Archive for the 'National cinemas: France' Category

The trim, tight movie: Three variants at Vancouver

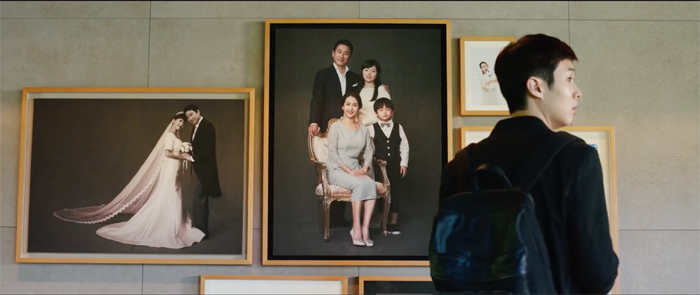

Parasite (2019).

DB here:

As a student of storytelling, I recognize that we can enjoy loose, episodic plots. But I also admire the shrewd craft of constructing a movie that develops a situation in precise, logical, yet surprising ways. Things may be resolved neatly, or not, but the satisfaction comes from the way that characters pursuing goals create conflicts, overcome obstacles, and change (or not) in the course of the action. American studio cinema developed its own version of this in what Kristin and I have called “classical Hollywood” plotting. Other countries have borrowed that model, adapting it to new needs but still keeping the storytelling trim and tight.

Three films on display at this year’s Vancouver International Film Festival illustrate some options. All have won acclaim at other festivals and constitute A-productions in their local industries. I enjoyed all of them, and I liked learning how broad principles of narrative construction can be treated in significantly different ways.

Storming the basilica

François Ozon’s By the Grace of God, a prizewinner at Berlin this year, turns Spotlight (2015) inside out. The American film follows the investigation of a news team bringing priestly pedophilia to light; it’s a detective story, with the victims serving as witnesses to the crime. By the Grace of God concentrates on the victims’ search for justice, and finds an unusual structure to give each one due weight.

The film is based on a real case in Lyon. The film starts with businessman Alexandre Guérin accusing Father Preynat of abusing him as a child. Surprisingly, Preynat admits he did the deed, so there’s no mystery to be solved. With the statute of limitations expired, the Church authorities decline to punish Preynat. He’s kept in service, and his duties still associate him with children. The only thing that worries Cardinal Barbarin is that Preynat didn’t apologize when Alexandre confronted him.

A pious Catholic, Alexandre trusts that if he appeals high enough in the Church hierarchy (even up to the Pope), some action will be taken. He is rudely awakened to the cynical willingness of Barbarin to stall and cast a smokescreen over the case. Alexandre decides to file a legal complaint and to find other victims to join him.

At this point, Ozon’s script takes an intriguing turn. The plot drops Alexandre and introduces us to another victim, François Debord, who is a fairly militant atheist. Investigating Alexandre’s charges, the police call on François’s parents. He told them of the abuse at the time, but they pressured him to stay quiet. Now he embarks on a crusade to find other victims to speak out. For some of them, the statute of limitations may not have expired.

Alexandre becomes a minor player in this stretch of the film, meeting François occasionally to plan strategy, but François is the motor of the action. His zeal leads him to yet another victim, Emmanuel Thomassin. We now follow him and learn how his life has been damaged quite severely by Preynat’s abuse.

Eventually the three men find more victims willing to go public, and by cooperating they confront the Church’s coverup.

With three sections each lasting 45-50 minutes, Ozon has mounted a block-construction plot (although without explicit chaptering). He has compared it to a relay race, with the story impulse passed like a baton from one character to another. And each phase of the action raises the stakes: growing proof of the Church’s malfeasance, a broader survey of the consequences of the crimes.

Ozon has also said that he tried to distinguish each of his three protagonists’ sections stylistically. Alexandre’s phase of action has highly economical narration, using the exchange of letters and emails (read in voice-over) to move the action swiftly, forcing us to keep up at every moment. When the action shifts to the flamboyant, web-savvy François, the emphasis falls on building online support for an organization. Emmanuel’s painful story is treated with more intimacy and empathy; the other men have overcome their childhood traumas and have buoyant families, but Emmanuel is adrift.

By the Grace of God has the carpentered solidity of Ozon’s Frantz (2016). If we can say that the French “Tradition of Quality” of the 1940s and 1950s persists today, it’s surely here in this taut, elegant piece of storytelling.

City on fire

Stylistically, Les Misérables doesn’t look as sleek and controlled as Ozon’s film. It’s shot in the free-camera style that’s now common throughout the world: handheld shots, fast cutting, tight framing on faces, lots of panning to follow the action. When cops brace three women on the street we get a rapid-fire exchange in the manner of Homicide: Life on the Streets.

Although we’re basically on one side of the confrontation, the cutting is somewhat freer than in classic continuity, as the above shot of Stéphane indicates. To emphasize the quasi-sexual gesture of Chris checking the young woman’s fingers for the smell of pot, the editing jumps the line before returning to the main setup.

Les Misérables, directed by Ladj Ly, is not quite as pure an example of the free-camera approach as Young Ahmed, (also shown at VIFF) because it affords a greater degree of “camera ubiquity.” It crosscuts among lines of action, and it relies on reaction shots that the Dardennes avoid. Still, the purpose is to immerse us, smashmouth fashion, in each scene’s conflict.

And there’s plenty of conflict. Stéphane Ruiz has joined a team of tough cops patrolling an impoverished Parisian suburb teeming with immigrants. To keep things under control Chris, the team leader, has formed alliances with drug gangs and the boss of the territory. Gwada, a Muslim cop, backs Chris loyally.

The main action, which consumes around 24 hours, shows Stéphane trying to bring a measure of humanity to the confrontations between his unit and the local residents. A petty crime escalates into a burst of police brutality, captured on video by a boy’s drone. The second half of the film puts the cops in conflict with one another and an increasingly outraged community ready to take on both the police and the gang leaders.

Ly has made short films and web videos, and while growing up in the banlieue projects he documented police actions.

For five years I filmed everything that went on in my neighborhood, particularly the cops. The minute they’d turn up, I’d grab my camera and film them, until the day I filmed a real police blunder.

Ly filmed the 2005 riots as well (365 Days in Montfermell), as part of the filmmaking collective Kourtrajmé. Les Misérables is called that partly because this is the district where Hugo wrote his masterpiece. “I wanted to show the incredible diversity of these neighborhoods. I still live there: it’s my life and I love filming there. It’s my set!” In 2018 Ly established a filmmaking school in Montfermell.

Although Ly comes from the world of documentary, he has a shrewd sense of fictional plotting. A prologue shows little Issa among thousands of Parisians celebrating France’s World Cup victory (above). It’s an image of diversity within national unity, but also a bit of narrative priming that makes us sympathetic to the boy. The rising tension of the action, from a childish prank through increasingly horrific scenes (one in a lion’s cage had me trembling) to a final cataclysm, is carefully constructed out of a series of misunderstandings, brutal decisions, overreactions, and desperate survival maneuvers.

There’s solid motivation and foreshadowing. The drone is established early as the all-seeing eye of the projects, steered by the withdrawn boy Buzz. Stéphane has reluctantly transferred to the Parisian police from the provinces because he wants to be near his son, in the custody of his ex-wife. This information prepares us for his sympathetic gestures toward the children of the projects. And just before the climax, Ly’s script gives us a pressurized nighttime pause, a sequence that cuts among all the adults we’ve seen trying to adjust to the day’s turmoil. Next day all hell will break loose.

Les Misérables shared the Jury Prize at Cannes last May with another VIFF entry, Bacunau. (Comments on this coming soon.) In the US it will be distributed, who knows how, by Amazon.

Class struggles

Viewers of Memories of Murder (2003), The Host (2006), and Mother (2009; also here) know that Bong Joon-ho has a fine hand with mystery, suspense, and abrupt plot twists. His skill is on full display in Parasite, Palme d’or winner in Cannes and already considered one of the most striking films of 2019.

As suits the Age of Inequality, the action centers on two families. The Kims live in a crammed basement and struggle to get by. When the son Ki-woo gets a job tutoring the daughter of the rich Park family, he schemes to insert all his family members into the household. (This recalls the stratagems of the play and film Kind Lady.) The Kims’ adroit manipulation of the Parks, especially the insecure helicopter mom, provides mordant comedy. But in a long central scene, the Kims’ scam starts to unravel. They’re shocked to discover what actually goes on in the splendid mansion they’ve taken over.

Bong’s skill in shooting, staging, and composition seems effortless. Neither as academic as Ozon or as nervous as Ly, his deliberate style makes every sequence build to a neat point. The contrast between the Park house, perched high on a hill, and the Kims’ basement apartment, is echoed in vertical camera movements that carry us up and down through locales. (Here, in more instances than one, the poor live underground.) Parasite‘s opening camera setup, a view of the street through the Kims’ window, recurs at various points to mark stages of the action. Here nighttime violence erupts in the street outside.

The Kims’ barred view contrasts with the spacious picture window at the Park mansion. Fussy as ever, Bong places a comparable shot of the Kim window at the very end.

Bong plants significant motifs through the film. He forgets nothing. Cub scouts, Morse code, peach allergies, and the smell of poverty pay off in comedy while supplying thematic resonance. The parallels between the married couples are enhanced by the introduction of another husband and wife who have launched their own desperate scheme. The climax, an orgy of rich folks’ complacency, brings all together in a shocking but not ultimately surprising confrontation.

I had almost called this entry “The well-made movie,” indicating not only my praise for the films but also their kinship with the dramatic tradition of the “well-made play” (pièce bien faite). That was one powerful set of principles for plot-building. If you construe that form narrowly (as the Wikipedia entry does), these films don’t completely fit it. I think that Ibsen, Shaw, and those who followed owe more to that form than is generally admitted.

In any case, the impulse toward tight construction, full motivation of characters’ actions (usually guided by a goal), and a rising arc of conflict leading to a decisive climax–these design features, so manifest in the well-made play, have carried over to the cinema since the rise of the feature film in the 1910s.

Today’s films have a look and feel that seem of our moment, but their underlying “engineering” principles are surprisingly indebted to a long-running tradition. Those principles can be deployed, revised, and reversed in a great many ways–as these three films show.

We thank Alan Franey, PoChu Auyeung, Jenny Lee Craig, Mikaela Joy Asfour, and their colleagues at VIFF for all their kind assistance. Thanks as well to Bob Davis, Shelly Kraicer, Maggie Lee, and Tom Charity for invigorating conversations about movies.

For more on the general principles of “classical” construction, see this entry on The Wolf of Wall Street. In our book The Classical Hollywood Cinema Kristin traces some literary and dramatic sources of the format.

On the “free-camera” shooting style, see our blog entry on Toni Erdmann (viewed at VIFF back in 2016). We discuss the emergence of the technique in Chapter 25 of the fourth edition of Film History: An Introduction.

By the Grace of God (2019).

Telling the big story: Network narratives at Venice 2019

The Laundromat (2019).

DB here:

Every now and then I wonder whether network narratives, to revert to the term I coined a while back, have faded from the scene. Although there are some examples earlier in film history, that storytelling model had a sustained burst after Altman popularized it in Nashville (1975). Other filmmakers took it up, especially in the 1990s (Before the Rain, Exotica, Go, Pulp Fiction, etc.) and the 2000s (Babel, Dog Days, Love Actually). I don’t seem to see so many nowadays, and the almost universal loathing greeting Life Itself (2018) might seem to indicate that a tale relying on remote connections and unexpected convergences had run its course.

Surprising, then, to see three items at Venice that rely to a degree on the network narrative format. Each is based on a nonfiction book aiming to reveal the dynamics of a large-scale process. In each film, process becomes a framework for personal stories and converging fates.

Wasps in the Caribbean

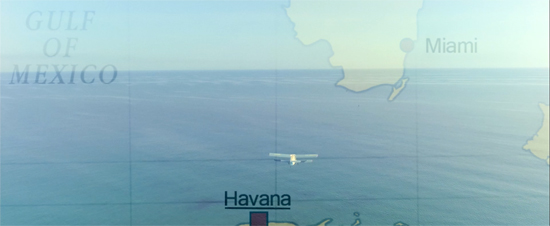

Olivier Assayas’s Wasp Network isn’t as far-reaching as the title implies. It concentrates on two couples and one individual caught up in 1990s spying. When René Gonzales, a pilot, defects to Florida, he seems to be seeking freedom and a new life working with Cuban exiles to destabilize Castro’s regime. Branded a traitor, he leaves behind a wife and daughter who must bear social opprobrium. Actually, he is a Cuban agent, part of the “Wasp Network” that will infiltrate the anti-Castro forces.

Another exile, Juan Pablo Roque, works with the Network, but he is also leading a double life–one quite different from René’s. Just as René’s sacrifice wrecks his relation with his family, the headstrong Juan Pablo jeopardizes his relation to his lover Ana Margarita. Both men are linked to Gerardo Hernandez, who coordinates the Network.

As in most spy stories, we’re led to discover double agents and surprise alliances, as well as the conventional emphasis on the personal cost of espionage. As the film goes along, that emphasis becomes stronger; scenes tracing the tactics of the anti-Castro forces (such as invading Cuban airspace to drop leaflets) give way to long confrontations between couples and the efforts of Rene’s wife Olga to unite with him in the US.

Because network plots need to fan out across many characters, filmmakers often break up the linearity of time. In Wasp Network, the reunion of the two major defectors, Juan Pablo and René, is followed by a passionate scene of Olga being defeated by Cuban bureaucracy. Abruptly the plot skips back four years to introduce Gerardo, and his career as a double agent is summarized. A montage, complete with a narrator’s voice-over, links the three men in the years 1990-1992. Then, back in the present, Gerardo meets with Olga to reveal that René is a patriot, not a traitor.

Visually, the film is surprisingly ordinary, I thought, sort of standard TV. If you like over-the-shoulder shot/reverse shot, there’s plenty here for you.

Assayas garnishes his reverse angles with alternating push-ins, a technique that has become a bit hackneyed since John McTiernan’s skillful use of it.

The film compels some interest by virtue of its origins. Based on the FBI case against the “Cuban Five” and the book The Last Soldiers of the Cold War, it employs vintage broadcast news coverage cut in for expository purposes. I had known almost nothing of this historical episode, and thanks to the cooperation of Cuban authorities Assayas benefits from showing a story we Americans seldom see. Still, by concentrating on only a few characters and having them played by Édgar Ramírez, Penélope Cruz, and Gael García Bernal, whose presence demands extensive scenes, the larger dynamic of the Wasp Network fades into the background. Despite its title, maybe it’s only a borderline case of a network narrative.

Coke ZeroZeroZero

ZeroZeroZero is also based on journalistic reportage, in this case Roberto Saviano’s book of the same title. (An earlier Saviano true-crime investigation is the source of the 2008 film Gomorrah, another network narrative.) The subtitle of his book–Look at Cocaine and All You See Is Powder. Look Through Cocaine and You See the World–suggests the vast ambition of his project. From the book Sky, CanalPlus, and Amazon Prime have developed an eight-part series to be broadcast and streamed in 2020.

Since I’m not the world’s biggest TV consumer, I wasn’t interested until I read the presskit, which promises something sweeping.

The series follows the journey of a cocaine shipment from the moment a powerful cartel of Italian criminals decides to buy it until the cargo is delivered and paid for. Through its characters’ stories, the series explains the mechanisms by which the illegal economy becomes part of the legal economy and how both are linked to a ruthless logic of power and control affecting people’s lives and relationships.

The prospect of following a coke-packed container as it passes through various hands appealed to me. I enjoy circulating-object plots like Winchester 73 and The Red Violin, as well as those 1920s Soviet Constructivist “biographies of things” (such as Ilya Ehrenberg’s Life of the Automobile).

ZeroZeroZero, though, isn’t quite that sort of thing. Judging by the first and second episodes, the only ones screened at Venice, this will be more conventional. The plot shifts among dramas within groups of stakeholders in the shipment. We see the power struggle in an Italian crime family, with a son aiming to usurp his grandfather. There’s another family drama in New Orleans, where a ruthless shipping-company owner insists, against his son’s and daughter’s resistance, on booking the cargo. In Mexico, a corrupt special forces sergeant works behind the scenes to assure that the shipment will not be disturbed.

The narration cuts among these storylines until, at the end of episode 2, the cargo embarks on the seas. Doubtless the remaining episodes will ramify into other story lines, but I’d expect at least the Italian and American ones to be on tap throughout–if only to maintain the interest of streamers’ European and US audiences.

The film was directed and co-written by Stefano Sollima, who has done several TV dramas as well as the feature film Sicario–Day of the Soldado. ZeroZeroZero certainly had a higher-gloss look than Wasp Network, with dramatic lighting and elaborate action scenes. One of these, a police attack on the big meeting of the stakeholders, is replayed from different character viewpoints in the two episodes. Like Wasp Network, ZeroZeroZero amplifies its expanding network through time-shifting, and this attack is revealed to be a node, a point of convergence among the three main groups of characters. Given current TV’s fascination with scrambled time schemes, I’d expect other nodes and replays to emerge in the course of the series.

Capitals of capital

Eisenstein planned to make a film of Marx’s Capital. He would have used his montage editing methods to survey an economic system–without benefit of individualized protagonists. In The Laundromat Stephen Soderbergh has tried to do something akin to this, but like most filmmakers he’s obliged to personalize his drama (as he did in Traffic and Contagion). Soderbergh has compared the film to Dr. Strangelove, largely because of the need to make a devastating situation entertaining. But I think his film recalls Strangelove as well in its emphasis on villains who get caught up in the insanely complicated system they create.

Mossack Fonseca was a law firm in Panama that specialized in tax evasion. It registered over 300,000 companies, many of which were shell entities that enabled money laundering and fraud. The firm had subsidiaries in the Bahamas, Hong Kong, Switzerland, and other countries. In 2016, German investigative journalists published 11.5 million internal documents known as the Panama Papers, mostly centering on Mossack Fonseca. As the journalists explain:

Clients can buy an anonymous company for as little as USD 1,000. However, at this price it is just an empty shell. For an extra fee, Mossack Fonseca provides a sham director and, if desired, conceals the company’s true shareholder. The result is an offshore company whose true purpose and ownership structure is indecipherable from the outside.

Despite its vast scale, the firm represented at most ten percent of the global market of offshore finagling.

Tax havens and shell companies are more or less legal. What brought down the company was the breach of confidentiality. In addition, the possibility of fraud hovered over the big names revealed as beneficiaries. Politicians throughout Europe and China were named, as were filmmakers Jackie Chan and Pedro Almodóvar. International villains associated with Bashar al-Assad and Vladimir Putin moved money through Mossack Fonseca; a Russian cellist had holdings of $2 billion. After the leaks, the rich couldn’t trust Mossack Fonseca to keep their secrets.

Building on Jake Bernstein’s book Secrecy World, Soderbergh and screenwriter Scott Z. Burns have concocted a sweeping tale of how the rich are very, very, very different from you and me. But in scale, the network they’re surveying dwarfs the Wasps and the voyage of a coke shipment. How do you convey the vastness of an alternative financial system?

The film’s pop-Brechtian mode of presentation will earn comparisons to The Big Short, but here instead of one-off celebrity tutors (Margot Robbie, Anthony Bourdain) we get the chattering rogues themselves, Jürgen Mossack (Gary Oldman) and Ramón Fonseca (Antonio Banderas). Their to-camera accounts of “fairy tales that actually happened” settle into a block construction, five chapters “based on actual secrets.”

The first chapter title, “The Meek Are Screwed,” provides an emblematic case of how the little people are connected with this network of virtual money. Chief among those Meek is Ellen Martin (Meryl Streep), whose husband Joe is drowned when a tour boat capsizes.

Hoping to have her grief assuaged by an insurance settlement, she learns that one isn’t forthcoming because the boat company bought a worthless policy from a shell company. The film’s first two chapters follow her efforts to find someone responsible. She finally tracks down a fraudster named Boncamper, a Mossack Fonseca figurehead who has grown rich (and accumulated two families) simply by signing thousands of documents.

Having shown how the shell-company shuffle affects ordinary folks, the film moves on to the high and mighty. One chapter traces the backstory of the company, another shows how an extraordinarily rich family uses the system to one-up each other, and a final chapter depicts murder among the Chinese plutocracy. The fourth block, illustrating the lesson of “Bribery 101,” is especially juicy in showing a father using bearer bonds to force his daughter to keep silent about his extramarital affair. As Marx and Eisenstein would expect, economic relations seep into personal ones. Bribery is all in the family.

The Laundromat’s breezy, self-righteous impresarios cast a comic tone over everything. Even the murder doesn’t seem awful, considering the victim’s own corruption. Only at the end does indignation emerge in a twist. Ellen, almost forgotten for the last half-hour, reappears in a new guise and takes over the narration from the villains. An agitprop ending reminds us that the capital of money laundering may well be the US, where Nevada, Wyoming, and above all Delaware play a role comparable to the Caribbean. Soderbergh and Burns (who confess to having offshore stashes themselves) end by firmly snagging their American audience in the colossal spiderwebs of global capital.

Nearly every narrative involves a social network of some size, even if it’s only a family. The most thoroughgoing network plots provide us roughly equal attachments to many viewpoints. The film demotes individual protagonists, in favor of revealing x degrees of separation among several individuals. Wasp Network, ZeroZeroZero, and The Laundromat don’t have the complexity of the network narratives of earlier years, but they serve to remind us that the network schema can be tweaked to suit the needs of particular creative projects.

Thanks to Paolo Baratta and Alberto Barbera for another fine festival, and to Peter Cowie for his invitation to participate in the College Cinema program. We also appreciate the kind assistance of Michela Lazzarin and Jasna Zoranovich for helping us before and during our stay.

For more on network narratives, see Chapter 7, “Mutual Friends and Chronologies of Chance,” in Poetics of Cinema. Jeff Smith considers Once Upon a Time . . . in Hollywood as a network narrative, and earlier entries (such as here and here) develop the idea as well.

To go beyond our Venice 2019 blogs, check out our Instagram page.

ZeroZeroZero (2020).

Finding a form: The College Cinema at the Venice International Film Festival

This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (Lemagang Jeremiah Mosese, 2019).

DB here:

For the third year I participated in the Mostra’s College Cinema, a wonderful program that funds and guides three features by up-and-coming directors and producers. (Details are here.) I’ve reported on the earlier sessions here and here.

This year my developing reaction to the trio of features was governed by what Kristin and I did the day before our panel. We saw two superb classics: Bertolucci’s The Spider’s Stratagem (1970) and István Gaál’s Current (1964). They reminded me of what ambitious filmmaking was like before the arrival of screenplay manuals dictating character arcs and first-act turning points.

In those days, a filmmaker was likely to find a distinct, even unique form for a story. The filmmaker would design the film organically, creating a large-scale shape that would let technique and dramatic structure build in relation to each other, not in accord with standard formulas.

Coupling via monitor

A good example is The End of Love, directed by Karen Ben Rafael. The Israeli Yuval and the French woman Julie have a child. He waits in Israel for a new visa, while Julie must manage child care under the pressures of her job in an architecture firm. Each begins to suspect the other of infidelity, and their families in each country add to the tension.

So much for a traditional “relationship” movie, whose ups and downs could have been presented in a standard way. But Rafael and her co-screenwriter Elise Benroubi hit upon a fresh way to trace the couple’s conflicts. Yuval and Julie are keeping in touch via a Skype-like video service, and we are completely confined to their exchanges in this medium. We see only what they see, in a series of to-camera shot/reverse-shots.

Some recent genre films have been “monitor movies,” like Paranormal Activity 4 (2012), Chronicle (2012), Unfriended (2014), and Searching (2018). But these exploit the device for suspense and horror. The End of Love lets the conditions of video communication structure the ongoing drama. A teasing opening suggests that the camera is lying in bed between the couple as they caress themselves; the next scene–a remarkable shot in itself (above)–reveals that video is their channel of communication.

As the film goes along, tensions between Yuval and Julie are presented as much through the mechanics of video exchanges as through the actors’ (very persuasive) performances. Unanswered calls signal a growing indifference. A mysterious shot wobbling through a dance club suggests either a phone accidentally turned on or a loud, defiant assault on the other person. I was especially taken by the moments when we get slight change of eyelines as characters look from the camera to study the display image of the other person.

The End of Love triggers a lot of ideas about how modern couples are led to expect that technology can overcome family problems. Being always online, always “in touch,” doesn’t mean that you’re engaging authentically with someone else. For all its power, the video hookup in the film creates an illusory intimacy, and its glitches stand for the aggravations, little and big, that come with physical separation. This thematic implication grows organically out of the creative decision to confine our viewpoint to what the camera can see and hear, but not heal.

Social drama into community myth

Another vigorous example of letting the material summon up the film’s form is This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection. Directed, written, and edited by Lemogang Jeremiah Mosese, it’s a poetic work that develops its imagery out of a dramatic situation.

The eighty-year-old Mantoa learns that her only surviving relation, her grandson, has died in a mining accident. After being consoled by her priest and the local choir, Mantoa tries to restabilize her life. But when she learns that her village is to be flooded for a dam project, she vows to save the bodies in the local cemetery–and to prepare her own grave.

This tale, set in Lesotho, is framed by a narrator telling us about her and her community. He sits in a blast of yellow light adjacent to a pool hall, and at intervals the story action pauses for his comments. The film takes its time–about 300 shots in two hours–to dwell on the details of her daily routine, such as the portable radio hanging from the wall, or Mantoa’s changing outfits.

But there are also more surreal images, such as Mantoa on a burned-out bedspring being slowly surrounded by sheep. The community that eventually supports her is presented as an almost abstract force, as are the out-of-focus government workers slowly hacking away at the perimeter of the village. The climax of the film makes powerful use of those figures as Mantoa confronts them in her boldest provocation of all.

Again a familiar situation–a tenacious elder tries to halt the destruction of a community (think Wild River)–is given fresh life through formal elaboration. Out of a primal conflict, Mosese generates a work of mythic dimensions. He does it through lustrous visuals, an evocative soundtrack, and a character who creates a legend that will live for generations.

Town and country

If The End of Love traces a jagged decline in a relationship, and This Is Not a Burial lifts a social conflict into spirituality, Lessons of Love finds another structure, this one aiming to express the inarticulate feelings of a man stuck in a situation. It’s a circle.

Yuri toils on his father’s farm, while his younger brother and sister try to avoid their responsibilities. Stolid, silent, and glum, Yuri harbors a good deal of anger, occasionally expressed in road rage. He relates to the world almost completely through physical contact.

Director Chiara Compara and her co-screenwriter Lorenzo Faggi start from a classic pattern: the migration of an innocent from the countryside to the city. This pattern is refreshed through a strategy going back to Neorealism: the insistence on the physicality of daily routines. A prolonged moment of Yuri tuning a radio recalls the famous scene of the maid’s morning ritual in Umberto D.

The early stretches of Lessons of Love stress the demands of farm work. The first shot is of a milk can, and soon we see logging, veterinary inspections, the purchase of a cow, and the dull evening meal. But we also get a sense of Yuri’s longing when he soberly eats during a TV love scene, and soon enough he’s visiting a strip club, watching as impassively as he did the TV show.

Through a tissue of routines, Yuri’s vague thoughts about escape emerge, and soon he is considering buying cowboy boots, dating Agata, and getting a construction job in town. That’s when the circular structure gets initiated, and new routines replace the old ones. Again, the details of hard labor aren’t stinted, and Yuri is challenged to break out of his smoldering solitude. Can a man who punches and embraces his favorite cow, and who furiously whacks a driver-side mirror, ever learn to talk to a woman who’s kind to him? The last shot of the film, discreetly echoing the first, provides the answer.

A fraught love affair, a defiant elder speaking up for a community’s heritage, and a lonely, locked-in man are familiar enough points of departure for a film. But these three College features offer fresh, rigorous treatment of their stories. Three acts and vulnerable-but-relatable heroes and heroines? Not necessary! There are other ways to go, as young filmmakers can show us.

Thanks as usual to Peter Cowie for inviting me to join the College Cinema panel, and to Savina Neirotti, the Head of the program. Thanks as well to other participants for lively conversation: Chaz Ebert, Glenn Kenny, Mick LaSalle, Michael Phillips, and Stephanie Zacharek. As ever, we appreciate the kind assistance of Michela Lazzarin and Jasna Zoranovich for helping us before and during our stay.

Glenn has a fine appreciation of the College films on rogerebert.com. He too was reminded of Wild River, but no surprise as we’re both nerds in this (and other) respects.

The End of Love (Karen Ben Rafael, 2019).

Two more classics from Flicker Alley

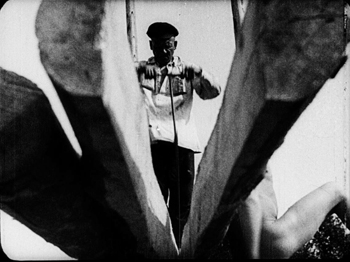

Fragment of an Empire (1928).

Kristin here:

Our friends at Flicker Alley have once again provided access to major works of silent cinema with two Blu-ray releases: Marcel L’Herbier’s L’Argent (1928) and Fridrikh Ermler’s Fragment of an Empire (1929).

Fragment of an Empire

When I was in graduate school, back in the 1970s, Ermler’s Fragment of an Empire (more accurately translated as “Remnant of an Empire”) was considered one of the major examples of Soviet Montage cinema. Its place in the canon seems to have faded since then, but this Blu-ray should restore its reputation.

Earlier prints of its were dicey. Its most famous scene was one in which the protagonist approaches a life-size crucifix at night on a battlefield and discovers that the head has been fitted with a gas-mask. David remembers seeing a print in which this image was present. I remember watching the film, expecting to see this image and being disappointed that it was not there. (I expected it because most histories of cinema that mentioned Fragment would use a production still of the crucifix.) Why the shots of the crucifix were removed is not clear, though presumably in countries where religious groups had some say in censorship matters, they were removed as blasphemous.

Peter Bagrov, formerly of the Gosfilmofond archive in Russia and now Curator of the Moving Image Department at George Eastman Museum, was centrally involved in the film’s restoration and provides the essays in the accompanying booklet. According to him, nine prints of the film from archives around the world were examined for this restoration. Only two of them contained the gas-mask Christ shots, one of them being the Museum of Modern Art’s distribution print. David probably saw that. I saw another version; I don’t recall when or where. Bagrov suggests that some prints that circulated as the “canonical” version of the film were in fact an abridged, simplified version made at the time for circulation to the uneducated rural population. Now we can all see something very close to the full original 1929 copies.

The film’s title refers to Filimonov, who is initially suffering from amnesia and working as a hired hand for a peasant woman at a remote stop on a rail line. Seeing a woman on a passing train triggers his memory, and he realizes that she is his wife and that he was a non-commissioned officer during the World War I. Going home to St. Petersburg, now Leningrad, he is shocked by the modern architecture and short skirts, as well as the fact that the owner of the textile factory where he had worked is no longer the master there. He gets a job at the same factory. Who, he repeatedly asks his fellow workers, is the master?

Fragment of an Empire falls into the common Soviet plot pattern of following a character who at first resists or ignores the revolutionary changes in the USSR but comes to understand and support them by the end. It also falls into the “Rip Van Winkle” pattern of a character who, either through amnesia or some fantastical time warp, is thrown into a society that has moved ahead without him or her. It’s a convenient way of defamiliarizing, as the Russian Formalists would say, that new society.

The opening third or so of the film is its most impressive portion. Several early segments take place at night on the bleak, flat land around the train tracks. Ermler makes impressive use of the new arc searchlights that had been developed for surveillance during the war. These intensely bright lamps made shooting in exteriors at night practical for the first time. Ermler created stark, white strips of light against pitch black, picking out individuals from a great distance (see top). The effect at times resembles some of the abstract experimental shorts of the 1920s.

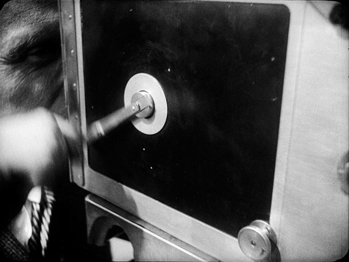

In the opening scene, the bodies of soldiers who have died of typhus are heaped on a train platform to be buried. The peasant woman orders Filimonov to strip them of their boots, but while doing so he finds one wounded soldier still barely alive and saves him. The second sequence has Filimonov spotting his wife and beginning to piece together his memories. Back at home, more reminders trigger a series of quick flashbacks: a sewing-machine’s crank leads to a machine-gun firing, a rolling spool recalls wheels of trains and tanks. A somewhat more extended flashback involves a tank advancing on a soldier as he prays and begs for help from the gas-mask-outfitted crucifix before being crushed–a traumatic scene presumably witnessed by Filimonov, though he is not shown. Through much of the extended recovery Ermler employs the extremely short shots, graphic conflict, and dynamic angles (below) typical of Soviet Montage filmmaking.

Perhaps inevitably, once Filimonov has fully regained his memory and gone to Leningrad, the film becomes more conventional. For a while he wanders about, simply staring and commenting in confusion and disbelief at the modern buildings and people he sees. His hiring at the factory and misunderstanding about who is master there generates some humor as the other workers tease him–in a comradely way, of course. As they explain the new egalitarian society to him, Ermler launches the longest and most varied “work is glorious” montage sequence I have ever seen in a Soviet film of the era, with joyous workers wielding everything from saws to microscopes and, yes, movie cameras.

There is also a brief but amusing scene in which Filimonov takes his old tzarist war medal to donate it to a collection of theatrical props. The bizarre objects in this little warehouse recall the decadent ones Eisenstein uses to characterize the tsar’s quarters in the previous year’s October. This scene, along with much of the motif of Filimonov’s medal, was also eliminated from the “village” version. The intertitles restored in Russian with the original graphic layouts of the original, so that when Filimonov’s repeatedly cries “Who?” when he asks who the master of the factory is, the word changes size and position on the black background from title to title. (There are English subtitles throughout.)

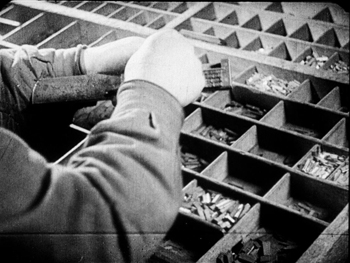

One praiseworthy decision made by the restorers was to leave in the lines of the splices.

These splice-lines are of use to the historian and analyst. Watching a 35mm print on an editing machine, one can examine these directly on the filmstrip. The temptation to “clean up” the images to look pure and attractive, however, too often leads to their elimination. They are part of the original film and should always be left as is.

The Flicker Alley disc is NTSC but without region coding.

L’Argent

Marcel L’Herbier, though not one of my favorite directors, even of the silent period, was a major French director and has appeared on this blog a number of times. I included films by him in my annual list of the ten best films of ninety years ago: El Dorado for 1921 and L’Argent itself for 1928. Flicker Alley has been particularly kind to L’Herbier, and I have discussed their releases of his L’Inhumaine and Feu Mathias Pascal. Having summarized the importance and style of L’Argent in the 1928 post, I’ll concentrate here on the restorations and supplements of the existing discs.

This is the third restoration of L’Argent. The original negative and a finegrain positive made from it survive. In 1971 a restoration was done from this material, but someone made the unwise decision to step-print the new version to simulate the 16 frames-per-second shooting/projection speed of silent cinema. In fact, by the early 1920s the speed of the majority of films was up to around 20 fps, and by the late 1920s, it had reached nearly the same as sound films, around 24 fps. The resulting print of L’Argent, already quite a long film for its day, was off-putting indeed.

A 1994 restoration removed the step-printing and produced a version of excellent visual quality; it provided the basis for the “Masters of Cinema” two-disc DVD set from British company Eureka!, released in 2008. My discussion of L’Argent in the ten best of 1928 included frames from that version, which is no longer in print. It has not been released in a Blu-ray edition.

The third restoration, done by Lobster Films in 2018, forms the basis for the new Flicker Alley Blu-ray disc. (The ongoing cooperation between the two companies has made possible many of Flicker Alley’s discs of splendid copies of hitherto rare or inaccessible silent films.) The original camera negative was scanned in 4K for this new version.

Those who do not own the Eureka! set should welcome the renewed availability of this major film, perhaps L’Herbier’s finest.

Although there is some overlap between the supplements on these two releases, there are also significant differences. Both Eureka! and Flicker Alley include include a 40-minute documentary, Jean Dréville’s Autour de L’Argent (“About L’Argent,” 1928), an elaborate early “making-of” docmentary. Eureka! also offered a 54-minute 2007 documentary, Marcel L’Herbier: Poet of the silent cinema, not in the Flicker Alley release.

Flicker Alley, however, has two items not in the earlier Eureka! set. One is a five-minute short in which Serge Bromberg discusses “The Two Restorations of Auteur de L’Argent“, the Dréville documentary. More importantly, the other is a previously unavailable film, Prometheus Banker (Prométhée banquier). L’Herbier made this 16-minute short in 1921, apparently based very loosely on Zola’s novel, L’Argent. In retrospect, it looks like a brief sketch for the feature-length L’Argent, though it works as a one-reeler. It features L’Herbier’s familiar actors of the early 1920s: Eve Francis as the banker’s lover who longs to return to her happier, humbler beginnings (see below), Jacqe Catelain as the banker’s secretary, and Marcelle Pradot as the jealous typist. Apart from being an interesting early Impressionist film in itself, it provides a useful contrast in styles between similar stories told in 1921 and 1928 by the same director.

Neither the Eureka! release nor the Flicker Alley one has a commentary track. The Eureka! booklet is 78 pages long, with a lengthy essay by Richard Abel and a 1968 interview with L’Herbier, as well as some 1929 reviews of L’Argent. The Flicker Alley booklet is 23 pages, with essays by Mirielle Beaulieu.

According to the box and the film’s webpage, L’Argent is A/B/C, i.e., all regions (though the disc itself is marked A). It is presumably NTSC.

Many blog entries have discussed the Soviet Montage style; see this category. For more on French Impressionist cinema, see Scorsese, ‘pressionist and An old-fashioned, sentimental avant-garde film. We provide background on the two movements in Chapters 4 and 6 of Film History: An Introduction.

September 1, 2020: The Fragment of an Empire release has won The Peter von Bagh Award at the 2020 Il Cinema Ritrovato DVD Publishing Awards.

Prométhée banquier (1921)