Archive for the 'National cinemas: Germany' Category

Venice 2018: Big films on the big screen

Roma (2018)

Kristin here:

The Venice International Film Festival has a way of making the time fly–despite the occasional feeling when standing in line for a film that the doors will never open. It seems ages ago that we saw the early-morning press screening of First Man, and yet a mere three days have passed.

So far we’ve had the rare experience of each morning seeing another exciting, excellent, thoroughly satisfying film: First Man (which David has already written about), Alfonso Cuarón’s Roma, and the Coen Brothers’ The Ballad of Buster Scruggs. Can this last? Probably not, but the rest of the program offers rewarding films and so far seems to justify journalists’ claims that this year’s festival is boosting its already growing reputation.

A new (and laudable) tradition?

Last year we reported on the restored print of Lubitsch’s 1923 Rosita, which played on the evening before the official start of the festival, accompanied by an orchestra playing a restoration of the original score, edited and conducted by Gillian Anderson. This year the festival organizers followed up on that success by premiering the restored Der Golem (Carl Boese and Paul Wegener).

The large and enthusiastic crowd showed that, given the right presentation, this old film can attract those who think of the festival primarily as a place to see brand-new films before the rest of the world does. In fact, there’s also a healthy restoration thread running through the festival, though silent films tend not to figure in it.

Der Golem is noteworthy as one of a small number of relatively sympathetic Jewish-themed films that came out in the early to mid-1920s in Germany. (I recently wrote about this trend and the newly restored Der alte Gesetz.) It does not manage entirely to avoid stereotypes, but it should be pointed out that the Christian characters come across far worse.

Der Golem is an early entry in the German Expressionist film movement of the 1920s, having come out in 1920, the same year as Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari. Rather than using painted flats to create a stark, graphic look, as Caligari did, Boese and Wegener’s film features the droopy-clay look employed by Hans Poelzig, perhaps the finest of the Expressionist architects of the day. The result is that the clay buildings of the ghetto and the clay Golem seem at times to merge into each other.

The print looks much better than previous copies available. The Belgian Cinematek held an original negative, thought to be the one for German distribution, rather than the second negative shot for foreign distribution. Prints held in other archives supplied missing footage, as well as tinting and toning information and the graphics for some of the intertitles. The drop in clarity is apparent in the replaced passages, which, interestingly, include the sequence in which Rabbi Löw summons a demon to give him the magical name that will bring the Golem to life. Why this key moment was removed from the negative will probably remain a mystery.

The musical accompaniment was a modern composition by the six members of the Mesimér Ensemble. It fits the current fashion for highly dissonant scores, including the seemingly de rigueur vocal passages. It went well with the film.

I hope the festival organizers will continue this tradition of presenting restored silent films with musical accompaniment as a prelude to the festival. It makes for a relaxing transition into the more film-filled days to come.

Worth waiting for

After the critical and commercial success of Gravity (2013), which I wrote about here and here, there has been much curiosity about Alfonso Cuarón’s long-anticipated next film, Roma. Advance word had it that the film was to be shot in Mexico and in Spanish.

As I’ve already suggested, the film is splendid, and its black-and-white, widescreen images looked great on the huge Salla Darsena screen (from front row, center, of course). As with Zama last year, at the end David asked if we had just seen a masterpiece. Again neither of us had any doubt that we had.

The film may be based on Cuarón’s childhood memories, but it is hardly autobiographical. Instead the protagonist is Cleo, one of the indigenous maids who work for the upper-middle-class family whose dramatic arc parallels her own. Conventionally the maids Cleo and Adela would be present in the backgrounds of scenes or at best be supporting characters. Instead Cleo is our identification figure. Indeed, of the four children of the family, three of them boys, we never have a clue as to which one might represent the director.

The double plot revolves around two desertions. First the husband and father of the family departs on an ostensible trip to a conference in Canada, which is soon revealed as a cover for his leaving his wife for another woman. AT the same time, Cleo is dating a man who professes to love her but who deserts her the moment she reveals she is pregnant.

One might expect this sympathetic tale centered largely around Cleo to center on the family’s harsh treatment of her. Instead, the cruelty is muted and casual. The children clearly adore her, and she them, and the wife says at one point that she loves Cleo as well. Far from firing Cleo upon learning of the pregnancy, the wife comforts her, pays for medical treatment at the family’s hospital, and buys her supplies that she will need. Yet the unkindness is apparent as well. The wife curtly tells Cleo to clean up the dog turds in the courtyard–the accumulation of which provides a running gag. She also carelessly leaves Cleo, who cannot swim, to watch the unruly children at a beach with dangerous waves. This unreasonable demand precipitates one of the film’s most dramatic scenes, shot in an excrutiatingly suspenseful long take.

Cuarón directs with his usual utter control and flair. The film is set in 1971 (when the director would have been ten years old), and the period details are impeccable–especially the family’s Ford Galaxie, which provides a running gag whenf characters try to maneuver it into a narrow garage.

There are the expected long takes and camera movement. One fast tracking shot races along the middle of a busy street, keeping up with Cleo and Adela as they run joyously along block after block to enjoy their time off (top). In another scene, the camera wanders around the upper floor of a furniture store as Cleo shops for a crib, only to end with a pan to the windows and the revelation of the street below full of rioters.

In the ongoing controversy over Netflix’s reluctance to release its productions in theaters, it is particularly ironic that it should be the studio to produce Cuarón’s big-scale film. The promise is that it will be released “in select theaters.” If you live near one of those, don’t miss it.

Socialist Realism lives on

I had hopes of medium height that Mike Leigh’s Peterloo would live up to his previous historical films, Topsy-Turvy (1999) and Mr. Turner (2014). It turned out that Leigh had taken on a project with nearly insuperable obstacles.

While Topsy-Turvy had Gilbert and Sullivan, with its musical numbers and the innate drama of the pair’s occasionally testy relations, and Mr. Turner had painting and a single eccentric personality to focus on, Peterloo is about radical politics. The Peterloo massacre of 1819, which perforce occurs only in the climax of the two-and-a-half-hour film, is a major incident in the history of British radicalism and reform, and it is relatively well-known to the citizens of Great Britain. Elsewhere audiences are likely to be unaware of it.

As a result, Leigh must present a great deal of exposition about the issues and the lead-up to the peaceful protest march at St. Peter’s Field in the Manchester area. The exposition takes the form of a long series of speeches and conversations about those issues. The speeches are largely taken from the historical record, and they impart a great deal of authentic historical information, but they frequently overwhelm the drama.

Many of the speakers are historical characters, about whom we learn relatively little. Leigh humanizes the situation by focusing at intervals on a single poverty-stricken family whose adult men work at the local weaving mills and face dwindling wages from the mill-owners.The opening is clearly intended both to provide a bit of violent action as a hint of things to come, much later, and to introduce us to a young bugler who belongs that poverty-stricken family. We follow his trek home, his arrival there, and, briefly, his fruitless search for work.

If we expect him to become an active protagonist, however, we are disappointed, for he recurs only occasionally and passively thereafter. Instead we move around the various occasions on which speeches are given to rouse the downtrodden population to action. It must, after all, be plausible that roughly 70,000 people from the area would assemble in Manchester for a peaceable demonstration for the vote and representation in Parliament.

The local politicians who attempt to thwart the protest and possible resulting violence are portrayed as old, ugly, and nearly hysterical in their mingled fear of and contempt for the working classes. Their fears aren’t entirely unreasonable, given that the Luddite movement of 1812 led workers to destroy the labor-saving automatic looms and occasionally the factories that held them. Violence had killed people on both sides of the struggle. Leigh perhaps hints at the “machine-breakers” in his shots of the vast mill interior (above) and some of the dialogue, but only someone familiar with British history of the era would link the Peterlook protestors to the Luddites.

The result somewhat resembles the Soviet Socialist Realist films of the 1930s and 1940s, with their noble peasants and caricatured bourgeoisie and government officials. Not that there’s anything wrong with that, exactly, but the Soviet films seldom tried for actual realism, and Leigh cannot entirely give up his passion for naturalism. The result is an uneasy mixture in Peterloo‘s tone.

Despite its faults, the film is impressive. Produced, again ironically, by Amazon, the film has what must have been Leigh’s biggest budget to date. Authentic costumes have been created for actors and extras enough to at least suggest the tens of thousands present that day (below). The mill and the surrounding slum are convincing, and Leigh has managed to find some unspoiled landscapes to provide a relief from the grimness of working-class life in the era. Amazon will release it in the US on November 9, as part of the film’s slightly premature celebration of the 200th anniversary of the event.

Check out our Instagram page for ongoing photos from the festival.

As ever, thanks to Paolo Baratta, Alberto Barbera, Peter Cowie, Michela Lazzarin, and all their colleagues for their warm welcome of us to this year’s Biennale.

October 31, 2018: Netflix has announced that it will give Roma a theatrical release, starting on November 21 in New York and Los Angeles; it will be in more theaters starting December 7 and open wider on December 14. It will been seen theatrically in 20 countries. There will be several theaters showing it in 70mm.

Peterloo (2018)

Catching up with the past: Recent DVD and Blu-ray releases

Behind the Door (1919).

Kristin here:

David and I have moved house recently, which has caused a long lag in my getting around to doing a DVD/Blu-ray roundup of recent releases. Some are not so recent anymore, but I shall call attention to them nonetheless.

Behind the Door (1919)

Our friends at Flicker Alley have been busy, as usual.

Way back in February of last year, they released Behind the Door, a notoriously grim and brutal drama of World War I that long survived only in incomplete form. Using tinting rolls from the Library of Congress, some scenes from star Hobart Bosworth’s collection, and a re-edited Russian distribution print, as well as a copy of the continuity script, the restoration by the San Francisco Silent Film Festival, the Library of Congress, and Gosfilmofond approximates the original American release version fairly closely. (Two brief missing sections are filled in by photos and the texts of the original titles.) The tinting and toning, based on the Library of Congress material, is authentic and effective (see top), as is the new score by Stephen Horne.

The Russian version is included in the two-disc set, so we have one of those rare cases where it is possible to compare the foreign and domestic versions–to a degree. Most of the shots, of course, were made with a second camera, and there are inevitably differences of framings and even takes between those versions. Given that the new restoration depends heavily on the Russian print, the comparison must be made primarily on the basis of the differences in the order of the scenes and the other narrative changes made by the Russian editors.

Behind the Door tied for Best Single Release in Il Cinema Ritrovato’s DVD Awards, announced just last month. Congratulations to Flicker Alley and to other organizations we have ties to, which also won awards. The Criterion Collection tied for Best Box Set for its 100 Years of Olympic Films: 1912-2012. This massive set (32 discs on Blu-ray, 43 on DVD) contains 53 films, including those by Leni Riefenstahl, Kon Ichikawa, Claude Lelouch, Carlos Saura, and Miloš Forman. Belgium’s Cinematek won Best Discovery of a Forgotten Film for its Marquis de Wavrin (1924-1937), actually a series of films shot in South America by this major anthropologist and filmmaker. German Concentration Camps Factual Survey (from the BFI and the Imperial War Museum), which David commented on last year, won Best Special Features.

Das alte Gesetz (1923)

I have a particular interest in German silent cinema of the post-World War I era, so I was happy to see Flicker Alley’s release of Ewald André Dupont’s Das alte Gesetz (“The Ancient Law”). Most people know Dupont only from his most famous and successful film, Variety (1925), known for its spectacular camera movements taken from trapezes.

Dupont had a long career, however, starting as a scriptwriter in the 1910s and becoming a director as well in 1918. Das alte Gesetz is mainly known as one of a small group of Jewish-themed films made in Germany in the period 1919-1924. More familiar to most would be Der Golem:Wie er in der Welt kam, co-directed by Paul Wegener and Carl Boese (1920) and to some, Die Gezeichneten, Carl Dreyer’s first German film (aka Love One Another, 1922). A helpful essay in the accompanying booklet by Cynthia Walk gives the political context of die Judenfrage (“the Jewish question) as it was being debated in Europe at the time.

Set in the 1860s, the film concerns Barush, the son of a rabbi in a shtetl in western Russia. He suddenly and somewhat implausibly conceives a desire to leave home and become a famous actor. Naturally his father disowns him. Joining a small traveling troupe, Barush ends up in Vienna, where an archduchess, played by Henny Porten, is impressed by his performance as Romeo and attracted to him as well. She arranges for him to join her court-theatre troupe, where he becomes a star as a classical actor.

The scenes in the shtetl (above) are done with considerable attention to authenticity and without the sort of ethnic humor that one might expect. Although Barush encounters prejudice in Europe, he does not evenually learn a lesson about assimilation and go back to his home with his tail between his legs. Far from it; his father is induced to read Shakespeare and suddenly realizes that there are indeed more things in heaven and earth than he had dreamed of in his philosophy. A happy reunion results, and Barush continues his career.

Das alte Gesetz was clearly a big-budget period piece, with several large sets. Moreover, the influence of classical Hollywood films, which began to be shown in Germany in 1921, is quite apparent. Dupont has mastered three-point lighting and analytical editing, including shot/reverse shot, as this scene between Barush and his father demonstrates.

Barush is played by Ernst Deutsch, a major actor of the day, including in Expressionist films. He’s the rabbi’s son in Der Golem as well, and he plays the bank-cashier protagonist in Karl-Heinz Martin’s From Morn to Midnight.

MOD

Flicker Alley has also developed a healthy list of manufactured-on-demand titles. Many of these are out-of-print films from the Blackhawk Collection. The 51 titles currently on the list include many silent classics, some of them difficult to see on disc otherwise, such as Lubitsch’s The Marriage Circle and Abram Room’s Bed and Sofa.

The new offerings lately have branched out somewhat to include more recent films. On September 3 of last year, the company released Alex Barrett’s London Symphony (2017) for its home-video debut. In the press release for the disc, the director describes it as “a love letter to a city, but it is also a film about life in the modern era.” As the title indicates, Barrett places his film in the city symphony genre, and its release was timed to coincide with the 90th anniversary of the premiere of Berlin: Symphony of a City. City symphonies tend to be associated with the 1920s, when the genre originated and its most famous exemplars, Berlin and Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera, were made. The genre has never disappeared, but Barrett has written that he chose “to make the film in a style associated with the filmmakers of the 1920s.”

For me, it captures well the style of the 1920s, and particularly Berlin. Shot in black-and-white, London Symphony falls into four movements, following a day in the life of the city–with, as in Berlin, pauses for lunch and dinner particularly dwelt upon. The opening section concentrates on buildings, and there are the inevitable juxtapositions of old and new (see bottom). Multiple cinematographers filmed the footage, but their work blends into a unified visual whole with many striking compositions.

Ruttmann injects occasional implicit political commentary, as when he juxtaposes shots of beggars in the streets with the well-fed Berliners in restaurants. Barratt concentrates on the beautiful and peaceful side of London–historic buildings, quiet parks, pleasant markets, and river scenes. The rather grubby and crowded atmosphere of, say, the West End of London is nowhere to be seen, which befits “a love letter.”

In January The Indomitable Teddy Roosevelt joined the MOD catalog. This is a reissue of a 1983 television documentary that mixes documentary footage (Roosevelt was the first president to be filmed) and staged scenes.

Edition Filmmuseum

This series continues its steady release of experimental filmmaker James Benning’s works with a sixth two-disc set (DVD only) that goes back to his earliest features, films that solidified his international reputation. The new two-disc set contains two films from the late 1970s, 11 x 14 (1977) and One Way Boogie Woogie (1978). Jim followed up the latter, a series of sixty shots of Milwaukee cityscapes, with 27 Years Later (2005), which presents the same series of locations, and One Way Boogie Woogie 2012, which further documents the changes in the filmmaker’s hometown. All three films are included in this set.

11 x 14 flirts with presenting a narrative without ever really concentrating on it. We see some of the same people at intervals, but no causal events link them, and their actions create situations rather than developing stories. Instead, the film’s shots, some quite lengthy, others brief, explore the urban and rural landscapes of Chicago and Milwaukee, as well as rural roads and fields in the surrounding area. (A familiar highway sign pointing the way to Madison is glimpsed at one point.)

For the most part the urban images concentrate on run-down areas, with motifs of travel (billboards, airplanes) and drinking (bars and more billboards) hinting at contrasting modes of escape. The shot above captures both motifs at once.

Given that Jim’s films seldom play outside festivals and museum venues, the Filmmuseum series is vital–though many of the images in these films are long or even extreme long-shots and benefit from being seen on a big screen. The last time we had a chance to do so was when RR (2007) was shown at the 2008 Vancouver International Film Festival. The Austrian Filmmuseum also published a book on Jim’s work, which David discusses here.

London Symphony (2017)

More Bologna bounty

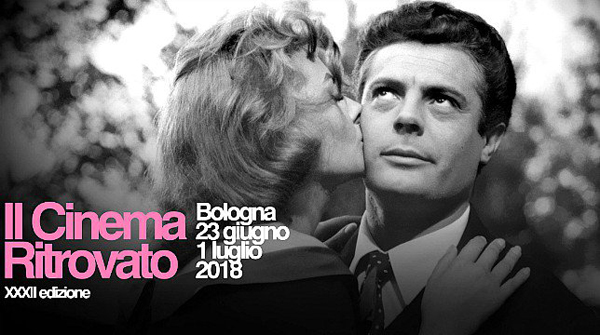

I think this has become my favorite Ritrovato key image.

DB here:

Cinema Ritrovato rolls on, leaving your obedient servant little time to blog. Herewith some quick impressions on a thin slice of all that’s going on. For a full schedule of this incredible event, go here.

IB or not IB

“Not all IB Tech prints are created equal,” explained Academy Film Archivist (and UW–Madison grad) Mike Pogorzelski. In his last of his annual Technicolor Reference Print shows, he pointed out that Technicolor sent its best-balanced prints to big-city venues and circulated them widely. As a result, they got worn out. The prints most likely to survive were less-than-perfect ones sent to the hinterlands or just kept as backups. Hence the need to preserve the Reference Prints selected by the filmmakers as defining the Technicolor timbre of each film.

With clips ranging from The Godfather and Let It Be to Sssss and Billy Jack, the sample gave a good sense of what Tech looked like a few years before the imbibition (IB) process was abandoned in 1974. Mike and Emily Carman introduced the extracts with informative commentary. I had always thought that Gordon Willis’s cinematography on the Godfather films and The Parallax View increased graininess, and this show seemed to confirm that sense.

Those naughty pre-Code pictures, again

The John Stahl and William Fox retrospectives brought some spicy material. Women of All Nations (1931), Raoul Walsh’s episodic sequel to What Price Glory?, had Quirt and Flagg on the verge of all-out cussing in nearly every scene. A monkey wriggling inside El Brendel’s trousers created moments of good dirty fun. Bachelor’s Affairs (tee-hee, 1932) had Adolph Menjou peering down a golddigger’s front and praising her virtues: “What a charming combination.” She asks if it’s showing. Likewise this repartee: “Were you out last night?” “Not completely.”

William Dieterle’s Germanic Six Hours to Live (1932) begins as a political thriller and devolves into a Twilight Zone fantasy. A representative of a small country passionately protests worldwide tariff legislation. To keep his vote from vetoing the action, spies target him for elimination. Soon enough, he’s throttled to death. But an enterprising scientist takes the opportunity to try out his resuscitation ray, which gives the hero a few more hours to make his mark.

John Seitz photographed the whole farrago in glowing imagery shot through with shafts of blackness, alternately soft-focus and crisply edged. Here’s the magic machine.

The film’s look is an example, I suppose, of what Andrew Sarris once called “Foxphorescence”–the signature of a studio that, from Murnau and Borzage to Ford and 1940s noirs, played host to dazzling pictorial effects.

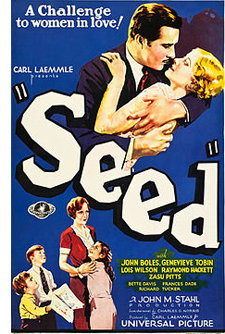

Not completely naughty, but certainly a film about sexual jealousy, was Seed (1931), one of the most anticipated films of the Stahl cycle. It lived up to its reputation as a masterly orchestration of sympathies. At the center is a love triangle based on two women’s roles: the mother and the businesswoman.

Aspiring author Bart Carter has given up his novel, and he lives–he thinks–happily with his wife Peggy and five rambunctious kids. When his old flame Mildred returns to the publishing firm Bart works for, she encourages him to keep writing and to stray from the household Peggy has made for him.

Aspiring author Bart Carter has given up his novel, and he lives–he thinks–happily with his wife Peggy and five rambunctious kids. When his old flame Mildred returns to the publishing firm Bart works for, she encourages him to keep writing and to stray from the household Peggy has made for him.

As often happens in Hollywood, the plot works only if the man is a jerk, and the action will set up things to make the woman take the blame. Mildred may not have schemed to pull Bart away from the start, but the shift in our sympathy to Peggy is pretty decisive. The film’s patient pace and stringently objective presentation lets contrasting feelings get developed gradually. The kids, particularly the whining runt of the litter, are annoying and troublesome. Mildred is no obvious predator, Peggy is trying valiantly to accommodate Bart’s ambition, and he’s enjoying his vacation from fatherhood while still struggling, albeit weakly, to stay loyal to his family.

Stahl was one of the major long-take directors of 1930s Hollywood, and Seed is exemplary in this respect. (The average shot lasts about twenty seconds.) His back-to-basics two shots, facing off characters in profile, become the default setting; there are scarcely any reverse angles or eyeline matches. This apparently simple creative choice, anticipating Preminger’s method of the 1940s and 1950s, puts all characters on an equal footing. The framings force us to concentrate on their conversation, avoiding the customary cuts that punch up particular lines or reactions. A similar steady observation is at work in Stahl’s fine Imitation of Life (1934) and Magnificent Obsession (1936).

1918 and all that

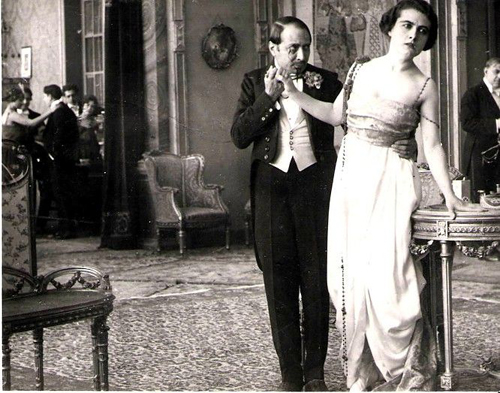

L’avarizia (1918). Production still.

Regular readers of this blog know that one area of my research is the stylistics of 1910s cinema in various countries. (Check the category tableau staging for a sample.) Naturally I dropped obsessively in on the 100-years-ago strands at this year’s Bologna. While there are more films to come, I found plenty to enjoy and think about in the first few days.

There was, for instance, Der Fall Rosentopf, a fragment of a farcical Lubitsch feature. Ernst plays his Sally character, now a detective investigating a flower-pot mystery. Lively enough, the surviving nineteen minutes from early scenes didn’t give me much sense of the whole.

Alongside it were two other comedies. Gräfin Küchenfee featured Henny Porten in a dual role, both countess and kitchenmaid. When the countess goes off to have fun, the maid assumes her identity. Eventually, the two women switch roles when the countess tries to evade police charges by pretending to be the maid. No less predictable in its comic situation was Puppchen, in which a young woman working in a fashion salon breaks a lifelike mannequin and must take its place. It may have been a model for Lubitsch’s Die Puppe (1919).

Stylistically, all these films were fairly staid, with little intricate staging, and they lacked analytical editing apart from axial cuts in and out. Their reliance on longish takes probably reflected the fact that US films, with their bold continuity editing, weren’t available in Germany until somewhat later.

One American film also rejected the emerging Hollywood style, in the name of naivete and fancy. That was Prunella by Maurice Tourneur. It doesn’t survive complete, and it’s been known for many years as a failed venture into artiness. The flat sets resemble children’s book illustrations, and the performance style is wilfully arch. I’ve never found Prunella very interesting, but it does offer further evidence that the 1910s harbored some eccentric and ambitious experiments.

Gustavo Serena’s L’Avarizia impressed me more. It too relies on frontal acting and axial cutting, but as a vehicle for the great diva Francesca Bertini it seemed to me completely engrossing.

As part of a series illustrating the Seven Deadly Sins, it offers a starkly symmetrical plot. Maria and Luigi love each other, but each is dominated by an old miser. Her aunt and his father each amass a fortune in secret while manipulating the young people. Through a series of conspiracies and misunderstandings, the lovers are flung apart. Maria, friendless and illiterate, sinks down, down into the bottom of society.

Each step of the way is given powerful expression by Bertini’s face, gestures, and bearing. She grabs her hair to yank her head back; she blows cigarette smoke in Luigi’s face to show her contempt for his abandonment of her. At one high point, when Luigi falsely accuses her of infidelity, she wrestles with him on a tabletop, giving no quarter. In a tavern fight she pulls a knife before falling to the floor, writhing feverishly in what appears to be her last moments on earth. This is silent opera, with the soaring melody carried by the body.

Up against the fourth wall

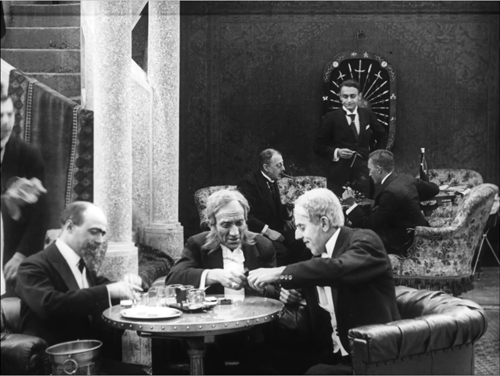

A meeting of the Antifeminist Club (The Oriental Language Teacher).

I wasn’t surprised to find a diva film full of sensuous appeals, but the big revelation of the 1918 cycle so far was the Czech comedy The Oriental Language Teacher (Učitel Orientálních Jazykû). It showed what you could do with a small cast, a few sets, and a cut-and-dried situation.

Sylva secretly falls in love with Algeri, who’s tutoring her in Turkish. After her father is being considered for a diplomatic post in Turkey, he decides to learn the language. He arrives during one of Sylva’s lessons, so she quickly disguises herself as an odalisque. Needless to say, Father is smitten with this exotic beauty. Add in his membership in the Antifeminist Club, led by a comic geezer who enjoys snapping clandestine photos of passing women, and insert deceptions involving a pianola roll, and you have some substantial complications.

Most striking from a pictorial standpoint were the very deep sets–modeled, stylistic historian Radomir Kokes tells me, on the Danish cinema of the period. The co-directors Olga Rautenkransovå and Jan S. Kolár present Sylva’s parlor in an unusual way. Most films of the period put foreground desks and tables at a diagonal bias. But here the father’s desk is thrust very close to us, perpendicular to the camera, and it runs the entire length of the frame.

Moreover, the father is centered at his desk, when the more normal placement would set him to left or right and clear a space in the other half of the frame for other characters. The depth, that is, is typically horizontal. Here, though, it’s also vertical. A character must descend the stair directly above the other, in a maniacally centered composition that’s mildly beguiling in itself.

The set depicting Algeri’s studio is a little more typical of the period, since his desk is placed off to one side, but every shot of this setup makes the foreground area curiously out of focus.

Given that the control of focus is precise in the parlor shots, the slightly fuzzy foreground of the studio set remains anomalous–an error, or a decision to differentiate the two spaces more sharply. In any case, here’s another example of how 1910s movies, from all corners of the world, can set you thinking about the possibilities of pictorial design.

More to come in the next entry, with a special focus on trial films.

Special thanks to Radomir Kokes for help with this entry. More generally, thanks to the Bologna leaders and staff for a tightly-run and ever-exciting event, along with the archivists who made these films available. In particular we owe a lot to Marianne Lewinsky, who curates the Cento Anni Fa series, and to Dave Kehr who, grinning, shares what he called on the first day MoMA’s “mildly obscure” treats. And Imogen Sara Smith gave an exceptionally lucid introduction to Seed.

For more on diva acting, see Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs, Theatre to Cinema, a book available here, and this entry by Lea on Bertini. Kristin wrote about Prunella and other mildly experimental Hollywood films in Jan-Christopher Horak’s Lovers of Cinema collection.

For more on-the-spot pictures, check our new Instagram page.

John Bailey, President of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, and Michael Pogorzelski.

Mmm, M good

DB here, boasting about Kristin:

Our series on the Criterion Channel on FilmStruck continues with this month’s entry, Kristin on M as an exceptionally rich sound film. She talks about how Lang adapted silent-film techniques to the demands of sound while also using sound to achieve effects that couldn’t be achieved purely through images.

Watching her discussion and the clips, I was reminded of what a precise director Lang was–a unique mixture of stylistic flamboyance and swift economy. You see that mix in silent masterpieces like the Mabuse films, Metropolis, The Niebelungen, and Spione. In various entries (here and here and here) I’ve dwelt on his poised, meticulous compositions that use the entire frame area. Sound gave him a new set of resources for dynamic expression. Rather than becoming more conventional, Lang’s American films seem to subtly absorb the discoveries of M. Examples are the tapping of the “blind” man’s cane in Ministry of Fear and the ominously croaking frogs in You Only Live Once. And the propulsive sound cuts in his last film, The Thousand Eyes of Dr. Mabuse, show that he never forgot that sound could be edited as freely as images.

You can sample a clip from the episode at On the Channel at Criterion’s site. A complete list of the Observations on Film Art series (eleven already!) is here. Go here for blog entries offering background on those installments.

Thanks as ever to Peter Becker, Kim Hendrickson, Grant Delin, and all their teammates at Criterion.