Archive for the 'National cinemas: Hong Kong' Category

RAINING IN THE MOUNTAIN at UW Cinematheque!

Raining in the Mountain (Hu Jinquan/King Hu, 1979).

DB here:

Thanks to friendly distributors, our University of Wisconsin–Madison Cinematheque has sustained itself with virtual screenings every week. Coming up is one of King Hu’s most marvelous movies, Raining in the Mountain. In tribute, I joined Mike King to talk about it in the Cinematheque’s ongoing podcast series.

Best of all, thanks to Film Movement, you can watch the film through our Cinematheque’s virtual cinema!

For a limited time, the Cinematheque offers a limited number of opportunities to view Raining in the Mountain at home for free. To receive instructions, send an email to info@cinema.wisc.edu and simply include the word RAINING in the subject line. No further message is necessary.

Now, why should you watch it?

Well, it’s one of the most visually splendid Chinese films ever made. The Buddhist monastery that serves as the setting was actually assembled by editing together several South Korean locations, all majestic. Add in the brilliant color design and costumes of vibrant splendor, and you get a spectacle that David Lean would kill for.

Among this pageantry we find a cast of rogues, supple-spined thieves, selfish and lustful monks, and a couple of wise elders who see through the vanities of this world. A splashy finish is provided by a bevy of cascading courtesans wielding dazzling crimson and gold sashes–handy for trussing up a thief who has anger issues.

Key scenes take place in the monastery library, but the filmmakers were forbidden to shoot there. In a weird echo of the movie’s plot, the monk in charge was bribed and the crew stole the shots they needed. The footage was whisked off to Seoul, but the stratagem cost the producers a few days in custody.

The plot, as Mike and I discuss, is really three stories in one. There’s a heist scheme, in which a plutocrat and a general compete to steal a rare scroll. There’s a political intrigue, as monks jockey to succeed the retiring abbot of the monastery. And there’s a redemption arc, centering on an unjustly convicted prisoner who struggles to get on the path of righteousness. Much of the film is an attack on worldly selfishness. Even in the monastery, the monks are obsessed with money and have to be forced to do honest work. It’s a film about who deserves power, and right now, in our America, it’s welcome to see pragmatic humility rewarded.

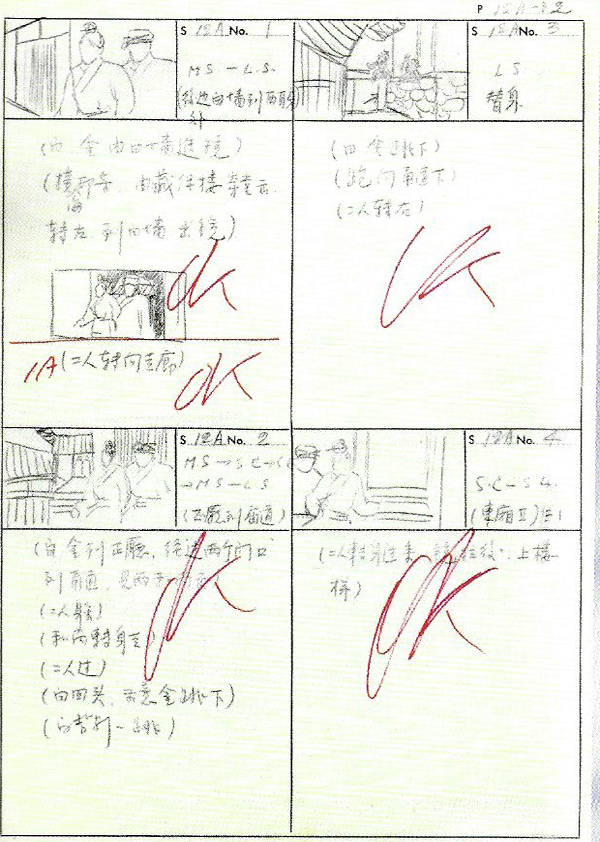

King Hu didn’t finish that many films. He took months to research his projects, and his meticulous planning of costumes and sets made him a slow worker. Unlike many Hong Kong directors, he prepared storyboards and worked out his compositions carefully. As he completed his shots, he checked them off with an “OK,” like the American filmmakers of the silent era.

The connection isn’t accidental. Like a silent filmmaker, Hu had a pictorial intelligence that conceived scenes shot by shot, without the pointless flourishes (arcing camera, slow track-ins) that today’s filmmakers are addicted to. He’s a fast cutter, but his locked-down compositions give you time to see everything.

As a result, Raining in the Mountain is not your typical martial-arts movie. For one thing, what usually counts as action–an aggressive fight, involving punches and kicks–doesn’t come along for an hour. In our conversation, I argue that King Hu replaces fights with zigzag chases, evasions, and hide-and-seek maneuvers. The geography of the monastery gave him vast opportunities for booby-trapped compositions. Figures and faces pop in and out of doorways, corridors, and windows.

The film is designed for the big screen, where details can blossom in distant crannies. So on a monitor (forget the tablet, the laptop, and the phone), you have keep your eyes peeled. While the two thieves drop into a passageway and race into the distance. . .

…a peekaboo framing gradually reveals why they’re hiding: a monk in blue emerges (tiny) in the ledge above them,

The spaciousness of the setting seems to have nudged Hu to try leading our attention to tiny bits of action in the anamorphic frame. Watch how he stages Chang’s preparation for a knife attack in a long shot. Gold Lock is crouching on the left, watching, like us, for the glint of Chang’s blade.

No close-ups are necessary. Hu trusts that we’ll keep up.

As usual in King Hu, there’s a quiet jubilation in watching the calm confidence of fighters leaping from room to room, hopping into a niche, or backflipping under a porch. Hu favors a slow buildup, capped by percussive bursts of action in rhythms recalling Beijing Opera. He cares less about traditional martial arts than about finding ways to create uniquely kinetic dramas of honor, heroism, and protection of the innocent. For him, combat is a staccato dance, and conflict is a test of moral rectitude.

As Mike points out in our conversation, King Hu looms ever larger in film history. A firm line runs from A Touch of Zen to Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000) and Hero (2002), and on to Goodbye, Dragon Inn (2003). Tsui Hark’s swordplay films, especially The Blade (1995), owe a great deal to King Hu. (Not to mention John Zorn’s ear-bleeding album dedicated to the director and his incandescent female star Xu Feng.) King Hu remains one of the most original and engaging filmmakers in world cinema.

Film Movement’s site provides a trailer for Raining in the Mountain.

Thanks to Mike King and Ben Reiser for arranging the podcast, and Jim Healy and Pauline Lampert for coordinating so many superb programs under difficult conditions.

A Touch of Zen (1971-1972), which took three years to make, is King Hu’s official classic, and it displays many of his virtues. It’s now easy to see. (There’s a splendid Criterion disc, and it streams on Criterion and on Amazon Prime.) But don’t neglect his breakthrough Come Drink with Me (1966) and his other “inn films,” Dragon Inn (1968; also Criterion Channel ) and The Fate of Lee Khan (1973; streaming here). Perhaps his most dazzling experiment in action cinema is The Valiant Ones (1975), but I don’t know of any good copies on disc or elsewhere. I’m less enamored of Legend of the Mountain (1975), a ghost story, and All the King’s Men (1982), a tale of court intrigue, but it’s possible I’d like them more if I saw them now.

For more on King Hu, precious documents, essays, and recollections are available in Transcending the Times: King Hu and Eileen Chang (Hong Kong International Film Festival, 1998) and King Hu: The Renaissance Man (Taipei: Museum of Contemporary Art, 2012). The storyboards above come from the Hong Kong volume. I recommend Steven Teo’s deeply informed books on Chinese film, particularly Hong Kong Cinema: The Extra Dimensions, Chinese Martial Arts Cinema: The Wuxia Tradition, and his monograph King Hu’s A Touch of Zen. Hubert Niogret’s fine biographical study of King Hu is on the Criterion Channel.

I discuss King Hu’s work in Planet Hong Kong: Popular Cinema and the Art of Entertainment, in the essay “Richness through Imperfection: King Hu and the Glimpse,” in Poetics of Cinema, and in other entries on this site. In the podcast with Mike, I mention Hu’s ingenious method of making swordfighters disappear and reappear; this entry explains how he does it and includes a clip.

Raining in the Mountain (1979).

Vancouver: Stories, spliced and stacked

Sarita (2019).

DB here:

Humans love stories, the more the better. As a result, many storytellers find ways to bring distinct story lines together. The most common way is to link them, through subplots involving major and minor characters. Viktor Shklovsky urged us to think of folktales, novels, and plays as “braided” out of several story lines. At other times, the stories are bracketed within a bigger plot. A character tells others about incidents in childhood, or characters tell completely detachable tales, as Scheherazade and Chaucer’s pilgrims do. Instead of braiding, we get embedding within a frame situation.

I started to think again about these options watching four films at the always exhilarating Vancouver International Film Festival. All were engaging, partly because they often mixed comedy and drama in rewarding ways. They also offer a nice menu of creative possibilities, exploited by ambitious filmmakers.

Screen life

An omnibus film can offer a frame story, as the British classic Dead of Night does, but most modern ones simply line up one tale after another, in blocks. Essentially these are short stories, and they tend to follow literary patterns.

One option is the “snapper,” the plot consisting of twists and a sting in the tail, a surprise ending. Edgar Allan Poe may have invented this format, O. Henry canonized it, and Roald Dahl gave it a grisly tenor. Diverting examples of the surprise-ending story can be found in the omnibus Spanish film Tales of the Lockdown (2020).

All five modules are comic, though sometimes in a macabre vein. Produced during the COVID-19 lockdown, somehow staged and shot remotely, each episode is cleverly scripted and elegantly directed. In one, a reclusive Milquetoast is pressed by an aggressive neighbor who wants to sell him a plan to expunge “bad vibrations” from his apartment. The Feng Shui saleslady gets more than she bargained for when she learns the source of those vibes.

In another, an aspiring hitman recruited by The Agency gets a remote tutorial from an experienced killer, who makes him practice techniques on a teddy bear and the dogs he snags from the neighborhood. A third, gentler episode is still tricky: we’re led to presume some things about a couple that turn out to be not valid–at least, not until the end. Sorry to be so elliptical, but films like this oblige you to avoid spoilers.

The most straightforward comedy concerns a woman auditioning by video for a TV part, aided by her husband who decides he could get a role as well. For a local audience, the fact that she is played by star Sara Sálamo and her actual husband, a Real Madrid football player, doubtless adds to the fun. The last episode, a black comedy, presents a rich couple’s extreme reaction to a tenant strike in one of their buildings.

The filmmakers have found many nifty ways to exploit the limited viewpoint enforced by lockdown. Naturally, remote conversations take place over laptops, which motivates minimal change of setting and little need for elaborate action scenes, or even ordinary staging in interiors. Offscreen action is likewise conveyed minimally, just by speech or noise in the world outside. The funniest moments in the fifth episode concern the rich couple learning they’ve received a “package” which we never see and must assume is problematic, since the thug on speakerphone says it’s “middle-aged.”

Confined settings have in effect created five “chamber plays” of the kind I’ve talked about before. This constraint allows directors to design and dress settings and find playful compositions to accentuate the plot twists that keep us glued to the screen.

In all, Tales of the Lockdown is a display of light and lively cinema craftsmanship. It’s heartening to see creative energy maintained in pandemic conditions. It premiered on Spanish Amazon Prime and would be worth looking for on that platform in other markets.

Food, memories, and the future

The major alternative to the twisty snapper tale is the “slice of life,” the muted drama of a situation that may change little or not at all. Here the emphasis falls on characters–their relations, their reactions, and their sensitivity to one another. The classic examples come from Chekhov and from Joyce’s Dubliners, but they’re also prevalent in what used to be thought of as the classic New Yorker short story of John Cheever or J. D. Salinger.

Pensive incompleteness of this sort well suits the Hong Kong film Memories to Choke on, Drinks to Wash Them Down (2019). Directors Kate Reilly and Leung Ming-kai have made three of the four stories fictional, treating them as vignettes of restrained realism. A Malay caregiver takes a grandma on an afternoon outing. She wants to go to a political rally where rice will be given out, and she hopes to meet old friends from her village. The old lady is forgetful, and her chatter recycles memories of her youth. The trip turns out to be something quite different, but she doesn’t realize it. The caregiver’s concern turns a simple duty into an act of kindness, as well as a tactful political gesture.

In “Toy Stories,” two brothers meet in their mother’s toy store, which is being sold, contents and all. As with the first episode, memory comes to the fore. The men play games and quarrel about the Power Rangers figures they loved. One, who has a son, tries to find something educational to bring back. He is barely hanging on financially, while his brother has lost his job. A final scene shows a bit of development in their situation, and gives room for a little hope; it’s the only episode that ends, “To Be Continued.”

The third episode is a wistful, Wongkarwai-ish almost-romance. Ruth, an American Caucasian, has come to teach in the school where John, a Chinese, teaches economics. Both are on their way elsewhere–Ruth to teach in Beijing, John to “try something different” in America. They bond over food. (Of course; this is a Hong Kong movie.) From their meeting at a vending machine to the street stalls and cheap restaurants they explore, Ruth learns of the joys of salted egg, pig intestines, and above all yuen yeung, a uniquely local mixture of tea and coffee.

These three stories quietly evoke distinctive Hong Kong culture–the older generation’s memories of moving to the colony, the Gen-X absorption in popular culture, and the particularities of local cuisine. The fourth segment builds on these in looking toward the future.

It’s a documentary showing the barista and cat-lover Jessica Lam running for a local council seat. She faces a pro-Beijing candidate, but she’s more grassroots. She’s also an amateur and runs a fairly minimal campaign. Although she does denounce police violence against demonstrators, the main force of this sequence is the portrait of a sincere young woman trying to improve neighborhood life. This is the only episode with a climax, the election-day vote count. And there is a twist when Jessica gives her final verdict on the results.

The omnibus format has proven a strong option for contemporary Hong Kong cinema, as witness the powerful Ten Years (2015). Memories to Choke On addresses not state oppression, as that did, but the politics of everyday life, the ways in which the sagging economy and the Chinese takeover ripple through the lives of ordinary people. The impact is quite specific: local audiences would know that the actor playing John in the third segment is Gregory Wong Chung-yiu, who is at risk of years of imprisonment for participation in a demonstration. Each story is a telling vignette, a slice of Hong Kong life that will engage overseas audiences and instill a mixed nostalgia in everybody who has ever visited what Chuck Norris in The Octagon (a very different movie) calls “the place.”

Camp as community

The option of embedding the stories within a frame can blur their edges more or less. Sarita (aka Tell Me Who I Am; 2019), an Italian film about refugees from Bhutan living in a Nepalese camp, could have been a straightforward documentary about problems of exile and resettlement under the auspices of the UN. Instead, it blends real-life stories of the refugees with a young girl’s quest to recover her memory. In what filmmaker Sergio Basso calls a more fanciful and energetic approach than a “tragic” documentary would give, we get a film close to magical realism–with DIY Bollywood musical numbers.

Sarita is more or less happy in the camp. She has friends to play and dance with, a school to attend, and every opportunity to worship her favorite god Shiva. But she often quarrels with her parents and wonders why they can’t go back home, a place she has never known. Shiva wipes Sarita’s memory, endowing her with the drive to ask questions of everyone around her. In this Rip van Winkle device, we are introduced to camp routines, as well as the history of her displaced neighbors.

Sarita visits her beloved teacher, only to find that he is often laid low by his injuries from torture sessions. People tell her of ethnic cleansing in Bhutan, of disappeared relatives and political oppression. Deciding that “building my future is easier than desiring my past,” Sarita turns to her immediate prospects. But her sister tells of the hardships of getting a university education. Taking her grandma to be treated for diabetes, she learns of people sleeping in a clinic as they wait days for treatment.

After the family is assigned a home in Oslo, she acquires a super-8 camera and cassette recorder and begins to document the life she will leave behind. Now the world she rejected seems precious. After Sarita has gone, we see her grandmother and those left behind lingering at a tree, studying mementos of their departed neighbors.

Counterpointing the harsh realities of daily routines and homesickness are moments of song and dance, in bursts of brilliant color and gymnastic choreography. We also get fantasy scenes, satires on overeager bureaucracy (the resettlement officer is a hyperactive Gene Kelly wannabe), and signs that youthful exuberance can’t be contained by drab regimentation. We hear “There is no childhood here” on the soundtrack as kids are shown inventing games and playing jacks with pebbles. The ending, however, has the poignancy of pure realism (even though it’s fictitious).

This film is an extraordinary achievement. Basso and his colleagues made it over ten years–filming without electricity and no funding from national governments or NGOs. Yet the minimal conditions enabled close collaboration with the camp residents. Seeing the children’s dances inspired Basso to make it a musical, and he gained access to local leaders. Thanks to the Kuleshov effect, Sarita even appears to interview the head of the resettlement office. Although the performers had some coaching from a theatre director and a choreographer, they clearly have natural gifts, particularly Sasha Biswas, who carries the film.

In the wake of the coronavirus, seventy Italian independent cinemas cooperated in making Sarita available on streaming platforms. There, Basso reports, it has found an encouragingly large audience. Another item to look for on the streaming menu in your area!

Visions of the good life, words of disquiet

One more film about memory, but now the memories themselves are captured on film. And the stories aren’t sealed off in blocks or gently embedded in a wider frame. They’re stacked.

Again, to say too much would soften your efforts to come to grips with the teasing, hypnotic My Mexican Bretzel (2019). Think of it as layered, like a cake.

The image track consists of a Swiss family’s home movies from the late 1940s through the early 1960s. In luscious color we see a couple leading a European life of leisure: summers on the beach, winter skiing, tours of postcard capitals, yummy meals with friends in open-air restaurants. The husband, a genial, brawny fellow, clowns for the camera, but most screen time is given to his wife, a willowy brunette with a radiant smile. The landscapes might have come straight out of Holiday, that oversize American magazine dedicated to worldwide vacationing.

The next layer is a written text, purportedly a diary of Vivian Barrett. This tells of the marriage. Vivian traces the efforts of husband Leon to make and market an antidepressant. Leon’s love of flying during the war has translated into his urge to travel widely, especially on his luxurious yacht. But as the years pass, Vivian starts to record her worries, her dissatisfactions, and the temptation of taking a lover. Her musings are interrupted by remarks she finds in an untitled book by the Indian guru Kharjappalli. (Sample piece of wisdom: “God also doubts your existence.”) The couple’s lives form the outline of an Antonioni film.

Léon is making a record too. He’s wielding the Daddycam as he documents all those vacations and breakfasts and views of Manhattan, Hawaii, Las Vegas, and aqueducts. Vivian has misgivings (“If you film, you don’t have to live”) but learns to use the camera herself, and even steer the yacht.

Finally there is an exceptionally discreet effects track. The home-movie scenes are eerily silent because there’s no voice-over, but occasional noises are dubbed in, and very rarely there’s a snatch of music. On the whole, the absence of musical cues for emotion renders the pictures and the diary texts all the more powerful. (Compare the emotional tug of Jóhannsson’s score for Last and First Men, a film that also “overwrites” mysterious visuals with a text sourced to a woman.) The result is a dry, unsentimental treatment of a crumbling marriage in the midst of Europe’s postwar boom.

Out of 29 hours of found footage Nuria Giménez and her colleagues have fashioned a fascinating film that is at once pure documentary and creative fiction. I like to think of it as another way to assemble a narrative–at one level simple chronology of a cosmopolitan couple’s life, on another the hidden story of voyages to Italy and elsewhere. I kept seeing the ghosts of Bergman and Sanders in this couple on the modern Grand Tour.

I knew about none of these films before encountering them at VIFF, which is of course one reason we cherish this and all other festivals. Granted, there’s reassuring pleasure in seeing the latest accomplishments of established and esteemed old hands (here Ozon, Petzold, Vinterberg, Rasoulof et al.). Just as valuable, though, is the jolt of seeing newcomers present beguiling variants on familiar traditions. Three of these films, as far as I can tell, are first features, and they offer fresh takes on stories we thought we’d seen before.

All are graced with sharp cinematic intelligence and offer pointed commentary on lives lived now and back then, close to home or far away. All remind me of why this VIFF wing is called Panorama. Every movie widened my vision.

Thanks, as usual, to Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, Jane Harrison, Curtis Woloschuk, and their colleagues for their help during the festival. Thanks as well to programmer and consultant Shelly Kraicer for background on Memories to Choke On.

You can sample the films in their trailers: Tales of the Lockdown is here; Memories to Choke On is here; Sarita is here; and a particularly shrewd one for My Mexican Bretzel is here (incorporating, I think, footage not in the film). Giménez’s film won the Found Footage Award at Rotterdam. If you insist on knowing about how her film was made before seeing it, you can check this Film at Lincoln Center interview.

I hope other festivals, and streaming services, and even theatres will pick up all these films for wide distribution.

My Mexican Bretzel (2019).

Little stabs at happiness 5: How to have fun with simple equipment

Tiger on Beat (1988).

DB here:

Simple equipment includes, but is not limited to, knives, pistols, shotguns, ropes tied to shotguns, surfboards, chainsaws, etc.

Herewith another attempt to brighten your days with a choice film sequence that never fails to bring a foolish grin to my face. Apologies as ever to Ken Jacobs for my swiping his title.

Tiger on Beat (aka, but less pungently, Tiger on the Beat, 1988) is prime Hong Kong showboating. This final scene assembles some of the greats—Chow Yun-Fat, Gordon Liu Chia-Hui, Chu Siu-Tung (too little to do)–and near-greats like Conan Lee Yuen-Ba, who gets points for heedlessly executing the stunts Chow and Chow’s doubles can’t. Lau Kar-Leung (aka Liu Chia-Liang), one of Hong Kong’s finest directors, imbues both the staging and the editing with the crisp, staccato rhythm that this tradition made its own, and that few American directors have ever figured out. (It’s a long clip, so it may take a little time to load. In addition, our Kaltura operation is having problems, so you may want to try different browsers.)

Come to think of it, this little-stabs entry contains some fairly big stabs of its own.

The whole film is worth a look. Opening scenes feature Chow in outrageous threads, the very opposite of a cop in plainclothes, and there’s a fine car chase in which many risk life and limb. But this sequence, lit high-key so that every splash of saturated color pops, is for me the highlight, a tour de force of action cinema. Probably not for the kids, but what do I know about kids?

Sequences like this were what drove me to teach Hong Kong film and write Planet Hong Kong. They also impelled Stefan Hammond and Mike Wilkins to write Sex and Zen and a Bullet in the Head (1996), the most deeply knowledgeable fanguide to this glorious cinema. Stefan followed it up with Hollywood East: Hong Kong Movies and the People Who Made Them (2000). Now Stefan and Mike have effected a merger of these and updated and expanded them. They’ve also recruited a band of other Guardians of the Shaolin Temple: Wade Major, Michael Bliss, Jeremy Hansen, Jude Poyer, David Chute, Dave Kehr, Andy Klein, Adam Knee, Jim Morton, and Karen Tarapata.

The result is another indispensable volume, More Sex, Better Zen, Faster Bullets: The Encyclopedia of Hong Kong Film. The recommendations are sound, the plot synopses are nearly as much fun as the movies, and the authors have wisely retained chapter titles like “So. You think your kung fu’s. . . pretty good. But still. You’re going to die today. Ah ha ha ha. Ah ha ha ha ha ha.”

They weigh in on today’s sequence: “This gory Armageddon-duet consistently scores on Top Ten End-Battle Lists among HK film aficionados.” Makes me even more confident to recommend it to you. They add that the credits music is “a hard-rocking theme song by HK power diva Maria Cordero.” So I let it run.

I analyze this and other action sequences in this blog entry. An appreciation of Lau Kar-Leung is here.

For more little stabs, check out earlier entries in this series.

Chow Yun-Fat gets his daily dose of egg yolks (Tiger on Beat).