Archive for the 'National cinemas: Iceland' Category

Vancouver 2019: Happy endings, art-film style

Tehran: City of Love (2018).

Kristin here:

The Vancouver International Film Festival has several strong threads running through it: world art cinema, documentaries, Canadian cinema, and films about art and artists. Sticking to any one or two of these would make for a rich viewing experience. I gravitate toward the “Panorama” program of mostly fiction films from around the world.

At one of these films, Tehran: City of Love, the Iranian director, Ali Jaberansari, and scriptwriter, Maryam Najafi, were present for a Q&A session. Clearly the audience has been charmed by their tale of three remotely connected characters all seeking love. One questioner asked what the pair’s next project was, which must always be cheering to the filmmakers. Another audience member simply thanked them for the film, saying that after seeing several grim movies, it was a pleasant experience to find one so funny and entertaining.

[Spoilers to come]

Certainly Tehran: City of Love is an entertaining film, but its ending is bittersweet at best. All three protagonists, after brushes with romance, end up alone. All may have learned something along the way, but they are all saddened by their failures. This year I have seen a couple of other films where the happy ending consists mainly of the central character letting go of bitterness and becoming reconciled to his fate. It seems as though grim storylines with unhappy endings are a staple of the festival film, and even comedies often avoid sending their audiences out on an entirely cheery note. Perhaps there is an assumption that an art film that is too entertaining risks not being taken seriously by festival programmers. Luckily, these three were included in the VIFF program.

Tehran: City of Love (2018)

Tehran: City of Love presents three central characters who are looking for love. Each has a problem to overcome. Mina is an overweight receptionist who, apparently resigned to her single status, targets attractive men who visit the cosmetic surgeon. She calls each, speaking seductively and arranging a date. She shows up for the date but does not identify herself, instead watching the man from a nearby restaurant table until he gives up in annoyance and leaves. At a class on the “geometry” of love, she meets a pudgy man who begins a courtship

Hessam is a body-builder with three championship titles in his past, now working as a trainer. He receives a part in a dubious film project and at the same time begins training an attractive young man who aspires to a championship. Hessam’s attraction to his trainee is subtly conveyed (above), and the young man seems friendly and seems possibly to reciprocate Hessam’s feelings.

Vahid, a talented mosque singer specializing in funerals, is dumped by his fiancée. A friend counsels him to become more lively and cheerful by singing at weddings. Vahid quickly makes the transition, which seems to improve his mood. He becomes friends with Niloufar, a female wedding photographer, who likes him but–as we know and Vahid doesn’t–she is awaiting a visa to allow her to emigrate to Australia.

Disappointments result. Mina’s beau is a married man in the lengthy process of divorcing his wife. The young man notices Hessam’s interest in him and switches to a new trainer. Niloufar reveals her imminent departure from Iran.

Tehran: City of Love is an impressive film for a second feature. The script by Jaberansari and Najafi weave the three stories together skillfully, keeping each story and the thematic connections among them perfectly clear. One might expect the three protagonists’ plotlines to come together. Hessam does at once point come to Mina’s office to get Botox treatments (presumably motivated by the film he is supposed to act in or to make himself more attractive to the young trainee), but nothing comes of that. Mina is close friends with Niloufar, but although the two talk about Vahid casually, Mina never meets him. The three characters are by chance in the same space by the final shot, but they remain unaware of each other. The title, unless we take it to be ironic, suggests that each may try again to find a partner, but the ending only hints that each has at least gained something from his or her brush with love.

It is also beautifully shot in widescreen, often employing what David has termed the planimetric shot, with the camera axis perpendicular to the background (see above and top). During the Q&A Jaberansari mentioned some of his film influences. (He was trained abroad in Vancouver and in London, where he now lives.) These included Roy Andersson, Elia Sulieman, Jim Jarmusch, Aki Kaurismäki, Jacques Tati, Fassbender, and Buster Keaton. Although Tehran: City of Love does not resemble any of these directors’ films closely–there are few long-take scenes or physical comedy played out in long shots–the list makes sense, mostly in the tone of the film.

Jaberansari and Najafi provided some helpful cultural context. They shot the film with official permission and also have permission to release the film in Iran, though no date for that has yet been determined. Despite the implied homosexuality of one character, only two minutes of cuts were required for the domestic distribution permit.

The emphasis on body-building, both in the gym and the scenes of men exercising in a mosque, reflects the fact that without bars, night-clubs, and other forbidden gathering-places, gyms and body-building are one milieu in which men can come together, including gay men.

At one point Vahid is arrested while singing at a “private” wedding. The phrase seems harmless enough, but private weddings often include men and women mixing in ways forbidden in the public weddings at which Vahid had previously performed.

Australia, they note, is the new destination of choice for Iranians seeking to move abroad, replacing Canada to some extent.

Sometimes Always Never (2018)

This film is largely a vehicle for Bill Nighy, contributing a mix of comically self-centeredness and pathos as Alan, a retired tailor. Years before his elder son Michael walked out of the house during a game of Scrabble and has never been heard from again. Alan has since been looking for him, neglecting his younger son, Peter, as well as his daughter-in-law and grandson.

Scrabble looms large in the plot. In one extended series of scenes, Alan and Peter show up in a small town to view the body of a young man who might be the missing son. During an evening in a bed-and-breakfast, Alan hustles the husband of a couple staying there, pretending to be an ordinary Scrabble player and winning £200 off the henpecked husband (above). Only later is it revealed that they, too, are there to examine the same corpse. Alan goes first emerges tactlessly and cheerily saying that the body is not Michael, despite the fact that the couple is about to perform the same grim task.

First-time feature director Carl Hunter adopts a playful style which at times resembles that of Wes Anderson. As with Tehran: City of Love, there are the planimetric shots(on a beach in Crosby otherwise populated by Anthony Gomley’s life-size statues, at bottom, and above, in the bed-and-breakfast Scrabble game). The characters drive in cars with blatantly obvious back-projected motion, and there are black-and-white inserts and brief animations. All these stylistic touches help lighten the tone of the underlying misery of the characters, though they also stand apart from the fairly straightforward presentation of most of the scenes.

The growing closeness between Alan and his shy grandson helps add a positive side to Alan and prepares the way for the inevitable outcome, as he learns to value the son he has over the one who clearly will never return.

A White, White Day (2019)

Most small producing countries have managed throughout the history of cinema to make films, and Iceland has been no exception. It was not until the 1990s that its films started attracting attention on the festival and awards circuit, but only now and then. Even today the local feature production hovers around only four a year. Still, we have learned to consider Icelandic films must-sees when they show up on festival programs.

Benedikt Erlingsson’s films have shown here in Vancouver, and we reported on Of Horses and Men in 2014 and Woman at War last year.

This year the contribution from Iceland is Hlynur Pálmason’s A White, White Day, his second feature. (His previous feature, Winter Brothers, played at our 2018 Wisconsin Film Festival, but we were in the process of buying a new house and missed it.)

“A white, white day” is a local phrase describing weather conditions that cause land and sky to become indistinguishable. It’s a perfect metaphor for confusion, for loss of bearings. We see it both literally and figuratively in the film. The protagonist, Igimundur, is a middle-aged policeman on leave for depression following a car accident that killed his wife. The film opens with the accident, although we don’t yet know who the driver is, occurring on a white, white day.

There follows a mesmerizing series of shots from the same vantagepoint, showing a lengthy series of shots of a pair of small buildings in a rural landscape, including these two.

All atmospheres and times of day area shown, from the light fog of the top shot to the heavier fog of the lower one, from bright sunny days to dark nights. Horses wander through in some, cars drive up in others, and gradually the ramshackle yard and structures become a home. We first glimpse Igimundur in the lower shot, though we don’t yet know who he is. The renovation of the buildings to make a home for his daughter and son-in-law, along with his beloved granddaughter Salka. Where Igimundur will go once they move in is never mentioned. Clearly the project is his way of coping with his grief, while he increasingly scorns the lack of help he receives from his psychologist.

Soon, however, he comes to believe that his wife had been having an affair, and he becomes increasingly abusive and violent, even toward his police colleagues and in front of Salka. The happy ending, which seems a trifle abrupt, sees him finally reconciling himself to the past and regaining his loving memories of his wife.

A White, White Day depends less on humor than the other two films, despite its occasional comic touches. Instead it is an absorbing family melodrama that most audiences would find entertaining.

For a useful brief history of Icelandic cinema, see here. So far it doesn’t include Palmason, but I expect he will soon be added.

We thank Alan Franey, PoChu Auyeung, Jenny Lee Craig, Mikaela Joy Asfour, and their colleagues at VIFF for all their kind assistance. Thanks as well to Bob Davis, Shelly Kraicer, Maggie Lee, and Tom Charity for invigorating conversations about movies.

Sometimes Always Never (2018).

Vancouver 2018: A Panorama of the Rest of the World

The Wild Pear Tree (2018).

Kristin here:

Venice, Telluride, and Toronto get a great deal of attention, since obsessive, year-round Oscar-predicting has become a way of life for some reviewers and industry commentators. In contrast, Vancouver has few premieres, but it quietly gathers up a huge international range of films, most of which have already played other festivals. It offers a chance to see fine films, many of which will never enter the radar of those who search only for Oscar bait. Venice and Vancouver, the two VIFFs, offer a perfect combination to keep us up-to-date.

There are several major threads in the program, including documentaries, socially impactful films of all sorts, Canadian films, and so on. I tend to favor the Panorama: Contemporary World Cinema thread, since it’s the one that basically breaks down the ROW (the Rest of the World) by country, and I try to see a wide range of world cinema. It’s also where familiar auteurs that I follow tend to show up.

This entry covers three films by directors whose work I have seen and admired, representing Iceland, Turkey, and Poland. More ROW films to come.

Woman at War (Benedikt Erlingsson, 2018)

Four years ago David reported on Icelandic director Erlingsson’s first feature, Of Horses and Men. This year we enjoyed his second, Woman at War. It tackles the difficult task of making a heroine who is basically a terrorist, though one might more tactfully call her an rather extreme environmental activist.

We first see her taking out the local power grid by firing a wire via bow-and-arrow over power lines in a remote rural area (above). She’s resisting a large Chinese investment in Iceland’s infrastructure, and she seems to be succeeding. The Chinese have postponed the deal, but she carries on her nearly one-woman crusade, aided only by a government official who is getting cold feet as the search for the “Mountain Woman” saboteur escalates, and an “alleged cousin,” a gruff farmer who rescues her more than once.

David praised how visually Erlingsson told his tale in Or Horses and Men. The same is true for the long scenes of Halla’s forays into the countryside for her subversive errands, as well as her preparations. She is clearly a highly adept and well-equipped saboteur, and she’s bold and skilled enough to outfox the military pursuers who send helicopters and drones after her.

Despite the serious theme, Woman at War is a lighthearted film. As Variety reviewer Jay Weissberg put it, “Is there anything rarer than an intelligent feel-good film that knows how to tackle urgent global issues with humor as well as a satisfying sense of justice?” One could called Halla a terrorist, but the audience we saw it with was clearly on her side, hoping for her to escape at each narrow brush with the law.

The whole thing is funny enough to be termed a comedy, or at least a dramedy. Halldóra Geirharðsdötter makes Halla an irresistably likeable character, and Erlingsson gives her emphatically ladylike activities in her life outside her clandestine campaign: she conducts a local choir and is in the process of adopting a Ukrainian orphan.

One daring move that Erlingssohn makes is to put the musicians playing the accompanying musical track onscreen, both a chamber group of three male instrumentalists who crop up nearly everywhere Halla goes, and a trio of female singers in Ukrainian dress who appear in scenes relating to the adoption. At first this seems like a joke simply repeating the one early in Blazing Saddles where the hero rides past Count Basie’s Orchestra playing the apparently nondiegetic sound track in the middle of a desert. Here the musicians appear through most of the film. They help avoid having Halla alone onscreen for long stretches of time, they appear sympathetic to her changing situations and hence cue us to sympathize with her, and they provide part of the film’s comedy. They took some getting used to, but I think the “onscreen nondiegetic music” device worked overall.

Shortly after its premiere in the Critics Week thread at Cannes, Woman at War was picked up for North America by Magnolia Pictures. Audiences should give it a look, since it’s a real crowd-pleaser.

The Wild Pear Tree (Nuri Bilge Ceylan, 2018)

My entire knowledge and admiration of Turkish director Ceylan’s work come thanks to VIFF. In 2011 we wrote about Once upon a Time in Anatolia and in 2014 about Winter Sleep. This year The Wild Pear Tree is being shown.

It’s a very fine film, though I doubt audiences will embrace it to the extent that they did Once upon a Time in Anatolia or even the less popular Winter Sleep. The former may have qualified as slow cinema, but it had the advantage of being a mystery centered around a murder and a lengthy search for the missing body. In the process it became a character study and a quiet satire on the police. Winter Sleep was more talky, but it featured arguments between two witty people, a crotchety ex-actor and his acerbic sister.

In The Wild Pear Tree, Ceylan tackles the challenge of another film with long conversations. But this time the plot centers around Sinan, an opinionated, bitter, argumentative recent college graduate returning to his hometown. He is, in short, an obnoxious protagonist, and we’re attached to him in nearly every scene. He argues with his father, a teacher with a serious gambling addiction that has impoverished the family, with his mother, whom he blames for putting up with his father’s problems, and with essentially with anyone else he encounters.

Sinan’s stated goals are simple: to publish a book of his own poetry and fiction and to become a teacher in the eastern part of Turkey, as his father had early in his career. He also reluctantly faces performing his required military service. Yet he doesn’t study for the teaching exam, perhaps out of laziness or perhaps because he fears following in his father’s footsteps.

The result is a film that I found more admirable than likeable. Certainly its portrait of Sinan captures a certain recognizable type of self-assured, stubborn character, and there is a certain humor in that portrayal.. The highlight for me was a lengthy conversation between Sinan and Mr. Süleyman, a successful local novelist whom he spots at work in a local bookshop. Receiving permission to ask a single question of the man, he sits down and proceeds to question him at length, in the process managing to imply that he knows more about writing than Süleyman does. Sinan even pursues him out of the store and down the street, arguing, until Süleyman finally loses his patience and berates the young man. Any professor will recognize this spot-on depiction of a tiresomely persistent, argumentative student.

I found the ending a bit too pat and easy. Sinan’s military service, rendered in one relatively brief shot, apparently purges him of much of his anger with his life, and the final reconciliation with his father seems to come far too easily.

The film is beautifully photographed (see top), as always, by Gökhan Tiryaki, this time using a Red 6K digital camera.

Cinema Guild plans an early 2019 release for the film in North America.

Cold War (Pawel Pawlikowski, 2018)

Polish director Pawel Pawlikowski’s first feature film since the award-winning Ida (2013) is quite a departure from that film’s austerity, despite again being beautifully filmed in black-and-white film with an Academy aspect ratio. It follows the tempestuous relationship between a young singer and the composer-pianist who mentors her and becomes her lover. The backdrop is the era from 1949 to the mid-1960s, set mostly in Poland but moving among the European cities that the pair visit, alone or together.

Cold War establishes an immediate appeal by showing a man, Wiktor, and his partner Irena (professional and perhaps personal) making ethnographic recordings of untutored peasants singing and playing traditional folk songs. The pair join the faculty of a state school for young singers, instrumentalists, and dancers. One auditioning singer, Lula, attracts Wiktor, and the two are soon involved in an affair that lasts, on and off, until the end of the era.

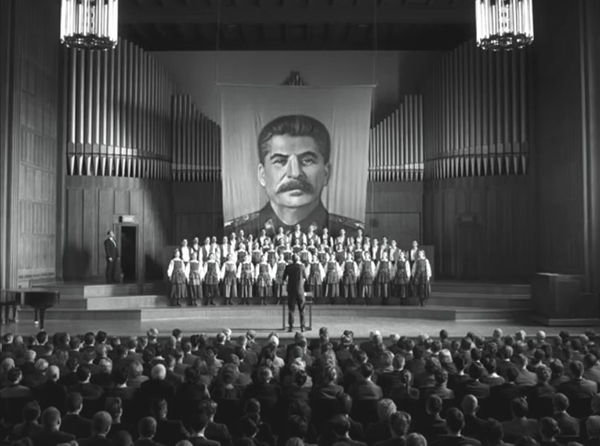

The film’s first half is fascinating, with its presentation of Polish folk-songs and dancing. The troupe formed by the school’s students becomes a success by presenting more professionally rendered versions of the folks songs and dances that had been collected. It soon attracts the attention of Communist authorities who pressure the Wiktor, Irena, and the manager, Kaczmarek, to add pro-Stalinist numbers to their program, and soon the group is singing “The Stalin Cantata” to equal success (see bottom).

Scenes fade to black at intervals, with the new scene appearing with a title giving the time and place of its action. These temporal jumps forward become more frequent as Wiktor becomes disgusted with the government’s control over the group’s program and flees to Paris. Thereafter the original troupe is left behind, and we see a series of scenes in which Lula’s path crosses Wiktor’s.

The result is that the second half of the film seems sketchier and less interesting. The action repeats, with variations, and the music that the pair perform is more familiar.

The highlight of this late part of Cold War is a scene which breaks loose briefly from the lovers’ travails. Lula and Wiktor at in a bar, and she, thoroughly drunk, initially begins to dance by herself to “Rock around the Clock.” In a remarkable long take, the camera moves among the wildly dancing couples as Lula passes from one partner to another and other couples pass by in the foreground and background (above). The moment must have been carefully choreographed, with the camera always capturing key moments of Lula’s enjoyment of the music, while simultaneously suggesting spontaneity and the crowd’s utter abandon to the music.

Cold War‘s music has been singled out by reviewers as a crucial ingredient. The film begins with craggy peasants performing genuine folk music in a muddy street and eventually takes us to Lula tarted up in a black wig and sequined dress singing a bizarre Polish version of “Baio Bongo,” a popular South American import deemed safe for audiences in the Soviet sphere. In between there are folk songs and dances, Stalinist choral propaganda, jazz, torch-song versions of the folk songs heard earlier, and rock-and-roll.

The film provides almost no background information about the two main characters or what they do in the several temporal gaps, some years long, covered by those fades. This makes it difficult to sympathize deeply with Wiktor and Lula’s long, ill-fated romance.

Pawlikowski in fact concocted some backgrounds for them, which he discusses in the film’s pressbook (posted in its entirety on Antti Alanen’s blog) .It draws upon extensive quotations from the director. There is considerable information about the historical, political context, including the fact that Wiktor and Lula are based on his parents. There is also discussion of the music, cinematography, and casting.

Pawlikowski speaks of the frequent ellipses as the film jumps forward in time:

Very often films, especially biopics, are weighed down by the need to feed information and explain; and the narrative is often reduced to causes and effects. But in life there are so many hidden causes and unpredictable effects – so much ambiguity and mystery that it’s hard to convey it as conventional cause and effect drama. It’s better to just show the strong and significant moments in the story and let the audience fill in the gaps with their own imagination and experience of life.

Reading the pressbook, I found myself wishing that at least some of the information therein could have been included in the film. There certainly would be time, since Cold War runs about 80 minutes sans its credits.

Amazon acquired Cold War for North America last year after its premiere at the Berlin Film Festival. It has announced a December 21 limited theatrical release.

Thanks as ever to the tireless staff of the Vancouver International Film Festival, above all Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, Shelly Kraicer, Maggie Lee, and Jenny Lee Craig for their help in our visit.

Snapshots of festival activities are on our Instagram page.

Cold War (2018).