Archive for the 'National cinemas: Hong Kong' Category

Bond vs. Chan: Jackie shows how it’s done

DB here:

During the 1990s several critics began to notice that filmmakers were doing something odd with action scenes.

Directors were consciously, even joyously, sacrificing clarity. When two characters were punching it out, the framing didn’t make it easy to know who was hitting whom, and how. Changes in angle and shot scale were sometimes so abrupt that you had little time to adjust. The cutting pace was so quick that you couldn’t entirely register the movement in shot A before shot B replaced it. Sometimes the spatial layout of the fight was confusing as well: too many close views, too few master shots. Later, the return of handheld shooting made many action scenes even more illegible, blurring and smearing them to the point that sound (as in the Bourne films) had to specify that a body has hit a window or a hand has busted a bottle. Now we have Sylvester Stallone’s The Expendables, which might be a new summit in overbusy, incoherent, inconsequential action.

I wrote about this trend back in the 1990s, and I’ve returned to it on occasion since. Other writers, notably Todd McCarthy of Variety, noticed it too. He referred to the full-throttle editing and “frequently incoherent staging” on display in Armageddon (1998): “Bay’s visual presentation is so frantic and chaotic that one often can’t tell which ship or characters are being shown, or where things are in relation to one another.”

A decade later comes Peter DeBruge’s review of the “muddled execution” of The Expendables: Staging simultaneous fights “might’ve worked had the editors assembled all that footage in such a way that we could tell where characters are in relation to one another or what’s going on.”

The Michael Bay approach has become the principal way in which action scenes are shot. It isn’t absence of craft that leads to these aimless bouts. The filmmakers actively want the action to be hard, even impossible, to follow. Sometimes I think that this blurred bustle is there to secure a PG-13 rating; if you could really see the mayhem, we might be moving toward an R. But filmmakers don’t say that they’re self-censoring. They seem to think that making the action illegible is creative because it promotes realism.

Stallone explains why he scrambled up the fight scenes in The Expendables.

I don’t think many action scenes are shown from the character’s point of view. They are more from the director’s point of view. On Rambo, I thought the most economical and original way to shoot [the action] would be through Rambo’s eyes—if he were directing, what would his style be? But The Expendables is an ensemble picture, so it’s somewhat of a blend. I thought, ‘This is not supposed to hang in the Louvre.’ I wanted it to be disjointed and rough, not choreographed. If you really were filming a big battle with five cameras, [their footage] would not all flow together, so we set up the [cameras] to film the action we’d scripted and told the operators they were on their own. We said, ‘Do the best you can, and we’ll use the interesting shots from the characters’ perspectives.’”

Camera operator Vern Nobles describes shooting the action as “multi-camera craziness.”

You might point out that if somebody were really filming a big fight with five cameras, at least a couple of camera operators would be shot or punched silly. And presumably a few times we’d actually see other cameras.

Realism, as usual, is simply a fig leaf for doing what you want. Virtually any technique can be justified as realistic according to some conception of what’s important in the scene. If you shoot the action cogently, with all the moves evident, that’s realistic because it shows you what’s “really” happening. If you shoot it awkwardly, that presentation is “realistically” reflecting what a participant perceives or feels. If you shoot it as “chaos” (another description that Nobles applies to the Expendables action scenes)—well, action feels chaotic when you’re in it, right?

Forget the realist alibi. What do you want your sequence to do to the viewer? Do you want it to pass along an impression of bustle and flurry? Or do you want to make the viewer wince, recoil, even mildly reenact the movements of the players? Then follow the Hong Kong tradition. Yuen Woo-ping once told me that his goal was to make the viewer “feel the blow.” To convey the effort and strain, the impact and pain: that’s something worth doing.

It’s something that the blur-o-vision tussles lack, but even fights that are more carefully filmed are strangely unmoving. In Tomorrow Never Dies (1997), there’s a fistfight on a catwalk above a rotary press line. The presentation is more or less spatially unified, but it lacks drive because of certain creative choices. For instance, when Bond punches a security guard, the man simply drops out of the frame.

Where does he go? He doesn’t fall off the catwalk but seems to grab the railing, so maybe he’ll return for another go-round. But he doesn’t. As Bond falls back, another guard sneaks up on him. The framing and screen direction suggest that he’s approaching Bond from the front.

Actually, he’s sneaking up from the rear.

When Bond turns, we don’t see his punch.

In fact, we don’t see much of anything. Although the attacker is erect in one shot, he seems to be kneeling in the next, when Bond kicks him, somewhere below the frameline.

The attacker is standing again in the next shot, and he’s flung backward by the force of Bond’s unseen kick.

When the man returns, he tries to tackle Bond. At least, I think he does. The maneuver takes place, again, underneath the frameline.

At last we get a wider shot, but this serves mainly to align the fight with the conveyor belt below the men; guess who will fall?

More fighting, with punches and grappling blocked by the men’s bodies, culminates in Bond’s adversary falling into the print run.

Even here, however, we don’t really see what happens to the victim. He plunges through the river of newsprint and the machine starts belching.

Overall, we get a mild impression of what happened in the fight, but the action unfolds vaguely and is hardly stirring. Is this how you earn a PG-13?

The Hong Kong way

Righting Wrongs (1986).

While revising Planet Hong Kong for its web edition, I’ve been revisiting classic Hong Kong action scenes. In 1997-98, when the book was written, I had to rely on laserdiscs, but since then I’ve been able to look at more 35mm prints. (DVDs usually don’t help answer the sort of questions I’m asking, for reasons reviewed here.) Now I have a chance to put some thoughts about these movies online, in this blog and in the upcoming digital update of the book. As a start, here’s a recipe drawn from the best of Hong Kong fury.

First, go for clarity in every way. Not murky earth-toned sets but brightly colored and sharply lit ones; even an alley can dazzle. Put the camera on a tripod; pan if you must, but save your dolly moves for simple emphasis. No handheld.

Second, aim for precision. Stallone’s comments imply that a cameraman captures a preexisting fight, snatching an “interesting” shot here or there. But that’s not the case. Movie action is choreographed and the framing is calibrated to that. The gestures should be legible, favoring crisp and staccato movement, while the image’s composition aims to convey the action cleanly. It’s a pity that the haphazard framing of Stallone and his cameramen have ruined the choreography of Cory Yuen Kwai, Jet Li’s action designer (and a fine director in his own right).

Third, establish a rhythm. This involves not only building the fight. It also involves synchronizing the pace of characters’ movements with that of the cutting. On the whole, the old rule applies: More distant shots should be held longer than closer ones. This doesn’t mean you can’t use fast cutting, only that your fast cutting can be more finely judged when you take shot scale, composition, and speed of movement into account.

Rhythm means sensing a pulse, and for that you need slight pauses. So don’t cut away to something else before a punch or kick is completed. Let the arc of movement, itself perhaps stretched over several shots, come to a point of rest, if only for a couple of frames.

Fourth—and here is where realism is most explicitly abandoned—amplify the expressive qualities of the action. If movement is zigzag or springy or oscillating, stress that. Give emotional qualities not only to facial expressions but also to postures and combat moves. American heroes just grimace while their bodies remain inexpressive, lumpish. The hard guys in The Expendables might as well be made of granite. But in contrast your fighters needn’t wave their arms wildly. Just concentrate energy and emotion in the action. If the hero attacks, let him become as focused as a javelin. If your heroine falls, don’t let her just drop out of frame: Let her land with a thwack, preferably on the spine or neck, and let her body’s recoil send a spasm through the spectator too.

Hong Kong cinema supports Sergei Eisenstein’s belief that expressive human action is “infectious.” He thought that if physical action onscreen is imbued with vivid force it can arouse sympathetic echoes in the spectator’s own body. After a great action scene, such as in many Chang Cheh and Lau Kar-leung films of the 1970s, or in Yuen Kwai’s Righting Wrongs, when a tough guy gets a spittoon in the face, the viewer feels trembling and tired, but in a good way.

Glass story

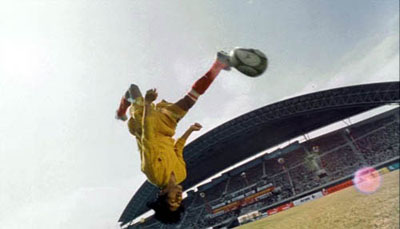

Jackie Chan has become such a beaming, easygoing star that we forget that he was an excellent director of brutal fight scenes. He proved adept at filling anamorphic compositions with dynamic movement, as well as plucking out items of a set and sweeping them into the action. (See the parlor fight in Young Master, 1980, or the shenanigans in the rope factory in Miracles/ Mr. Canton and Lady Rose, 1989). In Police Story (1985), Jackie is trying to rescue Salina and save all the computer records in her briefcase. Koo’s gang is determined to stop him. The fight moves through different areas of a shopping mall.

In each of these locales, Jackie plays a suite of variations on what you can do with escalators, staircases, and, most memorably, glass. I can’t do justice to all the skirmishes, but consider some instances of how he stages and cuts the action for an impact that American movies seldom achieve.

The variations get steadily more elaborate. Early in the sequence, Jackie flings one thug, achingly, across the bottom handrails of an escalator.

The shot could hardly be more legible. You see everything. Next, Jackie is grabbed from the rear.

Naturally he has to flip his attacker down to the floor below, rendered in two dynamic shots from directly below and above.

Interestingly, the shots are so clearly composed (even with the fancy mirror effect in the second) that they can be very brief: 26 frames and 16 frames. Down at the bottom, the unfortunate fellow smashes through a display and lands straight on his spine. Unlike the security guards in Tomorrow Never Dies, this thug gets a little commiseration as he rolls over groaning. As in any fight sequences, disposable thugs may come back into action, but at least we’ll clearly see the fates of those who are put permanently out of commission.

After this burst of action Jackie provides a pause as he abruptly looks up in search of Salina.

What else can you do with escalators? How about tossing the next thug down the slim gap between two of them?

In a nice touch, we hear a long squeak as he slides down the trough.

Tomorrow Never Dies sets up its conveyor-belt climax straightforwardly, but Jackie’s choreography is more surprising. Audacious and imaginative as the stunts are, however, they are framed and cut in a way that makes the action clear and precise. Through cinematic choices Chan builds up an infectious arousal. This stuff hurts.

After a set-to in a hallway, Jackie pursues the gang into an area filled with display cases. He takes on the men ferociously, and sets them smashing through the vitrines in another string of variations. Jackie slams down a mirror on one thug, swings another into a display, and sends one spinning through a window. Each shot, of course, is of diagrammatic simplicity, all the better to amplify the expressive dimension and key up the viewer. You can’t watch shots of men hurled into layers of glass without feeling a few palpitations.

Nearly every shot is bound tightly to the next. What will occupy shot B is launched on the fringes of shot A, sometimes for only a few frames. The string of matches on action creates a fluid continuity quite different from the choppiness we often find in American sequences.

A good instance occurs after Jackie has been pinned under a toppled shelf. In a medium close-up, the gang leader orders his thug into action; behind him the plaid-coated thug moves left.

In long shot, with Jackie at a disadvantage, the thug continues his movement in the background as he grabs a heavy statuette.

In a medium-shot, Mr. Plaid Jacket lifts the statue, but as he moves aside he reveals Salina rushing toward him in the background. Look quick: She appears in the fifteenth frame, and is gone within another fifteen.

We can only glimpse Salina passing behind the thug, but the next shot shows her clearly: running, baseball bat in hand, toward him. The trajectory could not be clearer, and she swings the bat directly through the vitrine.

The force of the action is multiplied by the simplest cut possible: an axial enlargement, with the action slightly repeated and slowed. The first shot of Salina’s swing lasts seventeen frames, the second exactly twice as long. The arithmetic of the cutting extends the action’s beat.

Bursts of glass form the dominant, painful motif of this part of the sequence. (Jackie’s crew suggested he call the film Glass Story.) The shifting dynamic of the fight is rendered through close encounters of the splintery kind. But these are differentiated. Long shots portray the torments of the gang, but Jackie’s first encounter with glass is treated in one simple close shot, just a second long, that usually makes audiences flinch.

Jackie is attacked by the gang leader and he shoves Salina out of the way.

The leader springs forward to whack Jackie with the briefcase.

Cut to the opposite angle, a tight shot of Jackie.

The briefcase continues to be swung, and Jackie’s head smashes the windowpane.

Jackie bounces off the glass and grimaces in agony.

The proximity of the glass shards to his eyes probably triggers some primal revulsion in us, but this is only part of the image’s force. The whole shot lasts only 28 frames. I think that part of its percussive impact comes from the fact that at the start we don’t have time to register that the pane is there. (There are only seven frames before Jackie hits.) When the glass bursts, it’s as startling as if the screen surface has cracked as well, and this amplifies the painful impact of the blow.

For a time Jackie is at the gang’s mercy. But he makes a comeback, and eventually in a kind of summary of his other maneuvers he will bash the leader, body and head, through two glass cases. This phase of the scene concludes with Jackie running Mr. Plaid through a series of cases at the point of a motorcycle. Both crescendos are filmed in clear, smoothly-cut shots—and long shots at that.

We may wince for the fate of these gangsters, but we shuddered when we saw Jackie’s face knocked through a window. Soon Jackie will be flipping the leader down an escalator, a sort of envoi to the scene’s first phase, and he will be sliding down a three-story light pole to catch up with boss Koo himself.

To use Stallone’s comparison, I’d happily hang this splendid sequence in the Louvre.

But what sort of MPAA rating would it receive today? The painful physicality on display is given a staccato force through the framing and cutting. And don’t call it cartoonish. It’s Bond who’s cartoonish, with his unflappable ease and perfectly functioning gadgets and defiance of the laws of gravity and those fights he wins without suffering a scratch. Jackie shows us the sweat. He and his victims fall with painful awkwardness, he gets gashed and bruised, and he’s all too vulnerable to physics (or at least Hong Kong physics). Bond wins through debonair resourcefulness and a lot of luck. Jackie wins by refusing to lose.

He refuses to lose the audience too. In Police Story Jackie’s manic urge to make the scene maximally gripping is itself a little scary. Nonetheless, when a director isn’t afraid of tapping the real power of movies, a fight scene can give us an adrenalin transfusion. Who needs 3-D? Maybe only weak directors.

For other discussions of Hong Kong action scenes, see my “Aesthetics in Action: Kung-Fu, Gunplay, and Cinematic Expression” and “Richness through Imperfection: King Hu and the Glimpse” in Poetics of Cinema. There are some other examples in my online essay on Shaw Brothers. My most ambitious efforts in this direction are in Planet Hong Kong, where I take up the issue of rhythm in more detail than I can here. Alas, many contemporary Hong Kong action scenes have learned bad habits from Hollywood. I’ll talk about the decline of crisp fight staging in the new edition of PHK, due online in early December.

Todd McCarthy’s 1998 review of Armageddon is here. Peter DeBruge’s review of The Expendables is here. Both may lurk behind a paywall. The coverage of The Expendables I mention is Michael Goldman, “War Horses,” American Cinematographer 91, 9 (November 2010), 52-56. The pilot online issue is here.

The Dragon Dynasty version of Police Story includes Bey Logan’s conversation with Brett Ratner. During the commentary, Ratner notes that Jackie holds his shots longer than would an American director, who would be likely to cut on every punch. Incidentally, I’ve found many DD releases of Hong Kong films to be superior in quality to other DVD versions, and Logan’s commentaries are information-packed. His book Hong Kong Action Cinema remains a fine piece of work.

The images from Tomorrow Never Dies are taken from DVD, with all the drawbacks of that format for close analysis. But I don’t think my conclusions would vary if I worked from 35mm. The Police Story frames are analog frame enlargements from a 35mm print and allow accurate frame-by-frame analysis. Even then, Jackie’s pacing is so fast that blurring is inevitable. Thanks to Heather Heckman for her assistance in turning my slides into digital files.

PS 17 September 2010: I forgot to mention that Matt Zoller Seitz has provided two of the most discerning (and hilarious) critiques of the Michael Bay High Rococo Action Style, here and here.

Young Master.

No coincidence, no story

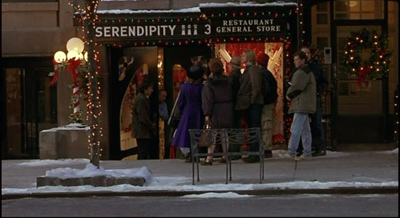

Serendipity.

DB here:

I’ve been thinking about coincidences lately. Watching Hong Kong movies can do that to you.

Hong Kong vs. Hollywood?

Initial D; I Corrupt All Cops.

In Initial D (2005, Andrew Lau Wai-keung and Alan Mak Siu-fai, script by Felix Chong Man-keung), the protagonist Takumi is dazedly in love with the seductive schoolgirl Natsuki. Takumi’s pal Itsuki is out with another girl when he spots Natsuki riding out of a “love hotel” with an older man. Itsuki tells his pal. This leads to a major crisis, in which Takumi’s faith in Natsuki is shaken.

Then there’s I Corrupt All Cops (2009) from the indefatigable writer-director-producer-actor Wong Jing. (Many wish he were far more fatigable.) Unicorn, a corrupt, brutal police officer, has just been savagely beaten by gamblers who once were his allies. He staggers to a street stall and nearly collapses, spitting blood into his congee. Then he glimpses his girlfriend getting out of a rich man’s car. In the next scene, when he visits her apartment, he finds his boss, the even more corrupt cop Lak, in her bed. His realization that he can trust no one pushes him to join the police anti-corruption unit.

True, the coincidences play different roles in the two movies. In Initial D, there might be an innocent explanation for Natsuki’s visit to the hotel. Perhaps Takumi’s friend even mistook another girl for her. So we may be inclined to suspend our judgment and wait for more information about whether she’s actually being unfaithful. In I Corrupt All Cops, Unicorn’s suspicions about his girlfriend’s disloyalty are immediately confirmed; instead of suspense, we get surprise, in the form of the revelation of who her lover is.

But in each case, a major plot movement is triggered by sheer accident. Itsuki wasn’t spying on Natsugi’s assignation; he was trying to talk his date into the love hotel. Unicorn wasn’t suspicious of his girlfriend, he just happened to be across the street when she came home. Each coincidence is also a matter of timing: Had either man come a few minutes later to the location, he wouldn’t have learned the big secret. In retrospect, we are likely to think that the screenplays of Inital D and I Corrupt All Cops are using chance rather than causality to move their action forward.

Granted, Hong Kong films are generally weak in plot construction. Even the lauded films of Wong Kar-wai are built out of casual encounters and unpredictable turns of events. The old Chinese maxim “No coincidence, no story” might seem to give accidental revelations a high place in this cinema. But Hong Kong films aren’t outstanding offenders. When you start to look, you find that films in different traditions are no less committed to coincidence. After all, Rick in Casablanca notices the vast implausibility of what’s just happened: “Of all the gin joints in all the towns in all the world, she walks into mine.”

One precept of Hollywood screenwriting has been that coincidences are permissible when you’re setting up the narrative. Indeed, they’re often necessary: Circumstances have to come together in some way to launch an extended action. A sudden rainstom brings boy and girl together under the same awning, creating the cute meet, and things can build from there.

But, the Hollywood wisdom goes, don’t use a coincidence to develop or resolve the plot. Consider another Hong Kong film, Infernal Affairs (2006, directed by Lau and Mak, with script by Chong). Chan the undercover cop has come in from the cold. While officer Lau is out of his office, Chan is poking idly around Lau’s desk. There he finds the envelope on which Chan himself once scribbled a correction.

That envelope was in the hands of the gang that Chan joined. If Lau has that envelope, he must be the triad mole in the police force. This recognition triggers the film’s climax: Chan flees police headquarters and sets out to unmask Lau’s treachery.

You would think that if Hollywood filmmakers were anxious to avoid such a timely accident, the Infernal Affairs remake known as The Departed (directed by Martin Scorsese, script by William Monahan) would find another way for Billy Costigan to discover that Colin Sullivan is the mole. But no. Billy notices the telltale envelope sticking out from a pile of papers on Sullivan’s desk.

The different ways the two films drive the discovery home to the audience merit a closer look than I can spare here. My point is that the handy coincidence of the police mole leaving this damning clue for his adversary to find is used without apology in the Hollywood movie. And like its counterpart, the scene sets off the movie’s climax. You could even argue that Infernal Affairs supports its revelation a little better. Billy accidentally glimpses the crucial envelope, but Chan is actively browsing Lau’s desk, perhaps because after years spent among triads he doesn’t trust anyone .

So you have to wonder. Maybe filmmakers in many traditions have accepted the Chinese maxim. Moreover, contrivance of this sort doesn’t seem to damage a film’s reputation. (Many critics considered The Departed one of the very best US films of 2006.) More generally, we seldom feel such coincidences to be arbitrary or forced. Maybe screenwriters and directors have found ways to mask the coincidental tenor of such scenes.

As with our earlier Inception entry, we’re in the realm of motivation.

The roots of coincidence

Most story actions result from characters’ choices, purposes, reactions, plans, and the like. These factors create patterns of cause and effect. Chan/Billy didn’t just mosey into Lau/ Colin’s office: He came in because he thought it was safe to break his cover. We accordingly worry for him because we know, as he doesn’t, that he’s far from safe.

Everyone seems agreed that a plot can’t replace all causal connections with a string of coincidences. If everything happens by convenient accident, then we can’t form any expectations about what will happen next. And without expectations, our cognitive and emotional engagement with the story is likely to be slight. Moreover, designing a story packed with coincidences isn’t that hard. Children do it all the time. But most artistic traditions thrive on their constraints. If anything at all can happen to advance or conclude your plot, you’re playing tennis without a net. The interesting challenge for a storyteller in traditional forms is to create a pattern of incidents that arouses our curiosity, builds up suspense, and presents surprises that turn out to be, in retrospect, cunningly prepared for—all the while playing on our emotions.

Yet, and again: No coincidence, no story. Sometimes, the plot’s forward momentum needs encounters and discoveries not planned by the characters. So how can these convenient accidents be made to serve narrative craft?

Well, what is a coincidence anyway? At the least, it’s a matter of converging incidents, as the name implies; but surely it involves more.

I wake up one morning and ask, “I wonder what my sisters are up to? I haven’t heard from them in a while.” Nothing important is happening in the family, no health crises or upcoming reunions. I just wonder how the girls are. So I reach for the phone, but before I can dial I get a call from Diane (the Texas sister). I say, “What a coincidence! I was just going to call you.”

This sort of thing happens. But not all the time. Not even most of the time. The thousands of things that flit through our day almost never match up so nicely. And we don’t notice it when they don’t match up, because we don’t expect them to. The non-coincidences of everyday life go unregistered because they’re so pervasive.

On those rare occasions when things do sync up, we notice. In The Evolution of God, Robert Wright puts it well:

It makes sense that human brains would naturally seize on strange, surprising things, since the predictable things have already been absorbed into the expectations that guide them through the world; news of the strange and surprising may signal that some amendment of our expectations is warranted.

We usually attribute such coincidences to chance. But humans aren’t very good at thinking about chance. If the coincidence seems meaningful, as many do, we’re always tempted to consider it the result of some secret force. Did I send out invisible thought-waves that Diane somehow picked up? Did fate, or God, make her call me? In general, when we notice patterns, we look for causes. The phone-call convergence is a pretty minimal pattern, but even there we might be tempted to find a cause.

I hang up on Diane and the phone rings immediately. It’s Darlene (the peripatetic sister). “I was just trying to call you, David, but the line was busy.” This is getting weird. The pattern heightens and may prompt a stronger impulse to search for causes. Do we three siblings mind-meld in some mysterious fashion? (If so, though, why do we need phones?) It’s just a coincidence, highly improbable but, out of all the times we three think about one another and make phone calls, not impossible.

I believe that narrative artists in all media are practical psychologists. They trigger and exploit and heighten our ordinary ways of making sense of the world. Philosophers and statisticians have sophisticated ways of thinking about chance, but they needed special training to get beyond our folk psychology. Artists take us as we are.

Stories can use coincidences because we accept them. They are the sorts of things that sometimes happen, and so, as Aristotle argued, they are fit subjects for plot-making.

The poet’s task is to speak not of events which have occurred, but of the kind of events which could occur, and are possible by the standards of probability or necessity (Poetics, Chapter 9).

Here Aristotle points to two sorts of possible events. There are events that we expect to happen as a necessary result of earlier events; this corresponds to some notion of causality. Then there are events that are merely probable—things that are likely to happen.

But how likely is my call from Diane and the followup from Darlene? Aren’t these examples of what Aristotle dismisses as “the arbitrary and fortuitous”? Not necessarily, because for Aristotle too the storyteller is a practical psychologist. Things that seem unlikely, he says, can be motivated by reference to people’s beliefs or to the fact that improbable things are likely to happen occasionally.

Irrationalities should be referred to “what people say,” or shown not to be irrational (since it is likely that some things should occur contrary to likelihood) (Poetics, Chapter 25).

In sum, how do you motivate a coincidence? Aristotle recommends two tactics, which I could use if I were writing a story featuring the felicitous phone calls. People say that members of a family have a special affinity that can cross time and space. And anyhow, stranger things have happened.

Narrative norms

SPL.

Aristotle suggests a third motivational tactic as well. He says that unlikely things may be resolved “by reference to the requirements of poetry.” Poetry here refers to any verbal artform, just as poet refers to the maker of literary works in general. So what are the “requirements” of storytelling?

Most minimally, a plot needs an inciting incident. If I were a fictional character, my lucky phone calls might kick off a plot in which my sisters and I, feeling a new and mysterious bond, set out on road trips to meet somewhere. The telephone contrivance would correspond to the Hollywood dictum that coincidences are permissible at the outset of the plot.

Many commentators on Aristotle take his mention of poetic “requirements” to involve more specific conventions, especially those of different genres. We’ve long known that certain kinds of art works permit things that would be forbidden in other kinds. A children’s movie is unlikely to show chainsaw dismemberings, unless Eli Roth has been given a producing deal at Pixar. This idea of genre fitness or decorum has implications for coincidences too.

Clearly, coincidences flourish in comedy. The innocent young man trapped in a lady’s boudoir will have to hide under the bed because her husband bursts in at an awkward moment. In the long chase sequence through old Hong Kong in Project A (1983), Jackie Chan keeps bumping into his superior officer. Sometimes Jackie is set back by the encounter, but once the officer inadvertently rescues him. David Lodge writes: “Audiences of comedy will accept an improbable coincidence for the sake of the fun it generates.” His novel Small World culminates in a pile-up of coincidences in which an airline check-in clerk happens to give the heroine a copy of The Faerie Queene at the precise moment she needs to check a literary reference.

This is all highly implausible, but it seemed to me that by this stage of the novel it was almost a case of the more coincidences the merrier, provided they did not defy common sense, and the idea of someone wanting information about a classic Renaissance poem getting it from an airline Information desk was so piquant that the audience would be ready to suspend their disbelief.

Melodrama is another genre that relies on coincidences, particularly those that bring bad luck. (Think of Rock Hudson’s cliff-edge fall in All that Heaven Allows.) Likewise, I think that the revelations of the incriminating envelopes in Infernal Affairs and The Departed are partly motivated by genre conventions. In undercover tales, the detectives have to be alert for any physical items that might betray them or offer clues. So the envelopes are something that the hypersensitive narc could plausibly fasten onto. (Why the envelopes are left lying around in the first place is another part of the story, which I’ll come to.) Similarly, Initial D is partly a teenage romance, and we know that such films require an obstacle to happiness; that’s what Itsuki’s accidental discovery provides.

There’s another “requirement” of poetic art that can motivate coincidence, and it cuts across different genres. In Wilson Yip Wai-sun’s SPL (2005), a brutal martial-arts fight in a nightclub ends with the gangland chief Wong Po hurling Inspector Ma through a window far above the street.

Down below in a waiting car are Wong Po’s wife and baby son, the only things in life he loves.

Care to have a guess where Ma lands?

This is a coincidence motivated by poetic justice: The brutal Wong Po has inadvertently killed his wife and child. Serves him right!

As we might expect, Aristotle anticipated poetic justice too. He remarked that there was a special sense of fitness when the statue of a murdered man toppled over on his killer.

Three dimensions of narrative

Casablanca.

In an essay in Poetics of Cinema I argued that we can think of any narrative as having three dimensions: the story world, the macrostructure of the plot, and the narration–the flow of information as it’s presented, moment by moment, in the film. Each of these dimensions can motivate coincidence, and each answers to what Aristotle calls “requirements” specific to narrative art.

Say you want two characters to meet without making a rendezvous. One way is to establish that each has a routine. Jack stops for coffee at Starbuck’s every morning on the way to work; so does Jill. Sooner or later, it’s plausible that they will run into each other. The appeal to routine is probably behind the unlucky coincidence in I Corrupt All Cops. After being beaten, Unicorn staggers to the food stall across from his girlfriend’s apartment house–evidently on his way to call on her.

Another sort of story-world motivation involves characterization. In Initial D, it’s not implausible that the randy Itsuki would be hanging around outside a love hotel. Given his personality, he’s more likely to see Takumi there than other, more upright characters would be. In Infernal Affairs, Lau is a cautious mole, but he has no reason to hide the telltale dossier because he thinks it would be meaningless to anyone else. (Lau can’t know that Chan is the one who scribbled the corrected spelling on the envelope.) Lau’s studied nonchalance lets him stack papers on his desk without concern that this one is particularly revelatory.

Coincidence can also be motivated by the overall plot structure. If you start your film by alternating scenes showing two characters living their lives separately, you make it easier for your audience to accept what might otherwise seem a chance meeting between them later. After all, if they aren’t going to have some interaction, why are they both in this story? Sleepless in Seattle provides a clear-cut instance, although here the conventions of the romantic comedy genre also insist that the couple will get together. (Vera Chytilová’s Something Different of 1963 shrewdly defeats the expectation aroused by this sort of alternating construction.)

Likewise, a flashback structure can motivate coincidences. If we’ve seen the outcome of an action, even implausible events leading up to it can seem more natural. At the start of The Big Clock (1945) we see a hunted man hiding in a vast clock mechanism that surmounts a skyscraper.

In a long flashback, we see what led up to Stroud’s plight. Fired from his magazine job, he meets up with a blonde woman who takes him bar-hopping. They wind up in her apartment, but she hurries him out just as his boss Janoth comes in. Stroud watches Janoth go into the woman’s apartment.

The encounter isn’t wholly accidental. We know, as Stroud does not, that the woman is Janoth’s mistress, and she knows Janoth is coming to visit her. Nonetheless, what happens next leads to Stroud’s being fingered for murder. Stroud has pretty bad luck, but the opening frame story of his flight retroactively motivates his presence at the crime scene; we wouldn’t have the clock scene unless it proceeded, as Aristotle might say, by necessity from something pretty serious. The order of presentation coaxes us to accept whatever led up to the opening situation.

The story world and the plot macrostructure can do only so much. Sometimes coincidences need more fine-grained motivation. Here’s where narration, the patterned flow of information, comes in. If a cowardly cowboy is just about to leave the saloon when the bullying gunfighter enters, it can seem less stage-managed if we show, beforehand, the gunfighter riding into town with his minions. It doesn’t make the encounter more plausible in the story world, but it prepares us to find it more plausible: the two paths seem to converge. Here crosscutting accomplishes on the small scale what alternating scenes can do for macrostructure.

An even simpler tactic is to have someone announce that what’s happening is extremely unlikely. Lodge points out the audacity of Henry James in The Ambassadors when he presents a major moment through a character who reflects, “It was too prodigious, a chance in a million. . . ” This is the equivalent of Rick’s comment about Ilsa dropping into his gin joint. A frank admission of a coincidence can pull you through.

It was meant to be

Many of these motivating factors can work together with a more sweeping one. Recall that we’re sometimes tempted to consider everyday coincidence the result, or sign, of forces larger than we can comprehend–God, karma, fate, the Sibling Affinity Frequency. A narrative can motivate its coincidences by suggesting that they are working out an elusive but powerful pattern. Somehow, coincidence is just the hand of destiny. The French film known in English as Happenstance (2000) provides an example, but so does Serendipity (2001).

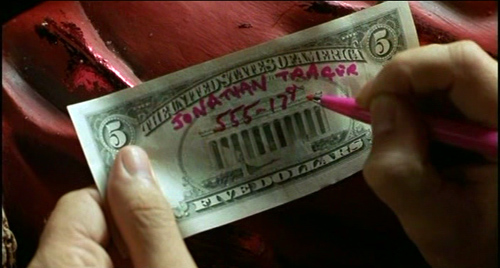

Jonathan and Sara meet cute in Manhattan, but mishaps separate them. They never learn each other’s identity. Years later, Sara is in San Francisco living with a musician, while Jonathan is about to get married. Vaguely dissatisfied and fretful, Sara returns to Manhattan to find Jonathan. Meanwhile, just before his marriage, he sets out to find her. Each one thinks that recapturing the love that flared up in one magical night would be worth one last effort.

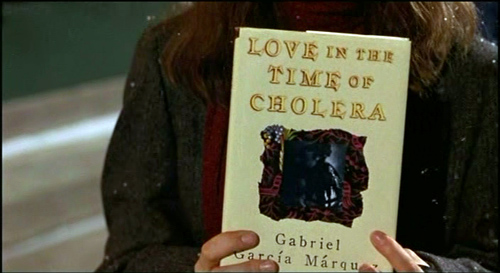

How do they find one another? Clues, plus coincidences. Jonathan starts to track Sara through a sales receipt for gloves she bought when they first bumped into each other. Sara returns to the Waldorf and visits “their” café in hope of finding some connection to Jonathan. But a lot of luck is involved too. Jonathan confirms Sara’s location thanks to her inscription in a used copy of Love in the Time of Cholera–a copy that his fiancée gives him, no less. By chance she bought Sara’s copy. Correspondingly, Sara finds the $5 bill Jonathan signed years before in her friend’s purse. Her friend got it as change at the café. The characters take purposive action, but they achieve their goals through coincidences.

These coincidences are simply outrageous. How can we motivate them? At the beginning of their magical night Sara announces that she believes that happy accidents are in fact controlled by fate. If she and Jonathan are meant to be together, things will arrange themselves the right way. She tells him this as they have coffee in her favorite café, Serendipity.

So Sara mounts some tests of their cosmic compatibility. She insists they leave the café separately: if they’re destined to remeet they will. Jonathan leaves his scarf behind, and she finds it, so they’re back together. She writes her contact information on a scrap of paper, but it blows away. “Fate’s telling us to back off,” Sara warns. Jonathan writes his phone number on the fiver, but she then pays for something with it, saying that if it returns to her, she’ll call him. In exchange, she’ll write her information in the Márquez novel and give it to a used bookshop; if he finds it, he can call her. Finally, at the Waldorf Astoria, each one is to get in a separate elevator car, pick a floor, and see if they’re in synch. It’s this test that leads him, through problems of timing, to lose her.

What motivates the cascade of coincidences, then, is the film’s starkly announced theme. In love, favorable coincidence is just serendipity; the film puts its operating procedure in Sarah’s mouth. To make your coincidences seem plausible, then, make your movie explicitly about how coincidences can be read as destiny.

But the theme doesn’t work on its own. Several of our other principles of motivation help out. For one thing we have Aristotle’s notion of common opinion: “What people say” about true love is that a couple is somehow meant for each other. In addition, of course, this is a romantic comedy, a kind of film that depends on separating and uniting lovers. We’d be very surprised, not to say disappointed, if these two didn’t wind up together. Genre helps motivate the way coincidences help out the couple.

Perhaps most interestingly, the “requirements of art” in Hollywood dramaturgy include a symmetrical play with motifs and character traits. Each lover is given a token—$5 bill, Márquez novel—and certain locales gain significance through repetition (Bloomingdale’s, the Waldorf, Serendipity, the skating rink). At the start of the film, Sara is the romantic, while Jonathan is more pragmatic. After a few years as a psychotherapist, however, she no longer trusts in fate. But by searching for her, Jonathan becomes a passionate believer in signs, reading everything around him as a possible trace of her presence. His pursuit of a love that defies likelihood moves his friend, the journalist Dean, to write a hypothetical obituary:

Even in certain defeat the courageous Trager secretly clung to the belief that life is not merely a series of meaningless accidents or coincidences. Uh-uh. But rather it’s a tapestry of events that culminate in an exquisite, sublime plan.

That plan is worked out through a traditional plot symmetry. Sara had found Jonathan’s scarf in the café at the start. At the climax, he discovers her jacket on a bench overlooking the ice rink where they shared their first date. (She had gone back there in a nostalgic mood earlier in the day.) Now, coming back for her jacket, she reunites with Jonathan. Hollywood’s use of tokens and props to develop the drama fits nicely with the theme of fate’s good offices. You could say that the vicissitudes of destiny are recruited to motivate some principles of classical plot construction.

Time out

You may dislike all the films I’m mentioning (Serendipity?! That’s a movie for wimps!). But my purpose here isn’t evaluative. I want to explore some principles that are used to make stories hang together, more or less. The same principles are present in what we sometimes call art films, from Bicycle Thieves to The Headless Woman. Coincidences abound in these movies, often motivated as the randomness of life, or n-degrees-of-separation, or mysterious larger forces that create correspondences (Paris nous appartient, the Three Colors trilogy of Kieslowski). Appeal to realism, to folk psychology, to genre, to thematic significance, and to formal unity can be found in virtually all narrative cinema. Here as elsewhere, I’m just trying to make such principles explicit and study how they work.

In thinking about those principles, I’m struck by one more way in which narratives need coincidences. What makes a story intriguing, or even worth paying attention to?

Here’s a story. I got up this morning, had breakfast with Kristin, went to school to take some frame enlargements from Hong Kong films, and dropped off the slides at a lab before coming home. Technically, it’s a story, but you yawned halfway through. To be engaging, stories need a remarkable situation or twist—a lover betrayed, a man pursued for a crime he didn’t commit, a cop discovering that his savior is his worst enemy, people who meet and fall in love and then lose one another.

We need, in short, something out of the ordinary. Coincidences, popping out from the bland backdrop of everyday life, can provide an uncommon event. At the start of a plot, they launch the action. At intervals, and with the proper motivation, they can be invoked if they liven things up. The effect may go back to the strangeness that Robert Wright suggests that we’re always on the lookout for.

Granted, the effect of motivation is to make coincidences seem less strange than they might otherwise seem. Most of these factors work to give the coincidences a sort of causal boost. Itsuki sees Natsuki because he’s at the love hotel, Chan/ Billy notices the envelope because he’s an alert cop, Jonathan and Sara get together again because they follow up clues and try really hard and anyhow an unseen hand (causally) shapes their fate, and so on. The coincidences are often covered by a causal alibi. That suggests that what’s most coincidental in these situations is timing.

Most movie coincidences run on tight schedules. A few moments later, Itsuki wouldn’t have seen Natsuki leave the love hotel; Unicorn wouldn’t have caught his wife with his boss; Chan/ Billy wouldn’t have found the telltale envelope; and so on. As the film unrolls, we want our extraordinary events tied to close shaves, barely missed messages, and revelations taking place under a ticking clock.

Every moment in filmic storytelling seems to bristle with possibilities of convergence and revelation. The sort of actions that make stories interesting are even more gripping if they take place under time pressure. Very often, if a key event had happened slightly earlier or later, there would have been no coincidence. And movies, unrolling at a pace to which we all submit, are well-suited to arouse our interest with turns of events that might, just barely, have been very different. Perhaps we accept the power of good or bad timing because, to recall Aristotle, “people often think” things like this: If I had missed that train, I would never have met my soul mate. . . .

Clearly, though, timing is a tale for another occasion.

My thanks to Ben Brewster for discussing these ideas with me and reminding me of the Chinese adage. That precept is briefly discussed in Kam-ming Wong, “‘No Coincidence, No Story’: The Esthetics of Serendipity in Chinese Fiction,” International Readings in Theory, History and Philosophy of Culture (St. Petersburg, Russia: EIDOS, 2003), Vol.16, 180-97.

My references to the Poetics come from Stephen Halliwell’s edition, The Poetics of Aristotle: Translation and Commentary (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1987), pp. 40, 42, and 63. My extracts from David Lodge’s The Art of Fiction (New York: Viking, 1993) are from his section on coincidence, pp. 149-153.

Hilary P. Dannenberg’s book, Coincidence and Counterfactuality: Plotting Time and Space in Narrative Fiction (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2008) includes many intriguing ideas about coincidence. Her focus is the “coincidence plot” in which people realize they’re related to one another. Some of her arguments are presented in more compact form in her article, “A Poetics of Coincidence in Narrative Fiction,” Poetics Today 25: 3 (Fall 2004), pp. 399-436.

P.S. 31 September: In a study of The Pledge, film scholar Gary Bettinson has a valuable discussion of how coincidence can be motivated to resolve a plot. It’s available here.

Serendipity.

Hopscotching through history

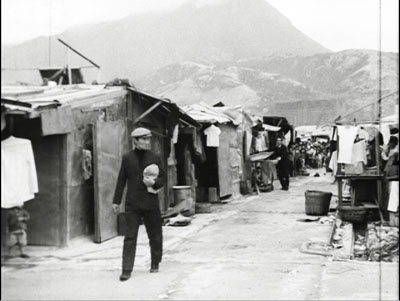

Temple Street, Hong Kong.

DB here:

Thanks to the Film Festival and screenings at the Film Archive, I’ve skipped gratefully through nearly a hundred years of local film history.

The Roast Duck legend, cooked at last?

First things, or rather first films, first. Last year local authorities declared 2009 to be the centenary of Hong Kong cinema. The long-standing claim (repeated in my Planet Hong Kong) was that To Steal a Roast Duck, aka The Trip of the Roast Duck, was made in 1909 and was the first locally produced fiction film. The controversy arose because the claim was based on later recollections of filmmakers. No fiction films from that era survived. We had no contemporary evidence that the Roast Duck was made in that year or that it was the first anything. Perhaps it wasn’t even made at all? In a blog entry last year, I summed up the arguments.

Now, thanks to the persistence of Frank Bren and Law Kar, we can come to more reliable conclusions. At a conference in December, scholars from around the world gathered at the Hong Kong Film Archive to discuss early Chinese cinema. One of the results was further revelations about the territory’s first film.

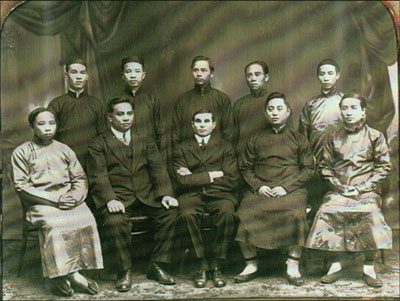

We know that at some point the Ukrainian-American entrepreneur Benjamin Brodsky came to Hong Kong and set up a film unit. (The picture above shows him surrounded by nine Chinese co-directors of the company he founded in November 1914.) An earlier Brodsky company made Roast Duck, among other films. But when?

At the conference Law Kar announced the discovery of a 1914 Moving Picture World interview with Roland Van Velzer, a photographer recruited from New York by Brodsky. During his stay in what he called “that queer land” of Hong Kong, Van Velzer shot four films in 1914.

We did a first native drama, entitled “The Defamation of Choung Chow.” With my experience and guidance the picture turned out well and when shown in public proved to be a wonderful drawing card. . . . The reason of its great popularity was because it was a Chinese piece entirely. . . . We made three other subjects during my stay there. These were: “The Haunted Pot,” The Sanpan Man’s Dream” and “The Trip of the Roast Duck,” the latter a rough “chase” picture. All of these pictures had phenomenal runs at the native theaters.

According to Van Velzer, then, the first film, made and shown in 1914, was what is now known as Chuang Tzi Tests His Wife. Roast Duck was evidently the fourth film made by the team that year.

Brodsky is significant not merely because he supported talent in producing the colony’s first fictional films. He also made long documentaries about China and Japan that played in the US. He seems to have been a colorful guy. In his barnstorming circus days, he once purged a lion with castor oil. Full details are here in an article by Bren and Kar. In the meantime, we can look forward to a more plausible centenary of Hong Kong film in 2014.

Social conscience, modern stylings

The Story of a Discharged Prisoner.

Hop ahead to the 1960s. Although the local language of Hong Kong is Cantonese, movies in Mandarin rule the market, with Shaw Brothers providing gaudily colored costume pictures, musicals, romantic dramas and comedies, and of course rather violent swordplay exercises. By contrast films made by Cantonese companies under tiny budgets look threadbare. Yet a few filmmakers tried to make Cantonese cinema more vigorous and innovative, and the most influential was Patrick Lung Kong.

Lung Kong was born in 1935, and by the time he was thirty he had performed in virtually every production role, from screenwriting and producing to publicity and distribution. Well-known as an actor since 1958, he graduated to directing in1966 with Prince of Broadcasters. His second film, The Story of a Discharged Prisoner (1967) was a landmark in local cinema, expressing sympathy for an ex-convict who tries to avoid being pulled back into crime. Lung Kong goes on to make many of the socially critical films of the period: Teddy Girls (1969), Hiroshima 28 (1974), and Mitra (1976). He ceased directing in 1981 but continued to work as an actor and distributor. He now lives in New York City, but he came back for the retrospective that the Film Archive has mounted.

I had seen some Lung Kong films in earlier visits to Hong Kong, but the retrospective will allow us to assess his career as a whole. Virtually none of his films are available on DVD, and none, as far as I know, with English subtitles. Particularly important, apart from the works I’ve mentioned, are his heavily censored film about a plague striking Hong Kong, Yesterday Today Tomorrow (1970) and the bitter domestic drama Pei Shih (1972).

When he started in the industry, he says, “I ran into these acquaintances who taunted me by saying how I was trying my hand at making Cantonese chaan pin [shabby films]. That was very insulting to the film profession in general…so I promised myself to go in and change things when the opportunity arose.” For him, change meant both modernizing Cantonese film technique and tackling social problems.

Lung Kong’s cinema, all agree, has a strong moralizing bent. He focuses on social problems—juvenile delinquency, nuclear war, prostitution, the exploitation of women in marriage. The films mix sensationalism, partly as audience bait, and social criticism. The Story of a Discharged Prisoner, reimagined by Tsui Hark and John Woo as A Better Tomorrow (1986), is at once a gangster tale and a harsh comment on the poverty that drives men to crime. Lung himself, armed with calisthenic eyebrows, plays the police officer hounding the protagonist. The Prince of Broadcasters begins as a pointed critique of popular culture, where schoolgirls fasten obsessively on a playboy radio personality. The film devolves into a more traditional thwarted-lovers plot when the protagonist reforms through his (mostly) chaste relationship with a wealthy girl.

Lung Kong’s cinema, all agree, has a strong moralizing bent. He focuses on social problems—juvenile delinquency, nuclear war, prostitution, the exploitation of women in marriage. The films mix sensationalism, partly as audience bait, and social criticism. The Story of a Discharged Prisoner, reimagined by Tsui Hark and John Woo as A Better Tomorrow (1986), is at once a gangster tale and a harsh comment on the poverty that drives men to crime. Lung himself, armed with calisthenic eyebrows, plays the police officer hounding the protagonist. The Prince of Broadcasters begins as a pointed critique of popular culture, where schoolgirls fasten obsessively on a playboy radio personality. The film devolves into a more traditional thwarted-lovers plot when the protagonist reforms through his (mostly) chaste relationship with a wealthy girl.

Lung’s film style is self-consciously 1960s modern, with zooms, calculated compositions, and handheld passages. He cuts fast, avoids dissolves, and offers fairly complex traveling shots. Looking at the cheap sets and listening to the awkward sound (including snippets of classical music and The Great Escape grabbed from LPs), one becomes aware of what a Cantonese director of the day was up against. So if the technique seems at times forced, you can at least admire Lung’s attempt to give his films a contemporary gloss.

The films were of crucial importance for local culture of the 1960s and have had continuing influence on younger directors. A very informative book of essays and interviews, produced to the usual handsome standards of the Film Archive, is in Chinese but includes a disk with a digital pdf of English translations. Two of the texts can be found here.

Jean Christophe in Macau

Another hop. I know nothing about Louis Fei, except that he was the brother of Fei Mu, whom I’ll be talking about in an upcoming entry. Romance in the Boudoir (1960) recasts the core situation of Fei Mu’s masterpiece Spring in a Small Town (1948). The situation, drawn from Romain Rolland’s novel Jean Christophe, is simple: A woman in a loveless marriage is visited by her former lover. In this version, her husband is a miserly doctor who wants the lover, Qin, to help him get a hospital post. Qin’s presence in the household rekindles the old romance and the couple hover on the edge of adultery.

Romance in the Boudoir is a bold piece of work. It opens with a prologue showing husband and wife trudging through Macau, utterly distant from each other. On the soundtrack we hear a woman singing about marriage as a prison. When Qin arrives, a parallel sequence traces him from the harbor to the household as a male vocalist sings of his weariness and broken heart. These melodic soliloquies will be evoked later in the film, when Qin and Suxuan stretch out by the fireplace and start to sing as the camera circles them.

Louis Fei makes maximal use of the house set, letting the vast staircase dominate the action on both floors. Repeated setups from the top of the stairs show the bannister cutting diagonally into the frame, pointing like an arrow to the climactic moment at the front door in the distance. Over everything hovers erotic tension, lasting several minutes during one scene when the former lovers tentatively touch one another before recoiling and then drawing toward one another again. If the doctor is somewhat caricatural, the portrayals of the wife and lover show a great subtlety, and the use of props, notably a glass of milk, is nicely modulated. This film shows how comparative large budgets enabled the Mandarin-language companies to make films of a high production standard, both in script and execution.

Dragons on fire

Now jump to 2010. Dante Lam is the hot new action director on the local scene, after the success of Beast Stalker (2008) and The Sniper (2009). Actually, like most overnight successes, he’s been at it awhile. He made an admirer of me with Jiang Hu: The Triad Zone (2000), which has one of the most graceful passages of graphic cutting (involving a red umbrella) that I’ve seen in recent Hong Kong film.

He’s back with the first big action film of the season, tagged with the barely adequate English title Fire of Conscience. The action scenes are better than the plot, which is better than the eternal impassivity of Leon Lai, a pictorial cipher in nearly every role he assumes. Still, you have to reckon with a film that includes not only a thrilling car chase, a truly scary gunfight in a restaurant, and grenades tossed around pretty casually but also a pregnant woman locked in a car slowly filling with carbon monoxide. The topper comes in the very last few shots, which provide as gruesome a flashback image as I’ve seen in quite some time and justifies the key line, “Save for revenge, what else is there?”

Visually, Fire of Conscience never surpasses the bravado of the black-and-white CGI opening, during which the camera coasts through a snapshot of action and lets clues float and scatter around the frozen characters. (It’s admittedly gimmicky, but more hypnotic than the comparable Watchmen opening.) Still, it’s exciting genre fare. What hath Ben Brodsky wrought?

Photo of Brodsky and colleagues by courtesy of Mr. Ronald Borden. The interview with R. F. Van Velzer was published in Hugh Hoffman, “Film Conditions in China,” Moving Picture World (25 July 1914), 577. Thanks to Frank Bren and Law Kar for this information, and to Tony Slide for calling attention to the article. The quotation from Lung Kong is from Clarence Tsui, “Scenes of the Crime,” South China Morning Post (22 March 2010), C1.

Patrick Lung Kong, with Sam Ho of the Hong Kong Film Archive.

Rights to revert to author

In the Mood for Love.

DB here:

“They never tell you that.”

My neighbor Jim Cortada is a polymath. He joined IBM in the 1970s, when history Ph.D.s faced bleak prospects for academic jobs. Since then Jim has done everything from selling mainframes to leading seminars on quality management. As a business guru, he writes books on management strategy and tactics. He also writes both popular and academic books on the history of information technology. He finds time as well to write books on his grad-school specialty, Spanish diplomatic history.

Jim’s Amazon listing consists of fifty titles. He has worked with publishers as small as Lulu and as big as Oxford. So when he talks about the nuts and bolts of publishing, I listen. His reaction to what happened to me recently is as succinct as it as accurate: They never tell you that. Put into proper context, it’s good for young academics to keep in the back of their minds.

The Syndics speak, after prodding

14 Amazons.

Early this spring, when my royalty statement from Harvard University Press arrived, I noticed an anomaly. From early 2000 through the end of 2007, Planet Hong Kong had sold about 7000 copies. The average, about 800-900 copies a year, isn’t much for trade books, but fairly solid for an academic title. Perhaps courses on Hong Kong film were using it as a text.

But the newest royalty statement brought me up short. In calendar 2008, the sales dropped off the cliff. Harvard shifted only 85 paperback copies and virtually no hardcovers.

Naturally, I blamed myself. People were losing interest, or the book wasn’t good enough to sustain an audience. But then I noticed that Amazon was offering the book only from third-party sellers. I checked Barnes & Noble and Harvard’s own website; both claimed to offer new copies. So I assumed that some long-term glitch at Amazon was leading to declining sales.

Naturally, I blamed myself. People were losing interest, or the book wasn’t good enough to sustain an audience. But then I noticed that Amazon was offering the book only from third-party sellers. I checked Barnes & Noble and Harvard’s own website; both claimed to offer new copies. So I assumed that some long-term glitch at Amazon was leading to declining sales.

So about six weeks ago I tried contacting my editor at Harvard. Getting no email replies, I left phone messages. No response.

Mossbacks among you will recognize this as a danger sign. When an editor doesn’t reply, it’s not good news. So a call to Harvard’s editorial offices brought the promise of a prompt response. An email from a good-natured staff member there gave me the lowdown: Planet Hong Kong was being taken out of print. There were too many pictures to make a reprint edition worthwhile, someone had decided. Exactly when was that decision made? That matter was left vague, but I was told that the process of transferring rights to me had already begun.

Actually, I was a little surprised at that. Transferring rights back to the author is an old-media custom, but today, when “multiple platforms” are the new business model, there’s no reason for a book to go out of print. Publishers can keep selling a book through print-on-demand or in digital copies. Why Harvard’s decision-makers chose to revert the rights to me remains a bit of a mystery.

In any event, now the 2008 sales slump made sense. Only 85 copies of PHK were sold that year because in all likelihood Harvard, having decided not to reprint, was simply exhausting its stock of copies. On the basis of past performance, those sad 85 copies probably sold fairly early in the year, so there’s reason to think that the decision not to reprint was taken at some point in 2008, perhaps quite early. Yet I wasn’t informed of the decision until I inquired in 2009.

Nor am I complaining that I wasn’t consulted about the decision. Editors and press directors never tip their hand, for the very good reason that the author has no contractual say in the matter. And telling can only cause trouble, because authors have an annoying desire to keep their books in print.

In particular, academics relish prolonged disputation. If you’re told that your book might be headed for landfill, wouldn’t you launch an ambitious plea for reconsideration, complete with references to all the people you know who love the book and reminders that generations yet unborn will be eager to absorb your ideas? (Quotes from favorable reviews optional.) If tension rises, you can always murmur about feeble marketing efforts and a risibly high cover price. It could all get nasty, and the conclusion is foregone anyhow.

So when the publisher is mulling whether to drop your book, don’t expect to have a vote. But once the press has decided to drop it, why the reluctance to tell you?

I’m the one who’s supposed to kill my darlings

Shanghai Blues.

I’ve now had six books go out of print. Correspondence with regard to two of those, back in the 1970s, is lost in the mists of time. Of the four most recent instances, I was told many months after the decision was made, and by the most impersonal of letters—not from my acquisitions editor but from somebody in the cloisters of marketing or production. In the current Planet Hong Kong case, and in an earlier instance, I learned of the book’s fate only because I inquired. Who knows when I would have been told?

Nobody likes to give bad news, and university press staff members are unlikely to be flint-hearted business people. Editors are affable and solicitous; I’ve found them good company. They work long and hard on often fruitless projects: proposals that never turn into manuscripts; manuscripts that can’t get through the vetting process; manuscripts that fall hors de combat in editorial meetings.

And academic writers are almost sadistically inconsiderate. Once professors get their book contract, they behave like their students, trotting out excuses that they laugh about in the faculty pub. They ignore deadlines, word counts, permissions—in sum, everything they signed the contract to honor. Yet these antics are tolerated with remarkably good humor. If university book editors had a taste for blood, they’d be trade book editors. Or agents.

More broadly, it seems to me, university presses are under unique pressures. The good side is that they are a business that can’t go out of business. Even in hard times like these, a university press is unlikely to be shuttered. The blow in prestige and faculty morale would be severe. So most presses limp along. Since most of their costs are bound up in salaries, wages, and benefits, the only area that can feasibly be trimmed is marketing.

Furthermore, and too few young scholars realize this, every press plays a crucial role in the tenuring process. A humanities professor teaching in most universities and many colleges typically needs to publish at least one through-written book to support a case for tenure. There is thus a vast demand that some entity publish said books. The problem is that an academic can deftly write a book that virtually no one wants to read, let alone buy. So university presses are, in effect, subsidizing the tenure process.

Seen from this angle, university publishing is a system of reciprocal altruism. The University of West Overshoe Press publishes Professor Smith’s book on cultural resistance in Girl Scout parade floats. Professor Smith is thereby on his way to tenure at his school, the University of Rising Damp. At the same time, the URD Press publishes Professor Jones’ book on sexual transgression in Futurama. Professor Jones resides at Shattered Tibia State, whose press has just accepted a manuscript (on Wittgenstein’s use of prepositions in the Tractatus) from Professor Johnson. . . who teaches at the University of West Overshoe. I’ve abbreviated the cycle, but you can see that eventually, like the spirochete in Professor Pangloss’s song in Bernstein’s Candide, everything circles around. Any one university press is supporting employment at other universities.

So I’m entirely in sympathy with university presses. And the process, eccentric though it sometimes seems, can produce good books. But presses need to deal more straightforwardly and promptly with writers when a book’s fate has been decided. Jim Cortada is right. They never tell you that. But they should, and pronto. For then you can make plans.

Planet Hong Kong 2.0

Shaolin Soccer.

The lesson for young scholars is simple. Expect that your book will go out of print. Some books will pass over to print-on-demand or digital versions, but it doesn’t hurt to expect the worst. And a book can go out of print surprisingly fast. (The original British edition of my book on Ozu lasted only about two years.) You may learn of your work’s passing by accident, as I did, or through more direct notification, but you should think about your options.

You can simply let it go, accepting the press’s rationale that your book will remain available in libraries around the world for decades. Or you can wait for Google or Amazon to get around to digitizing your work.

Yet an out-of-print book is like a child limping home after a few rough encounters with the world. You might feel duty-bound to take care of it somehow. How?

First step in salvage is to make sure pre-print materials have not been destroyed. Most contracts require that these be returned to you if you regain the rights, but publishers, speedy in so little else, can dump physical production materials in the blink of an eye. In the old days, those materials usually consisted of rolls of thick celluloid, three or four feet wide and very long, on which the pages were printed like panels on a vast comic strip. (Several of these monsters lie pod-like in my basement.) But now most books are stored on computer files, often as PDFs. Copies of those should be returned to you.

Until recently, resuscitating your book came down to trying to find another publisher. I’ve had luck with this tactic only once, with The Cinema of Eisenstein—first published by The Syndics in 1994, yanked out of print in the early 2000s, brought back by Routledge in 2005. Republishing was always rare and is now nearly nonexistent; presses can’t afford to bring out a book that may have saturated its market.

Now, though, there’s another way to revive your sickly child.

For some years I’ve argued that most “tenure books” should be published only in digital form. But university presses have been reluctant to try such an idea, since an online book might not satisfy tenure committees. The best plan would be for some well-respected university press to lock in a vetting process for online publication as rigorous as any for print books. It seems that the University of Michigan Press has begun to do this. Once the model proves its value, and once problems of piracy are solved, the practice could catch on fast. For many books I own, I’d be happy to have PDF files on my computer. There should be big cost savings and, we hope, lower purchase prices—maybe even through selling separate chapters. Like music CDs, many books have only a few chapters you want. We can look forward to the iTune-izing of academic writing.

Yet if university presses need to be cautious about online publishing, the individual scholar doesn’t. The tactic is simple: Plan to put your out-of-print books on the Web.

Some authors may prefer to take existing PDF files or make new ones from the book’s pages, and add a fresh introduction. That’s essentially what Marcus Nornes and his colleagues helped me do with Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema. We also tipped in new color images.

The alternative is to revise your book and post a second edition online. It’s a lot of work, but then you could probably charge something for it.

As for Planet Hong Kong, I’m still mulling my next step. Perhaps a publisher will be interested in a new edition, revised, corrected, and updated. Alternatively, I might prepare Planet Hong Kong for downloading on this site. Unlike the original, it could have color illustrations. I have to say that I find this option intriguing.

If you want a used copy of the old edition of PHK, about a dozen are available here. Once dealers learn it’s out of print, they may raise their prices. In any event, I hope to bring the book back in some form. Don’t say I didn’t tell you.

PTU.