Archive for the 'National cinemas: Iran' Category

Vancouver 2019: Happy endings, art-film style

Tehran: City of Love (2018).

Kristin here:

The Vancouver International Film Festival has several strong threads running through it: world art cinema, documentaries, Canadian cinema, and films about art and artists. Sticking to any one or two of these would make for a rich viewing experience. I gravitate toward the “Panorama” program of mostly fiction films from around the world.

At one of these films, Tehran: City of Love, the Iranian director, Ali Jaberansari, and scriptwriter, Maryam Najafi, were present for a Q&A session. Clearly the audience has been charmed by their tale of three remotely connected characters all seeking love. One questioner asked what the pair’s next project was, which must always be cheering to the filmmakers. Another audience member simply thanked them for the film, saying that after seeing several grim movies, it was a pleasant experience to find one so funny and entertaining.

[Spoilers to come]

Certainly Tehran: City of Love is an entertaining film, but its ending is bittersweet at best. All three protagonists, after brushes with romance, end up alone. All may have learned something along the way, but they are all saddened by their failures. This year I have seen a couple of other films where the happy ending consists mainly of the central character letting go of bitterness and becoming reconciled to his fate. It seems as though grim storylines with unhappy endings are a staple of the festival film, and even comedies often avoid sending their audiences out on an entirely cheery note. Perhaps there is an assumption that an art film that is too entertaining risks not being taken seriously by festival programmers. Luckily, these three were included in the VIFF program.

Tehran: City of Love (2018)

Tehran: City of Love presents three central characters who are looking for love. Each has a problem to overcome. Mina is an overweight receptionist who, apparently resigned to her single status, targets attractive men who visit the cosmetic surgeon. She calls each, speaking seductively and arranging a date. She shows up for the date but does not identify herself, instead watching the man from a nearby restaurant table until he gives up in annoyance and leaves. At a class on the “geometry” of love, she meets a pudgy man who begins a courtship

Hessam is a body-builder with three championship titles in his past, now working as a trainer. He receives a part in a dubious film project and at the same time begins training an attractive young man who aspires to a championship. Hessam’s attraction to his trainee is subtly conveyed (above), and the young man seems friendly and seems possibly to reciprocate Hessam’s feelings.

Vahid, a talented mosque singer specializing in funerals, is dumped by his fiancée. A friend counsels him to become more lively and cheerful by singing at weddings. Vahid quickly makes the transition, which seems to improve his mood. He becomes friends with Niloufar, a female wedding photographer, who likes him but–as we know and Vahid doesn’t–she is awaiting a visa to allow her to emigrate to Australia.

Disappointments result. Mina’s beau is a married man in the lengthy process of divorcing his wife. The young man notices Hessam’s interest in him and switches to a new trainer. Niloufar reveals her imminent departure from Iran.

Tehran: City of Love is an impressive film for a second feature. The script by Jaberansari and Najafi weave the three stories together skillfully, keeping each story and the thematic connections among them perfectly clear. One might expect the three protagonists’ plotlines to come together. Hessam does at once point come to Mina’s office to get Botox treatments (presumably motivated by the film he is supposed to act in or to make himself more attractive to the young trainee), but nothing comes of that. Mina is close friends with Niloufar, but although the two talk about Vahid casually, Mina never meets him. The three characters are by chance in the same space by the final shot, but they remain unaware of each other. The title, unless we take it to be ironic, suggests that each may try again to find a partner, but the ending only hints that each has at least gained something from his or her brush with love.

It is also beautifully shot in widescreen, often employing what David has termed the planimetric shot, with the camera axis perpendicular to the background (see above and top). During the Q&A Jaberansari mentioned some of his film influences. (He was trained abroad in Vancouver and in London, where he now lives.) These included Roy Andersson, Elia Sulieman, Jim Jarmusch, Aki Kaurismäki, Jacques Tati, Fassbender, and Buster Keaton. Although Tehran: City of Love does not resemble any of these directors’ films closely–there are few long-take scenes or physical comedy played out in long shots–the list makes sense, mostly in the tone of the film.

Jaberansari and Najafi provided some helpful cultural context. They shot the film with official permission and also have permission to release the film in Iran, though no date for that has yet been determined. Despite the implied homosexuality of one character, only two minutes of cuts were required for the domestic distribution permit.

The emphasis on body-building, both in the gym and the scenes of men exercising in a mosque, reflects the fact that without bars, night-clubs, and other forbidden gathering-places, gyms and body-building are one milieu in which men can come together, including gay men.

At one point Vahid is arrested while singing at a “private” wedding. The phrase seems harmless enough, but private weddings often include men and women mixing in ways forbidden in the public weddings at which Vahid had previously performed.

Australia, they note, is the new destination of choice for Iranians seeking to move abroad, replacing Canada to some extent.

Sometimes Always Never (2018)

This film is largely a vehicle for Bill Nighy, contributing a mix of comically self-centeredness and pathos as Alan, a retired tailor. Years before his elder son Michael walked out of the house during a game of Scrabble and has never been heard from again. Alan has since been looking for him, neglecting his younger son, Peter, as well as his daughter-in-law and grandson.

Scrabble looms large in the plot. In one extended series of scenes, Alan and Peter show up in a small town to view the body of a young man who might be the missing son. During an evening in a bed-and-breakfast, Alan hustles the husband of a couple staying there, pretending to be an ordinary Scrabble player and winning £200 off the henpecked husband (above). Only later is it revealed that they, too, are there to examine the same corpse. Alan goes first emerges tactlessly and cheerily saying that the body is not Michael, despite the fact that the couple is about to perform the same grim task.

First-time feature director Carl Hunter adopts a playful style which at times resembles that of Wes Anderson. As with Tehran: City of Love, there are the planimetric shots(on a beach in Crosby otherwise populated by Anthony Gomley’s life-size statues, at bottom, and above, in the bed-and-breakfast Scrabble game). The characters drive in cars with blatantly obvious back-projected motion, and there are black-and-white inserts and brief animations. All these stylistic touches help lighten the tone of the underlying misery of the characters, though they also stand apart from the fairly straightforward presentation of most of the scenes.

The growing closeness between Alan and his shy grandson helps add a positive side to Alan and prepares the way for the inevitable outcome, as he learns to value the son he has over the one who clearly will never return.

A White, White Day (2019)

Most small producing countries have managed throughout the history of cinema to make films, and Iceland has been no exception. It was not until the 1990s that its films started attracting attention on the festival and awards circuit, but only now and then. Even today the local feature production hovers around only four a year. Still, we have learned to consider Icelandic films must-sees when they show up on festival programs.

Benedikt Erlingsson’s films have shown here in Vancouver, and we reported on Of Horses and Men in 2014 and Woman at War last year.

This year the contribution from Iceland is Hlynur Pálmason’s A White, White Day, his second feature. (His previous feature, Winter Brothers, played at our 2018 Wisconsin Film Festival, but we were in the process of buying a new house and missed it.)

“A white, white day” is a local phrase describing weather conditions that cause land and sky to become indistinguishable. It’s a perfect metaphor for confusion, for loss of bearings. We see it both literally and figuratively in the film. The protagonist, Igimundur, is a middle-aged policeman on leave for depression following a car accident that killed his wife. The film opens with the accident, although we don’t yet know who the driver is, occurring on a white, white day.

There follows a mesmerizing series of shots from the same vantagepoint, showing a lengthy series of shots of a pair of small buildings in a rural landscape, including these two.

All atmospheres and times of day area shown, from the light fog of the top shot to the heavier fog of the lower one, from bright sunny days to dark nights. Horses wander through in some, cars drive up in others, and gradually the ramshackle yard and structures become a home. We first glimpse Igimundur in the lower shot, though we don’t yet know who he is. The renovation of the buildings to make a home for his daughter and son-in-law, along with his beloved granddaughter Salka. Where Igimundur will go once they move in is never mentioned. Clearly the project is his way of coping with his grief, while he increasingly scorns the lack of help he receives from his psychologist.

Soon, however, he comes to believe that his wife had been having an affair, and he becomes increasingly abusive and violent, even toward his police colleagues and in front of Salka. The happy ending, which seems a trifle abrupt, sees him finally reconciling himself to the past and regaining his loving memories of his wife.

A White, White Day depends less on humor than the other two films, despite its occasional comic touches. Instead it is an absorbing family melodrama that most audiences would find entertaining.

For a useful brief history of Icelandic cinema, see here. So far it doesn’t include Palmason, but I expect he will soon be added.

We thank Alan Franey, PoChu Auyeung, Jenny Lee Craig, Mikaela Joy Asfour, and their colleagues at VIFF for all their kind assistance. Thanks as well to Bob Davis, Shelly Kraicer, Maggie Lee, and Tom Charity for invigorating conversations about movies.

Sometimes Always Never (2018).

Venice 2018: The Middle East

As I Lay Dying (2018)

Kristin here:

As Variety‘s Nick Vivarelli pointed out earlier this week, Arab cinema is well represented here at the Venice International Film Festival. The same is true of Middle Eastern films in general. I couldn’t catch all them, but here are some thoughts on those I saw.

The Palestine question as sit-com

Comedies about ethnic hostility in Ramallah are understandably rare. For a long time the only one I knew of was Elia Sulieman’s masterly Divine Intervention (2002), though there may be others. Now we have Sameh Zoabi’s Tel Aviv on Fire, a real crowd-pleaser playing in the competitive Horizons section of the festival, a section designed to showcase promising early-career filmmakers.

Despite the title, which might suggest a grim tale of conflict, perhaps involving terrorism, the film is very funny. “Tel Aviv Is Burning” is the name of a daily melodramatic TV series made in Ramallah by a group of Palestinians but enjoyedby both Jewish Israelis and Palestinians–mostly women. (All citizens of Israel are considered Israeli. This means that, ironically, the Israeli Film Fund is required to provide funding to Palestinian projects; it is one of Tel Aviv on Fire’s backers.) The story arc is at a point where a Palestinian woman is assigned to disguise herself as Jewish in order to seduce an important Israeli general and get a key to a hiding place for military plans.

Salam, the protagonist (played by Kais Nashif, who won the best actor award in the Horizons competition), is the lowly nephew of the show’s producer, fetching coffee and helping keep the Hebrew dialogue authentic. Suggesting a bit of action one day, he is promoted to be a writer, despite having no experience or skill. When Saam is stopped for no reason at an Israeli checkpoint (above), he meets a general, Assi. Salam boasts about being a writer on the show, which happens to be a favorite of Assi’s wife. Hoping to impressive his shrewish spouse, Assi puts pressure on Salam to slant the story: the heroine should fall in love with and marry the Israeli general she has seduced. Eager to get away, Salam agrees.

The rest of the story is a cleverly scripted series of twists as Assi makes further demands to make the Israeli general more sympathetic and Salam tries to foist these on his reluctant collaborators. One might argue that the final surprise revelation does in fact make the film lean toward the Israeli side. On the whole, though, Zoabi’s film balances the two factions and manages to convey that the ongoing conflict is absurd, given the many similarities between the two main characters and the universal appeal of “Tel Aviv on Fire” across Israel’s population.

One strength of the film is the stylistic contrast between the main story’s conventional lighting and location shooting and the tacky sets, garish colors, improbable dialogue, and over-the-top performances in the scenes from the TV series.

A microcosm of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict

Veteran Israeli filmmaker Amos Gitai contributed a program of two films to the festival. The first was a short, A Letter to a Friend in Gaza, the second the feature A Tramway in Jerusalem, both playing Out of Competition.

A Letter to a Friend in Gaza is a evocation of the bitter disagreement between people, even within families, using a text by Albert Camus to sum up the issues in poetic form. I suspect one would need to know a great deal about the Palestinian occupation to fully grasp this oblique work.

The issues are readily apparent, however, in A Tramway in Jerusalem. Set aboard a tram, with occasional shots on platforms where it stops, the action consists of a series of short scenes between a wide variety of citizens. The episodes are separated by titles announcing the time of day, but these skip about, suggesting that this is not a day-in-the-life-of a tram tale but a series of random encounters. The vignettes are not connected, though a few characters recur, most notably a French tourist introducing his beloved Jerusalem to his son. The participants in these short scenes are played by actors, though the only one likely to be recognizable to a broad audience is Mathieu Amalric as the tourist (above).

The scenes suggest a range of possibilities for successful or failed coexistence. For no reason but prejudice a woman accuses a Palestinian man standing next to her of sexual harrassment, and the guards on board immediately throw him to the floor. Two sophisticated young women, one Palestinian with a Dutch passport, the other an Israeli, are standing side by side. They chat casually, clearly very much alike, and when, again for no reason, an aggressive guard demands the Palestian’s passport, the Israeli stands up for her. In an overly long episode, a Catholic priest soliloquizes about the death of the three religions struggling for dominance in their mutually sacred city. The French tourist, determined to idealize Jerusalem, fails to realize that a local couple is poking fun at him by enthusiastically advocating the violent suppression of Palestinians.

The Iranian search narrative endures

Not all Iranian films involve searches by any means, and yet searches, whether they involve a journey or not, provide the structure of many familiar classics like Where Is My Friend’s Home? and The Mirror. By chance, two films at this year’s festival show searches involving in one the beginning of life and in the other its end.

Mostafa Sayari’s first feature, As I Lay Dying (Hamchenan ke Mimordam), also played in the Horizons competition. It begins after the death of an old man. One of his sons, Majid, who has cared for him recently, admits to the doctor that he had provided the sleeping pills that apparently killed his father, but the doctor agrees not to mention this on the death certificate. A hint that the time of death is not known provides the first clue in a subtle mystery. Further clues surface in the course of a psychological drama among the four siblings who assemble to drive their father’s body to a small, distant village for burial.

As the journey continues and quarrels develop, the siblings question Majid as to why he chose this remote village for the burial. The length of time that the father has been dead emerges further as a significant factor. By the end, the answers to the three siblings’ questions becomes apparent to them.

Speaking with others who had seen the film, I heard complaints that the story was difficult to understand. I think that As I Lay Dying is something of a mystery story, without being strongly signaled as such, and that sufficient clues are dropped along the way that the viewer should be able to understand the situation by the time the story ends, rather abruptly and perhaps seeming not to offer a resolution. (It would help to know that Muslim burials are supposed to take place as soon as possible, ideally within 24 hours.) Certainly nothing is made explicit at the end, though again, an attentive viewer should figure out the implied outcome.

The film takes place largely on a bleak desert road, including some beautiful widescreen compositions reminiscent of Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s work in Once Upon a Time in Anatolia, perhaps coincidentally also involving a search in the desert, in that case for an already buried body. (See top.)

The search narrative goes back at least as early as Ebrahim Golestan’s Brick and Mirror (Khesht O Ayeneh, made 1963-64, released 1966). It was one of the historically important films shown in the “Venice Classics” series of recent restorations.

Brick and Mirror is generally considered the first Iranian art film, having come out three years before Dariush Mehrjui’s classic, The Cow (1969). Golestan was an experienced filmmaker, mostly of documentaries, but Brick and Mirror was his first fiction feature.

The title has nothing to do with the subject matter of the film but is more evocative, being, as Golestan has revealed, derived from a Thirteenth Century Persian poem: “What the Youth sees in the mirror, the Aged sees in the raw brick.” The word “brick” here does not refer to the familiar fired brick, which costs money to buy, but to the simple mud brick, widely used by the poor across the Middle East, since anyone with access to silt and a simple wooden frame can make them.

The story begins one night as the taxi-driver protagonist, Hashem, discovers that a woman passenger has left a baby in the back seat of his car. In a famous scene, he wanders the desolate neighborhood searching for her (see below). Eventually his girlfriend joins him in his apartment to help care for the child. The experience leads her to hope that they can marry and raise the child themselves, turning their so-far aimless affair into a family. The quest to find a practical, humane way to dispose of the baby–or not–takes up the rest of the film. Near the end, a lengthy scene of babies and young children in an orphanage reflects Golestan’s documentary experience.

The new print recalls the rough, often dark look of black-and-white widescreen films of the 1960s, especially those of the French New Wave. Golestan’s story of fruitless wandering and unresolved relationships has been compared by some critics to the films of Antonioni, and it seems clear that Antonioni’s work and other European films of the 1950s and 1960s influenced him. There are, however, distinct differences. While Antonioni deals with the psychology of bourgeois characters (except in Il Grido), the couple in Brick and Mirror are working-class, and their problems are caused as much by their social situation as by any general ennui.

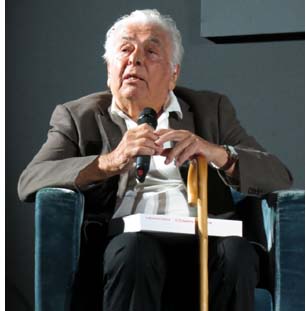

Remarkably, Golestan was present to introduce the film. At 97, he remains articulate and charming. He primarily sketched out his early career and the inspirations for Brick and Mirror. The most interesting point concerned a startling moment during the early scene of Hashem searching the dark neighborhood for the elusive mother of the baby. A close composition of him at the top of a long stairway suddenly leads to a quick series of axial cuts, each shifting further back until he is seen in extreme long shot. The moment reveals the empty staircase and emphasizes the hopelessness of the chase. Golestan emphasized jump-cut quality of the passage and mentioned that he had not seen Breathless at the time Perhaps the moment harks back further, to the axial cuts of static figures used in Soviet films of the 1920s and the work of Kurosawa.

Previously only incomplete, worn prints of Brick and Mirror were available, and then only in rare screenings. The importance of this restoration was emphasized by the festival’s publication of a short book, Brick and Mirror, which brings together a number of essays by Golestan and others. It also describes the restoration, done with the director’s cooperation and accomplished at the L’Immagine Ritrovata Laboratory in Bologna. My thanks to Ehsan Khoshbakht for providing me with a copy and more generally for his important work in reviving Iran’s film heritage, including programing the Iranian season at Bologna that I reported on in 2015.

As ever, thanks to Paolo Baratta, Alberto Barbera, Peter Cowie, Michela Lazzarin, and all their colleagues for their warm welcome to this year’s Biennale.

For more photos from this years Mostra, see our Instagram page.

[September 12: Thanks to Steve Elsworth for some corrections.]

Brick and Mirror (1966).

Barely moving pictures: Kiarostami’s 24 FRAMES

24 Frames (2017).

DB here:

It might seem an act of vandalism. To overwrite one of the world’s most famous paintings, the elder Pieter Bruegel’s Hunters in the Snow, with digital effects could be condemned as vulgar at best and scandalous at worst. In the lower left, we see a dog pissing on a tree. Yet no one ever accused the late Abbas Kiarostami of bad taste. Of weirdness, yes: His Lumière tribute (1995) consisted of a close-up of a frying egg.

Eggs aside, Kiarostami’s experiments mostly have a stubborn stringency. He made a film wholly out of reaction shots, and another out of static takes of landscapes. Yet neither was an arid exercise. Shirin (2008) yielded poignancy as it let us study women responding to a romantic spectacle (film? theatre piece?). The minimalist Five Dedicated to Ozu (2003) was at once meditative and sensuous, speckled with moments of relaxed humor (the parade of the ducks) and building to a curious suspense, as we stare at brackish water trembling in a downpour.

So when the first segment of Kiarostami’s 24 Frames (2017) decorates Bruegel’s masterwork, we ought to expect that something’s up. The explanation offered in the film’s prologue is that the filmmaker is curious about what happens around the instant portrayed in the image.

For 24 Frames I started with famous paintings but then switched to photos I had taken through the years. I included about four and a half minutes of what I imagined might have taken place before or after each image that I had captured.

This declaration, apparently opposed to Cartier-Bresson’s doctrine of the “decisive moment,” leaves creative wiggle room. Kiarostami and his colleagues used digital manipulation to alter his stills, adding layers of figures and movements.

But how do we determine the punctual instant of each of the twenty-four shots? What’s the before or after? Many shots contain several moments of pause that might be the original frozen moment, but Kiarostami doesn’t give them special emphasis. After the Bruegel, we get twenty-three gradually changing natural scenes, nearly all mini-narratives based on stasis, rhythmic cycles, hesitations, and bursts of action. Five showed Kiarostami venturing into the territory of Structural Film, and especially the open-air tendency mastered by James Benning. With 24 Frames we get that monumental impulse recast by photorealistic animation: landscapes teased into little stories by the miracle of rendering, mo-cap, and drag-and-drop.

The birds and the beasts were there

The Bruegel is defaced for a reason. The original painting lays out strategies that the following sequences will pursue. Human bodies will play a subsidiary role; they appear in only two sequences, and, like Bruegel’s hunters, they are mostly turned away from us. We’ll also see snow, birds, dogs, trees, a scraggly bush, and water (the frozen pond). Just as important, Bruegel’s composition warns us how to watch. He draws our eye into the distance, and there lots of tiny figures will grace the scenes ahead.

Kiarostami’s decorations insert more previews. He introduces a herd of cows, blatantly fake falling snow, smoke that prepares us for mist and cloud formations. Dogs and birds are set into motion and given sounds; we’ll spend a lot of time tracking these vagrant creatures, and their cries will help us navigate the frames. The revised painting becomes a matrix of pictorial and auditory motifs that will be combined and varied throughout the movie.

Eventually the landscapes will include a wider menagerie, including lions and horses. At one point a duck seems to size up a possible mate, who approaches from the distance.

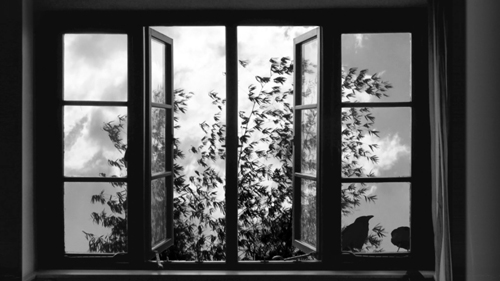

As here, most shots are centered, with the primary action taking place in the central third and sometimes accentuated by an aperture. The apertures often get geometrical. After several open landscape shots, the sixth sequence introduces a major compositional formula–the grid, typically a window, that will striate and cross-hatch our view. It yields a sort of Advent-calendar effect, as we follow birds or beasts hopping from one cell to another.

More variation: Most of the shots are planimetric. The camera is fixed at right angles to a background plane, and figures move horizontally. As the film goes along, though, an oblique angle may show up, as with the duck courtship. Kiarostami applied planimetric framing brilliantly in Through the Olive Trees (1994), but there too it interacted dynamically with less rigid compositions.

Maybe this is Kiarostami’s real Lumière homage. As in the earliest staged films, the single shot is given a simple arc. Figures arrive in the frame, do something, then depart. But sound is tremendously important too. Quiet activity is interrupted by brusque action–too often, a gunshot. More than you might expect, violence provides a spike of action before calm returns.

What holds these crisp, gorgeous shots together? Pairings, for one thing. The creatures we see often become couples. Lions mate, birds scrap with each other, ducks flirt, deer double up, and one gull mourns a fallen companion. Yes, I’m indulging in anthropomorphism. This movie firmly encourages you to try mind-reading Nature’s kingdom.

There’s a trace of surrealism. Some dreamlike images, impossibly hard-edged, are reminiscent of Rousseau. Sheep in a snowstorm huddle while a dog stares out at us and a wolf prowls in the distance. You might think of Paul Delvaux when you see a balustrade that has been built athwart rolling surf, as gulls squat placidly on the poles beyond.

Not least, I think, Kiarostami is responding to one problem of digital cinema–the way that a fixed digital shot makes certain portions of the frame go dead. Photographic film keeps the whole frame nervous, thanks to its teeming granular structure, but image compression simply reiterates “unchanging” information until something moves. When an area doesn’t harbor motion, it looks like a slice of stillness.

Kiarostami exploits this feature of the medium. Again and again, his image seems preternaturally frozen, a nature morte, before it twitches back to life. The effect, to recall his before-and-after idea, is of a still image reanimated. An inert animal seems dead to the world before we detect a breath or a shift of position. The most striking example seems to me the soft silhouette of a bird, a mere lump for seconds on end.

Rudolf Arnheim would have loved the fluid play of Gestalts that this simple composition arouses.

To show you more would spoil the pleasures of this delightful, melancholic, rapturous film. Let’s just say that it ends with a human figure slumped over and turned from us while the wind shakes trees outside a window. Warmth and drowsiness inside, a mild tempest outdoors. But in that same shot, a radiant human face, brought to slow-motion life, turns to us before it surrenders to a kiss. The fact that the face belongs to Teresa Wright, in one of the greatest films of the 1940s, ends Kiarostami’s career on a note of gentle jubilation.

Thanks to Brian Belovarac of Janus Films for help with this entry. Thanks as well to Jim Healy, Mike King, and Ben Reiser of the Wisconsin Cinematheque.

24 Frames is being circulated to theatres and museums; please try to see it on the big screen, where all the little details can pop out at you. Eventually, it will show up on disc and FilmStruck‘s Criterion Channel.

For background on the making of the film, see the Janus press page. Imogen Sara Smith offers a sensitive appreciation in “In Our Time: Abbas Kiarostami’s 24 Frames” on the Film Comment site. For more on Kiarostami, including Certified Copy (2010), see our blog’s tag. I discuss his planimetric approach in Through the Olive Trees in On the History of Film Style, soon to appear on this site in an updated pdf.

24 Frames.

More from VIFF 2016

The Death of Louis XIV (Albert Serra, 2016).

The Vancouver International Film Festival ended yesterday, but the films and the pleasures they yielded linger on. Our first two entries are by Kristin, the last two by David.

Smog over Tehran

Iranian film and television director Behnam Behzadi is not well-known outside his native country. Inversion, which was shown in the Un Certain Regard section of Cannes this year, suggests that he deserves to have more international exposure for his work.

The title refers to the meteorological phenomenon that can cause dense pollution to form at ground level. The film opens with shots of Tehran streets seen dimly through a thick haze. The pollution has a causal role to play, since the heroine’s elderly mother ends up in a hospital as a result of breathing problems. More metaphorically, however, the title refers to a sudden reversal in Niloofar’s situation.

Initially she seems to be in a relatively strong position for a Iranian woman. Still unmarried in her 30s, she runs a small, prosperous garments factory and begins to date an amiable man whom she clearly likes. Her mother’s sudden health crisis, however, leads a doctor to insist that she be moved to the healthier northern part of the country, where Niloofar’s sister and brother-in-law happen to own a small villa. Niloofar, with no spouse or children, is pushed by the couple and her brother into agreeing to go along and take care of her mother. She hopes to keep the factory going, but the brother selfishly rents out the premises to pay off his own debts. Niloofar resists going with her mother, but as her siblings ignore her wishes and she discovers that the man she may be considering marrying has kept an unpleasant secret from her, she realizes how little power she has over her own life.

As in Farhadi’s films, a seemingly ordinary situation suddenly deteriorates from a simple cause. But Farhadi tends to gain complexity by avoiding making his characters into villains. In his films, as in Renoir’s, “everyone has his reasons.” In Inversion, however, the brother is straightforwardly in the wrong, refusing to consider Niloofar’s desires and even threatening her with violence during one argument. Overall the film is entertaining, with Niloofar an engaging figure who gives an insight into the situation of women in contemporary Iran.

Mistakes were made

Asghar Farhadi is best known for A Separation (2011), the first Iranian film to win an Oscar for best foreign-language film. His earlier masterpieces, About Elly (2009) and my own favorite, Fireworks Wednesday (2006), are slowly coming to be known in the West, largely via home video. After the slightly disappointing The Past (2013), Farhadi is back on track with The Salesman.

The film opens with a tense, dramatic scene in which a Tehran apartment building threatens to collapse and its inhabitants frantically struggle to evacuate. The result is that the central characters, Emad and his wife Rana, must quickly find a temporary apartment (see bottom) while they also prepare to star in a production of Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman.

They seem to be coping until Rana mistakenly opens the door of their new apartment, assuming that her husband has come home. The shot holds on the door, standing ajar, as Rana moves off to take a shower and the scene ends. Later we learn that an unknown assailant has entered the apartment. Whether he raped Rana or simply startled her so that she fell and cut herself on broken glass is never revealed, but she is traumatized and unable to proceed, either with her everyday life or her role as Linda Loman in the play. Emad tries to be supportive, but he becomes obsessed with tracking down the intruder.

The mystery gradually unravels as the shady background of the apartment’s former tenant emerges, and revelation of the identity of the intruder undermines the question of revenge. As in Farhadi’s other films, characters’ mistakes, honest or otherwise, compound each other. Ultimately, absolute blame is hard to assign.

The Salesman won two prizes at Cannes: best screenplay for Farhadi and best actor for Shahab Hosseini as Emad. Amazon Studios and Cohen Media will release it in the US on 9 December.

The King is (nearly) dead

Early on in Roberto Rossellini’s Taking of Power by Louis XIV (1966), we find Cardinal Mazarin on his deathbed. Mazarin’s doctors decide to bleed him; a priest advises him on the disposal of his wealth; finance minister Colbert briefs him on intrigues at the king’s court. The shots are lengthy, following the men around the chamber.

This remarkably deliberate sequence was considered quite striking at the time. In a story centered on Louis XIV, Rossellini devotes thirteen minutes to Mazarin. His impending death creates exposition about the ensuing power struggles and initiates a somber pace rather different from that of the standard historical film. The scene also reminds us that historical events have a tangibly material side, as when doctors confer gravely over the stools in His Eminence’s chamber pot.

Rossellini, who’s interested in the tactics by which Louis tames the nobility, doesn’t show us the King’s final hours. That morbid task is taken up by Albert Serra’s The Death of Louis XIV. Unlike Rossellini’s film, which is filmed in radiant high-key and shows sumptuous detail of fabrics and flooring, Serra’s treatment relies on chiaroscuro, with shadow areas broken by trembling candlelight. And while Rossellini’s PanCinor lens swivels and zooms around these apartments, Serra cuts among close views of faces, hands, and a steadily blackening gangrenous royal foot.

In the process Serra expands the physicality of the Mazarin sequence to the length of an entire film. Louis seems to linger for days, but we’re given no distinct sense of how much time passes; in only two shots do we glimpse the outdoors, in bleary light that might be dawn, drab afternoon, or dusk. The time is filled out by court rituals, such as the King’s doffing his hat to his entourage, and by the steady decline of his powers. He can’t swallow food and can barely take water or wine. Through it all, Louis feebly issues his final orders about matters of state and the disposition of his body. A long scene of the last rites is punctuated by a barely discernible fart. This is a movie centrally about a degenerating body.

Even more than Rossellini did, Serra probes the shaky state of medical science of the time. (Louis died in 1715, just as the Enlightenment was beginning.) When Louis’s leg contracts gangrene, the learned doctors debate whether to amputate it. A quack shows up with an elixir made of bull sperm and other recherché ingredients. At the end, the principal physician takes the blame for the king’s death and makes a remarkable apology directly to the camera. Before that, though, Serra has given us a three-minute shot of His Highness reproachfully staring at us (up top) while we hear a Kyrie Eleison somewhere offscreen. Another echo of film history: Louis is played by Jean-Pierre Léaud, who looked out apprehensively at us many years ago, in the seashore ending of The 400 Blows. It’s glib to say that cinema films death at work, but here the cliché gains some meaning.

Master of the weepie

Is any filmmaker more unfairly taken for granted than Pedro Almodóvar? For over thirty years, he has created sparkling, handsome entertainments that combine cinematic intelligence with outrageous eroticism and insidious emotional punch. His films revel in plot complications and edgy humor. Along the way he effortlessly deploys the techniques that make modern cinema modern, from flashbacks and voice-overs to subjective sequences and abrupt replays that fill in gaps.

He makes it all look easy, and gorgeous. After the drab grays and browns of Hollywood fare, what a pleasure to see a film packed with saturated primaries and bold designs. He proves that you can go as dark as you like in plotting and still make things look delightful.

His characters are clothes horses, I grant you, but not the least of his debts to Old Hollywood is the belief that we want to see presentable people in pretty costumes and settings. The world is ugly enough, he seems to say; why add to it? Seeing The Girl on the Train reminded me how glum American movies are determined to look. An Almodóvar apple looks good enough to eat, and a housekeeper’s roseate apron seems the height of chic. In this world, even refrigerator magnets evoke a Calder mobile.

These elegantly voluptuous tales make unabashed appeal to Hollywood genres: the screwball comedy (Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown, I’m So Excited), the illicit romance (Law of Desire, The Flower of My Secret), the twisty thriller (Live Flesh, The Skin I Live In), even the ghost story (Volver), and above all the melodrama—medical (Talk to Her) and maternal (High Heels, All about My Mother). He rolls Lubitsch, Sirk, and Siodmak into a nifty package, tied up with a ribbon bow of pansexuality.

Julieta (from which all my images come) revisits the maternal melodrama, specifically the mother-daughter nexus. Our heroine, beginning as a spiky-haired classics teacher, seems to have an idyllic life married to a fisherman, but soon infidelity, misunderstandings, and a tempestuous storm shatter it. All the paraphernalia of melodrama—raging seas, unhappy coincidences, ingratitude, and dark secrets—threaten Julieta’s efforts to save her marriage and protect her daughter. Told in flashbacks, chiefly through a letter she writes her daughter Antia, the two major phases of Julieta’s life get intercut in surprising and gratifying ways. With his usual cleverness, Almódovar has Julieta played by two female performers, with a surprise match-on-action linking them in one scene. A beautiful purple towel helps, as the poster sneakily suggests.

Julieta (from which all my images come) revisits the maternal melodrama, specifically the mother-daughter nexus. Our heroine, beginning as a spiky-haired classics teacher, seems to have an idyllic life married to a fisherman, but soon infidelity, misunderstandings, and a tempestuous storm shatter it. All the paraphernalia of melodrama—raging seas, unhappy coincidences, ingratitude, and dark secrets—threaten Julieta’s efforts to save her marriage and protect her daughter. Told in flashbacks, chiefly through a letter she writes her daughter Antia, the two major phases of Julieta’s life get intercut in surprising and gratifying ways. With his usual cleverness, Almódovar has Julieta played by two female performers, with a surprise match-on-action linking them in one scene. A beautiful purple towel helps, as the poster sneakily suggests.

It’s all about guilt, passed from husband to wife and mistress and then to daughter and even daughter’s pal, with the obligatory recriminations and tearful confessions. The plot is continually surprising, yet every scene snicks into place. Neat parallels among couples develop quietly, and tiny hints planted in the beginning pay off. As usual with Almodóvar, the opening credits guarantee that you’re in assured hands. They also tease us with motifs. Here the film’s dual structure (two phases of life, two actresses) is suggested through lemon-yellow letters sliding into alignment.

The two women on my left started crying halfway through the movie. I tell you, this director is a credit to the species.

Special thanks to Michael Barker and Greg Compton of Sony Pictures Classics. Sony will release Julieta in the US on 21 December.

We have earlier entries on Farhadi’s About Elly, on A Separation, and on The Past. We discuss Serra’s ingratiating Birdsong here, and Almodóvar’s cunning The Skin I Live In here.

The Salesman.