Archive for the 'National cinemas: Germany' Category

The ten best films of … 1925

The Big Parade (1925).

Kristin here:

As all about us in the blogosphere are listing their top ten films for 2015, we do the same for ninety years ago. Our eighth edition of this surprisingly popular series reaches 1925, when some of the major classics of world cinema appeared. Soviet Montage cinema got its real start with not one but two releases by one of the greatest of all directors, Sergei Eisenstein. Ernst Lubitsch made what is arguably his finest silent film. Charles Chaplin created his most beloved feature. Scandinavian cinema was in decline, having lost its most important directors to Hollywood, but Carl Dreyer made one of his most powerful silents.

For previous entries, see here: 1917, 1918, 1919, 1920, 1921, 1922, 1923, and 1924.

The lingering traces of Expressionism vs the New Objectivity

The Joyless Street (1925).

Last year I suggested that German Expressionism was winding down in 1924. It continued to do so in 1925. Indeed, no Expressionist films as such came out that year. What I would consider to be the last films in the movement, Murnau’s Faust and Lang’s Metropolis, both went over budget and over schedule, with Faust appearing in 1926 and Metropolis at the beginning of 1927.

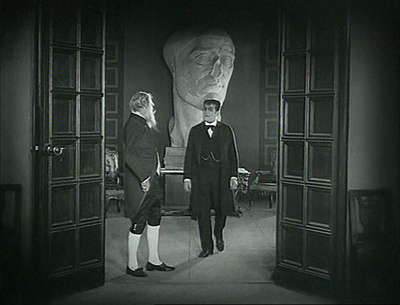

Murnau made a more modest film that premiered in Vienna in late 1925, Tartuffe, a loose adaptation of the Molière play. The script adds a frame story in which an old man’s housekeeper plots to swindle and murder him. The man’s grandson disguises himself as a traveling film exhibitor and shows the pair a simplified version of the play, emphasizing the parallels between the hypocritical Tartuffe and the scheming housekeeper.

The film has some touches of Expressionism but cannot really be considered a full-fledged member of that movement. The lingering Expressionism is not surprising, considering that some of the talent involved had worked on Robert Wiene’s Das Cabinet des Dr.Caligari: screenwriter Carl Mayer, designers Walter Röhrig and Robert Herlth, and actors Werner Krauss and Lil Dagover.

The visuals include characteristically Expressionist moments when the actors and settings are juxtaposed to create strongly pictorial compositions. These might be comic, as when the pompous Tartuffe strides past a squat lamp that seems to mock him, or beautifully abstract, as when Orgon is seen in a high angle against a stairway that swirls around him:

A restored version is available in the USA from Kino and in the UK in Eureka!‘s Masters of Cinema series. (DVD Beaver compares the two versions.) The restoration was prepared from the only surviving print, the American release version; it runs about one hour.

The other German film on this year’s list, G. W. Pabst’s The Joyless Street, contrasts considerably with Tartuffe. It was arguably the first major film of the Neue Sachlichkeit or New Objectivity trends in German cinema. I have already dealt with it in a DVD review entry shortly after its 2012 release. The restoration incorporated a good deal more footage than had been seen in previous modern prints, but it remains incomplete.

Once more the comic greats

The Gold Rush (1925).

For several years now these year-end lists have mentioned Charles Chaplin, Buster Keaton, and Harold Lloyd, in various combinations. Early on it would was Chaplin alone (Easy Street and The Immigrant for 1917) or Lloyd and Keaton alone (High and Dizzy and Neighbors for 1920). In a way most of these films were placeholders, signalling that these three were working up to the silent features that were among the most glorious products of the Hollywood studios in the 1920s. In our 1923 list, each found a place with a masterpiece: Chaplin’s A Woman of Paris, Keaton’s Our Hospitality, and Lloyd’s Safety Last.

This year we may surprise some by giving Lloyd a miss. For years The Freshman was thought of as his main claim to fame, perhaps alongside Safety Last. I think this was largely because The Freshman was the one of the few Lloyd films that was relatively easy to see. (Perhaps also because Preston Sturges dubbed it an official classic by making a sequel to it (The Sin of Harold Diddlebock, aka Mad Wednesday, 1947.) Now that we have the full set of Lloyd’s silent features available, it emerges as a rather tame entry compared to Safety Last, Girl Shy, or our already-determined entries for 1926, For Heaven’s Sake, and 1927, The Kid Brother. Let’s just call The Freshman a runner up.

Keaton’s Seven Chances takes one of the most familiar of melodramatic premises and literally runs with it. James Shannon discovers from his lawyer than he stands to inherit a great deal of money if he is married by 7 pm on his 27th birthday–which happens to be the day when he receives this news. A misunderstanding with the woman he loves leads to a split, and in order to save himself and his partner from bankruptcy, Shannon determines to marry any woman who will volunteer in time. Hundreds turn up.

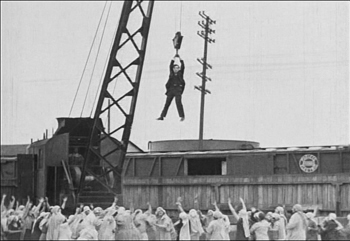

The result is another of the extended, intricate chase sequences that tend to grace Lloyd’s and Keaton’s features, and to a lesser extent Chaplin’s. In fact Seven Chances has a double chase. The first and longer part involves a huge crowd of women gradually assembling behind Shannon as he unwittingly walks along the street. This accelerates and keeps building, exploiting various situations and locales, as when the chase passes through a rail yard and Shannon escapes by dangling from a rolling crane above the women’s heads. Eventually the action moves into the countryside, where the brides temporarily disappear, taking a short cut to cut Shannon off, and he ends up in the middle of a gradually growing avalanche.

Seven Chances is available on Blu-ray and DVD from Kino.

Of all the films on this year’s list, Chaplin’s The Gold Rush is probably the most widely familiar. The Little Tramp character, here known only as a “Lone Prospector,” blends hilarity with pathos in a fashion that is actually typical of relatively few of the director/performer’s films overall. It is, however, how many people think of him.

The Gold Rush looks rather old-fashioned compared with Seven Chances. Although the opening extreme long shots of an endless line of prospectors struggling up over a mountain pass are impressive, much of the action takes place in studio sets, sometimes standing in for alpine locations. Both the cabins, Black Larsen’s and Hank Curtis’, are like little proscenium stages, with the action captured from the front. Yet the film depends on its brilliant succession of gags and on the Prospector’s status as the underdog who is also the resilient and eternal optimist.

The best bits of humor arise from Chaplin’s ability to create funny but lyrical moments by transforming objects metaphorically. Given the plot, some of the best-known gags arise from meals. One is the dance of the rolls, part of a fantasy sequence in which the Prospector dreams of entertaining a group of beautiful women at dinner (above), when in fact the women stand him up. Trapped by a storm in a remote cabin, the Prospector and his partner cook one of his shoes. He serves it on a platter and carefully “carves it, with the leather becoming the meat, the nails bones, and the laces spaghetti.

Many home-video versions of The Gold Rush have been released, but the definitive restoration of the 1925 version is available from the Criterion Collection.

The Golden Age in full swing

Lazybones (1925).

When people speak of the “Golden Age” of the Hollywood studio system, they usually seem to mean the 1930s and 1940s (and the lingering effects of the system in the 1950s). A look at Hollywood films of the 1920s shows that it was already functioning at full steam. Three features of 1925 display the utter mastery of continuity storytelling and style and a sophistication that matches films of subsequent decades.

Lady Windermere’s Fan may be the best silent made by Ernst Lubitsch, who has appeared on these lists before. It arguably ranks alongside Trouble in Paradise and The Shop around the Corner as one of the best films of his entire career. It’s a loose adaptation of the Oscar Wilde play, but it’s pure Lubitsch throughout.

Anyone who thinks that the classical Hollywood system was merely a set of conventions that allowed films to be cranked out with minimal originality could learn a lot from Lady Windermere’s Fan. Its completely correct use of continuity editing, three-point lighting, and the like does not preclude imaginative touches and methods of handling whole scenes. There’s the sequence when Lord Windermere visits the mysteriously shady lady Mrs. Erlynne in her drawing-room. The camera is planted in the center of the action, with frequents cuts as the two characters move in and out of the frame and even cross behind the camera. There’s not a hint of a mismatched glance or entrance across this complex and unusual series of shots. There’s the racetrack scene, as everyone present watches and gossips about Mrs Erlynne in a virtuoso string of point-of-view shots.

The racetrack scene ends with a wealthy bachelor following Mrs Erlynne out of the track. The camera moves left to follow her, keeping her in the same spot in the frame. As the man gradually catches up, Lubitsch uses a moving matte to hint at their meeting without showing it or cutting in toward the action.

A good-quality transfer of Lady Windermere’s Fan is only available on DVD as part of the More Treasures from American Film Archives 1894-1931. (Beware the copy offered by Synergy, which according to comments on Amazon.com is from a poor-quality, incomplete print.)

The one title on this list whose inclusion might surprise readers is Frank Borzage’s Lazybones. I remember being bowled over by this film during the 1992 Le Gionate del Cinema Muto festival in Pordenone, which included a Borzage retrospective. I found the more famous Humoresque (1920) a disappointment, but Lazybones was a revelation. This is another case of a film that was simply unknown when film historians started writing about the Hollywood studio era. It was not discovered until 1970, when it was found in the 20th Century-Fox archives. As a result, Lazybones was, as Swiss film historian Hervé Dumont put it in his magisterial book on the director, “revealed as the most poignant–and the most accomplished–of Borzage’s works before Seventh Heaven.”

Year by year since we started this annual list, I looked forward to recommending Lazybones, and now we arrive there. I rewatched it for the first time to see if it really deserved to make one of the top ten. The answer is yes. For me, this is as good as 7th Heaven, or as near as makes no difference.

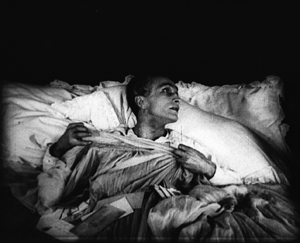

It’s difficult to describe the plot of Lazybones, since it doesn’t have much of one. Steve (played by the amiable Buck Jones) is a very lazy young man living in a rural village. He has a girlfriend, Agnes, whose mother scorns him. The girlfriend has a sister, Ruth, who returns home with a baby in tow. In despair, Ruth leaves the baby on a riverbank and tries to drown herself (image at top of section). Steve rescues her, and she explains that unknown to her family, while she was away she married a sailor who subsequently went down with his ship. She has no proof of this and knows her tyrannical mother will assume that the baby is illegitimate. Steve decides to keep her secret and adopt the apparent foundling himself.

All this happens during the initial setup. Then the little girl, Kit, grows up into a young lady. Along the way, not all that much happens. Steve, lacking any goals, stays lazy, which sets him apart from the energetic, ambitious protagonists of most Hollywood films. Kit is shunned by her classmates and the townspeople, and Steve tries to shelter her from all this. He loves Agnes but quickly loses her to a richer, more respectable man. He goes off to fight in World War I, becomes an accidental hero, and returns home after perhaps the shortest battlefront scene in any feature of the period. Kit finds a boyfriend.

What makes all this riveting viewing is its mixture of quiet comedy and poignancy. Steve is so amiably and unrepentantly loath to work that he is scorned by nearly everyone, and yet he commits an act of great kindness for which he gets no credit at all, except from his devoted mother. It is clear that these snobbish townspeople would scorn him even if they knew how he has kept Kit out of the orphanage and made a happy life for her.

The film is beautifully shot, and Borzage displays such an easy mastery of constructing a scene, particularly in depth, that it is easy to miss the underlying sophistication. Early on, Agnes and her mother arrive at Steve’s house. As Agnes waits outside the fence in the foreground, Steve tips his hat to her, in the foreground with his back to the camera. The mother passes by him toward the house, her mouth fixed in a sneer. We may think that Steve is oblivious to this, but once she passes out of the frame in the foreground, he puts his hat back on and slips it down over his face rather cheekily as he glances at her, his gesture suggesting his indifference to her opinion of him. (Note also the subtle touch of his lazily fastened suspenders.)

Borzage has mastered the use of motifs that are so characteristic of Hollywood cinema. There’s a running gag about the dilapidated gate of the picket fence around Steve’s and his mother’s house, with each person remarking “Darn that gate!” as they struggle through it. The repetition becomes cumulatively funnier because about two decades pass in the course of the film without the thing being fixed. The acting, particularly of Buck Jones and Zasu Pitts (as Ruth), is affecting.

It’s difficult to convey the charms of such an unconventional film, but give it a try and you may be bowled over, too.

A superb DVD transfer of Lazybones was included in the lavish Murnau, Borzage and Fox box (2008). The 20th Century-Fox Cinema Archives series offers it separately as a print-on-demand DVD-R. I’ve not seen it but suspect that there would be some loss of quality in this format. Besides, every serious lover of cinema should have that big black box sitting on their shelves next to the Ford at Fox one.

Returning to the more familiar classics, my final Hollywood film of the year is King Vidor’s The Big Parade.

Apart from its success and influence, however, The Big Parade remains an entertaining, funny, and moving film. Vidor’s scenes often run a remarkably long time, suggesting the rhythms of everyday life. One such action involves James fetching a barrel back to where he and his mates are staying so that he can turn it into an outdoor shower. When nearly back, he encounters Melisande, whom he initially can’t see. His stumbling about and her increasing laughter at his antics are played out at length (see top), as is a supposedly improvised scene shortly thereafter where James tries to teach Melisande how to chew gum.

A very different sort of prolonged scene is the long march of James and his comrades through a forest full of German snipers in trees and machine-gunners in nests. They begin by walking through an idyllic-looking forest, then increasingly encounter fallen comrades, and finally reach the Germans.

For years the prints of The Big Parade available were less than optimum, with some based on the 1931 re-release version, where the left side of the image had to be cropped to make room for the soundtrack. A 35mm negative was discovered relatively recently, however, and is the basis for the superb DVD and Blu-ray versions released in 2013.

Finally, I turn you over to David for some comments on films that fall within his specialties.

Eisenstein, action director

Watch this. Maybe a few times.

These two seconds, violent in both what they show and the way they show it, seem to me a turning point in film history. Here extreme action meets extreme technique. The spasms of the woman’s head, given in brief jump cuts (7 frames/5/8/10), create a sort of pictorial fusillade before we get the real thing: a line of riflemen robotically advancing into a crowd.

It’s not usually recognized how often changes in film art are driven by showing violence. Griffith’s last-minute rescues usually take place in scenes of massive bloodshed; not only The Birth of a Nation but the equally inventive Battle at Elderbush Gulch use rapid crosscutting to treat a boiling burst of action. The Friendless One’s pistol attack in Intolerance is rendered in flash frames that Sam Fuller might approve of. Later, the Hollywood Western, the Japanese swordplay film, the 1940s crime melodrama, the Hong Kong action picture, and many other genres pushed the stylistic envelope in scenes of violence. Hitchcock’s vaunted technical polish often depended on shock and bloodletting, from a bullet to the face (Foreign Correspondent) to stabbing in the shower (Psycho). The free-fire zone of Bonnie and Clyde and Peckinpah’s Westerns took up the slow-motion choreography of death pioneered by Kurosawa. Extreme action seems to call for aggressive technique, and intense action scenes can become clipbait and film-school models.

Sergei Eisenstein is celebrated as the theorist and practitioner of montage, whatever that is; but he insisted that what he called expressive movement was no less important. Just as montage for him came to mean the forceful juxtaposition of virtually any two stimuli (frames, shots, elements inside shots, musical motifs), so he thought that expressive movement ranged from a haughty tsar stretching his stork neck (Ivan the Terrible) to peons buried up to their shoulders, squirming to avoid horses’ hooves (Que viva Mexico!). In Eisenstein, psychology is always externalized, crowds move as gigantic organisms, and any action can turn brutal. (I fight the temptation to call him S & M Eisenstein.) We can trace influences—Constructivist theatre, the chase comedies coming from America, his interest in kabuki performance—but when he moved into cinema from the stage, Eisenstein became an action director, in a wholly modern sense.

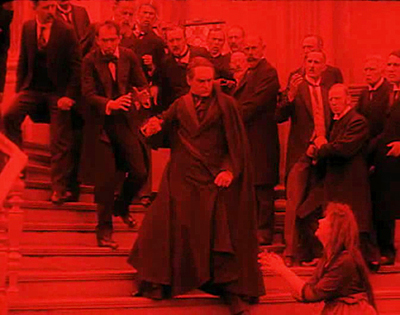

Eisenstein’s first two features bracket the year 1925. Strike was premiered in January, The Battleship Potemkin in December. The first was apparently not widely seen outside Russia until the 1970s, but the second quickly won praise around the world. Potemkin’s centerpiece, the Odessa Steps sequence, became an instant critical chestnut, proof that cinema had achieved maturity as an art. Owing nothing to theatre, this massive spectacle was as pure a piece of filmmaking as a Fairbanks stunt or a Hart shootout. But of course Eisenstein went farther.

The Steps sequence was probably the most violent thing that anybody had ever seen in a movie. A line of soldiers stalks down the crowded staircase. A little boy is shot; after he falls, skull bloodied, his body is trampled by people fleeing the troops. Another man falls, caught in a handheld shot. A mother is blasted in the gut, and her baby carriage, jouncing down the steps, falls under a cossack’s sword. A schoolmistress who has been watching in horror gets a bullet in the eye–or is it a saber slash? The sequence ends as abstractly as it began, if “abstractly” can sum up the horrific punch of these images.

The film is much more than this sequence, of course, but every one of its five sections arcs toward violence, and each payoff is shot and cut with punitive force. The mutiny itself is a pulsating rush of stunts, unexpected angles, and cuts that are at once harsh and smooth. The whole thing starts with a rebellious sailor smashing a plate (in inconsistently matched shots) and ends with the ship confronting the fleet, a challenge rendered by percussive treatment of the men and their machines.

In Strike, Eisenstein rehearsed his poetry of massacre, along with a lot of other things. Instead of rendering an actual incident, as in Potemkin, here he portrays the typical phases any strike can go through. The plot starts with injustices on the shop floor, escalates to a walkout, and then—of course—turns violent, as provocateurs make a peaceful demonstration into a pretext for harsh reprisals. Throughout, Eisenstein experiments with grotesque satire and caricature. The workers are down-to-earth heroic; the capitalists are straight out of propaganda cartoons; the spies are beastly, the provocateurs are clowns. Every sequence tries something new and bold, and weird.

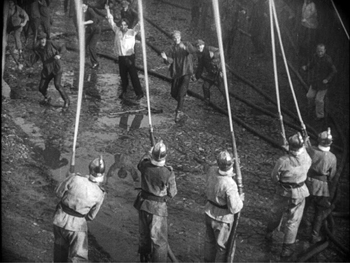

The most famous passage, well-known from his writings if not from actual viewing, is the climax. Here a raid upon workers in their tenements is intercut with the slaughter of a bull. Montage again, of course, but what isn’t usually noticed is the remarkable staging of that police riot, with horsemen riding along catwalks and fastidiously dropping children over the railings. For my money, more impressive than this finale is the earlier episode in which firemen turn their hoses on the workers’ demonstration. The workers scatter, pursued by the blasts of water, until they are scrambling over one another and pounded against alley walls. This is Strike’s Odessa Steps sequence, and for throbbing dynamism and pictorial expressiveness–you can feel the soaking thrust of the water–it has few equals in silent film.

For Eisenstein, the bobbing, screaming head in my clip was the “blasting cap” that launched the Odessa massacre. Is the woman the first victim of the troops, or is her rag-doll convulsion a kind of abstract prophecy of the brutality to come? Yanked out of the actual space of the action, it hits us with a perceptual force that goes beyond straightforward storytelling. Kinetic aggression, making you feel the blow, is one legitimate function of cinema. Eisenstein is our first master of in-your-face filmmaking.

After many tries, archives have given us superb video editions of Potemkin and Strike, both available from Kino Lorber. Potemkin’s original score captures the film’s combustible restlessness. Strike seems to have been shot at so many different frame rates that it’s hard to smooth out, but the new disc makes a very good try, and it’s far superior to the draggy Soviet step-printed version that plagued us for decades.

Chamber cinema

Every so often a filmmaker decides to accept severe spatial constraints, creating what David Koepp calls “bottle” plots. Make a movie in a lifeboat (Lifeboat) or around a phone booth (Phone Booth) or in a motel room (Tape) or in a Manhattan house (Panic Room) or in a remote cabin plagued by horrors (name your favorite). In the 1940s several filmmakers were trying out a “theatrical” approach that welcomed confinement like this; Cocteau’s Les Parents terribles, H. C. Potter’s The Time of Your Life, and of course Rope are examples. Today’s filmmakers are still exploring “chamber cinema.” The Hateful Eight is the most recent instance, with most of its chapters set in Minnie’s Haberdashery.

Typically, the chamber films in any period aren’t “canned theatre” like the PBS or English National Theatre broadcasts. Chamber films push the camera into the space, often showing all four walls and letting us get familiar with the rooms the characters inhabit. But this requires not only a carefully planned setting but also a good deal of cinematic skill in smoothly taking us to the primary zones of action.

Carl Dreyer was one of the earliest exponents of chamber cinema. He had seen initial examples in German Kammerspiel (chamber-play) films like Sylvester (1924) and had made a mild version himself in Michael (1924). Dreyer took the aesthetic to new heights in The Master of the House (1925).

Long before Akerman’s Jeanne Dielmann, Dreyer gave us a film about housework. Ida’s husband Victor is unemployed, so while he loafs and drifts around town, she struggles to keep things going. He pays her back with scorn and abuse. The plot is structured around two days, which yield a before-and-after pattern. At the end of the first, Ida leaves Victor, and a month later, his realization of his mistakes is revealed by his behavior in the household. The drama comes not only from the characters’ conflicts but from the way they handle everyday things like butter knives and laundry lines.

Rendering the household in all its specificity obliges Dreyer to rethink continuity filmmaking. He lays out the geography of the home by shooting “in the round” and cutting on the basis of eyelines and frame entrances. (He displays the same confidence in the “immersive camera” that Lubitsch displays in Lady Windermere’s Fan.) He trains us to notice landmarks, to associate bits of action with particular areas of the apartment, and to sense the characters’ changing emotions in relation to small adjustments in composition. The film is an exceptionally fluid, assured one, and it prepares for more daring Dreyer experiments to come: the fragmented interior spaces of La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc, the creeping camera of Vampyr, and the intensely theatricalized late films Day of Wrath, Ordet, and Gertrud. Little-known at the time, The Master of the House has come to be regarded as one of the most quietly perfect of silent films.

The most lustrous edition of The Master of the House is the Criterion release. It contains an in-depth interview with Danish film historian Casper Tybjerg and a visual essay that Abbey Lustgarten and I prepared. Criterion has posted an extract from the essay. More about this release is here.

In connection with the eleventh edition of Film Art: An Introduction, to be published in mid-January, we have added ten new online Connect video examples. These include one based on clips from the Blu-ray of The Gold Rush, which the Criterion Collection has kindly allowed us to use. We discuss two contrasting styles of staging used for comedy effects in the isolated cabin set.

The Dumont quotation is from his Frank Borzage: Sarastro à Hollywood (Cinémathèque française, 1993), p. 108.

Lea Jacobs and Andrea Comiskey have examined the complicated early distribution of The Big Parade in their “Hollywood’s Conception of Its Audience in the 1920s,” The Classical Hollywood Reader, Steve Neale, ed. (Routledge, 2012), p. 97.

Eisenstein’s aesthetic of expressive movement, and its relation to montage, is discussed in David’s The Cinema of Eisenstein. On Dreyer’s “theatricalized” cinema see his The Films of Carl Theodor Dreyer, and this essay on its sources in 1910s tableau filmmaking. Eisenstein’s exactitude in matching gesture to sound and cutting is demonstrated in Lea Jacobs’ Film Rhythm after Sound, reviewed here.

Lev Kuleshov’s second feature, The Death Ray, doesn’t make our top-ten list for 1925, but as a bonus we include its poster (by Anton Lavinsky), which must rank among the most beautiful of that year.

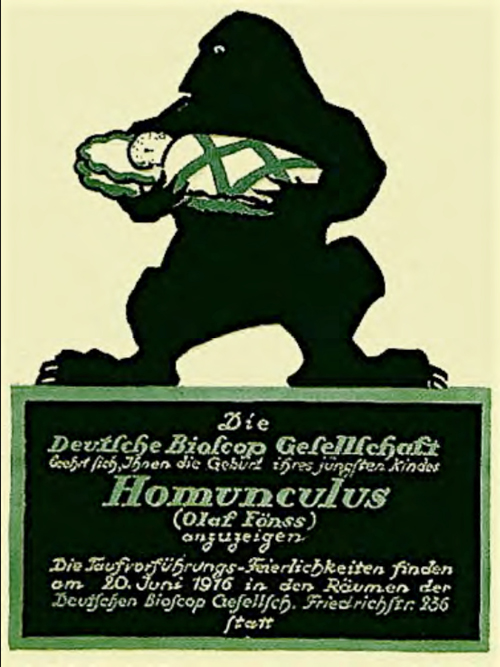

The return of Homunculus

On 21 November, the Museum of Modern Art in New York will be screening a version of Otto Rippert’s long-lost German serial Homunculus (1916). It was reconstructed by Stefan Drössler and his colleagues at the Munich Film Museum on the basis of material from the Moscow Film Archives and other collections. Here’s the background offered by the opening titles on this version.

Homunculus was shown as a six-part series in movie theaters in Germany and its occupied territories in 1916, in the midst of World War I. Each episode was about an hour long. In 1920 the opus was reissued as a three-part version. Scenes were shifted around and new intertitles added.

The following reconstruction adapts the structure of the reissue edition, but it also contains some scenes that had been shortened for the later version and often only survived as photographs.

Fewer than 20% of the original German intertitles have been preserved or are known in their exact wording. Newly worded texts for this reconstruction were based, when possible, on information from contemporary program notes and reviews; also, some were translated back from foreign-language versions of the film and others were created from keywords scratched into the film as montage cues.

For the first time, the current work print makes it possible to recognize the original concept of the entire series.

Today, as a preparation for this very important event, each of us offers you something. First Kristin sketches the trend of fantasy filmmaking in German cinema of the 1910s. After providing this context for the film, David offers some thoughts on this new version of Homunculus and its value for us today.

Kristin here:

The seeds of Expressionism

Many viewers who come to Homunculus for the first time may be expecting traits of the most famous German silent film trend, Expressionism. And indeed historians have mentioned Rippert’s serial, along with Der Student von Prag (The Student of Prague, 1913), Hoffmanns Erzählungen (Tales of Hoffman, Richard Oswald, 1916), and others, as forerunners of the Expressionist movement.

But we don’t have a very concrete account of how these earlier films led up to the more famous trend that began with Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari’s release in early 1920. Moreover, at first glance there aren’t many visual qualities in these earlier films that remind you of Expressionism. They display few or none of those Expressionist distortions of mise-en-scene influenced by contemporary trends in painting and theatre. Similarly, the acting, while exaggerated in a fashion common during the 1910s, seldom reaches the extreme stylization of the performances in Expressionist films.

Yet there are clearly some other similarities between the two groups of films. Most obviously, the early films brought to prominence two related genres to which many of the Expressionist films would belong: the phantastischen film and the Märchenfilm, or fairy-tale film.The main examples of the latter all starred Paul Wegener: Rattenfänger von Hameln (The Pied Piper of Hameln, 1918), Hans Trutz im Schlaraffenland (Hans Trutz in the Land of Cockaigne, 1917), and Rübezahls Hochzeit (Rübezahl’s Wedding, 1916).

For Expressionist filmmakers, elements of the supernatural or the legendary could motivate highly stylized mise-en-scene. In contrast, these 1910s films often used relatively realistic mise-en-scene. Location shooting, straightforward period costumes, and skillfully executed trick photography introduced the fantastic elements into the milieu of a concrete, seemingly everyday world.

A changing view of cinema

Despite such differences, the two genres provide a specific link between some of the most prominent German films of the 1910s and those of the Expressionist movement. Moreover, fantasy films seem to have provided a basis for at least a tentative exploration of theoretical issues surrounding the relationship of cinema to the other arts. In Germany, cinema had previously been compared primarily to literary and theatrical arts, but Wegener’s Der Student von Prag and other films led to a wider consideration of cinema in relation to visual arts such as painting.

In a 1916 lecture, Wegener expressed dissatisfaction with most of what had previously been done with the cinema. He sought to establish the cinema as an independent visual art, separated from theatre and literature:

When a new technology is developed, it is initially cultivated in relation to existing ones, and a new idea does not immediately find its own unique form. The first steamboats looked like big sailing schooners, except that instead of masts they had high funnels. The first railway cars copied mail coaches, the first automobiles kept the large bodies of landaus, and the cinema was like pantomime, drama, or the illustrated novel.

A more broadly based view of the cinema as combining theatrical and graphic arts created a newtradition which carried over from the 1910s to the Expressionist movement of the 1920s. These early films may have become models for the development of an “art cinema” movement in the next decade.

The painterly approach to film promulgated by Wegener lingered in German cinema for about a decade. Starting around 1924, a new approach, based on the moving camera and a more realistic three-dimensional space, would largely replace the older one.

Frames and books

Der Student von Prag.

Aside from this specific link created by Wegener’s emphasis on the pictorial powers of the camera, several conventions of the fantasy films of the 1910s look forward to Expressionism. Perhaps most notable among these devices is the use of the frame story.

Expressionist films frequently employ this device: Francis’ tale to the fellow asylum inmate in Caligari, the record of the Bremen town historian in Nosferatu (as well as the imbedded narratives of the Book of the Vampyres and the ship’s log), the young poet hired to write publicity anecdotes for a sideshow in Wachsfigurenkabinett, and so on.

Yet this pattern was already well established during the 1910s. Der Student von Prag begins and ends with a poetic scroll (“Ich bin kein Gott/bin kein Dämon …”), with the final return leading to a shot of Balduin’s gravestone—upon which sit the Doppelgänger and a crow. (The 1926 remake, which has some distinct Expressionist touches, begins and ends with a gravestone that summarizes Balduin’s life.) Wegener’s other major surviving film from the mid-1910s, Rübezahls Hochzeit, begins with a scene of Wegener, as himself rather than in character as the titular hero, reading to a group of children from a book entitled Rübezahls Hochzeit.

In some cases the frame story introduces multiple embedded narratives. Richard Oswald’s two main fantasy films of the pre-1920 era, Hoffmanns Erzählungen (1916) and Unheimliche Geschichten (Uncanny Stories, 1919), both use this technique. The first begins with a prologue showing Hoffmann surrounded by strange characters like Count Dapertutto and Coppelius. Three dream sequences show him incorporating these figures into bizarre stories; the transition from the prologue to the the main portion of the story begins with Hoffmann in bed as the three sinister figures stand over him.

Unheimlische Geschichten begins, as an intertitle announces, with “A fantastic Prologue at an antiquarian book dealer’s.” On the wall are three large pictures depicting a whore, death, and the devil. After the proprietor chases away his customers and departs, the three images come to life and amuse each other by reading tales out of a book. The series of embedded tales, adapted from Poe, Hoffmann, and other authors of the uncanny, form the bulk of the film.

Not all fantasy films of the 1910s contain frame stories or embedded narratives. Characters do, however, often read or write books that contribute major premises or motifs. In Homunculus, Richard Ortmann keeps a large diary, which records his shifting and somewhat contradictory thoughts, feelings and goals—and thus conveys them to us. Joe May’s Hilde Warren und der Tod (Hilde Warren and Death, 1917) also has no frame story. Its opening, however, involves the heroine reading in a book that death is an escape from sadness. This notion becomes a motif, as the figure of Death appears to her at intervals, foreshadowing her eventual surrender. Books would become an important motivating device in Expressionist films, introducing embedded narratives or crucial motifs.

Hilde Warren und der Tod also carries through the pictorial tradition of Der Student von Prag. Here the special effects are not used to allow one actor to play two roles through split exposure. Rather, superimpositions introduce the figure of Death into the everyday scenes of Hilde’s life.

Some early hints of Expressionism

Although the fantasy films of the 1910s don’t contain strongly Expressionist elements, a few stylistic touches foreshadow the distortions of the later movement. Some of these relate to performances by actors who were to become central to the Expressionist movement. In Hoffmanns Erzählungen, for example, Werner Krauss’s stylized acting in the role of Count Dapertutto suggests why he was later cast as Dr. Caligari. Conrad Veidt’s acting and especially his makeup as Death in Unheimliche Geschichten mark him as the ideal candidate to show up in Caligari’s cabinet.

The stylized hand gestures in these two shots are particularly striking, and the same device is carried through in a séance sequence in Unheimliche Geschichten. The lighting of the séance looks forward to more famous scenes in Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler (1922), Feu Mathias Pascal (1926), and The Ministry of Fear (1944)—yet here Oswald introduces a twist by including one more hand than there should be for the number of bodies present.

There are other major films made in 1919 which contain stylistic and generic elements soon to become far more prominent. Lang’s Die Spinnen (The Spiders, 1919-1920) draws upon conventions of the thriller serial which would soon by transmogrified in his Expressionist film, Dr. Mabuse, Der Spieler. Lubitsch’s Die Puppe (The Puppet) and Die Austernprinzessin (The Oyster Princess), both 1919, could be counted as comic Expressionist films that introduced the style into the cinema months before the appearance of Caligari. The exact cut-off date between pre-Expressionism and Expressionism proper is not vitally important. Some 1910s developments in genre and style prepared the way for Expressionism. Caligari, however great its stylistic challenges were, did not appear in a vacuum.

DB here:

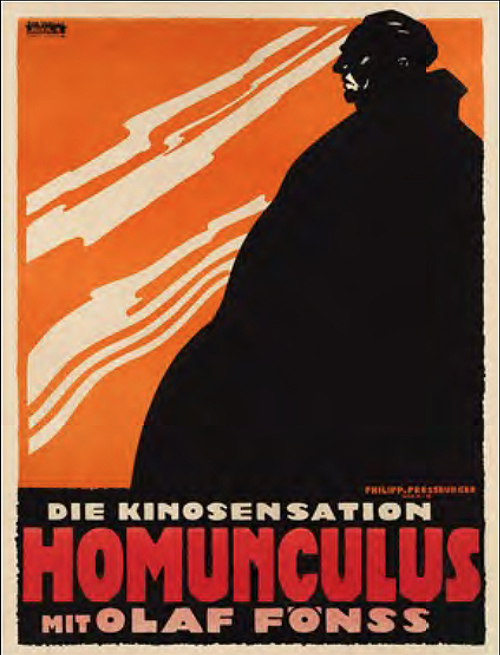

Wanted: Love. #Homunculus

The 1920 reissue of the Homunculus serial compresses its original story considerably, but the outlines are clear. Some omissions in the Munich reconstruction may reflect gaps in the 1920 version. Still, the basic outline of the tale is clear.

Very likely the first test-tube baby, the Homunculus arrives on the scene as the result of a pseudoscientific effort to create life. Out of a bubble, properly zapped, comes an infant.

The baby is brought up in an ordinary human family, thanks to the classic switched-in-the-cradle device. Known as Richard Ortmann, the creature grows up into something of a superman, with extraordinary strength and explosive energy. But his core is hollow. Richard discovers that he lacks fellow-feeling and finds himself alienated from his carousing peers.

When Richard discovers his technological origin, he sets himself a drastic choice: either discover human love or destroy this worthless world.

Each episode replays the same dynamic. Somewhere Richard discovers a possibility of uncorrupted love. But that prospect shatters, either because of prejudice (would you want your daughter to marry a homunculus?) or his sadistic urge to plunge the world into chaos. Only his friendship with Edgar Rodin, one of the scientists who attended his birth, forms an enduring bond across the episodes.

Richard Ortmann plays many roles in his saga. He’s a scientific tinkerer who invents an explosive, a wanderer who ventures into Africa, and a capitalist who enjoys masquerading as a rabble-rouser bent on fomenting rebellion. No sooner has he provoked a war than he tries his own social experiment, that of isolating a young couple in hope of breeding a new society. All these exploits he records in a mighty book

This tome becomes a handy narrative device when the plot demands that other characters learn of his inhuman origins.

Like those films that clone a Stallone or a Van Damme, the series realizes that one monster can be defeated only by another one. The long tale comes to a climax when Rodin creates a second Homunculus and raises him up to conquer Ortmann–already somewhat weakened from age and fear of death. The titanic confrontation is played out on mountain craigs.

Who will win? Or will both perish?

Annihilation, courtesy Homunculus

The rocking-horse rhythm of the episodes, with hope for Ortmann’s redemption rising and inevitably falling, takes some getting used to. To the filmmakers’ credit, they vary the prospects for love: an array of women, a dog, and in the fourth episode a woman who wholeheartedly embraces Ortmann’s wicked side.

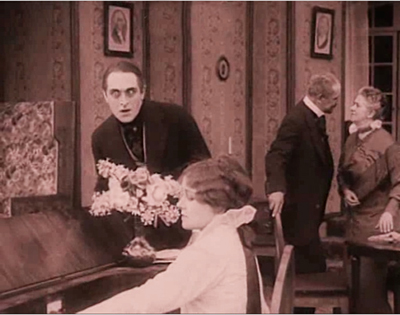

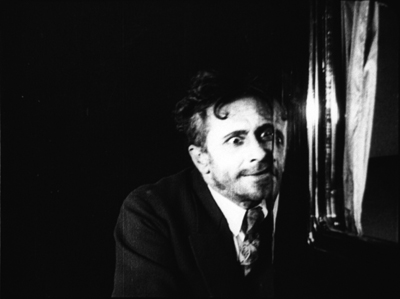

Today’s viewers will also need to accustom themselves to the seething extremes of Olaf Fønss’s performance. Fønss was a major Danish actor who became famous in Atlantis (1913) and who migrated to Germany to star in this series. Fønss conceives his performance as a matter of ferocious glares, raised fists, and heroically villainous postures. It looks overdone to us today.

His box cape, reminiscent of bat wings, helps the brooding effect.

But this isn’t merely a matter of old-fashioned hamming. Fønss’s performance is calibrated to be ragingly different from the other portrayals. Most of the actors exaggerate less, and the pacifist preacher actually underplays. Fønss goes over the top because Homunculus does.

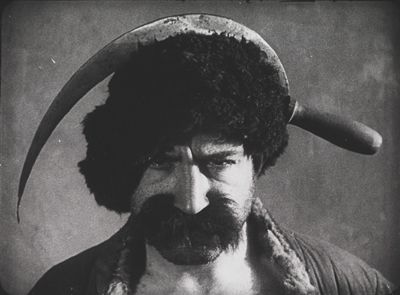

What makes the series compelling? For one thing, it offers a fairly original reworking of the Frankenstein premise. For another, its central conceit of a mad, misunderstood supervillain in search of love can evoke some empathy. There’s also the effort to convey a world in flames, to suggest a cosmic catastrophe with minimal means. While the Great War devastates Europe offscreen, one can hardly avoid thinking of trenches and bombardment in blasted shots like these–which also look forward to the jagged decor of Expressionism.

The student of film technique will, I think, be struck by the filmmakers’ pictorial ambitions. It’s now clear that by focusing just on The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) we have limited our sense of the wide-ranging visual discoveries of German cinema. Homunculus belongs with the splendid string of films that includes Der Tunnel (1915), Algol (1920), I.N.R.I. (1920), and the outstanding pair of 1919 films by Robert Reinert, Opium and Nerven. Reinert, unsurprisingly, wrote the screenplay for Homunculus.

The fourth episode, which I commented on back in the summer (based on a much inferior copy), remains a treat for your eyes, with unexpected camera angles and daring use of depth. In the one on the left, we see touches of Expressionist performance in the orchestration of hands.

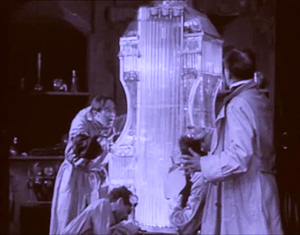

Elsewhere Kristin has remarked that during the 1910s filmmakers began to go beyond basic storytelling and explore the expressive dimensions of cinema—not only in acting but also in composition, lighting, and set design. The Jugendstil curves of the incubator gleam inside a cavernous chamber you might not expect to find in a lab.

Other episodes provide both grand images—landscapes, sumptuous sets, crowd scenes—and an arresting, small-scale play of light and shade. A purely expository shot of Ortmann approaching Steffens’ study becomes a little suite of shadow patterns, stressed when Ortmann pauses and swivels to the camera and creates a pictorial climax.

Seeing the three-dimensional lighting effects of German cinema of the mid-1910s onward, I wonder whether Caligari‘s jutting, broken-up planes and painted shadows are not only a borrowing from Expressionist painting but also a reaction against the rich volumes created by directors like Rippert.

In all, Stefan Drössler and all the archives and individuals working with him have done world film culture a great service. As with Gance’s Napoleon and Lang’s Metropolis, more footage may appear and need to be integrated into this version. Perhaps some day we’ll have something approaching the full scope of the original series. For now, we should be thankful that another silent classic steps out of the shadows and forces us to rethink what we thought we knew about the history of cinema.

Many thanks to Stefan Drössler for his assistance in preparing this entry.

At Nitrateville Arndt has posted helpful synopses of all six parts of the restoration. Leonardo Querisima offers a wide-ranging discussion in “Homunculus: A Project for a Modern Cinema,” in A Second Life: German Cinema’s First Decades, ed. Thomas Elsaesser and Michael Weidel (Amsterdam University Press, 1996), pp. 160-167. Excerpts can be found here.

Kristin’s discussion of fantasy films is excerpted from her essay “Im Anfang War…: Some Links between German Fantasy Films of the Teens and the Twenties,” in Before Caligari: German Cinema, 1895-1920, ed. Paolo Cherchi Usai and Lorenzo Codelli (Pordenone: Bibliotexa dell’Immagine, 1990), 138-161. The Wegener quotation is from Paul Wegener, “Die künsterlischen Möglichkeiten des Films,” in Kai Möller, ed., Paul Wegener: Sein Leben und seine Rollen (Hamburg: Rowohlt Verlag, 1954), p. 102. Translation by KT.

Elsewhere on this site we discuss other neglected German films of the period: Der Stoltz der Firma (The Pride of the Firm, 1914); Der Tunnel (1915); Asta Nielsen features of the teens; Doktor Satansohn (1916); Hilde Warren und der Tod (1917); Die Pest in Florenz (The Plague in Florence, 1919, directed by Rippert after Homunculus); late-1910s Lubitsch; Algol and I. N.R.I. (both 1920); and Der Golem (1920). I have an essay on Robert Reinert’s remarkable films in Poetics of Cinema. Some day I hope to write more about Paul Leni’s war drama Das Tagebuch des Dr. Hart (Dr. Hart’s Diary, 1917) and Joe May’s energetic and entertaining serial Die Herrin der Welt (Mistress of the World, 1919).

Homunculus and his friends

Sappho (1921).

DB here:

Of the big-ass explosion movies, only two items in this summer’s spate of them have intrigued me. I liked Mad Max: Fury Road well enough, but not as much as MM2 and 3. I look forward to Mission: Impossible—Rogue Nation, in a series for which I have much affection. As for the arthouse releases, the ones I’ve already seen are A Pigeon Sat… (good but not as sardonically bizarre as earlier Andersson, methinks) and About Elly. That one is a masterpiece.

I have stronger reasons than indifference for missing so much, and for tardy blogging besides. I’ve been on my annual trip to Belgium for research and lecturing in the Summer Film College. As a result, your recent movie experiences and mine have been divergent, perhaps even insurgent.

Apart from two screenings in the Brussels Cinematek’s Hou series (their restoration of Green, Green Grass of Home, gorgeous vintage print of City of Sadness), I spent the last four weeks watching 35mm prints of movies by Godard, movies starring Burt Lancaster, and assorted silent films from the 1910s and 1920s. I also re-met one of the most charming directors I know of, and in general had a hell of a time.

Today’s entry focuses on my archive work. Next up, a report on the Summer Film College.

Conrad’s many moods, mostly unhappy

Landstrasse und Grosstadt.

The archive stuff was recherché. I’ve been trying to see as many 1910s and early 1920s features as I could, but this time around I didn’t catch anything as mind-bending as Jasset’s Au pays de ténébres (1911) or Doktor Satansohn (1916) or Fabiola (1919) or I.N.R.I (1920), encountered on earlier visits to the Cinematek. I did get further confirmation that in Germany the “tableau style” exploited so vigorously in Europe and somewhat in America in the 1910s, was pretty much replaced by Hollywood-style editing by 1920. And I got some welcome doses of Conrad Veidt, another favorite in this vicinity.

In Die Liebschaften des Hektor Dalmore (“The Liaisons of Hektor Dalmore,” 1921), Veidt plays a callous playboy who keeps on retainer a man who looks very much like him. It’s a lifestyle choice. When a compromised woman’s father demands that Hektor do the right thing, he sends out his double to marry her. Surprisingly, the double isn’t rendered through trick photography. Richard Oswald, always a fast man with a gimmick, found a pretty good Veidt lookalike, which can’t be easy to do.

The hero’s Casanova complex carries him from dalliance to dalliance, and as you’d expect in a twins situation, there are confusions between the real and the fake Hektor. Fights and abductions liven things up. The climax is a duel in which the real Hektor, overconfident, learns to his grief that an outraged husband is a better marksman. The scene is handled through brisk shot and reverse-shot, garnished with an over-the-shoulder shot as Hektor aims his pistol. And there are dashes of mildly Expressionist set design (furnished by Hans Dreier). Veidt in a phone booth does the décor proud. But he doesn’t need fancy sets to project a feeling: on his deathbed, his expression and his clutching fingers show a man bereft of erotic illusions.

The other Veidt vehicle lacked doubles but not ambition. Landstrasse und Grosstadt (“Village and City,” 1921) casts him as Raphael, a wandering violinist who teams up with Migal, an organ grinder. They become a popular act in the big city, and as Raphael’s playing improves, Migal becomes his manager. Nadia, a woman who joins them, falls for Raphael and shares his success. But in an accident he suffers a hand wound and his career slumps. Migal sees his chance to move in on Nadia. Perhaps this shot gives you a hint of his designs.

Actually, most of Landstrasse and Grosstadt isn’t as hammy as this. A very nice shot shows Raphael in silhouette approaching a mansion to hear his rival Cerlutti give a salon concert. And of course Conrad gives the blind violinist a delicate, spectral pathos, as shown above.

Artificial man lurks in the shadows, destroys humanity

Sappho.

All the films I saw broke down scenes into many close shots, reminding us that Caligari (released 1920) probably wasn’t typical of German staging or cutting of that moment. It now seems to me almost consciously anachronistic, rejecting the reverse angles and precise scene breakdown that were becoming common. In Die Ehe der Fürstin Demidoff (“The Marriage of Fürstin Demidoff,” 1921), when a governess drags a recalcitrant girl back to her bedroom, the action is split up into four shots, all of different scales from close-up to long-shot.

Although I saw a fragmentary print of Sappho (1921), it’s clear that in parts it has the audacious monumentality of a Joe May production. The most staggering shot is that of the Opera surmounting today’s entry, but there’s no shortage of striking images. Above I include a shot of a madman that, thanks to window reflections, suggests his split-up psyche.

Sappho also doesn’t shirk editing effects either. During a frantic automobile ride, there are glimpses of hands on a steering wheel, a foot on brakes, panicked passengers, and POV shots through the windshield. Forty-nine shots rush by in a flurry, anticipating similar sequences in French Impressionist films like L’Inhumaine (1924). Feuillade was experimenting with rapid cutting of action at about the same time.

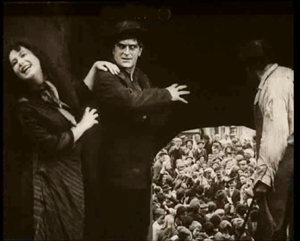

The most impressive, and nutty, film in this batch came from Homunculus, the largely lost German serial released through 1916 and into early 1917. The script was written by one of the blog’s favorite peculiar directors, Robert Reinert. The plot involves an artifical man created in the lab, à la Frankenstein’s monster. He’s a superman, in both strength and ambitions. The only surviving episode of the serial is Die Rache des Homunculus (“The Revenge of Homunculus,” 1916). (But see the codicil.) In this installment, posing as Professor Ortmann, Homunculus decides to drive humanity to destroy itself. He assumes a disguise to rouse the rabble, even inducing them to turn against himself in his Ortmann guise.

As in Expressionist drama, this overachiever is pitted against a crowd that, in the end, pursues him maniacally.

Director Otto Rippert gives us splendid mass effects in a quarry and along a beach, but there are also deep tableau images and sustained chiaroscuro, particularly in a showing the heroine Margot shrinking from Homunculus as he locks his rival in a dungeon.

Fans of Metropolis will notice that Rippert anticipates Lang’s unison choreography of crowds, as well suggesting that mob frenzy can create a sort of ecstasy in the woman who’s swept along.

In her book The Haunted Screen Lotte Eisner traces the films’ mass spectacle back to the stage work of Max Reinhardt and other theatre directors of the era. On the basis of this episode alone, Homunculus ranks with Algol and May’s Herrin der Welt as an example of big-scale fantasy in German silent cinema. Who needs Ant-Man when we have Homunculus?

Next time: Burt and Jean-Luc, together again for almost the first time.

Thanks to Nicola Mazzanti, Francis Malfliet, Bruno Mestdagh, and Vico de Vocht for their assistance during my visit to the Cinematek.

Kristin analyzes stylistic conventions of German cinema of this period in her Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood (available for download here). She’s written on Caligari here and here.

A so-so copy of Sappho is on YouTube.

On Homunculus, Leonardo Querisima offers a wide-ranging discussion in “Homunculus: A Project for a Modern Cinema,” in A Second Life: German Cinema’s First Decades, ed. Thomas Elsaesser and Michael Weidel, pp. 160-167. Substantial excerpts can be found here.

Munich archivist Stefan Drössler has recovered a mass of Homunculus footage and has assembled a version of the serial, which premiered last year in Bonn. Nitrateville has the story.

The Brussels Cinematek will release its Hou restorations on DVD early next year: Cute Girl, The Boys from Fengkui, and Green, Green Grass of Home. As a reminder, my video lecture on Hou is here.

The still below, taken as the prints were readied for the Summer Film College, points ahead to our next entry–number 701, as it turns out.

The ten best films of … 1924

Die Nibelungen: Siegfried

Kristin here:

For a seventh year running, we skip ranking the current year’s films and instead hark back 90 years.

We started out with a list that was essentially an appendix to an entry, but soon we were dedicating whole entries just to the list. Our entries for past years are here: 1917, 1918, 1919, 1920, 1921, 1922, and 1923.

These lists are our way of calling attention to important silent films that some readers may have overlooked. In one case here we point out a largely forgotten film that deserves to be better known, in the hope that an archive will take the hint. With the proliferation of silent-film festivals, of DVD and Blu-ray releases with restored prints and supplemental material, and of TCM’s eclectic screenings of foreign and silent titles, there seems to be considerably more interest in these early classics. Herewith our choices for 1924.

For the last few years I’ve struggled to fill out the full list of ten films with truly deserving items. But as I’ve been predicting, the 1924 choices fell easily into place. As usual, some of these are obvious picks, already famous to most readers. Others are less obvious, and a few are unknown except to specialists. Some, though very important historically and artistically, are not currently available on DVD, which is a real shame.

At last, the USSR

Films in the Soviet Montage style make up one of the most important cinema movements of all times. The key filmmakers of the movement, Eisenstein, Pukovkin, Dovzhenko, Kuleshov, Kozintzev and Trauberg, and others began their work later than the German Expressionist and French Impressionist directors. But at last one joins our list, with Lev Kuleshov’s The Extraordinary Adventures of Mr. West in the Land of the Bolsheviks.

Although Kuleshov’s work has become more widely available, his most familiar work is still By the Law (1926), a grim tale of two members of a gold-prospecting team agonizing over how to bring to justice a colleague who has committed a terrible crime. Mr. West couldn’t be more different. This hilarious and grotesque comedy satirizes American perceptions of the new Soviet Union, as Mr. West, president of the YMCA, comes to for a visit, his faithful cowboy friend Jeddie in tow. They’re terrified of the barbaric land they expect to encounter, and a gang of thieves dupe Mr. West by dressing up in outfits that caricature West’s images of Bolsheviks (above).

In making the film, Kuleshov and his team drew upon the experiments they had been doing in his classes he ran of the early 1920s. Film stock was scarce and all he and his students could do was practice staging scenes and make short editing experiments. They explored the possibilities of “biomechanical acting,” a style based more on gymnastic control and energy than on psychological subtleties of facial expression.

Once the group did get the resources to make a feature, their delight is evident in the lively editing and the exuberant performances. Alexandra Khokhlova, a gangly woman who was married to Kuleshov and starred in most of his films, plays a vamp who tries to lure Mr. West into her toils. Pudovkin, who studied with Kuleshov before going into directing himself, is the well-dressed gang leader who pretends to guide Mr. West away from danger. Boris Barnet, also to become a major director, performs feats of derring-do as Jeddie tries to save Mr. West.

Mr. West is not only a satire on Western fears of post-Revolutionary Russia but also a parody of American serials. (The latter was something Barnet soon tried in an actual serial, his 1926 Miss Mend.)

Mr. West is available on DVD in Flicker Alley’s set, “Landmarks of Early Soviet Film.”

German Expressionism begins to wind down

Last year I was hard put to pick a film to represent the German Expressionist movement in the top ten. I chose Erdgeist but mentioned Schatten and Raskolnikow as runners-up. By 1924 there were fewer Expressionist films released, though the movement would linger on until 1927, mainly carried on by the two greatest directors who had worked in the Expressionist movement: F. W. Murnau and Fritz Lang. Each of these contributed a classic film in 1924: Murnau’s The Last Laugh and Lang’s two-part epic: Die Nibelungen: Siegfried and Kriemhild’s Revenge).

The Last Laugh isn’t really Expressionist. The sets are mildly in the style, but what really fascinated Murnau at this point was the freedom of camera movement introduced by French Impressionism. He set out to make a character study. Emil Jannings plays a doorman in a large hotel (none of the characters’ names are given). His regal bearing and fancy uniform bring him respect among his fellow employees and from relatives and neighbors in the lower-middle-class neighborhood where he lives. He has aged to the point where he carry large luggage and is abruptly demoted to work as a rest-room attendant.

Murnau introduced what came to be known in Germany as the entfesselte Kamera, the “unfastened camera,” beginning in the opening shot where an elevator with a grill descends, carrying the camera and dramatically revealing the lobby. Murnau may have been directly influenced by one of last year’s top-10, Cœur fidèle, where Epstein put his camera on a spinning-swings carnival ride. Murnau saw other uses for the device. Like the Impressionists, he conveyed drunkenness through moving camera, though in this case he put the actor and camera on a turntable, so that the room spins past behind Jannings, conveying the dizzy happiness of the doorman at a party (above).

Using more imagination, Murnau follows sound with his camera. As the party ends, musicians exit to the apartment-block courtyard, and one plays a final tune under the window. Starting with a close-up, the camera “cranes” diagonally up and backward until the men are in long shot. A cut takes us to the doorman inside, happily listening.

Actually the camera was not on a crane. Murnau and cinematographer Karl Freund affixed a track over the courtyard with a small metal elevator underneath, so that the camera could move both back and forth and up and down. The camera was not literally unfastened in these cases, but it looked like it was.

Murnau wanted to end the film on a grim note with the protagonist seated alone in the hotel rest room. Commercial considerations led to a happier ending, however, with him unexpectedly becoming wealthy. The twist was so outrageous that Carl Mayer, the scenarist, considered it a comment on Hollywood’s insistence on happy outcomes. Hence the English title The Last Laugh. The original German means “The Last Man.”

The Last Laugh got distribution in the USA, but it was not a success. Hollywood practitioners studied it, though, and started hanging cameras from tracks themselves and trying other tricks. The track backward above a long, laden banqueting table soon became a cliché of Hollywood cinema.

Murnau would make two more mildly Expressionist films, Tartuffe (1925) and Faust (1926) before heading to Hollywood to make the ultimate hanging-camera film, Sunrise (1927)

The Last Laugh is available from Kino in the USA and Eureka! in the UK.

One of my favorite films of the 1920s is Lang’s two-parter, Die Nibelungen: Siegfried and Die Nibelungen: Kriemhilds Rache (Kriemhild’s Revenge). An adaptation of the ancient German myth, it mostly proceeds at a stately pace until the final battle scene. Some may find it slow, especially when compared with the lively, suspenseful Dr. Mabuse der Spieler (1922) and Spione (1928). Yet its leisurely presentation is appropriate to the subject matter. Equally important, lingering over images allows us to notice the details of the extraordinary settings and costumes, with their busy decorated surfaces and their startling arrangements within the shot.

Take the image at the top of this entry. Brunhilde, having been forced to marry King Gunther against her will, envies her sister-in-law Kriemhild, who has married Siegfried, the man Brunhilde loves. In this shot, Brunhilde mounts the steps of Worms Cathedral to confront Kriemhild and assert her right to enter the cathedral first. We see her from behind and then at the upper left as her ladies follow her, wrapped in their patterned hoods and black cloaks, creating an almost abstract composition. Lang build the enormous stairway outside the cathedral in two stages and then used the set imaginatively to stage several ceremonies and dramatic conflicts.

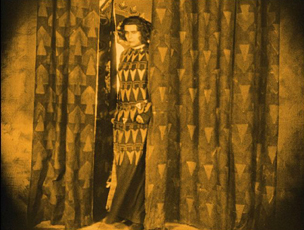

What makes this film Expressionist, I would argue, is the way the actors and settings interact, as in this moment when Brunhilde pauses by her window and then comes forward through the slightly parted curtain, exiting left. She pauses in the opening, her dress seemingly becoming part of the curtains for a moment.

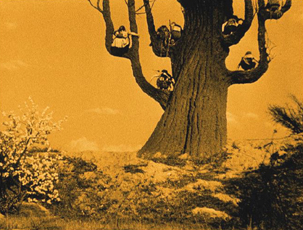

The similarity and the pause have no narrative function, but it’s a very Expressionist composition. Insistent symmetry and acting also contribute to the style. In the second plot, the Hunnish King Etzel asks for Krienhild’s hand in marriage. She agrees on the condition that he will aid her in exacting her revenge on Siegfried’s killers. Upon her move to the land of the Huns, the style becomes a more familiar sort of Expressionism, with distorted trees and buildings that looks like they were built of mud that settled oddly before drying:

The elements of the German tales are all here: love, betrayal, suicide, revenge, presented in images worth savoring.

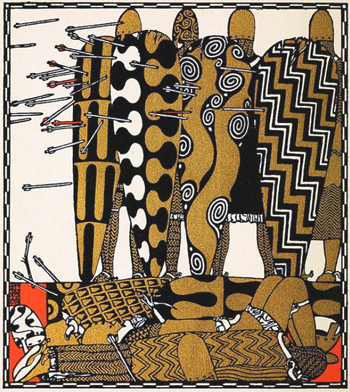

Lang was inspired in his approach to the film’s visuals by some illustrations by Carl Otto Czeschka for a 1909 retelling of Die Nibelungen published in 1909. The heavy decoration on the knight’s shields and many other surfaces in the film somewhat resemble this image, for example:

Yet the resemblance is far from exact. Clearly Lang used elements from these illustrations and took them off in his own direction.

The film has recently been restored and looks great on Blu-ray. Kino in the US and Eureka! in England have brought it out. Both have DVD editions as well.

Scandinavia’s golden age drawing to a close

During the first half of the 1920s, the Swedish cinema was a victim of its own success. Victor Sjöstrom (who has figured in these lists in 1918 and 1921, as well as in our “Lucky ’13” entry), had headed to MGM, becoming Victor Seastrom. In 1924 he released his first two films in 1924: Name the Man and He Who Gets Slapped. The latter was the newly formed MGM’s first in-house production to be released. It was a huge success, no doubt in large part due to the growing stardom of Lon Chaney, and it put the studio on the map and allowed Seastrom to stay in Hollywood, notably for The Scarlet Letter (1926) and The Wind (1928).

Mauritz Stiller (also a previous top-10 choice) was about to head for Hollywood as well, but his final Swedish film is one of his finest. Gösta Berlings Saga, a epic adaptation of Selma Lagerlöf’s novel, was made in two parts lasting over three hours. Many people will know it as the debut film of Greta Garbo. Fans should be forewarned that she is an important character and appears in the early and late scenes but disappears for a long stretch in the middle.

[December 30: As our friend Antti Alanen points out, Garbo had already acted in a comedy, Luffar-Petter (Peter the Tramp, 1922) and in some short advertisements.]

The film begins with Berling, a drunken pastor in a small town, being relieved of his duties. He ends up being taken in the “Chevaliers” at Ekeby the country estate of Margaretha Samzelius, a tough middle-aged woman who runs a group of foundries she has inherited from a lover. The Chevaliers are a group of hangers-0n, men who can drink and laze about most of the time but who must be charming and entertaining at Samzelius’ many dinner parties. Berling has a number of chances to redeem himself but ends up harming the people around him and sinking lower into despair. He is finally redeemed by the love of the Garbo character, Elizabeth, the new bride of a wealthy neighbor, to whom, it turns out through a technicality–and happy coincidence–she is not actually married.

Hansen and Garbo make a gorgeous couple (below left), but they are upstaged by the great Swedish stage actress Gerde Lundequist as Samzelius:

As usual, the film contains lovely scenes in the Swedish landscapes. There are some impressive night sleigh rides, including a famous scene in which Berling and Elizabeth are chased across a frozen lake by wolves. There is also one of the most impressive fire scenes I can recall from the silent era, as Samzelius’ efforts to smoke the Chevaliers out of the guest house where they live and inadvertently sets fire to the big main house as well.

Unfortunately the film was cut down into a single feature for its release outside Scandinavia. The Story of Gosta Berling was the main version that circulated for many years. The Swedish Film Institute restored it in stages as more footage was found, but the current print, at 183 minutes, is still missing some footage.

Beware picking up an older video release with the truncated film. The restored version was released on DVD in the USA by Kino. The original Svensk Filmindustri release (with English, French, Portuguese, German, and Spanish subtitles), is available here. The same DVD comes in a box set of six Swedish silent classics, which is widely available from the usual online sources.

Carl Dreyer has popped up on this blog several times, usually in passing. Not surprising, since David wrote a book about him way back 1981. Here he makes his second appearance on our ten-best lists (the first having been for his first feature, The President, in 1919) with Michael.

The film centers around a wealthy, aging artist, Claude Zoret. The main room of his house is decorated with several eye-catching pieces of sculpture, notably a mysterious battered head that looms in the background of many shots. Is it one of Zoret’s own works? Is it part of a collection of ancient statues? Much of the action takes place here, which has led some historians to place Michael in the tradition of the Kammerspiel. David calls it a borderline case. There are certainly scenes that leave Zoret’s studio, most notably one in a large theater set.

The film has been hailed as an early treatment of homosexuality. Although there is nothing overtly expressed, it is hard not to read such a subtext into the action. Zoret, wonderfully played by Danish director Benjamin Christensen, has many guests and admirers visit him, creating a little all-male coterie. He has taken in a young protegé, a very beautiful and very young Walter Slezak. Zoret refers figuratively to Michael as his son, but there seems to be another tie between the two. Moreover, there may be a hint that Charles Switt, a journalist apparently writing a biography of Zoret (at the center of the frame above), feels some jealousy toward the young man.

Trouble begins when a princess comes to commission a portrait from Zoret. Although he usually doesn’t do commissions, he is intrigued by her face and agrees. During her visits to the studio to pose, she meet Michael, who is immediately smitten. The affair continues as Michael becomes increasingly inconsiderate to Zoret,borrowing money to continue the affair and missing an important showing of his work. In contrast, Zoret shows unwavering generosity to Michael, despite being devastated by his desertion.

Ultimately Zoret paints his last work, showing an elderly, lonely man against a barren seascape. It is hailed as a masterpiece at a party which Michael does not attend.

The character study proceeds at Dreyer’s usual formal pace, and yet it is never dull. As much as any of his silent films, it looks forward in tone to his later sound ones.

A very nice print of Michael is available in the UK from Eureka! (not deliverable to the USA); Kino released what I assume is the same print in the USA.

She was nothing but a poor flower-maker

Every now and then I want to put a film on the list which is impossible to see unless you happen to live near one of the archives that has a print and they happen to program it. Still, in the hope of inspiring someone to restore it and make it available, I proceed.

The film is Jean Epstein’s L’Affiche (“The Poster”). Epstein first made our list last year for the much better known Cœur fidèle. L’Affiche is a bit like the earlier film, a simple melodrama made in the French Impressionist style. Its situation is highly conventional, and its plot depends on a massive coincidence.

The heroine is introduced as Marie, one of several women making artificial flowers. On her lunch break she thinks back to a romantic day she spent in the country. There she meets a young man, Richard. The couple go to an expensive restaurant, and Richard seduces Marie, and then abandons her, driving away alone the next morning.

Three years pass, and Marie has a small child, also named Richard. She enters him in a contest for the most beautiful child, with a cash prize, offered by an insurance company that wants to put the winner on their advertising posters. The boy wins, and Marie signs a 10-year contract for the rights to use little Richard’s image.

The child dies, however, and Marie visits his grave. As she leaves, she sees a huge poster with his image. The campaign has begun. Everywhere in Paris she goes, she sees the poster and finally begs the insurance company to end the campaign. The boss, however, refuses. Marie begins tearing down the posters, and she is soon arrested. Epstein handles the arrest scene without an establishing shot but builds it up through close-ups.

Initially we see only the back of Marie’s head and her arms tearing down a poster. There a cut-in to slightly closer framing as a policeman’s hand comes into the shot and touches her shoulder. A third shot shows her turning to the officer and staring in a way that suggests she is becoming mentally unbalanced. Finally a long shot establishes the scene as a second policemen enters to help arrest her.

It’s the sort of gradual revelation of space that Kuleshov was working with at the same time.

The boss of the insurance company is informed of this and sends his son to file a complaint against her. New copies of the poster are being put up all over town. The son is none other than the Richard who seduced Marie years before. Hearing her tale, he asks her forgiveness and takes her home to his parents. The father forbids their marriage, they marry anyway, and eventually (after his own younger child dies!), the boss blesses the marriage and agrees to take down the posters.

Summarized baldly, it sounds like an impossible plot to take seriously, but Epstein’s delicate, understated approach in presenting it and Nathalie Lissenko’s affecting performance as Marie manage to make it a great film. It’s full of Impressionist moments: Marie’s memory of her romantic day with Richard, a dance scene with rhythmic editing, a dream sequence, and plenty of gauzy shots and fancy wipes at transitions.

Earlier this year I complained because L’Affiche was not included in the big new box set of Epstein’s work, despite almost everything else from the period being there. It’s also not on the box set of films made at the Russian emigré studio, Albatros, even though Epstein’s other three Albatros films are there. I don’t whether there are rights problems or there simply isn’t a good enough print.

At least one streaming service claims to have L’Affiche available, but a search turns up numerous complaints about the site.

I should make mention of one other Impressionist film that came out in 1924. Perhaps it should be on the list rather than L’Affiche. It’s Marcel L’Herbier’s L’Inhumaine. L’Herbier appeared on our 1921 list for El Dorado, and even then I expressed reservations. Most of his films seem cold and by-the-numbers to me, not to mention a bit pretentious. But his films were historically important, and L’Inhumaine was influential in its use of art deco sets. At one time the film was available on DVD, but it seems to be out of print.

Three funny men …

And no, it’s not Chaplin, Keaton, and Lloyd this time. Chaplin didn’t release a film in 1924. His next would be what many would consider his funniest feature, The Gold Rush.

Over the years I’ve stressed that during the 1910s, the three great comics were working in shorts, honing their filmmaking and working up to their great series of features. By 1923 they had fully made the transition: Lloyd made Safety Last and Keaton Our Hospitality. Safety Last had a simpler plot, structured mainly by the stages of the hero’s climb up a building. Keaton went further with a complex story of a romance blooming between members of feuding families, using multiple locations, a developing causal line, and clever motifs. (We analyze it in Chapter 4 of Film Art: An Introduction.)

In 1924, Lloyd achieved a similar complexity with Girl Shy, one of his greatest films. He plays a bashful young tailor’s assistant who is terrified of women. Yet in secret he writes a guide for seducers, taking on the narrational persona of a jaded man of the world. Clearly he has taken his inspiration from movies of the day. The imaginary scenes from his book dramatize his success in gaining the love of a vamp (see bottom) and a flapper. The publishers decide that the book is so over the top that they will publish it as a comic story. During all this Harold develops a relationship with Mary, a quiet young woman from a wealthy family. When her father tries to buy Harold off, he pretends to spurn Mary. She is about to marry a rich man, but Harold determines to stop the wedding.

There develops one of the most epic chase scenes in all silent comedy, and indeed all cinema, as Harold commandeers all manner of vehicles, from cars and wagons to a firetruck and a speeding trolley (above).

Even Keaton never outdid that one. But from 1923 to 1927, these two each created a string of innovative, carefully crafted, hilarious films.

Girl Shy used to be available in a 3-DVD set from New Line, but that is no longer available–though one optimistic third-party seller offers it, still sealed in plastic, for $399.99). Now the individual releases of each DVD seem to be slipping out of print as well. Volume 1, which contains Girl Shy, is definitely out of print. Be forewarned: Volume 2, which includes the wonderful 1927 film The Kid Brother (look for it on a future list) seems like it’s not long for this world, and the same is true of Volume 3, with For Heaven’s Sake (1926).

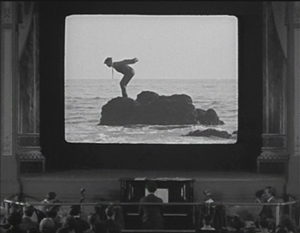

It was difficult to choose between Keaton’s two major releases of 1924, Sherlock Jr. and The Navigator. I chose the former mainly because of its perpetually astonishing transition from the frame story of a small-town projectionist unlucky in love to his dream of himself as a sophisticated detective. His dream takes the form of a movie, and the sleeping projectionist walks through the theater and into the onscreen action. With extraordinary precision, Keaton maintains a long-take framing of the pianist and audience in the auditorium while the hero onscreen undergoes a series of unexpected shot changes. In each he is in the same pose and position within the screen, but the backgrounds change arbitrarily, as when he begins to dive from a rock into the ocean and finds himself landing in a snowdrift:

The result is a marvelously convincing technical feat, giving the illusion of being a single shot as far as the theater is concerned and on the movie screen a character wandering through an appropriately dream-like series of edited shots. In general, Keaton was the most adept of the three great comics at using cinema technology to create gags, and this is his most elaborate attempt. (Though see also his short, The Playhouse, in which multiple exposures, flawlessly managed in-camera, create Keaton clones that play all the roles.)

The plot of the dream emerges after this virtuoso transition, and it remains hilarious throughout. The chase, while not quite as dazzling as the one in Girl Shy, has considerable variety of vehicles (one wonders if the two comics were consciously trying to best each other), including a passage where the hero rides the handlebars of a speeding motorcycle, unaware that the driver has fallen off.

Kino has packaged Sherlock Jr. together with Keaton’s early feature, The Three Ages (1923), and released them both on DVD and Blu-ray.

The third funny man was Ernst Lubitsch. The Marriage Circle was his second Hollywood film, and one of his best. Lubitsch had started out as a comic in silent shorts in Germany, but unlike the famous Americans, he entirely gave up acting to direct. Not that he directed only comedies, but his best films, including Lady Windermere’s Fan, Trouble in Paradise, and The Shop around the Corner, fall into that category.

The Marriage Circle is a light romantic comedy, following a chain of flirtations and misunderstandings. Prof. Stock has realized that his pretty young wife Mizzi has begun to neglect and nag him. She is soon attracted a newlywed, Dr. Braun. Mizzi happens to be an old friend of Braun’s wife Charlotte, which gives her opportunities to flirt aggressively with Braun. Charlotte is in turn admired by Braun’s medical partner, Dr. Mueller, though she laughs off his attempts to woo her.