Archive for the 'National cinemas: Hong Kong' Category

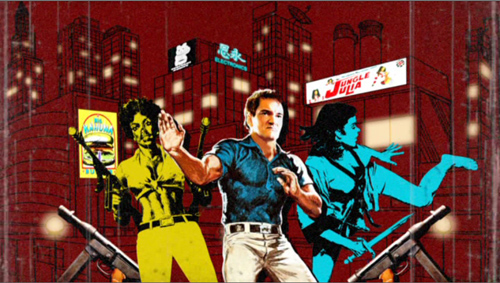

Triple play

The Disciple of Hong Kong.

First, if you haven’t yet visited Jim Emerson’s Scanners blog entry on “Geriatric Noir,” you must do it pronto. It confirms once more the spontaneous genius of the American people. We are the world’s very best at smart-alec, disrespectful, shameless humor.

Second, I’ve just received an advance copy of Jac and Johan’s film The Disciple of Hong Kong. It’s an essay on Tarantino’s debt to Hong Kong film. Twitch announced it here, and you can watch the trailer here.

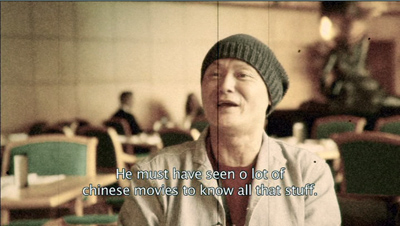

This is a fan’s fever dream. It features interviews with many HK film experts like Roger Garcia and Bey Logan, along with local legends Raymond Chow, Ringo Lam, Simon Yam, and Gordon Liu, below. The movie is a load of fun, with many clever retro touches, and I learned a lot from it.

I wander in from time to time, with probably my most significant line being “Excuse me, do you have any syrup?”

It’s coming up on 26 June on a French channel dedicated to action films. I don’t know exactly when it will be available otherwise. For some clues to the identity of directors Jac and Johan, go here. Frederic Ambroisine, another HK film expert, was involved with the project as well. His site is a remarkable video resource, and he currently writes at actionqueens.com and alivenotdead.com.

Third and finally, Kristin and I are soon off to Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato. We will be blogging.

Speaking of shameless: To get more of my take on HK cinema, visit the Hong Kong national cinema category below. If you’re really devoted, or just at a loss for how to spend $15, pick up a copy of my e-book Planet Hong Kong.

Rukik Sallé (Mad Movies), Fred Ambroisine, Jac, and Johan. Hong Kong, 2011.

Time for a quick one: A miscellany from friends

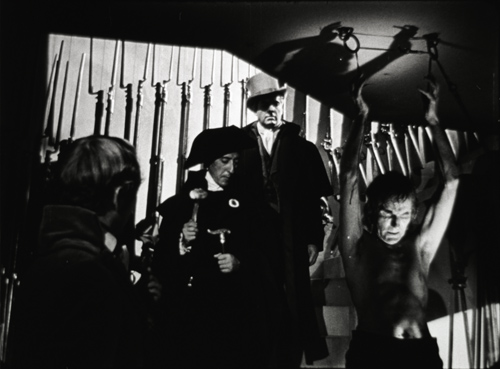

The Black Book (aka Reign of Terror).

DB here, catching up with books, videos, and events:

David Cairns has written a lively appreciation of William Cameron Menzies for the March/ April issue of The Believer. The essay bristles with rapid-fire aperçus, such as the suggestion that the great, demented Kings Row is something like the Twin Peaks of its day. David is particularly good at plotting the extent to which Menzies dominated the work of his directors. Directors without a visual style of their own, he points out, were easy for Menzies to overwhelm, but those with an already-developed signature could assimilate his contributions, as Hitchcock did in Foreign Correspondent.

David Cairns has written a lively appreciation of William Cameron Menzies for the March/ April issue of The Believer. The essay bristles with rapid-fire aperçus, such as the suggestion that the great, demented Kings Row is something like the Twin Peaks of its day. David is particularly good at plotting the extent to which Menzies dominated the work of his directors. Directors without a visual style of their own, he points out, were easy for Menzies to overwhelm, but those with an already-developed signature could assimilate his contributions, as Hitchcock did in Foreign Correspondent.

In The Black Book (aka Reign of Terror) Menzies found soul mates in two other aggressive pictorialists, Anthony Mann and John Alton, the team becoming “a crazy triangle,” eager to indulge in “thrusting gargoyle faces in fish-eye distortion, clutching shadows, and funky, teetering compositons.” Bob Cummings never looked so bizarre, before or since. I didn’t talk about this wild movie in my online Menzies material here and here because I had such poor illustrations from it. Now things have changed, and a decent, or perhaps rather indecent, sample of the film’s delirium (above) can serve to back David’s point.

David’s “Dreams of a Creative Begetter” is one of several film-related pieces in this issue of The Believer. The issue includes a DVD of the seminal People on Sunday (Menschen am Sonntag, 1930), which gathered the talents of Billy Wilder, Curt Siodmak, Robert Siodmak, Edgar G. Ulmer, Fred Zinnemann, and Rochus Gliese. A helpful introductory essay is at the Believer site.

Speaking of David’s writing, don’t miss his superb shot-by-shot analysis of a key scene in Gilda at his Shadowplay site, an obligatory stop for all cinephiles.

Seldom does a monograph on a single film probe so deeply as Mette Hjort’s new book on Lone Scherfig’s Italian for Beginners. It’s easy to take this movie as Dogme Lite, since compared to the earliest, rather harrowing Dogme efforts, it’s an ingratiating romantic comedy-drama. Mette does justice to this side of Scherfig’s film, but she also shows that it’s an exercise in moral seriousness. Reconstructing the production process, she conducts in-depth analysis of performance and technique. She is sensitive to actors’ moments, such as simply laying down a knife and fork; aware that these gestures are developed through improvisation, she is able to trace how each character is built up through details.

In her books and articles on the Dogme school Mette has shown that its innovations go beyond the vaunted technical “rules.” She always addresses them, of course; here she provides an illuminating typology of ways the rules have been followed or dodged. But she also stresses, as most writers don’t, that Dogme films engage with matters of political importance. For example, she has shown that The Idiots’ controversial display of “spazzing” triggered an important debate about Danish attitudes toward the disabled. In her new book Mette indicates that Scherfig’s efforts to endow her characters with the dignity to be found in everyday life offers viewers a chance “to re-connect with one of their culture’s most powerful moral commitments.” Mette talks about the project in this video.

David Gordon Green directs Your Highness; Justin Lin signs his third Fast & Furious movie. With indie filmmakers eagerly joining the tentpole and franchise business, the whole phenomenon seems due for a rethink. This makes Michael Z. Newman’s Indie: An American Film Culture all the more necessary. Although I can’t be unbiased, because I served as Michael’s advisor on the dissertation that became the book, I think that any reader would find the result a fresh and vigorous exploration of the achievements of the Sundance/ Miramax generation.

David Gordon Green directs Your Highness; Justin Lin signs his third Fast & Furious movie. With indie filmmakers eagerly joining the tentpole and franchise business, the whole phenomenon seems due for a rethink. This makes Michael Z. Newman’s Indie: An American Film Culture all the more necessary. Although I can’t be unbiased, because I served as Michael’s advisor on the dissertation that became the book, I think that any reader would find the result a fresh and vigorous exploration of the achievements of the Sundance/ Miramax generation.

Michael starts by looking closely at the audiences and marketing. He suggests that viewers engage with the films through particular viewing habits (e.g., “Characters are emblems”). He then shows how these habits were nourished and refined by distributors, promotion, and film festivals. The next two sections of the book consider what we might take to be the two poles of indie difference from Hollywood: greater realism, and more self-conscious artifice. The central chapters analyze realism in relation to “character-centered” filmmaking in the Indie trend. Michael turns a critical eye on characterization in films as different as Walking and Talking, Lost in Translation, and Welcome to the Dollhouse. The third batch of chapters considers the trend’s other major appeal, the sort of play with style and form we get in the Coens, Tarantino, Nolan, and others.

Michael shows how character-driven realism and gamelike artifice mesh well with the mandates of distribution and reception—how, in effect, “originality” becomes something that can be calculated and branded. The book concludes with thoughts on the evolution of the trend, comparing Happiness with Juno and raising the inevitable question: How artistically independent is independent film? Newman leaves us pondering: “Indie cinema has become Hollywood’s most prominent alternative to itself.”

One of the hallmarks of the Wisconsin program in film studies is its nuanced refusal of the art/ commerce duality that supposedly rules filmmaking. From many angles, researchers here have shown that creative impulses and business mandates mix in complicated ways, and the results are often fascinating. Indie is one example of this sort of research project, and so is another dissertation-become-book, Christopher Sieving’s Soul Searching: Black-Themed Cinema from the March on Washington to the Rise of Blaxploitation. (Again, I was involved, serving on the committee chaired by Tino Balio.)

One of the hallmarks of the Wisconsin program in film studies is its nuanced refusal of the art/ commerce duality that supposedly rules filmmaking. From many angles, researchers here have shown that creative impulses and business mandates mix in complicated ways, and the results are often fascinating. Indie is one example of this sort of research project, and so is another dissertation-become-book, Christopher Sieving’s Soul Searching: Black-Themed Cinema from the March on Washington to the Rise of Blaxploitation. (Again, I was involved, serving on the committee chaired by Tino Balio.)

Chris concentrates on 1960s black-themed films from A Raisin in the Sun onward, because he wants to trace how filmmakers tried out a variety of ways to represent and comment on black life. It was a transitional era, but as he puts it “because of the insights they reveal about the periods that bracket them, transitional periods are among the most fascinating and significant in all of film history.”

For Chris, Gone Are the Days (1963), The Cool World (1964), Uptight (1968), The Landlord (1970), and the unproduced Confessions of Nat Turner provide case studies of alternatives to what became the crime-and-comedy product of blaxploitation. Why did decision-makers believe that black-themed films would sell broadly enough to repay investment? What choices and compromises were necessary to “universalize” material (for white viewers) while also retaining “authentic” blackness? Or was it better simply aim the films at white liberals?

Chris tackles such questions through a painstaking study of the film industry’s efforts to find, or create, an audience for films that took great risks. Written with verve (on the screen handling of the Black Panthers, Chris talks about Hollywood’s “Black Power outage”), Soul Searching revives films that are all but forgotten and shows how their efforts to create one variety of independent cinema failed for particular social and industrial reasons.

Someone I’ve been meaning to spotlight for a while: Frédéric Ambroisine is a multitalented critic, filmmaker, stuntman, and collector based in Paris. One of his careers is making supplements for French DVD releases of Hong Kong films, both classic and current. If you have even a smattering of French, you can follow his supplements with ease. He gets precious interviews with screen legends like Kara Hui Ying-hung and Ku Feng (below), master villain of the great New One-Armed Swordsman.

The videos from Wild Side often include Fred’s featurettes. You can follow Fred’s activities at actionqueens.com and alivenotdead. Much of the material in both places is in English.

Finally, if you’re in Los Angeles this week, why not visit the celebration of Orphan Films playing at UCLA 13 and 14 May? While I was in New York in February, I met NYU’s Dan Streible, moving spirit of the Orphan Films movement. Dan and his colleagues work with archives, collectors, and filmmakers to save films that fall through the cracks, digging up everything from home movies to news clips and experimental cinema. Dan curated a program of orphans at our local festival earlier this spring. At UCLA he will be a guest for screenings and discussions of many orphan titles, including the mysterious Madison Newsreel (Madison, Maine alas, not Wisconsin). Go here for Sean Savage’s discussion of the orphan oddity that has become a cult movie, and here for background on Northeast Historic Film, which found the footage.

PS: Speaking of friends, I should thank the solicitous people who wrote me during my recent illness. I appreciate your get-well notes, and I’m happy to report that I’m on the mend.

“World’s Youngest Acrobat” (Hearst Metrotone/ Fox Movietone 1929). From Orphans 7: A Film Symposium.

A matter of ‘Scope

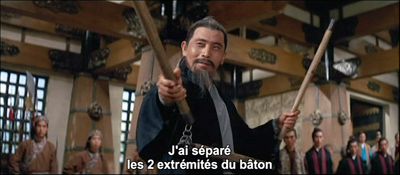

Killer Constable.

DB here:

Like most cinephiles of my vintage, I love anamorphic widescreen, especially in its early years. Even though CinemaScope as a trademarked format is long gone, its aspect ratio of 2.35 or 2.40 to 1 became the standard, and we tend to call any widescreen film of those proportions a “‘Scope” production.

Nowadays many films are in ‘Scope; it’s sensed as a cool ratio. Too cool, actually: I’m not sure that Cop Out and The Hangover needed to be in ‘Scope. Things were quite different in Asian cinema during the 1960s and 1970s, where directors had to learn how to master and exploit the new acreage available to them. I was reminded of their problems, and some of their dazzling solutions, when I visited films that were part of two big retrospectives at the Hong Kong Film Festival this year.

The Shochiku touch

Festival goers tend to ignore their cities’ round-the-year programming. We’ve shown films at our Cinematheque that would have drawn more strongly if they had been presented under the umbrella of a festival. A festival is a big, ballyhooed event, and people set aside time to plunge into it. They take it as an occasion to explore cinema. But that impulse isn’t as strong, I think, in other seasons.

Accordingly, the HKIFF has developed a smart strategy. It often launches a retrospective during the festival period but then continues it after the festival is finished. This enables the festival to spotlight the series more vividly and to engage viewers to return in the weeks to come. The drawback is that the strategy tantalizes us visitors, who wish we could stay on to get a full dose of Shimizu Hiroshi (subject of a 2004 roundup) or Kinoshita Keisuke (2005) or Nakagawa Nobuo (2006). This year’s hors d’oeuvres were even more scanty: only two of the films of Shibuya Minoru played during the festival, which ended Tuesday. The rest come later in April.

At the venerable Shochiku studio, after assisting Naruse Mikio and Gosho Heinosuke, Shibuya worked with Ozu on What Did the Lady Forget? (1937) before launching his own directing career. He made over forty films, the last one released in 1966. My own awareness of Shibuya before my visit was limited to the family dramas A New Family (Atarashiki Kazoku, 1939) and Cherry Country (Sakura no kuni, 1941), both in a mildly, though not rigorously, Ozuian vein.

At the venerable Shochiku studio, after assisting Naruse Mikio and Gosho Heinosuke, Shibuya worked with Ozu on What Did the Lady Forget? (1937) before launching his own directing career. He made over forty films, the last one released in 1966. My own awareness of Shibuya before my visit was limited to the family dramas A New Family (Atarashiki Kazoku, 1939) and Cherry Country (Sakura no kuni, 1941), both in a mildly, though not rigorously, Ozuian vein.

The earlier film in the partial Shibuya retrospective was Righteousness (1957), an ensemble piece about a neighborhood still laboring under postwar hardships. The young Seitaro is in love with Michiko, but her mother offers her in marriage to her more prosperous roomer. Seitaro works as a mechanic for a bus company, where Fujita is a driver. Fujita has just married a young woman against his father’s wishes. The characters are introduced through the peripatetic Okyo, Seitaro’s mother, who peddles black-market goods to her neighbors. Fujita’s troubles mount up when his bus hits a child, and Seitaro must decide whether to reveal what he knows about the accident. The film builds well to two climaxes, the consequences suffered by Seitaro after he makes his painful decision and then Okyo’s denunciation of her neighbors. On the other side of the ledger, Fujita’s domestic troubles are resolved rather abruptly and implausibly. Still, Righteousness exemplifies the classic Shochiku formula of smiles mixed with tears, capped by a more-or-less upbeat resolution.

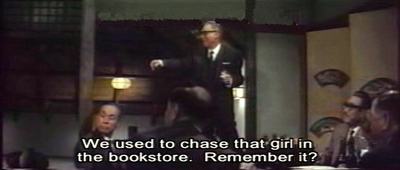

Shibuya was shadowed by Ozu even after the master’s death, for he was assigned to make a memorial film based on the last project planned by Ozu and screenwriter Noda Kogo. This was the film now circulating as Mr. Radish and Mr. Carrot (1965).

Chris Fujiwara has provided us an enlightening account of how Shibuya turned what would probably have been another subtle Ozu meditation on generational strife, in the manner of An Autumn Afternoon, into a more raucous comic melodrama. Yamaki is an executive who lives by strict routine, but he’s also pestered by his four daughters and his lothario brother. When a friend comes down with cancer and the brother reveals himself as an embezzler, Yamaki flees without warning. As his family fret about him, and quarrel among themselves, he settles in among working people, notably some prostitutes and a swindler selling Chinese medicine.

No one in the family displays much virtue, and even Yamaki is seen as cranky and oblivious to the needs of his wife and children. Radish and Carrot’s cynicism seemed to me too easy, and the physical comedy, such as Ryu Chishu’s bodily contortions, struck me as forced and overplayed. Stylistically, the film is eclectic and almost casual. It begins with a zoom and a whip pan. Thereafter, we get flash cuts, canted setups, and a fashion show. Unlike Righteousness, this film justifies Fujiwara’s claim, in a HKIFF catalogue essay not available online, that Shibuya sometimes embraced “visual excess.”

Ozu refused widescreen filming; he compared the ‘Scope frame to a roll of toilet paper. He may have realized that it would pose problems for his graphically matched cuts, deep and subtly imbalanced compositions, and other techniques he had refined over decades. Similarly, Radish and Carrot made me wonder if Shibuya was comfortable working in ‘Scope. He drops in some Ozuian corridor images, but at other times he mounts the sort of packed wide-angle shots common in 1960s Japanese anamorphic films.

When Ozu fills up his 4×3 frames, he gives us more to look at, along with more daring placement of figures. This is not your typical establishing shot.

Ozu’s signature shot is at a low height but seldom at a low angle. Shibuya’s compositions remind you what a real low-angle image looks like, with the camera tipped up considerably.

I know, it’s unfair to judge Shibuya’s film by the exalted standards of Late Autumn (1960), and we risk saddling him with purposes he didn’t have. He probably didn’t set out to make an Ozu pastiche. Yet we can, I think, fault Radish and Carrot sheerly on craft grounds. Two party scenes, one gathering men and one among wives, seemed to me almost haphazard in their spatial development. This cut, for instance, is more careless than anything I noticed in Righteousness.

In the second shot, on the far right side, a waitress is now in the frame next to the old man, and he has already turned and is talking to her instead of his classmates at the other table. When this film was made, younger directors, like Suzuki Seijun and Oshima Nagisa, were already handling ‘Scope with much more assurance. I look forward to seeing more Shibuya widescreen entries to learn if they made more polished use of the format.

Elegance and vulgarity

The other retrospective in question was devoted to Kuei Chih-hung (in Cantonese, Gwei Chi-hung), a Shaws director who has been overshadowed by the more famous Chang Cheh and Li Han-hsiang (here and here on this site). Kuei worked in several genres, including the sex movie and the horror film, and he was able to supply cheap items in quantity. But he stands out partly because he moved outside the opulent Shaw studio to shoot on locations. Working with an efficient crew and a lightweight camera, Kuei produced some films, like The Delinquent (1973) and The Teahouse (1974), that look forward to the social realism of the New Wave that followed. Like some New Wavers as well, Kuei highlighted the cruelty of class warfare in Hong Kong both past and present. Ironically, he ceased directing when he felt that the young generation had pushed things further than he could go.

The other retrospective in question was devoted to Kuei Chih-hung (in Cantonese, Gwei Chi-hung), a Shaws director who has been overshadowed by the more famous Chang Cheh and Li Han-hsiang (here and here on this site). Kuei worked in several genres, including the sex movie and the horror film, and he was able to supply cheap items in quantity. But he stands out partly because he moved outside the opulent Shaw studio to shoot on locations. Working with an efficient crew and a lightweight camera, Kuei produced some films, like The Delinquent (1973) and The Teahouse (1974), that look forward to the social realism of the New Wave that followed. Like some New Wavers as well, Kuei highlighted the cruelty of class warfare in Hong Kong both past and present. Ironically, he ceased directing when he felt that the young generation had pushed things further than he could go.

The crime-centered plots of The Delinquent, The Teahouse, and Big Brother Cheng (1975) manage a fair amount of outrage at policing and justice in Hong Kong, as do Kuei’s contributions to a series of omnibus films called The Criminals. His excursions into exploitation fare with Bamboo House of Dolls (1973), Killer Snakes (1974), and the Hex cycle (1980 and after) show, if nothing else, how anxious Shaws was to retain market share in the face of the thrusting popularity of Golden Harvest releases. Obliged to go gross, the man didn’t flinch. The Boxer’s Omen (1983), a supernatural kickboxing yarn, features one rite that demands that celebrants chew food, spit it out, and pass it along to be eaten by others. (No fakery, everything done in one shot.) My tastes run more to something like Killer Constable (1980).

It’s a shooting-gallery plot. Constable Leng and his team are sent to recover gold stolen from the Empress’s palace, and one by one the fighters are eliminated in skirmishes with the thieves. Kuei pointed proudly to the social criticism in the film: “I simply wanted to depict how insignificant commoners are and how, under totalitarian rule, they turn out to be the victims.” Leng, preferring to kill lawbreakers rather than bring them to trial, pursues the bandits with unblinking ferocity. When he finds a miller who helped the gang, he decapitates the man in front of his wife and squalling baby. But Leng’s brutality meets its match in the bandits, who devise comparably sadistic ways to decimate his posse.

Killer Constable comes near the tail end of the Shaws output, just a few years before the company largely abandoned theatrical film production in favor of television. Kuei is thus able to absorb and advance some of the studio’s signature techniques. His film starts out in the splendor of high-key lighting and saturated color typical of Shaws court epics, but soon enough, sword battles play out by torchlight or in semidarkness.

As for ‘Scope, Kuei had the benefit of a strong tradition. In action films, both Japanese and Hong Kong directors cultivated a “precisionist” use of the ratio that made parts of the composition–sometimes widely distant parts–click into place one by one, at a staccato pace. Here are phases of an early fight in Killer Constable.

The rhythm builds, from the cut to the new angle, then the peekaboo flip of the window, then the spotlighting of Leng in the lower right, and finally the thrusting hand of his victim in the extreme left, at which point the shot comes to rest.

‘Scope felicities like this may stem as much from the power of the tradition as from Kuei’s individual talent. In any case, his retrospective, like the Shibuya one, shows that we haven’t fully charted the range of expressive possibilities opened by popular Asian cinema in their early encounters with widescreen.

Chris Fujiwara’s survey essay, “Irony, Disenchantment, and Visual Excess: The Style of Shibuya Minoru,” appears in the HKIFF catalogue, available here. In Chapter 12 of Poetics of Cinema, I illustrate Japanese filmmakers’ relative laxity about the 180-degree matching system with a couple of shots from Shibuya’s A New Family. The passage in question may be one-off borrowing from Ozu.

The Hong Kong Film Archive book devoted to Kuei Chih-hung provides precious information not only on the director but also on the Shaws studio system. For more on widescreen style at Shaws see my online essay, “Another Shaw Production: Anamorphic Adventures in Hong Kong.” I discuss the rhythmic resources of Hong Kong combat in Chapter 8 of Planet Hong Kong.

Other continuing retrospectives at this year’s HKIFF are devoted to Abbas Kiarostami and Vietnamese cinema from 1962-1989. If you’re passing through town, you could do worse than check them out.

Thanks to Li Cheuk-to for correcting some information.

Opening title for Mr. Radish and Mr. Carrot.

Observations on Filmart (This is not a typo)

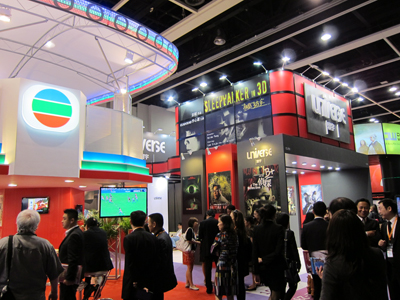

A modest display at Filmart, Hong Kong Convention Centre.

DB here, channeling an apparently apocryphal Soupy Sales line:

Kids, what starts with f and ends in art? No, not that. It’s Filmart, the annual trade gathering that kicks off the Hong Kong Film Festival. Add a space and a capital, and you have the main title of one of our books. Sometimes accidental cross-promotion can work out pretty well, as you see above.

Seriously, though, Filmart is a wonderful event. It includes an opening ceremony to launch the festival, the Asian financing forum known as HAF, the Asian Film Awards (covered a bit here), and a teeming meet-and-greet that sponsors panels, lunches, and hundreds of booths that allow media buyers and sellers to get together. I’ve covered Filmart in 2007, 2008, 2009, and 2010. Here are some comments and images from last week’s edition.

The shebang started with the ceremony introducing some of the opening films and their stars. Here the Filmart’s official hostess, Miriam Yeung, is about to go onstage to greet the audience.

And here at the ceremony are the three stars of Don’t Go Breaking My Heart, Gao Yuanyuan, Daniel Wu, and Louis Koo.

Ho Yuhang’s clever neo-noir Open Verdict was a highlight of the shorts collection Quattro Hong Kong 2. Here he is with his star, the radiant Kara Wai Ying-hung, Shaw Brothers action queen and star of both Open Verdict and Ho’s earlier feature Daybreak.

Filmart’s main business takes place in a vast hall, with companies’ displays lined up in rows and along aisles. Most firms have fairly modest stalls, but others are flamboyant, like these big boys for Mei Ah and Universe, two long-established Hong Kong production/ distribution companies.

But the place isn’t so big that you can’t run into old friends, like Margaret Pu (far right) and her colleagues Jack Lee and Dan Zhu from the Shanghai Film Festival.

More movers and shakers: Patrick Frater, CEO of Film Business Asia, and Peggy Chiao, producer (Trigram Films) and doyenne of Taiwanese New Cinema.

At Filmart one can always find some unclassifiable items, as witness the project pictured at the very end of this entry.

New Action on the Mainland

Most panels ran opposite film screenings, so I usually plumped for the movies. But I did attend an intriguing session on “Beyond Box Office: China: The World’s Largest Developing Market.” Sponsored by the Hong Kong Film New Action committee and moderated by Shanghai media executive Bill Zhang Ming, the panel included many Chinese figures and the American Ted Perkins, who has worked for both Warners and Universal and is now serving as executive VP of production for IDG China Media.

Some of the themes discussed echo things I talked about in the added chapters of Planet Hong Kong, but I garnered some new information as well.

*Several panelists pointed out that the stupendous growth in the Chinese box office, over 50% each year, demands that many new cinemas be built. The major cities have now got a good supply of screens, but now the third- and fourth-tier cities need to have more screens. Some commentators spoke of a “new five-year plan” aiming to upgrade and increase the nation’s screens.

*As in America and other countries, a few films typically garner the lion’s share of receipts; one panelist estimated that 80% of income stems from 20% of the films. For the foreseeable future, the big films, from China or the US, will drive the market.

*The growth of the market is even more remarkable given the comparatively small audience (around 20 million, one panelist surmised). Average ticket price is 32 renminbi, or about US$4.88.

*Hong Kong remains essential to the mainland market but also vulnerable. Films with local stars and directors can succeed, and Hong Kong is a key site for financing and packaging projects. But purely local films will remain low-budget items; the bigger films will be mainland co-productions, with some PRC talent and scenery on the screen.

*The popular audience, according to screenwriter-producer Qi Hai, is driven by female tastes: date movies are chosen by the woman, and family films are picked by mothers.

*Ted Perkins pointed out that although recent growth is good for all players, in any film industry there are always more funds in production than can be recouped overall. There will be winners and losers, especially if there’s an overabundance of production, as there currently is on the mainland. Although about 500 films were produced last year, more than half did not find theatrical release or screen in the best cinemas. (Panelists’ estimates of unseen or underseen titles varied from 250 to 400.) Marcus Lim provides a comparable set of figures.

*Some panelists opined that the market lacks directors and stars who are likely to provide success. One panelist estimated that only half a dozen directors have strong track records, and only one star, Ge You, can guarantee an audience.

*Most panelists agreed that 3D was not viable for most films, but in China the new format can help the business in an unusual way. Historically, most mainlanders couldn’t afford going to films, so they aren’t in the habit of attending theatres. They watch films on video or on the Net. Curiosity about 3D may attract new cinemagoers, “educating” spectators to the pleasures of seeing movies on the big screen.

*Most big countries have a well-structured pattern of “windows,” whereby a film moves from the theatre to video, cable, and online. But in China, the expansion of screens is occurring simultaneously with the growth of online distribution, with the danger of piracy. The Chinese will have to come to grips with decisions about pricing and more stable windows.

Seldom do we have a chance to realize that we’re witnessing a historic change in the global film industry. The rise of China is such an event, and film historians should be watching the unfolding process closely.

Changing the film ecology

The Jockey Club Cine Academy, formed last summer, is an educational enterprise guided by the HKIFF Society and funded by the Hong Kong Jockey Club Charities Trust. It’s a three-year program aiming to increase film literacy among young people. The Academy held a major event during Filmart, a nearly three-hour master class with Jia Zhangke, director of Platform, The World, Still Life, and most recently I Wish I Knew. High school students made up a large part of the audience.

Researcher and editor Wong Ain-ling (above, with Jia) interviewed him about his career and then opened things up for questions. Here are a few points Jia made.

*His recent turn toward documentary filmmaking isn’t a new development for him. When he was starting out, documentaries were the most dynamic part of the PRC film scene. Although the films captured aspects of contemporary life ignored by mainstream movies, they were seldom watched by audiences. So the question for Jia became: “How to change our film ecology?”

He has used a documentary project to spark a fiction feature. In Public (2001) became a draft for Unknown Pleasures. Jia enjoyed eliminating dialogue and narration from his documentaries, relying on peoples’ faces and situations to convey ideas. Critics complained that documentarists couldn’t tell stories, but he wanted mainland audiences to learn to find the latent emotions in the scenes, the “poetic” side of realistic cinema.

*His early films incorporated popular music, including Taiwanese tunes sung by Teresa Teng. Why? During the 1980s and 1990s, mounted loudspeakers broadcast a lot of Mandarin pop songs, making this music just part of a city’s ambience. This was something he exploited in his first feature, Xiao Wu.

*Jia had arguments with censors on his first three features, and those films weren’t widely seen. But in 2004, the censorship system changed, mostly for the better. Yet distributors still block films shot on video from being shown in cinemas, creating what Jia called a “technical censorship.”

*The reports are true: He is making a martial arts film with Johnnie To’s Milkyway firm. Jia wants to examine the imperial system in the period around 1900. He would like to follow it with another historical film, this one about Hong Kong in 1949, centering on two characters, a Communist and a KMT Nationalist.

Like Hong Kong itself, Filmart has a pulsating energy and offers an overwhelming array of choices: you can watch movies, attend events, and just gawk. You must run to keep up. That’s as it should be.

For more coverage of industry doings at Filmart, see Liz Shackleton’s rundown at Screen International (may be proprietary). Another story in Screen International mulls over the prospect that China could fairly soon become the world’s biggest market. See as well several items at Film Business Asia, particularly Stephen Cremin’s article on Chinese coproductions. For our takes on some Jia Zhangke films, you can go to this category.

PS 31 March (HK time): I should have mentioned what the New Action panel did not: Piracy. The LA Times has a good recent article on DVD bootlegging in the PRC, raising the crucial factor I’ve heard mentioned as well: the role of the People’s Liberation Army.