Archive for the 'National cinemas: Hong Kong' Category

They’re looking for us

DB again:

Perhaps you consider Music and Lyrics (2007) a bit of fluff. Bear with me. Apart from offering an ingratiating parody of 1980s music videos, which at the end gets replayed as a parody of 1990s Pop-Up Video, this movie provides a nice example of a technique that film viewers tend to enjoy.

Alex Fletcher, a has-been pop singer, gets a chance to revive his career by writing a love song for Cora Corman, current goddess of teenyboppers. Alex can dash off a melody but he needs a lyricist. His agent has advised him to try to collaborate with the “very hip, very edgy” Greg Antonsky. Their first meeting doesn’t go well. Greg’s lyrics, rhyming witch and bitch, don’t suit Alex’s more romantic style, and Sophie, Alex’s plant-tender, keeps interjecting sweeter lines. After first eyeing Sophie lecherously, Greg decides she’s a simpleton. He dashes out, condemning Sophie and Alex as sentimental fools: “You people disgust me!”

As written, the character of Greg the lyricist is only mildly funny, but the insert shots of actor Jason Antoon raise the comedy thermostat. With his lowered brow and glaring, slightly unfocused eyes, Greg tries to play the badass, but his aggressiveness comes off as egotistical pettiness.

The cutting relies on single shots of each character, in keeping with today’s style of intensified continuity editing. This ensures that we track every character’s facial expression. When Sophie first interrupts, Greg glares, then lolls his head backward; his time is too important to spend with these losers.

In all, Greg is onscreen for about three minutes, and the plot continues without him.

Eventually, Alex and Sophie break up because Alex is prepared to let Cora turn their song into a sleazy number. The climax comes at Cora’s concert, when Alex appears onstage and sings a tune he composed for Sophie: “Don’t Write Me Off.” At the song’s close, we get a shot of him at the piano followed by several reaction shots in the audience, with Sophie’s close-up favored.

After a backstage reconciliation between Alex and Sophie, the film’s second plotline is resolved. Cora performs the number she asked the team to compose, but it’s played the way Sophie had wanted. The up-tempo melody brings Alex and Cora onstage together and then, as the third verse begins, ties together the secondary characters in a series of reaction shots. We first see an African-American backstage handler, whose vigorous swipe of his arm launches a string of smiling responses.

We get shots of Alex’s agent and his daughter, then Sophie’s brother-in-law and his son, and Sophie’s sister and their kids.

Their responses celebrate both the romantic couple’s success and the sincere emotion that the song elicits. This aura of good feeling is confirmed negatively by one more reaction shot.

It is the sort of satisfying surprise that Hollywood often trades on. After being offscreen and out of mind for eighty minutes, arrogant Greg returns. We didn’t see him come to the concert; we didn’t know he was there; we had likely forgotten he existed.

This shot is agreeable because it keeps Greg’s sourness consistent. A more kindly film would show him smiling begrudgingly, won over by the authentic sweetness of the music. But instead he mimics blowing his brains out and lolls his head back as he did before.

Greg’s appalled reaction to the song confirms our initial judgment of his character and our sense of the song’s unpretentious sincerity.

If you’re like me, this unexpected four-second shot makes you laugh. The director, Marc Lawrence, has followed tradition by including humor in a scene of high sentiment, not diluting the happy tone but reinforcing it. Call it corn, hokum, or tosh; claim that it hits below the belt. I won’t disagree. But the mixture of laughter and sentiment works on us like a reflex. And Greg’s response inoculates the movie against seeming wholly naive or cloying. As so often, Hollywood lets us have things, emotionally speaking, both ways.

This response is accomplished through one of the most powerful weapons in the filmmaker’s arsenal. A director can disarm our emotions through a single reaction shot.

Recoil and reaction

The same sort of dynamic is at work in a less lightweight scene. Everybody remembers the moment in Jaws when Sheriff Brody, scooping chum over the side of the Orca, is taken unawares by the arrival of Bruce the shark, bursting out from the background.

But Spielberg, who understands audience response, follows this nifty shot with a topper. In a reverse-angle framing, Brody’s head snaps into the shot with the abruptness of Wile E. Coyote reacting to the Road Runner.

The sudden thrust and halt of Brody’s head sells his stunned facial expression. Our shock at Bruce’s entrance is joined by our uncontrollable urge to giggle at Brody’s cartoonish trajectory and the sheer stupefaction on his face—not fear yet, but rather a recognition of the sheer enormity of the adversary. From here on, his refrain, “We’re gonna need a bigger boat,” will remind us that unlike his shipmates, he has been very nearly head to head with the Great White.

The reaction shot seems like a simple technique. Doesn’t it just spell out or repeat what’s happening? Sometimes, but not always. As we’ve just noticed, it can let the director layer the effect of a scene. Once an action has gained a particular emotional coloring, the reaction shot can add a different tint. The romantic exhilaration of the song in Music and Lyrics is heightened by Greg’s bad-natured gaping. Bruce’s fearsome movement forward is balanced by Brody’s recoil and his comically fixed stare into space.

And sometimes the layering and balancing can take place within the reaction itself. In John Woo’s A Better Tomorrow, Mark Lee enters a restaurant and pretends to be playfully feeling up a woman in the corridor. But he’s actually planning to kill a gangland leader, who’s partying in a room off right. First shot: Mark looks winsomely off after the retreating woman. Cut to the leader celebrating.

We might expect that the return to Mark will show his fake expression fade into a sincere one. Instead, Woo simply shows a new expression on Mark’s face as he listens to the party offscreen right.

Eisenstein admired Asian theatre for its “acting without transitions”; here the brief shot of the gangster eliminates the emotional transition taking place on Chow Yun-fat’s face. Mark’s determination is all the more forceful for being so abruptly presented, as if a mask has simply fallen away.

Mirrors like big faces

Prototypically, the reaction shot shows a face expressing emotion. The technique trades on our ability to grasp expressions, often very quickly. We’ve perfected this skill since birth, and there’s evidence that newborns are pre-wired to detect and respond to certain expressions, especially from mom. Exposure to actual expressions in their daily lives allows children to refine and tune this proclivity. So one part of the reaction-shot technique is a very well-practiced skill that cinema has exploited.

Some recent findings in neuroscience suggest that reactions portrayed onscreen can arouse us deeply. Back in 1995, researchers observed that one sort of nerve cell was activated in a macaque monkey’s brain when the monkey reached for a peanut. No surprise there, since that cortical area is known to be a region involved in planning and initiating bodily movements. But researchers noticed that the same cells fired when the macaque watched another monkey reach for a peanut. Soon researchers were finding clusters of these “mirror neurons” in human beings, strongly suggesting that when we see someone do something, our brain responds as if we were doing it ourselves.

Since facial expressions involve stretching and relaxing facial muscles, it’s possible that mirror neurons play a role in arousing empathy. The mere sight of someone smiling or frowning can trigger some of the same neural events as when we smile or frown ourselves. We’ve all experienced a sort of “motor mimicry” when a radiant smile makes us involuntarily smile too. In one set of experiments, neuroscientists found that people’s mirror neurons responded the same way to film shots of disgusted faces as they did to disgusting smells in real life. Reaction shots may gain their strength from not merely our ability to understand facial expressions but the power of facial expressions to trigger in us an echo of the emotion displayed. With a string of shots of smiling faces, as in the Music and Lyrics concert, our own impulse to smile would have to be put down by force of will.

Of course, characters can display their reactions onscreen without being shown in reaction shots in the modern sense. Many films of the earliest years portray the actors in a long-shot framing of the entire action. Realizing that our eyes will turn to areas of high information content like hands and faces, directors often staged and lit the action for easier pickup of the faces. You can see examples of that in this and this earlier entry.

But the reaction shot as such implies cutting, either breaking down the scene through analytical editing or building up a scene from details (so-called constructive editing). In the 1910s, directors began systematically creating a scene from separate shots. (For more on this development, go here and here.) In this approach, particularly as practiced in Hollywood, a person’s facial expression could become part of an ongoing suite of shots, each concentrating on one item of information. Thanks to cutting, the facial reaction could be underscored, sharpened, and timed for best effect. The suddenness of the cuts to reactions in Music and Lyrics and Jaws is central to their effect.

A reaction shot need not be a close-up, and it need not show only one person. One of the funniest reaction shots in cinema, I think, occurs in The Producers, when Brooks cuts from the “Springtime for Hitler” number to the audience’s frozen, slack-jawed response. This long-shot framing suggests that we should think of the reaction shot as a functional category; it’s a role that various types of shots can fulfill.

Still, the development of the close-up as a technique is tied its function of showing responses. In silent cinema the people’s faces, reacting to the flow of story action, are providing a continual measure of the characters’ states of knowledge and feeling. Entire scenes could be played out as a string of intercut reaction shots, as Kuleshov proved in theory and the Americans showed in practice. In Dreyer’s La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc, as above, the reaction shot is virtually the dominant technique. And point-of-view cutting patterns integrated the isolated close-up reaction shot with images showing what the character was seeing.

With the emergence of sound cinema, you could argue, the reaction shot was briefly demoted. In early talkies, scenes were played in wider shots, and cut-in reactions could, in the hands of inept directors, seem brusque interruptions. But fairly quickly the reaction shot returned, usually as a stressed moment in a scene built out of more distant and neutral framings. Nowadays, with directors using fewer ensemble shots and disinclined to frame actors in prolonged, balanced two-shots, the reaction shot has retained its place in popular moviemaking.

Apart from registering a character’s response, the reaction shot also offers a broader take on the action. Noël Carroll has suggested that the reaction shot can steer us toward the proper way we should construe the whole fictional world we’re witnessing.

For instance, both fantasy fictions and horror stories feature monstrous beings. But in fantasy a troll or griffin might be benevolent. In large part, the way we construe the monster will depend on how the other characters respond. If the hero or heroine looks kindly upon the creature, as in The Golden Compass or Pan’s Labyrinth, then we know we’re not supposed to be horrified. Carroll explains:

A creature like Chewbacca in the space opera Star Wars is just one of the guys, though a creature gotten up in the same wolf outfit, in a film like The Howling, would be regarded with utter revulsion by the human characters.

Reaction shots instruct us in how to respond to the fictional world as a whole.

So robust is the reaction shot that it can stand on its own, if it gets a bit of help from context. In The Third Man, Holly Martins has been trying to defend his old pal Harry Lime from accusations of crooked dealing. When Holly visits a hospital ward, however, he sees what Harry’s bogus penicillin has done to babies. But we don’t; director Carol Reed shows us only Holly’s dispirited reaction.

As Clive James puts it:

The movie’s whole moral structure pivots on that one point. Unless we are convinced that the two men are seeing horrors, there would be no justification for Holly Martins’ delivering the coup de grace to his erstwhile friend.

A chase through feral eyes

Reaction shots can modulate across a scene, as the characters’ feelings change. But I’m also impressed by the way a scene can build emotion by developing from flat, affectless reaction shots to more intense ones. A good example is the long climactic highway chase in Road Warrior.

The outlaw gang is pursuing a tanker truck they think is full of gasoline, while Max, the Feral Kid, and a few warriors ride the monster truck. The scene’s stunts, acrobatics, and vehicular mayhem are impressive, but these qualities have been replicated in a lot of movies. What gives the Road Warrior scene a special pungency are the many reaction shots of the characters mounted on the truck. For the most part we’re aligned with them both physically and emotionally, and we are allowed to share their moment-by-moment reactions to each turn of events.

Early in the sequence, when the tanker team knocks out some pursuers, we get unequivocal reactions of jubilation.

But as the marauding gang gains control of the tanker, the reactions of the team turn to glum, nervously comic dismay.

The scene’s emotional graph is traced most thoroughly in the reactions of the Feral Kid. Throughout most of the film he has two expressions—neutral and fierce. Clinging to the side of the truck, he watches the steady progress of the pursuers with mild apprehension. If he started to shriek with fear now, the scene would have nowhere to build to. I think that we’re inclined to read his expressions as signs of his characteristic stoicism.

But when Max starts to dispatch gang members with his shotgun, the Kid lets out a hoot of pleasure. At one point a thug sends an arrow into the cab. No emotional response from Max or the Kid.

Max blows the thug off the roof of the cab. The kid crows.

The Kid’s laugh licenses us to laugh too—at the businesslike crispness of Max’s response and at the sheer infectiousness of the Kid’s admiration. (Our mirror neurons are presumably working overtime.)

The next phase in the arc comes when Max orders the Kid to crawl out onto the truck hood to retrieve the shells. Now the boy’s expression becomes cautious and a little fearful.

He sprawls on the hood and grabs the shells. At that moment Wez pops up, clinging to the front grille, and we get two lunging reaction shots.

If the Feral Kid had shrieked earlier in the scene, these cuts would have less impact. The high point of the drama is matched by the fact that finally, something has happened to scare the bejesus out of this boy. Even Max has lost his cool, wrenching the wheel ferociously.

Soon, in another laugh-inducing reaction, Wez realizes that he is point man in the crash that is soon to come.

You couldn’t ask for a better example of how reaction shots can be more than a one-off tactic. In Music and Lyrics, the quick insert of Greg gave a little jab to the scene. In Road Warrior, the Feral Kid’s changing reactions add an emotional curve to the progression of the chase. Without him, the scene would lack a whole layer of feeling.

There’s much more to say about the reaction shot. We’d want as well to talk about films that withhold information about characters’ reactions—by using enigmatic or ambiguous reaction shots, or by eliminating reaction shots altogether. (Think Antonioni, Hou, Angelopoulos, Tarr, and others.) Maybe I’ll take those matters up in another entry. For now, let’s salute one of the most enjoyable and arousing dimensions of cinematic storytelling. It only seems simple.

My quotation from Noël Carroll comes from The Philosophy of Horror; or, Paradoxes of the Heart (New York: Routledge, 1990), 16.

Years of being obscure

DB here:

The Cannes screening of Ashes of Time Redux reminds us that Wong Kar-wai has been an incessant reviser of his work. Versions proliferate in different markets—one for Hong Kong, one for Taiwan, one for the international market—and he has sometimes promised online versions, or bonus DVD features. Buenos Aires Zero Degree (1999) by Kwan Pung-leung, provides tantalizing bits of scenes between Tony Leung Chiu-wai and Shirley Kwan. Yet it makes us wonder about the film we might have had if Wong had not decided to cut the whole plot strand out (after keeping Shirley in Argentina for several weeks).

We can add to the list Days of Being Wild (1990), Wong’s breakthrough movie. It’s been circulated for years in an international version, which is currently available on DVD. But some people people have recalled seeing a fugitive, somewhat hallucinatory cut of the film. Some time ago I examined that alternative, and I figured it’s worth showing what I saw. This rareversion prefigures some aspects of Wong’s later style, particularly as seen in In the Mood for Love (2000). I don’t have solutions to all the puzzles it poses, but I’ve gathered some information. If you know something about this “obscure” version, feel free to write to me and I’ll append your comments to this entry.

I need hardly add that there are spoilers galore here. In the images, differences in tonality and aspect ratio spring from my two sources, DVD and 35mm film (which itself fluctuates a little in aspect ratio from shot to shot).

Last things first

Days of Being Wild begins in 1960 Hong Kong. It follows the wanderings of Yuddy (Leslie Cheung), a preening young man who casually seduces women, notably the brassy Lulu (Carina Lau) and the subdued, naïve Lai-chen (Maggie Cheung). Living with his aunt, Yuddy wonders why his mother abandoned him. He finds her living in the Philippines but doesn’t confront her.

At the climax in Manila, Yuddy meets a sailor (Andy Lau) and picks a fight with local thugs. The two men flee by hopping aboard a train. By chance, the sailor was formerly a Hong Kong cop, who was attracted to Lai-chen. On the train, Yuddy is shot by a vengeful thug. The film concludes with a series of shots of Lulu, Lai-chen, and—the big mystery—a slick young man in a seedy apartment who files his nails, combs his hair, equips himself with handkerchief and cigarettes, and sets out for a night on the town. He doesn’t speak, and he has never appeared in the film before. It’s one of the boldest narrative maneuvers in contemporary cinema, and it has occasioned a lot of comment.

The differences in the final sequences begin on the train. In the international version, a shot of the landscape seen from between the cars is followed by a high-angle medium shot of the cop.

This constitutes a mini-flashback, since Yuddy has already died from the gunshot. The cop’s voice-over initiates the exchange: “The last time I saw him, I asked him a question.” (As usual in Wong’s work, we have no way of knowing whom is being addressed; this could be an inner monologue, a report to an unseen character, or simply a self-conscious address to the audience.) For a little more than two minutes, the camera shows only the cop. He asks if Yuddy remembers what he was doing at a certain time. Yuddy understands immediately that the cop has met Lai-chen, and he replies from offscreen, asking about the cop’s relation to her and asking him to tell her that he, Yuddy, has no memory of her. The cop worries that Lai-chen may not even recognize him.

The exchange ends with a wordless shot of Yuddy sitting against the seat, eyes barely open, as an orchestral version of “Perfidia” rises up. The scene ends with an extreme long-shot of the train. The tune was heard earlier when the cop walked away from a nighttime encounter with Lai-chen, so this refrain reminds us of the cop’s yearning for her.

The alternate version doesn’t alter the overall situation much, but it presents different emphases. After the shot between the train cars, we have an off-center long shot of the cop; it’s then that we get the voice-over: “The last time I saw him, I asked him a question.” Cut to a medium close-up of Yuddy, which replaces the shot of the cop. Now for about two minutes he speaks and the cop’s reactions are kept offscreen.

As far as I can tell at this point, the dialogue is identical. In effect, we have a virtual shot/ reverse-shot exchange between the two films! And instead of holding on the framing of Yuddy, or cutting to the cop’s reaction, Wong simply gives us a shot of the two men in facing seats. This is followed by a very different shot of the train, winding through the sort of greenish-blue foliage seen in a famous earlier shot, and there is no music.

The international version puts the emphasis on the cop, who is both challenging Yuddy and obliquely reflecting on his own situation.; hence perhaps the “Perfidia” theme, which is associated with him. The alternate version keeps us focused on Yuddy throughout, our final stare at him, as it were, before a two-shot reasserts an equivalent weight between the two men, and perhaps their memories as well.

The very end

The variations continue in the final shots. Both versions begin with the shot of Lulu striding to the camera in a telephoto framing, above. Now she’s in the Philippines.

In the international version, this shot is followed by Lulu swanning into a bedroom, hanging up her dress, and saying to the landlady, “There’s someone I want to ask you about.”

In the other version, we see her passing through a somewhat sleazy hotel lobby and asking for a spare room. As a result, it’s somewhat less clear that she’s pursuing Yuddy.

The scene shifts to the stadium where Lai-chen works as a ticket seller. (Stephen Teo’s stimulating book on Wong specifies that it’s the South China Athletic Association.) Customers are swarming in for a football match. The obscure version gives us two quick tracking shots of the crowd, with the second ending on a profile shot of Lai-chen in her booth.

The standard version offers only one of the tracking shots and ends with a static framing of the profile composition. But this version adds a shot, beginning the scene with a head-on composition of her at her window.

At this point the alternate version omits two shots that have attracted a lot of critical commentary. Before the shot of Lai-chen shutting up shop, we see a high-angle view of tramway tracks and a shot of a clock outside the stadium.

The clock shot recalls Lai-chen’s meeting with Yuddy, while the tramcar lines recalls her rainy-night encounter with the cop. Instead of these empty shots, the alternate version cuts from Lai-chen in her booth to a shot of a soccer match, evidently seen through a slot in her cabin.

The rest of what follows corresponds in both versions. Lai-chen is seen reading a newspaper before closing the booth.

Both versions likewise wind down with a shot of the phone booth, the one that Lai-chen and the cop had lingered beside, followed by a closer view of the interior. The phone is ringing.

The first shot of the pair recalls, in its high-angle composition, the rainy night that the two met. (Wong’s characters are haunted by memory, but he forces us to use ours too.)

The cop had asked Lai-chen to call him, and the previous scene showed her closing her window, so we might infer that now she’s trying to get in touch with him—not knowing, as we do, that he’s quit the force, become a sailor, and watched her boyfriend die. But we can’t be sure that she’s the one making the call.

The very last shot, showing Tony grooming, is also the same in both versions. (One stage of it is at the very top of this entry.) It is a real crux. Why is Wong showing us this down-at-heel gambler for two and a half minutes? He has no evident connection to any of the characters we’ve followed, and we will never see him again.

Most critics have also accepted Wong’s explanation that he had planned a sequel, one showing how Yuddy’s influence over others lingered long after his death. Patrick Tam told Stephen Teo that the shot was his idea, a setup or trailer for the next film, turning everything we had seen up till now into a lengthy prologue. (1) But Days of Being Wild was a fiasco at the box office, taking in HK$9.7 million, or about $1.25 million US (in a year in which Stephen Chow’s All for the Winner earned over four times that). So the sequel was never made.

Yet these intriguing circumstances don’t really justify the epilogue’s purposes and effects. A causal explanation doesn’t necessarily yield a functional explanation. What role does this disruptive shot play in the film’s overall dynamic? If Wong had made the sequel, it might have been seen as a brilliant stroke; without the followup film, how can we justify its presence?

It’s reasonable to argue, as Teo does, that this vision of Tony’s primping generalizes Yuddy’s case, suggesting that his rootless narcissism is a condition of many young men of the day. You might also suggest that he provides a sort of male equivalent of the playgirl Lulu; just as the cop played by Andy Lau is a good, though unachieved, match for Lai-chen, Tony would pair up better with Lulu than Yuddy’s pal (Jacky Cheung), who pines for her.

Actually, the alternate version sheds a little light on the problem. It doesn’t provide a definitive answer to what Tony is doing there, but it does offer some tantalizing possibilities. In the alternate version, Tony is not only the last character we see, but the first one. And he’s embedded in a sequence that looks ahead to the style for which Wong has been both admired and castigated.

Languor and ellipsis

After the credits, the international version opens with Yuddy striding forcefully into the soccer stadium and mesmerically flirting with Lai-chen. But the print I examined of the obscure version interrupts the credits and shows us none other than the nameless young spark played by Tony Leung Chiu-wai, buffing his nails. (It seems to be an earlier stretch of the final shot, which continues this action.)

Over his image, we hear this in a male voice (no subtitles on the print):

I saw him one more time. He had just returned from the Philippines. He was much thinner than before. I asked him what happened to him. He replied that he just recovered from his sickness. He didn’t want to chat anyway, so I asked him what his sickness was.

Afterwards, we didn’t see each other any more.

This is very mysterious. Whose voice is speaking—Tony’s, Yuddy’s, Andy Lau’s? I can’t identify it. And who is the he referred to? The most plausible candidate is Andy, who may have returned to Hong Kong; and he is looking fairly ill in the film’s final scenes. But it might be the Tony character, as described by one of the other men, or even at a stretch Yuddy himself, who has somehow survived the shooting and returned to Hong Kong.

These ruminations assume that this opening shot frames a flashback by rhyming with the final image of Tony rising from the bed and dressing for his night out. It provides a sheerly formal justification for the final shot, which now completes the action begun at the start. But substantively, we’re still left with a variant of the original question. Instead of asking why end the movie with this remote character, we now ask why he’s used to frame the movie.

The questions have just begun, however. After this eighteen-second shot of the dapper Tony, we get a music montage lasting about eighty-three seconds. It’s quite perplexing. We’re in a warren of corridors, a bit reminiscent of the byways of Chungking Mansions in Chungking Express, and everything is in slow motion. We follow Andy Lau, in a yellow pullover, striding through the darkness and sweating profusely. Then we find him playing cards with some unidentified men. At one point, we see a woman climb the stairs, at other points we glimpse a man with an enormous snake coiled around him. The sequence ends with shots of a hand seizing a cleaver and shots of Andy, back in the corridor, striding away from us. The whole sequence is accompanied by the song “Jungle Drums,” which continues from the shot in Tony’s apartment but is now sung by a female voice (Anita Mui’s).

I was able to take stills of these shots, so I’ll go through them one by one, despite their iffy quality. (The images are very dark, and the print was worn and a little speckled.) After the opening shot of Tony, we get eighteen shots, all in slow-motion, many out of focus, and nearly all using camera movement. Often the cuts are matched in the normal fashion, but sometimes the connection is purely kinetic. As often in Wong’s work, the timing of the cuts synchronizes with beats or melodic lines in the music.

The first shot shows a woman ascending a staircase (pre-echo of the cheongsams in In the Mood for Love), and we pan quickly to Andy looking up after her before setting out down the corridor, where he passes a man with a snake.

Track left with Andy in medium close-up, wiping sweat from his face, then cut to an out-of-focus shot of him still walking.

Andy rounds a corner and proceeds down the hall, extending his hand to the wall. In one of those pseudo-matches, another hand slides open a door, as if completing his gesture. We see a card game inside. The framing suggests Andy’s point of view, but the camera glides back.

In close-up, a hand holds a cigarette. A slight tilt and rack-focus reveals that the card player is Andy.

Suddenly, there’s an out-of-focus shot of the snake sliding along the man’s arm; the shot lasts only 16 frames, or two-thirds of a second. (Here I go again, frame-counting.) This is followed by a blurry shot, only 19 frames, of Andy turning his head. It’s almost as if the snake-shot had attracted Andy’s peripheral vision.

The man with the snake, still out of focus, rises and goes behind a curtain. Cut to a shot of a light bulb shielded by a scrap of paper, with cigarette smoke wafting up.

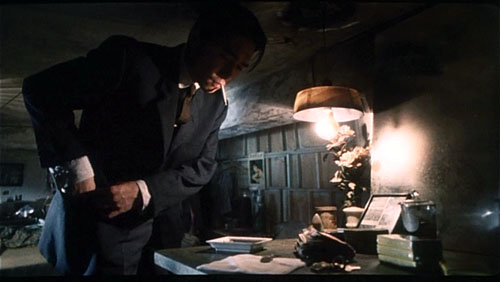

A classic misterioso shot: A powerfully built man in a suit, seen from the rear, dominates the composition, and the camera tracks back from him. But instead of revealing his identity, the narration cuts back to Andy, who, out of focus, turns back to the game.

A new phase of the sequence starts. The camera pans up a rock wall, showing water trickling down it. Confirming that we’re back in the corridor, we see a hand seizing a chopper from a wall rack. There’s an odd effect of matching movement, with the pan upward picked up by the upward-lifting movement of the cleaver.

From another angle, the hand draws the cleaver across the frame.

Now we get opposing lines of movement—up and to the right in the first chopper shot, horizontally to the left in this shot. The rhythmic bump is accented by the brevity of the shots (30 frames, 21 frames). At the end of this second shot, we can glimpse someone walking away in the dark background.

The cleaver shots are followed by a close-up of Andy walking along the corridor, much like those at the start of the sequence. The final shot shows him walking far away from us. This take seems to be a continuation of the earlier one, when he put out his hand against the left wall. It fades out as the song does.

After the fade-out of Andy walking down the corridor, the credits resume and the scene introducing Yuddy and Lai-chen begins the main plot.

Wong had used a music montage in As Tears Go By (the remarkable “Take My Breath Away” sequence, which I analyzed in Planet Hong Kong). But there it functioned as a lyrical commentary on a sharply delineated, somewhat conventional narrative situation: Wah visits Ngor in Lantau Island and awkwardly communicates his affection for her. This sequence in Days is puzzling because it doesn’t have very clear narrative import. It does set the mood of languor that dominates the film, but it also hints at a situation of criminal danger (gamblers, the hand with the chopper) that is never actualized in the story that follows.

Coming after the fairly opaque opening shot of Tony, this sequence poses other questions. We’ll later learn that Andy is a diligent patrolman; what’s he doing in this den of thieves? Local audiences would recognize the location as the Kowloon Walled City, a sort of island of sheer criminality in the middle of Kowloon. Was Andy an undercover cop before taking up the uniform?

And who is seizing the cleaver? At first I thought it was Andy, but closer inspection shows that’s not likely; there’s nothing in his hands in the final extreme long-shot. Is someone stalking him? We never find out.

Wong is fond of giving us mere impressions of events, sometimes linked to characters’ consciousness, sometimes soaring cadenzas of images blended with music. But unlike the music montage of As Tears Go By and those in later films, this one is almost indecipherable in story terms. Nothing else in Days of Being Wild is as free-form as this stretch of footage. It can stand as an emblem and limit-case of Wong’s interest in using genre conventions poetically, and his reluctance to pay them off in plot terms.

Partial solutions, more mysteries

Back in 2001, Shelly Kraicer, impresario of the Chinese Cinema List, wrote about having seen this version, and several people chimed in with their recollections and opinions. In 2004, I asked several Hong Kong friends about it. Filmmaker, critic, and educator Shu Kei, who has a long memory for Hong Kong film, replied:

I remember the footage you describe. If I’m right, this was the version WKW re-edited after the disastrous midnight premiere of the film, and it was the “official released version” for the regular shows in the following week.

Days was released on 15 December 1990 and played until 27 December, so perhaps this was indeed the version that was seen in its Hong Kong run. In 2001 correspondence on Shelly’s list, Bérénice Reynaud, who saw the “pre-premiere version” of a print straight from the lab, was “positive” that the prologue material was not in that print.

Shu Kei offers some further information about the gambling sequence:

The shots with Andy Lau in a card game and fighting afterwards [sic] were done in a very early stage of the film’s lengthy shoot, in which Lau was playing a gangster-like character in the Kowloon Walled City. (The role, and much of the original concept of Days of Being Wild, were reprised in Jeff Lau’s Days of Tomorrow, 1993.) Andy’s character was later changed to that of a cop.

Two other Hong Kong observers told me that the revised version was designed to make sure that the big stars Tony Leung and Andy Lau had early and prominent entrances, since without the prologue, they play minor roles. Michael Campi reported in the 2001 correspondence: “I was told that in a frantic attempt to retrieve some revenue from the film, it was decided crassly to include Leung Chiu-wai in the opening as well as the closing.”

If this was the strategy, it’s reminiscent of the changes made to the international (originally, Taiwanese) version of Ashes of Time, with the prologue and epilogue showing explosive fighting scenes. Those passages were designed, explains Hong Kong Film Festival programmer Li Cheuk-to, to assure viewers that there would be swordplay in this rather talky movie.

Things are far from settled, though. The prologue is a major crux, but assuming that the last reel I saw was that of the 1990 retooled version, how do the circumstances outlined above explain the disparities in the endings? Why would audience dissatisfaction or producers’ demands force Wong to eliminate the empty shots of the stadium and the clock? Or substitute a different (and more opaque) scene of Lulu in the Philippines? Or change the découpage of the train dialogue between Yuddy and the cop? Or supply a different long shot of the train? Or eliminate the haunting “Perfidia” theme?

Moreover, we still don’t know what the premiere version screened at midnight shows was like. Was it congruent with today’s international version, or was it yet a third variant? In other words, did Wong un-revise the original, or re-revise it? At what point did he or his distributors replace the obscure version with the one in general circulation?

Earlier in June our blog discussed Grover Crisp’s visit to Madison, in which he argued that in an important sense every film exists in alternative versions. We simply have to accept that. It’s especially true of Hong Kong films, which are recut for circulation in many markets. And I like knowing that there’s an especially puzzling variant of Days of Being Wild—one that lets us imagine virtual narrative possibilities and adds to the appeal of this enigmatic movie. Nonetheless, I’d welcome more information about all this, especially from Wong Kar-wai himself.

(1) Stephen Teo, Wong Kar-wai (London: BFI, 2005), 45.

Thanks to Alex Wong for translating the prologue’s voice-over narration for me.

The boy in the Black Hole

PTU.

DB here:

Films from Hong Kong’s Milkyway company earn a lot of praise for their visual qualities. Shooting in Technovision, Johnnie To Kei-fung and other directors have created some of the most vivid and fluid imagery in contemporary cinema. But the movies have soundtracks too. What about them?

When I saw Tsui Hark’s Time and Tide (2000), I staggered out exhausted. I was overwhelmed not only by the delirious plot and its cascade of feverish imagery—who else puts the camera inside a dryer at a laundromat?—but also by what seemed to me the most elaborate soundtrack I’d ever heard in a Hong Kong film.

Shortly after seeing the movie, I visited the Milkyway headquarters and met Martin Chappell, the sound designer of Time and Tide. (For his credits and his company information, go here.) I figured that he could help me hear more in all movies, not just his own.

Years later, during my spring visit to Hong Kong, I got my wish. Martin gave me an interview and sent me several information-packed emails. As I’d hoped, he taught me to listen better.

At the console

Martin Chappell is a concussive burst of enthusiastic energy, an impression aided by the fact that he looks about sixteen. He loves moviemaking and sound design. Growing up in England, he started as a bass guitarist and audio fan, and he studied music and acoustics. When he graduated he worked in sound studios and became a roadie. After a year in Australia, he moved to Hong Kong and got a job in a radio station.

Soon he was working at TNT, creating sound effects for cartoons and dubbing American movies into Mandarin. Hired briefly away by MGM, Martin then shifted to Milkyway. His first effort there was helping on the mix for The Intruder (1996).

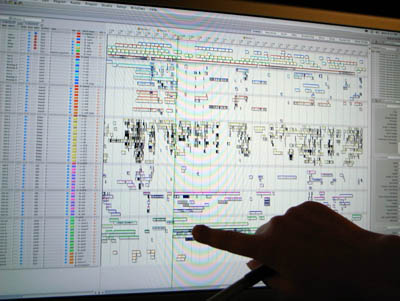

Now, with over fourteen years of audio engineering experience, he is sovereign of sound at Milkyway. Ensconced at the heart of Milkyway’s facility, Martin presides over what he calls the Black Hole. The company’s sound studio consists of several rooms, including a Foley studio that is a black hole within the Black Hole.

By Hollywood standards, these studios are minuscule. (Compare the mixing theatre I visited last year for 3:10 to Yuma.) As usual in Hong Kong cinema, work must be fast and tight. Martin typically has a sound crew of three, sometimes including Foley artists. Postproduction sound is usually allotted three weeks, sometimes a little longer. Often he has to prepare a mix on short notice so that visiting critics, festival programmers, or backers can preview a work in progress. As a result, Martin can be found in the Black Hole far into the night, blasting through reel after reel.

Waiting for no man

Most Hong Kong films have a bare-bones approach to sound: dialogue, music, and minimal effects. The sort of detailing that Hollywood offers, especially in Foley techniques, has not been common. There simply isn’t the time and money for a densely mixed track. A lot of time has to be allotted for dubbing the film twice, once in Cantonese and once in Mandarin for the mainland and overseas Chinese market. As a result, even the best Hong Kong films often have a dry, vacant ambiance, which is commonly masked by music. (Perhaps the wall-to-wall music in Wong Kar-wai’s films is an effort to supply a rich sound texture in the absence of other options.)

But Time and Tide had more resources. As part of a Sony initiative to expand into Asian production, which also yielded Crouching Tiger and Kitano’s Brother, it had a large budget by Hong Kong standards. Martin had three months for sound postproduction, “the longest schedule I’ve had in my life,” and a sound crew of eight.

Martin found Time and Tide “a beautiful learning experience.” Working around the clock under the tutelage of veteran postproduction supervisor Hui Koan (The Blade, The Legend of Zu), Martin was encouraged to take chances. He could create rich Foley tracks—remember the tinny ricochet of the little boy’s abandoned skateboard?—and he borrowed ideas from Fight Club, Gladiator, and The Matrix. He was layering sound in the Hollywood manner, albeit on a smaller scale. And he pushed toward wilder possibilities. He recalls the pleasure of putting jungle bird calls under early shots of clubbers wandering through nighttime traffic.

Out and about

Hong Kong looks lovely, but Martin thinks that it’s just as breathtaking in its noise—“a rich sonic soup.” Virtually every chance he gets, he heads out to record in the field.

I pretty much never leave home without my Edirol R-09, and I have a Zoom HR for portable hard disc recording.

It’s important to have a recorder with you all the time. You never know when some drunk is going to burst into song whilst lying in the gutter. In Sparrow, Simon Yam challenges Ka Dung to steal the cop’s handcuffs when they’re outside a bar late at night. So I just pulled the recording I’d made earlier of some drunk guys singing karaoke. It was late one night, I was walking back from the pub, and I heard it echoing out an alleyway.

I feel I’m incredibly lucky. I went out one night to get fresh recordings of a minibus for Linger. I’d scouted the spot, but when I got there the heavens opened and I didn’t have an umbrella. I ran to a nearby bridge—serendipity. I realize it’s next to a tram road, so I recorded buses and trams in the rain, and these sounds feature prominently in Sparrow.

Martin’s wife Marisha often comes with him, either operating or providing effects herself. Recording on the fly freshens up his library, and keeps him alert to new possibilities.

I’m always hoping for a gift from the Ear in the Sky. I’m actually trying to type quietly now, but there’s a band playing downstairs and it’s coming through the walls. They sound terrible, but I think it could be used for a bar scene—late night outside somewhere? . . .

You can see Martin on location in a two-part TV show here.

Back in the studio, Martin revels in software like his Digital Performer and Propellerhead Reason programs. His setup isn’t a Mercedes, like ProTools, he says, more of a Lexus—but in some ways it’s more flexible than the more famous option. Johnnie To wants rich tracks, so “Now I spend almost all my time on Foley and ambience.” Martin “finds the flavor” of the sound through his synthesizer.

I load a recording into Reason and I can play with it in real time on my keyboard—pitching it up or down, sweeping the filters, tweaking the equalization. I do so much with ambiance like this. Sometimes I tie it to the picture, other times I just play on a whim. . . . It’s almost fun.

Alongside his high-tech equipment, Martin employs some home-made items, such as his gobo panel, an upright mesh of stones that is virtually a sculpture (above). The gobo can muffle or redirect sound. Placed between two sources, it can allow clean recording of each track.

Every gun makes its own music

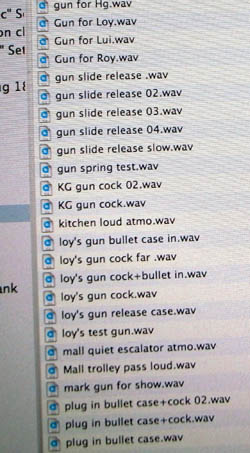

In The Mission, each of the five bodyguards gets a different pistol. Martin gave each one a different sound, labeled in his files by the actor’s name. Here “Roy’s gun” is sometimes coded as “loy’s gun,” and there are plenty of other discrete sound bits on file.

I asked Martin about the mall shootout, which has become a classic in the genre.

There seemed to be so much space in there, and we were adding artificial reverbs, but none of them seemed to work real well. That’s when we decided to experiment a bit, developing things we’d tried in A Hero Never Dies. We just put in the tail of a cannon firing. So that phrase “Bring out the big guns” is literally true here.

There was also a really long gap between some gunshots. We tried adding more, but it felt too busy. So we tried lengthening each gunshot, with the cannon tail reverberating. But that still wasn’t long enough, so we started playing with it, almost jamming with the music. We time-stretched the cannon tails, not just a bit like you’re supposed to. It gave a very artificial but tense sound. If you think it’s music, it might well be.

But even then it wasn’t long enough. So before the next pistol shot, we actually reversed the cannon sound. We get the reversed echo first, then we hear the shot itself! It feels like time has slowed down, then speeded up.

Martin might also have mentioned that these wavering gun reports swoop across left and right channels, creating a dynamic acoustic space for cinema’s most static static gunfight.

Martin also shared his thoughts on the role of sound in fleshing out characterization. After reading Walter Murch’s book In the Blink of an Eye he began to think about how to use sound subjectively. The result was the PTU scene in which Lam Suet, head bandaged, smoking in his car, suffers auditory hallucinations.

Martin acknowledges that there are plenty of conventions that audiences would miss if they weren’t present. When a character hangs up the phone on another character, the disconnected line is signaled through a beep or hum, even though this seldom happens in real life. Martin would also like to hear mobile phone calls in that “headphone bleed-through” effect. He’d also like to handle dialogue like that, “half-overheard, not fully comprehended.”

Still, he finds ways to bypass conventions. In PTU, when the officer played by Simon Yam is abusing the suspect in the video arcade, Martin avoided the library whacking sound, what he calls “the Foley kung-fu cloth flap.” Simon’s slaps are synched to explosions, whizzing missiles, and other arcade sounds. (I offer a visual analysis of one scene in PTU here.)

Ear in the sky

Martin believes that in most films, there’s an immediate need to establish the setting, the placement of the characters, and the scene’s mood. This is done through images, of course, but sound plays an important role. Often a wide shot orients us generally, while sound focuses on one zone of action in that space. “I would guess if you watch TV with no sound, it would be very difficult to really focus. Sound can bring out the visual and guide the eye.”

As an example, Martin walked me through a few moments in Sparrow. The elusive Chun Lei has gulled a quartet of pickpockets, and they pursue her to a rooftop. As the men explore it, we hear traffic and a distant plane, which evokes Chun Lei’s plan to flee Hong Kong.

They spot her on the roof. The suggestion that she might jump is underscored by distant traffic horns.

As the men approach Chun Lei, Martin added distant sirens and a soft wind.

An extreme long-shot provides a still broader sound canvas, with traffic sounds predominating.

In a much tighter shot, as the actors come closer to the camera, the ambiance thins and softens. “Now we time the traffic to underline the dialogue.” Chun Lei leans forward to kiss Bo, trying to provoke the leader Kei to jealousy. We hear echoes of a passing truck, almost as a warning.

Only professionals would probably notice these maneuvers, and there’s a reason. Martin thinks that sound can bypass the conscious mind, working directly on our most visceral impulses (fight or flight?). In this he echoes Gary Rydstrom, quoted in an earlier blog of ours: “Film sound is the side door to people’s brains.”

I’m grateful to Martin for all the time and effort he put into our interview. Next time I see a Milkyway film, or any movie, I’ll listen harder. You too?

Photo by Martin Chappell.

Goodbye to Hong Kong for another year

My Heart Is That Eternal Rose.

DB here, yet again:

Back nearly a week from Hong Kong, I’ve been swamped by backlog and made logy by jetlag. But I wanted to offer last-minute notes from this year’s film festival. I won’t comment on the films that disappointed me or that weren’t in finished form. Instead, upbeat reports, some pictures, and a trio of DVD delights.

On the big screen

Little Cop (1989) starring and directed by Eric Tsang, was part of the festival’s tribute to him. It’s a silly but ingratiating item that anticipates Stephen Chiau’s mo lei tau nonsense comedy. The opening credits are burned onto Tsang’s pudgy body, and thereafter a series of episodes takes him to the anti-prostitution squad (cue the condom jokes) and then the drugs detail. There are engaging gags around a funeral, with a song in praise of death set to the Colonel Bogey march, and lots of intrigue with a master criminal who can steal other people’s faces. Needless to say, since this is Hong Kong, we get many food gags too. Eric called in his bets and got a flurry of walk-ons from top stars like Andy Lau and Maggie Cheung. The only tedious stretch is the last scene, an uninspired clone of Steve Martin’s Absent-Minded Waiter routine. Otherwise, good dirty fun.

Paranoid Park (2007) seemed to me Gus van Sant’s best film in a long time, after the somewhat arid exercises of Gerry and Last Days. Here he’s got a genuine, gripping story that he can render in his detached but lyrical style. The shot of Alex in the shower is particularly gorgeous, and the tracking shot of his tormented walk through town is enhanced by swarms of subvocal recriminations that spurt out from all three channels. My friend J. J. Murphy has provided further commentary on his blog here and here.

If movies about moviemaking risk narcissism, movies about film school must be narcissism squared. The Early Years: Erik Nietzsche Part 1 (2007) centers on a young filmmaker who is transparently Lars von Trier. In-jokes about Danish film culture pile up, and the plot takes almost every easy way out, but Jakob Thuesen keeps the proceedings moving briskly enough. The caricatures are fun, although I think the all-night frenzy of film school life is better captured in Yanagimachi Mitsuo’s Who’s Camus Anyway?

A real revelation: And the Spring Comes (2007, above), by Gu Changwei. A somewhat homely woman with a crystalline singing voice imagines herself headed straight for the Beijing opera. Instead, broken love affairs and unwillingness to lower her ambitions keep her sequestered teaching music in a small town. A tough but touching melodrama rendered in a tactful style, with female lead Jiang Wenlei willing to be unsympathetic.

Many art movies can seem inert in their storytelling—over-under-dramatized, we might say. Carlos Reygados’s Silent Light (2007) escapes this trap. Slow and static, it is suffused with a stark calm that gives gravity to a love affair between a stolid farmer and a woman who runs a café. Planimetric compositions are used imaginatively, and the soundtrack makes daring use of offscreen noises. As an old Dreyer fan, however, I have to worry about the film’s relation to Ordet. Dreyer’s film isn’t exactly ripped off or cited, but it floats behind this one like a spectre before materializing at the climax, perhaps in overbearing fashion. Ordet, suffused with religious debate, earns its miraculous finale, while Silent Light, for all its austerity, is a film of the flesh, and its spiritual coda seems to me somewhat forced. But I’m willing to be convinced otherwise.

Because another guest didn’t appear, I was asked to introduce programs of films by or related to Maya Deren. I enjoyed the chance to see them again, and to reread her writings in the excellent collection Essential Deren. Her work remains stimulating—especially Meshes of the Afternoon and Ritual in Transfigured Time. Her writings blend a stringent formalism, echoing Rudolf Arnheim‘s views of cinematic specificity, and a fascination with myth and non-Western cultures. The boys’ Trance movies (Fragment of Seeking, The Cage, The Potted Psalm) are of historical interest, but hers remain lively. I was happy to see how many young people stayed after the screenings to discuss films that are sixty years old.

On the small screen

In my shopping, I discovered three fine movies on DVD.

*Do Over, a Taiwanese network narrative I liked in Vancouver back in 2006, now available with English subtitles in a so-so transfer (good color and contrast, blurry frame-by-frame pickup). A strong debut film from Cheng Yu-chieh.

*My Heart Is That Eternal Rose, an important 1989 Hong Kong film by New-Wave talent Patrick Tam. This mix of romance and crime stars Kenny Bee, Joey Wang, and a shockingly young Tony Leung Chiu-wai, and Christopher Doyle is listed as one of two cinematographers. The film’s daring stylization marks it as belonging to Hong Kong’s late-80s burst of creativity, and many moments look forward to the luxuriant melancholy of Wong Kar-wai. Clearly Tam (who edited Days of Being Wild and Ashes of Time) was an important influence on Wong. For a long time, I had access to My Heart only on an ugly pan-and-scan laserdisc, but now a widescreen transfer of a worn but bright print offers a considerable improvement. It’s far from perfect, with somewhat slurred movement, but better than nothing.

*Play while You Play, usually known as Cheerful Wind (1981), is Hou Hsiao-hsien’s second film, a romantic drama about a blind man and a somewhat self-indulgent television producer. It’s one of his three commercial “musicals,” and seldom seen, let alone discussed. I think that stylistically these films lay the groundwork for his Taiwanese New Wave films from The Sandwich Man onward. (Go here for more.)

I don’t enjoy this quite as much as his first film, Cute Girl, or his third, The Green, Green Grass of Home, which seems to me nearly a masterpiece. Still, there are lovely moments in Cheerful Wind, including the music montages and a surprisingly offhand ending. Hou films almost casually in the open air, letting passersby drift in and out of the frame (above). The disc, from something called Hoker Records, claims on its package to be 4:3, but it actually preserves the 2.35 format. Unfortunately, it does so through letterboxing, yielding only so-so resolution. No English subtitles. Rumor has it that the irresistable Cute Girl is available in a similar package.

In the point-and-shoot LCD

Four of the brains behind the festival: Ivy Ho, Bede Chang, Li Cheuk-to, and Albert Lee.

Shan Ding, man of all work at Milkyway Image, and the magisterial Peter Greenaway.

Mrs. Johnnie To, Johnnie To, Amy Lau, and Lau Ching-wan, who normally eats nicely.

Joanna Lee, translator extraordinaire and music facilitator to the world.

Jupiter Wong, ace photographer, and Bela Tarr after the enthusiastic reception of The Man from London. My takes on Tarr are here and here and here.

Peter Chan, whose Warlords just won a slew of prizes at the Hong Kong Film Awards.

Jacob Wong, Festival programmer, and Raymond Phathanavirangoon, lately of Fortissimo. I praised Raymond’s presskits last year.

Shu Kei and Michael Campi, just before the premiere of Coffee or Tea, which Shu Kei directed with Kwan Man-hin.

Tourist snap no. 1: Wherever you turn in Wanchai, there’s something interesting to see. Even air conditioners start to look like public sculpture.

Tourist snaps 2 and 3: I often took the Wanchai ferry to screenings on Kowloon.

Tourist snap 4: Coming back late from a screening on the Kowloon side, I would walk past the old clock tower.

. . . A walk fortified by a late-night sample of the Sweet Dynasty’s almond and walnut soup.

In all, as I said at the start of my 3 1/2 weeks here: This will always be the place.