Archive for the 'National cinemas: Iran' Category

Arthouse suspense, in big and small doses

Le Quattro Volte.

DB here:

As happened last year, I had to flee Hong Kong for medical reasons. Beset by a wracking cough, I took off three days early and upon returning to Madison wound up in hospital. Current diagnosis: pneumonia. Duration of stay: six nights and counting. A drag. But I’m lucky: no disorderly orderlies, no homicidal doctors injecting me with mind-control drugs (“You will watch only Brett Ratner films for the rest of your life. Sleep, sleep…”). I’m taken care of by expert, calm, and good-natured people. Expect no less from the best city for men’s health and care.

So I’ve been tardy in writing this final HK blog. I just wanted to talk about two extraordinary films I saw in my final days and bring up a scrap of news for followers of Chinese film.

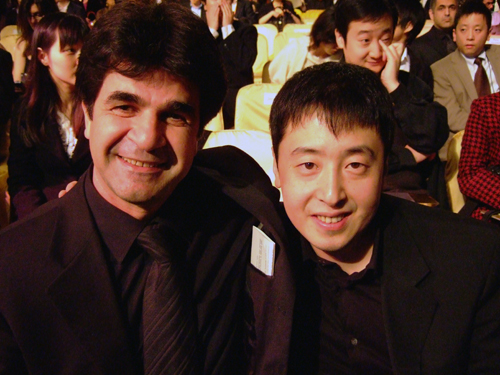

First, the news. Liu Jiayin, of Oxhide fame, was in Hong Kong briefly to accept an Asian Film Financing Forum award for her screenplay Clean and Bright. The other winner was Li Ruijun, for his project Where Is My Home? Liu was about to visit the US for screenings at Redcat, under the sponsorship of the tireless Bérénice Reynaud, and at Cinema Pacific in Portland. I had a chance to talk briefly with her just before she departed.

First, the news. Liu Jiayin, of Oxhide fame, was in Hong Kong briefly to accept an Asian Film Financing Forum award for her screenplay Clean and Bright. The other winner was Li Ruijun, for his project Where Is My Home? Liu was about to visit the US for screenings at Redcat, under the sponsorship of the tireless Bérénice Reynaud, and at Cinema Pacific in Portland. I had a chance to talk briefly with her just before she departed.

Regular readers of this blog know my admiration for Liu’s two Oxhide films. The good news is that she is at work on Oxhide III. She wouldn’t say much about it, except that she is still reworking the script, but it sounded quite far along. In addition, she hopes to shoot Clean and Bright, a more orthodox film about a family, fairly soon as well. Oxhide IV is also planned, with the series running up to perhaps eight installments.

For more on Oxhide, including purchase information for the DVD, check Kevin Lee’s dGenerate Films website.

Leaving us hanging

Too often we think of suspense as specific to certain genres, but it’s actually a fundamental resource of all storytelling. Creating expectations about an upcoming event, sharpening them, and delaying their fulfillment–all these strategies are basic, I think, to narrative experience in general. Although some plots emphasize suspense more than others, even most “character-centered” tales wouldn’t engage us without a dose of it.

True, sometimes there’s a sort of bait-and-switch, as when suspense is conjured up but eventually dissolved. Sooner or later we realize Godot isn’t going to show up, or that Anna in L’Avventura is likely not to be found. In those cases, suspense has led us to another terrain, usually thematic, in which we’re invited to consider something more significant than learning the outcome of events. (Sometimes, though, snuffing out suspense is just a sign of slack, or Slacker, storytelling.)

Suspense is usually associated with popular plotting, so many people expect Serious Films to be lacking in suspense. Which makes it all the more interesting that Iran, one of the most-favored nations on the festival circuit, has made something of a specialty of suspenseful art movies.

We don’t recognize often enough that Kiarostami’s early films are often structured as suspenseful quests, from the boy’s attempt to return his schoolmate’s notebook in Where Is the Friend’s Home? to the final shot of Through the Olive Trees. His scripts for other directors convey this quality even more clearly. The Key is almost Griffithian in showing how a four-year-old boy struggles to rescue his younger brother when they’re locked in a kitchen with a gas leak. The Journey (Safar) is positively Ruth Rendellian: A headstrong middle-class father leaving Tehran with his family forces another car off the road and flees the scene. Instead of resting at a summer retreat, he returns obsessively to the place of the accident to check the progress of the investigation: Will he give himself away? And it isn’t just Kiarostami. Look at the suspense structure in Makhmalbaf’s Moment of Innocence, or Reza Mir-Karimi’s The Child and the Soldier, or Panahi’s The Circle.

What gives Iranian suspense films their weight is partly the fact that they don’t rely so much on the old standbys (chases, stalkings, cliffhanging rescues) but rather on psychological maneuvers, carried out largely through dialogue. Characters in these movies tend to talk a lot, pushing their concerns forward with a stubbornness that we seldom see in other national cinemas. People stick up for themselves, and the suspense comes from a clash of testimonies, pleas, and self-justifications. But it also comes from a moral dimension. My earlier examples depend on our assessing what we ought to happen (the hero of the Journey should be punished) versus what we might want to happen (he should escape). Add a dash of mystery, as we have in Through the Olive Trees (what is Tehereh thinking?) and A Taste of Cherry (what is the job Mr. Badi is hiring for?), and you have artistically ambitious filmmaking that exploits some very traditional resources of the art form.

These resources were on display in Asgar Farhadi’s earlier About Elly, which I praised in these pages two years ago. Nader and Simin, A Separation has a comparable power to seize and hold our interest. A wife fails to get a divorce and leaves the household, which includes not only her husband Nader but his Alzheimer’s-addled father and their daughter Termeh. Without Simin to care for his father, Nader hires Razieh, a working-class woman who must bring her little girl with her. Soon the job overwhelms Razieh and, for reasons not disclosed till later, she goes missing. Nader and Termeh find the old man tied to the bed, unconscious.

For this early stretch of the film, the helper Razieh trembles on the verge of hysteria, and only later do we learn why. When she returns to the apartment, she confronts Nader’s wrath, which leads to yet another turning point, but one whose significance we realize only later. To complicate matters, Razieh’s hot-headed husband becomes furious with everyone. As in About Elly, a great deal turns on what characters know at one precise moment, and our memory of when they learned something can be as elusive as theirs. And as in Henry James’ novels, much of the action is registered through the reactions of onlookers, notably the pensive daughter Termeh (below), who turns out in the final scene to be as important as any other figure in the film.

The suspense builds on many levels: the progress of the divorce, the decline of the old man, the court case that involves Razieh’s place in the household (did she steal money?), and above all the responsibility for a death. Some of these lines of action are shown resolved; a crucial one remains suspended. And that does, as often happens, oblige us to think more broadly about the film’s treatment of parent/ child relationships. We are left with an exceptionally rich film, one reflecting on class differences, religious ones, and the effects of adult problems on the children around them. Suspense not only feeds our hunger for story; it can also tease us to moral reflection, and Nader and Simin does just that.

No suspense?

How much can you purge suspense from a movie? And if you play it down, what do you put in its place to hold our interest?

One answer to these questions comes in Michelangelo Frammartino’s Le Quattro Volte. It is one of those sedate observational pieces that covers a year in the life of a village, with not much discernible dialogue but lots of lovely landscape shots. It has a cyclical rather than linear structure, beginning and ending with smoldering wood turned into charcoal–itself a metaphor for the inevitable transmutations that govern plants, animals, and men. We follow an old goatherd who eventually dies; his goats pay homage by climbing precariously to his tiny home and occupying it. A young goat is born soon after the old man’s death. The townsfolk erect an enormous Christmas tree, which at the end of the holiday is chopped down into bits, which will in turn becomes charcoal. If Nader and Simin exists largely in medium-shot, here the extreme long-shot dominates. There are no psychological interactions or dramatic issues of the sort we find in Fahradi’s films. In the rustic spirit of Rouquier’s Farrebique, we get the sheer successiveness of things, the fact that life is one damned, or placid, moment after another.

So suspense can be replaced by sheer consecutiveness, but the task then becomes to make things interesting. Frammartino does so through careful framing, evocative sound, and crisp storytelling technique. The goats pick their way up to the old man’s hillside apartment; they jostle around inside; cut to a shot of the old man’s head as he lies dead; cut to the church, with people filing out as the bell tolls. In addition , you can find suspense at more micro-levels, working not at the level of plot action as a whole but rather within and across particular scenes. After the goatherd’s death, we see another kid born: this is familiar, even clichéd, the rhythm of nature. We follow the kid’s efforts to assimilate to the herd. But as winter comes, the kid strays off, becomes isolated, and ends up lost and shivering. We must assume that he dies. So much for the great cycle of life.

At a still more microscopic level comes the shot that everyone remembers from Le Quattro Volte. It’s so salient that critics who seldom notice imagery can’t help but mention it. I won’t describe it in detail, so as not spoil the surprises, but suffice it to say that it involves a church procession, some intransigent goats, a pickup truck, and a resourceful dog. Reminiscent of Tati or Suleiman, this long shot depends on ratcheting up our expectations about how several converging events might develop, onscreen or off, and then fulfilling those expectations in startling ways. We might call the result spatial suspense: How will this composition-in-time finally resolve itself?

We should, then, never underestimate the power of suspense, even in those films which might seem to forswear it. Melodrama or pastoral, any genre can find a way to excite us by asking what can come next.

Catching up: By leaving Hong Kong early I missed the second screening of The Turin Horse; my first impressions are here. Since I wrote that, I learned that Cinema Scope has published Robert Koehler’s sensitive appreciation of the film and his enlightening interview with the cinematographer Fred Kelemen.

Nader and Sinin, A Separation.

“I don’t hate anybody, not even my interrogators”

Jafar Panahi, May 2010.

DB here:

From Tehran comes the shocking news that Jafar Panahi, one of the finest of Iranian filmmakers, has been sentenced to six years in prison. The sentence also bans him from filmmaking for twenty years, forbids him to leave the country, and forbids him from giving interviews to the press, foreign or domestic. Panahi’s collaborator Muhammad Rasoulof was also sentenced to six years in jail.

This is the next step in a series of confrontations between Panahi and the government. He was earlier arrested for attending the funeral of Neda Agha-Soltan, the young woman shot in the 2009 protests. His passport was later seized. Before his most recent arrest he was forbidden to leave the country to attend the Berlin and Cannes festivals. Between March and May of this year he was in prison, during which he undertook a hunger strike. In May he was released on bail.

Since the mid-1990s Panahi has directed several extraordinary films, all explicitly or tacitly critical of aspects of Iranian society. Like his mentor Abbas Kiarostami, he attracted attention with films centering on children, notably The White Balloon (1995) and The Mirror (1997). The latter is a fine example of how Iranian directors have merged social realism, unexpected character psychology, and experimental storytelling strategies. The first half shows a stubborn little girl trying to get home from school. On a bus, she gets tired of pretending to be in a film and goes off on her own, with her microphone still attached. The crew tries to track her down, and much of the rest of the action takes place on the soundtrack, as we hear her encounters with street life and the crew’s commentary on what they manage to shoot. Sometimes the sound drops out entirely.

The Circle (2000) shifts to the adult world, illuminating critical moments in the lives of several women as they traverse the streets. Crimson Gold (2003), from a script by Kiarostami, shifts from presenting a crime-thriller situation to providing an unusual view of Tehran’s prosperous upper class. Offside (2006) won attention for its exuberant portraitsof women who disguise themselves as men to watch a soccer match. Panahi remarked drily to the court: “The space given to Jafar Panahi’s festival awards in Tehran’s Museum of Cinema is much larger than his cell in prison.”

The charges and the replies

The Mirror.

The oppression of filmmakers isn’t new, of course. Authoritarian political regimes across film history have banned films and punished their creators. In recent times, the Turkish actor-director Yilmaz Güney was imprisoned several times; while incarcerated, he wrote scripts to be filmed by others. After Devils on the Doorstep (2000), Jiang Wen was banned by Chinese authorities from film activities for some years, as was actress Tang Wei for appearing in Lust, Caution (2007).

But Güney was convicted of civil crimes, although of a political nature; his films were not, as I understand it, explicitly part of the charges. And although Jiang and Tang were punished for their film work, that punishment didn’t include jail time.

Panahi is in an unusually vulnerable situation. He is set to be imprisoned for preparing a film.

The official charges are “assembly and colluding with the intention to commit crimes against the country’s national security” and “propaganda against the Islamic Republic.” The authorities charge that he and his colleague Rasoulof were “preparing an anti-government film bearing on the post-electoral events” of June 2009, when thousands of Iranians protested the disputed reelection of President Ahmadinejad. “You are putting me on trial for making a film that at the time of our arrest was only thirty percent shot.” Panahi was shooting his film in his home, and government authorities seized the footage.

Other accusations sought to bolster the case. Panahi’s household, according to the prosecution, held “obscene films.” In his defense statement last month, he replied that these were film classics that have inspired him. He was charged with participating in demonstrations, but he replied that he was there to observe, and this was within his rights. He notes as well that he shot no footage of the demonstrations, acknowledging that filming was forbidden. As you know, on-the-spot reportage leaked out through Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube.

Panahi was accused of making his film without permission, but he responded that there is no legal requirement that a filmmaker obtain permission. He was accused of organizing protests at the opening of the Montreal Film Festival, but there he served simply as the head of the jury. He was charged with giving interviews to foreign media, but he pointed out that there are no laws forbidding someone from being interviewed. He was even accused of not giving scripts to his actors! He explained that he works with non-professional actors, and it’s common for Iranian filmmakers to simply explain what the actor must do and say.

The charges may be simply a pretext for silencing a prominent figure critical of current Iranian society. Panahi’s films do not circulate legally there, and he is widely believed to be in sympathy with liberal forces. The government has sought to eradicate the most visible of these factions, the Green Party. Even Islamic clerics have been swept up in the crackdown. A parallel case to Panahi’s is the attack on Mohammad Taqi Khalaji, a dissident cleric. Last January he was arrested and his computer and papers were seized. He too was incarcerated in Evin prison before being released on bail. Yet he was not formally charged with anything. His personal papers, including his passport, were not returned to him.

You can get some grim satisfaction for knowing that movies still matter in some parts of the world. Films have the power to shock bureaucrats and threaten authoritarian regimes. Instead of being simply “assets” or “content” to be extruded across platforms and shoved through release windows, cinema is in some places taken seriously as political critique.

Panahi’s case, his lawyer asserts, will be appealed.

Out of bounds

Offside.

Lest we Americans savor our superior virtue, consider this: Four months before 9/11, Panahi was traveling between Hong Kong and Argentina and stopped over in New York. He had been told he did not need a transit visa, but he was detained by American authorities at JFK Airport for lacking one. Here is Stephen Teo’s account in Senses of Cinema:

On his way to the Buenos Aires International Festival of Independent Cinema on 15 April, 2001, after having attended the Hong Kong International Film Festival, Panahi was arrested in JFK Airport, New York City, for not possessing a transit visa. Refusing to submit to a fingerprinting process (apparently required under U.S. law), the director was handcuffed and leg-chained after much protestations to US immigration officers over his bona fides, and finally led to a plane that took him back to Hong Kong. As far as is known, this incident was not reported in any major US newspaper, even though The Circle was being shown in the United States at the time (another irony: for that film, Panahi was awarded the “Freedom of Expression Award” by the US National Board of Review of Motion Pictures).

We are in the season in which critics are likely to use the word courage casually, as in “Natalie Portman gives a courageous performance in Black Swan.” The ongoing struggle of Panahi and thousands of his fellow Iranians remind us what real courage, in the world outside the movie theatre, looks like.

A petition addressed to Iran’s leaders in regard to Panahi and Rasoulof’’s case can be signed here. For one proposal for how world film culture could respond, go here.

A fairly detailed chronology of events around Panahi’s imprisonment can be found on Wikipedia. Panahi’s counter to the official charges, as well as the source of this entry’s title quotation, can be found here.

I have so far found no U.S. coverage of Panahi’s treatment in America in spring 2001. A report here from Australia suggests that he was detained but not arrested. Senses of Cinema has published Panahi’s letter to the Board of Review protesting his treatment on that occasion.

The case of Mohammad Taqi Khalaji is discussed here and here.

P.S. 22 December 2010: Yesterday Jonathan Rosenbaum posted his June 2001 review of The Circle. It’s an excellent piece, providing both in-depth analysis and broader context, and it does make reference to Panahi’s detention upon arriving in the U. S.

P.P.S. 22 December 2010: Thanks to Shelly Kraicer for a name correction.

P.P.P.S. 26 December 2010: Director Rafi Pitts has published an open letter to President Ahmadinejad about Panahi and Rasoulof’s sentence. Read it here at mubi.

Jafar Panahi and Jia Zhang-ke, Asian Film Awards 2007. Photo by DB.

A last celluloid banquet from Vancouver

Detail from “Crimson Autumn” (1931) by Ural Tansykbaev (from The Desert of Forbidden Art)

Kristin here:

A Film Unfinished (Israel; dir. Yael Hersonski, 2010)

A Film Unfinished satisfies on many levels. It is based on several reels of an unfinished Nazi propaganda film labeled “The Ghetto,” discovered among an archive of thousands of cans of Nazi footage. On a simple documentary level, the scenes in the film show precious evidence of life in the Warsaw ghetto in the 1941-42 era, before most of its inhabitants were sent to death camps. As a piece of historical research on the part of the filmmakers, who found written and taped material that shed considerable light on this mysterious footage, it  comes across as a tightly constructed detective story. For theorists of documentary who want to stress that no non-fiction films can reveal life as it is, without manipulation, A Film Unfinished provides a dramatic example.

comes across as a tightly constructed detective story. For theorists of documentary who want to stress that no non-fiction films can reveal life as it is, without manipulation, A Film Unfinished provides a dramatic example.

The samples from the silent footage shown early in A Film Unfinished show a strange combination of subject matter. Apparently candid footage of people in the street, going about their daily lives, is mixed in with scenes of well-dressed men and women in restaurants or elegant apartments. How do these incongruous scenes fit together?

The filmmakers found extensive diaries kept by one of the officials in charge of the Ghetto, as well as taped testimony given in 1961 by one of the main cameramen who recorded the footage. Passages from these, read over additional footage from the film,gradually reveal at least part of the purpose behind the footage. The Nazis apparently wanted to show that some inhabitants of the ghetto were living a normal, even luxurious life (above left). But other scenes were shot showing these same people on sidewalks. Beggars pass by them, but the actors playing the well-off Jews were instructed to ignore them. The result would  presumably have been a display of Jews not only living well but also indifferent to the fates of their less fortunate neighbors.

presumably have been a display of Jews not only living well but also indifferent to the fates of their less fortunate neighbors.

The filmmaking process frequently intrudes. Apart from the voiceover readings from witnesses to the filming, there are occasional glimpses of cameramen in the backgrounds of scenes (left). Moreover, one reel of the rediscovered film turned out to be unedited takes of several brief sequences, showing retakes of the same footage. Thus an apparently candid shot of two little boys looking into a shop window abundantly stocked with food turns out to have been staged; we even get a glimpse of one of the filmmakers leaning into the shot to direct the boys. A scene of police clearing a crowded street was done by assembling a large group of Jews and then having the police drive people away (the scene at left being part of that action). Urgency was added when the filmmakers fired shots into the air to frighten the crowd.

An added layer was given to A Film Unfinished by assembling a small group of men and women from the ghetto who witnessed many of the events. They are seen watching the film and adding comments. One remembers having seen the filming. Another worries that she will see someone she once knew among the faces on the screen. The presence of these witnesses emphasizes the fact that what we are watching in the rediscovered footage is both an elaborately staged series of events and a grim record of reality in the ghetto. A particularly grim sequence shows men with a handcart gathering corpses from the sidewalks (where helpless relatives, without any other recourse, dumped them overnight). These are taken to a mass grave, where they are stacked like firewood, covered with sheets of paper, and buried. Though the men working at this grisly task were clearly told what to do by the filmmakers, the fact remains that this gathering and disposing of bodies was a routine that went on daily in the late days of the ghetto.

A Film Unfinished would be very useful in a class on documentary cinema.

The Desert of Forbidden Art (Russian/USA/Uzbekistan; dir. Tchavdar Gorgiev and Amanda Pope, 2010)

Our interest in 1920s and 1930s Soviet avant-garde art led David and me to this film. It reveals the remarkable, unknown work of Igor Savitsky, a Russian Russian archaeologist who discovered the culture and art of the Karakalpakstan region of Uzbekistan. Applying for government funds to create the Karakalpak Museum of Arts, Savitsky initially stocked it with the jewelry, costumes, pottery, and other local cultural artifacts that were discouraged by the Soviet modernization policy.

He also discovered that there were many hidden paintings and drawings by artists whose avant-garde tendencies had gotten them into trouble with the central Soviet government in the Stalinist era. In 1966 he secretly–and very illegally–began using government money to buy up whole caches of these works. By the time of his death in 1984, he had acquired around 44,000 of them! Many are still in storage, awaiting restoration, but the galleries of this remote museum are full of extraordinary, hitherto unknown artworks.

The Desert of Forbidden Art is informative not only about the history of Savitsky and the museum, but it reveals something of the current culture of this isolated province, a culture which figures prominently in the artworks as well. Sons and daughters of the artists appear on camera, as does Marinika Babanarzorova, the museum’s current director. Naturally many beautiful artworks are on display as well.

The film touches only briefly on the fact that these artworks have been hidden away in a remote desert area which is also increasingly under the sway of Islamic extremism. A few documentary shots show the dynamiting of ancient rock-cut Buddha statues in adjacent Afghanistan in 2001. The head of the Nukus Museum was invited to appear with the film at the VIFF, but she was unable to get permission to leave the country. One is left wondering whether these artworks will need to be rescued anew.

The film is screening widely at film festivals and societies, mostly in the USA but in a few other countries as well. See its website for a schedule of upcoming showings. It also will be run in April or May, 2011 in the PBS series “Independent Lens.”

Certified Copy (France/Italy/Belgium; dir. Abbas Kiarostami, 2010)

This was the film I was most looking forward to at the festival, and it was the last–and best–one I saw. As usual, Kiarostami has come up with a novel approach to storytelling. (See David’s entry on Shirin.) After only one viewing, I’m not confident enough to say much about Certified Copy. Besides, almost anything I say about the plot will give away too much. This is a puzzle film that unfolds very slowly and very subtly.

It seems to work in ways almost opposite to those of the big puzzle film of the year, Inception. That film was almost all exposition, which we had to frantically note and try to piece together to get even a rough grasp of the plot. Certified Copy has almost no exposition–or none that we can recognize immediately or even trust when we do recognize it. I could gauge how slowly that recognition comes by the fact that the laughter at apparently incongruous behavior between the characters gradually faded. Different members of the audience realized at different moments that what had seemed incongruous maybe wasn’t after all, though it’s possible that the incongruity was just increasing right up to the end. Close to the end, only a lady two rows behind me was still laughing.

Essentially what happens is that a plot unfolds, and despite a lack of solid information, most of us probably infer from the conversations enough to assume we understand the two main characters and their relationship. Eventually their actions suggest that perhaps an entirely different plot and relationship has been unfolding all along. (This comes fairly late in the film, in maybe the last third or even quarter.) Perhaps the information we receive does not allow us to decide in this ambiguous situation, though I think people do tend to decide. I decided one way, David decided the other.

Interestingly, this mirrors in longer form the last sequence of Under the Olive Trees. There we are not told what the girl replies when the boy runs after her and proposes marriage one last time. In that case, too, I decided one way, David the other. Years ago we told Kiarostami this, and he laughed and said men tend to assume the girl accepts him, while women assume she rejected him. (I think there actually are some fairly clear clues earlier in the film that she will reject him, but explaining those would be a different entry.) That may be the case here, that men and women will reach opposite conclusions.

On the other hand, and this would require at least a second viewing, the film may remain utterly ambiguous about which plot is “real.” Or it may even stray into the territory of the inexplicable, à la Buñuel or David Lynch, where the difference parts of the story are each “true” but incompatible. M. Tsai suggests, “‘Certified Copy’ plays out a bit like a romantic comedy directed by David Lynch with its distinct two-halves connected by a thread.” (Not to be read until you’ve seen the film.)

Apart from its teasing, baffling, shifting elements, Certified Copy contains two fine lead performances and, of course, some beautiful cinematography. There’s a bit of a surprise, in that Kiarostami for the most part avoids his characteristic sweeping views of landscapes. Tuscan hilltop towns would seem to be perfect for his typical shots of vehicles struggling up bending roads, but we are largely confined inside the car during the driving scene, watching the characters and not the glimpses of trees through the windows. Those yearning to see Italy must be content with stone or painted stucco walls (as at the left).

Apart from its teasing, baffling, shifting elements, Certified Copy contains two fine lead performances and, of course, some beautiful cinematography. There’s a bit of a surprise, in that Kiarostami for the most part avoids his characteristic sweeping views of landscapes. Tuscan hilltop towns would seem to be perfect for his typical shots of vehicles struggling up bending roads, but we are largely confined inside the car during the driving scene, watching the characters and not the glimpses of trees through the windows. Those yearning to see Italy must be content with stone or painted stucco walls (as at the left).

For many links to articles and reviews, see David Hudson’s helpful wrap-up on Mubi. (Again, not until you’ve seen the film.)

Sodankylä Forever (Finland; dir. Peter von Bagh, 2010)

DB here:

Do writers write books about fanatical readers? Do composers write operas about opera lovers? Sometimes, but not to the degree that cinephiles delight in making films about their passion. Case in point: Peter von Bagh’s Sodankylä Forever. The Festival screened two films devoted to Finland’s Midnight Film Festival, which not only runs movies around the clock but hosts marathon interviews with filmmakers.

It isn’t your usual red-carpet event. The town is tiny. Guests are treated to campfire cookouts and invited to play soccer. But watching old clips, catching snatches of the Johnny Guitar theme, and hearing revered directors spin their yarns is enough to bring pleasure. There are moments of drama—Zanussi and Makavejev boycott a screening of Potemkin because of its “totalitarian” ideology—but mostly the filmmakers muse in a relaxed fashion about the good, and bad, old days.

The Yearning for the First Cinema Experience treats a core cinephile topic: What was your earliest encounter with the movies? Disney films, as you might expect, play a major role, but so too does Frankenstein (which made Victor Erice realize that people kill other people) and even the MGM lion (which startled Kiarostami in his childhood). The First Experience includes more mature epiphanies, such as Bob Rafelson’s obsessive visits to Manhattan’s Thalia. If the official classics get particular attention, it’s perhaps because, as Costa-Gavras says, “Everything was done in the silent cinema.”

So cinephiles are nostalgists, sentimentalists, even narcissists. But we aren’t oblivious to history behind the screen. The Century of Cinema episode focuses on directors’ relation to World War II (a continuing fascination of von Bagh’s). An era of purges, battlefront savagery, and prison camps, created, Szabo reflects, “a generation without fathers.” Jancsó, who served time in a Finnish POW camp, pays tribute to his hosts with a recitation, in Hungarian, of the opening of the Kalevala.

After the war, however, several Western European directors recall the advent of a new era of intelligence and creative engagement. The spirit was most apparent in the Italian Neorealist films. Erice tells of sneaking a forbidden print of Rome, Open City out of customs so that Spanish cinephiles could see it. In Eastern Europe, of course, things were different, and tales of censorship and young directors’ struggle to innovate are treated as continuations of wartime crises and constraints. Alexei German sums up the status of the artist who refuses to affirm official culture: “We are not the doctors, we are the pain.” Samuel Fuller, who has already explained that being assigned to a rear-guard unit in a retreat is a death warrant, is given the epilogue. He recalls visiting the tidiest graveyard he has ever seen and turning to watch the wind rustling the grass. Was he imagining how the scene would look on film? Naturally, arch-cinephile von Bagh shows us.

DB, Abbas Kiarostami, KT. Chicago, March 1998.

Another dispatch from Vancouver

Kristin here:

Surviving Life (Czech Republic; dir. Jan Švankmajer, 2010)

I became a fan of Švankmajer’s work back in 1988, when I saw Alice, his first feature. David and I gradually explored his shorts and discovered that some of them were among the great classics of the animation form, perhaps most notably Jabberwocky and Dimensions of Dialogue. Švankmajer mostly concentrated on object animation, often combining found objects like tools, stuffed animals, dentures, and food in bizarre ways to create figures.

But after Alice, Švankmajer continued to make features, and they contained less and less of what he was best at: animation. Faust was all right, but I suffered through Conspirators of Pleasure and skipped Lunacy altogether. The director has claimed that Surviving Life is to be his final film, so I thought I owed him a last chance. It’s lucky I did, since it’s a real comeback for him, and a return to what he does best.

Whether Švankmajer really wanted to eschew live-action filmmaking and take up animation again is a moot point. He appears in a prologue, not exactly as himself but as a pixillated cut-out photographic figure (apart from the same typical cut-ins to real speaking mouths that became rather tedious in Alice). He describes how he intended to make a live-action feature, but with a small budget could only afford cut-out animation. He demonstrates by hopping about the frame like a figure in a child’s TV show. At the end, he checks how much time the prologue has taken up–two and a half minutes–and mutters that it’s not very long. His mordantly amusing speech doesn’t suggest whether he really had tried to make the film with live action. Indeed, the actors who are represented by the cut-out photographs obviously had to act out their movements, in costume, and to provide their voices. How much cheaper all this could be is debatable.

The story is about dreams, and specifically about a man stuck in a dull desk job who dreams of an exotic woman in red. His doctor sends him to a psychiatrist whose office contains photos of Freud and Jung, each of whom listens and reacts with applause or contempt when his own or his rival’s theory is employed. The hero is horrified when he discovers that the psychiatrist is trying to rid him of his dreams when his own desire is to live within them.

We tend not to think of cut-out animation when we think of Švankmajer, but predictably he proves a master of it. At times the technique resembles that of Terry Gilliam in the animated interludes of Monty Python’s Flying Circus, especially in scenes shot in a black-and-white cityscape with surrealist objects emerging from the windows (see above and below). The “actors” appear as smoothly animated photographs except for close shots, when the actual actors are shown. The technique works brilliantly, with the cuts between the image and the real person being smoother than most Hollywood matches on action.

If Švankmajer has chosen this as his swan song, he has gone out reminding us why we admired him in the first place.

The White Meadows (Iran; dir. Mohammad Rasoulof, 2009)

There are probably a lot of indirect comments on the political situation in Iran in films from that country. Some are obvious to all, others no doubt only to people who live that situation every day. Few, however, can be so overtly allegorical as The White Meadows. Oddly, the allegorical implications are so clear that they can be grasped immediately and do not impinge on the intriguing strangeness of the tale being told.

The central figure is a man who rows his small boat across a highly saline sea, stopping at islands and coastal villages in deserts caked with salt formations. (Yes, another Iranian journey film.) At each stop he gathers the tears of the local people, gradually accumulating a small bottleful. Each stop also yields a fable-like incident that reflects the plight of certain sectors of Iran’s population: a beautiful virgin is sent as a sacrifice to a sea god, an unconventional artist who refuses to paint naturalistically is tormented and sent into exile, and so on. The overall impression is of universal suffering, and the ending suggests that this suffering benefits only the rich and privileged.

The white and tan landscapes and pale blue sky and sea provide stunning locales for this simple tale, shot around Lake Urmia in northeastern Iran.

While watching The White Meadows, one wonders how Rasoulof could get away with such an overt criticism of religious and governmental repression in Iran. He couldn’t, quite. He was arrested alongside Jafar Panahi (who edited The White Meadows) and about a dozen others on March 2. Fortunately he was released fairly soon, on March 17. What his future as a director in Iran is remains to be seen. The government has long tolerated having one set of films for local popular consumption and another that will be confined largely to the international festival circuit. Not surprising, since these days Iran’s filmmaking is one of the few areas in which the country is seen internationally in a positive light. Still, such a bitter yet appealing film clearly stretches such tolerance.

Every year it seems more and more likely that the increasingly tenuous new Iranian cinema will finally be snuffed out, and every year–so far–we see bold and imaginative films coming from that country. We can only hope that with the arrests earlier this year, we are not seeing the long-expected end.

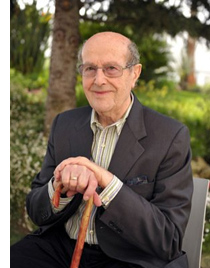

The Strange Case of Angelica (Portugal/Spain/France/Brazil; dir. Manoel de Oliveira, 2010)

The fact that Oliveira was 101 when he made this film, as well as the fact that he is still directing at least a film a year (for last year’s Eccentricities of a Blond Hair Girl, see here), is too extraordinary not to be remarked on. Yet we shouldn’t let it dominate our view of Angelica or tempt us to treat it as an old man’s film. Slowly paced and meditative it may be, but it is also imaginative and full of humor, despite being centered around a young man’s obsessive love for a dead woman.

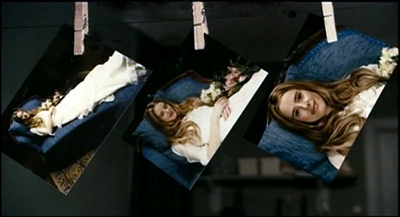

The protagonist, Isaac, is a photographer living in a boarding house in a town in the Duoro Valley region of Portugal. (Oliveira’s first film was a beautiful city symphony, Douro, Faina Fluvial, a poetic study of the river in the same valley made in 1931.) Called upon to photograph a beautiful woman who has died shortly after her wedding, through his viewfinder he sees the corpse open her eyes and smile at him. The same thing happens when he gazes at photos of her hung up to dry:

He falls in love with her, and her ghostly figure visits him at night, wafting him up into the air and flying over the river with him. Although he wakes from dreams several times, we are left in doubt as to whether Angelica really has been appearing to him.

The film seems to be set in contemporary times, and yet it has an old-fashioned look t it. The protagonist photographs men at work with hoes in a nearby vineyard, though his landlady remarks that no one does manual labor anymore. But most obviously, the film has the look and feel of a silent film. The shots of Angelica and the hero flying are superimposed ghostly figures straight out of Edwin S. Porter’s Dream of a Rarebit Fiend (1906). Camera movements are used sparingly, as in many silent films. Scenes often consist mostly of the hero taking his photographs or thinking of his phantom love, and his occasional cries of “Angelica!” could be rendered as intertitles. The use of solo piano music by Chopin reinforces the sense of watching a “silent” film.

(1906). Camera movements are used sparingly, as in many silent films. Scenes often consist mostly of the hero taking his photographs or thinking of his phantom love, and his occasional cries of “Angelica!” could be rendered as intertitles. The use of solo piano music by Chopin reinforces the sense of watching a “silent” film.

Yet there are occasional scenes of dialogue. The best scene in the film may be the one where over the breakfast table the other boarders discuss their concerns about Isaac’s state of mind. The scene ends amusingly with the camera holding on the landlady’s bird jumping around its cage, watched with great attention by her cat.

Oliveira will turn 102 on December 11. He is listed on Wikipedia has being in pre-production for A Missa do Galo.

Kawasaki Rose (Czech Republic; dir. Jan Hrebejk, 2009)

(Note: Many reviews and the VIFF program give the title as Kawasaki’s Rose, but the title on the film is as given above.)

This film creeps up on you. At first it seems poised to be yet another study of a failed relationship among upper-middle-class characters. A documentary is to be made about Pavel Josek, a noted professor famous for his past resistance to the Communists. The sound-man on the shoot is his son-in-law Ludek. His daughter Lucie has been told that a large tumor just removed is benign. Ludek confronts her with the fact that he has been cheating on her during her illness, and he undermines her efforts at disciplining their daughter.

But this conventional soap-opera material gradually opens out as files discovered during research for the documentary seem to reveal that Josek had in fact cooperated with the Communist regime, apparently including his participating in the torture of prisoners. From that point, Ludek recedes into the background and further political and personal revelations give the film considerable depth and complexity.

Kawasaki Rose was beautifully shot in full anamorphic widescreen, with images around the harbor in Göteborg, Sweden being particularly well composed.

While I was watching the film, I was reminded equally of Wajda’s Man of Marble and von Donnersmarck’s The Lives of Others. On the one hand, a film project that digs into the past of a heroic figure who turns out to be not quite so heroic, and on the other a study of the effects of interrogations into private lives under a totalitarian regime.

Kawasaki Rose (the title derives from an origami pattern and is given to a Japanese character in the film who paints flowers) is the Czech Republic’s entry for a foreign-film Oscar nomination. I wouldn’t be surprised if it gets one.