Archive for the 'National cinemas: France' Category

Madalena, Rosalind, and Suzanna: More Rotterdam revelations

Madalena (2021).

DB here:

A mixure of moods and tones for our final communiqué from the International Film Festival Rotterdam. Its fiftieth year has been a lively one.

The Madalena mystery

Madalena (2021).

In earlier entries (especially here) I’ve noted that the thriller genre is well-adapted to festival circulation. It doesn’t require the budget of a blockbuster. It can attract major actors who want tricky parts to play. It can be shot on contemporary locations. And the appeal to suspense and surprise fits comfortably with edgy narrative strategies favored by art cinema. At the limit, a filmmaker can arouse our thriller appetites and then try a bait-and-switch that not only warps the genre’s conventions but sets us thinking.

The Brazilian film Madalena, by Madiano Marcheti, starts as a classic mystery. In a vast field of soy, reas stalk gracefully as a monstrous pesticide-sprayer grinds toward them. But among the rows lies a corpse.

What follows is more fractured and prismatic. A first section attaches us to Luci, a friend of Madalena’s who works as manager of a club. She also picks up work dancing for TV commercials, one set in that very acreage. Then we follow Cristiano, whose father owns the land and demands he hustle to harvest. A third section takes us with trans woman Bianca and her girlfriends, who sort through Madalena’s belongings before setting out for a day of driving, swimming, gossiping, and teasing one another, the memory of Madalena never far from their thoughts.

Marcheti skips some of the standard scenes. We never see the police investigation, or even the discovery of the body. The crime plot has been a pretext to reveal a cross-section of life in the community, from the wealthy farmers to the cottages where the staff live. The resolution shifts the question of who did it to the broader impact of the death, and how it stands for a horrifying statistic: Brazil has the world’s biggest murder rate of transgendered people.

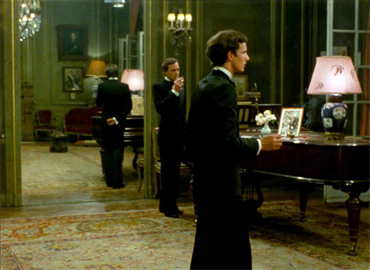

Throughout, sexualization of bodies is a central motif. Luci and her posse hang out at curbside, Bianca and her posse turn tricks and find boyfriends, and Cristiano, after sizing up the crowd at Luci’s bar, winds up dancing with himself in mirror reflection.

To say much more would spoil things, so I’ll just note that this story is filmed with a pictorial intelligence that one seldom sees these days. The imagery of the soy fields is at once magnificent and ominous. Drones hover over it like birds of prey, and its horizon haunts the people’s lives.

Overwhelming as the landscape is, it doesn’t blot out the characters’ routines and the crises that disrupt them. Moving from Luci’s aimless days and nights to Cristiano’s panic to Nadia’s quiet tribute to Madalena, a locket set adrift in the stream that runs along the field, the film pauses for intimate moments. It reminded me a bit of Varda’s great Vagabond (Sans toit ni loi), in which an enigmatic figure’s fate charts the range of human indifference, but also affords glimpses of sympathy.

An informative discussion of the film with Marcheti is provided by IFFR here.

As we too like it

As We Like It (2021).

This movie saw me coming a mile away. It does for As You Like It what Lurhmann did for Romeo and Juliet, but to an Asia-pop beat. Four romantic couples lose and rediscover one another in a magical milieu–not the Forest of Arden (currently under corporate development) but a district of Taipei with no Web connections. In Heaven, a sign informs us, there is no Internet.

Accordingly, people must deliver messages in person, seek out each other by dint of shoe leather and motorbikes, and actually meet face to face. So Rosalind’s quest to find her father the Duke (a genial tycoon) intertwines with Orlando’s search for her. But of course she’s disguised as a boy and aided by Celia, a fortune-teller who’s the dream girl of Orlando’s sidekick Dope.

The film’s world is maximum kawai, pushing beyond camp to a fangirl fantasy of irresponsible sweetness. This candy-colored city, with its pink blimps and anime posters, spills over with tweens, teens, and twentysomethings shopping in malls, flirting at stalls, and sipping bubble tea.

In the process, old stuff becomes cool. Tradition, in the form of calligraphy and handmade paper, is a retro decorator choice, while letting your date clean your ears old-style makes him a friend with benefits.

It might all seem sappy, but like Tati’s Play Time and Wong Kar-wai’s Chungking Express, the film seeks to distill authentic poignancy out of kitsch, schlock, consumer clichés, lethal cuteness, and the detritus of urban lives. Frivolity must be good for something; why else would God give us giggles? Comic form, as Shakespeare acknowledged, redeems a lot of silliness, especially if the gags are hurled at us with the ruthless conviction that anything goes.

Did I mention that all the roles are played by female performers?

In a switcheroo on Elizabethan theatre, globalization inverts the Globe. The film, a final title tells us, is dedicated to Shakespeare “but also to the patriarchy who would not allow female actors upon the stage.” The frisson is akin to that of Tsui Hark’s Peking Opera Blues and The East Is Red, where gender-blurring yields both humor and genuine feeling. From instant to instant, you see a character go male or female or something in between; a painted-on mustache and a swaggering gait become cosplay, not deep definitions of you. Unless you want it to be.

Identities are fluid. Okay, says Orlando, so he falls in love with Rosalind, then Roosevelt, and refinds him/her as Rose. What’s in a name? You get to call yourself, and be, what you wish, and love whoever.

Not a fresh-minted message these days, but the sparkle comes with how it’s all carried off. Every scene finds a clever way to amuse or bemuse. When Rosalind as Roosevelt slips into a trim suit, she pads out the crotch with a towel, and teeny gull-like waves waft out. That’s soft power, the equivalent of a mystic ring. Eventually she has to go along when Orlando visits the men’s room. While he stands at the pissoir, she ducks into a toilet pretending to take a dump, her groans covering the sound of peeling open a maxi-pad.

The project was co-directed. Wei Ying-chuan, a graduate of NYU’s Educational Theatre division, is a founder of Shakespeare’s Wild Sisters Group in Taiwan. Chen Hung-yi’s feature The Last Painting was chosen for IFFR in 2017 and won a best feature award at Cines del Sur. The pair bring an unflagging energy to the task of creating a paradise of easy living and loving–bereft of villains, open to any piece of harmless fun and heartbreak. As We Like It is a must for every LBGTQ film event, but its hella dirty fun for any festival whatsoever. Couples welcome.

Again, the IFFR provides a fine discussion of the film with the directors, moderated by our old friend Shelly Kraicer.

St. Tropez, mon amour

Suzanna Andler (2020).

Eric Bentley once described great serious literature as “soap opera plus.” Anna Karenina, Othello, and the rest offer us tormented love affairs, sexual jealousy, hidden schemes, and forced confessions of betrayal, but it’s all endowed with wider significance through characterization, implication, style. But can we have soap opera minus?

In Daisy Kenyon, Anatomy of a Murder, and other films, Preminger moves in this direction, banking the fires of conflicts drawn from lurid bestsellers, but other filmmakers have gone further in de-dramatizing melodrama. Dreyer’s Gertrud and some of Oliveira’s adaptations offer examples. Here we have the classic fraught situations, but muffled and fragmented and punctured through long pauses and wayward, looping, maddeningly banal conversations.

Marguerite Duras made this artistic strategy peculiarly her own, notably in her masterpiece India Song (1974) and its counterpart Son nom de Venise en Calcutta désert (1976). In a curious reversal, she often prepared the film first and then published the text as a quasi-play, as if scraping away the luscious imagery and ripe sound would create something even purer, soap opera distilled to Racinian starkness.

Suzanna Andler, a Duras theatre piece from 1968, has now been adapted to film featuring Charlotte Gainsbourg and three other players. The result isn’t as severe as the play reads, since director Benoît Jacquot has filmed it in a gorgeous villa overlooking the Mediterranean. It remains, however, in the tradition of kammerspiel. The bulk of the action takes place in a salon and the terrace outside, with one sequence, also in the play, set on a rocky beach.

The situation is sheer bourgeois melodrama. Suzanna is in a loveless marriage with the philandering Jean. She has apparently stayed with him for the sake of their children and the wealthy life they lead. Now Michel, a young journalist, has tempted her into a love affair, and she has for the first time cheated on Jean–who seems okay with it. Today’s crisis, if this counts as one, is her need to decide: Will she lease this villa for the summer with the kids? Or will she accept Michel’s invitation to go to Cannes? In the course of about four hours, she may make up her mind.

If some of my synopsis seems hazy, it’s partly because the exposition comes out in bits as Suzanna and others chat about her past, and partly because what she says may not be wholly truthful. She sometimes admits to lying. And what was her relation to the never-seen Bernard Fontaine, who has just been killed in a car crash? The blurry backstory is one strategy Duras uses to tamp down the melodrama, which usually gives its plots clear-cut contours and definite revelations.

In filming the play, Jacquot has taken an approach that approximates the rigor of Duras’s aesthetic. He has shot the blocks of action using slightly different techniques. Not for him obvious alternatives like color/ black-and-white or a range of tonalities. The differences are made harder to spot because Jacquot has not given us separate chapters corresponding to the act divisions; the scenes blend, punctuated only by long shots. So there are stylistic spoilers coming up.

At the start, Suzanna is shown the house by the real estate agent de Rivière. This segment is filmed in distant shots that emphasize the landscape and straight-on views of the sitting room opening out onto the terrace and the sea. The agent is seen from behind or at a distance, while the few close views we get concentrate on Susanna.

Staying behind alone, she falls asleep and awakes when Michel enters. This is a second phase of the play’s first act, and now Jacquot’s camera setups take a more oblique view of the room. The full-length windows dominate again, but now at an angle that recalls the magic mirror of India Song (on which Jacquot was an assistant).

The couple is often seen at a distance, but now closer views of Suzanna emphasize the mirror motif.

At a high point, the camera celebrates a momentary reconciliation with a track in to their embrace (the first such florid move in the film, I think).

In the sequence corresponding to the second act, Suzanna meets her friend (and Jean’s ex-lover) Monique. On the beach they talk of their pasts. Now the conversation is rendered in many rapid, tight shots of the two women. The orthodox shot/ reverse shot setups are sometimes given a strange emphasis when instead of A/B alternation we get two (but only two) variants of a view of each one as she speaks (A1/A2, then B1/B2). So a cut like this::

. . . is followed by ones like these:

Back at the villa, Suzanna answers a phone call from Jean, and they discuss their plans, with the uncertainty typical of all the film’s conversations. This scene is handled in circular tracking shots around Suzanna, from a moderately close distance.

As the conversation ends, Michel returns. After he reveals some key information about his relation to Jean, he stretches out on the sofa. In a long take running several minutes, the camera swings around them in a half-circle, clockwise and counterclockwise, often adjusting to her shifts in position.

The changing angle also captures Suzanna perched against a painting of very 60s boomerang shapes that echo the camera’s trajectory.

As the action approaches what might be a climax, Michel drifts out to the terrace and sits on the balustrade above the sea. Suzanna approaches.

Telling you what happens next would truly be a spoiler. On seeing it, I thought it was something that Jacquot added to the play, but nope . . . it’s there in the text, and he’s perfectly faithful to it.

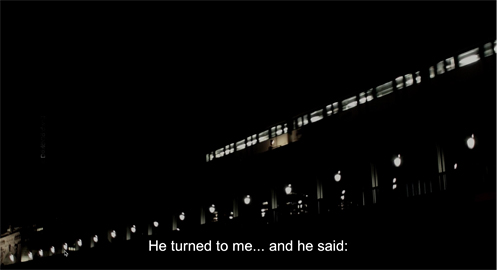

As if all this patterning doesn’t look finicky enough, the scene on the beach is punctuated by a single shot of the Quai de Passy with a Métro train rumbling by.

This bump comes exactly halfway through the film, at the moment Suzanna mentions the surge of attraction she felt when Michel looked at her on their first encounter. Believe it or not, the line in the play also comes midway through the text. This alien shot functions expressively, I think. It underscores the epiphany Susanna felt upon learning she might be loved. Another filmmaker might have stressed the moment with music under her monologue, but Jacquot goes for a formal bonus: breaking the visual texture just here further articulates the design of his film.

The rigorous geometry Jacquot has clamped down on the play is interesting in itself, and the abstract array of options adds, I think, to the hieratic quality Duras is after. Yet each style matches the tenor of the action it carries and doesn’t conceal the subdued feelings rippling through the scenes. This dimension depends on Gainsbourg–her slim silhouette, her microdress, and especially her face, with her alert chin and hard mouth. Her vacillations have nothing of the diva about them, but still she stands forth as a new avatar of The Confused Woman so beloved of art cinema (Voyage to Italy, L’Avventura, The Headless Woman). Without those closer shots, the film might fall flat.

Once asked what would be his ideal final shot, Jacquot replied: “A distinctive glance [un certain regard] in close-up.” His ending delivers that.

Duras is doing something similar to what Wei and Chen do in As We Like It. She is seeking genuine emotion in clichés (unfaithful husband, wrung-out wife, surly rescuer). But she hasn’t exempted her characters from social critique. Hiroshima, mon amour renders the meeting of two lovers as an intertwining of two national histories. The colonialists of India Song, drifting through their sparsely attended embassy parties, trying to replicate salon society in the tropics, cannot hear the voices offscreen of the people they subjugate. Likewise, Suzanna’s anxiety may or may not register some distant tremors. In summer of 1968 her world is sliding into something she isn’t prepared for. Far away from St. Tropez, in Paris students are hoping to find their own beach, but they’re doing it by tearing up the pavement.

Again, thanks to Gerwin Tamsma, Monika Hyatt, Frédérique Nijman, and their colleagues at the International Film Festival Rotterdam for allowing us to visit their event virtually. Here’s to another fifty years of ambitious programming!

A very helpful edition of Suzanna Andler has been published in conjunction with the film’s release. It contains a lot of stimulating background information and critical commentary. Bentley’s comment about “soap opera plus” comes from The Life of the Drama (Applause, 1991), 14. Thanks to Kelley Conway for sharing with me the Jacquot interview in “Réponses à tout,” Libération (14 May 2004), 1.

Jacqout’s rendition of Duras’s play exemplifies what I called in Narration in the Fiction Film “parametric narration.” This rare approach consists of playing out a range of expressive possibilities, scene by scene, in ways that both shape the ongoing plot and “anthologize” sharply contrasting cinematic techniques. Noël Burch first proposed this idea in his enduring Theory of Film Practice (1973), although Eisenstein and Bazin envisioned it. But then they envisioned everything.

P. S. later: The Rotterdam prize winners have been announced (per Variety).

As We Like It (2021).

The ten best films of … 1930

The Blue Angel (1930)

Kristin here:

The end of this horrendous year is fast approaching, though we are still facing a long struggle to end the pandemic. On a happier note, it is also time for a little distraction in the form of my annual year-end round-up of the ten best films of ninety years ago. 1930 was also a grim year, with the Depression well established and nowhere close to its end. Herbert Hoover decided not to use federal governmental powers to help end the crisis (sound familiar?) and eventually was cashiered into a 32-year retirement, though he continued to oppose Roosevelt’s policies. At least we don’t face that long a stretch of down time with the current “president.”

I discovered that 1930 did not produce many masterpieces. There are some obvious titles on my final list, as always, but some of the films are good but not great. In any other year they would not have made the cut. (The contrast with 1927, for example, is pretty stark.) Presumably one major reason is that filmmakers were still struggling with the introduction of sound. Fritz Lang didn’t release a film that year, though he came roaring back with M in 1931, as assured a treatment of sound cinema as one could find during those early days. (For those of you who subscribe to The Criterion Channel, I contributed a video essay on sound in M to David’s, Jeff Smith’s, and my series, also called “Observations on Film Art.”) Eisenstein was off in Hollywood unsuccessfully trying to make a film for Paramount and about to fall in love with Mexico. With one notable exception, Hollywood’s important auteurs made no films or minor films or films that don’t survive.

This dearth of really great films will be short-lived. From 1932 on, I shall no doubt have the opposite problem. For now, here are my picks. All the films are worth seeing, though good copies or even any copies of some are hard to track down. (The idea that all films are available to stream online is as absurd as when, back in 2007 when I wrote “The Celestial Multiplex.”) Some of my illustrations in this entry are subpar, but 1930 does not seem to be a year that studios and home-video companies are mining for titles to restore. I hope this entry will give them a few ideas.

I try not to include more than one film by the same director in these entries, aiming for variety and coverage. This year’s most prolific great directors were Josef von Sternberg and Yasujiro Ozu, who together could have filled in half the ten slots, but I have stuck to my guideline. (When we reach 1932 and 1933, I may be tempted to make an exception for Ozu.)

Given that sound developed at a different pace in different countries, some of this year’s films are silent.

For previous 90-year-ago lists, see 1917, 1918, 1919, 1920, 1921, 1922, 1923, 1924, 1925, 1926, 1927, 1928 and 1929.

Dovzhenko’s Earth

Some of the films on my top-ten list this year may raise eyebrows, but Earth is probably my least controversial choice. It remains one of the last classics of the Soviet Montage movement.

The policy of merging small farms into collective ones had begun in 1927 as part of the First Five-Year Plan. In 1929-30, the push increased, with the seizure of the assets of the more prosperous peasants who resisted collectivization, termed kulaks. Major films were made with the aim of villainizing the kulaks and emphasizing the backbreaking labor involved in traditional, non-mechanized farming. Eager young peasants were hailed as heroes, and tractors appeared as the means to greatly increase wheat yields–wheat which was often seized and sent to the cities to enable rapid industrialization.

Eisenstein had promoted collectivization with his Old and New in 1929, and Dovzhenko followed a year later with Earth. While Eisenstein’s approach had been sarcastic and comic, Dovzhenko pursued his poetic approach to cinema. The opening celebrates the fecundity of the earth and the cycles of nature. The famous opening juxtaposes a peasant girl’s face with a large sunflower. Semion, an aged peasant, is calmly, even cheerfully awaiting his imminent death, lying on a blanket and surrounded by heaps of apples.

A kulak family is soon introduced, angry at the idea that their possessions will be seized. The head of the family declares that he will kill his animals rather than turn them over, and he tries to attack his horse with an axe.

The arrival of the village’s new government-provided tractor marks a shift to an emphasis on the advantages of collective farming. As it approaches, the kulaks stand watching and mocking the idea of a machine taking over. In one shot, an elderly kulak stands framed against the sky, his wealth indicated by the presence of a hefty cow. The tractor temporarily halts, but it turns out that the radiator is dry. The simple solution is for the collective members to urinate into it.

Earth is a visually beautiful film, but like other Soviet classics I have complained about, there is no decent print of it available. The old Kino disc groups it with Pudovkin’s The End of St. Petersburg (the cropping of which I mentiooned in the 1927 entry) and Chess Fever. The copy of Earth is too dark and indistinct. To get some frames for illustrations, I watched the visually superior copy on YouTube, but there the images are cropped to a widescreen format. Just as bad, there are ads scattered through it, including one in the middle of Vasyl’s twilight dance in the road just before he is shot!

As before, I must end by pointing out that an archival restoration and a Blu-ray release are in order.

Ozu debuts on the list

Although after 1937 there are years when Ozu did not make a film, he will likely feature on these lists as long as I continue to post them. In 1930 he made six features and a short. Only three survive: Walk Cheerfully, I Flunked, But … , and That Night’s Wife. I’ve chosen the last, though Walk Cheerfully is a viable candidate as well. Sound was adopted slowly in Japan, and Ozu held out until 1936 before releasing his first talkie, The Only Son, which will doubtless feature on my list for that year.

The British Film Institute released That Night’s Wife in a boxed set called “The Gangster Films,” along with Walk Cheerfully and Dragnet Girl. Yes, Ozu made gangster films, including the wonderful Dragnet Girl, the film that might lead me to make my exception in the 1933 entry.

That Night’s Wife, though, is not really a gangster film. Shuji, the father of a daughter with a potentially fatal illness, is not a gang member but a decent working man who stages a hold-up to get money for her medicine. Ozu handles this hoary plot premise with his usual unconventional approach.

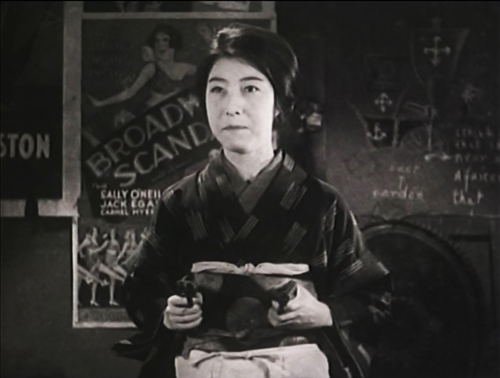

The opening, with its shots of dark, empty streets through which the police chase Shuji, is film noir ahead of its time. We soon are introduced to his worried wife, Mayumi, tending the little girl. She’s cute but has a distinctly bratty streak so common to Ozu children. This and fairly frequent moments of subtle humor help Ozu avoid a purely melodramatic presentation of the situation.

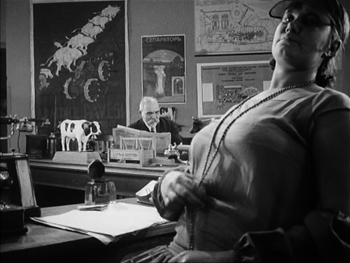

Once Shuji arrives at home, Mayumi gets him to confess what he has done. He intends to turn himself in after the daughter’s crisis passes, but a gruff detective who has posed as a cabby to find out where he lives, appears. Being told that the daughter will only survive if she lasts through the night, the Detective agrees to stay and settles in to guard his prisoner. Mayumi reveals her inner toughness and determination to defend her husband. At one point the Detective dozes off and she steals his gun and points it and her husband’s pistol at him, urging Shuji to escape (above). That shot, by the way, shows a motif typical of early Ozu films: having posters, often for American movies, visible on the walls behind the characters.

That Night’s Wife doesn’t display the fully mature Ozu style, but no one would mistake it for a film by another director. He has already mastered the perfect match on action, and he uses one in the early scene where Mayumi sits down as the doctor tends the daughter. Ozu cuts in with a move across the axis of action that places us 180 degrees on the other side of her.

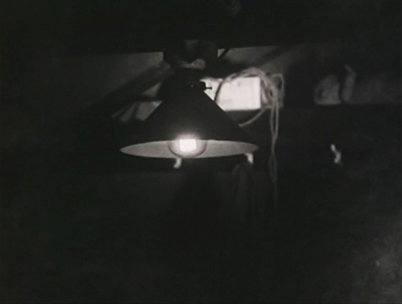

Ozu is not using 360-degree space consistently yet, but he’s playing with the idea. Twice he has transitions that move through a series of adjacent spaces, one of his key devices and one that will last throughout his career. Here we move from the worried Mayumi to Shuji, trying to elude the police after the theft.

There’s a lyrical motif mutating from shot to shot: worried wife, interior lamp, interior plant against wood, outdoor light with leaves, stone building with the shadows of leaves, and stone building with the subject of Mayumi’s thoughts, cowering. But causally the four “extra” shots tell us little about where Shuji is in relation to the home he seeks to reach.

I took these frames from the BFI set, but in the US Criterion released the same three films in its Eclipse brand under the more accurate title “Silent Ozu – Three Crime Dramas.” (I Flunked, But … is in the BFI’s four-film set, “The Student Comedies.” Criterion hasn’t released a DVD of it, but it is streaming on the Channel.)

The Germans’ sound advantage

Unlike other countries, Germany developed its own sound system, owned by the Tobis-Klangfilm company. Tobis was initially able to use court injunctions to keep American films out of the German market. In 1930, this pressure led ERPI and RCA, owners of patents on the major US sound-on-film systems, to form a cartel in conjunction with Tobis, which had producing and distribution subsidiaries throughout Europe. Tobis-Klangfilm continued to dominate European sound recording and reproduction until the beginning of World War II.

Partly as a result of this technical advantage, several early 1930s German films became classics, though not all of them are known abroad.

One internationally famous classic is The Blue Angel. I’ve mentioned that von Sternberg was among the most prolific of major directors in 1930. I debated whether to put this or Morocco on the list. If cinematography were the main criterion, Morocco would have been the choice. Not surprisingly, Lee Garmes’s camerawork and lighting is spectacularly good.

I initially saw The Blue Angel decades ago, in grad school. It was the usual hazy 16mm print of the American release version. Watching it again in the German version, remastered from a 35mm negative, was a revelation. Not that it will ever be one of my favorites. It has its problems. The motif of the clown, implied to be Lola’s degraded ex-lover, is heavy-handed. Emil Jannings’ lumbering performance as Prof. Rath is at odds with the casual realism of the other performances. The time-passing montage accomplished via a hair-curler ripping down a series of calendar pages creates a time gap of years passing and the characters–especially Lola–have changed radically. Her change from a kind attitude toward Rath to cruelty and indifference is logical, given his passive decline from professor to clown, but it is presented too abruptly. Still, in my opinion the film’s pluses outweigh its minuses.

The Blue Angel, seen in a good print, is wonderfully photographed as well (see top). It may not have Lee Garmes, but it has Günther Rittau (co-cinematographer with Hans Schneeberger). He had lensed Die Nibelungen, Metropolis, Heimkehr, and Asphalt. He brings a dark look to the film, as in these shots of Rath in dignified professor mode and later onstage in a caricature of his former self.

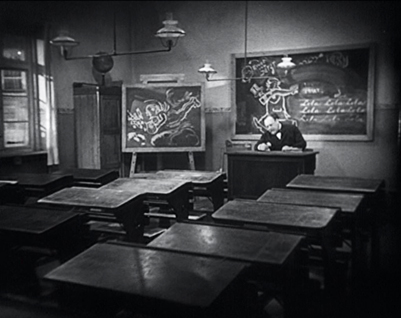

The camera movements are rare and unobtrusive. A visual motif set up early on shows the bustling classroom that Rath presides over, where despite the students’ dislike of him, they obey his strict commands. Later, in after Rath has visited The Blue Angel and met Lola, his blackboard is covered with caricatures and insults drawn there by the students to mock his obsession with Lola. A slow track back emphasizes the empty classroom as he sits at his desk, his authority over the students gone.

No doubt it’s a matter of taste, but I find Marlene Dietrich’s performance here more attractive than in Morocco–and it is, of course, central to the film’s appeal. Her amused playfulness with Rath, her quietly sarcastic attitude toward her sexuality being The Blue Angel’s main attraction, and her frequent bits of business with props unrelated to the story all differ considerably from her Hollywood performances. She has a natural glamor here that will disappear in her roles for von Sternberg in Hollywood.

After this film, von Sternberg made Dietrich a Hollywood symbol of glamor, but as a result she tends to be less spontaneous and active, with the camera and lighting lingering over her. Basically her glamor became more sultry. The result has its own appeal (and Shanghai Express is a good bet for a place on the 1932 list), but it is revealing to see her performing in a way that she only recaptured occasionally, if at all, in her subsequent films.

The frames were taken from the Kino on Video two-disc set, which has both the German and truncated American versions, as well as some supplements. It was subsequently released on Blu-ray, but I haven’t seen that version.

I always try to call attention to little-known films rather than sticking to the conventional classics for the whole list–and there aren’t a lot of such classics this year anyway. This time it’s a charming, imaginative musical romance, Die Drei von der Tankstelle, or “The Three from the Filling Station,” directed by Wilhelm Thiele and starring Lilian Harvey and Willy Fritsch. It was so popular that it outgrossed The Blue Angel in Germany.

Three carefree young men, who start off driving in a car and singing about friendship, arrive in their lavish shared home to discover that they are bankrupt. Low on gas, they are inspired to start their own filling station. They sing a nonsense song, “Kuckuck” (the German equivalent of “cuckoo”) as their belongings are hauled away, and they give this name to their art-deco filling station.

Lilian (the heroine’s name as well) shows up in search of gas for her roadster, and the three men fall in love with her. The rest of the film involves their competition over her. Naturally she chooses Willy (Fritsch’s character name). The two were often paired in later German films of the 1930s and became the ideal movie couple.

The film maintains its playful, often silly tone until the end. As Lilian and Willy are united before a closed theatrical curtain, she turns front and says, “People! The public!” There is an objection that this is not the way to end an operetta and the curtain opens to reveal the entire cast as well as additional dancers and singers performing a lively and somewhat chaotic grand-finale number.

I originally saw this film at the Cinémathèque Royale de Belgique (now the Cinematek). As it does not circulate in the US on home-video, I have taken these low-quality frames from a homemade DVD, probably originally dubbed from an unsubtitled German VHS copy. It is available on a German DVD, since it is considered a perennial classic there. Unfortunately it has no subtitles. (The German manufacturers do not seem to have cottoned onto what their counterparts in other European nations–notably France–have: that if you include optional English subtitles, you can sell more copies.)

I hope, however, that eventually someone at the DVD/Blu-ray companies will discover this very entertaining film and make it more widely available.

A German director abroad

F. W. Murnau’s City Girl is another of those films I saw in a poor print decades ago and respect a great deal more after seeing it in a good version and knowing more about film than I did then. I wouldn’t put it in the same league as some of his earlier films, but for a 1930 list, it stands out.

Murnau was already on the way out at Fox when he was making the film. After his departure, the film was “finished,” including some dialogue scenes that were inserted. As with several other films of the era, such as Borzage’s Lucky Star and Duvivier’s Au Bonheur des Dames (see below), we are lucky in that only the silent version survives. The restored dialogue scenes in Fejos’s Lonesome show how ghastly these added interludes could be. (My apologies to the restorers. Obviously somebody had to do it.)

The heroine of the title is Kate, a waitress in a busy Chicago diner. Disillusioned by the obnoxious male customers she must cope with and lonely in her sparse apartment (below), she dreams of the apparently peaceful countryside that she sees in pictures. Lem wanders in for a meal, having been sent by his tyrannical father to sell the harvest from their wheat farm in Minnesota. He becomes a regular customer as he stays in Chicago waiting for the price of wheat to rise. His friendly, courteous behavior confirms her idealization of rural life, and they fall in love. Once she arrives at the farm, however, her illusions are shattered by the father’s violent rejection and the loutish behavior of a gang hired to help with the harvest, against neither of whom Lem seems able to defend her.

As in Sunrise, City Girl creates a contrast of city and country, though on the whole the city here comes across as more oppressive than the relatively friendly treatment the couple in Sunrise receive there. Sunrise spends half the film presenting the aftermath to the couple’s reconciliation, while City Girl has a grimmer tone, and the happy ending arrives very suddenly and briefly.

According to Janet Bergstrom’s informative essay accompanying the “Murnau, Borzage and Fox” DVD boxed-set, Murnau initially wanted to film in Grandeur, a widescreen format of the day, but the budget wouldn’t allow it. (I suppose the effect might have worked, as the 70mm version of Days of Heaven demonstrates with a similar locale.) Perhaps it was just as well. Cinematographer Ernest Palmer has handled the landscapes well (top of this section) and given a distinctly documentary look to the harvest scenes.

The restored version of the film in the Fox boxed-set is excellent, but that box is long out of print. British company Eureka! has released City Girl on Blu-ray, which should look even better, available as an import on Amazon.com in the US (where it is listed as Blu-ray but is the same edition as is listed on amazon.co.uk as dual-format Blu-ray/DVD).

The French between silence and sound

René Clair has long been considered one of the directors whose early sound films were among the most imaginative and technically sophisticated. Indeed, that era was perhaps the high point of his career, with Sous les toits de Paris (1930), Le Million (1931), and À nous la liberté (1932) coming out in quick succession. The first two were made for the French subsidiary of Tobis, Films Sonores Tobis, which produced French films in its Epinay Studios. Its prosperity and technical sophistication are evident in the large sets constructed for Sous les toits.

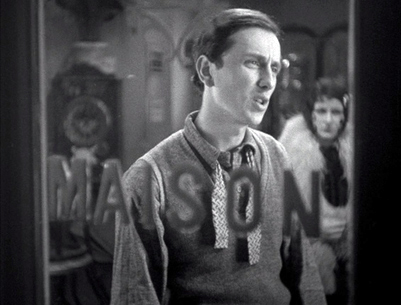

The film centers on Albert, who makes his living selling sheet music to passersby in the street and leading them in sing-alongs. In the opening scene, a small crowd joins in a song called “Sous les toits de Paris” (above). He falls in love with Pola, who is claimed by Fred, one of the many thugs played by Gaston Modot across his career. She moves in with Albert, but when he is framed for a crime committed by Fred’s gang and sent to jail, she takes up with Albert’s best friend.

This light tale gives Clair the opportunity to show off the flexibility and even flashiness of his style. The opening shot is a long crane movement descending from chimneys against the sky to the crowd singing along with Albert. Clair also uses a variety of camera angles, as in the low-angle still above.

There are several carefully lit street scenes, including this one shot in depth with both characters’ backs to the camera as Albert spots Pola outside a bar.

The climactic scene involves a tense conversation between Albert and his pal as Pola looks on. Clair shoots the two men in shot/reverse shot through glass doors, so that we do not hear them but only watch their actions and faces in a deliberate reversion to silent cinema.

Sous les toits de Paris is still in print as a DVD from The Criterion Collection. (An early issue, number 161.)

At least in the US, Julien Duvivier is not as familiar as Clair, being known mainly for Pépé le Moko, but his reputation is rightly growing. David did his part in promoting Duvivier by contributing a video analysis of his 1941 Hollywood romance Lydia on The Criterion Channel.

I don’t know whether Duvivier was inspired by L’Herbier’s L’Argent (which featured on my 1928 list) to make Au Bonheur des Dames, but there are certainly similarities between them. L’Herbier’s film was adapted from the eighteenth novel in Zola’s Rougon-Macquart series, published in 1891, but the film updated the story to the 1920s. Au Bonheur des Dames was adapted from the eleventh novel in the series (1883) and also updated. L’Argent showed the harm done by large banks, while Au Bonheur des Dames deals with the damage wrought on traditional small shops by the rise of huge, corporate-level department stores. Zola had modeled his giant store on Le Bon Marché, while Duvivier was able to shoot interiors for the store “Au Bonheur des Dames” in the Galerie Lafayette–much as L’Herbier had shot in the Paris Bourse over a weekend.

The story concerns Denise (Dita Parlo in her first French film), a naive young woman who comes to Paris expecting to work and live in her uncle’s custom-tailor shop. Instead she finds him on the verge of ruin, since the new department store is located directly across the street. He refuses to sell to Mouret, who runs the department store and wants to expand. But all the shop-owners on the block have given up, and the demolition work removing them gradually drives the tailor mad. In the meantime Denise, fascinated despite herself with the glamor of the department store, gets a job as a model there. She attracts the romantic attention of Mouret and the lecherous attention of a manager and would-be rapist (see respectively in the center and right foreground in the frame above).

Also like L’Argent, Duvivier’s film has strong elements of the Impressionist movement, which was largely over by the late 1920s. The opening portrays Denise’s reaction to the bustle of Paris after she arrives by train by a rapid montage images superimposed around her bewildered face. Later, her uncle’s growing obsession with the demolition of his neighborhood is suggested by many subjective devices, including a prismatic shot of the workers.

There are also many shots staged in depth, including a cut between Denise’s cousin’s fiancé, who has been caught sneaking out to desert her, and a reverse angle (maintaining screen direction) from behind her as he looks guiltily back.

The film was made in both sound and silent versions. Only the latter survives. I watched the Arte Video/Lobster Films version, still in print. (A Facets release in the US is out of print.) The French DVD has English subtitles, as well as a short, informative video introduction by Serge Bromberg in lieu of program notes.

The lingering legacy of World War I

During World War I, the relatively small number of films about the war naturally supported the combat, demonized the enemy, and in the US, urged people to buy War Bonds.

Given the pointlessness and widespread death and injury caused by the war, a reaction soon occurred in filmmaking within the major countries involved. Abel Gance’s J’Accuse (1919) is the earliest film displaying a bitterness about the needless bloodshed of the war, followed soon by Rex Ingram’s adaptation of Vicente Blasco Ibáñez’s 1918 bestseller, The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. The film made it onto my 1921 ten-best list. There the emphasis shifts to family members and friends of different nationalities having to fight each other (a theme that Griffith had used in The Birth of a Nation). Four Horsemen ended with progressively distant views revealing an enormous cemetery of white wooden crosses, a motif also used briefly in J’Accuse that would become common in pacifist films of the period.

The next big film was King Vidor’s The Big Parade (see my 1925 list), one of the great box-office successes of the 1920s. The filmmakers went so far as to end the film with the hero reunited with his French love, but having lost a leg in the combat. From that point, killing off some or all of the major characters became the norm of subsequent significant anti-war films. (The Big Parade does kill off the hero’s two friends-in-arms.)

The 1930s carried on the condemnation of World War I, with two of the major films on opposite sides being released in 1930. They carry on the idea introduced in The Big Parade that the ordinary soldiers fighting on the German and American sides were basically alike and could recognize each other’s humanity.

G. W. Pabst’s Westfront 1918 starts late in the war, when the German soldiers in the trenches have become thoroughly disillusioned and unspeakably weary. The first big attack on their position turns out to be friendly fire from their own artillery. (The trope of incompetent commanding officers as among the true villains in World War I–and in some case other wars–has lingered in films ever since.) One of the four German soldiers who form the group protagonist falls in love with a French barmaid in a village near the front. In the final scene, huge numbers of casualties from the latest French attack are treated at a German war hospital, with French and German patients mixed together–as the dead had been in the battle itself (see the image above).

Pabst, like other filmmakers, uses the visit home on leave as a way to emphasize the war’s impact on the home front. Karl, the most important character of the four main soldiers, returns for the first time in eighteen months only to find his wife in bed with another man. Pabst introduces the home-front section with a long line of people waiting to buy food. Karl’s mother sees him arrive but cannot greet him because after hours of waiting she had reached the front of the line.

The impressive final battle scene ends with the last of the central characters dead, and the carnage drives the lieutenant who commands them into mad raving.

The film makes a powerful statement designed to end all wars, and yet one cannot help wonder if those Germans inclined to resent the results of the Treaty of Versailles might have been inspired to a greater desire for revenge by it.

The American counterpart of Pabst’s film is Lewis Milestone’s adaptation of All Quiet on the Western Front. The 1929 translation of the German novel had become a huge bestseller in the US. Producer Carl Laemmle, who was born in Germany and visited friends and family there regularly, no doubt had a personal as well as a financial incentive to acquire the rights for Universal.

It would be easy to dismiss this big Hollywood production and ultimate Best Picture winner at the Oscars as a slick commercial venture. Certainly it has the glossy, expensive studio look that Westfront 1918 lacks, as in this scene, with its perfect three-point lighting carefully picking out each figure.

Being from a German novel, however, makes this the first significant Hollywood film to treat German soldiers sympathetically and to make them the lead characters. As in Westfront 1918, there is a tight little group of friends, three in this case, with the point-of-view figure being Paul (Lew Ayres). He is the one whom we follow on his visit home while on leave. There he visits his mother, as expected, but he also drops in on his old classroom and is disgusted to find that his teacher is glorifying war and preparing a new generation of young men to go off to become soldiers.

The opening of the film had shown Paul as a student being told of the glories of war and rushing off to sign up. This is the only one of the anti-war films I know of that portrays this sort of social indoctrination as a crucial cause of the horrors of war.

As with the other anti-war films of the 1920s and 1930s, the scenes of are extended and realistic in their depiction of trench warfare. And as in Westfront 1918, all the main characters die. At the end we see them marching off, with vast fields of white crosses superimposed.

The French produced their great anti-war films only slightly behind the Germans and Americans. Raymond Bernard’s masterful but little-known Wooden Crosses (1932), which focuses largely on French troops, is no less powerful in its depiction of trench warfare. Jean Renoir’s Grand Illusion (1938) broke with tradition by downplaying battlefield action and focusing on the senseless loss of life and liberty and the effects of class differences in warfare.

All Quiet on the Western Front has been restored and released on Blu-ray a deluxe edition with DVD and supplements or with the supplements but no DVD.

Experimental cinema in 1930

Surprisingly enough, in a weak year for commercial feature films, there was a considerable number of significant experimental films made. The standard historical accounts when I was a grad student (and probably thereafter) suggested that sound made film production too expensive for the shoestring-budgets of experimental filmmakers. Clearly, though, many of them carried on. Some of the 1930 films are silent, but by no means all. Therefore I’ve decided to devote the tenth slot in my list to a brief summary of several of them. These are in no particular order.

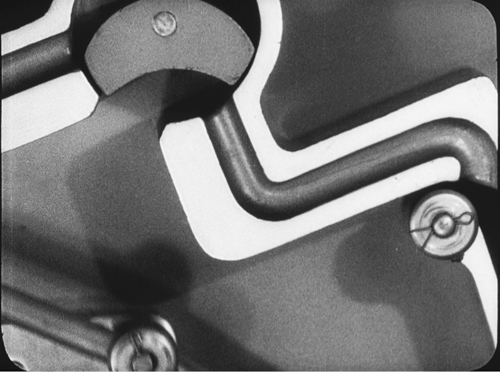

Mechanical Principles was Ralph Steiner’s next film after the better-known H2O (1929). Despite the scientific-sounding name, Mechanical Principles is an abstract film made by shooting close view of moving gears and other devices for moving parts of machines (above). The shapes and movements are engaging in themselves, but there is also, I think, a subtle and amusing progression toward more odd and even absurd-looking mechanisms. I doubt anyone would learn anything about “mechanical principles” from the film. (Included in Flicker Alley’s excellent duel Blu-ray/DVD collection, “Masterworks of American Avant-garde Experimental Film 1920-1970.” The visual quality is distinctly better than the versions on YouTube.)

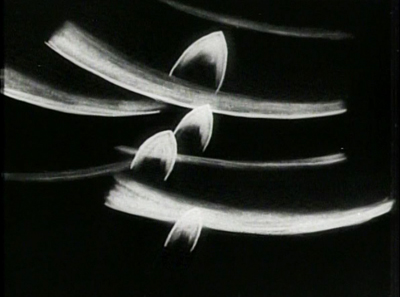

The wonderful German animator Oskar Fischinger specialized in making abstract animation in time to pieces of music. In 1930 he made Studies No. 2 through 7. YouTube contains only snippets of his films; presumably the rights holder, the Center for Visual Music, has diligently patrolled it.) Studies No. 6 and 7 are the most widely seen. I am particularly fond of Study No. 6, to “Los Verderomes fandango,” by Jacinto Guerrero (below). These shorts use a broad range of musical accompaniment. Study No. 7 is done to Brahms’s “Hungarian Dance No. 5.” I haven’t seen all of the Studies, but I assume they all use the same technique, charcoal drawings on paper. There were VHS videotapes released and a laserdisc in 1996, all long out of print. The Center for Visual Music has brought out two DVDs with selections from his films, digitally remastered and with intriguing-sounding supplements.They are sold through the CVM.

The Bridge is a silent film, adapted from the Ambrose Bierce story “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge.” Its director, Charles Vidor (né Karoly Vidor in Hungary, no relation to King Vidor), had come to the US in 1924 and worked as a chorus singer. He managed to self-finance The Bridge, which centers on a man condemned to execution as a spy. As he is being hanged by a military escort on a bridge, we see a complex combination of flashbacks to his childhood and fantasies of escape (below). The film was impressive enough to gain Vidor to gain an MGM contract to direct The Mask of Fu Manchu (1932). The high points of his long career are Cover Girl (1944) and Gilda (1946).

The Bridge is included on the fourth disc in the “Unseen Cinema” collection.

Walther Ruttmann’s Weekend (the original title is in English) is not a exactly a film, even though its subtitle is “Ein Hörfilm von Walter [sic] Ruttmann.” That roughly translates as “a radio-film,” and it was produced by the Reichsrundfunk Gesellschaft (national radio). On the DVD it is reproduced as a black screen with sound over, which one could play in projection. The list of sections given at the beginning runs: “Jazz der Arbeit / Feierabend / Fahrt ins Freie / Pastorale / Wiederbeginn der Arbeit / Jazz der Arbeit” (Jazz of Work / Quitting time / Travel in the Open Air / Pastorale / Recommencing Work / Jazz of Work). The “film” is a lively and often amusing montage of sounds, including trains, tools, engines starting, drum beats, brief snatches of dialogue, a cuckoo clock, a siren, a rooster, and so on. Its twelve-minute length is well gauged to avoid having the device wear out its welcome.

I hardly need to write anything about Dziga Vertov’s Enthusiasm: Symphony of the Donbass. For many years Vertov held his high reputation largely on the basis of Man with a Movie Camera, one of last year’s top ten. Enthusiasm was Vertov’s last Ukrainian film and apparently the first Ukrainian sound feature. Although the film’s credits emphasize that it was shot on location, including the interior of a coal mine, clearly nearly all the footage was shot silent and had a “symphony” of sounds woven together and laid over it.

The film has some of the playfulness and experimental cinematography so familiar from Man with a Movie Camera. That film is so engaging in part because it was primarily a lively look at Soviet everyday life, including movie-going. Enthusiasm, however, is far more overtly propagandistic, being largely a celebration of the early achievement of the First Five Year Plan’s coal quota in the Ukraine in four years. This was thanks to the “enthusiasts,” as the film puts it: Stakhanovites, that is, workers who did considerably more than their comrades through hard labor and efficiency. (They were named after Alexei Stakhanov, a coal miner; the movement started in the coal industry.) Some of the Soviet workers and peasants sincerely approached their work in this way, but in reality much of the achievements of the Plan were achieved through forced labor.

The restored film is included on Flicker Alley’s Blu-ray disc, “Dziga Vertov: The Man with the Movie Camera and Other Newly Restored Works.”

One of the finest experimental films of 1930 is Lázló Moholy-Nagy’s Ein Lichtspiel: Schwartz Weiss Grau (“A light play [i.e., a film]: Black White Gray”). It is derived from his constructive sculpture, Lichtrequisit einer elektrischen Bühne (“Light device for an electric stage”), which consists of many metal elements, some of them pierced with rows of holes, through which lights can be shown to create moving shadows. It later came to be known as the Light-Space Modulator. (The original is in the Busch-Reisinger Museum, Harvard.)

Moholy-Nagy made a film of the Modulator in action, with shifting solid shapes and shadows. It is sometimes hard to tell whether the camera or the device itself itself is moving.

Unfortunately no high-quality print seems to be available. Facets offers several of Moholy-Nagy’s films on separate DVDs, including Ein Lichtspiel–which is a little odd, given that it is only six and a half minutes long. (The modern soundtrack makes the object seem like a very elaborate set of wind chimes.) This DVD is probably the source of some of the better versions of the film posted on YouTube. It would be a pity to encounter the film in this way, but given the current situation, this is the best of the copies available there.

Kenneth MacPherson was co-founder of the Swiss-based Pool-Group, along with his wife, Bryher (née Annie Winifred Ellerman) and the poet, HD (Hilda Doolittle). Together they started Close-up, an important journal on international art and experimental cinema (1927-33). MacPherson made a few films, most notably the short silent feature Borderline. MacPherson was influenced by French Impressionism and Soviet Montage, and their stylistic traits are used in Borderline, including subjective camerawork and bursts of very rapid editing to convey violence or psychological stress.

The plot deals with racial and sexual tensions in a small Swiss village when a black couple comes to live there. Pete, in a genial performance by Paul Robeson, takes back his fiancée (or wife?) after she has had an affair with a white man, Thorne. Thorne remains obsessed with her, which gradually drives his neurotic, racist wife, Astrid (HD, credited as Helga Doorn) mad. Although Thorne has rented a room over a tavern owned by people sympathetic to the black couple, the scandal leads the villages to demand that Thorne be evicted, and he leaves town.

Some other experimental films made in 1930 that I didn’t think were as good as these but are still worth watching if one is particularly interested in this genre:

Francis Bruguière’s Light Rhythms (on the third disc of the Unseen Cinema set), a more low-budget attempt at something like Ein Lichtspiel, using paper cut-outs.

Luis Buñuel’s L’Âge d’or. (The BFI Blu-ray/DVD combo is out of print, although amazon.com is still selling it. Kino Lorber put out a DVD, which I haven’t seen.) I know this is considered a wonderful film by many, but I dislike it and much prefer Un chien andalou.

James Sibley Watson’s Tomatos Another Day (on Kino International’s “Avant-garde 3” set) is a pretty dreadful film, a sort of “theater of the absurd” before its time. I suspect it is a parody of a modernist play of the day. If so, and if anyone knows what play it was, please message me on Facebook and I’ll add that information. Suffice it to say that the husband, his wife, and her lover say obvious things out loud and very slowly “You are my lover,” “I am alone,” that sort of thing. Then all three start talking in dreadful puns (“Tomotos’ another day”). One might say it’s so bad, it’s good.

Sergei Eisenstein and Grigory Alexandrov co-directed Romance sentimentale, a quite uncharacteristic imitation of French Impression or city symphonies. Finally getting a chance to see it decades ago was one of the great disappointments of my life. It is available as a supplement on the Kino DVD of the restored Qué viva México.

A succinct account of Tobis-Klangfilm’s business operations can be found in Douglas Gomery’s “Tri-Ergon, Tobis-Klangfilm, and the Coming of Sound,” Cinema Journal 16, 1 (August 1976): 51-61. (Available on JSTOR.)

I have summarized the “wooden crosses” motif that is almost universal in anti-war films of the 1920s and 1930s (and occasional later films as well) in my video essay on Raymond Bernard’s Wooden Crosses on The Criterion Channel, where the film is permanently streaming.

Our friend and colleague Vance Kepley published an excellent study, In the Service of the State: The Films of Alexander Dovzhenko (University of Wisconsin Press, 1986).

January 27, 2021: Thanks to Cindy Keefer of the Center for Visual Music for kindly sending some corrections to my discussion of Oskar Fischinger:

All Quiet on the Western Front (1930)

Quality bingeing

Mon Oncle (1958)

Kristin here:

Or binging, if you prefer. Either is an acceptable spelling.

Streaming entertainment is one of the things that are saving our sanity as we sit in our homes. With the theaters closed and new movies either delayed or sent straight to streaming, movie critics, other journalists, and movie buffs are now making best-films-to-stream-during-the-pandemic lists a new and common genre across the internet.

Maybe you’ve been streaming a lot of TV series, even ones you’ve already seen, and are feeling a bit guilty about that. Maybe you’re longing for something more worthwhile to watch but wishing that that something would take up more time than your average feature film.

For those people, I offer a list of films to binge. These are either long in themselves or are split up into many parts that can be binged just like TV series. Others are stand-alones but can be grouped in meaningful ways.

My experience is that online disc orders are taking longer than usual. With Amazon prioritizing health and work-at-home supplies, Blu-rays are taking around two weeks rather than two days. (David and I, of course, count Blu-rays and streaming as part of our work-at-home requirements.) While you’re waiting, I’ll bet many of you have some of these discs on your shelves already and have always meant to make time for them. That time, lots of it, has arrived.

Serials

Many fine serials were made in the silent era, but Louis Feuillade remains the director that most of us think of first in relation to this format. His three great serials of the 1910s (not including, alas, the fine Tih Minh [1918]) are available on home video.

Fantômas (1912). 5 episodes, 337 minutes. Fantômas is available in Blu-ray and DVD from Kino Lorber. David wrote a viewer’s guide to it here.

Les Vampires (1915). 10 episodes, 417 minutes. Les Vampires is available on Blu-ray and DVD from Kino Lorber. As far as I can tell, it is streaming only on Kanopy (apart from unwatchable public domain pre-restoration prints).

Judex (1917). 12 episodes, 315 minutes. Judex is ordinarily available from Flicker Alley, though it is currently listed as out of stock. Amazon has 5 left. For maximum bingeing opportunities, watch all three serials in a row and then stretch them out with Georges Franju’s charming remake, Judex (1963) for an extra 98 minutes (it’s $2.99 to stream it on Amazon Prime).

Miss Mend (Boris Barnet, 1926). Three episodes, 235 minutes. The only American-style serial from the Soviet Union that I know of, or at least the only one easily available. I wrote about it briefly when it first came out from Flicker Alley. You can still get it from Flicker Alley or Amazon. We wrote briefly about it here.

Le Maison de mystère (Alexandre Volkoff, 1923). 10 episodes, 383 minutes. I’ve already written in some detail about this long-lost serial. It’s probably not as good as Feuillade’s best, but it’s good fun and beautifully photographed (see top of section) and acted–and long enough to require a meal break. Fans of the great Ivan Mosjoukine (as he spelled his name after emigrating from Russia to France) will especially want to see this one. Available from Flicker Alley

Berlin Alexanderplatz (Rainer Werner Fassbender, 1980) 13 episodes and an epilogue. 15 hours, 31 minutes. Back when it first came out, this was treated more as a film than a TV series. It showed in 16mm at arthouses and archives. David and I drove to Chicago to see the whole thing in batches over a single weekend at The Film Center (now the Gene Siskel Film Center). It’s available on either DVD or Blu-ray as a Criterion Collection set (#411 for you Criterion number-lovers). It’s also streaming on the Channel. Both have a batch of supplements, even the 1931 German film of the novel, so you can stretch the experience out even longer.

Silent serials may work for some families, if the kids have been introduced to silents already through the more obvious route of films with Buster Keaton, Charlie Chaplin, and the other great comics of the era. If not, families can fill their time with more recent films in episodes with continuing stories.

The serial format has had a comeback in recent decades, partly due to the influence of the first Star Wars trilogy and partly to the need for ever expanding amounts of moving-image content in the era of home-video, cable, and internet services. For those who want to binge Star Wars, you don’t need my guidance. Anyway, I gave up after the first of the recent series, the one where Adam Driver took over as the villain. (Not that I have anything against Adam Driver. It was the film.) Even daily life in a pandemic is too short for more.

The Harry Potter series. (2001-2011) Eight episodes, 990 minutes, or 16.5 hours. This series is not high art, but it’s pretty good, highly entertaining (to some, at least), and even has one episode, number three, directed by Alfonso Cuarón, HP and the Prisoner of Askaban (above). The others are HP and the Sorcerer’s Stone (or Philosopher’s Stone in the UK and elsewhere; Chris Columbus), HP and the Chamber of Secrets (Chris Columbus), HP and the Goblet of Fire (Mike Newell), HP and the Order of the Phoenix, HP and the Half-Blood Prince, HP and the Deathly Hallows: Part I, and HP and the Deathly Hallows: Part II (the last four, David Yates). These films are, of course, available in multiple versions, on disc and streaming. As far as I can tell, none of the complete boxed sets have the two last parts in 3D; those have to be purchased separately. Having seen the last film in a theater in 3D, I can say that it doesn’t seem to be one of those films that is much improved if one sees it that way (unlike Mad Max: Fury Road, in the section below).

The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings extended editions: An Unexpected Journey (2012), The Desolation of Smaug (2013), The Battle of the Five Armies (2014), The Fellowship of the Ring (2001), The Two Towers (2002), and The Return of the King (2003, above). 6 episodes, 1218 minutes, or 20 hours, 18 min. Yes, for sheer length this serial tops them all. Plus there are lots of supplements. Each part of the Hobbit films has one commentary track and a bunch of making-ofs, adding up to 40 hours, 5 1/2 minutes. This pales, however, in comparison with the LOTR extended editions, which have four commentary tracks, totaling 45 hours, 44 minutes. The making-ofs are hard to get exact figures for, but I estimate about 22 hours for all three films. That’s about 68 hours of audio and visual supplements.

To top that off, the Blu-ray set contains the three feature-length documentaries by Costa Botes: The Fellowship of the Rings: Behind the Scenes, The Two Towers: Behind the Scenes, and The Return of the King: Behind the Scenes, all adding another 5 hours, 2 1/2 minutes. (Botes’s films were also included in a “Limited Edition” reissue of the theatrical versions of the LOTR films in 2006.) In toto, if one watches every single item and listens to all the commentaries, one could escape 133 hours and 10 minutes of isolation boredom–and possibly go mad in the process. But treating the bingeing as an eight-hour-a-day job, it would come to 16 1/2 days.

All this does not include the supplements accompanying the theatrical-version discs. These are charming but more oriented toward introducing complete neophytes to the universe of Middle-earth than toward giving filmmaking information.

Series

Series, as opposed to serials, usually involve continuing characters but self-contained stories. Most of the series below could be watched out of order without suffering much. It would help to watch Mad Max first, since it’s an origin story. The Apu Trilogy should be watched in order because it’s about the central character’s stages of life. Each of the M. Hulot films bears the traces of the contemporary culture in which it is set, but one can understand each fine out of order. I saw Traffic first, in first run, and then saw the others.

Mad Max (1979), Mad Max 2, aka The Road Warrior (1981), Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome (1985), and Mad Max: Fury Road (2015) add up to 411 minutes, or 6 hours and 51 minutes. You know them, you love them–but have you ever watched them straight through? We’ve written about Fury Road (here and here). That’s a film where the 3D really does play an active role.

Jacques Tati’s Monsieur Hulot films: Mr. Hulot’s Holiday (1953), Mon Oncle (1958, see top), Play Time (1967), and Traffic (1971). They add up to 7 hours and 4 minutes. Or add his non-Hulot films, Jour de fête (1949) and Parade (1974) for just under an additional 3 hours of hilarity. You can buy all of Tati’s films at The Criterion Collection or stream them at The Criterion Channel. Throw in my “Observations on Film Art” segment on Parade for an extra 12 minutes. And check out Malcolm Turvey’s new book, Play Time: Jacques Tati and Comedic Modernism, soon to be discussed in a portmanteau books blog here.

Dr. Mabuse films plus Spione: Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler (1922), Spione (1928, frame above), The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (1933) and The Thousand Eyes of Dr. Mabuse (1960), adding up to 610 minutes, or 6 hours and 10 minutes. Few if any directors have extended a series over such a stretch of time, and the Mabuse films are quite different from each other (including having different actors play the master criminal). I throw Spione into the mix because the premise and tone are so similar to the first Mabuse film. Haghi is basically Mabuse as a master spy instead of a gambler and general creator of chaos; given that he’s played by Rudolf Klein-Rogge, who was the first Mabuse, the comparison is almost inevitable. One can almost imagine Haghi as just another of Mabuse’s disguises and it fits right into the series. I’ve linked the streaming sources to the titles above.

Kino Lorber has the restored version of Der Spieler on DVD and Blu-ray, Eureka has the restored version of Spione on DVD and Blu-ray (note: Region 2 coding) The Criterion Collection offers a DVD of Testament, and Sinister Cinema has a DVD of The 1,000 Eyes. (For those who want to dig deeper, there a Blu-ray set of all of Lang’s silents, from Kino Classics and based on the F. W. Murnau Stiftung restorations. That totals 1894 minutes, or about 31 and a half hours. I don’t know if that counts the supplements, but there are lots of them.)

Apu Trilogy: Pather Panchali (“Song of the Little Road,” but nobody calls it that, 1955), Aparajito (1956), and The World of Apu (1959). 341 minutes. Satyajit Ray’s trilogy may seem like a serial, in that it follows the life of the main character, Apu. Yet Ray had not planned a sequel until Pather Panchali achieved international success, and the films have big time gaps in between, with no dangling causes. These are three of the most beautiful, touching films ever made, and the stunning restoration from a damaged negative and other materials is little short of a miracle. If you have never seen these or saw them before the restoration, do yourself a favor and binge them. Have some tissues handy, and I don’t mean for stifling coughs and sneezes. Available on disc from The Criterion Collection and streaming on The Criterion Collection here, here, and here.

Now I briefly cede the keyboard to David for his recommendations of Hong Kong series.

Triads vs. cops, Triads vs. Triads

Infernal Affairs (2003).

There are many delightful Hong Kong series. I enjoy the silly Aces Go Places franchise (1982-1989) and the pulse-pounding Once Upon a Time in China saga (1991-1997). Alas, almost none of these installments entries are represented on streaming. I could find only the weakest OUATIC title, Once Upon a Time in China and America (1997) on Amazon Prime, Vudu, and iTunes.

If you want to go for samples, there are two diversions from the ever-lively Fong Sai-yuk series. The Legend (US title of the first entry, a bit pricy from Prime). The more reasonably priced Legend II, the US version of the second entry, has a fantastically funny martial-arts climax featuring Josephine Siao Fong-fong as Jet Li’s mom. This is available from several streamers. Older kids won’t find either one too rough, I think.

There are two outstanding series more suitable for adult bingeing. Infernal Affairs (2003-2004) was made famous by Scorsese’s remake The Departed (2006), but the original is better, and the follow-ups are loopier. The first entry offers solid, suspenseful plotting and meticulous performances by top HK stars Tony Leung Chui-wai and Andy Lau Tak-wah, supported by a rogues’ gallery of unforgettable character actors. Parts two and three spin off variations on the first one, tracing out before-and-after incidents and throwing in some quite strange narrative contortions. The whole thing provides an engrossing five and a half hours of entertainment. Available from several services.

In my book Planet Hong Kong I analyze the trilogy as an example of how directors Andrew Lau and Alan Mak Siu-fai created a more subdued thriller than is usual in their tradition. Bonus material: In the spirit of providing free stuff during the crisis, here in downloadable pdf form is my little chapter on the trilogy: Infernal Affairs interlude.

Also subdued, even subtle, is Johnnie To Kei-fung’s Election (2005) and Election 2 (aka Triad Election, 2006). These films dared to show secret gang rituals that other filmmakers shied away from. The first part plays out ruthless competition among rival Triad leaders, including strikingly unusual methods of punishing one’s adversary. The second entry, even more audacious, suggests that Hong Kong Triad power is intimately tied up with mainland Chinese gangs, backed up by political authority.

Johnnie To’s pictorialism, so feverish in The Longest Nite (1998), A Hero Never Dies (1998), The Mission (1999), and other films, gets a nice workout here as well. Infernal Affairs is agreeably moody, but the Election films are black, black noir.

The pair add up to three hours and a quarter. The first film is apparently available only on disc but the second is streaming from several sources.

Of course, to get into the real Hong Kong at-home experience, some viewers will find all these films easily and cost-free on the Darknet.

Thematic combos

Flicker Alley’s Albatros films. 5 films, 664 minutes, or 11 hours and 4 minutes. I wrote about the DVD set, “French Masterworks: Russian Émigrés in Paris 1923-1929” when it first came out. It’s still available here. The Albatros company made some of the key films of the 1920s, most of which are still too little known, including Ivan Mosjoukine’s Le brasier ardent (1923, above). If this is still a gap in your viewing of French films, here’s a chance to fill it.

Yasujiro Ozu: The Criterion Collection has released a helpful thematic grouping of some of Ozu’s early films. One is “The Silent Ozu: Three Family Comedies” (DVD and streaming), including I Was Born, but …, Tokyo Chorus, and Passing Fancy, adding up to 281 minutes. The British Film Institute has gone further along the same lines, releasing “The Gangster Films,” also three silents: Walk Cheerfully (1930), That Night’s Wife (1930), and the wonderful Dragnet Girl (1933); they add up to 259 minutes. The BFI has also put out “The Student Films,” (listed as out of stock at the moment) yet more silents: Ozu’s earliest complete surviving film, Days of Youth (1929), I Flunked, But … (1930), The Lady and the Beard (1931) , and Where Now Are the Dreams of Youth? (1932), adding up to 251 minutes.

David has recorded an entry on Ozu’s Passing Fancy for our sister series, “Observations on Film Art,” on the Criterion Channel; it should go online there sometime this year.

Or watch all the “season” films in a row: Late Spring (1949), Early Summer (1951), Early Spring ((1956), Equinox Flower (1958), Late Autumn (1960), End of Summer (1961), and An Autumn Afternoon (1962), for a grand total of 840, or 14 hours. Including An Autumn Afternoon is cheating a bit, since the original title means “The Taste of Mackerel.” Still, it’s so much like the earlier films in equating a season with a stage of life that the English title seems perfect. The early films equate the seasons with the young people, about to marry or recently married, while in the later films, and especially the last three, the seasons refer to the older generation, lending an elegiac tone to the end of Ozu’s career. David has done commentary for the DVD of An Autumn Afternoon.

All of these (except for Days of Youth) and many other Ozu films can be streamed on The Criterion Channel, which also has a bunch of supplements on this master director.

Or just watch The Criterion Channel’s Kurosawa films in chronological order, or Bresson’s or Godard’s or Bergman’s or …

Or watch all of Hideo Miyazaki’s films in chronological order, with or without the company of kids.

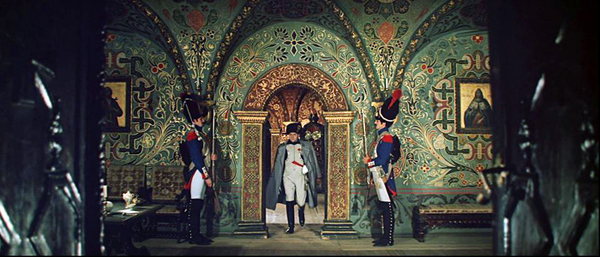

Just really long films

War and Peace (Sergei Bondarchuk, 1965-1967, above) 4 parts: 7 hours, 3 minutes, 44 seconds. I suppose this is technically a serial, since the parts were released over three years. Still, the idea presumably was that it ultimately should be seen as one film, and the running time would permit it being seen in one day fairly easily. I have not seen this restored version, only the considerably cut-down American release back when it first came out. I remember it as being quite conventional, but on a huge scale in terms of design, cinematography, and crowds of extras. Seeing it in its original version would no doubt be impressive (see above). Available on disc at The Criterion Collection and streaming on The Criterion Channel. The supplements total 175 minutes and four seconds, pushing the total up to nearly 10 hours.

Satan’s Tango (Béla Tarr, 1994) 450 minutes, or 7 hours 30 minutes. Film at Lincoln Center has just made Tarr’s epic available for streaming; you can rent it for 72 hours and support a fine institution. As to owning it, the DVDs seem to be out of print. There is, however, a Blu-ray coming from Curzon Artificial Eye on April 27 in the UK. Pre-order it here. Obviously many of us will still be stuck inside by the time it arrives. Or if you have it on the shelf and never quite got around to watching it, here’s your chance. Derek Elley’s Variety review sums up its pleasures. Our local Cinematheque has shown it twice, once in 35mm and more recently on DCP (see here, with the news buried at the bottom of the story). David reported on that first showing, and later he wrote a general entry about Tarr’s work on the occasion of having met the man himself.

Shoah (Claude Lanzmann, 1985) 550 minutes, or 9 hours and 10 minutes. The Holocaust examined through modern interviews with a broad range of people involved. Available in a restored version on disc from The Criterion Collection. It does not seem to be available currently for streaming.

Unclassifiable

Then there’s Dau (2020-), a biopic of a Soviet scientist that is perhaps the most ambitious filmmaking venture ever.

Shot on 35mm over three years in a real working town with 400 characters played by actors who remained in character and costume round the clock the whole time. Few have seen these, though two showed at the Berlin festival this year. We haven’t seen them but plan to give it a go, since they have just shown up online. Here’s a helpful summary of the project. At the Dau Cinema website, you can stream the first two films for $3 each: Dau. Natasha (2:17:53) and Dau. Degeneration, (6:09:06) adding up to 8 hours and 27 minutes. Twelve more films are announced for future release, with no timings given. Clearly not suitable for family viewing.

I have not attempted to add up all these timings, but if you can track most of them down, they might get you through much of the isolation period. Stay safe!

Election (2005).

The ten best films of … 1929

Lucky Star

Kristin here:

As 2019 fades away, it’s time once more to look back ninety years at some great classics. This series started somewhat by accident, when we wanted to celebrate the pivotal year 1917. That was when the stylistics of the Classical Hollywood filmmaking system, which had been slowly explored for several years, finally clicked into place and became the norm in the American studios.

After that, our series became a regular and surprisingly popular feature. The point is partly just to have some fun and partly to call attention to great films that have remained obscure and/or difficult to see.

For past entries, see: 1917, 1918, 1919, 1920, 1921, 1922, 1923, 1924, 1925, 1926, 1927, and 1928.

After the riches of the 1920s silent film, 1929 stands out as an anomalous year. The transition to sound was under way internationally, but different countries proceeded at different paces. The new technology often was not amenable to maintaining the freedom of cinematographic and editorial style achieved during the height of the silent cinema. There are arguably not as many indisputable masterpieces from this year as from previous ones–but there are some.

Oddly enough, truly major films from this year seem to have suffered a great deal from a lack of access, both in distribution of prints and release of good (or even any) copies on home-video formats. In part I want to draw attention to the shocking neglect of some great movies.

The list is dominated by Hollywood and especially the USSR, for opposite reasons. The American studios were well into sound production, and some of the top directors found tactics for using the new technique in imaginative ways.

In the USSR, on the other hand, silents reigned. Moreover, the great directors were not lured away to work in America, as so many European filmmakers were. (For example, Murnau’s career was nearly over, and he released no films in 1929.) Thanks to them, the golden age of silent cinema continued on.

A great year for the Soviet Montage movement

The General Line (aka Old and New, dir. Sergei Eisenstein)

The General Line is probably the least of Eisenstein’s four silent features. The earlier films were all set before or on the very day of the 1917 Soviet Revolution, and they all have a vigor and a sense of political fervor that The General Line can’t quite match. Instead, it’s about policy, specifically the portion of the First Five-Year Plan devoted to the collectivization of private farms. Eisenstein adopts an odd tactic for dramatizing the need for such a drastic overhaul of life in the countryside. He presents a single protagonist for the first time, Marfa, a poor peasant working her land alone and without a horse for the plowing.

She becomes convinced that the answer to her and her neighbors’ plight is to create a cooperative dairy for the village. But throughout, Marfa has few allies and encounters opposition from both the local wealthy Kulaks and the poor peasants, who are portrayed as ignorant, greedy, and even violent in their determination to retain full ownership of their farms and livestock. Marfa is too weak to succeed without the support of the local government agronomist and a few like-minded farmers. The task of collectivization seems too overwhelmingly difficult to ever succeed.