Archive for the 'National cinemas: Germany' Category

DVDs and Blu-rays for your letter to Santa

The Cure (1917)

Kristin here:

One occasional feature of our blog has been to point out new releases on DVD and Blu-ray, especially of titles that haven’t gotten much publicity. Some of these are easily available at major sources like Amazon, while others have to be ordered directly from their publishers, often abroad. But if you have a multi-standard player, don’t hold back. Ordering from abroad isn’t as intimidating as it might seem. Many sites have English-language sales pages.

We’ve done a lot of these entries by now. You can find them through the DVD category in the list at the right, but I thought it might be useful to give links to all of them here, with brief indications of what each deals with. Some of the DVDs are probably out of print by now, but in this era of eBay and third-party sellers, one can usually track down such things. Then I’ll give a rundown on some recent releases.

The first was Dispatch from the Land of the Long White Cloud, written when David and I were fellows at the University of Auckland in May, 2007. I discussed some of the DVDs of New Zealand films that I had found in stores there. Some are famous, some obscure.

2008 was either a great year for DVDs or we just had more time to deal with them. On January 18, I posted Tracking down Aardman creatures, a guide to the classic animated films of Nick Park, Peter Lord, and their colleagues at Aardman. At the time it was probably the most complete information one could get on these films. Of course, Aardman has gone on to make other films and TV series, but this was the studio’s golden age. On February 1, I described with two boxed sets dealing with early sound films in All singing! All dancing! All teaching! As the title implies, these are a boon to film teachers, as well as buffs and researchers. In Coming attractions, plus a retrospect (June 6), David discussed the release of Robert Reinert’s very peculiar silent film, Nerven, and in Summer show and tell (July 28, 2008), he briefly dealt with a miscellaneous set of DVDs and books that we discovered during our annual visit to Il Cinema Ritrovato and other destinations. On December 10, in Preserving two masters, I discussed the restored version of Lubitsch’s Das Weib des Pharao (which at that point wasn’t out on DVD) and a Walter Ruttmann set.

2009 was a pretty good year, too. On February 18, I wrote about the Flicker Alley release of Abel Gance’s influential classic La roue, including historical background on the film, in An old-fashioned, sentimental avant-garde film. David took the occasion of of a new Criterion boxed set to summarize the work of the fine Japanese director Shimizu Hiroshi (May 9). On May 21, in Forgotten but not gone: more archival gems on DVD, I described two major boxed sets, one of Lotte Reiniger’s lovely but seldom-seen fairy-tale shorts, and one of early Belgian avant-garde cinema–and yes, the early Belgian avant-garde cinema includes some important titles. On August 2, David again caught up with the mixed batch of DVDs and books picked up in Europe over the summer or sitting in the stack of mail upon his return, in Picks from the pile. Finally, on November 9 I discussed the British release of Dreyer’s Vampyr with a very worth-while commentary track by Guillermo del Toro, who said, among other things, “I am not Carl Dreyer, and I should shut up.”

In February of 2010, I wrote DVDs for these long winter evenings, dealing with three sets with the work of three crucial filmmakers: Georges Méliès, Ernst Lubitsch (most of the German features), and Dziga Vertov. In October, it was More revelations of film history on DVD: a documentary on Veit Harlan, a new series of Soviet silent films, and the Flicker Alley set of Chaplin’s Keystone films. (For the follow-up, see below.) On November 28, Silents nights: DVD stocking-stuffers for those long winter evenings covered little-known Norwegian and Danish silents, a rare Expressionist film, Ford’s The Iron Horse, hilarious Max Davidson comedies, and the Kalem company.

For some reason it was a full year before we posted more DVD coverage in our second Christmas-gift-themed entry, Classics on DVD and Blu-ray, in time for a fröliche Weihnachten! (November 29, 2012). It probably took us that long to get through all the discs we picked up in Bologna and elsewhere. The title reflects the heavily German coverage: early Asta Nielsen films, Pabst’s first feature, the release of Das Weib des Pharao on DVD and Blu-ray, as well as the 1939 Hollywood version of The Mikado.

Earlier this year, on June 20, we posted our most recent DVD/Blu-ray entry, Recovered, discovered, and restored: DVDs, Blu-rays, and a book. It deals with a burst of releases of Norwegian silent films, a new entry in the “American Treasures” archive series, and some American films, famous and obscure.

Now more DVDs are piling up, and the time seems ripe for a third set of holiday-present suggestions, to give or hope to receive.

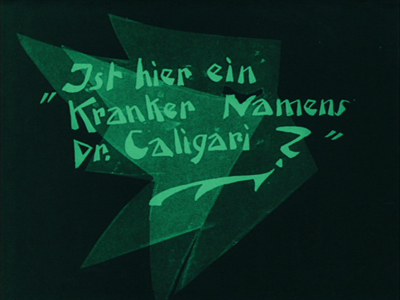

Caligari, restored at last

In our survey of the ten best films of 1920, I mentioned that Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari was one of the films that lured me into film studies during my undergraduate days. I know it very well. I was tempted to go to one of the screenings of the recent restoration this year at Il Cinema Ritrovato, but it was opposite other films I had never seen before, so I passed it up. Luckily now Kino Lorber has brought that restoration out on DVD and Blu-ray (sold separately).

The negative of Caligari does not survive in its entirety, but the restoration has taken the usual steps to fill it in and provide authentic tinting. The information comes from titles at the beginning of the DVD print:

The 4K restoration was created by the Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung in Wiesbaden from the original camera negative held at the Bundesarchiv-Filmarchiv in Berlin. The first reel of the camera negative is missing and was completed from different prints. Jump cuts and missing frames in 67 shots were completed by different prints.

A German distribution print is not existing. Basis for the colours were two nitrate prints from Latin America, which represent the earliest surviving prints. They are today at the Filmmuseum Düsseldorf and the Cineteca di Bologna.

The intertitles were resumed from the flashtitles in the camera negative and a 16mm print from 1935 from the Deutsche Kinematek-Museum für Film und Fernsehen in Berlin.

The digital image restoration was carried out by L’Immagine Ritrovata-Film Convservation and Restoration in Bologna.

The images are definitely clearer, with more detail visible than in prints I have seen before, and the film runs more smoothly. An inauthentic intertitle has been removed. In most prints, when the grumpy town clerk hears that Caligari wants a permit to exhibit a somnabulist, he calls him a “Fakir” and turns him over to his underlings to deal with. That title is now gone, and it’s clear that Caligari is annoyed at the man’s disdainful attitude rather than a specific insult. The intertitles have their original jagged, Expressionistic graphic design (see above) rather than the plain backgrounds used in many prints hitherto available.

There are optional English subtitles. The modernist musical track fits well with the film.

The supplements include a short essay which I provided and a documentary, Caligari: How Horror Came to the Cinema. The restoration is also available from Eureka! in the United Kingdom, with a different set of supplements and with DVD and Blu-ray sold together.

Flooded by flickers

If you want a lot of good laughs and have 1005 minutes to spare, Flicker Alley’s “The Mack Sennett Collection Volume One” offers 50 restored shorts which Sennett acted in, wrote, directed, and/or produced. (This 3-disc set is available only on Blu-ray.)

The films are presented in chronological order, starting with a 1909 comic short directed by D. W. Griffith at American Biograph and starring Sennett, The Curtain Pole. Two comedies directed by Sennett at American Biograph follow. In 1912 he founded Keystone, represented starting with The Water Nymph (1912) and ending with A Lover’s Lost Control (1915). In 1915 Sennett became one of the three points in the Triangle Film Corporation, along with co-founders Griffith and Thomas Ince. Keystone continued operating as Triangle Keystone, and films from that production unit from 1915 to 1917 are included. At that point Sennett went independent as Mack Sennett Comedies, making mainly two-reelers, beginning in this collection with Hearts and Flowers (1919) and running to The Fatal Glass of Beer (1933). See here for a complete list of titles. Each of the three discs contains a group of films as well as a set of bonuses at the end.

Sennett built a team of excellent comedians, including at various points Ben Turpin, Chester Conklin, Charlie Chaplin, Ford Sterling, Wallace Beery, Louise Fazenda, Mabel Normand, and others. The action typically moves at a breakneck pace, and the editing is similarly fast. Being able to go back and watch some of these routines again, perhaps in slow motion, is ideal for making sure you catch every throw-away gag.

A Clever Dummy shows off the dexterity of the cross-eyed Turpin. Two inventors build a mechanical dummy, modeling “him” on the janitor played by Turpin. At first the dummy is a rather cheap-looking fake, but Turpin plays him in some scenes and the janitor in others. Then he decides to masquerade as the dummy, and his antics persuade some vaudeville agents to buy him for their show (left below). Once in the theater, he defies a stagehand’s (Conklin) efforts to make him stand quietly (right):

Savor these a few at a time, and you’ll have entertainment for months to come.

Of course, some of that 1005-minute total comes in the bonuses. There are newsreel and television appearances by Sennett, including “This Is Your Life, Mack Sennett” (1954) and a half-hour radio appearance on the Texaco Star Theater in 1939.

Back in 2007, we posted an entry called Happy Birthday, Classical Cinema!, where we explained how the guidelines and techniques that came to underpin what we now call classical Hollywood cinema came together in 1917. At the end we offered a list of the ten best films of that year, and thus inadvertently our annual ninety-year celebration, “The ten best films of …” came into being. On it were two Charlie Chaplin films, The Immigrant and Easy Street.

They were both made during the third phase of Chaplin’s career, when he had left Keystone and gone first to Essanay and then to Mutual. Those who find the pathos in many of Chaplin’s films from the 1920s onward might plausibly consider his Mutual period to be the height of his career. The twelve films are not all equally brilliant, however. One watches Chaplin developing a better sense of story-telling to go with the slapstick. The Rink comes across as two one-reelers stitched together. In the first half having Charlie does a fairly conventional waiter schtick, but when he visits a rink on his lunch-hour, the films moves into high gear as he performs a dazzling set of moves on skates:

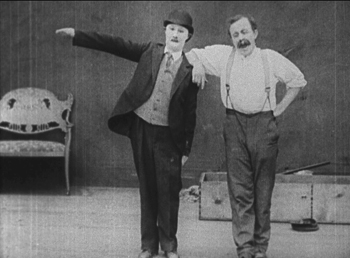

Other films show Chaplin learning to make a sustained, tight story built of non-stop gags, none more skillfully than The Cure. An alcoholic forced into a sanatorium evades all attempts to make him shape up while charmingly defending the heroine from an offensive, gout-ridden villain (see top, where all involved briefly strike a pose).

Flicker Alley has released a steelbox commemorative set of five discs, two Blu-ray and three DVD, to celebrate the centenary of Chaplin’s first appearance as the Little Tramp–though of course that appearance had been made at Keystone.

For a list of film titles and bonus features, see here.

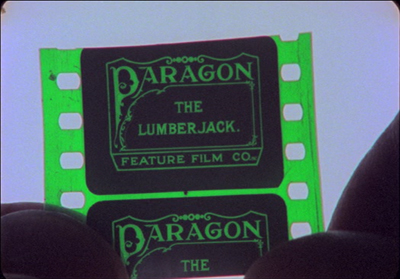

If these sets contain some of the most famous films and performers of their day, another recent Flicker Alley release, We’re in the Movies: Palace of Silents & Itinerant Filmmaking, turns to some of forgotten and obscure offerings of the silent era: films made in small towns by independent regional producers, using local citizens for their casts. Earlier this year, David wrote about Wheat and Tares, a 1915 film made in his home town by the Penn Yan Film Corporation. That’s not one of the locally made films included in We’re in the Movies, but this two-disc set (both DVD and Blu-ray) does contain The Lumberjack, a short film made in Wausau, Wisconsin and discovered in the early 1980s by Stephen Schaller, then a graduate student in film studies here at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Schaller didn’t just discover the film. He created a lovely, poignant documentary, When You wore a Tulip and I Wore a Big Red Rose (1983), about the making of the film and the history of the one print and how it survived. He tracked down and interviewed several elderly people who had been involved with its making. These included Florence Gilbert Evans, the only surviving cast member, and relatives and friends of others “actors.” At intervals throughout the film, he interviews Louise Elster, who had accompanied silent films on piano in local theaters. She provides a lively commentary on such accompaniments and plays examples as skillfully as she must have done in the day. (Modern-day silent-film accompanists might find many tips from this documentary.)

The only problem with the film is that no identifying titles are superimposed to tell us who these people are, and often their names are not mentioned in the interview excerpts included. One has to struggle at times to figure out who the speakers are and what they had to do with The Lumberjack. Names are only given in the final credits, and even then their connections to the film are not specified. Still, the story of the film’s making comes together clearly enough.

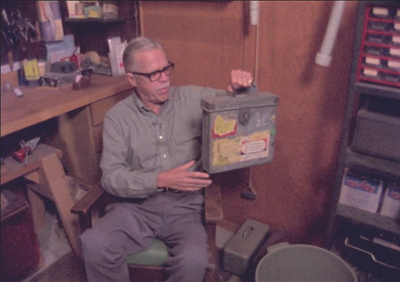

Schaller reenacts the finding of the film itself in a scene with Robert S. Hagge. Hagge, who apparently worked at the Grand Theater, where the sole print resided until 1946, when he took it to his home:

The poignancy of The Lumberjack‘s history emerges gradually as we get to know those involved and their histories. One of the producers was accidentally killed during a quarry explosion staged for the film. Settings shown in the movie are compared with the current appearances of the same places, with some beautiful old buildings preserved and others replaced by bland modern structures. There is a hint that the making of the film created an excitement that transformed the lives of the Wausau citizens involved. When You Wore a Tulip and I Wore a Big Red Rose illustrates the power of even the most modest of films and the inevitable losses caused by the passage of time.

The set also includes a 2010 documentary, Palace of Silents: The Silent Movie Theater in Los Angeles, devoted to a theater built in 1942 and dedicated for over 68 years to showing silent films. The rest of the contents are The Lumberjack and other early local films.

These films strike me as an excellent way of intriguing students and film fans about the silent era of the movies.

Oktoberfest as seen through the movies

I was somewhat surprised to see the new two-DVD set in the Filmmuseum München series: Oktoberfest München 1910-1980. It’s an interesting approach, gathering together the surviving films about a single annual event, Munich’s famous Oktoberfest. As the accompanying booklet points out, the Oktoberfest was a venue where early traveling exhibitors set up their tents to show movies, though little documentation of these shows survives. No one knows when the first films about or set at the festival were made. The earliest one to survive is from 1910.

Oktoberfest was and is more than beer-drinking. There are parades, rides, and various fairground activities as well.

To many film historians, one of the attractions of this collection will be a film starring the comedian Karl Valentin, Valentin auf der Festwiese. The nominal plot involves Valentin taking his wife to the festival while planning to meet his mistress there and sneak away. This story gets shunted aside for most of the film’s length, however, as the couple wander through various sideshow tents. We see their grotesque reflections in a fun-house mirror (above), and the camera perches in a ferris-wheel seat to record the long-delayed confrontation of wife and mistress.

One curiosity of the set is a 3D film from 1954, Plastischer Wies’n-Bummel. The analglyph 3D glasses (red and cyan) required for the effect are included in the set. I found it something of an effort to resolve the 3D in many shots, but there are some dramatic depth effects involving balloons and some fairground swings that work quite well:

The booklet is in German, English, and French, and there are optional subtitles in English and French. The DVD set can be ordered online here.

Making a list, Czeching it twice

When we were in Prague this summer, Michal Bregant, head of the National Film Archive, gave us some books and DVDs related to early Czech animation.

One was a catalog published by the archive, Czech Animated Film I 1920-1945 (2012, bilingual in Czech and English), with a short historical introduction and descriptions of all the known films of the period. It relates to a two-DVD set, Český animovaný film 1925-1945 (Czech animated film). This delightful collection contains 30 shorts and has optional English subtitles. Some of the cartoons are outright imitations of American series of the day, such as Hannibal in the Virgin Forest (1932), clearly inspired by early sound cartoons from Disney and Warner Bros.:

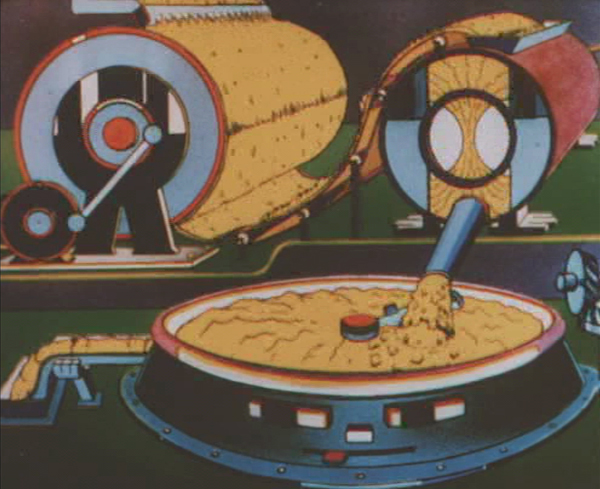

There are also two early György Pál (later aka George Pal) cartoons. Many of the shorts, though, are advertisements. As in other countries where major filmmakerss like Len Lye were doing inventive work for ads, Czech animators came up with some amazing images. Margarine never looked as good as in Irena and Karel Dodal’s 1937 Gasparcolour short for the Sana brand, The Unforgettable Poster (see bottom).

The Dodals were the most important Czech animators of this era, as is shown in a well-illustrated biography, The Dodals: Pioneers of Czech Animated Film, by Eva Strusková (published by the National Film Archive in 2013). It’s in English and comes with a DVD. (There is some overlap between its contents and those of the two-disc set.)

Both are musts for animation experts and fans. The Dodals is available from Amazon. The DVD set won as “Best Re-discovery 2012/13” at the Il Cinema Ritrovato awards last year. It and the catalog can be ordered directly from the National Film Archive website or from a specialized cinema shop in Prague, Terry Posters (this link takes you to the English-language version of the site).

The Unforgettable Poster (1937)

Adieu to Vancouver 2014

Jauja.

Kristin here:

The Vancouver International Film Festival ended this past Friday. I had hoped to post a wrap-up entry over the weekend, but illness intervened. Herewith a summary of several films I enjoyed this year.

Too clever by half

Some films are obviously and thoroughly pretentious. This year Field of Dogs (Lech Majewski, 2014) fell into that category. I had had high hopes for it, since I very much liked Majewski’s The Mill & the Cross at the 2011 festival. Unfortunately, it’s a completely different film, overcomplicated and, for me, nearly unwatchable.

Two film, however, suffered from a different problem. They had absorbing stories and interesting stylistic approaches. I enjoyed both very much–except for unwise additions, in each case unnecessary and annoying.

Stations of the Cross (Dietrich Bruggemann, Germany, 2014) revolves around Maria, an adolescent girl raised in a household where a strict, old-fashioned version of Catholicism is practiced. Bruggemann takes the not uncommon approach of filming each scene in one lengthy, and in most cases static, take. In the opening scene, a priest instructs a small class of children about to take First Communion. The camera is placed in a planimetric framing, a technique used in several shots in the film:

As the lesson continues, Maria, seated to the priest’s right, gradually emerges as the student most versed in the topics under discussion. She stays after the others leave and hints to the priest that she wants to sacrifice herself to earn a miracle for her four-year-old brother, who has never spoken. Her belief that she must deny herself virtually all pleasures, comforts, and even necessities, as well as her guilt over the slightest perceived infraction, become increasingly apparent across the narrative. Her arguments with her harsh and inconsistent mother, who dominates the family, reveal her suffering. Despite the static shots, the story is never boring, and a scathing indictment of this brand of religious extremism builds up.

The problem is that Bruggemann inserts chapter titles before each scene/shot, numbered and with the descriptions of the fourteen Stations of the Cross. This inevitably connects Maria’s sufferings to those of Jesus. Each scene contains some parallel, however tenuous, to the station that it is supposed to illustrate. I found this distracting and occasionally ludicrous, as when the title describing Christ’s being stripped of his clothing cuts to a shot of a partially undressed Maria seated on a doctor’s examining table. (Jay Weissberg’s review for Variety sees deliberate humor in the film, but as far as I could see, Bruggemann takes all this as deadly serious.) This could have been an excellent film without the insistence on allegory, but as it is, one must try to ignore the interruptions to focus on the story.

Something rather similar happens in Jauja (Lisandro Alonso, Argentina, 2014). Again there is an absorbing story, though a very different one. In nineteenth-century Patagonia, a Danish engineer is doing surveying work to help a military group determined to wipe out the indigenous population. When his daughter runs off into the forbidding desert with a young soldier, the engineer follows on his own and experiences a series of increasingly disturbing and mystifying incidents, including some that could be classed as magical realism.

This is fascinating stuff, and in the print we saw, the beautifully composed landscape shots (almost the entire film takes place out of doors) were presented in a masked format reminiscent of old lantern slides or stereoscope images (see top, the opening one-shot, long-take scene). Most of the images from this film on the internet are in a more conventional 1:66 ratio, but the masked version seems far superior. One can only hope that the video release preserves it.

It’s a lovely, evocative, disturbing film, but just as we see a shot of the protagonist disappearing into a valley in a bleak landscape of black volcanic rocks, there is a cut to an epilogue set in a beautiful Danish castle. The daughter wakes up and goes for a walk with some dogs. End of film. How this is supposed to relate to the preceding story is a mystery, and one which thoroughly undercuts the tension slowly built up over the course of the Patagonian-set story. The scene of the hero disappearing would have made a fitting ending, leaving the solution to the tale’s mysteries open-ended.

I note from a recent story in Variety that Alonso has been chosen as the second filmmaker to be hosted in the Film Society of Lincoln Center’s new “Filmmaker in Residence” program. That’s good news, I think, but I hope Alonso will trust more in his story-telling ability and less in flashy tactics like this pointless epilogue.

Brief notices

One director who displays such trust is Alejandro Fernández Almendras, whose Chilean revenge tale To Kill a Man (2014) is both entertaining and morally and psychologically complex. We are almost entirely confined to the presence and knowledge of Jorge, a forest ranger who has grown accustomed to the casual violence in the neighborhood where he lives. He tries to avoid trouble, but his family is increasingly harassed by Kalule, a loathsome petty gang leader. As Jorge is mugged, his son is shot and then wrongfully imprisoned, and his house pelted with stones and threatening messages, he doggedly insists on going through the police, while his wife becomes increasingly frustrated with their lack of response.

Finally, after Jorge’s daughter is assaulted and nearly raped, he decides to act and sets out to eliminate Kalule. The film then follows his patient, careful planning, culminating in an understated but riveting long take of the truck in which Jorge has his victim trapped as he systematically sets up the mechanics of the killing. The death itself is not shown:

Hitchcock has said that in making Torn Curtain‘s big fight scene in the farmhouse, he wanted to show just how physically difficult it is to kill someone–as opposed to the seemingly effortless killings that fill American genre films. Almendras’ film is almost entirely about how difficult it is in all ways. Jorge takes a long time making his fateful decision, in executing it, in dealing with the body and evidence, and in living with what he has done. Most spectators, attuned to more conventional revenge plots and frustrated by Jorge’s initial resignation in the face of intolerable injustice, are probably cheering him on from an early point in the plot. But, as Almendras thoroughly shows us, it just isn’t that easy.

Charlie’s Country (Rolf De Heer, 2013) also centers very tightly on a protagonist beset by difficulties, but it sets a very different tone. It’s another Australian film focusing on aborigines and their problems under the rule of the white majority. Charlie is a genial elderly man living in impoverished circumstances in a village set aside for aborigines and run by local police. Their laws mystify him. His gun is taken because he cannot afford a license, and when he fashions a spear for hunting for food, it is taken away and destroyed as a dangerous weapon.

His health declines so far that the authorities send him to a hospital in a city far from his home, an apparent signal that he is dying. Instead, he escapes, lives with some street people, and finally makes his way home.

The film is entertaining enough, though it deals with familiar subject matter. It exists, though, primarily as a love letter to David Gulpilil, the most successful Australian aboriginal actor. His first film is also one of his best-known outside Australia, Walkabout, which I saw when it first came out, just after I had gotten my BA and was about to commence film-studies as a graduate student. (It’s a bit disconcerting to watch him playing an old man here and realizing that he is three years younger than me!) Gulpilil turns in an endearing performance that pretty much carries the movie.

I enjoyed and was impressed by Russian director Andrei Zvyagintsky’s Leviathan (2014), though I’m not sure it quite lives up to all the hype following its debut in competition at Cannes, where it won best screenplay. The story centers around the owner of a sprawling, dilapidated garage in a declining fishing port on Russia’s northwestern coast. He struggles to prevent a corrupt local mayor from appropriating his property illegally. (The hypocritical official wants to use the land to build a church to further his own reputation.) At the same time, the protagonist has remarried, and he must deal with his teenage son’s reluctance to accept a young stepmother.

The depiction of modern Russian society in the provinces is a grim one, albeit one displayed in sweeping landscape shots that suggest the waste of this stunning region. Many scenes involve the characters putting away great quantities of vodka. These include a hilarious set-piece in which the family and friends drive into the countryside for a drunken picnic complete with a shooting competition using portraits of historical Soviet leaders as targets.

Leviathan will be released in the USA by Sony Pictures Classics on December 31.

Papusza (Joanna Kos-Kralize and Krzysztof Kralize, 2013) is the second new black-and-white Polish film I’ve seen this year. The first was the much-heralded Ida (Pawel Pawlikowski, 2013), an austere tale of a young woman in the 1960s, about to take her vows as a nun when she learns that she comes from a Jewish family persecuted during World War I. Papusza is a more easily engaging film, with a relatively fast-moving historical drama set among Poland’s Roma (“gypsy”) population.

Papusza centers around Bronislawa Wajs, the first Roma woman to learn to read and write; she became a well-known poet nicknamed Papusza. The film adeptly balances sympathy for the Roma group at the center of the story, the victims of racial prejudice, with a clear-eyed depiction of the less savory aspects of Roma culture. Girls, kept ignorant and oppressed, are married off at a young age. The Roma society practices its own prejudices, rejecting any interactions with people outside their clan and treating non-Roma as fair game to be fleeced at any opportunity.

The lively culture of the Roma and their closeness to nature are shown in impressive landscape scenes, as in shots of the caravans on the move through bucolic countrysides or when the band sets up a camp and market outside a traditional church (below).

As of now there is no indication that the film will receive an American release. The only DVD available seems to be the Polish one, with no optional subtitles. Various small streaming services claim to be offering it, but again, possibly without subtitles and in some cases with timings that don’t correspond to the original 131 minutes.

And so another year at Vancouver has ended. As usual, we are left with the feeling that this event is one of the most pleasant ways to catch up with a huge amount of what is happening in world cinema.

Papusza

What’s left to discover today? Plenty.

Der Tunnel (William Wauer, 1915).

DB here:

Being a cinephile is partly about making discoveries. True, one person’s discovery is another’s war horse. But nobody has seen everything, so you can always hope to find something fresh. There’s also the inviting prospect of introducing a little-known film to a wider community–students in a course, an audience at a festival, readers of a blog.

A festival like Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato (we covered this year’s edition here and here and here) offers what you might call curated discoveries. Expert programmers dig out treasures they want to give wider exposure. Such festivals are both efficient–you’re likely to find many new things in a short span–and contagiously exciting, because other movie lovers are alongside you to talk about what you’re seeing.

A year-round regimen of curated discoveries is a large part of the mission of the world’s cinematheques. This is why places like MoMA, LACMA, MoMI, BAM, TIFF, ICA, and other acronymically identified showcases are precious shrines to serious moviegoing.

But other discoveries are made in a more solitary way. Film researchers, for instance, ask questions, and some of those can really only be answered by visiting film archives. Sometimes we need to look at fairly obscure movies. And despite the rise of home video, there are plenty of obscure movies that can be seen only in archives. It’s here that the programmers of Ritrovato and Pordenone’s Giornate del Cinema Muto come to select their featured programs.

Archive discoveries aren’t predictable, and many are likely to be of interest only to specialists. Such was the case, mostly, with our archive visits this summer. But as in years past (tagged here), all our archive adventures yielded pure happiness.

This time I concentrated on films from the 1910s-early 1920s films because I hope to make more video lectures about this, the most crucial phase of film history. (One lecture is already here.) In our archive-hopping, we saw films I was completely unfamiliar with. I re-watched some films I’d seen before and found new things in them. I detected some things of interest in films I hadn’t known. Most exciting was our viewing of a major film that has gone unnoticed in standard film histories.

In the steps of Jakobson and Mukarovský

Love Is Torment ( Vladimír Slavínský, Přemysl Pražský, 1920); production still.

First stop was Prague, where I was invited to give two talks. At the NFA we saw two films on a flatbed: a portion of Feuillade’s Le Fils du Filibustier (1922) and a cut-down version of Volkoff’s La Maison du mystere (1922), the latter a big gap in our viewing. The expurgated Maison came off as rather drab, lacking nearly all the big moments much discussed in reports like James Quandt’s from a decade ago. So we search on for the full version. . . .

As for the Feuillade: Le Fils du Filibustier was his last “ciné-roman.” Our two-reel segment, which seemed fairly complete, confirmed his late-life switch to fairly fast, Hollywood-style editing, with surprisingly varied angles.Again, though, we yearn to see the entirety of this pirate saga.

On another day the archive kindly screened several 1910s-early 1920s Czech films for us. Our hosts Lucie Česálková and Radomir Kokes translated the titles and provided contexts. Among the choices were Devil Girl (Certisko, 1918), with a protagonist who’s more of a tomboy than a possessed soul; and the full-bore melodrama Love Is Torment (Láska je utrpením, 1919). The plot, outlined here, involves scaling and jumping off a tower, twice. Once it’s a stunt for a film within the film, the second time (below) it’s the real thing.

Radomir explained to us that one of the co-directors, Vladimír Slavínský, seemed in his 1920s films to specialize in building two reels (often the third and fourth) in a “classical” fashion before letting the other three become more episodic. And indeed, most of the late 1910s-early 1920s films we saw were up to speed with other European filmmaking, in their staging, cutting, and use of intertitles.

We look forward to viewing more Czech films as the opportunity arises. A culture that gave us Prague Structuralism is definitely worth getting to know better. In the meantime, the journal Illuminace, edited by Lucie, is injecting a great deal of energy into local film studies, and the archive is entering a fresh phase with its new director, Michal Bregant.

3D excavations

Der Hund von Baskerville (1914).

In Munich, we reconnected with our old friends Andreas Rost, now retired from administering the city’s cultural affairs, and Stefan Drössler, director of the Munich Filmmuseum. We also reunited with the stalwart archivists Klaus Volkmer, Gerhard Ullmann, and Christoph Michel. Talking with them, we realized we hadn’t been back for over ten years. Klaus and Gerhard were warm and helpful during our earlier visits.

One rainy afternoon, Stefan shared his research on the history of 3D. He presented a spectacular PowerPoint, with rare images and some truly startling revelations. He has given this talk at intervals over the years, but it grows and deepens as he discovers more. Accompanying it, he screened some Soviet 3D films, including the 1946 Robinzon Cruzo. This mind-bending item was made with diptych images, so that the projected image turned out to be slightly vertical. The soundtrack runs down the middle.

The director, Aleksandr Andriyevsky, made excellent use of 3D to evoke the stringy vines and protruding leaves of Crusoe’s island. Amid all the talk today about glasses-free 3D, it’s interesting to learn that Soviet researchers prepared such a system. Stefan’s archaeology of 3D, for me at least, was a pretty big discovery.

At Munich we also saw three silent German titles. Two were associated that resourceful self-promoter Richard Oswald. Sein eigner Morder was a 1914 version of Dr. Jekyll and Mr Hyde, directed by Max Mack from Oswald’s screenplay. Shot in big sets, it spared time for the occasional huge close-up. The other film was Oswald’s semi-comic adaptation of The Hound of the Baskervilles (Der Hund von Baskerville, dir. Rudolf Meinert, 1914), which he had already turned into a play. The sleuth isn’t exactly our idea of Holmes (see above), and he isn’t as quick-witted, I thought, but it was an enjoyable item. Dr. Watson has a sort of tablet which picks up messages; Holmes’ orders are spelled out in lights on a grid. Stefan rightly called it a 1914 laptop.

As for the third film: More about that coming up.

The shadow of Hollywood

Les Deux gamines (1921).

At Brussels, thanks to the cooperation of the Cinematek, I was able to see several items for the first time, and two held considerable interest. The short The Meeting (1917), by John Robertson, showed a real flexibility in laying out the space of a cabin both in front of the camera and behind it. Most interior scenes in 1900-1915 cinema bring characters in from a doorway in the rear of the set (as Feuillade does in his 1910s films) or straight in from the sides, perpendicular to the camera (as Griffith tends to do). The Meeting shows that the diagonal screen exits and entrances that we see in exteriors were coming into use in interior sets as well.

Another 1917 film, Frank Lloyd’s A Tale of Two Cities, was further support for the idea that American continuity filmmaking was well-established and already being refined at the period. Dickens’ classic tale is handled with dispatch–rapid exposition, smooth crosscutting to set up the plot lines–and the film makes dynamic use of crowds surging through well-composed, starkly lit frames. There are also some remarkably expressive close-ups, evidently made with wide-angle lenses.

To clinch a plot point, the resemblance of aristocrat Charles Darnay to British solicitor Sydney Carton, the star William Farnum plays both characters. Not much of a problem if you keep the characters in separate shots; the good old Kuleshov effect (aka known as constructive editing) makes it easy. At this period, though, filmmakers were perfecting ways to show one actor in two roles within a single shot. The most famous examples involve Paul Wegener in The Student of Prague (1913) and Mary Pickford in Stella Maris (1918).

Cinematographer George Schneiderman contrives some really convincing multiple-exposures showing Farnum as both Darnay and Carton. There are some standard trick compositions putting Farnum on each side of the screen, but several images take the next step and let the actor cross the invisible line separating the two halves. At another point, we get a flashy passage showing the two facing one another in court, followed by a “Wellesian” angle of the two characters’ heads in the same frame.

Hollywood’s pride in photorealistic special effects, so overwhelmingly apparent today, has deep roots.

Part of my Brussels visit involved checking and fleshing out notes on certain films I saw many years ago. Some were wonderful William S. Hart movies like Keno Bates, Liar (1915; surely one of the best film titles ever). There was, inevitably, Feuillade as well. The influence of Hollywood was powerful in the ciné-roman Les Deux gamines (1921). This baby, released in 12 parts originally, runs nearly 27,000 feet. At 20 frames per second, it would take six hours to screen. What with changing reels, making notes, counting shots, pausing to study things, and taking stills, Kristin and I took about ten hours to watch it.

Was it worth it? An adaptation of a popular stage melodrama, it can’t count as one of Feuillade’s major achievements. Two girls are left alone when their mother is reported dead. They are adopted by their gloomy grandpa and tormented by his overbearing housekeeper. They become the target of kidnapping by gangster pals of their father, who has divorced their mother and turned to a life of petty crime. Their allies are their young cousins, a wealthy benefactor, and their godfather and music-hall star Chambertin. Everything ends happily, if you count the father’s redemptive sacrifice on behalf of a pregnant woman.

Les Deux Gamines is determined to delay its ending by any means necessary. Form here definitely follows format; Feuillade fills out the serial structure with plots big and small. (Shklovsky would love it.) There are incessant abductions, escapes, rescues, coincidental meetings, and timely reformations, plus at least three cases of people wrongly assumed to be dead. All of this is accompanied by an endless exchange of telegrams and letters. People are forever piling into and out of carriages, train cars, and taxis. Such material serves as makeweight for some genuinely big moments, including a cliff-hanging scene and a stunning climax in a smuggler’s warehouse stuffed with gigantic bales of used clothing.

Like Le Fils du Filibustier, this film shows Feuillade trying to change with the times. The supple long-take staging of Fantômas and Les Vampires and Tih-Minh mostly goes away, to be replaced by rapid editing. Feuillade employs standard continuity devices, as when the grandfather discovers that the kids have sneaked out at night and are trying to return by scaling the gate.

Feuillade varies his angles and lighting to accentuate the moment of visual discovery. Elsewhere, some appeals to “offscreen sound” (cutaways to doorbells and telephones) built up to a surprise effect.

But by the energetic standards of, say, Robertson or Lloyd several years earlier, Les Deux gamines is fairly timid. Feuillade doesn’t explore editing resources very much here, not even as much as in Le Fils du Filibustier. The fairly quick cutting pace stems partly from the stratagem of having dialogue titles interrupt static two-shots of characters talking to one another. This sort of proto-talkie-technique yields efficient storytelling but not much visual momentum. Feuillade tried flashier things in other films of the period (see here).

Hours and hours of nothing but Bauers

The Alarm (1917).

Yevgeni Bauer, one of the master directors of the 1910s, remains lamentably unknown. About two dozen of his over seventy films survive, but many of the ones we have lack intertitles. A few of his films are available on DVD (most obviously here; less obviously here). He died of penumonia in 1917, between the February revolution and the Soviets’ coup d’état in October. He was only 52.

My first archive-report entry back in 2007 recorded my interest in Bauer, and I’ve returned to his films over the years. Now here I was watching some again, confirming things I found of interest then, and discovering (that word again) new felicities. I hope to say more in those short video lectures on the 1910s, but I can’t leave without giving you a taste of his qualities.

Two of the films I saw this time were from 1917. The Alarm (Nabat) came out in May 1917, just before Bauer’s death in June. Originally running eight reels, it was cut down after the initial release, and that’s evidently the version we have. For Luck (Za Schast’em, September 1917) was directed by Bauer from his sickbed. Both films are fairly hard to follow. The Alarm lacks intertitles, and For Luck has many fewer than it had originally.

The two films are of exceptional interest, though. For one thing, there’s the involvement of Lev Kuleshow, who at the age of eighteen served as art director for the earlier film and, apparently reluctantly, as an actor in the later one. More important, the films remain as beautifully designed, staged, and acted as ever.

The Alarm is a wide-ranging drama set before the February upheaval. The drama involves romantic intrigues among the upper class, interwoven with a workers’ rebellion against a master capitalist. The millionaire Zeleznov holds court in a vast office with chairs bearing ominous spires and spiky arches; the windows open onto a view of his factory. A long-shot view is above; here’s a sample of how Bauer shows off his decor in something akin to shot/ reverse-shot.

The idea of capitalism as an overreaching religious striving is evoked by turning Zeleznov’s headquarters into a Symbolist cathedral. And looking at the second shot, you wonder whether Kuleshov’s inclination to stage his own scenes against pure black backgrounds has its source in his work for the man he called “my favorite director and teacher.”

As ever, Bauer makes fluid use of depth. He choreographs meetings of Zeleznov’s brain trust in ever-changing arrangements, and he eases a man out of a boudoir through a mirror reflection over a woman’s fur-draped shoulder.

Compared to the scale of The Alarm, For Luck is decidedly low-key–a bourgeois melodrama that extends barely beyond an anecdote. Zoya has been a widow for ten years, and she hopes to marry the loyal family friend Dmitri. But Zoya’s daughter Lee hasn’t yet reconciled to losing her father. The couple hope that Lee has worked out her grief during her dalliance with a young painter (played by Kuleshov), but she reveals that all along she has hoped to marry Dmitri.

The Alarm used some extravagant sets, both for interior and exterior scenes, but a good deal of For Luck takes place in parks and terraces. The sincere Enrico sketches Lee in front of swans, and they steal some moments in a bower.

Still, there are some interiors boasting Bauer’s famous pillars and columns, which create massive, encapsulated spaces. Here Zoya looks off, in depth, at the ailing Lee, in bed on the far right.

Sharp-eyed Bauerians will notice the mirror set into the left wall, reflecting Zoya. Kuleshov, who did art direction on this as well as The Alarm, worried more about the trumpet-blowing Cupid floating between the pillars on the left. (“It turned out bad on the screen–incomprehensible and inexpressive.”) He did think that the tonalities of the set worked well: “As an experiment, I put up a set painted in shades of white that were ever so slightly different from one another.”

“Ever so slightly different” isn’t a bad evocation of the tiny variations of shape and shade, light and texture, that characterize Bauer’s ripe, sometimes overripe, imagery. This is a social class on the way out, but it leaves behind a great glow.

Tunnel: Vision

The Tunnel (1915).

In 1913, the popular novelist Bernhard Kellermann published Der Tunnel. It’s not quite science-fiction, more a prophetic fiction or realist fantasy in the vein of Things to Come. The book became a best-seller and the basis of a 1915 film directed by William Wauer.

The plot would gladden the heart of Ayn Rand. A visionary engineer persuades investors to fund building an undersea railway connecting France to the United States (specifically, New Jersey). No meddling government gets in the way of this titanic effort of will. Max Allan buys land for the stations, hires diggers from around the world, and risks everything he has. The obstacles are many. An explosion scares off workers; there is a strike; impatient stockholders raid and burn the company headquarters.

Max Allan moves forward undeterred, though he hesitates when his wife and child are stoned to death by a mob. After twenty-six years, the railway is opened. Max, along with his new wife (the daughter of his chief backer), proves it’s safe by taking the first transatlantic train. The event is covered by television, projected on big screens around the world (above). In the original novel, a film company was commissioned to document every stage of work.

The book skimps on characterization, and the film is even less concerned with psychology. Once the character relations are sketched, Wauer goes for shock and awe. The Tunnel‘s thrilling crowd scenes of work, fire, devastation, riots, and panic look completely modern. Bird’s-eye views of stock-market frenzy anticipate Pudovkin’s End of St. Petersburg, and Wauer creates an Eisensteinian percussion of light and rushing movement as workers flee the tunnel collapse.

For the sequences showing the tunnel construction, Wauer supplies violent alternations of bright and dark as men, stripped and sweaty, attack the rock face. The variety of camera positions and illumination is really impressive.

Comparisons with The Big Film of 1915 are inevitable. The intimate scenes of The Tunnel are far less delicately realized than the romance and family life of The Birth of a Nation, and the battle scenes in Birth have a greater scope than what Wauer summons up. But Wauer’s handling of crowds is more vigorous than Griffith’s riots at the climax of Birth, and his pictorial sense is in some ways more refined, even “modern.” There’s little in Birth as daringly composed as the static long shot surmounting today’s entry.

Wauer can handle small-scale action very crisply. The opening scene in an opera house creates low-angled depth compositions more arresting than Griffith’s depiction of Ford’s Theatre. Max’s wife, in one box, is watching his efforts to attract funding from the millionaire Lloyd. Wauer constantly varies his camera setups to highlight Max’s wife in the background studying Lloyd’s daughter, sensing in her a rival for her husband. Whether the angle is high or low, the wife’s presence in her distant box is signaled at the top of the frame.

The second and third shots above present similar but not identical setups, adjusted to reset the depth composition.

It was at Munich’s Filmmuseum a decade ago that I first encountered the brooding power of Robert Reinert’s Opium (1919) and Nerven (1919), the latter now available on DVD. I was convinced that Nerven was as important, and in some ways more innovative, than the venerated Caligari. Now the conviction grows on me that in The Tunnel we have another galvanizing, outlandish masterwork of the 1910s. I hope it will somehow get circulated so that wider audiences can discover it. Yeah, that’s the word I want: discover.

Without archivists, no archives. We’re grateful to Michal Bregant, head of the Czech Republic’s archive, for access to films and for his companionship during our visit. Thanks as well to Lucie Česálková, our host; her knowledgable colleague Radomir Kokes (who kindly corrected the initial version of this post); Petra Dominkova, our Czech translator; and Vaclav Kofron, editor of the Czech versions of our books. Lucie supplied the frame enlargement from Love Is Torment. As well: Good luck to the Kino Světozor!

In Munich, we owe a huge debt to archive chief Stefan Drössler, for his generous sharing of information and his and Klaus Volkmer’s rehabilitation of The Tunnel. Stefan also provided the images from Robinson Crusoe and The Hound of the Baskervilles. Coming up is his work for the annual Bonn International Silent Film Festival, 7-17 August. Thanks as well to Gerhard Ullmann and Christoph Michel.

In Brussels, as ever, the Cinematek has made us welcome, and we thank archive director and long-time friend Nicola Mazzanti and vault supervisor Francis Malfliet. Over the last thirty years, a great deal of our research has depended upon the cooperation the Cinematek leadership: Jacques Ledoux, Gabrielle Claes, and now Nicola.

My quotations from Kuleshov come from Silent Witnesses: Early Russian Films, 1908-1919, ed. Yuri Tsivian and Paolo Cherchi Usai (Pordenone: Giornate del Cinema Muto, 1990), 388-390.

There’s a chapter on Feuillade in my Figures Traced in Light, where Bauer is discussed as well. My essay on Robert Reinert is in Poetics of Cinema.

Thanks to Antti Alanen for correction of a misspelled title. Speaking of discoveries, you’ll find plenty on his wonderful Film Diary site. During his recent trip to Paris, he’s writing about art exhibitions, Dominique Paini’s Langlois exposition at the Cinémathèque, and Godard’s Adieu au langage.

Screening at the Czech Republic’s National Film Archive. From left: Michal Večeřa, Tomáš Lebeda, Radomir Kokes, Lucie Česálková, and Kristin.

Addio Bologna 2014

Okoto and Sasuke (1935).

DB here:

Some final notes on this year’s Cinema Ritrovato. Kristin has more when I’ve finished.

Poland, very wide

The First Day of Freedom (1964); production still.

Revisiting a couple of the Polish widescreen classics Kristin mentioned earlier, I’d just add that The First Day of Freedom struck me as merging that heaviness often ascribed to Polish cinema with casual shock effects, as much visual as dramatic. It’s not just the opening shot, with the camera descending implacably to reveal layers of activity in a POW camp before settling on barbed wire in the foreground, made as big as the chains on an ocean liner’s anchor. A symmetrical vertical lift ends the film, rising through floors of a nearly destroyed church tower, revealing a half-shattered Madonna and a looming bell, to float back up to the sky.

As in Wajda’s Ashes and Diamonds, gunfire not only cuts you down but sets you on fire. A Nazi dead-ender, holed up in the steeple and dying from his wounds, orders his girlfriend (“Whore!”) to take over his machine-gun nest. Since she’s been raped by wandering refugees early in the film, she has every reason to fire on the Poles, which she does with animal abandon. A Polish bullet cuts short her shooting spree, and then the camera launches on its remorseless movement heavenward. The primal force of this movie, especially the climax, suggests that Alexander Ford and Samuel Fuller have more in common than I’d suspected.

Kristin pointed out the efforts of Lenin in Poland (1965) to humanize the Great Man, and indeed there are many charming scenes showing him sliding down a banister, taking innocent walks with a Polish maiden, and generally being avuncular. But Sergei Yutkevich also doesn’t spare us the enraged Lenin, ranting in his cell when he learns of mistakes in party strategy. We also get a bit of the puritanical leader. He goes to the cinema for reportage on the political-military situation but walks out when a stupid melodrama comes on. To be fair, though, he does stick around to enjoy a comic short, Le cochon danseur (1907), with a lady cavorting with a man-sized pig. But the ex- (or maybe not so ex-) formalist Yutkevich recycles this image in a return to 1920s montage, when the pig shot reappears in a newsreel sequence showing the march to war.

Kristin pointed out the efforts of Lenin in Poland (1965) to humanize the Great Man, and indeed there are many charming scenes showing him sliding down a banister, taking innocent walks with a Polish maiden, and generally being avuncular. But Sergei Yutkevich also doesn’t spare us the enraged Lenin, ranting in his cell when he learns of mistakes in party strategy. We also get a bit of the puritanical leader. He goes to the cinema for reportage on the political-military situation but walks out when a stupid melodrama comes on. To be fair, though, he does stick around to enjoy a comic short, Le cochon danseur (1907), with a lady cavorting with a man-sized pig. But the ex- (or maybe not so ex-) formalist Yutkevich recycles this image in a return to 1920s montage, when the pig shot reappears in a newsreel sequence showing the march to war.

Yutkevich seems to be keeping up with the Young Cinemas of his day. The film is plotted as a series of flashbacks, alternating the present (Lenin in prison) with pieces of the past, sometimes out of chronological order. He imagines himself striding across a battlefield, conveyed by him walking in place against a blatant back-projection. Late in the film, newsreel footage gets stretched and distorted to fill the ‘Scope format, as in Truffaut’s Jules et Jim (1962). The experimentation with the soundtrack seems likewise rather modern. The noises are filtered nearly as strictly as in Miguel Gomes’ Tabu, so that sometimes we hear only Lenin’s footsteps in a city street.

Lenin not only narrates the film but “quotes” the whole dialogue of the scenes; we never hear any voice but his. Reminiscent of passages of The Power and the Glory (1933) and the entirety of Guitry’s Roman d’un Tricheur (1936), this device blankets the movie with Lenin’s thoughts, feelings, and political analyses. It’s scarily evocative of that booming voice-over narrator that Soviet cinema imposed on imported films. Denied subtitles and dubbing, audiences were obliged to listen to an impersonal voice drowning out the actors with its sovereign interpretation of the action. I wouldn’t put it past Yutkevich to be slyly alluding to this Orwellian voice of authority.

1914 fashionistas and 1940s fakers

Maison Fifi (1914).

For sheer dirty fun I have to recommend Maison Fifi by Viggo Larsen, a Danish director working in Germany. Here situation comedy meets notably horizontal sight gags. A young couturier cozies up to the officers stationed in her town, hoping that their wives will buy her wares. Her first encounter takes place outside the officers’ quarters, as each man, from private up to general, spots her and starts to flirt before being ordered aside by a higher-up. Part of the humor comes from the strict adherence to the table of ranks, part from the fact that each dislodged officer enjoys watching his superior get taken down.

Later, on a lark, some officers swipe one of Fifi’s dummies and take it to a tavern. When their wives surprise them there, they stow the mannequin in a distant phone booth. As they expostulate with their wives in the foreground, the dummy sits unmoving in the window of the booth far on frame right. Meanwhile, increasingly annoyed customers line up outside the booth. The dummy is more visible in projection than in my still, but Larsen also obliges with a cut-in.

In a very logical reversal, Fifi is at the climax caught in a boudoir and must pretend to be one of her own mannequins. This affords the officers an excellent pretext to undress her. Today the scene yields a vivid sense of the hooks, buttons, and stays that women, and men, of 1914 had to contend with.

Faked identity was a motif of the festival’s Hitler strand. The Strange Death of Adolf Hitler (1943) centers on a man with a knack for mimicking his Fuhrer and accidentally becomes his double. In a series of twists, both he and others try to kill the original, but confusion ensues and leads to a very downbeat ending.

The same premise gets a different workout in The Magic Face (1951), a film as puzzling as its title. Luther Adler delivers a performance at once peculiar and virtuoso. A stage impersonator’s wife is stolen away from him by Hitler. Escaping from prison, he decides to get his vengeance by posing as a servant and gaining access to the dictator. He kills Hitler and takes over his identity. Thereafter he cunningly fouls up the prosecution of the war by an ill-timed invasion of Russia, etc. His general staff are baffled and even try to kill him, but he represses all resistance.

The weirdness of this speaks for itself. In addition, the film doesn’t explain how Hitler’s new mistress fails to realize that her paramour has been replaced by her husband. Perhaps more striking, we wonder whether the impersonator might have taken a little trouble to alter other Nazi policies, e.g., the Final Solution. No less odd is the frame story, narrated by celebrated war correspondent William L. Shirer. There he maintains that this account was relayed to him by the wayward wife, who survived the fire in Hitler’s bunker. An independent production directed by Frank Tuttle (recently under HUAC pressure for his Communist affiliations), The Magic Face was judged by Variety to provide “a dramatic and suspenseful story which would have had far greater audience impact five or more years ago.”

Talking, in and out of sleep

The Bride Talks in Her Sleep (Hanayome no negoto, 1933); production still.

The Japanese cinema of the 1930s through the 1960s has been one of the very greatest national film traditions. I once characterized it as the Western cinephile’s dream cinema: a relentlessly commercial industry that has given us dozens of indisputable masterworks. Yet it seems that every few years it’s necessary to remind western publics of this nation’s titanic accomplishments. Packages circulated by the Japan Film Library Council in the 1970s have been followed by retrospectives and one-off touring programs at rather long intervals; the Mizoguchi series is a recent example.

Another effort to draw Japanese cinema to the spotlight, “Japan Speaks Out!” has become a high point of Cinema Ritrovato over the last three years. Curators Alexander Jacoby and Johan Nordström deserve credit for assembling new prints of early talkies, grouped by studio. As in previous years, some of the titles were familiar to specialists, and a few to generalists (Ozu’s The Only Son being this year’s example). But there have been several new discoveries, and the Ritrovato audience has responded enthusiastically. This year the films were screened twice, often to jam-packed halls. The sessions were introduced with brevity and point by Alexander, Johan, and Tochigi Akira of the National Film Center of Tokyo.

This year’s batch focused on the Shochiku studio, more or less the MGM of Japan. Shochiku enjoyed financial stability because of its theatre holdings (both cinemas and live-performance venues) and its address to a modernizing, western-leaning urban audience. Its policies, overseen by Kido Shiro, aimed to provide movies mixing tears and laughter. Kido urged that Shochiku comedy have a melancholy cast, and that Shochiku melodrama indulge in lighter moments. This blend is familiar to us in Ozu’s 1930s works; even as sad a film as The Only Son displays a comic side when the mother falls asleep during a German talkie.

Perhaps the purest example of Kido-ism in this year’s package was one of Shimazu Yasujiro’s best films, Our Neighbor Miss Yae (Tonari no Yae-chan, 1934). Two brothers are introduced practicing baseball, and soon we learn that one has considerable affection for the girl next door. The neighboring families are thrown into quiet turmoil when Yaeko’s sister returns home, having left her husband.

Stylistically, Shimazu is less rigorous than either Ozu or Shimizu Hiroshi, but he is very skilful. Our Neighbor Miss Yae has the real Kido flavor, mixing comedy and drama and throwing in cinephile references that the studio’s young directors enjoyed: one boy is compared to Fredric March, the young people watch a cartoon featuring Betty Boop and Koko the Clown. Just as important, Shimazu enjoys throwing in a stylistic flourish every now and again–a striking, even eccentric shot that arrests our attention. As the four young people are eating in a restaurant, a very straightforward shot of them gives way to a bold composition full of peekaboo apertures. The shot enlivens the fairly routine act of waitresses delivering food; at the end, one pair stands and switches positions.

Not all Shochiku films displayed a mixed tone; we saw some fairly pure comedies and melodramas. Three self-consciously modern films showed an amused, slightly sexy concern with young marriage. Happy Times (Ureshii koro, 1933) by Nomura Hiromasa, begins with a pair of teenage boys practicing pitching and catching to the strains of “There’s No Place Like Home.” Soon they’re spying on newlyweds who are so infatuated with one another that the husband skips work to stay at home and lounge around. He’s mocked by his fellow employees and upbraided by his boss, but his wife is relentless in her sweet-talking ways. The marital bliss is disrupted by an obstreperous visiting uncle, and the couple must turn to one of the man’s old girlfriends, a tough singing teacher, to dislodge him—without sacrificing the inheritance he may leave them. Awkwardly shot and rather too prolonged, the film exemplified how loose-limbed Shochiku comedy could get.

A brace of films by Shochiku stalwart Gosho Heinosuke, The Bride Talks in Her Sleep (1935) and The Groom Talks in His Sleep (Hanamuko no negoto, 1935), showed other newlyweds with comic problems. Again the motif of spying plays a role. (Naughty voyeurism was essential to that strain in popular culture called Ero-guru-nansensu, “erotic-grotesque nonsense.”) Salaryman Komura’s pals have learned that his wife talks in her sleep, and so they drop by to hear for themselves. Unfortunately they drink so much that they fall asleep and miss the big revelation. Plot complications include a burglar, the couple’s decision to sleep elsewhere, and the revelation of what keeps the bride “sleep-talking.”

Only a little less slight is The Groom Talks in His Sleep. Here the title probably gives away too much, because the initial puzzle is why the young wife naps during the day. This scandalous dereliction of housewifely duty leads eventually to a demand for divorce until the cause, the husband’s sleep-talking that keeps her awake all night, is revealed. The family brings in a self-styled hypnotist, played with relish by Ozu regular Saito Tatsuo, to cure the groom.

Gosho is said to be the fastest cutter among classic Japanese directors, but I’m not sure that he goes much beyond what was fairly standard at Shochiku. Most of the studio’s directors working in the contemporary-life genre (gendai-geki) employed what I called in my book on Ozu “piecemeal découpage,” a breakdown of action and dialogue akin to that seen in late US silent films. What Gosho does have in abundance is different camera positions. In The Bride, our introduction to Komura’s drinking buddies takes place at a bar, and I didn’t spot any repeated setups. Throughout the two films, each composition is calibrated to a specific item of information—a line of dialogue, a reaction shot, or a change in the staging. This makes for a tidy visual texture, which is an advantage in the rather loose plotting that’s characteristic of Shochiku comedy (Ozu, always, excepted).

At the other extreme were some very serious drama, such as Mizoguchi’s relatively well-known Poppies (Gubinjinso, 1935) and the more obscure Mizoguchi-supervised Ojo Okichi (1935). There was as well Okoto and Sasuke (Shunkinsho: Okoto to Sasuke, 1935), another Shimazu work. It’s based on a Tanizaki Junichiro tale of male devotion passing into love and masochism. Okoto is blind, but her family can afford to pamper her. She takes up the koto and the family’s young servant Sasuke faithfully escorts her to her music lessons. She often treats him disdainfully, but she insists on his company, and so gossip grows up around them. Sasuke’s loyalty is tested when Okoto is wooed by a vacuous but persistent suitor. Spurned, he arranges an attack on her, which triggers Sasuke’s ultimate sacrifice.

Shimazu treats this story with a calmness that builds up tension between the often wilful Okoto and the simple-hearted Sasuke. The discreet simplicity of the film’s technique, excepting the violent climax, can be seen in an almost throwaway moment. Sasuke as been assigned to tutor two of Okoto’s students, and they laugh at his efforts. As they rise, Shimazu cuts to a new angle, putting them the background and showing Okoto is shown growing anxious in the foreground.

Keeping Sasuke out of focus and far back allows Shimazu to stress a micro-movement in the foreground: Okoto’s shift from sympathy for Sasuke to her usual imperious annoyance. After unfolding her hands, she clenches her right hand and softly strikes it on the edge of the brazier.

As Okoto turns to summon him for a mild dressing-down, still keeping her little fist extended, Sasuke has shifted his position slightly so that he is a more active responder to her.

This sort of directorial discretion, so characteristic of classic Japanese cinema, seems today to come from another world.

Probably the greatest revelation of the Shochiku show was another masterwork by the ever-more-impressive Shimizu Hiroshi. A Woman Crying in Spring (Nakinureta haru no onna yo, 1933), Shimizu’s first sound film, was given its western premier. It was chosen to exemplify his experiments with sound–experiments that induced Ozu to try his own hand at talkies.

Mining work in Hokkaido brings day laborers by ship, along with women who wind up serving them drinks and perhaps something more. Most of the action takes place in a tavern with a bar downstairs, women’s rooms on the next story, and a small upstairs where the mysterious, somewhat cynical Chuko keeps her daughter. Kenji and his boss become rivals for Chuko, and a young woman drawn into prostitution further complicates the situation.

After only a single viewing, I’m pressed to say much more than noting that Shimizu sacrifices some of his geometrical precision (discussed here) to a more naturalistic treatment of the bar’s space and more experiments with chiaroscuro lighting. A somewhat flamboyant scene, in which our view of a fistfight is mostly blocked by a high wall, shows how Shimazu was trying to let sound do duty for the image. The title has multiple implications: the woman we see crying at the outset is Fuji, the girl initiated into the trade; but at the end, Chuko is weeping. Moreover, as Alexander Jacoby pointed out, the scenes we see are all set in winter, although the ending suggests that the couple that is created will find spring elsewhere. Long unavailable in its Japanese VHS edition, A Woman Crying in Spring is ripe for Western distribution.

Last notes from Kristin

Despite my commitment to the Polish, Indian, and Japanese threads, I was able to fit in a film or selection of shorts now and then.

On the afternoon of the opening day, the first “Cento Anni Fa” program for 1914 included a couple of interesting items. One was La guerre du feu, a French film directed by George Deonola. It dealt with a tribe of fur-clad cavemen who have captured fire but lack the knowledge to create it themselves. Thus they must tend their fire constantly and protect it from a rival tribe. In the course of the action the hero learns the secret to using tinder and flint to generate a blaze. This, it has to be said, was more interesting as an historical curiosity than as entertainment.

Not so the final film of this group, Amor di Regina (Guido Volante, 1913). Its unusual story dealt with a queen of an unnamed country who is having a secret affair with a young soldier. When the latter gets wind of a rebellious group’s plans to assassinate the king, the hero and the queen manage to spirit him out of the palace and away to exile. It struck me that in a more conventional film, the lovers would use the assassination of the king to allow them to marry. Instead they take care of the king in exile and watch for a chance to reinstate him.

Stylistically there were some impressive shots. In one, we see a close-up of the back of the hero’s head, looking out from a terrace at a group of conspirators in the distance sneaking toward the palace, and the camera racks focus from him to them–for 1913, a highly unusual way to handle a very deep composition. If anyone is contemplating a DVD/BD release of some Italian short features of this era, Amor di Regina would be a good choice.

Another 1914 program included the lovely La fille de Delft, which, along with Maudite soit la guerre (which was shown at one of the Piazza Maggiore screenings), is one of Alfred Machin’s best-known films. Its plot concerns a little country boy and girl who are dear friends; a variety-theater owner sees them dancing at a country celebration and takes the girl off to the city to become a star. Seeing it again, I was struck at how marvelously natural the performances of the two child actors (above) was, something that goes a long way to making this film so very affecting.

Despite the fact that all of Tati’s early short films are on the new French boxed Blu-ray set, I decided to see the Tati program on the big screen. Seen again, Gai dimanche (1935) seemed a bit labored in its humor, dealing with two layabouts who hire an old car and persuade several people to purchase day trips to the country. The situation seems more the sort of thing that René Clair could have made work, but director Jacques Berr makes it somewhat leaden.

Soigne ton gauche centers on a gawky farmhand who is mistaken for a boxer by a promoter and ends up in a practice ring with a tough opponent. Tati creates a very Keatonesque situation as the naive young man finds a book on boxing on his stool and proceeds to consult it at intervals (below). As he assumes classic boxing poses, the experienced boxer uses brute force to knock him silly.

The opening and closing of Soigne ton gauche contains a comic, bicycle-riding postman, and clearly Tati recognized the comic potential of the character. In his first directorial effort, L’école des facteurs (School for Postmen, 1946), Tati himself played the postman François, who tries to please his teacher by finding ways to deliver the mail more swiftly. The idea proved so fruitful that the film was remade as Tati’s first feature, Jour de fête. The bouncy music and many of the gags were retained, and the longer film’s success established Tati as a major director and star.

To all our friends and the coordinators of Cinema Ritrovato: Thanks for another wonderful year!

You can watch The Eye’s tinted copy of Maison Fifi here.

Miriam Silverberg’s Erotic Grotesque Nonsense offers a thorough discussion of Japanese popular culture of the 1930s. For more on Kido Shiro’s influence on Kamata cinema, see Mark Schilling’s Kindle book Shiro Kido: Cinema Shogun. I discuss trends in 1930s Japanese film style in Chapters 12 and 13 of Poetics of Cinema. For more on the restoration of Machin’s films, see our entry here.

Soigne ton gauche (1936).