Archive for the 'National cinemas: France' Category

Wisconsin Film Festival: Four for the road

Suzanne Simonin, La religieuse de Denis Diderot (1966).

The Wisconsin Film Festival is over, and already we’re looking forward to the next one. In the meantime, here are our last thoughts on some films that impressed us.

Kristin here:

Dürrenmatt in Dakar

Hyenas (1992).

Senegalese director Djibril Diop Mambéty is known mostly for his two feature films, Touki Bouki (“The Hyena’s Journey,” 1973) and Hyenas (1992), and less so for a handful of shorts. Though unable to direct for long stretches of time, Mambéty, who died of cancer in 1998, has been well-served by preservationists. In 2013, Touki Bouki was released by the Criterion Collection in a box set of restorations by Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Project. Now the Cinémathèque Suisse has sponsored a 4K restoration of Hyenas. As the echoes in the two titles suggests, Hyenas was intended to be the second film in a thematic trilogy about the corruption of ordinary people by greed. The third film, Malaika, was planned, but Mambéty’s early death intervened.

Hyenas is based on Swiss playwright Friedrich Dürrenmatt’s dark 1956 comedy, Der Besuch der alten Dame, known in English as The Visit. The film follows the story of the original fairly closely, at least in the play’s first two acts.

The action is set in the village of Colobane (Mambéty’s hometown, where Touki Bouki was also set). The village has fallen on hard economic times, and the genial local shopkeeper, Dramaan, helps keep the place going by extending credit to his regular customers. City officials announce the imminent arrival of Linguère Ramatou, a Colobane woman who left the village and has become extremely wealthy. Dramaan, who had courted Ramatou in their youth, is delegated to greet and butter her up (above). She, however, accuses him of having impregnated her and refused to confess to being her baby’s father. Forced to go abroad, she became a prostitute, was severely maimed in a plane crash, and ended up rich. (How is never explained). Now she promises the villagers great financial aid if they will agree to kill Dramaan.

Although the mayor indignantly refuses, Dramaan soon notices that his fellow citizens are buying luxurious goods that they should not be able to afford. He futilely tries to get local officials to protect him from assassination. All this is played for bitter comedy by an engaging cast of non-professionals. The thematic point is made clear, especially when Mambéty intercuts a pack of hyenas lurking in the nearby brush with a mob of locals who prevent Dramaan from fleeing the town.

It helps to know something about the setting, which would be familiar to Senegalese audiences. The film gives the impression that Colobane is a remote country village. In fact it is a small arrondissement of greater Dakar, a major port on the west coast of Senegal. In a lengthy overview of the director’s life, including an interview with Mambéty shortly before his death, N. Frank Ukadike explains:

The Colobane of Hyènes is a sad reminder of the economic disintegration, corruption, and consumer culture that has enveloped Africa since the 1960s. “We have sold our souls too cheaply,” Mambéty once said. “We are done for if we have traded our souls for money. That is why childhood is my last refuge.” But what remains of Colobane is not the magical childhood Mambéty pines for. In the last shot of Hyènes, a bulldozer erases the village from the face of the earth. A Senegalese viewer, one writer has claimed, “would know what rose in its place: the real-life Colobane, a notorious thieves’ market on the edge of Dakar.”

The last shot is startling, as it reveals for the first time (at least to non-Senegalese viewers) that Colobane is located right up against a city. Possibly in Mambéty’s childhood it was a village later absorbed by the spread of Dakar. It’s not clear from the film when the action is taking place, although Ukadike suggests that it must be in the 1960s or later. The implication of the final shot is that the corruption of the villagers is as much an urban problem as a rural one–if not more so.

The restoration has resulted in vibrantly colorful images that emphasize the indigenous costumes, particularly of Ramatou and her entourage (see bottom). Metrograph is releasing the film theatrically in the US, and with luck a Blu-ray will eventually make it more widely available.

David here:

Anomalies in the space-time continuum

Vultures (2018).

Almost from the start, popular moviemaking has played tricks with linear time and space. Edwin S. Porter’s Life of an American Fireman (1903) contains both a dream and editing that replays key actions from two viewpoints. The more developed silent cinema explored flashbacks, subjective viewpoints, and other strategies. By the 1940s, filmmakers around the world were trying these tricks in sound movies, all seeking to enhance curiosity or suspense or surprise.

Most of the movies that play with space and time resolve the uncertainties clearly. The opening of Mildred Pierce skips over important moments without telling us, but by the end a flashback fills them in. This sort of gamesmanship has remained a permanent resource of mainstream cinema, especially in genres that rely on crime and mystery. Think of Pulp Fiction or Memento or The Usual Suspects, or more recently Identity, Side Effects, or the many heist movies that conceal crucial parts of the plan.

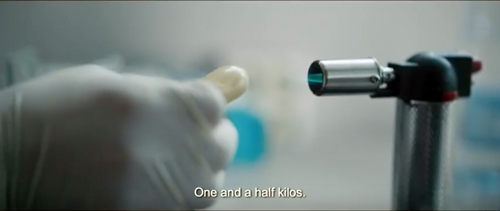

Börkur Sigpórsson’s debut feature Vultures is a good example of a conventional crime film made more intriguing by the way it’s told. The basic story is formulaic. An Icelandic real-estate developer needs to replace money he’s embezzled, and so sets up a drug-smuggling deal. He enlists his ex-con brother Atli to help the mule, a Serbian woman named Zonia, get through airport security. After that, Zonia has to be sequestered until she evacuates the pellets of cocaine she’s swallowed. In the meantime, Lena the policewoman gets on the trail. The whole scheme falls apart when Zonia collapses and Atli starts to take pity on her, while Erik decides to get the pellets by any means necessary.

This straightforward arc of action is presented in fragments that jump among time frames. Before the credits, we see Zonia hesitantly gulping down the pellets, getting sick on the flight into Reykjavík, and hiding in a toilet. She’s frightened when she hears a knock on the door.

Flash back to follow Atli and Erik planning the smuggling scheme. Then, via brief replays, we’re back with Zonia swallowing the pellets, Zonia on the plane (with Atli now revealed as a fellow passenger), and Zonia bolting to the toilet. He’s the one knocking on the door.

This sort of back-and-fill pattern sharpens our interest by delaying the revelation of who’s knocking on the door, while also filling us in on the brothers’ scheme. The interpolation also allots some sympathy to Atli. In the flashback he’s shown visiting his drug-devastated mother and trying to reassure his wife that he’s going to be providing for her and his son. Soon we see him distracting the airport police so that Zonia can pass through freely. The deal seems to have come off. All they have to do is retrieve the pellets.

Abruptly we skip far ahead in time to reveal a bit of the end of the story. I won’t provide a spoiler, but let’s just say that whatever certainty we gain about the outcome is provisional and partial. Still, with this small anchor in Now, the narration doubles back again through a long flashback that traces the unraveling of Erik’s scheme.

As often happens with flashback construction, the time-shifting in Vultures has a double impact. It teases us with hints about what will happen, and it forces us to concentrate on how and why it happens. (Something similar is at work in Duvivier’s Lydia, which I analyze in this month’s “Observations on Film Art” installment on the Criterion Channel.) Told more linearly, Vultures wouldn’t have been so engaging, I think. Nor would it have so sharply focused our concern about the characters’ decisions. And that crucial glimpse of the future allows us to hope that Zonia’s fate isn’t what it would have seemed to be if her story had been presented in 1-2-3 order. As usual, the how of storytelling is as important as the what.

During the 1950s, films not only fractured their action in challenging ways but also refused to resolve all the questions that were raised. We might not fully understand everything that happened. This strategic ambiguity has been central to what’s sometimes called “art cinema,” and is nicely showcased in Pause, another debut feature. If Vultures plays hob with the crime movie, Cypriot director Tonia Mishiali gives us a jagged domestic drama, a diary of a going-mad housewife.

Elpida is falling apart. The darkly comic opening scene, with a doctor ticking off a virtually endless list of her ailments, portrays her as enervated and beaten-down. How she got that way becomes clear. Her husband Costas shovels in food in angry silence. He watches soccer on their main TV, while she has to watch her violent crime videos with headphones. He comes and goes as he pleases; she steals time to attend a painting class or have coffee with a neighbor. When he decides to sell her car without further discussion, and when a young contractor comes to repaint their apartment house, Elpida dares to imagine life without the lout she married.

Imagine is the key word. From her drab routines we pass without warning into fantasies of resistance, escape, and payback. At first, the visual narration makes clear that these acts of rebellion are wholly in her mind. As the film goes along, however, the boundary gets fuzzy. Is the breezy workman making a pass at her, or is she just wishing for it? Is she really drugging Costas’ coffee? And is murder in the offing?

The cinematography won’t tell us. Like Vultures, Pause presents its story through a now-standard blend of planimetric framings and a “free-camera” handheld style that suggests nervous urgency. The fantasies are treated through both techniques.

A woman’s domestic discontents, projected through fantasy, has been a mainstay of cinema since at least Germaine Dulac’s Smiling Madame Beudet (1923). Here, Mishiali’s careful pacing of Elpida’s household chores establishes a solid rhythm that’s broken by the imaginary moments. Like many modern films, the drama builds up by immersing us in the characters’ routines and then disturbing them with sudden outbursts. Yet the climax is remarkably quiet, further teasing us about what may or may not have happened. In any case, by the end, Elpida may be liberated. Yet her final laughter, echoing through the end credits, doesn’t feel especially jubilant.

Get thee from a nunnery

Suzanne Simonin, La religieuse de Denis Diderot was Jacques Rivette’s second feature. In 1962 he submitted a screenplay to censorship authorities but was told that if the film were made it would probably be banned. After another try in 1963, a third version was cautiously accepted, with the warning that it might well be forbidden to viewers under 18.

Shooting began in September of 1965. Catholic groups immediately objected. After a public outcry, in which Godard called on Minister of Culture André Malraux to intervene, there was a screening at the 1966 Cannes Film Festival. The film wasn’t released in France until July of 1967. Usually known as La religieuse (The Nun), it’s gone largely unseen in America. We were lucky to screen the sparkling 4K version that Rialto is now distributing.

The story is set in the years 1757-1760. Suzanne, illegitimate daughter of a prominent household, is parked in a convent, like many women who had no other life chances. Her first Mother Superior, who treats her with affection, dies and is succeeded by a harsh younger woman. Suzanne loves God but resists the rigid discipline. She’s beaten and starved, denied access to her Bible, and believed to be possessed.

She’s rescued by church officials and a kindly lawyer, who oversee her transfer to a very different convent. That’s run by a sexy, permissive Mother Superior who seems anxious to bed our heroine. Suzanne finds the license of her new home as disquieting as the asceticism of the old one. In the end, she escapes with a priest who abandons his vows. Soon she’s on her own in a grimy secular milieu.

No wonder the French church was outraged. True, Diderot’s novel was a classic, and Rivette had already mounted the story as a play. But on film the revelation of ecclesiastical corruption was vivid and shocking, and the presence of New Wave star Anna Karina gave it undeniable prestige. Popularity, too: It attracted more than 2.9 million spectators, making it the ninth most successful release of the year. (Films by Godard, Rohmer, Bresson, Bergman, and Chabrol drew fewer than half a million.) Rivette’s first feature, Paris nous appartient (1961) had drawn only about 29,000. As often happens, creating a scandal proved good for business.

Seen today, La religieuse is hard to imagine as a mass-audience hit. Rivette presents his inflammatory plot with a calm austerity. The dominant colors, at least for the first seventy minutes or so, are shades of beige, brown, white, and black. Shot in very long takes, usually at a distance from the action, the scenes are confined largely to chapels, corridors, and sparsely furnished rooms. La religieuse exemplifies what one wing of Cahiers du cinéma called “classical” direction. As a critic, Rivette admired Hawks, Preminger, Rossellini, the American Lang, and late Dreyer for their sober, unemphatic staging of performances. In place of flashy angles and aggressive cutting, mise-en-scène should center on expressive bodies and faces captured from a respectful distance.

In a 1974 interview, Rivette explained that his most proximate influence was Mizoguchi Kenji–a director who made the restrained, long-take scene central to his style. While most scenes in La religieuse are cut up a little, Rivette seldom moves nearer than medium-shot distance. He uses close-ups with the same parsimony that Mizoguchi displays. Most directors would have cut in to a closer view of Suzanne when, kneeling, she’s asked to pray to Jesus, but Rivette obstinately makes her gesture part of a nearly two-minute shot.

This might seem a stagy approach, especially if you remember Rivette’s interest in varieties of theatre. But like other Cahiers critics, he believed that “classical” filmmaking harbored qualities that also kept cinema “modern,” on the aesthetic and moral edge.

In the abrupt editing of the long takes in Dreyer’s Gertrud (1964), Rivette found a revival of the powers of montage. Dreyer didn’t hesitate to interrupt moving shots. Rivette felt that the film exploited “tantalizing cuts, deliberately disturbing, which mean that the spectator is made to wonder where Gertrud ‘went’; well, she went in the splice.”

In La religieuse, most cuts within scenes are axial, not reverse angles, and they often mismatch action in ways that break the flow of the long takes.

At other moments, Rivette’s editing subjects his distant shots to ellipses that recall Godard’s jump-cuts and Resnais’ experiments in Muriel. We get space-time anomalies more abrasive than those in Vultures and Pause.

Suzanne is in her cell, fretfully pacing. She pauses and, thanks to a cut, seems to look at herself at prayer.

She drifts to her needlework, and suddenly a cut takes her back to the other side of the room.

While she looks in the mirror, the camera backs up and, continuing over a cut, arcs to the right to reveal that she’s already flung herself onto her bed.

Where did Suzanne go? Well, she went in the splices.

It’s wonderful to have this quietly astonishing film available again. The ever-reliable Kino Lorber is bringing out a Blu-ray edition next month, with commentary by Nick Pinkerton, a critical essay by Dennis Lim, and a new documentary about the production. Don’t you want one? I bet you do.

Thanks as usual to the coordinators of our film festival–Jim Healy, Ben Reiser, Mike King, and Zach Zahos–as well as their colleagues and the hordes of cheerful volunteers who kept everything running smoothly.

The information about Colobane from N. Frank Ukadike is from his article on California Newsreel. For a trailer of the restored Hyenas, see here.

The information on La Religieuse‘s censorship struggles comes from Jean-Michel Frodon, L’Âge moderne du cinéma français: De la Nouvelle Vague à nos jours (Flammarion, 1995), 149-151. Rivette’s comments on Mizoguchi’s influence are in this Film Comment interview from 1974. His remarks on Gertrud are part of a 1969 Cahiers du cinéma panel discussion, “Montage,” translated in Rivette: Texts and Interviews, ed. Jonathan Rosenbaum (British Film Institute, 1977), 86-87. The conversation is available online at DVDBeaver. I derived attendance figures from Simon Simsi, Ciné-Passions: 7e art et industrie de 1945 à 2000 (Dixit/CNC, 2000), 46-47.

What’s an axial cut? Glad you asked. Kurosawa uses them (here too), as does Eisenstein and his Soviet peers and French avant-gardists. Silent cinema has plenty, but so do the films of Wes Anderson and John McTiernan. And The Simpsons, often.

Our first full day of the festival opened with a screening of Ozu’s Good Morning (Ohayo), selected by guest Phil Johnston, and the final show a week later presented Jackie Chan’s Police Story. (The first is already available in a Criterion disc, the second is coming soon.) Now that’s what I call a film festival.

Hyenas (1992).

The ten best films of … 1928

La passion de Jeanne d’Arc

Kristin here:

Time for our twelfth annual alternative to the usual list of the ten best films of the current year. Instead, I offer a list from 90 years ago, in part for fun and in part to call attention to some lesser-known classics that are worth discovering. (See here for our lists from 1917, 1918, 1919, 1920, 1921, 1922, 1923, 1924, 1925, 1926, and 1927.)

The year 1928 marked the triumphant conclusion of the silent cinema. Very few sound films were made that year, and those that were often included only music, perhaps sound effects, and occasionally some passages of dialogue. Sound was not innovated because the silent cinema was in aesthetic decline. Quite the contrary. It was initially an enhancement that film-industry people assumed would make films more lucrative. In most cases the “talkies” that followed over the next few years were inferior to their silent predecessors, in part due to the limitations of the new sound technology. Those who opposed the addition of sound could point to the films of 1928 as evidence that the young art form had already reached a peak of perfection that was being tarnished by the addition of recorded sound.

In compiling this year’s list, I came up with eight titles that seemed unquestionably to belong on it. There were another six on a list of possibilities for the final two slots. More than in past years, this year gave me a chance to go back and rewatch films I hadn’t seen in a long time, in some cases since graduate school in the 1970s. Some held up well, some not so much. In a few cases, restorations made since my first viewings revealed new strengths in films I remembered from poor prints.

As always, there are films that have been lost but which plausibly could have filled out the list, most notably Ernest Lubitsch’s The Patriot and F. W. Murnau’s 4 Devils.

First, the eight obvious choices, in no particular order apart from #1.

1. La passion de Jeanne d’Arc.

Not every year includes a film that is not only one of the tops of its year but of all cinematic history as well. Carl Theodor Dreyer’s final silent film is one such masterpiece.

Jeanne d’Arc seamlessly blended the stylistic traits of the great artistic film movements of the 1920s, German Expressionism, French Impressionism, and Soviet Montage and made something new and unique of them.

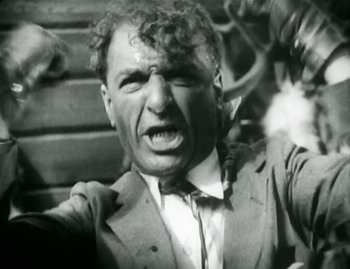

Expressionist designer Hermann Warm’s past credits had included two films that have featured in these lists, Robert Wiene’s Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari and Fritz Lang’s Die müde Tod. Warm collaborated with French theatrical designer Jean Hugo to create spare, white, off-kilter sets that focus our attention on the spiritual drama. Fast editing conveys subjectivity, as in the scenes where Jeanne is threatened with torture and where the citizens are suppressed when they riot after her execution. Rudolph Maté’s cinematography is startlingly dependent on close shots, particularly on the face of Jeanne, played by Renée Falconetti in one of the most intense and affecting performances in any film.

The steady progression of the action condenses days of trial testimony into one apparently continuous story. Between the sets and this inexorable march toward Jeanne’s martyrdom, there is a sense of both spatial and temporal disorientation that focuses our attention intensely on the central conflict.

Until 1981, prints of Jeanne d’Arc were indistinct and incomplete. A pristine print that restored the original visual quality and detail was found in Norway. (The film was among the early ones to be shot on panchromatic film stock without the actors’ using makeup. The result is a detail of texture in the faces that enhances the performances tremendously.) This print is the basis for the Criterion Collection’s edition of the film.

It’s a film that one can see over and over and still be overwhelmed at the originality and intensity of Dreyer’s vision. We saw it projected last November in Houghton, Michigan, with Richard Eichhorn’s recently composed accompaniment, “Voices of Light,” essentially an oratorio and film score rolled into one. We were somewhat trepidatious about whether the score would be distracting, but it proved very effective. Once again, I was reminded of how great this film is. (“Voices of Light” is an optional accompaniment on the Criterion edition linked above.)

2. October

If Jeanne d’Arc gains intensity through a nearly claustrophobic treatment of space, Sergei Eisenstein creates an epic tenth-anniversary celebration of the 1917 Revolution in his October (finished and released a year late).

Perhaps the most extreme example of Soviet Montage’s frequent avoidance of a single protagonist, October cuts among a wide variety of the people involved in the revolution. Workers pull down a statue of the Tsar. Lenin speaks at Finland Station. Kerensky and his officials luxuriate in their Winter Palace headquarters. Sailors wait on the Aurora battleship. Elderly citizens try to protect the specious February Revolution. Female soldiers are summoned to protect the Palace from the attacking Red forces. Looters steal bottles from the Tsar’s wine-cellar. The result is a sort of patchwork collage of the Revolutionary events leading up to the storming of the Winter Palace and the attack itself, with a slow build to an exultant climax as the Red forces triumph.

Eisenstein was given extraordinary access to the locales of the actual events, so that the vast halls of the Winter Palace and the trappings of royalty (Fabergé eggs and fancy crystal liquor bottles) give a sense of reality rare in fictional reenactments. (There was a time when October was plundered for “documentary” footage of events which had not been recorded by cameras at the time.) He used the settings to ridicule the anti-revolutionary forces, as when young cadets are summoned to help fight the Red forces and are dwarfed by the muscular colossi that line one area of the Palace’s exterior (above).

The film also represents Eisenstein’s experiments with “intellectual montage,” where he attempts to convey ideas strictly through juxtaposing series of images. In belittling the phrase “for God and country,” he tries to reduce the notion of “God” to absurdity by linking a long series of increasingly exotic depictions of deities from different religions.

Whether Soviet audiences of the late 1920s could make anything of such passages is impossible to know for sure, but one suspects that some of them would have been incomprehensible. Still, it is exciting to see an artist playing with such possibilities. Certainly the technique lived on, whether from the simple juxtaposition of cackling hens and gossiping women in Lang’s Fury or Jean-Luc Godard’s dense, often impenetrable strings of images, especially in his political films.

October exists in many versions. Beware the heavily cut versions under the title Ten Days That Shook the World. These images were taken from the 2008 release by the Soviet Ruscico company in its “Kino Academia” series.

3. Spione

Despite the widespread enthusiasm for Lang’s Metropolis, his other big films of the 1920s–Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler, Die Nibelungen (Siegfried and Kriemhilds Rache), and Spione–seem to me better. Metropolis is perhaps flashier in its design and conception and certainly very entertaining, but it’s also sprawling and implausible and essentially pretty silly.

Spione, on the other hand, has a tight, fast-paced narrative. It’s sort of Dr. Mabuse boiled down to one feature instead of two, and with the villainous Haghi (again played by Rudolf Klein-Rogge) as a banker secretly masterminding a spy ring rather than a gambling racket. There are no great “heart vs. hand” themes here–just a rattling good tale stylishly presented. Expressionism has disappeared in favor of a streamlined look (above), and Lang’s editing has sped up since Mabuse.

There’s not much point in detailing the plot here, since it would involve too many spoilers. Discover it for yourself if you haven’t already.

Spione circulated for years in the truncated American release version, which is how I first saw it. A 2004 Murnau Stiftung restoration of the complete version was a revelation, not only for its more complete narrative but for its superb visual quality. It’s a feast of shots that only Lang could have composed (above and bottom). These frames are from the Eureka! DVD, but the company has subsequently released it in dual format DVD and Blu-ray. Kino Classics has also released it in Blu-ray. The same company has put out a boxed-set of all Lang’s silent films (including Die Pest im Florenz, directed by Otto Rippert from Lang’s script). We were given this recently and haven’t had time to explore it, but it looks like a must for any fan of Lang.

4. L’Argent

Marcel L’Herbier makes his second and final appearance on this annual list with his epic adaptation of Emile Zola’s L’Argent, updated to contemporary Paris. (See the 1921 entry for El Dorado; I also wrote about the Flicker Alley releases of the restored versions of L’Inhumaine [1923] and Feu Mathias Pascal [1925].)

Inspired by Abel Gance’s even more epic Napoléon (1927), L’Herbier set out to make a film that would require a large budget. To obtain that, he made a deal for his own company, Cinégraphic, to co-produce with the mainstream studio, Cinéromans. The result contains brightly lit sets of big banks and expensive apartments, as well as shots made in the Paris Bourse over a three-day weekend (above). L’Argent also had an all-star cast. It included Brigitte Helm and Alfred Abel fresh off Metropolis, thanks to the German distributor, UFA. It also meant that Cinéromans tampered with the film, re-editing and shortening it.

Given L’Herbier’s reputation as an aesthete and an avant-garde filmmaker, L’Argent was dismissed by many at the time as a purely commercial endeavor. It remained unseen and hence virtually forgotten for decades. A screening at the New York Film Festival in 1968 surprised and impressed the spectators. The real recognition of the film as a major artwork came, however, in 1973, when critic and theorist Noël Burch published his monograph, Marcel L’Herbier (Paris: Seghers, 1973). In it he hailed L’Argent as a masterpiece, devoting the entire final chapter to an analysis of it. Burch also wrote the entry on L’Herbier for Cinema: A Critical Dictionary: The Major Film-makers ([New York: Viking Press, 1980], Vol. Two, pp. 621-28), edited by Richard Roud; again Burch devoted much of his text to L’Argent.

I have expressed my reservations about L’Herbier’s films in earlier entries, but for me L’Argent is the big exception: stylistically daring and narratively engaging. Perhaps adapting Zola led L’Herbier to make a more conventionally suspenseful film than usual. Referring to the French Impressionist movement in general, Burch wrote, “L’Argent undoubtedly marks the end of the period of experimentation, since it is itself the culmination of all these experiments–not just L’Herbier’s, but those of the first avant-garde and even, to a certain extent, of the entire Western cinema (with the exception of the Russians)” (Roud, pp. 624-25).

The story involves two powerful bankers who spar for control of one large bank’s standing on the stock market. One, the villainous Saccard, aims to send a famous aviator on a perilous flight across the Atlantic to promote his bank’s oil holders in Latin America–while seducing the aviator’s wife during his absence. The other, Gundermann, tries to thwart him by buying up shares of his rival’s bank and then selling them to cause a drop in the bank’s value.

In portraying all the complex machinations going on, L’Herbier adopts a restless camera, frequently moving among and around characters rather than following them. The most striking example comes early on, when an underling comes to visit Gundermann and waits in an odd, unfurnished room decorated with a map of the world. As he looks around, the camera circles him until a servant unexpectedly appears through a door and escorts him in.

The odd distortions in these shot exemplify another cinematographic technique that was in increasing use during the late 1920s: conspicuous wide-angle lenses. On the left below, Saccard is nearly dwarfed by one of his telephones, while on the right the scene of the aviator’s departure makes the plane’s wings jut into the foreground and extend far into the background.

There are some subjective moments, carrying forward the tradition of French Impressionism. Yet for the most part the restless camera, the distorting lenses, the odd angles (see the top image of this section), and the unusual crosscutting are not subjective, which makes this an atypical Impressionist film. Instead they suggest the unnatural, disconcerting world of capitalism, of money and those who struggle over it. Perhaps by minimizing character psychology and striving to represent more abstract concepts, L’Herbier briefly carried Impressionism to a more political–and dramatic–level.

In 2008, L’Argent was released on DVD by Eureka! in the UK as a “Special 80th Anniversary 2 x Disc Edition.” The source material was a beautiful fine-grain positive struck from the original negative, with something close to L’Herbier’s original intended cut. It includes Jean Dréville’s Autour de “L’argent,” a 40-minute making-of (surely one of the first of its type), recorded during the original production. The DVD is still in print and is, as far as I know, the only release of this restored version.

5. Steamboat Bill Jr.

This was the first Keaton film I ever saw, and I immediately became a fan. (The director is credited as Charles Reisner, but we all know that Keaton was primarily responsible for the direction of his films of this period.) It’s not as good as The General (what is?), but it beats out The Cameraman, Keaton’s other feature of this year, by a nose.

Keaton plays the dandified son of a gruff steamboat owner. He returns home from school and gets put into working clothes by his father, whose deteriorating steamboat is competing for tourists with a larger, newer boat. Naturally young Bill is in love with the daughter of the other steamboat’s owner. The action mainly consists of Bill, Sr. trying to prevent Bill, Jr. from clandestinely meeting his girlfriend.

There’s lots of humor along the way to the climax, in which a huge storm hits the town. It’s a classic sequence of Keaton pulling variant gags on the situation of being in a high wind (above) and surrounded by collapsing buildings and flying objects. Perhaps Keaton’s most famous, and dangerous, gag comes when he pauses in front of a house’s façade, which tears loose and falls straight down on him–with a window sparing him from being crushed.

Reportedly the top of the frame missed his head by six inches, but we know Keaton was a little crazy in how far he would go for a laugh.

Steamboat Bill, Jr. was the last film Keaton made with his own production company. The Cameraman was made at MGM, and though it is very good, thereafter his career slowly declined after his move to that studio. This will, alas, be the last Keaton film represented in this series.

6. The Circus

Coincidentally, The Circus was the first Chaplin film I ever saw. I happened to take my first film course at the point where Chaplin had re-released The Circus, accompanied by a new musical score he composed himself. (Skip, if you can, the added opening, with Chaplin singing a maudlin song over an excerpt from later in the film.) The re-release was 1969, though I must have seen it in 1970 at Iowa City’s art-house, the Iowa. (Also coincidentally, my father managed the Iowa when he was at the university there on the GI bill in the years immediately after World War II. He was dating my mother at that point, and there she saw Day of Wrath. Hence when David and I became a couple in the mid-1970s, she understood what the book he was currently working on was about. But I digress.)

The print I saw at the Iowa was pristine.

Up to that point, The Circus had been unavailable to most viewers, though I suspect bootleg prints circulated among collectors. It’s among the least known of Chaplin’s features, and it’s still hard to see. There’s a Park Circus DVD available in England, consisting of the re-release version equally in mint condition; that’s the one I’ve taken these illustrations from. More recently the film has been released as a Blu-ray/DVD combination. There is also an Artificial Eye Blu-ray available, which gets high marks from DVD Beaver. I haven’t seen this and don’t know whether it’s the re-release version or the original.

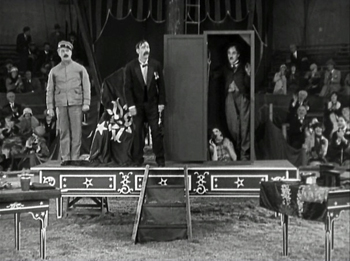

Chaplin plays his Little Tramp character, introduced wandering around the sideshow attractions near a circus. Mistaken for a pickpocket, he flees among the booths, occasioning a brilliantly staged triple scene in a hall of mirrors. When he first enters it, he is alone and struggles to figure out how to exit. A short time later, pursued by the pickpocket, the two stumble into the room, and a comic chase ensues (above). Finally, a cop is chasing Charlie, who tries to confuse him by luring him into the mirror maze. It’s a set of gags that builds, with the figures popping unexpectedly into the foreground when we had assumed that the real actors were in the depth of the shot. Each scene in the maze is handled in a single take from the same camera setup.

The flight from the cop leads the Tramp into a failing circus cursed with a group of highly unfunny clowns. Charlie inadvertently and unwittingly becomes a sensation for his antics, including his invasion of a magician’s act.

The cruel circus owner hires him, supposedly as a prop man, and the show becomes a huge success. Charlie falls for the maltreated daughter of the owner, who in turn becomes smitten by a handsome tightrope walker. Trying to impress the daughter, the Tramp goes on when the tightrope walker fails to show up one day. The result is a classic extended scene of Charlie on the high wire, executing a series of comic moments before the whole thing is topped off by a group of monkeys who escape and end up swarming over him as he struggles to keep his balance.

I hope now that The Circus is becoming more available, it can takes its place beside Chaplin’s other features.

[December 29: Thanks to Valerio Greco for alerting me that a restoration of the original version of The Circus is underway in Bologna, to be released by The Criterion Collection.]

7. The Docks of New York

I’ve already written about this, Josef von Sternberg’s final silent feature, in 2010 on the occasion of The Criterion Collection’s release of it alongside Underworld and The Last Command in an essential box-set. The six films von Sternberg made with Marlene Dietrich after she came to Hollywood generally get more attention than any of his silents. If I were allowed three of his films for a proverbial desert-island situation, I would take Underworld, The Docks of New York, and Shanghai Express.

Docks is a concentrated dose of the atmospheric cinematography the director is famous for, in this case employed to create the grungy settings of the film. In the opening, the oil and sweat on the stokers’ bodies (above) is palpable, and the fog, hanging nets and lanterns, and smoke of the dockside sets establish the sleezy, hopeless milieu that drives the heroine to attempt suicide.

Apart from the impressive visuals, the film gains much of its appeal from its two central performances. Betty Compson manages to gain our considerable sympathy for “the Girl” in a remarkably short time, and she has to–the film is only 75 minutes long and she spends her first onscreen appearances unconscious after her near-drowning. George Bancroft, known mostly for supporting roles in westerns, came into his own as the protagonists of three von Sternberg films–including Thunderbolt but not The Last Command. Here he again plays the big lug with a well-hidden heart of gold.

Unfortunately the von Sternberg silents set from The Criterion Collection is out of print. Track it down somewhere or hope for a Blu-ray release.

[December 29: Peter Becker of The Criterion Collection tells me that, although a Blu-ray release is not yet scheduled, there is a good possibility that it will happen.]

8. Storm over Asia

After Mother and The End of St. Petersburg, Storm over Asia (the original title translates as “The Heir of Genghis Khan”) is the last of Vsevolod Pudovkin’s three great silent features. Unlike the first two, it is set in Mongolia. The Soviet industry officials were concerned to portray the Revolution in the various other countries that along with Russia made up the Soviet Union.

The story takes place during the Civil War years that followed the Revolution. A young Mongolian peasant tries to sell a valuable fox fur at a trading post, but the British dealer cheats him. The peasant strikes him and is forced to flee into the mountains, where he joins the Red partisans fighting the British imperialists. (This does not follow historical fact, since the British occupied parts of Siberia and Tibet, but not Mongolia. In reality, for a brief period in 1921, White Russian forces drove out the Chinese from Mongolia. In response, the Red Army moved in, supporting the Mongols in their quest for independence.)

The British shoot the protagonist but discover on him a document that seems to identify him as the heir of Genghis Khan. So they set him up as a puppet ruler in order to control the local population. Eventually he rebels and leads a storm-like assault that defeats his oppressors.

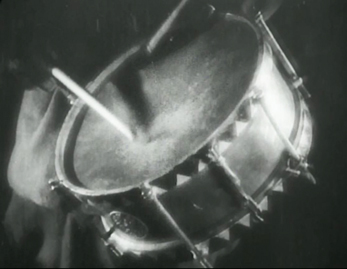

Storm over Asia uses many of the Soviet Montage devices that by 1928 were fairly conventional. For instance, there are many rapid, rhythmic alternations of shots. When the fur trader reacts angrily against the protagonist’s resistance to being cheated, brief shots of his angry call for troops to capture the young man alternate with shots of a drum being beaten. The final “storm” battle uses rapid montage as well. There is also the usual visual symbolism mocking the enemy, as exemplified by the empty officer’s uniform in the shot above.

Early Montage films tried to do away with a single central character in favor of a focus on the masses. October, for example, has no main hero. In Storm over Asia, though, the story arc is definitely crafted around the Mongol’s growth into a rebellious leader of his people. We will see Eisenstein opting for a central identification figure in Old and New (1929).

My illustrations were taken from the old Image release, apparently no longer available. The Blackhawk print has been released by Flicker Alley.

Those are the eight films I put on my “top” list. I thought of stopping there, but the number ten is sacred for such lists, plus part of the point here is to throw a spotlight on lesser-known films.

I gathered a second group of films that might claim the remaining two slots. These were mostly films that were already hallowed classics when I was in graduate school: King Vidor’s The Crowd, Jean Epstein’s La chute de la maison Usher, René Clair’s The Italian Straw Hat, and Victor Seastrom’s The Wind. Beyond that there were the more recently rediscovered and much admired film, Paul Fejos’ Lonesome and the still little-known The House on Trubnoya, by Boris Barnet.

Oddly, the three American films on this list have some distinct similarities. The Crowd and Lonesome are surprisingly parallel. Lonesome follows two lonely people in New York finding each other and falling in love in one hectic day. The Crowd starts with a somewhat similar situation–both even involve dates at Coney Island–but follows the couple through several years of happy times and misfortune during their marriage. The Wind is less realistic, dealing with a sensitive young woman who travels to the west and, plagued by the incessant wind and a real or imagined rape, slips into madness. All three strive to reject the conventional Hollywood romance. Unfortunately all three, however admirable for most of their plots, lead to abrupt, implausible happy endings.

I saw The Italian Straw Hat in my graduate-school days and found it remarkably unfunny, given its reputation. Returning to it now, I still find the first two-thirds largely devoid of humor. (The dance scenes during the wedding party seem interminable, with no little vignettes or gags among the characters at all.) The last portion picks up, but on the whole it’s hardly the model French farce it is held to be. Certainly Clair made a leap forward in skill and sophistication in his early sound films. (Les deux timides, also 1928, is no doubt a better film.)

The Italian Straw Hat probably owes its classic standing in part to the fact that the Museum of Modern Art acquired and circulated it early on. Curator and critic Iris Barry adored it and lauded it in a 1940 essay (reproduced in the booklet included in the Flicker Alley release.) I wonder how many others of the films considered classics have become so because they were among the few silents available in the decades before the 1960s, when film studies and archival curatorship began to be more comprehensive. Knowing the range of international films we know now, would these films have become quite so highly respected above others? I found myself reluctant simply to fill out my list with old standards. The choice was difficult.

Wanting to avoid carrying on the older canon at the expense of more recently rediscovered films for at least one of my films on this list, I always try to include a little-known but worthy film here. This year there is only one (if you don’t count L’Argent), and that is Barnet’s The House on Trubnoya.

The final slot goes to Epstein’s The Fall of the House of Usher. I have always considered this a somewhat tedious film, but the restoration of the film’s full length and improved visual quality in the Epstein box-set released in 2014 by La Cinémathèque Française makes it far more interesting and effective.

So here is the completion of my list.

9. The House on Trubnoya

Boris Barnet was a member of Lev Kuleshov’s school in the early years after the revolution. He played a major role in Kuleshov’s The Extraordinary Adventures of Mr West in the Land of the Bolsheviks, and he began directing films on his own with the wonderful serial, Miss Mend. He made more films, and some others may show up in our coming lists. Right now, there’s The House on Trubnoya.

The House on Trubnoya is included in Flicker Alley’s major DVD set, “Landmarks of Early Soviet Film.” (I can’t believe that we didn’t feature this on our blog, but it includes eight major Soviet films of the silent era.) The copy on the back of the box describes Barnet’s film as “often described as one of the best Soviet silent comedies.” I’m not sure that’s a major distinction, though Kote Miqaberidze’s Georgian satire My Grandmother (1929; available on DVD and Fandor’s Amazon streaming site) is quite funny, as is Ivan Pyriev’s The State Functionary (aka The Civil Servant; not, as far as I know, available on home video). But The House on Trubnoya is my favorite among the comedies I’ve seen.

It’s a satire on middle-class citizens’ maltreatment of their servants, though it doesn’t become Soviet-style preachy until well into the story. The film begins by setting up the titular house (on a well-known street in Moscow). We see it via its staircase and landings in the morning, rendered in a vertical view that looks startlingly like an iPhone image (above). It also recalls the seven levels in the staircase elevator shot climbing upward to 7th Heaven, though who knows whether Barnet had seen that by the time he planned his film. The residents of the various apartments emerge to use the communal stairway as a junkyard and work area, dumping trash, splitting firewood, beating curtains, and generally abusing the rules of the building, as one conscientious young Party member points out.

We are introduced to a barber, whose lazy wife makes him do all the chores. Then suddenly we’re with a professional driver with his own car. Just as suddenly we’re watching a peasant girl chase her runaway duck through a maze of traffic and nearly get hit by a tram. As the driver brakes hastily and jumps out to see if she’s hurt, there’s a freeze-frame.

A narrating title declares, “”But wait, we forgot to tell you how the duck ended up in Moscow.” Reverse motion leads to another title, “A day earlier.” A flashback to the heroine’s comic departure from a train station in the middle of nowhere shows the very uncle whom she is going to Moscow to visit arriving at the station just after she has left. Finding herself lost in Moscow with her duck, the heroine gains employment as a put-upon maid serving the barber and living in the house on Trubnoya. Her political awakening and the rehabilitation of the House on Trubnoya form the rest of the plot.

The House on Trubnoya is, in short, an imaginative, clever, and funny Soviet Montage film. Barnet’s other films are worth exploring as well. Check out The Girl with the Hatbox from 1927; it didn’t make last year’s top items, but it was on the long list.

10. La Chute de la maison Usher

Jean Epstein, who was probably the finest of the French Impressionist directors, has figured in these ten best lists before, in 1923 for Cœur fidèle, in 1924 for the little-known L’affiche, and 1927 for his masterly La Glace à trois faces.

I have long considered La Chute de la maison Usher interesting for its use of German Expressionist-inspired sets, but the fuzzy, incomplete prints that for decades were the only available versions made it difficult to enjoy. The restored version on the complete DVD set of Epstein’s works, which I discussed here, makes it far more interesting.

Taking its slim plot from Poe, the film follows a visit by an elderly man to the isolated castle of his old friend, Roderick Usher. Usher is painting a portrait of his beloved wife, but it is soon made clear that each time he presses the brush to the canvas, a little of her life is drained away–though the local doctor is mystified by her decline.

The film retains some of the traits of Impressionism, as when Madeline’s reaction to the effects of her husband’s painting are rendered in a superimposition of negative and positive images of her face.

The film has a minimal plot, but its focus is largely on experimentation in creating an eerie atmosphere. Shots of books falling in slow motion from their shelves, of curtains blowing in a cold wind that seems perpetually to invade the house, of frogs copulating in a nearby pond, and of the Expressionist-derived decors contribute less to a linear plot than to a mood of undefined menace.

The castle’s exterior is represented by obvious cardboard models, which tends to undermine the effect created by the interiors. The cheapness of these models is particularly noticeable in the climactic scene of the destruction of the house. This is unfortunate, but one must give Epstein credit for having done so much with so little.

This will be Epstein’s final appearance in our “Ten Best” lists, but I would like to call attention to his other 1928 film, Finis Terrae, the first of what the Epstein box-set collects as his “Poémes Bretons.” These are less Impressionistic, though Finis Terrae has a few impressive subjective shots. They are more realistic and poetic, largely involving the sea.

As I wrote at the beginning, 1928 was part of the period when the American industry was on the cusp of making sound standard in its films. Other national cinemas followed at various paces. One film that did not quite make my top-ten list demonstrates what must have worried film theorists and critics–and no doubt some filmmakers.

The restored version of Lonesome includes some dialogue sequences in a film otherwise accompanied by recorded music. There is an enormous contrast between the silent and sound footage. The story is largely told visually, but the dialogue scenes, clearly done in a sound-proof studio, are delivered in a stilted fashion by the young actors who are otherwise so casual and lively. The prospect of whole films being made in that fashion clearly disturbed lovers of films like La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc and Steamboat Bill, Jr. Watching Lonesome gives a dramatic insight into this slice of cinema history–a period that fortunately lasted only a few years as the technology improved and as filmmakers increasingly managed to make sound films that were just as imaginative, artistic, and engrossing as their silent predecessors.

January 6, 2019: Thanks to Docks of New York fan Tony Lucia for a correction on that section.

Spione

Lovelorn LYDIA: A new installment on the Criterion Channel

DB here:

In the fading days of FilmStruck, Kristin and Jeff and I are looking forward to continuing our Observations on Film Art series on the new version of the Criterion Channel in the spring. (If you’re in the areas served, US and Canada, you can sign up here. I did already. Quick and easy.)

In the meantime, our final entry on the FilmStruck platform is going live on Monday, 19 November. There I consider Julien Duvivier’s Lydia (1941) as an example of the power of flashback storytelling.

I talked about the film in Reinventing Hollywood as part of the massive 1940s revival of this technique. Critics’ long-standing emphasis on film noir has led us to think that that trend epitomized flashback construction, but actually the technique is almost completely general. In the book, I consider several “women’s pictures” that employ it: Kitty Foyle (1940), The Affairs of Susan (1945), The Locket (1946; also discussed here), and Lydia. The Criterion series allows me to illustrate more concretely how Duvivier and his colleagues tell the story of a woman captured by passion and moving into old age almost (but not completely) disillusioned.

Working on the book and the entry made me better appreciate a director I’d neglected. Like everybody else, I had had a high regard for La Belle Équipe (1936) and Pépé le Moko (1937), and I had seen and liked his Simenon adaptation Panique (1946). A special favorite of mine is his cross-border comedy about switchboard romances, Allo Berlin? Ici Paris! with clever sound work quite advanced for 1931. Beyond Lydia, other Hollywood efforts of his proved important for Reinventing Hollywood. Tales of Manhattan (1942) and Flesh and Fantasy (1943) are adroit instances of the episode film, that format using what I called “block construction.”

Duvivier was sometimes disdained by the younger generation as an old-guard academic, but I’ve come to see him as a rather interesting experimentalist. He tried out a day-in-the-life network narrative (Sous le ciel de Paris, 1951), a charming what-if comedy about screenwriting (La Fête à Henriette, 1952), and a solid Gabin polar (Voici les temps des assassins, 1954). His suspense drama Marie-Octobre (1959), might seem overly theatrical because it has a Rope-like confinement to a single evening, an anniversary dinner for survivors of the Resistance, but it’s actually based on a novel and gains tension from its almost real-time duration. It showcases a range of major stars (Darrieux, Blier, Reggiani, Ventura) and boasts one of the most dazzling parlor sets I’ve seen in a long while.

Among his thrillers adapted from English authors there’s the curious Chabrolian exercise, La Chambre ardente (1962), based on a John Dickson Carr novel, and the seedy Chair de poule (aka Highway Pickup, 1963, below) from James Hadley Chase.

I’m sure there are clunkers and potboilers among his dozens of titles, but it’s a pretty distinguished career, running back to the silent cinema and his early classic Poil de carotte (1925). His department-store drama, Au Bonheur des Dames (1930), exemplifies bravura silent-film style at its height. He even remade The Golem (1936).

For me, Lydia encapsulates the ambitions typical of Duvivier and 1940s Hollywood. The film could count as a rewrite of Carnet du bal (1937), his story of a woman who revisits the men who danced with her one night in her youth. That plot might seem to demand a string of flashbacks, but instead it’s all played in the present. Her confrontation with what the dashing young men have become leads to a string of extraordinary encounters enacted by top players of the day (Rosay, Bauer, Fernandel, Raimu, Jouvet, Sylvie). The melancholy tone, involving a mournful devotion to impossible love, is reminiscent of Dreyer’s Gertrud.

Lydia takes the alternative option of actually dramatizing the memories of the heroine and her three lovers as they reflect on the old days. The flashbacks are daringly introduced with straight cuts and curt sound bridges; a couple of scenes use slow-motion for the past, a very unusual choice for the period. The soundtrack is unusually lush, with the brilliant Miklós Rózsa supplying lilting waltzes and even some early electronic effects. For a bold montage merging Lydia’s passion with that of the raging sea, he came up with a fierce piano concerto.

The film plays on the disparities of time and memory in a rather modern way. Flashbacks contradict one another, and what we see doesn’t always match what the voice-over tells us. Lydia in the present seems to whisper advice to the girl we see in the past, as if she’s watching the film along with us. The climax is quietly devastating: the twist was demanded by censorship, but producer Alexander Korda claimed, rightly, that it improved the film. We’re left wondering how much to trust Lydia’s memory of her idealized affair.

One thing that didn’t make it into our entry: Discussion of the peculiar cottage where Lydia and her lover Richard share their passionate idyll. It seems to be built out of the bodies of big naked people. So I share one image with you, below.

Apart from that, I hope you get to play my installment, in the waning days of FilmStruck, or maybe cached on the new Criterion Channel in the spring. You can sign up for that streaming service here, and the sooner you do it, the easier it will be to launch.

We’re grateful as usual to Peter Becker, Kim Hendrickson, Grant Delin, and the whole Criterion team, and to Erik Gunneson of the UW Department of Communication Arts. Special thanks to Daniel Reis, editor of most of our installments, whose adroit cutting strengthened them enormously. (The Lydia entry masterfully stitches together disparate sequences using Lydia’s dialogue as a voice-over.) Other entries were cut by the equally gifted Clyde Folley. Thanks as well to Kelley Conway and Phillip Lopate for conversations about Duvivier.

Criterion has served Duvivier well, offering several of his works on DVD.

A list of our Observations installments to date is here.

Lydia (1941): A house embellished with ships’ figureheads becomes the lovers’ sanctuary.

On the Criterion Channel: Five reasons why HIROSHIMA MON AMOUR still matters

Often this scandalous or honorable story, this beautiful or ugly one, will be told you the next day or the next month, sometimes in fragments. There is nothing that is of a piece in this world, everything is a mosaic.

Balzac, Une fille d’Ève

DB here:

We’re not big fans of listicles. Our only effort in this direction is our annual review of the 10 best movies of 90 years ago. But now we have my Criterion Channel installment devoted to Hiroshima mon amour. (There’s a sample here.) The installment is focused on the film’s use of editing. That topic does allow me to touch on wider matters of storytelling and theme, but I found myself struggling to squeeze in all I wanted to say. So. . . .

If you haven’t seen the film, both this and the Criterion Channel segment will teem with spoilers. Now I’ll give a plot synopsis, but the shocks in the film’s early stretches are probably softened if you know the story’s premises. So if you haven’t seen the film yet, you’re advised to stop reading now.

Hiroshima mon amour, the 1959 feature film directed by documentarist Alain Resnais, tells the story of a brief sexual affair between an unnamed man and woman. She has come to Hiroshima to make a film about the effects of the US nuclear bombing of the city in 1945. Her plane is scheduled to leave the following day, but he asks her to stay longer in Japan. As a result, what drama there is becomes psychological—pressured by her deadline, but complicated by her memories.

After their first night of lovemaking, she tries to break with him, but in the course of the day he pursues her and they meet at intervals. They go to his house for another bout of lovemaking, to a bar called the Tea Room, to the train station, and back to her hotel, where the film began. In the course of their affair, she recalls and recounts her wartime romance with a German soldier stationed in her city of Nevers. At the liberation, he was shot by a sniper. The townsfolk punished her by cropping her hair and confining her in a cellar.

In a gesture characteristic of ambitious cinema of the period, we don’t definitely learn that the woman decides to leave. The final scene, suggesting that she will always think of the man as Hiroshima, does imply that they’re parting. More important, in the course of their affair she has realized that her memories of her first love are fading, and she fears that makes her deeply disloyal to him. Worse, she feels that she’s already forgetting her Japanese lover. The passage of time and the waning of emotion come to feel like a betrayal.

Hiroshima is one of the most important films ever made, summing up many tendencies of modern cinema but also indicating new directions for later filmmakers. Its implications and possibilities radiate out in several directions, like the spidery silhouette (in negative?) under the opening credits. So a listicle format seems, for once, justified.

(1) The opening

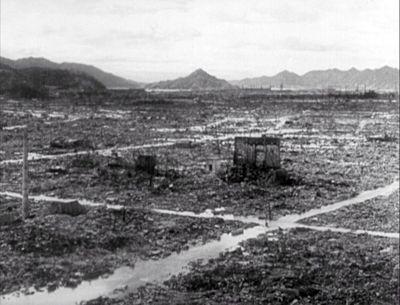

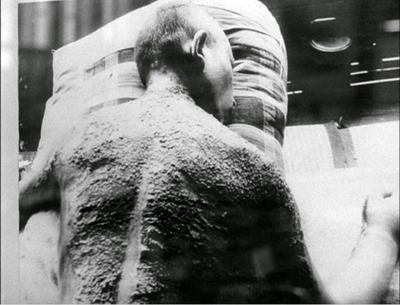

Two bodies, from the waist up, are locked in an embrace. The faces aren’t visible. At first, the bodies are powdered with dust but as the images dissolve into one another, the limbs are glittering and then oily with sweat.

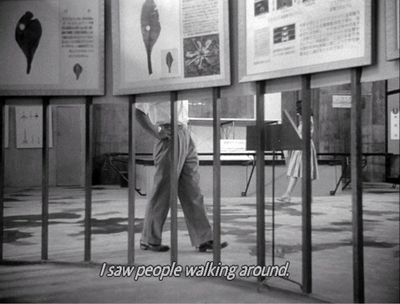

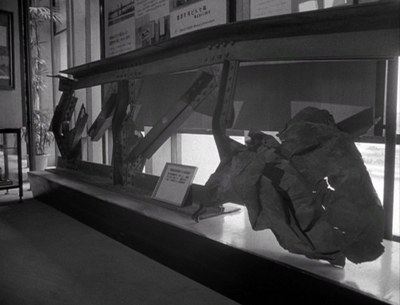

These images give way to documentary-style shots of Hiroshima, both in the present and in newsreel footage. We see modern architecture, a hospital, museum exhibits, city streets, a cheerful lady bus conductor, victims of the nuclear blast, and even restaged scenes of the bombing’s aftermath, taken from fiction films.

Over all the footage float a male voice and a female voice: “You saw nothing in Hiroshima–nothing.” “I saw it all…” She describes what can be seen and understood, while he contradicts her. We return intermittently to their bodies. The sequence concludes with her voice: “I met you here.”

Thus ends one of the most daring sequences in film history, a dense thirteen minutes of imagery, music, and dialogue. I think it’s hard for us today to grasp just how jolting this opening felt in 1959. Ten years after its premiere, when I first saw it (and without much foreknowledge), I was overwhelmed. For me, and I think for many others, cinema wasn’t quite the same after this.

For one thing, there’s the sex. Although it’s portrayed abstractly, the voluptuous skin tones and clutching, twisting arms are powerfully erotic–and poetic. The oily skin might be considered realistic, but the dust particles can’t be justified as anything but metaphorical, perhaps nuclear fallout or the ashes of a city in flames. (Is this like the embracing couples discovered in Pompeii by the heroine of Voyage to Italy?) Later the sexual angle will become more socially specified; it’s an “interracial” coupling, involving a French woman with a Japanese man. An entire “social problem” movie could be made about this situation, which this film takes utterly for granted.

Then there’s the juxtaposition of this stylized intercourse with the bombing of Hiroshima–and naked bodies very different from the ones we see in bed. We’re given smooth tracking shots through a hospital and a museum. In some of his documentaries Resnais had presented locales in solemn, slightly disquieting traveling shots, mimicking a tourist-eye view into a library (Toute la mémoire du monde, 1956) or a concentration camp (Nuit et brouillard/ Night and Fog, 1956). Here, similar traveling shots are more or less anchored to the unseen woman reporting on her impressions.

I say more or less because, in a slippage characteristic of the film, sometimes the camera height is lower than an adult’s eye level, as in the second shot above. And often the camera is withdrawing along the line of the museum exhibits, as if looking backward.

Already the imagery is rendered a little detached from a human perspective. More generally, by suppressing the woman’s face and eliminating diegetic sound, the shots for all their concreteness seem unreal, as if pulled up from memory or imagination.

When the shots segue to found footage (“I saw the newsreels”) and then to strident reenactments, those too seem less historical records or blatant fictionalizing than part of a phantasmagoric vision.

Maps and twisted relics, faces and stones, kitsch and authentic suffering are all put on the same plane, with a disturbing neutrality.

Perhaps this is the tragedy of Hiroshima as absorbed by a consciousness unequal to it. But what consciousness could comprehend it? Night and Fog openly proposed that our minds couldn’t grasp the enormity of the Holocaust. Not that this was a counsel of despair; our very helplessness was a warning to remain vigilant against the next glimpse we might get of human monstrousness. Here another voice challenges the limits of our sympathetic imagination: “You saw nothing.”

What about the opening’s soundtrack? Plaintive piano music, Debussy-ish, passes to strings and woodwinds–slow and brooding, but sometimes disarmingly bouncy. Nothing could be farther from the Mahleresque scores of Hollywood cinema or most documentaries than this chamber-music intimacy. The score pulls a bit away from the images, we might say, seldom emphasizing them even at their most horrific.

In his documentaries, Resnais had pioneered a lyrical, somewhat dry voice-over quite different from the conventional nudging or hectoring Voice-of-God commentary. Like the tracking shots, though, this vocal technique takes on a new effect in a fictional cinema. For one thing, when and where is the conversation occurring? Not evidently during the lovemaking. Before? After? Maybe never? Is it a sort of telepathic exchange, expressing the essence of her tourist-level days in the city and then his assured sense that such an experience blinded her to the real Hiroshima? Interestingly, we’ll learn that he wasn’t in Hiroshima during the attack. So perhaps he, like the narrator of Night and Fog, is warning her against premature confidence in understanding any historical event on this scale.

The woman’s voice dominates the soundtrack, meditating on her lover and her surroundings. Again, it might be a monologue addressed to the man at some point, but thanks to rushing shots through Hiroshima streets, it equates his body with his city. This motif will culminate at the climax, when she compresses her memories of 1944 down to landscapes in Nevers and she decides to give her lover a name: Hiroshima.

Since the mid-1940s, André Bazin had argued that the future lay with long take-filming that respected the continuum of reality–the continuum that Soviet filmmakers had freely splintered in order to make rhetorical and poetic points. Yet with this overture, Hiroshima revived and revamped the Soviet tradition of montage-based moviemaking. The sequence averages a little more than six seconds per shot, a rate seldom seen in European fictional film of the 1950s. The result somewhat recalls the free editing of Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera, but it anchors the visual disjunctions in psychology and a personal drama yet to be specified.

Bazin had worried that by chopping the world into little fragments, editing by its nature ruled out ambiguity of expression. Yet here was a film that showed, as avant-garde filmmakers had done, that montage could generate poetic ambiguity. Editing patterns could create analogies and associations. The spatter on a rock could evoke the scars on a victim’s head, and the dusted couple of the opening could become ghostly doubles of a victim of radiation.

One could even intercut staged footage and documentary material without hiding the filmmaker’s artifice (as Citizen Kane does with the faked footage in “News on the March”). Free montage and collage-like mixing of documentary and fiction would be hallmarks of 1960s and 1970s films by Alexander Kluge, Dušan Makavejev, and of course Jean-Luc Godard.

Something similar happened with the soundtrack. Detached, unemphatic scores would become part of the repertoire of modern cinema, as would floating voice-overs. Films like Chungking Express and Wings of Desire, to say nothing of the work of (again) Godard, would show the expressive power of voices cut free from story time and space. Montage, as Eisenstein prophesied juxtaposed not only image to image but image to sound.

No later passage of Hiroshima mon amour is as aggressively disorienting as this overture. It’s as if Psycho started with the shower sequence. This opening not only introduces a lot of cinematic and thematic material. It also seeks to sensitize us to images and sounds, as a poem at the start of a novel might sensitize us to language. My discussion of editing in the Criterion installment points out that most of the ensuing film is cut in a pretty orthodox way, respecting the rules of continuity construction. But the sheer disjunctiveness of this prologue prepares us to notice whatever abruptness and juxtapositions do arrive. Assailed by this opening, at once jagged and eerily smooth, we’re set to register some even finer-grained shifts in time and sequence to come.

(2) Flashbacks that aren’t flashbacks

Hiroshima’s script by Marguerite Duras was, Resnais claimed, based on “parallel editing” that would link wartime France and contemporary Japan. But Resnais insisted that this editing didn’t create flashbacks.

Here is another movie, one that Resnais and Duras didn’t make. A French woman visiting Hiroshima on a film shoot turns tourist. She then meets a Japanese man and they have sex. Next day she avoids him, but he pursues her and eventually she agrees to spend the evening with him. In a bar we get the big reveal: the woman explains her wartime love affair and the punishment that drove her out of Nevers. Her past episodes are given in large blocks, perhaps one long flashback. The plot concludes with the man and the woman forced to choose their future.

We’ve already seen that the woman’s tourist-eye view has been fragmented, scrambled, and stylized in the opening montage. We might be tempted to call those images flashbacks, were they not so firmly part of an overall collage including purely documentary material. But once the story proper begins, we, or at least I, am inclined to call the bursts of images from 1944 Nevers flashbacks–brief ones, but flashbacks.

I say this because I take the primary purpose of a flashback is to present story material out of chronological order. A secondary purpose, not always in force, is to represent a character’s memories. Some films, especially after Pulp Fiction, rearrange story order without appeal to character memory. In classical studio cinema, though, flashbacks are usually motivated by a character recalling or recounting an event that she remembers. More often than not the scenes we see in the past aren’t restricted to what she witnesses or even knows about. Memory provides a rationale for the main purpose–revealing action in the past.

But there’s a contrary line of thought that says that a character’s memory ought not to count as a flashback because memories exist in the present. Arthur Miller took this line with respect to the time-shifts in his play Death of a Salesman, as I discuss in Reinventing Hollywood. Resnais, it turns out, felt the same way. For him, the fragments of the past that interrupt the present-time scenes of Hiroshima exist in the present because they’re being remembered. He wrote to Duras during shooting: “The past won’t be expressed by true flashbacks, but will be felt to be present throughout.” In 1968 he reiterated: “In Hiroshima there is not a second’s worth of flashbacks.”

There’s no point in quibbling about terms, but we should note that Resnais thought his interruptive images of the past were capturing something important about how memory works. Memory is fragmentary and jumbled, not operating in the big chronological blocks given us in 1940s Hollywood flashbacks. When asked by his producer if Citizen Kane hadn’t already shifted chronology, Resnais replied: “Yes, but with me, it’s all disordered.”

Moreover, memory is abrupt and fragmentary: Resnais uses cuts, not dissolves, to deliver his memory images. The first instance in the film has become a locus classicus. The woman sees her Japanese lover’s hand twitch, and that leads to another hand, a quick pan to a dead man being kissed, and then the Japanese lover again. This time-shift is literally a flash, lasting only a few frames.

And to insist that memory operates in the present moment, Resnais uses present-time diegetic noise–a train whistle in the scene above, a pop tune on a jukebox later–providing something that literature can’t: the absolutely simultaneous presence of now and then.

Again, Resnais brings into sound cinema narrative strategies that had emerged in silent film. Gance in La Roue, Fredrikh Ermler in Fragments of an Empire, and others had provided rapid-fire memory montages. In most commercial sound cinema, this sort of mental imagery was largely confined to one-off sequences depicting dreams, hallucinations, or mental illness. Resnais and Duras boldly made an entire film in which recollected moments unexpectedly erupt into present-tense action.

Again, though, the filmmakers introduce ambiguity. It’s hard to plausibly assign some of the “memories” of Nevers to the female protagonist. Bare landscapes and abrupt tracking shots of empty streets seem more like Eliot’s “objective correlative,” more oblique representations of feelings, than traces of what the woman has witnessed. Even the invasive images from the past aren’t free of the uncertainties that hover over the opening sequence. This strategy of hovering between subjectivity and “authorial commentary” would become central to 1960s art cinema–perhaps most obviously in Red Desert, where the unrealistic color can be taken as both an expression of the protagonist’s alienation or a more detached, stylized presentation of a modern wasteland.

(3) Talkies and walkies

Griping about Antonioni’s longueurs, Dwight Macdonald remarked that “the talkies have become the walkies.” His complaint captures something important. From Bicycle Thieves through La Strada and L’Avventura up to Linklater’s Before/After trilogy, the idea of building a plot around two characters’ more or less mundane traipsing became a salient option for filmmakers who wanted to stray from classical narrative organization.

But settling down in one place to talk became important too. Serious European cinema often featured dialogue scenes of a length that would have been discouraged in American cinema. Play adaptations like Sjöberg’s Miss Julie (1951) naturally featured such protracted conversations, but so did works by Bergman such as Waiting Women (1952), Wild Strawberries (1957), and Brink of Life (1958). Having revived silent-film montage in Hiroshima‘s early stretches, Resnais and Duras makes peace with their contemporaries in the second part by settling their characters down for two good chats broken by a long stroll.

It all starts when the man declares, after a second bout of lovemaking, that they have sixteen hours to kill before her departure. By Hollywood standards, this period should be handled with dramatic crises leading to the deadline. Instead, we get a quick montage of the city at dusk (with figures unnaturally still, as if rehearsing for walk-on parts in Last Year at Marienbad) and the two of them at a table in the Tea Room bar.

It’s in this lengthy scene that the woman’s memories become most coherent for us and the man. What was private in earlier parts of the film–flashes like the hand on the bed–become externalized in her confession. Again, though, we get Resnais’s version of “disorder.” For one thing, her Nevers story isn’t given in a block, but rather as a burst of fragments. After their second lovemaking, she had already begun to tell her lover about her affair with the German, and the editing was rather choppy: six alternations of past and present in about seven minutes. Now at the Tea Room she’s more explicit about his fate and her punishment. Over twenty-four minutes, the action alternates between Hiroshima and Nevers seventeen times. Often a single shot breaks into her confession.

For another thing, the incidents remembered tumble out of order. Glimpses of her imprisoned in a basement are followed by her ritual haircutting before being sent there. Image and sound fall out of true: we see her pedaling to Paris, we hear her telling us what she read in the newspapers upon arriving. We need to integrate what she’s recounting now with what she’s recalled earlier.

By the time the couple leave the Tea Room, we have a fairly coherent account of the woman’s Nevers trauma. In our alternative film, we’d now have a climax in which she decides to leave Hiroshima or stay. Instead, she and the man separate. She returns to her hotel, washes her face, accuses herself of betraying her German lover with the Japanese, and. . . wanders back outside.

She returns to the Tea Room, now closed. The plot’s irresolution is prolonged. Her lover materializes, as if summoned by her voice-over. The woman, now distraught, tells him she’ll stay. Immediately she tells him to leave. He says he could never leave her. Then he leaves her.

What follows is a string of further evasions and encounters, almost a suite of variations on how a couple can seek to connect and avoid connecting. The film becomes a walkie. Resnais planned the street scenes, he explained in a letter to Duras, by listening to a tape of her reading the commentary and blocking the actors’ movements with wooden dolls.

The woman moves down the street, trailed by her lover. He follows her to a train station, and then to a bar called–you must remember this–Casablanca. She eludes him by letting a slick stranger join her for a drink. The night goes on. Dawn arrives.

In the course of these stop-and-start ramblings, memories return, but images of her lover dwindle, to be replaced by those of Nevers; he has faded into the landscape. As I indicated, these might as well be narrational commentary rather than her memories, with the film’s overarching form juxtaposing the French city with the Japanese one in ways she doesn’t yet grasp.

Now you know why people say art movies seem never to end: They tease us with closure and then deny it. Extended talk scenes and walk scenes, however realistic they may seem in contrast with busy Hollywood plots, are also conventions of this mode of filmmaking. It’s up to the filmmakers to shape them to their immediate purposes.

(4) At the limit

In a plot centered on action–goals, blockages, clashes among characters, struggles to accomplish some feat–you typically have a clear-cut climax and resolution. The protagonist either succeeds or fails. But when you deny that sort of arc, you have to find other ways to inject drama. In Hiroshima, we have a classic instance of the undecided protagonist, who can’t settle on a goal and so drifts from situation to situation, each one of which dramatizes a facet of her character, or of her indecision.

Sooner or later, the plot has to stop, so if there’s no decisive way to end the action, how do you conclude? The most favored option, borrowed from serious literature, involves what literary theorist Horst Ruthrof calls a “boundary situation.” Instead of creating a resolution by what the protagonist accomplishes, the plot confronts the character with something that forces a reevaluation of his or her life. The drama is psychological, not physical; the resolution involves insight, not action of the normal sort. As Ruthrof puts it, the character “in a flash of insight become[s] aware of meaningful as against meaningless existence.” The boundary situation is existential, consisting of “a final vision or revelation, rejection of false moral premises, and the gain of a state of authenticity.”

James Joyce called such bursts of recognition “epiphanies,” and he employed them in his Dubliners short stories. Ruthrof argues persuasively that they can be found throughout modern European literature, from Flaubert and Tolstoy to Conrad and Thomas Mann. In Narration in the Fiction Film, I proposed that many films in the European tradition had recourse to boundary-situation plots. Guido’s acceptance of all the contradictions of his life in 8 ½ and Isak Borg’s reconciliation with his past in Wild Strawberries are fairly clear examples.