Archive for the 'National cinemas: Italy' Category

Sometimes a shot . . .

I Topi Grigi, Chapter 6: Aristocrazia Canaglia.

DB here:

… just knocks you out.

In wrapping up my stay at the Royal Film Archive of Belgium, where I concentrated mostly on German films of the late 1910s and early 1920s, I watched a copy of I Topi Grigi (“The Gray Rats”), a 1918 Italian serial. It’s part of an immense series devoted to the adventures of the cadaverous rogue Za La Mort. Directed by and starring the fascinating Emilio Ghione, it’s in the vein of Fantômas and Les Vampires, though I don’t find it as ingenious or funny or as skillfully directed as Feuillade’s masterpieces.

But then you get those moments. Za La Mort and his young charge Leo are aboard an ocean liner when it’s struck by a torpedo. The passengers panic and make for the lifeboats. It ought to be a spectacular scene reminiscent of Atlantis (1913), but there aren’t many shots devoted to this climax. We see only a few images of people rushing up to the deck from their cabins. The central shot showing the crisis is an image slung along the side of the ship, down the row of lifeboats as people scramble into them. The shot is interrupted by glimpses of men climbing the masts and survivors in the water, but this camera setup is the only one concentrating on the process of getting people offboard.

At first we’re looking down the row of boats, but, as you can tell from my top image, we can’t see much of anything–mostly a man in a nightshirt grabbing the hull of a lifeboat. Then, as the boat is lowered and he has to pull back, we get to see a lot more. Into the slot formed by the lifeboat supports, crisscrossed by ropes and rigging, slip faces and bits of bodies. A woman stoops, a man in silhouette shouts. Meanwhile, a dark-haired woman leans over the railing.

While our young man in the nightshirt sways precariously, the boat continues to descend and we can see even further down the row of lifeboats. A woman in the middle distance calls out. The woman at the railing has started to crawl down the side of the ship.

Now, in the depth of the shot, people are seen trying in vain to pile into the boats. Abruptly, a man on a rope swings into the shot.

The boats are edging away from the ship’s hull–a slight gap emerges in the distance–but we can see passengers still shoving to try to board them.

It’s over for these people. The lifeboats descend, the boy in the nightshirt is still stranded on the side, and the woman who has climbed down beside him vainly stretches out her arm. (See below.)

A new video essay from Flavorpill offers you “135 shots that restore your faith in cinema.” It’s mostly a collection of purty pitchers laced with emblematic moments from classics. But probably you, like me the day before yesterday, haven’t seen Topi Grigi, so my images offer no cosy film-nerd nostalgia. And compared to the Hallmark-Cards aesthetic on display in most of the video essay’s clips, this shot is pretty messy.

But it engages your vision in a dynamic way. It coaxes you to watch a process, in all its scrambling disorder, along a line of sight that emerges, gradually, as uncannily precise. Desperate faces and gestures cascade through a rigid geometry–frames within frames, receding arches like ribbing in a vault, taut diagonals slicing across the frame. Would I trade this concise, rousing, remorseless stream of images for the last forty minutes of Titanic? Yes.

Joseph North offers an admirably detailed chronology and contextualization of the series in his 2011 Masters Thesis, Emilio Ghione and the Mask of Za La Mort. It’s available as a pdf here. Thanks as well to Edward Branigan for alerting me to the Flavorpill video.

Looking different today?

Johan (1921).

DB here:

Earlier this month Manohla Dargis wrote a New York Times article on how we watch, or should watch, films that some audiences consider slow and boring. She suggested that appreciating such films requires us to cultivate fresh ways of seeing. Her article and my interests coincide on this matter, so I wrote an entry developing some ideas about viewing strategies and skills. This piece also, happily, brought new readers to Tim Smith’s experiment in tracking viewers’ scanning of a scene in There Will Be Blood.

Today I explore another angle on the problem of how to watch movies that aren’t the normal fare. But this time what’s abnormal for us was once normal for everybody. I look at the pictorial possibilities that emerged in the 1910s. Those possibilities are of interest if we want to fully understand film history, but they offer some mysteries as well. If viewing movies involves skills, did people a century ago have the ones we have? Or did they employ different viewing habits, ones that we have to learn?

Editing, your imaginary friend

I write from my annual research trip to the Royal Film Archive of Belgium, now known as the Cinematek. For some years, I’ve been looking into feature filmmaking of the 1910s. On every visit I’ve found rich material, movies off the beaten path that give me a sense of the immense creativity of that early period. (See the bottom of this post for links.) The official classics of these years, by Chaplin and Griffith and Fairbanks and Bauer and Gance and Sjõström and Feuillade, remain remarkable, and Kristin’s latest entry makes a case that Alberto Capellani belongs among this heroic company. But you can also find extraordinary moments in ordinary movies. Even the most banal film has something to teach me about what choices faced the era’s filmmakers.

One of those teachable elements involves the ways in which directors guide our attention. We know that editing serves to shift our attention from one part of a scene to another, but so does judicious staging. This is one of the great lessons of the cinema of the 1910s. Watching films from that period convinced me that the craftsmanship of Anderson in There Will Be Blood, and of other directors reliant on long-take ensemble staging, has deep roots in filmmaking tradition. But the golden age of cinematic staging was relatively brief, and it was eclipsed by an approach based largely on editing. That approach is, essentially, still with us.

Let’s start by appreciating the technique that became most prominent. By the late 1910s, Hollywood filmmakers had more or less perfected what we’ve come to call the classic continuity editing system. The camera could penetrate the most intimate exchange, breaking it up into intelligible bits. Here, in a minor Metro film called False Evidence (1919), Madelon tries to persuade her father that she, not her boyfriend, is responsible for a crime.

After giving us father and daughter close together in profile, the camera has somehow squirmed in between them, showing each one in a tight 3/4 view. Or rather, the cutting has forced the staging to pull the characters a bit apart so that each one can have a frame to him- or herself. Spatial plausibility gives way to dramatic urgency; what we care about are clear views of their emotional responses. As long as the spatial relations remain clear, they can be just approximately consistent.

For a little more finesse, we can look–as usual–to Rio Jim. William S. Hart’s films are among the most visually elegant and ambitious of this period, and even his less-known items seldom disappoint. John Petticoats (1919) gives us “Hardwood” John Haynes, a rough-edged logger who finds he has inherited a New Orleans dressmaking shop. His comic introduction to the place, in the company of a new friend he’s made, uses editing to tease us. The two gents come in, with John bewildered by a feminine world he’s never known. They pause before a model sashaying on the stage, and when she pauses, she’s blocked by the Judge’s body.

We’re left without the revelation of her appearance, but when her dresser comes forward to peel off her wrap, we cut, in effect, “through” the Judge to get a clear view of the disrobing. The blocked shot teased us, but the cut pays us off.

Now that the model bares a lot more than before, the biggest tease begins. How will John react? The answer is given in the next shot, a nearly 180-degree shift from the earlier framing of the men that incorporates a mirror in the background to keep the model onscreen.

Thanks to a cut, action and reaction are given in the same shot–in fact in the same zone of the frame, the center.

A pass, a pat, a squeeze

Fabiola (1918).

Many European directors were moving in the same direction as Lambert Hillyer in John Petticoats. Although they might not use as many shots or as many different angles as their American counterparts, they were confidently breaking their scenes up into closer views, often through axial cuts that take us straight into or out of the action, along the lens axis.

Take Enrico Guazzoni’s Fabiola (1918), henceforth known to me as Fabulosa. Normally I consider the Roman oppression of Christianity one of the least fertile topics for a good movie, but Fabiola proves me wrong. For one thing, the title names a rather unpleasant woman who barely figures in the action until the climax. For another, Guazzoni proves an adept filmmaker. I was struck by those immense sets that distinguish the Italian costume drama, the dazzling lighting (see above), and the skilful editing.

Our introduction to Fabiola comes as she sits disdainfully in her household, attended by servants. After a long shot showing off the set, an axial cut takes us closer to her.

She turns as her tardy servant Sira comes in. Having stretched her elegant neck, Fabiola tips her head forward slightly, in a bob of disdain.

Another axial cut takes us still closer to her. And in a few frames her gesture, at once haughty and angry, is repeated. (The streak across the first image below is the splice, so this is the very first frame of the next shot.)

This, I think, is no mistake. The matches on action elsewhere in the film are quite precise, and indeed earlier Italian films have shown that directors used this device skilfully. Guazzoni wanted to stress Fabiola’s head movement, and he used the same tactic, the overlapped action match, that some Americans would use and that many Soviet directors drew on later. This slight accentuation of Fabiola’s gesture is a vivid way to introduce the character, caught in a characteristically scowling moment. Very soon, in a fit of pique she’ll jab Sira with a hatpin.

On the whole, keeping the setups close to the camera axis is the default value in Fabiola. For the Americans, though, cutting made the camera almost ubiquitous. A year after John Petticoats, O’Malley of the Mounted (1920), lets Lambert Hillyer again resort to intelligible shifts of setups. O’Malley, played by Hart, has gone undercover to track a killer. Posing as a robber, he has joined an outlaw gang, but they’ve discovered he’s betrayed them and plan to hang him at sunup. He’s lashed to a tree and guarded by his enemy, the brutal Big Judson. But Rose Lanier, who has drifted along with the gang, is going to help O’Malley escape. The cutting will show us exactly how she does it, and why.

Rose interposes herself between Big and O’Malley, chatting up the thug. A cut of about 180 degrees takes us to the opposite side of the tree and shows her slipping a knife toward O’Malley’s hand. We’re so familiar with this sort of insert that we’re likely to forget that once it was fresh.

O’Malley starts, then shifts his gaze toward Big.

Then comes a simple, remarkable shot. Rose slips the knife to O’Malley. Then she pats his hand. Then she gives it a squeeze.

Mystery and charm of the American cinema, as Godard would say: a single cut-in of hands can give us a lot. First there’s the narrative information (I’m passing you the knife), then Rose’s expression of support (Good luck!), capped by a burst of affection (I love you). The whole thing takes less time than I’ve used to tell it. Surely this ability to invest plot-driven detail shots with heartfelt emotion helped American cinema conquer the world. I’m tempted to say that we could sum up of the power of Hollywood, in its laconic prime, with that formula: the pass, the pat, the squeeze.

This shot is as compact in its expression as the previous one. It’s impossible to capture here all the emotions that flit across O’Malley’s face: hope of eluding death, realization that Rose loves him, anxiety that surviving will make him choose between love and duty. Rose’s brother is the killer he’s been tracking, and in a perversely honorable way O’Malley had looked forward to being hanged. That would have spared him arresting the boy. Now he must live, enforce the law, and lose the woman who has saved him.

I saw some European films that absorbed such continuity tactics quite deeply. Above all, Mauritz Stiller’s Song of the Scarlet Flower (Sangen om den Eldroda Blomman, 1919) and Johan (1921) relied heavily on analytical editing in the American fashion, including angled shot/ reverse shot. As in Fabiola, some of the discontinuous cuts have their own logic. I wish I had time to explore those Stiller films in more detail–particularly their use of turbulent rivers as dynamic plot elements, not mere landscapes. Maybe in some future entry….

Four-quadrant style

Before they adopted the analytical editing characteristic of American cinema, directors were still able to guide our attention. The so-called “tableau” style, about which I’ve waxed enthusiastic on this site before, became a rich tradition in the 1910s. Editing within the scene is minimized. (Apparently most European directors didn’t consider it a creative option in its own right until later in the decade.) The drama is carried by performance and ensemble staging. Relying on movement, acting, and composition, the director controls where we look and when we look at it

To take a straightforward example, consider the rather ordinary melodrama Le Calvaire de Mignon (Mignon’s Calvary, 1917). The scheming and dissolute Dénis de Kerouan wants to wreak misery on his brother Robert. While Robert is out of the country, Dénis hires a forger to fabricate a letter indicating that Robert has a mistress. Dénis leaves the letter on the desk for Robert’s wife to find.

Dénis has exited through the central entryway, and into the empty study comes Robert’s wife. She discovers the letter.

She moves to the left foreground and starts examining it. At this point Dénis’ face peeps out from behind the central curtain. The director makes it easy for us to notice him because nothing else is happening in the set, and Denis’ face is rather close to the wife’s. It’s almost as if he’s looking over her shoulder.

Once we register Dénis’ presence, the director can proceed to balance the shot. All that empty real estate on the right of the frame asks to be filled, and that’s what happens.

When the wife reads the damning letter, she collapses rightward into the chair, just as Dénis rushes forward to take charge of the situation.

This move exemplifies the staging technique known as the Cross, which motivates the switching of characters’ positions in the frame.

Simple as it is, this portion of the prologue of Le Calvaire de Mignon shows how, without cutting, a director can steer us to one or another zone of the shot through such cues as faces, centering, proximity to points of emphasis, and movement. Something similar happens in one, more striking moment of another fairly unexceptional movie from the period.

Nobody will claim Der Stoltz der Firma (The Boss of the Firm, 1914) is a masterpiece, or its director Carl Wilhelm is a master. It’s one of the many comedies in which Ernst Lubitsch starred before becoming a director. Here he’s Siegismund, a bumbling young provincial with more aspirations than abilities, who simply lucks into marrying the boss’s daughter. On the way to the happy ending, he wins the patronage of a fashion designer, Lilly, whose husband finds her flirtation with the young parvenu none too innocent.

Wilhelm’s use of the tableau approach isn’t especially dynamic in most of the film, but there’s one flashy scene. Wilhelm gets us to watch a very small, tight area of the frame and then gently swings our attention to a wider swath of action. As usual, everything depends on a sort of task-commitment on our part: Watch what’s likely to forward or enrich the ongoing narrative.

Lilly lures Siegismund into a changing room, with the composition showing him reflected in a mirror behind her. This sets up an item of setting that will be central to the scene.

Once inside, he coyly presents her with a flower and they draw close together. Since we tend to concentrate on faces, the small area encompassing their two profiles is likely to draw our attention. Nonetheless, the shot is notably unbalanced, as if anticipating something coming in from the right side.

Abruptly Siegismund and Lilly draw apart, and the space between them, in the mirror, is filled by the face of Lilly’s husband, coming through the curtain.

I’d bet that a Tim Smith experiment would find that nearly every spectator is already watching this small zone in the upper left quadrant of the shot. Faces, especially frontally positioned ones, command our notice, and thanks to the mirror we here have three of them. Moreover, movement is an attention-getter too, and all three faces are in motion. Mr. Maas’s face, in fact, gets notably bigger and clearer. His wrathful expression is another reason to watch him.

The husband’s body enters to fill the frame, then presses into the center of the shot, blotting out Lilly as he faces down Siegismund.

Now the director controls the speed of our gaze quite precisely. Maas slowly rotates, forcing Siegismund to swing from left to right, as if he were attached to the bigger man by a rod. This yields, again, that nice sense of refreshing the frame that we always get from a Cross.

Siegismund collapses into the lower right of the frame, flinching from the fight that’s about to start. Lilly soon shoves aside her husband’s chastisement and melodramatically tells him to leave. “We’re divorcing!” the following intertitle says.

Mr. Maas takes it in stride, shrugging and spreading his arms. He leaves, and thanks to the helpful mirror we can see him chortling as he glances back and passes through the curtain.

If we hadn’t already noticed Siegismund cowering behind Lilly in the lower right quadrant, we will now. Lilly angrily flounces to our left (the Cross again). Siegismund rises to explain he hadn’t meant to cause a rift in the marriage.

We’re back to something like the initial setup, but now with Siegismund centered, the couple further apart, and a less unbalanced frame. The drama, which now consists of Lilly inviting him to tea tomorrow, can proceed from here.

A different way of seeing?

Tom Tom the Piper’s Son (1905).

We’ve become used to editing-driven storytelling, and I’m convinced that we can learn to notice the staging niceties of the tableau alternative. But what if early filmmakers explored some other ways of looking that are far more unfamiliar to us today?

Noël Burch, in his 1990 book Life to Those Shadows, argued that in the first dozen years or so of cinema, movies solicited viewing skills that we lack today. He suggested that early filmmakers often refused to center figures and crammed their frames with so much activity that to our eyes the shots look confused and disorganized. In Tom, Tom, the Piper’s Son (1905), Burch notes, the bustle of the fair, the reliance on an extreme long shot, and the absence of any cutting make the central event, Tom’s swiping of the pig, difficult to catch. In the frame surmounting this section, Tom is making off with the pig in an area just right of center, but the antics of the clown and the response of the crowd may well distract us from the main action.

The result, says Burch, is a mode of filmmaking that demanded

a topographical reading by the spectator, a reading that could gather signs from all corners of the screen in their quasi-simultaneity, often without very clear or distinctive indices immediately appearing to hierarchise them, to bring to the fore “what counts,” to relegate to the background “what doesn’t count” (p. 154).

Later developments linearized this field of competing attractions, creating a smooth narrative flow “harnessing the spectator’s eye.” Among these developments were the presence of a lecturer at many screenings (telling people what to watch) and, of course, the growth of the continuity editing system. But Burch suggests that the “primitive mode” hung on until about 1914.

A famous example is a shot from Griffith’s Musketeers of Pig Alley (1912). The gangster has lured the Little Lady (Lillian Gish) into a back room and distracts her with a photograph while he tries to dope her drink, in a precursor of date-rape drugging. But the Snapper Kid, another gangster, has been keeping an eye on her and follows. As the gangster starts to pour the drug out, the Kid’s entry is presaged by a whiff of cigarette smoke.

At the crucial moment, we have three things to notice: the Little Lady’s obliviousness, the gangster’s pouring the drug, and the full entrance of the Snapper Kid.

Today’s director would likely resort to editing that shows the doping, then the Kid arriving, then the doping again, and leaving us to infer a vague sense that they’re happening at the same time. Griffith’s choice gives us genuine simultaneity, but at a cost. Two cues compete for our attention: central composition for the drink, major motion on the edge for the Kid’s entry. In my experience, viewers tend to notice the appearance of the Kid, but to miss the business with the drink. (Another passage for Tim Smith to test!) By today’s standards, Griffith has failed as a director, but Burch’s view suggests that 1912 viewers, more sensitive to “all-over” composition, could have registered both actions, perhaps by rapidly scanning back and forth.

During my trip I found a fascinating example of this issue, as well as an apt counterexample. Both involve daggers.

In Maman Poupée (1919), a remarkable Italian film directed by Carmine Gallone, a devoted, somewhat infantile wife learns of her husband’s affair with a society woman. Susetta confronts the mistress and begs her to break off the affair. The woman laughs in her face. What happens next is given in several shots, mostly through axial cuts.

The linear editing, as Burch indicates, lays everything out for us step by step. The close-ups accentuate what is important at each moment: Susetta seizing the dagger, stabbing her rival, and–in a remarkably modern-looking extreme close-up–registering her horror at what she has done.

Two years before, Marcel Simon, the (Belgian!) director of Calvaire de Mignon, handled a similar situation rather differently. The diabolical Dénis, whom we met earlier, has succeeded in destroying his brother’s life. It remains only for him to force Robert’s niece Mignon to marry the Algerian Emir Kalid. Kalid is at first humble, beseeching Mignon to become his bride, but then he gets rough. We might note already that Mignon, while fairly near the camera, hovers close to the left frame edge.

In their tussle, Mignon snatches something from Kalid’s waistband and flings him far away to the right.

What’s up? Mignon has grabbed the Emir’s dagger and stands poised with it pressed to her heart. But we haven’t been able to see that dagger very clearly (no cut-in close-up here, as in Maman Poupée) and she’s returned to her position far off-center. It’s likely that a viewer today wouldn’t understand that she’s holding the men at bay by threatening suicide. Would a 1917 viewer be as uncertain? Would the situation, plus her posture and the men’s hesitation, be enough to get the point across?

Moreover, this moment goes by very quickly. Scarcely has Mignon struck her pose when her true love, René, bursts in behind her–frontal, fairly centered, and moving fast. Meanwhile, Dénis is sneaking up on her, hugging the left frame. Mignon makes a break for René, dropping the still almost indiscernible dagger.

While Mignon and Rene embrace in the right rear doorway, blocked from our view by Kalid, Dénis stoops over. It’s a timely adjustment, giving us full view of the benevolent Le Maire sweeping into the room.

As the two men confront one another–the climax of the scene–director Simon has the effrontery to let Dénis steal the show. He picks up the dagger, which now can be seen more or less plainly, weighs it in his hand, and looks out for a brief, pondering moment.

We seem to have a late example of the Snapper Kid Effect, in which important actions compete for our attention. Is it clumsy direction to perch Mignon on the frame edge as René rushes in, and to let Dénis recover the dagger while we’re supposed to concentrate on the face-off between the two powerful men? Or would audiences have tracked all the strands of action and enjoyed their simultaneity?

On this site and elsewhere, I’ve assumed that directors in the 1910s structured their compositions for what Charles Barr calls “gradation of emphasis,” a fluid pattern of primary and secondary points of attention. I’ve argued as well that Burch exaggerates the decentered, nonlinear compositions of even the earliest years. Many of the films staged by Lumière cameramen are designed cogently, and so are many films from the 1900s. (Tom, Tom might be the exception rather than the norm.) Yet every so often, you get a later case, like Musketeers of Pig Alley or Le Calvaire de Mignon, that suggests that some viewers might have been more adept at tracking simultaneous events than we are.

A still broader question remains. Let’s assume that people were able to follow and enjoy films in the tableau style, even when that style pushed toward illegibility. What enabled people to adapt, and so quickly, to continuity-based movies? Some scholars and filmmakers argue that continuity editing achieved its power and worldwide acceptance because it mimics our natural mode of perception. At any moment, we’re concentrating on just a small portion of our surroundings, and this is like what editing does for us in a scene. On the other side, Burch and others would argue that continuity filmmaking is only one style among others, with no special purchase on our normal proclivities. On this view, classical continuity’s apparent naturalness hides all the artifice that goes into it, and this concealment makes its work somewhat insidious. I’ve offered some thoughts on this problem elsewhere, but I bet I tackle it again on this site some time.

In any case, we need to study films that seem odd or difficult, whether they’re recent or from the distant past. We’re guaranteed to find some striking and unpredictable things that provoke us into thinking. That’s one of the pleasures of exploring the history of film as an art.

For earlier studies of the tableau style on this site, see this entry on Bauer, this one on 1913 films, this one on Feuillade, and this one on Danish classics. This entry discusses the emergence of Hollywood-style continuity, and this one explores the exemplary editing in William S. Hart films. I go into more detail in two books, On the History of Film Style (chapters four and six) and Figures Traced in Light (chapter two) and in the essay, “Convention, Construction, and Cinematic Vision” in Poetics of Cinema. The last-named piece tries to stake out a middle position on the “naturalness” of continuity editing. Kristin has analyzed Alberto Capellani’s films as instances of the tableau trend, last year here and just last week here. She also weighs in on the debate about whether viewers of his time were better prepared to grasp the action than we are. More generally, Capellani’s career exemplifies the major and swift stylistic changes of the 1910s. When he went to America, he became pretty adept at the emerging continuity style, as the Nazimova vehicle The Red Lantern (1919) indicates. Of course that’s got some striking single images too.

The Red Lantern (1919).

ROW, take a bow

Of Love and Other Demons.

Kristin here:

There are dozens of American films playing at the Vancouver International Film Festival this year, but the vast majority of them are documentaries. Once again the Rest of the World (ROW) gets its turn. David has started by handling a group of Asian films (one of the festival’s specialities), and I’ve got films from three continents to describe.

Morgen (Romania; dir. Marian Crisan, 2010)

Morgen opens with the camera following the hero, Nelu, riding his motorcycle toward a border checkpoint. The border guards question him and discover that he’s been fishing and caught a large carp. One guard is inclined to let him pass, but the stricter one insists that he can’t take it across. We may think that this guard wants the fish for himself, but when Nelu finally empties his bucket into the gutter, the guards retire into their office and the fish is left to flap pathetically as Nelu rides across the border.

It’s a simple, obvious way to set up the absurdity and arbitrariness of border controls within the European Union, but it also sets up the character of the two guards, who will figure later when a more important border-crossing is attempted.

A security guard at a local grocery store, Nelu lives with her termagant wife in a modest farmhouse near the Hungarian border. During one of his regular fishing trips, he spots a forlorn Turkish refugee hiding from the border police. He takes the man home. Although the Turk’s dialogue isn’t subtitled, he mentions Germany often enough for Nelu and us to grasp where the man is heading. Not having a clue about how to help, Nelu hides the Turk in his cellar, and despite the wife’s objections, he gradually becomes a sort of handyman around the place. Nelu keeps telling him, “Morgen” (“tomorrow”) suggesting that he vaguely hopes to do something eventually.

Virtually every scene occupies a single take, some long, some not. But these aren’t the deliberately lugubrious shots of a Béla Tarr. In its quiet way, Morgen is a comedy, and an entertaining one. Nelu’s passivity presents the slowly growing friendship between him and the Turk without the film tipping over into sentimentality, and there is genuine suspense in the scenes of threatened encounters with the border police and guards. It’s a charming film, reminiscent of some of the Czech New Wave comedies of the 1960s.

12 Angry Lebanese: The Documentary (Lebanon; dir. Zeina Daccache, 2009)

The film’s subtitle is intended to differentiate it from a play of the same name that was produced within the largest prison in Lebanon, starring a group of prisoners. In the United States the director, Leina Daccache, studied drama as a method of prisoner habilitation. She managed to get funding to try the first ever use of this method in Lebanon, though there followed a year of negotiations before government officials allowed the experiment. The  program was to include a loose adaptation of the American play 12 Angry Men, as well as some songs and monologues by the prisoners. Eight soldout performances were eventually put on, attended by government ministers and members of society.

program was to include a loose adaptation of the American play 12 Angry Men, as well as some songs and monologues by the prisoners. Eight soldout performances were eventually put on, attended by government ministers and members of society.

The process of casting and rehearsals took fifteen months, and Dacchache documented the process with a cinematographer shooting digital video. There are atmospheric shots of the prison, scenes of the rehearsal and premiere performances, and interviews with the prisoners who play the lead roles. The resulting images are necessarily not of high photographic quality, but the intrinsic drama of the situation more than makes up for that.

Although 45 prisoners were involved in the performances, Daccache wisely concentrates on the central dozen, composed of several murderers, some drug dealers, and a rapist. Even in the early interviews, before rehearsals have progressed very far, all are remarkably articulate and thoughtful about their own lives and how they ended up in prison. (Presumably they were chosen because they could speak so revealingly.) By the end, they realize that they have learned all the things they were deprived of during their early years, most notably how to function as a group and work toward a goal beyond their own wants.

The film creates a moving and convincing image of the effects art can have in changing the lives of prisoners thought to be beyond rehabilitation. It’s a rare documentary that has an immediate positive effect on society. In this case, there had been a law providing for early release for prisoners on the books in Lebanon for several years. As Daccache revealed in a Q&A after the film, that law was never put into practice until after the successful run of the play.

Of Love and Other Demons (Costa Rica/Colombia; dir. Hilda Hidalgo, 2010)

Filmmaking on a sophisticated level continues to spread through Latin America. Hidalgo’s adaptation of Gabriel García Márquez’s novella seems to have been shot in Costa Rica, with financing and other technical work done in Colombia.

The story is relatively simple. The teenage daughter of a local nobleman in colonial Cartagena is bitten by a rabid dog. It’s not clear whether she has contracted the disease, but she is taken to a local nunnery and locked away in a cell for observation. Somehow the diagnosis is changed to demonic possession, mainly because the girl has been raised by her family’s black slaves and has been steeped in their native, highly non-Catholic beliefs. A young, philosophically minded priest is sent to exorcize her but ends up falling in love with her instead.

In contrast to the slapdash editing so common in contemporary Hollywood films, it’s a pleasure to see a film where every shot has been intelligently planned. The Variety review compares cinematographer Marcelo Camorino’s lighting to Caravaggio paintings, an apt parallel. The heroine’s implausibly dense, waist-length red curls are lovingly dwelt upon, as in the shot illustrated at the top of this entry. The sense of magical realism emerges most powerfully in a dazzling sequence in which the priests watch a solar eclipse. A moon far larger than it would normally appear passes across an equally huge sun, creating a fiery corona that hovers above the open sea (see below).

Microphone (Egypt; dir. Ahmad Abdalla, 2010)

Ahmad Abdalla, whose first feature Heliopolis we blogged about last year, is back with his second. Microphone is much more polished, reflecting a longer shooting time and perhaps a bigger budget. The same lead actor, Khaled Abol Naga, returns as Khaled, a young man returning to his native Alexandria after seven years in the United States. Finding that the girl he had hoped to marry has decided to go abroad to do her Ph.D., he sets out to help set up a studio in a warehouse. Gradually he gets drawn into the more popular goings-on in the working-class districts, notably rap music, skateboarding, and graffiti art. After a hypocritical government arts bureaucrat promises funding and then reneges, Khaled sets out to stage a concert in the open air, only to be confronted by Islamic and police opposition.

While Heliopolis simply followed a set of disparate characters around the upscale Cairo suburb, Microphone has a more ambitious structure, flashing back to stages in Khaled’s disillusioning reunion with his ex-girlfriend–flashbacks that are presented out of order within the ongoing scenes of his growing interest in street art. The result has the sophistication of a modern festival film.

The film presents a grim take on government repression and censorship. Abdalla, on hand to answer questions, told us that we had seen the full version, which he fully expects will be cut by the Egyptian authorities. Even  though he shows the young street artists in a sympathetic light throughout, Abdalla does not avoid the fact that their work is wholly positive. There is a motif of Khaled opening his shutters each morning to a view of an aging yellow stucco building across the way; one morning he opens again to find the façade covered with a giant graffiti image.

though he shows the young street artists in a sympathetic light throughout, Abdalla does not avoid the fact that their work is wholly positive. There is a motif of Khaled opening his shutters each morning to a view of an aging yellow stucco building across the way; one morning he opens again to find the façade covered with a giant graffiti image.

Indeed, one audience member, a young man from Alexandria, objected to the portrayal of his beautiful home city as ugly, since the story is set mostly in poorer neighborhoods. Abdalla defended the approach, saying that the film is intended to portray a certain arena of life in the city realistically, with the incidents in the film being derived from stories recounted to him by the actual young artists who played themselves.

The film’s criticism of the Egyptian government may seem rather tame by western standards. Yet a telling change in the ending reveals how current are its concerns. There is a street vendor selling pop-music cassettes out of a cardboard box who returns at intervals as a motif, though he has little to do with the story. The film was to have had an upbeat ending involving the vendor. But in June, when the filming was still going on, the beating death of Khaled Said by two policemen outside an internet cafe in Alexandria took place. The filmmakers altered their ending, with police chasing the cassette vendor and starting to beat him. (The trial of the real-life policemen is ongoing and has every appearance of being a sham.)

The Man Who Will Come (Italy; dir. Giorgio Diritti, 2009)

This film dramatizes a set of massacres of villagers perpetrated by Nazi soldiers in the region around Bologna in 1944 in response to the people’s support of partisan troops. It’s a tale told through the eyes of Martina, a girl of about 9 who has been mute since her newborn brother died in her arms. (No points for guessing whether she regains speech by the end.) Since the main peasant family to which Martina belongs is fictional, there was no necessity to make her mute, and unfortunately the result is that she has very little personality. She is shown being bullied by some boys early on, which presumably is intended to make us sympathize more with her, though the choice of a pretty little girl as the point-of-view figure entails a pretty automatic sympathy on the audience’s part.

The film is largely episodic, with the life of the central peasant family and their neighbors being vividly conveyed as we see them at their tasks. At intervals, Nazis are seen near the village, and the partisans recruit young men and have some early successes. But since Martina understands little of what goes on around her, she has no particular goal, though eventually she gains one as the Germans begin the massacre and she is left to save another newborn brother. I found it difficult to keep track of the lengthy scene of the rounding up of the peasants and their executions in various venues. One group is taken to a chapel in a graveyard to be killed, another is killed by the church, and so on, but it is difficult to tell one group from another or to get a sense of how many peasants were slaughtered. (The original total was somewhere around 750 to 800.)

Overall the cinematography conveys the setting well, both the hilly, wooded landscapes and the ancient stone farmhouses. There’s a very effective scene where the townspeople take refuge in a church and Martina’s older sister runs back and forth from the bell-tower, reporting the fighting below, which we see only from far away, as she does. In fact, this sister is a more engaging character than Martina, and would have made a better point-of-view figure. Another gripping scene comes when she, seriously wounded in the massacre, is suddenly pulled out of the pile of bodies and given first aid by a Nazi officer. She’s mystified as to why he’s doing this, though we hear him tell another soldier that she reminds him of his wife. It may seem as if the insanity of war would be more effectively conveyed through a thoroughly naive character’s eyes, but at least in this case, somehow that doesn’t work.

Of Love and Other Demons.

Paris-Berlin-Brussels express

Doktor Satansohn.

Our trip to Europe has come to an end, and so we finish with a post scanning some highlights.

The magic lantern learns new tricks

DB here:

What am I seeing? Many avant-garde films pose this question. Mainstream fiction film and documentary cinema have mostly relied on the idea that the image should be recognizable as “what it is.” But one strain of experimental film has worked to delay or even prevent us from making out what’s in front of the camera.

Sometimes we lose our bearings only briefly, as when we eventually identify pot lids in Ballet Mécanique or bits of sunlit linoleum in Brakhage films. Sometimes language points out what’s really there. The titles of Joris Ivens’ Rain and the Eames’ Blacktop: The Washing of a School Play Yard allow us to enjoy the ways that ordinary sights can yield unexpected abstraction. Sometimes we toggle back and forth, as when in Ken Jacobs’ Tom, Tom, the Piper’s Son recognizable human figures, however grainy, jump into sheer blotchiness and then back into something like legibility. But other times we can’t ever tell what we’re seeing. Brakhage’s Fire of Waters offers one of the best examples I know, with its jagged bursts of light in a smoky void.

What am I seeing? The uncertainty was doubled during my visit to Ken Jacobs’ Nervous Magic Lantern performance at the Cinémathèque Française. I say “doubled” because at least with Fire of Waters and Tom, Tom I knew I was watching a film. With this display, What am I seeing? started as a question about the format itself. Was it a film, a video, or something else?

Then the question became the customary one. Off-white textures—pebbly, dribbly, stalagmite-like—swim in and out of focus. Some are viscous and globular, some are like tangled foliage. They seem to spiral, but actually (I put up a finger to measure) they barely move. The effect of movement is given by pulsations of pure black, breaking the lyrical effect of the surfaces with a harshness that becomes aggressive. Aggressive as well is the soundtrack, blocks of sound from subway platforms and traffic and kitsch Latin percussion, all played at high volume. The surfaces just keep shifting and not shifting, sort of rotating while jabbing out at us, lovely and anxiety-inducing at the same time.

At the end of the performance, people crowded around the cardboard booth in the middle of the theatre. As Ken and Flo Jacobs packed up, they showed how they had generated the effects. What had I been seeing? Neither a film nor a video but a true magic-lantern display, assembled on the spot. But what had I been seeing? Something created with home-made equipment of a startling simplicity. (Strapping tape was involved.) Our magicians explained their tricks, like magic-lantern operators of earlier centuries explaining the science behind their shows. But I think it’s best that you not know until after you have a chance to see what they create.

In earlier entries (here and here) Kristin and I have praised Jacobs’ films for showing how very slight adjustments in technique or technology can create disturbing cinematic illusions. In this vein, the first item on the Cinémathèque program, a video called Gift of Fire, turned Louis Le Prince’s brief 1888 street scene into a 3D movie. (The homage was appropriate because Le Prince experimented with multiple-lens cameras.) The Nervous Magic Lantern performance generated a different sort of illusion, one conjuring up micro-landscapes and otherworldly vortices. In all, Jacobs makes us realize how many evocative effects are still to be discovered by tinkering with images thrown on a screen.

Detour to Berlin

KT here:

As David mentioned in last week’s entry, I took a week in the middle of our visit to Europe for research at the Ägyptisches Museum in Berlin. The staff there welcomed me into their storerooms, and I spent the days looking at fragments and the records of their discovery and the nights downloading and backing up my photos. No time for filmgoing. The most I managed was a trip to the well-stocked arts bookshop Bücherbogen, which has one of the best selections of film books to be found in Germany. Our old friend, experimental filmmaker Carlos Bustamente, met me there, and we had a quick cup of tea–most welcome on a cold morning when the results of the biggest snowfall in decades were still blanketing many sidewalks and roads.

I did note one film-related phenomenon, however. Every day I took the S-Bahn from Savignyplatz to Friedrichstrasse. The tracks pass directly across the street from the Theater des Westens (that is, the western part of Berlin). It was playing Der Schuh des Manitu, a musical version of the  highly successful 2001 German film of the same name. (I hope the publicity photo at the left was taken in warmer weather than I experienced.) I mentioned the film here, in reference to the fact that every major producing country, and some minor ones as well, turn out their own local comedies, films that don’t travel well but are very popular locally.

highly successful 2001 German film of the same name. (I hope the publicity photo at the left was taken in warmer weather than I experienced.) I mentioned the film here, in reference to the fact that every major producing country, and some minor ones as well, turn out their own local comedies, films that don’t travel well but are very popular locally.

By now it’s a familiar phenomenon in the U.S. for successful Hollywood films to be turned into stage musicals. It wasn’t always so. Back in the 1950s and 1960s, films were made of popular musicals, sometimes successfully, as with My Fair Lady, and sometimes not, as with Mame. But now the trend is the other way, with everything from Shrek to Hairspray getting the Broadway treatment.

It’s interesting to know that the same thing goes on abroad, though I’m not sure how prevalent such adaptations are. Der Schuh des Manitu, directed by Michael “Bully” Herbig, remains the highest grossing German film. Herbig doesn’t act in the stage play, as he did in the film, but he served as a creative advisor. The musical is a hit, having premiered on December 7, 2008 and it is expected to continue until at least the autumn of this year. There are several clips from both the film and the musical on YouTube. This one, at 8 minutes, gives a generous dose of the show. There are no subtitles.

I had only a couple of days back in Paris before we headed for Brussels for the final week of our trip. The German theme continued, since a few of the 1910s films David needed to see at the Cinematek here were German. The one I most wanted to see was Edmund Edel’s 1916 feature, Doktor Satansohn. Its main claim to fame is probably the fact that Ernst Lubitsch plays the title role. My book with Lubitsch started with his 1918 move to features, when he began to concentrate more on directing and less on acting. By 1920, with Sumurun, he appeared onscreen for the last time; being discontented with his performance as the tragic clown, he decided it was time to move behind the camera for good.

In the short films he starred in before 1918, Lubitsch often played a brash, ambitious Jewish youth, as in Der Stoltz der Firma (“The Pride of the Firm,” 1914). In Doktor Satansohn he’s a physician with a magical machine that transforms older women into beautiful young ones. We’re first introduced to a couple and the wife’s mother. When the latter makes a pass at her son-in-law and is rejected, she seeks the doctor’s help. His machine works by capturing the wife’s essence in a statuette and making the mother look like her daughter. Problem is, every time she’s about to kiss the husband, the doctor pops up with his devilish leer, visible only to the “wife.” David and I decided that the film is a comedy, though perhaps one only Germans of the day would find truly amusing. For one thing, the title character is clearly a Jewish caricature, one played to the hilt by Lubitsch. He decorates his machine with the Star of David and a Hebrew inscription (not to mention vipers and an image of Saturn).

Stylistically it’s a fairly conventional film for its day, though the black background of the doctor’s office, with its stylized youth machine and satyr-like bust, gives a hint of Expressionism to come. (See our topmost image.) Inevitably near the end there comes the moment beloved of historians of pre-World War II German cinema. The real daughter, released from her imprisonment in the statuette, confronts her double in the doctor’s waiting room. The Doppelgänger motif strikes again.

I wonder if German films actually have more Doppelgängers in them than appear in other national cinemas. Do they really reflect the disturbed soul of the nation? Or did the possibilities of filmic special effects draw moviemakers to try and multiply single figures? Georges Méliès and Buster Keaton used in-camera techniques to multiple their own figures in virtuoso displays. I recall being impressed by The Parent Trap‘s duplication of Hayley Mills when I saw it as a kid, and the whole notion of a single actor playing twins and other lookalike relations is a common enough convention. In Doktor Satanssohn, the doubled figure appears only in this one shot, and it’s the leering Lubitsch, delighted with his own nastiness, who walks off with the picture.

The 1910s, again, and still

DB again:

We saw Doktor Satansohn while I was studying staging and cutting strategies of the 1910s, thanks to the remarkable holdings of the Royal Film Archive of Belgium, also known as the Cinematek. My comments on last summer’s visit are here.

Another German film, in a choppy Russian print, vouchsafed a new glimpse of Asta Nielsen. In Totentanz (Urban Gad, 1912), she plays a guitarist-dancer who must take to the stage to support her infirm husband. She attracts the devotion of a composer, and soon she feels attracted to him. Torn between desire and duty, she snaps during a rehearsal of his latest piece, “Totentanz.” In a chilling gesture, she uses his dagger to slice her lute strings.

Soon the two are locked in a violent erotic struggle, and a stabbing ensues. In all, melodrama as ripe as one could want.

As ever, I was happy to have my hypotheses about tableau staging confirmed by several of the titles I saw. A minor French bedroom farce, Le Paradis (M. G. Leprieur, 1914 or 1915), had a brief passage of the sort of blocking and revealing we find in many films of the period. The painter Raphael Delacroix (no kidding) is pretending to be the lover of Claire Taupin to deflect the advances of randy M. Pontbichot. But Claire is actually the mistress of M. Grésillon. . . .

First, very frontal staging strings out Pontbichot, Raphael, and Claire. The older man relents in his pursuit of her.

In the vivid depth characteristic of the tableau tradition, Pontbichot withdraws. But his position accentuates that central door, which starts to open.

Most remarkably, Pontbichot ducks almost entirely behind the couple, giving pride of place to M. Grésillon’s arrival in the center of the shot.

Pontbichot slides out in time to register Grésillon’s outraged reaction to finding his mistress in another man’s arms.

Grésillon rushes to the frontal plane, furious. As ever, a thrust to the foreground creates a major spatial/ dramatic event.

Although the Le Paradis passage is ABC compared to the emotionally powerful patterns of staging we find in Ingeborg Holm (1913), it illustrates how even average films could resort to the blocking/ revealing tactic within the deep-space geometry of the tableau.

More flamboyant was Il Jockey della Morte (1915), an Italian circus film made by the Dane Alfred Lind. Its bold lighting and varied angles on the Big Top recalled the Danish films of a few years before. Halfway through, Lind launches a dazzling chase that features leaps from a tall bridge and bicycling stunts on a cable stretched across a river.

Another Italian film, this time a diva vehicle, suggests that by 1917 1923 (see below) the tableau style was already giving way had given way to scenes organized around close shots. (See below.) L’Ombra (Mario Almirante) starred Italia Almirante Manzini as a lively, trusting wife who becomes paralyzed. While her husband betrays her with her younger protégée, she gradually recovers bodily movement. Yes, a paralyzed diva seems a contradiction in terms, but one small-scale scene shows a remarkable range of emotions. Berta’s hands start twitching, one lifts up, and she stares wildly, as if it were an alien being.

In an earlier scene, Berta had asked that a mirror facing her be tipped upward so that she would never see herself sitting immobile. This shot pays off now, when the hand ascends almost magically into the bit of reflection she can see.

When the hand descends, her astonishment turns into joy. She experimentally shoves the hands together, as if asserting her control.

In the end, she kisses her hands as if they were pampered children.

Manzini runs through many more micro-emotions than I’ve indicated here, but this sample is typical of the ways in which L’Ombra avoides the long-shot choreography of only a few years before and builds a performance out of face, body, and arms in a close framing. The mirror-shot motif shows that fairly careful filmic construction was emerging at this point too.

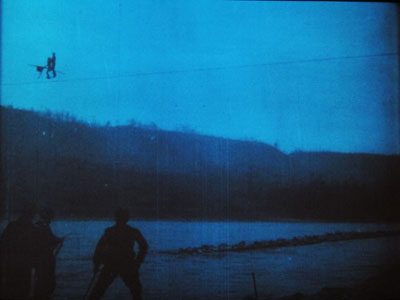

During my stay, I learned more about tinting and toning from the ever-helpful Noël Desmet. On the seldom-seen World War I drama L’Empreinte de la patrie (M. Dumeny, 1915), some images had curious oscillating patches of rusty brown. Noël explained that when Prussian Blue toning was combined with rose tinting, the chemicals eventually reacted to alter the pink cast. An example is shown at the top of this section, though the blue is more saturated in the original.

Once we get back to Madison, I’ll have to sort out all that I’ve learned from these movies. Onward and upward with the 1910s!

For more on Jacobs’ Nervous Magic Lantern, see Scott Foundas’ interview here. The Youtube clip doesn’t do the spectacle justice. If you must know something of Jacobs’ tools, the Dailymotion video from the performance I saw offers some clues. My notions about 1910s staging are laid out in On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light. You can also find several discussions in earlier entries on this site. Just execute a search on tableau.

Now is a good time to thank Noël Desmet and Marianne Winderickx, both of whom are retiring from the archive in March. The research that Kristin and I have done over the years owes an enormous lot to them, and of course to the Director of the Cinematek Gabrielle Claes.

P.S. 15 November 2013: Ivo Blom has pointed out that the version of L’Ombra I saw wasn’t from 1917 but rather from 1923. Hence the corrections above. Thanks very much to Ivo! Go here for his blog and information about his newest publication on silent Italian cinema.

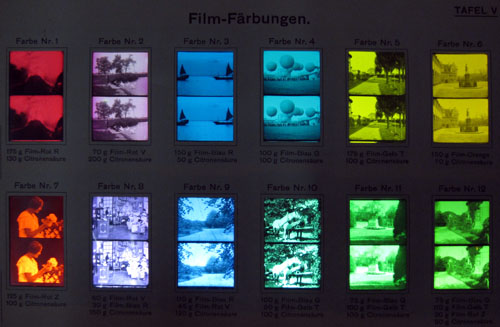

A tinting and toning sample card from the early 1920s. Courtesy Noël Desmet.