Archive for the 'National cinemas: France' Category

A many-splendored thing 5: Sampling

Sakuran.

From DB:

While I’ve been here, Hong Kong has been embroiled in two big stories. First is the runup to the election for chief executive. Hong Kong has indirect elections, whereby groups purportedly representing constituencies, chiefly various business interests, are in turn represented by electors. On the day of the vote, I saw several demonstrations demanding both new environmental policies and universal suffrage. So much for the myth that Hong Kong people don’t participate in politics.

While I’ve been here, Hong Kong has been embroiled in two big stories. First is the runup to the election for chief executive. Hong Kong has indirect elections, whereby groups purportedly representing constituencies, chiefly various business interests, are in turn represented by electors. On the day of the vote, I saw several demonstrations demanding both new environmental policies and universal suffrage. So much for the myth that Hong Kong people don’t participate in politics.

Current chief executive Donald Tsang Yam-kuen, Beijing’s appointee, won the election, with 649 votes out of 789 voting members. Tsang has promised to introduce direct voting and universal suffrage by 2012. We’ll see.

The other big story has been the aftermath of a 2006 shootout involving police constable Tsui Po-ko. The latter has the confusing intricacy of a Hong Kong cop movie. Some years ago Tsui allegedly killed another cop and stole his pistol; a year later he robbed a bank. (The Economist offers a summary here.) An inquest has been under way. Wednesday’s South China Morning Post (not available free online) reports on the contents of Constable Tsui’s notebooks. There are indications that he was tailing political figures and calculating how an ambush might be carried out beneath traffic underpasses.

The media have gone wild over this and even replayed the episode of the local version of Who Wants to Be a Millionaire? on which Tsui appeared as a contestant. Today’s edition of the SCMP reports an even weirder turn. An FBI expert has testified that Tsui suffered from schizotypal personality disorder. This is characterized by “social isolation, odd behavior and thinking, and often unconventional beliefs.” Sound like you or me?

Moving to the more comforting world of cinema, let me catch up on some of the films I’ve seen at Filmart and the Hong Kong International Film Festival.

Ying Liang’s The Other Half: A shrewdly constructed story about a young woman with marital troubles who becomes a legal stenographer. Ying interweaves her life crises with the monologues of locals who come to seek action from the lawyer. These incidents were derived, Ying explained in the Q & A, from actual cases the non-actors knew. Ying collected over 100 law cases and then showed his script to lawyers and legal professionals, some of whom appeared in the film. Single-take scenes predominate, making good use of the deep-focus capacities of digital video. A vivid angle into ordinary life in China, with insights as well into problems of industrial pollution.

Li Yu’s Lost in Beijing: Less interesting, I thought. A fairly traditional melodrama involving an innocent woman caught between two macho men, husband and boss, and the boss’s scheming wife. The glimpses of life in Beijing were more valuable than the supposedly scandalous sex scenes that feature heavily in the early reels.

Derek Yee’s Protégé: Yee is a mid-range Hong Kong director who can turn out solid entertainment and sometimes, as with One Nite in Mongkok, some social criticism. In Protégé, you know you’re in for a rough time from the start. A smack-addled mom staggers onto a sofa to die, and her little girl waddles over to yank out the needle and drop it carefully into a wastebin. Whether you love or hate The Departed, Protégé reminds us that Hong Kong film can chop closer to the bone than anything from our purportedly hard-edged directors.

Derek Yee’s Protégé: Yee is a mid-range Hong Kong director who can turn out solid entertainment and sometimes, as with One Nite in Mongkok, some social criticism. In Protégé, you know you’re in for a rough time from the start. A smack-addled mom staggers onto a sofa to die, and her little girl waddles over to yank out the needle and drop it carefully into a wastebin. Whether you love or hate The Departed, Protégé reminds us that Hong Kong film can chop closer to the bone than anything from our purportedly hard-edged directors.

Daniel Wu plays an undercover cop who’s taken years to become virtually a son to drug kingpin Andy Lau. Their intriguing relationship counterbalances Yu’s efforts to wean an addicted mother off the stuff. There are some fascinating quasi-documentary scenes of cooking heroin and harvesting Thai poppies. The parallels between the drug addicts whom Andy despises and his own need for shots of insulin are insinuated, not slammed home. Yee mixes grim realism with some showy melodrama, adding an explosive drug bust. (That sequence contains a startling shot that in itself justifies the existence of CGI.) Despite an overlong denouement and a few loose ends, the film seems to me better than the average local genre fare.

Ninagawa Mika’s Sakuran: Anachronism has a field day in this story of a cunning girl’s rise to be top geisha. Riotous sets and costumes, along with big-band swing music, create the suffocating but ravishing world of courtesans and their patrons. A sentimental ending telegraphed far in advance, but no less welcome for that.

Nicole Garcia’s Selon Charlie: Screened in Filmart, this 2005 pic seemed to me a solid if somewhat academic drama. A network narrative about a fugitive archaeologist in a town full of philandering husbands and bored wives, it’s your basic bourgeois life-crisis tale, decorated with parallels to a mysterious hominid found at a dig site. It has the usual Eurofilm tact and shows how the French have adapted Hollywood’s screenplay structure to fit the well-upholstered stories they like to tell.

Nicole Garcia’s Selon Charlie: Screened in Filmart, this 2005 pic seemed to me a solid if somewhat academic drama. A network narrative about a fugitive archaeologist in a town full of philandering husbands and bored wives, it’s your basic bourgeois life-crisis tale, decorated with parallels to a mysterious hominid found at a dig site. It has the usual Eurofilm tact and shows how the French have adapted Hollywood’s screenplay structure to fit the well-upholstered stories they like to tell.

Benoît Delépine and Gustave Kervern’s Avida: Black and white almost throughout, in 35mm that looks like muddy 16, this surrealist pastiche starts strong. Early scenes offer a new riff on Tati’s Mon Oncle, in which a toff returns to his cyberautomated mansion and encounters problems with dogs and plate glass. Then we’re in Buñuel-Carrière territory (Carrière is in the movie), as a dognapping leads to an amazing scene of pooch decapitation. Things seemed to me to drag as the episodes got sillier and less visually expressive. Rhinos, lions, elephants, big beetles, and a highly diverse sampling of the human species do walk-ons. Not so much metaphysical as pataphysical.

Iran: A Cinematographic Revolution: A documentary on the pre-1990s Iranian cinema. It’s informative, cautious about the role of the mullahs, and filled with intriguing clips from Hollywood-style melodramas and the neorealist-flavored efforts of the 1970s. Good talking heads too (though no Kiarostami). The film reaffirms how single-mindedly the cinema agencies pursued film festivals as a way of increasing the profile of the nation’s culture; the motto was “No festival without an Iranian film.” But can Iran really have trained a total of 90,000 film-related workers, as the docu says?

Johnnie To’s Exiled: I hadn’t yet seen it on the big screen. That’s where it belongs. The first sequence evokes Once Upon a Time in the West‘s opening, and it’s followed by an exhilarating, utterly implausible gun battle. Watch out for that spinning door!

When Mr. To previewed this opening for me last spring, I didn’t think he could top it, but he does. The later scene in the underground clinic will rank with one of the great action sequences of all time. I won’t spoil it for those who haven’t seen it by previewing a still. Let’s just say that To finds fresh compositional tactics in close quarters, as in the hotel climax.

Full of visual invention and neat character bits, Exiled shows that To keeps trying new things. I wrote a little about To’s style in an earlier post, and some backstory on the Exiled rooftop sets can be found here.

Cheang Pou-soi’s Dog Bite Dog: This tale of a hired killer from Thailand and the raging young cop who pursues him presents a world in Hobbesian frenzy, with all against all. The most unrelentingly violent Hong Kong film I’ve seen in years, Dog Bite Dog starts with imagery of the killer hiding in the bowels of a ship, scraping up flecks of rice from the floor. After consummating his hit, he moves through a landscape of garbage, hiding out in a landfill and rummaging in a recycle bin for scraps to doctor a girl’s wounded foot. I don’t know any film that insists so intently on the textures of urban offal.

Cheang Pou-soi’s Dog Bite Dog: This tale of a hired killer from Thailand and the raging young cop who pursues him presents a world in Hobbesian frenzy, with all against all. The most unrelentingly violent Hong Kong film I’ve seen in years, Dog Bite Dog starts with imagery of the killer hiding in the bowels of a ship, scraping up flecks of rice from the floor. After consummating his hit, he moves through a landscape of garbage, hiding out in a landfill and rummaging in a recycle bin for scraps to doctor a girl’s wounded foot. I don’t know any film that insists so intently on the textures of urban offal.

The cop trembles under the pressure of his own torments, and the parallels between the two men climax in a knife fight in a crumbling Thai temple. As is often the case in local cinema, Father is to blame. This visceral movie surely couldn’t be released theatrically in the US. Even the most jaded action aficionado is likely to flinch from certain scenes.

Cheang’s previous film is the suspenseful Love Battlefield. Of Dog Bite Dog he remarked, “I wanted to show [the audience] this Hong Kong film that does not have choreographed action.” For more, see Grady Hendrix’s coverage here and Twitchfilm’s longish review.

Otar Iosseliani’s Gardens in Autumn: The first shot, in which old men quarrel over which one gets to buy a cheap coffin, puts us firmly in Iosseliani’s parallel universe. As often, he speaks for those who just opt out. A minister of agriculture loses his post and drifts among ne’er-do-well pals, hookers, and girlfriends. A film about drinking, eating, smoking, rollerblading, music-making, and middle-aged sex, Gardens in Autumn also satirizes the rich, who are just as lazy as our heroes but waste their lives shopping. There are also prop gags, including the pictures of heifers and boars that show up in quite unexpected places.

Iosseliani casts himself as an easygoing gardener who draws cartoons on a cafe wall. Some of these images recall people and shots we see in the movie, as if we’re watching the old buzzard create the film between swigs of vodka. An elegiac poem to the subversive force of idleness, with a final scene celebrating women.

Over the next couple of weeks, more frequent posts, I hope, including glimpses of this highly photogenic city. For the moment, this from a double-decker bus must suffice.

Homage to Mme. Edelhaus

Why are Americans polarized between francophobia and francophilia? Some people mock the French for liking Jerry Lewis, when most French people probably don’t even know who he is. Others think that France is the repository of world culture and represents the finest in writing about the arts, even though the Parisian intelligentsia can be pretentious and hermetic.

But we must face facts. When it comes to cinephilia, the French have no equals. They grant film a respect that it wins nowhere else. Spend a year, or even a month, in Paris, and you will feel like a Renaissance prince. This is a city where one lonely screen can run tattered prints of One from the Heart and Hellzapoppin!, once a week, indefinitely.

My first trip was too brief, only a week in 1970, but my second one—four weeks of dissertation research in 1973—left me exhausted. Reading Pariscope on the way in from the airport, I learned about a Tex Avery festival. I checked into my hotel and Métro’d to the theatre, where I and a bunch of moms and kids gazed in rapture upon King-Size Canary. Another time, also coming in from the airport, Kristin and I passed a marquee for King Hu’s Raining in the Mountain. Next stop, Raining in the Mountain. My memories of The Naked Spur, Ministry of Fear, Liebelei, Tati’s Traffic, and Vertov’s Stride Soviet! are inextricable from the Parisian venues in which I saw them.

Sound like a lament for days gone by? Nope. You can find the same variety on offer today. Of course the two monthlies, Cahiers du cinéma and Positif, have to take a lot of credit for this. Add Traffic, Cinéma, and several other ambitious journals, and you get a film culture unrivalled in the world.

Critics from Louis Delluc onward have led thousands of readers toward appreciating the seventh art. Historians like Georges Sadoul, Jean Mitry, Laurent Mannoni, Francis Lacassin, and others have enlightened us for decades. Academic film analysis would not be what it is without Raymond Bellour, Noel Burch, Marie-Claire Ropars, Jacques Aumont, and a host of other scholars. Above all stands André Bazin, the greatest theorist-critic we have had.

And the books! Arts-and-sciences publishing receives government subsidies; the French understand that books contribute to the public good. There are plenty of worse ways to spend tax dollars (e.g., trumped-up military invasions). The French, like the Italians, have created an ardent translation culture too. If you can’t read something in Russian or German, there’s a good chance it’s available in French.

I was reminded of the glories of Gallic film publishing when the mailman tottered to my door this week with twenty-two pounds worth of recent items I’d ordered. I haven’t even read them yet; otherwise, they’d be filed with Book Reports. Instead I want to spend today’s blog celebrating them as fruits of an ambition that has no counterpart in English-language publishing. All are grand and gorgeous and informative to boot.

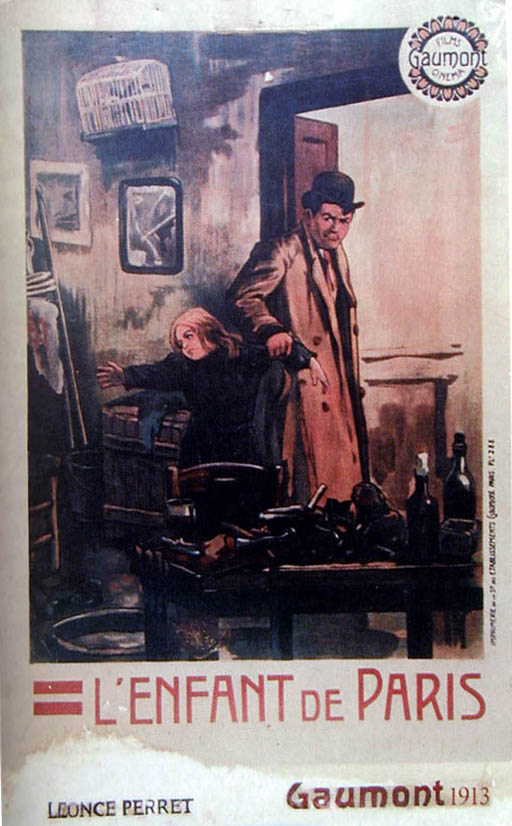

Daniel Taillé, Léonce Perret Cinématographiste. Association Cinémathèque en Deux-Sèvres, 2006. 2.5 lbs.

Daniel Taillé, Léonce Perret Cinématographiste. Association Cinémathèque en Deux-Sèvres, 2006. 2.5 lbs.

A biographical study of a Gaumont director still too little known. Perret was second only to Feuillade at Gaumont, and he performed as a fine comedian as well. His shorts are charming, and his longer works, like L’enfant de Paris (1913), remain remarkable for their complex staging and cutting. After a thriving career in France, Perret came to make films in America, including Twin Pawns (1919), a lively Wilkie Collins adaptation. He returned to France and was directing up to his death in 1935.

Although the text seems a bit cut-and-paste, Taillé has included many lovely posters and letters, along with a detailed filmography, full endnotes, and a vast bibliography. It compares only to that deluxe career survey of the silent films of Raoul Walsh, published by Knopf. . . .Oh, wait, there’s no such book. . . .Think there ever will be?

Il était une fois Walt Disney: Aux sources de l’art des studios Disney. Galéries nationales du Grand Palais, 2006. 4 lbs.

Il était une fois Walt Disney: Aux sources de l’art des studios Disney. Galéries nationales du Grand Palais, 2006. 4 lbs.

A luscious catalogue of an exposition tracing visual sources of Disney’s animation. Illustrated with sketches, concept paintings, and character designs from the Disney archives, this volume shows how much the cartoon studio owed to painting traditions from the Middle Ages onward. It includes articles on the training schools that shaped the studio’s look, on European sources of Disney’s style and iconography, on architecture, on relations with Dalí, and on appropriations by Pop Artists. There’s also a filmography and a valuable biographical dictionary of studio animators.

Some of the affinities seem far-fetched, but after Neil Gabler’s unadventurous biography, a little stretching is welcome. This exhibition (headed to Montreal next month) answers my hopes for serious treatment of the pictorial ambitions of the world’s most powerful cartoon factory. The catalogue is about to appear in English–from a German publisher.

Jean-Pierre Berthomé and François Thomas. Orson Welles au travail. Cahiers du cinéma, 2006. 4 lbs.

Jean-Pierre Berthomé and François Thomas. Orson Welles au travail. Cahiers du cinéma, 2006. 4 lbs.

The authors of a lengthy study of Citizen Kane now take us through the production process of each of Welles’ works. They have stuffed their book with script excerpts, storyboards, charts, timelines, and uncommon production stills.

The text, on my cursory sampling, will seem largely familiar to Welles aficionados; the frames from the actual films betray their DVD origins; and I would like to have seen more depth on certain stylistic matters. (The authors’ account of the pre-Kane Hollywood style, for instance, is oversimplified.) Yet the sheer luxury of the presentation overwhelms my reservations. A colossal filmmaker, in several senses, deserves a colossal book like this.

Alain Bergala. Godard au travail: Les années 60. Cahiers du cinéma. 2006. 5 lbs.

Alain Bergala. Godard au travail: Les années 60. Cahiers du cinéma. 2006. 5 lbs.

In the same series as the Welles volume, even more imposing. If you want to know the shooting schedule for Alphaville or check the retake report for La Chinoise (these are eminently reasonable desires), here is the place to look. Detailed background on the production of every 1960s Godard movie, with many discussions of the creative choices at each stage. Once more, stunningly mounted, with lots of color to show off posters and production stills.

Anybody who thinks that Godard just made it up as he went along will be surprised to find a great degree of detailed planning. (After all, the guy is Swiss.) Yet the scripts leave plenty of room to wiggle. “The first shot of this sequence,” begins one scene of the Contempt screenplay, “is also the last shot of the previous sequence.” Soon we learn that “This sequence will last around 20-30 minutes. It’s difficult to recount what happens exactly and chronologically.”

Emrik Gouneau and Léonard Amara. Encyclopédie du cinéma du Hong Kong. Les Belles Lettres, 2006. 6.5 lbs.

Emrik Gouneau and Léonard Amara. Encyclopédie du cinéma du Hong Kong. Les Belles Lettres, 2006. 6.5 lbs.

The avoirdupois champ of my batch. The French were early admirers of modern Hong Kong cinema, but their reference works lagged behind those of Italy, Germany, and the US. (Most notable of the last is John Charles’ Hong Kong Filmography, 1977-1997.) More recently the French have weighed in, literally. 2005 gave us Christophe Genet’s Encyclopédie du cinéma d’arts martiaux, a substantial (2 lbs.) list of films and personalities, with plots, credits, and French release dates.

Newer and niftier, the Gouneau/ Amara volume covers much more than martial arts, and so it strikes my tabletop like a Shaolin monk’s fist. There are lovely posters in color and plenty of photos of actors that help you identify recurring bit players. Yet this is more than a pretty coffee-table book. It offers genre analysis, history, critical commentary, biographical entries, surveys of music, comments on television production, and much more. It has abbreviated lists of terms and top box-office titles, as well as a surprisingly detailed chronology.

Above all—and worth the 62-euro price tag in itself—the volume provides a chronological list of all domestically made films released in the colony from 1913 to 2006! Running to over 200 big-format pages, the list enters films by their English titles and it indicates language (Mandarin, Cantonese, or other), release date, director, genre, and major stars. Until the Hong Kong Film Archive completes its vast filmography of local productions, this will remain indispensable for all researchers.

Above all—and worth the 62-euro price tag in itself—the volume provides a chronological list of all domestically made films released in the colony from 1913 to 2006! Running to over 200 big-format pages, the list enters films by their English titles and it indicates language (Mandarin, Cantonese, or other), release date, director, genre, and major stars. Until the Hong Kong Film Archive completes its vast filmography of local productions, this will remain indispensable for all researchers.

Mme. Edelhaus was my high school French teacher. A stout lady always in a black dress, she looked like the dowager at the piano during the danse macabre of Rules of the Game. She was mysterious. She occasionally let slip what it was like to live under Nazi occupation, telling us how German soldiers seeded parks and playgrounds with explosives before they left Paris. When I asked her what avant-garde meant, she replied that it was the artistic force that led into unknown regions and invited others to follow–pause–“in the unlikely event that they will choose to do so.”

For three years Mme. Edelhaus suffered my execrable pronunciation. When I tried to make light of my bungling, she would ask, “Dah-veed, why must you always play the fool?”

I suppose I’m still at it. But thanks largely to her I’m able to read these books as well as look at them. She opened a path that’s still providing me vistas onto the splendors of cinema.

Vancouver envoi

A late night Thursday, and a snoozy day of traveling on Friday, kept me from posting ASAP. And now on Saturday morning—I can’t get on to my own blogsite! Apparently others can. So while our web czarina Meg fixes things, I try to wrap things up on my visit to the Vancouver International Film Festival.

Le Petit Lieutenant: A policeman’s lot is never a happy one. From Ed McBain’s 87th Precinct to Ian Rankin’s Rebus series, modern crime novels give an emotional resonance to police procedure by showing the psychological costs of being exposed to cruelty, chicanery, and death. American cop movies have gradually let more of this quality come through (Prince of the City, Heat, Dark Blue), and of course TV, from Hill Street Blues to The Wire, has turned the police procedural into urban melodrama. But the French got here first. For decades, their cop movies have been world-weary psychological dramas shot through with bitter realism. Think of Corneau’s Police Python 357, Pialat’s Police, Tavernier’s L.627, or any of Melville’s policiers.

Le Petit Lieutenant, which I saw on my last day, falls into that sturdy tradition. The premise—a string of attempted murders of bums and passersby—is played out with the usual clue-by-clue plotting, but we also witness the strained lives cops lead. Our two protagonists are the overeager recruit Antoine (Jalil Lespert) and his recovering alcoholic supervisor Carolina (Nathalie Baye in an utterly deglamorized performance). Xavier Beauvoi’s narration shuttles skillfully between their points of view, leading to a good deal of sympathy and suspense and a grim but plausible climax. One of several nice touches: the cops keep movie posters over their desks, and if I’m not mistaken, in some cases the posters serve as hints to the cops’ personalities. The ending leaves you as bereft of certainty as the protagonist.

Do Over (Taiwan): For a finale, I caught this extraordinarily ambitious movie by the twenty-eight-year-old Cheng Yu-chieh. Shot in anamorphic widescreen (very rare in Taiwan over the last twenty years), it belongs to the trend I’ve called “network narratives.” Across New Year’s Eve and New Year’s Day, the lives of several people converge and diverge in the fashion of Short Cuts and Magnolia. Each character’s strand evokes a different genre: gangster movie, romantic drama, twentysomething “relationship” comedy, and the movie about moviemaking. Each strand is also set off by a distinctive photographic style, from misty blue to grainy, blown-out noir.

A network plot often exhibits an interesting mix of realism (in life, strangers’ lives do become tangled) and artifice (chaptering, repeated scenes, and other overt narrational devices). The artifice becomes flagrant at the film’s end, when Do Over‘s title gets literalized and the plot lines are revised to yield alternative endings. The cleverness doesn’t get the upper hand, however, and this remarkable debut leaves you both satisfied and looking forward to Cheng’s next film.

After two trips to Vancouver’s festival, I have yet to go to any tourist destination. I’ve lived within a few square blocks, dashing among hotel, DVD stores, and the Granville Multiplex, with forays to the Pacific Cinematheque and the Vancity Theatre and sushi restaurants and crepe cafes. I’ve lived a film-wonk holiday across eight days and dozens of movies. Thanks to Alan Franey, the Festival Director, for inviting me and extending me so much courtesy. I’m grateful to all the help of his colleagues PoChu Au-yeung, Mark Peranson, Eunhee Cha, Steve Martindale, and Jack Vermee. I wish we’d had more time to talk! Over the last two visits, I’ve made new friends from all over the world, and I’ve enjoyed just sitting among exuberant audiences.

Tony Rayns has been programming Asian films at Vancouver since 1988, and I have to note the melancholy news that he’s stepping down as coordinator of the Dragons and Tigers competition. I’m unhappy as well that I can’t be at Vancouver tonight (Saturday) to see the results of the competition and participate in what will surely be a string of tributes to Tony. So here’s a weak substitute—my own appreciation online.

Tony Rayns at VIFF, 2006

In Tony Rayns deep expertise is joined to an unmatched passion and curiosity. His Vancouver programming was crucial in introducing directors like Kitano and Hou to West. He has also made films happen: Without the acclaim of Vancouver audiences and the prestige of the Dragons and Tigers prize, how many distributors would have backed later work by young directors over the last twenty years?Most critics prefer to stroll into screenings to watch films that miraculously appear, thanks to the work of dozens laboring behind the scenes. From the start Tony got his hands dirty. Apart from writing discerning and literate film criticism, he worked for film festivals, wrote presskits and program notes, translated subtitles, and pushed for offbeat films to be available on video and cable. Above all, he programmed films, backing his tastes with an expanding network of allies in the film industry. He helped create a climate of opinion that welcomed the burst of creative accomplishment that Asian film has offered over the last three decades.

Tony’s been a friend since the mid-1970s, and his influence on my tastes and thinking has been immense. I wouldn’t know a lot of what I know without his tireless proselytizing for once-obscure films and filmmakers. He’s sensitive to all a film’s dimensions—its social and artistic implications, its relation to the director’s personality and life experience. A late-night conversation with him, preferably over Asian food, is like being in the liveliest seminar you ever took.

Many of Tony’s contemporaries—I know plenty—have given up on contemporary cinema. Who can blame them, after a trip to a multiplex? Too often, cinema seems over. But this has only made Tony dig deeper, watch more widely, and remind us that this art form is still frisky, unpredictable, and occasionally rapturous. The French have a word for it: animateur, the person who sends a jolt of energy into a culture. Like André Bazin and Henri Langlois, Tony is one of the animateurs of world cinema, and everyone who loves film is in his debt.