Archive for the 'National cinemas: Germany' Category

Paris-Berlin-Brussels express

Doktor Satansohn.

Our trip to Europe has come to an end, and so we finish with a post scanning some highlights.

The magic lantern learns new tricks

DB here:

What am I seeing? Many avant-garde films pose this question. Mainstream fiction film and documentary cinema have mostly relied on the idea that the image should be recognizable as “what it is.” But one strain of experimental film has worked to delay or even prevent us from making out what’s in front of the camera.

Sometimes we lose our bearings only briefly, as when we eventually identify pot lids in Ballet Mécanique or bits of sunlit linoleum in Brakhage films. Sometimes language points out what’s really there. The titles of Joris Ivens’ Rain and the Eames’ Blacktop: The Washing of a School Play Yard allow us to enjoy the ways that ordinary sights can yield unexpected abstraction. Sometimes we toggle back and forth, as when in Ken Jacobs’ Tom, Tom, the Piper’s Son recognizable human figures, however grainy, jump into sheer blotchiness and then back into something like legibility. But other times we can’t ever tell what we’re seeing. Brakhage’s Fire of Waters offers one of the best examples I know, with its jagged bursts of light in a smoky void.

What am I seeing? The uncertainty was doubled during my visit to Ken Jacobs’ Nervous Magic Lantern performance at the Cinémathèque Française. I say “doubled” because at least with Fire of Waters and Tom, Tom I knew I was watching a film. With this display, What am I seeing? started as a question about the format itself. Was it a film, a video, or something else?

Then the question became the customary one. Off-white textures—pebbly, dribbly, stalagmite-like—swim in and out of focus. Some are viscous and globular, some are like tangled foliage. They seem to spiral, but actually (I put up a finger to measure) they barely move. The effect of movement is given by pulsations of pure black, breaking the lyrical effect of the surfaces with a harshness that becomes aggressive. Aggressive as well is the soundtrack, blocks of sound from subway platforms and traffic and kitsch Latin percussion, all played at high volume. The surfaces just keep shifting and not shifting, sort of rotating while jabbing out at us, lovely and anxiety-inducing at the same time.

At the end of the performance, people crowded around the cardboard booth in the middle of the theatre. As Ken and Flo Jacobs packed up, they showed how they had generated the effects. What had I been seeing? Neither a film nor a video but a true magic-lantern display, assembled on the spot. But what had I been seeing? Something created with home-made equipment of a startling simplicity. (Strapping tape was involved.) Our magicians explained their tricks, like magic-lantern operators of earlier centuries explaining the science behind their shows. But I think it’s best that you not know until after you have a chance to see what they create.

In earlier entries (here and here) Kristin and I have praised Jacobs’ films for showing how very slight adjustments in technique or technology can create disturbing cinematic illusions. In this vein, the first item on the Cinémathèque program, a video called Gift of Fire, turned Louis Le Prince’s brief 1888 street scene into a 3D movie. (The homage was appropriate because Le Prince experimented with multiple-lens cameras.) The Nervous Magic Lantern performance generated a different sort of illusion, one conjuring up micro-landscapes and otherworldly vortices. In all, Jacobs makes us realize how many evocative effects are still to be discovered by tinkering with images thrown on a screen.

Detour to Berlin

KT here:

As David mentioned in last week’s entry, I took a week in the middle of our visit to Europe for research at the Ägyptisches Museum in Berlin. The staff there welcomed me into their storerooms, and I spent the days looking at fragments and the records of their discovery and the nights downloading and backing up my photos. No time for filmgoing. The most I managed was a trip to the well-stocked arts bookshop Bücherbogen, which has one of the best selections of film books to be found in Germany. Our old friend, experimental filmmaker Carlos Bustamente, met me there, and we had a quick cup of tea–most welcome on a cold morning when the results of the biggest snowfall in decades were still blanketing many sidewalks and roads.

I did note one film-related phenomenon, however. Every day I took the S-Bahn from Savignyplatz to Friedrichstrasse. The tracks pass directly across the street from the Theater des Westens (that is, the western part of Berlin). It was playing Der Schuh des Manitu, a musical version of the  highly successful 2001 German film of the same name. (I hope the publicity photo at the left was taken in warmer weather than I experienced.) I mentioned the film here, in reference to the fact that every major producing country, and some minor ones as well, turn out their own local comedies, films that don’t travel well but are very popular locally.

highly successful 2001 German film of the same name. (I hope the publicity photo at the left was taken in warmer weather than I experienced.) I mentioned the film here, in reference to the fact that every major producing country, and some minor ones as well, turn out their own local comedies, films that don’t travel well but are very popular locally.

By now it’s a familiar phenomenon in the U.S. for successful Hollywood films to be turned into stage musicals. It wasn’t always so. Back in the 1950s and 1960s, films were made of popular musicals, sometimes successfully, as with My Fair Lady, and sometimes not, as with Mame. But now the trend is the other way, with everything from Shrek to Hairspray getting the Broadway treatment.

It’s interesting to know that the same thing goes on abroad, though I’m not sure how prevalent such adaptations are. Der Schuh des Manitu, directed by Michael “Bully” Herbig, remains the highest grossing German film. Herbig doesn’t act in the stage play, as he did in the film, but he served as a creative advisor. The musical is a hit, having premiered on December 7, 2008 and it is expected to continue until at least the autumn of this year. There are several clips from both the film and the musical on YouTube. This one, at 8 minutes, gives a generous dose of the show. There are no subtitles.

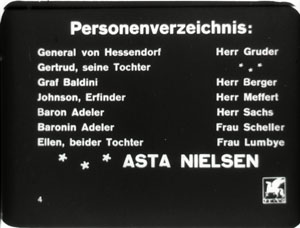

I had only a couple of days back in Paris before we headed for Brussels for the final week of our trip. The German theme continued, since a few of the 1910s films David needed to see at the Cinematek here were German. The one I most wanted to see was Edmund Edel’s 1916 feature, Doktor Satansohn. Its main claim to fame is probably the fact that Ernst Lubitsch plays the title role. My book with Lubitsch started with his 1918 move to features, when he began to concentrate more on directing and less on acting. By 1920, with Sumurun, he appeared onscreen for the last time; being discontented with his performance as the tragic clown, he decided it was time to move behind the camera for good.

In the short films he starred in before 1918, Lubitsch often played a brash, ambitious Jewish youth, as in Der Stoltz der Firma (“The Pride of the Firm,” 1914). In Doktor Satansohn he’s a physician with a magical machine that transforms older women into beautiful young ones. We’re first introduced to a couple and the wife’s mother. When the latter makes a pass at her son-in-law and is rejected, she seeks the doctor’s help. His machine works by capturing the wife’s essence in a statuette and making the mother look like her daughter. Problem is, every time she’s about to kiss the husband, the doctor pops up with his devilish leer, visible only to the “wife.” David and I decided that the film is a comedy, though perhaps one only Germans of the day would find truly amusing. For one thing, the title character is clearly a Jewish caricature, one played to the hilt by Lubitsch. He decorates his machine with the Star of David and a Hebrew inscription (not to mention vipers and an image of Saturn).

Stylistically it’s a fairly conventional film for its day, though the black background of the doctor’s office, with its stylized youth machine and satyr-like bust, gives a hint of Expressionism to come. (See our topmost image.) Inevitably near the end there comes the moment beloved of historians of pre-World War II German cinema. The real daughter, released from her imprisonment in the statuette, confronts her double in the doctor’s waiting room. The Doppelgänger motif strikes again.

I wonder if German films actually have more Doppelgängers in them than appear in other national cinemas. Do they really reflect the disturbed soul of the nation? Or did the possibilities of filmic special effects draw moviemakers to try and multiply single figures? Georges Méliès and Buster Keaton used in-camera techniques to multiple their own figures in virtuoso displays. I recall being impressed by The Parent Trap‘s duplication of Hayley Mills when I saw it as a kid, and the whole notion of a single actor playing twins and other lookalike relations is a common enough convention. In Doktor Satanssohn, the doubled figure appears only in this one shot, and it’s the leering Lubitsch, delighted with his own nastiness, who walks off with the picture.

The 1910s, again, and still

DB again:

We saw Doktor Satansohn while I was studying staging and cutting strategies of the 1910s, thanks to the remarkable holdings of the Royal Film Archive of Belgium, also known as the Cinematek. My comments on last summer’s visit are here.

Another German film, in a choppy Russian print, vouchsafed a new glimpse of Asta Nielsen. In Totentanz (Urban Gad, 1912), she plays a guitarist-dancer who must take to the stage to support her infirm husband. She attracts the devotion of a composer, and soon she feels attracted to him. Torn between desire and duty, she snaps during a rehearsal of his latest piece, “Totentanz.” In a chilling gesture, she uses his dagger to slice her lute strings.

Soon the two are locked in a violent erotic struggle, and a stabbing ensues. In all, melodrama as ripe as one could want.

As ever, I was happy to have my hypotheses about tableau staging confirmed by several of the titles I saw. A minor French bedroom farce, Le Paradis (M. G. Leprieur, 1914 or 1915), had a brief passage of the sort of blocking and revealing we find in many films of the period. The painter Raphael Delacroix (no kidding) is pretending to be the lover of Claire Taupin to deflect the advances of randy M. Pontbichot. But Claire is actually the mistress of M. Grésillon. . . .

First, very frontal staging strings out Pontbichot, Raphael, and Claire. The older man relents in his pursuit of her.

In the vivid depth characteristic of the tableau tradition, Pontbichot withdraws. But his position accentuates that central door, which starts to open.

Most remarkably, Pontbichot ducks almost entirely behind the couple, giving pride of place to M. Grésillon’s arrival in the center of the shot.

Pontbichot slides out in time to register Grésillon’s outraged reaction to finding his mistress in another man’s arms.

Grésillon rushes to the frontal plane, furious. As ever, a thrust to the foreground creates a major spatial/ dramatic event.

Although the Le Paradis passage is ABC compared to the emotionally powerful patterns of staging we find in Ingeborg Holm (1913), it illustrates how even average films could resort to the blocking/ revealing tactic within the deep-space geometry of the tableau.

More flamboyant was Il Jockey della Morte (1915), an Italian circus film made by the Dane Alfred Lind. Its bold lighting and varied angles on the Big Top recalled the Danish films of a few years before. Halfway through, Lind launches a dazzling chase that features leaps from a tall bridge and bicycling stunts on a cable stretched across a river.

Another Italian film, this time a diva vehicle, suggests that by 1917 1923 (see below) the tableau style was already giving way had given way to scenes organized around close shots. (See below.) L’Ombra (Mario Almirante) starred Italia Almirante Manzini as a lively, trusting wife who becomes paralyzed. While her husband betrays her with her younger protégée, she gradually recovers bodily movement. Yes, a paralyzed diva seems a contradiction in terms, but one small-scale scene shows a remarkable range of emotions. Berta’s hands start twitching, one lifts up, and she stares wildly, as if it were an alien being.

In an earlier scene, Berta had asked that a mirror facing her be tipped upward so that she would never see herself sitting immobile. This shot pays off now, when the hand ascends almost magically into the bit of reflection she can see.

When the hand descends, her astonishment turns into joy. She experimentally shoves the hands together, as if asserting her control.

In the end, she kisses her hands as if they were pampered children.

Manzini runs through many more micro-emotions than I’ve indicated here, but this sample is typical of the ways in which L’Ombra avoides the long-shot choreography of only a few years before and builds a performance out of face, body, and arms in a close framing. The mirror-shot motif shows that fairly careful filmic construction was emerging at this point too.

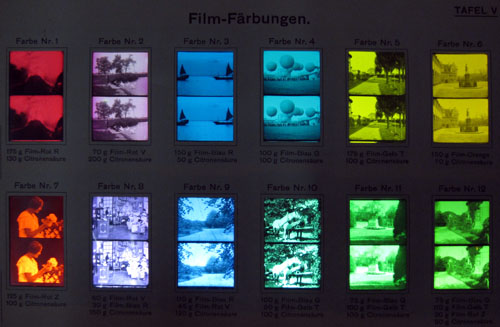

During my stay, I learned more about tinting and toning from the ever-helpful Noël Desmet. On the seldom-seen World War I drama L’Empreinte de la patrie (M. Dumeny, 1915), some images had curious oscillating patches of rusty brown. Noël explained that when Prussian Blue toning was combined with rose tinting, the chemicals eventually reacted to alter the pink cast. An example is shown at the top of this section, though the blue is more saturated in the original.

Once we get back to Madison, I’ll have to sort out all that I’ve learned from these movies. Onward and upward with the 1910s!

For more on Jacobs’ Nervous Magic Lantern, see Scott Foundas’ interview here. The Youtube clip doesn’t do the spectacle justice. If you must know something of Jacobs’ tools, the Dailymotion video from the performance I saw offers some clues. My notions about 1910s staging are laid out in On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light. You can also find several discussions in earlier entries on this site. Just execute a search on tableau.

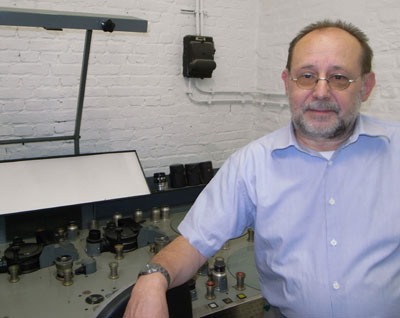

Now is a good time to thank Noël Desmet and Marianne Winderickx, both of whom are retiring from the archive in March. The research that Kristin and I have done over the years owes an enormous lot to them, and of course to the Director of the Cinematek Gabrielle Claes.

P.S. 15 November 2013: Ivo Blom has pointed out that the version of L’Ombra I saw wasn’t from 1917 but rather from 1923. Hence the corrections above. Thanks very much to Ivo! Go here for his blog and information about his newest publication on silent Italian cinema.

A tinting and toning sample card from the early 1920s. Courtesy Noël Desmet.

The ten-plus best films of … 1919

KT here, with some help from DB:

Two entries are enough to create a tradition. Once again, at a time of year when critics are picking their 10-best lists for 2009, we jump back ninety years and give our choices for 1919.

(For our 1917 list, see here, and here for 1918.)

I remarked in last year’s post that it was a bit difficult to come up with ten films, a result perhaps of accidents of preservation or slackening of activity by certain major filmmakers. There was no such problem for 1919, and films had to be bumped off the initial list to keep it to ten. (In fact, you’ll notice we didn’t quite manage to keep it to ten.) Since some people may take these lists as a guide to exploring the cinema of the teens, we’re adding some also-rans at the end, all very much worth watching.

With 1919, we’re approaching the decade when many of the most widely known silent classics were made. Some titles on this year’s list will be very familiar. Erich von Stroheim’s first film came out in 1919, as did Carl Dreyer’s. Ernst Lubitsch, always a prolific director, was particularly busy that year. Other titles are less well-known, still being largely the province of silent-film festivals and archival research.

Three, sadly, are not available on DVD, and some others have to be ordered from sources in their countries of origin. In this day of internet sales around the world, such orders are not difficult. You need, however, a multi-region DVD player.

Charles Chaplin had long since left his knockabout comedy behind and was making more controlled, poetic films by  this point. The Little Tramp was beloved around the world, and numerous impersonators were turning out films to cash in on his popularity. Sunnyside is his most highly regarded film of 1919, in large part because of a dream sequence in which the Tramp wakes up by a little bridge to find himself welcomed by a bevy of wispily dressed young ladies. The subsequent open-air dance displays Chaplin’s extraordinary ability to inject humor into such a scene without marring its lyricism. (The only DVD version currently available in the U.S. is a fuzzy copy.)

this point. The Little Tramp was beloved around the world, and numerous impersonators were turning out films to cash in on his popularity. Sunnyside is his most highly regarded film of 1919, in large part because of a dream sequence in which the Tramp wakes up by a little bridge to find himself welcomed by a bevy of wispily dressed young ladies. The subsequent open-air dance displays Chaplin’s extraordinary ability to inject humor into such a scene without marring its lyricism. (The only DVD version currently available in the U.S. is a fuzzy copy.)

Cecil B. De Mille had begun his series of high-society battle-of-the-sexes films by this point. Male and Female differs from the others in that it is based on a prominent literary source, The Admirable Crichton, J. M. Barrie’s successful 1902 play. The plot involved the butler of a wealthy British family. He becomes their leader when the pampered group is cast away on an unpopulated island. A romance develops between the spoiled daughter, Lady Mary (Gloria Swanson), and Crichton (Thomas Meighan).

De Mille spiced up the story with a fantasy scene based on William Ernest Henley’s popular poem of 1888, “I was a King in Babylon.” It dealt with reincarnation, one of several spiritualist fads of the period, which also included psychic contact with the dead and the fairy photographs that deluded Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Crichton refers to the poem, leading into a scene of him as king in a Babylon. When a Christian slave girl rejects his advances, he orders her thrown to the lions. The scene providesa glimpse of the costume-epic style that De Mille would increasingly turn to as his career advanced.

Henley, by the way, is largely forgotten today, but another of his poems, “Invictus,” inspired Nelson Mandela and lends its name to the latest Clint Eastwood film.

D. W. Griffith released an impressive lineup of features in 1919, despite the fact that he was also acting as the producer for other directors. His output includes a charming set of pastoral stories A Romance of Happy Valley, True Heart Susie, and The Greatest Question; a belated war film, The Girl Who Stayed at Home; a Western, Scarlet Days; and a melodrama that ranks among his most admired films, Broken Blossoms. Griffith’s status within the industry was  reflected by the fact that this same year same the formation of United Artists as a company to distribute films by him and the other founders, Chaplin, Mary Pickford, and Douglas Fairbanks.

reflected by the fact that this same year same the formation of United Artists as a company to distribute films by him and the other founders, Chaplin, Mary Pickford, and Douglas Fairbanks.

Broken Blossoms owes its simplicity to the fact that Griffith was then making a series of films based on short stories. The title of Thomas Burke’s “The Chink and the Child” sounds offensive today, but it was an ironic reference to the epithet forced upon an idealistic young Chinese man who comes to London’s grim Limehouse district and becomes disillusioned. He falls in love with the delicate Lucy, abused by her violent, drunken father. These three form the main characters. Another Chinese man lusts after Lucy, but for once in Griffith’s work, the sexual threat to the innocent heroine takes second place to her abuse by her father. Lillian Gish and Richard Barthelmess convey the quiet resignation that at intervals gives way to Donald Crisp’s vicious outbursts.

Apart from the strong performances from the three leads, the film was perhaps the first to consistently use the “soft style” of cinematography, an approach that borrowed from a recently established trend in still photography. The hazy views of the Chinese setting in the opening and of the Limehouse docks later on would be enormously influential on films of the 1920s.

Raymond Longford is far and away the least known of the directors in this list. Films were increasingly being made in countries outside the U.S. and Europe, but few have survived. Longford’s The Sentimental Bloke is widely held to be the first major Australian film and perhaps the best of the silent era. Based on a verse poem using vernacular language and serialized from 1909 to 1915, it was set among working-class characters and filmed on location in an inner-city district of Sydney. It follows the reformation of the Bloke, a drinking, gambling man reformed by his love for Doreen. The film’s original intertitles, based on the poem and told in first person by the hero, were too colloquial for Americans to comprehend, and the film failed there, even after a new set of intertitles were substituted.

Raymond Longford is far and away the least known of the directors in this list. Films were increasingly being made in countries outside the U.S. and Europe, but few have survived. Longford’s The Sentimental Bloke is widely held to be the first major Australian film and perhaps the best of the silent era. Based on a verse poem using vernacular language and serialized from 1909 to 1915, it was set among working-class characters and filmed on location in an inner-city district of Sydney. It follows the reformation of the Bloke, a drinking, gambling man reformed by his love for Doreen. The film’s original intertitles, based on the poem and told in first person by the hero, were too colloquial for Americans to comprehend, and the film failed there, even after a new set of intertitles were substituted.

The Sentimental Bloke was restored in 2004 and this past April appeared in a DVD set prepared by the Australian National Film & Sound Archive. A supplementary disc includes historical material, information on the new musical accompaniment, and an interview with Longford. A book of historical essays is also included in the box, which is available directly from the DVD company Madman. (Note that although there is no region coding, it is in the PAL format.)

When I was studying film in graduate school, Ernst Lubitsch’s German period was known mainly for the 1919 historical epic Madame Dubarry. There was little known about the two comedies that came out that year, perhaps the most amusing and delightful of all his German films in this genre: Die Austernprinzessin (“The Oyster Princess,” though seldom called by that title) and Die Puppe (“The Doll,” also a little-used name).

It’s hard to choose which of these three is Lubitsch’s best for the year. Ironically Madame Dubarry isn’t watched much any more, and it’s not on the recent DVD set “Lubitsch in Berlin,” though the two comedies are. Complete prints are rare, due in part to censorship. (If the print you see ends with a close-up of the heroine’s head held up after she is executed, you’ve probably been watching a reasonably complete version.) It may seem a bit stodgy upon first viewing, but I warmed up to it during repeated screenings while researching my book on Lubitsch’s silent films. There are many excellent moments: the extended series of eyeline matches when Louis XV first sees Jeanne, the masterfully timed and staged long take when Choiseul refuses to let Jeanne accompany Louis’s coffin, and a meeting among the revolutionaries that ends as Jeanne reacts in horror to their bloodthirsty plans, backing dramatically into shadow in the background (below).

Given how different these films are, I’m going to declare a tie between Madame Dubarry and one of the comedies. Wonderful though The Oyster Princess is, I’m opting for Die Puppe (above). Its story-book opening and stylization are charming. The hilarious scenes in the doll workshop and the monastery full of greedy monks fill out the plot, making it considerably denser than that of Die Austernprinzessin.

As with Lubitsch, when I was first studying film and for many years thereafter, Swedish director Mauritz Stiller was known mainly for one film, Sir Arne’s Treasure (Herr Arnes Pengar), though an abridged version of The Saga of Gösta Berling also circulated. Sir Arne’s Treasure was assumed to be his masterpiece. The gradual rediscovery and restoration of other Stiller films from the 1910s has considerably broadened our view of him. Perhaps Sir Arne’s Treasure is not the solitary, towering masterpiece it was long thought to be. Still, it holds up well upon revisiting.

It is a period piece set in a small seaside community. A group of foreign men massacre most of a family, in search of their mythical riches. They are forced to remain in the village when the ship in which they are to sail becomes  icebound. The surviving daughter of the family unwittingly falls in love with one of the killers.

icebound. The surviving daughter of the family unwittingly falls in love with one of the killers.

Sir Arne’s Treasure was one of the films which gained the Swedish cinema of the 1910s the reputation for brilliantly exploiting natural landscapes. Few silent films have exploited actual winter settings so well. The actors are clearly working in genuine snow; one can sometimes see their breath fog as they speak. Atmospheric shots show the wind sweeping snow across the ice. Stiller uses the blank backgrounds created by the snow to create stark, simple compositions of dark figures and objects.

Kino’s DVD release uses a print from Svensk Filmindustri’s own archives. To my eye, the tinting used is too dark, especially since much of the action naturally takes place in the dark of the northern winter days. Deep blues somewhat obscure parts of the action. Still, the darkness adds to the brooding tone that pervades the story.

Erich von Stroheim’s first film, Blind Husbands, is the only one he completed that has come down to us in more or less its original version. As the director’s artistic ambitions expanded, his studios’ willingness to accommodate the growing  length and scope of his films diminished. His features of the 1920s were re-edited without his consent, most notoriously when the eight-hour naturalistic film Greed (1924) was released in a version that ran little more than two hours. For many the original remains at the top of the wish list for lost films to be recovered someday. (Number one on my list is Lubitsch’s Kiss Me Again, released in 1925 just before his masterpiece, Lady Windermere’s Fan.)

length and scope of his films diminished. His features of the 1920s were re-edited without his consent, most notoriously when the eight-hour naturalistic film Greed (1924) was released in a version that ran little more than two hours. For many the original remains at the top of the wish list for lost films to be recovered someday. (Number one on my list is Lubitsch’s Kiss Me Again, released in 1925 just before his masterpiece, Lady Windermere’s Fan.)

Blind Husbands is my favorite among von Stroheim’s films. It tells its story of sin and punishment with a lighter touch than his later films would. The director plays a would-be seducer of a neglected wife when the group converges in a village for a mountain-climbing vacation. Von Stroheim’s eye for striking compositions against the snow-clad landscapes and his skillful use of the inn’s hallways and doors to convey the characters’ shifting relationships show an already mature grasp of the art form. (See right, where the villain eyes the heroine in her room but is himself watched by the protective guide in the hallway between the rooms.)

Maurice Tourneur’s Victory runs a mere 63 minutes in its current version, but the original footage count suggests that what we have is substantially complete. That’s somewhat short for a feature by a major director at this point in history, but the simple, intense plot, based on a Joseph Conrad short story, benefits from the compression. The protagonist is a man who has escaped his past and lives as a virtual hermit on a South Seas island. Attracted despite himself, he befriends a young woman playing in a visiting orchestra and rescues her from the abuse of the orchestra’s owner and the lustful advances of the local hotel owner. Returning with the woman to his lonely island, he faces the intrusion of three thugs deceived by the vengeful hotel owner into thinking that the hero has riches hidden on his island.

By this point Tourneur has fully mastered the “rules” of classical continuity style and of three-point lighting. Many of the compositions in Victory look like they could have been made in the 1930s. When I first saw the film about thirty years ago, I found the earliest case of true over-the-shoulder shot/reverse shot that I had ever seen:

Since then, David has found an earlier one that sort of qualifies (maybe more on this in an upcoming entry), but this is a purer case.

Tourneur had also developed a distinctive approach to filming settings in long shot with framing elements within the mise-en-scene and figures silhouetted in the foreground (see top). In general the lighting is superb. Few Hollywood directors had reached this level of sophistication by 1919.

Victory has been released on DVD largely because it features Lon Chaney as one of the thugs. Image offers it paired it with another Chaney film. For some reason the titles are out of focus, but the rest of the film fortunately is in good condition and presents Tourneur’s visual style well.

DB’s picks:

Carl Theodor Dreyer began his film career writing scripts at the powerful Danish studio Nordisk. When he started directing, however, World War I had destroyed Nordisk’s markets, and the American cinema was on the rise. Dreyer’s generation was the first to register the impact of the emerging Hollywood cinema, and he displayed his understanding of Griffithian technique in The President (Praesidenten).

The English title should probably be something like “The Head Magistrate” or “The Presiding Judge,” and the plot appropriately sets up a tension between justice and personal obligation. One of Nordisk’s favored genres was the “nobility film,” in which illicit passion plunges a wealthy man or woman into the lower depths of society. Dreyer gave the studio a nobility film squared, using flashbacks to show how two generations of men in a family have seduced working-class women. The present-day drama displays the crisis that ensues when a respected judge realizes that the woman to be tried for infanticide is his illegitimate daughter. Dreyer’s abiding concern for the exploitation of women under patriarchy begins in his very first film.

From the early 1910s, Danish films displayed a mastery of tableau staging and careful pacing. But The President bears the mark of American technique in its bold close-ups and reliance on editing to build up its scenes. (There are nearly 600 shots in the film, yielding a rate of about 8.8 seconds per shot—quite swift for a European film of the era.) Perhaps more important are Dreyer’s efforts to shove aside the heavy furnishings of bourgeois melodrama. Compare the overstuffed set of Hard-Bought Glitter (Dyrekobt Glimmer, 1911) to this daringly bare one, with its sweep of cameos.

In the late teens, other Danish directors were moving toward simpler settings, but The President carries this tendency to geometrical extremes. Dreyer’s walls, bare or starkly patterned, isolate the players’ gestures and heighten moments of stasis. The result is one of the most adventurously designed film of its time, and if some of its experiments do not quite come off, already we can see that impulse toward abstraction that would be given full rein ten years later in La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc. The all-region DVD from the Danish Film Institute provides a somewhat dark tinted copy with original intertitles and English translations.

Dreyer deeply admired Victor Sjöström, who had already given Swedish cinema some of its enduring masterpieces: Ingeborg Holm (1913), Terje Vigen (1917), The Girl from Stormycroft (1917), and The Outlaw and His Wife (1918). Sjöström would go on to make The Phantom Carriage (1921), The Scarlet Letter (1926), and The Wind (1928). Several other outstanding movies he signed remain little known; worth watching for are The Girl from Stormycroft (1917), Karin Ingmarsdotter (1920), and the deeply moving Mästerman (1920; look for this on our list next year). Among these unofficial classics Sons of Ingmar (Ingmarssönerna, 1919) stands out especially.

Dreyer deeply admired Victor Sjöström, who had already given Swedish cinema some of its enduring masterpieces: Ingeborg Holm (1913), Terje Vigen (1917), The Girl from Stormycroft (1917), and The Outlaw and His Wife (1918). Sjöström would go on to make The Phantom Carriage (1921), The Scarlet Letter (1926), and The Wind (1928). Several other outstanding movies he signed remain little known; worth watching for are The Girl from Stormycroft (1917), Karin Ingmarsdotter (1920), and the deeply moving Mästerman (1920; look for this on our list next year). Among these unofficial classics Sons of Ingmar (Ingmarssönerna, 1919) stands out especially.

A prologue shows lumbering, somewhat thick-headed Ingmar climbing a ladder to heaven, where generations of Ingmars sit in dignity around a massive meeting-room (see below). There his father tells him that he must find a wife. But Ingmar then explains that he once took a wife, with unhappy results. Some long flashbacks ensue, showing Ingmar forcing a young woman to marry him. The plot takes some doleful turns, with the result that the woman is sent to prison.

Running over two hours (and initially released in two parts), Sons of Ingmar has a fittingly lengthy climax that portrays the pains of reconciliation between a sensitive woman and an inarticulate man. In the film’s final scenes, Sjöström risks a delicate emotional modulation that would daunt a director today. Using Hollywood continuity cutting with a casual assurance, he relies on subtly timed cuts and changes of shot scale to trace the couple’s wavering guilts and hopes. These last scenes have a human-scale gravity that balances the weighty paternal authority of the heavenly sequences. In Theatre to Cinema our colleagues Lea Jacobs and Ben Brewster have written a penetrating analysis of the performances of Sjöström as Ingmar and Harriet Bossa as Brita.

Unhappily, we know of no video version of this wonderful film. It should be a top priority for DVD companies specializing in silent cinema.

Another 1919 candidate for ambitious DVD purveyors is Louis Feuillade’s great serial Tih Minh. It has been overshadowed by Fantômas (1913-1914), Les Vampires (1915-1916), and Judex (1917), but it has a playful charm of its own. It is, in a way, the anti-Vampires. Instead of chronicling the triumphs of an all-powerful secret society, this six-hour saga gives us a few ill-assorted conspirators who inevitably fail at every scheme they try. The plot is no less far-fetched than that of the earlier serial, but the twists are more comic than thrilling. (Which is not to say that we’re denied some astonishing real-time stunt work performed by the actors, as above.) The film’s genial tone assures us that nothing bad will happen to the poor girl Tih Minh, but the villains will get enjoyably harsh punishment. In the course of the adventure three couples are formed, the routines of provincial life are filled in with leisurely detail, and the whole thing ends with a big wedding.

Unlike the Paris-bound serials, Tih Minh allowed Feuillade to apply his elegant staging skills to natural landscapes. By now he was filming in Nice, and the chases and fistfights are enhanced by gorgeous mountains, vistas of water, and hairpin roads. More than one connoisseur has confessed to me that this is their favorite Feuillade serial, and it’s hard to disagree. I always find that viewers are carried away by its zestful tale of good people who come to a good end.

DB’s runner-ups: Perhaps not as fine as the above, but definitely of bizarre interest, are two Robert Reinert films from 1919. The title of Opium pretty much sums up this fevered movie. It includes sinister Asians, drug-addled doctors, a lions’ den, and Conrad Veidt in a suicide-haunted performance that makes his Cesare role in Caligari look underplayed (see right). Later in the same year Reinert gave us an even more overwrought tale, Nerven. This is a movie about collapse–the collapse of a community, of a business, and of the tormented minds of buttoned-up citizens. Reinert renders melodrama in images of controlled frenzy unlike any others I know from the period. Had his films been as widely seen as the official Expressionist classics, I think he would be much admired today. I analyze these two movies in Poetics of Cinema, and say a bit about them in this entry. A DVD of Nerven is available from the Munich Film Archive.

DB’s runner-ups: Perhaps not as fine as the above, but definitely of bizarre interest, are two Robert Reinert films from 1919. The title of Opium pretty much sums up this fevered movie. It includes sinister Asians, drug-addled doctors, a lions’ den, and Conrad Veidt in a suicide-haunted performance that makes his Cesare role in Caligari look underplayed (see right). Later in the same year Reinert gave us an even more overwrought tale, Nerven. This is a movie about collapse–the collapse of a community, of a business, and of the tormented minds of buttoned-up citizens. Reinert renders melodrama in images of controlled frenzy unlike any others I know from the period. Had his films been as widely seen as the official Expressionist classics, I think he would be much admired today. I analyze these two movies in Poetics of Cinema, and say a bit about them in this entry. A DVD of Nerven is available from the Munich Film Archive.

KT’s runners-up: I suppose that there will be some tongue-clicking over the fact that Abel Gance’s J’accuse! is not present in our list. There’s no doubt it’s historically important and influential, but it’s also heavy-handed and doesn’t add the leavening of humor to its melodrama, as some of the above films do. But it does deserve a mention in an overview of 1919. (I’ve posted about what I see as Gance’s limitations here.)

Last year I put Marshall Neilan’s Mary Pickford vehicle, Stella Maris, in the top ten. I’d be tempted to do the same with his (and her) Daddy-Long-Legs, but this year there’s a lot more competition. But it’s a charming film, and the great cinematographer Charles Rosher provides another series of beautiful images using the new three-point lighting system. It was the first Pickford film into Germany after the war and considerably influenced Lubitsch and other German directors.

Similarly, in a year with fewer major films, Victor Fleming’s When the Clouds Roll By, a wacky, inventive tale of superstition and psychological manipulation starring Douglas Fairbanks, would make the main list. David illustrated some of that inventiveness in his epic entry on Fairbanks.

Within a few years, compiling our 90-year picks will become increasingly difficult. Experimental cinema will blossom, as will animation. The Soviet Montage and German Expressionist movements will get started, and French Impressionism, still a minor trend in the late teens, will expand. Filmmakers like Murnau, Lang, Vidor, and Borzage will gain a higher profile, and more films by veteran directors like Ford will survive. Maybe we’ll have to expand the annual list even further. . . .

A very happy New Year to all our readers! Assuming we make it through the security lines, we shall be celebrating New Year’s Eve on a plane bound for Paris, where David will be doing a lecture series over the first few weeks of January. Paris is the world capital of cinema, at least as far as the diversity of films on offer goes, so we shall no doubt find occasion to blog while there.

Sons of Ingmar.

Searching for surprises, and frites

DB here:

Studying film history ought to be continually surprising. Yes, you often find your hunches and assumptions confirmed (which often means it’s time to check them again). But sometimes you find stuff coming out of left field that you had never expected. It would be too pompous to call these items breakthroughs, but every historian knows the little burst of pleasure that comes from seeing something that makes you say: How odd. I didn’t expect that. You might even allow yourself a Wow! now and then.

I was saying wow a fair amount during my two weeks in Brussels this summer. I go regularly, and not just for the moules, frites, and stoemp. I go to the Royal Film Archive, where I study old films. This time I was continuing to pursue some research questions that drove me in 2007 and 2008. What staging and editing strategies are at work in films of the crucial years 1910-1917? How might we explain the continuities and changes we find? I’m a long way from answering these questions fully, but I found some fresh and intriguing instances. One surprise is worth half a dozen confirmations.

Divas on parade

This year I concentrated on European movies. One of the most prominent genres of Italian cinema was the diva film, the movie whose dominant attraction was a beautiful, often fiery, somewhat otherworldly female star.The mesmeric charms of the genre have been celebrated in Peter Delpeut’s anthology film Diva Dolorosa, but the films really need to be seen in their entirety. The most comprehensive book on the subject is Angela Dalle Vacche’s Diva: Defiance and Passion in Early Italian Cinema, while my Wisconsin colleague Lea Jacobs has published detailed analyses of diva performance in Theatre to Cinema and here on the web.

In the 1910s, American cinema was turning out fast-paced films, but the diva films I saw provided less complex plots and remarkably protracted acting. An emblematic instance is the climax of Rapsodia Satanica (1917), starring Lyda Borelli. Alba has sold her soul to Mephisto in order to recover her youthful beauty. She toys with two men’s affections, and one kills himself (mysteriously leaving a scar on her face). The plot more or less halts.

Alba retreats into her chateau and wanders the grounds. She glides forlornly through her garden, idles at the piano keys, and drapes herself along a bridge. She strews flowers on the floor and even dresses herself up as a priestess. Most strikingly, she floats into a cluster of mirrors and drapes herself in layers of veils, creating a gauzy shroud.

Run at 16 frames per second, this cadenza of apparitions consumes nearly a minute and a half. Such an exercise in atmospherics might be considered wasteful in an American film of the time, but it enhances the expression of Alba’s late-blooming spirituality—just before Satan comes to claim his pledge.

The same sort of languid choreography can involve other players. The diva’s performance, as Jacobs has shown, is often closer to dance than to orthodox acting, and she can weave arabesques around her more or less stationary suitors. At times the diva is a virtual acrobat. If you can call a contortion graceful, we can find it in the angular wrist maneuvers of Borelli in La Donna Nuda (1914).

The diva’s divagations are usually shot from a distance, and often there are big sets that are cleared of other actors to allow the actress maximum freedom and minimum distraction.At key moments, there might be a straight cut-in to the diva in medium-shot, but the visual narration keeps our attention fixed on a single arresting figure.

This tendency varies from the sort of ensemble staging that I’ve studied in more detail in On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light. The staging is based upon the diva’s decorative elaboration of her emotional states, rather than in the shifting configuration of several actors. This difference reflects a variation in pace as well: The diva’s subtle changes of expression and posture emerge gradually, but the behavior of actors in ensemble scenes tend to accelerate the flow of action and reaction.

The spotlighting of the diva was not a big surprise, perhaps, but at least a reminder that there are always several tendencies at work in film in any period. More unexpected was the opening sequence of Il Fuoco (1915), in which the heroine visits a lake for a sketching session. As she sits down, a painter arrives to do some painting of his own. There follows a sequence of fourteen shots taken from eleven camera setups, some quite close to the actors. The sequence displays the sort of orthodox continuity that we associate with American films of the same year (The Birth of a Nation, Regeneration, The Cheat).

Granted, European films of the 1910s display freer camera setups in exterior settings than in interior sets. Still, the director of Il Fuoco, Giovanni Pastrone, shows an intuitive mastery of angled shot reverse-shots and consistent eyelines. It makes me eager to see whether other European filmmakers were developing a tradition of continuity editing akin to the American one.

Asta Nielsen was, so to speak, a Danish-German diva. A beanpole with a long face and a slash of a mouth, she might seem an unpromising vessel for languid eroticism. Yet Die Asta became an icon of silent film after her sultry dance in Urban Gad’s Afgrunden (The Abyss, 1910) won her an international audience. In Germany she turned out a vast number of dramas and comedies, with her as undisputed main attraction. Lest we think that the term “star” is a modern one, the title card for S1 (1913) is already playing a coy game.

Again, with the spotlight on the heroine, the director’s decision can be simple. Evacuate the set and bring her closer to the camera, or if the set is cluttered, cut in to let Asta act.But she’s refreshingly unethereal, with changes of expression that are fleeting and unpredictable. At a lake with her lover, she flashes her legs at the camera and gives us a grin.

But a few frames later, her grimace becomes downright grotesque as she picks her way to shore. You can easily imagine her fear of losing her balance or stepping on a sharp stone.

Strong-willed and resourceful, Asta projects a wary intelligence. This, of course, doesn’t keep her from falling in love with worthless men.

Colorforms

Today’s archivists are determined to restore silent films to their original beauty, which includes the gorgeous colors achieved by tinting, toning, stencil coloring, and other techniques. Earlier this year Josh Yumibe came to our campus with a splendid collection of frames illustrating the range of possibilities. I saw several colored prints during my Brussels stay, including some original nitrate copies. Two from 1911 were films now acknowledged as “specialist classics.”

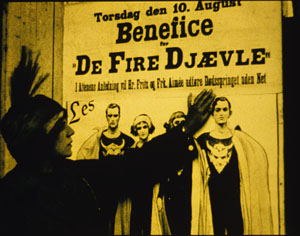

The Four Devils, directed by Robert Dinesen, is one in a cycle of circus films that was popular in Denmark at the period. A team of trapeze artists includes two men and two women; one couple has a steady romance, the other is fractured by the man’s attraction to a rich woman. Once Aimée is convinced of Fritz’s infidelity, she decides to kill him during a performance. The climactic “death leap” is rendered in about thirty shots, including one of an empty trapeze bar swinging. Under the big top, the compositions are full of detail and yet clearly laid out. And Dinesen reveals Aimée’s plan in one of the most ominous shots in silent Danish film.

Even more visually remarkable is Victorin Jasset’s Au pays de ténébres (In the Land of Shadows, 1911), a grim naturalistic drama set among coal miners. The film occasionally displays principles of depth staging that would be elaborated in some of the masterpieces of 1913. In one scene, the miners’ families gather in an anteroom. As they wait to identify the men killed in a cave-in, the bodies are barely discernible in the distance.

Au pays de ténébres illustrates a sort of structural usage of color. In scenes like the one above, the color is, in orthodox fashion, denoting a daylight interior. By contrast, the scenes in the mine are tinted blue, the standard hue for night and darkness.

But in the final scenes of the bodies assembled in the room of the dead, the color retains a blue cast, recalling the mine.

Thanks to the tinting, the living find themselves in the land of shadows.

Early auteurs

In the 1910s, we can find some distinct directorial approaches. One auteur is the German Franz Hofer, who liked to frame his actors in symmetrical architecture. Rectangular geometries are given a comic cast in Fraulein Piccolo (1915), a story about flirtatious officers and a schoolgirl forced to be both maid and bellboy. Here, two servants open doorways to watch a soldier starting to seduce the heroine.

I hadn’t expected to find surprises in Henri Pouctal’s Chantecoq, a two-part French feature from 1916. Yet this espionage drama was consistently engaging, and not just because the popular comedian Pougaud played the deceptively naïve hero. Pouctal unrolls his scenes in an unusual variety of setups, including an astonishing low-angle view of two spies grappling with Chantecoq on the floor of a train compartment. The image recalls Anthony Mann’s steep railway compositions in The Tall Target.

Alfred Machin was Belgium’s preeminent director of the 1910s. He never seems to have seen a windmill he didn’t want to film, then burn down or blow up. Machin enjoyed recording Belgian folk culture, particularly village dancers, as is evident in classic one-reelers like Le Moulin maudit (The Accursed Mill, 1909), and he had a fondness for jungle cats like Mimur the leopard.

Each of the Machin features I saw shed light on my research questions. Le Diamant noir (The Black Diamond) confirmed that the European tableau style was by 1913 achieving considerable intricacy. In this film, Luc, a rich man’s secretary, is accused of stealing the daughter’s bracelet. The scene of the police interrogation is a muted ballet of figures retreating, advancing, blocking, and revealing.

The servant in the far distance returns to visibility when he’s needed to show the cops to Luc’s room.

In Machin’s La Fille de Delft (The Girl from Delft, 1914), the tableau depth cooperates with some muted cutting. Kate is a famous dancer, visited by Jef, the young shepherd who has loved her since she was a girl. In her dressing room, while stage-door roués wait to take her out for dinner, she gets a message from him.

As she lowers the note, she makes her two playboy admirers more visible; we can see them opening the window.

They peer out, and we get an over-the-shoulder shot of Jef waiting outside.

When we cut back to the master shot, the men are mocking him and Kate is deciding whether or not to admit him. She goes to the window herself and looks outside. Again we get the over-the-shoulder framing, but in two beats: Kate looking, then Kate looking away.

The poignant framing lets us linger on her moment of decision. When she closes the window, we know that she has decided to abandon her childhood friend.

Simpler in its drama and staging is Machin’s official classic, Maudite soit la guerre (Cursed Be War, 1914). Adolphe, a young man from a country suspiciously similar to Germany comes to Belgium, or a place like Belgium, to learn aviation. Adolphe falls in love with his host’s daughter Lidia, but soon war breaks out between their countries and they must part. The rest of the film, which includes some spectacular aerial scenes (and, naturally, a burning windmill), pleads for peace and brotherhood. Released in May of 1914, Machin’s anti-war film now seems a futile warning.

The Archive has restored the original’s Pathécolor, creating images of great loveliness. Some scenes show stenciled color, which helps articulate the planes of shots arrayed in depth. An example surmounts this blog entry. At other moments, deep red tinting enhances the battle scenes, notably one of an exploding dirigible.

In all, this outstanding restoration of Maudite soit la guerre reminds us of what audiences actually saw—films of deeply felt emotion, often accentuated by spectacular action like that on display today, and employing color with both intensity and delicacy.

The restorer’s art

During my stay, I particularly enjoyed the time I spent with Noël Desmet, supervisor of restorations at the Belgian Film Archive. Noël invented the most robust method of recovering silent film color. Around the world, archivists have adopted the Desmet system.

Noël is scheduled to retire in April of next year. His research will be continued by his colleagues, and he will enjoy some well-earned time among his orchids. Film culture rests upon the shoulders of committed archivists like him. Noël Desmet and his peers are the guardians of treasures, the patient preservers of the secrets and surprises harbored by the twentieth century’s most powerful art form.

For more on tableau staging in Europe and the US, see the entries linked above, as well as my notes from this summer’s visit to the Danish Film Archive, some comments on acting styles, my discussion of Charles Barr’s idea of gradation of emphasis, and an entry on hands and faces around a table. The most thorough analyses of these and other staging principles are in On the History of Film Style, Figures Traced in Light, and certain chapters of Poetics of Cinema.

For more information on Machin and Mimur, see the bilingual book edited by Eric de Kuyper, Alfred Machin Cinéaste/ Film-maker (Brussels: Royal Film Archive, 1995).The Diva Dolorosa disc contains extracts from major films, but unfortunately they aren’t specifically identified, and the original cutting patterns aren’t always respected. The difficulty with such celebratory appropriations of silent films is that they are unreliable as historical evidence. Worse, in today’s commercial market, such compilations make it unlikely that other video producers will launch complete DVD versions of the films.

Tagebuch des Dr. Hart (Dr. Hart’s Diary, Paul Leni, 1916)

PS 18 August: Thanks to Armin Jäger for a name correction!

Passion, mortality, and everyday life

DB, flying back from Hong Kong:

Some of the most important films playing at the Hong Kong International Film Festival were already familiar to me—Still Walking, Il Divo, Gomorrah, Ashes of Time Redux—and some of my discoveries in Hong Kong have been covered in more recent entries.

What remains? Accentuating the positive, I’ll not talk about the disappointing items, some with strong reputations. I hope to blog about others in the months to come, when I’ve had a chance to study DVDs.

In the meantime, Kristin has already touched on Beaches of Agnès, a real charmer. Varda can be whimsical without turning fey; even dressed as a potato she doesn’t seem to be trying to grab attention. The film is a digressive, passionate memoir. The background on her early life is captivating, and her career as a photographer, shooting snaps of Pierre Vilar and Gerard Philippe, furnishes a stab of pathos. A montage of beautiful boys and girls: gone. Soon we get Varda’s straightforward acknowledgment of Demy’s death from AIDS. “All the dead lead me back to Jacques.”

Götz Spielmann’s Revanche, which I’d passed up at other fests, was a very solid psychological thriller. It’s built around two contrasting worlds, the sex trade of Vienna and the placid, churchgoing lifestyle of a village. From the first comes Alex, a man-of-all-work in a brothel. He falls in love with a Ukrainian hooker, and between bouts of cocaine he vows to help her escape the business. In the village live the policeman Robert and his wife Susanne, trying to have a child. Their life is secure and cozy, though Robert is wound a bit tight. The two worlds intersect during a bank robbery, and the rest of the drama plays out in the countryside, with Alex taking refuge on his grandfather’s farm. Alex and Robert become two variants of masculine anxiety, each defined by his way with a pistol, and their decisive confrontation is deftly postponed until the very last moments of the film.

I admire the way that Spielmann uses a spare long-take technique to increase suspense. Each scene usually consists of a single shot, taken from a judiciously chosen angle that unfolds the drama smoothly. There are barely 200 shots in nearly two hours, but the scenes don’t seem stiff because the framing and staging are quietly varied. Shot/ reverse-shot cutting is reserved for two turning points, one in the middle and one at the end. It’s nice to see a movie with no filler material, no passages of people driving in cars or going into the buildings, none of those time-wasting aerial shots of cities.

Some nice sound work too! No Country for Old Men has been rightly praised for its use of offscreen noise, but the Coens look rather showoffish compared to what Spielmann has accomplished here. A shot of Robert and Susanne on their patio is accompanied by the faintest rustle on the right channel: Alex, spying on domestic happiness like a character out of Highsmith or Ruth Rendell, has slipped away.

Similarly elegant in its staging and sound work is Claire Denis’ 35 Shots of Rum. The teasing exposition—a man watches commuter trains, a young woman rides one—dares us to imagine scenarios that could involve both. Our speculations turn out to be too wild, since their relationship is the most uncomplicated to be imagined. Based frankly on Ozu’s Late Spring, 35 Shots builds up its drama through daily routines, following its principals and their neighbors in everyday situations until, quite unexpectedly, a quiet crisis blossoms. Soon one scene ends: “We could be like this forever.” Next scene: everything has been overturned, and characters must change their lives. Visually the film is a marvel, with glowing scenes of semidarkness and discreetly out-of-focus details. As in her masterful Beau Travail, Denis supplies a powerful last shot, this time of an object we’ve nearly forgotten.

Two more thoughts: In my discussion of Revanche and 35 Shots, I’ve had to be coy in explaining basic plot situations and character relationships. That’s because these films work elliptically, holding back the sort of expository information that would be given in a concentrated dose early in most classical narratives. This narrational strategy poses no problem for an academic analysis, which tends to assume that the reader has seen the film. But it’s more difficult to handle when you’re writing a review. You don’t want to spoil the viewer’s surprise by explaining a core situation that the filmmaker has chosen to unfold gradually. If reviewers of Hollywood movies can’t give away the ending, the reviewer of an art film probably shouldn’t give away the beginning, or at least the information that it keeps in suspension for some time.

In other respects, though, there isn’t a clear dividing line between the “psychological” drama of international festival cinema and the more “externally driven” action of mainstream entertainment. Popular cinema relies on physical props like clues, souvenirs, messages, and gifts to help drive the plot. So, less obviously, do art films. The two photographs in Revanche deepen the character drama while triggering a major realization. The accidentally discovered letter (a convention of melodrama akin to the overheard conversation) in 35 Shots not only explains past actions but primes us to expect some conflict to come. As Aristotle knew, stories seem to need tokens to drive character revelation and plot reversals. A narrative universal?

Japanorama

Naked of Defenses.

Many of the movies I most enjoyed were Japanese. No surprise there. I know I’m prejudiced in favor, but objectively speaking the Japanese industry has long combined high output with great diversity and depth. I’m inclined to think that across film history, the three most consistently excellent filmmaking nations have been America, France, and Japan.

During Filmart, Yoshizaki Masahiro gave a swift but informative report on the current state of Japan’s “content industry.” It is the currently the world’s second-largest national film market , but it will sooner or later be replaced by China. Currently Japanese films are reclaiming the local audience, sometimes grabbing over half the annual box office. Unfortunately, that audience isn’t growing, and with a plunging birthrate, it’s unlikely to do so. Moreover, Japanese cinema has always been difficult to export, even in Asia. The great exception, of course, is anime, but even that is starting to slump. Anime is largely a television/ video format, yielding about twice in those platforms what it yields in theatrical income. But as advertising dollars have withered in the recession, anime has been cut back.

Despite all this, Japanese companies manage to release a staggering 400 or so films per year. (What counts as a release—theatrical? direct to video?—we leave for another day.) And the variety remains remarkable, judging by what I saw during my stay in Hong Kong. Put another way: Japan makes movies that are sweet, touching, funny, silly, and peculiar to the point of perversity. Not necessarily perversion, but that’s there too. And yes, schoolgirls’ panties are involved.

Not part of the festival, but playing in town was the diverting comedy Happy Flight. Like Airport and Airplane!, it weaves together various characters involved with a single flight. It concentrates almost completely on the professionals, from gate agents and mechanics to pilots and air hostesses. The one passenger depicted in detail rings true: After being allowed to bring an oversized bag into the cabin, he becomes a browbeating jerk.

Not part of the festival, but playing in town was the diverting comedy Happy Flight. Like Airport and Airplane!, it weaves together various characters involved with a single flight. It concentrates almost completely on the professionals, from gate agents and mechanics to pilots and air hostesses. The one passenger depicted in detail rings true: After being allowed to bring an oversized bag into the cabin, he becomes a browbeating jerk.

The film maintains its infectious pacing, adorning the action with minor-key gags like the airport’s “Somkin Room” for smokers. I also liked the moments of teamwork. When the stewardesses need a cake, they concoct one out of various packaged snacks. A young mechanic, constantly berated by his boss, thinks he’s dropped a wrench into the plane’s engine, and the whole ground crew searches the hangar for it. As with Airplane!, the final credits resolve several plotlines and add a few gags. If you like Waterboys and Swing Girls, also directed by Yaguchi Shinobu, you’d probably enjoy this.

Just as light, but a lot more intricate is Nakamura Yoshihiro’s Fish Story. Another network narrative, this one traces how Japan’s purported first punk song changed the course of history. The plot skips among periods from 1953 to 2012, when a comet is about to incinerate the earth. With many pop-culture in-jokes, from Beatles albums to The Karate Kid, this breezy, off-kilter item gets by on sheer adrenaline and on a cascade of puzzles. Why does the Fish Story song make no sense? Why does it contain a one-minute passage of silence? How are all these stories connected? And how can a song save the world? The narration cleverly withholds the basic relationships among the characters until a dizzying montage at the end wraps everything up.

Still further out there on the Nutsometer is Love Exposure, your basic four-hour inquiry into Christianity, cross-dressing, superheroics, and schoolgirl underwear. The story starts with a boy who promises his mother he’ll marry a woman like the Virgin Mary, but thanks to digital photography and an acrobatic approach to filming schoolgirls’ nether regions, he becomes known to his peers as King of the Perverts. Director Sion Sono satirizes cult religions, which seems to include Catholicism (“Your sin is that you can’t remember your own sin”), while devoting some attention to pornographic movies and “Candle in the Wind.” Rambling and digressive, but rapidly paced, Love Exposure proves that nobody beats the Japanese for cheerful dirty fun.

Still further out there on the Nutsometer is Love Exposure, your basic four-hour inquiry into Christianity, cross-dressing, superheroics, and schoolgirl underwear. The story starts with a boy who promises his mother he’ll marry a woman like the Virgin Mary, but thanks to digital photography and an acrobatic approach to filming schoolgirls’ nether regions, he becomes known to his peers as King of the Perverts. Director Sion Sono satirizes cult religions, which seems to include Catholicism (“Your sin is that you can’t remember your own sin”), while devoting some attention to pornographic movies and “Candle in the Wind.” Rambling and digressive, but rapidly paced, Love Exposure proves that nobody beats the Japanese for cheerful dirty fun.

A more straightforward Japanese entry in the Asian Digital competition was Ichii Masahide’s Naked of Defenses (the most awkwardly titled film I saw). Two women work at a factory making plastic parts. Ritsuko, a plain but dogged supervisor, is becoming alienated from her husband after her miscarriage. She envies the pregnant and insouciant new hire Chinatsu, whose marriage is overcoming its problems. Plain and sincere in its technique, Naked of Defenses ends with an astonishing sequence. By all the evidence onscreen, Ichii got a pregnant woman to play Chikatsu and filmed her giving birth. Balancing this powerful ending is the striking performance of Moriya Ayako as a woman sinking into depression but who may be saved by friendship and maternal love.

I took the occasion to catch Departures at a local theatre, since I had missed it at earlier festivals. And I’m happy to report that it’s distributed in the US by Regent Entertainment, run by Wisconsin graduate and old friend Steven Jarchow.

By now you’ve probably seen Departures too. At one level, it’s a good old-fashioned Shochiku movie, mixing tears and good-natured humor. Some decry it as middlebrow sentiment, but I found it a touching, fluent tale. For me, the central attraction is the repertory of gestures. Our two professionals handle the recently deceased tenderly, but that doesn’t preclude a crisp efficiency in flaring out a sleeve. I don’t think I’ll forget the way the undertaker grasps the dead person’s clasped hands and then executes a circular snap. Precise manipulation becomes a sign of respect.

And it isn’t all sunniness. Handling dead bodies is hazardous cultural territory in Japan. It is traditionally a task for the burakumin, a minority group long looked down upon. Although discrimination against the group has apparently diminished, the fact that a big star like Motoki Masahiro could play the role of a corpse-preparer could help dispel a lingering social stigma.

You could almost mount a Japanese film festival about mortality. Some musts would be Ozu’s Brothers and Sisters of the Toda Family and Tokyo Story, Kurosawa’s To Live, and Kore-eda’s After Life. Another required item would be Dying at a Hospital (1993), a rarely seen Ichikawa Jun film screened as part of a tribute to the recently deceased director. It consists of staged episodes showing a few cancer patients in their last months. An elderly husband and wife both have cancer, but must separate and be treated in different hospitals. A widow laments her rotten luck. A lively young man can’t accept the fact that he won’t see his children grow up. A homeless man is brought in, filthy and disoriented, and as he becomes aware of his plight, he still apologizes for accidentally turning up his pocket radio.

These and other cases are accompanied by voice-over narration from the doctor and nurse who treat them. Interspersed with these scenes are rapid documentary montages of people enjoying life—eating, drinking, viewing cherry blossoms, celebrating festivals, just walking down the street. The intimate facial reactions we’re denied in the hospital scenes are supplied in these vérité passages.

Dying at a Hospital is gentle and sympathetic, but its manner of shooting gives it special resonance. The hospital scenes are shot in planimetric fashion, with the camera rigidly facing a row of three beds, or a pair of beds, or only a single one. Everything is played in long shot, with no close-ups or camera movements to enlarge the faces.

Patients, visitors, and hospital staff move through these blocks of space. The lighting effects are particularly subtle, accentuated by very gradual fade-ins and fade-outs, as if dawn were breaking or night were coming on. As the film goes on, Ichikawa introduces variations in scale and new cutting patterns, creating what I called in Narration in the Fiction Film a sparse version of parametric narration. For instance, the spaces become more compact as terminal patients are shifted from a shared room to a private one, which permits nuanced effects of distant depth.

Ichikawa’s dry, physically detached treatment lets the poignancy of each situation emerge without any directorial boosting. The glimpses of daily life outside the hospital, zestful and shot on the fly, generate a powerful contrast: the preciousness of ordinary pleasures, and the dignity that must be accorded everyone about to leave them behind.

For a brief but sensitive appreciation of 35 Shots, see Ryland Walker Knight’s comments here–perhaps best read, for reasons mentioned above, after you’ve seen the film.

Departures.