Archive for the 'National cinemas: Hong Kong' Category

Sometimes a jump cut…

A Touch of Zen (King Hu, 1970).

DB here:

….really is a jump cut.

I had spent a day studying King Hu’s The Valiant Ones at an archive. That night over dinner, my friend asked me what was taking me so long. I answered, “I’m trying to figure out his secrets.” Her brow furrowed, but then she said, “I suppose that’s all right as long as you never tell anyone.”

Reader, I told. Eventually.

The puzzle for me was how King Hu gets the remarkable kinetic effects in his fight scenes. He starts with the conventions of the Chinese wuxia (“martial chivalry”) film. Fighting with or without weapons, the warriors have extraordinary powers of speed and strength. They can sometimes defy gravity with “weightless leaps” that carry them great distances.

Today, digital special effects permit quite dazzling images showing flying warriors in extended long shots, as in Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon and Hero. But Hong Kong directors of the 1960s and 1970s had much more meager special effects available.

The alternative was to present these feats through constructive editing. A character leaps in shot A, flies through the air in shot B, and lands in shot C. All much easier to film than a single, faked long shot. From the 1980s on, strong but thin wires would keep the fighters in the air for long shots. Many fine films were made using wirework, but for the most part King Hu couldn’t use it. About his only technological support was a variety of trampolines that could be cunningly hidden in a set.

King Hu’s solution to the problem of flying swordfighters involves a unique approach to film technique. In an article called “Richness through Imperfection: King Hu and the Glimpse,” I argued that he found a way to make his fighters’ prodigious moves register in a percussive but almost subliminal way. It’s not just that if you blink, you miss the action. (Though if you do, you will.) His goal isn’t just to use brief shots (some only three or four frames long) to arrest our attention. More important, King Hu evokes the quasi-supernatural power of his fighters by suggesting that they move too quickly and unpredictably for the camera to catch.

He accomplishes this by reshaping the constructive-editing scheme of launch/leap/landing. He trims each shot to a minimum, provides several intermediate flying shots (each also very short), and makes our eye work by shifting the center of interest from shot to shot. He provides eccentric angles, unexpected cuts, and startlingly empty frames. Characters run, spring up, and soar, but in a flurry of frames, or on the screen edge, or dodging in and out of sight–blocked by bits of the set, or just by a framing that doesn’t adjust quickly enough to their impulsive movements.

A good example is the moment in Dragon Gate Inn (1967) when the eunuch Tsao attacks the group defending the family of General Yu on the roadway. A low angle shows him launching his jump.

So far, so conventional. But instead of giving us a clear image of Tsao in flight mode, Hu gives us this:

Tsao slides down the left frame edge, vanishes for an instant, then bounces up, already somersaulting, on his way to strike his adversary Hsiao. The framing fails to keep up with him, implying that he’s just too elusive, while his wayward entries into the frame provide percussive accents.

King Hu liked to play with the leap phase of the ABC pattern, as here and in my knockout passage for the day, shown at the top of the entry. In the penultimate confrontation of A Touch of Zen, Commander Hsu attacks the serene Abbot Hui Yan. Hsu leaps a huge distance and comes down directly in front of the monk. But King Hu renders this miraculous feat in two nearly identical framings: one showing the launch, the other the landing. Seen from over the monk’s shoulder, Hsu has been endowed with blinding speed through a sheerly cinematic effect–a bold jump cut.

Please note: This isn’t a clumsy patch job in the particular print. The cut is in the negative, and it’s been in every print I’ve ever seen of Touch of Zen.

“Jump cut” is a term that’s used in different ways. Sometimes it refers to various kinds of mismatches that yield a jolting discontinuity. I’m using the term here to denote an effect that results from excising some frames from a continuous shot. The classic examples have always been the cuts in Godard’s Breathless. The Touch of Zen example is a little less pure because you can see that Shot 2 doesn’t strictly continue Shot 1’s camera setup. King Hu has moved the abbot’s head and shoulder a little further away from us. But the compositions are graphically very close, and the impression on screen is of a single camera take with some frames lopped out.

When we ask, Where did Hsu go from shot to shot?, the answer is: In the cut. Without the advantage of special effects, King Hu has given us a propulsive impression of speed and ferocity.

His secret? Merely a uniquely cinematic imagination.

Some of our techie readers might be curious about the images here, photographed from a 35mm print. Perhaps they’ve noticed that Hu’s cutting has left its physical trace on the film strip.

In classic filmmaking practice, cuts were made with splices–physical joins between one piece of film and another. In film-based formats, splices were made with glue or transparent tape. (Today, of course, they’re largely made digitally and called “edits.”) Most filmmakers hid their splices, but there’s a robust tradition in avant-garde cinema of integrating splices into the image; you can see it, for example, in the work of Stan Brakhage and Paolo Gioli.

Splices are visible as horizontal flashes across the bottom of the screen. In 35mm filmmaking, the final printing phase usually masks those out. But, as Erik Gunneson reminds me, that’s harder when you’re shooting anamorphic scope. There the image is recorded full-frame on the film strip, so traces of the splice may remain visible, especially in older films.

When we look at the physical strip here,we can see that Hu’s negative cutter has simply spliced one shot to another with cement. The illustrations up top show the last frame of Shot A and the first frame of Shot B. You can see the neat splice, a horizontal line running along the bottom of the first frame and the top of the second. The same trace of a splice is visible in the cut involving Yang’s leap.

The odd thing to modern eyes is that there’s a bit of overlap, a thin slice that seems out of whack with both shots. In Shot A, the bottom edge of this thin strip cuts off the abbot’s head weirdly. Let me show you the first frame of the second shot again. Reading from top to bottom, you see a bit of the bottom of Shot A’s last frame, then the true frame line, then the weird little band. The bulk of the image is the frame that starts Shot B.

What’s that thin slice between the frame line and the yellow splice line? It’s the top bit of the next frame of the first shot as taken in camera. It shows the trees and the abbot’s head and ears as they appear at the top of Shot A’s composition. Instead of cutting exactly on the frame line of Shot A, the editor has overlapped a tad of the following frame in order to attach the two shots with cement. During a screening, the extra bit may be minimized or eliminated because the projector plate doesn’t show us the entirety of the image on the strip, but it is there.

Splices can be hidden through A/B rolling, which I believe is more common in 16mm than in 35mm production. I don’t believe that Chinese films of Hu’s day made use of this process, but I’d appreciate more information.

The essay on King Hu is in my Poetics of Cinema (Routledge, 2008), 413-430. For more on King Hu and his innovations, see Planet Hong Kong: Popular Cinema and the Art of Entertainment, available elsewhere on this site. Kristin and I discuss jump cuts and graphic matches in Chapter 6 of Film Art: An Introduction. See also the “Film Technique: Editing” category on the right of this page.

This blog entry follows from two others: “Sometimes a shot . . .” and “Sometimes two shots . . .”

I put up this post now because I’ll be giving a talk on Chinese martial arts cinema next Monday, 10 June at the Toronto International Film Festival Bell Lightbox, at 6:30. It’s a part of TIFF’s splendid summer-long celebration of Chinese cinema. On the day before, 9 June, there will be a free screening of Hou Hsiao-Hsien’s Dust in the Wind (1987) at 10:00 AM. After the show, there’ll be a panel featuring Bart Testa, Hou expert Jim Udden (who posted a blog entry with us on Hou’s new project), and me.

This entry is also to congratulate Peter Rist, tireless guardian of the Shaolin Temple, on his birthday.

A Touch of Zen.

TIFF: More than movies

Audiences gather for screenings at the Bell Lightbox, hub of the Toronto International Film Festival.

DB here:

Around midnight tonight, the crowds packing the Toronto International Film Festival will disperse, leaving the city full of memories of another extraordinary year. I’ve been back in Madison for this last week, but my few days at TIFF remain on my mind. This is partly because along with the films came a lot of ideas, opinions, and information. At any festival, fraternizing with audiences, critics, and programmers is one fine way to get that stimulation. It happened after some of the Wavelengths section’s short-film programs. Here are Raymond Phatanavirangoon and Bob Koehler outside the Art Gallery of Toronto, where their Devo retro-stylings raised our conversation to a new level.

More structured sessions delivered too. Out of my 4-plus days at the Toronto International Film Festival, I set aside about one and a half for industry panels and filmmaker Q & A’s. Let me tell you a little of what I learned.

From Assayas to Asia

TIFF: Where programmers meet stardom.

The talkfests I attended shed light on both film artistry and film business-making. Central to the first area was the master class with Olivier Assayas, hosted by Brad Deane.

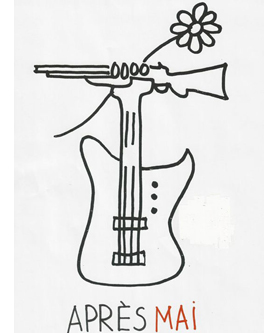

Assayas, a charming fellow, talked fluently about how Something in the Air (discussed here) bears traces of his youth. During the 1970s, high-school kids were “footsoldiers of the cultural war of the time.” He recalled his affinities with the artistic side of the counterculture, as opposed to the extremes of the political activists, some of whom, being aligned with Maoism, refused to recognize the Cultural Revolution as “disaster on a demented level.” Yet this shouldn’t be taken as apolitical aestheticism; Assayas has been a vigorous advocate for the work of Situationist Guy Debord.

Assayas was refreshingly detailed about his working methods. He writes only one draft of his screenplay, partly because he wants to protect the “digressive” aspects of his story. (This tendency is apparent, and enjoyable, in Something in the Air.) Since his films are difficult to classify within standard genres, he needs to cobble together creative financing for each project. But the script becomes obsolete when he casts the film and visits locations. By embodying the characters, the actors create beings “more powerful than what I’ve written.” Working with them, he refuses to supply background on the characters’ psychology. “I look to them to understand the characters.” This hands-off approach yields striking results in the new film, where nearly all the cast is non-professional.

Assayas was refreshingly detailed about his working methods. He writes only one draft of his screenplay, partly because he wants to protect the “digressive” aspects of his story. (This tendency is apparent, and enjoyable, in Something in the Air.) Since his films are difficult to classify within standard genres, he needs to cobble together creative financing for each project. But the script becomes obsolete when he casts the film and visits locations. By embodying the characters, the actors create beings “more powerful than what I’ve written.” Working with them, he refuses to supply background on the characters’ psychology. “I look to them to understand the characters.” This hands-off approach yields striking results in the new film, where nearly all the cast is non-professional.

Assayas doesn’t undertake elaborate rehearsals, instead coming to the set each morning and describing the shots they’ll make. He wants to take account of the evolution of the film as it’s been developing. He doesn’t fully block the shots. He sketches each one in longish takes that, as the actors expand on the action, “add layers” to what he’d initially planned. Alternatively, he cuts up the long takes and combines pieces of them. For Something in the Air, he relied on stable and wide framings, partly in reaction to trends toward handheld shots and close-ups, partly because he used the crane to create a “floating,” more lyrical circulation through the space.

Artistry, mixed with business sense, was apparent in one of the panels at the Asian Film Summit’s day of meetings. Colin Geddes hosted a session on Asian genre cinema, and several producers and directors shared thoughts on action cinema as an international genre. Fanboy blood pulsed high.

Artistry, mixed with business sense, was apparent in one of the panels at the Asian Film Summit’s day of meetings. Colin Geddes hosted a session on Asian genre cinema, and several producers and directors shared thoughts on action cinema as an international genre. Fanboy blood pulsed high.

Eli Roth (left), another kid who grew up with Kung-Fu Theatre on TV, was bowled over years later by Korean and Japanese thrillers like Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance. Now Roth is producer and co-writer of The Man with the Iron Fist, directed by RZA–who is, according to Roth, letter-perfect on his kung-fu film knowledge. “We wanted to do a movie like we saw as kids on Saturday afternoon.” But production values in the genre have swollen since the old days. The project is using the Hengtian studio’s vast replica of the Forbidden City. RZA, Roth says, expected The Last Emperor to be a kung-fu movie, so this is his attempt to make things right.

Tom Quinn, Co-President of the Weinstein Company’s RADiUS division, had similar affinities. As he pointed out, East Asian countries have strong local markets and so can build a base in genre cinema. With quantity comes quality. While working at Goldwyn and Magnolia, Quinn handled US distribution for The Host, Pulse, Tears of the Black Tiger, and most recently 13 Assassins, along with many other titles. Ong-Bak, on view at TIFF in 2004, was a particular triumph for him, yielding over a million dollars in its first weekend of release and eventually garnering $4.5 million in the US. Even the heavy piracy of Ong-Bak Quinn takes as a positive sign, “a validation of the film’s value.”

Bill Kong, a legendary Hong Kong producer and a force behind Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, along with Stephen Fung, director of Tai Chi 0 (above), filled out the panel. Overall, the discussion ranged widely, but one question kept cropping up. Why is it that Western films are widely popular in Asia, but Asian cinema is almost completely a niche market in the West? I didn’t hear a clear answer (though I’d start an answer with Western racial prejudice).

Kong noted that Asian filmmakers don’t have high expectations about penetrating the US market, but other panelists were more hopeful about crossover projects. Quinn pointed out that the festival circuit built an audience, and Roth thinks that Tarantino has been a major player in making Asian film more popular, especially with the Kill Bill duet. The fact that Russell Crowe plays a major part in The Man with the Iron Fist suggests that things may be changing.

Bigger than Bollywood

Mira Nair.

The East/West dynamic was also the focus of two other panels. “India: Lessons from Bollywood and the Independents” brought together a nearly all-female group of experts to discuss local financing and wider distribution. All were agreed that it was necessary to convince the world that Indian cinema was bigger than Bollywood. As director Dibakar Banarjee put it: “We need to open the third eye.”

The local industry has a certain comfortable inertia. A film might cost only $150,000, but it can collect 90% of its production costs upon its opening run, said Shailja Gupta, who has been both a director and production executive. Foreign distribution is a major risk at this budget level. So how does a project, particularly an independent film, get international traction?

Coproductions are an obvious path, and while they are still rare, the trend is emerging. The Indian government’s National Film Development Corporation Ltd. has helped with coproductions since 2006, says Nina Lath Gupta, NDFC Managing Director. Such enterprises are rare and mostly involve France or Germany. By establishing the Film Bazaar in 2007, the NDFC acknowledged the importance of marketing as well as financing, and this is getting local filmmakers acquainted with the need to think more globally.

Another path to the overseas market was suggested by Guneet Monga (right). She is a producer on the network narrative Peddlers and the two-part gangster saga Gangs of Wasseypur; both earned very good buzz at TIFF. Monga pointed out that sales agents can help shape projects for international distribution.Working with Elle Driver, she was able to generate three versions of Gangs, targeted for different regions. Moreover, sales agents can help a film by avoiding the old practice of selling it as a single package. Instead, the agent can pre-sell it with a minimum guarantee and negotiate territorial rights further down the line.

Another path to the overseas market was suggested by Guneet Monga (right). She is a producer on the network narrative Peddlers and the two-part gangster saga Gangs of Wasseypur; both earned very good buzz at TIFF. Monga pointed out that sales agents can help shape projects for international distribution.Working with Elle Driver, she was able to generate three versions of Gangs, targeted for different regions. Moreover, sales agents can help a film by avoiding the old practice of selling it as a single package. Instead, the agent can pre-sell it with a minimum guarantee and negotiate territorial rights further down the line.

Mira Nair, distinguished director of Salaam Bombay and Monsoon Wedding, has long enjoyed worldwide exposure, of course. She shared her thoughts on how filmmakers could follow their visions and still, as she put it, “put bums on seats.” That’s accomplished by not worrying about distribution but devoting energies to creative choices–such as she undertook in The Reluctant Fundamentalist, her first foray into the thriller genre.

During the India panel, moderator Meenakshi Shedde asked if China might become a coproduction partner for local films. This is currently not happening, but the question reflects the significance of the People’s Republic on the global film scene. Earlier in the day, a panel on “Financing Between Asia and the West,” moderated by Patrick Frater, concentrated mostly on China as the leading edge of the region. Once more, the question of coproductions was central.

“Coproduction is a reality now for global filmmaking,” declared Peter Shiao, CEO of Orb Media Group. But the power of China in the new media landscape has created a false optimism among Western entrepreneurs. Shiao warned newcomers that coproductions can’t be fulfilled in good faith with perfunctory gestures, such as including a Chinese actor in a secondary role. (The Expendables 2 was mentioned in this connection.) Aspiring filmmakers need to grasp and follow the China Coproduction Film Office regulations straightforwardly.

Solid coproductions are rare, agreed Bruno Wu, founder and chair of many top Chinese media groups. He pointed out that what works in China won’t necessarily work in the rest of the world, but what works in the rest of the world is likely to work in China. So the Chinese investor needs to look at projects that will play internationally. He gave as examples his firms’ deals with Justin Lin and John Woo, who have reliably won global audiences. Along similar lines, Stuart Ford, founder and CEO of IM Global, suggested that a good alternative to coproduction involves soliciting equity investment from China for Western films. For example, Chinese investors in Paranoia, a $40 million production, acquired mainland distribution rights as part of the deal.

The soundness of investing in Western films seems borne out by local box-office figures. Seventy percent of China’s market receipts come from English-language imports; the several hundred domestic films produced earn only twenty percent. And theatrical receipts provide, according to Peter Shiao, ninety percent of a film’s earnings. Windows in the Western sense don’t exist, and there’s no legitimate home video market. Gradually local filmmakers are experimenting with Western ancillary tactics; Painted Skin: The Resurrection recently tried out apps and games.

China-based Video on Demand is more promising. In a few years, Wu expects there to be several million addressable HD cable homes, and providing entertainment on demand might provide a way around the national quota system for film import. There is no quota restraining VOD distribution, and as it takes hold, it might reduce piracy.

A killer app? (as in killing off business?)

Jonathan Sehring and Winnie Lau at the VOD panel at TIFF, 9 September 2012.

Speaking of VOD, in early September I signed up. I did it partly because there was one title I needed to see immediately: Keanu Reeves’ Side by Side, the documentary about the digital vs. film controversy. More abstractly, I had been learning a little about VOD when I recast and expanded my blogs on digital exhibition for Pandora’s Digital Box, and I was curious about how VOD worked in practice.

After a period of turmoil, the US film industry has integrated VOD into its system of non-theatrical ancillaries. Before, we had DVD and Blu-ray, both rental and retail, along with movie channels like HBO and Sundance available on subscription cable. Eventually movies would show up on basic-cable channels. There was also “pay per view” via cable, a one-off transaction now known as Pay TV VOD.

Now, the internet has expanded the options.

*Electronic Sell-Through (EST) allows the consumer to download a film and own it. This service is available through iTunes, Amazon, and other outlets.

*iVOD (internet VOD) is a one-off rental, to be run immediately or within a specified time period. To check the 1.77 aspect ratio on Dial M for Murder, I rented it for 24 hours on iTunes.

*Subscription VOD (SVOD), which you get with Netflix, Hulu, Amazon, and other providers. This option provides a library of titles available at any time for a monthly fee. SVOD is comparable to cable-television subscriptions, and it’s becoming very popular, as all-you-can-eat options tend to be.

In addition, another option hovers over the business:

*Premium VOD (PVOD) consists of a one-off rental available sooner than the traditional home-video window. The transmission would be via cable or satellite, not the Net, and the price point has typically been $30 for one viewing. The studios tried out PVOD with DirecTV in 2011, with apparently unencouraging results. Worse, last year’s Tower Heist fracas, during which Universal planned to put the film on PVOD 30 days after theatrical release, triggered threats of boycotts from exhibitors. PVOD, however, is likely to reappear at some point because it can offset losses from the declining DVD market.

No surprise, then, that one industry panel was called “VOD Killed the DVD Star.” The session assembled major players in that domain to discuss the present situation and the prospects for the future.

Much of the panel’s time was devoted to explaining why filmmakers needed to be flexible about accepting VOD as a legitimate complement to or substitute for theatrical release. VOD, they insisted, shouldn’t be seen as a dumping ground for weak or narrow-interest films. The reason: The consumer is king, and consumers want everything on demand.

Winnie Lau, Executive Vice-President for Sales and Acquisitions at Fortissimo, said that companies now recognized that consumers should be able to see a film on whatever platform they want. Given the high costs of a theatrical release, that option isn’t justifiable for many films. Philip Knatchbull, CEO of Curzon Artificial Eye, put the case more strongly, declaring that with the consumer in control, notions like windows and “on demand” are losing their usefulness. His view suits a company that, like IFC, has integrated video and theatrical distribution with theatre ownership and HD delivery. There are, he suggested, only home cinema and public cinema, and everyone in the film value chain should be aiming to reach millions of screens.

Tom Quinn of RADiUS was working for Magnolia when in 2005 Mark Cuban experimented with a multiple-platform release of Bubble. “His vision,” Quinn recalled, “was to make films available whenever people liked.” The Bubble experiment was problematic because it came out on film and on DVD simultaneously, but Quinn said that “the hotel VOD numbers were through the roof.” This summer, after twelve months of preparation, RADiUS has issued its first VOD titles, and Bachelorette, released earlier in September, won notice for earning about half a million dollars in its first weekend.

The prototype of longer-term VOD success is the later career of Edward Burns. Burns, who had his first success with the breakout indie movie The Brothers McMullen (1995), was lively and articulate. “VOD helped me stay in business.” He knew firsthand the slow rollout that characterized 35mm platform release in the 1990s, along with the months of press tours. In the years that followed, he realized that his movies–basically, as he put it, people bullshitting with one another around a kitchen table–had shrinking theatrical prospects. In 2007, he offered Purple Violets exclusively on iTunes. This came around the time that IFC and Magnolia were experimenting with day-and-date releasing on different platforms.

The prototype of longer-term VOD success is the later career of Edward Burns. Burns, who had his first success with the breakout indie movie The Brothers McMullen (1995), was lively and articulate. “VOD helped me stay in business.” He knew firsthand the slow rollout that characterized 35mm platform release in the 1990s, along with the months of press tours. In the years that followed, he realized that his movies–basically, as he put it, people bullshitting with one another around a kitchen table–had shrinking theatrical prospects. In 2007, he offered Purple Violets exclusively on iTunes. This came around the time that IFC and Magnolia were experimenting with day-and-date releasing on different platforms.

Burns was satisfied with the results and built a production model around VOD. The cast and crew work for free and collectively own the film. Budgets can be low; he claimed last year that Newlyweds cost only $100,000. Payments are deferred, and if a film breaks through, everyone makes money. His last three films, he reported, did. He compared the business model to that of an indie band. VOD gets his work to the people who watch HBO, Showtime, AMC. “That’s our audience.”

Burns is an unusual instance, since as one panelist pointed out, he has established his own brand. Still, other VOD releases can break out. The most widely publicized example is Margin Call, with about $4.5 million on VOD. Jonathan Sehring, President of IFC and Sundance Selects, was a pioneer of alternative platforms, and he remarked that 4 Months, 3 Weeks, and 2 Days did better on VOD than in theatrical release (where it grossed $1.2 million). In a recent interview, Sehring indicates that the recent IFC release About Cherry as doing as well as Bachelorette on VOD and other revenue streams.

It seems, then, that these and other industry decision-makers see VOD as offering two avenues, depending on the film. VOD can provide a new window, to be added before or after or during theatrical release. Alternatively, VOD can replace theatrical, as it has done for Burns (who will still occasionally give a film like the upcoming Fitzgerald Family Christmas brief theatrical play). With this option, many films, both domestic and imported, will never see a theatrical release but they might make money on the less costly VOD platform.

The problem for the second strategy is finding a way to make the film stand out from the thousands of titles available in cable and VOD libraries. A theatrical release provides the “shop window,” as Knatchbull called it, but without that, the film needs other salient features–big stars or cult buzz–to attract the home viewer.

Despite the panel’s title, the guests didn’t predict that VOD would displace discs. In fact a couple of panelists agreed that DVD and Blu-ray would be around quite a while. Quinn (left) confessed that as someone who grew up with VHS he would always be collecting his favorite films on physical media.

There’s something else to consider: some dramatic disparities between VOD and DVD consumption. The differences are spelled out in a recent IHS Screen Digest report.

On one hand, the VOD audience has grown rapidly. The report counted transactions–buying a movie in any form–and came up with striking figures for the world’s top five regions.

2007: DVD retail and rental: 2.7 billion transactions; online VOD in all forms: 14.8 million transactions.

2011: DVD retail and rental: 2.58 billion transactions; online VOD in all forms: 1.4 billion transactions (nearly all SVOD).

The Screen Digest team estimates that 2012 will see an even bigger burst in online VOD, totaling 3.4 billion transactions, with nearly all that via subscription. (I’m in there somewhere.) By contrast, physical media sales and rentals are predicted to fall further, to 2.4 billion transactions.

The disparity lies in “monetization.” We have some access to weekend box office grosses, but almost none to income from DVD and VOD, so comparison is difficult. Still, everyone knows that DVD purchase and rental, along with pay TV licensing, yield the bulk of film revenues. In another research report, Screen Digest estimates that in the US the 2012 surge in VOD will yield only $1.72 billion. DVD will yield $11.1 billion, nearly ten times the VOD transactions. Even with the declining retail and rental prices of discs, VOD yields much less per transaction than DVD does, especially with subscription services leveling out the cost to consumers.

So did VOD kill, or at least wound, the DVD star? When measured in transactions, yes. In revenues, no. Moguls pay off their Ferraris in dollars, not transactions, so it seems that VOD would have to expand colossally, or raise prices, or both, to come close to achieving the returns of DVD.

It’s conceivable that VOD will cannibalize other windows, if you’ll excuse the mixed metaphor. DVD transactions were going downhill before the rise of VOD, but perhaps VOD will accelerate that plunge. iTunes already charges up to $20 for EST downloads of a new release. As consumers become used to storing their movie and TV collections digitally, the convenience of EST could hurt DVD sales.

Moreover, VOD has always threatened the theatrical market. That’s why exhibitors cried foul when Premium VOD was tried. But box-office grosses overall remain robust because ticket prices are constantly rising and 3D and Imax rely on upcharges. These revenues offer studios a good reason to maintain strict windows, at least for their most successful releases. Still, studios are very likely to continue to press for PVOD. And indie distributors have embraced VOD release exuberantly. Foreign and indie titles released on VOD before or during the theatrical run may steal business from art houses.

In sum, VOD might shake up the other platforms quite a bit. If your analogy is the music business, theatrical and DVD formats stand in for albums, while VOD is the online force that lowers consumers’ sense of a fair price point. There’s some discussion of raising prices for some iVOD and Pay TV VOD offerings to parity with theatrical ticket prices. I wonder if consumers will sit still for that. As a novice VOD’er who likes going out to see movies big, I probably wouldn’t. Unless Hulu’s Criterion library discovered a lost Mizoguchi.

Assayas’ autobiography A Post-May Adolescence has just been published in English translation. It includes two essays on Debord. At the same time, an anthology of critical essays on Assayas, edited by Kent Jones, has appeared in the sterling Austrian Film Museum series.

Patrick Frater reports on the TIFF Asian Film Summit at Film Business Asia.

My statistics on the progress of VOD come from “Movie Consumption Stabilizes,” IHS Screen Digest (April 2012): 95-98, and “Online Movie Consumption in the US,” IHS Screen Digest (May 2012): 116. See also Andrew Wallenstein’s Variety story, where we learn that Netflix’s subscription model is beating the pants off the competition. Thanks to David Hancock of IHS Screen Digest for further information.

As before, thanks to my Toronto hosts Cameron Bailey, Brad Deane, Christoph Straub, Andrew McIntosh, Andrea Picard, and all their colleagues.

TIFF leaves an indelible mark: The ankle of Crystal Decker, Marketing Manager of Well Go USA Entertainment, US distributor of Tai Chi 0.

P.S. 17 September: Thanks to Anuj Mehta for correction of a misspelled name.

ADD = Analog, digital, dreaming

Luther Price, Sorry Horns (handmade glass slide, 2012).

DB here, just back from the Toronto International Film Festival:

It’s commonly said that any substantial-sized film festival is really many festivals. Each viewer carves her way through a large mass of movies, and often no two viewers see any of the same films. But things scale up dramatically when you get to the big boys: Berlin, Cannes, Venice, and Toronto. I’ve never been to the first three, but my first visit to TIFF was like wading into pounding surf and letting the current carry me off.

This is the combinatorial explosion of film festivals: A hefty 450-page catalog listing over 300 films from 60 countries. Moreover, because it’s both an audience festival and an industry festival where movies are bought, sold, and launched, you observe a range of viewing strategies. Although I sit too close to be much bothered, my friends tell me of mavens darting in and out of shows or checking their cellphones during slow stretches of what’s onscreen. The crowds add to the air of electric excitement, as of course do the visits of glamorous celebs.

So I was inundated. How to choose what to see in 3 ½ days for viewing? (I reserved time for industry panels.) I knew that some of the prime titles, such as Kiarostami’s Like Someone in Love or the remarkable-looking Leviathan, would be available for Kristin and me at Vancouver later in the month. And I saw no reason to stand in queues for Looper, Argo, and other movies that I could see in empty Madison, Wisconsin multiplexes during off-peak hours.

I still missed many, many things I wanted to catch. For much wider assessment of major movies, you should go to the coverage offered by the tireless scouts of Cinema Scope and the no less tireless scouts of MUBI. Here I’ll talk just about a few films that made me think about—no surprise—digital vs. analog moviemaking.

Fragments and figments

Mekong Hotel.

Stephen Tung Wai’s Tai Chi 0 (0 as in zero) represents everything we think of when we say that digital production and postproduction have transformed cinema. This kung-fu fantasy from the Chinese mainland (but using Hong Kong talent, including the director) retrofits the genre for the video-game generation. CGI rules. The result is, predictably, monstrous fantasy—a globular iron behemoth, a sort of Steampunk locomotive version of the Death Star—but also screens within screens, GPS swoops, tagged images, Pop-Up bubbles identifying the cast, and other scribbling that turns the movie screen into a multi-windowed computer monitor. One more thing Scott Pilgrim must answer for.

Jang Sun-woo played with similar possibilities in his 2002 Resurrection of the Little Match Girl, inserting character dossiers and creating digital effects mimicking gamescapes. But he sometimes paused to give these images a dreamlike langor. Tai Chi 0 never lingers on anything and instead carries the level of busyness to crazier heights. In a panel at the Asian Film Summit, Fung explained that one scene of the film was inspired by a particular online game. Sammo Hung was playing Fruit Ninja or something similar and Fung decided to include a scene of villagers turning away invading soldiers with a barrage of produce.

Fung said as well that fantasy martial arts remains a blockbuster genre in the PRC (viz. the success of Painted Skin: The Resurrection). Tai Chi 0 ends on a cliff-hanger, the end titles (rolled too fast to read) provide a trailer for part 2, and apparently a third part is in the works. Now China has franchise fever.

The stop-and-start plot is familiar from Hong Kong films of the 70s onward (including over-made-up gwailo villains), but its execution wrecks nearly everything I like about classic kung-fu movies. Clearly though, I’m not in the audience the movie is aimed at. My friend Li Cheuk-to, artistic director of the Hong Kong International Festival, opined that this digital froth could be very appealing to China’s online generation.

Tai Chi 0 exemplifies what academics writing on digital have talked about as the “loss of the real.” As Tom Gunning pointed out back in 2004, though, things aren’t so simple. Digital photography, after all, remains photography. The lens intercepts a sheaf of light rays and fastens their array on a medium. The fact that a shot can be reworked in postproduction doesn’t mean that every digital image must surrender the tangible things of this world.

At TIFF, the power of digital cinema to bear witness was on display in Sion Sono’s Land of Hope. Sono has already documented Japan’s 2011 earthquake and tsunami in Himizu, which I haven’t seen, but in that and Land of Hope, he abandons the wacko bad taste that made Love Exposure and Cold Fish so memorable. This is a sober, traditional drama presented with straightforward economy. It takes place in a fictitious district, Nagashima, but the fact that the name combines “Nagasaki” and “Hiroshima” suggests the gravity of Sono’s approach.

Three couples’ lives are torn apart by the quake, the tsunami, and the collapse of the nearby nuclear power plant. (All of these catastrophes are kept offscreen, glimpsed in TV reportage.) The oldest couple refuses to evacuate, clinging to their farm. Their son and his wife move to a nearby city where they succumb to the fear of radiation affecting their unborn child. And an unmarried couple wander the ruins looking for the girl’s father.

Sono intercuts the three lines of action. The old farmer adroitly manages his wife’s dementia and lets her indulge her fantasy of dancing in a village festival. In a critique of Japanese conformity, the young couple is shown being mocked for their worries about radiation poisoning. (The wife seals their apartment and, in a touch recalling the grotesque side of Sono, takes to wearing a Hazmat suit.) Less sharply developed are the fairly aimless ramblings of the youngest couple, though Sono injects some suspense when they dodge police blockades. At intervals, plaintive Mahler (a Sono weakness) surges up to underscore the futility of their search.

Throughout, government reassurances and the media’s insistence on putting on a happy face are treated with robust skepticism. Instead, Sono celebrates a dogged persistence to get through each day. The young couple’s mantra of “one step, one step” supplies the upbeat tone of the last scenes. As affecting as you’d expect is the footage of areas around the plant, seen as a wintry wasteland. Like Rossellini filming in bombed Berlin in Germany Year Zero, Sono has shot precious footage of ruins that testify to a calamity in which nature conspired with human blunders. And he did it digitally.

You can’t expect something so conventionally dramatic from Apichatpang Weerasethakul, and Mekong Hotel doesn’t supply it. It’s as relaxed as Tai Chi 0 is frenetic, and its central conceit makes it another pendant to Uncle Boonmee. The boy Tong and the girl Phon meet from time to time on the terrace of the hotel overlooking the river. They talk about folk traditions and the flood then besieging Thailand. They also encounter spirits that are as tangible, even mundane as they are; Phon’s dead mother appears in her room occasionally knitting. More shocking are the ghosts called Pobs who seem to possess the characters and make them hunch over and gobble intestines, sometimes in situations that suggest the organs have been torn from another character. All these scenes are handled with the usual Weerasethakul tact: long-take long shots, usually one per scene, that push the everyday and the extraordinary to the same unruffled level.

Mekong Hotel seems to operate on two planes of time. On the image track and in the dialogue, we witness Tong and Phon on the terrace or walking along the river. But the music, snatches of repetitive guitar tunes, seems to come from another time frame. At the start we see a guitarist practicing, and his noodlings run almost constantly under the drama we see. Another motif, fixed and lustrous shots of the Mekong River, yields a visual if not dramatic climax: a slowly paced choreography of Jet-skis crisscrossing the water. Here the digital medium may work to Weerasethakul’s advantage, with the clouds and landscape hanging unmoving over the racing watercraft, as a single, slow ship wades into the middle of their oscillating geometry.

The analog alternative

I suspect that Olivier Assayas filmed Something in the Air (originally Après Mai) on film, but even if he didn’t, the movie is a tribute to analog reproduction–mimeograph machines, LPs and turntables, and cinema in its different guises, from exploitation films to agitprop and experimental lyrics. We all know that the 1960s continued well into the 1970s, and here Assayas shows the uneasy carryover with a mixture of sympathy and critical detachment. The film starts with our high-school protagonist Gilles carving a peace symbol into his desk, flagrantly ignoring the teacher’s lecture. The shot encapsulates the film’s tension between political activism and image-making, and Gilles will oscillate between them in the course of the plot.

The poles come to be represented by two young women—the wealthy and ethereal Laure for whom he makes his paintings and the more hardheaded leftist rebel Christine, who goes out with him and others on nightly graffiti raids. When Laure leaves for London, Gilles continues his painting while leafleting and splashing slogans on walls, with the occasional Molotov cocktail to spice things up. The copains’ rebellion leads to some harm, but they cling to their ideals.

The poles come to be represented by two young women—the wealthy and ethereal Laure for whom he makes his paintings and the more hardheaded leftist rebel Christine, who goes out with him and others on nightly graffiti raids. When Laure leaves for London, Gilles continues his painting while leafleting and splashing slogans on walls, with the occasional Molotov cocktail to spice things up. The copains’ rebellion leads to some harm, but they cling to their ideals.

When summer comes, Gilles joins a film collective headed to document workers’ struggles in Italy. He encounters the arguments that made me smile in nostalgia: Shouldn’t revolutionary content have a revolutionary form? But how shall we reach the working class if our films are opaque? Assayas, who grew in this period and was repelled by the Maoist dogmatism of Cahiers du cinéma and Cinéthique, evokes these debates to remind us that the counterculture was about art and political change at one and the same time. Something in the Air chronicles a few years when imagination mattered.

After an early, shocking clash of students pounded down in a police riot, the film adopts a more circumspect rhythm, salting its scenes with books, magazines, record albums, and songs of the time. The plot keeps our interest by delaying exposition about the characters’ family lives until rather late. When we learn that Gilles’ father writes scripts for the celebrated Maigret TV series, we’re invited to see his forays into abstract painting as his form of teen rebellion. The plot doesn’t mind straying a bit from Gilles, as when his friend Alain, another aspiring artist, gets caught up in the fervor and pursues a wispy red-haired American dancer.

Characters meet, work or play together, drift apart, re-converge, and eventually settle into something like grown-up life. But at the end, when Gilles has apparently been absorbed into commercial filmmaking in London, he is granted one last vision of one of his Muses, who reaches out for him from the screen of the Electric Cinema.

Analog triumphs as well in The Master. Sitting in the front row of Screen 1 at the TIFF Lightbox (see below), I was astonished at the 70mm image before me. Not a scratch, not a speck of dust, not a streak of chemicals, and no grain. So did it have that cold, gleaming purity that digital is supposed to buy us? Not to my eye. The opening shot of a boat’s wake, which will pop up elsewhere in the movie, was of a sonorous blue and creamy white that seemed utterly filmic. Now we know the way to make movies look fabulous: Shoot them on 65.

The Master, as everybody now knows, centers on Freddie Quell, an explosive WWII vet, and his absoption into a spiritual cult run by the flamboyant Lancaster Dodd. Followers of The Cause are encouraged, through gentle but mind-numbingly repetitious exercises, to probe their minds and reveal their pasts. With the air of a charming rogue in the young Orson Welles mold, Dodd seems the soul of sympathy. But like Freddie he’s capable of bursts of rage, especially when his methods are questioned. Freddie becomes a sidekick because of Dodd’s fondness for his moonshine, while he also serves as a test case for the efficacity of The Cause’s “processing” therapies. If you can get this hard-bitten, borderline-sociopath in touch with his spiritual side, you can help, or fleece, anybody.

Like There Will Be Blood, this movie is primarily a character study. That film gained plot propulsion from Daniel Plainview’s oil projects, but many situations worked primarily to reveal facets of his dazzling self-presentation, his repertoire of strategies for dominating others. Something similar happens with Dodd and the ways he charms his congregation. But here the action is more episodic and the point-of-view attachment is dispersed across two characters. Dodd’s counterbalancing figure, the clenched Freddie, is so difficult to grasp psychologically (at least for me) that the film didn’t seem to build to the sort of dramatic, even grotesque peaks we find in other Anderson projects.

This is also a story about an institution, a quasi-church with a pecking order, rules, and roles. I wanted to know more about how The Cause worked, how it recruited people, and how it garnered money. Laura Dern plays a wealthy patron who lets the group stay in her home, and at one point Dodd is arrested for embezzling from the foundation, but the details of his crime aren’t explained. I also wanted to know more about the group’s doctrine, which seems so vague that Scientology need not worry about being targeted. The rapid-fire catechisms between Dodd and his acolytes are gripping enough, as Q & A dialogue usually is, but what system of beliefs lies behind them? The film seems to fall back on the familiar surrogate father/son dynamics at the center of most Anderson movies, but here filled in less concretely.

In short, after one screening I was left thinking the film was somewhat diffuse and flat. But I need to see it again. I thought better of Boogie Nights and Punch-Drunk Love after re-viewing them, so I look forward to trying to sync up with The Master on another occasion. Alas, in Madison, Wisconsin, I won’t have a 70mm image to entice me.

A bit of each, and both

Luther Price, No. 9 (handmade glass slide, 2012).

Analog imagery came into its own on other occasions, notably during the two programs of experimental films gathered under the heading “Wavelengths.” (At one I spotted Michael Snow in the audience.) Expertly curated by Andréa Picard, these programs assembled some strong, provocative films by several young filmmakers. I won’t review each one here–Michael Sicinski provides very useful commentary on nearly all those I saw—but I must mention the striking slide show that served as an overture one evening. The images didn’t move, exactly, but they might as well have.

Luther Price has been making remarkable films on 8mm and 16mm for several years, and one Wavelength program featured his Sorry Horns, a three-minute mix of abstraction and found footage. The same mix was evident in the procession of stunning handmade glass slides. Many, like the one surmounting today’s entry, evoke early cinema, decay, and clichéd Christian imagery: the wounds of film deterioration become cinema’s stigmata. Even the sprocket holes and soundtracks are invaded by festering particles. Arp-like blobs, pockmarked faces, and spliced and sliced movie frames lie under grids as irregular as medieval leaded windows. This is all gloriously analog.

No less captivating is the new, 100% digital work of an even older master of American avant-garde cinema. In one Wavelengths program Ernie Gehr offered us Departure (2012), a train trip playing on optical illusions in the spirit of Structural Film. We all know what it’s like to sit on a stationary train but then feel, when another train passes, as if we’ve started to move. Gehr translates this kinesthetic illusion into optical terms by filming, first upside down and then in judicious framings, several railbeds rushing by, faster and faster.

These layered ribbons sometimes unfurl right, sometimes left, and sometimes simply hover there as fixed, pulsating strips, all but losing the details of rail and tie and spike. Sometimes the one on top moves right, the grass verge beside it moves left, and the bottom track moves right (or left). This creation of flip-flop movement harks back to Side/Walk/Shuttle (1991) and to Gehr’s 1974 exercise in traffic abstraction Shift, which filmed patterns of commuter traffic from a very high angle.

Accompanying Departure was one of nineteen pieces in Gehr’s Auto-Collider series. Most of them contain some recognizable imagery, Gehr explains, but not number XV, the one we saw. In a sense the distilled essence of Departure, that film’s whooshing planes become vibrant, and vibrating, stacks of bold color, a bit like Daniel Buren in a joyous mood.

How did Gehr create the gorgeous Auto-Collider images? He declined to explain. Kristin suggested a plausible means to me, but I’m keeping quiet. In the analog age, when new methods of abstraction required a lot of sweat equity, filmmakers freely explained their painstaking work with lenses, light, and optical printers. But digital video practice flattens the learning curve. Powerful discoveries like Gehr’s or Phil Solomon’s are very easily replicated without much time, toil, or talent. Hell, somebody would make an app for them.

These artists are right to have trade secrets, just as magicians do. We should be satisfied merely to look. What we see reminds us that both analog and digital media harbor possibilities that go beyond the ability to replicate phenomenal reality. Both media can also dazzle us with things we’ve never seen, or imagined.

Digital projection seems to be taking over the festival scene, if TIFF is any indication. Cameron Bailey reports in a tweet that of the 362 films screened, 232 (64%) were in the Digital Cinema Package format and another 79 (21%) were in HDCam. The remainining 51 (15%) were in 16mm, 35mm, and 70mm.

Are the digital items still films? Robert Koehler suggested that maybe we will start calling everything movies. Interestingly, at the Wavelengths screenings, the artists called their artworks (whether on film or on digital video) “pieces.” Me, I still vote for calling films films, even if they’re on video, just as we have books in digital formats (such as, oh, I don’t know, this one). For me, at least these days, a film is a moving-image display big or small, whether it’s on film or some other medium. For some purposes we may want to specify further: Just as e-book and graphic novel indicate a platform or a publishing format, TV movie or video clip tells us more about what kind of film we have.

See also my January entry on festival problems with digital projection.

Thanks to Cameron Bailey, Andréa Picard, and their colleagues for enabling my visit to TIFF.

The industry screening of The Master at TIFF. Photo by M. Dargis.

Bon Cinéma! (miaou optional)

The Sorceror and the White Snake.

DB here:

For days, debates about the new Sight and Sound Poll have been saturating the Net ecosystem. The reach of the Web allowed editor Nick James to launch what may be a month-long striptease. (Well played, sir.) And likely you, reader, were weighing lists of masterworks.

But not me. I was watching Japanese space warriors blasting phosphorescent aliens to bits. I saw an amiable cannibal provide gory inspiration for a creatively blocked painter. I saw Dutch layabouts in mullets who made sponging off the system a death sport while calling each other “homo” and kut. I saw an ode to women’s armpit hair, moments of man-on-mule lust, and sexy female snake-demons writhing their way through two movies.

No candidates for the 2022 S & S poll here, but all in all, pretty diverting.

No hecklers, please

Montréal’s annual FanTasia is a three-week tribute to the world’s genre cinema. You get horror, SF, fantasy, martial arts, crime, and tasteless comedy. These movies are bloody, horrifying, outrageous, and hilarious. Nothing says entertainment quite like a wholesome family, complete with babe in arms, being plowed down by a delivery truck.

The name packs in a lot. I think it was first called FantAsia, as befit its early emphasis on Far Eastern imports, but the newer version shifts a little more emphasis to “fan,” which captures the tenor of the audience. Old folks worry that that the young avoid subtitled cinema. They should visit FanTasia, where teens and twentysomethings are happily watching movies from Iceland, Vietnam, Japan, Denmark, Hong Kong, South Korea, Thailand, and Holland. The brains behind this festival know what the kids want.

Don’t confuse this with Camp or Hecklevision. The multititudes come not to mock but admire. I suppose that’s partly because for decades smart genre pictures have woven moments of self-mockery into their texture, so as to mesh with that knowing, ironic attitude that characterizes our consumption of much popular culture. A closed loop: Genre connoisseurs make these movies, and other connoisseurs applaud them. Once you learn that Inglourious Basterds, Shaun of the Dead, Perfect Blue, Killer Joe, and Visitor Q have had premieres of one sort or another here, you get it: This is head-banging, but strictly quality head-banging.

The proof came with DJ XL5 Italian Zappin’ Party. This two-hour mélange of b-movie trailers and clips is a FanTasia tradition, having been preceded by Mexican and Bollywood editions. This year’s brew mixed snippets from fairly famous movies with glimpses of little-known items like Zorro contra Maciste, Spasmo, and The Three Fantastic Supermen. But the result isn’t exactly Camp, and it doesn’t attempt to mimic the media spew we see in Joe Dante’s Movie Orgy. Instead, typical trailers and scenes are tidily arranged in genres–peplum, spaghetti Westerns, giallo, and so on–and left to run at considerable length. Often the clips point up a recurring gesture or bit of iconography (decapitation, musclemen manhandling boulders). It’s less like zapping, more like an otaku assembling clips on a disc or in a file and inviting us over for an evening. Cheesy as many of these items are, we’re invited to appreciate the unpredictable energy of cinema that strives to shock.

The FanTasia tribe has its customs. At each screening, as the lights go down, you hear meowing, sometimes answered by barks or growls. One film started with bleating and clucking on the soundtrack, and this triggered a felicitous barnyard call-and-response; talk about surround sound. Nobody could explain to me the logic behind this FanTasia tradition–like streaking in the 70s, does it mean anything?–but its discreet silliness, perhaps distinctively Canadian, won me over. By the end I was joining in with a cracked miaou of my own. Yet once the movie starts, utter respect rules. Attentive silence is broken by appreciative laughter and whoops at those moments fans call OTT.

The festival’s ambitions are matched by the venues: raked Concordia University auditoriums with enormous screens and sound systems that envelop you. I sat in my favorite spot and didn’t regret it. Both film and digital projection looked sharp and bright. The staff get the audience in and out with dispatch, and everybody I met behaved with courtesy and good humor. Filmmaker Q & As are energetic and pointed. The movies are wild and sometimes abrasive, but the packaging is a model of civilized cine-festivity.

Never gonna grow up

You Are the Apple of My Eye.

The festival made its name with Asian popular cinema, and this year’s schedule didn’t disappoint. I could attend only the last week of screenings, so I missed some of the biggest titles, such as Peter Chan’s Wuxia, to be released in some markets as Dragon (innovative titling, eh? As we say in Canada.) But I did catch several entries.

You Are the Apple of My Eye, a Taiwanese rom-com, provides the now-standard mix of adolescent loutishness, romantic longing, and comic-book special effects. It starts with a twentysomething setting out for a wedding, and through flashbacks and voice-over, we learn of his high-school pranks and his surly affection for a charming girl in his class.

There’s always something touching about a gang of pals going their separate ways after school (viz., American Graffiti), so the film becomes more melancholy as the kids graduate and pass on to college and jobs; the only one who finds worldly success is a girl largely ignored by everyone. The plot shambles along, expecting us to be curious about whether the hero gets the girl he can’t quite learn to woo. The wedding culminates in a gag I found both clever and touching, a prolonged kiss–but not between the bride and our protagonist. And the motif of the ink-stained shirt, shown at beginning and end in a way that suggests a blue-bleeding heart, shows sophisticated sentiment.

School relationships are also character-defining in South Korean comedies, but their impact is more sub rosa in Love Fiction. Joo-wol is blocked after his first novel and is glumly working as a bartender. Attracted to a mysterious young woman, he pours all his literary talent into a Werther/ Cyrano effort to woo her. He even rhapsodizes about, and to, her armpit hair. Once they become a couple, however, he starts to write a murder thriller with her as a femme fatale. But his fiction leads him to investigate Hee-jin’s past, with disturbing results.

I thought this somewhat overlong movie tried to keep too many balls in the air–sequences dramatizing Joo-wol’s detective serial, flashbacks to his childhood, rumors about his girlfriend’s college sex life, and an excursion to Alaska. Again, though, it’s somewhat saved by a feel-good ending featuring Joo-wol’s friends in a scruffy band performing a karaoke video (above). As so often in the genre, stirring music redeems a meandering plot.

You Are the Apple and Love Fiction center on young men who grow up painfully, bruising others in the process, but Vulgaria keeps us firmly planted in adolescence. Pang Ho-cheung, who has done interesting work in You Shoot, I Shoot (a hitman hires a filmmaker to document his killings) and other projects, gives us what is being packaged as Hong Kong’s dirtiest comedy ever. Reliable sources report that no film has ever before contained such filthy Cantonese. It’s not quite as raunchy as it’s billed, though, and it has a predictably soft center.

You Are the Apple and Love Fiction center on young men who grow up painfully, bruising others in the process, but Vulgaria keeps us firmly planted in adolescence. Pang Ho-cheung, who has done interesting work in You Shoot, I Shoot (a hitman hires a filmmaker to document his killings) and other projects, gives us what is being packaged as Hong Kong’s dirtiest comedy ever. Reliable sources report that no film has ever before contained such filthy Cantonese. It’s not quite as raunchy as it’s billed, though, and it has a predictably soft center.

Chapman To plays a bottom-feeding movie producer who is drafted by a triad investor to make a sequel to the classic Confessions of a Concubine. The investor also insists on casting. He demands a part for the mule with which he seems to have an intensely physical relationship, and more centrally a role for Yum Yum Shaw, a decrepit beauty whom he remembers from the old days. Producer To agrees to all this while trying to keep the love of the daughter he shares with his divorced wife, and to continue a romance with a starlet with quality fellatio stylings. (Her secret weapon is Pop Rocks.) After an engaging setup, the plot gets thrown out of joint in typical Hong Kong fashion. To is knocked into a coma and recovers only to find the film finished and the patron displeased, not least because the director has redone the script with references to Al-Quaeda.

Not bad for a film shot in twelve days and made up as they went along. Still, I think that Pang made a capital mistake in not letting us see any of this bungled project. In particular, he set up the expectation that Yum Yum’s now sagging and plasticine face would be pasted on the starlet’s voluptuous body, and even cheap and clumsy CGI would have added to the fun. In any event, Vulgaria gets off some good-natured satire on the film industry in its financing crisis, and it provides many naughty laughs, not least in the sound effects that continue under the final credits.

Vulgarity was also the watchword in the Dutch comedy New Kids Turbo (2010). I was unaware of the TV comedy team New Kids, but their brand of politically incorrect slapstick is a little edgier than what we’d find in Hollywood. The aforementioned family-flattening gag and a passage in which policemen are amusingly shot probably wouldn’t make it past the producer notes in America.

Vulgarity was also the watchword in the Dutch comedy New Kids Turbo (2010). I was unaware of the TV comedy team New Kids, but their brand of politically incorrect slapstick is a little edgier than what we’d find in Hollywood. The aforementioned family-flattening gag and a passage in which policemen are amusingly shot probably wouldn’t make it past the producer notes in America.

Funny in small doses, this Five Stooges comedy of stupidity and aggression seemed to me to grow thin as it tried for more scale: the posse of dumb spongers refusing to pay for anything purportedly sets a model for the rest of Holland and calls forth repression from the authorities. I did learn that the planimetric framing on display in Napoleon Dynamite and Wes Anderson movies has become one default for harebrained humor in other countries. Or is it just an easier way to shoot groups of people?

Wuxia, fancy, plain, and very fancy

Painted Skin: The Resurrection.

Action cinema is a mainstay of FanTasia, and I caught several instances. Space Battleship Yamato is a live-action remake of the final installment in the anime series. As befits its origins, this version is rather classically directed, with prolonged medium shots and depth staging, as well as a soft texture that came through nicely on the 35mm print. It’s pure space-opera stuff, with a patriarchal captain passing authority to the young hothead and the emergence of romance between the hothead and the loyal young woman cadet. She turns out to be the secret source of energy that will turn the parched Earth into a green land again, but not without sacrifice in the long-established Japanese tradition.

To a large extent, the popular Chinese films of today are recycling tales and styles established by Hong Kong film in the 1980s and 1990s. Ching Siu-tung signed some of the best fantasy action films of those years (e.g., Duel to the Death, A Chinese Ghost Story, The East Is Red). Borrowing heavily from Tsui Hark’s 1993 Green Snake, The Sorceror and the White Snake offers your basic tale of the yearning and vengefulness of a woman-turned-demon. The main plot centers on White Snake, who falls in love with a herbalist and tries to pass for human. But Jet Li, looking like he’s suffered a few too many punches over the last three decades, is an abbot searching for demons to capture and imprison in his monastery. In a symmetrical subplot, the abbot’s young assistant turns into a bat demon but gains a friendship with White Snake’s counterpart Green Snake. When Li shows the herbalist his wife’s true nature, he breaks the marriage and unleashes White Snake’s fury.

Cue the video-game special effects for whirlwinds, floods, exploding temples, and soaring leaps. The airy effortlessness of all this comic-book spectacle made me yearn for the days of wirework; at least then gravitational heft limited the actors’ aerobatics. And cue a romantically inflated ending that pulls the couple apart to the tune of a duet sung by the pop-singer players on screen. A graceful, sinuous introduction of the two heroines (see the frame up top) and some interesting cutting in dialogue scenes (e.g., various scales of two-shots breaking up lines) couldn’t wipe away my sense that this has all been better done before–not least by Ching himself.

I did get my wire-work wish in Reign of Assassins, a pan-Asian project drawing on HK, PRC, Taiwanese, and Korean talent. Here Michelle Yeoh is given more to do than Jet Li was as the Sorceror. This film is engagingly old-fashioned, avoiding CGI for the most part and scaling the action to the everyday and the earth, not the sky. Michelle foreswears her past as an outlaw, undergoes the equivalent of plastic surgery, and tries to start fresh with a humble husband. But her old team’s search for the monk Bodhi’s corpse brings her back into action. In a plot twist reminiscent of the Shaw Bros. era, the husband reveals himself to be not all that she thought.

The fights are ingeniously staged by veteran Stephen Tung, but many are presented in that abrupt, disorienting framing and cutting that seems de rigueur these days. Taiwanese director Su Chao-pin is credited with story and direction, though a title on this print claimed the “co-director” to be John Woo, who was also a producer. On the whole, I respected Reign of Assassins more than I liked it. But nearly everybody thinks better of it than I do, as witness Justin Chang’s Variety review, the Hong Kong Movie Database reviews, and the customary detailed appraisal provided by Derek Elley in Film Business Asia. So maybe I should see it again.

The most elegant wuxia exercise I saw was Painted Skin: The Resurrection, fresh from its premiere at the Shanghai Film Festival (and in superb 35mm). King Hu made a version of the original tale in 1993, but this project has little relation to that, and only a tenuous one to the 2008 Hong Kong Painted Skin. That was a confused enterprise whose only redeeming feature seemed to me to be Donnie Yen. This installment more or less abandons the plot material of the 2008 film, while keeping many of the performers. It’s a solid, confident achievement, blending pathos, romance, and fantasy with an unhurried restraint largely missing from The Sorcerer and the White Snake.

Like that film, there’s a double plot centering on two female demons. A fox demon offers to swap her body for that of a disfigured princess, while in a minor-key subplot a bird demon develops affection for a demon hunter. Director Wuershan, fresh off his success with The Butcher, the Chef, and the Swordsman (2010), treats both the magic scenes and the erotic encounters with a grave warmth that elevates them above the genre standard. If you can have dignified eye candy, this movie offers it: sumptuous costumes and sets, striking but not go-for-broke special effects, combats that discreetly exploit the stammering ramping effects of 300. But the oscillating relations of the two central woman, tracing rivalry, complicity, envy, and loss, remain firmly at the action’s center.

Hong Kong filmmakers developed these mythic formulas in the 1980s and 1990s, when such “feudal” and “superstitious” subjects were forbidden on mainland screens. The slick assurance with which new mainland filmmakers have mastered this material suggests that in the new liberalization of the mainland market, they now own this genre. Painted Skin: The Resurrection has quickly become the biggest box-office hit in PRC history.

Crossovers

Carré blanc.

Everyone has noticed that genre pictures are getting artier, or art films are getting more genre-fied. Crossover efforts can yield strong results, as shown by movies as different as Let the Right One In and Drive. The title Eddie the Sleepwalking Cannibal would seem to signal B-movie giggles and gasps, but it turns out to be a tight, restrained study of the sadism driving artistic creativity….and a certain number of giggles and gasps.

A painter in a career slump, and following an unspecified “accident,” accepts a teaching post in a Canadian art school in hopes of calming down. He takes in a mentally deficient young man who grabs and eats animals while he’s sleepwalking, or sometimes sleeprunning.  When you learn that the painter’s neighbor is an obnoxious oaf with a perpetually barking dog, you begin to think that Eddie will be the painter’s means of securing peace and quiet. Actually, Eddie’s depredations unlock the painter’s creativity, inspiring a new burst of excellent work. Thereafter, he’ll need to keep Eddie on the prowl.

When you learn that the painter’s neighbor is an obnoxious oaf with a perpetually barking dog, you begin to think that Eddie will be the painter’s means of securing peace and quiet. Actually, Eddie’s depredations unlock the painter’s creativity, inspiring a new burst of excellent work. Thereafter, he’ll need to keep Eddie on the prowl.

The film balances gore, comedy, pathos, and satire of the art world. When the painter realizes that the young woman he’s slept with is a good sculptor, his efforts to deflate her using CritiqueSpeak reveal that his apparent humility covers an angry competitiveness. Eddie isn’t exactly Henry James on the creative process, I admit, but it’s not A Bucket of Blood either. The movie looks very trim and polished, with excellent sound work; I regret only the tendency to treat every dialogue scene in a fusillade of tight close-ups, which leads to a fairly unvarying pace. There’s a reason Coen brothers cut fairly slowly and stay far back; this sort of queasy deadpan tension benefits from steadiness and silence.

The screening of Carré blanc was preceded by La Jetée, as a tribute to Chris Marker. It was completely appropriate. For one thing, La Jetée hinges on one of the paradoxes of time travel: Can a man witness his own death? This sort of mind-bending was amusingly dealt with in Aleksey Fedorchenko’s “Chrono Eye,” one of three shorts in the portmanteau movie The Fourth Dimension. A scientist clamps a camera to his head and tries to tune himself to the future or the past, with the results transmitted to a beat-up TV receiver. The film makes clever use of the fallen-camera convention, and it ends with a rejection of past and future in the name of a vivacious present.

La Jetée was prophetic in another way. Before Marker’s film, most science fiction movies, from Metropolis and Things to Come to The Time Machine, used fanciful sets to conjure up the future. But Marker realized that one could film today’s cities in ways that suggested that the future was already here. This opened up a rich vein of exploration in Alphaville, THX 1138, Le Dernière combat, and their successors. And if you haven’t noticed: That future-tense present is always bleak, totalitarian, and something to escape from.

No wonder, then, that Carré blanc becomes an arty dystopian fable about a boy and girl brought up in a totally administered society. Philippe’s mother commits suicide so that he can be taken into an orphanage. There he will be turned into “a normal monster,” thus assuring his survival. Grown-up, he’s a high-level bureaucrat administering childish tests that his victims never seem to pass. But his marriage to Marie is withering. They can’t have a child, and she spends her days wandering the city. Eventually things come to a crisis and the couple must decide whether to stay or try to flee.

The plot is pretty formulaic and some of the absurd touches seem forced (the national sport is croquet). But the pictorial handling engages your interest from the start. Call it “1984 meets Red Desert,” except that there’s not much red here: bronze, black, and amber dominate. Simple techniques, like lighting that hollows out people’s faces to the point of blankness, become very evocative.

As in Alphaville, actual locations are made sinister by the dry public-address announcements saturating the soundtrack. The vast net stretched outside the couple’s apartment complex recalls the harrowing images of suicide-prevention nets at Chinese factory complexes. What a pleasure to see a movie designed shot by shot; the fixed camera yields one startling composition after another. Familiar as the story and themes are, the style grows organically from them. Carré blanc was the most impressive piece of atmospheric cinema I saw in my FanTasia visit.

So why was I here?

To see the movies. To catch up with old friends like Peter Rist and King Wei-chun and to make new ones. To present a talk on the Hong Kong action tradition. And to get an award for “Career Excellence.” Say hello to my lee’l (actually not so lee’l) frien’.

I’m very grateful to the coordinators of FanTasia for inviting me and honoring me with this magnificent award. It was an unforgettable week.

In addition to all this, FanTasia held an avant-premiere of the exhilarating ParaNorman (below). After I’ve seen it again, preferably with Kristin, I hope to write about it here.

Jason Seaver has blogged loyally about the festival on a daily basis. Liz Ferguson has a series of articles in the Montreal Gazette. A short interview with me appears on the FanTasia YouTube channel. Juan Llamas Rodriguez offers a two-part commentary on it starting here.

P. S. 11 August 2012: Daniel Kasman of MUBI has provided a link to Chris Marker’s little-known site Gorgomancy, which includes viewing copies of some of his little-known films.

P. P. S. 13 August 2012: Marc Lamothe–film director, co-director of FanTasia, and creator of DJ XL5’s Italian Dance Party–writes to explain the origin of the meowing.

Besides my national genre cinema tribute, every year since 2004 I’ve edited a short film program for FanTasia. It’s constructed the same way the Italian zappin’ was. I put static between films and include old vintage videos, ads and obscure film trailer in between films to simulate an evening of zappin’. This brings an energy and rhythm to short film presentations.

In 2008, I had a screening entitled DJ XL5’s DJ XL5’s Hellzapoppin Zappin’ Party. The program was constructed in 2 parts, with each part on a 60-min beta tape. Both part one and two contained episodes of Simon Tofield’s Simon’s Cat. To switch from beta one to beta two meant some 30 seconds of blackness and silence in the room. As Simon’s Cat made a strong and loving impression on the crowd, during the short intermission for chaning from tape 1 to 2 some people started meowing to break the silence. That made the others laugh and signaled their affection for the character.

This inside joke spilled over into more serious film presentations and has became a staple of our audience. Here’s the film responsible for the phenomena: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w0ffwDYo00Q.

Thanks to Marc for the information, and for a fine festival. Thanks also for his kind words about our work; he read the second edition of Film Art back in the early 1980s!