Archive for the 'National cinemas: Hong Kong' Category

Forget Pandora, visit Planet Hong Kong

Alternative cover for Planet Hong Kong 2.0. Not used. Sigh.

DB here:

The revised edition of Planet Hong Kong: Popular Cinema and the Art of Entertainment became available as an e-book on this site a year or so back. A couple of months ago, I announced that some print copies of the book are now available for sale. The response has been very gratifying—so much so that I’m moved to say that our supply is running out. So if you’re contemplating getting one, you should probably act soon. As indicated in the right-hand column of this page, you can get information about the book here, and you can order it from either Amazon or Biblio.

In particular, I wanted to reach out to college faculty who might not be interested in Hong Kong film but who might consider asking their campus libraries to order the book. My distributor, Twentieth Century Books of Madison, is well-versed in handling institutional orders and can fulfill them quickly. The e-book will continue to be available, but as someone who grew up using libraries a lot, I love the idea of libraries keeping print copies of the book for long-term preservation.

Thanks to everyone who has purchased a copy, digital or analog. The sales are enabling me to pay the costs of production, with a little left over to buy more Jackie Chan and Johnnie To DVDs.

For extra stuff that’s not in the second edition, start here. Our most popular entry on Jackie Chan is here.

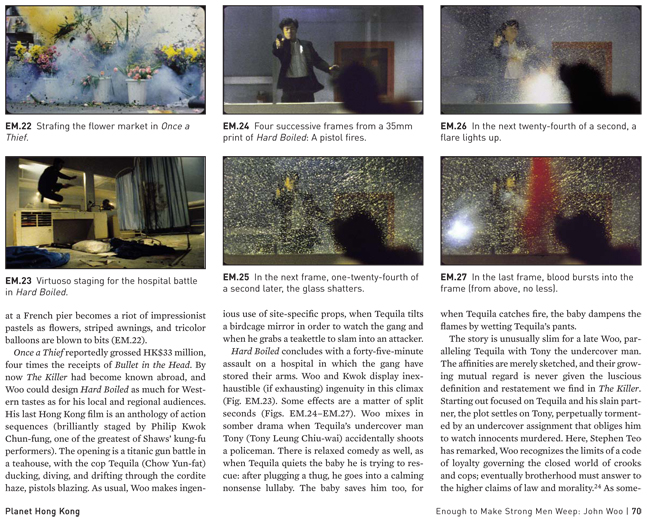

A sample page from Planet Hong Kong, second edition. As usual, thanks to Meg Hamel for making it happen.

Pandora’s digital box: From the periphery to the center, or the one of many centers

A laserdisc of The East Is Red; a VCD of Peking Opera Blues.

DB here:

On my first visit to Hong Kong in early 1995, one of my missions was to acquire video copies of all those HK films I wanted to study. The VHS tapes I’d seen in the States had grimy images and pan-and-scan framing. So, armed with my credit card, I focused on a higher-end format, the laserdisc.

For those too young or too sequestered to know this format, I should explain. A laserdisc was twelve inches in diameter, the size of a vinyl LP record, and coated with aluminum. A movie’s image track was inscribed optically on the disc, while the soundtrack was encoded digitally. The disc held about fifty minutes per side in the standard format, but some discs held less because they encoded the film exactly shot for shot. In that encoding system (called CAV), a still video frame was one film frame; the next still was the next actual frame. This was great for a frame-counter like me.

In the US, laserdiscs were for sale, but Hong Kong ones typically weren’t. They were a popular rental format, though, and you could use them to make nice tape copies. Needless to say, neither laserdiscs nor video tapes had copy protection.

As I made the rounds during my trip, I persuaded many shops to sell me some LDs, unfortunately for me at rather high prices. Although rentals remained brisk, the shopkeepers knew that LDs were on the way out. One charming young lady at Laser People, in Causeway Bay, told me of a new format they were waiting for. It would use a blue laser. Was it going to be as good as LD? I asked. She grinned: “Much, much better.”

On the same trip I met the LD’s downmarket cousin.

VCD = Very Curtailed Definition

Video Compact Discs (VCDs) were 4.8 inches across, flimsy, and cheap (US$4 for a legit one, much less for a bootleg). They could be played on computers or dedicated players. On the VCD format I found a copy of Peking Opera Blues, one of my favorite HK movies and one that was elusive on LD. So I bought it, along with a basic player.

The results were pretty feeble. Since the VCD was a CD-ROM, it could carry only about sixty minutes of video, at MPEG-1 compression. So a film was typically squeezed onto two discs. (Sometimes it was trimmed to fit.) Improvements were made over the years, but at a resolution of 352 x 240 pixels, the picture quality was hardly better than VHS tape. In a way, the image was more annoying than VHS because it tended to go very blocky and jerky. Some VCDs were letterboxed, but that compromised picture quality even more, since there were fewer lines devoted to the image.

Want some measure? Just above you find a VCD image from Peking Opera Blues, compared with an image copied (on photographic film) from a 35mm print. Sandwiched between the two, just for fun, is a frame grab from a recent Hong Kong DVD. (For more on these images, see the end of this entry.)

Debuting in 1993, the VCD was the answer to a film pirate’s prayers. VHS bootlegs degraded with each generation of copying, but digital video enabled every copy to be identical to the source disc. The pressing plants that manufactured music CDs could pump out VCDs en masse. By 1998 China had over 500 VCD companies and produced twenty million players per year. By 2000, players were in about a third of urban households. It became identified with low-end, Asia-centered piracy.

In the early 2000s, I saw boxes of VHS tapes chucked out onto the Hong Kong streets, and films were being released on DVD and VCD simultaneously. Piracy turned to the DVD, with results even more massive than with VCD. The newly affluent Chinese could afford the slightly costlier pirate DVD.

Meanwhile, the clumsy and heavy laserdisc was gone, preserved and on the shelves of fanatical, or just plain stubborn, collectors like me. The arrival of affordable DVD players in China in 1999 somewhat cut the interest in VCD, but recent releases today still come out on the junior format. In Hong Kong, VCDs outsell DVDs at a ratio of three to one, and titles older than a year or so go for US$3. VCDs rent more briskly than DVDs, at a cost of less than one dollar US.

Historically, I think, the VCDs played an important role. VCD made commercial movies available on a digital platform aimed at consumers. Invented by big Western companies, it was pushed aside in the rush to make the DVD the international standard. In addition, with the emergence of digital cinema, we might take the VCD as an emblem of a side pf the digital changeover that we often ignore. In surveying the results of opening Pandora’s digital box, we can’t neglect the ways that a triumph of Western research gets turned to ends that undercut the nations and companies originating it.

16mm: Digital exhibition’s dry run

Cinema has a long history of repurposing exhibition formats. A striking example is 16mm film. Invented by Eastman Kodak in 1923, 16 was suited to amateur moviemakers and news photography. Since the stock was non-flammable, 16mm films could safely be exhibited at home, in schools, in public meeting places, and in the newsreel theatres that sprang up during the 1930s and 1940s. The format was also used in screenings for the armed services. After the war, schools and community centers bought 16mm projectors, many from military surplus. My college film society had a pairs of 16mm JANs (Joint Army-Navy) machines, hulks that look like they could survive a torpedo attack. (See above.)

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, no public school was complete without 16mm projectors for screening educational movies, cartoons, and uplifting Hollywood features. At the same time, local TV stations broadcast from 16mm prints bought from the studios. These prints became sought-after by collectors, a group whose membership expanded with the rise of 16. The format became the standard for independent and experimental filmmaking, of course, but we tend to forget that it was also the bedrock of nontheatrical exhibition. In those days, Audio-Brandon, Contemporary Films, Janus, and other companies could actually make money circulating 16mm films.

For the US and Western Europe, with few exceptions, 35mm was the standard theatrical format, but other countries were more adaptable. The data on 16mm penetration of theatrical markets are very sketchy. (See the end of this post for more information.) Still, we have some bits of evidence. In 1961, Hungary reported having over 3600 16mm installations, as opposed to 803 35mm ones. In the same year, Romania claimed only 462 35mm screens and over 3100 in 16mm.

It seems that sectors of Asia relied heavily on 16mm. As late as the 1980s, India reported over 4500 16mm installations (as opposed to 8221 35mm venues) and Korea claimed nearly 400 (significantly more than its 280 35mm screens). The proportions are probably higher in countries like Thailand and the Philippines, where commercial entertainment films were made in 16mm.

With the expansion of 16mm, a format aimed for home, school, church, and other specialty situations was repurposed for a general public. “Nontheatrical” became theatrical.

The same thing happened, more clandestinely, with videotape after the 1970s. In large cities throughout Asia you could buy or rent bootleg VHS copies of Hong Kong and Indian movies. And there was no restraint on where you could show them. Throughout what was still called the Third World, video copies were exhibited in public venues, from town squares and pubic halls and to tour buses and work sites. Asian cities boasted “video parlors” and “video clubs” and “MTV parlors,” where friends could assemble in small rooms to drink, snack, flirt, and watch a movie, often a pirated Hollywood one.

This unofficial exhibition circuit is acknowledged in the warning that preceded many videos circulated in Asia.

The copyright proprietor has licensed the film (including its soundtrack) comprised in this Video Disc (including Laser Disc) for private home use only. All other rights are reserved. The definition of private home use excludes the use of this Video Disc at locations such as clubs, coaches, hospitals, hotels, motels, oil rigs, prisons, and schools.

Which is the same as admitting that tapes and discs were widely shown in clubs, coaches, hospitals, oil rigs, and other venues.

Much more recently, this “peripheral repurposing” of home technology for public use was taken to its logical conclusion in Nigeria. In 1992, local filmmakers began making VHS films for direct sales to customers. The market expanded with the rise of digital technology, and by 2008 production companies issued dozens of new releases on VCD and DVD each week. A few single-screen and multiplex facilities have been built to show Hollywood films on 35mm, but local movies are still largely screened at home and in informal public venues like restaurants and video halls using TV monitors rather than projectors. A $200 million dollar film industry emerged from technology designed for nontheatrical exhibition.

Overshoot and good enough

A stall selling Thai VCDs in Kowloon City, Hong Kong; from CNN Go.

The VCD fit smoothly into this pattern of low-end distribution and exhibition. But that wasn’t what Western firms had in mind when they invented the digital disc.

In 1993, JVC, Sony, and Philips created the Video CD. A year later the Hollywood majors announced that they would back a single standard for high-quality digital video. The companies laid down demands as to length (135 minutes per side), picture quality (better than laserdisc), compatability with high-quality audio systems, and, among other criteria, content protection. As usual, two major rivals emerged, but they were reconciled. Patents were pooled, and after more wrangling about copy protection the DVD more or less as we know it made its debut at the end of 1997. After more fixes, the format took off in 1999, aided in no small measure by the DVD release of The Matrix.

It seems to me that Western firms’ concentration on the DVD and the sidelining of the VCD exemplify what management analysts have come to call “overshoot.” In the theory of disruptive technologies pioneered by Clayton Christensen, established firms aim to sustain an existing technology, either through incremental improvements or radical innovations. As the technology improves, these sustaining firms target the upper end of the market. Thus Eastman Kodak strove to improve its film stocks to satisfy and win the approval of the world’s top cinematographers. Likewise, Sony and other firms collaborated to create the DVD as an improvement on broadcast video, VHS, and laserdisc.

But in the process they left lower-end markets behind. Entrenched sustaining technology tends to be complicated, inconvenient, and expensive. Christensen posits that the big firms’ overshoot often leave space for firms that develop technology that is cheap, convenient, and “good enough” for what might be a very big segment of purchasers. To the professional eye, VHS was inferior to Beta tape and laserdisc, but for most consumers that tape format was good enough. Then DVD proved more convenient—smaller, more portable, easier to use—and of noticeably better quality. Experts knew that the DVD was still a compromise format, especially compared to 35mm, but for consumers it was good enough.

Overshoot encouraged the spread of the VCD. Concentrating on the DVD and its MPEG-2 protocol, Sony and its co-developers licensed the downmarket format to Asian companies. It was clear that the Chinese market, massive though it was, couldn’t afford DVD players and discs. (In 2000, China’s per capita income was about $1500; a cheap DVD player cost about $200.) But local entrepreneurs rushed to expand the low end of the market. Shujen Wang, in her very informative book Framing Piracy: Globalization and Film Distribution in Greater China, explains that it was easy for Chinese manufacturers to convert audio CD players into VCD players, thereby undercutting the imported models. By 2000, a China-made VCD player cost $30. As a further incentive, some makers included up to 100 free VCDs with purchase of a player.

Millions of players were sold in the mid-1990s, and many were installed in what Variety called “illegal video projection rooms that had screened pirated videos and movies not previously shown in China.” By 1994 there were more than 150,000 public video venues showing tape, laserdisc, and VCDs in the mainland. The following year, piracy was reckoned at a stunning 100% of the market.

Probably Western companies couldn’t have satisfied the market in Asia; local manufacturers, distributors, and retail outlets were needed to make the sales happen. So it probably wasn’t simple neglect that made VCD a de facto regional standard. Nonetheless, the VCD became a disruptive technology. For Asian consumers, laserdiscs were too expensive, VHS was comparatively inconvenient, and digital discs and players suddenly became much cheaper. And with so many movies, mostly illegal, available on the format, the buyer’s and renter’s choice was simple.

VCD was good enough–not just for private consumption but for public exhibition. Once film exhibition on tape had become widespread, the VCD made that practice far more feasible. It provided something like the world’s first “digital cinema” experience.

I’m not competent to trace the VCD’s fortunes in other countries, although it proved popular in India and Latin America. In cities and towns, entrepreneurs set up “electronic cinemas”–that is, video parlors or auditoriums screening discs, usually pirated, to paying audiences. A 1999 report in Variety Deal Memo notes:

Electronic cinema is nothing new in emerging countries with dilapidated or non-existent conventional film projection cinema infrastructure. Small-scale mobile electronic cinemas have set up in small towns for years. . . . Cinetransfer International, for example, offered rural areas in Mexico electronically-screened Mighty Joe Young, A Bug’s Life, The Water Boy, and other films over the years.

Once again, the nontheatrical becomes theatrical, but this time aided by digital technology.

Good enough is better than what we had?

From the rise of the VCD and later the DVD, it’s only a short step to digital exhibition as the West might recognize it. Again, Asia played a key role. Initially, the Western digital cinema projection standard was 1.3K resolution (1280 x 1024 pixels). This became a bone of contention. A Variety article from 2002 asks the disruptive-technology question: “How good a picture is good enough to replace film?”

One end of the spectrum says, ‘Let’s do it now. This is good enough,” says Charles S. Swartz exec director and CEO of USC’s Entertainment Technology Center, which tests digital cinema systems. “At the other end, they’re figuring out the theoretical best we can do and want to hold off.”

While filmmakers in the West debated whether 2K was good enough, exhibitors in developing countries didn’t hold off. In Brazil, small cinemas and chains began adopting 1.3K projection. In India, UFO Moviez and E-City Digital installed low-resolution projection systems in hundreds of theatres, often fed by satellite. Many local observers considered these video displays worthwhile improvements on the battered prints and faded arc-lamps that were staples of most village screenings. Now good enough was better than what went before.

Through the early 2000s, China and the US led the world in digital screens, most on the 1.3K format. The US leaped ahead in 2005, when the Digital Cinema Initiatives standardized 2K resolution. But China will pick up velocity because it’s opening new screens daily. From 2009 to 2010, China leaped from 1788 D-screens to 7920. At the current rate China is opening five new screens each day. You will not, I expect, find a piece of 35mm film in any of them.

In China and India, despite some movement toward 2K projection, the “good enough” strategy persists. Many domestically made Chinese films are released in 1.3K versions, and some are even shot in .8K (1024 x 768 resolution). These can’t be encrypted, and so pirates are making the most of the situation. Even television channels show pirated copies of local movies. And India’s major supplier of digital projection, UFO, works with the MPEG-4 codec used in Blu-ray. This has caused complaints from viewers, but the company’s managing director claims, “In a market with ticket prices averaging between Rs 10-50 [US$.20-$1.00], there is no way DCI standards will take off in India.”

It’s worth remembering,then, that movie viewing on the “periphery” was digital before digital was cool. The swift rise of digital exhibition in China, India, and other major markets has led Hollywood down the same path. You might recall the techno-nerd’s prophetic line in David Byrne’s True Stories: “The world is changing. And this is the center of it right now. Or the one of many centers.”

Much of the information above comes from the indispensable IHS Screen Digest. Other sources, not available online as far as I know, are “Electronic projection rollout excites, worries cinema industry as cost, quality, retrofit issues loom,” Variety Deal Memo (5 July 1999), 5-8, and “Country Profile: China,” Variety Deal Memo (11 October 1999), 5-8. I’ve mentioned Shujen Wang’s valuable book in the text, but go here for her 2003 paper on digital piracy in China.

See also Hu Ke, “The Influence of Hong Kong Cinema on Mainland China (1980-1996),” in Fifty Years of Electric Shadows, ed. Law Kar (Hong Kong International Film Festival, 1997), 164-178, and Darrell William Davis and Emilie Y. Y. Yeh, “VCD as Programmatic Technology: Japanese Television Drama in Hong Kong,” in Feeling Asian Modernities, ed. Koichi Iwabuchi (Hong Kong University Press, 2004), 227-247. A Google Reader version of the latter is available here. In Playing to the World’s Biggest Audience: The Globalization of Chinese Film and TV, Michael Curtin goes beyond technology and analyzes other market forces affecting VCD.

For basic historical and technical information on digital formats I always turn to Jim Taylor, Mark R. Johnson, and Charles G. Crawford, DVD Demystified, 3rd ed. (McGraw-Hill, 2006). Useful reports on the progress of VCD appeared in The Economist here and here. I talk a bit about the rise of digital exhibition in China and Hong Kong in Planet Hong Kong, available here. For background on current VCD trends I’m grateful to a friend in Hong Kong who wishes to remain anonymous.

My comparison of VCD, DVD, and 35mm isn’t entirely fair to the digital formats. Frame grabs tend to look worse than an image displayed on a video monitor, and an HDMI display of the VCD and DVD improves them. Moreover, the Hong Kong DVD isn’t particularly well-authored. A Blu-ray of Peking Opera Blues that I’ve ordered hasn’t yet arrived, so I will update this entry with a frame from that when I can. Finally, my 35mm frame enlargement is a bit too warm and could use some adjusting. But to keep comparison reasonable, I didn’t apply Photoshop to any of the images shown here.

It’s hard to know how widely 16mm film was exhibited commercially around the world, but some indications are given in Statistics on Film and Cinema 1955-1977 (Paris: Unesco, 1981) and various editions of the UNESCO Statistical Yearbook. A pleasant video devoted to JAN 16mm projectors is here; I grabbed a shot from that video above, so thanks to maynardcat for posting the footage.

Why are oil rigs singled out as targets of pirate screenings? My guess: Many Asians emigrated to work on oil extraction throughout Northern Europe and the Middle East, and it wouldn’t be far-fetched to assume that videos were screened for them on site. If anyone reading this can confirm, deny, or nuance, please correspond.

Clayton M. Christensen’s influential formulation of the theory of disruptive technologies is in The Innovator’s Dilemma (orig. 1997). Thanks to Jim Cortada for discussing these ideas with me. Volume 2 of Jim’s Digital Hand trilogy remains the best guide to how computers transformed the media landscape.

“Things fall apart. It’s scientific.” True Stories (1986).

PLANET HONG KONG 2.0 goes analog

Metade Fumaca (1999).

DB here:

In the Web age, physical books become e-books, and virtual books, often self-published, can mutate into tangible things of paper and glue. That’s what has happened to Planet Hong Kong 2.0.

The story so far: In 2011 I revised the old version. I updated the existing chapters and added four new ones. Our web tsarina Meg Hamel designed a very nice pdf version of it, with over 400 color pictures and an ingratiating layout. That is still available for $15 elsewhere this site.

I had pretty good luck with selling the e-book online, having earned enough to pay the costs of designing it. It would be nice to sell more and pay myself a little for my work. Did I mention that it’s still available for purchase here?

In the meantime, last spring I had Park Printing of Verona (Wisconsin) make some physical copies. We used high-grade paper, and the result is a very fine-looking book, measuring 11 x 8 ½ inches. I prepared them as presentation copies to the many people, particularly in Hong Kong, who had helped me in writing the 2000 edition and this one.

I’ve presented those copies to those people. I have a few copies left.

I could just hang on to them, but some people have told me they would a prefer print copy to the pdf. A few libraries have likewise expressed interest in a physical book.

So I’m making Planet Hong Kong 2nd ed. available for $60 plus postage Amazon and at Biblio. The vendor is 20th Century Books, an outstanding shop here in Madison specializing in comics, fantasy, s-f, and mysteries. (Thanks, Hank and Deb.)

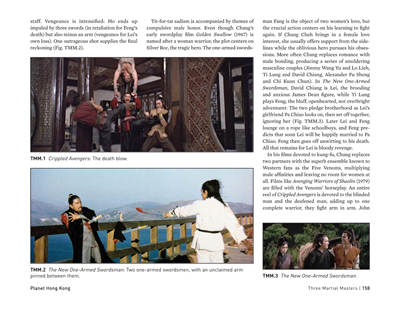

The list price of PHK 2.0 analog reflects the costs of making a small print run of a heavily illustrated book. Here are a couple of sample pages. Illustrations were scanned from 35mm frames.

If I’d had my wits about me, I’d have done this before the holidays so I could advertise it as the perfect gift for that hard-to-please film fan on your list. In any case, if you’re a reader, collector, or librarian, you can acquire a hard copy of the book from Amazon or Biblio. And the e-edition remains available on this very site. . . .

Coming up later this week: Another entry in our series, Pandora’s digital box. This one is about how digital formats have affected film festivals. It’s not a pretty tale.

The Mission (1999).

PRINCIPLE, with interest

DB here, still at the Vancouver International Film Festival:

The Milkyway films of Johnnie To Kei-fung have resisted some of the fancier tactics of contemporary cinema, such as self-correcting flashbacks and forays into what-if universes. It’s true that he has played a little with disorienting subjectivity (The Mad Detective), and his intricate plotting in films like The Mission have something of the feel of converging-fates stories. But his chief devices, I tried to argue in Planet Hong Kong and occasionally on this site, have been laconicism and ellipsis.

Hollywood dramaturgy tells you something important three times, but To’s films often just mention a key story point in passing. If you miss it, you’ll have to try to recall it later, even after the film is over. Likewise, in Hollywood films, any time periods that are skipped over are assumed to be irrelevant to the plot. But To’s films (like Lang’s) omit showing us intervals that later prove to be quite important. Taken together, the laconic and elliptical approaches to storytelling make The Mission, Running Out of Time, The Longest Nite, The Mad Detective, and the last episode of Triangle into narrative games–games of wits among the characters, but also between the filmic narration and the audience.

With Life without Principle, fresh from screenings at Venice and Toronto, To embarks on a full-blown network narrative. The film follows three clusters of characters across three days, with the last day showing the collapse in world stock markets caused by the Greek debt crisis. All the characters are tied to this macro-event. Police officer Cheung and his wife Connie are about to buy an apartment, the bank investment advisor Teresa sees her customers lose thousands, and the triad Panther partners with his old friend Lung just before Lung’s market maneuvers crash.

Each character has more personal concerns as well. Cheung has learned that his dying father has taken a Mainland mistress, and he and Connie must decide whether to adopt the woman’s child. Teresa’s sales record is poor, and she’ll lose her job if she doesn’t generate more business. Panther needs money to bail out an errant triad colleague. Tying together all three strands is the gloating moneylender Yuen, who scoffs at the stock market and points out that he offers better terms than credit-card companies.

Designing a network plot offers you essentially two options. You can intercut all the strands as the protagonists move through time together (as in Nashville) or you can segregate the plotlines into blocks, as in the “chapters” of Pulp Fiction or the character-tagged chunks of Go. In the block pattern, some chronological fiddling will be necessary. We follow one character or group through story events and then hop back to an earlier period in order to follow another strand.

Mild spoilers start here.

Life without Principle takes the block option. A prologue shows Cheung investigating a murder and Connie trying to buy an apartment for them. The bulk of the film starts by following Teresa through the days leading up to the financial crisis. The narration then glides back to the evening of the first day and we meet Panther, an obsequious but loyal triad working for a self-centered boss. Panther eventually joins his pal Lung in an internet stock swindle. The two plotlines converge at a murder in the bank’s parking ramp, involving HK $10 million in cash. In its final stretch the film starts crosscutting among Teresa, Panther, Lung, Cheung, and Connie. Each line of action comes to a distinct climax, only tangentially related to the others but still tied together by the fluctuations of the stock market.

Still, Johnnie To offers a network narrative on his own terms. Where a Hollywood film is careful to tell us when it skips back in time, usually by use of titles, To’s playfully laconic narration eliminates titles. Instead, the transitional marker is a rightward tracking shot of Hong Kong Island accompanied by jaunty a capella music in Swingle Singer style. More generally, To doesn’t mark the three days overtly within Teresa’s and Panther’s tales. To is more interested in creating a flow across each story rather than that sense of modular architecture we get with modern day-by-day plotting.

Moreover, the tonal shifts that we find in many Milkyway films help keep the stories distinct. Teresa’s and officer Cheung’s plots are straightforwardly dramatic and suspenseful, while Panther’s is grotesquely comic—a quality underscored by Lau Ching-wan’s blinking portrayal of a dense but compulsively earnest company man. The spaces are at variance too. Teresa is never seen outside the bank building (until the last shot), and so the action in her story is built around enclosure and small details, especially a crucial key. Panther’s story is expansive, roaming from a triad banquet to the streets and cafes of Kowloon.

The film relieson classic suspense techniques to an unusual degree , especially the passages in Teresa’s office. Moreover, we always like a drama that forces sympathetic characters to make bad decisions. Cheung, who impassively does his duty as a good cop, ponders disowning the half-sister he never knew he had. Panther, abused by his boss and his pals, remains naively loyal to them.

Our keenest investment, I think, is in Teresa’s situation. Rapacious bank policies make her sell chancy investments to people who can’t understand them. Her scenes with the aged Hi Kun, blindly buying into a high-risk fund, consume an agonizing ten minutes, and throughout you sense Teresa’s qualms about the scam she’s pulling. When she goes to fetch Hi Kun coffee, she pauses meditatively over the cup: laconic To again. Later, when Teresa is confronted by massive temptation, all our instincts urge her to succumb, even though it would be a crime.

Will these basically decent people come through the financial crisis unscathed? The Milkyway universe can be harsh and capricious. Expect the unexpected.

So Hang-shuen, Denise Ho, and Johnnie To on the set of Life without Principle.