Archive for the 'National cinemas: Hong Kong' Category

Modest doesn’t mean unambitious

DB still in Hong Kong:

There are plenty of big attractions at this year’s festival. After seeing Om Shanti Om (wildly enjoyed by the audience), I was standing outside the theatre at the Cultural Centre and intersected with hordes of teenagers running to get seats for Candy Rain, a Taiwanese movie starring pop songstress Karena Lam. The result was the Wong Kar-wai homage above.

But many of the best films at this year’s festival don’t come on strong. They simply trust that you will pick up on their quiet virtues. One example is In the City of Sylvia, which I saw at Vancouver and wrote about here. There are others too.

The way we live now

In my previous entry, I mentioned three main sorts of HK films being made these days: programmers, auteur films, and epic coproductions. I neglected a fourth category, that of the small-scale film commenting on local life and history in a heart-warming, nostalgic vein.

Every year a few of these are made, usually attracting a small public. Examples would be Herman Yau’s From the Queen to the Chief Executive (2000) and Give Them a Chance (2006), Samson Chiu’s Golden Chicken (2002) and its sequel (2003), and last year’s Mr. Cinema, a gentle history of Hong Kong from the standpoint of an idealistic movie projectionist. An older example is the sweet-natured Umbrella Story (1995), which integrates CGI footage of Bruce Lee and other stars. Golden Chicken found box-office success, but mostly these projects attract a small public at home and an even smaller one abroad. They don’t, as the saying goes, travel well.

An ambitious example of the grassroots Hong Kong movie had its premiere last week. Ann Hui’s The Way We Are is remarkably bereft of ordinary plotting and dramatic conflict. A widow raises her teenage son in a high-rise apartment in Tin Shui Wa, a district in the New Territories. She works in the fruit section of a supermarket, while he waits for the results of his high school examinations. They meet an old woman living in the same building and they get somewhat involved with her personal problems, the chief one being a hostile son-in-law.

The widow’s mother takes sick. A distant relative dies. An uncle promises to pay for the son’s overseas education. The film refuses to exploit the traditional dramatic potential of any of these situations. There is no tragedy, no sudden burst of violence, no slaps or wails or shattering confrontations. This is a movie in which, by the standards of traditional dramaturgy, nothing happens.

The widow works hard, but she isn’t made saintly; she’s just a kind, devoted person, wearing a perpetually alert half-smile. The son seems at first to be wasting his summer by lounging about, but he dutifully runs errands and takes responsibility for helping his hospitalized granny. The Way We Are makes Edward Yang’s Yi Yi look melodramatic.

The bulk of the film consists of people simply passing their time—working, meeting family and friends, and above all eating. The Way We Are must have more food scenes than any other movie in history. We watch food wrapped, chopped (durians especially), cooked, and consumed. There aren’t many Hong Kong movies that don’t feature food scenes, but this movie puts eating front and center. Again, though, feeding your face doesn’t get the comic or dramatic charge it has in classics like Michael Hui’s Chicken and Duck Talk or Tsui Hark’s Chinese Feast. Eating is just another routine.

Ann Hui has created perhaps Hong Kong’s closest equivalent to Ozu: a film in which daily life, unemphatically presented, is sufficient to engage our sympathies. Granted, The Way We Are lacks Ozu’s formal rigor, his habit of mirroring situations through composition and color design and auditory motifs. Shot on HD in longish, straightforward takes, Hui’s film risks seeming as mundane as its subject. Still, her impulse seems akin to his: a delicate search for human kindness in the commonplace. A title of another of Ann Hui’s films would do for this one: Ordinary Heroes.

Ann Hui has created perhaps Hong Kong’s closest equivalent to Ozu: a film in which daily life, unemphatically presented, is sufficient to engage our sympathies. Granted, The Way We Are lacks Ozu’s formal rigor, his habit of mirroring situations through composition and color design and auditory motifs. Shot on HD in longish, straightforward takes, Hui’s film risks seeming as mundane as its subject. Still, her impulse seems akin to his: a delicate search for human kindness in the commonplace. A title of another of Ann Hui’s films would do for this one: Ordinary Heroes.

The project began as a much grimmer story based on a brutal murder in the neighborhood. But Ann couldn’t bring herself to shoot the script. Investigating Tin Shui Wa, she realized that it was “similar to the squatter huts of the 1950s or the resettlement areas of the 1970s. It is very Hong Kong.” Like the other grassroots films, it recalls earlier periods, using a few judicious montages of stills of people at work and play. It is nonetheless a film about today, showing local life with quiet optimism and good humor. Ann still hopes to shoot the original script as a dark companion piece, creating “a complete statement” on contemporary ways of living. (1)

Two other low-key titles

The Pope’s Toilet (Enrique Fernández, César Charlone). The Pope is visiting Uruguay, and a smuggler decides to build a pay toilet for the hordes who will be swarming into his little town. The intrinsic comedy of the situation is nuanced by the serious portrayal of Beto’s failings, his wife’s patience with his intransigence, and his daughter’s hope of escaping her cramped life. How can you not like a film with a man frantically cycling home, a commode lashed to his bike? A touching surprise that would brighten up any festival’s roster.

Milky Way. I admire Benedek Fliegauf’s Dealer (2004), a nightmarish chronicle of a drug dealer’s hectic final hours, and especially the imaginative network narrative The Forest (2003). This last is a must-see for its careful construction and its moment-by-moment eeriness.

So I was eager to catch Fliegauf’s latest, Milky Way. It consists of ten shots, each one a distant tableau showing a landscape punctuated by human presence. The action develops through minuscule changes, often in a comic direction. Fliegauf compares his compositional strategy to the online game Samorost. To me it recalled Structural narratives like Jim Benning’s 11 x 14 and perhaps owes something to Kiarostami’s 5. On the whole it seemed to me not as original as his earlier works. Still, without words, presenting gorgeous imagery and evocative noises, the film tries for nothing more than a series of calmly unfolding visual conundrums. As Fliegauf remarks, “I think that this film quiets the mind.” (2) That’s something worthwhile in these days of all-out cinematic assaults on your brainstem. Yes, I am thinking of Transformers.

More to come this week–many more films, plus at least one interview with a filmmaker.

(1) Quoted in “The Way We Are,” program notes in catalogue for The 32nd Hong Kong Film Festival (Hong Kong, 2008), p. 94.

(2) Quoted in “Milky Way,” festival catalogue, 189.

Ann Hui before the premiere of The Way We Are.

PS 6 April 2008: Thanks to Mike Walsh for a correction on an earlier version of this entry.

News from the fragrant harbor

DB here:

For those of you who have had problems connecting with this site: Sorry! Our server was down for a couple of days. Ironically, I was one of the last to climb on. Hence the slight delay in this posting from the Hong Kong International Film Festival.

Whither Hong Kong film?

The Warlords.

Local cinema is still in the doldrums. As in most countries, Hollywood rules the box office. Production has dropped to about 50 releases last year, and the quality of what I’ve seen over the last week isn’t on the whole strong.

I’m told by a film professional who follows things closely that critics feel that 12-15 local films from 2007 are worth seeing and about 5 are actually good. Those five are Ann Hui’s The Postmodern Life of My Aunt, Derek Yee’s Protégé, Johnnie To’s Mad Detective, Yau Na-hoi’s Eye in the Sky, and Peter Chan’s The Warlords. It’s significant, my friend indicates, that almost never before has the same clutch of films been nominated for best picture, best screenplay, and best director at the Hong Kong Film Awards. (The awards will be given on 13 April.) “The falling industry has reached a plateau,” she remarks.

My sense is that Hong Kong cinema is sustained, however minimally, on three levels. As usual, there are the program pictures, chiefly urban action films and romantic comedies and dramas. These come and go, using local singers and TV stars, and allow theatres to keep their doors open. More creative are the films from local auteurs, principally Johnnie To Kei-fung. (Should I count Wong Kar-wai as a local filmmaker any more?) To’s Milkyway company turns out several worthy items per year, most directed by To. As I indicate in an earlier post, The Sparrow is their upcoming release; it’s also the best Hong Kong movie I’ve seen so far on my trip.

A third category includes the increasingly important China coproductions, nearly always military costume dramas. The emblematic shot: Mighty warriors on mighty steeds galloping toward the camera in a telephoto framing. Add spears, swords, shields, and slow-motion to taste.

The Warlords is the prime instance from last year, but it was preceded by The Myth (2005) and A Battle of Wits (2006). The genre was made popular by Mainland movies like Zhang Yimou’s overdecorated epics, and it has already furnished us two spring releases, An Empress and the Warriors (yes, you read that right) and The Three Kingdoms: Resurrection of the Dragon. Both are straightforward tales of military struggle, centering on loyalty and honor, with relatively little of the palace intrigue that usually furnishes plot motivation.

An Empress, starring Donnie Yen, Leon Lai, and Kelly Chen, is pretty thin going, with overhasty fight scenes and Bumpicam coverage. The only engaging element, apart from the porcupine armor on display in the ads, is the fact that Leon plays a warrior who has retired from the world. He has for obscure reasons turned his patch of the forest into a launching pad for a hot-air balloon. Still, when ninja-like invaders assault his rickety scaffolding, we get a fairly effective action scene that carries a little of the impact of director Ching Siu-tung’s best movies.

An Empress, starring Donnie Yen, Leon Lai, and Kelly Chen, is pretty thin going, with overhasty fight scenes and Bumpicam coverage. The only engaging element, apart from the porcupine armor on display in the ads, is the fact that Leon plays a warrior who has retired from the world. He has for obscure reasons turned his patch of the forest into a launching pad for a hot-air balloon. Still, when ninja-like invaders assault his rickety scaffolding, we get a fairly effective action scene that carries a little of the impact of director Ching Siu-tung’s best movies.

The Three Kingdoms, a Korean-China coproduction directed by Hong Kong’s Daniel Lee, is a somewhat more impressive item. The plot traces the rise of a general (Andy Lau), aided by his mentor (Sammo Hung), and their confrontation with a rival general, whose cause is taken over by his daughter (Maggie Q). There is little characterization; everything hinges on honor, retribution, and service to one’s superior. A tranquil interlude with Andy’s love interest, a shadow puppeteer, is quickly forgotten in the rush to combat. The musical score channels Morricone, and as in Empress, it employs thunderous drumbeats, chanting male choruses, and a keening soprano. Inevitably, we also sense the influence of Wong Kar-wai in the meditative voice-over and the fight scenes (choreographed by Sammo) that recall Ashes of Time in their slurring and spasmodic rhythms.

Are such films really desired by Asian audiences, let alone Western ones? The jury is still out. Thanks to shooting in China and the diffusion of CGI technology, such genre pieces can be made for much less than Hollywood would spend. Three Kingdoms came in at less than US$20 million, which is twice the budget purportedly spent on Empress. But international sales of the genre are spotty, and audience uptake isn’t overwhelming. Somebody will have to tweak the formula creatively. Will it be John Woo, with Red Cliff? Odds are against it, but I’d like to be surprised.

Incorrigibly optimistic, I’m still looking forward to Ann Hui’s newest film, The Way We Are, premiering tonight, and Coffee or Tea, the collaboration of veteran director Shu Kei and his student Mandrew Kwan Man-hin. That’s the closing film of the festival.

Films briefly noted

Kabei–Our Mother.

Other festival highlights for me:

Please Vote for Me! A primary school in Wuhan is introduced to democracy when the teacher decides that the monitor will be elected by the class. There ensues a struggle all too reminiscent of U.S. political campaigns. We have sound bites, applause lines, political operatives (here, overzealous parents), scurrilous charges, personal attacks, and outright bribery. The collision of human nature and democratic ideals make this a charming and thoughtful movie. I can’t imagine anyone not enjoying it, if only for its reminder of how humiliation feels when you’re nine years old.

Observando al cielo. Jeanne Liotta’s ode to astronomical phenomena, at once scientific demonstration and lyrical tribute to the swiveling of the heavens. Visit her website here.

Observando al cielo. Jeanne Liotta’s ode to astronomical phenomena, at once scientific demonstration and lyrical tribute to the swiveling of the heavens. Visit her website here.

Mauerpark. From the Austrian collective Stadtmusik, Tati-goes-Betacam. A long shot of a snow-covered park is at first puzzling, then amusing, then engrossing.

Alexandra. I nearly always like Sokurov. Yes, the films can be a little overbearing, but they have a certain weirdness that keeps them from pretentiousness. Here he gives us another story of family love. An old lady visits her grandson, who’s soldiering in the Caucasus. She rides in a tank, watches men clean their weapons, and putters doggedly about the bivouac. No big emotional climaxes, unless you count her encounters with other old ladies, who have set up a market selling shoes and cigarettes, and the moment when her soldier tenderly braids her hair.

Alexandra. I nearly always like Sokurov. Yes, the films can be a little overbearing, but they have a certain weirdness that keeps them from pretentiousness. Here he gives us another story of family love. An old lady visits her grandson, who’s soldiering in the Caucasus. She rides in a tank, watches men clean their weapons, and putters doggedly about the bivouac. No big emotional climaxes, unless you count her encounters with other old ladies, who have set up a market selling shoes and cigarettes, and the moment when her soldier tenderly braids her hair.

The weirdness comes in the color values–sometimes blinding orange, sometimes bilious green reminiscent of Sovcolor—and in a murmuring soundtrack that blends machine whirs and conversation with barely discernible swoops of orchestral and vocal music. (Since Galina Vishnevskaya plays the old lady, are these fragments from her performances?) Nobody makes soundtracks quite like Sokurov; even an unadorned shot can take on urgency through the drifting whispers our ears struggle to make out.

Jim Hoberman has a discerning review here.

Elegy of Life. Rostropovich. Vishnevskaya. Also a pleasure to listen to, but much more straightforward. A documentary tribute to the great cellist/ conductor and the singer. Since I’m interested in Russian music and cultural politics, this was an unadorned pleasure. To hear Rostropovich compare Prokofiev the classicist with Shostakovich the Mahlerian was especially worthwhile.

Kabei—Our Mother. Yamada Yoji received a lifetime tribute at the Asian Film Awards. Having directed over seventy movies, including the long-running Tora-san series, he’s usually discussed in terms of sheer productivity. But his calm, grave period films Twilight Samurai (2002), Hidden Blade (2004), and Love and Honor (2006) have reminded people that he’s a fine director too. A man of restraint, he never shoots handheld, he seldom moves the camera, and he uses close-ups as high points, not default values. His sobriety makes the 1.85 ratio look as cleanly fitted to the human body as the 1.33 one is. “The last classical director,” Mike Walsh called Yamada after the screening, and it’s hard to disagree.

Kabei was for me the high point of the festival so far. It’s 1940, and a Tokyo intellectual is arrested for “thought crimes.” As he endures prison, his wife and two daughters struggle to make ends meet, with the help of Yamazaki, a loyal student. An epilogue reminds us of the now-elderly mother’s devotion to her husband.

That’s about it, but the poise of the performances and the simplicity of the presentation make this like a film from the era it portrays. I wish I had a DVD to illustrate the craftsmanship that Yamada brings to the very first shot, which unhurriedly introduces the family while the mother simply hangs out wash on the line. I wish I could show you how the moment that a badminton birdie lands on a rooftop pivots from comedy to sadness. I wish I could replicate the composition that hides a weeping Yamazaki from us—a shot that actually makes the audience burst into laughter. Who else would have the film’s biggest star, Tadanobu Asano, keep his back to us for an entire scene?

But maybe it’s better I don’t give such things away. Best to say: Despite all the other movies you see, Kabei shows one way that cinema can still be.

Finally, as antidote to my somewhat depressing diagnosis of the state of HK film, two items. First, the reception for Sylvia Chang‘s Run, Papa, Run showed off her lively charm. Here Sylvia, in black, is flanked by her stars, Yuhan Liu, Rene Liu, Lewis Koo, and Nora Miao, who played in Bruce Lee pictures.

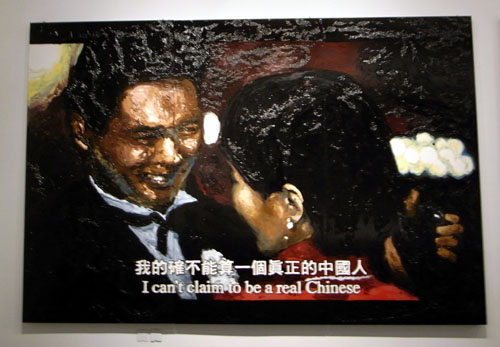

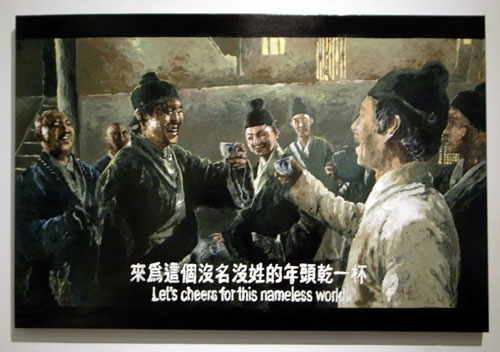

Second, in the entertaining exhibit Made in Hong Kong at the art museum, you will find the work of Chow Chun-fai, whose output includes large, glossy enamel images taken from movies, complete with letterboxing and subtitles (typically about Chinese/ Hong Kong identity). The blocky figures seem both chunkily monumental and somewhat decaying. One of Chow’s huge pictures, derived from Love in a Fallen City, surmounts this blog entry. Below is another, based on King Hu’s Dragon Inn.

More to come in a few days, including, I hope, thoughts on Maya Deren and an interview about sound design in Milkyway movies.

PS later on 27 March: I’ve just discovered a remarkable array of comments on Alexandra in this Criterion thread. John Cope‘s discussion is particularly admirable.

Party time in Hong Kong

Today, pix from two get-togethers during the Hong Kong International Film Festival.

Johnnie’s dinner

Johnnie To gave another of his legendary dinners, this time to a crowd of filmmakers, distributors, festival directors and programmers, and hangers-on like me. The meal was old-school HK fusion, mixing Brit colonial food (boiled tongue, boiled potatoes, boiled veggies) with unique local variations (pigeon, a puffy vanilla soufflé). I think it’s akin to what Maggie Cheung and Tony Leung scarf down so elegantly in In the Mood for Love. Very tasty.

Among those present: Director Kirk Wong.

Kirk made The Club (1981), Health Warning (1982), Gunmen (1988), and other classics, including the 1994 double-header Organized Crime and Triad Bureau and Rock ‘n’ Roll Cop. These are terrific movies, admired by every fan of action cinema.

Festival consultants consult: Mike Walsh (Melbourne, Adelaide); Stephen Cremin (Far East Film Festival of Udine, Screen International); and Todd Brown (S x S W, FantAsia, Twitchfilm).

Cameron Bailey, Co-Director of the Toronto International Film Festival, lets me try an Ozu-style composition.

A small bolt of lightning

One of the most appealing things about Hong Kong film is that character actors, as we call them in America, go on and on, becoming not only stars but directors and producers. As Leslie Cheung pointed out, the local audience is loyal to its favorites and encourages them to try many things.

Eric Tsang, the short, cherubic guy with the perpetually hoarse voice and blinding smile, began, surprisingly, as a soccer player. In 1974 he became a bit player and stuntman in Shaws’ martial-arts releases. He directed two of the movies in the top-grossing Aces Go Places cycle (1982, 1983), and rose to become a screen personality. He’s so familiar to Hong Kong movie lovers that we couldn’t call him Tsang; he’s just Eric, and he’s irreplaceable.

He worked steadily and hard, appearing in nine films in 1985 and an astounding seventeen in 1988. Several of his performances are superb: playing a small-time loser in Final Victory (1987), a flamboyantly gay music coach in He’s a Woman, She’s a Man (1994), a philandering policeman in the exhilarating and little-known Task Force (1997), a wistful romantic in Metade Fumaca (1999), and of course an implacable triad boss in the Infernal Affairs trilogy (2002-2003). He perks up every movie he graces, rescuing routine projects with his beaming ordinariness. In a fairly ordinary policier like Cop on a Mission (2001), he starts out as a thuggish menace and becomes not only sympathetic but heroic in his devotion to his errant wife.

Cop on a Mission is one of several of Eric’s films screened in the HKIFF tribute. The event also emphasizes his role as a producer. Thanks to him, we have The Outlaw Brothers (1990), Dr. Mack (1995), Men Suddenly in Black (2003), Jiang Hu (2004), and several films he coproduced with Peter Chan Ho-sum. Most recently, Eric has launched a project to support young directors. He launched Winds of September, a feature trilogy about coming of age in the “three Chinas”—the mainland, Hong Kong, and Taiwan.

For the premiere of Tom Lin Shu-yu‘s Taiwan entry on Friday night, the festival held a little party for several hundred of Eric’s closest friends. For once, that last phrase is no joke; everybody feels close to him.

Glamor to spare: Cheng Pei-pei, of Shaws’ glory days and since, with her daughter Marsha Yuan Zi-hui.

Peter Chan, fresh from the success of The Warlords, chats with Tony Rayns.

Michelle Carey, Festival Editor of the encyclopedic online journal Senses of Cinema and scout for several film festivals. Alongside, Cheung Tat-ming, idiosyncratic young actor; check out his laid-back performance in Once Upon a Time in Triad Society 2 (1996).

Also there were Teddy Robin Kwan, a wonderful actor and pop singer who first made his mark with movies from Cinema City, and Albert Lee, this year’s Executive Director of the festival.

And Eric was as entertaining from the back as from the front.

Next time, I promise more on the movies. I close with two items:

Strangest line of the last twenty-four hours: From inside a hotel room I was passing: “Mom, I haven’t mentioned a threesome until now.”

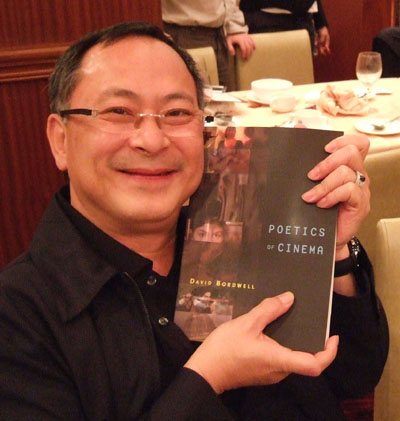

Johnnie To shows himself a man of outstanding taste.

And I show myself a man of no shame. But you knew that already.

THE place

“For us, Hong Kong will always be the place.”

Chuck Norris, The Octagon (1980)

DB here:

Hong Kong’s Entertainment Expo, including the Hong Kong International Film Festival, the Asian Film Finance Forum, and the Hong Kong Filmart, runs for nearly a month, and it has drawn me back to the fragrant harbor. For refreshers, you can visit last year’s posts here.

Biz

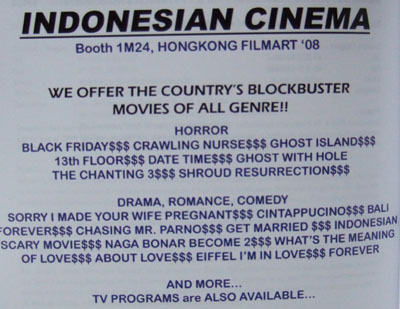

The Filmart has become Asia’s biggest spring media event, with hundreds of companies crowding into a pavilion of the Convention Centre. Here people traffic in movies and TV shows, buying and selling distribution rights, seeking funds for production and partners in movie ventures. I wandered through it last year, and you can track this year’s activities at Variety’s site here.

The last figures I saw indicate that the world pumps out about 4800 features each year. Coming to a market like Filmart, you get to peek below the waterline and see the iceberg that’s underneath.

There are, for instance, the bulk genre items from secondary, or tertiary, producing countries.

There are the films that seem somewhat derivative.

Then there’s the vehicle with the midrange star that just might make it to late-night cable.

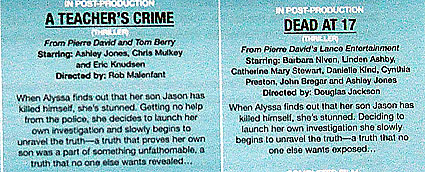

Finally, there are the films that acknowledge themselves to be identical. These descriptions come from Imagination Worldwide’s catalogue ad.

By contrast Filmart mounted a respectful display devoted to Edward Yang, who died last summer. Edward made idiosyncratic, powerful films that would, even today, be very hard to sell at a market. He was a skilled cartoonist, and the display includes some of his perky storyboards and a self-portrait.

The Asian Film Awards, which I covered last year, started things off with a midsize bang Monday night.

The full results can be found here. I was pleased that Secret Sunshine, quite a good film, won three top awards (film, director, actress). Milkyway, a favorite company of mine, garnered a couple of prizes, and The Sun Also Rises, one of my favorites from last year, did pick up the Production Design prize.

Some Big Stars were visible at both the show and the after-party. Heartthrob Tadanabu Asano arrives.

Lee Kang-sheng and Tsai Ming-liang mingle before the awards.

Marco Muller, Director of the Venice Film Festival, at the after-party.

I got to talk briefly with one of my heroes, Hou Hsiao-hsien.

And of course Tony Leung Chiu-wai, emblem of the Entertainment Expo and winner of the Best Actor Award (Lust, Caution), was everywhere, and always looking good.

Within 36 or so hours, I saw quite a lot of movies. With friends Paisley Livingston and Mette Hjort and their kids I caught Enchanted, which pleased me with its schmaltzy cleverness. As part of the Festival, I re-watched on 35mm two movies I’d seen and commented upon last year: Jiang Wen’s The Sun Also Rises and the Tsui/ Lam/ To Triangle. These were shown at the shock-and-awe auditorium of a new cinema in a spanking new mall, Elements. The seats vibrate at the lowest frequencies, creating what is marketed as “4-D.”

At Filmart I saw the Luc Besson production Taken, another satisfying dose of formulaic filmmaking. Altogether different was Manuel de Oliveira’s Christopher Columbus, The Enigma. The title suits this apparently slight film about a historian’s earnest pursuit of Portugal’s influence on North American history. Haunting images of 1940s Manhattan swathed in fog, along with touching scenes of Mr. and Mrs. Oliveira visiting historic sites, linger.

Two films struck me as excellent. Gao Qunshun’s Old Fish (2008) centers on a simple idea. Somebody is planting bombs throughout Harbin, and an aging police officer is the only person remotely qualified to dismantle them. Over a leisurely half hour, we’re introduced to Old Fish, his wife, and his colleagues. Then the first bomb is found, and the suspense kicks in. The apparently clumsy codger, who in an early scene fumbles a World War II grenade, summons up wiliness and delicacy when he has to defuse the mysterious packages.

Two films struck me as excellent. Gao Qunshun’s Old Fish (2008) centers on a simple idea. Somebody is planting bombs throughout Harbin, and an aging police officer is the only person remotely qualified to dismantle them. Over a leisurely half hour, we’re introduced to Old Fish, his wife, and his colleagues. Then the first bomb is found, and the suspense kicks in. The apparently clumsy codger, who in an early scene fumbles a World War II grenade, summons up wiliness and delicacy when he has to defuse the mysterious packages.

I don’t think I’ve ever seen more tension-filled sequences of this sort. The film made me realize that in any bomb-disposal scene, when close-ups of a sweating face and a knifeblade hovering over a wire are followed by an extreme long-shot of the scene—that’s when we expect an explosion. Conventionally, the long shot announces the bang. But here, Gao gives us the long shot, and we have to wait, and wait some more. When the explosion does come, it is genuinely surprising.

Shot by shot and sound by sound, this is a very well-crafted, humane film. If anybody tells you that “foreign films” are digressive and boring, show them Old Fish.

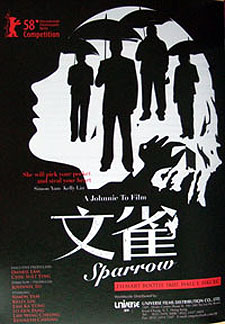

Just as fine, but more unclassifiable, was Johnnie To Kei-fung’s The Sparrow (2008), premiered at Berlin. A gang of pickpockets led by Simon Yam is beguiled by a mysterious lady on the run (Kelly Lin), and their schemes start to fall apart. As often with To, the conception of the film is slim, but the execution is rich. There are the games and competitions, the symmetries and repetitions, the offhand motifs (here, cigarettes, cigars, and pipes), the geometrical and arithmetical plot mechanics. Johnnie To has become perhaps the world’s most unpretentiously, unapologetically formalist director.

It’s a procession of twists and set-pieces. There are the funny one-off shots, like the two grifters with symmetrically broken legs and the gang flashing the razor blades they hide in their mouths. Some sequences are unpredictable miniatures, like the scenes that show how many camera angles you can find in an elevator car, even with a fishtank squeezed in. There’s also a delirious bit with a lipstick-stained cigarette.

Other set-pieces unfold more majestically. There’s a sweeping crane shot of the gang vacuuming up wallets of passersby, and an elaborate theft of a pendant during massage therapy. The climax is an exuberant pocket-picking competition with all contestants stalking through a downpour, their umbrellas forcing them to work with only one hand.

The Sparrow is at once a loving tribute to old Hong Kong island (Simon’s hobby is black-and-white photography), an unpredictable genre piece, and an exercise in light-fingered filmmaking. Like Old Fish, it offers lessons to Hollywood directors, if they have the wit to learn them.

Bits

At Filmart, Fred Ambroisine multitasks, taking cellphone calls and shooting docu footage at the same time.

Deng said “To get rich is glorious,” and now Mao agrees.

And in the spanking new, gargantuan mall known simply as Elements, an entire room is devoted to one essential Element.

More to come, soon I hope, from The Place.