Archive for the 'National cinemas: Italy' Category

Finding a form: The College Cinema at the Venice International Film Festival

This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (Lemagang Jeremiah Mosese, 2019).

DB here:

For the third year I participated in the Mostra’s College Cinema, a wonderful program that funds and guides three features by up-and-coming directors and producers. (Details are here.) I’ve reported on the earlier sessions here and here.

This year my developing reaction to the trio of features was governed by what Kristin and I did the day before our panel. We saw two superb classics: Bertolucci’s The Spider’s Stratagem (1970) and István Gaál’s Current (1964). They reminded me of what ambitious filmmaking was like before the arrival of screenplay manuals dictating character arcs and first-act turning points.

In those days, a filmmaker was likely to find a distinct, even unique form for a story. The filmmaker would design the film organically, creating a large-scale shape that would let technique and dramatic structure build in relation to each other, not in accord with standard formulas.

Coupling via monitor

A good example is The End of Love, directed by Karen Ben Rafael. The Israeli Yuval and the French woman Julie have a child. He waits in Israel for a new visa, while Julie must manage child care under the pressures of her job in an architecture firm. Each begins to suspect the other of infidelity, and their families in each country add to the tension.

So much for a traditional “relationship” movie, whose ups and downs could have been presented in a standard way. But Rafael and her co-screenwriter Elise Benroubi hit upon a fresh way to trace the couple’s conflicts. Yuval and Julie are keeping in touch via a Skype-like video service, and we are completely confined to their exchanges in this medium. We see only what they see, in a series of to-camera shot/reverse-shots.

Some recent genre films have been “monitor movies,” like Paranormal Activity 4 (2012), Chronicle (2012), Unfriended (2014), and Searching (2018). But these exploit the device for suspense and horror. The End of Love lets the conditions of video communication structure the ongoing drama. A teasing opening suggests that the camera is lying in bed between the couple as they caress themselves; the next scene–a remarkable shot in itself (above)–reveals that video is their channel of communication.

As the film goes along, tensions between Yuval and Julie are presented as much through the mechanics of video exchanges as through the actors’ (very persuasive) performances. Unanswered calls signal a growing indifference. A mysterious shot wobbling through a dance club suggests either a phone accidentally turned on or a loud, defiant assault on the other person. I was especially taken by the moments when we get slight change of eyelines as characters look from the camera to study the display image of the other person.

The End of Love triggers a lot of ideas about how modern couples are led to expect that technology can overcome family problems. Being always online, always “in touch,” doesn’t mean that you’re engaging authentically with someone else. For all its power, the video hookup in the film creates an illusory intimacy, and its glitches stand for the aggravations, little and big, that come with physical separation. This thematic implication grows organically out of the creative decision to confine our viewpoint to what the camera can see and hear, but not heal.

Social drama into community myth

Another vigorous example of letting the material summon up the film’s form is This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection. Directed, written, and edited by Lemogang Jeremiah Mosese, it’s a poetic work that develops its imagery out of a dramatic situation.

The eighty-year-old Mantoa learns that her only surviving relation, her grandson, has died in a mining accident. After being consoled by her priest and the local choir, Mantoa tries to restabilize her life. But when she learns that her village is to be flooded for a dam project, she vows to save the bodies in the local cemetery–and to prepare her own grave.

This tale, set in Lesotho, is framed by a narrator telling us about her and her community. He sits in a blast of yellow light adjacent to a pool hall, and at intervals the story action pauses for his comments. The film takes its time–about 300 shots in two hours–to dwell on the details of her daily routine, such as the portable radio hanging from the wall, or Mantoa’s changing outfits.

But there are also more surreal images, such as Mantoa on a burned-out bedspring being slowly surrounded by sheep. The community that eventually supports her is presented as an almost abstract force, as are the out-of-focus government workers slowly hacking away at the perimeter of the village. The climax of the film makes powerful use of those figures as Mantoa confronts them in her boldest provocation of all.

Again a familiar situation–a tenacious elder tries to halt the destruction of a community (think Wild River)–is given fresh life through formal elaboration. Out of a primal conflict, Mosese generates a work of mythic dimensions. He does it through lustrous visuals, an evocative soundtrack, and a character who creates a legend that will live for generations.

Town and country

If The End of Love traces a jagged decline in a relationship, and This Is Not a Burial lifts a social conflict into spirituality, Lessons of Love finds another structure, this one aiming to express the inarticulate feelings of a man stuck in a situation. It’s a circle.

Yuri toils on his father’s farm, while his younger brother and sister try to avoid their responsibilities. Stolid, silent, and glum, Yuri harbors a good deal of anger, occasionally expressed in road rage. He relates to the world almost completely through physical contact.

Director Chiara Compara and her co-screenwriter Lorenzo Faggi start from a classic pattern: the migration of an innocent from the countryside to the city. This pattern is refreshed through a strategy going back to Neorealism: the insistence on the physicality of daily routines. A prolonged moment of Yuri tuning a radio recalls the famous scene of the maid’s morning ritual in Umberto D.

The early stretches of Lessons of Love stress the demands of farm work. The first shot is of a milk can, and soon we see logging, veterinary inspections, the purchase of a cow, and the dull evening meal. But we also get a sense of Yuri’s longing when he soberly eats during a TV love scene, and soon enough he’s visiting a strip club, watching as impassively as he did the TV show.

Through a tissue of routines, Yuri’s vague thoughts about escape emerge, and soon he is considering buying cowboy boots, dating Agata, and getting a construction job in town. That’s when the circular structure gets initiated, and new routines replace the old ones. Again, the details of hard labor aren’t stinted, and Yuri is challenged to break out of his smoldering solitude. Can a man who punches and embraces his favorite cow, and who furiously whacks a driver-side mirror, ever learn to talk to a woman who’s kind to him? The last shot of the film, discreetly echoing the first, provides the answer.

A fraught love affair, a defiant elder speaking up for a community’s heritage, and a lonely, locked-in man are familiar enough points of departure for a film. But these three College features offer fresh, rigorous treatment of their stories. Three acts and vulnerable-but-relatable heroes and heroines? Not necessary! There are other ways to go, as young filmmakers can show us.

Thanks as usual to Peter Cowie for inviting me to join the College Cinema panel, and to Savina Neirotti, the Head of the program. Thanks as well to other participants for lively conversation: Chaz Ebert, Glenn Kenny, Mick LaSalle, Michael Phillips, and Stephanie Zacharek. As ever, we appreciate the kind assistance of Michela Lazzarin and Jasna Zoranovich for helping us before and during our stay.

Glenn has a fine appreciation of the College films on rogerebert.com. He too was reminded of Wild River, but no surprise as we’re both nerds in this (and other) respects.

The End of Love (Karen Ben Rafael, 2019).

Sometimes an actor’s back…

Il Maschera e il Volto (1919).

…can crisply punctuate a scene.

DB here:

One of the 1919 films on display at Cinema Ritrovato this year was Augusto Genina’s Il Maschera e il Volto (The Mask and the Face, 1919). It’s drawn from a popular play that satirized the erotic stratagems of the elite. The movie begins by introducing a gaggle of couples at a Lake Como house party, so I expected that it would create interlocking intrigues in the manner of silent-era Lubitsch films like The Marriage Circle (1924). Not so: the plot concentrates on one romantic triangle. The version we have, at 1799 meters, might be a little shorter than the original (said to be around 1900 meters), but it seems likely that the plot we have dominated the initial release too.

Savina is betraying her husband Paolo with the family lawyer Luciano. During the house party Paolo declares that a cuckolded husband has every right to murder the unfaithful wife. When he learns of Savina’s affair (but not Luciano’s complicity), he orders her to leave the household immediately. Paolo declares that she will become dead to him and their friends.

Paolo tells Luciano that he killed Savina. We get a lying flashback (yep, already and again) that shows him strangling her and dumping her body in the lake. Savina overhears his false confession. When she hears Luciano asserts that she got what she deserved, she realizes he’s worthless. Disillusioned about both of the men in her life, she follows Paolo’s order and leaves their estate.

Of course a woman’s corpse, face mutilated, is soon found in the lake. Now Paolo must stand trial for Savina’s murder, and Luciano must defend him.

Not the funniest comedy I ever saw, but it has a grim charm. One particular scene made me happy.

Piano ensemble

Readers of this blog know that I like to study staging in 1910s films, and Genina provided nifty examples in the 2017 Ritrovato season. Like the Lupu Pick film I reviewed at this year’s jamboree, Il Maschera lies stylistically midway between pure tableau cinema and editing-driven construction. Interior scenes are often broken up by many cuts, but they’re typically axial, straight-in and straight-back, without reverse angles. (The exception is the trial scene. As in many 1910s films, it creates a more immersive space through “all-over” cutting.) In most scenes, the shots enlarge actors to follow their responses, but we don’t get setups that penetrate the space, putting us inside the flow of action.

Still, axial cuts, as Eisenstein and Kurosawa and John McTiernan knew, have a peculiar power. They can be abrupt and punchy, or more subtle in readjusting the framings. The latter option is on display in the film’s first big scene, when all the guests gather in the salon around the piano.

The scene runs about two and half minutes and consists of twelve shots and six dialogue titles. What’s worth noticing is the slight variations in setups, coordinated with what Charles Barr has felicitously called “gradation of emphasis.” Often the changing setups are masked by an inserted dialogue title, so there are no bumps in continuity.

The orienting view is a bustling shot that piles up faces and shoulders along the horizontal axis.

In an axial cut-in, the guests debate the righteousness of Othello’s murder of Desdemona. A further cut-in shows Luciano and Savina on the far right sharing glances. (The curly-haired woman will prove an innocent witness.) It’s a Hitchcockian situation, but without the POV singles.

Soon an older husband rises from his chair in the rear (another cut-in, “through” the group) and comes forward to join them. He draws alongside the husband to calm him down.

I’ve talked about crowded tableaus like this before. The Americans I survey were somewhat bolder than Genina in jamming the heads even closer together, creating partial faces that float out of the background. Genina has, however, other goals in view.

The woman in white

During the cut-ins, Genina takes the opportunity to rearrange the actors around the piano and re-scale his shots. There are five distinct variants of the piano grouping; even setups that might seem the same aren’t quite. There are two setups of the adulterous couple. All these are calibrated to suit the action presented.

For instance, when Paolo launches his rant about unfaithful women, the framing is tighter to favor him, and the foreground woman in white is primed for her big moment.

Similarly, the second cut to the adulterous couple is framed somewhat differently from the earlier one (on left), with Luciano pushing aside the cute curlyhead. He and Savina are listening more intently to Paolo’s denunciation of faithless wives.

So what seem to be fairly straightforward repetitions of setups are in fact minutely adjusted to favor certain actions. This strategy allows Genina to return to the whole ensemble.

In a closer view, the woman in white suggests that they stop arguing about infidelity and go in to play cards. She rises, blotting out Paolo in mid-rant.

The effect would be less pointed if she were in black like the other women.

Everyone but the older husband turns away, and people retire to the next room in the distance. They drain the space like water emptying out of a tub. That leaves what filmmakers today would call the scene’s button: the old man noticing that Luciano and Savina don’t join the group. Throughout the scene they’ve been literally marginalized on the far right.

It’s through this older man we just barely see the couple leave. He seems to understand the game they’re playing. and now he watches them disappear, perhaps to a private rendezvous.

The scene ends with another turning from the camera, another actor’s back letting us know the action is done.

Very often, turning from the camera signals the end of scenes, and of films.

It would have been fairly easy for any director to simply let the actors clustered around Paolo drag him off to play cards. But by having the woman in the foreground pop up, cut off our view of Paolo, and trigger a general exit Genina makes the action taper off briskly. Staging in the silent cinema is full of such little felicities, and it’s one job of criticism to appreciate them. It’s especially important since such techniques seem no longer part of filmmakers’ skill sets.

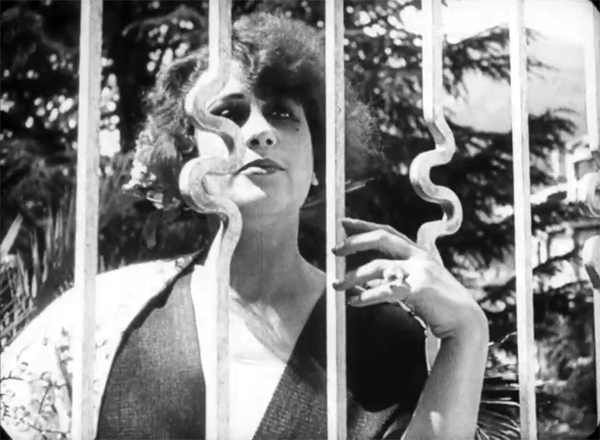

Then again, some Maschera images just whack you in the eye. Who doesn’t sense passion, elaborately caged, in the image below?

Thanks as usual to the Cinema Ritrovato Directors: Cecilia Cenciarelli, Gian Luca Farinelli, Ehsan Khoshbakht, Mariann Lewinsky, and their colleagues. We particularly owe Mariann for her curating of the Hundred Years Ago series every year. Special thanks as well to Guy Borlée, the Festival Coordinator.

Information about La maschera e il volto can be found in Vittorio Martinelli’s Il Cinema Muto Italiano: I film del dopogerra/1919 (Rome: Bianco et nero, 1960), 170-172.

Other Sometimes... entries consider a single axial cut, a shot in depth, a jump cut, a reframing, and a production still.

Il Maschera e il Volto (1919).

Vancouver 2018: Panorama of the Rest of the World, the sequel

Seder-Masochism (2018)

Kristin here:

The Vancouver International Film Festival is over, but we still have films to talk about. Here are four, and David and I will probably post another blog apiece. Between Venice and Vancouver, we have seen a lot of great and very good films recently. Once again, the claims of the death of cinema are robustly refuted.

Dogman (Matteo Garrone, 2018)

Garrone is best known outside Italy for his 2008 film Gomorrah. While that film was about gangs and organized crime in Naples, Dogman centers around a shifting relationship between a meek-mannered dog/boarder/groomer who has fallen in with a volatile, enormous local thug.

The title emphasizes the honest side of Marcello’s life, and we see some comic scenes of him with dogs. Soon, however, it is revealed that he sells cocaine on the side and sometimes acts as a getaway driver for thefts committed by the monstrous ex-boxer, Simoncino. Eventually he even takes the fall for a robbery and spends a year in jail in Simoncino’s place.

We’re clearly intended to side with this sad sack. After one house robbery, Simoncino’s partner reveals that he put a dog in the freezer to keep it quiet. Marcello sneaks back in and, a suspenseful and remarkable scene, attempts to revive the frost-covered animal. He also dotes on his daughter and seemingly pursues his criminal activities in order to be able to take her on “adventures,” including scuba-diving.

Despite this sympathetic side, however, Marcello never seems to consider giving up crime; he’s mainly interested in getting his fair share of Simoncino’s ill-gotten gains. Although the film is continually entertaining and suspenseful, its ending is somewhat disappointing. We are left knowing what Marcello’s probably fate will be, but we have little sense of his attitude toward what has happened.

Marcello Fonte, looking like a rather emaciated version of the comic Toto, won the Best Actor prize at the Cannes Film Festival.

Magnolia has the US rights and plans to release Dogman in 2019.

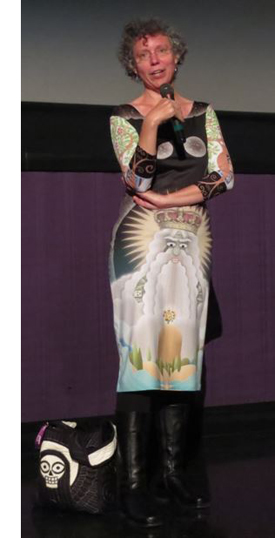

Seder-Masochism (Nina Paley, 2018)

Seder-Masochism is the only US film I’ll be writing about from Vancouver. (We tend to skip US films here, since we assume we can see them in the US.) Paley’s not part of the Hollywood establishment or even the mainstream indie scene. It’s not easy to see her wonderful animated films on the big screen, but their bright colors and imaginative graphics deserve to be shown that way.

Seder-Masochism is Paley’s second feature, after Sita Sings the Blues (2008). She does all the animation herself, holed up, as she puts it, like a hermit with her computer. She also avoids the standard distribution methods for indie films, because she’s an opponent of copyright for artworks. She provides open access to her films, initially at festivals and then online. (For more on this, see my transcript of a Q&A I helped run when Sita played at Ebertfest in 2008.)

Seder-Masochism is Paley’s second feature, after Sita Sings the Blues (2008). She does all the animation herself, holed up, as she puts it, like a hermit with her computer. She also avoids the standard distribution methods for indie films, because she’s an opponent of copyright for artworks. She provides open access to her films, initially at festivals and then online. (For more on this, see my transcript of a Q&A I helped run when Sita played at Ebertfest in 2008.)

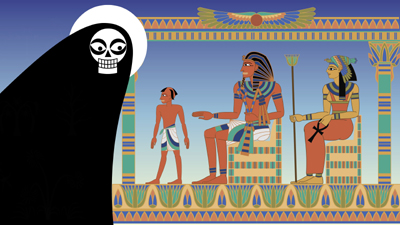

I should say that no one should assume from the title that this film is grim and/or anti-Jewish. On the contrary, it’s a witty exploration of the Exodus myth and its historical links to the decline of early goddess worship in favor of all-powerful male gods in monothesism. The framing situation is a conversation between Paley and her father conducted shortly before his death, with Paley as a small goat and her father as God (see top).

I should say that no one should assume from the title that this film is grim and/or anti-Jewish. On the contrary, it’s a witty exploration of the Exodus myth and its historical links to the decline of early goddess worship in favor of all-powerful male gods in monothesism. The framing situation is a conversation between Paley and her father conducted shortly before his death, with Paley as a small goat and her father as God (see top).

This conversation is a mix of humor and serious points about Judaic traditions and particularly the celebration of Passover. The story of Moses and the Exodus is rendered in much the same way she treated the tale of Sita and Rama from the Hindu epic, the Ramayana–with musical numbers. Moses is introduced with “Moses Supposes,” from Singin’ in the Rain, and, inevitably, there is a “Go Down, Moses” episode. Unlike Sita, where blues songs were used throughout, the musical pieces in Seder are wide-ranging, culminating in a brilliant three-minute summary of the history of the territory which is now Israel, done to “This Land is Mine,” the song written to the theme of Otto Preminger’s Exodus. (The sequence, as well as several other excerpts from Seder are available on YouTube.)

The sequences set in ancient Egypt are generally accurate. I was amused by the fact that the animal and bird hieroglyphs in the background inscriptions moved rhythmically during the musical numbers, and the Hathor heads on the sistrums sang along. Using Hathor, the cow goddess, as the golden calf was an inspiration.

Seder-Masochism got the most enthusiastic applause I heard at the festival, partly because the filmmaker was present (in her custom Seder dress). There were Sita fans in the audience, and one Jewish lady asked how she could get a copy to show her 12-year-old daughter. Paley replied that the film will continue to play festivals and probably be available on the fim’s website for download in the spring.

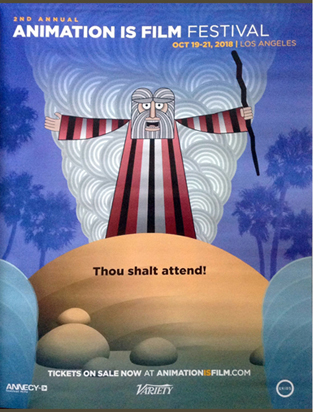

In the meantime, watch for it at festivals–or let the organizers know that you want to see it on their schedule. We were happily surprised to see a full-page ad for the Los Angeles Animation Is Film Festival (October 19-21) in the current Variety (above left) and illustrated by an image derived from the film. You may find others.

Styx (Wolfgang Fischer, 2018)

I was surprised to discover that so far Austrian director Wolfgang Fischer’s Styx has not been picked up by a North American distributor. It seems like the sort of film to appeal strongly to audiences. It’s protagonist is a strong, ultra-competent woman, it has a riveting plot full of suspenseful situations, and it deals with the immigrant crisis facing Europe.

A long portion of the film contains no real dialogue. The opening sequence occurs at the scene of a traffic accident where the heroine, Rike, is established as a doctor as she heads the team treating the victim. Cut to her provisioning her yacht for a solo trip. A lovely shot of a compass “walking” its way down a map establishes her route and distant goal: Ascension Island (see bottom). Her departure reveals that her starting point is Gibraltar (above). From that point, we watch Rike expertly dealing with her vessel, enjoying the solitude of the ocean, and reading about Darwin’s activities on Ascension.

Apart from a few overheard commands during the initial emergency scene, there is no dialogue until Rike makes radio contact with a nearby commercial vessel which warns of a serious storm approaching. A tense scene of her struggle to deal with the storm at night creates the first major suspense of the film. From her arrival in an ambulance in the opening sequence, actress Susanne Wolff is present in every scene, and as an experienced sailor she was able to handle the yacht and do without a stunt double.

Rike comes through the storm without difficulty, but a leaky vessel crowded with African immigrants striving to get to Europe is visible in the distance. Ordered by a coast-guard official not to interfere, she uneasily waits for a sign of a rescue vehicle that still has not shown up after hours of waiting. One teen-aged boy manages to swim from the derelict ship, and he complicates her situation considerably. The dilemma remains: try and take the rest of the refugees on board her small yacht or wait for the promised rescue.

The remainder of the film generates unrelieved suspense as Rike debates what to do and Kingsley begs her to rescue his sister, still abroad the sinking boat. A non-actor discovered in a school in Nairobi, Gedion Oduor Weseka is convincing and touching as the desperate boy.

Nearly all of Styx was shot at sea, with Fischer’s small crew mounting their camera hanging off the sides of the boat and scrambling to keep out of sight during filming. No special effects were used for the storm and other ocean scenes. At intervals some impressive extreme long shots from overhead, presumably taken by drones, emphasize the yacht’s isolation in the vastness of the sea.

The film is riveting from beginning to end. I recommend it, though at least for North America, festival screenings are probably the main places where it can be seen. Perhaps it will eventually be available on streaming services. In some European countries, it will probably be released theatrically.

Transit (Christian Petzold, 2018)

The central premise of Transit resembles that of Casablanca. A group of émigrés are desperately awaiting the letters of transit that will allow them to flee fascist Europe for North America. In this case they’re in Marseille rather than Casablanca, and the plot focuses on one rather ordinary, non-heroic man–or so he seems. Our protagonist is Georg, a Jew lingering in Paris as the authorities arrest fugitives. The authorities are working for a fascist regime, though Nazis are never mentioned specifically.

Moreover, the settings and costumes are mainly modern. Early on Georg flees a round-up through allies covered with spray-painted graffiti (below), and the vehicles in the streets are all contemporary models. Petzold’s avoidance of period mise-en-scene sets up a strange, somewhat surrealist world, but it also invites us to consider the parallel with current social problems.

By chance Georg gains possession of the manuscripts and papers of Weidel, a well-known author who has met a bloody end in a cheap hotel room. Fleeing to Marseilles with a wounded fellow Jew who dies along the way, Georg visits the Mexican consulate and is mistaken for Weidel, whose transit papers for him and his estranged wife have been approved. Naturally Georg accepts the error. While waiting for the papers to come through, he befriends his dead friend’s widow and her son, immigrants to Europe from the Maghreb, and by chance encounters and falls in love with Weidel’s wife (who does not realize her husband is dead), hoping to use the two letters of transit to escape to a new life with her.

Between the inexplicable modern settings and costumes and the extraordinary coincidence of this meeting, the film is far from being realistic. It reminded me of the late films of Manoel de Oliveira (see our earlier reports on Doomed Love, Eccentricities of a Blonde-Haired Girl, The Strange Case of Angelica, and Gebo and the Shadow), with touches of Bresson in the situation and the acting, particularly of Franz Rogowski as Georg. But Petzold is not simply imitating these and other directors. Transit is a remarkable, original film, one of the best we saw at Vancouver.

Transit has been acquired for US distribution by Music Box for an early 2019 release. Definitely keep an eye open for a screening near you, most likely in festivals and large-city art houses and perhaps eventually on streaming..

Thanks as ever to the tireless staff of the Vancouver International Film Festival, above all Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, Shelly Kraicer, Maggie Lee, and Jenny Lee Craig for their help in our visit.

Snapshots of festival activities are on our Instagram page.

Styx (2018).

Bye bye Bologna

Lucky to Be a Woman (1955).

DB here:

How to sum up nine days of Cinema Ritrovato? I logged thirty-two features and half as many shorts and fragments, along with a few panels and workshops. Fate cursed me with the need to blog and to sleep, so I missed many prime items. And that’s including my (sad) decision not to revisit films I’d already seen, so I sacrificed new exposure to masterpieces from Ozu, Mizoguchi, Feuillade, Leone, de Sica, etc.

In this last Bologna roundup, all I can do is wave at some of the surprises and discoveries that captivated me.

Many of my pals praised the Mexican noir Western Rosauro Castro (1950), which I had to miss, but I did get compensated by Prisioneros de la Tierra (1939), an Argentine classic of romantic realism. The plot concerns the exploitation of peasant migrants forced to work in dire conditions. One scene, of a drunken doctor in the throes of the DTs, got a rise out of Jorge Luis Borges.

Even more shocking was the red-light melodrama Víctimas del Pecado (1951, above) by the great Emilio Fernández. A newborn baby dumped into a garbage can; a preening, sadistic pimp who can smoke, chew gum, and dance frantically at the same time; a nightclub dancer who tries to live righteously but winds up in prison for her pains; and several splashy music numbers–who could resist this? Not the Bologna audience, who burst into applause when, after slapping a child silly, said pimp got a quick and violent comeuppance. Of course the gorgeous cinematography of Gabriel Figueroa contributed a lot: One shot of a train blasting black smoke into the night would be enough to exalt a far less delirious movie.

Thanks to Dave Kehr of MoMA, who brought a sampler from his recent Fox retrospective, and to UCLA and other sources, aficionados of American studio cinema had no shortage of delights. Monta Bell’s Lights of Old Broadway (1925) gave Marion Davies a dual role as twins separated at birth and she made the most of half of it, playing a no-nonsense colleen who makes it big at Tony Pastor’s. Part of the fun was the film’s historical references: Teddy Roosevelt as an undisciplined schoolboy, Weber & Fields as a kiddie act, and a solicitous Thomas Edison urging the heroine to invest in electricity.

Ten years later, One More Spring (1935, above) from Henry King offered a gentle seriocomic Depression tale. Two homeless men squatting in a garage take in a woman who sleeps on the subway, and they try to make ends meet with the help of a kindly old couple. At first engagingly episodic in the McCarey manner, the plot gets more tightly bound when the old couple faces the loss of their savings. Janet Gaynor is endearing, as usual, and Warner Baxter brings his clipped energy to the role of a hopelessly optimistic failure. There are no villains. The banker struggles to save his depositors, though he’s frank enough to admit, “It’s all the fault of the Republicans. Still, I’ll vote for them in the next election. With the Democrats you never know what to expect.” Another big laugh from the crowd around me.

That Brennan Girl (1946) exemplified the opportunities that the boom in 1940s moviegoing offered downmarket studios. Apart from the second-tier cast and the warning “Not Suitable for Children,” the production’s B-plus aspirations were clear, yielding a surprisingly polished Republic picture (buffed up by a beautiful Paramount restoration). A woman raised by a predatory mother takes up petty theft and con games. She reforms, but after becoming a war widow she falls back into her old ways–endangering her baby in the process. That Brennan Girl could have served as an example in my Reinventing Hollywood book, since it flaunts a long flashback punctuated by dreams and bits of imaginary sound. Those narrative stratagems pervaded films at all budget levels.

That Brennan Girl (1946) exemplified the opportunities that the boom in 1940s moviegoing offered downmarket studios. Apart from the second-tier cast and the warning “Not Suitable for Children,” the production’s B-plus aspirations were clear, yielding a surprisingly polished Republic picture (buffed up by a beautiful Paramount restoration). A woman raised by a predatory mother takes up petty theft and con games. She reforms, but after becoming a war widow she falls back into her old ways–endangering her baby in the process. That Brennan Girl could have served as an example in my Reinventing Hollywood book, since it flaunts a long flashback punctuated by dreams and bits of imaginary sound. Those narrative stratagems pervaded films at all budget levels.

Another 1940s technique was the chaptered or block-constructed film, Holy Matrimony (1943), a genial comedy about switched identities, contains sections with titles like “But in 1907” and “And so in 1908.” The film, about a painter brought back to London from his tropical hideaway, reworks the Gauguin motif made famous by Maugham’s Moon and Sixpence (1919). Was this release an effort to build on Albert Lewin’s 1942 version of the novel? Monty Woolley plays himself, but Gracie Fields brought real warmth to the clever, ever practical woman who marries him.

Holy Matrimony was a welcome, if minor entry in the John Stahl retrospective. I had to miss the much-praised When Tomorrow Comes (1939) but was happy to break my rule of avoiding things I’d seen before when I had a chance to revisit Imitation of Life (1934). I persist in thinking this better than the Sirk version, not least because of its harder edge. Beatrice Pullman’s exploitation of her servant Delilah’s pancake recipe carries a sharp economic bite, and the brutal classroom scene yanks our emotions in many directions. (While Peola writhes in her seat, her mother asks innocently, “Has she been passin’?”) As in Stahl’s other 1930s efforts, his studiously neutral style is built out of profiled two shots in exceptionally long takes.

Ritrovato has always done well by its diva films, under the curatorship of Marianne Lewinsky. (They’ve just released a hot-pink box set of four classics.) In tribute to 1918 there were several star vehicles. I’ve already mentioned L’Avarazia (1918), an installment in a Francesca Bertini series devoted to the seven deadly sins.

Another high point was La Moglie di Claudio (1918), an exemplary tale of excess. When a movie starts by comparing its heroine to a spider, you know she means trouble. Cesarina (Pina Minichelli) two-times her husband, has an illegitimate child, flirts relentlessly with her husband’s protégé, collaborates with spies, and steals the plans to the cannon the husband has designed. She does it all in high style. As she dies, she falls clutching a window curtain.

In a fragment from Tosca (1918), we got a quick lesson in the illogical powers of cinematic composition. Tosca (Bertini again) visits her lover Mario in prison. Their furtive conversation is played out while the shadows of the guards come and go in the background. That’s a source of some suspense for us.

And for the couple as well. Instead of looking left at the offscreen window itself, which they could easily see, they–like us–turn to monitor the silhouettes.

It’s a nice variant on the background door or window so common in 1910s film.

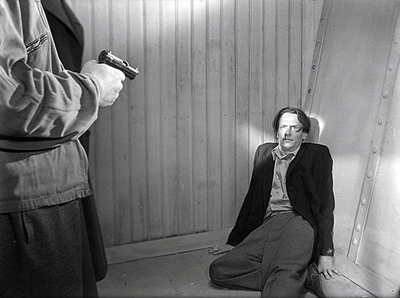

Of all the surprises, the biggest for me was This Can’t Happen Here (aka High Tension, 1950), an Ingmar Bergman thriller. You read that right.

This Cold War intrigue shows spies from Liquidatsia (you read that right too) infiltrating a circle of refugees living in Sweden. The first half hour is soaked in noir aesthetics, with men in trenchcoats glimpsed in bursts of single-source lighting. The preposterous plot gives us a briefcase full of secret papers, attempted murder by hypodermic, torture scenes, and enemy agents acting impossibly suave at gunpoint. A cadre meets in a movie theatre playing a Disney cartoon, with Goofy’s offscreen gurgles punctuating an informer’s confession.

Bergman forbade screenings of the film, but Bologna was given the rare chance to reveal another side of his obsessions with brooding solitude and the pitfalls of love. Peter von Bagh’s illuminating essay included in the catalogue rightly emphasizes how in This Can’t Happen Here murder becomes the natural outcome of an unhappy marriage.

My visit was topped off by the charming Lucky to Be a Woman (1955) in the Mastroianni strand. Sophia Loren, looking like a million and a half bucks, plays a working girl accidentally turned into tabloid cheescake. Mastroianni is a louche photographer who can make her career. Bantering at breakneck speed, they thrust and parry for ninety-five minutes, all the while satirizing modeling, moviemaking, and the itchy palms of philandering middle-aged men. Mastroianni spins minutes of byplay out of an unlit cigarette, while La Loren plants herself like a statue in the foreground, facing us; if Marcello’s lucky, she may address him with a smoldering sidelong glance.

What’s not to like? After thirty-two years, Ritrovato’s magnificence is unflagging.

As usual, thanks must go to the core Ritrovato team: Festival Coordinator Guy Borlée (with appreciation for help with this entry) and the Directors (below). They and their corps of workers make this vastly complex celebration of cinema look easy. It’s actually a kind of miracle.

Ehsan Khoshbakht, Cecilia Cenciarelli, Mariann Lewinsky, and Gian Luca Farinelli.