Archive for the 'National cinemas: Germany' Category

The ten best films of … 1932

Shanghai Express.

Kristin here–

The year draws to a close, and the internet abounds with lists by professional critics, educated fans, and clueless people proffering opinions on the ten best films of 2022. David and I avoid this custom, but fifteen years ago I stumbled into a habit of listing the ten best films of ninety years ago. Such films have by now stood the test of time, and they have one enormous advantage: no one is speculating about many Oscar nominations each will get.

Back in the day, only two of the films on my list got nominated at all, and those two collected a total of three Oscars. (For a hint at one winner, see the image at the top. He will feature prominently in this year’s list.)

These ten films are of course my own choices, and for those who disagree, they are quite welcome to make their own lists.

As usual, my list is a mix of very familiar titles and some not so familiar ones. My hope is to call attention to unfamiliar films that are well worth a look. Actually this year nine of the films should be familiar to any serious film student or fan, but the tenth is a masterpiece that deserves to be rescued from obscurity.

Most historians seem to agree that 1932 was the year when Hollywood emerged from the difficult transition to sound and made polished movies that regained the fluidity of cinematography, staging, and editing that had been lost to some extent. In The Classical Hollywood Cinema, Janet Staiger, David, and I proposed that the transitional period lasted from 1928 to 1931.

The same was not internationally true, however. My list contains one silent film, since the Japanese industry went through a considerably longer transition. No wonder that half of this year’s list atypically consists of Hollywood movies.

Previous entries can be found here: 1917, 1918, 1919, 1920, 1921, 1922, 1923, 1924, 1925, 1926, 1927, 1928, 1929, 1930, and 1931.

As usual, I’ll try to point readers toward the best available Blu-rays or DVDs. Those who prefer streaming should be able to find these titles for themselves. David and I prefer discs, at least for important films. With the decline of access t0 35mm and 16mm prints, studying films closely has become more dependent on discs (which also still have better quality images than streaming). Eventually, with streaming the only option obtaining frame grabs of the sort that illustrate these entries, close film analysis will become extremely difficult.

Hooray for Hollywood!

Trouble in Paradise

Ernst Lubitsch is one of the best-loved of film directors, both within the film industry and among cinephiles. I was lucky enough to be invited to teach a one-month summer course at the University of Stockholm on any topic related to silent cinema. I jumped at the chance to follow up on a vaguely planned project on Lubitsch, specifically a comparison of his German and American silent films. The course became a book, Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood, now out of print but available through open access.

Trouble in Paradise is widely considered his best film, though I would say that at least Lady Windermere’s Fan and The Shop around the Corner are equal to it and others are not far behind.

The witty script is a model of sophisticated humor, and the casting is perfect. Herbert Marshall for a change got to play the suave hero, a dazzlingly expert crook who teams up romantically with Miriam Hopkins, his match as a wily pickpocket. In this 82-minute film, their hilarious courtship in a Venice hotel runs for a remarkable 17 minutes as they top each other in stealing things from each other, with her returning his watch and his flaunting her garter:

It doesn’t seem a minute too long. Essence of Lubitsch.

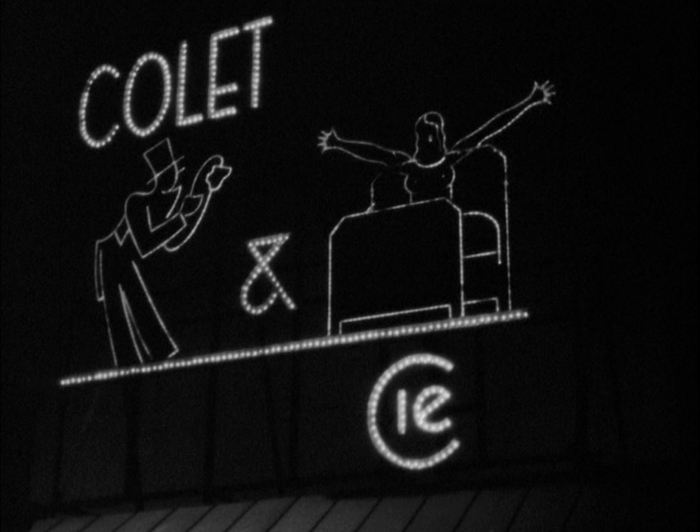

Kay Francis provides the potential trouble that threatens their idyllic life of thievery; she’s a beyond-wealthy owner of perfumery Colet & Cie. (see bottom)–so wealthy that she doesn’t really mind that her “secretary” may be a famous criminal worming his way into her confidence. Charles Ruggles and especially Edward Everett Horton provide hilarity as hopeless suitors wooing Madame Colet.

The comedy is played out in shining art-deco sets (above), lit with perfect three-point Hollywood lighting. As I demonstrate in my book, Lubitsch moved effortlessly from being the master of German silent film style to being the master of Hollywood style. It shows in every aspect of Trouble in Paradise.

The Criterion Collection DVD is still available.

Shanghai Express

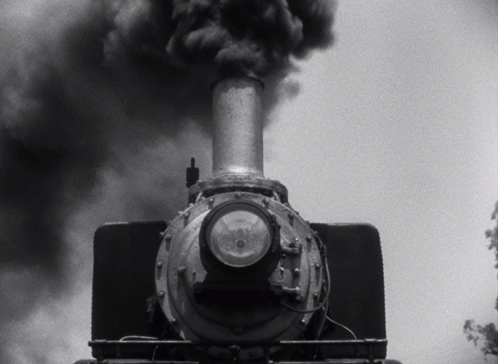

The Josef von Sternberg/Marlene Dietrich teaming. The Blue Angel, featured on my list in 1930. The pair famously made a series of Hollywood films together, all built around the glamor of Dietrich. For me, the best of the bunch is Shanghai Express. It has a stronger script than the others, being set on a train traveling from Beijing to Shanghai during the Chinese Civil War (which had started in 1927). The device of a group on a journey lends the film both unity and suspense. It’s basically a thriller with a romance included. There are more characters than in some of the other Dietrich films, the typical bunch of eccentrics for such journey-plots lending interest, humor, and pathos along the way. Dietrich’s character is strong and likeable. She pursues the man she loves, but on her own terms while he stands around cluelessly keeping his upper lip stiff.

Then there are the incredible visuals. The set design is even more dense than usual for a von Sternberg film. The train windows, both exterior (top) and interior (above) are used brilliantly, and the rebel headquarters where the group is trapped for much of the second half has hanging gauze and stairways that create a complete contrast with the train scenes.

And the Oscar mentioned above went to … Lee Garmes, whose five films in 1932 also included Scarface (see below). Apart from his photography of the settings, he shows off with with other dazzling moments, including an extraordinary tracking shot following an official along the crowded platform for nearly the entire length of the train.

Needless to say, the glamor shots of Dietrich are among the most beautiful ever (Garmes also shot Morocco and Dishonored).

In general, the train station scenes are spectacular and give a remarkable sense of authenticity. Speaking of which, all the extras and minor characters seem to be played by Chinese, or at least Asian people. Anna May Wong has a prominent role as Hui Fei. Whether casting Warner Oland as the rebel leader Henry Chang would count today as “whitewashing” is up for debate. He was born in Sweden but claimed some Mongolian ancestry (so far unproven).

The Criterion Collection has the set of six Dietrich/von Sternberg films on Blu-ray and DVD. (My frames were pulled from an old TCM DVD pairing the film with Dishonored. TCM now offers Shanghai Express by itself on DVD or Blu-ray.)

A Farewell to Arms

The second Oscar-winner of the three mentioned above was Charles Lang, for his cinematography of A Farewell to Arms. (The film also won the third Oscar, for sound recording.)

Frank Borzage has been a staple of these ten-best lists, with Lazybones (1925), 7th Heaven (1927), and Lucky Star (1929). This may be his final appearance in these year-end lists, with growing competition internationally.

A Farewell to Arms adapts Hemingway’s novel of World War I. Gary Cooper plays Frederic, an ambulance medic who spends his spare time drinking and visiting brothels with his friend, Italian Dr. Rinaldi (Adophe Menjou). He meets Catherine, a nurse, at a party, and they fall immediately in love, succumbing to passion under the assumption that war’s uncertainties may not give them another chance. Becoming pregnant, Catherine departs for Switzerland to have the baby, but her letters to Frederic and his to her, are returned to sender. Frederic risks a firing squad by deserting and desperately trying to find her.

Like Trouble in Paradise and other 1932 films, A Farewell to Arms benefited from the fact that the self-censorship Hollywood studios instituted under the Production Code (aka the “Hays code”) in 1933 was not yet in force. The result is a grittier and more honest look at life in wartime than would be possible in later years. Apart from the quite restrained brothel scene (above), there is considerable emphasis on the forbidden unwed motherhood rife among the nurses Catherine works with.

The two stars make a convincing romantic couple of the kind Borzage had become famous for, and the cinematography is lovely. Lang, too, was an expert at creating glamorous images.

Amazon would very much like you to watch the film for free with ads or with a subscription to Paramount+ or with a free Fandor trial or by paying $2.99. Once you scroll past those enticements, you can find Kino Classics release of a Blu-ray or DVD in a remastered version by George Eastman House. It seems a bit overly dark to me, but maybe the original nitrate copy was, too.

Scarface

I have to admit that gangster films are not my favorites. Still, there are outstanding films in the genre, as the presence of von Sternberg’s Underworld on my 1927 list indicates. The early 1930s established the genre solidly, and Scarface stands out among the other classics examples of the time. I have not seen the two other such classics still commonly watched, Public Enemy or Little Caesar, for a very long time, but I recall not being very impressed.

Scarface marks Howard Hawks’s first appearance on one of my lists. It’s not up to his greatest films of the 1930s, Twentieth Century and Only Angels Have Wings (and some would say Bringing Up Baby).

One thing that makes Scarface stand out for me is its considerable use of humor, which seems unusual for a gangster film. Paul Muni, so dignified in his prestigious bio-pics of this same period, lets go and struts with aggressive arrogance, lets go in fits of rage, and makes Tony Camonte a figure of fun with his accent (“That’s putty nice”) and flaunted ignorance. When the woman he’s trying to impress and seduce remarks sarcastically that his clothes are gaudy, he delightedly takes it as a compliment.

The comic relief flirts with slapstick in the figure of Camonte’s “secretary,” who is illiterate, inept, and downright stupid. According to the AFI Catalog, his character name is Angelo, though Camonte addresses him as Dope. There’s a running gag of him being unable to get basic information from callers. At one point during a raging gunfight in a restaurant, he struggles to hear a caller’s name, unaware that a tank behind him has been pierced and is dousing him.

The film also has its visual pleasures. It was one of five films, along with Shanghai Express, that Lee Garmes lensed in 1932. The cinematography is appropriately less glamorous than in Shanghai Express, but it’s dark and occasionally beautiful, as in the hospital-invasion scene at the top of this section.

Many films of the early 1930s start off with an impressive moving-camera shot, presumably to show off before settling down into scenes with standard continuity cutting. Scarface has quite an impressive opening, with a plan sequence leading up to the first act of violence.

It begins with a low angle of a streetlight going out, and then tilts down and tracks rightward past a milk delivery cart and a sign that establishes the locale.

Continuing rightward, it reaches a tired janitor who removes a sign informing us that a stag party had been held there the night before. The camera tracks rights as he starts to clean up.

The camera follows through the wall and continues as he tackles the job in a room festooned with streamers–possibly an homage to the big party scene in Underworld. One artifact of the party that he finds is a brassiere that has lost its owner.

As he pauses, the camera leaves him to pan right and track in on a gang boss and two of his men talking about a potential danger from a rival gangster. He declares that he doesn’t want war and is satisfied with the money he’s making.

The men stand, and the boss promises an even bigger party in a week. Thus for a gangster, he seems a decent sort, not willing to stir up violence against those seeking to invade his territory.

The men leave, and the camera follows the boss across the room and into a phone booth. He starts to make a call.

The camera glides past him and away off to the right, where it picks up a menacing shadow in the next room.

It follows the silhouette as the unknown man walks toward the corridor where the phone booth is. Silhouetted against a translucent window, he pulls a gun, fires it, polishes it with a handkerchief, and throws it on the floor. (This sort of offscreen or partially offscreen treatment allows the violence to be less explicit, a ploy that continues throughout the film.)

As the killer disappears, the camera tracks back to the left, revealing the boss’s body. The janitor enters, sees it, takes off his work clothes, and tosses them in the phone booth.

The scene ends with a pan left to follow the janitor as he hurriedly moves through the mess and leaves.

My frames were pulled from the Universal Cinema Classics DVD, a release which has since come out on Blu-ray. (Amazon still has the same edition on VHS!)

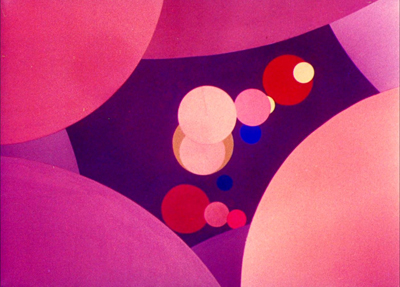

Love Me Tonight

So many of the early 1930s musicals were stagey. The review musicals were series of numbers without a connective narrative (convenient because they could be popular abroad without dubbing or subtitling) or backstage musicals where a “put on a show” premise also led to numbers on a stage. But with the growing freedom of the camera and editing, the musical could become something more.

Love Me Tonight feels like a wildly enthusiastic celebration of that new freedom. The story is a modern Ruritanian romance. A Parisian tailor, played by Maurice Chevalier, travels to a country chateau to collect money owed him by a client, who is a member of the aristocracy. While on his way, Maurice bumps into the debtor’s sister, Princess Jeanette, and falls in love with her without realizing who she is. Once at the chateau, he is mistaken for a Baron and proceeds to charm the Princess’ entire family and gain her love–until his lowly birth is discovered. Throughout, the dialogue is witty and the music and songs, by Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart.

Much of the high spirits of the film arise from the fact that the songs are not sung by one or two people in a single locale. Instead, the music starts out in this limited way but passes along to other characters, spreading infectiously through a household or across a countryside. The process begins on a morning in Paris, as the city wakes up and goes to work. Gradually the rhythmic sounds of various activities build up to a symphony made of sound effects: a woman’s broom against a pavement or two cobblers’ hammers striking in counterpoint.

The first actual music when a man getting married that day picks up his formal outfit and Maurice sings about his work in “Isn’t It Romantic?” The groom goes out singing it, and it passes to a taxi-driver and then his fare–who happens to be a composer. Cut to a train, where he hums the music and writes it down (top of section), overheard by a group of soldiers; cut to a field where they march along singing it, and so on, until we reach the chateau and are introduced to the Princess, also bursting into “Isn’t It Romantic?”

Upon meeting Jeanette, Maurice woos her by singing “Mimi” to her. Here it’s a straightforward solo, though one that is filmed in an unusual fashion with Maurice singing and Jeanette reacting in shot/reverse shot directly into the camera.

Once at the chateau, Maurice apparently sings the infectious “Mimi” for the family and guests since there is a montage moving among them as they all cheerfully warble the song in their respective rooms. The same thing happens still later, when Maurice’s low birth is discovered; the song “The Son of a Gun Is Nothing but a Tailor,” similarly spreads throughout the building, including to the servants, who show a snobbery equal to that of their masters. Who can resist lyrics like those sung by a washerwoman?

Down upon my hand and knees/Washing out his BVDs/Is a job that hardly please me./If I had known I would have tore/The buttons off his panties for/The son of a gun is nothing but a tailor!

Overall one gets a sense that music and singing are irrepressible and ripple outward from the soloists to infect everyone within hearing distance.

Of course once Maurice has been thrown out, Jeanette decides to defy her family and races after his train on horseback. Mamoulian throws in some Soviet-style compositions as she heroically stands on the tracks and forces the train to stop.

Apart from its infectious style and music, Love Me Tonight has a wonderful cast, with Charles Butterworth as Jeanette’s wimpy but titled suitor, Charles Ruggles as the debtor son, Myna Loy as the man-hungry younger sister, and C. Aubrey Smith as the curmudgeonly father who becomes downright jolly under Maurice’s influence. Sheer entertainment.

Love Me Tonight is available from Kino Lorber on DVD or Blu-ray.

Hooray for the Rest of the World!

Vampyr

Two masters of cinema made vampire films a decade apart. I dealt with Murnau’s Nosferatu in the 1922 entry.

The two films could hardly be more different from each other. Murnau’s film was a plagiarized version of Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel, Dracula. He followed the original very loosely, cutting out most of the characters, including Van Helsing and hence the entire lengthy investigation process. Dreyer may well have known Murnau’s film, but it is hard to detect any influence or inspiration apart from the use of a book as exposition. The Universal version starring Bela Legosi was still in production when Dreyer finished shooting Vampyr. Instead, Dreyer drew even more loosely from the collection of horror-fantasy series short stories by Sheridan Le Fanu, published as In a Glass Darkly (1872).

Dreyer seems to have taken a few ideas from the stories, but does not use the narratives associated with those ideas. The notion of a female vampire is probably derived from one of the stories, “Carmilla,” though Le Fanu’s vampire is young and beautiful, while Dreyer’s is an elderly woman, Marguerite Chopin. The collection of stories is presented as having been case studies collected by a Dr. Hesselius, a researcher of the arcane. Allan Gray may be inspired by Hesselius, though he does no evident research and reacts in fear in most cases where he encounters anything strange and grotesque. Gray’s dream of being trapped in a coffin and carried off to be buried comes from “The Room in the Dragon Volant.”

On the whole, though, one of the most striking things about Vampyr is how little it adheres to the conventions of the vampire tale. It is not told as a collection of documents, as are Le Fanu’s stories (“Carmilla”is told in first person by Laura, the heroine and victim of the vampire) and Dracula (a collection of documentation by gathered by several characters). As in Nosferatu, a book is included to help present the “rules” of vampire stories, but the book is not written by Gray. It is given to him by the old Chatelain. The premises that vampires must travel in coffins full of dirt or will be killed if exposed to sunlight, so important in Nosferatu, are ignored here. Actually, the intention seems to be that Chopin is active mainly at night, but since the entire film was shot in murky daylight, it’s difficult to to tell night from day. Vampires also tend to be of noble birth, and we usually find out something about their family history. Chopin seems to be a local woman who somehow became a vampire.

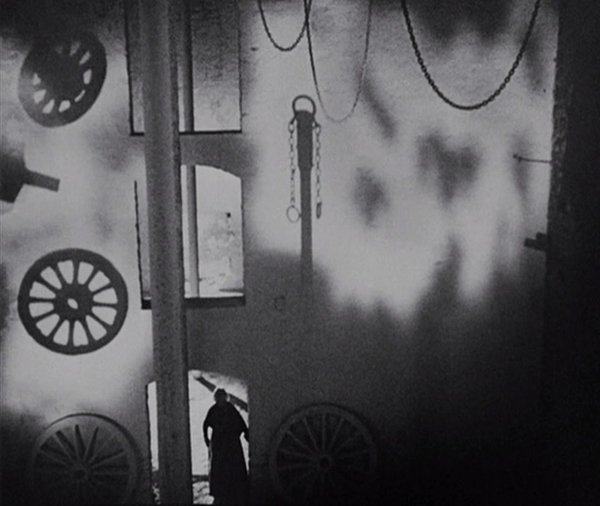

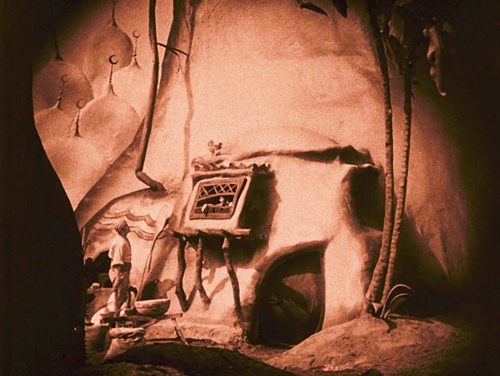

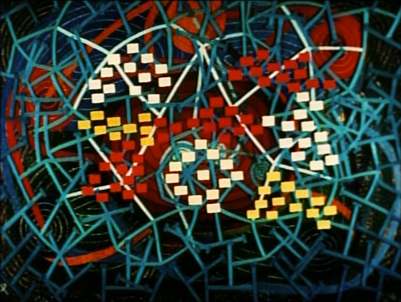

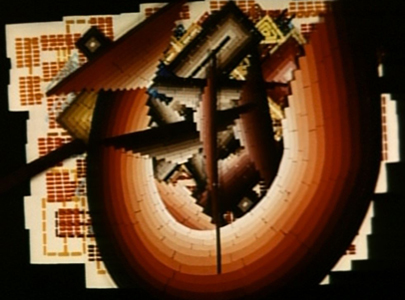

To create a creepy atmosphere, Dreyer has Gray wander about observing menacing, unnatural, or unexplained phenomena in the neighborhood of the village of Courtempierre. These are not phenomena conventional to vampire stories, so they seem as mysterious to us as to Gray. Much of what Gray observes is never explains. Gray sees numerous shadows and reflections of beings who are not visible. He follows the shadow of a peg-leg man until it finally rejoins the soldier who should be casting it. Most vampires live in crumbling Gothic castles, but Chopin seems to have made her headquarters in a dilapidated factory of some sort. (Dreyer chose a deserted plaster factory whose white walls would show off the shadows cast on them.) Her main minions, a sinister doctor and the one-legged military man apparently do whatever they do there, waiting to do her bidding. As the images above and on the right below show, Dreyer creates a mysterious air to the building through the circles and curves of large gears, wheels, and hanging chains.

Beyond such motifs, there are the actors’ unpredictable exits and entrances into the frame during camera movement and the eerie offscreen sounds that hint at something disturbing happening nearby. David has analyzed all this in detail in his book, The Films of Carl-Theodor Dreyer (out of print but available from second-hand book dealers).

For the ending, Dreyer draws upon the convention of a stake through the heart as the way to kill a vampire. It isn’t Gray that figures this out. A remarkably passive protagonist, he sits dreaming of being buried alive while the old servant, initially a minor character, reads the Chatelain’s book, gathers the needed equipment, and initiates the task of the staking of the vampire in her grave.

The 1998 restored version of the film is available from The Criterion Collection on DVD or Blu-ray, with a particularly good set of supplements. These include a visual essay by Danish expert Caspar Tybjerg that deals in more detail with the influences of previous vampire literature and films on Dreyer’s work; I have drawn upon it for some of the information above. Vampyr also streams on The Criterion Channel, accompanied by some of these supplements as well as a video essay by David, “Vampyr: The Genre Film as Experimental Film.”

Boudu Saved from Drowning

Jean Renoir entered this list in 1931 with La Chienne. Although a grim melodrama for the most part, the film provides put-upon accountant Maurice Legrand with a happy ending as he leaves home and becomes a jovial tramp.

Boudu, the self-centered, careless tramp at the center of this film, is presumably not Legrand, despite being played by the same actor, Michael Simon, and Boudu Saved from Drowning is not a sequel. It almost could be, but this time the genre is comedy.

The opening sets Boudu up as an unusual tramp. He is not begging, and when a little girl offers him a small bill, he asks what it is for. “To buy bread,” she replies. Soon Boudu does beg by opening a car door for a rich man, and when the man can’t find any money in his pockets to tip him, Boudu hands him the small bill “To buy bread” and walks away.

Unexpectedly, Boudu jumps into the river in a suicide attempt. Lestingois, a prosperous bookseller whose shop and apartment are across the street, witnesses this and rushes out to dive in and save Boudu. He succeeds, receiving praise from the onlookers as a bourgeois who would take this trouble for a mere tramp. Lestingois is fascinated and amused by this “perfect tramp” and takes him in, offering him dry clothes, food, and a sofa to sleep on for the night, much to the disgust of his wife.

Boudu’s antics delight Lestingois, who treats him somewhat like a pet dog (top of section). He also gives Boudu a lottery ticket, which predictably will become a vital plot device later on. The tramp, however, disrupts the routine of the household–in particular sleeping in a spot that prevents Lestingois from making his nightly visits to the maid Anne-Marie.

Boudu lingers on, seeing this cushy home as a good setup; he tries to fit in by shaving his bushy beard and trying to dress respectably. He is utterly uncouth, however, shining his shoes on the wife’s bedspread, and knocking things off shelves, and causing a flood by leaving water running in the kitchen. Lestingois ultimately gets fed up with him–but in the nick of time Boudu wins the lottery and the attitude of the household changes. Anne-Marie, who supposedly loves Lestingois, suddenly becomes engaged to him.

On the wedding day, however, as the happy couple are in a rowboat on the river, Boudu upsets the boat and floats away to resume his old life as a tramp.

Stylistically the film is distinctly Renoirian. He shot his exteriors in Paris streets and parks, seemingly concealing the camera in some cases. A telephoto lens captures Boudu wandering along the bookstalls on the banks of the Seine, with the other people presumably ignoring him as a real tramp.

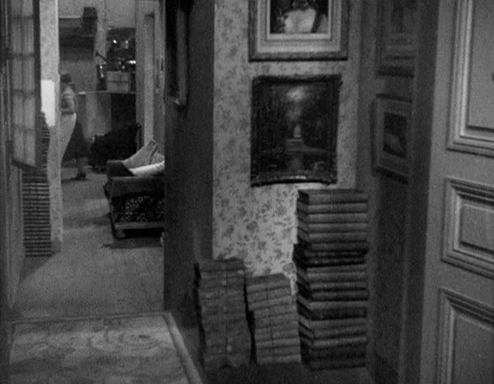

In a modest way, Renoir used the sort of roving camera movement that he would later develop into a major feature his late-1930s masterpieces. One scene starts with Lestingois and his wife eating a meal along with Boudu, seen from a distance down a hallway. As Anne Marie finishes serving, she exits left, and the camera moves left into the next room, where she is glimpsed walking toward the kitchen. It continues moving and stops briefly as Anna Marie enters the kitchen and puts down her tray. As she comes forward to the kitchen window, the camera tracks closer to the foreground window and stops, still at a distance as she talks with an unseen neighbor.

Boudu Saved from Drowning is available on DVD from The Criterion Collection and streams on The Criterion Channel (along with some supplements).

Wooden Crosses

Raymond Bernard’s Wooden Crosses is this year’s masterpiece unknown to most modern viewers, and I cannot recommend it highly enough. I discovered the film through The Criterion Channel. David and I were relatively early in our “Observations on Film Art” series of supplements–early enough that the service was still called Filmstruck. In picking a film for a video essay, I thought it would be helpful to choose titles that were obscure but very much worth calling attention to.

One such film on the Criteron list was Wooden Crosses. I was dubious about it, since my only association with Bernard’s work was the 1924 historical epic, The Miracle of the Wolves, which I had seen back in my post-graduate days and found pretty turgid. Nevertheless, I gave Wooden Crosses a try and was bowled over by it. My video essay, “The Darkness of War in Wooden Crosses,” became number 16 and is available to subscribers.

In some ways Wooden Crosses is France’s great anti-war film of the early 1930s, following Hollywood’s All Quiet on the Western Front and Germany’s Westfront 1918, both of which were in my top ten for 1930. For me, it’s the best of the three.

The film begins with stock footage of Parisian crowds cheering the young men signing up to fight and marching off to war. Like The Big Parade, it introduces the war from well behind the lines, as new recruits arrive at a farmyard where the more experienced troops are billeted. The action takes place shortly after the Battle of the Marne in autumn of 1914; it was won by the French, but did not succeed in achieving ultimate victory. In Wooden Crosses, the experienced men scoff at the recruits for having arrived too late to experience any fighting.

Their optimistic assessment proves wrong, and the group is ordered to march to the front-line trenches. The result is an impressive sequence shot at night as the group goes through open areas, woods, and finally ends neck-deep in the trenches looking out across no man’s land in the darkness. As my video-essay title suggests, there is a considerable amount of night footage in the film. One point I make in that essay is that the epic footage in the film made an impression in Hollywood:

In 1935, the head of the newly merged 20th Century-Fox studio, Darryl Zanuck, bought the North American rights for Bernard’s film. He didn’t intend to release it theatrically. Instead, he realized that the spectacular battle footage was beyond anything that the studio could afford, and he wanted to reuse it.

The film it was to be used in was Howard Hawks’s The Road to Glory, released in 1936. Hawks, however, wasn’t just keen to use the battle footage. Like me, he seems to have admired the many night scenes. He said of Wooden Crosses that it had “Some fabulous film in it, marvelous scenes of great masses of people moving up to the front and through trenches—wonderful night stuff.”

The group of soldiers are quickly and marvelously characterized, notably by Charles Vanel as the group’s quiet, sensible Corporal and Gabriel Gabrio (Javert in Bernard’s Les Misérables) as the sarcastic, boastful Sulphart–a key source of comic relief in the film. Graduallynew volunteer Gilbert Demachy emerges as our main point-of-view character, though the others are kept prominent. There is a suspenseful series of scenes as they hear the sounds of German sappers tunneling below their dugout to lay mines. They are ordered to stay put, as there is plenty of time before the explosions, but as we discover, this is an example of a common motif in these films: the incompetence of the leadership.

One of the film’s most impressive aspects is the epic recreation of battle scenes. There’s no stock footage here, and there are shots over vast areas of no man’s land with explosions going off among the actors.

The climactic battle goes on and on–ten days, as repeated superimposed titles inform us–and conveys the relentlessness of the struggle that the group undergoes.

The battle ends in a long, tense scene, ironically set in a cemetery where many of the graves have been blasted open. These substitute for trenches as the men hunker down under German attack.

As with some of the other films on this year’s list, the cinematography of Wooden Crosses is extraordinary. It was shot by Jules Kruger, who had worked with major French Impressionist directors, notably Marcel L’Herbier on L’Argent and Abel Gance’s Napoléon, the latter of which no doubt gave him considerable experience with epic battle scenes. His most famous films after Wooden Crosses were La belle équipe and Pépé le Moko.

The Criterion Collection did a great service by releasing Wooden Crosses paired with Bernard’s Les Misérables in their Eclipse series. It also streams permanently on The Criterion Channel along with my video essay linked above. (New Year’s resolution: watch more Bernard films. I should give The Miracle of the Wolves another chance and set aside plenty of time to watch Les Misérables, a three-feature serial adaptation of the novel that clocks in at 281 minutes.)

I Was Born, But …

Yasujiro Ozu makes his third appearance in a row on these lists (see here and here for the first two). If I were to live to 102 and if I were still posting these lists, his last film would be on the 2052 list. That’s unlikely, but even so, he will probably be the director most represented on these lists as long as this series continues. I am still pondering whether to give him three spots on the 2023 list or just group his three masterpieces from that year as tied for a single spot.

I Was Born, But … was the first of Ozu’s silent films to become available in the West, and it is still probably the best known. So many of his early films are lost, but this may be the one where he achieved the perfect balance of humor and poignancy that characterizes so many of his best films.

Ozu is known for creating stories centered around the stages of life, often expressed as seasons in their titles, such as Late Spring‘s focusing on a daughter pushing the limits of marriageable age to care for her elderly father. His surviving early films often dealt with students or recent graduates struggling as “salarymen” in the job market of the Depression. In this film for the first time he shows the woes of the salaryman largely from the viewpoint of his children. Many of Ozu’s films are based on relations between parents and children young or grown. Those that dealt with young children were among his masterpieces: Passing Fancy, The Only Son, There Was a Father, Record of a Tenement Gentleman, and Ohayu.

The salaryman films deal with the difficulties of getting jobs, competing with colleagues, and surviving on meager wages. I Was Born, But … adds the problem of the subservience and even humiliation a salaryman sometimes undergoes and how it affects his family.

The story unfolds in parts that to some extent echo each other. Early in the film the two sons are bullied at school by the son of their father’s boss. They manage to defeat the bully and in a show of bravado boast that their father is the best in the world.

Later the family is invited to a gathering at the home of Yoshii’s boss, who shows some home movies of his employees showing off for the camera. These include Yoshii making faces and playing the fool, obviously at his boss’s insistence. The sons’ delight in seeing their father on the screen fades as they realize that their father has been humiliated and is not the great man they boasted about. Implicitly, Yoshii is being bullied as well but must submit in order to please his boss.

In an angry confrontation with their father, the sons accuse him of having proved himself not to be the man they had looked up to. The confrontation ends in their refusal to eat or speak to their parents. The parents admit to each other that their life is disappointing and not one they would wish for their children. The quarrel soon ends, with the boys accepting that their father is not the greatest.

As with That Night’s Wife (1930), Ozu is already using some of the techniques that would be part of his style for his entire career. For example, there is a transition between scenes that uses graphic values and objects in a series of images that do not behave like ordinary establishing shots.

I Was Born, But … is available in another DVD set in The Criterion Collection’s Eclipse series, “Silent Ozu: Three Family Comedies.” The other two are the charming Tokyo Chorus and the wonderful Passing Fancy (which will definitely appear on next year’s top ten). Along with a slew of other Ozu films, it also streams on The Channel. Many of you know David’s book, Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema; it’s long out of print but available through open access on the Center for Japanese Studies Publications site (with the frames from the color films in color!).

Kuhle Wampe or Who Owns the World?

Slatan Dudow’s Kuhle Wampe, scripted by Bertolt Brecht, was a bold pro-Communist film made in the year before the Nazis swept into power.

Kuhle Wampe, named for the workers’ camp in which much of it is set, starts with the dire situation for the working class in Depression Germany. A typical family is singled out, with the son returning home after one of many fruitless searches for work (below). His parents blame him for his failure to find work in a society where unemployment is rampant. Their anger drives him to suicide. A neighbor woman remarks resignedly to the camera, “One fewer unemployed.”

The boy’s sister Anni becomes one of the main characters. Another is Fritz, her boyfriend, a leader in the labor protests in a local factory. When Anni becomes pregnant, the pair split up but eventually reunite when her family is evicted and moves into the tent city of the title, run by a Communist group (above). Communism is portrayed as a solution to the problems presented earlier. A lengthy sequence at a Communist youth sports festival emphasizes the happy life on offer by the Party. In the final scene, directed by Brecht himself, Anni and Fritz have an argument about the world’s financial dilemma with some middle-class passengers.

In 1933, Brecht fled the country, eventually ending up in Hollywood, and Dudow was expelled from Germany, only returning after the war to help found the Communist-run East German film industry.

As far as I can tell, the only DVDs or Blu-ray discs available in the US are imports and may not play on encoded machines. (It’s not even on YouTube!) For those with region-free players, the BFI’s release in either format seems to be best source.

Trouble in Paradise.

The ten best films of … 1931

M (1931)

Kristin here:

Our regular readers know that this annual series began as a simple salute to 1917, the year in which the basic norms of the classical Hollywood cinema definitively gelled. Starting in 2008, it became the “The 10 best films of …” list. It has stood in for the year-end ten-best lists which critics and reviewers feel obligated to concoct but which we avoid.

1931, I think, was a slight improvement on the rather lackluster 1930. A small handful of filmmakers mastered the “talkies” and made movies that look and sound as if they could have been made years later. These are the first four films below. It was a little harder to fill in the list beyond them. It’s is full of familiar classics, with a film or two that will probably unknown to many. I always try to include at least one worthy out-of-the-way title.

Previous entries can be found here: 1917, 1918, 1919, 1920, 1921, 1922, 1923, 1924, 1925, 1926, 1927, 1928, 1929, and 1930

M

I remember seeing M as a grad student, or maybe even an undergraduate, and being horribly disappointed. This was a masterpiece? Actually it was only a semblance of one. In the 1970s a poor, incomplete 16mm print with as sparse a set of subtitles as I think I’ve ever seen was in circulation. The wit and brilliance of Fritz Lang’s sound links and voiceovers were largely lost, as were the sharp images now evident in the restored version. Even restored, as the introductory titles tell us, it is missing 212 meters. Fortunately that’s only .4% of the total, and the narrative progression is so smooth and absorbing that it’s hard to imagine that anything could be missing.

The story concerns a child-murderer terrorizing a city and the parallel searches for him by the police and by the organized underworld, the activities of which are being hindered by constant police searches and raids. At one point Lang famously intercuts a meeting of city officials with one of a group of gangsters. Parallels are created by matched gestures between space but also by one line being started by a character at one meeting and picked up by one at the other. Lang races through exposition by having the voiceover of a phone conversation between officials continuing over shots of the investigation in various spaces.

He uses sonic motifs as well. The killer compulsively whistled a Grieg tune as he lures his victims, but whistles come back time and again. Police whistles signal the raid on a basement tavern, and the beggars who tail their suspect signal each other with whistles–heard by the killer, who flees into an empty office building and ends up trapped there (top).

There’s a lot of offscreen sound in this film. The raid on the tavern cuts around to various parts of the space, as when we briefly follow a crook who tries to sneak out (above) while the protests of the crowd and the whistles and shouts of the police are heard off. One might think that all this is to avoid having to lip-sync the sound with the characters speaking–but when he does show the speaker, the sync is perfect. It’s another instance, I think, of Lang using sound to cram a lot of action or information into a short stretch of time. The thwarted crook is just a bit of comic relief, something Lang injects at intervals into this grim narrative.

Back in 2012, when I participated in Sight & Sound‘s poll of critics and academics for the ten best films of all time, I put M on the list. Counting 2021, it is the third film from that list that I have included in this one: The General in 2016, The Passion of Joan of Arc in 2018, and now M. The next one won’t show up for eight years (hint: Renoir made it in 1939), assuming I’m still doing this list at that point.

If you’ve never seen M, make sure you don’t watch an older print! The restored version is on Blu-ray from The Criterion Collection in the US and Eureka! in the UK.

Le Million

René Clair made two film classics in 1931, À nous la liberté and Le Million. I find the latter a better film in that it’s more complex and lively. À nous la liberté, which focuses on only two characters who spend a stretch of the film apart, has a rather thin narrative. Le Million, on the other hand, involves a large cast of amusing characters and constantly bubbles with dances, chases, and farcical situations. Indeed, early on it cites the chase scenes of early cinema when police pursue the kindly thief, Père Tulip, over the rooftops.

The sets were created by the great French film designer, Lazare Meerson (who also did the more austere sets of À nous la liberté). The interiors often have soft, hazy backgrounds (top of this section) apparently done partly by painting and partly with real objects behind scrims. These give a stylized quality appropriate to a classic farce situation: the debt-ridden artist protagonist Michel frantically searches for a jacket holding a winning lottery ticket as the jacket goes from hand to hand. At one point crossing hallways permit two chases–the police after Tulip, the creditors after Michel–to pass through each other.

David and I taught Le Million in an introductory film class back in the 1970s. I hadn’t seen it since, but it lived up to my fond memories of it. As cheerful a film as one could find for what promises to be another year short on cheerfulness.

Le Million is available on DVD from The Criterion Collection. The description says that the lyrics are all translated here for the first time.

Arrowsmith

Early as it is, Arrowsmith is surely one of Fords’s great films of the 1930s. It’s an adaptation of Sinclair Lewis’ 1925 novel of the same name. (Lewis won a Pulitzer for it but refused to accept the award.) The plot centers around Martin Arrowsmith (Ronald Colman), who starts as a medical student eager to establish a reputation and help discover cures for various plagues. He marries a charmingly impertinent nurse Leora (Helen Hayes), who supports him in his efforts.

The style of the film is distinctly flashy in its lighting, depth shots, and set design. It looks like what we tend to think of as Wellesian–though many of these techniques could instead by dubbed Fordian.

There are dramatic chiaroscuro effects as when Arrowsmith arrives home one evening, discouraged, and Leora sympathizes with him. The figures are side-lit with illumination coming from the kitchen, and Arrowsmith becomes a silhouette once he sits down.

The depth shots are equally impressive. A spectacular high angle (top of this section) shows three levels of a ship’s interior, with Sondelius, a medical expert, shouting up to the captain that he has discovered bubonic plague onboard. A less flashy but highly intense shot shows Leora’s death from bubonic plague. The long take is filmed with what David terms “aperture framing,” with Leora placed far off-center and relatively far from the camera, framed in the arms of the foreground rocking chair. It’s the same chair in which she sat when she smoked a cigarette contaminated with one of her husband’s plague samples. It’s a brilliant way to emphasize that she dies alone, with the bright open door at the center of converging lines of the set stressing that her husband does not suddenly appear, as we might expect, to comfort her.

Other more casual uses of depth with prominent foregrounds include a shot of Arrowsmith exiting his laboratory with beakers, bottles, and other equipment dwarfing him (below right).

Note also the prominent ceiling on the sets in the image on the left above. The notion that Citizen Kane was the first Hollywood film to use ceilings on sets has long been discredited, and here’s a good example of why. In general, Richard Day’s art direction combines with the cinematography to create powerful images, as in the hallway of the McGurk Institute, where Arrowsmith gains a research post.

We know that Welles was influenced by Ford’s work, but he primarily stresses Stagecoach as a film he watched repeatedly before making Citizen Kane. Arrowsmith, however, actually looks more like Kane than Stagecoach does. Did Welles and/or Gregg Toland see it? Very likely at least one of them did. There seems to be no record of Welles having said he saw it, but in 1938 he wrote and performed the title role in a radio version of Arrowsmith that had Hayes repeating her role as Leora.

Moreover, Arrowsmith was produced by Samuel Goldwyn. In the late 1920s and early 1930s, Toland was making films there, including Eddie Cantor comedies (Whoopee!, 1930) and two crime dramas starring Colman (Bulldog Drummond, 1929, and Raffles, 1930). It seems implausible that he would not have seen Arrowsmith.

All this is not to say that Arrowsmith was the first film to play with depth and chiaroscuro. As David pointed out in a 2010 blog entry, such ideas were developing in Hollywood during the 1920s, and William Cameron Menzies in particular experimented with them. There David wrote, “The flashy depth compositions of the 1920s and 1930s were typically one-off effects, used to heighten a particular moment.” True enough, but I think Arrowsmith uses them more consistently.

So far Arrowsmith has not been released on Blu-ray, but the MGM DVD has surprisingly good visual quality for a film from this period. (Amazingly enough, you can still buy new VHS copies on Amazon.)

Kameradschaft

Like Clair, G. W. Pabst directed two classic films in 1931, Kameradschaft (“Comradeship”) and The Threepenny Opera. The former is a network narrative, cutting among several characters or small groups of characters as they react to a mine disaster.

The story is set in two villages on either side of a French-German border. Each is a mining town, exploiting what is actually the same rambling mine that has walls and bars in multiple tunnels marking the end of the German portion and the beginning of the French one. When escaping gas triggers a fire and ceiling collapses on the French side, two truckloads of German miners volunteer to go and help the rescue teams.

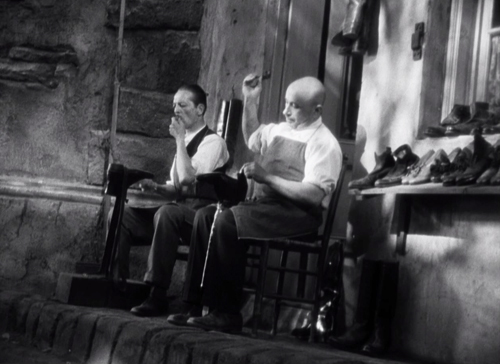

As the title suggests, the film stresses the theme of solidarity among the miners, though Pabst doesn’t paint an entirely rosy picture of this. The German miners coming off their shift argue about whether they should assist their French counterparts, and many declare that it’s none of their business. Pabst stages the debate in a visually interesting locale, the changing room where the mining outfits of the men are stored on ropes or wires up by the ceiling (above and below, left). The leader of the group which goes to help with the rescue is played by Ernst Busch, a well-known Communist actor-singer who was also in the original stage version of The Threepenny Opera and Pabst’s adaptation, as well as Slatan Dudow’s Kuhle Wampe (1932), from Brecht’s script. His presence as one of the main characters in the network plot–and the one who spurs others to volunteer as rescuers–helps give Kameradschaft a distinctly leftist tone.

As with many other films set in coal mines, the mine itself was an elaborate and convincing studio set (above right). One collapsing area of a mine looks much like another, but Pabst found ways to vary the action from scene to scene. Variety is added through a contrast in the main characters being followed. An old ex-miner sneaks into the mine to search for his grandson. Three German miners who didn’t go in the trucks to the French side decide to make a rescue effort on their own, breaking through the barred underground border to do so. They end up alongside the old miner and his grandson, trapped in the underground stable, where the presence of a placid but doomed horse adds a poignancy to the scene. At intervals the drama going on among the mothers, wives, and sweethearts of the French miners clustered at the gates is shown.

The weaving together of the various threads of action creates a strong sense of suspense. No one character can be singled out as the protagonist, the one who might be expected to survive. Some miners and rescuers escape, but there are many who die or suffer serious injuries.

Despite the emphasis on the comradeship of miner of both nationalities, the Germans definitely come off better. Their rescue team is well-equipped and efficient, while the French workers deal with problems like an elevator being out of commission. It probably would never have occurred to Pabst and the others involved to make a film where French miners help rescue German ones–and it probably would not have been greenlit by the production company if they had. On the level of the individual miners’ actions, however, the notion of working-class solidarity comes across.

Kameradschaft is available on DVD and Blu-ray from The Criterion Collection.

Tabu: A Story of the South Seas

Tabu was Murnau’s final film. (The opening scene of the hero fishing with his friends was shot by intended co-director Robert Flaherty, who soon quit due to disagreements with Murnau.) It deals with Matahi and Reri, who live a joyful life on unspoiled Bora Bora until an elderly man from a nearby island arrives and announces that the “Virgin sacred to our gods” has died, and Reri is to be her successor. Matahi rescues her, and the two flee to another island which has been colonized by the French. They have established a pearl fishery and hire local men to dive for pearls. Matahi proves expert at this, but not understanding what money is, he soon gets himself deep into debt by signing IOUs.

Rather than using Hollywood stars, Murnau cast local unprofessionals. As the credits announce, “only native-born South Sea islanders appear in this picture with a few half-castes and Chinese.”

The two leads are appealing characters, and the images take advantage of the unspoiled scenery of Bora Bora (below left). Floyd Crosby earned an Oscar for Tabu‘s cinematography.

Tabu is a far cry from Murnau’s German films, but Nosfertu‘s famous shot of the vampire’s ship sailing eerily into the frame from offscreen is echoed as a motif here (below right).

The original version released by Paramount was released on DVD by Milestone. A restoration of the original cut of the film is available on DVD and Blu-ray from Kino Classics in the US and Eureka! in the UK, both with numerous supplements. A helpful comparison of these versions is available here.

La Chienne

I think it is safe to say that most critics and historians consider La Chienne the film where Renoir’s distinctive traits as a director began to emerge. I have seen most of the early Renoirs, but long enough ago that I can’t make a comparison. It does seem to me, though, that it is quite different from his previous work.

Maurice Legrand, the protagonist played by Michel Simon, is the most Renoirian character. He is a mild-mannered accountant married to a termagant who nags him constantly and forces him to remove from their apartment the paintings and the equipment he uses for his hobby. This sets off the events which follow, as Legrand hangs the paintings in the apartment of a prostitute, Lulu, with whom he has fallen in love. Her pimp Dédé concocts a scheme to sell the paintings, which he passes off to a dealer as the product of an American painter named Clara Wood. Even when Lulu explains what happened to the paintings, Legrand is so besotted that he raises no objections.

Although “la chienne” of the title is clearly Lulu, it might refer to Adèle Legrand as well. “Chienne” is more-or-less the equivalent of the English “bitch,” meaning both a female dog and an obnoxious woman, which Adèle certainly is. In their first scene together, she berates Legrand at length, comparing him unfavorably with her first husband, whose portrait in military uniform looms over them (above). Legrand does not rebel but answers in quiet sarcastic comments and ultimately obeys her order about the paintings.

In French, “la chienne” has the additional meaning of a prostitute, clearly referring to Lulu. Legrand is trapped between a constantly angry wife and a prostitute skilled in behaving in a docile fashion, pretending, as she finally admits, to love him solely in order to maintain the flow of money from the paintings. This admission finally drives him to fight back, killing Lulu. He ends up as a jovial tramp, foreshadowing Simon’s later role as Boudu in what is arguably Renoir’s first true masterpiece.

Stylistically the film does not strongly resemble Renoir’s major films of the mid- to late 1930s. Still, the scene in which Dédé and his friend approach an art dealer in their first attempt to sell one of Legrand’s paintings consists of a longish take of nearly two minutes, with staging in depth (below) when the dealer returns from a search and a track-in to a closer framing for the negotiations. Also, the film starts as a puppet show, with puppets introducing the main characters, whose images are superimposed over the little stage (bottom). This looks far forward to his final film, The Little Theatre of Jean Renoir (1970).

La Chienne is available on Blu-ray and DVD from The Criterion Collection.

Tokyo Chorus

Last year Yasujiro Ozu made his first appearance on this list for That Night’s Wife. This year it’s Tokyo Chorus (or Chorus of Tokyo). With sound barely established in Japan, Ozu made this and several subsequent films silent.

As the Criterion Collection liner notes explain, Tokyo Chorus combines the three genres Ozu had worked in before: the student comedy, the salaryman film, and the domestic drama. The student comedy subject gets disposed of early on, with the first scene showing the a comically strict teacher scrutinizing his class, lined up military-style; the protagonist, Shinji, tries some mild defiance by being late and showing off (below left).

Soon he has graduated, though, and is working in an office where the employees are awaiting their year-end bonuses. Just as quickly, Shinji is fired for protesting when an elderly colleague is fired just before his retirement and pension payments.

The rest of the film seems like a practice piece for I Was Born, But … (1932) and other Ozu films involving bratty kids who make demands on their parents. In this case Shinji’s son insists that his father buy him a bicycle and pesters him until he finally gets it (above right). As in the later film, Shinji is humiliated by having to take a job helping his old teacher to publicize his curry cafe.

Ozu’s growing mastery of editing for comedy is shown off in the early scene when the office employees try to find out how big a bonus their colleagues have received. Shinji sneaks away to the restroom to open his envelope, pretending he has gone to use a urinal. A low-height shot shows another man coming in, with the swinging doors of the urinal area showing him only from the waist down. Shinji, just about to open his envelope, glances off and sees him. A reverse shot shows the colleague stopping and staring, clearly more interested in Shinji’s bonus than in using the urinals. Shinji gives up, pretends he is just there to relieve himself, and a final shot shows him departing still not knowing how big his bonus is.

By this point, Ozu has mastered balancing comedy and pathos, a mixture of tones that will reappear in many of his future masterpieces.

Tokyo Chorus is has been released on DVD, appropriately enough along with two of those future masterpieces, I Was Born, But … and Passing Fancy (1933), by The Criterion Collection.

City Lights

I must admit that I do not admire City Lights as much as The Gold Rush and The Circus, which featured in my ten-best lists of 1925 and 1928. I think it has some narrative problems.

For one thing, the blind flower seller as a love interest is pretty passive and doesn’t allow many opportunities for generating humor. In The Gold Rush, Chaplin had the inspiration to introduce a dream sequence about the dance-hall girls, including his beloved Georgia, coming to dinner with him. He then inserted his classic gag, the dance of the rolls. Much of the action in The Circus involves the heroine, as with the magic act into which the Tramp stumbles. The flower seller mainly generates pathos, right up to the ambiguous ending. (I have seen commentators take the ending as a clear indication of a budding romance between the pair, but I think we get no clear indication that her gratitude for the help the Tramp has provided will blossom into love.)

Chaplin needed to fill out the film with action beyond the few scenes involving the flower seller. Much of the action involves the Tramp’s on-again, off-again friendship with the eccentric millionaire, which is a weak premise to carry so much of the narrative. This character treats the Tramp as his closest buddy when drunk but then fails to recognize him when sober. This happens three separate times and gets a bit repetitious in a way not seen in other Chaplin films. The main contributions of the millionaire to the plot are to give the flower seller the impression that the Tramp who buys her flowers is a wealthy man and to give the Tramp the money for the flower seller’s eye-restoring treatment. The character of the millionaire does create some humorous bits, as when the pair eat spaghetti and the Tramp gets a curly streamer mixed in with his and keeps on eating it. I can’t help contrasting the millionaire with the Mack Swain character in The Gold Rush, whose interactions with the Tramp generate so many hilarious gags.

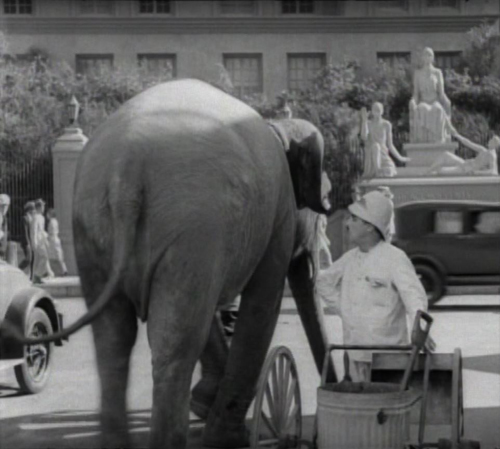

There are admittedly other funny scenes, especially early on, when the Tramp is discovered asleep on the lap of a statue being unveiled before a crowd or when he becomes a street cleaner to earn money for the flower seller and is immediately confronted with a group of horses and, as a topper, an elephant passes.

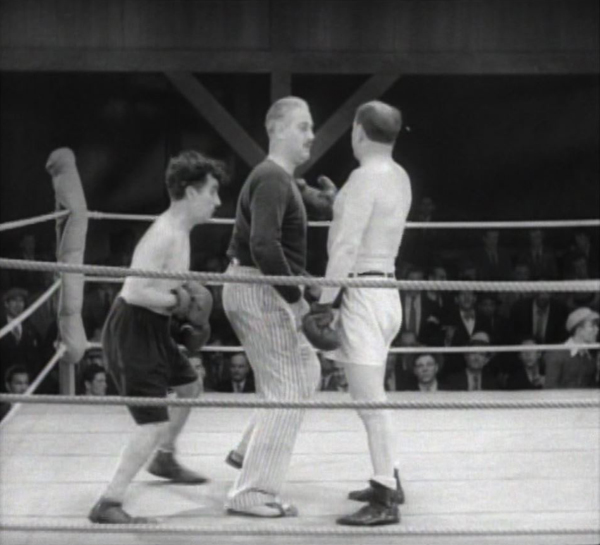

Later on in the film, though, the plot premise of earning money to help the flower seller have an operation to restore her sight generates one of the funniest scenes in all of Chaplin’s work. He agrees to participate in a fixed boxing match, with his opponent going easy on him and the two splitting the purse. The opponent is replaced by a tough guy who clearly has no intention of playing nice. The Tramp’s tactics to avoid being beaten up involve dancing around directly behind the referee at first (top of this section) and then, in a dazzling bit of choreography, the three figures move around the ring, changing places repeatedly so that the Tramp is sometimes behind the referee, sometimes behind his opponent, and so on. It is reminiscent of the scenes in the hall of mirrors as the Tramp is chased by a pickpocket and then by a policeman in The Circus, with the characters and their reflections dodging in and out of view.

Chaplin famously refused to allow spoken dialogue in his film, despite the fact that the transition to sound was well established in the USA by 1931. He restricted the track to music and sound effects, a tactic he carried over to Modern Times as late as 1936, though there the Tramp’s voice is heard for the first and last time singing a nonsense song. Chaplin retired his long-time character thereafter.

City Lights is available on DVD and Blu-ray from The Criterion Collection.

Odna (Alone)

When I was in graduate school, the only film by Grigori Kozintsev and Leonid Trauberg widely known outside the Soviet Union was their 1926 adaptation of The Cloak, which appeared in my best-ten list for that year. Then people discovered, to some extent, The New Babylon, which appeared in the entry for 1929. I suspect that few people have seen, or even heard of, their marvelous first sound film, Odna.

It was planned as a silent film, but delays permitted the use of sound technology to add a track to it. The main element of the track is Dimitri Shostakovich’s musical accompaniment. (He had also composed the musical accompaniment for The New Babylon.) The music comments on the action, often in a mocking way. Occasionally there are sound effects, and very occasionally, brief lines of dialogue, recorded and added after the filming.

The plot centers around a young teacher fresh out of school, Yelena Kuzmina (played by Yelena Kuzmina, who also played the protagonist of The New Babylon).

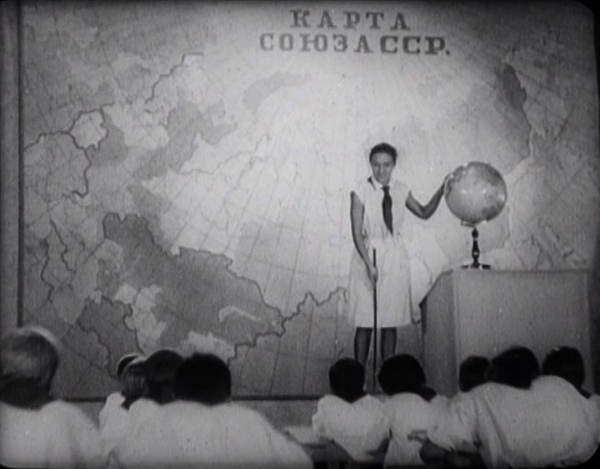

The first section of the film is played with an absurdly jolly exuberance. Yelena is engaged to a handsome young man, and a lively montage of shots shows her visions of the ideal life she plans to lead with him in Moscow, including window-shopping for expensive sets of dinner crockery, playing a musical duet at a cafe (below left), and teaching attentive children seated in neat rows in a well-equipped classroom (top of section). Shostakovich’s music is ridiculously cheerful, and a song about how beautiful life will be plays over a shot of Kuzmina’s fatuous grin (below right).

The tone switches abruptly as Kuzmina receives an assignment to a teaching post in a remote, mountainous primitive district of Siberia.

Devastated, she lodges a complaint, which seems likely to succeed. An elderly man in the office tells her that she’s right to try to change her assignment (below left). She erupts, “I’m going anyway!” This is one of the few post-dubbed lines.

Upon arrival in the Siberian district, she encounters a dead horse’s skin on display (below right); this returns as a motif to emphasize how primitive and in need of education the area is. At first the villagers react with indifference or antagonism, seeing no point in having their children go to school. Oddly enough, the local Soviet official is lazy and also indifferent, leaving her alone with no aid in convincing the villagers to accept her. (This negative depiction of the Soviet official later got the film banned, despite its considerable popularity upon its initial release.)

Apart from encouraging teachers to accept whatever school they were assigned to, the film has the anti-Kulak theme that was common in Soviet films about the countryside. (See the discussion of Eisenstein’s The General Line in the 1929 entry.) A wealthy local landowner has secretly sold off the sheep that technically belong in common to the villagers, whose main source of income is the wool. Kuzmina exposes the theft and helps the local people resist it, thus finally gaining their trust.

The next-to-last reel of the film, in which the landowner tries to kill Kuzmina, is missing. A restored version of the film accompanied by a reconstruction of the Shostakovich score was released on Dutch and German DVDs in 2007. (The frames here are from the Dutch DVD.) It includes a long series of intertitles describing action in the missing reel, drawn-out so as to match the length of the music, which does survive. As far as I can tell, these DVDs are no longer available. I am reluctant to recommend a version on YouTube, derived from the German DVD and superimposing English subtitles on German ones, on top of Russian intertitles. It does seem to be the only widely available way to see the film at this point, so for those who can put up with the clutter and the poor quality of the online version, it is here. A complete recording of the charming music is still available.

La Petite Lise (1930)

My tenth film is a holdover from last year. I consider Jean Grémillon’s La petite Lise a film worthy of the top-ten list, but when compiling last year’s list I somehow misremembered it as being from 1931. It just goes to show that one should double-check on such things.

Decades ago, I first saw La petite Lise in a 35mm print on an editing table at the Cinémathèque Royale de Belgique (now the Cinematek). I finally saw it on the big screen in 2015, when our UW Cinematheque ran a few Grémillon films in 35mm. Then-graduate student Jonah Horwitz provided the program notes.

Grémillon is best known outside France for the trio of films he made during World War II: Remorques (1941), Lumière d’été (1943), and La ciel est à vous (1944). Criterion has released a box set of all three as Jean Grémillon During the Occupation. Some of his other films are available on disc, as a search of the director’s name on Amazon.com or amazon.fr reveals (including some with English subtitles).

The simple plot involves Berthier, who is serving a long sentence in a prison in Cayenne for having killed his wife in a fit of jealousy. Heroic behavior on his part during a recent fire has led to an early release, and he expresses his desire to see his daughter, Lise, now grown up. All this sets us up to be sympathetic toward him, despite the fact that he is played by by Pierre Alcover, a large, rather sinister looking actor. (Best known to modern audiences, I suppose, as the corrupt banker in L’Herbier’s L’Argent.) Unbeknown to him, Lise has been working as a prostitute but has now ended that in anticipation of marrying André. The pair are in desperate need of obtaining 3,000 F within 48 hours to buy a small house.

Berthier’s reunion with Lise is joyful, and he manages to find a job with his old boss, who gives him a generous advance on his salary. Knowing nothing of this, Lise and André visit a Jewish pawnbroker who André believes has cheated him in the past. When he threatens the pawnbroker, a fight breaks out, and Lise accidentally kills the man. Berthier learns of her past and of the killing, and his great love for her leads him to turn himself in as the killer.

The story is quite touching, in large part because Alcover and Nadia Sibirskaïa (who played the younger girl in Menilmontant) convey the deep love between the pair.

Grémillon adds some unconventional touches which have little direct relation to the plot and are largely dependent on sound. These give the simple plot some variety.

The opening, for example, takes place in the Cayenne prison, with Berthier learning of his pardon from the warden. In the crowded dorm, he reveals to two fellow convicts that his good fortune makes it impossible for him to participate in a planned escape. He shows them a photograph of Lise as a child. Most of the extended dorm scene, however, consists of fairly tight shots of other men’s activities, all packed into the crowded room. The soundtrack, rather than catching scraps of dialogue, remains a loud babble of many men talking at once. These shots tell us us next to nothing about the narrative, beyond suggesting the grim conditions to which Berthier faces returning to at the end. It does, however, create an effective atmosphere of the prison as a backdrop to occasional shots of Berthier gazing at the photo of Lise.

Another example is a scene late in the film, when, having learned of the killing, Berthier goes looking for André. He tries to enter a nightclub, but it is too crowded. He stands watching with several others through the window as a Black dancer performs a lively number for a mixed Black and white audience. For a brief interval, the scene becomes a musical number, extending to the point where couples start dancing, with Berthier becoming quite peripheral to the action. The performer and dancers add nothing to the story, but the scene is delightful in itself.

These and other moments draw us away from the linear progression of the story and make La petite Lise one of those small, simple films that transcend their apparently modest nature–like those of Jean Epstein and Dimitri Kirsanoff.

La petite Lise remains difficult to see. It has never, as far as I know, been available on home video. Grémillon’s film is not on YouTube, but there are several clips from key scenes. (All are pretty poor in quality, and I haven’t seen a good print of it. If elements survive in archive, it seems a major candidate for restoration.) An excerpt from the scene in the prisoners’ dorm near the beginning gives a good sense of the babble of voices. The Black dancer’s number as Berthier searches for André is shown nearly in its entirety. Both of these were put up at the time of the Cinematheque screening in Madison. There are some other brief scenes: the visit to the pawnbroker leading up to the murder, the scene of Berthier applying to his former boss for a job (which includes a sound bridge from the previous scene of Lise at home), and the scene in a restaurant which Lise and André visit in the hope of establishing an alibi. Otherwise, keep an eye open for it if you live near at archive that has public screenings.

For a look at Ford’s flashy style in his earliest features, see here. For a defense of How Green Was My Valley‘s Oscar win over Citizen Kane for best picture, see here.

My video essay, “Mastering a New Medium: Sound in M“ is number 11 in the series “Observations on Film Art” on The Criterion Channel.

La Chienne (1931)

Dietrich before von Sternberg and von Sternberg before Dietrich

Thunderbolt (1929)

Kristin here–

In my entry on the ten best films of 1929, I suggested that that particular year, hovering as it did between silents and talkies, was relatively poorly represented on home video. Now Kino Lorber has released two films from that year that both entertain us and contribute to our knowledge of the late 1920s cinema.

In that entry I lamented the fact that Josef von Sternberg’s marvelous early talkie Thunderbolt had not had a proper DVD or Blu-ray released. I expressed hope that one of the home-video companies specializing in historically important classics would finally make it available. The Kino Lorber release finally allows historians and cinephiles access to this little-known masterpiece.

If Thunderbolt was a legendary film that called out for such a release, the 2012 Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau Stiftung restoration of Kurt Bernhardt’s The Woman One Longs for reveals this previously forgotten film to be, if not a masterpiece, a very good film. It’s also completely typical of a trend of the late 1920s that I have termed the International Style.

Coincidentally, von Sternberg and Dietrich, so closely connected in our minds, link the two releases. Thunderbolt was the director’s last film before beginning his series with Dietrich, and The Woman One Longs for was Dietrich’s last (and first) starring roll before she worked with von Sternberg for the first time.

I’ll deal with it first, since I don’t want it to be overshadowed by Thunderbolt.

The Woman One Longs for

The standard story has Marlene Dietrich claiming that The Blue Angel was her first film. Seemingly she wanted to suggest that von Sternberg’s use of her in a series of star vehicles created her career. The image above, of her staring through a frosty train window, might easily be mistaken for a von Sternberg shot. In fact it’s from her previous film, The Woman One Longs for (Die Frau, das der man sich sehnt, aka The Three Lovers), directed by Bernhardt.

The Jewish director barely made his escape from the Nazis, working during the 1930s in France and then shifting to Hollywood. There, under the name Curtis Bernhardt, he made many films up to the 1960s, perhaps most notably the Joan Crawford psychological drama Possessed (1947) and the Rita Hayworth vehicle Miss Sadie Thompson (1953). That was an adaptation of Somerset Maugham’s “Miss Thompson” (previously filmed by Raoul Walsh as Sadie Thompson, starring Gloria Swanson, in 1927 and by Lewis Milestone as Rain [a new title that had replaced the original name of the short story], starring Joan Crawford).

The plot of The Woman One Longs for is straightforward melodrama. The protagonist, Leblanc, is expected to rescue his family’s factory, tottering on the brink of bankruptcy, by marrying a wealthy heiress who loves him but who leaves him cold. He marries her, but on their honeymoon trip aboard a train to the south of France, he suddenly becomes fascinated by a mysterious beauty, played by Dietrich. She seemed to be under the sadistic control of Dr. Karoff. The latter is played by the great actor of the Expressionist theater, Fritz Kortner, familiar to most modern spectators as Dr. Schön, who keeps Lulu as his mistress in Pandora’s Box (also 1929). Leblanc becomes obsessed with saving Dietrich from her captor.

The plot is entertaining enough, but the real interest in the film, at least for David and me, is Bernhardt’s direction. It’s quite skillful, even flashy. Moreover, Bernhardt had clearly been seeing many of the major films of the 1920s from Germany, the USSR, and France. Like many other directors of the late 1920s, he blends them seamlessly into what I have called the “International Style.” (See Chapter 8 of Film History: An Introduction.)

The film starts in a setting done in a style familiar from many German films of the era, with a camera following a character through an atmospheric, faintly Expressionist street clearly built in a studio (below left). Even after the Expressionist movement ended in early 1927 with Metropolis, German films continued to use settings influenced by the style to represent old buildings or poor neighborhoods. Compare the opening shot of The Blue Angel (below right), the only Expressionistic setting in the whole film.

But Bernhardt has seen Soviet films as well. The early montage establishing the Leblance family’s factory uses the quick cutting, dramatic angles, and dissolves that such scenes have in so many Soviet and European films of the era (below left). A fight scene between Leblanc and Karoff uses fast editing, canted compositions, and camera reframing (below right).

Bernhardt has almost certainly seen L’Herbier’s L’Argent of 1928, with its streamlined sets (left) and low-angle framings shot with wide-angle lenses (right). Compare the latter with the low-camera-height shot of the Paris Bourse at the top of the L’Argent section in the 1928 entry linked immediately above.)

Bernhardt had also clearly seen Underworld, for the New Year’s party that forms the climactic scene of his film imitates von Sternberg’s party scene fairly obviously. The action centers around the two main male characters’ struggle over the heroine, with two count-downs raising the suspense: the beauty contest in Underworld and the approaching midnight signalling the new year in The Woman One Longs for. The hanging streamers that increasingly dominate the setting are, however, the giveaway for von Sternberg’s influence on Bernhardt (see bottom).

Speaking of influence, there is a moment in the party scene when the drunken Kaross pops a startled child’s balloon with a cigarette. Maybe this is a common trope in films, but the only other example I can think of is Bruno’s similar gesture of casual cruelty in Strangers on a Train.

The Woman One Longs for also contains a reference that we might today call an “Easter egg.” At the end, Karoff is arrested in the luxury hotel where the three main characters have been staying and where the New Year’s party take place. The manager insists that in order to avoid a scandal, the police must escort him out of the building via the “Hintertreppe” (backstairs). One of Kortner’s major roles had been the devious, obsessed postman in Leopold Jessner’s Hintertreppe (1921), one of the few other classics by which Kortner is known today.

Thunderbolt

I have already sung the praises of von Sternberg’s pre-Dietrich films on this blog. I find his naturalistic first feature, The Salvation Hunters (1925) heavy-handed, but with Underworld (1927) he abruptly hit his stride. To me it and The Docks of New York (1928) are his masterworks–those and Shanghai Express (1932), arguably the best of his Hollywood Dietrich films. The Last Command (1928) is excellent but not up to that level. I discussed these three when The Criterion Collection released them as a set in 2010. That set went out of print but is fortunately now available in Blu-ray. I put Underworld in my ten-best list for 1927 and The Docks of New York in the 1928 list. As I mentioned at the outset, Thunderbolt made the 1929 list.

There I briefly discussed the remarkable compositions and use of offscreen sound in the lengthy prison scenes of the title character on Death Row. Watching the new Blu-ray in preparing this entry, I was struck even more by the early scene in the Black Cat, a Black-run nightclub where we are introduced to Thunderbolt and his relationship to Ritzie, the heroine. As in the silents, von Sternberg’s habit of staging compositions with obstructing objects in the foreground is apparent. Note the entrance of Thunderbolt and Ritzie with a set element both framing and obstructing them (see top). Later a scene as two patrons of the club gossip about Thunderbolt partially blocks the faces, particularly of the one on the left.

The whole scene is marvelously enhanced, as I said in my 1929 entry, by the inclusion of Theresa Harris’ complete rendition of “Daddy, Won’t You Please Come Home.” It’s hard to think of another mainstream Hollywood film in which a Black cultural situation is used so naturally and with so much respect.

The Black Cat sequence ends with a police raid on the club. The cinematography at this point is pure film noir. (See image at the top of this section.)

As I said in the earlier entry, the one flaw in the film is the tepid central couple played by Richard Arlen and Fay Wray. Given the excellence of the Black Cat sequence and the lengthy prison scenes, that flaw is minor indeed.

The Woman One Longs for (1929)

German classics for the pandemic and beyond

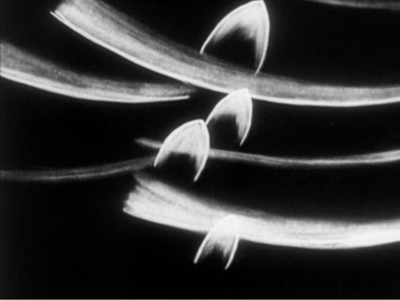

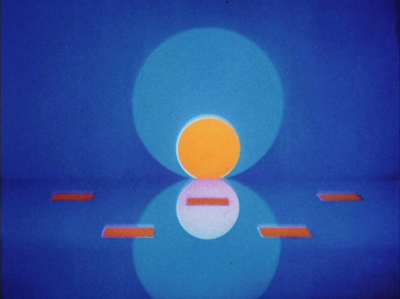

Kreise (Circles, 1934).

Kristin here:

Recently I acquired discs of the work of two important German directors of the silent and early sound periods. The first is a new Blu-ray/DVD edition of Paul Leni’s Waxworks from Flicker Alley. The second is a pair of DVD releases of Oskar Fischinger shorts, which I recently ordered from The Center for Visual Music, co-founded by Fischinger’s daughter Barbara. All are vital for anyone interested in these two major figures in German film history.

Telling scary stories

As with so many cinema classics, I first saw Paul Leni’s Wachsfigurenkabinett (Waxworks) during my grad-school years. The print was 16mm and very dark. It was hard to get any real sense of its pictorial design. I had seen Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari in my first film course and had been hugely intrigued by how different it was from the movies I was used to. It was one of the films that lured me into cinema studies. Since then I have been partial to German silents of the 1920s and especially those of the Expressionist movement. Waxworks was made in 1924, which also saw such high points of the decade as Fritz Lang’s Die Nibelungen, F. W. Murnau’s The Last Laugh, and Carl Dreyer’s second German-made film, Michael. Still, the poor print did not give much sense of how it fit into the creative trends of the mid-1920s. Later I saw it in a 35mm archival print on a flat-bed viewer. That print was also too dark to allow a judgment of its aesthetic and historic importance.