Archive for the 'National cinemas: France' Category

The ten best films of … 1931

M (1931)

Kristin here:

Our regular readers know that this annual series began as a simple salute to 1917, the year in which the basic norms of the classical Hollywood cinema definitively gelled. Starting in 2008, it became the “The 10 best films of …” list. It has stood in for the year-end ten-best lists which critics and reviewers feel obligated to concoct but which we avoid.

1931, I think, was a slight improvement on the rather lackluster 1930. A small handful of filmmakers mastered the “talkies” and made movies that look and sound as if they could have been made years later. These are the first four films below. It was a little harder to fill in the list beyond them. It’s is full of familiar classics, with a film or two that will probably unknown to many. I always try to include at least one worthy out-of-the-way title.

Previous entries can be found here: 1917, 1918, 1919, 1920, 1921, 1922, 1923, 1924, 1925, 1926, 1927, 1928, 1929, and 1930

M

I remember seeing M as a grad student, or maybe even an undergraduate, and being horribly disappointed. This was a masterpiece? Actually it was only a semblance of one. In the 1970s a poor, incomplete 16mm print with as sparse a set of subtitles as I think I’ve ever seen was in circulation. The wit and brilliance of Fritz Lang’s sound links and voiceovers were largely lost, as were the sharp images now evident in the restored version. Even restored, as the introductory titles tell us, it is missing 212 meters. Fortunately that’s only .4% of the total, and the narrative progression is so smooth and absorbing that it’s hard to imagine that anything could be missing.

The story concerns a child-murderer terrorizing a city and the parallel searches for him by the police and by the organized underworld, the activities of which are being hindered by constant police searches and raids. At one point Lang famously intercuts a meeting of city officials with one of a group of gangsters. Parallels are created by matched gestures between space but also by one line being started by a character at one meeting and picked up by one at the other. Lang races through exposition by having the voiceover of a phone conversation between officials continuing over shots of the investigation in various spaces.

He uses sonic motifs as well. The killer compulsively whistled a Grieg tune as he lures his victims, but whistles come back time and again. Police whistles signal the raid on a basement tavern, and the beggars who tail their suspect signal each other with whistles–heard by the killer, who flees into an empty office building and ends up trapped there (top).

There’s a lot of offscreen sound in this film. The raid on the tavern cuts around to various parts of the space, as when we briefly follow a crook who tries to sneak out (above) while the protests of the crowd and the whistles and shouts of the police are heard off. One might think that all this is to avoid having to lip-sync the sound with the characters speaking–but when he does show the speaker, the sync is perfect. It’s another instance, I think, of Lang using sound to cram a lot of action or information into a short stretch of time. The thwarted crook is just a bit of comic relief, something Lang injects at intervals into this grim narrative.

Back in 2012, when I participated in Sight & Sound‘s poll of critics and academics for the ten best films of all time, I put M on the list. Counting 2021, it is the third film from that list that I have included in this one: The General in 2016, The Passion of Joan of Arc in 2018, and now M. The next one won’t show up for eight years (hint: Renoir made it in 1939), assuming I’m still doing this list at that point.

If you’ve never seen M, make sure you don’t watch an older print! The restored version is on Blu-ray from The Criterion Collection in the US and Eureka! in the UK.

Le Million

René Clair made two film classics in 1931, À nous la liberté and Le Million. I find the latter a better film in that it’s more complex and lively. À nous la liberté, which focuses on only two characters who spend a stretch of the film apart, has a rather thin narrative. Le Million, on the other hand, involves a large cast of amusing characters and constantly bubbles with dances, chases, and farcical situations. Indeed, early on it cites the chase scenes of early cinema when police pursue the kindly thief, Père Tulip, over the rooftops.

The sets were created by the great French film designer, Lazare Meerson (who also did the more austere sets of À nous la liberté). The interiors often have soft, hazy backgrounds (top of this section) apparently done partly by painting and partly with real objects behind scrims. These give a stylized quality appropriate to a classic farce situation: the debt-ridden artist protagonist Michel frantically searches for a jacket holding a winning lottery ticket as the jacket goes from hand to hand. At one point crossing hallways permit two chases–the police after Tulip, the creditors after Michel–to pass through each other.

David and I taught Le Million in an introductory film class back in the 1970s. I hadn’t seen it since, but it lived up to my fond memories of it. As cheerful a film as one could find for what promises to be another year short on cheerfulness.

Le Million is available on DVD from The Criterion Collection. The description says that the lyrics are all translated here for the first time.

Arrowsmith

Early as it is, Arrowsmith is surely one of Fords’s great films of the 1930s. It’s an adaptation of Sinclair Lewis’ 1925 novel of the same name. (Lewis won a Pulitzer for it but refused to accept the award.) The plot centers around Martin Arrowsmith (Ronald Colman), who starts as a medical student eager to establish a reputation and help discover cures for various plagues. He marries a charmingly impertinent nurse Leora (Helen Hayes), who supports him in his efforts.

The style of the film is distinctly flashy in its lighting, depth shots, and set design. It looks like what we tend to think of as Wellesian–though many of these techniques could instead by dubbed Fordian.

There are dramatic chiaroscuro effects as when Arrowsmith arrives home one evening, discouraged, and Leora sympathizes with him. The figures are side-lit with illumination coming from the kitchen, and Arrowsmith becomes a silhouette once he sits down.

The depth shots are equally impressive. A spectacular high angle (top of this section) shows three levels of a ship’s interior, with Sondelius, a medical expert, shouting up to the captain that he has discovered bubonic plague onboard. A less flashy but highly intense shot shows Leora’s death from bubonic plague. The long take is filmed with what David terms “aperture framing,” with Leora placed far off-center and relatively far from the camera, framed in the arms of the foreground rocking chair. It’s the same chair in which she sat when she smoked a cigarette contaminated with one of her husband’s plague samples. It’s a brilliant way to emphasize that she dies alone, with the bright open door at the center of converging lines of the set stressing that her husband does not suddenly appear, as we might expect, to comfort her.

Other more casual uses of depth with prominent foregrounds include a shot of Arrowsmith exiting his laboratory with beakers, bottles, and other equipment dwarfing him (below right).

Note also the prominent ceiling on the sets in the image on the left above. The notion that Citizen Kane was the first Hollywood film to use ceilings on sets has long been discredited, and here’s a good example of why. In general, Richard Day’s art direction combines with the cinematography to create powerful images, as in the hallway of the McGurk Institute, where Arrowsmith gains a research post.

We know that Welles was influenced by Ford’s work, but he primarily stresses Stagecoach as a film he watched repeatedly before making Citizen Kane. Arrowsmith, however, actually looks more like Kane than Stagecoach does. Did Welles and/or Gregg Toland see it? Very likely at least one of them did. There seems to be no record of Welles having said he saw it, but in 1938 he wrote and performed the title role in a radio version of Arrowsmith that had Hayes repeating her role as Leora.

Moreover, Arrowsmith was produced by Samuel Goldwyn. In the late 1920s and early 1930s, Toland was making films there, including Eddie Cantor comedies (Whoopee!, 1930) and two crime dramas starring Colman (Bulldog Drummond, 1929, and Raffles, 1930). It seems implausible that he would not have seen Arrowsmith.

All this is not to say that Arrowsmith was the first film to play with depth and chiaroscuro. As David pointed out in a 2010 blog entry, such ideas were developing in Hollywood during the 1920s, and William Cameron Menzies in particular experimented with them. There David wrote, “The flashy depth compositions of the 1920s and 1930s were typically one-off effects, used to heighten a particular moment.” True enough, but I think Arrowsmith uses them more consistently.

So far Arrowsmith has not been released on Blu-ray, but the MGM DVD has surprisingly good visual quality for a film from this period. (Amazingly enough, you can still buy new VHS copies on Amazon.)

Kameradschaft

Like Clair, G. W. Pabst directed two classic films in 1931, Kameradschaft (“Comradeship”) and The Threepenny Opera. The former is a network narrative, cutting among several characters or small groups of characters as they react to a mine disaster.

The story is set in two villages on either side of a French-German border. Each is a mining town, exploiting what is actually the same rambling mine that has walls and bars in multiple tunnels marking the end of the German portion and the beginning of the French one. When escaping gas triggers a fire and ceiling collapses on the French side, two truckloads of German miners volunteer to go and help the rescue teams.

As the title suggests, the film stresses the theme of solidarity among the miners, though Pabst doesn’t paint an entirely rosy picture of this. The German miners coming off their shift argue about whether they should assist their French counterparts, and many declare that it’s none of their business. Pabst stages the debate in a visually interesting locale, the changing room where the mining outfits of the men are stored on ropes or wires up by the ceiling (above and below, left). The leader of the group which goes to help with the rescue is played by Ernst Busch, a well-known Communist actor-singer who was also in the original stage version of The Threepenny Opera and Pabst’s adaptation, as well as Slatan Dudow’s Kuhle Wampe (1932), from Brecht’s script. His presence as one of the main characters in the network plot–and the one who spurs others to volunteer as rescuers–helps give Kameradschaft a distinctly leftist tone.

As with many other films set in coal mines, the mine itself was an elaborate and convincing studio set (above right). One collapsing area of a mine looks much like another, but Pabst found ways to vary the action from scene to scene. Variety is added through a contrast in the main characters being followed. An old ex-miner sneaks into the mine to search for his grandson. Three German miners who didn’t go in the trucks to the French side decide to make a rescue effort on their own, breaking through the barred underground border to do so. They end up alongside the old miner and his grandson, trapped in the underground stable, where the presence of a placid but doomed horse adds a poignancy to the scene. At intervals the drama going on among the mothers, wives, and sweethearts of the French miners clustered at the gates is shown.

The weaving together of the various threads of action creates a strong sense of suspense. No one character can be singled out as the protagonist, the one who might be expected to survive. Some miners and rescuers escape, but there are many who die or suffer serious injuries.

Despite the emphasis on the comradeship of miner of both nationalities, the Germans definitely come off better. Their rescue team is well-equipped and efficient, while the French workers deal with problems like an elevator being out of commission. It probably would never have occurred to Pabst and the others involved to make a film where French miners help rescue German ones–and it probably would not have been greenlit by the production company if they had. On the level of the individual miners’ actions, however, the notion of working-class solidarity comes across.

Kameradschaft is available on DVD and Blu-ray from The Criterion Collection.

Tabu: A Story of the South Seas

Tabu was Murnau’s final film. (The opening scene of the hero fishing with his friends was shot by intended co-director Robert Flaherty, who soon quit due to disagreements with Murnau.) It deals with Matahi and Reri, who live a joyful life on unspoiled Bora Bora until an elderly man from a nearby island arrives and announces that the “Virgin sacred to our gods” has died, and Reri is to be her successor. Matahi rescues her, and the two flee to another island which has been colonized by the French. They have established a pearl fishery and hire local men to dive for pearls. Matahi proves expert at this, but not understanding what money is, he soon gets himself deep into debt by signing IOUs.

Rather than using Hollywood stars, Murnau cast local unprofessionals. As the credits announce, “only native-born South Sea islanders appear in this picture with a few half-castes and Chinese.”

The two leads are appealing characters, and the images take advantage of the unspoiled scenery of Bora Bora (below left). Floyd Crosby earned an Oscar for Tabu‘s cinematography.

Tabu is a far cry from Murnau’s German films, but Nosfertu‘s famous shot of the vampire’s ship sailing eerily into the frame from offscreen is echoed as a motif here (below right).

The original version released by Paramount was released on DVD by Milestone. A restoration of the original cut of the film is available on DVD and Blu-ray from Kino Classics in the US and Eureka! in the UK, both with numerous supplements. A helpful comparison of these versions is available here.

La Chienne

I think it is safe to say that most critics and historians consider La Chienne the film where Renoir’s distinctive traits as a director began to emerge. I have seen most of the early Renoirs, but long enough ago that I can’t make a comparison. It does seem to me, though, that it is quite different from his previous work.

Maurice Legrand, the protagonist played by Michel Simon, is the most Renoirian character. He is a mild-mannered accountant married to a termagant who nags him constantly and forces him to remove from their apartment the paintings and the equipment he uses for his hobby. This sets off the events which follow, as Legrand hangs the paintings in the apartment of a prostitute, Lulu, with whom he has fallen in love. Her pimp Dédé concocts a scheme to sell the paintings, which he passes off to a dealer as the product of an American painter named Clara Wood. Even when Lulu explains what happened to the paintings, Legrand is so besotted that he raises no objections.

Although “la chienne” of the title is clearly Lulu, it might refer to Adèle Legrand as well. “Chienne” is more-or-less the equivalent of the English “bitch,” meaning both a female dog and an obnoxious woman, which Adèle certainly is. In their first scene together, she berates Legrand at length, comparing him unfavorably with her first husband, whose portrait in military uniform looms over them (above). Legrand does not rebel but answers in quiet sarcastic comments and ultimately obeys her order about the paintings.

In French, “la chienne” has the additional meaning of a prostitute, clearly referring to Lulu. Legrand is trapped between a constantly angry wife and a prostitute skilled in behaving in a docile fashion, pretending, as she finally admits, to love him solely in order to maintain the flow of money from the paintings. This admission finally drives him to fight back, killing Lulu. He ends up as a jovial tramp, foreshadowing Simon’s later role as Boudu in what is arguably Renoir’s first true masterpiece.

Stylistically the film does not strongly resemble Renoir’s major films of the mid- to late 1930s. Still, the scene in which Dédé and his friend approach an art dealer in their first attempt to sell one of Legrand’s paintings consists of a longish take of nearly two minutes, with staging in depth (below) when the dealer returns from a search and a track-in to a closer framing for the negotiations. Also, the film starts as a puppet show, with puppets introducing the main characters, whose images are superimposed over the little stage (bottom). This looks far forward to his final film, The Little Theatre of Jean Renoir (1970).

La Chienne is available on Blu-ray and DVD from The Criterion Collection.

Tokyo Chorus

Last year Yasujiro Ozu made his first appearance on this list for That Night’s Wife. This year it’s Tokyo Chorus (or Chorus of Tokyo). With sound barely established in Japan, Ozu made this and several subsequent films silent.

As the Criterion Collection liner notes explain, Tokyo Chorus combines the three genres Ozu had worked in before: the student comedy, the salaryman film, and the domestic drama. The student comedy subject gets disposed of early on, with the first scene showing the a comically strict teacher scrutinizing his class, lined up military-style; the protagonist, Shinji, tries some mild defiance by being late and showing off (below left).

Soon he has graduated, though, and is working in an office where the employees are awaiting their year-end bonuses. Just as quickly, Shinji is fired for protesting when an elderly colleague is fired just before his retirement and pension payments.

The rest of the film seems like a practice piece for I Was Born, But … (1932) and other Ozu films involving bratty kids who make demands on their parents. In this case Shinji’s son insists that his father buy him a bicycle and pesters him until he finally gets it (above right). As in the later film, Shinji is humiliated by having to take a job helping his old teacher to publicize his curry cafe.

Ozu’s growing mastery of editing for comedy is shown off in the early scene when the office employees try to find out how big a bonus their colleagues have received. Shinji sneaks away to the restroom to open his envelope, pretending he has gone to use a urinal. A low-height shot shows another man coming in, with the swinging doors of the urinal area showing him only from the waist down. Shinji, just about to open his envelope, glances off and sees him. A reverse shot shows the colleague stopping and staring, clearly more interested in Shinji’s bonus than in using the urinals. Shinji gives up, pretends he is just there to relieve himself, and a final shot shows him departing still not knowing how big his bonus is.

By this point, Ozu has mastered balancing comedy and pathos, a mixture of tones that will reappear in many of his future masterpieces.

Tokyo Chorus is has been released on DVD, appropriately enough along with two of those future masterpieces, I Was Born, But … and Passing Fancy (1933), by The Criterion Collection.

City Lights

I must admit that I do not admire City Lights as much as The Gold Rush and The Circus, which featured in my ten-best lists of 1925 and 1928. I think it has some narrative problems.

For one thing, the blind flower seller as a love interest is pretty passive and doesn’t allow many opportunities for generating humor. In The Gold Rush, Chaplin had the inspiration to introduce a dream sequence about the dance-hall girls, including his beloved Georgia, coming to dinner with him. He then inserted his classic gag, the dance of the rolls. Much of the action in The Circus involves the heroine, as with the magic act into which the Tramp stumbles. The flower seller mainly generates pathos, right up to the ambiguous ending. (I have seen commentators take the ending as a clear indication of a budding romance between the pair, but I think we get no clear indication that her gratitude for the help the Tramp has provided will blossom into love.)

Chaplin needed to fill out the film with action beyond the few scenes involving the flower seller. Much of the action involves the Tramp’s on-again, off-again friendship with the eccentric millionaire, which is a weak premise to carry so much of the narrative. This character treats the Tramp as his closest buddy when drunk but then fails to recognize him when sober. This happens three separate times and gets a bit repetitious in a way not seen in other Chaplin films. The main contributions of the millionaire to the plot are to give the flower seller the impression that the Tramp who buys her flowers is a wealthy man and to give the Tramp the money for the flower seller’s eye-restoring treatment. The character of the millionaire does create some humorous bits, as when the pair eat spaghetti and the Tramp gets a curly streamer mixed in with his and keeps on eating it. I can’t help contrasting the millionaire with the Mack Swain character in The Gold Rush, whose interactions with the Tramp generate so many hilarious gags.

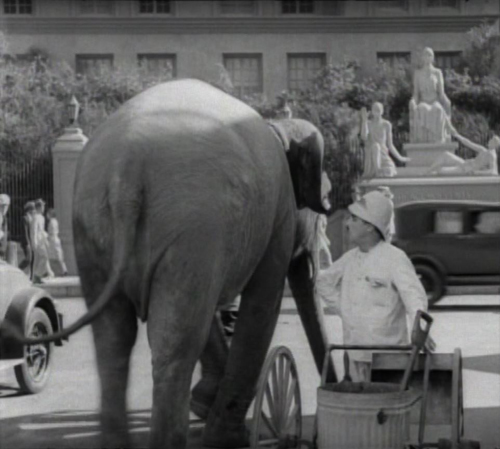

There are admittedly other funny scenes, especially early on, when the Tramp is discovered asleep on the lap of a statue being unveiled before a crowd or when he becomes a street cleaner to earn money for the flower seller and is immediately confronted with a group of horses and, as a topper, an elephant passes.

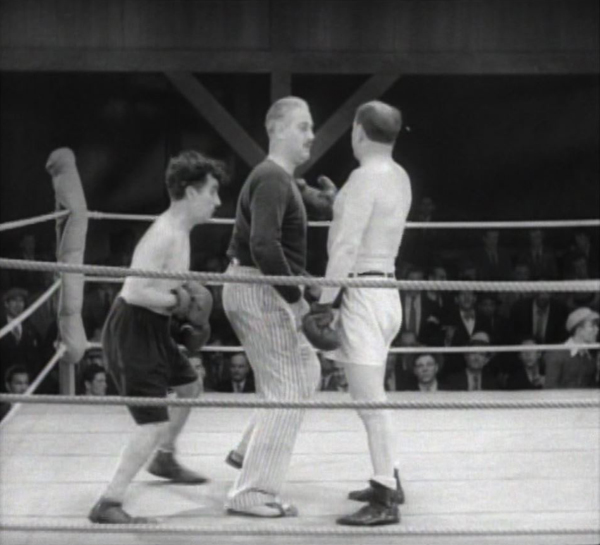

Later on in the film, though, the plot premise of earning money to help the flower seller have an operation to restore her sight generates one of the funniest scenes in all of Chaplin’s work. He agrees to participate in a fixed boxing match, with his opponent going easy on him and the two splitting the purse. The opponent is replaced by a tough guy who clearly has no intention of playing nice. The Tramp’s tactics to avoid being beaten up involve dancing around directly behind the referee at first (top of this section) and then, in a dazzling bit of choreography, the three figures move around the ring, changing places repeatedly so that the Tramp is sometimes behind the referee, sometimes behind his opponent, and so on. It is reminiscent of the scenes in the hall of mirrors as the Tramp is chased by a pickpocket and then by a policeman in The Circus, with the characters and their reflections dodging in and out of view.

Chaplin famously refused to allow spoken dialogue in his film, despite the fact that the transition to sound was well established in the USA by 1931. He restricted the track to music and sound effects, a tactic he carried over to Modern Times as late as 1936, though there the Tramp’s voice is heard for the first and last time singing a nonsense song. Chaplin retired his long-time character thereafter.

City Lights is available on DVD and Blu-ray from The Criterion Collection.

Odna (Alone)

When I was in graduate school, the only film by Grigori Kozintsev and Leonid Trauberg widely known outside the Soviet Union was their 1926 adaptation of The Cloak, which appeared in my best-ten list for that year. Then people discovered, to some extent, The New Babylon, which appeared in the entry for 1929. I suspect that few people have seen, or even heard of, their marvelous first sound film, Odna.

It was planned as a silent film, but delays permitted the use of sound technology to add a track to it. The main element of the track is Dimitri Shostakovich’s musical accompaniment. (He had also composed the musical accompaniment for The New Babylon.) The music comments on the action, often in a mocking way. Occasionally there are sound effects, and very occasionally, brief lines of dialogue, recorded and added after the filming.

The plot centers around a young teacher fresh out of school, Yelena Kuzmina (played by Yelena Kuzmina, who also played the protagonist of The New Babylon).

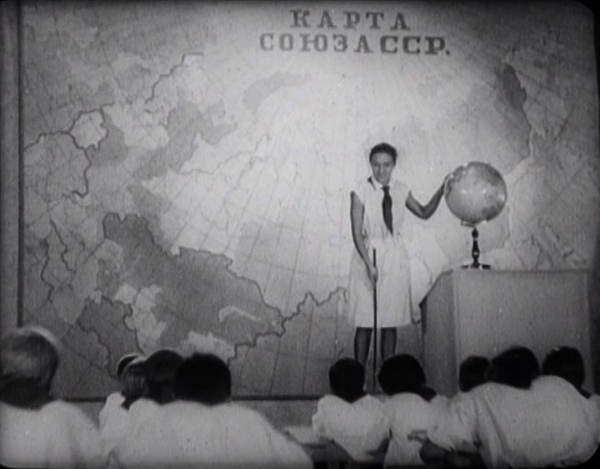

The first section of the film is played with an absurdly jolly exuberance. Yelena is engaged to a handsome young man, and a lively montage of shots shows her visions of the ideal life she plans to lead with him in Moscow, including window-shopping for expensive sets of dinner crockery, playing a musical duet at a cafe (below left), and teaching attentive children seated in neat rows in a well-equipped classroom (top of section). Shostakovich’s music is ridiculously cheerful, and a song about how beautiful life will be plays over a shot of Kuzmina’s fatuous grin (below right).

The tone switches abruptly as Kuzmina receives an assignment to a teaching post in a remote, mountainous primitive district of Siberia.

Devastated, she lodges a complaint, which seems likely to succeed. An elderly man in the office tells her that she’s right to try to change her assignment (below left). She erupts, “I’m going anyway!” This is one of the few post-dubbed lines.

Upon arrival in the Siberian district, she encounters a dead horse’s skin on display (below right); this returns as a motif to emphasize how primitive and in need of education the area is. At first the villagers react with indifference or antagonism, seeing no point in having their children go to school. Oddly enough, the local Soviet official is lazy and also indifferent, leaving her alone with no aid in convincing the villagers to accept her. (This negative depiction of the Soviet official later got the film banned, despite its considerable popularity upon its initial release.)

Apart from encouraging teachers to accept whatever school they were assigned to, the film has the anti-Kulak theme that was common in Soviet films about the countryside. (See the discussion of Eisenstein’s The General Line in the 1929 entry.) A wealthy local landowner has secretly sold off the sheep that technically belong in common to the villagers, whose main source of income is the wool. Kuzmina exposes the theft and helps the local people resist it, thus finally gaining their trust.

The next-to-last reel of the film, in which the landowner tries to kill Kuzmina, is missing. A restored version of the film accompanied by a reconstruction of the Shostakovich score was released on Dutch and German DVDs in 2007. (The frames here are from the Dutch DVD.) It includes a long series of intertitles describing action in the missing reel, drawn-out so as to match the length of the music, which does survive. As far as I can tell, these DVDs are no longer available. I am reluctant to recommend a version on YouTube, derived from the German DVD and superimposing English subtitles on German ones, on top of Russian intertitles. It does seem to be the only widely available way to see the film at this point, so for those who can put up with the clutter and the poor quality of the online version, it is here. A complete recording of the charming music is still available.

La Petite Lise (1930)

My tenth film is a holdover from last year. I consider Jean Grémillon’s La petite Lise a film worthy of the top-ten list, but when compiling last year’s list I somehow misremembered it as being from 1931. It just goes to show that one should double-check on such things.

Decades ago, I first saw La petite Lise in a 35mm print on an editing table at the Cinémathèque Royale de Belgique (now the Cinematek). I finally saw it on the big screen in 2015, when our UW Cinematheque ran a few Grémillon films in 35mm. Then-graduate student Jonah Horwitz provided the program notes.

Grémillon is best known outside France for the trio of films he made during World War II: Remorques (1941), Lumière d’été (1943), and La ciel est à vous (1944). Criterion has released a box set of all three as Jean Grémillon During the Occupation. Some of his other films are available on disc, as a search of the director’s name on Amazon.com or amazon.fr reveals (including some with English subtitles).

The simple plot involves Berthier, who is serving a long sentence in a prison in Cayenne for having killed his wife in a fit of jealousy. Heroic behavior on his part during a recent fire has led to an early release, and he expresses his desire to see his daughter, Lise, now grown up. All this sets us up to be sympathetic toward him, despite the fact that he is played by by Pierre Alcover, a large, rather sinister looking actor. (Best known to modern audiences, I suppose, as the corrupt banker in L’Herbier’s L’Argent.) Unbeknown to him, Lise has been working as a prostitute but has now ended that in anticipation of marrying André. The pair are in desperate need of obtaining 3,000 F within 48 hours to buy a small house.

Berthier’s reunion with Lise is joyful, and he manages to find a job with his old boss, who gives him a generous advance on his salary. Knowing nothing of this, Lise and André visit a Jewish pawnbroker who André believes has cheated him in the past. When he threatens the pawnbroker, a fight breaks out, and Lise accidentally kills the man. Berthier learns of her past and of the killing, and his great love for her leads him to turn himself in as the killer.

The story is quite touching, in large part because Alcover and Nadia Sibirskaïa (who played the younger girl in Menilmontant) convey the deep love between the pair.

Grémillon adds some unconventional touches which have little direct relation to the plot and are largely dependent on sound. These give the simple plot some variety.

The opening, for example, takes place in the Cayenne prison, with Berthier learning of his pardon from the warden. In the crowded dorm, he reveals to two fellow convicts that his good fortune makes it impossible for him to participate in a planned escape. He shows them a photograph of Lise as a child. Most of the extended dorm scene, however, consists of fairly tight shots of other men’s activities, all packed into the crowded room. The soundtrack, rather than catching scraps of dialogue, remains a loud babble of many men talking at once. These shots tell us us next to nothing about the narrative, beyond suggesting the grim conditions to which Berthier faces returning to at the end. It does, however, create an effective atmosphere of the prison as a backdrop to occasional shots of Berthier gazing at the photo of Lise.

Another example is a scene late in the film, when, having learned of the killing, Berthier goes looking for André. He tries to enter a nightclub, but it is too crowded. He stands watching with several others through the window as a Black dancer performs a lively number for a mixed Black and white audience. For a brief interval, the scene becomes a musical number, extending to the point where couples start dancing, with Berthier becoming quite peripheral to the action. The performer and dancers add nothing to the story, but the scene is delightful in itself.

These and other moments draw us away from the linear progression of the story and make La petite Lise one of those small, simple films that transcend their apparently modest nature–like those of Jean Epstein and Dimitri Kirsanoff.

La petite Lise remains difficult to see. It has never, as far as I know, been available on home video. Grémillon’s film is not on YouTube, but there are several clips from key scenes. (All are pretty poor in quality, and I haven’t seen a good print of it. If elements survive in archive, it seems a major candidate for restoration.) An excerpt from the scene in the prisoners’ dorm near the beginning gives a good sense of the babble of voices. The Black dancer’s number as Berthier searches for André is shown nearly in its entirety. Both of these were put up at the time of the Cinematheque screening in Madison. There are some other brief scenes: the visit to the pawnbroker leading up to the murder, the scene of Berthier applying to his former boss for a job (which includes a sound bridge from the previous scene of Lise at home), and the scene in a restaurant which Lise and André visit in the hope of establishing an alibi. Otherwise, keep an eye open for it if you live near at archive that has public screenings.

For a look at Ford’s flashy style in his earliest features, see here. For a defense of How Green Was My Valley‘s Oscar win over Citizen Kane for best picture, see here.

My video essay, “Mastering a New Medium: Sound in M“ is number 11 in the series “Observations on Film Art” on The Criterion Channel.

La Chienne (1931)

French silents from Il Cinema Ritrovato 2021

L’Arlésienne (1922)

Kristin here:

Like so many of our fellow festival-goers, David and I were not able to visit Bologna for Il Cinema Ritrovato, the annual festival of restored films and curated thematic threads. Fortunately the organizers made a selection of the films and events (interviews, discussions of films by archivists) available online.

We were not able to watch all of these, so we concentrated on an area in which we have both worked, French silent cinema. There were three of these, or six if you count the four episodes of the 1927 serial, Belphégor. They were beautiful restorations, all presented in black and white. (I must admit, beautiful though tinted and/or toned films are, I prefer the black-and-white versions. That’s mainly because if one is taking frame enlargements for reproduction in black and white in a publication, it is often impossible to get a decent copy from a tinted print.)

No doubt it is frustrating to read about films that are unavailable to see outside archives. Still, some of the Cinema Ritrovato films travel after their presentations at the festival, and some appear on DVD/Blu-ray. These are three to keep an eye open for.

L’Arlésienne

I must admit, this was the only title of the three that I recognized. David and I had been very impressed by André Antoine’s earlier films. (See our brief comments on and some frames from his extraordinary 1917 Le coupable here and here.)

While Le coupable was a courtroom melodrama set in Paris, L’Arlésienne follows his 1921 naturalistic film La terre by being shot in the French countryside. In this case the story takes place in and around Arles, at that time a village in the south of France, not far from the Mediterranean coast northwest of Marseilles. The familiar tale concerns the family of Rose Mamaï, a widow who runs her large farm, aided by her cheerful, naïve son Frédéri, who seems destined to marry Vivette, from a nearby farm, until he falls under the spell of the unnamed title character.

The film is not as splendid as the two earlier ones, but it is well worth seeing nonetheless. It gets off to a somewhat slow start, with a leisurely exposition of the locales and the characters. Frédéri’s growing obsession with l’Arlésienne takes its time. Still, conflict eventually creates greater drama as Rose learns of her son’s love for a woman “with a past” and the woman’s lover shows up to try and thwart her golddigging attempt to marry Frédéri.

The gorgeous cinematography and use of authentic locations, however, more than offset the plot problems (see frames above and at top). Like so many French directors of the silent era, Antoine took advantage of local carnivals and holidays, economizing by filming the crowds candidly. The frequent glances into the camera by locals testify to that.

To the far left of this frame, one can glimpse the well-known Roman amphitheatre of the town, used in L’Arlésienne for a bullfight scene, whither the villagers in their best clothes are headed.

Antoine’s film makes an interesting comparison with Alberto Capellani’s 1908 version, shown in the first Cinema Ritrovato season of his films. Capellani shot most of his excellent version in Arles as well, though in a very different style. (I discuss it briefly here and here; the latter entry gives information on the DVD releases of various Capellani films shown at the festival, including L’Arlésienne.)

Figaro (1927)

Gaston Ravel is a director whom many of us have heard of, but few of us have seen his films. His reputation is as a director of high-budget, prestigious films–comparable to Raymond Bernard, whose The Miracle of the Wolves (1924) is perhaps the most familiar of the epic period films of the period, excepting Napoléon vue par Abel Gance (1927).

With Figaro, Ravel manages to condense all three of Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais’s three Figaro plays (Le Barbier de Séville [1775], Le Mariage de Figaro [1781 but banned from performance until 1784], and La Mère coupable [1792]) into a two-hour film.

The result is a lavish spectacle. The costumes were designed by J. K. Benda, who later created those of La Kermesse héroïque (Jacques Feyder, 1935). The interior sets were studio-built (see bottom), though the exteriors of the later parts of the film were shot at a huge chateau with extensive grounds, the Rochefort-en-Yvelines. At least some French directors had by this point adopted and mastered Hollywood three-point lighting, as the frame above demonstrates.

Visually the film in fact looks like it could have been made in one of the big Hollywood studios, though the story is a bit too risqué to have been made there. (The young lady dancing and trailing a long, diaphanous veil in the frame at the bottom eventually spins until it drops off, leaving her completely nude.)

I found the casting of “artistic dancer” Edmond van Duren (as the program notes describe him) unfortunate. He reminded me of the overly merry Merry Men in Alan Dwan’s 1922 Robin Hood, bounding through nearly every scene. The rest of the actors were fine, particularly Arlette Marchal as Rosine, later the Countess Almaviva.

The tone also changes across the film, from comedy in the first part, to drama in the second, and then to tragedy (or melodrama?) in the third. The original plays premiered so far apart that the changes might have been less noticeable or made more sense. Mozart, however, was wise to confine himself to the middle play.

Apart from such problems, however, the film is entertaining, as well as being an important example of how ambitious a project French studios could occasionally manage–as does the film immediately below.

Belphégor (1927)

By the 1920s, Hollywood serials had declined from being the center of a program to being a low-budget side attraction. In France, however, serial storytelling remained quite central to the industry. Some serials were presented as discrete episodes, each involving a continuing set of characters, as in a television series. Other installment-films were “ciné-romans,” telling a continuous tale in blocks that might be published at the same time in newspapers and magazines.

Louis Feuillade’s death in 1925 ended his long string of beloved serials and ciné-romans for Gaumont. Other studios made equally popular, big-budget items, including Albatros, with Alexandre Volkoff’s 1923 La Maison du mystère. That film’s reputation lingered in film history despite the unavailability of complete prints until recently. By contrast, Henri Desfontaines’ Belphégor has remained largely forgotten.

Now it has been restored in a beautiful version. Although it, too, centers around a mysterious master criminal out to control the world, it is miles away from the wonderful mid-1910s serials of Feuillade. It’s instead a strange and impressive combination of various elements of French cinema of the 1920s. Where Feuillade shot in a rough-and-tumble way in the streets of Paris or the environs of Nice, with cheap sets for interiors, Belphégor‘s settings immediately remind one of L’Herbier’s L’Inhumaine and L’Argent. In particular, the exterior (above) and interiors (below) of the Baroness Papillon recall that of Claire Lescot in the former film.

Like Figaro, Belphégor has impressive production values and a grasp of Hollywood three-point lighting that creates dark, suspenseful shots. The film gained some prestige by supposedly being the first story to be set inside the Louvre. The interiors, of course, are sets, but ones that successfully convey the look of a major museum at night.

The script has a certain looseness, perhaps caused by the fact that the episodes were being released in parallel to the serialization of Arthur Bernède’s novel in Le Petit Parisien. That journal’s director also headed Cinéromans, a production firm making films exclusively for distribution by Pathé.

A meandering and repetitious plot is not the film’s main problem. The common–and probably correct–assumption that a film’s villain must be a strong, interesting character is completely ignored here. We see “Belphégor” only occasionally, looking like a person dressed in a burka with some checkered decoration around the head. Unlike Fantômas and other Feuillade villains, we never see Belphégor out of costume until the very end. Instead the villain’s machinations are largely carried out by a pair of thugs who have a faintly ludicrous, not-very-dangerous air. Belphégor, when encountered in the Louvre by the guards and investigators, invariably runs and, after a brief chase, escapes.

Oddly enough, the main detective, Chantecoq, is played by René Navarre, so memorable as Fantômas. (He was one of the co-founders of Cinéromans in 1919.) His presence hovers over the film, emphasizing that the main villain is barely present and does little.

Like the two other films discussed here, Belphégor’s pristine restoration, its beautiful sets and cinematography, and the expert lighting make it a pleasure to view. Complete serials from this era are so rare that as an historical document, it is welcome indeed.

Although these three films are not among the masterpieces of the 1920s (though L’Arlésienne comes closest), they give us more insight into French cinema of the day–a national cinema that has remained somewhat in the shadows of the German Expressionist and Soviet Montage movements of the same period.

As usual, the festival held its Il Cinema Ritrovato DVD Awards ceremony, though by this point the competition is dominated by Blu-ray releases. Our friends at The Criterion Collection, Flicker Alley, and Kino Lorber figured prominently in the awards and jury members’ favorites, as did international archives and companies. I have blogged about the two Flicker Alley jury favorites, Waxworks and Spring Night Summer Night.

Figaro (1928).

Wisconsin Film Festival 2021: Here and there

Calamity: A Childhood of Martha Jane Cannary (2020).

Kristin here:

Last time I wrote about three Middle Eastern films. Now I’m writing about three films that are all over the map and presented in no particular order. Such are the pleasures of film festivals, including the Wisconsin Film Festival, which wraps up Thursday, May 20. At 11:59 pm, all the films will be taken offline and we can all look forward to next year’s festival–with luck, back on the big screens of Madison.

The Village House (2019, India)

Achal Mishra’s first feature is a slow, entrancing, nostalgic love letter to his parents’ sprawling villa. The film is broken into three parts, set in 1998, 2010, and 2019. There is no real storyline, apart from the inevitable dissolution of the large extended family that inhabits the house in the first part. There is little dramatic conflict, either. Instead Mishra films everyday activities: men playing card games and teasing each other, women perpetually cooking or caring for a new baby, boys lured away from a game of hide-and-seek to go pick mangoes. It’s the sort of ideal of capturing the quiet poetry of life that the Neorealists never quite achieved.

Mishra admits to being strongly influenced by Ozu and Hou Hsiao-hsien (in his podcast discussion with programmer Jim Healy), and it shows, though there is never overt imitation. The camera never moves, and there are nearly as many shots of empty locales as those with people present. Idle conversations are lingered over in long takes.

Mishra also mentions Wes Anderson, and there certainly are quite a few planimetric shots in the film (above). The three time periods are also set off from each other by different aspect ratios: nearly square for 1998 (also above), widescreen for 2010 (second frame below), and full anamorphic widescreen for 2019. The purpose of these contrasting framings are quite different from Anderson’s in The Grand Budapest Hotel, where the the shots imitate the film ratios of the historic periods that the story moves among.

The narrow rectangle of the 1998 scenes suggests the crowded bustle of the house. From side to side it’s full of food (yet again above) and people in many shots.

We don’t get much of a sense of the geography of the house, just that it’s full of rooms where ordinary things are going on. We also probably have some trouble figuring out who all the characters are (especially since the jumps forward in time have different people playing them). Still, there’s always something to look at and listen to.

By 2010, the house is aging and the village offers fewer opportunities. One of the sons can’t find a job and wants to sell a plot of land to get money to start a pharmacy. Perhaps the biggest drama in the film comes when an older man tries to talk him out of it. The mundane is still present, though, as one brief scene consists of one character telling another, “The toilet door needs repair, and the kitchen door is jammed.” This casual-sounded remark turns out to be a hint of things to come.

The village still offers traditional festivals, but the sense of community has become less idyllic.

Slowly, however, the family members leave, culminating in the wordless departure of the old grandmother at the end of the 2010 scene.

The final third opens into full widescreen, with more extensive views of the house, empty or nearly so. These don’t give us a much better sense of its geography, but definitely a sense of its desertion by all by an elderly caretaker and some intrusive goats.

The renovation of the house starts at this point, though we are not shown what it eventually came to look like.

The Village House is available to stream anywhere in the USA until the end of the festival.

Calamity: A Childhood of Martha Jane Cannary (2020, France)

Rémi Chayé’s film won the Cristal for a Feature Film (top feature) at the Annecy International Animation Film Festival for 2020, and it’s easy to see why. Done with hand-drawn images, it has a look all its own. The unblended areas of color create a simple but beautiful set of images (top and above).

The story is aimed primarily at children. It tells an imagined tale of the childhood of Calamity Jane (about which very little biographical information survives), who gains skills and self-confidence when her widowed father is injured during a wagon-train journey west. It’s a woke story for the modern age, as young Marsha endures bullying from the guide’s son and ridicule over her tomboyish clothes and behavior.

Some of her achievements are bit over-the-top, but there’s a tall-tale aspect to the narrative–as is emphasized by scenes in which characters boast of their own acts of bravery around the campfire. It’s entertaining enough, but adults will probably be more impressed by the visuals.

The film is in French with subtitles. I would say that any child not old enough to read subtitles would probably be scared by some of the bullying, violence, and near disasters that occur, though older kids could probably handle them pretty well, given that all ends happily.

Calamity is also available nationwide for the duration of the festival.

Fear (2020, Bulgaria)

I went into Ivaylo Hristov’s Fear knowing little about it except that it deals with a middle-aged Bulgarian widow who captures a lone African refugee. At first she is afraid and suspicious of him but gradually, of course, comes to feel sympathy and even friendship for him. Something of a cliché in this day and age, I thought.

It turned out to be far more complex than a warmhearted tale of a bigot changing her ways. For a start, it’s a throwback to the more cynical of the black comedies of the Czech New Wave, with a similar kind of humor directed against the local authorities, primarily the border patrol and the mayor. They are required by law to feed and house refugees coming across the border before sending them onto the next facility. Most people crossing the Bulgarian border are on their way to Germany. Bamba, whose family have been killed in an unnamed African country, is going there, as are a small, hapless group of Afghans rounded up by the border patrol.

That patrol is mocked, as in the absurd line-up by height in the image at the bottom. They are completely unprepared to accommodate the Afghans, herding them first into the closed local school and later into the open-sided apartments in an abandoned construction site. These are not, however, the bumbling but largely harmless officers of The Firemen’s Ball. Underneath the gags, they are racist, ignorant bullies, roughing up the completely passive Afghans during the round-up. A chillingly funny interview of the officer in charge by a local TV reporter goes on in the foreground, with her repeatedly asking if the Afghans are armed and violent. When he replies that he’s never caught one with weapons or met any resistance, she begs for an anecdote of a time when the patrol was threatened. Again he says there wasn’t one, and she turns to the camera, triumphantly announcing that her audience has witnessed the dangers of letting refugees across the border.

The main story starts quietly by characterizing our heroine, Svetlana, as fearful. She has just lost her teaching job, and we learn that she goes regularly to the cemetery to talk with her dead husband. She lives alone in the country and sleeps with a hunting knife under her pillow. Jobless and not having received her last pay, she goes hunting and runs across Bamba on a forest path. Terrified, she marches him at gunpoint to the border-patrol office, which is deserted because of the mission to capture the Afghans. She tries the Mayor (above), but is told to deal with him herself.

On the first night she ties him up in the yard but eventually allows him to sleep in a locked room on an air mattress. Gradually she becomes more hospitable, to the point where the villagers begin to gossip about her, doing the things that people shocked by interracial couples do–killing Svetlana’s dog and tossing rocks through the window.

In between such episodes Svetlana and Bamba talk to each other, he in perfect British-accented English and she in Bulgarian. We learn a lot about both, but they learn little about each other and can only convey ideas like “I want to wash your clothes” with hand gestures. Nevertheless gradually trust and even warmth are established.

One could argue that Bamba is a bit too close to being a Magic Negro. Not only does he speak perfect English, but he’s a medical doctor. He’s patient and polite and does his share of the chores around the house once Svetlana lets him in. Still, it’s hard to imagine a plausible plot in which a less respectable-looking, working-class black man could win her over in the same way. Plus he is an engaging character, and he makes the dour Svetlana turn into one, so we are unlikely to complain.

The film is shot in impressive black-and-white anamorphic widescreen. There is one spectacular shot that’s quite breathtaking. It’s a drone image, starting on a simple sea view, moving backward through an open-sided room in the building under construction, and continuing on and on to reveal an immense, rambling, unfinished complex.

Did some entrepreneur envision turning the town into a seaside resort and lose funding partway through? We never know, but it provides an odd contrast with the poverty of many of the residents of a seemingly failing town. The only connection to the plot is that the Afghans spend a miserable time trying to live there until the border patrol gives up and trucks them further into the country in search of a place that can deal with them.

Fear turned out to be one of my favorite films of the festival, alongside Sun Children. It’s available for streaming only in Wisconsin through tomorrow.

The Festival’s Film Guide page links you to free trailers, podcasts, and Q&A sessions for many of the films.

Thanks as ever to the untiring efforts of Kelley Conway, Ben Reiser, Jim Healy, Mike King, Pauline Lampert, and all their many colleagues, plus the University and the donors and sponsors that make this event possible.

Fear (2020)

Wisconsin Film Festival 2021: Retrospectating

Keep Rolling (2020).

DB here:

Several of the films I’ve seen this go-round are either revived versions of older films, or recent films indebted to older traditions. Herewith, some thoughts on them.

Tender and tawdry

La Belle de nuit (1934).

I felt less dopey about not knowing about Louis Valray when Serge Bromberg, in an interview on the WFF site with Kelley Conway, confessed he’d not heard of him until he found an incomplete print of Escale (1935) by accident. Bromberg went on to find more footage, discover Valray’s first film, and secure the rights to restore and distribute them. Splendid in their restored versions (with curved corners on the frame), the films are at once generic and pleasingly perverse.

La Belle de nuit (1934) is a boulevard melodrama with hints of Vertigo and Les Dames du Bois de Boulogne. When a playwright discovers his wife has cheated on him with his best friend, he plots vengeance. By chance (i.e., dramaturgy) he finds a prostitute who is almost a dead ringer for the wife. He dresses her up, installs her in an apartment, and coaxes her to adopt a remote, mildly mocking manner. Of course, the treacherous best friend is in a frenzy to possess her. Wait till he learns about the past of his new passion.

La Belle de nuit alternates rather flat scenes of bourgeois flirtation with bursts of cinematic energy. Like other early sound films, there are some sharp auditory transitions. Dynamic hooks link scenes with sounds, images, or both: automobile wheels, locomotives, phonograph records.. There are peculiar angles and, most noticeably, a fascination with the unattainable woman. As ever, cigarette smoke helps the mystique.

I suspect that Valray learned a lot from making this first film because I found Escale a more polished production. Like his debut, it centers on a fallen woman who hangs around hazy cafes where hard-used women stroll among tables and sing about the troubles of life. Jean, an uptight lieutenant on passenger ships, falls in love with Eva, who hangs around smugglers in her seaport town. Jean and Eva share an idyll, and she seems redeemed. But when Jean leaves on a voyage, Eva’s loyal manservant Zama can’t keep her from succumbing to the mesmeric bootlegger Dario.

Escale has more exquisite visuals than La Belle de nuit. Filmed on a lush Mediterranean island, it bathes its landscapes and sea vistas and seedy port with a languid melancholy akin to that of Pépé le Moko (1937). Practically every shot, on land or sea or in the alleys or the boudoir, yields brooding, hypnotic imagery.

I find Escale‘s villain far scarier than the fussbudget playwright of La Belle de nuit. Dario wears more mascara than Eva, but the effect is to give him the burning glance of the true monster.

Both films, available on French DVD, would be a fine double feature for an enterprising US disc publisher or streaming service. Thanks to Bromberg and Lobster Films, they can be seen in their full glory.

A Taiwanese revelation

Just as the Valray films cast a new light on 1930s French cinema, so The End of the Track (1970) puts the standard history of Taiwanese cinema into a fresh perspective. The story is that the New Taiwanese Cinema of the 1980s, developed by Hou Hsiao-hsien, Edward Yang, and others, created a fresh turn toward social realism and more adventurous storytelling. Their tales of rural life and urban anomie clashed with the entertainment genres of commercial cinema and the government-sponsored films asserting that under Chiang Kai-shek’s Kuomintang regime life was buoyant and carefree. With The End of the Track we have a fine predecessor, a “parallel” film that dared formal and thematic opposition to the mainstream, and did so well before the New Wave directors.

Yung-shen’s father and mother run a noodle cart; Hsiao-tung’s family is well-off. But the boys are fast friends. They enjoy long days in their rural paradise–swimming naked, play-fighting, and exploring caves. The film’s first twenty-five minutes are almost plotless, built out of routines of school, play, and homework. But then a crisis strikes, and the film turns achingly sad in a quiet, unmelodramatic way. The plot shifts slowly to a study of how one boy becomes a surrogate son for a grieving family, while his own parents respond uncomprehendingly.

The boys’ skinny-dipping and mud wrestling earned the film a ban for “homosexual undertones and ideology.” There’s surely a homosocial, and maybe homoerotic undercurrent, but the main impression is that of devoted friendship and the heavy weight of obligation. One boy must leave childhood behind, too soon, and start a new life. Just as powerful is the class component. In one grueling sequence, Yung-shen’s parents try to push their cart through typhoon-swept streets as Hsiao-tung’s parents look on from their car.

Pictorially, director Mou Tun-fei makes full use of the glorious scenery that rural Taiwan can yield. He uses fast cutting, handheld shots, abrupt flashbacks, and other “modern cinema” techniques. These techniques can be seen in many commercial Taiwanese films of the period, but most directors used them to jazz up generic plots. Here, the fastidious black-and-white palette gives them a certain sobriety. The gravity is enhanced by severe but lyrical compositions, like this planimetric shot of the boys laying out a running track.

Above all, the slow pace of the film–the basic story is almost an anecdote–allows Mou to soak us in the characters’ milieu. There are even some prolonged, static long shots that look ahead to the precisely unfolding scenes we get in Hou’s films and in Yang’s A Brighter Summer Day (1991).

Mou is now, like Valray, a rediscovered director enjoying belated fame in his national cinema. In a very helpful discussion of his career, Wafa Ghermani and Victor Fan point out that there was at the period an important trend toward independent, low-budget films in Taiwanese (rather than the official language of Mandarin), and Mou’s work is just one example. As usual, a festival screening can remind us that there’s a lot more powerful cinema out there than we’ve realized.

Her time has come

Keep Rolling (2020) isn’t an old film, but it’s about a director who has over forty years quietly carved her own niche in world cinema.

In the 1980s, a new generation of filmmakers overturned Hong Kong cinema. Some, like Tsui Hark, Jackie Chan, and John Woo, brought a turbocharged version of the New Hollywood to a film culture already energized by a tradition of martial-arts action. Other young talents formed what came to be called the Hong Kong New Wave. Although Tsui was sometimes identified with this, this trend was not so brash. It moved toward social realism, with directors like Allen Fong and Stanley Kwan exploring a modernizing Chinese culture living under colonial rule but forging its own identity.

Of all the New Wave directors, Ann Hui distinguished herself by her sincere and dogged attention to Hong Kong life as it is lived. After making some docudramas for television, she directed her first feature, The Secret (1979) and won festival attention with Boat People (1982) and Song of the Exile (1990). Although she has happily embraced genre films–she has made ghost stories and thrillers–she always treats sensational material with a calm, unspectacular attention to characterization and mood. Her swordplay film, the two part Romance of Book and Sword (1987), emphasizes landscape and interpersonal drama over action set-pieces. Who else would make Ah Kam (1996), a martial-arts movie centering on a stuntwoman?? She brought attention to social problems, sometimes in advance of social policies: caring for a parent suffering from dementia (Summer Snow, 1995), the need to shelter victims of marital abuse (Night and Fog, 2009), and lesbian rights in Hong Kong (All About Love, 2010).

In all, she has directed twenty-eight features. Every one has been a struggle.

Because the local market has been small, Hong Kong filmmakers have had to look abroad. For directors like Tsui and Woo, that meant making flamboyant action vehicles for audiences across East Asia, as well as for the Chinese diaspora and fans in other territories. But Ann Hui’s commitment to local life meant that her films had to gain wider attention on the red-carpet circuit. They did. Over the decades, they routinely played the major festivals. Her A Simple Life (2011) got a standing ovation when it played Ebertfest in 2014; Roger called it one of the year’s best films.

Last year Kristin and I were sorry we couldn’t be in Venice to watch her accept a Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement. In response to my email of congratulation, she was characteristically modest in facing a 14-day quarantine when she returned home. As ever, she makes personal contact:

Tonight I am dead beat n have a whole day of press tomorrow before I leave on the day after. I promise myself I’ll only stick to filmmaking from now onwards. How r u and is the pandemic bad in your area? HK is bad all the way you must know. Will u still come n visit us? Take care n keep well! Ann

Ann’s career receives a fitting tribute in Man Lim-chung’s Keep Rolling. It surveys her life, with fine interviews with her sister and brother, along with comments from friends and critics. There’s a lot of behind-the-scenes production footage. Above all, Man offers a personal portrait of her persistence and dedication. Virtually the only female director to make a career in Hong Kong, she has contributed to the world’s humanist cinema shaped by directors like Kurosawa, Kiarostami, and Satayajit Ray. Stubbornly sincere, with no PoMo flash or trickery, her small-scale studies of character always have wider social resonance. One can only hope that this film brings her–and her films, shamefully neglected on DVD–to more audiences.

The four films reviewed above are all available from the Festival across the USA until midnight Thursday. You can sign up here.

The Festival’s Film Guide page links you to free trailers, podcasts, and Q &A sessions for each film.

Thanks as ever to the untiring efforts of Kelley Conway, Ben Reiser, Jim Healy, Mike King, Pauline Lampert, and all their many colleagues, plus the University and the donors and sponsors that make this event possible.

For more on Ann Hui’s visit to Ebertfest, go here. We’ve reviewed many of Ann’s films on this site; check the category. I discuss trends in Hong Kong cinema in Planet Hong Kong and consider some aspects of Taiwanese film in Chapter 5, on Hou, in Figures Traced in Light: On Cinematic Staging. I sure wish I had known The End of the Track when I wrote that chapter.

The End of the Track (1970).