough to actually use the big cats to fend off their pursuers. The final hectic chase, with Protéa on a bicycle fleeing toward a bridge set aflame by the villains, is the most impressive passage we can enjoy as sustained action. (I won’t reveal how it comes out, except to say that the climactic moment prefigures a modern action heroine driving a bus toward a gap in an unfinished freeway.)

Protéa is fun, in large part due to the talent of the two leads. It’s a pity that this was Jasset’s penultimate film. He died in hospital before it was released. (His last film, La Danseuse de Kali, also starring Andriot, was recently rediscovered by our friend Hiroshi Komatsu and was shown in this year’s festival.) Perhaps Jasset would have developed into one of the major directors of serials. Still, one can see why Feuillade, who knew how to build suspense by stretching out a scene’s action, became the French master of the form.

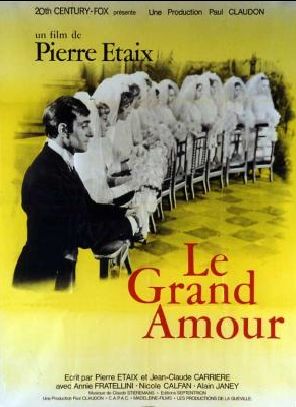

Etaix Refurbished

In an earlier entry, I mentioned that for some years French comic director and actor Pierre Etaix had not controlled the rights to his own films (two shorts and six fiction features). During that time, they were out of circulation and unavailable in any format. That situation has finally been rectified. Etaix has recovered the rights, and all the films have now been restored. They were re-premiered earlier this year at Cannes, and two were included in Il Cinema Ritrovato: the short Heureux anniversaire (1962) and the feature Le grand amour (1969).

Etaix’s early work in the cinema was during the 1950s as an assistant to Jacques Tati, and he is widely seen as having been greatly influenced by Tati. That’s true to some degree. In Le grand amour there are gags using sudden peculiar noises. Although the plot centers around the hero Pierre, his wife Florence, and his in-laws, there are nosy neighbors and waiters through whose eyes we are occasionally asked to view the action. When Pierre’s friend gives him instructions on how to behave on an upcoming date with his pretty secretary, bar patrons assume that they’re witnessing two gay men flirting.

Still, Etaix’s general approach is not particularly Tatian. He does not play a continuing character from film to film. In Le grand amour, as the young husband lured into managing his father-in-law’s factory, he dresses in conservative suits and casual wear; no Hush Puppies, striped socks, and too-short raincoat for him. Pierre succeeds in his dull job, unlike Hulot, who makes a mess of things when given a low-level job at his brother-in-law’s factory. The neighbors watch Pierre not because he is eccentric, but because they jump to wrong conclusions about his mundane behavior.

More importantly, though, Le grand amour creates a great deal of its humor with a technique that Tati would never use. He frequently shows hypothetical alternatives to the scene at hand. What if Pierre’s sophisticated friend were married to Florence? We see a scene played out with the friend in his place. There is a dream in which Pierre’s bed drives like a car along a country road, encountering other bed-cars and finally picking up the new secretary, hitchhiking by the road. When Pierre finally dares to take the secretary out to dinner, he launches into a nervous, boring monologue on business prospects, and we see him as she does, successively older and grayer with each reverse shot. When the gossipy neighbors pass along a story about Pierre, we see the successively exaggerated versions played out one by one, from the reality in which he merely tips his hat to a pretty woman he passes in a park through overt flirting to a passionate encounter behind a bush.

Le grand amour is not as funny as Tati’s films, but that probably results from an explicit melancholy that underlies this tale of disillusionment with marriage and final acceptance of the realities of life-long love. At times it reminded me more of the playful moments in Truffaut, especially in Shoot the Piano Player. Whether or not one wants to place Etaix in the New Wave, his play between reality and fantasy would seem to put him in the category of “ludic modernism” that Malcolm Turvey spoke about in his paper at the recent Society for the Cognitive Study of the Moving Image conference.

The restored print was beautiful, with the kinds of bright and pastel colors and high-key lighting that one seldom sees in the drab films of today. Presumably the new copies will show at other festivals and in art-houses with DVD releases to come.

Cinephiles’ corner

Bologna brings out a bevy of critics, historians, programmers, and unabashed film lovers of all stripes. Herewith, a sampling from DB.

Two critics for the ages: Kent Jones of Physical Evidence and the World Cinema Foundation, alongside Joe McBride, author of books on Ford, Capra, Welles, and Spielberg.

Dick Abel and Virginia Wright Wexman, both distinguished scholars, flank a copy of Dick’s book, French Cinema: The First Wave–presumably kept under glass like the rare specimen it is.

Curatorial cuddling: Haden Guest of the Harvard Film Archive, Adrienne Mancia retired from MoMA (and once a UW Badger).

The Cottafavi Cult invictus: Critics and programmers Barbara Wurm, Olaf Möller, and Christoph Uber, always in the front row.

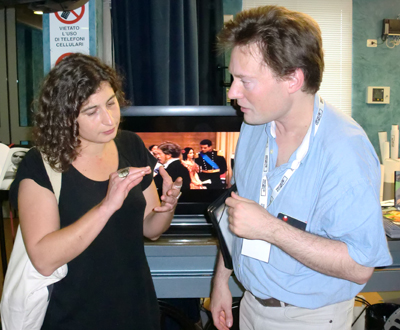

Camille Blot-Wellens, director of Film Collections at the Cinémathèque Française tells Danish historian Casper Tybjerg of her restoration of Albert Capellani’s Chevalier de Maison-Rouge (1914).

Two walking film encyclopedias sitting down: Kevin Brownlow, pioneer British historian, director, and collector, and Lee Tsiantis of Turner Classic Movies.

David Meeker, master of British cinema and jazz on the screen; Matthew Bernstein, author of Walter Wanger, a study of the Leo Frank lynching, and other studies of film history and culture.

Mariann Lewinsky, heroic programmer of the 1910 series and the Capellani retrospective, introduces Nikolaus Wostry, of Filmarchiv Austria.

More to come in at least one more Bologna-based entry!

Paris-Berlin-Brussels express

Doktor Satansohn.

Our trip to Europe has come to an end, and so we finish with a post scanning some highlights.

The magic lantern learns new tricks

DB here:

What am I seeing? Many avant-garde films pose this question. Mainstream fiction film and documentary cinema have mostly relied on the idea that the image should be recognizable as “what it is.” But one strain of experimental film has worked to delay or even prevent us from making out what’s in front of the camera.

Sometimes we lose our bearings only briefly, as when we eventually identify pot lids in Ballet Mécanique or bits of sunlit linoleum in Brakhage films. Sometimes language points out what’s really there. The titles of Joris Ivens’ Rain and the Eames’ Blacktop: The Washing of a School Play Yard allow us to enjoy the ways that ordinary sights can yield unexpected abstraction. Sometimes we toggle back and forth, as when in Ken Jacobs’ Tom, Tom, the Piper’s Son recognizable human figures, however grainy, jump into sheer blotchiness and then back into something like legibility. But other times we can’t ever tell what we’re seeing. Brakhage’s Fire of Waters offers one of the best examples I know, with its jagged bursts of light in a smoky void.

What am I seeing? The uncertainty was doubled during my visit to Ken Jacobs’ Nervous Magic Lantern performance at the Cinémathèque Française. I say “doubled” because at least with Fire of Waters and Tom, Tom I knew I was watching a film. With this display, What am I seeing? started as a question about the format itself. Was it a film, a video, or something else?

Then the question became the customary one. Off-white textures—pebbly, dribbly, stalagmite-like—swim in and out of focus. Some are viscous and globular, some are like tangled foliage. They seem to spiral, but actually (I put up a finger to measure) they barely move. The effect of movement is given by pulsations of pure black, breaking the lyrical effect of the surfaces with a harshness that becomes aggressive. Aggressive as well is the soundtrack, blocks of sound from subway platforms and traffic and kitsch Latin percussion, all played at high volume. The surfaces just keep shifting and not shifting, sort of rotating while jabbing out at us, lovely and anxiety-inducing at the same time.

At the end of the performance, people crowded around the cardboard booth in the middle of the theatre. As Ken and Flo Jacobs packed up, they showed how they had generated the effects. What had I been seeing? Neither a film nor a video but a true magic-lantern display, assembled on the spot. But what had I been seeing? Something created with home-made equipment of a startling simplicity. (Strapping tape was involved.) Our magicians explained their tricks, like magic-lantern operators of earlier centuries explaining the science behind their shows. But I think it’s best that you not know until after you have a chance to see what they create.

In earlier entries (here and here) Kristin and I have praised Jacobs’ films for showing how very slight adjustments in technique or technology can create disturbing cinematic illusions. In this vein, the first item on the Cinémathèque program, a video called Gift of Fire, turned Louis Le Prince’s brief 1888 street scene into a 3D movie. (The homage was appropriate because Le Prince experimented with multiple-lens cameras.) The Nervous Magic Lantern performance generated a different sort of illusion, one conjuring up micro-landscapes and otherworldly vortices. In all, Jacobs makes us realize how many evocative effects are still to be discovered by tinkering with images thrown on a screen.

Detour to Berlin

KT here:

As David mentioned in last week’s entry, I took a week in the middle of our visit to Europe for research at the Ägyptisches Museum in Berlin. The staff there welcomed me into their storerooms, and I spent the days looking at fragments and the records of their discovery and the nights downloading and backing up my photos. No time for filmgoing. The most I managed was a trip to the well-stocked arts bookshop Bücherbogen, which has one of the best selections of film books to be found in Germany. Our old friend, experimental filmmaker Carlos Bustamente, met me there, and we had a quick cup of tea–most welcome on a cold morning when the results of the biggest snowfall in decades were still blanketing many sidewalks and roads.

I did note one film-related phenomenon, however. Every day I took the S-Bahn from Savignyplatz to Friedrichstrasse. The tracks pass directly across the street from the Theater des Westens (that is, the western part of Berlin). It was playing Der Schuh des Manitu, a musical version of the  highly successful 2001 German film of the same name. (I hope the publicity photo at the left was taken in warmer weather than I experienced.) I mentioned the film here, in reference to the fact that every major producing country, and some minor ones as well, turn out their own local comedies, films that don’t travel well but are very popular locally.

highly successful 2001 German film of the same name. (I hope the publicity photo at the left was taken in warmer weather than I experienced.) I mentioned the film here, in reference to the fact that every major producing country, and some minor ones as well, turn out their own local comedies, films that don’t travel well but are very popular locally.

By now it’s a familiar phenomenon in the U.S. for successful Hollywood films to be turned into stage musicals. It wasn’t always so. Back in the 1950s and 1960s, films were made of popular musicals, sometimes successfully, as with My Fair Lady, and sometimes not, as with Mame. But now the trend is the other way, with everything from Shrek to Hairspray getting the Broadway treatment.

It’s interesting to know that the same thing goes on abroad, though I’m not sure how prevalent such adaptations are. Der Schuh des Manitu, directed by Michael “Bully” Herbig, remains the highest grossing German film. Herbig doesn’t act in the stage play, as he did in the film, but he served as a creative advisor. The musical is a hit, having premiered on December 7, 2008 and it is expected to continue until at least the autumn of this year. There are several clips from both the film and the musical on YouTube. This one, at 8 minutes, gives a generous dose of the show. There are no subtitles.

I had only a couple of days back in Paris before we headed for Brussels for the final week of our trip. The German theme continued, since a few of the 1910s films David needed to see at the Cinematek here were German. The one I most wanted to see was Edmund Edel’s 1916 feature, Doktor Satansohn. Its main claim to fame is probably the fact that Ernst Lubitsch plays the title role. My book with Lubitsch started with his 1918 move to features, when he began to concentrate more on directing and less on acting. By 1920, with Sumurun, he appeared onscreen for the last time; being discontented with his performance as the tragic clown, he decided it was time to move behind the camera for good.

In the short films he starred in before 1918, Lubitsch often played a brash, ambitious Jewish youth, as in Der Stoltz der Firma (“The Pride of the Firm,” 1914). In Doktor Satansohn he’s a physician with a magical machine that transforms older women into beautiful young ones. We’re first introduced to a couple and the wife’s mother. When the latter makes a pass at her son-in-law and is rejected, she seeks the doctor’s help. His machine works by capturing the wife’s essence in a statuette and making the mother look like her daughter. Problem is, every time she’s about to kiss the husband, the doctor pops up with his devilish leer, visible only to the “wife.” David and I decided that the film is a comedy, though perhaps one only Germans of the day would find truly amusing. For one thing, the title character is clearly a Jewish caricature, one played to the hilt by Lubitsch. He decorates his machine with the Star of David and a Hebrew inscription (not to mention vipers and an image of Saturn).

Stylistically it’s a fairly conventional film for its day, though the black background of the doctor’s office, with its stylized youth machine and satyr-like bust, gives a hint of Expressionism to come. (See our topmost image.) Inevitably near the end there comes the moment beloved of historians of pre-World War II German cinema. The real daughter, released from her imprisonment in the statuette, confronts her double in the doctor’s waiting room. The Doppelgänger motif strikes again.

I wonder if German films actually have more Doppelgängers in them than appear in other national cinemas. Do they really reflect the disturbed soul of the nation? Or did the possibilities of filmic special effects draw moviemakers to try and multiply single figures? Georges Méliès and Buster Keaton used in-camera techniques to multiple their own figures in virtuoso displays. I recall being impressed by The Parent Trap‘s duplication of Hayley Mills when I saw it as a kid, and the whole notion of a single actor playing twins and other lookalike relations is a common enough convention. In Doktor Satanssohn, the doubled figure appears only in this one shot, and it’s the leering Lubitsch, delighted with his own nastiness, who walks off with the picture.

The 1910s, again, and still

DB again:

We saw Doktor Satansohn while I was studying staging and cutting strategies of the 1910s, thanks to the remarkable holdings of the Royal Film Archive of Belgium, also known as the Cinematek. My comments on last summer’s visit are here.

Another German film, in a choppy Russian print, vouchsafed a new glimpse of Asta Nielsen. In Totentanz (Urban Gad, 1912), she plays a guitarist-dancer who must take to the stage to support her infirm husband. She attracts the devotion of a composer, and soon she feels attracted to him. Torn between desire and duty, she snaps during a rehearsal of his latest piece, “Totentanz.” In a chilling gesture, she uses his dagger to slice her lute strings.

Soon the two are locked in a violent erotic struggle, and a stabbing ensues. In all, melodrama as ripe as one could want.

As ever, I was happy to have my hypotheses about tableau staging confirmed by several of the titles I saw. A minor French bedroom farce, Le Paradis (M. G. Leprieur, 1914 or 1915), had a brief passage of the sort of blocking and revealing we find in many films of the period. The painter Raphael Delacroix (no kidding) is pretending to be the lover of Claire Taupin to deflect the advances of randy M. Pontbichot. But Claire is actually the mistress of M. Grésillon. . . .

First, very frontal staging strings out Pontbichot, Raphael, and Claire. The older man relents in his pursuit of her.

In the vivid depth characteristic of the tableau tradition, Pontbichot withdraws. But his position accentuates that central door, which starts to open.

Most remarkably, Pontbichot ducks almost entirely behind the couple, giving pride of place to M. Grésillon’s arrival in the center of the shot.

Pontbichot slides out in time to register Grésillon’s outraged reaction to finding his mistress in another man’s arms.

Grésillon rushes to the frontal plane, furious. As ever, a thrust to the foreground creates a major spatial/ dramatic event.

Although the Le Paradis passage is ABC compared to the emotionally powerful patterns of staging we find in Ingeborg Holm (1913), it illustrates how even average films could resort to the blocking/ revealing tactic within the deep-space geometry of the tableau.

More flamboyant was Il Jockey della Morte (1915), an Italian circus film made by the Dane Alfred Lind. Its bold lighting and varied angles on the Big Top recalled the Danish films of a few years before. Halfway through, Lind launches a dazzling chase that features leaps from a tall bridge and bicycling stunts on a cable stretched across a river.

Another Italian film, this time a diva vehicle, suggests that by 1917 1923 (see below) the tableau style was already giving way had given way to scenes organized around close shots. (See below.) L’Ombra (Mario Almirante) starred Italia Almirante Manzini as a lively, trusting wife who becomes paralyzed. While her husband betrays her with her younger protégée, she gradually recovers bodily movement. Yes, a paralyzed diva seems a contradiction in terms, but one small-scale scene shows a remarkable range of emotions. Berta’s hands start twitching, one lifts up, and she stares wildly, as if it were an alien being.

In an earlier scene, Berta had asked that a mirror facing her be tipped upward so that she would never see herself sitting immobile. This shot pays off now, when the hand ascends almost magically into the bit of reflection she can see.

When the hand descends, her astonishment turns into joy. She experimentally shoves the hands together, as if asserting her control.

In the end, she kisses her hands as if they were pampered children.

Manzini runs through many more micro-emotions than I’ve indicated here, but this sample is typical of the ways in which L’Ombra avoides the long-shot choreography of only a few years before and builds a performance out of face, body, and arms in a close framing. The mirror-shot motif shows that fairly careful filmic construction was emerging at this point too.

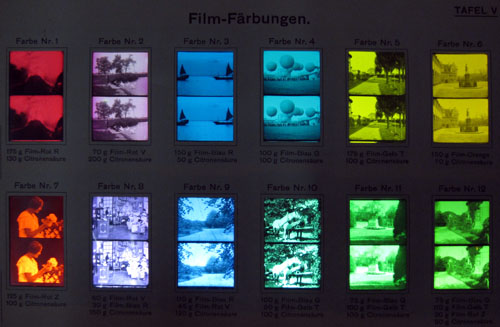

During my stay, I learned more about tinting and toning from the ever-helpful Noël Desmet. On the seldom-seen World War I drama L’Empreinte de la patrie (M. Dumeny, 1915), some images had curious oscillating patches of rusty brown. Noël explained that when Prussian Blue toning was combined with rose tinting, the chemicals eventually reacted to alter the pink cast. An example is shown at the top of this section, though the blue is more saturated in the original.

Once we get back to Madison, I’ll have to sort out all that I’ve learned from these movies. Onward and upward with the 1910s!

For more on Jacobs’ Nervous Magic Lantern, see Scott Foundas’ interview here. The Youtube clip doesn’t do the spectacle justice. If you must know something of Jacobs’ tools, the Dailymotion video from the performance I saw offers some clues. My notions about 1910s staging are laid out in On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light. You can also find several discussions in earlier entries on this site. Just execute a search on tableau.

Now is a good time to thank Noël Desmet and Marianne Winderickx, both of whom are retiring from the archive in March. The research that Kristin and I have done over the years owes an enormous lot to them, and of course to the Director of the Cinematek Gabrielle Claes.

P.S. 15 November 2013: Ivo Blom has pointed out that the version of L’Ombra I saw wasn’t from 1917 but rather from 1923. Hence the corrections above. Thanks very much to Ivo! Go here for his blog and information about his newest publication on silent Italian cinema.

A tinting and toning sample card from the early 1920s. Courtesy Noël Desmet.

Paris fun, in at least three dimensions

What he saves films from: Serge Bromberg faces down the flames.

We’re ending the first week of three in Paris. At the invitation of Jean-Loup Bourget and Françoise Zamour, David is giving three weekly lectures at the École Normale Superieure. He’s introducing some ideas about the development of film style in the 1910s and early 1920s, updated with new material from his summer research in Denmark and Brussels. Jean-Loup and Françoise have proven excellent hosts, and the first lecture seemed to go well.

We thought that Paris in January might be chilly and rainy, but we figured it had to be warmer than Madison. It turned out that Paris is experiencing unusually cold weather—about what would be normal in Wisconsin. There was light snow yesterday and last night, and the wind-chill factor was enough to turn our fingers numb if we stayed out long enough. The fountain in the center of the intersection at the northeast corner of the Jardin de Luxembourg has gradually become an iceberg.

We thought that Paris in January might be chilly and rainy, but we figured it had to be warmer than Madison. It turned out that Paris is experiencing unusually cold weather—about what would be normal in Wisconsin. There was light snow yesterday and last night, and the wind-chill factor was enough to turn our fingers numb if we stayed out long enough. The fountain in the center of the intersection at the northeast corner of the Jardin de Luxembourg has gradually become an iceberg.

Turns out, though, that it is still warmer than Madison, which is having highs in the single digits, as the weather forecasters say, and lows below zero. We’re better off here, though we wish we had brought our parkas.

It’s like Avatar, but much shorter

KT here:

The cold has driven us indoors, to museums and movies. As always seems to be the case, the Cinémathèque Française is hosting retrospectives of American films—in this case works by Laurel and Hardy and Gordon Douglas. There’s also a 3D series, which caught our attention right away. It’s not just your standard Kiss Me Kate and Dial M for Murder programming. In addition to such classics, there are many obscure films. We happened to arrive in time for the final two programs of the series, which ran from December 16 to January 3.

Our first full day in Paris ended with an evening of shorts presented by Serge Bromberg, who in 1985 founded Lobster Films. Lobster has put out many DVDs by now, some of which we have reported on previously, here and here. In July, one of our entries on Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna mentioned that Serge presented a program of Georges Méliès films, in conjunction with the French release of Lobster’s huge DVD set of the great magician’s films.

Serge is quite a showman and obviously a popular figure, since there was a large crowd, including many families with children. On Saturday he chose and introduced a set of short 3D films in his series of programs usually titled “Retour de Flamme,” or “Saved from the Flames.” To begin the evening’s entertainment, he explained how, unlike modern celluloid 35mm film, the nitrate variety used up until the early 1950s ignites and burns easily. With the help of a rightly apprehensive volunteer holding up a film-can lid, Serge showed how modern celluloid catches fire only briefly and then dies out. The few inches of nitrate, however, flared up quickly.

Serge introduced each film thereafter, playing the piano to accompany the silents. The audience had been given both anaglyph (red-green) and polarized glasses, and Serge’s introductions to the films gave us time to switch between systems.

Many of the shorts shown on the program are available on DVD or YouTube, but the 3D effect plays best on the big screen. The evening began with an unannounced item, Three Dimensional Murder, a “Metroskopics” comedy short from 1942. A nervous detective visits a mysterious house and encounters Frankenstein, creeping hands, skeletons, and other ghouls and beasties, all of which find some occasion to throw things or hurl themselves toward the camera. The humor is, as a contemporary audience member might have said, pure corn and the 3D effects repetitive, but it was certainly a rare item.

Next came one of the Fleischer brothers’ cartoon shorts, Musical Memories. It was made with a patented system that used three-dimensional models as settings against which 2D cartoon figures drawn on cels moved about. (Such models can be seen fairly often in Popeye and other Fleischer cartoons of the 1930s.) There is some sense of depth. Still, the effect is strange, since the models have shading and the flat-looking figures do not. The cartoons are not 3D in the sense we typically think of, since there are no glasses involved.

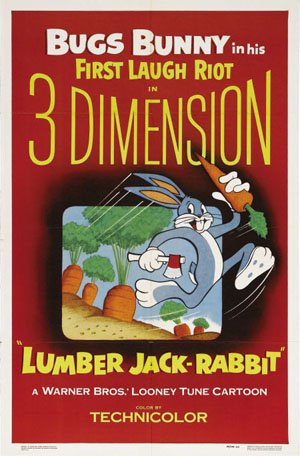

More cartoons followed, from the two main competing animation studios. Disney’s contribution was Working for Peanuts, a story set in a zoo with Chip and Dale stealing peanuts from an elephant and Donald Duck trying to foil them. Many a peanut seemed to fly out toward the spectator. Chuck Jones directed Lumber Jack-Rabbit (1954), a film that mixed size gags and spatial ones, with Bugs wandering into the domain of the gigantic Paul Bunyan. Perhaps not one of Jones’s best, but distinctly more interesting in 3D.

As Serge pointed out, most 3D technology was pioneered in the U.S. He included some exceptions, however, with a series of Soviet “Parade of Attractions” shorts shown at intervals during the evening. Experiments with underwater 3D photography and a garden of plants lacked soundtracks, but the final item, a vaudeville act with jugglers, had music and lots of bowling pins flying at the camera.

Unbelievably, there were efforts toward 3D as early as 1900. Serge showed some 3D experiments from that period by inventor Rene Bunzli. These were only about 10 seconds long and included a mildly risqué scene of a man arriving to visit his mistress and another discovering his wife in bed with her lover. The first color 3D film was shown: Motor Rhythm, made by Charley Bowers in 1940 for the Chicago Exposition and distributed by RKO. Using a combination of pixilation and 3D, the film shows a car jauntily assembling itself to a musical accompaniment, with many of the parts moving out toward the camera before attaching themselves in their proper places.

The National Film Board of Canada contributed Munro Ferguson’s Falling in Love Again, with characters wafted into the sky by road accidents and, while falling, falling in love. To watch it in high-quality 3D, go here. Pixar was represented by John Lasseter and Eben Ostby’s early digital experiment in 3D, Knick Knack, as a snowman trapped in a snow globe tries to break free to join a bathing beauty.

The evening ended with a surprise, two films that had never been meant to appear in 3D.

Méliès’s early shorts were often pirated abroad, and a lot of money was being lost in the American market in particular. After the Lubin company flooded that market with bootleg copies of a 1902 film, Méliès struck back by opening his own American distribution office. Separate negatives for the domestic and foreign markets were made by the simple expedient of placing two cameras side by side. The folks at Lobster realized that those cameras’ lenses happened to be about the same distance apart as 3D camera lenses. By taking prints from the two separate versions of a film, today’s restorers could create a simulated 3D copy!

Two 1903 titles–I think that they were The Infernal Cauldron and The Oracle of Delphi–triumphantly showed that the experiment worked. Oracle survived in both French and American copies, and the effect of 3D was delightful. For Cauldron only the second half of the American print has been preserved. Watching the film through red-and-green glasses, you initially saw nothing in your right eye, while the left one saw the image in 2D. Abruptly, though, the second print materialized, and the depth effect kicked in. The films as synchronized by Lobster looked exactly as if Méliès had designed them for 3D.

Film scholars gone wild

DB here:

William Cameron Menzies is most famous as an art director on films like The Thief of Baghdad (1924) and Gone with the Wind. He was one of the most visually daring artists to work in classic Hollywood; his eccentric framings and looming foregrounds may have influenced Orson Welles. (The Gothic distortions of Our Town and Kings Row are unlikely to be the creation of director Sam Wood.) Menzies also directed a few films, most notably the slightly nutty anti-Commie film The Whip Hand (1951).

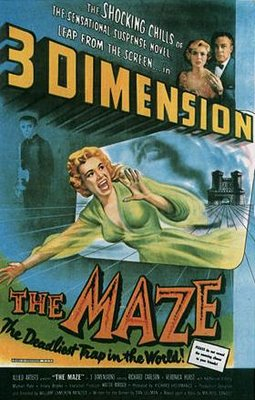

So Kristin and I had to go back to the Cinémathèque for Menzies’ rarely-seen 3D feature The Maze (1953). Alas, it was a washout. The feeble story concerns an heir returning to a castle to confront a giant frog, who may be his relative. I’d expected bravura deep-focus, with planes jutting out at me, but the film was dramatically and visually flat–no wordplay intended. The trailer, complete with fake bats on strings, is here.

We have other incidents to chronicle, but this dispatch can end with a quick list of some of the film friends we’ve encountered. We’ve already mentioned Professor Bourget, whose book on Fritz Lang came out recently (below left). We also ran into Cindi Rowell, an old friend from Pordenone and The Griffith Project, who had the excellent idea that we go to Chinatown–here hidden behind the facades of tower blocks. Cindi has vast experience in many aspects of film culture–preservation, programming, publication, web design, and the like–and is currently affiliated with the Middle East International Film Festival in Abu Dhabi.

Another old friend, Yuri Tsivian, is in Paris teaching during our visit, so we had a chance for a good dinner and lots of talk about editing in the 1910s. Below, he and Kristin pay homage to one of the shrines of Parisian cinephilia, the Studio des Ursulines movie theatre.

Left: Jean-Loup Bourget and his new book on Lang. Right: Yuri and Kristin at the Urselines.

Last night, with Kristin away in Berlin, I went to a dinner hosted by Jacques Aumont and Lyang Kim. Jacques is a major film theorist, whose many books and essays probe into the artistic qualities of cinema. His book on Eisenstein is available in English translation, as is his far-ranging study of the history and functions of images. Lyang is an outstanding photographer, whose book of haunting Christmas images Dans l’ombre de noël was just published in December. Among her pictures here are some gorgeous “fusion” images that recall our recent 3D experiences.

Then who should turn up but Marc Vernet and Rick Altman? It was an Iowa-Wisconsin reunion in the 10th. Marc is an expert on film noir, on cinematic images of absence, and on the American film company Triangle–associated with both Griffith and Ince. (Again, the 1910s.) Marc has set up a beautiful webpage full of information about early American cinema, and he blogs there frequently. Rick is known for his in-depth studies of film genre (especially the musical), film sound, and narrative theory. His most recent books, Silent Film Sound and A Theory of Narrative, are splendid contributions. Below, all four toast what turned out to be Rick’s birthday.

Today: More preparations for my lecture tomorrow, and of course at least one movie. Agora? Wiseman’s La Danse? Kinatay? The new Eugène Green, La religieuse portugaise? Or a rerelease (new print) of Minnelli’s Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse? Or….? The usual Parisian problem, but a good problem to have.

P. S. March 2010: After this Paris trip, I wrote an essay on William Cameron Menzies for this site.

Jacques Aumont, Lyang Kim, Rick Altman, and Marc Vernet, 9 January 2010.

The ten-plus best films of … 1919

KT here, with some help from DB:

Two entries are enough to create a tradition. Once again, at a time of year when critics are picking their 10-best lists for 2009, we jump back ninety years and give our choices for 1919.

(For our 1917 list, see here, and here for 1918.)

I remarked in last year’s post that it was a bit difficult to come up with ten films, a result perhaps of accidents of preservation or slackening of activity by certain major filmmakers. There was no such problem for 1919, and films had to be bumped off the initial list to keep it to ten. (In fact, you’ll notice we didn’t quite manage to keep it to ten.) Since some people may take these lists as a guide to exploring the cinema of the teens, we’re adding some also-rans at the end, all very much worth watching.

With 1919, we’re approaching the decade when many of the most widely known silent classics were made. Some titles on this year’s list will be very familiar. Erich von Stroheim’s first film came out in 1919, as did Carl Dreyer’s. Ernst Lubitsch, always a prolific director, was particularly busy that year. Other titles are less well-known, still being largely the province of silent-film festivals and archival research.

Three, sadly, are not available on DVD, and some others have to be ordered from sources in their countries of origin. In this day of internet sales around the world, such orders are not difficult. You need, however, a multi-region DVD player.

Charles Chaplin had long since left his knockabout comedy behind and was making more controlled, poetic films by  this point. The Little Tramp was beloved around the world, and numerous impersonators were turning out films to cash in on his popularity. Sunnyside is his most highly regarded film of 1919, in large part because of a dream sequence in which the Tramp wakes up by a little bridge to find himself welcomed by a bevy of wispily dressed young ladies. The subsequent open-air dance displays Chaplin’s extraordinary ability to inject humor into such a scene without marring its lyricism. (The only DVD version currently available in the U.S. is a fuzzy copy.)

this point. The Little Tramp was beloved around the world, and numerous impersonators were turning out films to cash in on his popularity. Sunnyside is his most highly regarded film of 1919, in large part because of a dream sequence in which the Tramp wakes up by a little bridge to find himself welcomed by a bevy of wispily dressed young ladies. The subsequent open-air dance displays Chaplin’s extraordinary ability to inject humor into such a scene without marring its lyricism. (The only DVD version currently available in the U.S. is a fuzzy copy.)

Cecil B. De Mille had begun his series of high-society battle-of-the-sexes films by this point. Male and Female differs from the others in that it is based on a prominent literary source, The Admirable Crichton, J. M. Barrie’s successful 1902 play. The plot involved the butler of a wealthy British family. He becomes their leader when the pampered group is cast away on an unpopulated island. A romance develops between the spoiled daughter, Lady Mary (Gloria Swanson), and Crichton (Thomas Meighan).

De Mille spiced up the story with a fantasy scene based on William Ernest Henley’s popular poem of 1888, “I was a King in Babylon.” It dealt with reincarnation, one of several spiritualist fads of the period, which also included psychic contact with the dead and the fairy photographs that deluded Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Crichton refers to the poem, leading into a scene of him as king in a Babylon. When a Christian slave girl rejects his advances, he orders her thrown to the lions. The scene providesa glimpse of the costume-epic style that De Mille would increasingly turn to as his career advanced.

Henley, by the way, is largely forgotten today, but another of his poems, “Invictus,” inspired Nelson Mandela and lends its name to the latest Clint Eastwood film.

D. W. Griffith released an impressive lineup of features in 1919, despite the fact that he was also acting as the producer for other directors. His output includes a charming set of pastoral stories A Romance of Happy Valley, True Heart Susie, and The Greatest Question; a belated war film, The Girl Who Stayed at Home; a Western, Scarlet Days; and a melodrama that ranks among his most admired films, Broken Blossoms. Griffith’s status within the industry was  reflected by the fact that this same year same the formation of United Artists as a company to distribute films by him and the other founders, Chaplin, Mary Pickford, and Douglas Fairbanks.

reflected by the fact that this same year same the formation of United Artists as a company to distribute films by him and the other founders, Chaplin, Mary Pickford, and Douglas Fairbanks.

Broken Blossoms owes its simplicity to the fact that Griffith was then making a series of films based on short stories. The title of Thomas Burke’s “The Chink and the Child” sounds offensive today, but it was an ironic reference to the epithet forced upon an idealistic young Chinese man who comes to London’s grim Limehouse district and becomes disillusioned. He falls in love with the delicate Lucy, abused by her violent, drunken father. These three form the main characters. Another Chinese man lusts after Lucy, but for once in Griffith’s work, the sexual threat to the innocent heroine takes second place to her abuse by her father. Lillian Gish and Richard Barthelmess convey the quiet resignation that at intervals gives way to Donald Crisp’s vicious outbursts.

Apart from the strong performances from the three leads, the film was perhaps the first to consistently use the “soft style” of cinematography, an approach that borrowed from a recently established trend in still photography. The hazy views of the Chinese setting in the opening and of the Limehouse docks later on would be enormously influential on films of the 1920s.

Raymond Longford is far and away the least known of the directors in this list. Films were increasingly being made in countries outside the U.S. and Europe, but few have survived. Longford’s The Sentimental Bloke is widely held to be the first major Australian film and perhaps the best of the silent era. Based on a verse poem using vernacular language and serialized from 1909 to 1915, it was set among working-class characters and filmed on location in an inner-city district of Sydney. It follows the reformation of the Bloke, a drinking, gambling man reformed by his love for Doreen. The film’s original intertitles, based on the poem and told in first person by the hero, were too colloquial for Americans to comprehend, and the film failed there, even after a new set of intertitles were substituted.

Raymond Longford is far and away the least known of the directors in this list. Films were increasingly being made in countries outside the U.S. and Europe, but few have survived. Longford’s The Sentimental Bloke is widely held to be the first major Australian film and perhaps the best of the silent era. Based on a verse poem using vernacular language and serialized from 1909 to 1915, it was set among working-class characters and filmed on location in an inner-city district of Sydney. It follows the reformation of the Bloke, a drinking, gambling man reformed by his love for Doreen. The film’s original intertitles, based on the poem and told in first person by the hero, were too colloquial for Americans to comprehend, and the film failed there, even after a new set of intertitles were substituted.

The Sentimental Bloke was restored in 2004 and this past April appeared in a DVD set prepared by the Australian National Film & Sound Archive. A supplementary disc includes historical material, information on the new musical accompaniment, and an interview with Longford. A book of historical essays is also included in the box, which is available directly from the DVD company Madman. (Note that although there is no region coding, it is in the PAL format.)

When I was studying film in graduate school, Ernst Lubitsch’s German period was known mainly for the 1919 historical epic Madame Dubarry. There was little known about the two comedies that came out that year, perhaps the most amusing and delightful of all his German films in this genre: Die Austernprinzessin (“The Oyster Princess,” though seldom called by that title) and Die Puppe (“The Doll,” also a little-used name).

It’s hard to choose which of these three is Lubitsch’s best for the year. Ironically Madame Dubarry isn’t watched much any more, and it’s not on the recent DVD set “Lubitsch in Berlin,” though the two comedies are. Complete prints are rare, due in part to censorship. (If the print you see ends with a close-up of the heroine’s head held up after she is executed, you’ve probably been watching a reasonably complete version.) It may seem a bit stodgy upon first viewing, but I warmed up to it during repeated screenings while researching my book on Lubitsch’s silent films. There are many excellent moments: the extended series of eyeline matches when Louis XV first sees Jeanne, the masterfully timed and staged long take when Choiseul refuses to let Jeanne accompany Louis’s coffin, and a meeting among the revolutionaries that ends as Jeanne reacts in horror to their bloodthirsty plans, backing dramatically into shadow in the background (below).

Given how different these films are, I’m going to declare a tie between Madame Dubarry and one of the comedies. Wonderful though The Oyster Princess is, I’m opting for Die Puppe (above). Its story-book opening and stylization are charming. The hilarious scenes in the doll workshop and the monastery full of greedy monks fill out the plot, making it considerably denser than that of Die Austernprinzessin.

As with Lubitsch, when I was first studying film and for many years thereafter, Swedish director Mauritz Stiller was known mainly for one film, Sir Arne’s Treasure (Herr Arnes Pengar), though an abridged version of The Saga of Gösta Berling also circulated. Sir Arne’s Treasure was assumed to be his masterpiece. The gradual rediscovery and restoration of other Stiller films from the 1910s has considerably broadened our view of him. Perhaps Sir Arne’s Treasure is not the solitary, towering masterpiece it was long thought to be. Still, it holds up well upon revisiting.

It is a period piece set in a small seaside community. A group of foreign men massacre most of a family, in search of their mythical riches. They are forced to remain in the village when the ship in which they are to sail becomes  icebound. The surviving daughter of the family unwittingly falls in love with one of the killers.

icebound. The surviving daughter of the family unwittingly falls in love with one of the killers.

Sir Arne’s Treasure was one of the films which gained the Swedish cinema of the 1910s the reputation for brilliantly exploiting natural landscapes. Few silent films have exploited actual winter settings so well. The actors are clearly working in genuine snow; one can sometimes see their breath fog as they speak. Atmospheric shots show the wind sweeping snow across the ice. Stiller uses the blank backgrounds created by the snow to create stark, simple compositions of dark figures and objects.

Kino’s DVD release uses a print from Svensk Filmindustri’s own archives. To my eye, the tinting used is too dark, especially since much of the action naturally takes place in the dark of the northern winter days. Deep blues somewhat obscure parts of the action. Still, the darkness adds to the brooding tone that pervades the story.

Erich von Stroheim’s first film, Blind Husbands, is the only one he completed that has come down to us in more or less its original version. As the director’s artistic ambitions expanded, his studios’ willingness to accommodate the growing  length and scope of his films diminished. His features of the 1920s were re-edited without his consent, most notoriously when the eight-hour naturalistic film Greed (1924) was released in a version that ran little more than two hours. For many the original remains at the top of the wish list for lost films to be recovered someday. (Number one on my list is Lubitsch’s Kiss Me Again, released in 1925 just before his masterpiece, Lady Windermere’s Fan.)

length and scope of his films diminished. His features of the 1920s were re-edited without his consent, most notoriously when the eight-hour naturalistic film Greed (1924) was released in a version that ran little more than two hours. For many the original remains at the top of the wish list for lost films to be recovered someday. (Number one on my list is Lubitsch’s Kiss Me Again, released in 1925 just before his masterpiece, Lady Windermere’s Fan.)

Blind Husbands is my favorite among von Stroheim’s films. It tells its story of sin and punishment with a lighter touch than his later films would. The director plays a would-be seducer of a neglected wife when the group converges in a village for a mountain-climbing vacation. Von Stroheim’s eye for striking compositions against the snow-clad landscapes and his skillful use of the inn’s hallways and doors to convey the characters’ shifting relationships show an already mature grasp of the art form. (See right, where the villain eyes the heroine in her room but is himself watched by the protective guide in the hallway between the rooms.)

Maurice Tourneur’s Victory runs a mere 63 minutes in its current version, but the original footage count suggests that what we have is substantially complete. That’s somewhat short for a feature by a major director at this point in history, but the simple, intense plot, based on a Joseph Conrad short story, benefits from the compression. The protagonist is a man who has escaped his past and lives as a virtual hermit on a South Seas island. Attracted despite himself, he befriends a young woman playing in a visiting orchestra and rescues her from the abuse of the orchestra’s owner and the lustful advances of the local hotel owner. Returning with the woman to his lonely island, he faces the intrusion of three thugs deceived by the vengeful hotel owner into thinking that the hero has riches hidden on his island.

By this point Tourneur has fully mastered the “rules” of classical continuity style and of three-point lighting. Many of the compositions in Victory look like they could have been made in the 1930s. When I first saw the film about thirty years ago, I found the earliest case of true over-the-shoulder shot/reverse shot that I had ever seen:

Since then, David has found an earlier one that sort of qualifies (maybe more on this in an upcoming entry), but this is a purer case.

Tourneur had also developed a distinctive approach to filming settings in long shot with framing elements within the mise-en-scene and figures silhouetted in the foreground (see top). In general the lighting is superb. Few Hollywood directors had reached this level of sophistication by 1919.

Victory has been released on DVD largely because it features Lon Chaney as one of the thugs. Image offers it paired it with another Chaney film. For some reason the titles are out of focus, but the rest of the film fortunately is in good condition and presents Tourneur’s visual style well.

DB’s picks:

Carl Theodor Dreyer began his film career writing scripts at the powerful Danish studio Nordisk. When he started directing, however, World War I had destroyed Nordisk’s markets, and the American cinema was on the rise. Dreyer’s generation was the first to register the impact of the emerging Hollywood cinema, and he displayed his understanding of Griffithian technique in The President (Praesidenten).

The English title should probably be something like “The Head Magistrate” or “The Presiding Judge,” and the plot appropriately sets up a tension between justice and personal obligation. One of Nordisk’s favored genres was the “nobility film,” in which illicit passion plunges a wealthy man or woman into the lower depths of society. Dreyer gave the studio a nobility film squared, using flashbacks to show how two generations of men in a family have seduced working-class women. The present-day drama displays the crisis that ensues when a respected judge realizes that the woman to be tried for infanticide is his illegitimate daughter. Dreyer’s abiding concern for the exploitation of women under patriarchy begins in his very first film.

From the early 1910s, Danish films displayed a mastery of tableau staging and careful pacing. But The President bears the mark of American technique in its bold close-ups and reliance on editing to build up its scenes. (There are nearly 600 shots in the film, yielding a rate of about 8.8 seconds per shot—quite swift for a European film of the era.) Perhaps more important are Dreyer’s efforts to shove aside the heavy furnishings of bourgeois melodrama. Compare the overstuffed set of Hard-Bought Glitter (Dyrekobt Glimmer, 1911) to this daringly bare one, with its sweep of cameos.

In the late teens, other Danish directors were moving toward simpler settings, but The President carries this tendency to geometrical extremes. Dreyer’s walls, bare or starkly patterned, isolate the players’ gestures and heighten moments of stasis. The result is one of the most adventurously designed film of its time, and if some of its experiments do not quite come off, already we can see that impulse toward abstraction that would be given full rein ten years later in La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc. The all-region DVD from the Danish Film Institute provides a somewhat dark tinted copy with original intertitles and English translations.

Dreyer deeply admired Victor Sjöström, who had already given Swedish cinema some of its enduring masterpieces: Ingeborg Holm (1913), Terje Vigen (1917), The Girl from Stormycroft (1917), and The Outlaw and His Wife (1918). Sjöström would go on to make The Phantom Carriage (1921), The Scarlet Letter (1926), and The Wind (1928). Several other outstanding movies he signed remain little known; worth watching for are The Girl from Stormycroft (1917), Karin Ingmarsdotter (1920), and the deeply moving Mästerman (1920; look for this on our list next year). Among these unofficial classics Sons of Ingmar (Ingmarssönerna, 1919) stands out especially.

Dreyer deeply admired Victor Sjöström, who had already given Swedish cinema some of its enduring masterpieces: Ingeborg Holm (1913), Terje Vigen (1917), The Girl from Stormycroft (1917), and The Outlaw and His Wife (1918). Sjöström would go on to make The Phantom Carriage (1921), The Scarlet Letter (1926), and The Wind (1928). Several other outstanding movies he signed remain little known; worth watching for are The Girl from Stormycroft (1917), Karin Ingmarsdotter (1920), and the deeply moving Mästerman (1920; look for this on our list next year). Among these unofficial classics Sons of Ingmar (Ingmarssönerna, 1919) stands out especially.

A prologue shows lumbering, somewhat thick-headed Ingmar climbing a ladder to heaven, where generations of Ingmars sit in dignity around a massive meeting-room (see below). There his father tells him that he must find a wife. But Ingmar then explains that he once took a wife, with unhappy results. Some long flashbacks ensue, showing Ingmar forcing a young woman to marry him. The plot takes some doleful turns, with the result that the woman is sent to prison.

Running over two hours (and initially released in two parts), Sons of Ingmar has a fittingly lengthy climax that portrays the pains of reconciliation between a sensitive woman and an inarticulate man. In the film’s final scenes, Sjöström risks a delicate emotional modulation that would daunt a director today. Using Hollywood continuity cutting with a casual assurance, he relies on subtly timed cuts and changes of shot scale to trace the couple’s wavering guilts and hopes. These last scenes have a human-scale gravity that balances the weighty paternal authority of the heavenly sequences. In Theatre to Cinema our colleagues Lea Jacobs and Ben Brewster have written a penetrating analysis of the performances of Sjöström as Ingmar and Harriet Bossa as Brita.

Unhappily, we know of no video version of this wonderful film. It should be a top priority for DVD companies specializing in silent cinema.

Another 1919 candidate for ambitious DVD purveyors is Louis Feuillade’s great serial Tih Minh. It has been overshadowed by Fantômas (1913-1914), Les Vampires (1915-1916), and Judex (1917), but it has a playful charm of its own. It is, in a way, the anti-Vampires. Instead of chronicling the triumphs of an all-powerful secret society, this six-hour saga gives us a few ill-assorted conspirators who inevitably fail at every scheme they try. The plot is no less far-fetched than that of the earlier serial, but the twists are more comic than thrilling. (Which is not to say that we’re denied some astonishing real-time stunt work performed by the actors, as above.) The film’s genial tone assures us that nothing bad will happen to the poor girl Tih Minh, but the villains will get enjoyably harsh punishment. In the course of the adventure three couples are formed, the routines of provincial life are filled in with leisurely detail, and the whole thing ends with a big wedding.

Unlike the Paris-bound serials, Tih Minh allowed Feuillade to apply his elegant staging skills to natural landscapes. By now he was filming in Nice, and the chases and fistfights are enhanced by gorgeous mountains, vistas of water, and hairpin roads. More than one connoisseur has confessed to me that this is their favorite Feuillade serial, and it’s hard to disagree. I always find that viewers are carried away by its zestful tale of good people who come to a good end.

DB’s runner-ups: Perhaps not as fine as the above, but definitely of bizarre interest, are two Robert Reinert films from 1919. The title of Opium pretty much sums up this fevered movie. It includes sinister Asians, drug-addled doctors, a lions’ den, and Conrad Veidt in a suicide-haunted performance that makes his Cesare role in Caligari look underplayed (see right). Later in the same year Reinert gave us an even more overwrought tale, Nerven. This is a movie about collapse–the collapse of a community, of a business, and of the tormented minds of buttoned-up citizens. Reinert renders melodrama in images of controlled frenzy unlike any others I know from the period. Had his films been as widely seen as the official Expressionist classics, I think he would be much admired today. I analyze these two movies in Poetics of Cinema, and say a bit about them in this entry. A DVD of Nerven is available from the Munich Film Archive.

DB’s runner-ups: Perhaps not as fine as the above, but definitely of bizarre interest, are two Robert Reinert films from 1919. The title of Opium pretty much sums up this fevered movie. It includes sinister Asians, drug-addled doctors, a lions’ den, and Conrad Veidt in a suicide-haunted performance that makes his Cesare role in Caligari look underplayed (see right). Later in the same year Reinert gave us an even more overwrought tale, Nerven. This is a movie about collapse–the collapse of a community, of a business, and of the tormented minds of buttoned-up citizens. Reinert renders melodrama in images of controlled frenzy unlike any others I know from the period. Had his films been as widely seen as the official Expressionist classics, I think he would be much admired today. I analyze these two movies in Poetics of Cinema, and say a bit about them in this entry. A DVD of Nerven is available from the Munich Film Archive.

KT’s runners-up: I suppose that there will be some tongue-clicking over the fact that Abel Gance’s J’accuse! is not present in our list. There’s no doubt it’s historically important and influential, but it’s also heavy-handed and doesn’t add the leavening of humor to its melodrama, as some of the above films do. But it does deserve a mention in an overview of 1919. (I’ve posted about what I see as Gance’s limitations here.)

Last year I put Marshall Neilan’s Mary Pickford vehicle, Stella Maris, in the top ten. I’d be tempted to do the same with his (and her) Daddy-Long-Legs, but this year there’s a lot more competition. But it’s a charming film, and the great cinematographer Charles Rosher provides another series of beautiful images using the new three-point lighting system. It was the first Pickford film into Germany after the war and considerably influenced Lubitsch and other German directors.

Similarly, in a year with fewer major films, Victor Fleming’s When the Clouds Roll By, a wacky, inventive tale of superstition and psychological manipulation starring Douglas Fairbanks, would make the main list. David illustrated some of that inventiveness in his epic entry on Fairbanks.

Within a few years, compiling our 90-year picks will become increasingly difficult. Experimental cinema will blossom, as will animation. The Soviet Montage and German Expressionist movements will get started, and French Impressionism, still a minor trend in the late teens, will expand. Filmmakers like Murnau, Lang, Vidor, and Borzage will gain a higher profile, and more films by veteran directors like Ford will survive. Maybe we’ll have to expand the annual list even further. . . .

A very happy New Year to all our readers! Assuming we make it through the security lines, we shall be celebrating New Year’s Eve on a plane bound for Paris, where David will be doing a lecture series over the first few weeks of January. Paris is the world capital of cinema, at least as far as the diversity of films on offer goes, so we shall no doubt find occasion to blog while there.

Sons of Ingmar.