Archive for the 'National cinemas: Japan' Category

Dragons, tigers, one bear

Sawako Decides.

DB here:

As has become our habit, we’re at the Vancouver International Film Festival, gulping down movies. The perennial Dragons and Tigers collection of recent Asian film is especially ripe this year, at over forty-three features and many shorts, and of course there are several other choices, across ten venues, competing for your eyeballs. Herewith, my first dispatch from this sunny, hospitable city. Kristin will follow up soon.

A girl, a boy, and many guns

She’s completely ordinary, “below-middle,” as she proclaims. Her contribution to a conversation is always a couple of steps behind. She spends her nights watching TV and guzzling beer. She has lost five jobs and been dumped by five boyfriends. Her main relaxation seems to be colonic irrigation. But when she’s fired and her father lies dying, she returns to her hometown to take over his clam-processing factory. She brings in tow her latest paramour, a twitchy ex-toy-designer who enjoys knitting.

Such is Sawako, who has the face of an anime princess and the mind of . . . well, that’s part of the problem. Psychologically, she’s the opposite of those fast-comeback youngsters spraying American indies with quirk. She mopes in her father’s factory, absently minds her boyfriend’s daughter, shrugs off the malice of her former teen friend, and ignores gossip about why she left town in the first place. Nothing can shake her obdurate passivity. She won’t fight. With beer as her only solace, Sawako seems not the stuff of drama at all.

But drama, tradition tells us, pivots on decisions (usually bad ones). Sawako Decides surrounds a woman resigned to misfortune with a range of eccentrics who do take action, sometimes recklessly. There are the older women who work in the processing plant, the faithless boyfriend with his powder-blue sweaters, the vindictive ex-friend, the alcoholic father who rips off his IV for a fight, even a college girl doing research on toxic clams. When Sawako finally chooses to do something, she’s acting, she says, for all the “below-middle” people—that is, nearly all of us. Associated throughout with body wastes, she turns the tide: Even the feces she spreads on the family garden yield a giant watermelon. The film ends with a trim long take in which Sawako finally blows her top and finds an agreeably aggressive use for her father’s bones. Ishii Yuya’s film shows how the blankest of characters can, if treated with wary respect, yield engaging cinema.

Won Bin is probably best known to Western audiences as the scatty, tormented son in Bong Joon-ho’s Mother, but he’s become a major Korean heartthrob. I know this because of the collective gasps and shrieks that greeted moments of The Man from Nowhere, a grisly action picture by Lee Jeong-Beom. Won plays a retired government agent running a pawnshop in a seedy neighborhood. He reenters the underworld to rescue a neighbor woman’s daughter, snatched by a drug gang for a little child labor and organ-stripping. He is a Bourne-style killing machine, and he is given plenty of chance for some rousing brawls and gunplay (though most of his fighting skills can be credited to editing and blur-o-vision camerawork). Mountainous, bug-eyed, and ominously silent bad guys round out the cast. Director Lee is also shrewd enough to feed the fanbase. There are some touching moments between the girl and the hitman; she even gives him a decorative fingernail while he sleeps. The film’s pin-up image shows Won, stripped to the waist at the mirror, clipping his hair, a bloodied groin-level bandage artfully completing the ensemble. (If you can’t wait, see the end of this entry.) A limited North American release comes later this month.

Excess, two varieties

I’ve written briefly about Sono Sion’s perverse coming-of-age tale Love Exposure, and this year’s Vancouver fest brings us his latest, Cold Fish. Who would have thought that business rivalry between two tropical-fish vendors would lead to the carnage we see here? Meek Shamoto has a sexy wife and a disobedient teenage daughter. An aggressively friendly rival, Murata, owns a much bigger shop and offers to take the wayward Mitsuko under his wing. Soon Murata reveals that he plunges as voraciously into murder as he does into fish connoisseurship, and Shamato is caught up in the untidy business of human butchery.

A charnel-house of copulation and dismemberment, the film takes place in a vacuum; a police investigation comes virtually as an afterthought. Cold Fish is more linear and genre-bound than Love Exposure, but when the quiet march of Mahler’s first symphony signals the onset of dread you recall the wilder side of the earlier movie. Also carrying over is the blasphemous use of Christian iconography, associated here with slaughter and child abuse. The film is in the tradition of The Family Game and other dismantlings of Japanese domesticity. Once again, you can find as much lust and murder as you like just by looking into the nuclear family. In this case, the choice offered to the father is straightforward: be a wimp or be a brute. Sono aims to outrage, but once you know that you’re in for a bloodbath, you settle comfortably in for an engrossing exercise in splatter, Japanese-style.

At the other extreme is The Drunkard, Freddy Wong’s adaptation of Liu Yichang’s well-regarded novel about a dissolute writer. Lau wants to be the Hemingway of Hong Kong, but his addiction to alcohol and his inability to love drive him into writing film scripts, pulp fiction, and eventually pornography. The fear of selling out your artistic ideals may not strike a chord in the age of Damien Hirst, but in the 1960s, the novel’s epoch, it held sway over literary culture. Lau’s struggle is presented as an oscillation between his collaboration on a literary magazine and his grubby business dealings with movie producers and publishers. In between, and constantly, he smokes and drinks. The women along his downward path include a seventeen-year-old temptress who has read Lolita, a sincere working woman who offers him lodging and sex, and an aged landlady who thinks he’s her son. His drunken refusal to sympathize with their needs brings sorrow to nearly all and death to a couple of them.

The Drunkard is shot in an unusual style. There are almost no long shots; the framing above is about as far back as the camera gets. Nearly everything happens in medium-shot and close-up. Wong was partly making a virtue of necessity, since streets and shops of the Hong Kong of the 1960s could not be reconstructed on the film’s budget. The positive result is an unrelenting concentration on Lau and repetitive bits of his behavior–gesturing with a cigarette, pouring whisky, or fading into a blackout. From scene to scene, we’re confined to his awareness, broken by fragmentary memories of wartime Japanese invasion. Only after his binges do we learn how viciously he acted when under the influence.

This tightly circumscribed world is enhanced by shots focusing on only a curtain edge or a streaked whisky glass, while people and surroundings drown in a blur. Shot on the Red camera, The Drunkard shows that high-definition digital is perfectly capable of giving foregrounds or backgrounds a hallucinatory softness. That softness, you could argue, is a correlative for the drunkard’s vision, locked on details and oblivious to the flux of human passions around him. In its effort to render the glowing warmth of alcohol, Wong and his cinematographer Henry Chung have given digital cinema a decisively subjective turn.

Two men and a sofa

Ho Wi Ding’s Pinoy Sunday is a heartfelt, low-pressure comedy-drama that makes some telling points about cultural dislocation. Dado and Manuel are Filipino “guest workers” in Taiwan. Friends since high school, they work in a bike factory and live in the factory dormitory. In their dreams they imagine installing a lavish raspberry-bright sofa on the dorm roof where they could lounge, drink beer, and look at the stars. One day, visiting Pinoy on break, they see that very sofa abandoned on the street.

Emigrant Filipino workers fill the lower-rank jobs in many Asian countries, and I’ve seldom seen fiction films show the texture of their lives. Through Dado’s phone conversations with his family, the pain of loss comes through. He buys his daughter a Barbie for her birthday, even while he carries on an affair with an émigré woman (who herself has a husband and family back home). Manuel is on the make, but with winning naivete has a knack for picking the wrong women to idealize (hookers, policewomen). In a way, the sofa becomes the tangible emblem of not just material comfort but the men’s aspiration for a more stable life.

With something of the wistful satire of 1960s Eastern European films like Intimate Lighting or The Fireman’s Ball, Pinoy Sunday turns an anecdote into a mini-saga. (It was inspired by Polanski’s Two Men and a Wardrobe.) At the canonical turning point (circa 28:00), Manuel persuades Dado to carry the sofa back to their dorm before the gates close. The ensuing misadventures recall Laurel and Hardy, but with stronger sentiment.

Their journey reminds them they are outsiders. A TV reporter thinks they’re Malaysian. Trying to explain an accident to a cop puts them at a disadvantage. Their inability to speak Mandarin gives us a crash course in how gestures, English phrases, and situational logic are pieced together to communicate across cultures. At the height of the men’s frustration, there is a poignant musical interlude that evokes magic realism, but that moment is immediately undercut by sober reality. Yet our concern for these two resilient strivers is rewarded with a sort of happy ending.

Finally, the bear of this entry’s title is Alex Law’s Echoes of the Rainbow, the Hong Kong film that won the Crystal Bear at this year’s Berlin festival. I haven’t seen it yet but I hope eventually to pass you some words about it.

The Man from Nowhere.

The buddy system

Sweet Smell of Success.

DB here:

Many of our friends write books, and what are friends for if not occasionally to promote each other’s books? Here’s an armload of titles, most of them recently published. They’re so good that even if the authors weren’t our friends and colleagues, I’d still recommend them.

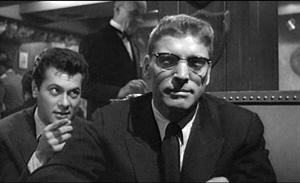

James Naremore has made major contributions to film studies since his fine monograph on Psycho, published way back in 1973. That book remains one of the most sensitive analyses of this much-discussed movie. Now he has another monograph, on the stealth classic Sweet Smell of Success. When I was coming up, Alexander Mackendrick wasn’t much appreciated, and this movie slipped under the radar. More recently it has emerged as one of the model films of the 1950s, and not just for James Wong Howe’s spectacular location cinematography. It’s a very brutal story, with Tony Curtis playing against type as venal press agent Sidney Falco and Burt Lancaster as J. J. Hunsecker, a monstrously vindictive newspaper columnist.

Jim’s book provides a scene-by-scene commentary but also more general analysis of production circumstances and directorial technique. An enlightening instance is what Mackendrick called “the ricochet”—when character A talks to character B but is aiming at character C. This allows the filmmaker great flexibility in framing and cutting, often showing C’s reactions while we hear the dialogue offscreen. In the shots surmounting this blog, Sidney is needling J. J. by asking the Senator if he approves of capital punishment. Jim’s book joins his work on Welles, Kubrick, and film noir as part of a subtle reassessment of American postwar cinema.

With the current revival of interest in André Bazin’s film theory, it’s fruitful to look again at the “classical” theoretical tradition in which he participated. “Classical” here refers to the very long period before the emergence of semiotic and psychoanalytic theories of cinema in the 1960s. The newer theories have somewhat beclouded our recognition of how imaginative and wide-ranging the old folks were. In Doubting Vision: Film and the Revelationist Tradition, Malcolm Turvey scrutinizes four thinkers who saw film as having the power to show us things beyond (or above, or below) surface reality. In the spirit of analytic philosophy, Turvey carefully lays out the positions of Béla Balázs, Jean Epstein, Siegfried Kracauer, and Dziga Vertov before asking whether their claims hold up.

With the current revival of interest in André Bazin’s film theory, it’s fruitful to look again at the “classical” theoretical tradition in which he participated. “Classical” here refers to the very long period before the emergence of semiotic and psychoanalytic theories of cinema in the 1960s. The newer theories have somewhat beclouded our recognition of how imaginative and wide-ranging the old folks were. In Doubting Vision: Film and the Revelationist Tradition, Malcolm Turvey scrutinizes four thinkers who saw film as having the power to show us things beyond (or above, or below) surface reality. In the spirit of analytic philosophy, Turvey carefully lays out the positions of Béla Balázs, Jean Epstein, Siegfried Kracauer, and Dziga Vertov before asking whether their claims hold up.

I’m not giving much away by revealing that Malcolm thinks the revelationist tendency has its problems. But his purpose isn’t simply to reject the position. He treats it as an instance of what he calls “visual skepticism,” the idea that we ought to treat our ordinary intake of the world as something suspect. This idea, Malcolm argues, is central to modernism in the visual arts. He extends his critique of visual skepticism to more recent theorists as well, notably Gilles Deleuze, and he shows how his own ideas apply to films by Hitchcock, Brakhage, and other directors. Malcolm’s book is a model of theoretical clarity and probity, and a stimulating read as well.

Skepticism of another sort is central to Carl Plantinga’s Rhetoric and Representation in Nonfiction Film. One result of semiotic theory was to question whether a film could ever adequately represent reality. If a movie is only an assembly, however complex, of conventional signs, it can’t give us access to something out there. Even a documentary, some theorists argued, had no privileged access to the real world, let alone to general truths. “Every film is a fiction film” was a refrain often heard at the time. Carl tackles this assumption head-on by carefully arguing that just because a documentary is selective, or biased, or rhetorical, that doesn’t mean that it can’t affirm true propositions about our social lives.

Like Malcolm, Carl brings a philosopher’s training in conceptual analysis to debates about the ultimate objectivity of any documentary. In adopting a position of “critical realism” opposed to skepticism, Carl examines the realistic status of images and sounds, the way documentaries are structured, and filmmakers’ use of technique. He shows, convincingly to my mind, that a documentary may offer an opinion and still be objective and reliable to a significant degree. Carl’s 1997 book went out of print before it could be published in paperback. He has enterprisingly reissued it as a print-on-demand volume, and it’s available here.

To take film theory in another direction, there’s Evolution, Literature, and Film, edited by Brian Boyd, Joseph Carroll, and Jonathan Gottschall. As a wider audience has become aware of the power of neo-Darwinian thinking, more and more scholars have been arguing that evolutionary theory can shed light on aesthetics. The most visible effort recently is Denis Dutton’s The Art Instinct.

To take film theory in another direction, there’s Evolution, Literature, and Film, edited by Brian Boyd, Joseph Carroll, and Jonathan Gottschall. As a wider audience has become aware of the power of neo-Darwinian thinking, more and more scholars have been arguing that evolutionary theory can shed light on aesthetics. The most visible effort recently is Denis Dutton’s The Art Instinct.

For some years Brian, Joe, and Jonathan have been in the forefront of this trend, with many books and articles to their credit. Their anthology pulls together broad essays on biology, evolutionary psychology, and cultural evolution before turning to art as a whole and then focusing on literature and cinema. There are also pieces displaying evolutionary interpretations of particular works, and a finale that provides examples of quantitative studies of genre, gender variation, and sexuality, including an article called “Slash Fiction and Human Mating Psychology.”

Among the film contributors are other friends like Joe Anderson, a pioneer in this domain with his 1996 book The Reality of Illusion, and Murray Smith, who provides an acute piece called “Darwin and the Directors: Film, Emotion, and the Face in the Age of Evolution.” There are also essays of mine, drawn from Poetics of Cinema. In all, this book presents a persuasive case for an empirical, broadly naturalistic approach to the arts.

By the way, the same team is involved with an annual, The Evolutionary Review, edited by Alice Andrews and Joe Carroll. Its first issue offers articles on Facebook, musical chills, women as erotic objects in film, and Art Spigelman’s In the Shadow of No Towers (by Brian Boyd).

Some books emerge from conferences, and Tom Paulus and Rob King’s Slapstick Comedy is a good instance. Based on “(Another) Slapstick Symposium,” held at the Royal Film Archive of Belgium in 2006, the anthology brings together a host of experts who look back at madcap comedy in American silent film. There are essays on particular creators—Griffith, Sennett, Fatty, and Chaplin, inevitably—as well as pieces on slapstick parodies of other movies and the genre’s relation to modernity, also inevitably. Tom Gunning offers a fine analysis of Lloyd’s Get Out and Get Under (1920), concentrating on a complex string of gags around an automobile. The collection gathers work by some of the outstanding scholars of silent film while also, of course, making you want to see these crazy movies again.

You also want to see all the movies lovingly evoked by Gary Giddins in Warning Shadows: Home Alone with Classic Cinema. As indicated in another blog entry, I find Giddins one of the best appreciative critics we’ve ever had. Any essay, indeed almost any sentence, cries out to be quoted. Here he is on Edward G. Robinson:

You also want to see all the movies lovingly evoked by Gary Giddins in Warning Shadows: Home Alone with Classic Cinema. As indicated in another blog entry, I find Giddins one of the best appreciative critics we’ve ever had. Any essay, indeed almost any sentence, cries out to be quoted. Here he is on Edward G. Robinson:

His round, thick-lipped, putty face could brighten like paternal sunshine or shut down in implacable contempt or stall with crafty desperation or pontificate with ingenuous wisdom; his short, stumpy, erect frame could sport a tailor-made as smartly as Cary Grant.

Some of the pieces in Giddins’ latest collection were designed to accompany DVDs, but they will outlast this evaporation-prone genre. Other reviews come from the New York Sun, which gave him freedom to mix and match his subjects: Young Mr. Lincoln and Lust for Life (both biopics), Lady and the Tramp and Miyazaki movies. The collection opens with Giddins’ thoughts on how changes in film exhibition, from nickelodeons to digital screens, have altered our relationship with the movies. This isn’t just nostalgia, because his survey allows him to celebrate the power of DVD to exhume forgotten titles. The standards for a film classic, he notes, “are gentler and more flexible” than those in appraising other arts. “The passing decades are a boon to the appreciation of stylistic nuance that gives certain melodramas and genre pieces the heft of individuality.”

Who was Segundo de Chomón? In the 1970s, I kept finding that films I thought were by Méliès turned out to bear this mysterious signature. You imagine a man in a cape and a floppy hat. Photographs show someone a little less operatic, but with a superb mustache. Today he’s far from a mystery, although many of his movies can’t be fully identified. Several scholars have followed his trail, none more thoroughly than Joan M. Minguet Batllori in Segundo de Chomón: The Cinema of Fascination.

Chomón started as a cinema man-of-all-work in Barcelona, translating film titles, distributing copies, and producing films for Pathé. After moving to Paris in 1905, he continued working for the company and established his fame with trick films. He returned to Barcelona to create a production company, but that failed. On he went to Italy, where he specialized in visual effects, most famously for Cabiria (1914).

In his Parisian Pathé years, he was in charge of all the studio’s trick films, which included not only stop-motion, superimpositions, and other effects but also marionettes and animation. Joan argues that he was a prime exponent of the “cinema of attractions,” Tom Gunning’s term for that early mode of filmmaking which aims to startle and enchant the audience. A famous instance is Kiriki, acrobats japonais (1907), which shows gravity-defying stunts.

Chomón accomplished this by shooting from straight down, filming the performers on the floor. They had to simulate leaps and flips as they rolled along each other’s bodies, and then they had to slip perfectly into position. This English edition of Joan’s book on Chomón, full of information and providing a “provisional filmography” along with many pages of gorgeous color images, will be available soon here.

We recently noted the anniversary of our book on classic studio cinema, a 1985 project in which we bypassed talking about exhibition. That part of the industry has been a scholarly growth area in the years since, and one of the newest yields is Epics, Spectacles, and Blockbusters: A Hollywood History, by Sheldon Hall and Steve Neale. It’s a chronological account of Big Movies, from the earliest features to the digital era, and it concentrates on how such films have been marketed and shown. It explains how exhibition changed across the decades, and how we got the phenomenon of the “roadshow” movie, the film shown selectively (only certain cities), at intervals (perhaps only one matinee and one evening screening), and at more or less fixed prices. My middle-aged readers will remember roadshow releases like The Sound of Music (1965), although there were many before and even a few since.

We recently noted the anniversary of our book on classic studio cinema, a 1985 project in which we bypassed talking about exhibition. That part of the industry has been a scholarly growth area in the years since, and one of the newest yields is Epics, Spectacles, and Blockbusters: A Hollywood History, by Sheldon Hall and Steve Neale. It’s a chronological account of Big Movies, from the earliest features to the digital era, and it concentrates on how such films have been marketed and shown. It explains how exhibition changed across the decades, and how we got the phenomenon of the “roadshow” movie, the film shown selectively (only certain cities), at intervals (perhaps only one matinee and one evening screening), and at more or less fixed prices. My middle-aged readers will remember roadshow releases like The Sound of Music (1965), although there were many before and even a few since.

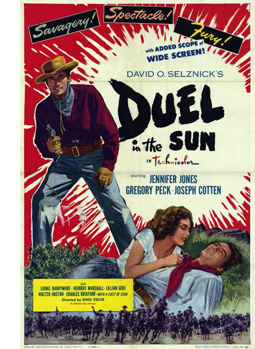

Sheldon and Steve trace in unprecedented detail the cycles of blockbusters that have run throughout American cinema. In the process they refreshingly redefine the very idea. We don’t usually think of The Best Years of Our Lives as a Big Movie, but it runs three hours and was considered a “special” production, comparable to the more obvious sprawl of Duel in the Sun. The authors bring the story up to date by considering today’s event movies as a “Cinema of Spectacular Situations.” Yes, that category includes comic-book films, Inception, and, of course, the 3D sagas that may finally be wearing out their welcome. (My editorializing, not theirs.)

Japanese cinema is endlessly fascinating in all its eras; I’d argue that in toto it’s one of the three greatest national cinemas in film history. The postwar period is exceptionally interesting because of the American occupation (1945-1951) and its effects on Japanese film culture. This period has already provoked one of the best books we have on Japanese cinema, Kyoko Hirano’s Mr. Smith Goes to Tokyo, and it finds a worthy accompaniment in Hiroshi Kitamura’s Screening Enlightenment: Hollywood and the Cultural Reconstruction of Defeated Japan. Kyoko focused on how US policy shaped domestic filmmaking, while Hiroshi asks how the Occupation helped American studios penetrate the local market.

Over six hundred Hollywood movies poured into Japan during the period, and Hiroshi traces how local tastemakers as well as U.S. policymakers drew audiences to them. Young Japanese learned about the Academy Awards, assembled in movie-study clubs to discuss what they were seeing, and were urged to consider even a gangster tale like Cry of the City (1950) as demonstrating the humanistic side of democracy. A center of this activity was Eiga no tomo (“Friends of the Movies”), a magazine that went beyond entertainment news and tried to reshape the tastes of young people. In sharp prose and vivid evidence, Hiroshi captures the ways in which American cinema promised to help heal a devastated country.

The Danish Directors, by Mette Hjort and Ib Bondebjerg, has become a standard companion to the most successful “small cinema” on the European scene. Now it has a successor in The Danish Directors 2: Dialogues on the New Danish Fictional Cinema, edited by Mette, Eva Jorholt, and Eva Novrup Redvall. Once again, we get lengthy, in-depth interviews covering the value of film education, the vagaries of funding, and filmmakers’ creative decision-making. Lone Scherfig, Christoffer Boe, Per Fly, Paprika Steen, and many other major figures are included. (Disclosure: The editors were kind enough to dedicate the book to me.)

The Danish Directors, by Mette Hjort and Ib Bondebjerg, has become a standard companion to the most successful “small cinema” on the European scene. Now it has a successor in The Danish Directors 2: Dialogues on the New Danish Fictional Cinema, edited by Mette, Eva Jorholt, and Eva Novrup Redvall. Once again, we get lengthy, in-depth interviews covering the value of film education, the vagaries of funding, and filmmakers’ creative decision-making. Lone Scherfig, Christoffer Boe, Per Fly, Paprika Steen, and many other major figures are included. (Disclosure: The editors were kind enough to dedicate the book to me.)

While the first volume is a rich storehouse of information on Danish film in “the Dogma era,” the newest volume shows how directors (some of whom made Dogma projects) have gone beyond it. In preparing 1:1, a film about Danes and Arab immigrants living in a housing project, Annette K. Olesen had a full script but concealed it from the non-professional cast. After getting the performers comfortable with ordinary situations, she began staging scenes while encouraging improvisation. Screenwriter Kim Fupz Aakeson incorporated the improvised material into revisions of the script.

By contrast, the prolific director-screenwriter Anders Thomas Jensen (Adam’s Apples, The Green Butchers), relies on strong structure, with lean expositions and sharply defined climaxes. He appreciates clean filming technique too.

It’s easy to make something that’s ugly and handheld, but you have to take telling stories with images seriously. You have to take the language of film seriously. Many Danish directors have started doing this in recent years and it’s wonderful, because there was a time when everything looked Dogma-like and I found myself thinking, “It’s got to stop now.”

To those who think that Danish cinema is at risk of becoming a cinema of cozy liberal reassurance, this collection offers many salutary signs. Every director speaks of the need to keep innovating, to push ahead provocatively. Simon Staho, whose Day and Night seems to me one of the most adventurous Danish films of recent years, aims at utter purity: “My task is to figure out how to add as little as possible to the black screen. The damned problem is that you have to add image and sound!”

What makes all these books exciting to me is a willingness to test ideas–sometimes very general ones–about cinema and the wider world by examining film as a distinctive art form. Even the most conceptual books on this week’s shelf are firmly rooted in the particular choices that creators make and the concrete ways that viewers respond.

Next stop: Vancouver International Film Festival. Whoopee!

Day and Night.

A second chance at childhood

DB here:

This year Ebertfest has been such a swirl of activity that I hardly know where to start. Jim Emerson’s reportage, here and here, decorated with neat photos and trim Tweets, has admirably hit the high points—the panels, the Q & A’s, and the young Web critics, or “foreign correspondents,” that Roger has summoned to his annual get-together. There’s even streaming of the panels and Q & A.

After participating in four events in rapid succession, I find that I’m still sorting out impressions. I hope to do justice to the broad swathe of doings in another entry after I get home tomorrow. For now, why not just let my impulses take over and write about my most enjoyable movie so far?

Takita Yojiro’s Departures (2008) well deserves the standing ovation that greeted him when he stepped out on the Virginia Theatre stage. I mentioned the film last year, and since then I’ve seen it two more times, not counting the splendid projection Friday. I was happy that Roger shares my affection for the movie. In my remarks before the screening, I praised the movie’s willingness to go straight for the heart. This sort of sincerity, which John Ford or Frank Borzage would have understood, is hard to come by in today’s American cinema, where emotion tends to be framed by irony or self-consciousness cuteness (500 Days of Summer). My intro did mention the comedy in the film, but I didn’t stress it enough. Watching it with the Ebertfest audience again taught me that the film cleverly uses humor to lead us into its pathos.

Takita Yojiro’s Departures (2008) well deserves the standing ovation that greeted him when he stepped out on the Virginia Theatre stage. I mentioned the film last year, and since then I’ve seen it two more times, not counting the splendid projection Friday. I was happy that Roger shares my affection for the movie. In my remarks before the screening, I praised the movie’s willingness to go straight for the heart. This sort of sincerity, which John Ford or Frank Borzage would have understood, is hard to come by in today’s American cinema, where emotion tends to be framed by irony or self-consciousness cuteness (500 Days of Summer). My intro did mention the comedy in the film, but I didn’t stress it enough. Watching it with the Ebertfest audience again taught me that the film cleverly uses humor to lead us into its pathos.

The first half hour handles a lot of narrative business. We need to meet the main characters and learn their situation, of course. We also need an introduction to the trade of encoffinment, the practice of preparing the body of the deceased for cremation. But if the story proceeded chronologically, we wouldn’t get this introductory scene for quite a while. So the film provides a pre-credits flashforward that serves up the process, making it palatable with a dose of humor.

We see Daigo and his crusty boss Sasaki visiting a household and arranging a young woman’s corpse. No, it’s not a woman: Daigo discovers that the corpse has a penis. Should they apply male or female make-up? This bit of comedy undercuts the solemnity of the occasion and builds up curiosity: How to resolve the situation? Cut back to Daigo two months earlier, playing the cello in an orchestra that is about to be disbanded. The end of his musical career sends him and his wife back to his hometown seeking a new job.

Since the first scene shows Daigo practicing the “sending-off” trade, we know how that search will turn out. With our superior knowledge we can enjoy all the misunderstandings that fill the first scenes in Yamagata. A misprint in the newspaper ad makes Daigo think he’s applying to a travel bureau; Sasaki hires him without glancing at his résumé; Daigo becomes disturbed at the prospect of handling dead bodies, but the generous advance makes him decide to try. Moreover, in the opening we’ve watched him skillfully executing the routines of the ceremony, so we know that he will eventually succeed. The question is how.

One of the pleasures of movies is showing us how people work. (Think of Steve McQueen running the ship’s engine in The Sand Pebbles, or the arcana of sleight of hand in The Prestige.) So the opening fascinates by introducing us, matter-of-factly, to a craft. In doing so, the scene treats the ceremony fairly objectively. A second ceremony is staged for a video demo, with Daigo serving as the corpse. Here the comedy is even broader, but we’re still learning about the procedures.

A third ceremony, involving the decomposed body of an old woman, is skipped over, but it is heavy in consequences. It drives Daigo to the bathhouse to clean up, and there he reunites with an old friend and his mother, the bathhouse owner. The third encounter also makes Daigo return to playing the cello, using the instrument he was given as a boy. In a way, the whole story offers another chance at childhood. Daigo, feeling guilty for abandoning his mother and angry at the father who deserted them, will be granted a chance to reconcile with both.

The film’s next sending-off ceremony is a turning point, for it’s Daigo’s first encounter with the dignity of Sasaki’s craft. With the young man we study the tender precision with which Sasaki tucks the dead wife’s garments around her, strokes her face and hands, and applies her favorite lipstick. The husband, initially enraged that Sasaki and Daigo arrived late, ends up moved to tears: “She never looked so beautiful.” Here, fifty minutes into the film, humor is suspended in order to present a compassionate gravity in the face of death. Characteristically, however, a certain lightness returns when in the car Sasaki and Daigo chew noisily on the snacks the husband has given them.

From a penis joke and Daigo’s humiliation at playing dead for the video, the film has led us to care about the characters. We can relax and start to appreciate the depths of what Sasaki and Daigo do. The film will busy itself with new problems—the shame Daigo faces in pursuing this craft, his stratagems for concealing it from his wife Mika, his revived memories of his father, a subplot involving another son impatient with his mother—but we are now ready for these enrichments of the central situation. Eventually too we will see the encoffinment ceremony though other characters’ eyes, as they arrive at our appreciation of its astringent tenderness.

The shrewd placement of the opening flashforward has gently pulled us into the story’s world and its key issue, the tie between the living and the dead. By the time that we return to that family and their transvestite son, the question of how to make up his face has gathered a thick array of associations. The parents’ quarrel anticipates all the other parent/ child relationships that accrue across the film, and the resolution of it, through a father acknowledging his guilt, provides a foretaste of the climax.

The unruffled exactness of Sasaki’s tradecraft is mirrored in Takita’s direction. This is classic Japanese filmmaking: Not a wasted shot, each angle precisely depicting what we need to see at any moment. After the fumbling and flailing displayed by most contemporary Hollywood directors, after filmmakers’ urge to “give a scene energy” manages to muff getting an actor out of a car, it’s a pleasure to watch powerful effects achieved delicately. How many movies can wring tears from uncurling a fist or an image of a smooth stone on a woman’s palm?

Several scenes of the dead include photos of the person in life. Early on, these are given force through simple cutaways.

Once he’s trained us to watch for these photos, Takita can let us compare death and life through more discreet revelations, as when a slight movement of Daigo’s head allows us to see a photo that remains out of focus.

Or take the moment when Daigo comes home after preparing the decomposed body. He gags when he sees that Mika is preparing raw chopped chicken, but then he frantically embraces her. The gestures begin in panic but end in desire. At this point Takita cuts to a new angle, a long shot showing the couple, the table, and the dish that triggered it all.

It’s always sound practice to tactfully recall earlier moments in a film, but the composition also completes the scene’s arc from disgust at death to ardent vitality.

The whole film’s craftsmanship is as warm and fastidious as the job practiced by the send-off experts. At the end, Daigo’s respectful handiwork, with all its dispassionate concern, turns into caresses, the intimate gestures of a son rediscovering a parent through physical contact. Modulation of movement, mood, and attitude; slight variations that become subtly expressive; the prosaic detail that cuts right through you: In this domain the Japanese cinema has no superior. Departures shows that this tradition lives on.

The Omnivoyeur’s dilemma

Otouto.

DB here:

Any major film festival is really many festivals. You meet someone who tells you about all the films they’ve been seeing, and the overlap with your dance card is virtually nil. You’ve both been in the same town, and probably hit the same venues, but you’ve been to different festivals.

Then there are certain syndromes. You convince yourself you need to see 3-5 films a day. Otherwise, what’s the point of traveling all this way? Soon you realize, horribly, that after a couple of days of this regimen, you can’t recall what you’ve seen. Some early afternoon, Festival Amnesia will set in, and you can’t remember what you saw that morning. Was it that ambitious but ultimately unsatisfying little romance from the Bosporus? Or the Chinese movie about moping teenagers trying to leave their dingy village? What were the names of those movies, anyhow?

My own symptoms are getting acute. Twice in recent years, I have found myself in front of a film suddenly realizing that I had seen it at another festival. I had forgotten the title. At least I caught my mistake with the first shots, but I expect that in time I will obliviously sit through the whole movie twice—probably liking it on the first pass and declaring it disappointing on the second.

Then there’s Viewer’s Remorse. Watching 3-5 titles a day, you inevitably encounter some stinkers. You take this philosophically until you meet someone else, who rhapsodizes about the string of masterpieces they’ve seen. Suddenly you realize that you have backed losers. Your friend has had a transformative festival experience, and you might as well have been flossing. Worse, your carefully picked mediocrities swell in your mind, blotting out the good films you managed to catch by dumb luck. Panicked, you thumb through the schedule to see if the great things you’ve missed are playing a second time.

They aren’t.

So film festivals aren’t by any means the sweet deal they may at first seem. Even putting aside queueing, officious door staff, racing between venues, and projection problems, there are plenty of features to make people like me more neurotic than we already are.

But I can’t complain about my latest visit to Hong Kong. True, breathing problems put me out of commission some days and eventually forced me to return home early. My biggest regrets were missing the Zanussi films and the two Angelopolous films, The Weeping Meadow and The Dust of Time. (Watch: Somebody will tell me they are all masterpieces.) Still, I managed to see a fair amount in two mini-festivals I carved out of Filmart and the festival proper.

Turning Japanese, yet again

Golden Slumber.

Parade, from director Isao Yukisada, is an ensemble picture about Tokyo twentysomethings sharing a flat. Their love affairs and marathon viewings of soap operas are disrupted when Satoru, a male prostitute, crashes there one night and winds up hanging around with them. With his blank passivity and ambisexual good looks he arouses their curiosity and, as usual in such movies, winds up changing everyone’s lives. The film was pretty good at portraying the way the kids keep life intriguing by conjuring up mysteries about their neighbors. (Is the man next door running a brothel?) The plot ran out of steam, I thought, but I enjoyed seeing a movie in that sober style that apparently only the Japanese can now pull off: only about 400 shots in nearly two hours, with an unassertive fixed camera that gave the characters room to breathe.

Also about a young cohort, but more action-driven, was Golden Slumber, by Nakamura Yoshihiro. He directed Fish Story (2008), a favorite of mine from last year’s festival. This one is about a hapless young man pulled into a plot to assassinate the prime minister. Threaded with glimpses of his college days, when he and his pals worked in a fireworks shop and became connoisseurs of fast food, the plot follows his efforts to avoid arrest and find how he was framed. Like a lot of contemporary Asian films, Golden Slumber sounds a note of nostalgia not only for long-lost innocence but also for kids’ self-consciously retro tastes in popular culture—in this case, the Beatles song “Golden Slumbers” (“Once there was a way to get back home . . . .”). Less zany than Fish Story, whose story pivoted around how an obscure album prepared for the end of the world, this seemed to me finally quite agreeable, thanks to its likably awkward hero and its lovelorn ending.

Longtime readers of this blog won’t be surprised that one favorite of my personal Japanese mini-fest was Yamada Yoji’s tear-jerker Otouto (aka Ototo, “Younger Brother”), a remake of a 1960 Ichikawa film. A widow who ekes out a living as a pharmacist is about to marry off her beautiful daughter. But during the wedding dinner her ne’er-do-well brother pops up and turns the ceremony into a catastrophe. Japanese movies are very good at evoking social embarrassment, and the disruption caused by Tetsuro makes you wriggle in your seat. He could have been simply a lovable loser, but he’s not that likable, let alone lovable, and his waywardness brings misfortunes on his sister’s family. In this movie about how you must love your relations no matter what, Yamada shows the classic resignation to family ties that has characterized the films from the Shochiku studio since the 1920s.

As usual with Yamada, the direction is crystalline in a way you hardly ever see now: calm framings, unhurried pacing, longish takes (about 12 seconds on average), and lighting and composition that etch every object in relief. When Ginko the mother peels an apple, the skin curls off in a long ribbon, and it’s as fascinating as a car chase in any other movie. In a film in which the camera seldom moves, a handheld shot regains some of its original power. Maybe I’m what Groucho called a sentimental old fluff, but like Kabei–Our Mother, Otouto shows that some cinematic traditions are still worth something.

For the real Shochiku flavor, experts will tell you, you need to return to the 1930s, and the festival did so with its small retrospective of Shimazu Yasujiro. A prolific director of comedies and dramas (he made over a hundred silent films), Shimazu built a reputation in the 1920s with family dramas like Father (1923). Most of his films are lost, and he died in 1945, so he didn’t benefit from the postwar revival of the industry and its growing renown in the West. His most famous work is probably the ingratiating Our Neighbor Mis Yae (1934), which features in the retrospective.

The remaining Shimazu films don’t seem to me to reveal the stylistic consistency we find in Ozu or Mizoguchi or Shimizu. There are flamboyant pictorial touches in First Steps Ashore (1932), a drama of sailors and prostitutes with stark lighting and cluttered sets influenced by The Docks of New York.

A fight scene is rendered in a long-lens shot that looks very modern, though the technique had already been seen in Japanese swordplay films.

Perhaps most original are the variants Shimazu works on a picturesque divider in a waterfront bar, which becomes a fascinating grid that sorts out faces.

Having been trained by this cheese-grater divider, we are given the tougher task of spotting the seaman peering from the distance at our stoker hero and the taxi dancer he rescues. (Not so easy to see in my still: He’s watching from the square and circle aligned horizontally behind the hero’s lips and chin.)

This “game of vision,” where we must strain to see action that’s blocked by bits of setting or furnishing, is characteristic of Japanese film then and since.

Okoto and Sasuke (1935) and Lights of Asakusa (1937), the two Shimazus I caught during my stay, aren’t as visually tricky as First Steps Ashore, but they display Shimazu’s characteristic interest in marginal characters (a blind woman in Okoto, stage performers in Asakusa). Both films close with a self-sacrificing retreat from the world. Later films, including the wonderful Brother and His Younger Sister (1939), would give this retreat a positive ideological spin. Disgusted by office politics, a young man takes his sister and mother to Manchuria to start anew, and the finale shows a clump of earth clinging to the plane wheels, as if a bit of Japan’s very soil would sanctify the empire’s new outpost.

Fei Mu, Film Poet

Nightmares in Spring Chamber.

A second mini-festival during my Hong Kong stay centered on Chinese film history. I’ve mentioned the Patrick Lung Kong titles in an earlier entry. The other prime figure was Fei Mu, celebrated as one of China’s best filmmakers. His Spring in a Small Town (1948) is often considered the greatest of all Chinese films, and it’s not an unreasonable judgment.

Unfortunately, only about half of Fei’s output survives. The earliest film we have is Song of China (aka Filial Piety, 1935), a paean to Confucian virtues. Parents permit their son to move to the city, but the son falls prey to self-indulgence and a temperamental wife. Even when he holds a banquet to honor his parents it is merely an excuse for what the father calls “revelry and gambling.” Soon the daughter is being seduced by a city slicker and told that “parental consent is a timeworn tradition.” This lesson in traditional morality is filmed quite fluently, with telling use of tracking shots, especially during the banquet, and sudden bursts of angular montage.

On Stage and Backstage (1937), from a Fei Mu script, is a 37-minute comedy. A troublesome diva refuses to come to a performance unless she’s paid, but the manager can’t afford it. So a street performer is brought in to substitute for the star in a performance of Farewell My Concubine. While the production is shot frontally and with little depth, director Zhou Yihua contrasts that area of action with the backstage milieu by means of layered compositions and lateral tracking shots through tangles of ropes and props. I enjoyed this charming film when I saw it during my first trip to Hong Kong, and its appeal held up well for me.

I came home too soon to catch Bloodshed on Wolf Mountain (1936), usually considered a strong work, and the little-seen Children of the World (1940). Other films in the series included The Show Must Go on (1952) from a Fei script and Romance in the Boudoir (1960), from Fei’s brother Louis; I already discussed the latter here. There were also two Chinese Opera films. A Wedding in the Dream (1948), China’s first color film, stars the legendary Mei Lanfang, the Peking Opera performer best known in the west who became friends with Chaplin and Eisenstein.

This image from Wedding in the Dream is a posed production still; the film itself, a straightforward record of Mei’s performance, survives in dreadfully worn condition. I found Murder in the Oratory (1937) more intriguing. A man is urged by his mother to murder his wife, the daughter of the man who killed his father. From the start, when an opera stage dissolves into a fully three-dimensional space, you realize that this will be an experiment in creating something halfway between canned theatre and a “filmic” treatment. So we get all the trappings of an opera performance, including stylized movement and singing, but with the camera weaving among the characters and furnishings, finding unusual angles, and even assuming characters’ optical viewpoints.

Far different is another title I enjoyed on my first visit to Hong Kong in 1995. Nightmares in Spring Chamber (1937) is an episode in the portmanteau film Lianhua Symphony. This 13-minute allegory of Japan’s imperial ambitions shows a maniacal frock-coated Japanese pursuing innocent Chinese girls through a vast bare villa. He cackles over a spinning globe and captures one girl, but she’s rescued by the other, a surrogate for the Chinese soldier we glimpse occasionally. Full of canted angles, hallucinatory visions, under lighting, looming shadows, and other trappings of German Expressionism, and accompanied by snatches of Debussy and the Danse macabre, it’s a far cry from the other items in the series, and it suggests a director of considerable versatility.

Last year the Festival premiered the restoration of the rerelease of Fei’s 1940 Confucius, which I wrote about then. This year a second restoration inserted titles to cover the gaps and put some scrappy scenes into their proper order. In addition, a very informative book, Fei Mu’s Confucius, accompanied the screenings. The essays explicate the film from several angles, including its relation to Confucian doctrine, to classic poetry and painting, and to other Fei Mu works.

Thanks to retrospectives like this one, we can see how much Fei’s official masterwork owes to his earlier efforts. There are touches of lighting and staging in these films that are more subtly developed in Spring in a Small Town, and the stately pacing of Confucius is here put to more mundane subject matter. Still, nothing I saw matches the quiet erotic boldness of this milestone of world cinema, which anticipates so much of what we find in Antonioni and other postwar European filmmakers.

So much to see, and even less time than I’d planned: Film festivals somehow manage to leave you unsatisfied and yet feeling full. A nice dilemma to have.

Spring in a Small Town.